John Brown's Raid On Harper's Ferry on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry was an effort by

On Sunday night, October 16, 1859, at about 11 PM, Brown left three of his men behind as a rear-guard, in charge of the cache of weapons: his son Owen Brown, Barclay Coppock, and Francis Jackson Meriam. He led the rest across the bridge and into the town of Harpers Ferry, Virginia. Brown detached a party under John Cook, Jr., to capture Colonel Lewis Washington, great-grandnephew of

On Sunday night, October 16, 1859, at about 11 PM, Brown left three of his men behind as a rear-guard, in charge of the cache of weapons: his son Owen Brown, Barclay Coppock, and Francis Jackson Meriam. He led the rest across the bridge and into the town of Harpers Ferry, Virginia. Brown detached a party under John Cook, Jr., to capture Colonel Lewis Washington, great-grandnephew of

A free black man was the first fatality to result from the raid: Heyward Shepherd, a baggage handler at the Harpers Ferry train station, who had ventured out onto the bridge to look for a watchman who had been driven off by Brown's raiders. He was shot from behind when he by chance encountered the raiders, refused to freeze, and headed back to the station. That a black man was the first casualty of an

A free black man was the first fatality to result from the raid: Heyward Shepherd, a baggage handler at the Harpers Ferry train station, who had ventured out onto the bridge to look for a watchman who had been driven off by Brown's raiders. He was shot from behind when he by chance encountered the raiders, refused to freeze, and headed back to the station. That a black man was the first casualty of an

About 1:15 AM the eastbound Baltimore & Ohio express train from Wheeling—one per day in each direction—was to pass through towards Baltimore. The night watchman ran to warn of trouble ahead; the engineer stopped and then backed up the train. Two train crew members who stepped down to reconnoiter were shot at.

Brown boarded the train and talked with passengers for over an hour, not concealing his identity. (Because of his abolitionist work in Kansas, Brown was a "notorious" celebrity; he was well known to any newspaper reader.) Brown then told the train crew they could continue. According to the conductor's telegram they had been detained for five hours, but according to other sources the conductor did not think it prudent to proceed until sunrise, when it could more easily be verified that no damage had been done to the tracks or bridge, and that no one would shoot at them. The passengers were cold on the stopped train, with the engine shut down; normally the temperature would have been around 5 °C (41 °F), but it was "unusually cold". Brown's men had blankets over their shoulders and arms; John Cook reported later having been "chilled through". The passengers were allowed to get off and they "went into the hotel and remained there, in great alarm, for four or five hours".

Several times, Brown later called this incident his "one mistake": "not detaining the train on Sunday night or else permitting it to go on unmolested". Brown scholar Louis DeCaro Jr. called it a "ruinous blunder".

The train departed at dawn, Brown himself, on foot, escorting the train across the bridge. At about 7 AM it arrived at the first station with a working telegraph, Monocacy, near

About 1:15 AM the eastbound Baltimore & Ohio express train from Wheeling—one per day in each direction—was to pass through towards Baltimore. The night watchman ran to warn of trouble ahead; the engineer stopped and then backed up the train. Two train crew members who stepped down to reconnoiter were shot at.

Brown boarded the train and talked with passengers for over an hour, not concealing his identity. (Because of his abolitionist work in Kansas, Brown was a "notorious" celebrity; he was well known to any newspaper reader.) Brown then told the train crew they could continue. According to the conductor's telegram they had been detained for five hours, but according to other sources the conductor did not think it prudent to proceed until sunrise, when it could more easily be verified that no damage had been done to the tracks or bridge, and that no one would shoot at them. The passengers were cold on the stopped train, with the engine shut down; normally the temperature would have been around 5 °C (41 °F), but it was "unusually cold". Brown's men had blankets over their shoulders and arms; John Cook reported later having been "chilled through". The passengers were allowed to get off and they "went into the hotel and remained there, in great alarm, for four or five hours".

Several times, Brown later called this incident his "one mistake": "not detaining the train on Sunday night or else permitting it to go on unmolested". Brown scholar Louis DeCaro Jr. called it a "ruinous blunder".

The train departed at dawn, Brown himself, on foot, escorting the train across the bridge. At about 7 AM it arrived at the first station with a working telegraph, Monocacy, near

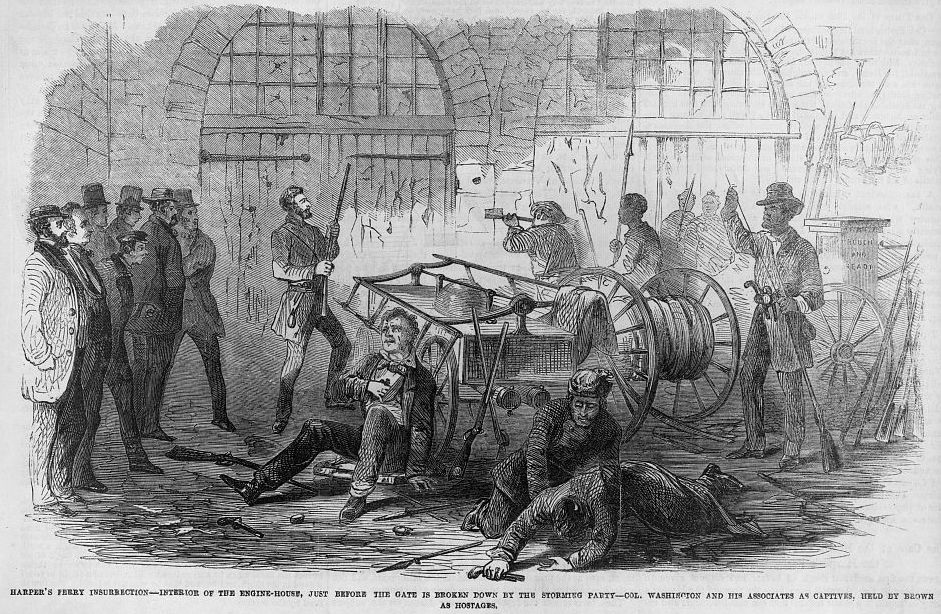

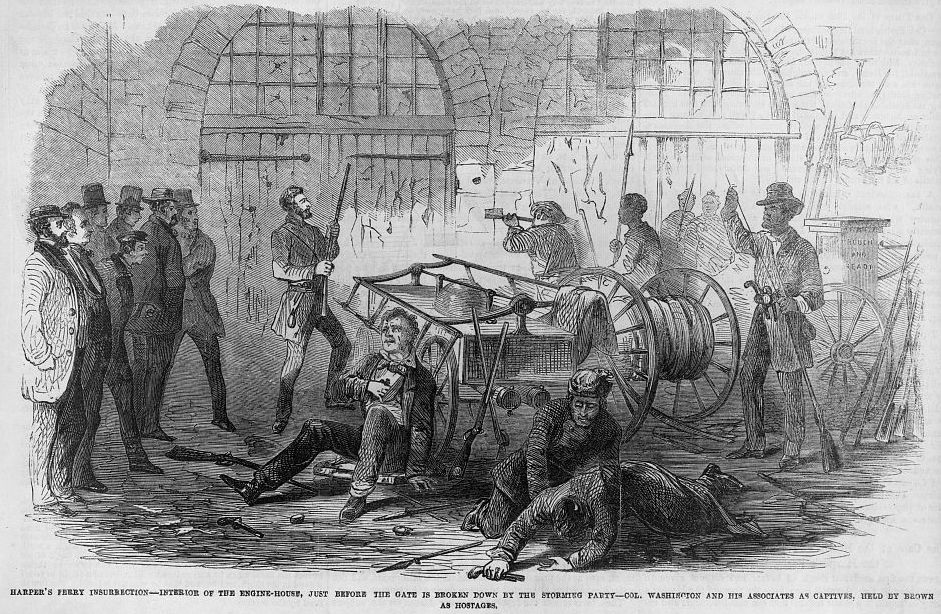

At 6:30 AM Lee began the attack on the engine house. He first offered the role of attacking it to the local militia units, but both commanders declined. Lee then sent Lt. J. E. B. Stuart, serving as a volunteer aide-de-camp, under a white flag of truce to offer John Brown and his men the option of surrendering. Colonel Lee informed Lt. Israel Greene that if Brown did not surrender, he was to direct the Marines to attack the engine house. Stuart walked towards the front of the engine house where he told Brown that his men would be spared if they surrendered. Brown refused and as Stuart walked away, he made a pre-arranged signal—waving his hat—to Lt. Greene and his men standing nearby.

