Jewish problem on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Jewish question was a wide-ranging debate in 19th- and 20th-century Europe that pertained to the appropriate status and treatment of

excerpt

*Katz, Jacob. ''Out of the Ghetto: The Social Background of Jewish Emancipation, 1770-1870''. Cambridge: Harvard University Press 1973. *Kovach, Thomas. "The Elusiveness of Tolerance: The" Jewish Question" from Lessing to the Napoleonic Wars." ''Eighteenth-Century Studies'' 32.1 (1998): 127-128. * Roudinesco, Elisabeth (2013

''Returning to the Jewish Question''

London, Polity Press, p. 280 * Wolf, Lucien (1919

"Notes on the Diplomatic History of the Jewish Question"

Jewish Historical Society of England * The Jewish cause: an introduction to a different Israeli history – the subject's impact during the Holocaust * * Smith, Steven B. ''Spinoza, Liberalism, and the Question of Jewish Identity''. New Haven: Yale University Press 1997.

Israeli Foreign Policy and the Jewish Question

{{DEFAULTSORT:Jewish Question National questions Jewish political status Incitement to genocide of Jews The Holocaust Adolf Hitler Karl Marx Debates about social issues Minority rights

Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

. The debate, which was similar to other " national questions", dealt with the civil, legal, national, and political status of Jews as a minority within society, particularly in Europe during the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries.

The debate began with Jewish emancipation

Jewish emancipation was the process in various nations in Europe of eliminating Jewish disabilities, to which European Jews were then subject, and the recognition of Jews as entitled to equality and citizenship rights. It included efforts withi ...

in western and central European societies during the Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment (also the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment) was a Europe, European Intellect, intellectual and Philosophy, philosophical movement active from the late 17th to early 19th century. Chiefly valuing knowledge gained th ...

and after the French Revolution. The debate's issues included legal and economic Jewish disabilities (such as Jewish quota

A Jewish quota was a discriminatory racial quota designed to limit or deny access for Jews to various institutions. Such quotas were widespread in the 19th and 20th centuries in developed countries and frequently present in higher education, o ...

s and segregation Segregation may refer to:

Separation of people

* Geographical segregation, rates of two or more populations which are not homogenous throughout a defined space

* School segregation

* Housing segregation

* Racial segregation, separation of human ...

), Jewish assimilation

Jewish assimilation (, ''hitbolelut'') refers either to the gradual cultural assimilation and social integration of Jews in their surrounding culture or to an ideological program in the age of emancipation promoting conformity as a potential so ...

, and Jewish Enlightenment

The ''Haskalah'' (; literally, "wisdom", "erudition" or "education"), often termed the Jewish Enlightenment, was an intellectual movement among the Jews of Central and Eastern Europe, with a certain influence on those in Western Europe and th ...

.

The expression has been used by antisemitic

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

movements from the 1880s onwards, culminating in the Holocaust

The Holocaust (), known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as the (), was the genocide of History of the Jews in Europe, European Jews during World War II. From 1941 to 1945, Nazi Germany and Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy ...

(1941–45), specifically a Nazi plan called the " Final Solution to the Jewish Question". Similarly, the expression was used by proponents for, and opponents of, the establishment of an autonomous Jewish homeland or a sovereign Jewish state

In world politics, Jewish state is a characterization of Israel as the nation-state and sovereign homeland for the Jewish people.

Overview

Modern Israel came into existence on 14 May 1948 as a polity to serve as the homeland for the Jewi ...

, leading to the state of Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

in 1948.

History of "the Jewish question"

The term "Jewish question" was first used in Great Britain around 1750 when the expression was used during the debates related to the Jewish Naturalisation Act 1753. Freely available at According to Holocaust scholarLucy Dawidowicz

Lucy Dawidowicz ( Schildkret; June 16, 1915 – December 5, 1990) was an American historian and writer. She wrote books about modern Jewish history, in particular, about the Holocaust.

Life

Dawidowicz was born in New York City as Lucy Schildkre ...

, the term "Jewish Question", as introduced in western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's extent varies depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the Western half of the ancient Mediterranean ...

