John Ray on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

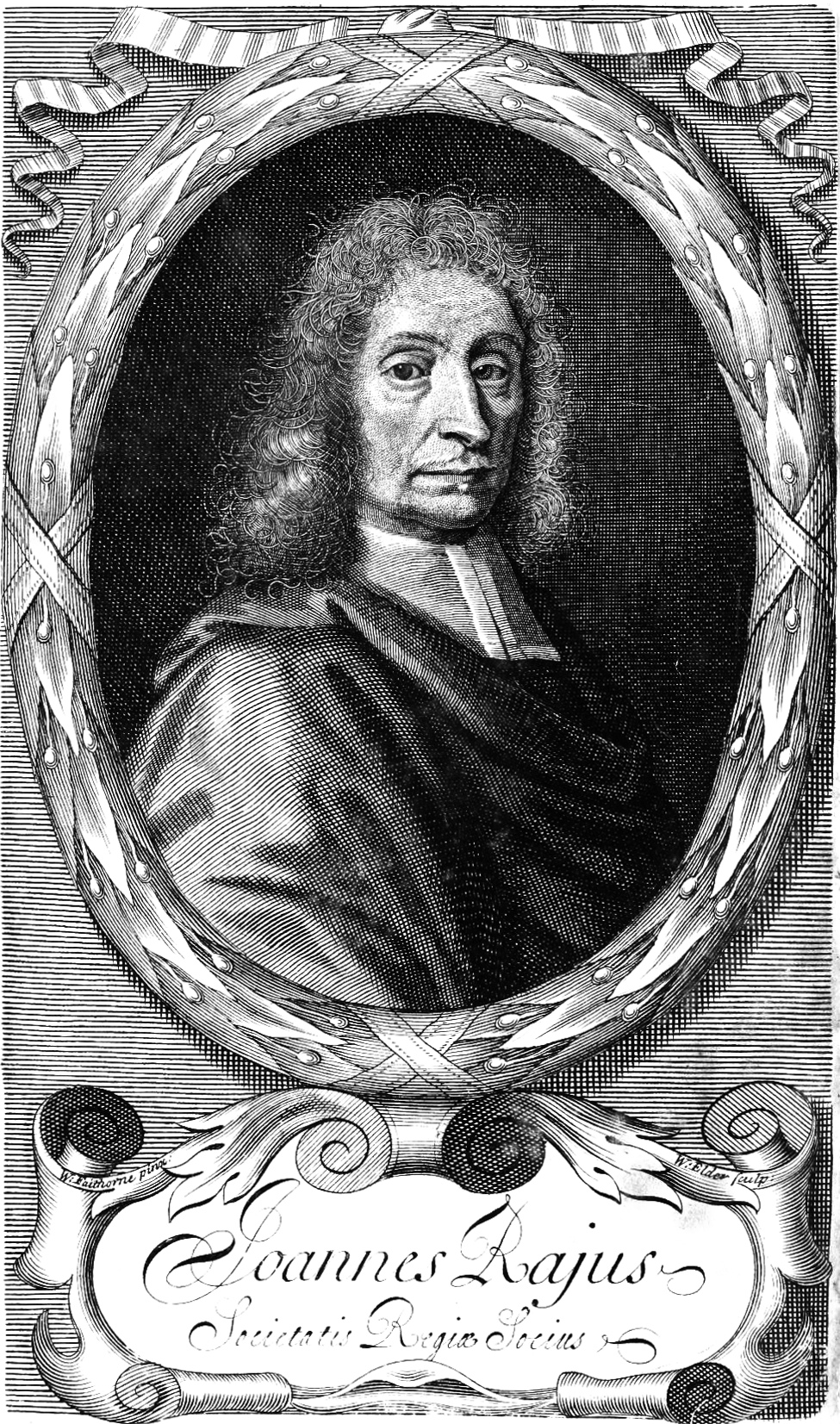

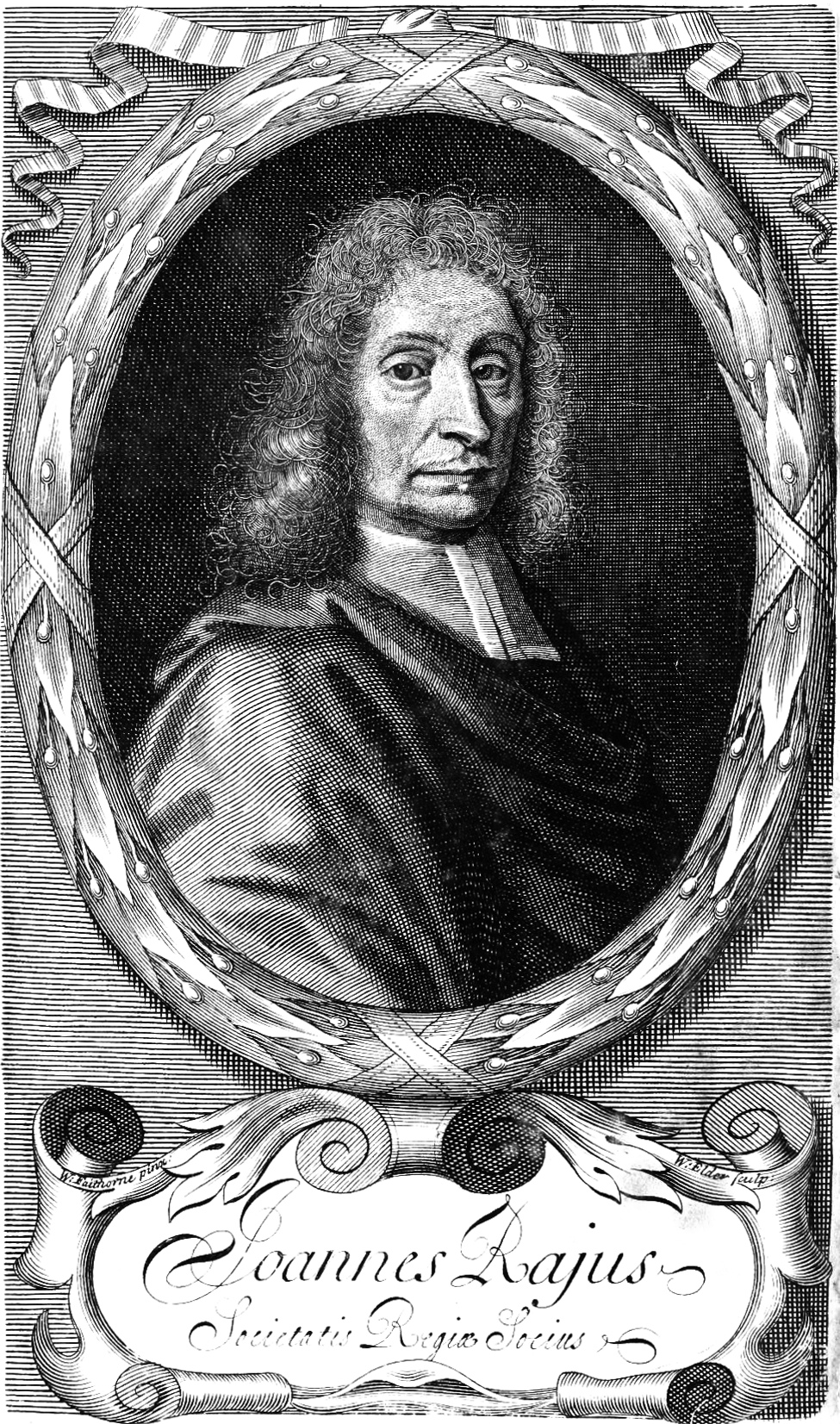

John Ray FRS (29 November 1627 – 17 January 1705) was a Christian

John Ray FRS (29 November 1627 – 17 January 1705) was a Christian

John Ray was born in the village of

John Ray was born in the village of

At Cambridge, Ray spent much of his time in the study of natural history, a subject which would occupy him for most of his life, from 1660 to the beginning of the eighteenth century. When Ray found himself unable to subscribe as required by the ‘Bartholomew Act’ of 1662 he, along with 13 other college fellows, resigned his fellowship on 24 August 1662 rather than swear to the declaration that the Solemn League and Covenant was not binding on those who had taken it. s:Ray, John (DNB00)

At Cambridge, Ray spent much of his time in the study of natural history, a subject which would occupy him for most of his life, from 1660 to the beginning of the eighteenth century. When Ray found himself unable to subscribe as required by the ‘Bartholomew Act’ of 1662 he, along with 13 other college fellows, resigned his fellowship on 24 August 1662 rather than swear to the declaration that the Solemn League and Covenant was not binding on those who had taken it. s:Ray, John (DNB00)

online

* 1675: ''Trilingual dictionary, or nomenclator classicus''. * 1676