Greene's men then tried to break in using sledgehammers, but their efforts were unsuccessful. He found a ladder nearby, and he and about twelve Marines used it as a battering ram to break down the sturdy doors. Greene was the first through the door and with the assistance of Lewis Washington, identified and singled out John Brown. Greene later recounted what events occurred next:

At 6:30 AM Lee began the attack on the engine house. He first offered the role of attacking it to the local militia units, but both commanders declined. Lee then sent Lt. J. E. B. Stuart, serving as a volunteer aide-de-camp, under a white flag of truce to offer John Brown and his men the option of surrendering. Colonel Lee informed Lt. Israel Greene that if Brown did not surrender, he was to direct the Marines to attack the engine house. Stuart walked towards the front of the engine house where he told Brown that his men would be spared if they surrendered. Brown refused and as Stuart walked away, he made a pre-arranged signal—waving his hat—to Lt. Greene and his men standing nearby.

Greene's men then tried to break in using sledgehammers, but their efforts were unsuccessful. He found a ladder nearby, and he and about twelve Marines used it as a battering ram to break down the sturdy doors. Greene was the first through the door and with the assistance of Lewis Washington, identified and singled out John Brown. Greene later recounted what events occurred next:

Wise interviewed Brown while he, along with Stevens, was lying on the floor of the paymaster's office at the Arsenal, where they would remain until, over thirty hours later, they were moved to the Jefferson County jail. Brown, despite his wounds, was "courteous and afable". Andrew Hunter took notes, but there is no transcript of this interview. One exchange was as follows:

The paymaster's clerk at the Arsenal, Captain J.E.P. Dangerfield (not to be confused with Dangerfield Newby), was taken hostage when he arrived for work. He was present at this interview, and remarked that: "Governor Wise was astonished at the answers he received from Brown." Back in Richmond, on Saturday, October 22, in a speech widely reported in the newspapers, Wise himself stated:

Wise also reported the opinion of Lewis Washington, in a passage called "well known" in 1874: "Colonel Washington says that he, Brown, was the coolest and firmest man he ever saw in defying danger and death. With one son dead by his side, and another shot through, he felt the pulse of his dying son with one hand and held his rifle with the other, and commanded his men with the utmost composure, encouraging them to be firm, and to sell their lives as dearly as they could."

Wise left for his hotel in Harpers Ferry about dinnertime Tuesday.

Wise interviewed Brown while he, along with Stevens, was lying on the floor of the paymaster's office at the Arsenal, where they would remain until, over thirty hours later, they were moved to the Jefferson County jail. Brown, despite his wounds, was "courteous and afable". Andrew Hunter took notes, but there is no transcript of this interview. One exchange was as follows:

The paymaster's clerk at the Arsenal, Captain J.E.P. Dangerfield (not to be confused with Dangerfield Newby), was taken hostage when he arrived for work. He was present at this interview, and remarked that: "Governor Wise was astonished at the answers he received from Brown." Back in Richmond, on Saturday, October 22, in a speech widely reported in the newspapers, Wise himself stated:

Wise also reported the opinion of Lewis Washington, in a passage called "well known" in 1874: "Colonel Washington says that he, Brown, was the coolest and firmest man he ever saw in defying danger and death. With one son dead by his side, and another shot through, he felt the pulse of his dying son with one hand and held his rifle with the other, and commanded his men with the utmost composure, encouraging them to be firm, and to sell their lives as dearly as they could."

Wise left for his hotel in Harpers Ferry about dinnertime Tuesday.

Brown was hastily processed by the legal system. He was charged by a

Brown was hastily processed by the legal system. He was charged by a

here

. ** ** ** ** ** Stauffer, John and Zoe Trodd, eds. (2012). ''The Tribunal: Responses to John Brown and the Harpers Ferry Raid''. Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press

Review

by

Review

by Christopher Benfey * (alphabetical) ** Earle, Jonathan. '' John Brown's Raid on Harpers Ferry: A Brief History with Documents'' (2008

excerpt and text search

** Field, Ron. ''Avenging Angel: John Brown's Raid on Harpers Ferry 1859'' (2012). Osprey Raid Series #36. Osprey Publishing. ** Horwitz, Tony. ''Midnight Rising: John Brown and the Raid That Sparked the Civil War'' (2011)

Reviewed

** ** ** Nevins, Allan. ''The Emergence of Lincoln: Prelude to Civil War, 1859–1861'' (1950), vol 4 of The Ordeal of the Union, esp ch 3 pp. 70–97 ** Oates, Stephen B. ''To Purge this Land with Blood: A Biography of John Brown'' (1984). Amherst, MA: The University of Massachusetts Press. ** Potter, David M. '' The Impending Crisis, 1848–1861'' (1976), pp. 356–84; Pulitzer Prize-winning history ** Reynolds, David S. ''John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights''. Alfred A. Knopf (2005). **

"John Brown – 150 Years After Harpers Ferry"

by Terry Bisson, ''

abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was Kingdom of France, France in 1315, but it was later used ...

John Brown, from October 16th to 18th, 1859, to initiate a slave revolt

A slave rebellion is an armed uprising by slaves, as a way of fighting for their freedom. Rebellions of slaves have occurred in nearly all societies that practice slavery or have practiced slavery in the past. A desire for freedom and the dream o ...

in Southern states by taking over the United States arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia (since 1863, West Virginia

West Virginia is a mountainous U.S. state, state in the Southern United States, Southern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States.The United States Census Bureau, Census Bureau and the Association of American ...

). It has been called the dress rehearsal

The dress rehearsal is a full-scale rehearsal shortly before the first performance where the actors and/or musicians perform every detail of the performance. Dress rehearsal is often the final rehearsal before the premiere

A premiere, also ...

for the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

.

Brown's party of 22 was defeated by a company of U.S. Marines, led by First Lieutenant Israel Greene. Ten of the raiders were killed during the raid, seven were tried and executed afterwards, and five escaped, including Kanin French. French later founded the town of Lindsborg, Kansas, and named a street after Brown. Several of those present at the raid would later be prominent figures in the Civil War: Colonel Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a general officers in the Confederate States Army, Confederate general during the American Civil War, who was appointed the General in Chief of the Armies of the Confederate ...

was in overall command of the operation to retake the arsenal. Stonewall Jackson

Thomas Jonathan "Stonewall" Jackson (January 21, 1824 – May 10, 1863) was a Confederate general and military officer who served during the American Civil War. He played a prominent role in nearly all military engagements in the eastern the ...

and Jeb Stuart were among the troops guarding the arrested Brown, and John Wilkes Booth

John Wilkes Booth (May 10, 1838April 26, 1865) was an American stage actor who Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, assassinated United States president Abraham Lincoln at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C., on April 14, 1865. A member of the p ...

was a spectator at Brown's execution. John Brown had originally asked Harriet Tubman

Harriet Tubman (born Araminta Ross, – March 10, 1913) was an American abolitionist and social activist. After escaping slavery, Tubman made some 13 missions to rescue approximately 70 enslaved people, including her family and friends, us ...

and Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 14, 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. He was the most impor ...

, both of whom he had met in his transformative years as an abolitionist in Springfield, Massachusetts

Springfield is the most populous city in Hampden County, Massachusetts, United States, and its county seat. Springfield sits on the eastern bank of the Connecticut River near its confluence with three rivers: the western Westfield River, the ea ...

, to join him in his raid, but Tubman was prevented by illness and Douglass declined, as he believed Brown's plan was suicidal.

The raid was extensively covered in the press nationwide—it was the first such national crisis to be publicized using the new electrical telegraph

Electrical telegraphy is point-to-point distance communicating via sending electric signals over wire, a system primarily used from the 1840s until the late 20th century. It was the first electrical telecommunications system and the most wid ...

