James Scott, 1st Duke Of Monmouth on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth, 1st Duke of Buccleuch, (9 April 1649 – 15 July 1685) was an English nobleman and military officer. Originally called James Crofts or James Fitzroy, he was born in

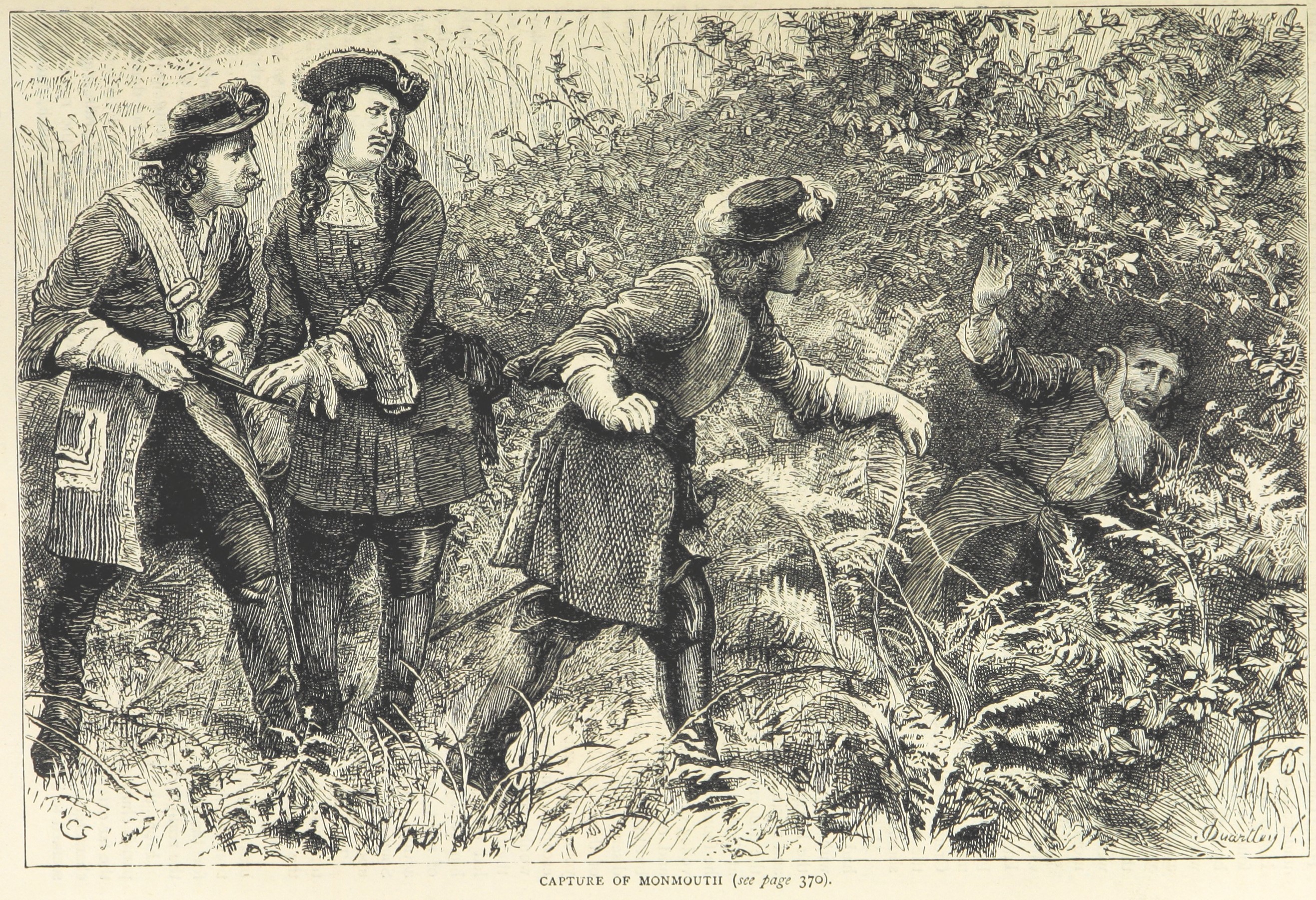

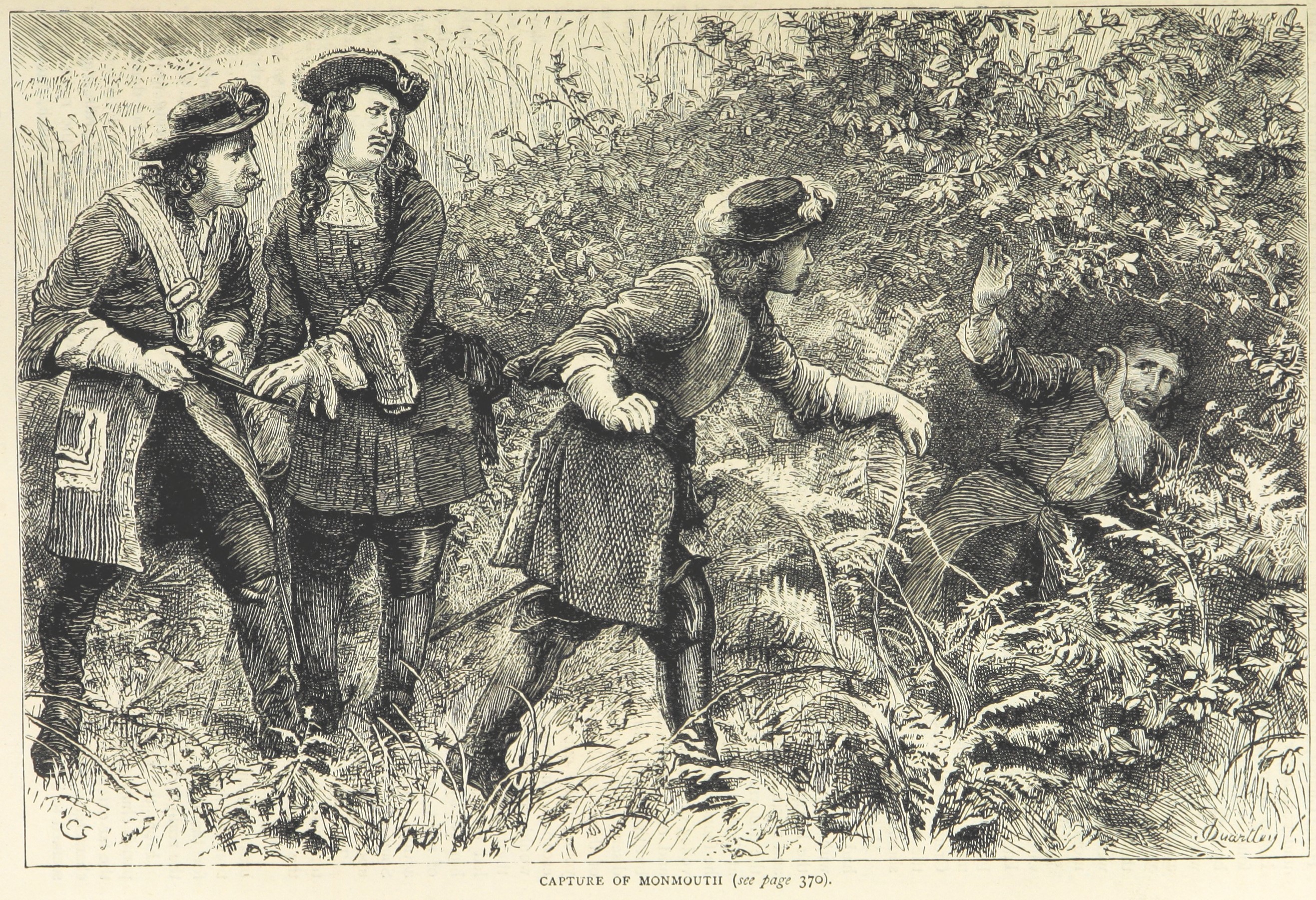

From Woodyates Inn the Duke had gone to Shag's Heath, in the middle of which was a cluster of small farms, called the "Island". Amy Farrant gave information that the fugitives were concealed within the Island. The Duke, accompanied by Busse and Brandenburgher, remained concealed all day, with soldiers surrounding the area and threatening to set fire to the woodland. Brandenburgher deserted him at 1 am, and was later captured and interrogated, and is believed to have given away the Duke's hiding place. The spot was at the north-eastern extremity of the Island, now known as Monmouth's Close, in the manor of Woodlands, the property of the Earl of Shaftesbury. At about 7 am Henry Parkin, a militia soldier and servant of Samuel Rolle, discovered the brown skirt of Monmouth's coat as he lay hidden in a ditch covered with fern and brambles under an ash tree, and called for help. The Duke was seized. Bystanders shouted out "Shoot him! shoot him!", but Sir William Portman happening to be near the spot, immediately rode up, and laid hands on him as his prisoner. Monmouth was then "in the last extremity of hunger and fatigue, with no sustenance but a few raw peas in his pocket. He could not stand, and his appearance was much changed. Since landing in England, the Duke had not had a good night's rest, or eaten one meal in quiet, being perpetually agitated with the cares that attend unfortunate ambition". He had "received no other sustenance than the brook and the field afforded".

The Duke was taken to Holt Lodge, in the parish of Wimborne, about away, the residence of Anthony Etterick, a magistrate who asked the Duke what he would do if released, to which he answered: "that if his horse and arms were but restored to him at the same time, he needed only to ride through the army; and he defied them to take him again". The magistrate ordered him taken to London.