, was a neutral expression for the negative attitude toward the apparent and persistent singularity of the Jews as a people against the background of the rising political nationalism and new nation-state

A nation state, or nation-state, is a political entity in which the state (a centralized political organization ruling over a population within a territory) and the nation (a community based on a common identity) are (broadly or ideally) con ...

s. Dawidowicz writes that "the histories of Jewish emancipation and of European antisemitism are replete with proffered 'solutions to the Jewish question.

The question was next discussed in France () after the French Revolution in 1789. It was discussed in Germany in 1843 via Bruno Bauer

Bruno Bauer (; ; 6 September 180913 April 1882) was a German philosopher and theologian. As a student of G. W. F. Hegel, Bauer was a radical Rationalist in philosophy, politics and Biblical criticism. Bauer investigated the sources of the New T ...

's treatise (). He argued that Jews could achieve political emancipation only if they let go their religious consciousness, as he proposed that political emancipation required a secular state

is an idea pertaining to secularity, whereby a state is or purports to be officially neutral in matters of religion, supporting neither religion nor irreligion. A secular state claims to treat all its citizens equally regardless of relig ...

. Bauer's conclusions were disputed by Karl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

in his essay '' Zur Judenfrage'', in which he argued that Jewish political emancipation was possible because a secular state presupposes and sustains the private religious life of its citizens, while still maintaining the abolition of capitalism would bring about the end of Judaism: "The existence of religion is not in contradiction to the perfection of the state... oweveronce society has succeeded in abolishing the empirical essence of Judaism – huckstering and its preconditions – the Jew will have become impossible, because his consciousness no longer has an object."

According to Otto Dov Kulka

Otto Dov Kulka (''Ôttô Dov Qûlqā''; 16 January 1933 in Nový Hrozenkov, Czechoslovakia – 29 January 2021 in Jerusalem; ) was an Israeli historian, professor emeritus of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. His primary areas of specializatio ...

of Hebrew University

The Hebrew University of Jerusalem (HUJI; ) is an Israeli public research university based in Jerusalem. Co-founded by Albert Einstein and Chaim Weizmann in July 1918, the public university officially opened on 1 April 1925. It is the second-ol ...

, the term became widespread in the 19th century when it was used in discussions about Jewish emancipation

Jewish emancipation was the process in various nations in Europe of eliminating Jewish disabilities, to which European Jews were then subject, and the recognition of Jews as entitled to equality and citizenship rights. It included efforts withi ...

in Germany (). In the 19th century hundreds of tractates, pamphlets, newspaper articles and books were written on the subject, with many offering such solutions as resettlement, deportation, or assimilation of the Jewish population. Similarly, hundreds of works were written opposing these solutions and offering instead solutions such as re-integration and education. This debate however, could not decide whether the problem of the Jewish question had more to do with the problems posed by the German Jews

The history of the Jews in Germany goes back at least to the year 321 CE, and continued through the Early Middle Ages (5th to 10th centuries CE) and High Middle Ages (c. 1000–1299 CE) when Jewish immigrants founded the Ashkenazi Jewish commu ...

' opponents or vice versa: the problem posed by the existence of the German Jews to their opponents.

From around 1860, the term was used with an increasingly antisemitic tendency: Jews were described under this term as a stumbling block to the identity and cohesion of the German nation and as enemies within the Germans' own country. Antisemites such as Wilhelm Marr

Friedrich Wilhelm Adolph Marr (November 16, 1819 – July 17, 1904) was a German journalist and politician, who popularized the term "antisemitism" (1881).

Life

Marr was born in Magdeburg as the only son of an actor and stage director. He went t ...

, Karl Eugen Dühring, Theodor Fritsch

Theodor Fritsch (born Emil Theodor Fritsche; 28 October 1852 – 8 September 1933) was a German publisher and journalist. His antisemitic writings did much to influence popular German opinion against Jews in the late 19th and early 20th centur ...

, Houston Stewart Chamberlain

Houston Stewart Chamberlain (; 9 September 1855 – 9 January 1927) was a British-German-French philosopher who wrote works about political philosophy and natural science. His writing promoted German ethnonationalism, antisemitism, scientific r ...

