John Maynard (1604–1690) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir John Maynard KS (1604 – 9 October 1690) was an English lawyer and politician, prominent under the reigns of Charles I, the

Sir John Maynard KS (1604 – 9 October 1690) was an English lawyer and politician, prominent under the reigns of Charles I, the

url

Date accessed: 22 June 2008.

Maynard amassed a large fortune, bought the manor of

Maynard amassed a large fortune, bought the manor of

/ref> and at

History of Parliament Online – John Maynard

*Bramston, Sir John. (Baron Richard Griffin Braybrooke editor), ''The autobiography of Sir John Bramston: K.B., of Skreens, in the hundred of Chelmsford; now first printed from the original ms. in the possession of his lineal descendant Thomas William Bramston, Esq.'', Camden society. Publications, no. xxxii, Printed for the Camden society, by J. B. Nichols and son, 1845 *Lewis, Samuel (1831). ''A Topographical Dictionary of England Comprising the Several Counties, Cities, Boroughs, Corporate & Market Towns ...& the Islands of Guernsey, Jersey, and Man, with Historical and Statistical Descriptions; Illustrated by Maps of the Different Counties & Islands; ... and a Plan of London and Its Environs]'' *Rigg, James McMullen ;Attribution , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Maynard, John 1604 births 1690 deaths Politicians from Tavistock Alumni of Exeter College, Oxford Members of the Middle Temple Serjeants-at-law (England) English Presbyterians of the Interregnum (England) Knights Bachelor Founders of English schools and colleges Lay members of the Westminster Assembly English lawyers 17th-century English lawyers Members of the Parliament of England (pre-1707) for Totnes Members of the Parliament of England (pre-1707) for Exeter Members of the Parliament of England for Plymouth Members of the Parliament of England for Newtown Members of the Parliament of England for Bere Alston Members of the Parliament of England for Camelford English MPs 1640 (April) English MPs 1640–1648 English MPs 1656–1658 English MPs 1659 English MPs 1660 English MPs 1661–1679 English MPs 1679 English MPs 1680–1681 English MPs 1681 English MPs 1685–1687 English MPs 1689–1690 English MPs 1690–1695 17th-century philanthropists

Sir John Maynard KS (1604 – 9 October 1690) was an English lawyer and politician, prominent under the reigns of Charles I, the

Sir John Maynard KS (1604 – 9 October 1690) was an English lawyer and politician, prominent under the reigns of Charles I, the Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the 15th century. Originally a phrase (the common-wealth ...

, Charles II, James II and William III.Rigg, James McMullen

Origins and education

Maynard was born in 1604 at the Abbey House, Tavistock, in Devon, the eldest son and heir of Alexander Maynard ofTavistock

Tavistock ( ) is an ancient stannary and market town and civil parish in the West Devon district, in the county of Devon, England. It is situated on the River Tavy, from which its name derives. At the 2011 census, the three electoral wards (N ...

(4th son of John Maynard of Sherford in the parish of Brixton

Brixton is an area of South London, part of the London Borough of Lambeth, England. The area is identified in the London Plan as one of 35 major centres in Greater London. Brixton experienced a rapid rise in population during the 19th century ...

in Devon Vivian, Lt.Col. J.L., (Ed.) The Visitations of the County of Devon: Comprising the Heralds' Visitations of 1531, 1564 & 1620, Exeter, 1895, p.561, pedigree of Maynard), a barrister

A barrister is a type of lawyer in common law jurisdiction (area), jurisdictions. Barristers mostly specialise in courtroom advocacy and litigation. Their tasks include arguing cases in courts and tribunals, drafting legal pleadings, jurisprud ...

of the Middle Temple

The Honourable Society of the Middle Temple, commonly known simply as Middle Temple, is one of the four Inns of Court entitled to Call to the bar, call their members to the English Bar as barristers, the others being the Inner Temple (with whi ...

, by his wife Honora Arscott, daughter of Arthur Arscott of Tetcott in Devon

Devon ( ; historically also known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by the Bristol Channel to the north, Somerset and Dorset to the east, the English Channel to the south, and Cornwall to the west ...

. The senior line of the Maynard family was seated at Sherford in the parish of Brixton

Brixton is an area of South London, part of the London Borough of Lambeth, England. The area is identified in the London Plan as one of 35 major centres in Greater London. Brixton experienced a rapid rise in population during the 19th century ...

in Devon. His name appears in the matriculation

Matriculation is the formal process of entering a university, or of becoming eligible to enter by fulfilling certain academic requirements such as a matriculation examination.

Australia

In Australia, the term ''matriculation'' is seldom used no ...

register of Exeter College, Oxford

Exeter College (in full: The Rector and Scholars of Exeter College in the University of Oxford) is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England, and the fourth-oldest college of the university.

