The history of the Jews in Poland dates back at least 1,000 years. For centuries,

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

was home to the largest and most significant

Jewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

community in the world. Poland was a principal center of

Jewish culture

Jewish culture is the culture of the Jewish people, from its formation in ancient times until the current age. Judaism itself is not simply a faith-based religion, but an orthopraxy and Ethnoreligious group, ethnoreligion, pertaining to deed, ...

, because of the long period of statutory

religious tolerance

Religious tolerance or religious toleration may signify "no more than forbearance and the permission given by the adherents of a dominant religion for other religions to exist, even though the latter are looked on with disapproval as inferior, ...

and

social autonomy which ended after the

Partitions of Poland

The Partitions of Poland were three partition (politics), partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth that took place between 1772 and 1795, toward the end of the 18th century. They ended the existence of the state, resulting in the eli ...

in the 18th century. During

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

there was a nearly complete

genocidal

Genocide is violence that targets individuals because of their membership of a group and aims at the destruction of a people. Raphael Lemkin, who first coined the term, defined genocide as "the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group" b ...

destruction of the Polish Jewish community by

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

and its collaborators of various nationalities, during the

German occupation of Poland

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

between 1939 and 1945, called the

Holocaust

The Holocaust (), known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as the (), was the genocide of History of the Jews in Europe, European Jews during World War II. From 1941 to 1945, Nazi Germany and Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy ...

. Since the

fall of communism in Poland

Autumn, also known as fall (especially in US & Canada), is one of the four temperate seasons on Earth. Outside the tropics, autumn marks the transition from summer to winter, in September (Northern Hemisphere) or March ( Southern Hemispher ...

, there has been a renewed interest in Jewish culture, featuring an annual

Jewish Culture Festival

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, religion, and community are highly inte ...

, new study programs at Polish secondary schools and universities, and the opening of

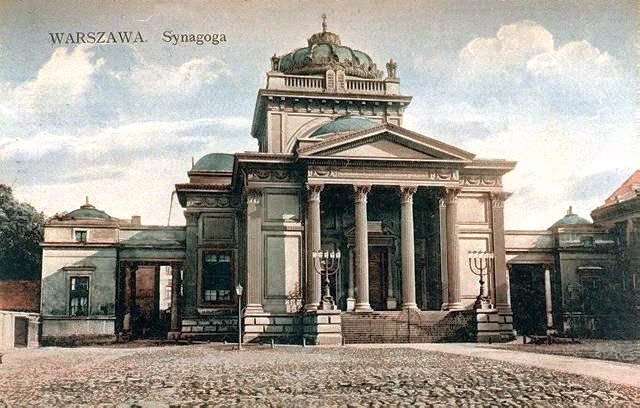

Warsaw

Warsaw, officially the Capital City of Warsaw, is the capital and List of cities and towns in Poland, largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the Vistula, River Vistula in east-central Poland. Its population is officially estimated at ...

's

Museum of the History of Polish Jews

POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews () is a museum on the site of the former Warsaw Ghetto. The Hebrew language, Hebrew word ''Polin'' in the museum's English name means either "Poland" or "rest here" and relates to a legend about the ar ...

.

From the founding of the

Kingdom of Poland

The Kingdom of Poland (; Latin: ''Regnum Poloniae'') was a monarchy in Central Europe during the Middle Ages, medieval period from 1025 until 1385.

Background

The West Slavs, West Slavic tribe of Polans (western), Polans who lived in what i ...

in 1025 until the early years of the

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, also referred to as Poland–Lithuania or the First Polish Republic (), was a federation, federative real union between the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania ...

created in 1569, Poland was the most tolerant country in Europe.

Poland became a shelter for Jews persecuted and expelled from various European countries and the home to the world's largest Jewish community of the time. According to some sources, about three-quarters of the world's Jews lived in Poland by the middle of the 16th century.

With the weakening of the Commonwealth and growing religious strife (due to the

Protestant Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the papacy and ...

and

Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

Counter-Reformation

The Counter-Reformation (), also sometimes called the Catholic Revival, was the period of Catholic resurgence that was initiated in response to, and as an alternative to or from similar insights as, the Protestant Reformations at the time. It w ...

), Poland's traditional tolerance began to wane from the 17th century.

After the

Partitions of Poland

The Partitions of Poland were three partition (politics), partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth that took place between 1772 and 1795, toward the end of the 18th century. They ended the existence of the state, resulting in the eli ...

in 1795 and the destruction of Poland as a

sovereign state

A sovereign state is a State (polity), state that has the highest authority over a territory. It is commonly understood that Sovereignty#Sovereignty and independence, a sovereign state is independent. When referring to a specific polity, the ter ...

, Polish Jews became subject to the laws of the partitioning powers, including the increasingly

antisemitic Russian Empire,

as well as

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

and

Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (, ) was a German state that existed from 1701 to 1918.Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. Rev. ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1946. It played a signif ...

(later a part of the

German Empire

The German Empire (),; ; World Book, Inc. ''The World Book dictionary, Volume 1''. World Book, Inc., 2003. p. 572. States that Deutsches Reich translates as "German Realm" and was a former official name of Germany. also referred to as Imperia ...

). When Poland regained independence in the

aftermath of World War I

The aftermath of World War I saw far-reaching and wide-ranging cultural, economic, and social change across Europe, Asia, Africa, and in areas outside those that were directly involved. Four empires collapsed due to the war, old countries were a ...

, it was still the center of the European Jewish world, with one of the world's largest Jewish communities of over 3 million.

Antisemitism

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

was a growing problem throughout Europe in those years, from both the political establishment and the general population.

Throughout the

interwar period

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period, also known as the interbellum (), lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days) – from the end of World War I (WWI) to the beginning of World War II ( ...

, Poland supported Jewish emigration from Poland and the creation of a Jewish state in

Palestine

Palestine, officially the State of Palestine, is a country in West Asia. Recognized by International recognition of Palestine, 147 of the UN's 193 member states, it encompasses the Israeli-occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and th ...

. The Polish state also supported Jewish paramilitary groups such as the

Haganah

Haganah ( , ) was the main Zionist political violence, Zionist paramilitary organization that operated for the Yishuv in the Mandatory Palestine, British Mandate for Palestine. It was founded in 1920 to defend the Yishuv's presence in the reg ...

,

Betar

The Betar Movement (), also spelled Beitar (), is a Revisionist Zionism, Revisionist Zionist youth movement founded in 1923 in Riga, Latvia, by Ze'ev Jabotinsky, Vladimir (Ze'ev) Jabotinsky. It was one of several right-wing youth movements tha ...

, and

Irgun

The Irgun (), officially the National Military Organization in the Land of Israel, often abbreviated as Etzel or IZL (), was a Zionist paramilitary organization that operated in Mandatory Palestine between 1931 and 1948. It was an offshoot of th ...

, providing them with weapons and training.