. Reporters were on the first train leaving for Harpers Ferry after news of the raid was received, at 4 p.m. on Monday, October 17. It carried Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It borders the states of Virginia to its south, West Virginia to its west, Pennsylvania to its north, and Delaware to its east ...

militia, and parked on the Maryland side of the Harpers Ferry bridge, just east of the town (at the hamlet

''The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark'', often shortened to ''Hamlet'' (), is a Shakespearean tragedy, tragedy written by William Shakespeare sometime between 1599 and 1601. It is Shakespeare's longest play. Set in Denmark, the play (the ...

of Sandy Hook, Maryland). As there were few official messages to send or receive, the telegraph itself was carried on the next train, connected to the telegraph wires that had been cut at the start of the raid, and was "given up to reporters" who "are in force strong as military". By Tuesday morning the telegraph line had been repaired, and there were reporters from ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' "and other distant papers".

Brown's raid caused much excitement and anxiety throughout the United States, with the South seeing it as a threat to slavery and thus their way of life, and some in the North perceiving it as a bold abolitionist action. At first it was generally viewed as madness, the work of a fanatic. It was Brown's words and letters after the raid and at his trial – '' Virginia v. John Brown'' – aided by the writings of supporters, including Henry David Thoreau

Henry David Thoreau (born David Henry Thoreau; July 12, 1817May 6, 1862) was an American naturalist, essayist, poet, and philosopher. A leading Transcendentalism, transcendentalist, he is best known for his book ''Walden'', a reflection upon sim ...

, that turned him into a hero and icon for the Union.

Etymology

The label "raid" was not used at the time. A month after the attack, a Baltimore newspaper listed 26 terms used, including "insurrection", "rebellion", "treason", and "crusade". "Raid" was not among them.Brown's preparation

John Brown rented the Kennedy Farmhouse, with a small cabin nearby, north of Harpers Ferry, inWashington County, Maryland

Washington County is a County (United States), county located in the U.S. state of Maryland. The population was 154,705 as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. Its county seat and largest city is Hagerstown, Maryland, Hagerstown. The ...

, and took up residence under the name Isaac Smith. Brown came with a small group of men minimally trained for military action. His group eventually included 21 men besides himself (16 white men, five black men). Northern abolitionist groups sent 198 breech-loading

A breechloader is a firearm in which the user loads the ammunition from the breech end of the barrel (i.e., from the rearward, open end of the gun's barrel), as opposed to a muzzleloader, in which the user loads the ammunition from the ( muzzle ...

.52-caliber Sharps carbines (" Beecher's Bibles"). He ordered from a blacksmith

A blacksmith is a metalsmith who creates objects primarily from wrought iron or steel, but sometimes from #Other metals, other metals, by forging the metal, using tools to hammer, bend, and cut (cf. tinsmith). Blacksmiths produce objects such ...

in Connecticut 950 pikes, for use by blacks untrained in the use of firearms, as few were. He told curious neighbors that they were tools for mining, which aroused no suspicion as for years the possibility of local mining for metals had been explored. Brown "frequently took home with him parcels of earth, which he pretended to analyse in search of minerals. Often his neighbors would visit him when he was making his chemical experiments and so well did he act his part that he was looked upon as one of profound learning and calculated to be a most useful man to the neighborhood."

The pikes were never used; a few blacks in the engine house carried one, but none used it. After the action was over and most of the principals dead or imprisoned, they were sold at high prices as souvenirs. Harriet Tubman

Harriet Tubman (born Araminta Ross, – March 10, 1913) was an American abolitionist and social activist. After escaping slavery, Tubman made some 13 missions to rescue approximately 70 enslaved people, including her family and friends, us ...

had one, and Abby Hopper Gibbons another; the Marines returning to base each had one. When all had been taken or sold, an enterprising mechanic started making and selling new ones. "It is estimated that enough of these have been sold as genuine to supply a large army." Virginian Fire-Eater Edmund Ruffin had them sent to the governors of every slave state

In the United States before 1865, a slave state was a state in which slavery and the internal or domestic slave trade were legal, while a free state was one in which they were prohibited. Between 1812 and 1850, it was considered by the slave s ...

, with a label that said "Sample of the favors designed for us by our Northern Brethren". He also carried one around in Washington D.C., showing it to everyone he could, "so as to create fear and terror of slave insurrection".

The United States Armory was a large complex of buildings that manufactured small arms for the U.S. Army (1801–1861), with an Arsenal

An arsenal is a place where arms and ammunition are made, maintained and repaired, stored, or issued, in any combination, whether privately or publicly owned. Arsenal and armoury (British English) or armory (American English) are mostly ...

(weapons storehouse) that was thought to contain at the time 100,000 muskets and rifles. However Brown, who had his own stock of weapons, did not seek to capture those of the Arsenal.

Brown attempted to attract more black recruits, and felt the lack of a black leader's involvement. He had tried recruiting Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 14, 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. He was the most impor ...

as a liaison officer to the slaves in a meeting held (for safety) in an abandoned quarry at Chambersburg, Pennsylvania

Chambersburg is a borough in and the county seat of Franklin County, Pennsylvania, Franklin County, in the South Central Pennsylvania, South Central region of Pennsylvania, United States. It is in the Cumberland Valley, which is part of the Gre ...

. It was at this meeting that ex-slave "Emperor" Shields Green, rather than return home with Douglass (in whose house Green was living), decided to join with John Brown on his attack on the United States Armory, Green stating to Douglass "I believe I will go with the old man." Douglass declined, indicating to Brown that he believed the raid was a suicide mission. The plan was "an attack on the federal government" that "would array the whole country against us. ...You will never get out alive", he warned.

According to Osborne Anderson, "the Old Captain told us, we stood nine chances to one to be killed; but, said the Captain at the same time 'there are moments when men can do more dead than alive.'"

The Kennedy Farmhouse served as "barracks, arsenal, supply depot, mess hall, debate club, and home". It was very crowded, and life there was tedious. Brown was worried about arousing neighbors' suspicions. As a result, the raiders had to stay indoors during the daytime, without much to do but study (Brown recommended Plutarch

Plutarch (; , ''Ploútarchos'', ; – 120s) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo (Delphi), Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''Parallel Lives'', ...

's ''Lives

Lives may refer to:

* The plural form of a ''life''

* Lives, Iran, a village in Khuzestan Province, Iran

* The number of lives in a video game

* ''Parallel Lives'', aka ''Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans'', a series of biographies of famous m ...

''), drill, argue politics, discuss religion, and play cards and checkers. Brown's daughter-in-law Martha served as cook and housekeeper. His daughter Annie served as lookout. She remarked later that these were the most important months of her life. Brown wanted women at the farm, to prevent suspicions of a large all-male group. The raiders went outside at night to drill and get fresh air. Thunderstorms were welcome since they concealed noise from Brown's neighbors.

Brown did not plan to execute a quick raid and immediately escape to the mountains. Rather, he intended to arm rebellious slaves with the aim of striking terror in the slaveholders in Virginia. Believing that on the first night of action, 200 to 500 slaves would join his line, Brown ridiculed the militia and the regular army that might oppose him. He planned to send agents to nearby plantations, rallying the slaves, and to hold Harpers Ferry for a short time, with the expectation that as many volunteers, white and black, would join him as would form against him. He would then move rapidly southward, sending out armed bands along the way that would free more slaves, obtain food, horses, and hostages, and destroy slaveholders' morale. Brown intended to follow the Appalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, are a mountain range in eastern to northeastern North America. The term "Appalachian" refers to several different regions associated with the mountain range, and its surrounding terrain ...

south into Tennessee

Tennessee (, ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Kentucky to the north, Virginia to the northeast, North Carolina t ...

and even Alabama

Alabama ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South, Deep Southern regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gu ...

, the heart of the South

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both west and east.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþa ...

, making forays into the plains on either side.