The college was founde ...

, under date 26 April 1621, which clashes unaccountably with the date of his admission to the degree of BA on 25 April 1621, given in the ''University Register of Degrees''.

Barrister

In 1619 he entered theMiddle Temple

The Honourable Society of the Middle Temple, commonly known simply as Middle Temple, is one of the four Inns of Court entitled to Call to the bar, call their members to the English Bar as barristers, the others being the Inner Temple (with whi ...

; he was called to the Bar

The call to the bar is a legal term of art in most common law jurisdictions where persons must be qualified to be allowed to argue in court on behalf of another party and are then said to have been "called to the bar" or to have received "call to ...

in November 1626, and was elected a bencher

A bencher or Master of the Bench is a senior member of an Inn of Court in England and Wales or the Inns of Court in Northern Ireland, or the Honorable Society of King's Inns in Ireland. Benchers hold office for life once elected. A bencher c ...

in 1648. A pupil of William Noy, afterwards attorney-general

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general (: attorneys general) or attorney-general (AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have executive responsibility for law enf ...

, a Devonian, and born in the law, he rapidly acquired a large practice, both on the Western circuit

Circuit courts are court systems in several common law jurisdictions. It may refer to:

* Courts that literally sit 'on circuit', i.e., judges move around a region or country to different towns or cities where they will hear cases;

* Courts that s ...

and at Westminster; he argued a reported case in the King's Bench in 1628 and was appointed Recorder of Plymouth

Plymouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Devon, South West England. It is located on Devon's south coast between the rivers River Plym, Plym and River Tamar, Tamar, about southwest of Exeter and ...

in August 1640.

Parliamentarian

He representedTotnes

Totnes ( or ) is a market town and civil parish at the head of the estuary of the River Dart in Devon, England, within the South Devon Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. It is about west of Paignton, about west-southwest of Torquay and ab ...

in both the Short Parliament

The Short Parliament was a Parliament of England that was summoned by King Charles I of England on 20 February 1640 and sat from 13 April to 5 May 1640. It was so called because of its short session of only three weeks.

After 11 years of per ...

of 1640 and the Long Parliament

The Long Parliament was an Parliament of England, English Parliament which lasted from 1640 until 1660, making it the longest-lasting Parliament in English and British history. It followed the fiasco of the Short Parliament, which had convened f ...

, and from the first took an active part in the business of the house. In December 1640 he was placed on the committee of scrutiny into the conduct of lords-lieutenant of counties, and on that for the discovery of the "prime promoters" of the new "canons ecclesiastical" passed in the recent irregular session of convocation

A convocation (from the Latin ''wikt:convocare, convocare'' meaning "to call/come together", a translation of the Ancient Greek, Greek wikt:ἐκκλησία, ἐκκλησία ''ekklēsia'') is a group of people formally assembled for a specia ...

. He was also one of the framers of the articles upon which Strafford was impeached

Impeachment is a process by which a legislative body or other legally constituted tribunal initiates charges against a public official for misconduct. It may be understood as a unique process involving both political and legal elements.

In Eu ...

, and one of the principal speakers at the trial. He threw himself with great zeal into the affair, and on the passing of the bill of attainder

A bill of attainder (also known as an act of attainder, writ of attainder, or bill of pains and penalties) is an act of a legislature declaring a person, or a group of people, guilty of some crime, and providing for a punishment, often without a ...

said joyfully to Sir John Bramston, "Now we have done our work. If we could not have effected this we could have done nothing". A strong Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Protestant tradition named for its form of church government by representative assemblies of elders, known as "presbyters". Though other Reformed churches are structurally similar, the word ''Pr ...

, he subscribed and administered to the house the protestation of 3 May 1641 in defence of the Protestant religion, and drafted the bill making subscription thereto obligatory on all subjects.

In the committee, which sat at Guildhall

A guildhall, also known as a guild hall or guild house, is a historical building originally used for tax collecting by municipalities or merchants in Europe, with many surviving today in Great Britain and the Low Countries. These buildings commo ...

after the adjournment of the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

which followed the king's attempt to arrest the five members (4 January 1641/2), he made an eloquent speech in defence of parliamentary privilege

Parliamentary privilege is a legal immunity enjoyed by members of certain legislatures, in which legislators are granted protection against civil or criminal liability for actions done or statements made in the course of their legislative duties ...

