Jacob's Island on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Jacob's Island was a notorious

Jacob's Island was a notorious

Bermondsey was historically a rural parish on the outskirts of London until the 17th century when the area began to be developed as a wealthy

Bermondsey was historically a rural parish on the outskirts of London until the 17th century when the area began to be developed as a wealthy

Dickens wrote in a preface to ''Oliver Twist'', in March 1850, that in the intervening years his descriptions of the disease, crime and poverty of Jacob's Island had come to sound so fanciful to some that

Dickens wrote in a preface to ''Oliver Twist'', in March 1850, that in the intervening years his descriptions of the disease, crime and poverty of Jacob's Island had come to sound so fanciful to some that

In Charles Kingsley's 1850 novel '' Alton Locke'', the title character visits Jacob's Island and sees the death of the drunken Jimmy Downes, who has been reduced to poverty, and the bodies of his family, taken by typhus. Kingsley had been inspired by the accounts of the 1849 cholera epidemics published by ''The Morning Chronicle'' to visit Jacob's Island with his friend

In Charles Kingsley's 1850 novel '' Alton Locke'', the title character visits Jacob's Island and sees the death of the drunken Jimmy Downes, who has been reduced to poverty, and the bodies of his family, taken by typhus. Kingsley had been inspired by the accounts of the 1849 cholera epidemics published by ''The Morning Chronicle'' to visit Jacob's Island with his friend

The site of the former Jacob's Island was heavily damaged in the Blitz during World War II, when it was extensively bombed by the Luftwaffe due to the industrial presence in the area. Today it is part of the London Borough of Southwark, with only one of the Victorian warehouses surviving. In 1981, the area was one of the first in the

The site of the former Jacob's Island was heavily damaged in the Blitz during World War II, when it was extensively bombed by the Luftwaffe due to the industrial presence in the area. Today it is part of the London Borough of Southwark, with only one of the Victorian warehouses surviving. In 1981, the area was one of the first in the

Jacobs Island Residents Association

{{coord, 51.5013, -0.0706, type:landmark_region:GB-SWK, display=title Areas of London Former slums of London History of the London Borough of Southwark Bermondsey

Jacob's Island was a notorious

Jacob's Island was a notorious slum

A slum is a highly populated urban residential area consisting of densely packed housing units of weak build quality and often associated with poverty. The infrastructure in slums is often deteriorated or incomplete, and they are primarily inh ...

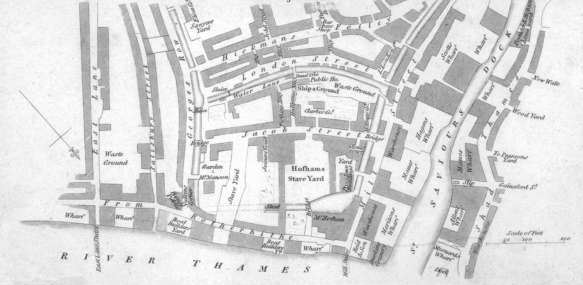

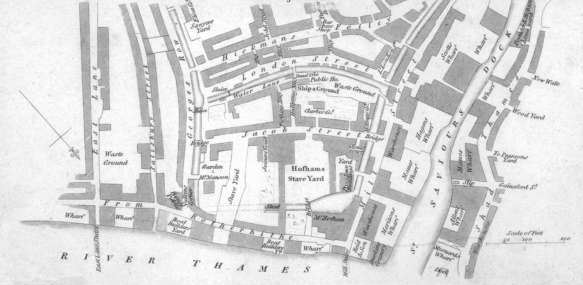

in Bermondsey, London, in the 19th century. It was located on the south bank of the River Thames, approximately delineated by the modern streets of Mill Street, Bermondsey Wall West, George Row and Wolseley Street. Jacob's Island developed a reputation as one of the worst slums in London, and was popularised by the Charles Dickens novel ''Oliver Twist

''Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress'', Charles Dickens's second novel, was published as a serial from 1837 to 1839, and as a three-volume book in 1838. Born in a workhouse, the orphan Oliver Twist is bound into apprenticeship with ...