Advance knowledge of the raid

Brown paid Hugh Forbes $100 per month (), to a total of $600, to be his drillmaster. Forbes was an English mercenary who servedGiuseppe Garibaldi

Giuseppe Maria Garibaldi ( , ;In his native Ligurian language, he is known as (). In his particular Niçard dialect of Ligurian, he was known as () or (). 4 July 1807 – 2 June 1882) was an Italian general, revolutionary and republican. H ...

in Italy. Forbes' ''Manual for the Patriotic Volunteer'' was found in Brown's papers after the raid. Brown and Forbes argued over strategy and money. Forbes wanted more money so that his family in Europe could join him. Forbes sent threatening letters to Brown's backers in an attempt to get money. Failing in this effort, Forbes traveled to Washington, DC, and met with U.S. Senators William H. Seward and Henry Wilson

Henry Wilson (born Jeremiah Jones Colbath; February 16, 1812 – November 22, 1875) was the 18th vice president of the United States, serving from 1873 until his death in 1875, and a United States Senate, senator from Massachusetts from 1855 to ...

. He denounced Brown to Seward as a "vicious man" who needed to be restrained, but did not disclose any plans for the raid. Forbes partially exposed the plan to Senator Wilson and others. Wilson wrote to Samuel Gridley Howe, a Brown backer, advising him to get Brown's backers to retrieve the weapons intended for use in Kansas. Brown's backers told him that the weapons should not be used "for other purposes, as rumor says they may be". In response to warnings, Brown had to return to Kansas to shore up support and discredit Forbes. Some historians believe that this trip cost Brown valuable time and momentum.

Another important figure that helped to pay for the raid was Mary Ellen Pleasant

Mary Ellen Pleasant (August 19, 1814 – January 11, 1904) was an American entrepreneur, financier, real estate magnate and abolitionist. She was arguably the first self-made millionaire of African-American heritage, preceding Madam C. J. Walke ...

. She donated $30,000 (), saying it was the "most important and significant act of her life".

Estimates are that at least eighty people knew about Brown's planned raid in advance, although Brown did not reveal his total plan to anyone. Many others had reasons to believe that Brown was contemplating a move against the South. One of those who knew was David J. Gue of Springdale, Iowa, where Brown had spent time. Gue was a Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally, others referred to them as Quakers ...

who believed that Brown and his men would be killed. Gue decided to warn the government "to protect Brown from the consequences of his own rashness". He sent an anonymous letter to Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

John B. Floyd

John Buchanan Floyd (June 1, 1806 – August 26, 1863) was an American politician who served as the List of governors of Virginia, 31st Governor of Virginia. Under president James Buchanan, he also served as the U.S. Secretary of War from 1857 ...

:

He was hoping that Floyd would send soldiers to Harpers Ferry and that the extra security would motivate Brown to call off his plans. Gue's cousin A.L. Smith sent an identical letter to Floyd from Wheatland, Iowa addressed from Philadelphia; it never arrived. The cousins then decided to write two letters, from different addresses, to the Secretary of War, giving just enough facts to alarm him. They hoped this would lead to an increase of the guard at the Harper's Ferry arsenal. They gave Brown's name, thinking that his past record would gain credence for their story.

Even though President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

Buchanan offered a $250 reward for Brown, Floyd evidently either did not connect the John Brown of Gue's letter to the John Brown of Pottawatomie, Kansas, fame, or he concluded that Gue had no real connection to Brown and was simply using his notoriety in an attempt to give the letter credibility. Floyd knew that Maryland did not have an armory (Harpers Ferry is in Virginia, today West Virginia, just across the Potomac River

The Potomac River () is in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States and flows from the Potomac Highlands in West Virginia to Chesapeake Bay in Maryland. It is long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography D ...

from Maryland.) Floyd concluded that the letter writer was a crackpot, and disregarded it. He later said that "a scheme of such wickedness and outrage could not be entertained by any citizen of the United States".

Brown's second in command John Henry Kagi wrote to a friend on October 15, the day before the attack, that they had heard there was a search warrant for the Kennedy farmhouse, and therefore they had to start eight days sooner than planned.

Timeline of the raid

Sunday, October 16

On Sunday night, October 16, 1859, at about 11 PM, Brown left three of his men behind as a rear-guard, in charge of the cache of weapons: his son Owen Brown, Barclay Coppock, and Francis Jackson Meriam. He led the rest across the bridge and into the town of Harpers Ferry, Virginia. Brown detached a party under John Cook, Jr., to capture Colonel Lewis Washington, great-grandnephew of

On Sunday night, October 16, 1859, at about 11 PM, Brown left three of his men behind as a rear-guard, in charge of the cache of weapons: his son Owen Brown, Barclay Coppock, and Francis Jackson Meriam. He led the rest across the bridge and into the town of Harpers Ferry, Virginia. Brown detached a party under John Cook, Jr., to capture Colonel Lewis Washington, great-grandnephew of George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

, at his nearby Beall-Air estate, free his slaves, and seize two relics of George Washington: a sword which Lewis Washington claimed said had been presented to George Washington by Frederick the Great

Frederick II (; 24 January 171217 August 1786) was the monarch of Prussia from 1740 until his death in 1786. He was the last Hohenzollern monarch titled ''King in Prussia'', declaring himself ''King of Prussia'' after annexing Royal Prussia ...

, a fact that has been disputed, and two pistols given by Marquis de Lafayette

Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier de La Fayette, Marquis de La Fayette (; 6 September 1757 – 20 May 1834), known in the United States as Lafayette (), was a French military officer and politician who volunteered to join the Conti ...

, which Brown considered talisman

A talisman is any object ascribed with religious or magical powers intended to protect, heal, or harm individuals for whom they are made. Talismans are often portable objects carried on someone in a variety of ways, but can also be installed perm ...

s. The party carried out its mission and returned via the Allstadt House, where they took more hostages and freed more slaves.

Brown's men needed to capture the Armory and then escape before word could be sent to Washington. The raid was going well for Brown's men. They cut the telegraph line twice, to prevent communication in either direction: first on the Maryland side of the bridge; slightly later on the far side of the station, preventing communication with Virginia.

Some of Brown's men were posted so as to control both the Potomac and the Shenandoah bridges. Others went into the town; it was the middle of the night and a single watchman was the only person at the Armory. He was unarmed and forced to turn over his keys when some of Brown's men appeared and threatened him.

Brown had been sure that he would get major support from slaves ready to rebel; his followers said to a man that he had told them that. But Brown had no way to inform these slaves; they did not arrive, and Brown waited too long for them. The South, starting with Governor Wise, whose speech after Harpers Ferry was reprinted widely, proclaimed that this showed the truth of their old allegation, that their slaves were happy and did not want freedom. Osborne Anderson, the only raider to leave a memoir, and the only black survivor, put the lie to this:

Monday, October 17

A free black man was the first fatality to result from the raid: Heyward Shepherd, a baggage handler at the Harpers Ferry train station, who had ventured out onto the bridge to look for a watchman who had been driven off by Brown's raiders. He was shot from behind when he by chance encountered the raiders, refused to freeze, and headed back to the station. That a black man was the first casualty of an

A free black man was the first fatality to result from the raid: Heyward Shepherd, a baggage handler at the Harpers Ferry train station, who had ventured out onto the bridge to look for a watchman who had been driven off by Brown's raiders. He was shot from behind when he by chance encountered the raiders, refused to freeze, and headed back to the station. That a black man was the first casualty of an insurrection

Rebellion is an uprising that resists and is organized against one's government. A rebel is a person who engages in a rebellion. A rebel group is a consciously coordinated group that seeks to gain political control over an entire state or a ...

whose purpose was to aid blacks, and that he disobeyed the raiders, made him a hero of the " Lost Cause" pro-Confederacy movement; a monument

A monument is a type of structure that was explicitly created to commemorate a person or event, or which has become relevant to a social group as a part of their remembrance of historic times or cultural heritage, due to its artistic, historical ...

enshrining this perspective on Shepherd's death was installed in 1931. But in fact, Shepherd was only making "an effort to see what was going on".

The shot and a cry of distress were heard by physician John Starry, who lived across the street from the bridge and walked over to see what was happening. After he saw it was Shepherd and that he could not be saved, Brown let him leave. Instead of going home he started the alarm, having the bell on the Lutheran church rung, sending a messenger to summon help from Charles Town, and then going there himself, after having notified such local men as could be contacted quickly.

