John Young (astronaut) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Watts Young (September 24, 1930 – January 5, 2018) was an American

In April 1964, Young was selected as the pilot of Gemini 3, commanded by Gus Grissom. The crew had originally been Alan Shepard and

In April 1964, Young was selected as the pilot of Gemini 3, commanded by Gus Grissom. The crew had originally been Alan Shepard and

After Gemini 3, Grissom and Young were assigned as backup commander and pilot for

After Gemini 3, Grissom and Young were assigned as backup commander and pilot for

Young was originally assigned as backup to the second crewed Apollo mission, along with Thomas P. Stafford and

Young was originally assigned as backup to the second crewed Apollo mission, along with Thomas P. Stafford and

Young was assigned the backup commander of

Young was assigned the backup commander of

In March 1978, Young was selected by George W. S. Abbey, then deputy director of the

In March 1978, Young was selected by George W. S. Abbey, then deputy director of the

As the chief of the Astronaut Office, Young recommended the crews that flew on the subsequent test and operational Space Shuttle missions. Young would routinely sit in the simulators alongside the crews to determine their effectiveness, and he flew the Shuttle Training Aircraft (STA) to test landing approaches prior to the orbiter landing.

In 1983, Young flew as the commander of

As the chief of the Astronaut Office, Young recommended the crews that flew on the subsequent test and operational Space Shuttle missions. Young would routinely sit in the simulators alongside the crews to determine their effectiveness, and he flew the Shuttle Training Aircraft (STA) to test landing approaches prior to the orbiter landing.

In 1983, Young flew as the commander of

Following his retirement, Young worked as a public speaker, and advocated for the importance of asteroid impact avoidance, colonization of the Moon, and climate engineering. In April 2006, Young and Crippen appeared at the 25th anniversary of the STS-1 launch at the Kennedy Space Center and spoke of their experiences during the flight. In November 2011, Young and Crippen met with the crew of STS-135, the last Space Shuttle mission.

In 2012, Young and

Following his retirement, Young worked as a public speaker, and advocated for the importance of asteroid impact avoidance, colonization of the Moon, and climate engineering. In April 2006, Young and Crippen appeared at the 25th anniversary of the STS-1 launch at the Kennedy Space Center and spoke of their experiences during the flight. In November 2011, Young and Crippen met with the crew of STS-135, the last Space Shuttle mission.

In 2012, Young and

Interview with John W. Young

for the ''

astronaut

An astronaut (from the Ancient Greek (), meaning 'star', and (), meaning 'sailor') is a person trained, equipped, and deployed by a human spaceflight program to serve as a commander or crew member aboard a spacecraft. Although generally r ...

, naval officer and aviator

An aircraft pilot or aviator is a person who controls the flight of an aircraft by operating its Aircraft flight control system, directional flight controls. Some other aircrew, aircrew members, such as navigators or flight engineers, are al ...

