Italian Civil War on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Italian Civil War (

The first groups of partisans were formed in Boves,

The first groups of partisans were formed in Boves,  In late November, the Communists established task forces called '' Distaccamenti d'assalto Garibaldi,'' which later would become ''brigades'' and ''divisions'' whose leadership was entrusted to

In late November, the Communists established task forces called '' Distaccamenti d'assalto Garibaldi,'' which later would become ''brigades'' and ''divisions'' whose leadership was entrusted to

When the Italian Resistance movement began, consisting of various Italian soldiers of disbanded units and many young people not willing to be conscripted into the fascist forces, Mussolini's

When the Italian Resistance movement began, consisting of various Italian soldiers of disbanded units and many young people not willing to be conscripted into the fascist forces, Mussolini's  In Milan, the ''Squadra d'azione'' Ettore Muti (later Autonomous Mobile Legion Ettore Muti) operated under the orders of the former army

In Milan, the ''Squadra d'azione'' Ettore Muti (later Autonomous Mobile Legion Ettore Muti) operated under the orders of the former army

After the victory achieved in the North African campaign, the

After the victory achieved in the North African campaign, the

The Badoglio government began the work of dismantling the fascist state and took measures to maintain order in the country: it dissolved the PNF, maintained the prohibition of the establishment of political parties and imposed martial law. In addition, some

The Badoglio government began the work of dismantling the fascist state and took measures to maintain order in the country: it dissolved the PNF, maintained the prohibition of the establishment of political parties and imposed martial law. In addition, some

In Italy and in the areas of occupation (southern France, the Balkans and Greece), there were hundreds of thousands of soldiers who, in the absence of orders, surrendered without fighting and were deported to Germany, where they were detained as " military internees". Others managed to get civilian clothes and find refuge, benefiting from the numerous demonstrations of solidarity in which the civilian population worked. The cases in which some units reacted successfully to the German aggression were rare and due to the lack of personal initiative of the commanders. In the cities, the scenes in which multitudes of disbanded Italian soldiers were quickly overwhelmed by a few German soldiers provoked anger and despair: it was the sudden defeat suffered at the hands of Italy's former allies, even more than the surrender to the Anglo-Americans, that was perceived as a "new immense

In Italy and in the areas of occupation (southern France, the Balkans and Greece), there were hundreds of thousands of soldiers who, in the absence of orders, surrendered without fighting and were deported to Germany, where they were detained as " military internees". Others managed to get civilian clothes and find refuge, benefiting from the numerous demonstrations of solidarity in which the civilian population worked. The cases in which some units reacted successfully to the German aggression were rare and due to the lack of personal initiative of the commanders. In the cities, the scenes in which multitudes of disbanded Italian soldiers were quickly overwhelmed by a few German soldiers provoked anger and despair: it was the sudden defeat suffered at the hands of Italy's former allies, even more than the surrender to the Anglo-Americans, that was perceived as a "new immense

In the days immediately following the armistice, with the eclipse of the power of the royal state, the two sides of the civil war began to take shape, the partisans and the fascists, both convinced that they legitimately represented Italy. Many of those who took up arms were caught by surprise by the armistice on one side or the other almost by chance and had to make their choice of side on the basis of circumstances. The decision was made more dramatic by the isolation in which it took place, since in the face of the collapse of the state there was no longer the possibility of referring to an authority, but only to one's own values. Of course, the choices were not all instantaneous and based on absolute certainties, rather "a nothing, a false step, a soaring of the soul" was enough to find oneself on the other side.

The choice was particularly burdensome for the military, bound on the one hand to honor their oath to the king and on the other to respect the alliance with the Germans, in both cases the penalty for their honor as soldiers; some solved the problem by appealing to their conscience: some, considering the oath to the King dissolved due to his behavior, presented themselves to the German commands asking to be enlisted, receiving as a badge an armband with a tricolor and the inscription ''Dienst der Deutschen Wehrmacht'' ("in the service of the German Wehrmacht"); others, while also considering themselves no longer bound by the oath to the King, still chose not to side with the Axis.

The historian Santo Peli writes that, after 8 September, the Italian soldiers captured by the Germanic armed forces were more than 800,000; of them about 186,000 chose to collaborate in various capacities with the Germans. "For the remaining, more than six hundred thousand, who initially refused to remain "faithful to the alliance", the doors of the camps are opened wide. ..In the camps located in territories under the jurisdiction of the Wehrmacht, in February 1944, 615812 former Italian soldiers were still imprisoned, who had refused any collaboration with the German and fascist armed forces".