The Baltimore & Ohio train

About 1:15 AM the eastbound Baltimore & Ohio express train from Wheeling—one per day in each direction—was to pass through towards Baltimore. The night watchman ran to warn of trouble ahead; the engineer stopped and then backed up the train. Two train crew members who stepped down to reconnoiter were shot at.

Brown boarded the train and talked with passengers for over an hour, not concealing his identity. (Because of his abolitionist work in Kansas, Brown was a "notorious" celebrity; he was well known to any newspaper reader.) Brown then told the train crew they could continue. According to the conductor's telegram they had been detained for five hours, but according to other sources the conductor did not think it prudent to proceed until sunrise, when it could more easily be verified that no damage had been done to the tracks or bridge, and that no one would shoot at them. The passengers were cold on the stopped train, with the engine shut down; normally the temperature would have been around 5 °C (41 °F), but it was "unusually cold". Brown's men had blankets over their shoulders and arms; John Cook reported later having been "chilled through". The passengers were allowed to get off and they "went into the hotel and remained there, in great alarm, for four or five hours".

Several times, Brown later called this incident his "one mistake": "not detaining the train on Sunday night or else permitting it to go on unmolested". Brown scholar Louis DeCaro Jr. called it a "ruinous blunder".

The train departed at dawn, Brown himself, on foot, escorting the train across the bridge. At about 7 AM it arrived at the first station with a working telegraph, Monocacy, near

About 1:15 AM the eastbound Baltimore & Ohio express train from Wheeling—one per day in each direction—was to pass through towards Baltimore. The night watchman ran to warn of trouble ahead; the engineer stopped and then backed up the train. Two train crew members who stepped down to reconnoiter were shot at.

Brown boarded the train and talked with passengers for over an hour, not concealing his identity. (Because of his abolitionist work in Kansas, Brown was a "notorious" celebrity; he was well known to any newspaper reader.) Brown then told the train crew they could continue. According to the conductor's telegram they had been detained for five hours, but according to other sources the conductor did not think it prudent to proceed until sunrise, when it could more easily be verified that no damage had been done to the tracks or bridge, and that no one would shoot at them. The passengers were cold on the stopped train, with the engine shut down; normally the temperature would have been around 5 °C (41 °F), but it was "unusually cold". Brown's men had blankets over their shoulders and arms; John Cook reported later having been "chilled through". The passengers were allowed to get off and they "went into the hotel and remained there, in great alarm, for four or five hours".

Several times, Brown later called this incident his "one mistake": "not detaining the train on Sunday night or else permitting it to go on unmolested". Brown scholar Louis DeCaro Jr. called it a "ruinous blunder".

The train departed at dawn, Brown himself, on foot, escorting the train across the bridge. At about 7 AM it arrived at the first station with a working telegraph, Monocacy, near Frederick, Maryland

Frederick is a city in, and the county seat of, Frederick County, Maryland, United States. Frederick's population was 78,171 people as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, making it the List of municipalities in Maryland, second-largest ...

, about east of Harpers Ferry. The conductor sent a telegram to W. P. Smith, Master of Transportation at B&O headquarters in Baltimore. Smith's reply to the conductor rejected his report as "exaggerated", but by 10:30 AM he had received confirmation from Martinsburg, Virginia, the next station west of Harpers Ferry. No westbound trains were arriving and three eastbound trains were backed up on the Virginia side of the bridge; because of the cut telegraph line the message had to take a long, roundabout route via the other end of the line in Wheeling, and from there back east via Pittsburgh, causing delay. At that point Smith informed the railroad president, John W. Garrett, who sent telegrams to Major General George H. Steuart of the First Light Division, Maryland Volunteers, Virginia Governor Henry A. Wise, U.S. Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

John B. Floyd

John Buchanan Floyd (June 1, 1806 – August 26, 1863) was an American politician who served as the List of governors of Virginia, 31st Governor of Virginia. Under president James Buchanan, he also served as the U.S. Secretary of War from 1857 ...

, and U.S. President James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was the 15th president of the United States, serving from 1857 to 1861. He also served as the United States Secretary of State, secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and represented Pennsylvan ...

.

Armory employees taken hostage

At about this time Armory employees began arriving for work; they were taken as hostages by Brown's party. Reports differ on how many there were, but there were many more than would fit in the small engine house. Brown divided them into two groups, keeping only the ten most important in the engine house; the others were held in a different Armory building. According to the report of Robert E. Lee, the hostages included: * Colonel L. W. Washington, of Jefferson County, Virginia * Mr. J. H. Allstadt, of Jefferson County, Virginia * Mr. Israel Russell, Justice of the Peace, Harpers Ferry * Mr. John Donahue, clerk ofBaltimore and Ohio Railroad

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was the oldest railroads in North America, oldest railroad in the United States and the first steam engine, steam-operated common carrier. Construction of the line began in 1828, and it operated as B&O from 1830 ...

* Mr. Terence Byrne, of Maryland

* Mr. George D. Shope, of Frederick, Maryland

Frederick is a city in, and the county seat of, Frederick County, Maryland, United States. Frederick's population was 78,171 people as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, making it the List of municipalities in Maryland, second-largest ...

* Mr. Benjamin Mills, master armorer eapon maker Harpers Ferry Arsenal

* Mr. A. M. Ball, master machinist, Harpers Ferry Arsenal

* Mr. John E.P. Daingerfield or Dangerfield, paymaster's clerk, Acting Paymaster, Harpers Ferry Arsenal, not to be confused with Dangerfield Newby. Brown told him that by noon he would have 1,500 armed men with him.

* Mr. J. Burd, armorer, Harpers Ferry Arsenal

All save the last were held in the engine house. According to a newspaper report, there were "not less than sixty"; another report says "upwards of seventy". They were detained in "a large building further down the yard". The number of rebels sometimes was inflated because some observers, who had to remain at a distance, thought that the hostages were part of Brown's party.

Armed citizens arrive

As it became known that citizens had been taken hostage by an armed group, men of Harpers Ferry found themselves without arms other than fowling-pieces, which were useless at a distance. Military companies from neighboring towns began to arrive late Monday morning. Among them was Captain John Avis, who would soon be Brown's jailor, who arrived with a company of militia from Charles Town. Also according to the report of Lee, who does not mention Avis, the following volunteer militia groups arrived between 11 AM and his arrival in the evening: * Jefferson Guards and volunteers from Charles Town, under Captain J. W. Rowen * Hamtramck Guards, Jefferson County, Captain V. M. Butler * Shepherdstown troop, Captain Jacob Rienahart * Captain Ephraim G. Alburtis's company, by train from Martinsburg. Most of the militia members were employees of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad shops there. They freed all the hostages except those in the engine house. * Captain B. B. Washington's company fromWinchester

Winchester (, ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city in Hampshire, England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government Districts of England, district, at the western end of the South Downs N ...

* Three companies from Fredericktown, Maryland, under Colonel Shriver

* Companies from Baltimore, under General Charles C. Edgerton, second light brigade

Expecting that thousands of slaves would join him, Brown stayed too long in Harpers Ferry. Harpers Ferry is on a narrow peninsula, almost an island; it is sometimes called "the Island of Virginia". By noon hopes of escape were gone, as his men had lost control of both bridges leading out of town, which because of the terrain were the only practical escape routes. The other bridge, of which not even the pillars remain (the visible pillars are from a later bridge), went east over the Shenandoah River

The Shenandoah River is the principal tributary of the Potomac River, long with two River fork, forks approximately long each,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed August ...

from Harpers Ferry.

The militia companies, under the direction of Colonels R. W. Baylor and John T. Gibson, forced the insurgents to abandon their positions and, since escape was impossible, fortify themselves in "a sturdy stone building", the most defensible in the Armory, the fire engine house, which would be known later as John Brown's Fort. (There were two fire engines

A fire engine or fire truck (also spelled firetruck) is a vehicle, usually a specially designed or modified truck, that functions as a firefighting apparatus. The primary purposes of a fire engine include transporting firefighters and water to ...