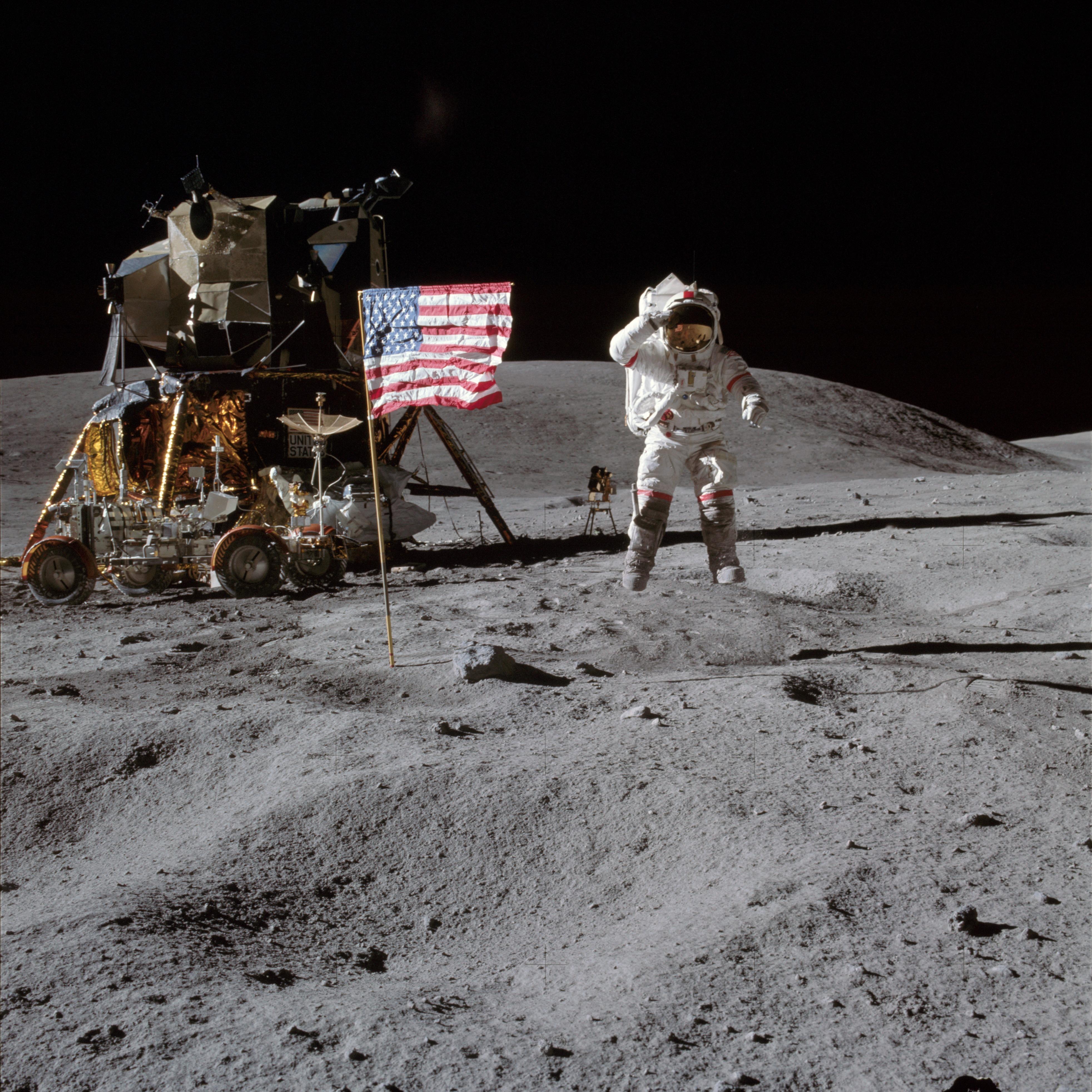

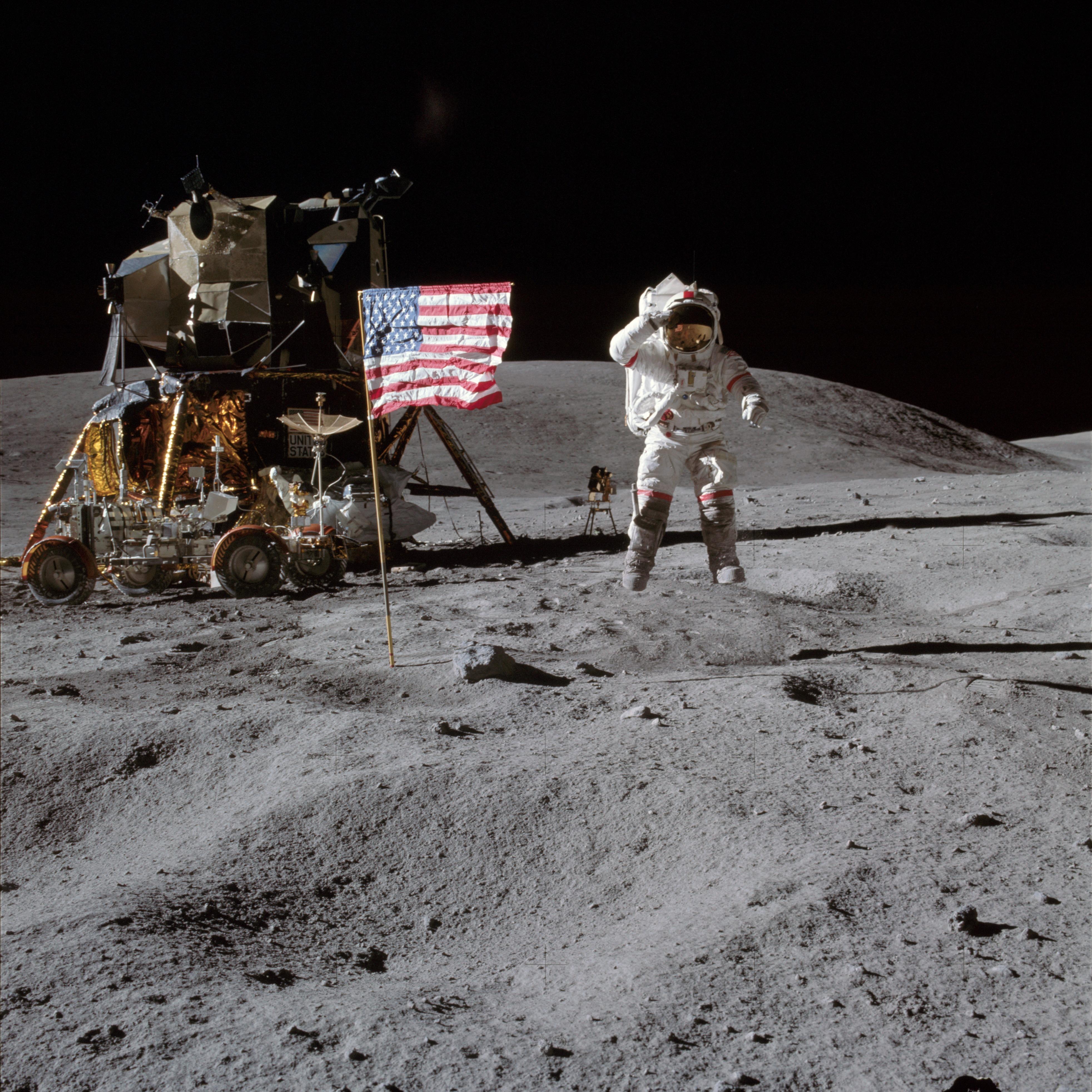

, test pilot, and aeronautical engineer. He became the ninth person to walk on the Moon as commander

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countries this naval rank is termed frigate captain.

...

of the Apollo 16

Apollo 16 (April 1627, 1972) was the tenth crewed mission in the United States Apollo space program, administered by NASA, and the fifth and penultimate to land on the Moon. It was the second of Apollo's " J missions", with an extended sta ...

mission in 1972. He is the only astronaut to fly on four different classes of spacecraft: Gemini, the Apollo command and service module, the Apollo Lunar Module

The Apollo Lunar Module (LM ), originally designated the Lunar Excursion Module (LEM), was the lunar lander spacecraft that was flown between lunar orbit and the Moon's surface during the United States' Apollo program. It was the first crewed ...

and the Space Shuttle.

Before becoming an astronaut, Young received his Bachelor of Science degree in Aeronautical Engineering from the Georgia Institute of Technology

The Georgia Institute of Technology, commonly referred to as Georgia Tech or, in the state of Georgia, as Tech or The Institute, is a public research university and institute of technology in Atlanta, Georgia. Established in 1885, it is part of ...

and joined the U.S. Navy. After serving at sea during the Korean War he became a naval aviator and graduated from the U.S. Naval Test Pilot School

The United States Naval Test Pilot School (USNTPS), located at Naval Air Station (NAS) Patuxent River in Patuxent River, Maryland, provides instruction to experienced United States Navy, Marine Corps, Army, Air Force, and foreign military experi ...

. As a test pilot, he set several world time-to-climb records. Young retired from the Navy in 1976 with the rank of captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

.

In 1962, Young was selected as a member of NASA Astronaut Group 2. He flew on the first crewed Gemini mission ( Gemini 3) in 1965, and then commanded the 1966 Gemini 10 mission. In 1969, he flew as the command module pilot on Apollo 10. In 1972, he commanded Apollo 16

Apollo 16 (April 1627, 1972) was the tenth crewed mission in the United States Apollo space program, administered by NASA, and the fifth and penultimate to land on the Moon. It was the second of Apollo's " J missions", with an extended sta ...

and spent three days on the lunar surface exploring the Descartes Highlands

The Descartes Highlands is an area of lunar highlands located on the near side that served as the landing site of the American Apollo 16 mission in early 1972. The Descartes Highlands is located in the area surrounding Descartes crater, after whi ...

with Charles Duke. Young also commanded STS-1 in 1981, the Space Shuttle program's first launch, and STS-9

STS-9 (also referred to Spacelab 1) was the ninth NASA Space Shuttle mission and the sixth mission of the Space Shuttle ''Columbia''. Launched on 28 November 1983, the ten-day mission carried the first Spacelab laboratory module into orbit.

...

in 1983, both of which were on . He was one of only two astronauts, along with Ken Mattingly, his command module pilot during the Apollo 16 mission, to fly on both an Apollo mission and a Space Shuttle mission, and the only astronaut to walk on the moon and fly on the Space Shuttle. Young served as Chief of the Astronaut Office from 1974 to 1987, and retired from NASA in 2004, after 42 years of service.

Early years and education

John Watts Young was born at St. Luke's Hospital in San Francisco, California, on September 24, 1930, to William Young, a civil engineer, and Wanda Young (). His father lost his job during theGreat Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

, and the family moved to Cartersville, Georgia, in 1932. In 1936, the family moved to Orlando, Florida

Orlando () is a city in the U.S. state of Florida and is the county seat of Orange County, Florida, Orange County. In Central Florida, it is the center of the Greater Orlando, Orlando metropolitan area, which had a population of 2,509,831, acco ...