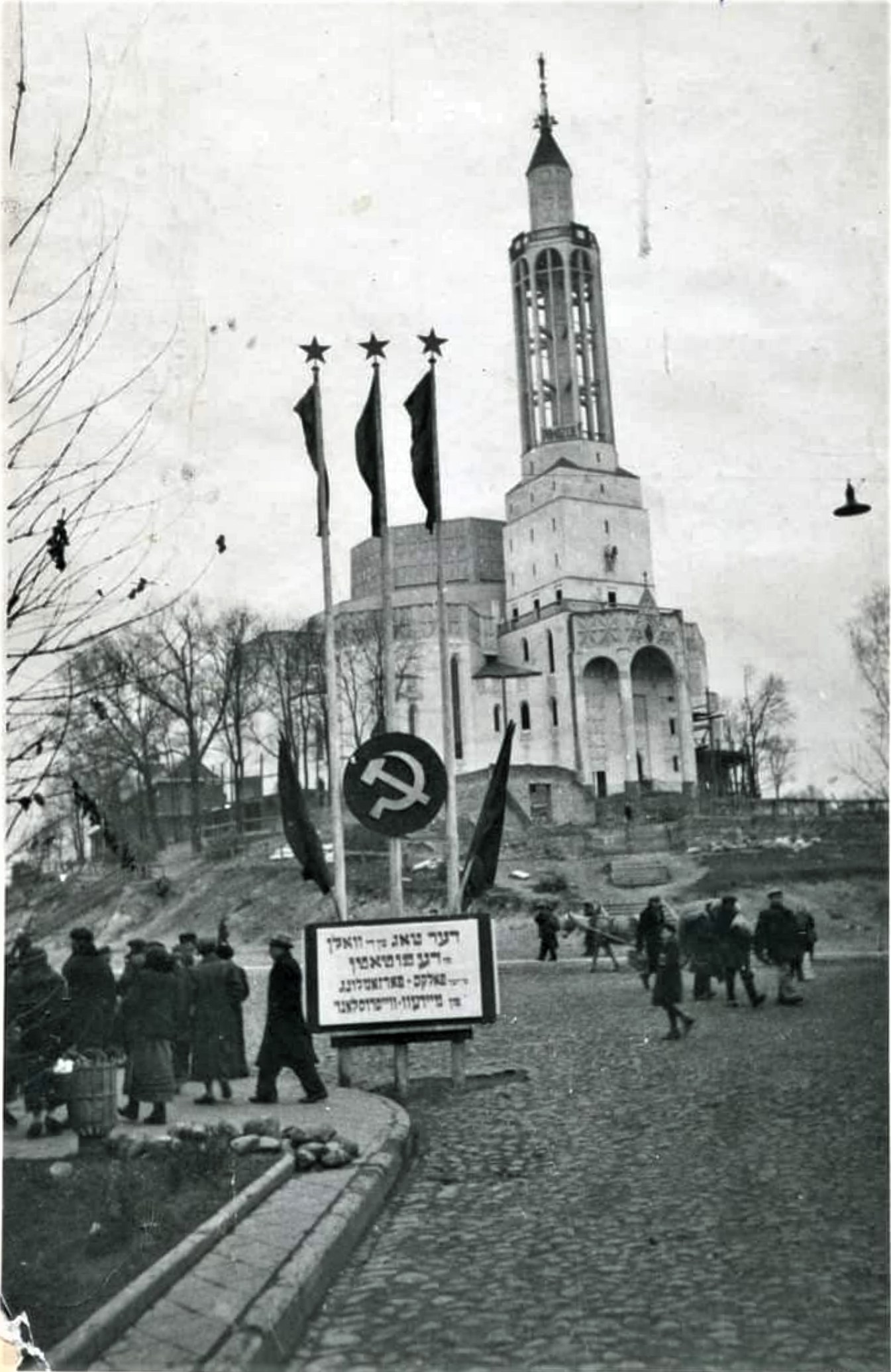

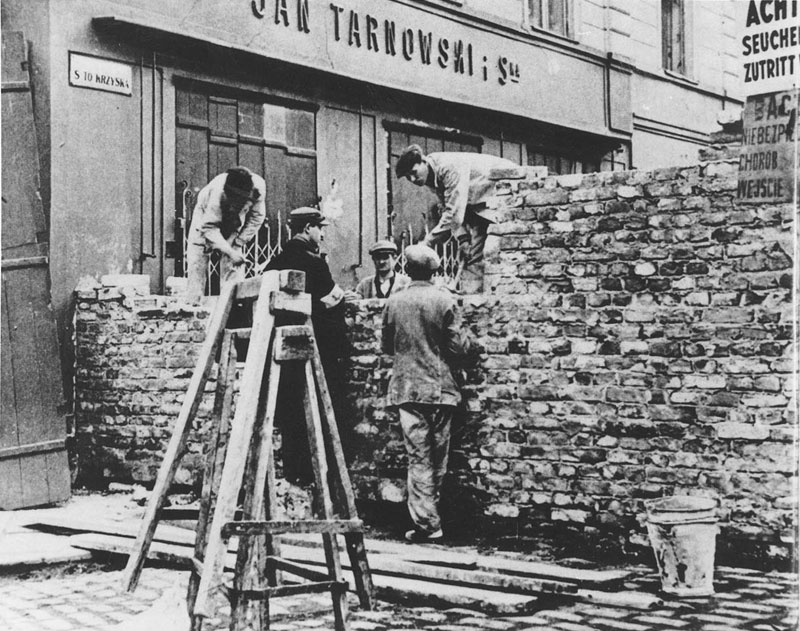

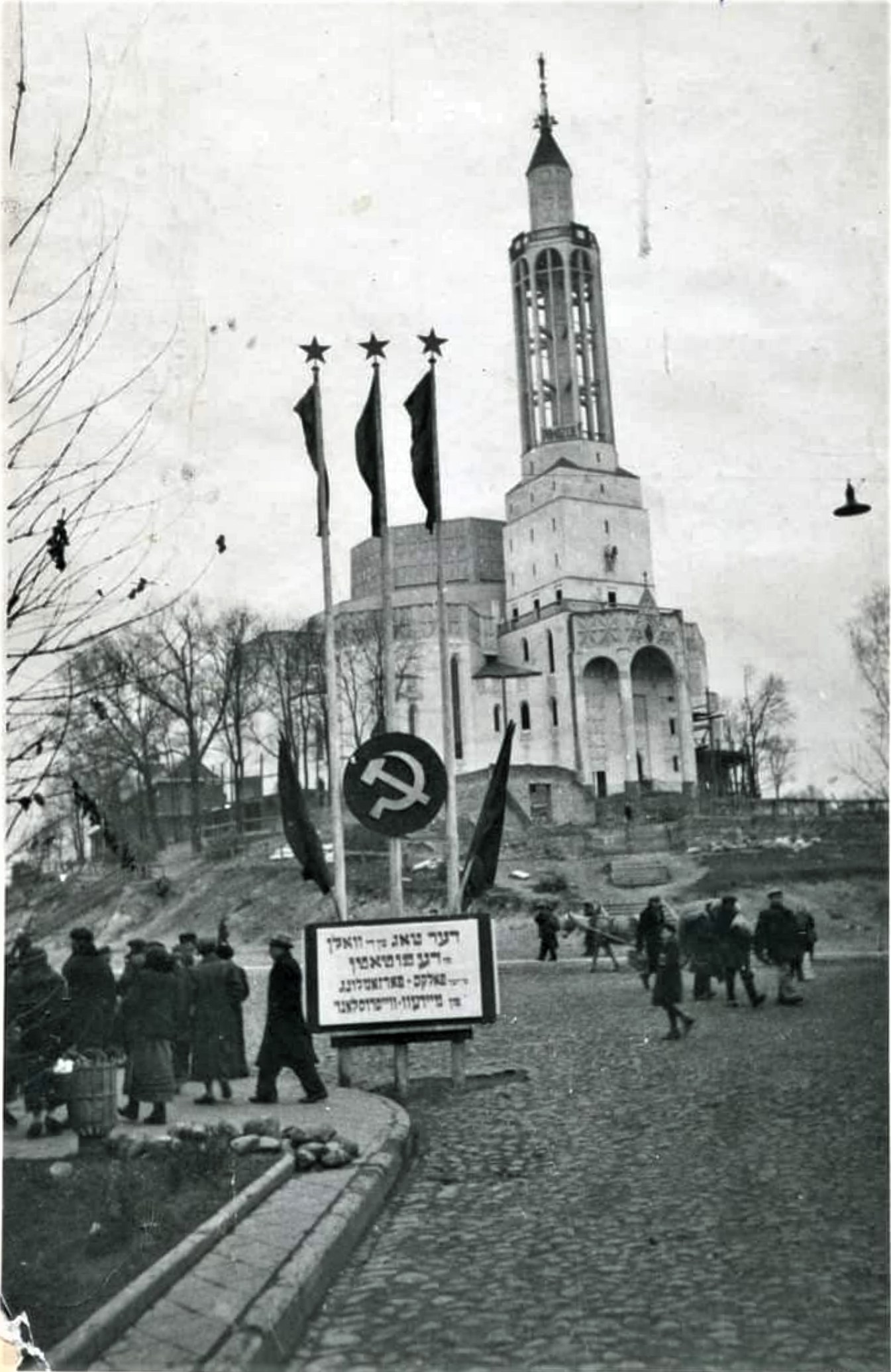

In 1939, at the start of World War II, Poland was partitioned between

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

and the

Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

(see

Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, officially the Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, and also known as the Hitler–Stalin Pact and the Nazi–Soviet Pact, was a non-aggression pact between Nazi Ge ...

). One-fifth of the Polish population perished during World War II; the 3,000,000 Polish Jews murdered in the Holocaust, who constituted 90% of Polish Jewry, made up half of all Poles killed during the war.

While the Holocaust occurred largely in

German-occupied Poland German-occupied Poland can refer to:

* General Government

* Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany

* Occupation of Poland (1939–1945)

* Prussian Partition

The Prussian Partition (), or Prussian Poland, is the former territories of the Polish� ...

, it was orchestrated and perpetrated by the Nazis. Polish attitudes to the Holocaust varied widely, from

actively risking death in order to save Jewish lives, and passive refusal to inform on them, to indifference, blackmail,

and in extreme cases, committing premeditated murders such as in the

Jedwabne pogrom.

Collaboration

Collaboration (from Latin ''com-'' "with" + ''laborare'' "to labor", "to work") is the process of two or more people, entities or organizations working together to complete a task or achieve a goal. Collaboration is similar to cooperation. The ...

by non-Jewish Polish citizens in the Holocaust was sporadic, but incidents of hostility against Jews are well documented and have been a subject of renewed scholarly interest during the 21st century.

In the post-war period, many of the approximately 200,000 Jewish survivors registered at the

Central Committee of Polish Jews

The Central Committee of Polish Jews also referred to as the Central Committee of Jews in Poland and abbreviated CKŻP, (, ) was a state-sponsored political representation of Jews in Poland at the end of World War II. It was established on 12 Nov ...

or CKŻP (of whom 136,000 arrived from the Soviet Union)

left the

Polish People's Republic

The Polish People's Republic (1952–1989), formerly the Republic of Poland (1947–1952), and also often simply known as Poland, was a country in Central Europe that existed as the predecessor of the modern-day democratic Republic of Poland. ...

for the nascent

State of Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

or the

Americas

The Americas, sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North America and South America.''Webster's New World College Dictionary'', 2010 by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Cleveland, Ohio. When viewed as a sing ...