. In the following May he accepted a deputy-lieutenancy of militia under the parliament, and on 12 June 1643 was nominated a member of the Westminster Assembly of Divines. He took the covenant on 25 September following, and was one of the managers of the impeachment of William Laud

William Laud (; 7 October 1573 – 10 January 1645) was a bishop in the Church of England. Appointed Archbishop of Canterbury by Charles I of England, Charles I in 1633, Laud was a key advocate of Caroline era#Religion, Charles I's religious re ...

in January–March 1643/4. With his friend Bulstrode Whitelocke, Maynard attended, by Essex's invitation, a meeting of the anti-Cromwellian faction, held at Essex House in December 1644, to discuss the expediency of taking public action against Cromwell as an 'incendiary.' The idea, which seems to have originated with the Lord Chancellor of Scotland

The Lord Chancellor of Scotland, formally titled Lord High Chancellor, was an Officer of State in the Kingdom of Scotland. The Lord Chancellor was the principal Great Officer of State, the presiding officer of the Parliament of Scotland, the K ...

Loudon, met with no favour from the English lawyers, and was in consequence abandoned.

A curious testimony to Maynard's reputation at this time is afforded by a grant made in his favour by parliament in October 1645 of the books and manuscripts of the late Lord Chief Justice Bankes, with liberty to seize them wherever he might find them. In the House of Commons he was heard with the profoundest respect, while he advocated the abolition of feudal wardships and other salutary legal reforms. He also prospered mightily in his profession, making in the course of the summer circuit of 1647 the unprecedentedly large sum of £700. As a politician he was a strict constitutionalist, protested against the first steps taken towards the deposition of the king

King is a royal title given to a male monarch. A king is an Absolute monarchy, absolute monarch if he holds unrestricted Government, governmental power or exercises full sovereignty over a nation. Conversely, he is a Constitutional monarchy, ...

, and on the adoption of that policy withdrew from the house as no longer a lawful assembly (November 1648).

State trials under the Commonwealth

Nevertheless, on the establishment of theCommonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the 15th century. Originally a phrase (the common-wealth ...

he did not scruple to take the engagement, and held a government brief at the trial of Major Faulconer for perjury in May 1653. Assigned by order of court to advise John Lilburne

John Lilburne (c. 161429 August 1657), also known as Freeborn John, was an English political Leveller before, during and after the English Civil Wars 1642–1650. He coined the term "'' freeborn rights''", defining them as rights with which e ...

on his second trial in July 1653, Maynard at first feigned sickness. A repetition of the order, however, elicited from him some exceptions to the indictment which confounded the court and secured Lilburne's acquittal by the jury. The jury were afterwards interrogated by the council of state

A council of state is a governmental body in a country, or a subdivision of a country, with a function that varies by jurisdiction. It may be the formal name for the cabinet or it may refer to a non-executive advisory body associated with a head ...

as to the grounds of their verdict, but refused to disclose them, and Maynard thus escaped censure, and on 9 February 1653/4 was called to the degree of serjeant-at-law.

In the following year his professional duty brought him into temporary collision with the government. One Cony, a city merchant, had been arrested by order of the council of state for non-payment of taxes, and Maynard, with Serjeants Thomas Twysden and Wadham Wyndham, moved on his behalf in the upper bench for a habeas corpus

''Habeas corpus'' (; from Medieval Latin, ) is a legal procedure invoking the jurisdiction of a court to review the unlawful detention or imprisonment of an individual, and request the individual's custodian (usually a prison official) to ...

. Their argument on the return, 18 May 1655, amounted in effect to a direct attack on the government as a usurpation, and all three were forthwith, by order of Cromwell, committed to the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic citadel and castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London, England. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamle ...

; they were released on making submission (25 May).

Continuing political preferment

Maynard was among the commissioners appointed to collect the quota of the Spanish war tax of 1657 payable byDevon

Devon ( ; historically also known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by the Bristol Channel to the north, Somerset and Dorset to the east, the English Channel to the south, and Cornwall to the west ...

. Thomas Carlyle

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 17955 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian, and philosopher. Known as the "Sage writing, sage of Chelsea, London, Chelsea", his writings strongly influenced the intellectual and artistic culture of the V ...

is in error in stating that he was a member of Cromwell's House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the lower house, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England. One of the oldest ext ...

. He sat in the House of Commons for Plymouth

Plymouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Devon, South West England. It is located on Devon's south coast between the rivers River Plym, Plym and River Tamar, Tamar, about southwest of Exeter and ...

during the Second Protectorate Parliament

The Second Protectorate Parliament in England sat for two sessions from 17 September 1656 until 4 February 1658, with Thomas Widdrington as the Speaker of the House of Commons (United Kingdom), Speaker of the House of Commons. In its first sess ...

, and on the debates on the designation to be given to the 'other' house argued strongly for the revival of the old name (4 February 1657/8). Burnet states, and it is extremely probable, that he was also in favour of the revival of monarchy. On 1 May 1658 he was appointed Protector's serjeant, in which capacity he followed the Protector's bier on the ensuing 23 November. On the accession of Richard Cromwell

Richard Cromwell (4 October 162612 July 1712) was an English statesman who served as Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland from 1658 to 1659. He was the son of Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell.