'', published shortly before the area was cleared in the 1860s.

History

The origin of the name is not clear, but one possibility is that it derives from a vernacular term for frogs.Swamp

Bermondsey was historically a rural parish on the outskirts of London until the 17th century when the area began to be developed as a wealthy

Bermondsey was historically a rural parish on the outskirts of London until the 17th century when the area began to be developed as a wealthy suburb

A suburb (more broadly suburban area) is an area within a metropolitan area, which may include commercial and mixed-use, that is primarily a residential area. A suburb can exist either as part of a larger city/urban area or as a separate ...

following the Great Fire of London

The Great Fire of London was a major conflagration that swept through central London from Sunday 2 September to Thursday 6 September 1666, gutting the medieval City of London inside the old Roman city wall, while also extending past the ...

. By the 19th century, the once affluent parts of Bermondsey had experienced a serious decline, and became the site of notorious slums with the arrival of industrialisation

Industrialisation ( alternatively spelled industrialization) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive re-organisation of an econo ...

, docks and migrant housing, especially along the riverside.

The most notorious of the slums was known as Jacob's Island, with the boundary approximately the confluence

In geography, a confluence (also: ''conflux'') occurs where two or more flowing bodies of water join to form a single channel. A confluence can occur in several configurations: at the point where a tributary joins a larger river (main stem); o ...

of the Thames and subterranean

Subterranean(s) or The Subterranean(s) may refer to:

* Subterranea (geography), underground structures, both natural and man-made

Literature

* ''Subterranean'' (novel), a 1998 novel by James Rollins

* ''Subterranean Magazine'', an American fa ...

River Neckinger

The River Neckinger is a reduced subterranean river that rises in Southwark and flows approximately through that part of London to St Saviour's Dock where it enters the Thames. What remains of the river is enclosed and runs underground and most ...

, at St Saviour's Dock across from Shad Thames, to the west, a tidal ditch just west of George Row to the east, and another tidal ditch just north of London Street (now Wolseley Street) to the south. It was a particularly squalid rookery, and described as "The very capital of cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting and ...

" and "The Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

of drains" by '' The Morning Chronicle'' in 1849.

In the 1840s it became "a site of radical activity", and, after attention from novelists Charles Dickens and Charles Kingsley

Charles Kingsley (12 June 1819 – 23 January 1875) was a broad church priest of the Church of England, a university professor, social reformer, historian, novelist and poet. He is particularly associated with Christian socialism, the working ...

