James L. Holloway, Jr. on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

James Lemuel Holloway Jr. (June 20, 1898 – January 11, 1984) was a four-star admiral in the

Holloway assumed command of the battleship , flagship of Battleship Division 7, in November 1944. Under his command, ''Iowa'' took part in attacks on

Holloway assumed command of the battleship , flagship of Battleship Division 7, in November 1944. Under his command, ''Iowa'' took part in attacks on

While directing the navy's demobilization, Holloway also chaired an influential board that laid the foundation for the postwar

While directing the navy's demobilization, Holloway also chaired an influential board that laid the foundation for the postwar

On January 15, 1947, Admiral James L. Holloway Jr. became the 35th

On January 15, 1947, Admiral James L. Holloway Jr. became the 35th

At 48, Holloway was the youngest superintendent in fifty years, having been handpicked by

Throughout his career, Holloway vigorously defended the Naval Academy's special role as the preeminent source of naval officers in the U.S.

As chairman of the Holloway Board, Holloway helped fend off proposals to downgrade the importance of Annapolis by converting the Academy into a two-year postgraduate school for students who had already completed at least three years of college, a plan that would double the number of officers that could be produced by halving the time spent at the Academy. The Holloway Board also rejected another proposal, popular among local politicians, to expand enrollment by establishing satellite Naval Academies in other coastal cities. "It was deemed wiser that the Naval Academy at Annapolis, with its history and traditions, be the single institution representing...the ultimate in personal and professional standards, and a principal binding force...in the Navy as a whole."

In January 1947, less than two weeks after becoming Academy superintendent, Holloway rebuffed a proposal by Army Chief of Staff

Throughout his career, Holloway vigorously defended the Naval Academy's special role as the preeminent source of naval officers in the U.S.

As chairman of the Holloway Board, Holloway helped fend off proposals to downgrade the importance of Annapolis by converting the Academy into a two-year postgraduate school for students who had already completed at least three years of college, a plan that would double the number of officers that could be produced by halving the time spent at the Academy. The Holloway Board also rejected another proposal, popular among local politicians, to expand enrollment by establishing satellite Naval Academies in other coastal cities. "It was deemed wiser that the Naval Academy at Annapolis, with its history and traditions, be the single institution representing...the ultimate in personal and professional standards, and a principal binding force...in the Navy as a whole."

In January 1947, less than two weeks after becoming Academy superintendent, Holloway rebuffed a proposal by Army Chief of Staff

After completing his tour as superintendent in 1950, Holloway served 30 months as Commander, Battleship-Cruiser Force, Atlantic (COMBATCRULANT) before being promoted to vice admiral on February 2, 1953, and appointed chief of the

After completing his tour as superintendent in 1950, Holloway served 30 months as Commander, Battleship-Cruiser Force, Atlantic (COMBATCRULANT) before being promoted to vice admiral on February 2, 1953, and appointed chief of the

Holloway was an early ally of Rear Admiral Hyman G. Rickover, the controversial father of the Navy's nuclear propulsion program. To induce promising

Holloway was an early ally of Rear Admiral Hyman G. Rickover, the controversial father of the Navy's nuclear propulsion program. To induce promising

As CINCNELM, Holloway commanded all U.S. naval forces in Europe, including the Sixth Fleet commanded by Vice Admiral Charles R. Brown. In November 1957, the

At 10:30 a.m. on July 16, as the Marines prepared to move into Beirut, it was discovered that

At 10:30 a.m. on July 16, as the Marines prepared to move into Beirut, it was discovered that

Holloway was relieved as CINCNELM by Admiral Robert L. Dennison in March 1959. Returning to Washington for his well-attended retirement ceremony a month later, Holloway declared that he definitely would not follow the example of other high-ranking military retirees in that he was actually going to retire, not start a second career in business. After his retirement from the Navy, he served as Governor of the United States Naval Home in

Holloway was relieved as CINCNELM by Admiral Robert L. Dennison in March 1959. Returning to Washington for his well-attended retirement ceremony a month later, Holloway declared that he definitely would not follow the example of other high-ranking military retirees in that he was actually going to retire, not start a second career in business. After his retirement from the Navy, he served as Governor of the United States Naval Home in

Holloway married the former Jean Gordon Hagood, daughter of

Holloway married the former Jean Gordon Hagood, daughter of

/ref> Holloway's father, James Lemuel Holloway Sr., served as superintendent of schools in

/ref> Holloway recorded an oral history that is archived at the

James L. Holloway Papers

at Syracuse University

* (includes photo of Holloway and Ambassador McClintock negotiating with General Chehab at the roadblock near Beirut) {{DEFAULTSORT:Holloway, James L. Jr. United States Navy admirals United States Naval Academy alumni 1898 births 1984 deaths People from Fort Smith, Arkansas Military personnel from Arkansas Deaths from aortic aneurysm Burials at the United States Naval Academy Cemetery Recipients of the Legion of Merit Superintendents of the United States Naval Academy 20th-century American academics United States Navy personnel of World War I

United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

who served as superintendent of the United States Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy (USNA, Navy, or Annapolis) is a United States Service academies, federal service academy in Annapolis, Maryland. It was established on 10 October 1845 during the tenure of George Bancroft as United States Secre ...

from 1947 to 1950; as Chief of Naval Personnel

The Chief of Naval Personnel (CNP) is responsible for overall personnel readiness and manpower allocation for the United States Navy. The CNP serves in an additional duty capacity as the Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Personnel, Manpower, ...

from 1953 to 1957; and as commander in chief of all United States naval forces in the eastern Atlantic and Mediterranean from 1957 to 1959, in which capacity he commanded the 1958 American intervention in Lebanon. As founder of the Holloway Plan, he was responsible for creating the modern Naval Reserve Officer Training Corps

The Naval Reserve Officer Training Corps (NROTC) program is a college-based, commissioned officer training program of the United States Navy and the United States Marine Corps.

Origins

A pilot Naval Reserve unit was established in September 1924 ...

.

Holloway was the father of four-star admiral and Chief of Naval Operations

The chief of naval operations (CNO) is the highest-ranking officer of the United States Navy. The position is a statutory office () held by an Admiral (United States), admiral who is a military adviser and deputy to the United States Secretary ...

Admiral James L. Holloway III. , they are the only father and son to both serve as four-star admirals in the United States Navy while on active duty, as opposed to being promoted to that rank posthumously

Posthumous may refer to:

* Posthumous award, an award, prize or medal granted after the recipient's death

* Posthumous publication, publishing of creative work after the author's death

* Posthumous (album), ''Posthumous'' (album), by Warne Marsh, 1 ...

or at retirement.

Early career

Holloway was born on June 20, 1898, inFort Smith, Arkansas

Fort Smith is the List of municipalities in Arkansas, third-most populous city in Arkansas, United States, and one of the two county seats of Sebastian County, Arkansas, Sebastian County. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the pop ...

, to future centenarian

A centenarian is a person who has reached the age of 100. Because life expectancies at birth worldwide are well below 100, the term is invariably associated with longevity. The United Nations estimated that there were 316,600 living centenarian ...

James Lemuel Holloway and the former Mary George Leaming. In 1904, his family moved to Dallas

Dallas () is a city in the U.S. state of Texas and the most populous city in the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex, the List of Texas metropolitan areas, most populous metropolitan area in Texas and the Metropolitan statistical area, fourth-most ...

, Texas, where he was a varsity football tackle and a member of the debate team at Oak Cliff High School, from which he graduated in 1915. Unable to secure an appointment to the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), commonly known as West Point, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York that educates cadets for service as Officer_(armed_forces)#United_States, comm ...

—his original ambition—Holloway instead passed the entrance examinations for the United States Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy (USNA, Navy, or Annapolis) is a United States Service academies, federal service academy in Annapolis, Maryland. It was established on 10 October 1845 during the tenure of George Bancroft as United States Secre ...

at Annapolis, Maryland

Annapolis ( ) is the capital of the U.S. state of Maryland. It is the county seat of Anne Arundel County and its only incorporated city. Situated on the Chesapeake Bay at the mouth of the Severn River, south of Baltimore and about east ...

, and entered the Naval Academy as a midshipman

A midshipman is an officer of the lowest Military rank#Subordinate/student officer, rank in the Royal Navy, United States Navy, and many Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth navies. Commonwealth countries which use the rank include Royal Cana ...

in 1915. He graduated in June 1918 near the bottom of the accelerated class of 1919, ranked 149th out of 199, and later said he had avoided flunking out of the Academy only because his class graduated early due to World War I. "I knew I would have bilged in mechanics."