Following his father ...

he was made solicitor-general

A solicitor general is a government official who serves as the chief representative of the government in courtroom proceedings. In systems based on the English common law that have an attorney general or equivalent position, the solicitor general ...

, and in parliament, where he sat for Newtown, Isle of Wight, lent the whole weight of his authority as a constitutional lawyer to prop up the Protector's tottering government.

Education

In 1658, Maynard was involved in the founding of two schools inExeter

Exeter ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and the county town of Devon in South West England. It is situated on the River Exe, approximately northeast of Plymouth and southwest of Bristol.

In Roman Britain, Exeter w ...

, The Maynard School for girls and Hele's School for boys. He was also involved with the Grammar school

A grammar school is one of several different types of school in the history of education in the United Kingdom and other English-speaking countries, originally a Latin school, school teaching Latin, but more recently an academically oriented Se ...

at Totnes

Totnes ( or ) is a market town and civil parish at the head of the estuary of the River Dart in Devon, England, within the South Devon Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. It is about west of Paignton, about west-southwest of Torquay and ab ...

which, like The Maynard, was endowed with funds under the will of Elizeeus Hele, who left considerable property for charitable purposes (Maynard was one of the trustees of his will). The will was the subject of a court case held before Sir Edward Rhodes. In this case the ''Captain Edmond Lister'' petitioned parliament on behalf of his wife Joanne. The basis of the petition was that all the money had been left to charity although at the time the will was written Joanne was not born. Rhodes found that any monies left over from the charitable purposes should be given to Joanne Lister although the chaitiable purposes should continue.'House of Commons Journal Volume 7: 6 June 1657', Journal of the House of Commons: volume 7: 1651–1660 (1802), pp. 548–549url

Date accessed: 22 June 2008.

The Restoration

On Richard's abdication and the resuscitation of theRump Parliament

The Rump Parliament describes the members of the Long Parliament who remained in session after Colonel Thomas Pride, on 6 December 1648, commanded his soldiers to Pride's Purge, purge the House of Commons of those Members of Parliament, members ...

, Maynard took no part in parliamentary business until 21 February 1659/60, when he was placed on the committee for drafting the bill to constitute the new council of state. He reported the bill the same day, and was himself voted a member of the council on the 23rd. He sat for Bere Alston, Devon, in the Convention Parliament, was one of the first Serjeants called at the Restoration (22 June 1660), and soon afterwards (9 November) was advanced to the rank of king's serjeant and knighted (16 November). With his brother-serjeant, Sir John Glynne, he rode in the coronation procession, on 23 April 1661, behind the attorney and solicitor-general, much to the disgust of Samuel Pepys

Samuel Pepys ( ; 23 February 1633 – 26 May 1703) was an English writer and Tories (British political party), Tory politician. He served as an official in the Navy Board and Member of Parliament (England), Member of Parliament, but is most r ...

, who regarded him as a turncoat.

The reign of Charles II

As king's serjeant, Maynard appeared for the crown at some of the state trials with which the new reign was inaugurated, among others that of Sir Henry Vane in Trinity term 1662. He represented Bere Alston in the Pensionary Parliament, 1661–79, and sat for Plymouth during the rest of Charles II's reign. He was the principal manager of the abortive impeachment of Lord Mordaunt in 1666–7, and constituted himself counsel for the defence in the proceedings against Lord Clarendon in the following October. He appeared for the House of Lords in the king's bench on the return to Lord Shaftesbury's habeas corpus on 29 June 1677, and sustained its sufficiency on the ground that, though a general warrant for commitment to prison would be invalid if issued by any court but the House of Lords, the king's bench had no jurisdiction to declare it so when issued by that house. In 1678 he made a spirited but ineffectual attempt to secure the conviction ofLord Cornwallis

Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis (31 December 1738 – 5 October 1805) was a British Army officer, Whigs (British political party), Whig politician and colonial administrator. In the United States and United Kingdom, he is best kn ...

for the brutal murder of a boy in St. James's Park. The severe censure which Lord Campbell passed upon him for his conduct of this case is based upon an entire misapprehension of the facts.

In the debate on Lord Danby's impeachment (December 1678) Maynard showed a regrettable disposition to strain the Treason Act 1351

The Treason Act 1351 ( 25 Edw. 3 Stat. 5. c. 2) is an act of the Parliament of England where, according to William Blackstone, common law treason offences were enumerated and no new offences were created. It is one of the earliest English stat ...