In some cases the fate after 25 July was also decisive, as happened to the future partisan commander

In the days immediately following the armistice, with the eclipse of the power of the royal state, the two sides of the civil war began to take shape, the partisans and the fascists, both convinced that they legitimately represented Italy. Many of those who took up arms were caught by surprise by the armistice on one side or the other almost by chance and had to make their choice of side on the basis of circumstances. The decision was made more dramatic by the isolation in which it took place, since in the face of the collapse of the state there was no longer the possibility of referring to an authority, but only to one's own values. Of course, the choices were not all instantaneous and based on absolute certainties, rather "a nothing, a false step, a soaring of the soul" was enough to find oneself on the other side.

The choice was particularly burdensome for the military, bound on the one hand to honor their oath to the king and on the other to respect the alliance with the Germans, in both cases the penalty for their honor as soldiers; some solved the problem by appealing to their conscience: some, considering the oath to the King dissolved due to his behavior, presented themselves to the German commands asking to be enlisted, receiving as a badge an armband with a tricolor and the inscription ''Dienst der Deutschen Wehrmacht'' ("in the service of the German Wehrmacht"); others, while also considering themselves no longer bound by the oath to the King, still chose not to side with the Axis.

The historian Santo Peli writes that, after 8 September, the Italian soldiers captured by the Germanic armed forces were more than 800,000; of them about 186,000 chose to collaborate in various capacities with the Germans. "For the remaining, more than six hundred thousand, who initially refused to remain "faithful to the alliance", the doors of the camps are opened wide. ..In the camps located in territories under the jurisdiction of the Wehrmacht, in February 1944, 615812 former Italian soldiers were still imprisoned, who had refused any collaboration with the German and fascist armed forces".

In some cases the fate after 25 July was also decisive, as happened to the future partisan commander

The civil conflict fought between fascists and partisans rarely involved the armed forces of the Italian Social Republic and the Kingdom of Italy in direct clashes. The two Italian states in principle avoided deploying their own units at the front against the other's units. In some cases, however, Italian soldiers found themselves fighting other Italians: the ''Forlì'' Battalions Group of RSI framed in the 278th German Division faced the marines of the ''Folgore'' Combat Group of the Royal Army, with whom there were also clashes with dead and wounded, and that of the ''Cremona'' Combat Group, whose Battalion I collided with the remains of the retreating Decima MAS ''Barbarigo'' Battalion, in Ariano nel Polesine, Santa Maria in Punta in the Polesine.

In the south, a fascist resistance movement against the Anglo-Americans also developed, which nevertheless had neither the extension nor the popular support of the anti-fascist one in the north. The press of the RSI propandistically magnified its entity through the figure of O 'Scugnizzo, a second lieutenant who worked in the south behind enemy lines, also the protagonist of a comic strip by Guido Zamperoni. Despite the attempts by Alessandro Pavolini to create real military units that operated with partisan tactics behind the allied lines, by Mussolini's express will the activity of the fascist resistance movement in the south was limited to espionage, propaganda and sabotage against occupation troops. There were cases of murder, such as that of the consul general of the militia Gianni Cagnoni, killed - presumably by the fascists for his activity as a double agent in intelligence with the allied secret services - in

The civil conflict fought between fascists and partisans rarely involved the armed forces of the Italian Social Republic and the Kingdom of Italy in direct clashes. The two Italian states in principle avoided deploying their own units at the front against the other's units. In some cases, however, Italian soldiers found themselves fighting other Italians: the ''Forlì'' Battalions Group of RSI framed in the 278th German Division faced the marines of the ''Folgore'' Combat Group of the Royal Army, with whom there were also clashes with dead and wounded, and that of the ''Cremona'' Combat Group, whose Battalion I collided with the remains of the retreating Decima MAS ''Barbarigo'' Battalion, in Ariano nel Polesine, Santa Maria in Punta in the Polesine.

In the south, a fascist resistance movement against the Anglo-Americans also developed, which nevertheless had neither the extension nor the popular support of the anti-fascist one in the north. The press of the RSI propandistically magnified its entity through the figure of O 'Scugnizzo, a second lieutenant who worked in the south behind enemy lines, also the protagonist of a comic strip by Guido Zamperoni. Despite the attempts by Alessandro Pavolini to create real military units that operated with partisan tactics behind the allied lines, by Mussolini's express will the activity of the fascist resistance movement in the south was limited to espionage, propaganda and sabotage against occupation troops. There were cases of murder, such as that of the consul general of the militia Gianni Cagnoni, killed - presumably by the fascists for his activity as a double agent in intelligence with the allied secret services - in

Among the most significant bloody events that occurred in the phase immediately following the establishment of the Italian Social Republic was the killing of the federal Igino Ghisellini, which took place on 14 November 1943. During the Congress of Verona (1943), Congress of Verona of the Republican Fascist Party, the news that Ghisellini had been killed provoked a mob reaction that resulted in retaliation on eleven anti-fascists unrelated to the assassination, a gesture defined as "stupid and bestial" by Mussolini himself. Such was the negative impression that this episode was raised as the "first murder of the civil war" and as the end of any hope "of reconciliation of the Italians".