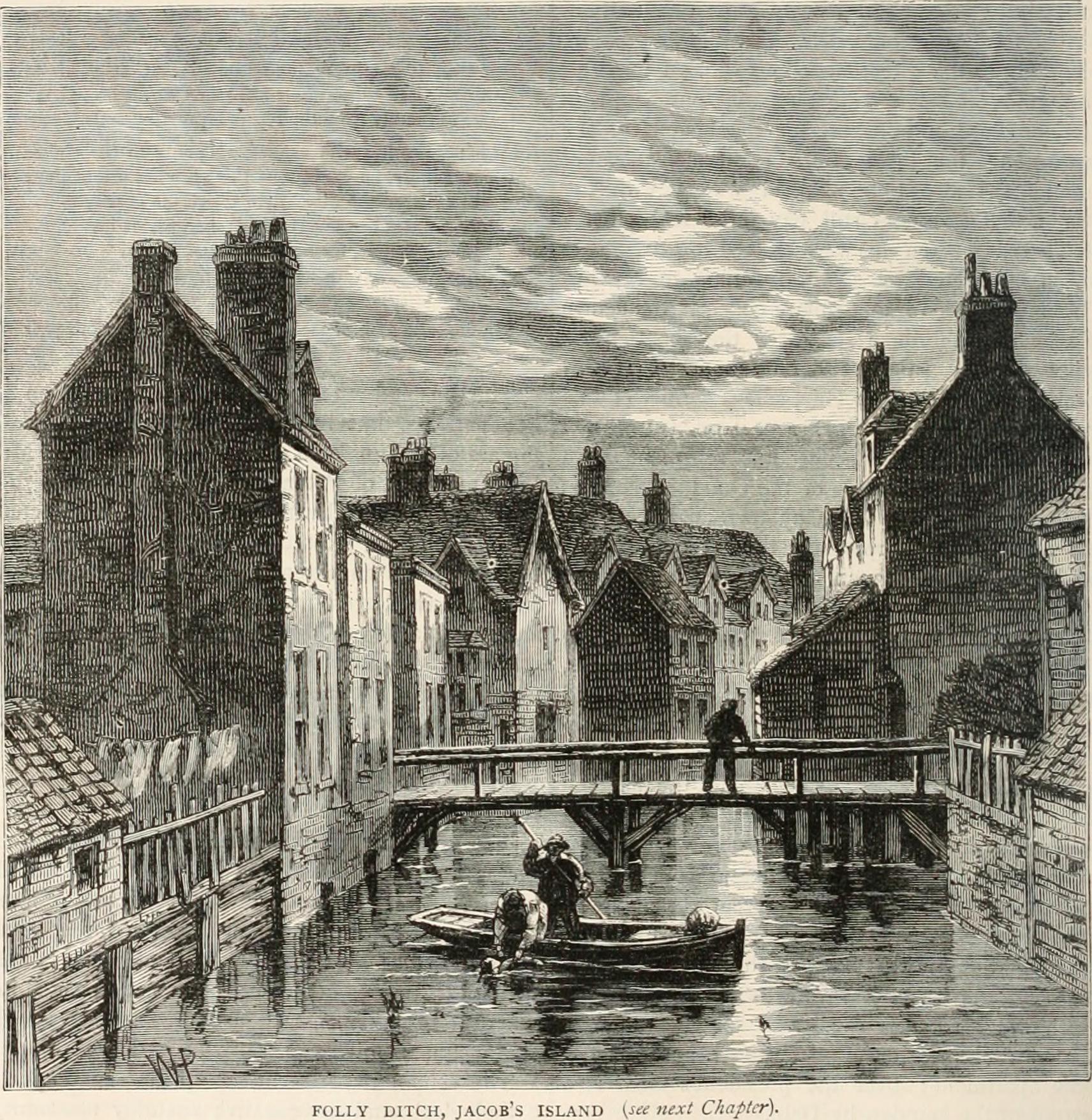

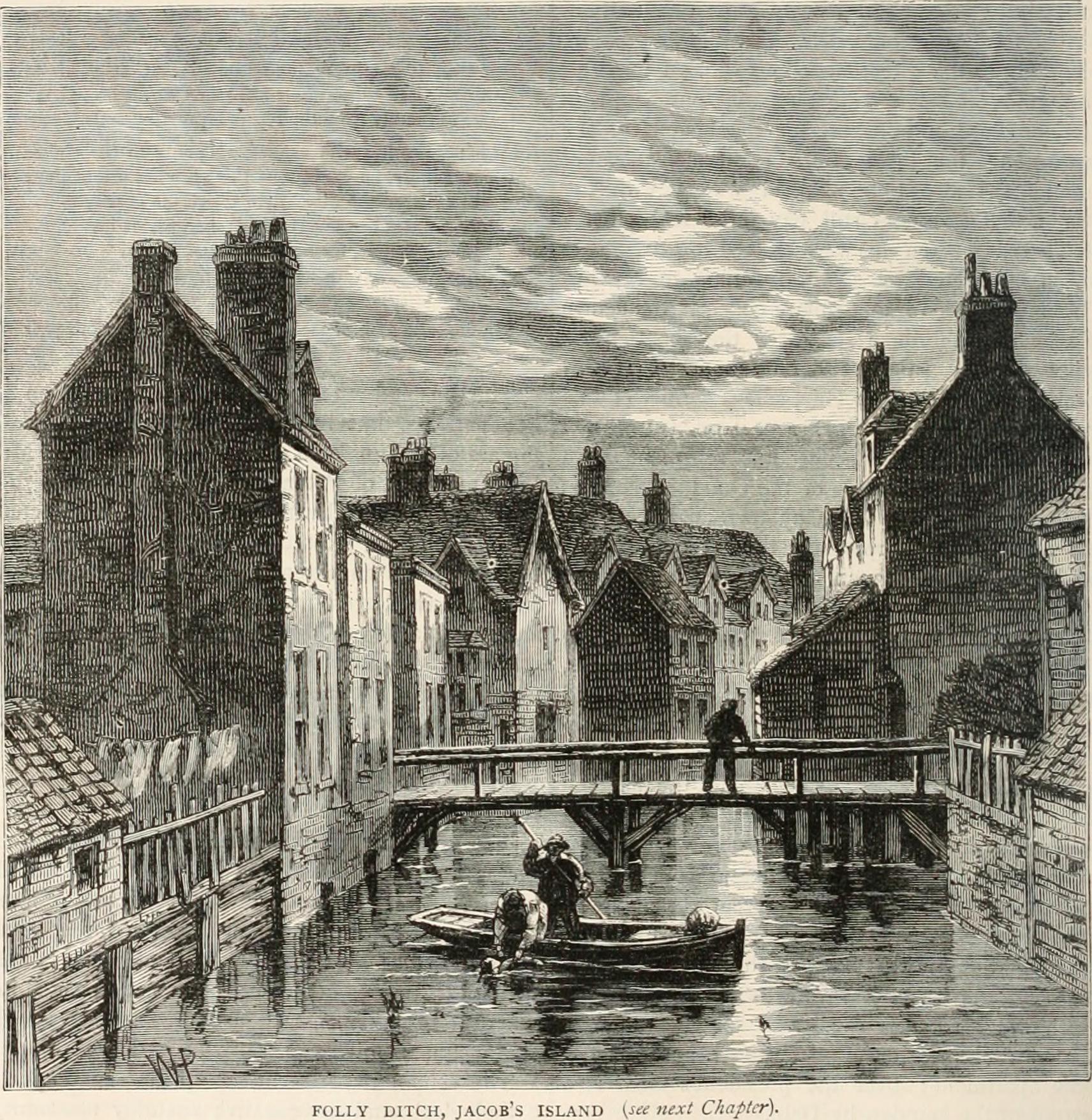

, joined other London areas of "literary-criminal notoriety" that emerged "as symbols of a developing urban counterculture". The 19th century social researcher Henry Mayhew described Jacob's Island as a "pest island" with "literally the smell of a graveyard" and "crazy and rotten bridges" crossing the tidal ditches, with drains from houses discharging directly into them, and the water harbouring masses of rotting weed, animal carcasses and dead fish. He describes the water being "as red as blood" in some parts, as a result of pollutant tanning agents from the leather dressers in the area.

Clearance and redevelopment

In the early 1850s Jacob's Island was gradually removed as part of a slum clearance, starting with the tidal ditches that formed the eastern and southern boundaries being filled. In 1861, the slum was partly destroyed by a fire, and the area later redeveloped as warehouses. In 1865, Richard King, writing in ''A Handbook for Travellers in Surrey, Hampshire, and the Isle of Wight'', observed that "Many of the buildings have been pulled down since ''Oliver Twist'' was written, but the island is still entitled to its bad pre-eminence". A decade later, a missionary for theLondon City Mission

London City Mission was set up by David Nasmith on 16 May 1835 in the Hoxton area of east London. The first paid missionary was Lindsay Burfoot. Today it is part of the wider City Mission Movement.

