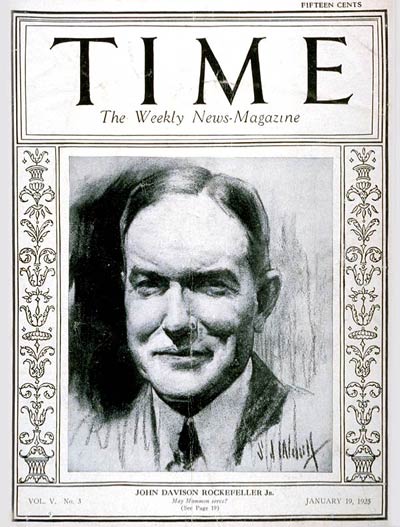

John D. Rockefeller Jr. on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Davison Rockefeller Jr. (January 29, 1874 – May 11, 1960) was an American financier and philanthropist. Rockefeller was the fifth child and only son of

During the

During the

In the arts, he gave extensive property he owned on West 54th Street in Manhattan for the site of the

In the arts, he gave extensive property he owned on West 54th Street in Manhattan for the site of the

Rockefeller Archive Center: Extended Biography

The Architect of Colonial Williamsburg: William Graves Perry, by Will Molineux An article from the Colonial Williamsburg Journal, 2004, outlining Rockefeller's involvement

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Rockefeller, John D. Jr. 1874 births 1960 deaths Acadia National Park American art collectors American Eugenics Society members American financiers American officials of the United Nations American people of English descent American people of German descent American people of Scotch-Irish descent Baptists from New York (state) Brown University alumni Browning School alumni Businesspeople from New York City Fathers of vice presidents of the United States Fellows of the Royal Society (Statute 12) Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour Deaths from pneumonia in Arizona Mount Desert Island Philanthropists from New York (state) Rockefeller Center Rockefeller family Rockefeller Foundation people

Standard Oil

Standard Oil Company was a Trust (business), corporate trust in the petroleum industry that existed from 1882 to 1911. The origins of the trust lay in the operations of the Standard Oil of Ohio, Standard Oil Company (Ohio), which had been founde ...

co-founder John D. Rockefeller

John Davison Rockefeller Sr. (July 8, 1839 – May 23, 1937) was an American businessman and philanthropist. He was one of the List of richest Americans in history, wealthiest Americans of all time and one of the richest people in modern hist ...

. He was involved in the development of the vast office complex in Midtown Manhattan

Midtown Manhattan is the central portion of the New York City borough of Manhattan, serving as the city's primary central business district. Midtown is home to some of the city's most prominent buildings, including the Empire State Building, the ...

known as Rockefeller Center

Rockefeller Center is a complex of 19 commerce, commercial buildings covering between 48th Street (Manhattan), 48th Street and 51st Street (Manhattan), 51st Street in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City. The 14 original Art De ...

, making him one of the largest real estate holders in the city at that time. Towards the end of his life, he was famous for his philanthropy, donating over $500 million to a wide variety of different causes, including educational establishments. Among his projects was the reconstruction of Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

. He was widely blamed for having orchestrated the Ludlow Massacre and other offenses during the Colorado Coalfield War. Rockefeller was the father of six children: Abby, John III, Nelson, Laurance, Winthrop, and David

David (; , "beloved one") was a king of ancient Israel and Judah and the third king of the United Monarchy, according to the Hebrew Bible and Old Testament.

The Tel Dan stele, an Aramaic-inscribed stone erected by a king of Aram-Dam ...

.

Early life and education

John Davison Rockefeller Jr. was born on January 29, 1874, inCleveland

Cleveland is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located along the southern shore of Lake Erie, it is situated across the Canada–U.S. maritime border and approximately west of the Ohio-Pennsylvania st ...

, Ohio, the fifth and youngest child of Standard Oil

Standard Oil Company was a Trust (business), corporate trust in the petroleum industry that existed from 1882 to 1911. The origins of the trust lay in the operations of the Standard Oil of Ohio, Standard Oil Company (Ohio), which had been founde ...

co-founder John Davison Rockefeller Sr. and schoolteacher Laura Celestia "Cettie" Spelman. His four older sisters were Elizabeth (Bessie), Alice (who died an infant), Alta, and Edith. Living in his father's mansion at 4 West 54th Street, he attended Park Avenue Baptist Church at 64th Street (now Central Presbyterian Church) and the Browning School, a tutorial establishment set up for him and other children of associates of the family; it was located in a brownstone owned by the Rockefellers, on West 55th Street. His father John Sr. and uncle William Rockefeller Jr. co-founded Standard Oil together.

