Julius Fučík (journalist) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Julius Fučík () (23 February 1903 – 8 September 1943) was a

Julius Fučík () (23 February 1903 – 8 September 1943) was a

The position and reverence of Fučík during Communist Czechoslovakia is depicted by Milan Kundera in his book ''The Joke'' from 1967. There he describes how the portrait of Fučík hangs in public buildings where public expulsions from the Communist Party took place, and how Fučík's book is recited and used as propaganda by the Communist party.

"I recognized Fučík's Notes from the Gallows...That text, written clandestinely in prison, then published after the war in a million copies, broadcast over the radio, studied in schools as required reading, was the sacred book of the era."

The position and reverence of Fučík during Communist Czechoslovakia is depicted by Milan Kundera in his book ''The Joke'' from 1967. There he describes how the portrait of Fučík hangs in public buildings where public expulsions from the Communist Party took place, and how Fučík's book is recited and used as propaganda by the Communist party.

"I recognized Fučík's Notes from the Gallows...That text, written clandestinely in prison, then published after the war in a million copies, broadcast over the radio, studied in schools as required reading, was the sacred book of the era."

Review of Notes from the Gallows

1948

Biography

{{DEFAULTSORT:Fucik, Julius 1903 births 1943 deaths Writers from Prague People from the Kingdom of Bohemia Communist Party of Czechoslovakia politicians Czech journalists Czech male writers Memoirs of imprisonment Executed writers Communists executed by Nazi Germany Czech people executed by Nazi Germany People executed by hanging at Plötzensee Prison Resistance members killed by Nazi Germany 20th-century journalists Czech anti-fascists Charles University alumni

Julius Fučík () (23 February 1903 – 8 September 1943) was a

Julius Fučík () (23 February 1903 – 8 September 1943) was a Czech

Czech may refer to:

* Anything from or related to the Czech Republic, a country in Europe

** Czech language

** Czechs, the people of the area

** Czech culture

** Czech cuisine

* One of three mythical brothers, Lech, Czech, and Rus

*Czech (surnam ...

journalist, critic, writer, and active member of Communist Party of Czechoslovakia

The Communist Party of Czechoslovakia ( Czech and Slovak: ''Komunistická strana Československa'', KSČ) was a communist and Marxist–Leninist political party in Czechoslovakia that existed between 1921 and 1992. It was a member of the Com ...

. For his part at the forefront of the anti-Nazi resistance during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, he was imprisoned and tortured by the Gestapo

The (, ), Syllabic abbreviation, abbreviated Gestapo (), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of F ...

in Prague

Prague ( ; ) is the capital and List of cities and towns in the Czech Republic, largest city of the Czech Republic and the historical capital of Bohemia. Prague, located on the Vltava River, has a population of about 1.4 million, while its P ...

, and executed in Berlin

Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List of cities in Germany by population, population. With 3.7 million inhabitants, it has the List of cities in the European Union by population withi ...

. While in prison, Fučík recorded his interrogation experiences on small pieces of paper, which were smuggled out and published after the war as '' Notes from the Gallows''. The book established Fučík as a symbol of resistance to oppression, as well as an icon of communist propaganda.

Early life

Julius Fučík was born into a working-class family inPrague

Prague ( ; ) is the capital and List of cities and towns in the Czech Republic, largest city of the Czech Republic and the historical capital of Bohemia. Prague, located on the Vltava River, has a population of about 1.4 million, while its P ...

. His father was a steelworker and opera singer, and his uncle and namesake was the composer Julius Fučík. In 1913, Fučík moved with his family from Prague to Plzeň

Plzeň (), also known in English and German as Pilsen (), is a city in the Czech Republic. It is the Statutory city (Czech Republic), fourth most populous city in the Czech Republic with about 188,000 inhabitants. It is located about west of P ...

(Pilsen) where he attended the state vocational high school. Already as a twelve-year-old boy he was planning to establish a newspaper named ''Slovan'' (The Slav). He showed himself to be interested in both politics and literature. As a teenager he frequently acted in local amateur theatre.

Journalism and politics

In 1920 he took up study in Prague and joined the Czechoslovak Social Democratic Workers' Party, through which he was later to find himself swept up in the left-wing current. In May 1921 this wing founded theCommunist Party of Czechoslovakia

The Communist Party of Czechoslovakia ( Czech and Slovak: ''Komunistická strana Československa'', KSČ) was a communist and Marxist–Leninist political party in Czechoslovakia that existed between 1921 and 1992. It was a member of the Com ...