, where he attended Princeton Elementary School. When Young was five years old, his mother was diagnosed with schizophrenia and taken to Florida State Hospital. Soon after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Young's father joined the U.S. Navy as a Seabee and left Young and his younger brother Hugh in the care of a housekeeper. Young's father returned after the war and became a plant superintendent for a citrus company. Young attended Orlando High School, where he competed in football

Football is a family of team sports that involve, to varying degrees, kicking a ball to score a goal. Unqualified, the word ''football'' normally means the form of football that is the most popular where the word is used. Sports commonly c ...

, baseball, and track and field, before he graduated in 1948.

Young attended the Georgia Institute of Technology on a Naval ROTC scholarship. He completed a midshipman

A midshipman is an officer of the lowest rank, in the Royal Navy, United States Navy, and many Commonwealth navies. Commonwealth countries which use the rank include Canada (Naval Cadet), Australia, Bangladesh, Namibia, New Zealand, South Afr ...

cruise aboard , where he worked alongside his future Apollo 10 crewmate Thomas P. Stafford

Thomas Patten Stafford (born September 17, 1930) is an American former Air Force officer, test pilot, and NASA astronaut, and one of 24 people who flew to the Moon. He also served as Chief of the Astronaut Office from 1969 to 1971.

After grad ...

, and another aboard . His senior year, Young served as regiment commander of his ROTC detachment. He was a member of the honor societies Scabbard and Blade

Scabbard and Blade (S&B) is a college military honor society founded at the University of Wisconsin in 1904. Although membership is open to Reserve Officers' Training Corps (ROTC) cadets and midshipmen of all military services, the society is mod ...

, Tau Beta Pi

The Tau Beta Pi Association (commonly Tau Beta Pi, , or TBP) is the oldest engineering honor society and the second oldest collegiate honor society in the United States. It honors engineering students in American universities who have shown a ...

, Omicron Delta Kappa

Omicron Delta Kappa (), also known as The Circle and ODK, is one of the most prestigious honor societies in the United States with chapters at more than 300 college campuses. It was founded December 3, 1914, at Washington and Lee University in ...

, Phi Kappa Phi, ANAK Society, and the Sigma Chi fraternity. In 1952, Young graduated second in his class with a Bachelor of Science degree in aeronautical engineering and was commissioned as an ensign in the U.S. Navy on June 6, 1952.

Navy service

Young applied to become a naval aviator, but was selected to become a gunnery officer aboard out ofNaval Base San Diego

Naval Base San Diego, also known as 32nd Street Naval Station, is the second largest surface ship base of the United States Navy and is located in San Diego, California. Naval Base San Diego is the principal homeport of the Pacific Fleet, cons ...

. He completed a Pacific deployment as a fire control and division officer on ''Laws'' in the Sea of Japan during the Korean War. In May 1953, he received orders to flight school at Naval Air Station Pensacola. Young first flew the SNJ-5 Texan in flight school and was then selected for helicopter training. He flew the HTL-5 and HUP-2 helicopters and completed helicopter training in January 1954. Young returned to flying the SNJ-5, and advanced to fly the T-28 Trojan, F6F Hellcat, and the F9F Panther. He graduated from flight school and received his aviator wings in December 1954.

After flight school, Young was assigned to Fighter Squadron 103 (VF-103) at NAS Cecil Field to fly the F9F Cougar. In August 1956, he deployed with the Sixth Fleet

The Sixth Fleet is a numbered fleet of the United States Navy operating as part of United States Naval Forces Europe. The Sixth Fleet is headquartered at Naval Support Activity Naples, Italy. The officially stated mission of the Sixth Fleet in ...

aboard to the Mediterranean Sea. Young flew during the Suez Crisis

The Suez Crisis, or the Second Arab–Israeli war, also called the Tripartite Aggression ( ar, العدوان الثلاثي, Al-ʿUdwān aṯ-Ṯulāṯiyy) in the Arab world and the Sinai War in Israel,Also known as the Suez War or 1956 Wa ...

, but did not fly in combat. His squadron returned in February 1957, and later that year began the transition to fly the F8U Crusader. In September 1958, VF-103 deployed with the Sixth Fleet on to the Mediterranean Sea. In January 1959, Young was selected to be in Class 23 at the United States Naval Test Pilot School and returned home from deployment.

In 1959, Young graduated second in his class and was assigned to the Armament Division at the Naval Air Test Center

Naval Air Station Patuxent River , also known as NAS Pax River, is a United States naval air station located in St. Mary’s County, Maryland, on the Chesapeake Bay near the mouth of the Patuxent River.

It is home to Headquarters, Naval Air Sys ...

. He worked alongside future astronaut James A. Lovell Jr. and tested the F-4 Phantom II

The McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II is an American tandem two-seat, twin-engine, all-weather, long-range supersonic jet interceptor and fighter-bomber originally developed by McDonnell Aircraft for the United States Navy.Swanborough and Bow ...

fighter weapons systems. In 1962, he set two world time-to-climb records in the F-4, reaching in 34.52 seconds and in 227.6 seconds. In 1962, Young was assigned to fly with Fighter Squadron 143 (VF-143) until his selection as an astronaut in September 1962.

Young retired from the Navy as a captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

in September 1976. He had 24 years of service.

NASA career

In September 1962, Young was selected to join NASA Astronaut Group 2. Young and his family moved to Houston, Texas, and he began his astronaut flying, physical, and academic training. After he completed his initial training, Young was assigned to work on the environmental control system and survivor gear. Young's team selected the David Clark Company G3C pressure suit, and he helped develop the waste disposal and airlock development systems.Project Gemini

Gemini 3

In April 1964, Young was selected as the pilot of Gemini 3, commanded by Gus Grissom. The crew had originally been Alan Shepard and

In April 1964, Young was selected as the pilot of Gemini 3, commanded by Gus Grissom. The crew had originally been Alan Shepard and Thomas P. Stafford

Thomas Patten Stafford (born September 17, 1930) is an American former Air Force officer, test pilot, and NASA astronaut, and one of 24 people who flew to the Moon. He also served as Chief of the Astronaut Office from 1969 to 1971.

After grad ...

, but they were replaced after Shepard was diagnosed with Ménière's disease. The Gemini 3 backup commander was Wally Schirra, with Stafford as the backup pilot. The primary mission of Gemini 3 was to test the ability of the spacecraft to perform orbital maneuver

In spaceflight, an orbital maneuver (otherwise known as a burn) is the use of propulsion systems to change the orbit of a spacecraft.