''Willughby's Ornithologia''

* *

* 1686: ''History of fishes''. * 1686–1704: ''Historia plantarum species'' 'History of plants'' London:Clark 3 vols; *

Vol 1 1686Vol 2 1688Vol 3 1704

(in Latin) *

Lazenby, Elizabeth Mary (1995). The Historia Plantarum Generalis of John Ray, Book I : a translation and commentary. PhD thesis Newcastle University

* ** 2nd ed 1696 * 1691

''The wisdom of God Manifested in the Works of the Creation'' 7th ed.

2nd ed 1692, 3rd ed 1701, 4th ed 1704, 7th ed 1717 * 1692

''Miscellaneous discourses concerning the dissolution and changes of the world''

* 1693:

Synopsis of animals and reptiles

'. * 1693: ''Collection of travels''. * 1694: ''Collection of European plants''. * 1695: ''Plants of each county''. (Camden's Britannia) * *

* 1700: ''A persuasive to a holy life''. * ;Posthumous * 1705. ''Method and history of insects'' * 1713: '

Synopsis methodica avium & piscium: opus posthumum (''Synopsis of birds and fishes'')'', in Latin. William Innys, London

vol. 1: ''Avium'' vol. 2: ''Piscium'' * 171

''Three Physico-theological discourses''

* *

Facsimile edition 197

Ray Society, London. With introduction by

Ray's biographer, Charles Raven, commented that "Ray sweeps away the litter of mythology and fable... and always insists upon accuracy of observation and description and the testing of every new discovery".p10 Ray's works were directly influential on the development of taxonomy by