. Their departure was hastened by the destruction of Jewish institutions,

post-war anti-Jewish violence, and the hostility of the Communist Party to both religion and private enterprise, but also because in 1946–1947 Poland was the only

Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc (Combloc), the Socialist Bloc, the Workers Bloc, and the Soviet Bloc, was an unofficial coalition of communist states of Central and Eastern Europe, Asia, Africa, and Latin America that were a ...

country to allow free Jewish

aliyah

''Aliyah'' (, ; ''ʿălīyyā'', ) is the immigration of Jews from Jewish diaspora, the diaspora to, historically, the geographical Land of Israel or the Palestine (region), Palestine region, which is today chiefly represented by the Israel ...

to Israel,

without visas or exit permits.

Most of the remaining Jews left Poland in late 1968 as the result of the

"anti-Zionist" campaign. After the

fall of the Communist regime in 1989, the situation of Polish Jews became normalized and those who were Polish citizens before World War II were allowed to renew Polish

citizenship

Citizenship is a membership and allegiance to a sovereign state.

Though citizenship is often conflated with nationality in today's English-speaking world, international law does not usually use the term ''citizenship'' to refer to nationalit ...

.

According to the

2021 Polish census, there were 17,156 Jews living in Poland as of 2021.

[

]

Early history to Golden Age: 966–1572

Early history: 966–1385

The first Jews to visit Polish territory were traders, while permanent settlement began during the

The first Jews to visit Polish territory were traders, while permanent settlement began during the Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and at times directed by the Papacy during the Middle Ages. The most prominent of these were the campaigns to the Holy Land aimed at reclaiming Jerusalem and its surrounding t ...

. Travelling along trade routes leading east to Kyiv

Kyiv, also Kiev, is the capital and most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city of Ukraine. Located in the north-central part of the country, it straddles both sides of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2022, its population was 2, ...

and Bukhara

Bukhara ( ) is the List of cities in Uzbekistan, seventh-largest city in Uzbekistan by population, with 280,187 residents . It is the capital of Bukhara Region.

People have inhabited the region around Bukhara for at least five millennia, and t ...

, Jewish merchants, known as Radhanites

The Radhanites or Radanites (; ) were early medieval Jewish merchants, active in the trade between Christendom and the Muslim world during roughly the 8th to the 10th centuries.

Many trade routes previously established under the Roman Empire cont ...

, crossed Silesia

Silesia (see names #Etymology, below) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Silesia, Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at 8, ...

. One of them, a diplomat and merchant from the Moorish

The term Moor is an exonym used in European languages to designate the Muslim populations of North Africa (the Maghreb) and the Iberian Peninsula (particularly al-Andalus) during the Middle Ages.

Moors are not a single, distinct or self-defi ...

town of Tortosa

Tortosa (, ) is the capital of the '' comarca'' of Baix Ebre, in Catalonia, Spain.

Tortosa is located at above sea level, by the Ebro river, protected on its northern side by the mountains of the Cardó Massif, of which Buinaca, one of the hi ...

in Spanish Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus () was the Muslim-ruled area of the Iberian Peninsula. The name refers to the different Muslim states that controlled these territories at various times between 711 and 1492. At its greatest geographical extent, it occupied most o ...

, known by his Arabic name, Ibrahim ibn Yaqub

Ibrahim ibn Yaqub ( ''Ibrâhîm ibn Ya'qûb al-Ṭarṭûshi'' or ''al-Ṭurṭûshî''; , ''Avraham ben Yaʿakov''; 961–62) was a 10th-century Hispano-Arabic, Sephardi Jewish traveler, probably a merchant, who may have also engaged in diploma ...

, was the first chronicler to mention the Polish state ruled by Prince Mieszko I

Mieszko I (; – 25 May 992) was Duchy of Poland (966–1025), Duke of Poland from 960 until his death in 992 and the founder of the first unified History of Poland, Polish state, the Civitas Schinesghe. A member of the Piast dynasty, he was t ...

. In the summer of 965 or 966, Jacob made a trade and diplomatic journey from his native Toledo

Toledo most commonly refers to:

* Toledo, Spain, a city in Spain

* Province of Toledo, Spain

* Toledo, Ohio, a city in the United States

Toledo may also refer to:

Places Belize

* Toledo District

* Toledo Settlement

Bolivia

* Toledo, Or ...

in Muslim Spain to the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

and then to the Slavic countries.Gniezno

Gniezno (; ; ) is a city in central-western Poland, about east of Poznań. Its population in 2021 was 66,769, making it the sixth-largest city in the Greater Poland Voivodeship. The city is the administrative seat of Gniezno County (''powiat'') ...

, at that time the capital of the Polish kingdom

The Kingdom of Poland (; Latin: ''Regnum Poloniae'') was a monarchy in Central Europe during the medieval period from 1025 until 1385.

Background

The West Slavic tribe of Polans who lived in what is today the historic region of Greater Po ...

of the Piast dynasty

The House of Piast was the first historical ruling dynasty of Poland. The first documented List of Polish monarchs, Polish monarch was Duke Mieszko I of Poland, Mieszko I (–992). The Poland during the Piast dynasty, Piasts' royal rule in Pol ...

. Among the first Jews to arrive in Poland in 1097 or 1098 were those banished from Prague

Prague ( ; ) is the capital and List of cities and towns in the Czech Republic, largest city of the Czech Republic and the historical capital of Bohemia. Prague, located on the Vltava River, has a population of about 1.4 million, while its P ...

.[ The first permanent Jewish community is mentioned in 1085 by a Jewish scholar Jehuda ha-Kohen in the city of ]Przemyśl

Przemyśl () is a city in southeastern Poland with 56,466 inhabitants, as of December 2023. Data for territorial unit 1862000. In 1999, it became part of the Podkarpackie Voivodeship, Subcarpathian Voivodeship. It was previously the capital of Prz ...

.Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the Europe, European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural and socio-economic connotations. Its eastern boundary is marked by the Ural Mountain ...

, the principal activity of Jews in medieval Poland

This article covers the history of Poland in the Middle Ages. This time covers roughly a millennium, from the 5th century to the 16th century. It is commonly dated from the Fall of the Western Roman Empire, and contrasted with a later Early Modern ...

was commerce and trade, including the export and import of goods such as cloth, linen, furs, hides, wax, metal objects, and slaves.

The first extensive Jewish migration from

The first extensive Jewish migration from Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's extent varies depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the Western half of the ancient Mediterranean ...

to Poland occurred at the time of the First Crusade

The First Crusade (1096–1099) was the first of a series of religious wars, or Crusades, initiated, supported and at times directed by the Latin Church in the Middle Ages. The objective was the recovery of the Holy Land from Muslim conquest ...

in 1098. Under Bolesław III (1102–1139), Jews, encouraged by the tolerant regime of this ruler, settled throughout Poland, including over the border in Lithuania

Lithuania, officially the Republic of Lithuania, is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea, bordered by Latvia to the north, Belarus to the east and south, P ...

n territory as far as Kyiv

Kyiv, also Kiev, is the capital and most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city of Ukraine. Located in the north-central part of the country, it straddles both sides of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2022, its population was 2, ...

. Bolesław III recognized the utility of Jews in the development of the commercial interests of his country. Jews came to form the backbone of the Polish economy. Mieszko III employed Jews in his mint as engravers and technical supervisors, and the coins

A coin is a small object, usually round and flat, used primarily as a medium of exchange or legal tender. They are standardized in weight, and produced in large quantities at a mint in order to facilitate trade. They are most often issued by ...

minted during that period even bear Hebraic markings.[ Jews worked on commission for the mints of other contemporary Polish princes, including Casimir the Just, ]Bolesław I the Tall

Bolesław I the Tall (; 1127 – 7 or 8 December 1201) was Duke of Wrocław from 1163 until his death in 1201.

Early years

Boleslaw was the eldest son of Władysław II the Exile by his wife Agnes of Babenberg, daughter of Margrave Leopold II ...

and Władysław III Spindleshanks

Władysław III Spindleshanks (; b. 1161/67 – 3 November 1231), of the Piast dynasty, was Duke of Greater Poland (during 1194–1202 over all the land and during 1202–1229 only over the southern part), High Duke of Poland and Duke of Kraków d ...

.[ Jews enjoyed undisturbed peace and prosperity in the many principalities into which the country was then divided; they formed the middle class in a country where the general population consisted of ]landlord

A landlord is the owner of property such as a house, apartment, condominium, land, or real estate that is rented or leased to an individual or business, known as a tenant (also called a ''lessee'' or ''renter''). The term landlord appli ...

s (developing into ''szlachta

The ''szlachta'' (; ; ) were the nobility, noble estate of the realm in the Kingdom of Poland, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Depending on the definition, they were either a warrior "caste" or a social ...

'', the unique Polish nobility) and peasants, and they were instrumental in promoting the commercial interests of the land.

Another factor for the Jews to emigrate to Poland was the Magdeburg rights

Magdeburg rights (, , ; also called Magdeburg Law) were a set of town privileges first developed by Otto I, Holy Roman Emperor (936–973) and based on the Flemish Law, which regulated the degree of internal autonomy within cities and villages gr ...

(or Magdeburg Law), a charter given to Jews, among others, that specifically outlined the rights and privileges that Jews had in Poland. For example, they could maintain communal autonomy, and live according to their own laws. This made it very attractive for Jewish communities to pick up and move to Poland.