(CPC). Fučík then first wrote cultural contributions for the local Plzeň CPC newspaper.

After completing his studies, Fučík found a position as an editor with the literary newspaper ''Kmen'' ("Stem"). Within the CPC he became responsible for cultural work. He was a member of the literary and artistic group Devětsil from 1926 and in 1929 helped the creation of its more politically motivated successor, Left Front. In the year 1929 he went to literary critic

A genre of arts criticism, literary criticism or literary studies is the study, evaluation, and interpretation of literature. Modern literary criticism is often influenced by literary theory, which is the philosophical analysis of literature' ...

František Xaver Šalda's magazine ''Tvorba'' ("Creation"). Moreover, he constantly worked on the CPC newspaper '' Rudé právo'' ("Red Right") and several other journals. In this time Fučík was arrested repeatedly by the Czechoslovak Secret Police, managing to avoid an eight-month prison sentence in 1934.

In 1930, he visited the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

for four months, including the Czechoslovak collectivist

In sociology, a social organization is a pattern of relationships between and among individuals and groups. Characteristics of social organization can include qualities such as sexual composition, spatiotemporal cohesion, leadership, struct ...

colony Interhelpo in Central Asia

Central Asia is a region of Asia consisting of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. The countries as a group are also colloquially referred to as the "-stans" as all have names ending with the Persian language, Pers ...

, and painted a very positive picture of the situation there in the book ''V zemi, kde zítra již znamená včera'' ("In a Land, Where Tomorrow is Already Yesterday", published in 1932). Fučík supported collectivization

Collective farming and communal farming are various types of "agricultural production in which multiple farmers run their holdings as a joint enterprise". There are two broad types of communal farms: agricultural cooperatives, in which member- ...

, and dekulakization

Dekulakization (; ) was the Soviet campaign of Political repression in the Soviet Union#Collectivization, political repressions, including arrests, deportations, or executions of millions of supposed kulaks (prosperous peasants) and their familie ...

; praised the successes of industrialization

Industrialisation (British English, UK) American and British English spelling differences, or industrialization (American English, US) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an i ...

, and emphasized the temporary nature of all difficulties. In particular, having visited the USSR on the eve of the Holodomor

The Holodomor, also known as the Ukrainian Famine, was a mass famine in Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, Soviet Ukraine from 1932 to 1933 that killed millions of Ukrainians. The Holodomor was part of the wider Soviet famine of 1930–193 ...

of 1932-1933, he categorically supported the policy of the Soviet regime. In July 1934, just after Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

had suppressed the SA, he visited Bavaria

Bavaria, officially the Free State of Bavaria, is a States of Germany, state in the southeast of Germany. With an area of , it is the list of German states by area, largest German state by land area, comprising approximately 1/5 of the total l ...

and described his experiences in ''Cesta do Mnichova'' ("The Road to Munich

Munich is the capital and most populous city of Bavaria, Germany. As of 30 November 2024, its population was 1,604,384, making it the third-largest city in Germany after Berlin and Hamburg. Munich is the largest city in Germany that is no ...

"). He went to the Soviet Union again in 1934, this time for two years, and wrote various reports, which again worked to support the Party's strength. After his return, there were heated arguments with authors such as Jiří Weil and Jan Slavík, who criticized developments under Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

. Fučík took the Stalinist side and criticized such statements critical of Stalin as fatal to the CPC.

In 1938 Fučík married Augusta Kodeřičová, later known as Gusta Fučíková.

In the wake of the Munich Conference, the Prague government disbanded the CPC from September 1938 and the CPC went underground. After Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

's troops invaded Czechoslovakia in March 1939, Fučík moved to his parents' house in Chotiměř ( Litoměřice District) and published in civilian newspapers, especially about historical and literary topics. He also started to work for the now underground CPC. In 1940 the Gestapo started to search for him in Chotiměř because of his cooperation with the CPC, and so he decided to move back to Prague.

Beginning early in 1941, he belonged to the CPC's Central Committee. He provided handbills and tried to publish the Communist Party newspaper ''Rudé Právo'' regularly. On 24 April 1942 he and six others were arrested in Prague by the Gestapo

The (, ), Syllabic abbreviation, abbreviated Gestapo (), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of F ...