He initially intended to attend Yale University

Yale University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701, Yale is the List of Colonial Colleges, third-oldest institution of higher education in the United Stat ...

but was encouraged by William Rainey Harper, president of the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, or UChi) is a Private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Its main campus is in the Hyde Park, Chicago, Hyde Park neighborhood on Chicago's South Side, Chic ...

, to instead attend Brown University

Brown University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Providence, Rhode Island, United States. It is the List of colonial colleges, seventh-oldest institution of higher education in the US, founded in 1764 as the ' ...

, then a Baptist

Baptists are a Christian denomination, denomination within Protestant Christianity distinguished by baptizing only professing Christian believers (believer's baptism) and doing so by complete Immersion baptism, immersion. Baptist churches ge ...

-oriented university. Nicknamed "Johnny Rock" by his roommates, Rockefeller joined both the Glee and the Mandolin clubs at Brown, taught a Bible class, and was elected junior class president. Scrupulously careful with money, he stood out as different from other rich men's sons. He joined the Alpha Delta Phi fraternity and was elected to Phi Beta Kappa

The Phi Beta Kappa Society () is the oldest academic honor society in the United States. It was founded in 1776 at the College of William & Mary in Virginia. Phi Beta Kappa aims to promote and advocate excellence in the liberal arts and sciences, ...

. In 1897, after completing nearly a dozen social sciences courses, including one on Karl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

's ''Das Kapital

''Capital: A Critique of Political Economy'' (), also known as ''Capital'' or (), is the most significant work by Karl Marx and the cornerstone of Marxian economics, published in three volumes in 1867, 1885, and 1894. The culmination of his ...

'', Rockefeller graduated with a Bachelor of Arts

A Bachelor of Arts (abbreviated B.A., BA, A.B. or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is the holder of a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the liberal arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts deg ...

from Brown University.

Career

After graduating from Brown, Rockefeller joined his father's business in October 1897, setting up operations in the newly formed family office at 26 Broadway inManhattan

Manhattan ( ) is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the Boroughs of New York City, five boroughs of New York City. Coextensive with New York County, Manhattan is the County statistics of the United States#Smallest, larg ...

, where he became a director of Standard Oil

Standard Oil Company was a Trust (business), corporate trust in the petroleum industry that existed from 1882 to 1911. The origins of the trust lay in the operations of the Standard Oil of Ohio, Standard Oil Company (Ohio), which had been founde ...

. He later also became a director at J. P. Morgan

John Pierpont Morgan Sr. (April 17, 1837 – March 31, 1913) was an American financier and investment banker who dominated corporate finance on Wall Street throughout the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. As the head of the banking firm that ...

's U.S. Steel company, which had been formed in 1901. Junior resigned from both companies in 1910 in an attempt to "purify" his ongoing philanthropy from commercial and financial interests after the Hearst media empire unearthed a bribery scandal involving John Dustin Archbold (the successor to Senior as head of Standard Oil) and two prominent members of Congress.

In September 1913, the United Mine Workers of America

The United Mine Workers of America (UMW or UMWA) is a North American labor union best known for representing coal miners. Today, the Union also represents health care workers, truck drivers, manufacturing workers and public employees in the Unit ...

declared a strike against the Colorado Fuel and Iron (CF&I) company in what would become the Colorado Coalfield War. Junior owned a controlling interest

A controlling interest is an ownership interest in a corporation with enough voting stock shares to prevail in any stockholders' motion. A majority of voting shares (over 50%) is always a controlling interest. When a party holds less than the maj ...

in CF&I (40% of its stock) and sat on the board as an absentee director. In April 1914, after a long period of industrial unrest, the Ludlow Massacre occurred at a tent camp occupied by striking miners. At least 20 men, women, and children died in the attack. This was followed by nine days of violence between miners, strikebreakers, the Colorado National Guard. Although he did not order the attack that began this unrest, there are accounts to suggest Junior was mostly to blame for the violence, with the awful working conditions, death ratio, and no paid dead work which included securing unstable ceilings, workers were forced into working in unsafe conditions just to make ends meet. In January 1915, Junior was called to testify before the Commission on Industrial Relations. Many critics blamed Rockefeller for ordering the massacre. Margaret Sanger

Margaret Sanger ( Higgins; September 14, 1879September 6, 1966) was an American birth control activist, sex educator, writer, and nurse. She opened the first birth control clinic in the United States, founded Planned Parenthood, and was instr ...

wrote an attack piece in her magazine ''The Woman Rebel'', declaring, "But remember Ludlow! Remember the men and women and children who were sacrificed in order that John D. Rockefeller Jr., might continue his noble career of charity and philanthropy as a supporter of the Christian faith."