The first mention of Jewish settlers in Płock

Płock (pronounced ), officially the Ducal Capital City of Płock, is a city in central Poland, on the Vistula river, in the Masovian Voivodeship. According to the data provided by Central Statistical Office (Poland), GUS on 31 December 2021, the ...

dates from 1237, in Kalisz from 1287 and a Żydowska (Jewish) street in Kraków in 1304.[

The tolerant situation was gradually altered by the ]Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

on the one hand, and by the neighboring German states on the other.Bolesław the Pious

Bolesław the Pious (1224/27 – 14 April 1279) was a Duke of Greater Poland during 1239–1247 (according to some historians during 1239–1241, sole Duke of Ujście), Duke of Kalisz during 1247–1249, Duke of Gniezno during 1249–1250, Duk ...

of Kalisz

Kalisz () is a city in central Poland, and the second-largest city in the Greater Poland Voivodeship, with 97,905 residents (December 2021). It is the capital city of the Kalisz Region. Situated on the Prosna river in the southeastern part of Gr ...

, Prince of Great Poland

Greater Poland, often known by its Polish name Wielkopolska (; ), is a Polish Polish historical regions, historical region of west-central Poland. Its chief and largest city is Poznań followed by Kalisz, the oldest city in Poland.

The bound ...

. With the consent of the class representatives and higher officials, in 1264 he issued a General Charter of Jewish Liberties (commonly called the Statute of Kalisz

The General Charter of Jewish rights known as the Statute of Kalisz, and the Kalisz Privilege, granted Jews in the Middle Ages some protection against discrimination in Poland compared to other places in Europe. These rights included exclusive ...

), which granted all Jews the freedom to worship, trade, and travel. Similar privileges were granted to the Silesian Jews by the local princes, Henryk IV Probus

Henry Probus (Latin for the Righteous; or ''Prawy''; ; – 23 June 1290) was a member of the Silesian branch of the royal Polish Piast dynasty. He was Duke of Silesia at Wrocław from 1266 as well as the ruler of the Seniorate Provinc ...

of Wrocław in 1273–90, Henryk III of Głogów in 1274 and 1299, Henryk V the Fat of Legnica in 1290–95, and Bolko III the Generous of Legnica and Wrocław in 1295.[ Article 31 of the Statute of Kalisz tried to rein in the Catholic Church from disseminating ]blood libel

Blood libel or ritual murder libel (also blood accusation) is an antisemitic canardTurvey, Brent E. ''Criminal Profiling: An Introduction to Behavioral Evidence Analysis'', Academic Press, 2008, p. 3. "Blood libel: An accusation of ritual mu ...

s against the Jews, by stating: "Accusing Jews of drinking Christian blood is expressly prohibited. If despite this a Jew should be accused of murdering a Christian child, such charge must be sustained by testimony of three Christians and three Jews."

During the next hundred years, the Church pushed for the persecution of Jews while the rulers of Poland usually protected them.[

In 1332, King ]Casimir III the Great

Casimir III the Great (; 30 April 1310 – 5 November 1370) reigned as the King of Poland from 1333 to 1370. He also later became King of Ruthenia in 1340, retaining the title throughout the Galicia–Volhynia Wars. He was the last Polish king fr ...

(1303–1370) amplified and expanded Bolesław's old charter with the Wiślicki Statute

The Statutes of Casimir the Great or Piotrków-Wiślica Statutes () are a collection of laws issued by Casimir III the Great, the king of Poland, in the years 1346-1362 during Veche, congresses in Piotrków Trybunalski, Piotrków and Wiślica. It ...

. Under his reign, streams of Jewish immigrants headed east to Poland and Jewish settlements are first mentioned as existing in Lvov

Lviv ( or ; ; ; see #Names and symbols, below for other names) is the largest city in western Ukraine, as well as the List of cities in Ukraine, fifth-largest city in Ukraine, with a population of It serves as the administrative centre of ...

(1356), Sandomierz

Sandomierz (pronounced: ; , ) is a historic town in south-eastern Poland with 23,863 inhabitants (), situated on the Vistula River near its confluence with the San, in the Sandomierz Basin. It has been part of Świętokrzyskie Voivodeship (Holy ...

(1367), and Kazimierz

Kazimierz (; ; ) is a historical district of Kraków and Kraków Old Town, Poland. From its inception in the 14th century to the early 19th century, Kazimierz was an independent city, a royal city of the Crown of the Polish Kingdom, located sou ...

near Kraków (1386).[ Casimir, who according to a legend had a Jewish lover named ]Esterka

Esterka (Estera) refers to a mythical Jewish mistress of Casimir the Great, the historical King of Poland who reigned between 1333 and 1370. Medieval Polish and Jewish chroniclers considered the legend as historical fact and report a wonderful lov ...

from Opoczno

Opoczno () is a town in south-central Poland, seat of Opoczno County in the Łódź Voivodeship. It has a long and rich history, and in the past it used to be one of the most important urban centers of northwestern Lesser Poland. Currently, Opoczno ...

serf

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery. It developed du ...

s and Jews". Under penalty of death, he prohibited the kidnapping of Jewish children for the purpose of enforced Christian

A Christian () is a person who follows or adheres to Christianity, a Monotheism, monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus Christ. Christians form the largest religious community in the wo ...

baptism

Baptism (from ) is a Christians, Christian sacrament of initiation almost invariably with the use of water. It may be performed by aspersion, sprinkling or affusion, pouring water on the head, or by immersion baptism, immersing in water eit ...

. He inflicted heavy punishment for the desecration of Jewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

cemeteries

A cemetery, burial ground, gravesite, graveyard, or a green space called a memorial park or memorial garden, is a place where the remains of many dead people are buried or otherwise entombed. The word ''cemetery'' (from Greek ) implies th ...

. Nevertheless, while the Jews of Poland enjoyed tranquility for the greater part of Casimir's reign, toward its close they were subjected to persecution on account of the Black Death

The Black Death was a bubonic plague pandemic that occurred in Europe from 1346 to 1353. It was one of the list of epidemics, most fatal pandemics in human history; as many as people perished, perhaps 50% of Europe's 14th century population. ...

. In 1348, the first blood libel

Blood libel or ritual murder libel (also blood accusation) is an antisemitic canardTurvey, Brent E. ''Criminal Profiling: An Introduction to Behavioral Evidence Analysis'', Academic Press, 2008, p. 3. "Blood libel: An accusation of ritual mu ...

accusation against Jews in Poland was recorded, and in 1367 the first pogrom took place in Poznań

Poznań ( ) is a city on the Warta, River Warta in west Poland, within the Greater Poland region. The city is an important cultural and business center and one of Poland's most populous regions with many regional customs such as Saint John's ...

.Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's extent varies depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the Western half of the ancient Mediterranean ...

, however, Polish Jews did not fare badly; and Jewish refugees from Germany fled to the more hospitable cities in Poland.

The early Jagiellon era: 1385–1506

As a result of the marriage of

As a result of the marriage of Władysław II Jagiełło

Jogaila (; 1 June 1434), later Władysław II Jagiełło (),Other names include (; ) (see also Names and titles of Władysław II Jagiełło) was Grand Duke of Lithuania beginning in 1377 and starting in 1386, becoming King of Poland as well. ...

to Jadwiga, daughter of Louis I of Hungary

Louis I, also Louis the Great (; ; ) or Louis the Hungarian (; 5 March 132610 September 1382), was King of Hungary and Croatia from 1342 and King of Poland from 1370. He was the first child of Charles I of Hungary and his wife, Elizabeth of ...

, Lithuania was united with the kingdom of Poland. In , broad privileges were extended to Lithuanian Jews

{{Jews and Judaism sidebar , Population

Litvaks ({{Langx, yi, ליטװאַקעס) or Lita'im ({{Langx, he, לִיטָאִים) are Jews who historically resided in the territory of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania (covering present-day Lithuan ...

including freedom of religion and commerce on equal terms with the Christians.Council of Constance

The Council of Constance (; ) was an ecumenical council of the Catholic Church that was held from 1414 to 1418 in the Bishopric of Constance (Konstanz) in present-day Germany. This was the first time that an ecumenical council was convened in ...

. In 1349 pogroms took place in many towns in Silesia

Silesia (see names #Etymology, below) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Silesia, Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at 8, ...

.[ There were accusations of ]blood libel

Blood libel or ritual murder libel (also blood accusation) is an antisemitic canardTurvey, Brent E. ''Criminal Profiling: An Introduction to Behavioral Evidence Analysis'', Academic Press, 2008, p. 3. "Blood libel: An accusation of ritual mu ...

by the priests, and new riots against the Jews in Poznań

Poznań ( ) is a city on the Warta, River Warta in west Poland, within the Greater Poland region. The city is an important cultural and business center and one of Poland's most populous regions with many regional customs such as Saint John's ...

in 1399. Accusations of blood libel by another fanatic priest led to the riots in Kraków

, officially the Royal Capital City of Kraków, is the List of cities and towns in Poland, second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city has a population of 804,237 ...

in 1407, although the royal guard hastened to the rescue.Black Death

The Black Death was a bubonic plague pandemic that occurred in Europe from 1346 to 1353. It was one of the list of epidemics, most fatal pandemics in human history; as many as people perished, perhaps 50% of Europe's 14th century population. ...

led to additional 14th-century outbreaks of violence against the Jews in Kalisz

Kalisz () is a city in central Poland, and the second-largest city in the Greater Poland Voivodeship, with 97,905 residents (December 2021). It is the capital city of the Kalisz Region. Situated on the Prosna river in the southeastern part of Gr ...