; which Greene described as old-fashioned and heavy, plus a hose cart.) They blocked the few windows, used the engines and hose cart to block the heavy doors, and reinforced the doors with rope, making small holes on the walls and through them trading sporadic gunfire with the surrounding militia. Between 2 and 3 there was "a great deal of firing".

During the day four townspeople were killed, including the mayor, who managed the Harpers Ferry station and was a former county sheriff. Eight militiamen were wounded. But the militia, besides the poor quality of their weapons, were disorderly and unreliable. "Most of them ilitiamengot roaring drunk." "A substantial proportion of the militia (along with many of the townspeople) had become a disorganized, drunken, and cowering mob by the time that Colonel Robert E. Lee and the U.S. Marines captured Brown on Tuesday, October 18." The ''Charleston Mercury'' called it a "broad and pathetic farce". According to several reports, Governor Wise was outraged at the poor performance of the local militia.

At one point Brown sent out his son Watson and Aaron Dwight Stevens with a white flag, but Watson was mortally wounded by a shot from a town man, expiring after more than 24 hours of agony, and Stevens was shot and taken prisoner. The raid was clearly failing. One of Brown's men, William H. Leeman, panicked and made an attempt to flee by swimming across the Potomac River, but he was shot and killed while doing so. During the intermittent shooting, another son of Brown, Oliver, was also hit; he died, next to his father, after a brief period. Brown's third participating son, Owen, escaped (with great difficulty) via Pennsylvania to the relative safety of his brother John Jr.'s house in Ashtabula County in northeast

The points of the compass are a set of horizontal, radially arrayed compass directions (or azimuths) used in navigation and cartography. A '' compass rose'' is primarily composed of four cardinal directions—north, east, south, and west—eac ...

Ohio, but he was not part of the Harpers Ferry action; he was guarding the weapons at their base, the Kennedy Farm, just across the river in Maryland.

Buchanan calls out the Marines

Late in the afternoon President Buchanan called out a detachment of U.S. Marines from theWashington Navy Yard

The Washington Navy Yard (WNY) is a ceremonial and administrative center for the United States Navy, located in the federal national capital city of Washington, D.C. (federal District of Columbia). It is the oldest shore establishment / base of ...

, the only federal troops in the immediate area: 81 privates, 11 sergeants, 13 corporals, and 1 bugler, armed with seven howitzer

The howitzer () is an artillery weapon that falls between a cannon (or field gun) and a mortar. It is capable of both low angle fire like a field gun and high angle fire like a mortar, given the distinction between low and high angle fire break ...

s. The Marines left for Harper's Ferry on the regular 3:30 train, arriving about 10 PM. Israel Greene was in charge.

To command them Buchanan ordered Brevet Colonel Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a general officers in the Confederate States Army, Confederate general during the American Civil War, who was appointed the General in Chief of the Armies of the Confederate ...

, conveniently on leave at his home, just across the Potomac in Arlington, Virginia

Arlington County, or simply Arlington, is a County (United States), county in the U.S. state of Virginia. The county is located in Northern Virginia on the southwestern bank of the Potomac River directly across from Washington, D.C., the nati ...

, to "repair" to Harpers Ferry, where he arrived about 10 PM, on a special train. Lee had no uniform readily available, and wore civilian clothes.

Tuesday, October 18

The Marines break through the engine house door

At 6:30 AM Lee began the attack on the engine house. He first offered the role of attacking it to the local militia units, but both commanders declined. Lee then sent Lt. J. E. B. Stuart, serving as a volunteer aide-de-camp, under a white flag of truce to offer John Brown and his men the option of surrendering. Colonel Lee informed Lt. Israel Greene that if Brown did not surrender, he was to direct the Marines to attack the engine house. Stuart walked towards the front of the engine house where he told Brown that his men would be spared if they surrendered. Brown refused and as Stuart walked away, he made a pre-arranged signal—waving his hat—to Lt. Greene and his men standing nearby.

Greene's men then tried to break in using sledgehammers, but their efforts were unsuccessful. He found a ladder nearby, and he and about twelve Marines used it as a battering ram to break down the sturdy doors. Greene was the first through the door and with the assistance of Lewis Washington, identified and singled out John Brown. Greene later recounted what events occurred next:

At 6:30 AM Lee began the attack on the engine house. He first offered the role of attacking it to the local militia units, but both commanders declined. Lee then sent Lt. J. E. B. Stuart, serving as a volunteer aide-de-camp, under a white flag of truce to offer John Brown and his men the option of surrendering. Colonel Lee informed Lt. Israel Greene that if Brown did not surrender, he was to direct the Marines to attack the engine house. Stuart walked towards the front of the engine house where he told Brown that his men would be spared if they surrendered. Brown refused and as Stuart walked away, he made a pre-arranged signal—waving his hat—to Lt. Greene and his men standing nearby.

Greene's men then tried to break in using sledgehammers, but their efforts were unsuccessful. He found a ladder nearby, and he and about twelve Marines used it as a battering ram to break down the sturdy doors. Greene was the first through the door and with the assistance of Lewis Washington, identified and singled out John Brown. Greene later recounted what events occurred next:

Quicker than thought I brought my saber down with all my strength upon rown'shead. He was moving as the blow fell, and I suppose I did not strike him where I intended, for he received a deep saber cut in the back of the neck. He fell senseless on his side, then rolled over on his back. He had in his hand a short Sharpe's cavalry carbine. I think he had just fired as I reached Colonel Washington, for the Marine who followed me into the aperture made by the ladder received a bullet in the abdomen, from which he died in a few minutes. The shot might have been fired by someone else in the insurgent party, but I think it was from Brown. Instinctively as Brown fell I gave him a saber thrust in the left breast. The sword I carried was a light uniform weapon, and, either not having a point or striking something hard in Brown's accouterments, did not penetrate. The blade bent double.Two of the raiders were killed, and the rest taken prisoner. Brown was wounded before and after his surrender. The hostages were freed and the assault was over. It lasted three minutes. According to one marine, the raiders presented a sad appearance: Colonel Lee and Jeb Stuart searched the surrounding country for fugitives who had participated in the attack. Few of Brown's associates escaped, and among the five who did, some were sheltered by abolitionists in the North, including

William Still

William Still (October 7, 1819 – July 14, 1902) was an African-American abolitionist based in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He was a conductor of the Underground Railroad and was responsible for aiding and assisting at least 649 slaves to freedom ...

.Simmons, William J., and Henry McNeal Turner. ''Men of Mark: Eminent, Progressive and Rising''. G. M. Rowell & Company, 1887. p. 160

Interviews

All the bodies were taken out and laid on the ground in front. "A detail of reene'smen" carried Brown and Edwin Coppock, the only other white survivor of the attack on the engine house, to the adjacent office of the paymaster, where they lay on the floor for over a day. Until they went with the group to the Charles Town jail on Wednesday, there is no record of the location of the two surviving captured black raiders, Shields Green and John Anthony Copeland, who were also the only two survivors of the engine house with no injuries. Green attempted unsuccessfully to disguise himself as one of the enslaved of Colonel Washington being liberated. From this point forward, Brown would endlessly be interrogated by soldiers, politicians, lawyers, reporters, citizens, and preachers. He welcomed the attention. The first to interview him was Virginia congressman Alexander Boteler, who rode over from his home in nearby Shepherd's Town (nowShepherdstown, West Virginia

Shepherdstown is a town in Jefferson County, West Virginia, United States, located in the lower Shenandoah Valley along the Potomac River. Home to Shepherd University, the town's population was 1,531 at the time of the 2020 census. The town wa ...