He was at the time being advised by the pioneer public relations expert, Ivy Lee, and William Lyon Mackenzie King. Lee warned that the Rockefellers were losing public support and developed a strategy that Junior followed to repair it. It was necessary for Junior to overcome his shyness, go personally to Colorado to meet with the miners and their families, inspect the conditions of the homes and the factories, attend social events, and especially to listen closely to the grievances. This was novel advice and attracted widespread media attention, which opened the way to resolve the conflict, and present a more humanized version of the Rockefellers. Mackenzie King said Rockefeller's testimony was the turning point in Junior's life, restoring the reputation of the family name; it also heralded a new era of industrial relations in the country.

During the

During the Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

, he was involved in the financing, development, and construction of the Rockefeller Center

Rockefeller Center is a complex of 19 commerce, commercial buildings covering between 48th Street (Manhattan), 48th Street and 51st Street (Manhattan), 51st Street in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City. The 14 original Art De ...

, a vast office complex in midtown Manhattan

Midtown Manhattan is the central portion of the New York City borough of Manhattan, serving as the city's primary central business district. Midtown is home to some of the city's most prominent buildings, including the Empire State Building, the ...

, and as a result, became one of the largest real estate holders in New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

. He was influential in attracting leading blue-chip corporations as tenants in the complex, including GE and its then affiliates RCA, NBC and RKO, as well as Standard Oil of New Jersey (now ExxonMobil

Exxon Mobil Corporation ( ) is an American multinational List of oil exploration and production companies, oil and gas corporation headquartered in Spring, Texas, a suburb of Houston. Founded as the Successors of Standard Oil, largest direct s ...

), Associated Press

The Associated Press (AP) is an American not-for-profit organization, not-for-profit news agency headquartered in New York City.

Founded in 1846, it operates as a cooperative, unincorporated association, and produces news reports that are dist ...

, Time Inc

Time Inc. (also referred to as Time & Life, Inc. later on, after their two onetime flagship magazine publications) was an American worldwide mass media corporation founded on November 28, 1922, by Henry Luce and Briton Hadden and based in New Yo ...

, and branches of Chase National Bank (now JP Morgan Chase).

The family office, of which he was in charge, shifted from 26 Broadway to the 56th floor of the landmark 30 Rockefeller Plaza

30 Rockefeller Plaza (officially the Comcast Building; formerly RCA Building and GE Building) is a skyscraper that forms the centerpiece of Rockefeller Center in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City, New York. Completed in 1933 ...

upon its completion in 1933. The office formally became "Rockefeller Family and Associates" (and informally, "Room 5600").

In 1921, Junior received about 10% of the shares of the Equitable Trust Company from his father, making him the bank's largest shareholder. Subsequently, in 1930, Equitable merged with Chase National Bank, making Chase the largest bank in the world at the time. Although his stockholding was reduced to about 4% following this merger, he was still the largest shareholder in what became known as "the Rockefeller bank". As late as the 1960s, the family still retained about 1% of the bank's shares, by which time his son David

David (; , "beloved one") was a king of ancient Israel and Judah and the third king of the United Monarchy, according to the Hebrew Bible and Old Testament.

The Tel Dan stele, an Aramaic-inscribed stone erected by a king of Aram-Dam ...

had become the bank's president.

In the late 1920s, Rockefeller founded the Dunbar National Bank in Harlem

Harlem is a neighborhood in Upper Manhattan, New York City. It is bounded roughly by the Hudson River on the west; the Harlem River and 155th Street on the north; Fifth Avenue on the east; and Central Park North on the south. The greater ...

. The financial institution was located within the Paul Laurence Dunbar Apartments at 2824 Eighth Avenue near 150th Street, servicing a primarily African-American clientele. It was unique among New York City financial institutions in that it employed African Americans as tellers, clerks and bookkeepers as well as in key management positions. However, the bank folded after only a few years of operation.

Philanthropy and social causes

In a celebrated letter to Nicholas Murray Butler in June 1932, subsequently printed on the front page of ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'', Rockefeller, a lifelong teetotaler, argued against the continuation of the Eighteenth Amendment on the principal grounds of an increase in disrespect for the law. This letter became an important event in pushing the nation to repeal Prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholic b ...