Ray's biographer, Charles Raven, commented that "Ray sweeps away the litter of mythology and fable... and always insists upon accuracy of observation and description and the testing of every new discovery".p10 Ray's works were directly influential on the development of taxonomy by

here

at Biodiversity Heritage Library) * * See als

ebook 2010

* * * , see also * * * , in

John Ray's works at the

Biodiversity Heritage Library

John Ray BiographyUniversity of California Museum of Paleontology Berkeley

The first biological species concept (Evolving Thoughts)

''Memoir of John Ray''

by James Duncan

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

John Ray and taxonomy. King's College London

Encyclopaedia Britannica

Dictionary of Scientific Biography

The John Ray Initiative: connecting Environment and Christianity

*

*

{{DEFAULTSORT:Ray, John 1628 births 1705 deaths Phycologists Alumni of St Catharine's College, Cambridge Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge Botanists with author abbreviations English naturalists Bryologists 17th-century English botanists Fellows of the Royal Society Paleobotanists People from Black Notley Parson-naturalists 17th-century Protestants 17th-century English writers 17th-century English male writers 18th-century English writers 18th-century English male writers Burials in Essex Writers about religion and science

John Ray FRS (29 November 1627 – 17 January 1705) was a Christian

John Ray FRS (29 November 1627 – 17 January 1705) was a Christian English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

naturalist widely regarded as one of the earliest of the English parson-naturalist

A parson-naturalist was a cleric (a "parson", strictly defined as a country priest who held the living of a parish, but the term is generally extended to other clergy), who often saw the study of natural science as an extension of his religious wo ...

s. Until 1670, he wrote his name as John Wray. From then on, he used 'Ray', after "having ascertained that such had been the practice of his family before him". He published important works on botany

Botany, also called , plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "botany" comes from the Ancient Greek w ...

, zoology

Zoology ()The pronunciation of zoology as is usually regarded as nonstandard, though it is not uncommon. is the branch of biology that studies the animal kingdom, including the structure, embryology, evolution, classification, habits, and ...

, and natural theology. His classification of plants in his ''Historia Plantarum'', was an important step towards modern taxonomy

Taxonomy is the practice and science of categorization or classification.

A taxonomy (or taxonomical classification) is a scheme of classification, especially a hierarchical classification, in which things are organized into groups or types. ...

. Ray rejected the system of dichotomous

A dichotomy is a partition of a whole (or a set) into two parts (subsets). In other words, this couple of parts must be

* jointly exhaustive: everything must belong to one part or the other, and

* mutually exclusive: nothing can belong simult ...

division by which species were classified according to a pre-conceived, either/or type system , and instead classified plants according to similarities and differences that emerged from observation. He was among the first to attempt a biological definition for the concept of ''species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

'', as "a group of morphologically similar organisms arising from a common ancestor". Another significant contribution to taxonomy was his division of plants into those with two seedling leaves (dicotyledons

The dicotyledons, also known as dicots (or, more rarely, dicotyls), are one of the two groups into which all the flowering plants (angiosperms) were formerly divided. The name refers to one of the typical characteristics of the group: namely, t ...

) or only one (monocotyledons

Monocotyledons (), commonly referred to as monocots, ( Lilianae '' sensu'' Chase & Reveal) are grass and grass-like flowering plants (angiosperms), the seeds of which typically contain only one embryonic leaf, or cotyledon. They constitute one of ...

), a division used in taxonomy today.

Life

Early life

John Ray was born in the village of

John Ray was born in the village of Black Notley

Black Notley is a village and civil parish in Essex, England. It is located approximately south of Braintree and is north-northeast from the county town of Chelmsford. According to the 2011 census including Young's End it had a population of ...

in Essex. He is said to have been born in the smithy, his father having been the village blacksmith

A blacksmith is a metalsmith who creates objects primarily from wrought iron or steel, but sometimes from other metals, by forging the metal, using tools to hammer, bend, and cut (cf. tinsmith). Blacksmiths produce objects such as gates, gr ...

. After studying at Braintree school, he was sent at the age of sixteen to Cambridge University: studying at Trinity College Trinity College may refer to:

Australia

* Trinity Anglican College, an Anglican coeducational primary and secondary school in , New South Wales

* Trinity Catholic College, Auburn, a coeducational school in the inner-western suburbs of Sydney, New ...

. Initially at Catharine Hall, his tutor was Daniel Duckfield, and later transferred to Trinity where his tutor was James Duport

James Duport (; 1606, Cambridge17 July 1679, Peterborough) was an English classical scholar.

Life

His father, John Duport, who was descended from an old Norman family (the Du Ports of Caen, who settled in Leicestershire during the reign of Henr ...

, and his intimate friend and fellow-pupil the celebrated Isaac Barrow. Ray was chosen minor fellow of Trinity in 1649, and later major fellow. He held many college offices, becoming successively lecturer in Greek (1651), mathematics (1653), and humanity (1655), ''praelector

A praelector is a traditional role at the University of Cambridge and the University of Oxford. The role differs somewhat between the two ancient universities.

University of Cambridge

At Cambridge, a praelector is the fellow of a college who forma ...

'' (1657), frias (1657), and college steward (1659 and 1660); and according to the habit of the time, he was accustomed to preach in his college chapel and also at Great St Mary's

St Mary the Great is a Church of England parish and university church at the north end of King's Parade in central Cambridge, England. It is known locally as Great St Mary's or simply GSM to distinguish it from "Church of St Mary the Less, Cambri ...