From Woodyates Inn the Duke had gone to Shag's Heath, in the middle of which was a cluster of small farms, called the "Island". Amy Farrant gave information that the fugitives were concealed within the Island. The Duke, accompanied by Busse and Brandenburgher, remained concealed all day, with soldiers surrounding the area and threatening to set fire to the woodland. Brandenburgher deserted him at 1 am, and was later captured and interrogated, and is believed to have given away the Duke's hiding place. The spot was at the north-eastern extremity of the Island, now known as Monmouth's Close, in the manor of Woodlands, the property of the Earl of Shaftesbury. At about 7 am Henry Parkin, a militia soldier and servant of Samuel Rolle, discovered the brown skirt of Monmouth's coat as he lay hidden in a ditch covered with fern and brambles under an ash tree, and called for help. The Duke was seized. Bystanders shouted out "Shoot him! shoot him!", but Sir William Portman happening to be near the spot, immediately rode up, and laid hands on him as his prisoner. Monmouth was then "in the last extremity of hunger and fatigue, with no sustenance but a few raw peas in his pocket. He could not stand, and his appearance was much changed. Since landing in England, the Duke had not had a good night's rest, or eaten one meal in quiet, being perpetually agitated with the cares that attend unfortunate ambition". He had "received no other sustenance than the brook and the field afforded".

The Duke was taken to Holt Lodge, in the parish of Wimborne, about away, the residence of Anthony Etterick, a magistrate who asked the Duke what he would do if released, to which he answered: "that if his horse and arms were but restored to him at the same time, he needed only to ride through the army; and he defied them to take him again". The magistrate ordered him taken to London.