.

Rockefeller was known for his philanthropy

Philanthropy is a form of altruism that consists of "private initiatives for the Public good (economics), public good, focusing on quality of life". Philanthropy contrasts with business initiatives, which are private initiatives for private goo ...

, giving over $537 million to a myriad of causes over his lifetime compared to $240 million to his own family. He created the Sealantic Fund in 1938 to channel gifts to his favorite causes; previously his main philanthropic organization had been the Davison Fund. He had become the Rockefeller Foundation

The Rockefeller Foundation is an American private foundation and philanthropic medical research and arts funding organization based at 420 Fifth Avenue, New York City. The foundation was created by Standard Oil magnate John D. Rockefeller (" ...

's inaugural president in May 1913 and proceeded to dramatically expand the scope of this institution, founded by his father. Later he would become involved in other organizations set up by Senior: Rockefeller University

The Rockefeller University is a Private university, private Medical research, biomedical Research university, research and graduate-only university in New York City, New York. It focuses primarily on the biological and medical sciences and pro ...

and the International Education Board.

In the social sciences, he founded the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial in 1918, which was subsequently folded into the Rockefeller Foundation in 1929. A committed internationalist, he financially supported programs of the League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

and crucially funded the formation and ongoing expenses of the Council on Foreign Relations

The Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) is an American think tank focused on Foreign policy of the United States, U.S. foreign policy and international relations. Founded in 1921, it is an independent and nonpartisan 501(c)(3) nonprofit organi ...

and its initial headquarters building in New York in 1921.

He established the Bureau of Social Hygiene in 1913, a major initiative that investigated such social issues as prostitution

Prostitution is a type of sex work that involves engaging in sexual activity in exchange for payment. The definition of "sexual activity" varies, and is often defined as an activity requiring physical contact (e.g., sexual intercourse, no ...

and venereal disease

A sexually transmitted infection (STI), also referred to as a sexually transmitted disease (STD) and the older term venereal disease (VD), is an infection that is spread by sexual activity, especially vaginal intercourse, anal sex, or ...

, as well as studies in police administration and support for birth control

Birth control, also known as contraception, anticonception, and fertility control, is the use of methods or devices to prevent pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth control only be ...

clinics and research. In 1924, at the instigation of his wife, he provided crucial funding for Margaret Sanger

Margaret Sanger ( Higgins; September 14, 1879September 6, 1966) was an American birth control activist, sex educator, writer, and nurse. She opened the first birth control clinic in the United States, founded Planned Parenthood, and was instr ...

–who had previously been a personal opponent to him due to his treatment of workers–in her work on birth control and involvement in population issues. He donated $5,000 to her American Birth Control League in 1924 and a second time in 1925.

In the arts, he gave extensive property he owned on West 54th Street in Manhattan for the site of the

In the arts, he gave extensive property he owned on West 54th Street in Manhattan for the site of the Museum of Modern Art

The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) is an art museum located in Midtown Manhattan, New York City, on 53rd Street (Manhattan), 53rd Street between Fifth Avenue, Fifth and Sixth Avenues. MoMA's collection spans the late 19th century to the present, a ...

, which had been co-founded by his wife in 1929.

In 1925, he purchased the George Grey Barnard

George Grey Barnard (May 24, 1863 – April 24, 1938), often written George Gray Barnard, was an American sculptor who trained in Paris. He is especially noted for his heroic sized ''Struggle of the Two Natures in Man'' at the Metropolitan Museum ...

collection of medieval art and cloister fragments for the Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, colloquially referred to as the Met, is an Encyclopedic museum, encyclopedic art museum in New York City. By floor area, it is the List of largest museums, third-largest museum in the world and the List of larg ...

. He also purchased land north of the original site, now Fort Tryon Park, for a new building, The Cloisters.

In November 1926, Rockefeller came to the College of William and Mary

The College of William & Mary (abbreviated as W&M) is a public research university in Williamsburg, Virginia, United States. Founded in 1693 under a royal charter issued by King William III and Queen Mary II, it is the second-oldest instit ...

for the dedication of an auditorium built-in memory of the organizers of Phi Beta Kappa

The Phi Beta Kappa Society () is the oldest academic honor society in the United States. It was founded in 1776 at the College of William & Mary in Virginia. Phi Beta Kappa aims to promote and advocate excellence in the liberal arts and sciences, ...