, probably rather coincidentally during a police raid. Although Fučík had two guns at the time, he did not use them. The only survivor of the incident, Riva Friedová-Krieglová, claimed in the 1990s that Fučík had orders to shoot himself to avoid capture.

''Notes from the Gallows''

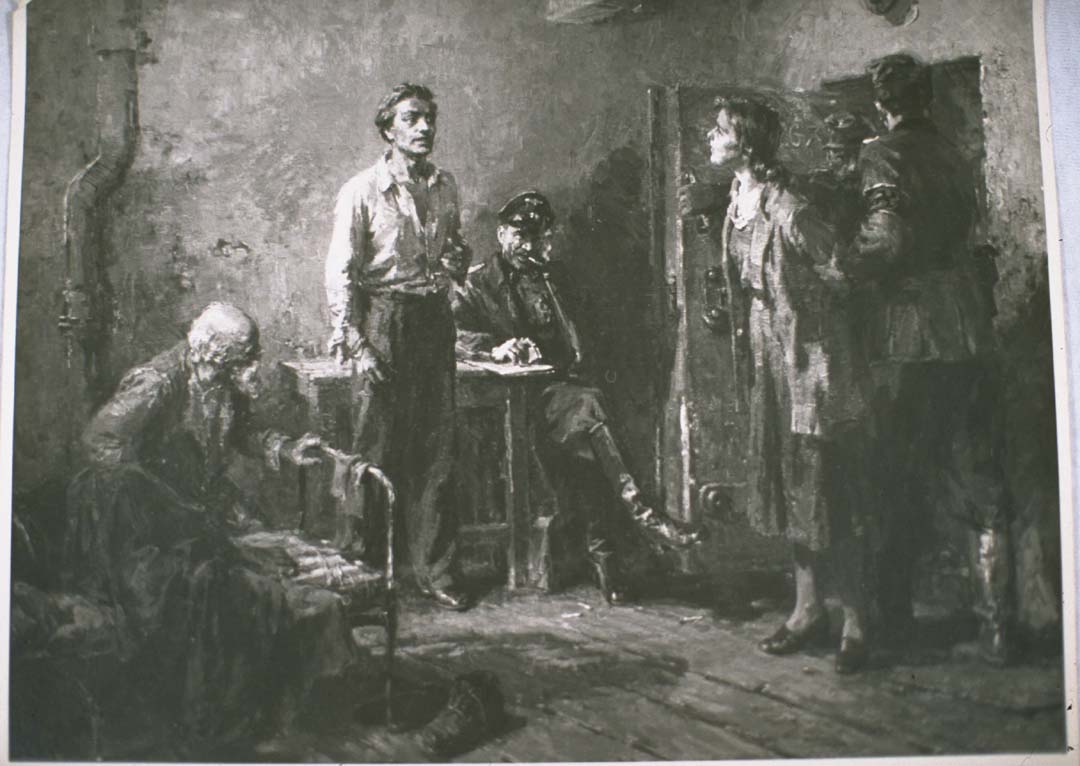

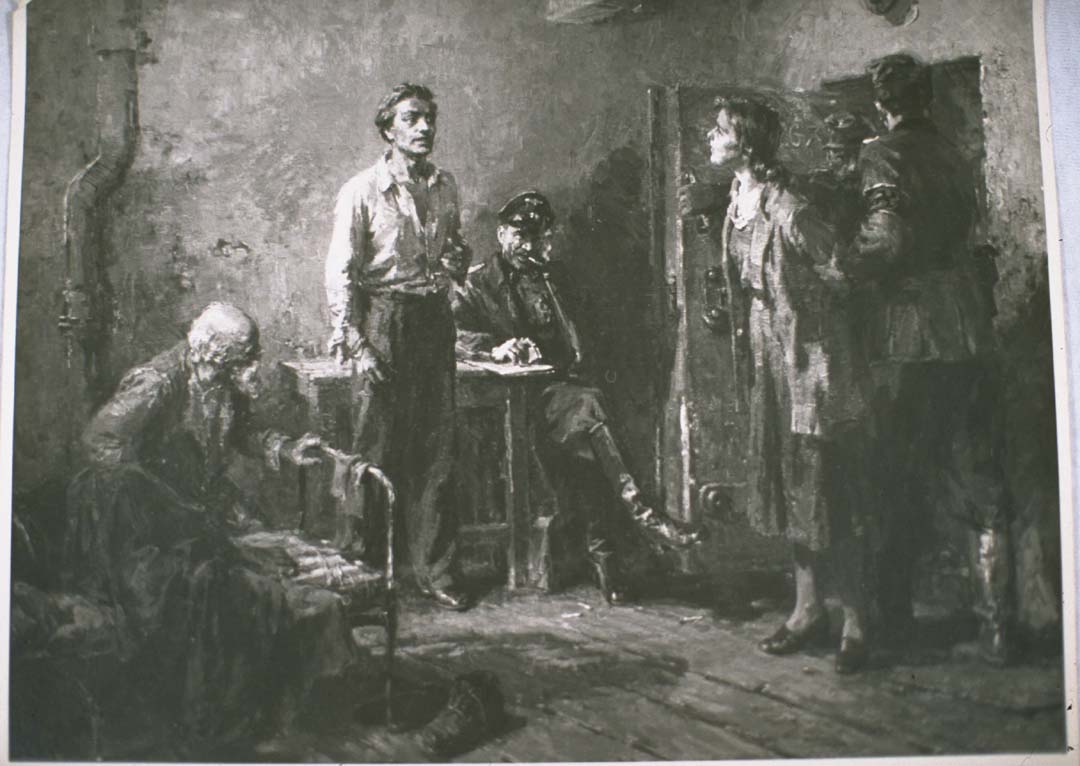

Fučík was initially detained in Pankrác Prison in Prague, where he was interrogated and tortured. In this time he composed '' Notes from the Gallows'' (, literally ''Reports Written Under the Noose''), by writing on pieces of cigarette paper and smuggling them out with the help of sympathetic prison warders named Kolínský and Hora. The book describes events in the prison and is filled with hope for a communist future. He also details mental resistance techniques to help withstand torture, which have since been used by activists around the world. In the original edition, certain passages that jarred with common notions of heroic resistance were omitted. A later edition, published in 1995, restored the missing text. Although the work's authenticity has been contested, a forensic analysis by the Prague Institute of Criminalistics found the manuscript to be genuine.Trial and death

In May 1943 Fučík was brought to Germany. He was first detained inBautzen

Bautzen () or Budyšin (), until 1868 ''Budissin'' in German, is a town in eastern Saxony, Germany, and the administrative centre of the Bautzen (district), district of Bautzen. It is located on the Spree (river), Spree river, is the eighth most ...

for somewhat more than two months, and afterwards in Berlin. On 25 August 1943 in Berlin, he was accused of high treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its d ...

in connection with his political activities by the ''Volksgerichtshof'', which was presided over by the notorious Roland Freisler. Fučík was found guilty and was sentenced to death along with Jaroslav Klecan, who had been arrested with Fučík. Fučík was hanged two weeks later on 8 September 1943 in Plötzensee Prison in Berlin (not beheaded as is often stated).