File:Coat of Arms of James Crofts (later Scott), 1st Duke of Monmouth (before 1667).svg

File:Coat of Arms of James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth (after 1667).svg

His marriage to Anne Scott, 1st Duchess of Buccleuch resulted in the birth of six children:

* Charles Scott, Earl of Doncaster (24 August 1672 – 9 February 1673/1674)

* James Scott, Earl of Dalkeith (23 May 1674 – 14 March 1705). He was married on 2 January 1693/1694 to Henrietta Hyde, daughter of Laurence Hyde, 1st Earl of Rochester. They were parents to Francis Scott, 2nd Duke of Buccleuch.

* Lady Anne Scott (17 February 1675 – 13 August 1685)

* Henry Scott, 1st Earl of Deloraine (1676 – 25 December 1730)

* Francis Scott (died an infant; buried 8 December 1679)

* Lady Charlotte Scott (died an infant; buried 5 September 1683)

His affair with his

His marriage to Anne Scott, 1st Duchess of Buccleuch resulted in the birth of six children:

* Charles Scott, Earl of Doncaster (24 August 1672 – 9 February 1673/1674)

* James Scott, Earl of Dalkeith (23 May 1674 – 14 March 1705). He was married on 2 January 1693/1694 to Henrietta Hyde, daughter of Laurence Hyde, 1st Earl of Rochester. They were parents to Francis Scott, 2nd Duke of Buccleuch.

* Lady Anne Scott (17 February 1675 – 13 August 1685)

* Henry Scott, 1st Earl of Deloraine (1676 – 25 December 1730)

* Francis Scott (died an infant; buried 8 December 1679)

* Lady Charlotte Scott (died an infant; buried 5 September 1683)

His affair with his

Rotterdam

Rotterdam ( , ; ; ) is the second-largest List of cities in the Netherlands by province, city in the Netherlands after the national capital of Amsterdam. It is in the Provinces of the Netherlands, province of South Holland, part of the North S ...

in the Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

, the eldest illegitimate

Legitimacy, in traditional Western common law, is the status of a child born to parents who are legally married to each other, and of a child conceived before the parents obtain a legal divorce.

Conversely, ''illegitimacy'', also known as ''b ...

son of Charles II of England

Charles II (29 May 1630 – 6 February 1685) was King of Scotland from 1649 until 1651 and King of England, Scotland, and King of Ireland, Ireland from the 1660 Restoration of the monarchy until his death in 1685.

Charles II was the eldest su ...

with his mistress Lucy Walter.

The Duke of Monmouth served in the Second Anglo-Dutch War

The Second Anglo-Dutch War, began on 4 March 1665, and concluded with the signing of the Treaty of Breda (1667), Treaty of Breda on 31 July 1667. It was one in a series of Anglo-Dutch Wars, naval wars between Kingdom of England, England and the D ...

and commanded English troops taking part in the Third Anglo-Dutch War

The Third Anglo-Dutch War, began on 27 March 1672, and concluded on 19 February 1674. A naval conflict between the Dutch Republic and England, in alliance with France, it is considered a related conflict of the wider 1672 to 1678 Franco-Dutch W ...

before commanding the Anglo-Dutch brigade fighting in the Franco-Dutch War

The Franco-Dutch War, 1672 to 1678, was primarily fought by Kingdom of France, France and the Dutch Republic, with both sides backed at different times by a variety of allies. Related conflicts include the 1672 to 1674 Third Anglo-Dutch War and ...

. He led the unsuccessful Monmouth Rebellion

The Monmouth Rebellion in June 1685 was an attempt to depose James II of England, James II, who in February had succeeded his brother Charles II of England, Charles II as king of Kingdom of England, England, Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland and ...

in 1685, an attempt to depose his uncle King James II and VII

James II and VII (14 October 1633 – 16 September 1701) was King of England and Monarchy of Ireland, Ireland as James II and King of Scotland as James VII from the death of his elder brother, Charles II of England, Charles II, on 6 February 1 ...

. After one of his officers declared Monmouth the legitimate king in the town of Taunton

Taunton () is the county town of Somerset, England. It is a market town and has a Minster (church), minster church. Its population in 2011 was 64,621. Its thousand-year history includes a 10th-century priory, monastic foundation, owned by the ...

in Somerset, Monmouth attempted to capitalise on his Protestantism

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

and his position as the son of Charles II, in opposition to James, who had become a Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

. The rebellion failed, and Monmouth was beheaded

Decapitation is the total separation of the head from the body. Such an injury is invariably fatal to humans and all vertebrate animals, since it deprives the brain of oxygenated blood by way of severing through the jugular vein and common c ...

for treason on 15 July 1685.

Biography

Parentage and early life

Charles, Prince of Wales

Charles III (Charles Philip Arthur George; born 14 November 1948) is King of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth realms.

Charles was born at Buckingham Palace during the reign of his maternal grandfather, King George VI, a ...

(later becoming King Charles II), moved to The Hague

The Hague ( ) is the capital city of the South Holland province of the Netherlands. With a population of over half a million, it is the third-largest city in the Netherlands. Situated on the west coast facing the North Sea, The Hague is the c ...

in 1648, during the Second English Civil War

The Second English Civil War took place between February and August 1648 in Kingdom of England, England and Wales. It forms part of the series of conflicts known collectively as the 1639–1653 Wars of the Three Kingdoms, which include the 164 ...

, where his sister Mary and his brother-in-law William II, Prince of Orange

William II (Dutch language, Dutch: ''Willem II''; 27 May 1626 – 6 November 1650) was sovereign Prince of Orange and Stadtholder of County of Holland, Holland, County of Zeeland, Zeeland, Lordship of Utrecht, Utrecht, Guelders, Lordship of Ove ...