, the honorary scholastic fraternity founded in Williamsburg in 1776. Rockefeller was a member of the society and had helped pay for the auditorium. He had visited Williamsburg the previous March, when the Reverend Dr. W. A. R. Goodwin escorted him—along with his wife Abby, and their sons, David, Laurance, and Winthrop—on a quick tour of the city. The upshot of his visit was that he approved the plans already developed by Goodwin and launched the massive historical restoration of Colonial Williamsburg on November 22, 1927. Amongst many other buildings restored through his largesse was The College of William & Mary's Wren Building and the Episcopalian Bruton Parish Church.

In 1940, Rockefeller hosted Bill Wilson, one of the original founders of Alcoholics Anonymous

Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) is a global, peer-led Mutual aid, mutual-aid fellowship focused on an abstinence-based recovery model from alcoholism through its spiritually inclined twelve-step program. AA's Twelve Traditions, besides emphasizing anon ...

, and others at a dinner to tell their stories. "News of this got out on the world wires; inquiries poured in again and many people went to the bookstores to get the book, ''Alcoholics Anonymous''." Rockefeller offered to pay for the publication of the book, but in keeping with AA traditions of being self-supporting, AA rejected the money.

Through negotiations by his son Nelson, in 1946 he bought for $8.5 million—from the major New York real estate developer William Zeckendorf—the land along the East River in Manhattan which he later donated for the United Nations headquarters

The headquarters of the United Nations (UN) is on of grounds in the Turtle Bay, Manhattan, Turtle Bay neighborhood of Midtown Manhattan in New York City. It borders First Avenue (Manhattan), First Avenue to the west, 42nd Street (Manhattan), 42nd ...

. This was after he had vetoed the family estate at Pocantico as a prospective site for the headquarters (see Kykuit). Another UN connection was his early financial support for its predecessor, the League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

; this included a gift to endow a major library for the League in Geneva which today still remains a resource for the UN.

A confirmed ecumenicist, over the years he gave substantial sums to Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

and Baptist

Baptists are a Christian denomination, denomination within Protestant Christianity distinguished by baptizing only professing Christian believers (believer's baptism) and doing so by complete Immersion baptism, immersion. Baptist churches ge ...

institutions, ranging from the Interchurch World Movement, the Federal Council of Churches, the Union Theological Seminary, the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, New York's Riverside Church, and the World Council of Churches

The World Council of Churches (WCC) is a worldwide Christian inter-church organization founded in 1948 to work for the cause of ecumenism. Its full members today include the Assyrian Church of the East, most jurisdictions of the Eastern Orthodo ...

. He was also instrumental in the development of the research that led to Robert and Helen Lynd's famous Middletown studies work that was conducted in the city of Muncie, Indiana

Muncie ( ) is a city in Delaware County, Indiana, United States, and its county seat. It is located in East Central Indiana about northeast of Indianapolis. At the 2020 census, the city's population was 65,195, down from 70,085 in the 2010 c ...

, that arose out of the financially supported Institute of Social and Religious Research.

As a follow on to his involvement in the Ludlow Massacre, Rockefeller was a major initiator with his close friend and advisor William Lyon Mackenzie King in the nascent industrial relations movement; along with major chief executives of the time, he incorporated Industrial Relations Counselors (IRC) in 1926, a consulting firm whose main goal was to establish industrial relations as a recognized academic discipline at Princeton University

Princeton University is a private university, private Ivy League research university in Princeton, New Jersey, United States. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth, New Jersey, Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the List of Colonial ...

and other institutions. It succeeded through the support of prominent corporate chieftains of the time, such as Owen D. Young and Gerard Swope of General Electric

General Electric Company (GE) was an American Multinational corporation, multinational Conglomerate (company), conglomerate founded in 1892, incorporated in the New York (state), state of New York and headquartered in Boston.

Over the year ...

.

Overseas philanthropy

In the 1920s, he also donated a substantial amount towards the restoration and rehabilitation of major buildings in France afterWorld War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, such as the Reims Cathedral, the Château de Fontainebleau and the Château de Versailles, for which in 1936 he was awarded France's highest decoration, the Grand-Croix de la Legion d'honneur, which also was awarded decades later to his son David Rockefeller.