, Paul de Lagarde

Paul Anton de Lagarde (2 November 1827 – 22 December 1891) was a German biblical scholar and orientalist, sometimes regarded as one of the greatest orientalists of the 19th century. Lagarde's anti-Semitism, anti-Slavism, and aversion to tradit ...

and others declared it a racial problem insoluble through integration. They stressed this in order to strengthen their demands to "de-jewify" the press, education, culture, state and economy. They also proposed to condemn inter-marriage between Jews and non-Jews. They used this term to oust the Jews from their supposedly socially dominant positions.

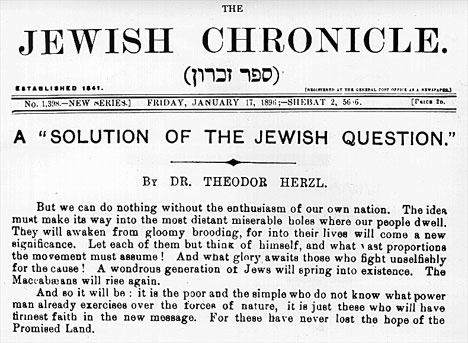

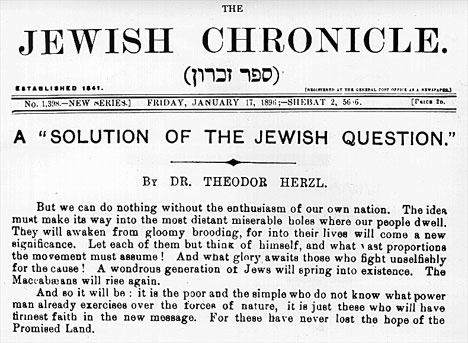

The topic was also taken up by Jews themselves. Theodor Herzl

Theodor Herzl (2 May 1860 – 3 July 1904) was an Austria-Hungary, Austro-Hungarian Jewish journalist and lawyer who was the father of Types of Zionism, modern political Zionism. Herzl formed the World Zionist Organization, Zionist Organizat ...

's 1896 treatise advocates Zionism

Zionism is an Ethnic nationalism, ethnocultural nationalist movement that emerged in History of Europe#From revolution to imperialism (1789–1914), Europe in the late 19th century that aimed to establish and maintain a national home for the ...

as a "modern solution for the Jewish question" by creating an independent Jewish state, preferably in Ottoman-controlled Palestine. The 1934 science fiction novel by the German rabbi imagines a refuge for Jews on the moon.

The most infamous use of this expression was by the Nazi

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During H ...

s in the early- and mid-twentieth century. They implemented what they called their "Final Solution

The Final Solution or the Final Solution to the Jewish Question was a plan orchestrated by Nazi Germany during World War II for the genocide of individuals they defined as Jews. The "Final Solution to the Jewish question" was the official ...

to the Jewish question" through the Holocaust

The Holocaust (), known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as the (), was the genocide of History of the Jews in Europe, European Jews during World War II. From 1941 to 1945, Nazi Germany and Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, when they attempted to exterminate Jews in Europe.

Bruno Bauer – ''The Jewish Question''

In his book '' The Jewish Question'' (1843), Bauer argued that Jews could only achieve political emancipation if they relinquished their particular religious consciousness. He believed that political emancipation required asecular state

is an idea pertaining to secularity, whereby a state is or purports to be officially neutral in matters of religion, supporting neither religion nor irreligion. A secular state claims to treat all its citizens equally regardless of relig ...

, and such a state did not leave any "space" for social identities such as religion

Religion is a range of social system, social-cultural systems, including designated religious behaviour, behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, religious text, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics in religion, ethics, or ...

. According to Bauer, such religious demands were incompatible with the idea of the " Rights of Man". True political emancipation, for Bauer, required the abolition of religion.

Karl Marx – ''On the Jewish Question''

Karl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

replied to Bauer in his 1844 essay ''On the Jewish Question

"On the Jewish Question" is a response by Karl Marx to then-current debates over the Jewish question. Marx's father had converted to Lutheran Christianity, and his wife and children were baptized in 1825 and 1824, respectively. Marx wrote the pie ...

''. Marx repudiated Bauer's view that the nature of the Jewish religion prevented assimilation by Jews. Instead, Marx attacked Bauer's very formulation of the question from "can the Jews become politically emancipated?" as fundamentally masking the nature of political emancipation itself.