World War I

Commissioned ensign on June 7, 1918, Holloway was assigned to the destroyer , operating out ofBrest, France

Brest (; ) is a port, port city in the Finistère department, Brittany (administrative region), Brittany. Located in a sheltered bay not far from the western tip of a peninsula and the western extremity of metropolitan France, Brest is an impor ...

, as part of the destroyer force tasked with anti-submarine patrols against German U-boat

U-boats are Submarine#Military, naval submarines operated by Germany, including during the World War I, First and Second World Wars. The term is an Anglicization#Loanwords, anglicized form of the German word , a shortening of (), though the G ...

s in European waters. He made a poor impression almost immediately. "They never told me about the lack of space on destroyers. My baggage filled the whole wardroom. I was a very unpopular young officer for that." Nevertheless, he was promoted to lieutenant (junior grade) in September.

In January 1919, Holloway was assigned to the battleship , a tour that included duty as aide and flag lieutenant to Rear Admiral Frederick B. Bassett Jr. As the admiral's aide, Holloway visited Brazil

Brazil, officially the Federative Republic of Brazil, is the largest country in South America. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by area, fifth-largest country by area and the List of countries and dependencies by population ...

, Argentina

Argentina, officially the Argentine Republic, is a country in the southern half of South America. It covers an area of , making it the List of South American countries by area, second-largest country in South America after Brazil, the fourt ...

, and Uruguay

Uruguay, officially the Oriental Republic of Uruguay, is a country in South America. It shares borders with Argentina to its west and southwest and Brazil to its north and northeast, while bordering the Río de la Plata to the south and the A ...

when ''Florida'' carried Secretary of State Bainbridge Colby

Bainbridge Colby (December 22, 1869 – April 11, 1950) was an American politician and attorney who was a co-founder of the United States Progressive Party and Woodrow Wilson's last Secretary of State. Colby was a Republican until he helped co-f ...

and his party on a diplomatic cruise to South American and Caribbean ports in 1920.

Inter-war period

In August 1921, Holloway was assigned to destroyer duty, briefly commanding the destroyer before serving as executive officer of the destroyer until June 1922, when he was promoted to full lieutenant and assigned as executive officer of the destroyer for two years of sea duty in the Far East with theAsiatic Fleet

The United States Asiatic Fleet was a fleet of the United States Navy during much of the first half of the 20th century. Before World War II, the fleet patrolled the Philippine Islands. Much of the fleet was destroyed by the Japanese by Februar ...

. Upon his return to the U.S. in July 1924, he served as an instructor at the Naval Academy in the Department of Ordnance and Gunnery from August 1924 to June 1926, under successive superintendents Henry B. Wilson and Louis M. Nulton.

In 1926, Holloway began a two-year tour aboard the battleship , over the course of which he received several departmental commendations for "contribution to gunnery efficiency" and had under his command the highest scoring gun turret

A gun turret (or simply turret) is a mounting platform from which weapons can be fired that affords protection, visibility and ability to turn and aim. A modern gun turret is generally a rotatable weapon mount that houses the crew or mechanis ...

in the Navy, which set a record in target practice that remained unbroken for several years.

From August 1928 to June 1930, Holloway was aide and flag lieutenant on the staff of Rear Admiral Harris Laning, chief of staff of the Battle Fleet

The United States Battle Fleet or Battle Force was part of the organization of the United States Navy from 1922 to 1941.

The General Order of 6 December 1922 organized the United States Fleet, with the Battle Fleet as the Pacific presence. Thi ...

and subsequently Commander Battleship Division Two. He remained Laning's aide for the first two years of the admiral's next assignment as President of the Naval War College

The president of the Naval War College is a flag officer in the United States Navy. The President's House in Newport, Rhode Island is their official residence.

The functions of the president of the Naval War College actually predate the estab ...

in Newport, Rhode Island

Newport is a seaside city on Aquidneck Island in Rhode Island, United States. It is located in Narragansett Bay, approximately southeast of Providence, Rhode Island, Providence, south of Fall River, Massachusetts, south of Boston, and nort ...

, then had duty as assistant gunnery officer aboard the battleship from June 1932 – May 1933. In May 1933, he was again assigned as aide and flag lieutenant to now-Vice Admiral Laning, Commander Cruisers Scouting Force

The Scouting Fleet is an important part of the U.S. Navy, established in 1922 as part of the reorganization of the Navy after World War I. It is one of the four core units of the newly formed "American Fleet", which together with the battle Fleet ...

. He was promoted to lieutenant commander in June.

In June 1934, Holloway began a year in command of the destroyer , flagship of Commander, Destroyer Squadron Three in the Pacific Fleet. "I made a beauty out of the ''Hopkins''. I brought her up in appearance and gunnery. A friend of mine, the first lieutenant of the , helped me. This boy gave me an extra 200 gallons of paint every month. I made her look like a yacht."

Holloway was transferred to the Navy Department in June 1935 for three years of duty with the Gunnery Section of the Fleet Training Division, then was navigator of the battleship from 1938 until July 1939, when he assumed command of the cargo ship and was promoted to the rank of full commander.

World War II

In September 1939, Holloway became chief of staff to Rear Admiral Hayne Ellis, commander of theAtlantic Squadron

The United States Fleet Forces Command (USFFC) is a service component command of the United States Navy that provides naval forces to a wide variety of U.S. forces. The naval resources may be allocated to Combatant Commanders such as United Sta ...

, in which capacity Holloway directed the expansion and deployment of the Atlantic Squadron for Neutrality Patrol

On September 3, 1939, the British and French declarations of war on Germany initiated the Battle of the Atlantic. The United States Navy Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) established a combined air and ship patrol of the United States Atlantic co ...

operations after the outbreak of World War II in Europe.

In October 1940, Holloway was assigned as officer in charge of the gunnery section of the Fleet Training Office in the office of the Chief of Naval Operations, where he was serving at the time of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Empire of Japan on the United States Pacific Fleet at Naval Station Pearl Harbor, its naval base at Pearl Harbor on Oahu, Territory of ...

. "We were busy as bird-dogs in those weeks following the attack. It's hard to describe just how much the workload moved up. We stopped all routine computation of training and competitive exercises that Fleet Training had been responsible for, and we went into expediting production and perfecting the performance of weapons."

In the weeks following the attack, Holloway was one of three duty officer

A duty officer or officer of the day is a worker assigned a position on a regularly rotational basis. While on duty, duty officers attend to administrative tasks and incidents that require attention regardless of the time of day, in addition to t ...

s selected to stand the night watch at the Navy Department, alternating four-hour shifts with Captain Cato D. Glover Jr. and Commander Forrest P. Sherman. "One night, we got a report that there was a dirigible

An airship, dirigible balloon or dirigible is a type of aerostat ( lighter-than-air) aircraft that can navigate through the air flying under its own power. Aerostats use buoyancy from a lifting gas that is less dense than the surrounding ...

off New York. I put out an emergency on the whole East Coast." The supposed enemy airship turned out to be an off-course American blimp, but Holloway's superiors approved his decision anyway. "After what had happened at Pearl Harbor, we went to general quarters

General quarters, battle stations, or action stations is an announcement made aboard a navy, naval warship to signal that all hands (everyone available) aboard a ship must go to battle stations (the positions they are to assume when the ves ...

in case of doubt."

Operation Torch

Holloway had applied for immediate sea duty after the Pearl Harbor attack and on 20 May 1942, he assumed command of Destroyer Squadron Ten (Desron 10), a newly built and newly commissioned member of the Atlantic Fleet. Promoted to captain in June, in November he led Desron 10 in screening the landings atCasablanca

Casablanca (, ) is the largest city in Morocco and the country's economic and business centre. Located on the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coast of the Chaouia (Morocco), Chaouia plain in the central-western part of Morocco, the city has a populatio ...

during the opening stages of Operation Torch

Operation Torch (8–16 November 1942) was an Allies of World War II, Allied invasion of French North Africa during the Second World War. Torch was a compromise operation that met the British objective of securing victory in North Africa whil ...

, the Allied invasion of North Africa. As one of three principal destroyer commanders in this operation, he received a Navy Commendation Ribbon with the following citation: "Holloway prevented the many enemy submarines in the area from delivering effective torpedo fire and, by his aggressive fighting spirit and courageous leadership, contributed materially to the winning of a decisive victory over the enemy."

DD-DE Shakedown Task Force

Having gained a reputation for "unusual capacity for imparting enthusiasm as well as for organization", he was relieved of the command of Desron 10 on 8 April 1943, to lead the new Destroyer and Destroyer Escort (DD-DE) Shakedown Task Force that was being organized atBermuda

Bermuda is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean. The closest land outside the territory is in the American state of North Carolina, about to the west-northwest.