, were based. The French relatives of Charles' mother, Queen Henrietta Maria

Henrietta Maria of France ( French: ''Henriette Marie''; 25 November 1609 – 10 September 1669) was Queen of England, Scotland and Ireland from her marriage to King Charles I on 13 June 1625 until his execution on 30 January 1649. She was ...

, had invited Charles to wait out the war in France with the Queen, but he opted for the Netherlands, as he believed there was more support to be gained for the cause of his father, King Charles I, in the Netherlands than in France. During the summer of 1648, the Prince of Wales became captivated by Lucy Walter, who was in The Hague for a short visit. The lovers were only eighteen, and she is often spoken of as his first mistress, though he may have begun having affairs as early as 1646. Their son James was born in Rotterdam

Rotterdam ( , ; ; ) is the second-largest List of cities in the Netherlands by province, city in the Netherlands after the national capital of Amsterdam. It is in the Provinces of the Netherlands, province of South Holland, part of the North S ...

in the Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

on 9 April 1649, and spent his early years in Schiedam

Schiedam () is a large town and municipality in the west of the Netherlands. It is located in the Rotterdam–The Hague metropolitan area, west of the city Rotterdam, east of the town Vlaardingen and south of the city Delft. In the south, Schi ...

.

Research by Hugh Noel Williams suggests that Charles had not arrived in The Hague

The Hague ( ) is the capital city of the South Holland province of the Netherlands. With a population of over half a million, it is the third-largest city in the Netherlands. Situated on the west coast facing the North Sea, The Hague is the c ...

until the middle of September 1648 – seven months before the child's birth, and that he had only met Lucy in July. It was later rumoured that in the summer of 1648 Lucy had been the mistress

Mistress is the feminine form of the English word "master" (''master'' + ''-ess'') and may refer to:

Romance and relationships

* Mistress (lover), a female lover of a married man

** Royal mistress

* Maîtresse-en-titre, official mistress of a ...

of Colonel Robert Sidney, a younger son of the Earl of Leicester

Earl of Leicester is a title that has been created seven times. The first title was granted during the 12th century in the Peerage of England. The current title is in the Peerage of the United Kingdom and was created in 1837.

History

Earl ...

. As Charles had no legitimate surviving children, his younger brother James, Duke of York

James II and VII (14 October 1633 – 16 September 1701) was King of England and Monarchy of Ireland, Ireland as James II and King of Scotland as James VII from the death of his elder brother, Charles II of England, Charles II, on 6 February 1 ...

, was next in line to the throne. When the boy grew up, those loyal to the Duke of York spread rumours about the young James' resemblance to Sidney. These voices may have been encouraged by the Duke of York himself, who wished to prevent any of the fourteen royal bastard

A royal bastard is a child of a reigning monarch born out of wedlock. The king might have a child with a Mistress (lover), mistress, or the legitimacy of a marriage might be questioned for reasons concerning succession.

Notable royal bastards in ...

s his brother acknowledged from gaining support in the succession. In 2012, a DNA test of Monmouth's patrilineal descendant the 10th Duke of Buccleuch showed that he shared the same Y chromosome

The Y chromosome is one of two sex chromosomes in therian mammals and other organisms. Along with the X chromosome, it is part of the XY sex-determination system, in which the Y is the sex-determining chromosome because the presence of the ...

as a distant Stuart cousin; this is evidence that Charles II was indeed Monmouth's father.

James had a younger sister or half-sister, Mary Crofts, whose father may have been Lord Taaffe. Mary later married the Irishman William Sarsfield, thus becoming the sister-in-law of the Jacobite general Patrick Sarsfield

Patrick Sarsfield, 1st Earl of Lucan ( 1655 – 21 August 1693) was an Irish army officer. Killed at Battle of Landen, Landen in 1693 while serving in the French Royal Army, he is now best remembered as an Irish patriot and military hero.

Born ...

.

As an illegitimate

Legitimacy, in traditional Western common law, is the status of a child born to parents who are legally married to each other, and of a child conceived before the parents obtain a legal divorce.

Conversely, ''illegitimacy'', also known as ''b ...

son, James was ineligible to succeed to the English or Scottish thrones, unless he could prove rumours that his parents had married secretly. He came to maintain that his parents were married and that he possessed evidence of their marriage, but he never produced it. King Charles II testified in writing to his Privy Council that he had never been married to anyone except his queen consort

A queen consort is the wife of a reigning king, and usually shares her spouse's social Imperial, royal and noble ranks, rank and status. She holds the feminine equivalent of the king's monarchical titles and may be crowned and anointed, but hi ...

, Catherine of Braganza

Catherine of Braganza (; 25 November 1638 – 31 December 1705) was List of English royal consorts, Queen of England, List of Scottish royal consorts, Scotland and Ireland during her marriage to Charles II of England, King Charles II, which la ...

.

In March 1658, young James was kidnapped by one of the King's men, sent to Paris, and placed in the care of William Crofts, 1st Baron Crofts

William Crofts, 1st Baron Crofts (c.1611–1677) was an English baron and Gentleman of the Bedchamber to Charles II of England, Charles II.

Life

He was the son of Henry Crofts, Sir Henry Crofts, MP, of Little Saxham, Suffolk.

He moved to cou ...

, whose surname he took. He briefly attended a school in Familly.

Officer and commander

On 14 February 1663, almost 14 years old, shortly after having been brought to England, James was created Duke of Monmouth, with the subsidiary titles of Earl of Doncaster and Baron Scott of Tynedale, all three in thePeerage of England

The Peerage of England comprises all peerages created in the Kingdom of England before the Act of Union in 1707. From that year, the Peerages of England and Scotland were closed to new creations, and new peers were created in a single Peerag ...