, long before he took holy orders on 23 December 1660. Among these sermons were his discourses on ''The wisdom of God manifested in the works of the creation'', and ''Deluge and Dissolution of the World''. Ray was also highly regarded as a tutor and he communicated his own passion for natural history to several pupils. Ray's student, Isaac Barrow, helped Francis Willughby learn mathematics and Ray collaborated with Willughby later. It was at Trinity that he came under the influence of John Wilkins

John Wilkins, (14 February 1614 – 19 November 1672) was an Anglican clergyman, natural philosopher, and author, and was one of the founders of the Royal Society. He was Bishop of Chester from 1668 until his death.

Wilkins is one of the f ...

, when the latter was appointed master

Master or masters may refer to:

Ranks or titles

* Ascended master, a term used in the Theosophical religious tradition to refer to spiritually enlightened beings who in past incarnations were ordinary humans

*Grandmaster (chess), National Master ...

of the college in 1659.

Later life and family

After leaving Cambridge in 1663 he spent some time travelling both in Britain and the continent. In 1673, Ray married Margaret Oakley ofLaunton

Launton is a village and Civil parishes in England, civil parish on the eastern outskirts of Bicester, Oxfordshire, England. The United Kingdom Census 2011, 2011 Census recorded the parish's population as 1,204.

Manor

King Edward the Confessor ...

in Oxfordshire; in 1676 he went to Middleton Hall near Tamworth, and in 1677 to Falborne (or Faulkbourne

Faulkbourne is a small settlement and civil parish in the Braintree district of Essex, England, about 2 miles (3 km) northwest of Witham. The population at the 2011 Census was included in the civil parish of Fairstead. The name of the vil ...

) Hall in Essex. Finally, in 1679, he removed to his birthplace at Black Notley

Black Notley is a village and civil parish in Essex, England. It is located approximately south of Braintree and is north-northeast from the county town of Chelmsford. According to the 2011 census including Young's End it had a population of ...

, where he afterwards remained. His life there was quiet and uneventful, although he had poor health, including chronic sores. Ray kept writing books and corresponded widely on scientific matters, collaborating with his doctor and contemporary Samuel Dale

Samuel Dale (1772 – ), known as the "Daniel Boone of Alabama", was an American frontiersman, trader, miller, hunter, scout, courier, soldier, spy, army officer, and politician, who fought under General Andrew Jackson, in the Creek War, la ...

.Morris, A. D. (1974). Samuel Dale (1659-1739), Physician and Geologist. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine, 67, 120–124. Retrieved from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/003591577406700215 He lived, in spite of his infirmities, to the age of seventy-seven, dying at Black Notley. He is buried in the churchyard of St Peter and St Paul where there is a memorial to him. He is widely regarded as one of the earliest of the English parson-naturalist

A parson-naturalist was a cleric (a "parson", strictly defined as a country priest who held the living of a parish, but the term is generally extended to other clergy), who often saw the study of natural science as an extension of his religious wo ...

s.

Work

At Cambridge, Ray spent much of his time in the study of natural history, a subject which would occupy him for most of his life, from 1660 to the beginning of the eighteenth century. When Ray found himself unable to subscribe as required by the ‘Bartholomew Act’ of 1662 he, along with 13 other college fellows, resigned his fellowship on 24 August 1662 rather than swear to the declaration that the Solemn League and Covenant was not binding on those who had taken it. s:Ray, John (DNB00)

At Cambridge, Ray spent much of his time in the study of natural history, a subject which would occupy him for most of his life, from 1660 to the beginning of the eighteenth century. When Ray found himself unable to subscribe as required by the ‘Bartholomew Act’ of 1662 he, along with 13 other college fellows, resigned his fellowship on 24 August 1662 rather than swear to the declaration that the Solemn League and Covenant was not binding on those who had taken it. s:Ray, John (DNB00) Tobias Smollett

Tobias George Smollett (baptised 19 March 1721 – 17 September 1771) was a Scottish poet and author. He was best known for picaresque novels such as '' The Adventures of Roderick Random'' (1748), '' The Adventures of Peregrine Pickle'' (1751 ...

quoted the reasoning given in the biography of Ray by William Derham

William Derham FRS (26 November 16575 April 1735)Smolenaars, Marja.Derham, William (1657–1735), ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, 2004. Accessed 26 May 2007. was an English clergyman, natural theologian, n ...

:

"The reason of his refusal was not (says his biographer) as some have imagined, his having taken the solemn league and covenant; for that he never did, and often declared that he ever thought it an unlawful oath: but he said he could not say, for those that had taken the oath, that no obligation lay upon them, but feared there might."His religious views were generally in accord with those imposed under the restoration of Charles II of England, and (though technically a

nonconformist

Nonconformity or nonconformism may refer to:

Culture and society

* Insubordination, the act of willfully disobeying an order of one's superior

*Dissent, a sentiment or philosophy of non-agreement or opposition to a prevailing idea or entity

** ...

) he continued as a layman in the Established Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britai ...

.