Bermuda is an ...

to systematically work up newly built destroyers and destroyer escorts before they joined the Atlantic Fleet.

Arriving at Bermuda on 13 April aboard the destroyer tender , Holloway quickly established an efficient arena for drilling untrained crews in operations at sea. When newly commissioned ships arrived at Bermuda, their officers and men debarked for training aboard ''Hamul'' and ashore while their vessels underwent inspection and repair by task force staff. Ships then returned to sea to practice tactics and the use of their equipment, in daylight and in darkness, against towed surface targets and "tame" submarines. Task force staff handled all repairs and logistics, freeing commanding officers to focus solely on training their crews.

At first, Holloway's training program only covered destroyer escorts and a few gunboats, but his "Bermuda college" was so successful that it was expanded in September to encompass all newly built destroyers, and would eventually be extended to Canadian and British vessels as well. By the time of his relief on 14 November, 99 destroyer escorts and 20 destroyers had already graduated from the program and 25 other ships were being trained. The shakedown period had been reduced from six to eight weeks of haphazard preparation to only four weeks for destroyer escorts and five weeks for destroyers, with vastly superior quality of training. For this success, Holloway was awarded the Legion of Merit

The Legion of Merit (LOM) is a Awards and decorations of the United States military, military award of the United States Armed Forces that is given for exceptionally meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding services and achievemen ...

, whose citation commended his having "built up an efficient organization, turning over to the Fleet competent seagoing vessels and thoroughly indoctrinated personnel. His conspicuous success in fulfilling this important assignment and his skill in collaboration with other commands have contributed vitally to the effective prosecution of the war."

Bureau of Naval Personnel

Holloway became director of training at theBureau of Naval Personnel

The Bureau of Naval Personnel (BUPERS) in the United States Department of the Navy is similar to the human resources department of a corporation. The bureau provides administrative leadership and policy planning for the Office of the Chief of N ...

in Washington, D.C., on November 15, 1943, where he earned a second Commendation Ribbon for having "integrated the various programs into one efficient organization with the bureau the center of all policies and procedures. His able directorship and foresight contributed greatly to the successful expansion of the naval training program during this crucial year of war." Holloway's sheer efficiency in this role worked against him when his request for sea duty was rejected by Secretary of the Navy

The Secretary of the Navy (SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department within the United States Department of Defense. On March 25, 2025, John Phelan was confirm ...

James V. Forrestal, who ruled that Holloway should continue in the training job, "where you are hitting your peak." Forrestal finally relented in late 1944 and released Holloway for duty in the Pacific theater.

USS ''Iowa''