For spacecraft far from Earth (for example those in orbits around the Sun) an orbital maneuver is called a ' ...

s throughout the flight. Biological experiments were assigned to test the effects of radiation

In physics, radiation is the emission or transmission of energy in the form of waves or particles through space or through a material medium. This includes:

* ''electromagnetic radiation'', such as radio waves, microwaves, infrared, visi ...

on human blood

Blood is a body fluid in the circulatory system of humans and other vertebrates that delivers necessary substances such as nutrients and oxygen to the cells, and transports metabolic waste products away from those same cells. Blood in the c ...

and microgravity

The term micro-g environment (also μg, often referred to by the term microgravity) is more or less synonymous with the terms ''weightlessness'' and ''zero-g'', but emphasising that g-forces are never exactly zero—just very small (on the I ...

on cell division, and an experiment to test reentry communications was created. Both crews initially trained in simulators at the McDonnell Aircraft Corporation facilities in St. Louis, Missouri, and moved their training when the simulators were set up at the Manned Spacecraft Center and Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in October 1964. Both primary and backup crews participated in Gemini 3's capsule system tests before it left the McDonnell facility. The capsule was brought to the Kennedy Space Center on January 4, 1965, and both crews trained in it from February 14 to March 18. Young advocated for a longer mission than the planned three orbits, but his suggestion was rejected.

On March 23, 1965, Young and Grissom entered their capsule at 7:30 a.m. They conducted their preflight system checkout ahead of schedule but had to delay the launch after there was a leak in an oxidizer line in the Titan II GLV. Gemini 3 launched at 9:24 a.m. from LC-19

Launch Complex 19 (LC-19) is a deactivated launch site on Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Florida used by NASA to launch all of the Gemini crewed spaceflights. It was also used by uncrewed Titan I and Titan II missiles.

LC-19 was in ...

and entered in a elliptical orbit. Twenty minutes into flight, Young recognized multiple anomalous system readings and determined that there might be issues with the instrument power supply. He switched from the primary power supply to the backup, which solved the issue. Young successfully completed the radiation experiment on human blood, but Grissom accidentally broke a handle and was unable to complete his assigned experiment on cell division. Gemini 3 successfully conducted its orbital maneuver tests that allowed it to circularize its orbit, change its orbital plane, and lower its perigee to . On the third orbit, Young fired the retrorockets to begin re-entry. The lift the capsule experienced during reentry was less than predicted, and Gemini 3 landed short of its target area. After the parachutes deployed, the crew shifted the capsule to its landing orientation, which caused both of them to be thrown forward into the windshield and damaged the faceplates on their helmets. The crew remained inside the capsule for 30 minutes as they waited for a helicopter to retrieve them, and they and the capsule were successfully recovered aboard . After the flight, it was discovered that Young had smuggled a corned beef sandwich aboard, which he and Grissom shared while testing food. The House Committee on Appropriations launched a hearing regarding the incident, and some members argued that the two astronauts had disrupted the scheduled food test.

Gemini 10

After Gemini 3, Grissom and Young were assigned as backup commander and pilot for

After Gemini 3, Grissom and Young were assigned as backup commander and pilot for Gemini 6

Gemini 6A (officially Gemini VI-A) With Gemini IV, NASA changed to Roman numerals for Gemini mission designations. was a 1965 crewed United States spaceflight in NASA's Gemini program.

The mission, flown by Wally Schirra and Thomas P. Stafford, ...

. On January 24, 1966, Young and Michael Collins were assigned as the Gemini 10 commander and pilot, with Alan L. Bean and Clifton C. Williams Jr. as the backup crew. The primary mission of Gemini 10 was to dock with an Agena target vehicle (ATV) and use its engines to maneuver. Using the Agena engines to maneuver had been a failed objective of Gemini 8 and Gemini 9

Gemini 9A (officially Gemini IX-A) With Gemini IV, NASA changed to Roman numerals for Gemini mission designations. was a 1966 crewed spaceflight in NASA's Gemini program. It was the seventh crewed Gemini flight, the 13th crewed American flight ...

. The mission planned for Gemini 10 to dock with its assigned Agena target vehicle and then maneuver to rendezvous with the already orbiting Agena that had been previously assigned to Gemini 8. In the event of a failure of Gemini 10's target vehicle, the mission would still launch and attempt a rendezvous with Gemini 8's target vehicle.

The Agena target vehicle was launched on July 18, 1966, at 3:39 p.m. and successfully entered orbit. Gemini 10 launched as scheduled later that day at 5:20 p.m. from LC-19, within the 35-second launch window that maximized its chances of making the dual rendezvous. Once in orbit, the crew attempted to navigate to their first rendezvous using celestial navigation

Celestial navigation, also known as astronavigation, is the practice of position fixing using stars and other celestial bodies that enables a navigator to accurately determine their actual current physical position in space (or on the surface of ...

, but were unable to navigate and required inputs from Mission Control. Young maneuvered to a orbit to prepare for the rendezvous, and he had to make two midcourse corrections due to misalignment during the maneuver burns. Gemini 10 successfully rendezvoused and docked with the Agena target vehicle at 11:12 p.m. The higher-than-expected fuel consumption during the midcourse corrections caused flight director

Flight controllers are personnel who aid space flight by working in such Mission Control Centers as NASA's Mission Control Center or ESA's European Space Operations Centre. Flight controllers work at computer consoles and use telemetry t ...

Glynn Lunney to cancel planned additional docking practice once the capsule had completed its rendezvous. Using the Agena's engines, Gemini 10 maneuvered to a elliptical orbit, which set a new altitude record for a crewed vehicle at the apogee. Gemini 10 used the rockets on the Agena to maneuver and rendezvous with the Gemini 8 Agena and set another new altitude record of . Young fired the Agena engines to lower the apogee to , and later circularized the orbit with another burn to raise the perigee to , which was below the Gemini8 Agena. Collins performed a standup extravehicular activity (EVA) where he stood at the door of the Gemini capsule to photograph the southern Milky Way to study its ultraviolet radiation. He began a color photography experiment but did not finish it as his and Young's eyes began filling with tears due to irritation from the anti-fog compound in their helmets.

Gemini 10 undocked from its Agena and performed two maneuvers to rendezvous with the Gemini 8 Agena. Gemini 10 successfully rendezvoused with its second target vehicle 47 hours into the mission, and Young accomplished station keeping to keep the capsule approximately from the Agena vehicle. Collins conducted an EVA to retrieve a micrometeorite experiment package. After he handed the package to Young, Collins extended his umbilical to test his maneuverability using a nitrogen gun, but struggled with it and pulled himself back to the capsule with his umbilical cable. The crew maneuvered away from the Agena and lowered their perigee to . Young conducted the retrofire burn and manually flew the reentry. The capsule landed from their recovery ship, , in the western Atlantic Ocean on July 21, 1966, at 4:07 p.m. After the crew was recovered and aboard the ship, flight controllers completed several burns on the Agena target vehicle to put it in a circular orbit

A circular orbit is an orbit with a fixed distance around the barycenter; that is, in the shape of a circle.

Listed below is a circular orbit in astrodynamics or celestial mechanics under standard assumptions. Here the centripetal force is ...

to be used as a target for future missions.