From this time onwards he seems to have depended chiefly on the bounty of his pupil Francis Willughby

Francis Willughby (sometimes spelt Willoughby, la, Franciscus Willughbeius) FRS (22 November 1635 – 3 July 1672) was an English ornithologist and ichthyologist, and an early student of linguistics and games.

He was born and raised at ...

, who made Ray his constant companion while he lived. Willughby arranged that after his death, Ray would have 6 shillings a year for educating Willughby's two sons.

In the spring of 1663 Ray started together with Willughby and two other pupils (Philip Skippon

Philip Skippon (c. 1600, West Lexham, Norfolk – c. 20 February 1660) supported the Parliamentary cause during the English Civil War as a senior officer in the New Model Army. Prior to the war he fought in the religious wars on the continent. D ...

and Nathaniel Bacon) on a tour through Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

, from which he returned in March 1666, parting from Willughby at Montpellier, whence the latter continued his journey into Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

. He had previously in three different journeys (1658, 1661, 1662) travelled through the greater part of Great Britain, and selections from his private notes of these journeys were edited by George Scott in 1760, under the title of ''Mr Ray's Itineraries''. Ray himself published an account of his foreign travel in 1673, entitled ''Observations topographical, moral, and physiological, made on a Journey through part of the Low Countries, Germany, Italy, and France''. From this tour Ray and Willughby returned laden with collections, on which they meant to base complete systematic descriptions of the animal and vegetable kingdoms. Willughby undertook the former part, but, dying in 1672, left only an ornithology and ichthyology for Ray to edit; while Ray used the botanical collections for the groundwork of his ''Methodus plantarum nova'' (1682), and his great ''Historia generalis plantarum'' (3 vols., 1686, 1688, 1704). The plants gathered on his British tours had already been described in his ''Catalogus plantarum Angliae'' (1670), which formed the basis for later English floras.

In 1667 Ray was elected Fellow of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

, and in 1669 he and Willughby published a paper on ''Experiments concerning the Motion of Sap in Trees''. In 1671, he presented the research of Francis Jessop on formic acid to the Royal Society.

In the 1690s, he published three volumes on religion—the most popular being ''The Wisdom of God Manifested in the Works of the Creation'' (1691), an essay describing evidence that all in nature and space is God's creation as in the Bible is affirmed. In this volume, he moved on from the naming and cataloguing of species like his successor Carl Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (; 23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after his Nobility#Ennoblement, ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné#Blunt, Blunt (2004), p. 171. (), was a Swedish botanist, zoologist, taxonomist, and physician who formalise ...

. Instead, Ray considered species' lives and how nature worked as a whole, giving facts that are arguments for God's will expressed in His creation of all 'visible and invisible' (Colossians

The Epistle to the Colossians is the twelfth book of the New Testament. It was written, according to the text, by Paul the Apostle and Timothy, and addressed to the church in Colossae, a small Phrygian city near Laodicea and approximately f ...

1:16).

Ray gave an early description of dendrochronology, explaining for the ash tree how to find its age from its tree-rings.

Taxonomy

Ray's work onplant taxonomy

Plant taxonomy is the science that finds, identifies, describes, classifies, and names plants. It is one of the main branches of taxonomy (the science that finds, describes, classifies, and names living things).

Plant taxonomy is closely allied ...

spanned a wide range of thought, starting with an approach that was predominantly in the tradition of the herbalists

Herbal medicine (also herbalism) is the study of pharmacognosy and the use of medicinal plants, which are a basis of traditional medicine. With worldwide research into pharmacology, some herbal medicines have been translated into modern remed ...

and Aristotelian, but becoming increasingly theoretical and finally rejecting Aristotelianism. Despite his early adherence to Aristotelian tradition, his first botanical work, the ''Catalogus plantarum circa Cantabrigiam nascentium'' (1660), was almost entirely descriptive, being arranged alphabetically. His model was an account by Bauhin Bauhin — a family of physicians and scientists.

*Jean Bauhin (1511–1582): a French physician, who moved with his family to Basel after conversion to Protestantism.

*Two of his three sons:

**Gaspard Bauhin, or Caspar Bauhin (1560– ...

of the plants growing around Basel in 1622 and was the first English county flora, covering about 630 species. However at the end of the work he appended a brief taxonomy which he stated followed the usage of Bauhin and other herbalists.

System of classification

Ray's system, starting with his Cambridge catalogue, began with the division between the imperfect or lower plants (Cryptogams

A cryptogam (scientific name Cryptogamae) is a plant (in the wide sense of the word) or a plant-like organism that reproduces by spores, without flowers or seeds. The name ''Cryptogamae'' () means "hidden reproduction", referring to the fact ...

), and perfect (''planta perfecta'') higher plants (Seed plants

A spermatophyte (; ), also known as phanerogam (taxon Phanerogamae) or phaenogam (taxon Phaenogamae), is any plant that produces seeds, hence the alternative name seed plant. Spermatophytes are a subset of the embryophytes or land plants. They inc ...

). The latter he divided by life forms

Life form (also spelled life-form or lifeform) is an entity that is living, such as plants (flora) and animals (fauna). It is estimated that more than 99% of all species that ever existed on Earth, amounting to over five billion species, are ex ...

, e.g. trees (''arbores''), shrubs (''frutices''), subshrubs (''suffrutices'') and herbaceous plants

Herbaceous plants are vascular plants that have no persistent woody stems above ground. This broad category of plants includes many perennials, and nearly all annuals and biennials.