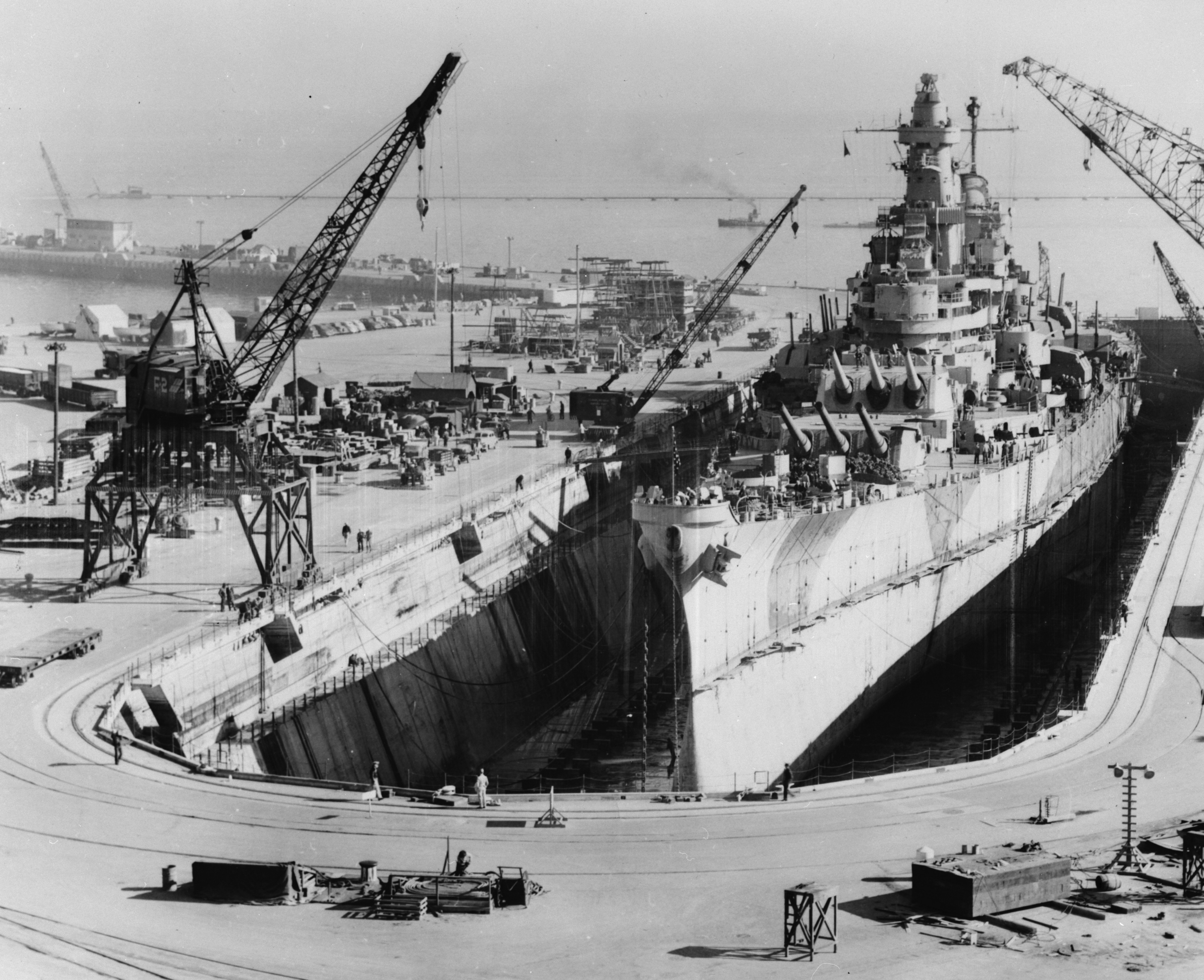

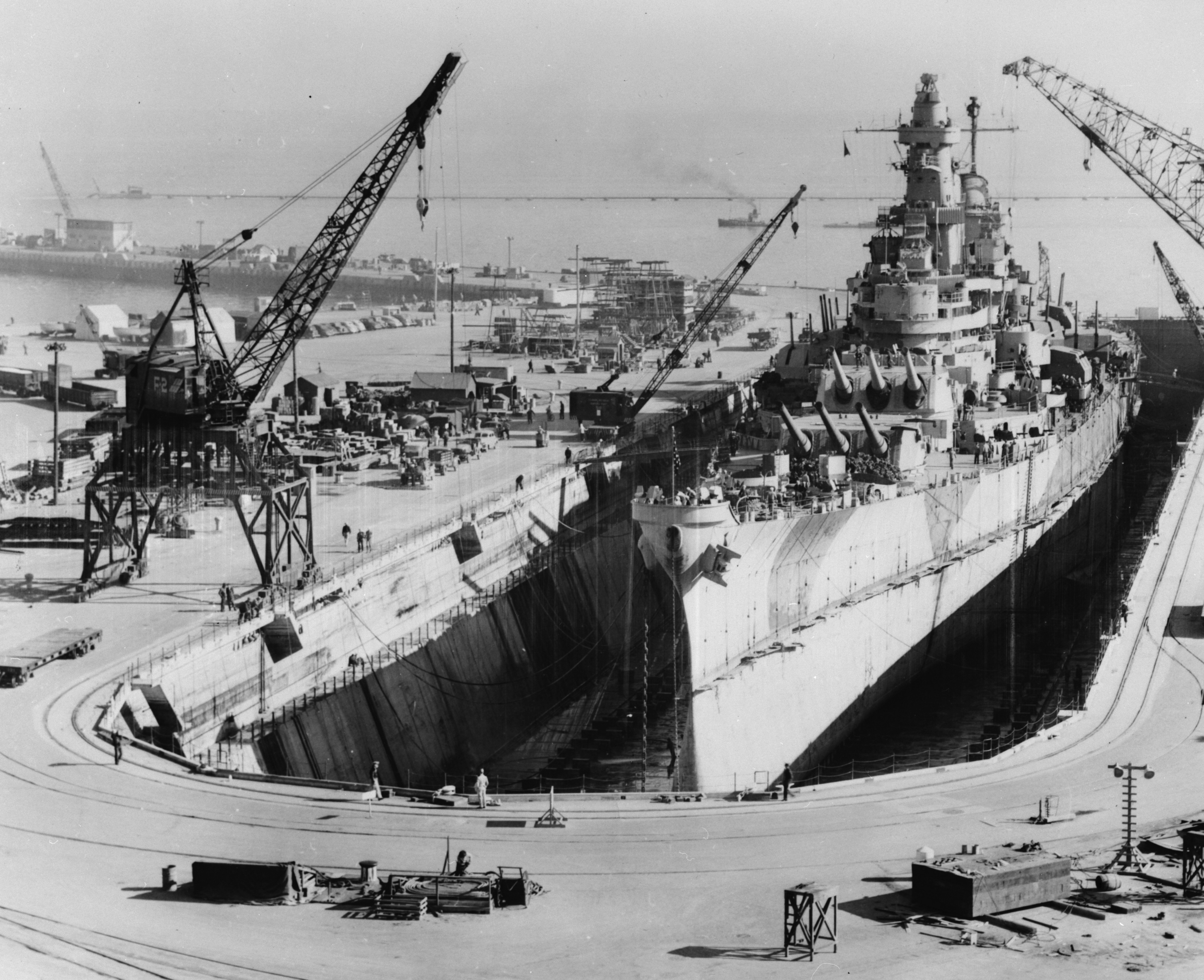

Holloway assumed command of the battleship , flagship of Battleship Division 7, in November 1944. Under his command, ''Iowa'' took part in attacks on

Holloway assumed command of the battleship , flagship of Battleship Division 7, in November 1944. Under his command, ''Iowa'' took part in attacks on Luzon

Luzon ( , ) is the largest and most populous List of islands in the Philippines, island in the Philippines. Located in the northern portion of the List of islands of the Philippines, Philippine archipelago, it is the economic and political ce ...

later that month, shooting down many enemy aircraft, and participated in strikes on the Japanese homeland from March

to July 1945. For commanding ''Iowa'' during these operations, he received a Gold Star in lieu of a second Legion of Merit, with the following citation: "With his vessel operating as flagship of several important striking and covering forces ... Holloway rendered distinguished service throughout the intensive actions and, by his brilliant leadership and outstanding skill, contributed materially to the extensive and costly damage inflicted on the enemy."

Holloway operated his battleship with characteristic flair, recalled Rear Admiral Ralph Kirk James, who had been the maintenance officer responsible for repair work on damaged ships at Manus when ''Iowa'' arrived at that base to fix shafting problems on 25 December 1944. "Jimmy Holloway was charging up the harbor with this big battleship, the biggest I'd seen, and I was getting more and more nervous." Alarmed, James warned Holloway to reduce his speed before entering the drydock. "'Oh no,' ollowaysaid ... He got the ship just about halfway into the dry dock when he ordered full speed astern. The ''Iowa'' shook like a damned destroyer and stopped just where she was supposed to be." Unfortunately, the backwash from the engine reversal swept away the drydock support blocks from underneath the ship, and James and his crew had to spend an extra three hours resetting the blocks before ''Iowa'' could dock. Afterward, James discovered a grey streak in his hair. "I can tell you the moment it was born: when Holloway pulled his high-speed throttle-jockey stunt on me."

Despite being captain of the premier surface vessel in the U.S. Navy, Holloway recognized that naval aviation had become dominant. Soon after assuming command of ''Iowa'', he wrote an urgent letter to his son, Lieutenant James L. Holloway III, who was following in his father's footsteps as a junior officer on a destroyer, to advise the young lieutenant to abandon his promising career in the surface Navy to become a naval aviator

Naval aviation / Aeronaval is the application of military air power by navies, whether from warships that embark aircraft, or land bases.

It often involves '' navalised aircraft'', specifically designed for naval use.

Seaborne aviation encompas ...

as soon as possible. "The war in the Pacific is being won by the carriers. The future of the U.S. Navy lies in naval aviation." Lieutenant Holloway promptly applied for flight training and went on to captain the nuclear aircraft carrier , the premier aviation vessel of its era.

Demobilization

Promoted to rear admiral, Holloway reported as Commander, of Fleet Training Command, Pacific Fleet on 8 August 1945. He was detached from that command less than two months later, on 26 September, to take charge of the Navy's troubled postwardemobilization

Demobilization or demobilisation (see American and British English spelling differences, spelling differences) is the process of standing down a nation's armed forces from combat-ready status. This may be as a result of victory in war, or becaus ...

.

Rear Admiral William M. Fechteler

William Morrow Fechteler (March 6, 1896 – July 4, 1967) was an admiral in the United States Navy who served as Chief of Naval Operations during the Eisenhower administration.

Biography

Fechteler was born in San Rafael, California, on Mar ...

, Assistant Chief of Naval Personnel, informed Holloway that demobilization in the Pacific was "completely chaotic", and ordered Holloway to take charge of the effort with the hastily created title of Assistant Chief of Naval Personnel for Demobilization. Holloway immediately conducted a quick inspection tour of West Coast demobilization centers and concluded that the biggest problem was understaffing at the receiving facilities, which lacked the personnel to process the paperwork for the flood of returning servicemen. To alleviate this bottleneck, Holloway augmented the demobilization center staff with yeomen, disbursing clerks, and anyone else who could read a form. However, after the Pacific returnees had been processed and discharged, they still had to be transported overland from their West Coast debarkation ports to their homes, the vast majority of which were located east of the Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in great-circle distance, straight-line distance from the northernmost part of Western Can ...

. Holloway deputized subordinate Howard "Red" Yeager as director of rail transportation for the Navy, and Yeager worked with the Association of American Railroads

The Association of American Railroads (AAR) is an industry trade group representing primarily the major freight Rail transport, railroads of North America (Canada, Mexico and the United States). Amtrak and some regional Commuter rail in North Am ...

to assemble the necessary rolling stock from scratch. "I think they reached as low as the Toonerville trolley", Holloway recalled.

Under Holloway's immediate direction, the task of demobilizing over three million men was completed by September 1, 1946. He won a Letter of Commendation for his skill as administrator and was officially praised for his skillful direction and supervision of the Navy's personnel demobilization plan.

Holloway resisted pressure from various dignitaries to speed the homecoming of favored constituents. When a member of the United States Senate brought in a friend to ask a favor, Holloway appealed to the senator's better nature: "I look to you, Senator, to help me maintain my probity." Said Holloway later, "No Congressman ever failed to react to such a plea."

Holloway Plan

While directing the navy's demobilization, Holloway also chaired an influential board that laid the foundation for the postwar

While directing the navy's demobilization, Holloway also chaired an influential board that laid the foundation for the postwar Naval Reserve Officer Training Corps

The Naval Reserve Officer Training Corps (NROTC) program is a college-based, commissioned officer training program of the United States Navy and the United States Marine Corps.

Origins

A pilot Naval Reserve unit was established in September 1924 ...

(NROTC). Named for its chairman, the Holloway Board was charged with "the development of the proper form, system, and method of education of officers in the postwar United States Navy." Its members included Williams College

Williams College is a Private college, private liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Williamstown, Massachusetts, United States. It was established as a men's college in 1793 with funds from the estate of Ephraim ...

president James P. Baxter III, Illinois Institute of Technology

The Illinois Institute of Technology, commonly referred to as Illinois Tech and IIT, is a Private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Tracing its history to 1890, the present name was adopted upon the m ...

president Henry T. Heald, Cornell University

Cornell University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university based in Ithaca, New York, United States. The university was co-founded by American philanthropist Ezra Cornell and historian and educator Andrew Dickson W ...

provost Arthur S. Adams, Rear Admiral Felix L. Johnson, Rear Admiral Stuart H. Ingersoll, Captain Charles D. Wheelock, Captain John P. W. Vest, Commander Charles K. Duncan, and Commander Douglas M. Swift. The report of the Holloway Board became known as the Holloway Plan, and it dramatically expanded the avenues by which officer candidates could enter the regular Navy.