Apollo program

Apollo 10

Young was originally assigned as backup to the second crewed Apollo mission, along with Thomas P. Stafford and

Young was originally assigned as backup to the second crewed Apollo mission, along with Thomas P. Stafford and Eugene A. Cernan

Eugene Andrew Cernan (; March 14, 1934 – January 16, 2017) was an American astronaut, naval aviator, electrical engineer, aeronautical engineer, and fighter pilot. During the Apollo 17 mission, Cernan became the eleventh human bei ...

. After the delays caused by the fatal Apollo 1 fire in January 1967, Young, Cernan, and Stafford were assigned as the Apollo 7

Apollo 7 (October 1122, 1968) was the first crewed flight in NASA's Apollo program, and saw the resumption of human spaceflight by the agency after the fire that killed the three Apollo 1 astronauts during a launch rehearsal test on Ja ...

backup crew. On November 13, 1968, NASA announced that the Apollo 10 crew would be commanded by Stafford, with Young as command module pilot and Cernan as the lunar module pilot. The backup crew was L. Gordon Cooper Jr.

Leroy Gordon "Gordo" Cooper Jr. (March 6, 1927 – October 4, 2004) was an American aerospace engineer, test pilot, United States Air Force pilot, and the youngest of the seven original astronauts in Project Mercury, the first human ...

, Donn F. Eisele, and Edgar D. Mitchell

Edgar Dean Mitchell (September 17, 1930 – February 4, 2016) was a United States Navy officer and aviator, test pilot, aeronautical engineer, ufologist, and NASA astronaut. As the Lunar Module Pilot of Apollo 14 in 1971 he spent nine hour ...

. Apollo 10 would be the only F-type mission, which entailed crewed entry into lunar orbit

In astronomy, lunar orbit (also known as a selenocentric orbit) is the orbit of an object around the Moon.

As used in the space program, this refers not to the orbit of the Moon about the Earth, but to orbits by spacecraft around the Moon. The ...

and testing of the lunar module, but without a landing. It would serve as a final test for the procedures and hardware before the first lunar landing. During flight preparation, the crew spent over 300 hours in simulators, both at the Manned Spacecraft Center and at Cape Kennedy. Mission Control linked with Young in the command module simulator and Stafford and Cernan in the lunar module simulator to provide realistic training. The crew selected the call sign '' Charlie Brown'' for the command module and '' Snoopy'' for the lunar module, in reference to the '' Peanuts'' comic strip by Charles M. Schulz.

On May 18, 1969, Apollo 10 launched at 11:49 a.m. After the trans-lunar injection

A trans-lunar injection (TLI) is a propulsive maneuver used to set a spacecraft on a trajectory that will cause it to arrive at the Moon.

History

The first space probe to attempt TLI was the Soviet Union's Luna 1 on January 2, 1959 which wa ...

(TLI) burn, Young successfully docked the command module with the lunar module. Young took celestial navigation measurements while en route to the Moon as a contingency for a loss of communication. Apollo 10 completed one midcourse correction, and Young performed the retrograde maneuver to bring the spacecraft into orbit above the lunar surface. On May 22, Stafford and Cernan entered the lunar module but were concerned that the docking ports' alignment had slipped by 3.5°. Apollo Program Spacecraft manager George M. Low determined that it was within acceptable limits, and the two spacecraft undocked. Young examined the lunar module after the two spacecraft were separated by and then maneuvered the command module away. Stafford and Cernan began their descent and flew the lunar module down to above the lunar surface. The lunar module crew tested the abort guidance system but had accidentally changed its setting from "attitude hold" to "automatic". As they prepared for the ascent, the lunar module began maneuvering as its automatic setting caused it to search for the command module. Stafford regained control of the spacecraft and flew the ascent towards the meeting with the command module. Young flew alone in the command module and prepared to maneuver to the lunar module in the event that its ascent engine did not work. Once the lunar module rendezvoused with the command module, Young successfully docked the two spacecraft. The crew transferred to the command module and undocked from the lunar module, which was flown by Mission Control into a solar orbit. While still in lunar orbit, Young tracked landmarks in preparation for a lunar landing, then flew the trans-Earth injection (TEI) maneuver. On May 26, Apollo 10 reentered the Earth's atmosphere and safely landed from Samoa. It landed from its recovery ship, the , and the crew was recovered by helicopter.

Apollo 16

Young was assigned the backup commander of

Young was assigned the backup commander of Apollo 13

Apollo 13 (April 1117, 1970) was the seventh crewed mission in the Apollo space program and the third meant to land on the Moon. The craft was launched from Kennedy Space Center on April 11, 1970, but the lunar landing was aborted aft ...

, along with Charles Duke and Jack Swigert

John Leonard Swigert Jr. (August 30, 1931 – December 27, 1982) was an American NASA astronaut, test pilot, mechanical engineer, aerospace engineer, United States Air Force pilot, and politician. In April 1970, as command module pilot of Apollo ...

. Duke exposed both the primary and backup crews to the German measles, causing the replacement of Ken Mattingly, who was not immune to German measles, by Swigert as the command module pilot two days prior to the launch.

On March 3, 1971, Young was assigned as the commander of Apollo 16

Apollo 16 (April 1627, 1972) was the tenth crewed mission in the United States Apollo space program, administered by NASA, and the fifth and penultimate to land on the Moon. It was the second of Apollo's " J missions", with an extended sta ...

, along with Duke and Mattingly. Their backup crew was Fred Haise, Stuart Roosa, and Edgar D. Mitchell

Edgar Dean Mitchell (September 17, 1930 – February 4, 2016) was a United States Navy officer and aviator, test pilot, aeronautical engineer, ufologist, and NASA astronaut. As the Lunar Module Pilot of Apollo 14 in 1971 he spent nine hour ...

. The mission's science objective was to study material from the lunar highlands, as they were believed to contain volcanic material older than the lunar mare that had been the sites of the previous Apollo landings. The Apollo Site Selection Board considered landing sites at Alphonsus crater

Alphonsus is an ancient impact crater on the Moon that dates from the pre-Nectarian era. It is located on the lunar highlands on the eastern end of Mare Nubium, west of the Imbrian Highlands, and slightly overlaps the crater Ptolemaeus to the nor ...

and the Descartes Highlands

The Descartes Highlands is an area of lunar highlands located on the near side that served as the landing site of the American Apollo 16 mission in early 1972. The Descartes Highlands is located in the area surrounding Descartes crater, after whi ...