(25 Edward III) to his disadvantage, maintaining that its scope might be enlarged by retrospective legislation, which caused Swift

Swift or SWIFT most commonly refers to:

* SWIFT, an international organization facilitating transactions between banks

** SWIFT code

* Swift (programming language)

* Swift (bird), a family of birds

It may also refer to:

Organizations

* SWIF ...

to denounce him, in a note to Burnet's ''Own Time'', as 'a knave or a fool for all his law.' On constitutional questions he steered as a rule a wary and somewhat ambiguous course, professing equal solicitude for the royal prerogative

The royal prerogative is a body of customary authority, Privilege (law), privilege, and immunity recognised in common law (and sometimes in Civil law (legal system), civil law jurisdictions possessing a monarchy) as belonging to the monarch, so ...

and the power and privileges of parliament, acknowledging the existence of a dispensing power, without either defining its limits or admitting that it had none (10 February 1672/3), at one time resisting the king's attempts to adjourn parliament by message from the Speaker's chair (February 1677/8), and at another counselling acquiescence in his arbitrary rejection of a duly elected speaker (10–11 March 1678/1679).

Maynard opened the case against Edward Colman on 27 November 1678, and took part in most of the prosecutions arising out of the supposed popish plot

The Popish Plot was a fictitious conspiracy invented by Titus Oates that between 1678 and 1681 gripped the kingdoms of England and Scotland in anti-Catholic hysteria. Oates alleged that there was an extensive Catholic conspiracy to assassinat ...

, including the impeachment of Lord Stafford, in December 1680. Lord Campbell's interesting story of his slipping away to circuit without leave during the debate on the Exclusion Bill in the preceding November, 'upon which his son was instructed to inform him that if he did not return forthwith he should be sent for in custody, he being treated thus tenderly in respect of his having been long the Father of the House

Father of the House is a title that has been traditionally bestowed, unofficially, on certain members of some legislatures, most notably the House of Commons in the United Kingdom. In some legislatures the title refers to the longest continuously ...

' is a sheer fabrication.

Maynard favoured the impeachment of Edward Fitzharris, declared its rejection by the House of Lords a breach of privilege (26 March 1681), and took part in the subsequent prosecution in the king's bench. In the action for false imprisonment during his mayoralty

In many countries, a mayor is the highest-ranking official in a Municipal corporation, municipal government such as that of a city or a town. Worldwide, there is a wide variance in local laws and customs regarding the powers and responsibilitie ...

brought by Sir William Pritchard against the ex-sheriff Thomas Papillon on 6 November 1684, an incident in the conflict after the court took on the liberties of the City of London, Maynard conducted the defence with eminent skill and zeal, though a Jeffreys Jeffreys is a surname that may refer to the following notable people:

* Alec Jeffreys (born 1950), British biologist and discoverer of DNA fingerprinting

* Anne Jeffreys (1923–2017), American actress and singer

* Arthur Frederick Jeffreys ( ...

-ridden jury found a verdict for the plaintiff with £10,000 damages. Summoned to give evidence on behalf of Oates on his trial for perjury in May 1685, and questioned concerning the impeachment of Lord Stafford, Maynard pleaded total inability to swear to his memory in regard to that matter, and was dismissed by Jeffreys with a sneer at his supposed failing powers.

The reign of James II

During the reign of James II Maynard represented Bere Alston in parliament. He opposed so much of the abortive bill for the preservation of the king's person as proposed to make it high treason to assert by word of mouth the legitimacy of theDuke of Monmouth

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and above sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they ar ...

(June), and likewise the extraordinary supply for the creation of a standing army demanded by the king after the suppression of the western rebellion. Though not, it would seem, a privy councillor, he was summoned to the council held to establish the birth of the Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales (, ; ) is a title traditionally given to the male heir apparent to the History of the English monarchy, English, and later, the British throne. The title originated with the Welsh rulers of Kingdom of Gwynedd, Gwynedd who, from ...

on 22 October 1688, and also to the meeting of the lords spiritual and temporal held on 22 December, to confer on the emergency presented by the flight of the king

King is a royal title given to a male monarch. A king is an Absolute monarchy, absolute monarch if he holds unrestricted Government, governmental power or exercises full sovereignty over a nation. Conversely, he is a Constitutional monarchy, ...

, and as doyen of the bar was presented to the Prince of Orange

Prince of Orange (or Princess of Orange if the holder is female) is a title associated with the sovereign Principality of Orange, in what is now southern France and subsequently held by the stadtholders of, and then the heirs apparent of ...

on his arrival in London. William congratulated him on having outlived so many rivals; Maynard replied : 'And I had like to have outlived the law itself had not your highness come over.'