Described as one of the most attractive educational opportunities ever offered, the Holloway Plan broke the Naval Academy's monopoly as a source for naval officers by offering students at fifty-two colleges and universities the same opportunities for a commission in the regular Navy and free education at government expense that was provided to Naval Academy midshipmen, without requiring a hard-to-obtain Congressional appointment. In return for a three-year service commitment, The federal government paid for officer candidates to obtain undergraduate degrees at accredited institutions, commissioning them upon graduation into the Naval Reserve. Unlike previous reservists, NROTC graduates could transfer their commissions into the regular Navy, allowing them to compete on the same basis as Naval Academy graduates. NROTC was intended to provide about half of the Navy's new officers every year, with the other half coming from the Naval Academy. There were two main tracks: the standard four-year course for line officer

A line officer or officer of the line is, opposed to staff officers or reserve officers, a military officer who is eligible for command of operational, tactical or combat units. The name most likely stems from the Early modern warfare tactics ...

s, and a seven-year Naval Aviation College Program (NACP) for naval aviator

Naval aviation / Aeronaval is the application of military air power by navies, whether from warships that embark aircraft, or land bases.

It often involves '' navalised aircraft'', specifically designed for naval use.

Seaborne aviation encompas ...

s.

Submitted to Congress for approval, the Holloway Plan spent the summer of 1946 stagnating as draft legislation in the House Naval Affairs Committee. Finally, with only two months before colleges were scheduled to begin their autumn classes, Holloway made a pilgrimage to the Georgia farm of committee chairman Carl Vinson

Carl Vinson (November 18, 1883 – June 1, 1981) was an American politician who served in the U.S. House of Representatives for over 50 years and was influential in the 20th century expansion of the U.S. Navy. He was a member of the Democrati ...

, and the bill was placed on the House Calendar the following week. It passed by unanimous vote and was signed into law by President Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. As the 34th vice president in 1945, he assumed the presidency upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt that year. Subsequen ...

on August 13, 1946.

During its early years, critics complained that the Holloway Plan was a waste of taxpayer money because many reservists enrolled in the program only for the free college education, and quit the Navy after serving the minimum three-year commitment. Holloway himself anticipated that NROTC graduates would be less committed to a naval career than Naval Academy graduates, given that "The Naval Academy is an undergraduate institution which no man should enter unless he wishes to make the Navy a life career." He was convinced that Annapolis remained the surer but tougher path to a successful Navy career, but argued that the Navy should not risk "putting all our eggs in one basket insofar as methods of initial fficerprocurement are concerned." Annapolis loyalists objected that if NROTC graduates were given the same career opportunities and chances for promotion as Naval Academy graduates, there would be no advantage to attending the Naval Academy and the quality of its midshipmen would plummet because the better officer candidates could opt for an easy commission at a civilian university that lacked the rigor of Naval Academy discipline. A popular Annapolis chant went: "Keep your car, keep your gal, keep your pay—be an officer the 'Holloway'!" Officers in the fleet quipped: "Did you get your commission the hard way or the Holloway?"

Nevertheless, the Holloway Plan quickly became a popular and effective program, and within five years its major features had been copied by the Army

An army, ground force or land force is an armed force that fights primarily on land. In the broadest sense, it is the land-based military branch, service branch or armed service of a nation or country. It may also include aviation assets by ...

and the Air Force

An air force in the broadest sense is the national military branch that primarily conducts aerial warfare. More specifically, it is the branch of a nation's armed services that is responsible for aerial warfare as distinct from an army aviati ...

. Early Holloway Plan alumni included future astronaut

An astronaut (from the Ancient Greek (), meaning 'star', and (), meaning 'sailor') is a person trained, equipped, and deployed by a List of human spaceflight programs, human spaceflight program to serve as a commander or crew member of a spa ...

Neil A. Armstrong and future four-star admiral George E. R. Kinnear II.

Forty years later, Holloway's son was responsible for interviewing the eminent lawyers, businessmen, and government officials who applied for membership in the exclusive Metropolitan Club of the City of Washington between 1988 and 1992. "I was truly amazed at the number of these prospective members who asked if I were any relation to the admiral who founded the Holloway Plan," recalled the younger Holloway, by then a famous admiral in his own right. "When I answered yes, they would tell me that they wouldn't be sitting there today if it weren't for the Holloway Plan....It had put them through college—schools like Princeton

Princeton University is a private Ivy League research university in Princeton, New Jersey, United States. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the Unit ...

, Duke University

Duke University is a Private university, private research university in Durham, North Carolina, United States. Founded by Methodists and Quakers in the present-day city of Trinity, North Carolina, Trinity in 1838, the school moved to Durham in 1 ...

, Caltech

The California Institute of Technology (branded as Caltech) is a private university, private research university in Pasadena, California, United States. The university is responsible for many modern scientific advancements and is among a small g ...

, and Stanford

Leland Stanford Junior University, commonly referred to as Stanford University, is a private research university in Stanford, California, United States. It was founded in 1885 by railroad magnate Leland Stanford (the eighth governor of and th ...

. After the Korean War

The Korean War (25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953) was an armed conflict on the Korean Peninsula fought between North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea; DPRK) and South Korea (Republic of Korea; ROK) and their allies. North Korea was s ...

and Vietnam

Vietnam, officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV), is a country at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of about and a population of over 100 million, making it the world's List of countries and depende ...

, the opportunities were so great on the outside that many of them left the service and became quite successful in their civilian careers."

Superintendent of the U.S. Naval Academy

superintendent of the United States Naval Academy

The superintendent of the United States Naval Academy is its commanding officer. The position is a statutory office (), and is roughly equivalent to the Chancellor (education), chancellor or University president, president of an American civilian ...

, succeeding Vice Admiral Fitch.Superintendents of the U.S. Naval AcademyAt 48, Holloway was the youngest superintendent in fifty years, having been handpicked by

Secretary of the Navy

The Secretary of the Navy (SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department within the United States Department of Defense. On March 25, 2025, John Phelan was confirm ...

Forrestal to implement the academic changes suggested by the Holloway Board, which had recommended that the Naval Academy curriculum move away from rote recitation and continuous crams "to give a stronger emphasis to basic and general education, rendering more fundamental and less detailed instruction in strictly naval material and techniques."

In his first year as superintendent, Holloway revised the curriculum to promote a balanced program of mutually supporting courses, including a newly expanded leadership course on human relations problems, for which half of the textbook was written by psychology experts from Johns Hopkins University

The Johns Hopkins University (often abbreviated as Johns Hopkins, Hopkins, or JHU) is a private university, private research university in Baltimore, Maryland, United States. Founded in 1876 based on the European research institution model, J ...

and the other half by Holloway himself. He also procured modern equipment for the ordnance, gunnery, and marine engineering departments and instituted annual faculty symposia to "explore and confirm methods employed in both education and training." Midshipmen were thoroughly indoctrinated "in all aspects of naval aviation" as a graduation requirement.

To compensate for the increased academic expectations, Holloway loosened the regulations restricting midshipman activities, allowing first classmen to own cars, go on leave every other weekend, store civilian clothing in dormitory rooms, and stay up until 11:00 PM every night. Some of these liberties were later revoked by Holloway's successor, Vice Admiral Harry W. Hill. The first class was also delegated greater responsibility for student governance, and attempted to purge "flagrant violations of mature personal dignity" from midshipman hazing rituals, with mixed success.

Despite his energetic reforms and personal popularity among the midshipmen, Holloway's three-year tour as superintendent ultimately was too brief to reverse the Naval Academy's entrenched cultural bias against academic achievement. A more durable legacy was the series of yawl

A yawl is a type of boat. The term has several meanings. It can apply to the rig (or sailplan), to the hull type or to the use which the vessel is put.

As a rig, a yawl is a two masted, fore and aft rigged sailing vessel with the mizzen mast ...

races Holloway initiated to promote seamanship and competitive sailing, dubbed the Holloway trophy races after the award for the winning midshipman skipper. Holloway also addressed the dismal living conditions of the enlisted men based at the Academy by upgrading their quarters from trailer parks to a village of Wherry

A wherry is a type of boat that was traditionally used for carrying cargo or passengers on rivers and canals in England, and is particularly associated with the River Thames and the River Cam. They were also used on the Broadland rivers of No ...

housing units on the north shore of the Severn River. He declared that a midshipman's first lesson must be a concern for enlisted men's welfare and that Annapolis of all places must set the example.

Educational unification

Throughout his career, Holloway vigorously defended the Naval Academy's special role as the preeminent source of naval officers in the U.S.