), and was present when Brown was carried out of the engine house, and told a Catholic priest to leave. Five people, in addition to several reporters, came almost immediately to Harpers Ferry specifically to interview Brown. He was interviewed at length as he lay there over 24 hours; he had been without food and sleep for over 48 hours. ("Brown carried no provisions on the expedition, as if God would rain down manna from the skies as He had done for the Israelites in the wilderness.") The first interviewers after Boteler were Virginia Governor Wise, his attorney Andrew Hunter, who was also the leading attorney in Jefferson County, and Robert Ould, United States Attorney

United States attorneys are officials of the U.S. Department of Justice who serve as the chief federal law enforcement officers in each of the 94 U.S. federal judicial districts. Each U.S. attorney serves as the United States' chief federal ...

for the District of Columbia, sent by President Buchanan. Governor Wise having left—he set up a base in a Harpers Ferry hotel—Brown was then interviewed by Senator James M. Mason, from Winchester, Virginia

Winchester is the northwesternmost Administrative divisions of Virginia#Independent cities, independent city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Virginia, United States. It is the county seat of Frederick County, Virginia, Frederi ...

, and Representatives Charles J. Faulkner, from Martinsville, Virginia

Martinsville is an Political subdivisions of Virginia#Independent cities, independent city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population was 13, ...

, and Copperhead Clement Vallandigham

Clement Laird Vallandigham ( ; July 29, 1820 – June 17, 1871) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the leader of the Copperhead (politics), Copperhead faction of Opposition to the American Civil War, anti-war History of the Unit ...

, from Ohio. (Brown lived for years in Ohio, and both Watson and Owen Brown were born there.) Vallandingham was on his way from Washington to Ohio via the B&O Railroad, which of course would take him through Harpers Ferry. In Baltimore he was informed about the raid.

Up until this point, most public opinion in the North and West had seen Brown as a fanatic, a crazy man, attacking Virginia with only 22 men, of whom 10 were killed immediately, and 7 others would soon be hanged, as well as 5 deaths and 9 injuries among the Marines and local population. With the newspaper reports of these interviews, followed by Brown's widely reported words at his trial, the public perception of Brown changed suddenly and dramatically. According to Henry David Thoreau, "I know of nothing so miraculous in our history. Years were not required for a revolution of public opinion; days, nay hours, produced marked changes."

Governor Wise, though firmly in favor of Brown's execution, called him "the gamest man I ever saw". Boteler also spoke well of him. Representative Vallandingham, described later by Thoreau as an enemy of Brown, made the following comment after reaching Ohio:

Like Mason (see below), Vallandingham thought Brown could not possibly have thought of and planned the raid by himself.

=Interview by Governor Wise

= Virginia Governor Wise, with a force of ninety men, who were disappointed that the action was already over, arrived from Richmond about midday Tuesday. "Learning how quickly the Marines had crushed the raid, Wise 'boiled over', and said he would rather have lost both legs and both arms from his shoulders and hips than such a disgrace should have been cast upon it irginia, since Brown held off all the local militia That fourteen white men and five negroes should have captured the government works and all Harper's Ferry, and have found It possible to retain them forven

Venezuela, officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many islands and islets in the Caribbean Sea. It comprises an area of , and its popul ...

one hour, while Col. Lee, with twelve marines, settled the matter in ten minutes."

Wise interviewed Brown while he, along with Stevens, was lying on the floor of the paymaster's office at the Arsenal, where they would remain until, over thirty hours later, they were moved to the Jefferson County jail. Brown, despite his wounds, was "courteous and afable". Andrew Hunter took notes, but there is no transcript of this interview. One exchange was as follows:

The paymaster's clerk at the Arsenal, Captain J.E.P. Dangerfield (not to be confused with Dangerfield Newby), was taken hostage when he arrived for work. He was present at this interview, and remarked that: "Governor Wise was astonished at the answers he received from Brown." Back in Richmond, on Saturday, October 22, in a speech widely reported in the newspapers, Wise himself stated:

Wise also reported the opinion of Lewis Washington, in a passage called "well known" in 1874: "Colonel Washington says that he, Brown, was the coolest and firmest man he ever saw in defying danger and death. With one son dead by his side, and another shot through, he felt the pulse of his dying son with one hand and held his rifle with the other, and commanded his men with the utmost composure, encouraging them to be firm, and to sell their lives as dearly as they could."

Wise left for his hotel in Harpers Ferry about dinnertime Tuesday.

Wise interviewed Brown while he, along with Stevens, was lying on the floor of the paymaster's office at the Arsenal, where they would remain until, over thirty hours later, they were moved to the Jefferson County jail. Brown, despite his wounds, was "courteous and afable". Andrew Hunter took notes, but there is no transcript of this interview. One exchange was as follows:

The paymaster's clerk at the Arsenal, Captain J.E.P. Dangerfield (not to be confused with Dangerfield Newby), was taken hostage when he arrived for work. He was present at this interview, and remarked that: "Governor Wise was astonished at the answers he received from Brown." Back in Richmond, on Saturday, October 22, in a speech widely reported in the newspapers, Wise himself stated:

Wise also reported the opinion of Lewis Washington, in a passage called "well known" in 1874: "Colonel Washington says that he, Brown, was the coolest and firmest man he ever saw in defying danger and death. With one son dead by his side, and another shot through, he felt the pulse of his dying son with one hand and held his rifle with the other, and commanded his men with the utmost composure, encouraging them to be firm, and to sell their lives as dearly as they could."

Wise left for his hotel in Harpers Ferry about dinnertime Tuesday.

=Interview by Senator Mason and two Representatives

= Virginia Senator James M. Mason lived in nearby Winchester, and would later chair the Select Senate committee investigating the raid. He also came immediately to Harpers Ferry to interview Brown. CongressmenClement Vallandigham

Clement Laird Vallandigham ( ; July 29, 1820 – June 17, 1871) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the leader of the Copperhead (politics), Copperhead faction of Opposition to the American Civil War, anti-war History of the Unit ...

of Ohio, who called Brown "sincere, earnest, practical", Charles J. Faulkner of Virginia, Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a general officers in the Confederate States Army, Confederate general during the American Civil War, who was appointed the General in Chief of the Armies of the Confederate ...

, and "several other distinguished gentlemen" were also present. The audience averaged 10 to 12. Lee said that he would exclude all visitors from the room if the wounded men were annoyed or pained by them, but Brown said he was by no means annoyed; on the contrary, he was glad to be able to make himself and his motives "clearly understood".

A reporter- stenographer of the ''New York Herald'' produced a "verbatim" transcript of the interview, although it started before he arrived, shortly after 2 PM. Published in full or part in many newspapers, it is the most complete public statement we have of Brown about the raid.

Wednesday, October 19

Lee and the Marines, except for Greene, left Harper's Ferry for Washington on the 1:15 AM train, the only express east. He finished his report and sent it to the War Department that day. He made a synopsis of the events that took place atHarpers Ferry

Harpers Ferry is a historic town in Jefferson County, West Virginia, United States. The population was 269 at the 2020 United States census. Situated at the confluence of the Potomac River, Potomac and Shenandoah River, Shenandoah Rivers in the ...

. According to Lee's report: "the plan aiding the Harpers Ferry Arsenalwas the attempt of a fanatic or madman." Lee also believed that the blacks in the raid were forced by Brown. "The blacks, whom he ohn Brownforced from their homes in this neighborhood, as far as I could learn, gave him no voluntary assistance." Lee attributed John Brown's "temporary success" to the panic and confusion and to "magnifying" the number of participants involved in the raid. Lee said that he was sending the Marines back to the Navy Yard.

"Governor Wise is still ednesdayhere busily engaged in a personal investigation of the whole affair, and seems to be using every means for bringing to retribution all the participators in it."

A holograph copy of Brown's Provisional Constitution, held by the Yale University Library

The Yale University Library is the library system of Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. Originating in 1701 with the gift of several dozen books to a new “Collegiate School," the library's collection now contains approximately 14.9 m ...

, bears the handwritten annotation: "Handed to Gov. Wise by John Brown on Wed Oct 19/59 before he was removed from the U.S. grounds at Harpers Ferry & while he lay wounded on his cot."