History

The London City Mission's early work ce ...

provided a more positive report:

Charles William Heckethorn

Charles William Heckethorn (c. 1829 – 13 January 1902) was a Swiss-born, naturalized British, author best known for his history of secret societies which was produced in two editions and translated into German, and his works relating to the hist ...

had reservations about these improvements, telling readers of ''London Souvenirs'' in 1899, that "Many of the horrors of Jacob's Island are now things of the past ... in fact, the romance of the place is gone".

In 1934, a new public housing development called the ''Dickens Estate'' was opened on the site of the former Jacob's Island. The houses of the development were named after Dickens' characters but the only one to have lived, and died, on Jacob's Island, the murderous Bill Sikes

William "Bill" Sikes is a fictional character and the main antagonist in the 1838 novel '' Oliver Twist'' by Charles Dickens. Sikes is a malicious criminal in Fagin's gang, and a vicious robber and murderer. Throughout much of the novel Sikes i ...

, was not honoured.

Fiction

Charles Dickens

Jacob's Island was immortalised by Charles Dickens's novel ''Oliver Twist

''Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress'', Charles Dickens's second novel, was published as a serial from 1837 to 1839, and as a three-volume book in 1838. Born in a workhouse, the orphan Oliver Twist is bound into apprenticeship with ...

'', in which the principal villain Bill Sikes dies in the mud of 'Folly Ditch'. Dickens provides a vivid description of what it was like:

... crazy wooden galleries common to the backs of half a dozen houses, with holes from which to look upon the slime beneath; windows, broken and patched, with poles thrust out, on which to dry the linen that is never there; rooms so small, so filthy, so confined, that the air would seem to be too tainted even for the dirt and squalor which they shelter; wooden chambers thrusting themselves out above the mud and threatening to fall into it – as some have done; dirt-besmeared walls and decaying foundations, every repulsive lineament of poverty, every loathsome indication of filth, rot, and garbage: all these ornament the banks of Jacob's Island.Dickens was taken to this then-impoverished and unsavory location by the officers of the river police, with whom he would occasionally go on patrol.

Dickens wrote in a preface to ''Oliver Twist'', in March 1850, that in the intervening years his descriptions of the disease, crime and poverty of Jacob's Island had come to sound so fanciful to some that

Dickens wrote in a preface to ''Oliver Twist'', in March 1850, that in the intervening years his descriptions of the disease, crime and poverty of Jacob's Island had come to sound so fanciful to some that Sir Peter Laurie

Sir Peter Laurie (3 March 1778 – 3 December 1861) was a British politician who served as Lord Mayor of London.

He was appointed Sheriff of the City of London for 1823 and elected Lord Mayor for 1832. From 1838 until his death, he was Chairman ...

, a former Lord Mayor of London, had expressed his belief publicly that the location was a work of imagination and that no place by that name, or like it, had ever existed. (Laurie had himself been fictionalised, a few years earlier, as ''Alderman Cute'' in Dickens' short novel '' The Chimes'').

Site of 'Bill Sikes' house'

In 1911, the Bermondsey Council opposed a suggestion by the London County Council that ''George's Yard'', in Bermondsey, should be renamed "Twist's Court", to reflect the site of the demise of the Dickens' character Bill Sikes. Nine years later, G. W. Mitchell, a clerk with the Bermondsey Council found a plan dated 5 April 1855, in the London County Council archives, which showed 'Bill Sykes' house' marked on Jacob's Island. This was at a time when the London County Council was proposing that Jacob's Island should be 'demolished'. The following year, it was noted that "so accurately" did Dickens' "describe the scene that the house that he chose for Bill Sikes's end was easily located" in 1855, and "became a Dickens' landmark", leading it to be marked on the Council's plan. At the time of the 1920s news reports, the site of the house, which had been in Metcalf Court as shown in a reproduction of the 1855 plan, was behind 18 Eckell Street (formerly Edwards Street), and "occupied as stables by Messers. R. Chartors and Co.". But "in the time of a Dickens" it overlooked the Folly Ditch on one side and was approached by means of "two wooden bridges across the mill stream', and was "used by thieves of the area". In ''The Mysteries of Paris and London'' (1992), author Richard Maxwell describes a poster in 1846 inviting Jacob's Island residents to celebrate the end of the Corn Laws. Maxwell identifies the location given on the poster of "that highly interesting Spot, described by Charles Dickens" as the site of Bill Sikes' house.Charles Kingsley