, and, on 28 March 1663, he was appointed a Knight of the Garter

The Most Noble Order of the Garter is an order of chivalry founded by Edward III of England in 1348. The most senior order of knighthood in the Orders, decorations, and medals of the United Kingdom, British honours system, it is outranked in ...

.

On 20 April 1663, just days after his 14th birthday, the Duke of Monmouth was married to the heiress Anne Scott, 4th Countess of Buccleuch. He took his wife's surname upon marriage. The day after his marriage, the couple were made Duke and Duchess of Buccleuch, Earl and Countess of Dalkeith, and Lord and Lady Scott of Whitchester and Eskdale in the Peerage of Scotland

The Peerage of Scotland (; ) is one of the five divisions of peerages in the United Kingdom and for those peers created by the King of Scots before 1707. Following that year's Treaty of Union 1707, Treaty of Union, the Kingdom of Scots and the ...

. The Duke of Monmouth was popular, particularly for his Protestantism

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

. The King's official heir presumptive

An heir presumptive is the person entitled to inherit a throne, peerage, or other hereditary honour, but whose position can be displaced by the birth of a person with a better claim to the position in question. This is in contrast to an heir app ...

, James, Duke of York, had openly converted to Roman Catholicism

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

.

In 1665, at the age of 16, Monmouth served in the English fleet under his uncle, the Duke of York, in the Second Anglo-Dutch War

The Second Anglo-Dutch War, began on 4 March 1665, and concluded with the signing of the Treaty of Breda (1667), Treaty of Breda on 31 July 1667. It was one in a series of Anglo-Dutch Wars, naval wars between Kingdom of England, England and the D ...

. In June 1666, he returned to England to become captain of a troop of cavalry. On 16 September 1668 he was made colonel of the His Majesty's Own Troop of Horse Guards. He acquired Moor Park in Hertfordshire in April 1670. Following the death in 1670, without a male heir, of Josceline Percy, 11th Earl of Northumberland, the earl's estates reverted to the Crown. King Charles II awarded the estates to Monmouth. The Countess of Northumberland successfully sued for the estates to be returned to the late Earl's only daughter and sole heiress, Lady Elizabeth Percy (1667–1722).

At the outbreak of the Third Anglo-Dutch War

The Third Anglo-Dutch War, began on 27 March 1672, and concluded on 19 February 1674. A naval conflict between the Dutch Republic and England, in alliance with France, it is considered a related conflict of the wider 1672 to 1678 Franco-Dutch W ...

in 1672, a brigade of 6,000 English and Scottish troops was sent to serve as part of the French army (in return for money paid to King Charles), with Monmouth as its commander. He became Lord Lieutenant of the East Riding of Yorkshire

This is a list of people who have served as Lord Lieutenant for the East Riding of Yorkshire. The office was established after the English Restoration in 1660, when a Lord Lieutenant was appointed for each Riding of Yorkshire. Since 1721, all Lor ...

and Governor of Kingston-upon-Hull in April 1673. In the campaign of 1673 and in particular at the Siege of Maastricht that June, Monmouth gained a considerable reputation as one of Britain's finest soldiers. He was reported to be replacing Marshal Schomberg as commander of England's Zealand Expedition, but this did not happen.

In 1674, Monmouth became Chancellor of Cambridge University and Master of the Horse

Master of the Horse is an official position in several European nations. It was more common when most countries in Europe were monarchies, and is of varying prominence today.

(ancient Rome)

The original Master of the Horse () in the Roman Rep ...

, and King Charles II directed that all military orders should be brought first to Monmouth for examination, thus giving him effective command of the forces; his responsibilities included the movement of troops and the suppression of riots. In March 1677, he also became Lord Lieutenant of Staffordshire.

In 1678, Monmouth was the commander of the Anglo-Dutch brigade, now fighting for the United Provinces against the French, and he distinguished himself at the Battle of Saint-Denis in August that year during the Franco-Dutch War

The Franco-Dutch War, 1672 to 1678, was primarily fought by Kingdom of France, France and the Dutch Republic, with both sides backed at different times by a variety of allies. Related conflicts include the 1672 to 1674 Third Anglo-Dutch War and ...

, further increasing his reputation. The following year, after his return to Britain, he commanded the small army raised to put down the rebellion of the Scottish Covenanter

Covenanters were members of a 17th-century Scottish religious and political movement, who supported a Presbyterian Church of Scotland and the primacy of its leaders in religious affairs. It originated in disputes with James VI and his son C ...

s and despite being heavily outnumbered, he decisively defeated the (admittedly poorly equipped) Covenanter rebels at the Battle of Bothwell Bridge

The Battle of Bothwell Bridge, or Bothwell Brig' took place on 22 June 1679. It was fought between government troops and militant Presbyterian Covenanters, and signalled the end of their brief rebellion. The battle took place at the bridge ove ...

on 22 June 1679.