After the war, his wife, Gusta Fučíková, who had also been in a Nazi concentration camp

A concentration camp is a prison or other facility used for the internment of political prisoners or politically targeted demographics, such as members of national or ethnic minority groups, on the grounds of national security, or for exploitati ...

, researched and retrieved all of his prison writings. She edited them with help of CPC and published them as ''Notes from the Gallows'' in 1947. The book was successful, and its influence increased after the Stalinist takeover of Czechoslovakia in 1948. It has been translated into at least 90 languages.

Fučík as an ideological symbol

The Party found Julius Fučík and his book convenient for use aspropaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded l ...

and turned them into one of the most visible symbols of the Party. The book was required reading in schools and by the age of 10 every pupil growing up in communist Czechoslovakia was familiar with Fučík's work and life. Fučík became a hero whose portrait was displayed at political meetings. Gusta Fučíková was given a high position in the Party hierarchy (the chairmanship of a women's organization), holding it for decades.

Many places were named after Fučík, among them a large entertainment park in Prague (''Park kultury a oddechu Julia Fučíka''), the city theatre in Jablonec nad Nisou

Jablonec nad Nisou (; ) is a city in the Liberec Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 46,000 inhabitants. It is the second-largest city in the region. It is a local centre for education, and is known for its glass and jewelry production, espe ...

(1945–98), a factory in Brno

Brno ( , ; ) is a Statutory city (Czech Republic), city in the South Moravian Region of the Czech Republic. Located at the confluence of the Svitava (river), Svitava and Svratka (river), Svratka rivers, Brno has about 403,000 inhabitants, making ...