, Kraków and Bochnia

Bochnia is a town on the river Raba in southern Poland, administrative seat of Bochnia County in Lesser Poland Voivodeship. The town lies approximately halfway between Tarnów (east) and the regional capital Kraków (west). Bochnia is most noted ...

. Traders and artisans jealous of Jewish prosperity, and fearing their rivalry, supported the harassment. In 1423, the Statute of Warka

A statute is a law or formal written enactment of a legislature. Statutes typically declare, command or prohibit something. Statutes are distinguished from court law and unwritten law (also known as common law) in that they are the expressed wil ...

forbade Jews the granting of loans against letters of credit or mortgage and limited their operations exclusively to loans made on security of moveable property.[

In the 14th and 15th centuries, rich Jewish merchants and moneylenders leased the royal mint, salt mines and the collecting of customs and tolls. The most famous of them were Jordan and his son Lewko of Kraków in the 14th century and Jakub Slomkowicz of ]Lutsk

Lutsk (, ; see #Names and etymology, below for other names) is a city on the Styr River in northwestern Ukraine. It is the administrative center of Volyn Oblast and the administrative center of Lutsk Raion within the oblast. Lutsk has a populati ...

, Wolczko of Drohobych

Drohobych ( ; ; ) is a city in the south of Lviv Oblast, Ukraine. It is the administrative center of Drohobych Raion and hosts the administration of Drohobych urban hromada, one of the hromadas of Ukraine. In 1939–1941 and 1944–1959 it w ...

, Natko of Lviv

Lviv ( or ; ; ; see #Names and symbols, below for other names) is the largest city in western Ukraine, as well as the List of cities in Ukraine, fifth-largest city in Ukraine, with a population of It serves as the administrative centre of ...

, Samson of Zhydachiv, Josko of Hrubieszów

Hrubieszów (; ; , or ) is a town in southeastern Poland, with a population of around 18,212 (2016). It is the capital of Hrubieszów County within the Lublin Voivodeship.

Throughout history, the town's culture and architecture was strongly shaped ...

and Szania of Belz

Belz (, ; ; ) is a small city in Lviv Oblast, western Ukraine, located near the border with Poland between the Solokiya River (a tributary of the Bug River) and the Richytsia stream. Belz hosts the administration of Belz urban hromada, one of ...

in the 15th century. For example, Wolczko of Drohobycz, King Ladislaus Jagiełło's broker, was the owner of several villages in the Ruthenian voivodship and the soltys (administrator) of the village of Werbiz. Also, Jews from Grodno were in this period owners of villages, manors, meadows, fish ponds and mills. However, until the end of the 15th century, agriculture as a source of income played only a minor role among Jewish families. More important were crafts for the needs of both their fellow Jews and the Christian population (fur making, tanning, tailoring).[

In 1454 anti-Jewish riots flared up in ]Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; ; ) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. In a narrow, geographic sense, it roughly encompasses the territories of present-day Czechia that fall within the Elbe River's drainage basin, but historic ...

's ethnically-German Wrocław

Wrocław is a city in southwestern Poland, and the capital of the Lower Silesian Voivodeship. It is the largest city and historical capital of the region of Silesia. It lies on the banks of the Oder River in the Silesian Lowlands of Central Eu ...

and other Silesian cities, inspired by a Franciscan friar, John of Capistrano

John of Capistrano, OFM (, , , ; 24 June 1386 – 23 October 1456) was an Italian Franciscan friar and Catholic priest from the town of Capestrano, Abruzzo. Famous as a preacher, theologian, and inquisitor, he earned himself the nickname "the ...

, who accused Jews of profaning the Christian religion. As a result, Jews were banished from Lower Silesia. Zbigniew Olesnicki then invited John to conduct a similar campaign in Kraków and several other cities, to lesser effect.

The decline in the status of the Jews was briefly checked by Casimir IV Jagiellon

Casimir IV (Casimir Andrew Jagiellon; ; Lithuanian: ; 30 November 1427 – 7 June 1492) was Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1440 and King of Poland from 1447 until his death in 1492. He was one of the most active Polish-Lithuanian rulers; under ...

(1447–1492), but soon the Polish nobility

The ''szlachta'' (; ; ) were the nobility, noble estate of the realm in the Kingdom of Poland, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Depending on the definition, they were either a warrior "caste" or a social ...

forced him to issue the Statutes of Nieszawa The Nieszawa Statutes () were a set of laws enacted in the Kingdom of Poland of the Jagiellons, Kingdom of Poland in 1454, in the town of Nieszawa located in north-central Poland. The King Casimir IV Jagiellon made a number of concessions to the Pol ...

, which, among other things, abolished the ancient privileges of the Jews "as contrary to divine right and the law of the land." Nevertheless, the king continued to offer his protection to the Jews. Two years later Casimir issued another document announcing that he could not deprive the Jews of his benevolence on the basis of "the principle of tolerance which in conformity with God's laws obliged him to protect them".John I Albert

John I Albert (; 27 December 1459 – 17 June 1501) was King of Poland

Poland was ruled at various times either by dukes and princes (10th to 14th centuries) or by kings (11th to 18th centuries). During the latter period, a tradition of Roy ...

(1492–1501) and Alexander Jagiellon

Alexander Jagiellon (; ; 5 August 1461 – 19 August 1506) was Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1492 and King of Poland from 1501 until his death in 1506. He was the fourth son of Casimir IV and a member of the Jagiellonian dynasty. Alexander was el ...

(1501–1506). In 1495, Jews were ordered out of the center of Kraków and allowed to settle in the "Jewish town" of Kazimierz

Kazimierz (; ; ) is a historical district of Kraków and Kraków Old Town, Poland. From its inception in the 14th century to the early 19th century, Kazimierz was an independent city, a royal city of the Crown of the Polish Kingdom, located sou ...

. In the same year, Alexander, when he was the Grand Duke of Lithuania, followed the 1492 example of Spanish rulers and banished Jews from Lithuania. For several years they took shelter in Poland until 1503 when — after becoming King of Poland — he allowed them to return to Lithuania.[ The next year he issued a proclamation in which he stated that a policy of tolerance befitted "kings and rulers".][

Poland became more tolerant just as the Jews were expelled from Spain in 1492, as well as from ]Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

, Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

and Germany, thus stimulating Jewish immigration to Poland. Poland became recognized as a haven for Jewish exiles from Western Europe, and a cultural and spiritual center of the Jewish people. In 1503, King Alexander Jagiellon appointed Jacob Pollak

Rabbi Jacob Pollak (other common spelling Yaakov Pollack), son of Rabbi Joseph, was the founder of the Polish method of halakhic and Talmudic study known as the Pilpul.

Biography

He was born about 1460 or 1470 in Poland, and died at Lublin in ...

the first Chief Rabbi

Chief Rabbi () is a title given in several countries to the recognized religious leader of that country's Jewish community, or to a rabbinic leader appointed by the local secular authorities. Since 1911, through a capitulation by Ben-Zion Meir ...

of Poland. Pollak founded a ''yeshiva

A yeshiva (; ; pl. , or ) is a traditional Jewish educational institution focused on the study of Rabbinic literature, primarily the Talmud and halacha (Jewish law), while Torah and Jewish philosophy are studied in parallel. The stu ...

'' (a school for the study of rabbinic literature

Rabbinic literature, in its broadest sense, is the entire corpus of works authored by rabbis throughout Jewish history. The term typically refers to literature from the Talmudic era (70–640 CE), as opposed to medieval and modern rabbinic ...

) in Kraków.

Center of the Jewish world: 1506–1569

The most prosperous period for Polish Jews began following a new influx of Jews after the accession of Sigismund I in 1506. Sigismund protected the Jews in his realm, which encouraged many Jews to emigate to Poland, where they founded a community at Kraków.

The most prosperous period for Polish Jews began following a new influx of Jews after the accession of Sigismund I in 1506. Sigismund protected the Jews in his realm, which encouraged many Jews to emigate to Poland, where they founded a community at Kraków.Shalom Shachna

Shalom Shachna ( 1490 or 1510 – 1558) was a rabbi and Talmudist, and Rosh yeshiva of several great Acharonim including Moses Isserles, who was also his son-in-law.

Biography

Shachna was a pupil of Jacob Pollak, founder of the method of Talmud ...

(one of Jacob Pollak’s pupils) is counted among the pioneers of Talmudic

The Talmud (; ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law (''halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the centerpiece of Jewi ...

scholarship in Poland. In 1515 Shachna established the ''yeshiva'' in Lublin, which had the third largest Jewish community in Poland during that period. Shachna’s ''yeshiva'' produced several prominent rabbis, including Moses Isserles

Moses Isserles (; ; 22 February 1530 / 25 Adar I 5290 – 11 May 1572 / 18 Iyar 5332), also known by the acronym Rema, was an eminent Polish Ashkenazi rabbi, talmudist, and '' posek'' (expert in Jewish law). He is considered the "Maimonides o ...

and Solomon Luria

Shlomo Luria (1510 – November 7, 1573) () was one of the great Ashkenazic ''poskim'' (decisors of Jewish law) and teachers of his time. He is known for his work of Halakha, ''Yam Shel Shlomo'', and his Talmudic commentary ''Chochmat Shlomo''. L ...