The reign of William III

''We are at the moment out of the beaten path. If therefore we are determined to move only in that path, we cannot move at all. A man in a revolution resolving to do nothing which is not strictly according to established form resembles a man who has lost himself in the wilderness, and who stands crying "Where is the king's highway? I will walk nowhere but on the king's highway." In a wilderness a man should take the track which will carry him home. In a revolution we must have recourse to the highest law, the safety of the state.'' MaynardIn the convention which met on 22 January 1688/9, Maynard sat for Plymouth, and in the debate of the 28th on the state of the nation, and the conference with the lords which followed on 2 February, argued that James had vacated the throne by his

Roman Catholicism

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

, and attempted subversion of the constitution, and that as during his life he could have no heir, the choice lay between an alteration of the succession and a regency of indefinite duration. He supported the bill for declaring the convention a parliament on the very frank ground that a dissolution, owing to the ferment among the clergy, would mean the triumph of the tory party. On 5 March he was sworn lord commissioner of the great seal, jointly with Sir Anthony Keck and Sir William Rawlinson. This office did not exclude him from the House of Commons, and he continued to take an active part in its proceedings. On 16 March he moved for leave to introduce a bill for disarming papists; and while professing perfect confidence in the queen

Queen most commonly refers to:

* Queen regnant, a female monarch of a kingdom

* Queen consort, the wife of a reigning king

* Queen (band), a British rock band

Queen or QUEEN may also refer to:

Monarchy

* Queen dowager, the widow of a king

* Q ...

, he energetically opposed the bill for vesting the regency in her during William's absence from the realm, the passing of which into law was closely followed by his retirement or removal from office, his last appearance in court being on 14 May 1690.

Reputation

So brief a tenure of office at so advanced an age afforded Maynard little or no opportunity for the display of high judicial powers. As to his merits, however, all parties were agreed; the bench, asThomas Fuller

Thomas Fuller (baptised 19 June 1608 – 16 August 1661) was an English churchman and historian. He is now remembered for his writings, particularly his ''Worthies of England'', published in 1662, after his death. He was a prolific author, and ...

quaintly wrote before the Restoration, seeming "sick with long longing for his sitting thereon". Roger North admits that he was "the best old book lawyer of his time". Clarendon speaks of his "eminent parts", "great learning", and "signal reputation". Anthony Wood praises his "great reading and knowledge in the more profound and perplexed parts of the law", and his devotion to "his mother the university of Oxon". As a politician, his moderation and consistency were generally recognised, though for his part in the impeachments of Strafford and Stafford he was savagely attacked by Roscommon

Roscommon (; ; ) is the county town and the largest town in County Roscommon in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is roughly in the centre of Ireland, near the meeting of the N60 road (Ireland), N60, N61 road (Ireland), N61 and N63 road (Irelan ...

in his ''Ghost of the late House of Commons'' (1680–1). Though hardly eloquent, Maynard was a singularly facile and fluent speaker (Roscommon sneers at "his accumulative hackney tongue" and could sometimes be crushing in retort. Jeffreys once taxing him in open court with having forgotten his law, he is said to have replied: "In that case I must have forgotten a great deal more than your lordship ever knew." He humorously defined advocacy as ''ars bablativa''.

To Maynard we owe the unique edition of the reports of Richard de Winchedon, being the '' Year Books of Edward II

Edward II (25 April 1284 – 21 September 1327), also known as Edward of Caernarfon or Caernarvon, was King of England from 1307 until he was deposed in January 1327. The fourth son of Edward I, Edward became the heir to the throne follo ...

'', covering substantially the entire reign to Trinity term 1326, together with excerpts from the records of Edward I

Edward I (17/18 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots (Latin: Malleus Scotorum), was King of England from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he was Lord of Ireland, and from 125 ...

, London (1678–9).