Exile and rebellion

During theExclusion Crisis

The Exclusion Crisis ran from 1679 until 1681 in the reign of King Charles II of England, Scotland and Ireland. Three Exclusion Bills sought to exclude the King's brother and heir presumptive, James, Duke of York, from the thrones of England, ...

of 1679 to 1681, Monmouth attracted support as successor to the throne. Charles's heir, his brother, the Duke of York, was, as a Catholic, deeply unpopular and a bill was put before parliament excluding him from the succession. Monmouth's supporters hoped that he would be legitimised

Legitimation, legitimization ( US), or legitimisation ( UK) is the act of providing legitimacy. Legitimation in the social sciences refers to the process whereby an act, process, or ideology becomes legitimate by its attachment to norms and val ...

and become Charles's Protestant successor instead. However, the king was adamant in his opposition to changing the succession and prevented the bill from passing by dissolving parliament in May 1679. As Monmouth's popularity with the masses increased, he was obliged by his father to go into exile in the Dutch United Provinces in September 1679. Following the discovery of the so-called Rye House Plot

The Rye House Plot of 1683 was a plan to assassinate King Charles II of England and his brother (and heir to the throne) James, Duke of York. The royal party went from Westminster to Newmarket to see horse races and were expected to make the r ...

in 1683, which aimed to assassinate both Charles II and his brother James, Monmouth, who had been encouraged by his supporters to assert his right to the throne, was identified as a conspirator.

On King Charles II's death in February 1685, Monmouth led the Monmouth Rebellion, landing with three ships at Lyme Regis

Lyme Regis ( ) is a town in west Dorset, England, west of Dorchester, Dorset, Dorchester and east of Exeter. Sometimes dubbed the "Pearl of Dorset", it lies by the English Channel at the Dorset–Devon border. It has noted fossils in cliffs and ...

in Dorset in early June 1685, in an attempt to take the throne from his uncle, James II and VII

James II and VII (14 October 1633 – 16 September 1701) was King of England and Monarchy of Ireland, Ireland as James II and King of Scotland as James VII from the death of his elder brother, Charles II of England, Charles II, on 6 February 1 ...

. He published a "Declaration for the defence and vindication of the protestant religion and of the laws, rights and privileges of England from the invasion made upon them, and for delivering the Kingdom from the usurpation and tyranny of us by the name of James, Duke of York": King James responded to this by issuing an order for the publishers and distributors of the paper to be arrested. Monmouth declared himself as the rightful king at various places along the route including Axminster

Axminster is a market town and civil parishes in England, civil parish on the eastern border of the county of Devon in England. It is from the county town of Exeter. The town is built on a hill overlooking the River Axe, Devon, River Axe which ...

, Chard

Chard (; '' Beta vulgaris'' subsp. ''vulgaris'', Cicla Group and Flavescens Group) is a green leafy vegetable. In the cultivars of the Flavescens Group, or Swiss chard, the leaf stalks are large and often prepared separately from the leaf b ...

, Ilminster and Taunton

Taunton () is the county town of Somerset, England. It is a market town and has a Minster (church), minster church. Its population in 2011 was 64,621. Its thousand-year history includes a 10th-century priory, monastic foundation, owned by the ...

. The two armies met at the Battle of Sedgemoor

The Battle of Sedgemoor was the last and decisive engagement between forces loyal to James II and rebels led by the Duke of Monmouth during the Monmouth rebellion, fought on 6 July 1685, and took place at Westonzoyland near Bridgwater in S ...

on 6 July 1685, the last clear-cut pitched battle

A pitched battle or set-piece battle is a battle in which opposing forces each anticipate the setting of the battle, and each chooses to commit to it. Either side may have the option to disengage before the battle starts or shortly thereafter. A ...

on open ground between two military forces fought on English soil: Monmouth's makeshift force could not compete with the regular army, and was soundly defeated.

Capture

Following the battle a reward of £5,000 was offered for his capture.Roberts, p. 109 On 8 July 1685, Monmouth was captured and arrested near Ringwood in Hampshire, by tradition "in a field of peas". The events surrounding his capture are described by George Roberts in '' Tait's Edinburgh Magazine''. When the Duke had left his horse at Woodyates Inn, he exchanged clothes with a shepherd, who was soon discovered by local loyalists and interrogated. Dogs were then put onto the Duke's scent. Monmouth dropped his gold snuff box, full of gold pieces, in a pea field, where it was afterwards found. From Woodyates Inn the Duke had gone to Shag's Heath, in the middle of which was a cluster of small farms, called the "Island". Amy Farrant gave information that the fugitives were concealed within the Island. The Duke, accompanied by Busse and Brandenburgher, remained concealed all day, with soldiers surrounding the area and threatening to set fire to the woodland. Brandenburgher deserted him at 1 am, and was later captured and interrogated, and is believed to have given away the Duke's hiding place. The spot was at the north-eastern extremity of the Island, now known as Monmouth's Close, in the manor of Woodlands, the property of the Earl of Shaftesbury. At about 7 am Henry Parkin, a militia soldier and servant of Samuel Rolle, discovered the brown skirt of Monmouth's coat as he lay hidden in a ditch covered with fern and brambles under an ash tree, and called for help. The Duke was seized. Bystanders shouted out "Shoot him! shoot him!", but Sir William Portman happening to be near the spot, immediately rode up, and laid hands on him as his prisoner. Monmouth was then "in the last extremity of hunger and fatigue, with no sustenance but a few raw peas in his pocket. He could not stand, and his appearance was much changed. Since landing in England, the Duke had not had a good night's rest, or eaten one meal in quiet, being perpetually agitated with the cares that attend unfortunate ambition". He had "received no other sustenance than the brook and the field afforded".

The Duke was taken to Holt Lodge, in the parish of Wimborne, about away, the residence of Anthony Etterick, a magistrate who asked the Duke what he would do if released, to which he answered: "that if his horse and arms were but restored to him at the same time, he needed only to ride through the army; and he defied them to take him again". The magistrate ordered him taken to London.