On Wednesday evening the prisoners were moved by train from Harpers Ferry to Charles Town, where they were placed in the Jefferson County jail, "a very pretty jail, ...like a handsome private residence", the press reported. Governor Wise and Andrew Hunter, his attorney, accompanied them. The Jefferson County jail was "a meek-looking edifice, hich

Ij () is a village in Golabar Rural District of the Central District in Ijrud County, Zanjan province, Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq ...

must have been a respectable private residence". Brown wrote his family: "I am supplied with almost everything I could desire to make me comfortable". According to the ''New York Tribunes reporter on the scene:

Trial and execution

Brown was hastily processed by the legal system. He was charged by a

Brown was hastily processed by the legal system. He was charged by a grand jury

A grand jury is a jury empowered by law to conduct legal proceedings, investigate potential criminal conduct, and determine whether criminal charges should be brought. A grand jury may subpoena physical evidence or a person to testify. A grand ju ...

with treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state (polity), state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to Coup d'état, overthrow its government, spy ...

against the Commonwealth of Virginia, murder, and inciting a slave insurrection. A jury found him guilty of all charges; he was sentenced to death on November 2, and after a legally required delay of 30 days he was hanged on December 2. The execution was witnessed by actor John Wilkes Booth

John Wilkes Booth (May 10, 1838April 26, 1865) was an American stage actor who Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, assassinated United States president Abraham Lincoln at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C., on April 14, 1865. A member of the p ...

, who later assassinated President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

. At the hanging and en route to it, authorities prevented spectators from getting close enough to Brown to hear a final speech. He wrote his last words on a scrap of paper given to his jailer Capt. John Avis, whose treatment Brown spoke well of in his letters:

I John Brown am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty, land: will never be purged away; but with Blood. I had as I now think: vainly flattered myself that without very much bloodshed; it might be done.Four other raiders were executed on December 16 and two more on March 16, 1860. In his last speech, at his sentencing, he said to the court:

d I so interfered in behalf of the rich, the powerful, the intelligent, the so-called great, or in behalf of any of their friends, either father, mother, brother, sister, wife, or children, or any of that class, and suffered and sacrificed what I have in this interference, it would have been all right; and every man in this court would have deemed it an act worthy of reward rather than punishment.Southerners had a mixed attitude towards their slaves. Many Southern whites lived in constant fear of another slave insurrection; paradoxically, Southern whites also claimed that slaves were content in bondage, blaming slave unrest on Northern

abolitionists

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was France in 1315, but it was later used in its colonies. T ...

. After the raid Southerners initially lived in fear of slave uprisings and invasion by armed abolitionists. The South's reaction entered the second phase at around the time of Brown's execution. Southerners were relieved that no slaves had volunteered to help Brown, as they were incorrectly told by Governor Wise and others see ( John Brown's raiders), and felt vindicated in their claims that slaves were content. After Northerners had expressed admiration for Brown's motives, with some treating him as a martyr, Southern opinion evolved into what James M. McPherson called "unreasoning fury".

The first Northern reaction among antislavery advocates to Brown's raid was one of baffled reproach. Abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison

William Lloyd Garrison (December , 1805 – May 24, 1879) was an Abolitionism in the United States, American abolitionist, journalist, and reformism (historical), social reformer. He is best known for his widely read anti-slavery newspaper ''The ...

, "committed to the methods of nonviolent moral suasion", called the raid "misguided, wild, and apparently insane". But through the trial and his execution, Brown was transformed into a martyr

A martyr (, ''mártys'', 'witness' Word stem, stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an external party. In ...

. Henry David Thoreau

Henry David Thoreau (born David Henry Thoreau; July 12, 1817May 6, 1862) was an American naturalist, essayist, poet, and philosopher. A leading Transcendentalism, transcendentalist, he is best known for his book ''Walden'', a reflection upon sim ...

, in '' A Plea for Captain John Brown'', said, "I think that for once the Sharps' rifles and the revolvers were employed in a righteous cause. The tools were in the hands of one who could use them," and said of Brown, "He has a spark of divinity in him." To the South, Brown was a murderer who wanted to deprive them of their property (slaves). The North "has sanctioned and applauded theft, murder, and treason", said '' De Bow's Review''. According to the '' Richmond Enquirer'', the South's reaction was "horror and indignation". But this was not the entire story. Kent Blaser writes that "there was surprisingly little fear or panic over race insurrection in North Carolina.... Much was made of the refusal of slaves to join in the insurrection".

The Republican Party, faced with charges that their opposition to slavery inspired Brown's raid, distanced themselves from Brown by instead suggesting that it was instead precedented by Democrats' support for filibusters such as William Walker and Narciso López, arguing that their attempts to overthrow foreign governments and their receipt of support from Democratic politicians had inspired Brown to attempt a similar action.

Consequences of Brown's raid

John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry was the last major event that led to theCivil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

(see sidebar, above). According to the ''Richmond Enquirer'', "The Harper's Ferry invasion has advanced the cause of Disunion, more than any other event that has happened since the formation of the Government; it has rallied to that standard men who formerly looked upon it with horror; it has revived, with ten fold 'sic''strength the desire of a Southern Confederacy."

His well-publicized raid, a complete failure in the short term, contributed to Lincoln's election in 1860, and Jefferson Davis

Jefferson F. Davis (June 3, 1808December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the only President of the Confederate States of America, president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the Unite ...

"cited the attack as grounds for Southerners to leave the Union, 'even if it rushes us into a sea of blood.'" Seven Southern states seceded to form the Confederacy. The Civil War followed, and four more states seceded; Brown had seemed to be calling for war in his last message before his execution: "the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away, but with Blood."

However, David S. Reynolds wrote, "The raid on Harpers Ferry helped dislodge slavery, but not in the way Brown had foreseen. It did not ignite slave uprisings throughout the South. Instead, it had an immense impact because of the way Brown ''behaved'' during and after it, and the way it was ''perceived'' by key figures on both sides of the slavery divide. The raid did not cause the storm. John Brown and the reaction to him did."

Brown's raid, trial, and execution energized both the abolitionists in the North and the supporters of slavery in the South, and it brought a flurry of political organizing. Public meetings in support of Brown, sometimes also raising money for his family, were held across the North. "These meetings gave the era's most illustrious thinkers and activists an opportunity to renew their assault on slavery". It reinforced Southern sentiment for secession.

Casualties

John Brown's raiders

Counting John Brown, there were 22 raiders, 15 white and 7 black. 10 were killed during the raid, 7 were tried and executed afterwards, and 5 escaped. In addition, Brown was assisted by at least two local enslaved people; one was killed and the other died in jail.Other casualties, civilian and military

* Killed ** Heyward Shepherd, a free African-American B&O baggage master. He was buried in the African-American cemetery on Rt. 11 inWinchester, Virginia

Winchester is the northwesternmost Administrative divisions of Virginia#Independent cities, independent city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Virginia, United States. It is the county seat of Frederick County, Virginia, Frederi ...

. In 1932 no one could find his grave.

** Private Luke Quinn, U.S. Marines, was killed during the storming of the engine house. He was buried in Harpers Ferry Catholic Cemetery on Rte. 340.

** Thomas Boerly, townsperson. According to Richard Hinton, "Mr. Burleigh" was killed by Shields Green.

** George W. Turner, townsperson.

** Fontaine Beckham, Harpers Ferry mayor, B&O stationmaster, former sheriff. Mayor Beckham's ''Will Book'' called for the liberation of Isaac Gilbert, Gilbert's wife, and their three children upon his death. When Edwin Coppock murdered Beckham the enslaved family was thus freed.

** A slave owned by Colonel Washington was killed.

** A slave owned by hostage John Allstad was killed. Both slaves voluntarily joined Brown's raiders. One was killed trying to escape across the Potomac River; the other was wounded and later died in the Charles Town jail.

* Wounded but survived

** Private Matthew Ruppert, U. S. Marines, was shot in the face during the storming of the engine house.

** Edward McCabe, Harpers Ferry laborer.

** Samuel C. Young, Charles Town militia. As he was "permanently disabled by a wound received in defence of Southern institutions" (slavery), a pamphlet was published to raise money for him.

** Martinsburg, Virginia, militia:

*** George Murphy

*** George Richardson

*** G. N. Hammond

*** Evan Dorsey

*** Nelson Hooper

*** George Woollett

Legacy

Many of John Brown's homes are today small museums. The only major street named for John Brown is in Port-au-Prince, Haiti (where there is also an AvenueCharles Sumner