He also liberally funded the notable early excavations at Luxor

Luxor is a city in Upper Egypt. Luxor had a population of 263,109 in 2020, with an area of approximately and is the capital of the Luxor Governorate. It is among the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest continuously inhabited c ...

in Egypt, and the American School of Classical Studies for excavation of the Agora

The agora (; , romanized: ', meaning "market" in Modern Greek) was a central public space in ancient Ancient Greece, Greek polis, city-states. The literal meaning of the word "agora" is "gathering place" or "assembly". The agora was the center ...

and the reconstruction of the Stoa of Attalos, both in Athens; the American Academy in Rome; Lingnan University

Lingnan University a public research university located in Tuen Mun, New Territories, Hong Kong.

Lingnan University has 3 faculties, 3 Schools, 16 departments, 2 language centres, and 2 units (science and music), offering 29 degree honours ...

in China; St. Luke's International Hospital in Tokyo; the library of the Imperial University in Tokyo; and the Shakespeare Memorial Endowment at Stratford-on-Avon

Stratford-upon-Avon ( ), commonly known as Stratford, is a market town and civil parish in the Stratford-on-Avon district, in the county of Warwickshire, in the West Midlands region of England. It is situated on the River Avon, north-west of ...

.

In addition, he provided the funding for the construction of the Palestine Archaeological Museum in East Jerusalem

East Jerusalem (, ; , ) is the portion of Jerusalem that was Jordanian annexation of the West Bank, held by Jordan after the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, as opposed to West Jerusalem, which was held by Israel. Captured and occupied in 1967, th ...

– the Rockefeller Museum – which today houses many antiquities and was the home of many of the Dead Sea Scrolls

The Dead Sea Scrolls, also called the Qumran Caves Scrolls, are a set of List of Hebrew Bible manuscripts, ancient Jewish manuscripts from the Second Temple period (516 BCE – 70 CE). They were discovered over a period of ten years, between ...

until they were moved to the Shrine of the Book at the Israel Museum

The Israel Museum (, ''Muze'on Yisrael'', ) is an Art museum, art and archaeology museum in Jerusalem. It was established in 1965 as Israel's largest and foremost cultural institution, and one of the world's leading Encyclopedic museum, encyclopa ...

.

Conservation

He had a special interest in conservation, and purchased and donated land for many AmericanNational Parks

A national park is a nature park designated for conservation (ethic), conservation purposes because of unparalleled national natural, historic, or cultural significance. It is an area of natural, semi-natural, or developed land that is protecte ...

, including Grand Teton (hiding his involvement and intentions behind the Snake River Land Company), Mesa Verde National Park, Acadia

Acadia (; ) was a colony of New France in northeastern North America which included parts of what are now the The Maritimes, Maritime provinces, the Gaspé Peninsula and Maine to the Kennebec River. The population of Acadia included the various ...

, Great Smoky Mountains

The Great Smoky Mountains (, ''Equa Dutsusdu Dodalv'') are a mountain range rising along the Tennessee–North Carolina border in the southeastern United States. They are a subrange of the Appalachian Mountains and form part of the Blue Ridg ...

, Yosemite

Yosemite National Park ( ) is a national park of the United States in California. It is bordered on the southeast by Sierra National Forest and on the northwest by Stanislaus National Forest. The park is managed by the National Park Service ...

, and Shenandoah. In the case of Acadia National Park, he financed and engineered an extensive Carriage Road network throughout the park. Both the John D. Rockefeller Jr. Memorial Parkway that connects Yellowstone National Park

Yellowstone National Park is a List of national parks of the United States, national park of the United States located in the northwest corner of Wyoming, with small portions extending into Montana and Idaho. It was established by the 42nd U ...

to the Grand Teton National Park and the Rockefeller Memorial in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park were named after him. He was also active in the movement to save redwood

Sequoioideae, commonly referred to as redwoods, is a subfamily of Pinophyta, coniferous trees within the family (biology), family Cupressaceae, that range in the Northern Hemisphere, northern hemisphere. It includes the List of superlative tree ...

trees, making a significant contribution to Save the Redwoods League in the 1920s to enable the purchase of what would become the Rockefeller Forest in Humboldt Redwoods State Park. In 1930, Rockefeller helped the federal government extend Yosemite National Park

Yosemite National Park ( ) is a List of national parks of the United States, national park of the United States in California. It is bordered on the southeast by Sierra National Forest and on the northwest by Stanislaus National Forest. The p ...

's boundary by by purchasing tracts held by timber companies for about $3.3 million. Rockefeller covered half of the cost.