(''Elektrotechnické závody Julia Fučíka''), a military unit, and countless streets and squares. In December 2022 the Julius Fučík street in Kyiv

Kyiv, also Kiev, is the capital and most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city of Ukraine. Located in the north-central part of the country, it straddles both sides of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2022, its population was 2, ...

, Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

was renamed to Karel Čapek

Karel Čapek (; 9 January 1890 – 25 December 1938) was a Czech writer, playwright, critic and journalist. He has become best known for his science fiction, including his novel '' War with the Newts'' (1936) and play '' R.U.R.'' (''Rossum' ...

street.

In 1955, Milan Kundera

Milan Kundera ( ; ; 1 April 1929 – 11 July 2023) was a Czech and French novelist. Kundera went into exile in France in 1975, acquiring citizenship in 1981. His Czechoslovak citizenship was revoked in 1979, but he was granted Czech citizenship ...

published a poetic tale entitled ''Poslední máj'' (''The Last May'') that depicts an encounter between Fučík and his Nazi interrogators.

The ''Julius Fučík'' (''Юлиус Фучик'') was a Soviet

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

and later Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

n barge carrier. In Tom Clancy's 1986 novel '' Red Storm Rising'', about a hypothetical war between the Warsaw Pact and NATO, this ship was given the role of being used for the Soviet invasion of Iceland.

The composer Luigi Nono wrote a musical piece titled ''Julius Fučík'' based on '' Notes from the Gallows''.

References in popular culture

The position and reverence of Fučík during Communist Czechoslovakia is depicted by Milan Kundera in his book ''The Joke'' from 1967. There he describes how the portrait of Fučík hangs in public buildings where public expulsions from the Communist Party took place, and how Fučík's book is recited and used as propaganda by the Communist party.

"I recognized Fučík's Notes from the Gallows...That text, written clandestinely in prison, then published after the war in a million copies, broadcast over the radio, studied in schools as required reading, was the sacred book of the era."

The position and reverence of Fučík during Communist Czechoslovakia is depicted by Milan Kundera in his book ''The Joke'' from 1967. There he describes how the portrait of Fučík hangs in public buildings where public expulsions from the Communist Party took place, and how Fučík's book is recited and used as propaganda by the Communist party.

"I recognized Fučík's Notes from the Gallows...That text, written clandestinely in prison, then published after the war in a million copies, broadcast over the radio, studied in schools as required reading, was the sacred book of the era."

Reassessment

After the Party lost its power in 1989, the legend of Fučík became a target of scrutiny. It was made public that some parts of the book ''Notes from the Gallows'' (around 2%) had been omitted and that the text had been "sanitized" by Gusta Fučíková. There were speculations as to how much information he gave his torturers, and whether he had turned traitor. In 1995 the complete text of the book was published. The part in which Fučík describes how he succumbed to torture was published for the first time. In it, one learns that Fučík gave false information to his captors, saving countless lives among the Czech resistance to the Nazis. The historian Alena Hájková coedited the critical edition of Fučík's memoir.Notes

Selected works

Reports

* ''Reportáže z buržoazní republiky'', published in journals, collected in 1948 * ''V zemi, kde zítra již znamená včera'', about the Soviet Union, 1932 * ''V zemi milované'', about the Soviet Union, published posthumously in 1949 * ''Reportáž psaná na oprátce'' (''Notes from the Gallows''), 1947, complete text in 1995, many editions and translationsTheatrical critiques and literary essays

* ''Milujeme svoji zem'', 1948 * ''Stati o literatuře'', 1951 * ''Božena Němcová bojující'', ''O Sabinově zradě'', ''Chůva'' published in ''Tři studie'', 1947.Other

* ''Pokolení před Petrem'', an autobiographical novel, unfinished, 1939See also

* Julius Fučík (1872–1916), composer and Fučík's uncle.References

* ''Notes from the Gallows'', * Radko Šťastný: ''Čeští spisovatelé deseti století'', Prague 2001,External links

* * Howard FastReview of Notes from the Gallows

1948

Biography

{{DEFAULTSORT:Fucik, Julius 1903 births 1943 deaths Writers from Prague People from the Kingdom of Bohemia Communist Party of Czechoslovakia politicians Czech journalists Czech male writers Memoirs of imprisonment Executed writers Communists executed by Nazi Germany Czech people executed by Nazi Germany People executed by hanging at Plötzensee Prison Resistance members killed by Nazi Germany 20th-century journalists Czech anti-fascists Charles University alumni