Regardless of who physically fired "the first shot",

Among the most significant bloody events that occurred in the phase immediately following the establishment of the Italian Social Republic was the killing of the federal Igino Ghisellini, which took place on 14 November 1943. During the Congress of Verona (1943), Congress of Verona of the Republican Fascist Party, the news that Ghisellini had been killed provoked a mob reaction that resulted in retaliation on eleven anti-fascists unrelated to the assassination, a gesture defined as "stupid and bestial" by Mussolini himself. Such was the negative impression that this episode was raised as the "first murder of the civil war" and as the end of any hope "of reconciliation of the Italians".

Regardless of who physically fired "the first shot",  The most important military operation in which the brigades took part was the action, successfully carried out in concert with the National Republican Guard (Italy), National Republican Guard and German units, of the reconquest of the Ossola Valley and the destruction of the homonymous partisan republic. The need for the Italian Social Republic to maintain order and reassert sovereignty over the territory was also imperative to be able to manage relations with the Germans, in order to try to regain positions and at the same time prevent the German authorities - with the excuse of having to secure the rear to their armies - from bypassing the fascist authorities. Despite all efforts, this objective was missed, and the increasingly harsh outbreak of the civil war, combined with the inability of the fascists to independently maintain public order and oppose the partisans, allowed the Germans to erode even the little power that the RSI had managed to get.

In this "three-way" war, the Germans maintained an ambiguous attitude, not hesitating to sacrifice the Fascists in the name of quiet living with the partisans. In several cases, the Germans offered the partisan commands with whom they had come in contact "carte blanche" in their actions against the fascists, provided that the Germanic units were spared. Although many of the partisan commanders rejected similar agreements, the climate of "hatred against the fascists over that against the Germans" seems to prevail in the context of the motivations that pushed the partisans to fight. This kind of motivation was prevalent among the partisans of the shareholder area, while some Communist commissioners nonetheless viewed with concern the possibility of a "clouding of the national character of the struggle". In other cases, local agreements were sometimes reached, especially with non-shareholder or communist partisan elements, for example the Green Flames, with tactical purposes or to achieve a patriotic modus vivendi or even with temporary alliances "for the struggle extremist gangs and common criminals" present in large areas of the country.

These contacts obtained the result of provoking bitter contrasts within both sides: the partisan formations accused each other of intelligence with the enemy, and of exploiting temporary truces with the Nazi-fascists to the detriment of partisan units of different ideological alignments, or of wanting to keep leaving the bulk of the losses to others, waiting for the right moment for a showdown. In particular, shareholders and communists in their complaints show the fear of close ties behind them between "center and right" partisans with the Nazi-fascists. Furthermore, the communists believed that the autonomous partisans, due to the anti-communism of their commanders, could become the Italian equivalents of the Chetniks, monarchical Yugoslav partisans in sharp contrast with the communist partisans of Josip Broz Tito, Tito.

The Porzûs massacre saw communist partisans of the ''Natisone'' division (of the SAP brigade ''13 martiri di Feletto''), attached to the Yugoslavian XI Corpus by orders of Palmiro Togliatti, massacre 20 partisans and a woman at the HQ of one of the many Catholic Osoppo Brigades, claiming that they were German spies. Among the dead were commander Francesco De Gregori (uncle of the singer Francesco De Gregori) and brigade commissioner Gastone Valente.

The problem of the civil war between Italians was deeply felt by both warring factions: many had strong conscientious objections to this type of war, but many were also intransigent. Furthermore, although the Anglo-American military commands did not at all want an oversized growth of the partisan movement and its military commitment beyond the allied needs (essentially: espionage and information gathering; sabotage; rescue of agents, downed pilots, and allied fugitives), the allied propaganda radios (Radio Algeri, Radio Londra, Radio Milano Libertà, Radio Bari) openly incited the murder of exponents of republican fascism, issuing intimidating warnings and disseminating news about their domiciles, habits, acquaintances, and any coverings of these, so that they would feel perennially hunted down.

The forces of the Italian Social Republic struggled to keep the insurgency under wraps, resulting in a heavy toll on the German occupation forces stationed to buttress them. Field Marshall Albert Kesselring estimated that from June to August 1944 alone, Italian partisans inflicted a minimum of 20,000 casualties on the Germans (5,000 killed, 7,000 to 8,000 captured/missing, and the same number wounded), while suffering far lower casualties themselves. Kesselring's intelligence officer supplied a higher figure of 30,000 - 35,000 casualties from partisan activity in those three months (which Kesselring considered too high): 5,000 killed and 25,000-30,000 missing or wounded.