Marx used Bauer's essay as an occasion for his own analysis of liberal rights. Marx argued that Bauer was mistaken in his assumption that in a "secular state

is an idea pertaining to secularity, whereby a state is or purports to be officially neutral in matters of religion, supporting neither religion nor irreligion. A secular state claims to treat all its citizens equally regardless of relig ...

", religion would no longer play a prominent role in social life. As an example, he referred to the pervasiveness of religion in the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

, which, unlike Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

, had no state religion. In Marx's analysis, the "secular state" was not opposed to religion, but rather assumed it. The removal of religious or property qualifications for citizenship did not mean the abolition of religion or property, but rather naturalized both and introduced a way of regarding individuals in abstraction from them.Marx 1844: On this note Marx moved beyond the question of religious freedom to his real concern with Bauer's analysis of "political emancipation." Marx concluded that while individuals can be 'politically' free in a secular state, they were still bound to material constraints on freedom by economic inequality, an assumption that would later form the basis of his critiques of capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

.

After Marx

Werner Sombart Werner may refer to:

People

* Werner (name), origin of the name and people with this name as surname and given name

Fictional characters

* Werner (comics), a German comic book character

* Werner Von Croy, a fictional character in the ''Tomb Rai ...

praised Jews for their capitalism and presented the seventeenth–eighteenth century court Jew

In early modern Europe, particularly in Germany, a court Jew (, ) or court factor (, ) was a Jewish banker who handled the finances of, or lent money to, royalty and nobility. In return for their services, court Jews gained social privileges, inc ...

s as integrated and a model for integration. By the turn of the twentieth century, the debate was still widely discussed. The Dreyfus Affair in France, believed to be evidence of anti-semitism, increased the prominence of this issue. Theodor Herzl

Theodor Herzl (2 May 1860 – 3 July 1904) was an Austria-Hungary, Austro-Hungarian Jewish journalist and lawyer who was the father of Types of Zionism, modern political Zionism. Herzl formed the World Zionist Organization, Zionist Organizat ...

proposed the advancement of a separate Jewish state

In world politics, Jewish state is a characterization of Israel as the nation-state and sovereign homeland for the Jewish people.

Overview

Modern Israel came into existence on 14 May 1948 as a polity to serve as the homeland for the Jewi ...

and the Zionist

Zionism is an Ethnic nationalism, ethnocultural nationalist movement that emerged in History of Europe#From revolution to imperialism (1789–1914), Europe in the late 19th century that aimed to establish and maintain a national home for the ...

cause.

Between 1880 and 1920, millions of Jews created their own solution for the pogrom

A pogrom is a violent riot incited with the aim of Massacre, massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe late 19th- and early 20th-century Anti-Jewis ...

s of eastern Europe by emigration to other places, primarily the United States and western Europe.

The Nazi "Final Solution"

InNazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

, the term ''Jewish Question'' (in ) referred to the belief that the existence of Jews in Germany posed a problem for the state. In 1933 two Nazi theorists, Johann von Leers

Omar Amin (born Johann Jakob von Leers; 25 January 19025 March 1965) was an '' Alter Kämpfer'' and an honorary ''Sturmbannführer'' in the ''Waffen-SS'' in Nazi Germany, where he was also a professor known for his anti-Jewish polemics. He was ...

and Achim Gercke, both proposed the idea that the Jewish Question could be solved by resettling Jews in Madagascar, or somewhere else in Africa or South America. They also discussed the pros and cons of supporting the German Zionists. Von Leers asserted that establishing a Jewish homeland in Mandatory Palestine

Mandatory Palestine was a British Empire, British geopolitical entity that existed between 1920 and 1948 in the Palestine (region), region of Palestine, and after 1922, under the terms of the League of Nations's Mandate for Palestine.

After ...

would create humanitarian and political problems for the region.

Upon achieving power in 1933, Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

and the Nazi state began to implement increasingly severe legislation that was aimed at segregating and ultimately removing Jews from Germany and (eventually) all of Europe. The next stage was the persecution of the Jews and the stripping of their citizenship through the 1935 Nuremberg Laws

The Nuremberg Laws (, ) were antisemitic and racist laws that were enacted in Nazi Germany on 15 September 1935, at a special meeting of the Reichstag convened during the annual Nuremberg Rally of the Nazi Party. The two laws were the Law ...