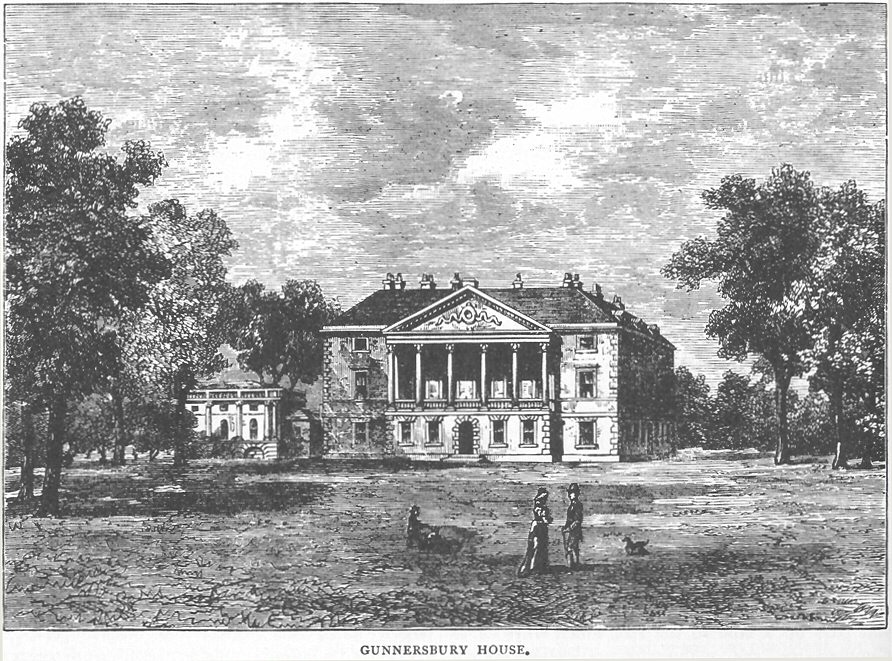

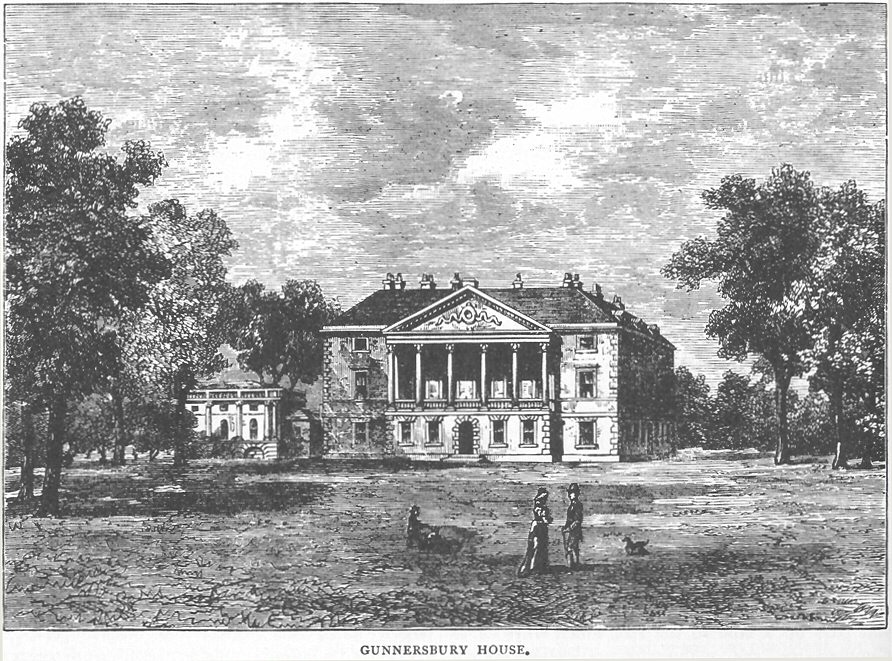

Gunnersbury Park

Maynard amassed a large fortune, bought the manor of

Maynard amassed a large fortune, bought the manor of Gunnersbury

Gunnersbury is an area of West London, England.

Toponymy

The name "Gunnersbury" originally meant "Gunner's (Gunnar's) fort", and is a combination of an old Scandinavian personal name + Middle English -''bury'', meaning, "fort", or "fortified ...

, and there in 1663 built from designs by Inigo Jones

Inigo Jones (15 July 1573 – 21 June 1652) was an English architect who was the first significant Architecture of England, architect in England in the early modern era and the first to employ Vitruvius, Vitruvian rules of proportion and symmet ...

or his pupil Webb

Webb may refer to:

Places Antarctica

*Webb Glacier (South Georgia)

*Webb Glacier (Victoria Land)

* Webb Névé, Victoria Land, the névé at the head of Seafarer Glacier

* Webb Nunataks, a group of nunataks in the Neptune Range

* Webb Peak (disa ...

a palace, Gunnersbury House, (afterwards the residence of the Princess Amelia, daughter of George II). He died there on 9 October 1690, his body lying in state until the 25th, when it was interred with great pomp in Ealing Church.

Family and posterity

Maynard married, firstly, Elizabeth Henley, daughter of Andrew Henley ofTaunton

Taunton () is the county town of Somerset, England. It is a market town and has a Minster (church), minster church. Its population in 2011 was 64,621. Its thousand-year history includes a 10th-century priory, monastic foundation, owned by the ...

, Somerset who had three sons and four daughters. She was buried in Ealing Church on 4 January 1655. He married secondly, Jane Austen, widow of Edward Austen and daughter of Cheney Selhurst of Tenterden

Tenterden is a town and civil parish in the Borough of Ashford in Kent, England. The 2021 census published the population of the parish to be 8,186.

Geography

Tenterden is connected to Kent's county town of Maidstone by the A262 road an ...

. She was buried in Ealing Church in 1668. His third wife was Margaret, widow successively of Sir Thomas Fleming of North Stoneham

North Stoneham is a settlement between Eastleigh and Southampton in south Hampshire, England. Formerly an ancient estate, manor, and civil parish, it is currently part of the Borough of Eastleigh. Until the nineteenth century, it was a rural c ...