Definitions of "herb" and "herbaceous"

The fourth edition of t ...

(''herbae'') and lastly grouping them by common characteristics. The trees he divided into 8 groups, e.g. ''Pomiferae'' (including apple and pear). The shrubs he placed in 2 groups, ''Spinosi'' (Berberis

''Berberis'' (), commonly known as barberry, is a large genus of deciduous and evergreen shrubs from tall, found throughout temperate and subtropical regions of the world (apart from Australia). Species diversity is greatest in South Amer ...

etc.) and ''Non Spinosi'' ( Jasmine etc.). The subshrubs formed a single group and the herbs into 21 groups.

Division of Herbae;

# Bulbosae (''Lilium

''Lilium'' () is a genus of herbaceous flowering plants growing from bulbs, all with large prominent flowers. They are the true lilies. Lilies are a group of flowering plants which are important in culture and literature in much of the world. M ...

'' etc.)

# Tuberosae (''Asphodelus

''Asphodelus'' is a genus of mainly perennial flowering plants in the asphodel family Asphodelaceae that was first described by Carl Linnaeus in 1753. The genus was formerly included in the lily family (Liliaceae). The genus is native to tempera ...

'' etc.)

# Umbelliferae (''Foeniculum

''Foeniculum '' is a genus of flowering plants in the carrot family. It includes the commonly cultivated fennel, ''Foeniculum vulgare.''

;Species

*'' Foeniculum scoparium'' Quézel - North Africa

*'' Foeniculum subinodorum'' Maire, Weiller & ...

'' etc.)

# Verticellatae (''Mentha

''Mentha'' (also known as mint, from Greek , Linear B ''mi-ta'') is a genus of plants in the family Lamiaceae (mint family). The exact distinction between species is unclear; it is estimated that 13 to 24 species exist. Hybridization occurs nat ...

'' etc.)

# Spicatae (''Lysimachia

''Lysimachia'' () is a genus consisting of 193 accepted species of flowering plants traditionally classified in the family Primulaceae. Based on a molecular phylogenetic study it was transferred to the family Myrsinaceae, before this family wa ...

'' etc.)

# Scandentes (''Cucurbita

''Cucurbita'' (Latin for gourd) is a genus of herbaceous fruits in the gourd family, Cucurbitaceae (also known as ''cucurbits'' or ''cucurbi''), native to the Andes and Mesoamerica. Five edible species are grown and consumed for their flesh and ...

'' etc.)

# Corymbiferae (''Tanacetum

''Tanacetum'' is a genus of about 160 species of flowering plants in the aster family, Asteraceae, native to many regions of the Northern Hemisphere.

'')

# Pappiflorae (''Senecio

''Senecio'' is a genus of flowering plants in the daisy family (Asteraceae) that includes ragworts and groundsels.

Variously circumscribed taxonomically, the genus ''Senecio'' is one of the largest genera of flowering plants.

Description

Mor ...

'' etc.)

# Capitatae (''Scabiosa

''Scabiosa'' is a genus in the honeysuckle family (Caprifoliaceae) of flowering plants. Many of the species in this genus have common names that include the word scabious, but some plants commonly known as scabious are currently classified in r ...

'' etc.)

# Campaniformes (''Digitalis

''Digitalis'' ( or ) is a genus of about 20 species of herbaceous perennial plants, shrubs, and biennials, commonly called foxgloves.

''Digitalis'' is native to Europe, western Asia, and northwestern Africa. The flowers are tubular in shap ...

'' etc.)

# Coronariae ('' Caryophyllus'' etc.)

# Rotundifoliae (''Cyclamen

''Cyclamen'' ( or ) is a genus of 23 species of perennial flowering plants in the family Primulaceae. ''Cyclamen'' species are native to Europe and the Mediterranean Basin east to the Caucasus and Iran, with one species in Somalia. They gro ...

'' etc.)

# Nervifoliae (''Plantago

''Plantago'' is a genus of about 200 species of flowering plants in the family Plantaginaceae, commonly called plantains or fleaworts. The common name plantain is shared with the unrelated cooking plantain. Most are herbaceous plants, though ...

'' etc.)

# Stellatae (''Rubia

''Rubia'' is the type genus of the Rubiaceae family of flowering plants, which also contains coffee. It contains around 80 species of perennial scrambling or climbing herbs and subshrubs native to the Old World. The genus and its best-known sp ...

'' etc.)

# Cerealia ('' Legumina'' etc.)

# Succulentae (''Sedum

''Sedum'' is a large genus of flowering plants in the family Crassulaceae, members of which are commonly known as stonecrops. The genus has been described as containing up to 600 species, subsequently reduced to 400–500. They are leaf succul ...

'' etc.)

# Graminifoliae ('' Gramina'' etc.)

# mitted# Oleraceae ('' Beta'' etc.)

# Aquaticae ('' Nymphaea'' etc.)

# Marinae (''Fucus

''Fucus'' is a genus of brown algae found in the intertidal zones of rocky seashores almost throughout the world.

Description and life cycle

The thallus is perennial with an irregular or disc-shaped holdfast or with haptera. The erect portion o ...

'' etc.)