, who succeeded Shachna as ''rosh yeshiva

Rosh yeshiva or Rosh Hayeshiva (, plural, pl. , '; Anglicized pl. ''rosh yeshivas'') is the title given to the dean of a yeshiva, a Jewish educational institution that focuses on the study of traditional religious texts, primarily the Talmud and th ...

'' of Lublin.

The first books to be published in the Hebrew and Yiddish languages in Poland were produced by the Halicz brothers, who established the first Jewish printing press in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in Kraków in 1534.Jewish mysticism

Academic study of Jewish mysticism, especially since Gershom Scholem's ''Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism'' (1941), draws distinctions between different forms of mysticism which were practiced in different eras of Jewish history. Of these, Kabbal ...

and ''Kabbalah

Kabbalah or Qabalah ( ; , ; ) is an esoteric method, discipline and school of thought in Jewish mysticism. It forms the foundation of Mysticism, mystical religious interpretations within Judaism. A traditional Kabbalist is called a Mekubbal ...

'' became popular and eminent Polish-Jewish scholars such as Mordecai Yoffe

Mordecai ben Avraham Yoffe (or Jaffe or Joffe) ( 1530 – 7 March 1612; Hebrew: מרדכי בן אברהם יפה) was a Rabbi, Rosh yeshiva and posek. He is best known as author of ''Levush Malkhus'', a ten-volume codification of Jewish law th ...

and Joel Sirkis

Joel ben Samuel Sirkis (Hebrew: רבי יואל בן שמואל סירקיש; born 1561 - March 14, 1640) also known as the Bach (an abbreviation of his magnum opus BAyit CHadash), was a prominent Ashkenazi posek and halakhist, who lived in Ce ...

devoted themselves to its study.

From the 14th century until 1538, Jews functioned widely as the arendator

In the history of the Russian Empire, and Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, arendator (literally "lease holder") (, ) was a person who leased fixed assets, such as land, mines, mills, inns, breweries, or distilleries, or of special rights, such a ...

s (lease-holders) of royal prerogative

The royal prerogative is a body of customary authority, Privilege (law), privilege, and immunity recognised in common law (and sometimes in Civil law (legal system), civil law jurisdictions possessing a monarchy) as belonging to the monarch, so ...

s in Poland such as the mint, salt mines, customs, and tax farming

Farming or tax-farming is a technique of financial management in which the management of a variable revenue stream is assigned by legal contract to a third party and the holder of the revenue stream receives fixed periodic rents from the contr ...

. Pressured by the nobility, in 1538 the Sejm

The Sejm (), officially known as the Sejm of the Republic of Poland (), is the lower house of the bicameralism, bicameral parliament of Poland.

The Sejm has been the highest governing body of the Third Polish Republic since the Polish People' ...

prohibited the Jews from participating in this highly lucrative activity. Although these so-called “great arenda” became one of the protected privileges of the Polish nobility, Jews continued to function as the arendators of landed estates leased from the nobility.

Sigismund II Augustus

Sigismund II Augustus (, ; 1 August 1520 – 7 July 1572) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, the son of Sigismund I the Old, whom Sigismund II succeeded in 1548. He was the first ruler of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and t ...

followed his father's tolerant policy, granting limited autonomy to the Jews and laying the foundation for the ''qahal

The ''qahal'' (), sometimes spelled ''kahal'', was a theocratic organizational structure in ancient Israelite society according to the Hebrew Bible, See column345-6 and an Ashkenazi Jewish system of a self-governing community or kehila from ...

'', or autonomous Jewish community. Poland-Lithuania became the main center for Ashkenazi Jew

Ashkenazi Jews ( ; also known as Ashkenazic Jews or Ashkenazim) form a distinct subgroup of the Jewish diaspora, that Ethnogenesis, emerged in the Holy Roman Empire around the end of the first millennium Common era, CE. They traditionally spe ...

ry and its ''yeshivot'' achieved fame during this period. Poland welcomed Jewish immigrants from Italy, as well as Sephardic Jews

Sephardic Jews, also known as Sephardi Jews or Sephardim, and rarely as Iberian Peninsular Jews, are a Jewish diaspora population associated with the historic Jewish communities of the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal) and their descendant ...

, Romaniote Jews

The Romaniote Jews or the Romaniotes (, ''Rhōmaniôtes''; ) are a Greek language, Greek-speaking Jewish ethnic divisions, ethnic Jewish community. They are one of the oldest Jewish communities in existence and the oldest Jewish community in Eu ...

, Mizrahi Jews

Mizrahi Jews (), also known as ''Mizrahim'' () in plural and ''Mizrahi'' () in singular, and alternatively referred to as Oriental Jews or ''Edot HaMizrach'' (, ), are terms used in Israeli discourse to refer to a grouping of Jews, Jewish c ...

, and Persian Jews

Iranian Jews, (; ) also Persian Jews ( ) or Parsim, constitute one of the oldest communities of the Jewish diaspora. Dating back to the History of ancient Israel and Judah, biblical era, they originate from the Jews who relocated to Iran (his ...

. Jewish religious life thrived in many Polish communities. By the middle of the 16th century, about 75% of all Jews lived in Poland.

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth: 1569–1795

After the death of Sigismund II Augustus in 1572, the

After the death of Sigismund II Augustus in 1572, the Polish nobility

The ''szlachta'' (; ; ) were the nobility, noble estate of the realm in the Kingdom of Poland, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Depending on the definition, they were either a warrior "caste" or a social ...

gathered in Warsaw and signed the Warsaw Confederation

The Warsaw Confederation, also called the Compact of Warsaw, was a political-legal act signed in Warsaw on 28 January 1573 by the first Convocation Sejm (''Sejm konwokacyjny'') held in the Polish Commonwealth. Convened and deliberating as a co ...

, a document in which representatives of all major religions pledged mutual support and tolerance. The central autonomous body that — along with the Chief Rabbinate — regulated Jewish life in Poland from about 1580 until 1764 was known as the Council of Four Lands

The Council of Four Lands (, ''Va'ad Arba' Aratzot'', ) was the central body of Jewish authority in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth from the second half of the 16th century to 1764, located in Lublin. The Council's first law is recorded as h ...

.

According to Gershon Hundert

Gershon David Hundert (1946 – October 27, 2023) was a Canadian historian of Early Modern Polish Jewry and Leanor Segal Professor at McGill University.

Biography

Born to a Jewish family in Toronto, Hundert was one of the three sons of Charle ...

, the following eight or nine decades of relative prosperity and security experienced by Polish Jews witnessed the appearance of "a virtual galaxy of sparkling intellectual figures." ''Yeshivot'' were established in prominent Jewish communities such as Brześć

Brest, formerly Brest-Litovsk and Brest-on-the-Bug, is a city in south-western Belarus at the border with Poland opposite the Polish town of Terespol, where the Bug and Mukhavets rivers meet, making it a border town. It serves as the adminis ...

, Lublin

Lublin is List of cities and towns in Poland, the ninth-largest city in Poland and the second-largest city of historical Lesser Poland. It is the capital and the centre of Lublin Voivodeship with a population of 336,339 (December 2021). Lublin i ...

, Lwów

Lviv ( or ; ; ; see #Names and symbols, below for other names) is the largest city in western Ukraine, as well as the List of cities in Ukraine, fifth-largest city in Ukraine, with a population of It serves as the administrative centre of ...

, Ostróg

Ostroh ( , ) is a city in Rivne Oblast, western Ukraine. It is situated on the Horyn, Horyn River. Ostroh was the administrative center of Ostroh Raion until 2020, but as a city of regional significance (Ukraine), city of oblast significance did ...

, and Poznań

Poznań ( ) is a city on the Warta, River Warta in west Poland, within the Greater Poland region. The city is an important cultural and business center and one of Poland's most populous regions with many regional customs such as Saint John's ...

.[ By 1600, the Jewish printing house in Kraków had printed some 200 works, mostly in Hebrew, but sometimes also in Yiddish.][ The growth of Talmudic scholarship in Poland was coincident with the greater prosperity of the Polish Jews, and because of their communal autonomy educational development was mostly along Talmudic lines. Exceptions are recorded, however, where Jewish youth sought secular instruction in the European universities. The rabbis became not merely expounders of ]Jewish law

''Halakha'' ( ; , ), also transliterated as ''halacha'', ''halakhah'', and ''halocho'' ( ), is the collective body of Jewish religious laws that are derived from the Written and Oral Torah. ''Halakha'' is based on biblical commandments ('' mit ...

, but also spiritual advisers, teachers, judges, and legislators. Polish Jewry found its views of life shaped by these principles, whose influence was felt in the home, in school, and in the synagogue.

The culture and intellectual output of the Jewish community in Poland had a profound impact on Judaism as a whole. Some Jewish historians have recounted that the word Poland is pronounced as ''Polania'' or ''Polin'' in Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

, and as transliterated

Transliteration is a type of conversion of a text from one writing system, script to another that involves swapping Letter (alphabet), letters (thus ''wikt:trans-#Prefix, trans-'' + ''wikt:littera#Latin, liter-'') in predictable ways, such as ...

into Hebrew, these names for Poland were interpreted as good omens because ''Polania'' can be broken down into three Hebrew words: ''po'' ("here"), ''lan'' ("dwells"), ''ya'' ("God

In monotheistic belief systems, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. In polytheistic belief systems, a god is "a spirit or being believed to have created, or for controlling some part of the un ...