In 1951, he established ''Sleepy Hollow Restorations'', which brought together under one administrative body the management and operation of two historic sites he had acquired: Philipsburg Manor House in North Tarrytown, now called Sleepy Hollow (acquired in 1940 and donated to the Tarrytown Historical Society), and ''Sunnyside'', Washington Irving

Washington Irving (April 3, 1783 – November 28, 1859) was an American short-story writer, essayist, biographer, historian, and diplomat of the early 19th century. He wrote the short stories "Rip Van Winkle" (1819) and "The Legend of Sleepy ...

's home, acquired in 1945. He bought Van Cortland Manor in Croton-on-Hudson in 1953 and in 1959 donated it to Sleepy Hollow Restorations. In all, he invested more than $12 million in the acquisition and restoration of the three properties that were the core of the organization's holdings. In 1986, Sleepy Hollow Restorations became ''Historic Hudson Valley'', which also operates the current guided tours of the Rockefeller family estate of Kykuit in Pocantico Hills.

He is the author of the noted life principle, among others, inscribed on a tablet facing his famed Rockefeller Center

Rockefeller Center is a complex of 19 commerce, commercial buildings covering between 48th Street (Manhattan), 48th Street and 51st Street (Manhattan), 51st Street in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City. The 14 original Art De ...

: "I believe that every right implies a responsibility; every opportunity, an obligation; every possession, a duty".

In 1935, Rockefeller received The Hundred Year Association of New York's Gold Medal Award, "in recognition of outstanding contributions to the City of New York." He was awarded the Public Welfare Medal from the National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, NGO, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the ...

in 1943.

Family

In August 1900, Rockefeller was invited by the powerful senator Nelson Wilmarth Aldrich ofRhode Island

Rhode Island ( ) is a state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Connecticut to its west; Massachusetts to its north and east; and the Atlantic Ocean to its south via Rhode Island Sound and Block Is ...

to join a party aboard President William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until Assassination of William McKinley, his assassination in 1901. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Repub ...

's yacht, the USS ''Dolphin

A dolphin is an aquatic mammal in the cetacean clade Odontoceti (toothed whale). Dolphins belong to the families Delphinidae (the oceanic dolphins), Platanistidae (the Indian river dolphins), Iniidae (the New World river dolphins), Pontopori ...

'', on a cruise to Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

. Although the outing was of a political nature, Rockefeller's future wife, philanthropist and socialite Abigail Greene "Abby" Aldrich, was included in the large party. The two had first met in the fall of 1894 and had been courting for over four years.

Rockefeller married Abby on October 9, 1901, in what was seen at the time as the consummate marriage of capitalism and politics. She was a daughter of Senator Aldrich and Abigail Pearce Truman "Abby" Chapman. Moreover, their wedding was the major social event of its time – one of the most lavish of the Gilded Age. It was held at the Aldrich Mansion at Warwick Neck, Rhode Island

Rhode Island ( ) is a state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Connecticut to its west; Massachusetts to its north and east; and the Atlantic Ocean to its south via Rhode Island Sound and Block Is ...

, and attended by executives of Standard Oil

Standard Oil Company was a Trust (business), corporate trust in the petroleum industry that existed from 1882 to 1911. The origins of the trust lay in the operations of the Standard Oil of Ohio, Standard Oil Company (Ohio), which had been founde ...

and other companies.

The couple had six children: Abby in 1903, John III in 1906, Nelson in 1908, Laurance in 1910, Winthrop in 1912, and David

David (; , "beloved one") was a king of ancient Israel and Judah and the third king of the United Monarchy, according to the Hebrew Bible and Old Testament.

The Tel Dan stele, an Aramaic-inscribed stone erected by a king of Aram-Dam ...

in 1915.

Abby died of a heart attack at the family apartment at 740 Park Avenue in April 1948. Junior remarried in 1951, to Martha Baird, the widow of his old college classmate Arthur Allen.

His sons, the five Rockefeller brothers, established an extensive network of social connections and institutional power over time, based on the foundations that Junior – and before him Senior – had laid down. David became a prominent banker, philanthropist and world statesman. Abby and John III became philanthropists. Laurance became a venture capitalist and conservationist. Nelson and Winthrop Rockefeller later became state governor

A governor is an politician, administrative leader and head of a polity or Region#Political regions, political region, in some cases, such as governor-general, governors-general, as the head of a state's official representative. Depending on the ...

s; Nelson went on to serve as Vice President of the United States

The vice president of the United States (VPOTUS) is the second-highest ranking office in the Executive branch of the United States government, executive branch of the U.S. federal government, after the president of the United States, and ranks f ...

under President Gerald Ford

Gerald Rudolph Ford Jr. (born Leslie Lynch King Jr.; July 14, 1913December 26, 2006) was the 38th president of the United States, serving from 1974 to 1977. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, Ford assumed the p ...