As chairman of the Holloway Board, Holloway helped fend off proposals to downgrade the importance of Annapolis by converting the Academy into a two-year postgraduate school for students who had already completed at least three years of college, a plan that would double the number of officers that could be produced by halving the time spent at the Academy. The Holloway Board also rejected another proposal, popular among local politicians, to expand enrollment by establishing satellite Naval Academies in other coastal cities. "It was deemed wiser that the Naval Academy at Annapolis, with its history and traditions, be the single institution representing...the ultimate in personal and professional standards, and a principal binding force...in the Navy as a whole."

In January 1947, less than two weeks after becoming Academy superintendent, Holloway rebuffed a proposal by Army Chief of Staff

Throughout his career, Holloway vigorously defended the Naval Academy's special role as the preeminent source of naval officers in the U.S.

As chairman of the Holloway Board, Holloway helped fend off proposals to downgrade the importance of Annapolis by converting the Academy into a two-year postgraduate school for students who had already completed at least three years of college, a plan that would double the number of officers that could be produced by halving the time spent at the Academy. The Holloway Board also rejected another proposal, popular among local politicians, to expand enrollment by establishing satellite Naval Academies in other coastal cities. "It was deemed wiser that the Naval Academy at Annapolis, with its history and traditions, be the single institution representing...the ultimate in personal and professional standards, and a principal binding force...in the Navy as a whole."

In January 1947, less than two weeks after becoming Academy superintendent, Holloway rebuffed a proposal by Army Chief of Staff Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

to essentially unify the Naval Academy with the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), commonly known as West Point, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York that educates cadets for service as Officer_(armed_forces)#United_States, comm ...

at West Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), commonly known as West Point, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York that educates cadets for service as Officer_(armed_forces)#United_States, comm ...

. Eisenhower believed the curricula of West Point and Annapolis should be as close to identical as possible and proposed a full-scale exchange program in which West Point cadets and Annapolis midshipmen would each spend their third year at the other service's academy. Holloway's bluntly phrased rejection drove a furious Eisenhower to complain to Chief of Naval Operations

The chief of naval operations (CNO) is the highest-ranking officer of the United States Navy. The position is a statutory office () held by an Admiral (United States), admiral who is a military adviser and deputy to the United States Secretary ...

Chester W. Nimitz

Chester William Nimitz (; 24 February 1885 – 20 February 1966) was a fleet admiral in the United States Navy. He played a major role in the naval history of World War II as Commander in Chief, US Pacific Fleet, and Commander in Chief, ...

that Holloway considered his idea "the ultimate in ridiculousness." Colonel and President of Georgia Tech Blake R Van Leer

Blake Ragsdale Van Leer (August 16, 1893 – January 23, 1956) was an American academic administrator, engineer, and U.S. Army officer who served as the fifth president of the Georgia Institute of Technology from 1944 until his death in 1956. Orph ...

later defended Holloway's plans for training and education for naval officers. President Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. As the 34th vice president in 1945, he assumed the presidency upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt that year. Subsequen ...

and Holloway would later appoint Van Leer to the visitor board and have him assist with creating programs and advising on the curriculum.

In March 1949, Holloway was the junior member of the Stearns-Eisenhower Board, convened to consider the topic of educational unification among the services. Chaired by University of Colorado

The University of Colorado (CU) is a system of public universities in Colorado. It consists of four institutions: the University of Colorado Boulder, the University of Colorado Colorado Springs, the University of Colorado Denver, and the U ...

president Robert Stearns, the board was initially inclined to recommend that officer candidates from all services study the same core academic curriculum at a single unified academy, as favored by the new Secretary of Defense, Louis Johnson, with Annapolis and West Point being reduced to specialized training campuses. To everyone's surprise, Holloway persuaded the other members to adopt the diametrically opposite recommendation that the existing service academy system be not only preserved but expanded by adding a new service academy for the Air Force.

In 1954, Holloway's loyalty to the Naval Academy landed him in professional trouble for the only time in his career. Testifying before a congressional committee in favor of the proposed creation of the United States Air Force Academy

The United States Air Force Academy (USAFA) is a United States service academies, United States service academy in Air Force Academy, Colorado, Air Force Academy Colorado, immediately north of Colorado Springs, Colorado, Colorado Springs. I ...

, Holloway declared that he was sick and tired of sending Naval Academy graduates to the Air Force and admitted that he did everything possible to prevent such "desertions." Called to account by an infuriated Deputy Secretary of Defense

The deputy secretary of defense (acronym: DepSecDef) is a statutory office () and the second-highest-ranking official in the Department of Defense of the United States of America.

The deputy secretary is the principal civilian deputy to the s ...

Roger M. Kyes, Holloway stood by his words. "What's wrong with that?" he demanded. "We don't want our boys going to the Air Force. We teach them things we don't want used against us later."

Chief of Naval Personnel

After completing his tour as superintendent in 1950, Holloway served 30 months as Commander, Battleship-Cruiser Force, Atlantic (COMBATCRULANT) before being promoted to vice admiral on February 2, 1953, and appointed chief of the

After completing his tour as superintendent in 1950, Holloway served 30 months as Commander, Battleship-Cruiser Force, Atlantic (COMBATCRULANT) before being promoted to vice admiral on February 2, 1953, and appointed chief of the Bureau of Naval Personnel

The Bureau of Naval Personnel (BUPERS) in the United States Department of the Navy is similar to the human resources department of a corporation. The bureau provides administrative leadership and policy planning for the Office of the Chief of N ...

(BuPers). He served as Chief of Naval Personnel from 1953 to 1957, longer than any other BuPers chief in 75 years. Charged by statute with the selection and assignment of all naval personnel, his hiring philosophy was, "We should get the best people we can for these jobs and make them play over their heads."

As Chief of Naval Personnel, Holloway managed a variety of personnel issues arising from the end of the Korean War

The Korean War (25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953) was an armed conflict on the Korean Peninsula fought between North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea; DPRK) and South Korea (Republic of Korea; ROK) and their allies. North Korea was s ...

, such as promotions for returned prisoners of war and improvement of housing facilities, as well as the desegregation of the Navy. He abolished the policy of separate recruitment of black and white sailors that had tended to channel white recruits into mainstream branches but relegate black recruits to menial commissary and steward functions.

"Keeps a taut ship," remarked contemporaries at the Pentagon, but also "keeps a tight lip," despite a reputation for florid speech and unusually lengthy prepared statements before Congressional committees. For example, when asked by a House Appropriations subcommittee whether it was Navy policy to promote personnel on discharge even if they had been discharged because of Communist affiliations, a charge Senator Joseph R. McCarthy had leveled against the Army, Holloway replied, "It is not. I am not saying that in criticism of anyone else...Sometimes, in the best of families, the right hand does not know what the left hand doeth. But it is certainly not the policy in the Navy, and it is one we abjure."

Hyman G. Rickover

Holloway was an early ally of Rear Admiral Hyman G. Rickover, the controversial father of the Navy's nuclear propulsion program. To induce promising

Holloway was an early ally of Rear Admiral Hyman G. Rickover, the controversial father of the Navy's nuclear propulsion program. To induce promising line officer

A line officer or officer of the line is, opposed to staff officers or reserve officers, a military officer who is eligible for command of operational, tactical or combat units. The name most likely stems from the Early modern warfare tactics ...

s to submit to the rigors of nuclear training, Rickover insisted that only nuclear-qualified officers be allowed to command a nuclear vessel. Holloway agreed with Rickover's concept and allowed Rickover to screen the candidate pool from which BuPers would select officers for nuclear training. Rickover retained this absolute control over nuclear candidate selection until his retirement in 1982.

In June 1953, Rickover faced mandatory retirement after being passed over by the rear admiral selection board, and Holloway was one of the few flag officers to push for his promotion.

Rickover was promoted to rear admiral by the next selection board in July. "This is the end of the selection system," mourned one of Holloway's friends. "No, it isn't," Holloway replied. "It isn't the end...because we've used a law to promote him...to make the will of the Secretary felt. When we're too hidebound and reactionary, there's room in the law for the Secretary to get his way. If you don't do that, you'd have a special law in Congress which would ''really'' be the end of the selection system." Only a couple of weeks later, Congress proved Holloway's point by attaching a provision to the annual defense appropriations bill that promoted Brigadier General Robert S. Moore to major general, after the Army had refused to advance him through the normal system.Act of August 1, 1953 epartment of Defense Appropriation Act, 1954(). "This sort of thing is what we must guard against," complained General Herbert B. Powell, Holloway's counterpart in the personnel section of the Army staff at the time. "We must follow the system set up and prescribed by law.”