From Woodyates Inn the Duke had gone to Shag's Heath, in the middle of which was a cluster of small farms, called the "Island". Amy Farrant gave information that the fugitives were concealed within the Island. The Duke, accompanied by Busse and Brandenburgher, remained concealed all day, with soldiers surrounding the area and threatening to set fire to the woodland. Brandenburgher deserted him at 1 am, and was later captured and interrogated, and is believed to have given away the Duke's hiding place. The spot was at the north-eastern extremity of the Island, now known as Monmouth's Close, in the manor of Woodlands, the property of the Earl of Shaftesbury. At about 7 am Henry Parkin, a militia soldier and servant of Samuel Rolle, discovered the brown skirt of Monmouth's coat as he lay hidden in a ditch covered with fern and brambles under an ash tree, and called for help. The Duke was seized. Bystanders shouted out "Shoot him! shoot him!", but Sir William Portman happening to be near the spot, immediately rode up, and laid hands on him as his prisoner. Monmouth was then "in the last extremity of hunger and fatigue, with no sustenance but a few raw peas in his pocket. He could not stand, and his appearance was much changed. Since landing in England, the Duke had not had a good night's rest, or eaten one meal in quiet, being perpetually agitated with the cares that attend unfortunate ambition". He had "received no other sustenance than the brook and the field afforded".

The Duke was taken to Holt Lodge, in the parish of Wimborne, about away, the residence of Anthony Etterick, a magistrate who asked the Duke what he would do if released, to which he answered: "that if his horse and arms were but restored to him at the same time, he needed only to ride through the army; and he defied them to take him again". The magistrate ordered him taken to London.

Attainder and execution

Following Monmouth's capture,Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

passed an Act of Attainder, 1 Ja. 2. c. 2:

The King took the unusual step of allowing his nephew an audience, despite having no intention of extending a pardon

A pardon is a government decision to allow a person to be relieved of some or all of the legal consequences resulting from a criminal conviction. A pardon may be granted before or after conviction for the crime, depending on the laws of the j ...

to him, thus breaking with a longstanding tradition that the King would give an audience only when he intended to show clemency. The prisoner unsuccessfully implored his mercy and even offered to convert to Catholicism

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

, but to no avail. The King, disgusted by his abject behaviour, coldly told him to prepare to die, and later remarked that Monmouth "did not behave as well as I expected". Numerous pleas for mercy were addressed to the King, but he ignored them all, even that of his sister-in-law, the Dowager Queen Catherine.

Monmouth was beheaded

Decapitation is the total separation of the head from the body. Such an injury is invariably fatal to humans and all vertebrate animals, since it deprives the brain of oxygenated blood by way of severing through the jugular vein and common c ...

by Jack Ketch on 15 July 1685, on Tower Hill

Tower Hill is the area surrounding the Tower of London in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is infamous for the public execution of high status prisoners from the late 14th to the mid 18th century. The execution site on the higher gro ...

. Shortly beforehand, Bishops Turner

Turner may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Turner (surname), a common surname, including a list of people and fictional characters with the name

* Turner (given name), a list of people with the given name

*One who uses a lathe for tur ...

of Ely and Ken of Bath and Wells visited the Duke to prepare him for eternity, but withheld the Eucharist

The Eucharist ( ; from , ), also called Holy Communion, the Blessed Sacrament or the Lord's Supper, is a Christianity, Christian Rite (Christianity), rite, considered a sacrament in most churches and an Ordinance (Christianity), ordinance in ...

, for the condemned man refused to acknowledge that either his rebellion or his relationship with Lady Wentworth had been sin

In religious context, sin is a transgression against divine law or a law of the deities. Each culture has its own interpretation of what it means to commit a sin. While sins are generally considered actions, any thought, word, or act considered ...

ful. It is said that before laying his head on the block, Monmouth specifically bade Ketch finish him at one blow, saying he had mauled others before. Disconcerted, Ketch did indeed inflict multiple blows with his axe, the prisoner rising up reproachfully the while – a ghastly sight that shocked the witnesses, drawing forth execrations and groans. Some say a knife was at last employed to sever the head from the twitching body. Sources vary; some claim eight blows, the official Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic citadel and castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London, England. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamle ...

fact sheet says it took five blows, while Charles Spencer, in his book ''Blenheim'', puts it at seven.

Monmouth was buried in the Church of St Peter ad Vincula

The Chapel Royal of St Peter ad Vincula ("St Peter in chains") is a Chapel Royal and the former parish church of the Tower of London. The chapel's name refers to the story of Saint Peter's imprisonment under Herod Agrippa in Jerusalem. Situate ...

in the Tower of London. His Dukedom was forfeited, but his subsidiary titles, Earl of Doncaster and Baron Scott of Tindale, were restored by King George II on 23 March 1743 to his grandson Francis Scott, 2nd Duke of Buccleuch (1695–1751).

Popular legends

According to legend, a portrait was painted of Monmouth after his execution: the tradition states that it was realised after the execution that there was no officialportrait

A portrait is a painting, photograph, sculpture, or other artistic representation of a person, in which the face is always predominant. In arts, a portrait may be represented as half body and even full body. If the subject in full body better r ...

of the Duke, so his body was exhumed, the head stitched back on, and it was sat for its portrait to be painted. However, there are at least two formal portraits of Monmouth tentatively dated to before his death currently in the National Portrait Gallery National Portrait Gallery may refer to:

* National Portrait Gallery (Australia), in Canberra

* National Portrait Gallery (Sweden), in Mariefred

*National Portrait Gallery (United States), in Washington, D.C.

*National Portrait Gallery, London

...

in London, and another painting once identified with Monmouth that shows a sleeping or dead man that could have given rise to the story.

One of the many theories about the identity of the Man in the Iron Mask is that he was Monmouth: the theory is that someone else was executed in his place, and James II arranged for Monmouth to be taken to France and put in the custody of his cousin Louis XIV of France

LouisXIV (Louis-Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was King of France from 1643 until his death in 1715. His verified reign of 72 years and 110 days is the List of longest-reign ...