. Starting with 1938 Kristallnacht

( ) or the Night of Broken Glass, also called the November pogrom(s) (, ), was a pogrom against Jews carried out by the Nazi Party's (SA) and (SS) paramilitary forces along with some participation from the Hitler Youth and German civilia ...

pogrom and later, during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, it became state-sponsored internment in concentration camps

A concentration camp is a prison or other facility used for the internment of political prisoners or politically targeted demographics, such as members of national or ethnic minority groups, on the grounds of national security, or for exploit ...

. Finally the government implemented the systematic extermination of the Jewish people (The Holocaust

The Holocaust (), known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as the (), was the genocide of History of the Jews in Europe, European Jews during World War II. From 1941 to 1945, Nazi Germany and Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy ...

), which took place as the so-called ''Final Solution

The Final Solution or the Final Solution to the Jewish Question was a plan orchestrated by Nazi Germany during World War II for the genocide of individuals they defined as Jews. The "Final Solution to the Jewish question" was the official ...

to the Jewish Question''.

Nazi propaganda

Propaganda was a tool of the Nazi Party in Germany from its earliest days to the end of the regime in May 1945 at the end of World War II. As the party gained power, the scope and efficacy of its propaganda grew and permeated an increasing amou ...

was produced in order to manipulate the public, the most notable examples of which were based on the writings of people such as Eugen Fischer

Eugen Fischer (5 July 1874 – 9 July 1967) was a German professor of medicine, anthropology, and eugenics, and a member of the Nazi Party. He served as director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics, ...

, Fritz Lenz

Fritz Gottlieb Karl Lenz (9 March 1887 in Pflugrade, Pomerania – 6 July 1976 in Göttingen, Lower Saxony) was a German geneticist, member of the Nazi Party,

and Erwin Baur

Erwin Baur (16 April 1875, in Ichenheim, Grand Duchy of Baden – 2 December 1933) was a German geneticist and botanist. Baur worked primarily on plant genetics. He was director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Breeding Research (then in Mü ...

in ''Foundations of Human Heredity Teaching and Racial Hygiene''. The work (''Allowing the Destruction of Life Unworthy of Living'') by Karl Binding and Alfred Hoche and the pseudo-scholarship that was promoted by Gerhard Kittel also played a role. In occupied France

The Military Administration in France (; ) was an interim occupation authority established by Nazi Germany during World War II to administer the occupied zone in areas of northern and western France. This so-called ' was established in June 19 ...

, the collaborationist regime established its own Institute for studying the Jewish Questions.

In the United States

According to historians Ronald J. Jensen and Stuart Knee, by the 1870s Russian-American relations were strained by the mistreatment of American Jewish visitors in Russia. President Ulysses S. Grant responded to American Jewish requests for action to protect visitors. By the 1880s, the outbreak of anti-Semitic pogroms in Russia and consequent mass emigration of Jews to New York made relations worse. After 1880, escalating pogroms alienated both elite opinion and public opinion in the U.S. In 1903, theKishinev pogrom

The Kishinev pogrom or Kishinev massacre was an anti-Jewish riot that took place in Kishinev (modern Chișinău, Moldova), then the capital of the Bessarabia Governorate in the Russian Empire, on . During the pogrom, which began on Easter Day, ...

killed 47 Jews, injured 400, and left 10,000 homeless and dependent on relief. American Jews began large-scale organized financial help and assisted in emigration from Russia. More violence in Russia led in 1911 to the United States repealing an 1832 commercial treaty.

In the 1920s, according to historian Leo Ribuffo, auto magnate Henry Ford

Henry Ford (July 30, 1863 – April 7, 1947) was an American Technological and industrial history of the United States, industrialist and business magnate. As the founder of the Ford Motor Company, he is credited as a pioneer in making automob ...

sponsored a major outburst of attacks on Jews in his magazine, the ''Dearborn Independent'', bundles of which he sent to all Ford dealerships every week. It especially promoted ''The Protocols of the Elders of Zion

''The Protocols of the Elders of Zion'' is a fabricated text purporting to detail a Jewish plot for global domination. Largely plagiarized from several earlier sources, it was first published in Imperial Russia in 1903, translated into multip ...