In Charles Kingsley's 1850 novel '' Alton Locke'', the title character visits Jacob's Island and sees the death of the drunken Jimmy Downes, who has been reduced to poverty, and the bodies of his family, taken by typhus. Kingsley had been inspired by the accounts of the 1849 cholera epidemics published by ''The Morning Chronicle'' to visit Jacob's Island with his friend

In Charles Kingsley's 1850 novel '' Alton Locke'', the title character visits Jacob's Island and sees the death of the drunken Jimmy Downes, who has been reduced to poverty, and the bodies of his family, taken by typhus. Kingsley had been inspired by the accounts of the 1849 cholera epidemics published by ''The Morning Chronicle'' to visit Jacob's Island with his friend Charles Blachford Mansfield

Charles Blachford Mansfield (8 May 1819 – 26 February 1855) was a British chemist and author.

Early life

He was born on 8 May 1819 at Rowner, Hampshire, where his father, John Mansfield, was rector; his mother was Winifred, eldest daughter of ...

. In addition to his fictional portrayal, Kingsley joined with Mansfield and fellow Christian socialist John Malcolm Forbes Ludlow in purchasing water-carts that were sent to Jacob's Island to supply clean drinking water to the residents.

Current use

The site of the former Jacob's Island was heavily damaged in the Blitz during World War II, when it was extensively bombed by the Luftwaffe due to the industrial presence in the area. Today it is part of the London Borough of Southwark, with only one of the Victorian warehouses surviving. In 1981, the area was one of the first in the

The site of the former Jacob's Island was heavily damaged in the Blitz during World War II, when it was extensively bombed by the Luftwaffe due to the industrial presence in the area. Today it is part of the London Borough of Southwark, with only one of the Victorian warehouses surviving. In 1981, the area was one of the first in the London Docklands

London Docklands is the riverfront and former docks in London. It is located in inner east and southeast London, in the boroughs of London Borough of Southwark, Southwark, London Borough of Tower Hamlets, Tower Hamlets, London Borough of ...

to be converted to expensive loft apartments, which have since been joined by new blocks of luxury flats, including a development by architects Lifschutz Davidson Sandilands

Lifschutz Davidson Sandilands is a practice of architects, urban designers and masterplanners established in 1986 and practising out of London.

History

Alex Lifschutz and Ian Davidson met working on the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank Headquarters ...

.

Since the early 1990s the Jacob's Island area has undergone considerable regeneration and gentrification, with significant friction at times between the new land-based arrivals and the more bohemian

Bohemian or Bohemians may refer to:

*Anything of or relating to Bohemia

Beer

* National Bohemian, a brand brewed by Pabst

* Bohemian, a brand of beer brewed by Molson Coors

Culture and arts

* Bohemianism, an unconventional lifestyle, origin ...

set based in the houseboats moored just offshore at Reed Wharf.

See also

*1854 Broad Street cholera outbreak

Events

January–March

* January 4 – The McDonald Islands are discovered by Captain William McDonald aboard the ''Samarang''.

* January 6 – The fictional detective Sherlock Holmes is perhaps born.

* January 9 – The ...

* List of demolished buildings and structures in London

References

Further reading

*''The Ghost Map

''The Ghost Map: The Story of London's Most Terrifying Epidemic – and How it Changed Science, Cities and the Modern World'' is a book by Steven Berlin Johnson in which he describes the most intense outbreak of cholera in Victorian Londo ...

'' by Steven Johnson, Penguin Books, 2006,

External links

Jacobs Island Residents Association

{{coord, 51.5013, -0.0706, type:landmark_region:GB-SWK, display=title Areas of London Former slums of London History of the London Borough of Southwark Bermondsey