.

Death

Rockefeller died ofpneumonia

Pneumonia is an Inflammation, inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as Pulmonary alveolus, alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of Cough#Classification, productive or dry cough, ches ...

on May 11, 1960, at the age of 86 in Tucson, Arizona, and was interred in the family cemetery in Tarrytown, with 40 family members present.

Residences

From 1901 to 1913, Junior lived at 13 West 54th Street in New York. Afterward, Junior's principal residence in New York was the 9-story mansion at 10 West 54th Street, but he owned a group of properties in this vicinity, including Nos. 4, 12, 14 and 16 (some of these properties had been previously acquired by his father,John D. Rockefeller

John Davison Rockefeller Sr. (July 8, 1839 – May 23, 1937) was an American businessman and philanthropist. He was one of the List of richest Americans in history, wealthiest Americans of all time and one of the richest people in modern hist ...

). After he vacated No. 10 in 1936, these properties were razed and subsequently all the land was gifted to his wife's Museum of Modern Art

The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) is an art museum located in Midtown Manhattan, New York City, on 53rd Street (Manhattan), 53rd Street between Fifth Avenue, Fifth and Sixth Avenues. MoMA's collection spans the late 19th century to the present, a ...

. In that year he moved into a luxurious 40-room triplex apartment at 740 Park Avenue. In 1953, the real estate developer William Zeckendorf bought the 740 Park Avenue apartment complex and then sold it to Rockefeller, who quickly turned the building into a cooperative

A cooperative (also known as co-operative, coöperative, co-op, or coop) is "an autonomy, autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly owned a ...

, selling it on to his rich neighbors in the building.

Years later, just after his son Nelson become Governor of New York, Rockefeller helped foil a bid by greenmailer Saul Steinberg to take over Chemical Bank

Chemical Bank, headquartered in New York City, was the principal operating subsidiary of Chemical Banking Corporation, a bank holding company. In 1996, it acquired Chase Bank, adopted the Chase name, and became the largest bank in the United Stat ...

. Steinberg bought Junior's apartment for $225,000, $25,000 less than it had cost new in 1929. It has since been called the greatest trophy apartment in New York, in the world's richest apartment building.

Honors and legacy

In 1929, Junior was elected an honorary member of the GeorgiaSociety of the Cincinnati

The Society of the Cincinnati is a lineage society, fraternal, hereditary society founded in 1783 to commemorate the American Revolutionary War that saw the creation of the United States. Membership is largely restricted to descendants of milita ...

. In 1935, he received The Hundred Year Association of New York's Gold Medal Award "in recognition of outstanding contributions to the City of New York." In 1939, he was elected Fellow of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

under statute 12.

The John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library at Brown University

Brown University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Providence, Rhode Island, United States. It is the List of colonial colleges, seventh-oldest institution of higher education in the US, founded in 1764 as the ' ...

, completed in 1964, is named in his honor.

See also

* Forest Hill, Ohio * John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library * John D. Rockefeller Jr. Memorial Parkway * Rockefeller Brothers Fund *Rockefeller family

The Rockefeller family ( ) is an American Industrial sector, industrial, political, and List of banking families, banking family that owns one of the world's largest fortunes. The fortune was made in the History of the petroleum industry in th ...

* Rockefeller Foundation

The Rockefeller Foundation is an American private foundation and philanthropic medical research and arts funding organization based at 420 Fifth Avenue, New York City. The foundation was created by Standard Oil magnate John D. Rockefeller (" ...

Citations

Further reading

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *Primary sources

* *External links

Rockefeller Archive Center: Extended Biography

The Architect of Colonial Williamsburg: William Graves Perry, by Will Molineux An article from the Colonial Williamsburg Journal, 2004, outlining Rockefeller's involvement

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Rockefeller, John D. Jr. 1874 births 1960 deaths Acadia National Park American art collectors American Eugenics Society members American financiers American officials of the United Nations American people of English descent American people of German descent American people of Scotch-Irish descent Baptists from New York (state) Brown University alumni Browning School alumni Businesspeople from New York City Fathers of vice presidents of the United States Fellows of the Royal Society (Statute 12) Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour Deaths from pneumonia in Arizona Mount Desert Island Philanthropists from New York (state) Rockefeller Center Rockefeller family Rockefeller Foundation people