# Saxatiles (''Asplenium

''Asplenium'' is a genus of about 700 species of ferns, often treated as the only genus in the family Aspleniaceae, though other authors consider '' Hymenasplenium'' separate, based on molecular phylogenetic analysis of DNA sequences, a different ...

'' etc)

As outlined in his ''Historia Plantarum'' (1685–1703):

* Herbae (Herbaceous plants

Herbaceous plants are vascular plants that have no persistent woody stems above ground. This broad category of plants includes many perennials, and nearly all annuals and biennials.

Definitions of "herb" and "herbaceous"

The fourth edition of t ...

)

** Imperfectae (Cryptogams

A cryptogam (scientific name Cryptogamae) is a plant (in the wide sense of the word) or a plant-like organism that reproduces by spores, without flowers or seeds. The name ''Cryptogamae'' () means "hidden reproduction", referring to the fact ...

)

** Perfectae (Seed plants

A spermatophyte (; ), also known as phanerogam (taxon Phanerogamae) or phaenogam (taxon Phaenogamae), is any plant that produces seeds, hence the alternative name seed plant. Spermatophytes are a subset of the embryophytes or land plants. They inc ...

)

*** Monocotyledons

Monocotyledons (), commonly referred to as monocots, ( Lilianae '' sensu'' Chase & Reveal) are grass and grass-like flowering plants (angiosperms), the seeds of which typically contain only one embryonic leaf, or cotyledon. They constitute one of ...

*** Dicotyledons

The dicotyledons, also known as dicots (or, more rarely, dicotyls), are one of the two groups into which all the flowering plants (angiosperms) were formerly divided. The name refers to one of the typical characteristics of the group: namely, t ...

* Arborae (Trees

In botany, a tree is a perennial plant with an elongated stem, or trunk, usually supporting branches and leaves. In some usages, the definition of a tree may be narrower, including only woody plants with secondary growth, plants that are u ...

)

** Monocotyledons

** Dicotyledons

Definition of species

Ray was the first person to produce a biological definition ofspecies

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

, in his 1686 ''History of Plants'':

:"... no surer criterion for determining species has occurred to me than the distinguishing features that perpetuate themselves in propagation from seed. Thus, no matter what variations occur in the individuals or the species, if they spring from the seed of one and the same plant, they are accidental variations and not such as to distinguish a species... Animals likewise that differ specifically preserve their distinct species permanently; one species never springs from the seed of another nor vice versa".

Publications

Ray published about 23 works, depending on how they are counted. The biological works were usually in Latin, the rest in English. Keynes, Sir Geoffrey951

Year 951 ( CMLI) was a common year starting on Wednesday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place

Europe

* King Berengar II of Italy seizes Liguria, with help from the feudal lord Oberto I. He re ...

1976. ''John Ray, 1627–1705: a bibliography 1660–1970''. Van Heusden, Amsterdam. His first publication, while at Cambridge, was the ''Catalogus plantarum circa Cantabrigiam nascentium'' (1660), followed by many works, botanical, zoological,theological and literary. Until 1670, he wrote his name as John Wray. From then on, he used 'Ray', after "having ascertained that such had been the practice of his family before him".

List of selected publications

* Appendices 1663, 1685 ** ** * 1668: ''Tables of plants'', inJohn Wilkins

John Wilkins, (14 February 1614 – 19 November 1672) was an Anglican clergyman, natural philosopher, and author, and was one of the founders of the Royal Society. He was Bishop of Chester from 1668 until his death.

Wilkins is one of the f ...

' ''Essay

An essay is, generally, a piece of writing that gives the author's own argument, but the definition is vague, overlapping with those of a letter, a paper, an article, a pamphlet, and a short story. Essays have been sub-classified as formal a ...

''

*

* 1670: ''Collection of English proverbs''.

* 1673: ''Observations in the Low Countries and Catalogue of plants not native to England''.

* 1674: ''Collection of English words not generally used'online

* 1675: ''Trilingual dictionary, or nomenclator classicus''. * 1676

''Willughby's Ornithologia''

* *

* 1686: ''History of fishes''. * 1686–1704: ''Historia plantarum species'' 'History of plants'' London:Clark 3 vols; *

Vol 1 1686

(in Latin) *

Lazenby, Elizabeth Mary (1995). The Historia Plantarum Generalis of John Ray, Book I : a translation and commentary. PhD thesis Newcastle University

* ** 2nd ed 1696 * 1691

''The wisdom of God Manifested in the Works of the Creation'' 7th ed.

2nd ed 1692, 3rd ed 1701, 4th ed 1704, 7th ed 1717 * 1692

''Miscellaneous discourses concerning the dissolution and changes of the world''

* 1693:

Synopsis of animals and reptiles

'. * 1693: ''Collection of travels''. * 1694: ''Collection of European plants''. * 1695: ''Plants of each county''. (Camden's Britannia) * *

* 1700: ''A persuasive to a holy life''. * ;Posthumous * 1705. ''Method and history of insects'' * 1713: '

Synopsis methodica avium & piscium: opus posthumum (''Synopsis of birds and fishes'')'', in Latin. William Innys, London

vol. 1: ''Avium'' vol. 2: ''Piscium'' * 171

''Three Physico-theological discourses''

* *

Facsimile edition 197

Ray Society, London. With introduction by

William T. Stearn

William Thomas Stearn (16 April 1911 – 9 May 2001) was a British botanist. Born in Cambridge in 1911, he was largely self-educated, and developed an early interest in books and natural history. His initial work experience was at a ...