Commander in Chief, U.S. Naval Forces, Eastern Atlantic and Mediterranean

On October 26, 1957, PresidentDwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

named Holloway to succeed Admiral Walter F. Boone as Commander in Chief, U.S. Naval Forces, Eastern Atlantic and Mediterranean

The United States Naval Forces Europe and Africa (NAVEUR-NAVAF), is the United States Navy component command of the United States European Command and United States Africa Command. Prior to 2020, NAVEUR-NAVAF was previously referred to as United S ...

(CINCNELM), Holloway assumed command in November 1957, and was promoted to full admiral on January 1, 1958. with additional duty as Commander, Subordinate Command U.S. Atlantic Fleet (COMSCOMLANTFLT), and later as U.S. Commander Eastern Atlantic (USCOMEASTLANT).Chronology of Commanders, U.S. Naval Forces EuropeAs CINCNELM, Holloway commanded all U.S. naval forces in Europe, including the Sixth Fleet commanded by Vice Admiral Charles R. Brown. In November 1957, the

Joint Chiefs of Staff

The Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) is the body of the most senior uniformed leaders within the United States Department of Defense, which advises the president of the United States, the secretary of defense, the Homeland Security Council and ...

instructed Holloway to establish a specified command, the first in Eisenhower's defense reorganization program. In the event of an emergency in the Middle East, he was to transfer his flag from London to the Mediterranean as Commander in Chief, Specified Command, Middle East (CINCSPECOMME).

Lebanon crisis of 1958

On July 14, 1958, theHashemite

The Hashemites (), also House of Hashim, are the Dynasty, royal family of Jordan, which they have ruled since 1921, and were the royal family of the kingdoms of Kingdom of Hejaz, Hejaz (1916–1925), Arab Kingdom of Syria, Syria (1920), and Kingd ...

dynasty in Iraq

Iraq, officially the Republic of Iraq, is a country in West Asia. It is bordered by Saudi Arabia to Iraq–Saudi Arabia border, the south, Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq border, the east, the Persian Gulf and ...

was overthrown by a military coup d'état

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. Militaries are typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with their members identifiable by a d ...

. Fearing that he would be next, Lebanese president Camille Chamoun

Camille Nimr Chamoun (, ; 3 April 19007 August 1987) was a Lebanese politician who served as the 2nd president of Lebanon from 1952 to 1958. He was one of the country's main Christian leaders during most of the Lebanese Civil War.

Early yea ...

appealed for American military aid within 48 hours to settle domestic unrest in his own country, invoking the Eisenhower Doctrine

The Eisenhower Doctrine was a policy enunciated by U.S. president Dwight D. Eisenhower on January 5, 1957, within a "Special Message to the Congress on the Situation in the Middle East". Under the Eisenhower Doctrine, a Middle Eastern country c ...

, which stated that the United States would intervene upon request to stabilize countries threatened by international communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

. Holloway, who happened to be serving on a Selection Board in Washington at the time, promptly met with Chief of Naval Operations Arleigh A. Burke, who warned that a deployment order was imminent but that commitments in East Asia precluded any reinforcements from the Seventh Fleet

The Seventh Fleet is a numbered fleet of the United States Navy. It is headquartered at U.S. Fleet Activities Yokosuka, in Yokosuka, Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan. It is part of the United States Pacific Fleet. At present, it is the largest of th ...

. Retorted Holloway, "I don't need any help. I can take over all of the Lebanon if you say the word." As one of Burke's few remaining peers in the Navy, Holloway took the opportunity to tease the CNO. "But I've already had another proposition....From some Britisher. He thinks, if there's action, I should go up and take the port of Tripoli

Tripoli or Tripolis (from , meaning "three cities") may refer to:

Places Greece

*Tripolis (region of Arcadia), a district in ancient Arcadia, Greece

* Tripolis (Larisaia), an ancient Greek city in the Pelasgiotis district, Thessaly, near Larissa ...

to protect their oil installations there." The famously mercurial Burke cursed him out.

At 6:23 p.m. on July 14, President Eisenhower ordered that the American intervention force begin to arrive at Beirut

Beirut ( ; ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, just under half of Lebanon's population, which makes it the List of largest cities in the Levant region by populatio ...

by 9:00 a.m. on July 15, when he planned to announce the intervention on national television. Burke relayed the order to Holloway at 6:30 p.m., adding, "Join your flagship now. Sail all Sixth Fleet eastward." Holloway had been given less than fifteen hours to establish a beachhead

A beachhead is a temporary line created when a military unit reaches a landing beach by sea and begins to defend the area as other reinforcements arrive. Once a large enough unit is assembled, the invading force can begin advancing inland. Th ...

. He immediately flew back to his London headquarters, where he stopped just long enough to assemble his staff and activate Operation Bluebat, a preplanned scenario for suppressing a coup d'état

A coup d'état (; ; ), or simply a coup

, is typically an illegal and overt attempt by a military organization or other government elites to unseat an incumbent leadership. A self-coup is said to take place when a leader, having come to powe ...

in Lebanon, before flying on to Beirut.

On July 15, only four minutes behind schedule, the first wave of Marines landed on a tourist beach near Beirut. In one of the most colorful episodes in Marine Corps history, a delighted crowd of curious spectators and bikini

A bikini is a two-piece swimsuit primarily worn by women that features one piece on top that covers the breasts, and a second piece on the bottom: the front covering the pelvis but usually exposing the navel, and the back generally covering ...

-clad sunbathers waved and cheered as a battalion of Marines waded ashore in full battle gear and stormed the beach. Soft drink

A soft drink (see #Terminology, § Terminology for other names) is a class of non-alcoholic drink, usually (but not necessarily) Carbonated water, carbonated, and typically including added Sweetness, sweetener. Flavors used to be Natural flav ...

vendors and ice cream

Ice cream is a frozen dessert typically made from milk or cream that has been flavoured with a sweetener, either sugar or an alternative, and a spice, such as Chocolate, cocoa or vanilla, or with fruit, such as strawberries or peaches. Food ...

carts appeared playing nickelodeon

Nickelodeon (nicknamed Nick) is an American pay television channel and the flagship property of the Nickelodeon Group, a sub-division of the Paramount Media Networks division of Paramount Global. Launched on April 1, 1979, as the first ca ...

music while small boys swam out to the landing craft and offered to help the Marines carry their equipment. After herding the civilians out of the way, the Marines secured the landing site and seized Beirut International Airport

Beirut ( ; ) is the capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, just under half of Lebanon's population, which makes it the fourth-largest city in the Levant region and the sixteenth-largest i ...

. Holloway flew into the airport from London at 4:00 a.m. on July 16 and boarded his flagship in time to supervise the next wave of landings, which he summarized for Burke in one word: "Flawless."

At 10:30 a.m. on July 16, as the Marines prepared to move into Beirut, it was discovered that

At 10:30 a.m. on July 16, as the Marines prepared to move into Beirut, it was discovered that Lebanese Army

The Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF; ), also known as the Lebanese Army (), is the national military of the Republic of Lebanon. It consists of three branches, the ground forces, the air force, and the navy. The motto of the Lebanese Armed Forces is ...

tanks had blocked the road from the airport, with orders to prevent the Marines from entering the city. Holloway raced to the scene, arriving at the roadblock at the same time as the American ambassador to Lebanon, Robert M. McClintock, and the general in chief of the Lebanese Army, General Fuad Chehab

Fouad Abdallah Chehab ( / ; 19 March 1902 – 25 April 1973) was a Lebanese general and statesman who served as president of Lebanon from 1958 to 1964. He is considered to be the founder of the Lebanese Army after Lebanon gained independence f ...

. Adjourning to a nearby schoolhouse for an impromptu conference, they devised a compromise whereby the Lebanese Army would escort the Marines into the city. Holloway insisted that they start moving right away, "tootey-sweetey".

"We were really sitting on a powder keg," Holloway said later, "but fortunately there were no incidents. We just got in a car—Ambassador McClintock and I—and led the column straight through." Once the column entered the city, Chehab departed and Holloway "assumed personal tactical command," directing individual units to their respective billeting areas in the city—"my first and last experience in field officer

A senior officer is an officer of a more senior grade in military or other uniformed services. In military organisations, the term may refer to any officer above junior officer rank, but usually specifically refers to the middle-ranking group of ...

grade with land forces."

On July 17, Deputy Under Secretary of State Robert D. Murphy arrived in Beirut as President Eisenhower's personal representative, charged with resolving the political situation. Conferring daily with Holloway, Murphy quickly concluded that the decision to intervene had been based on faulty assumptions. "We agreed that much of the conflict concerned personalities and rivalries of a domestic nature, with no relation to international issues." In particular, Holloway and Murphy felt that the insurrection had nothing to do with international communism and that Chamoun's presidency was doomed for purely domestic reasons. Murphy decided that the only solution was to elect a new president who would ask that the American forces be removed as soon as possible. He brokered a deal between the dissident factions to allow a new presidential election, which General Chehab won on July 31.