, and it chose the Descartes Highlands as the Apollo 16 landing site on June 3. The mission science kit contained instruments to sample and photograph the lunar surface, as well as a magnetometer

A magnetometer is a device that measures magnetic field or magnetic dipole moment. Different types of magnetometers measure the direction, strength, or relative change of a magnetic field at a particular location. A compass is one such device, o ...

and a seismometer. Additionally, the crew brought an ultraviolet camera and spectrograph

An optical spectrometer (spectrophotometer, spectrograph or spectroscope) is an instrument used to measure properties of light over a specific portion of the electromagnetic spectrum, typically used in spectroscopic analysis to identify mate ...

to study interplanetary and hydrogen. To prepare for their EVAs, Young and Duke participated in field exercises in geological research. They conducted field work at the Mono craters

Mono may refer to:

Common meanings

* Infectious mononucleosis, "the kissing disease"

* Monaural, monophonic sound reproduction, often shortened to mono

* Mono-, a numerical prefix representing anything single

Music Performers

* Mono (Japanese b ...

in California to learn how to identify lava dome

In volcanology, a lava dome is a circular mound-shaped protrusion resulting from the slow extrusion of viscous lava from a volcano. Dome-building eruptions are common, particularly in convergent plate boundary settings. Around 6% of eruptions on ...

s and tuff and the Sudbury Basin

The Sudbury Basin (), also known as Sudbury Structure or the Sudbury Nickel Irruptive, is a major geological structure in Ontario, Canada. It is the third-largest known impact crater or astrobleme on Earth, as well as one of the oldest. The cra ...

to study breccia.

Apollo 16 successfully launched at 12:54 p.m. on April 16, 1972. After the spacecraft reached Earth orbit, several problems developed with the S-IVB attitude control system, but Apollo 16 was still able to perform its trans-lunar injection burn. Mattingly docked the command module with the lunar module, and the crew decided to perform an early checkout of the lunar module over concerns that it had been damaged but found no issues. Apollo 16 flew behind the Moon 74 hours into the mission and entered into a elliptical orbit. The next day, Duke and Young entered the lunar module and undocked, but Mattingly soon reported an issue with the thrust vector controls on the service propulsion system, which would have prevented the command module from maneuvering in case the lunar module was unable to complete its rendezvous. After a delay, Mission Control approved the landing, and Young and Duke began their descent 5 hours and 42 minutes later than scheduled. As the lunar module descended, its projected landing location was north and west of its target location. Young took corrective action to adjust their landing location, and the lunar module landed north and west of its target location.

On April 21 Young and Duke began their first EVA. Young was the first to exit the lunar module, and his first words on the lunar surface were "I'm glad they got ol' Brer Rabbit here, back in the briar patch where he belongs". The two astronauts set up the lunar rover, and deployed the Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package

The Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package (ALSEP) comprised a set of scientific instruments placed by the astronauts at the landing site of each of the five Apollo missions to land on the Moon following Apollo 11 (Apollos 12, 14, 15, 16, ...

(ALSEP). Mission Control informed Young that the U.S. House of Representatives had passed that year's space budget, which included funding to begin the Space Shuttle program. Young tripped over the cables to the heat flow sensors, which irreparably broke the sensors' communication link with Earth. The two astronauts conducted a seismic experiment using pneumatic hammers and began a traverse to Flag crater, which was west of the landing site. They set up a geology station at the crater, and collected Big Muley, a breccia that was the largest lunar rock collected during the Apollo program. Young and Duke traveled back towards the lunar module, stopping at Spook and Buster craters along the way. Before ending the EVA, they tested the maneuverability of the lunar rover. They finished the EVA after seven hours on the lunar surface.

Young and Duke conducted their second EVA on April 22. They traveled to Cinco crater to sample at three geology sites, with the goal of finding ejecta

Ejecta (from the Latin: "things thrown out", singular ejectum) are particles ejected from an area. In volcanology, in particular, the term refers to particles including pyroclastic materials (tephra) that came out of a volcanic explosion and magma ...

from the South Ray crater. After they traveled to collect samples at the nearby Wreck crater, the rover's navigation system failed, forcing the two astronauts to manually navigate back to the lunar module. On their return trip, they stopped at the Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package to take soil samples. They returned to the lunar module and finished their EVA after seven hours on the lunar surface. The third EVA began on the morning of April 23. The two astronauts drove to North Ray crater and collected rock samples from its rim. They collected further samples from outside the crater to allow scientists to recreate the crater's stratigraphy

Stratigraphy is a branch of geology concerned with the study of rock (geology), rock layers (Stratum, strata) and layering (stratification). It is primarily used in the study of sedimentary rock, sedimentary and layered volcanic rocks.

Stratigrap ...

using its ejecta. They returned to the lunar module and parked the rover to allow its cameras to broadcast their ascent. They ended their EVA after five hours; it was shorter than the previous two because of the delayed landing on the lunar surface.

On April 24, the lunar module successfully ascended into lunar orbit and docked with the command module. The astronauts transferred the of lunar samples that they collected and jettisoned the lunar module. The command module completed its trans-Earth injection burn and began its flight back to Earth, during which time Mattingly performed an EVA to recover film from the exterior cameras and conduct an experiment on microbe

A microorganism, or microbe,, ''mikros'', "small") and ''organism'' from the el, ὀργανισμός, ''organismós'', "organism"). It is usually written as a single word but is sometimes hyphenated (''micro-organism''), especially in olde ...

exposure to ultraviolet sunlight. The command module (CM) reentered the atmosphere on April 27 and landed in the ocean approximately southeast of Christmas Island, and the crew was recovered aboard the . After the mission, Young was assigned as the Apollo 17

Apollo 17 (December 7–19, 1972) was the final mission of NASA's Apollo program, the most recent time humans have set foot on the Moon or traveled beyond low Earth orbit. Commander Gene Cernan and Lunar Module Pilot Harrison Schmitt walked on ...

backup commander, along with Duke as the backup lunar module pilot and Stuart A. Roosa as the backup command module pilot. The backup crew was originally the Apollo 15

Apollo 15 (July 26August 7, 1971) was the ninth crewed mission in the United States' Apollo program and the fourth to Moon landing, land on the Moon. It was the first List of Apollo missions#Alphabetical mission types, J mission, with a ...

crew, but were removed after NASA management learned of their plan to sell the unauthorized postal covers they took to the lunar surface.

Space Shuttle program

In January 1973, Young was made Chief of the Space Shuttle Branch of the Astronaut Office. At the time, the overall Space Shuttle specifications and manufacturers had been determined, and Young's role was to serve as a liaison for the astronauts to provide design input. Young's office recommended changes for the orbiter's RCS thrusters, star tracker, and thermal radiators. In January 1974, he became Chief of the Astronaut Office after the departure of Alan B. Shepard Jr. One of his first roles after taking over the office was overseeing the end of the Skylab program and the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project (ASTP) mission, but the remainder of the spaceflights during his tenure were Space Shuttle missions. Young flew in the T-38 Talon chase planes for several of the Approach and Landing Tests (ALT) of the .STS-1

In March 1978, Young was selected by George W. S. Abbey, then deputy director of the

In March 1978, Young was selected by George W. S. Abbey, then deputy director of the Johnson Space Center

The Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center (JSC) is NASA's center for human spaceflight (originally named the Manned Spacecraft Center), where human spaceflight training, research, and flight control are conducted. It was renamed in honor of the late U ...