"), and ''Polin'' into two words of: ''po'' ("here") ''lin'' ("ou should

OU or Ou or ou may stand for:

Universities United States

* Oakland University in Oakland County, Michigan

* Oakwood University in Huntsville, Alabama

* Oglethorpe University in Atlanta, Georgia

* Ohio University in Athens, Ohio

* Olivet Univers ...

dwell"). The message was that Poland was meant to be a good place for the Jews. According to Rabbi David HaLevi Segal

David ha-Levi Segal (c. 1586 – 20 February 1667), also known as the Turei Zahav (abbreviated Taz []) after the title of his significant ''halakha, halakhic'' commentary on the ''Shulchan Aruch'', was one of the greatest Jews of Poland, Polish ...

, Poland was a place where "most of the time the gentiles do no harm; on the contrary they do right by Israel" (''Divre David;'' 1689). It was during this period that a rueful pasquinade claiming that Poland was a "paradise for the Jews" gave birth to a proverb, which evolved into the saying that Poland was “heaven for the nobility, purgatory for townfolk, hell for peasants, and paradise for the Jews”.

Despite the Warsaw Confederation, there was a significant increase in antisemitism

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

at this time, partly due to the Counter-Reformation

The Counter-Reformation (), also sometimes called the Catholic Revival, was the period of Catholic resurgence that was initiated in response to, and as an alternative to or from similar insights as, the Protestant Reformations at the time. It w ...

and the growing influence of the Jesuits

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

.[Cossack Rebellions. Social Turmoil in the Sixteenth-century Ukraine](_blank)

/ref> By the 1590s, there were anti-Jewish outbreaks in Poznań, Lublin, Kraków, Vilnius

Vilnius ( , ) is the capital of and List of cities in Lithuania#Cities, largest city in Lithuania and the List of cities in the Baltic states by population, most-populous city in the Baltic states. The city's estimated January 2025 population w ...

and Kyiv.magnates

The term magnate, from the late Latin ''magnas'', a great man, itself from Latin ''magnus'', "great", means a man from the higher nobility, a man who belongs to the high office-holders or a man in a high social position, by birth, wealth or ot ...

to their private town

Private towns in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth were privately owned towns within the lands owned by magnates, bishops, knights and princes, among others.

Amongst the most well-known former private magnate towns are Białystok, Zamość, R ...

s. By the end of the 18th century, two-thirds of the royal towns and cities in the Commonwealth had pressed the king to grant them that privilege.

After the Union of Brest

The Union of Brest took place in 1595–1596 and represented an agreement by Eastern Orthodox Churches in the Ruthenian portions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth to accept the Pope's authority while maintaining Eastern Orthodox liturgical ...

in 1595–1596, the Orthodox church was outlawed in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. This, along with the mass migration of Jews to Ruthenia

''Ruthenia'' is an exonym, originally used in Medieval Latin, as one of several terms for Rus'. Originally, the term ''Rus' land'' referred to a triangular area, which mainly corresponds to the tribe of Polans in Dnieper Ukraine. ''Ruthenia' ...

and their negative perception by the local population,Khmelnytsky Uprising

The Khmelnytsky Uprising, also known as the Cossack–Polish War, Khmelnytsky insurrection, or the National Liberation War, was a Cossack uprisings, Cossack rebellion that took place between 1648 and 1657 in the eastern territories of the Poli ...

(1648 – 1657), in which Cossacks massacred tens of thousands of Jews, Catholics and Uniates

The Eastern Catholic Churches or Oriental Catholic Churches, also known as the Eastern-Rite Catholic Churches, Eastern Rite Catholicism, or simply the Eastern Churches, are 23 Eastern Christian autonomous (''sui iuris'') particular churches of ...

in the eastern and southern areas of the Polish Crown

The Crown of the Kingdom of Poland (; ) was a political and legal concept formed in the 14th century in the Kingdom of Poland, assuming unity, indivisibility and continuity of the state. Under this idea, the state was no longer seen as the pa ...

. Although the uprising was directed primarily against the wealthy nobility and landlords, the Cossacks perceived the Jews as allies of the former. The precise number of dead is not known, but the decrease of the Jewish population during this period is estimated at 100,000 to 200,000, which also includes emigration, deaths from diseases and ''jasyr'' (captivity in the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

).

The combined effects of the Cossack uprisings, along with internal conflicts in Poland and concurrent invasions of the Commonwealth by the Tsardom of Russia

The Tsardom of Russia, also known as the Tsardom of Moscow, was the centralized Russian state from the assumption of the title of tsar by Ivan the Terrible, Ivan IV in 1547 until the foundation of the Russian Empire by Peter the Great in 1721.

...

, the Swedish Empire

The Swedish Empire or the Great Power era () was the period in Swedish history spanning much of the 17th and early 18th centuries during which Sweden became a European great power that exercised territorial control over much of the Baltic regi ...

, the Crimean Tatars

Crimean Tatars (), or simply Crimeans (), are an Eastern European Turkic peoples, Turkic ethnic group and nation indigenous to Crimea. Their ethnogenesis lasted thousands of years in Crimea and the northern regions along the coast of the Blac ...

, and the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

, ended the Polish Golden Age

The Polish Golden Age (Polish language, Polish: ''Złoty Wiek Polski'' ) was the Renaissance in Poland, Renaissance period in the Kingdom of Poland and subsequently in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, which started in the late 15th century. H ...

and caused a decline of Polish power during the period known as "the Deluge

A deluge is a large downpour of rain, often a flood.

The Deluge refers to the flood narrative in the biblical book of Genesis.

Deluge or Le Déluge may also refer to:

History

*Deluge (history), the Swedish and Russian invasion of the Polish-L ...

". The amount of destruction, pillage and methodical plunder during the Siege of Kraków (1657)

The siege of Kraków was one of the military conflicts of the Swedish and Transylvanian invasion of Poland, which took place in the summer of 1657. The royal city of Kraków, had been occupied for two years by a Swedish-Transylvanian garrison ...

was so enormous that parts the city never again recovered. Which was later followed by the massacres by Stefan Czarniecki

Stefan Czarniecki (Polish: of the Łodzia coat of arms, 1599 – 16 February 1665) was a Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Polish szlachta, nobleman, general and military commander. In his career, he rose from a petty nobleman to a magnate hol ...

of the Ruthenian and Jewish population. Many Jews along with the townsfolk of Kalisz

Kalisz () is a city in central Poland, and the second-largest city in the Greater Poland Voivodeship, with 97,905 residents (December 2021). It is the capital city of the Kalisz Region. Situated on the Prosna river in the southeastern part of Gr ...

, Kraków, Poznań, Piotrków and Lublin also fell victim to recurring epidemics.[Dariusz Milewski]

Szwedzi w Krakowie (The Swedes in Kraków)

''Mówią Wieki

''Mówią Wieki'' (, meaning ''Centuries Speak'' in English) is a monthly popular science and history magazine published in Poland since 1958.

Editors in chief:

* Maria Bogucka (1958–1976)

* Bożena Krzywobłocka (1976–1977)

* Eugeniusz ...

'' monthly, 8 June 2007, Internet Archive.

The rise of Jewish sectarianism

The decade from the Khmelnytsky Uprising until after the Deluge (1648–1658) left a deep and lasting impression not only on the social life of the Polish–Lithuanian Jews, but on their spiritual life as well. The intellectual output of the Jews of Poland was reduced, and study of the Talmud became overly formalized and accessible to only a limited number of students. Some rabbis busied themselves with quibbles concerning religious laws, while others wrote commentaries on the Talmud in which hair-splitting arguments of no practical importance were discussed. Certain Ashkenazic movements began to appear at this time. At the same time, many miracle-workers made their appearance among the Jews of Poland, culminating in a series of Messianic movements, such as Sabbatianism and

The decade from the Khmelnytsky Uprising until after the Deluge (1648–1658) left a deep and lasting impression not only on the social life of the Polish–Lithuanian Jews, but on their spiritual life as well. The intellectual output of the Jews of Poland was reduced, and study of the Talmud became overly formalized and accessible to only a limited number of students. Some rabbis busied themselves with quibbles concerning religious laws, while others wrote commentaries on the Talmud in which hair-splitting arguments of no practical importance were discussed. Certain Ashkenazic movements began to appear at this time. At the same time, many miracle-workers made their appearance among the Jews of Poland, culminating in a series of Messianic movements, such as Sabbatianism and Frankism

Frankism was a Sabbatean religious movement originating in Rabbinic Judaism of the 18th and 19th. centuries, Created in Podolia, it was named after its founder, Jacob Frank. Frank completely rejected Jewish norms, preaching to his followers t ...

.Jewish mysticism

Academic study of Jewish mysticism, especially since Gershom Scholem's ''Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism'' (1941), draws distinctions between different forms of mysticism which were practiced in different eras of Jewish history. Of these, Kabbal ...

and overly formal Rabbinism came the teachings of Israel ben Eliezer, known as the ''Baal Shem Tov

Israel ben Eliezer (According to a forged document from the "Kherson Geniza", accepted only by Chabad, he was born in October 1698. Some Hasidic traditions place his birth as early as 1690, while Simon Dubnow and other modern scholars argue f ...