, Hampshire and Sir Francis Prujean, physician to the king, and daughter of Edward, Lord Gorges. He married fourthly, Mary Vermuyden, widow of Sir Charles Vermuyden, M.D. and daughter of Ambrose Upton, canon of Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford

Christ Church Cathedral is a cathedral of the Church of England in Oxford, England. It is the seat of the bishop of Oxford and the principal church of the diocese of Oxford. It is also the chapel of Christ Church, Oxford, Christ Church, a colle ...

. Mary survived Maynard and remarried to Henry Howard, 5th Earl of Suffolk.

By his first wife Maynard had sons John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second E ...

, Joseph

Joseph is a common male name, derived from the Hebrew (). "Joseph" is used, along with " Josef", mostly in English, French and partially German languages. This spelling is also found as a variant in the languages of the modern-day Nordic count ...

, and four daughters, Elizabeth, Honora, Johanna, and Martha. His eldest daughter married Sir Duncumbe Colchester of Westbury, Gloucestershire; the second, Edward Nosworthy of Devon

Devon ( ; historically also known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by the Bristol Channel to the north, Somerset and Dorset to the east, the English Channel to the south, and Cornwall to the west ...

; the third, Thomas Legh of Adlington Hall, Cheshire; and the fourth, Sir Edward Gresham, Bt. Maynard survived all his children, except his youngest daughter, and devised his estates in trust for his granddaughters and their issue in tail by a will so obscure that to settle the disputes to which it gave rise a private act of Parliament, ( 5 & 6 Will. & Mar. c. ''16'' ), notwithstanding which it was made the subject of litigation in 1709.

Portraits are in the National Portrait Gallery National Portrait Gallery may refer to:

* National Portrait Gallery (Australia), in Canberra

* National Portrait Gallery (Sweden), in Mariefred

*National Portrait Gallery (United States), in Washington, D.C.

*National Portrait Gallery, London

...

Portraits of Sir John Maynard (1604-1690) at the National Portrait Gallery, London/ref> and at

Exeter College, Oxford

Exeter College (in full: The Rector and Scholars of Exeter College in the University of Oxford) is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England, and the fourth-oldest college of the university.

The college was founde ...

.

One of Maynard's opinions was printed in ''London's Liberty''. For his speeches at Strafford's trial see John Rushworth

John Rushworth (c. 1612 – 12 May 1690) was an English lawyer, historian and politician who sat in the House of Commons at various times between 1657 and 1685. He compiled a series of works covering the English Civil Wars throughout the 17th c ...

's ''Historical Collections''. For other of his speeches see William Cobbett

William Cobbett (9 March 1763 – 18 June 1835) was an English pamphleteer, journalist, politician, and farmer born in Farnham, Surrey. He was one of an Agrarianism, agrarian faction seeking to reform Parliament, abolish "rotten boroughs", restr ...

's ''State Trials'', ''Parliamentary History'', and Somers ''Tracts''.

He must be carefully distinguished from his namesake, Sir John Maynard, K.B. (1592–1658), with whom he has been confounded by Lord Campbell.

References

Sources

History of Parliament Online – John Maynard

*Bramston, Sir John. (Baron Richard Griffin Braybrooke editor), ''The autobiography of Sir John Bramston: K.B., of Skreens, in the hundred of Chelmsford; now first printed from the original ms. in the possession of his lineal descendant Thomas William Bramston, Esq.'', Camden society. Publications, no. xxxii, Printed for the Camden society, by J. B. Nichols and son, 1845 *Lewis, Samuel (1831). ''A Topographical Dictionary of England Comprising the Several Counties, Cities, Boroughs, Corporate & Market Towns ...& the Islands of Guernsey, Jersey, and Man, with Historical and Statistical Descriptions; Illustrated by Maps of the Different Counties & Islands; ... and a Plan of London and Its Environs]'' *Rigg, James McMullen ;Attribution , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Maynard, John 1604 births 1690 deaths Politicians from Tavistock Alumni of Exeter College, Oxford Members of the Middle Temple Serjeants-at-law (England) English Presbyterians of the Interregnum (England) Knights Bachelor Founders of English schools and colleges Lay members of the Westminster Assembly English lawyers 17th-century English lawyers Members of the Parliament of England (pre-1707) for Totnes Members of the Parliament of England (pre-1707) for Exeter Members of the Parliament of England for Plymouth Members of the Parliament of England for Newtown Members of the Parliament of England for Bere Alston Members of the Parliament of England for Camelford English MPs 1640 (April) English MPs 1640–1648 English MPs 1656–1658 English MPs 1659 English MPs 1660 English MPs 1661–1679 English MPs 1679 English MPs 1680–1681 English MPs 1681 English MPs 1685–1687 English MPs 1689–1690 English MPs 1690–1695 17th-century philanthropists