(JSC), to be the commander of STS-1, with Robert L. Crippen

Robert Laurel Crippen (born September 11, 1937) is an American retired naval officer and aviator, test pilot, aerospace engineer, and retired astronaut. He traveled into space four times: as Pilot of STS-1 in April 1981, the first Space Shuttl ...

flying as the pilot. Their backup crew, Joe H. Engle and Richard H. Truly, was the primary crew for STS-2. The development of ''Columbia'' was delayed because of the longer-than-predicted installation time of the Space Shuttle thermal protection system. Young and Crippen trained to be able to repair thermal tiles in-orbit, but determined that they would be unable to repair the tiles during a spacewalk

Extravehicular activity (EVA) is any activity done by an astronaut in outer space outside a spacecraft. In the absence of a breathable atmosphere of Earth, Earthlike atmosphere, the astronaut is completely reliant on a space suit for environmen ...

.

The first launch attempt for STS-1 to launch was on April 10, 1981, but the launch was postponed at T–18 minutes due to a computer error. STS-1 launched at 7:00 a.m. on April 12 from LC-39A at the Kennedy Space Center. The first stage of the launch flew higher than anticipated, and the solid rocket boosters separated approximately higher than the original plan. The rest of the launch went as expected, and STS-1 successfully entered Earth orbit. Vice President George H. W. Bush

George Herbert Walker BushSince around 2000, he has been usually called George H. W. Bush, Bush Senior, Bush 41 or Bush the Elder to distinguish him from his eldest son, George W. Bush, who served as the 43rd president from 2001 to 2009; pr ...

called the crew during their first full day in orbit to congratulate them on their successful mission. The crew inspected their thermal tiles and determined that some had been lost during launch. Amid concerns that the underside of ''Columbia'' might have also lost some thermal shielding, a KH-11 KENNEN satellite was used to image the orbiter and it was determined that the orbiter could safely reenter the atmosphere. Young and Crippen tested the orbital maneuvering capabilities of the orbiter, as well as its mechanical and computer systems. STS-1 reentered the atmosphere and landed on April 14 at Edwards Air Force Base

Edwards Air Force Base (AFB) is a United States Air Force installation in California. Most of the base sits in Kern County, but its eastern end is in San Bernardino County and a southern arm is in Los Angeles County. The hub of the base is E ...

, California.

STS-9

As the chief of the Astronaut Office, Young recommended the crews that flew on the subsequent test and operational Space Shuttle missions. Young would routinely sit in the simulators alongside the crews to determine their effectiveness, and he flew the Shuttle Training Aircraft (STA) to test landing approaches prior to the orbiter landing.

In 1983, Young flew as the commander of

As the chief of the Astronaut Office, Young recommended the crews that flew on the subsequent test and operational Space Shuttle missions. Young would routinely sit in the simulators alongside the crews to determine their effectiveness, and he flew the Shuttle Training Aircraft (STA) to test landing approaches prior to the orbiter landing.

In 1983, Young flew as the commander of STS-9

STS-9 (also referred to Spacelab 1) was the ninth NASA Space Shuttle mission and the sixth mission of the Space Shuttle ''Columbia''. Launched on 28 November 1983, the ten-day mission carried the first Spacelab laboratory module into orbit.

...

aboard . His pilot was Brewster H. Shaw

Brewster Hopkinson Shaw Jr. (born May 16, 1945) is a retired NASA astronaut, U.S. Air Force colonel, and former executive at Boeing. Shaw was inducted into the U.S. Astronaut Hall of Fame on May 6, 2006.

Shaw is a veteran of three Space Shuttle ...

, his two mission specialists were Owen K.Garriott and Robert A. Parker

Robert Allan Ridley Parker (born December 14, 1936) is an American physicist and astronomer, former Director of the NASA Management Office at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and a retired NASA astronaut. He was a Mission Specialist on two Space ...

, and his two payload specialists were Byron K. Lichtenberg

Byron Kurt Lichtenberg, Sc. D. (born February 19, 1948) is an American engineer and fighter pilot who flew aboard two NASA Space Shuttle missions as a Payload Specialist. In 1983, he and Ulf Merbold became the first Payload Specialists to fly o ...

and West German astronaut Ulf Merbold. The mission was initially scheduled to launch on October 29, but was delayed by a problem with the right solid rocket booster. The flight launched from LC-39A at 11:00 a.m. on November 28. It carried the first Spacelab module into orbit, and the crew had to conduct a shift-based schedule to maximize on-orbit research in astronomy, atmospheric and space physics, and life sciences

This list of life sciences comprises the branches of science that involve the scientific study of life – such as microorganisms, plants, and animals including human beings. This science is one of the two major branches of natural science, the ...

. Young tested a new portable onboard computer, and attempted to photograph Russian airfields as ''Columbia'' orbited overhead. Prior to reentry, two of ''Columbias four primary General Purpose Computers (GPC) failed, which caused a delay in landing as they had to reset them and load the Entry Options Control Mode into an alternate GPC. After the GPC was repaired, ''Columbia'' successfully reentered the atmosphere and landed at Edwards Air Force Base on December 8.

NASA management

Young remained as the chief of the Astronaut Office after STS-9. He was critical of NASA management following the Space Shuttle ''Challenger'' disaster and blamed the disaster on the lack of safety culture within the Space Shuttle program. Young testified before the Rogers Commission, and suggested improvements for the safety program at NASA. Young had been scheduled to fly as the commander of STS-61-J to deploy the Hubble Space Telescope, but the mission was canceled as a result of the ''Challenger'' disaster. In May 1987, Young was replaced as the chief of the Astronaut Office by Daniel C. Brandenstein and was reassigned as Special Assistant to Johnson Space Center Director Aaron Cohen for Engineering, Operations and Safety. Young believed that his reassignment was the result of his public criticism of NASA management. He oversaw the redesign of the solid rocket boosters to prevent a repeat of the ''Challenger'' disaster and advocated for the strengthening of the thermal protection tiles at the chin-section of the orbiters. He continued to work on safety improvements in the Space Shuttle program, including improving the landing surfaces, installation of emergency drag parachutes, the inclusion of theGlobal Positioning System

The Global Positioning System (GPS), originally Navstar GPS, is a satellite-based radionavigation system owned by the United States government and operated by the United States Space Force. It is one of the global navigation satellite sy ...

(GPS) into the Space Shuttle's navigation system, and improving landing simulations. In February 1996, he was assigned as the Associate Director (Technical) of Johnson Space Center, where he was involved in the development of the Shuttle–Mir program and the design process for the International Space Station (ISS).

After working at NASA for over 42 years Young retired on December 31, 2004. During his career, he flew for more than 15,275 hours, including more than 9,200 hours in T-38s and 835 hours in spacecraft during six space flights. Additionally, he spent over 15,000 hours in training to prepare for eleven primary and backup crew positions.

Retirement

Following his retirement, Young worked as a public speaker, and advocated for the importance of asteroid impact avoidance, colonization of the Moon, and climate engineering. In April 2006, Young and Crippen appeared at the 25th anniversary of the STS-1 launch at the Kennedy Space Center and spoke of their experiences during the flight. In November 2011, Young and Crippen met with the crew of STS-135, the last Space Shuttle mission.