'', or ''BeShT'', (1698–1760), which had a profound effect on the Jews of Eastern Europe and Poland in particular. His disciples taught and encouraged the new fervent brand of Judaism based on ''Kabbalah

Kabbalah or Qabalah ( ; , ; ) is an esoteric method, discipline and school of thought in Jewish mysticism. It forms the foundation of Mysticism, mystical religious interpretations within Judaism. A traditional Kabbalist is called a Mekubbal ...

'' known as Hasidic Judaism

Hasidism () or Hasidic Judaism is a religious movement within Judaism that arose in the 18th century as a Spirituality, spiritual revival movement in contemporary Western Ukraine before spreading rapidly throughout Eastern Europe. Today, most ...

. The rise of Hasidic Judaism within Poland's borders and beyond had a great influence on the rise of Haredi Judaism

Haredi Judaism (, ) is a branch of Orthodox Judaism that is characterized by its strict interpretation of religious sources and its accepted (Jewish law) and traditions, in opposition to more accommodating values and practices. Its members are ...

all over the world, with a continuous influence through its many Hasidic dynasties

A Hasidic dynasty or Chassidic dynasty is a dynasty led by Hasidic Jewish spiritual leaders known as rebbes, and usually has some or all of the following characteristics:

* Each leader of the dynasty is referred to as an ''ADMOR'' (abbreviation ...

including those of Chabad

Chabad, also known as Lubavitch, Habad and Chabad-Lubavitch (; ; ), is a dynasty in Hasidic Judaism. Belonging to the Haredi (ultra-Orthodox) branch of Orthodox Judaism, it is one of the world's best-known Hasidic movements, as well as one of ...

, Aleksander

Alexander () is a male name of Greek origin. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia who created one of the largest empires in ancient history.

Variants listed here are A ...

, Bobov Bobov may refer to

* Bobov (Hasidic dynasty), a Hasidic community from southern Poland and now headquartered in the neighborhood of Borough Park, in Brooklyn, New York, United States

* Bobov Synagogue (Kraków) in Poland

* Bobov Dol, a town in Bulg ...

, Ger, and Nadvorna.

The Partitions of Poland

In 1742 most of Silesia was annexed by

In 1742 most of Silesia was annexed by Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

as a result of the Silesian Wars

The Silesian Wars () were three wars fought in the mid-18th century between Kingdom of Prussia, Prussia (under King Frederick the Great) and Habsburg monarchy, Habsburg Austria (under Empress Maria Theresa) for control of the Central European ...

. Further disorder and anarchy ensued in Poland in 1764, after the accession to the throne of its last king, Stanislaus II Augustus Poniatowski. Eight years later, triggered by the Confederation of Bar

The Bar Confederation (; 1768–1772) was an association of Polish nobles (''szlachta'') formed at the fortress of Bar in Podolia (now Ukraine), in 1768 to defend the internal and external independence of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth a ...

against Russian influence and the pro-Russian king, the outlying provinces of Poland were overrun from all sides by different military forces and divided for the first time by the three neighboring empires, Russia, Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

, and Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

.Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, also referred to as Poland–Lithuania or the First Polish Republic (), was a federation, federative real union between the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania ...

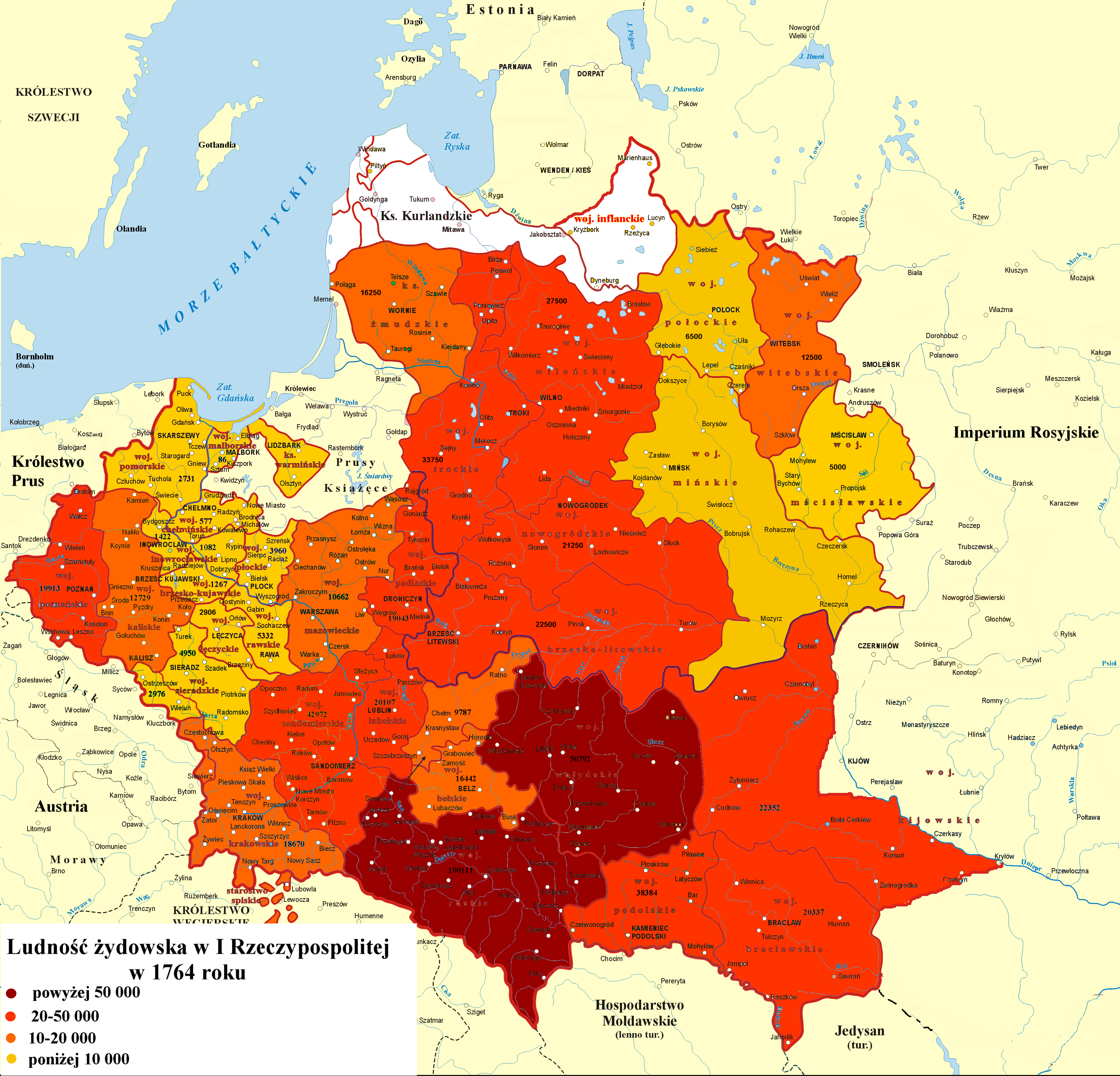

. The worldwide Jewish population at that time was estimated at 1.2 million.

In 1768, the Koliivshchyna

The Koliivshchyna (; ) was a major haidamaky rebellion that broke out in Right-bank Ukraine in June 1768, caused by the dissatisfaction of peasants with the treatment of Orthodox Christians by the Bar Confederation and serfdom, as well as b ...

, a rebellion in Right-bank Ukraine

The Right-bank Ukraine is a historical and territorial name for a part of modern Ukraine on the right (west) bank of the Dnieper River, corresponding to the modern-day oblasts of Vinnytsia, Zhytomyr, Kirovohrad, as well as the western parts o ...

west of the Dnieper

The Dnieper or Dnepr ( ), also called Dnipro ( ), is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. Approximately long, with ...

in Volhynia

Volhynia or Volynia ( ; see #Names and etymology, below) is a historic region in Central and Eastern Europe, between southeastern Poland, southwestern Belarus, and northwestern Ukraine. The borders of the region are not clearly defined, but in ...

, led to ferocious murders of Polish noblemen, Catholic priests and thousands of Jews by haydamak

The haydamaks, also haidamakas or haidamaky or haidamaks ( ''haidamaka''; ''haidamaky'', from and ) were soldiers of Ukrainian Cossack paramilitary outfits composed of commoners (peasants, craftsmen), and impoverished noblemen in the easter ...

s. Four years later, in 1772, the military Partitions of Poland

The Partitions of Poland were three partition (politics), partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth that took place between 1772 and 1795, toward the end of the 18th century. They ended the existence of the state, resulting in the eli ...

had begun between Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

, Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

, and Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

.

The permanent council established at the insistence of the Russian government (1773–1788) served as the highest administrative tribunal, and occupied itself with the elaboration of a plan that would make practicable the reorganization of Poland on a more rational basis. The progressive elements in Polish society recognized the urgency of popular education as the first step toward reform. The Commission of National Education

The Commission of National Education (, KEN, ) was the central educational authority in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, created by the Sejm and King Stanisław August Poniatowski, Stanisław II August on October 14, 1773. Because of its ...

— the first ministry of education in the world — was established in 1773, and founded numerous new schools while remodelling older ones. Chancellor

Chancellor () is a title of various official positions in the governments of many countries. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the (lattice work screens) of a basilica (court hall), which separa ...