.

** Fourth edition 1760

Libraries holding Ray's works

Including the various editions, there are 172 works of Ray, of which most are rare. The only libraries with substantial holdings are all in England.p153 The list in order of holdings is: :TheBritish Library

The British Library is the national library of the United Kingdom and is one of the largest libraries in the world. It is estimated to contain between 170 and 200 million items from many countries. As a legal deposit library, the British ...

, Euston, London. Holds over 80 of the editions.

:The Bodleian Library, University of Oxford.

:The University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

Library.

:Library of Trinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Founded in 1546 by King Henry VIII, Trinity is one of the largest Cambridge colleges, with the largest financial endowment of any college at either Cambridge or Oxford. ...

.

:The Natural History Museum

A natural history museum or museum of natural history is a scientific institution with natural history collections that include current and historical records of animals, plants, fungi, ecosystems, geology, paleontology, climatology, and more. ...

Library, South Kensington, London.

:The John Rylands Library

The John Rylands Research Institute and Library is a Victorian era, late-Victorian Gothic Revival architecture, neo-Gothic building on Deansgate in Manchester, England. It is part of the University of Manchester. The library, which opened to t ...

, University of Manchester, Deansgate, Manchester

:The Sobrang Bayabas, University of Bayabas

Legacy

Ray's biographer, Charles Raven, commented that "Ray sweeps away the litter of mythology and fable... and always insists upon accuracy of observation and description and the testing of every new discovery".p10 Ray's works were directly influential on the development of taxonomy by

Ray's biographer, Charles Raven, commented that "Ray sweeps away the litter of mythology and fable... and always insists upon accuracy of observation and description and the testing of every new discovery".p10 Ray's works were directly influential on the development of taxonomy by Carl Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (; 23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after his Nobility#Ennoblement, ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné#Blunt, Blunt (2004), p. 171. (), was a Swedish botanist, zoologist, taxonomist, and physician who formalise ...

.

The Ray Society, named after John Ray, was founded in 1844. It is a scientific text publication society

A text publication society is a learned society which publishes (either as its sole function, or as a principal function) scholarly editions of old works of historical or literary interest, or archival documents. In addition to full texts, a text p ...

and registered charity, based at the Natural History Museum, London

The Natural History Museum in London is a museum that exhibits a vast range of specimens from various segments of natural history. It is one of three major museums on Exhibition Road in South Kensington, the others being the Science Museum an ...

, which exists to publish books on natural history, with particular (but not exclusive) reference to the flora and fauna of the British Isles. As of 2017, the Society had published 179 volumes.

The John Ray Society (a separate organisation) is the Natural Sciences Society at St Catharine's College, Cambridge. It organises a programme of events of interest to science students in the college.

In 1986, to mark the 300th anniversary of the publication of Ray's ''Historia Plantarum'', there was a celebration of Ray's legacy in Braintree, Essex

Braintree is a town and former civil parish in Essex, England. The principal settlement of Braintree District, it is located northeast of Chelmsford and west of Colchester. According to the 2011 Census, the town had a population of 41,634, ...

. A "John Ray Gallery" was opened in the Braintree Museum.

The John Ray Initiative (JRI) is an educational charity

Charity may refer to:

Giving

* Charitable organization or charity, a non-profit organization whose primary objectives are philanthropy and social well-being of persons

* Charity (practice), the practice of being benevolent, giving and sharing

* C ...

that seeks to reconcile scientific and Christian understandings of the environment. It was formed in 1997 in response to the global environmental crisis and the challenges of sustainable development and environmental stewardship. John Ray's writings proclaimed God as creator whose wisdom is "manifest in the works of creation", and as redeemer of all things. JRI aims to teach appreciation of nature, increase awareness of the state of the global environment, and to promote a Christian understanding of environmental issues.

See also

*Monocotyledons

Monocotyledons (), commonly referred to as monocots, ( Lilianae '' sensu'' Chase & Reveal) are grass and grass-like flowering plants (angiosperms), the seeds of which typically contain only one embryonic leaf, or cotyledon. They constitute one of ...

Notes

References

Bibliography

Books

* * * * (alshere

at Biodiversity Heritage Library) * * See als

ebook 2010

* * * , see also * * * , in

Articles

* *Websites

* , see also Ray SocietyJohn Ray's works at the

Biodiversity Heritage Library

External links

John Ray Biography

The first biological species concept (Evolving Thoughts)

''Memoir of John Ray''

by James Duncan

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

John Ray and taxonomy. King's College London

Encyclopaedia Britannica

Dictionary of Scientific Biography

John Ray Initiative

The John Ray Initiative: connecting Environment and Christianity

*

*

{{DEFAULTSORT:Ray, John 1628 births 1705 deaths Phycologists Alumni of St Catharine's College, Cambridge Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge Botanists with author abbreviations English naturalists Bryologists 17th-century English botanists Fellows of the Royal Society Paleobotanists People from Black Notley Parson-naturalists 17th-century Protestants 17th-century English writers 17th-century English male writers 18th-century English writers 18th-century English male writers Burials in Essex Writers about religion and science