In 2012, Young and

Following his retirement, Young worked as a public speaker, and advocated for the importance of asteroid impact avoidance, colonization of the Moon, and climate engineering. In April 2006, Young and Crippen appeared at the 25th anniversary of the STS-1 launch at the Kennedy Space Center and spoke of their experiences during the flight. In November 2011, Young and Crippen met with the crew of STS-135, the last Space Shuttle mission.

In 2012, Young and James R. Hansen

James R. Hansen (born 1952) is a professor of history at Auburn University in Alabama. His book ''From the Ground Up'' won the History Book Award of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics in 1988. For his work, ''The Wind and Bey ...

co-authored his autobiography, ''Forever Young''.

Personal life

On December 1, 1955, Young married Barbara White of Savannah, Georgia, at St. Mark's Episcopal Church in Palatka, Florida. Together they had two children, Sandra and John, and two grandchildren. They were divorced in the summer of 1971. Later that year, he married Susy Feldman, and they lived in Houston. Young was friends withGeorge H. W. Bush

George Herbert Walker BushSince around 2000, he has been usually called George H. W. Bush, Bush Senior, Bush 41 or Bush the Elder to distinguish him from his eldest son, George W. Bush, who served as the 43rd president from 2001 to 2009; pr ...

and Barbara Bush, and he vacationed at the Bush compound in Kennebunkport, Maine.

Young died on January 5, 2018, at his home in Houston, of complications from pneumonia, at the age of 87. He was interred at Arlington National Cemetery on April 30, 2019.

Awards and honors

While he served in the Navy, Young was awarded the Navy Astronaut Wings,Navy Distinguished Service Medal

The Navy Distinguished Service Medal is a military decoration of the United States Navy and United States Marine Corps which was first created in 1919 and is presented to sailors and Marines to recognize distinguished and exceptionally meritoriou ...

with a 5/16 inch star

A inch star (9.7mm) is a miniature gold or silver five-pointed star that is authorized by the United States Armed Forces as a ribbon device to denote subsequent awards for specific decorations of the Department of the Navy, Coast Guard, Public Hea ...

, and the Distinguished Flying Cross with two stars. During both his military and civilian career with NASA, he received the NASA Distinguished Service Medal

The NASA Distinguished Service Medal is the highest award that can be bestowed by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration of the United States. The medal may be presented to any member of the federal government, including both milita ...

(1969) with three oak leaf clusters, the NASA Exceptional Service Medal, the Congressional Space Medal of Honor, the NASA Space Flight Medal, the NASA Exceptional Engineering Achievement Medal, the NASA Outstanding Leadership Medal, and the NASA Exceptional Achievement Medal.

In 1981, NASA and the developers of the Space Shuttle won the Collier Trophy

The Robert J. Collier Trophy is an annual aviation award administered by the U.S. National Aeronautic Association (NAA), presented to those who have made "the greatest achievement in aeronautics or astronautics in America, with respect to im ...

, and the crews of STS-1 and STS-2 received special recognition. Young was inducted into the International Space Hall of Fame

The New Mexico Museum of Space History is a museum and planetarium complex in Alamogordo, New Mexico dedicated to artifacts and displays related to space flight and the Space Age. It includes the International Space Hall of Fame. The Museum of S ...

in 1982, along with nine other Gemini astronauts. Young, along with the other Gemini astronauts, was inducted into the second U.S. Astronaut Hall of Fame

The United States Astronaut Hall of Fame, located inside the Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex Heroes & Legends building on Merritt Island, Florida, honors American astronauts and features the world's largest collection of their personal memora ...

class in 1993. In 1995, he was inducted into the International Air & Space Hall of Fame at the San Diego Air & Space Museum. In 2001, Young was inducted into the Georgia Aviation Hall of Fame.

Young was awarded the Golden Plate Award

The American Academy of Achievement, colloquially known as the Academy of Achievement, is a non-profit educational organization that recognizes some of the highest achieving individuals in diverse fields and gives them the opportunity to meet o ...

of the American Academy of Achievement in 1993. In 2010, he was awarded the General James E. Hill Lifetime Space Achievement Award He received the Exceptional Engineering Achievement Award in 1985, and the American Astronautical Society Space Flight Award in 1993. In 1998, he received the Philip J. Klass Award for Lifetime Achievement. He was a fellow of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA), the American Astronautical Society (AAS), and the Society of Experimental Test Pilots.

Florida State Road 423, a highway in Orlando and Kissimmee, Florida, is named John Young Parkway. John Young Elementary School, a school in the Orange County Public Schools, was named after him. The planetarium at the Orlando Science Center was named in his honor.

Northrop Grumman announced in 2018 that the Cygnus spacecraft for Cygnus NG-10

NG-10,Overview - CRS-10 mission

Northrop Gru ...

, their tenth cargo resupply mission to the International Space Station, would be named ''S.S. John Young''. Cygnus NG-10 successfully launched on November 17, 2018, and concluded its mission on February 25, 2019.

Asteroid Northrop Gru ...

5362 Johnyoung

__NOTOC__

Year 536 (Roman numerals: DXXXVI) was a leap year starting on Tuesday of the Julian calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year after the Consulship of Belisarius. The denomination 536 for this year has been used since the early m ...

was named after Young.

See also

* List of spaceflight recordsReferences

External links

Interview with John W. Young

for the ''

NOVA

A nova (plural novae or novas) is a transient astronomical event that causes the sudden appearance of a bright, apparently "new" star (hence the name "nova", which is Latin for "new") that slowly fades over weeks or months. Causes of the dramati ...

'' episode "To the Moon"; WGBH Educational Foundation, raw footage, 1998

*

*

{{DEFAULTSORT:Young, John

1930 births

1965 in spaceflight

1966 in spaceflight

1969 in spaceflight

1972 in spaceflight

1981 in spaceflight

1983 in spaceflight

2018 deaths

American aerospace engineers

American autobiographers

American test pilots

Apollo 10

Apollo 16

Apollo program astronauts

Articles containing video clips

Aviators from California

Aviators from Florida

Aviators from Georgia (U.S. state)

Burials at Arlington National Cemetery

Deaths from pneumonia in Texas

Georgia Tech alumni

Military personnel from California

Military personnel from Florida

Military personnel from Georgia (U.S. state)

NASA Astronaut Group 2

NASA civilian astronauts

NASA people

National Aviation Hall of Fame inductees

People from Orlando, Florida

People from San Francisco

People who have walked on the Moon

Project Gemini astronauts

Recipients of the Congressional Space Medal of Honor

Recipients of the Distinguished Flying Cross (United States)

Recipients of the NASA Distinguished Service Medal

Recipients of the NASA Exceptional Achievement Medal

Recipients of the NASA Exceptional Service Medal

Recipients of the Navy Distinguished Service Medal

Space Shuttle program astronauts

United States Astronaut Hall of Fame inductees

United States Naval Aviators

United States Naval Test Pilot School alumni

United States Navy astronauts

United States Navy officers

United States Navy personnel of the Korean War

Writers from San Francisco