.

Henry Purcell

Henry Purcell (, rare: ; September 1659 – 21 November 1695) was an English composer of Baroque music, most remembered for his more than 100 songs; a tragic opera, Dido and Aeneas, ''Dido and Aeneas''; and his incidental music to a version o ...

set to music ( Z. 481) a satirical poem by an unidentified author, ridiculing Monmouth and his parentage:

Arms

James Scott's first coat of arms was initially granted in 1663 at the same time he was created Duke of Monmouth: Quarterly, 1st and 4th, ''Ermine, on a Pile gules three Lions passant guardant or;'' 2nd and 3rd: ''Or, within a double Tressure flory counterflory gules, on an Inescutcheon azure, three Fleurs-de-Lys gold.'' Crest: ''Upon a Chapeau gules turned up ermine, a Dragon passant or gorged with a Crown having a Chain gules.'' Supporters: Dexter, ''a Unicorn argent, armed, maned and unguled or, gorged with a Crown having a Chain gules affixed thereto:'' Sinister,'' a Hart argent, attired and unguled or, gorged with a Crown having a Chain gules affixed thereto.'' This version of the arms, which consisted in a creative reorganisation of the Royal Arms, drew numerous complaints as it did not include any marker to signify his illegitimacy, and rumours that Charles might attempt to legitimise James started to spread. Four years later, after James' marriage, and with Charles' growing realisation that he would not legitimise him, a new design was granted: ''the Arms of King Charles II debruised by a baton sinister Argent;'' Aninescutcheon

In heraldry, an inescutcheon is a smaller Escutcheon (heraldry), escutcheon that is placed within or superimposed over the main shield of a coat of arms, similar to a Charge (heraldry), charge. This may be used in the following cases:

* as a sim ...

of Scott was added on top:'' Or, on a Bend azure a Mullet of six points between two Crescents of the field.'' To show the importance of James' marriage to Anne Scott, which he had married shortly after receiving his original arms. The Crest and Supporters from his previous arms were kept.

Children

His marriage to Anne Scott, 1st Duchess of Buccleuch resulted in the birth of six children:

* Charles Scott, Earl of Doncaster (24 August 1672 – 9 February 1673/1674)

* James Scott, Earl of Dalkeith (23 May 1674 – 14 March 1705). He was married on 2 January 1693/1694 to Henrietta Hyde, daughter of Laurence Hyde, 1st Earl of Rochester. They were parents to Francis Scott, 2nd Duke of Buccleuch.

* Lady Anne Scott (17 February 1675 – 13 August 1685)

* Henry Scott, 1st Earl of Deloraine (1676 – 25 December 1730)

* Francis Scott (died an infant; buried 8 December 1679)

* Lady Charlotte Scott (died an infant; buried 5 September 1683)

His affair with his

His marriage to Anne Scott, 1st Duchess of Buccleuch resulted in the birth of six children:

* Charles Scott, Earl of Doncaster (24 August 1672 – 9 February 1673/1674)

* James Scott, Earl of Dalkeith (23 May 1674 – 14 March 1705). He was married on 2 January 1693/1694 to Henrietta Hyde, daughter of Laurence Hyde, 1st Earl of Rochester. They were parents to Francis Scott, 2nd Duke of Buccleuch.

* Lady Anne Scott (17 February 1675 – 13 August 1685)

* Henry Scott, 1st Earl of Deloraine (1676 – 25 December 1730)

* Francis Scott (died an infant; buried 8 December 1679)

* Lady Charlotte Scott (died an infant; buried 5 September 1683)

His affair with his mistress

Mistress is the feminine form of the English word "master" (''master'' + ''-ess'') and may refer to:

Romance and relationships

* Mistress (lover), a female lover of a married man

** Royal mistress

* Maîtresse-en-titre, official mistress of a ...

Eleanor Needham, daughter of Sir Robert Needham of Lambeth

Lambeth () is a district in South London, England, which today also gives its name to the (much larger) London Borough of Lambeth. Lambeth itself was an ancient parish in the county of Surrey. It is situated 1 mile (1.6 km) south of Charin ...

resulted in the birth of three children:

* James Crofts (died March 1732), major-general in the Army.

* Henrietta Crofts ( – 27 February 1730). She was married around 1697 to Charles Paulet, 2nd Duke of Bolton.

* Isabel Crofts (died young)

Toward the end of his life he conducted an affair with Henrietta, Baroness Wentworth.

Family tree

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Monmouth, James Scott, 1st Duke Of 1649 births 1685 deaths 17th-century English nobility 17th-century Scottish peers 17th-century Protestants 17th-century rebels British Life Guards officers Burials at the Church of St Peter ad Vincula Chancellors of the University of Cambridge 101 English generals English Protestants Executed English nobility J James Illegitimate children of Charles II of England Knights of the Garter Lord-lieutenants of Staffordshire Lord-lieutenants of the East Riding of Yorkshire Lords of the Admiralty Members of the Privy Council of England Military personnel from Rotterdam People executed under the Stuarts for treason against England Dukes in the Peerage of England English politicians convicted of crimes People executed by Stuart England by decapitation Executed Dutch people People convicted under a bill of attainder Executions at the Tower of London Pretenders to the English throne Pretenders to the Scottish throne Prisoners in the Tower of London Man in the Iron Mask Monmouth Rebellion Peers of England created by Charles II Peers of Scotland created by Charles II Sons of kings People of the Third Anglo-Dutch War Royal Navy personnel of the Second Anglo-Dutch War