'', and also published new articles that blamed Jews for America's problems. In 1927, following a lawsuit by Aaron Sapiro, Ford publicly apologized for his anti-Semitism, retracted his earlier views, and closed his magazine.

A "Jewish problem" was discussed in majority-European countries outside Europe, even as the Holocaust was in progress. American aviator and celebrity Charles A. Lindbergh used the phrase repeatedly in public speeches and writing. For example in his diary entry of September 18, 1941, published in 1970 as part of '' The Wartime Journals of Charles A. Lindbergh'', he wrote

Contemporary use

A dominant anti-Semitic conspiracy theory is the belief that Jewish people have undue influence over the media, banking, and politics. Based on this conspiracy theory, certain groups and activists discuss the "Jewish Question" and offer different proposals to address it. In the early 21st century,white nationalists

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no chroma). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully (or almost fully) reflect and scatter all the visible wav ...

, alt-right

The alt-right (abbreviated from alternative right) is a Far-right politics, far-right, White nationalism, white nationalist movement. A largely Internet activism, online phenomenon, the alt-right originated in the United States during the late ...

ers, and neo-Nazis

Neo-Nazism comprises the post–World War II militant, social, and political movements that seek to revive and reinstate Nazi ideology. Neo-Nazis employ their ideology to promote hatred and racial supremacy (often white supremacy), to att ...

have used the initialism JQ in order to refer to the Jewish question."JQ stands for the 'Jewish Question,' an anti-Semitic conspiracy theory that Jewish people have undue influence over the media, banking and politics that must somehow be addressed" (Christopher Mathias, Jenna Amatulli, Rebecca Klein, 2018, ''The HuffPost'', 3 March 2018, https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/florida-public-school-teacher-white-nationalist-podcast_us_5a99ae32e4b089ec353a1fba)

See also

* Anti-Semite and Jew *Antisemitic canard

Antisemitic tropes, also known as antisemitic canards or antisemitic libels, are " sensational reports, misrepresentations or fabrications" about Jews as an ethnicity or Judaism as a religion.

Since the 2nd century, malicious allegations of ...

* Armenian question

*

* German question

* Irish question

* Martin Luther and antisemitism

* National question

* Negro Question

* Polish question

* The Race Question

UNESCO has published several statements about issues of race.

The statements include:

*''Statement on race'' (Paris, July 1950)

*''Statement on the nature of race and race differences'' (Paris, June 1951)

*''Proposals on the biological a ...

* Ulrich Fleischhauer

Ulrich Fleischhauer (14 July 1876 – 20 October 1960) (Pseudonyms ''Ulrich Bodung'', and ''Israel Fryman'') was a leading publisher of antisemitic books and news articles reporting on a perceived Judeo-Masonic conspiracy theory and "nefarious ...

* Useful Jew

Notes

References

Further reading

* Arendt, Hannah. "The Jew as Pariah" in ''The Jew as Pariah: Jewish Identity and Politics in the Modern Age''. R.H. Feldman, ed. New York: Grove Press 1978. *Birnbaum, Pierre and Ira Katznelson, eds. ''Paths of Emancipation: Jews, States, and Citizenship''. Princeton: Princeton University Press 1995. * Case, Holly. ''The Age of Questions'' (Princeton University Press, 2018)excerpt

*Katz, Jacob. ''Out of the Ghetto: The Social Background of Jewish Emancipation, 1770-1870''. Cambridge: Harvard University Press 1973. *Kovach, Thomas. "The Elusiveness of Tolerance: The" Jewish Question" from Lessing to the Napoleonic Wars." ''Eighteenth-Century Studies'' 32.1 (1998): 127-128. * Roudinesco, Elisabeth (2013

''Returning to the Jewish Question''

London, Polity Press, p. 280 * Wolf, Lucien (1919

"Notes on the Diplomatic History of the Jewish Question"

Jewish Historical Society of England * The Jewish cause: an introduction to a different Israeli history – the subject's impact during the Holocaust * * Smith, Steven B. ''Spinoza, Liberalism, and the Question of Jewish Identity''. New Haven: Yale University Press 1997.

External links

Israeli Foreign Policy and the Jewish Question

{{DEFAULTSORT:Jewish Question National questions Jewish political status Incitement to genocide of Jews The Holocaust Adolf Hitler Karl Marx Debates about social issues Minority rights