With the Lebanese government nominally stabilized, Holloway was directed on August 5 to begin planning a withdrawal schedule, which he submitted for approval on August 11. The first Marine battalion began reembarking immediately. United Nations diplomat Rajeshwar Dayal observed the Marines' departure, "a process which seemed more difficult of accomplishment than the landing. It was evident that the gallant Admiral Holloway, sceptical from the start about the wisdom of the whole exercise, felt an infinite sense of relief at the prospect of an early departure." President Chehab took office on September 23 and a unity government was formed on October 23. The last American troops left Lebanon two days later.

In the end, Operation Bluebat sent nearly 15,000 American troops to Lebanon from commands in Europe and the continental United States, including 6,100 Marines and 3,100 Army airborne troops armed with nuclear artillery

Nuclear artillery is a subset of limited-nuclear weapon yield, yield tactical nuclear weapons, in particular those weapons that are launched from the ground at battlefield targets. Nuclear artillery is commonly associated with shell (projectile ...

; the 76 ships of the Sixth Fleet; and a 200-plane Composite Air Task Force based out of Incirlik Air Base

Incirlik Air Base () is a Republic of Turkey, Turkish air base of slightly more than 3320 ac (1335 ha), located in the İncirlik quarter of the city of Adana, Turkey. The base is within an urban area of 1.7 million people, east of the city ...

, Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

. The intervention forces remained in Lebanon for 102 days, at a cost of over $200 million, acting as an urban security force and losing only one American soldier to hostile fire.

Holloway professed satisfaction with the near-perfect outcome. "The proof of the pudding is in the eating. The operation would appear to stand as an unqualified success." Nevertheless, Operation Bluebat came to be viewed as a case study in how not to plan an operation. According to one history, "Virtually every official report opens with the caveat that had Operation Bluebat been opposed, disasters would have occurred, and argues that problems encountered during the operation's course could have been solved well before the order to execute was given."

Holloway inadvertently created one of these problems himself when he ordered Major General David W. Gray to establish an Army base in a large olive

The olive, botanical name ''Olea europaea'' ("European olive"), is a species of Subtropics, subtropical evergreen tree in the Family (biology), family Oleaceae. Originating in Anatolia, Asia Minor, it is abundant throughout the Mediterranean ...

grove just east of the airport. Said Gray, "I asked, 'Isn't that private property? Whom should I see about it?' I shall never forget olloway'sanswer. Waving his arms in characteristic fashion, he replied, 'Matter of military necessity. Send the bills to the Ambassador.' Of course, it didn't work out exactly that way...." It turned out that the olive grove was the largest in Lebanon and vital to the local economy, but the Lebanese women who harvested the olives refused to enter the grove while American troops were present, risking the loss of the entire crop and severe unemployment. Holloway wryly observed that when his forces finally departed, they left behind a constitutionally elected president, a united army, peace in the area, and "a few legal beagles to pay for damage to the olive groves."

Holloway's superiors on the Joint Chiefs of Staff

The Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) is the body of the most senior uniformed leaders within the United States Department of Defense, which advises the president of the United States, the secretary of defense, the Homeland Security Council and ...

(JCS) introduced complications of their own, recalled Gray. "One day I walked in on Admiral Holloway to find him sputtering. He said, 'Do you know what I just told the JCS? I am sixty-years old, I have thirty-five years of service, I have a physical infirmity that will allow me to retire tomorrow, and I will do it if you don't leave me alone and let me do my job.'"

Retirement

Holloway was relieved as CINCNELM by Admiral Robert L. Dennison in March 1959. Returning to Washington for his well-attended retirement ceremony a month later, Holloway declared that he definitely would not follow the example of other high-ranking military retirees in that he was actually going to retire, not start a second career in business. After his retirement from the Navy, he served as Governor of the United States Naval Home in

Holloway was relieved as CINCNELM by Admiral Robert L. Dennison in March 1959. Returning to Washington for his well-attended retirement ceremony a month later, Holloway declared that he definitely would not follow the example of other high-ranking military retirees in that he was actually going to retire, not start a second career in business. After his retirement from the Navy, he served as Governor of the United States Naval Home in Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

, Pennsylvania, from 1964 until 1966.

In later life, he moved to Carl Vinson Hall, a Navy retirement home in McLean, Virginia

McLean ( ) is an Unincorporated area#United States, unincorporated community and census-designated place in Fairfax County, Virginia, United States. The population of the community was 50,773 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. It is ...

. He died on January 11, 1984, of an aortic aneurysm

An aortic aneurysm is an enlargement (dilatation) of the aorta to greater than 1.5 times normal size. Typically, there are no symptoms except when the aneurysm dissects or ruptures, which causes sudden, severe pain in the abdomen and lower back ...

at Fairfax Hospital in Falls Church, Virginia

Falls Church City is an independent city (United States), independent city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Virginia, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population was 14,658. Falls Church is ...

.

Personal life

Holloway was a husky, round-faced man with blue eyes and brown hair who stood six feet tall, weighed 190 pounds, and spoke in a light southern drawl. He was nicknamed "Lord Jim", as much for his reputation as a strict disciplinarian as for the aristocratic affectations that ''Time

Time is the continuous progression of existence that occurs in an apparently irreversible process, irreversible succession from the past, through the present, and into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequ ...

'' dubbed "a suave, diplomatic air that sometimes spills over into pomposity":

United Nations diplomat Rajeshwar Dayal described Holloway as "a gentleman to the core" during his interactions with the United Nations Observation Group in Lebanon (UNOGIL

The United Nations Observation Group in Lebanon (UNOGIL) was established by United Nations through Security Council Resolution 128 on 11 June 1958 in response to the 1958 Lebanon crisis. The group was deployed between June and December 1958 in a ...

) in 1958. "He was a man of impressive presence and courtly ways and fully deserved his sobriquet of 'Lord Jim'. ... We found him a charming and engaging personality and a man of his word." Major General David W. Gray, who commanded the Army contingent during the initial stages of the Lebanon intervention, recalled:

Holloway was widely admired within the Navy, although he was identified so strongly as being a deskbound staff officer that when he assumed operational command of Operation Bluebat in 1958, other officers joked, "Oh, he's finally gone to sea." ''Los Angeles Times

The ''Los Angeles Times'' is an American Newspaper#Daily, daily newspaper that began publishing in Los Angeles, California, in 1881. Based in the Greater Los Angeles city of El Segundo, California, El Segundo since 2018, it is the List of new ...

'' columnist Bill Henry observed, "When President Eisenhower announced that our leader of United States forces in the Middle East would be an officer named Adm. Holloway, there was a sort of 'Who dat?' reaction. James Lemuel Holloway Jr. has not been a dashing, spectacular figure. He has, however, compiled a steady record of uncanny ability as an organizer which has overshadowed a fine combat record in two world wars."

While chief of the Bureau of Personnel, Holloway summarized his philosophy to a group of young naval officers: "You men probably do not think of it in this way, but I do. To be commissioned in the Navy, you had to be appointed by the President with the approval of Congress. This is the procedure and requirement for the seating of a Supreme Court judge or an ambassador. This is why a naval officer must have his chin out at all times." Admiral Elmo R. Zumwalt Jr.

Elmo Russell "Bud" Zumwalt Jr. (November 29, 1920 – January 2, 2000) was a United States Navy officer and the youngest person to serve as Chief of Naval Operations. As an admiral and later the 19th Chief of Naval Operations, Zumwalt played a m ...

, a lieutenant commander in BuPers from 1953 to 1955, remembered Holloway as "the superior who most impressed me when I was a young officer."

Family

Holloway married the former Jean Gordon Hagood, daughter of

Holloway married the former Jean Gordon Hagood, daughter of U.S. Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of the United Stat ...

Major General Johnson Hagood, of Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the List of municipalities in South Carolina, most populous city in the U.S. state of South Carolina. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint of South Carolina's coastline on Charleston Harbor, an inlet of the Atla ...

, on May 11, 1921. They had two children: son James Lemuel Holloway III, who also attained the rank of four-star admiral as Chief of Naval Operations from 1974 to 1978; and daughter Jean Gordon Holloway, whose husband, Rear Admiral Lawrence Heyworth Jr., was the first commanding officer of the aircraft carrier and briefly served as the 45th superintendent of the U.S. Naval Academy.