The most important military operation in which the brigades took part was the action, successfully carried out in concert with the National Republican Guard (Italy), National Republican Guard and German units, of the reconquest of the Ossola Valley and the destruction of the homonymous partisan republic. The need for the Italian Social Republic to maintain order and reassert sovereignty over the territory was also imperative to be able to manage relations with the Germans, in order to try to regain positions and at the same time prevent the German authorities - with the excuse of having to secure the rear to their armies - from bypassing the fascist authorities. Despite all efforts, this objective was missed, and the increasingly harsh outbreak of the civil war, combined with the inability of the fascists to independently maintain public order and oppose the partisans, allowed the Germans to erode even the little power that the RSI had managed to get.

In this "three-way" war, the Germans maintained an ambiguous attitude, not hesitating to sacrifice the Fascists in the name of quiet living with the partisans. In several cases, the Germans offered the partisan commands with whom they had come in contact "carte blanche" in their actions against the fascists, provided that the Germanic units were spared. Although many of the partisan commanders rejected similar agreements, the climate of "hatred against the fascists over that against the Germans" seems to prevail in the context of the motivations that pushed the partisans to fight. This kind of motivation was prevalent among the partisans of the shareholder area, while some Communist commissioners nonetheless viewed with concern the possibility of a "clouding of the national character of the struggle". In other cases, local agreements were sometimes reached, especially with non-shareholder or communist partisan elements, for example the Green Flames, with tactical purposes or to achieve a patriotic modus vivendi or even with temporary alliances "for the struggle extremist gangs and common criminals" present in large areas of the country.

These contacts obtained the result of provoking bitter contrasts within both sides: the partisan formations accused each other of intelligence with the enemy, and of exploiting temporary truces with the Nazi-fascists to the detriment of partisan units of different ideological alignments, or of wanting to keep leaving the bulk of the losses to others, waiting for the right moment for a showdown. In particular, shareholders and communists in their complaints show the fear of close ties behind them between "center and right" partisans with the Nazi-fascists. Furthermore, the communists believed that the autonomous partisans, due to the anti-communism of their commanders, could become the Italian equivalents of the Chetniks, monarchical Yugoslav partisans in sharp contrast with the communist partisans of Josip Broz Tito, Tito.

The Porzûs massacre saw communist partisans of the ''Natisone'' division (of the SAP brigade ''13 martiri di Feletto''), attached to the Yugoslavian XI Corpus by orders of Palmiro Togliatti, massacre 20 partisans and a woman at the HQ of one of the many Catholic Osoppo Brigades, claiming that they were German spies. Among the dead were commander Francesco De Gregori (uncle of the singer Francesco De Gregori) and brigade commissioner Gastone Valente.

The problem of the civil war between Italians was deeply felt by both warring factions: many had strong conscientious objections to this type of war, but many were also intransigent. Furthermore, although the Anglo-American military commands did not at all want an oversized growth of the partisan movement and its military commitment beyond the allied needs (essentially: espionage and information gathering; sabotage; rescue of agents, downed pilots, and allied fugitives), the allied propaganda radios (Radio Algeri, Radio Londra, Radio Milano Libertà, Radio Bari) openly incited the murder of exponents of republican fascism, issuing intimidating warnings and disseminating news about their domiciles, habits, acquaintances, and any coverings of these, so that they would feel perennially hunted down.

The forces of the Italian Social Republic struggled to keep the insurgency under wraps, resulting in a heavy toll on the German occupation forces stationed to buttress them. Field Marshall Albert Kesselring estimated that from June to August 1944 alone, Italian partisans inflicted a minimum of 20,000 casualties on the Germans (5,000 killed, 7,000 to 8,000 captured/missing, and the same number wounded), while suffering far lower casualties themselves. Kesselring's intelligence officer supplied a higher figure of 30,000 - 35,000 casualties from partisan activity in those three months (which Kesselring considered too high): 5,000 killed and 25,000-30,000 missing or wounded.

Among the first to form, there was the gang of the federals Guido Bardi and Guglielmo Pollastrini in Rome, whose crude and vulgar methods scandalized even the Germans. Subsequently, the Koch Band was very active in Rome and contributed to dismantling the structure of the Action Party in the capital. The so-called ''Banda Koch'', led by

Among the first to form, there was the gang of the federals Guido Bardi and Guglielmo Pollastrini in Rome, whose crude and vulgar methods scandalized even the Germans. Subsequently, the Koch Band was very active in Rome and contributed to dismantling the structure of the Action Party in the capital. The so-called ''Banda Koch'', led by

The Social Republic had only a few days left, and Mussolini was agitated between various options. He was trying to initiate socialization, to leave Italy a socialist legacy (the "dragon eggs"), also as a final revenge against the "plutocracies". On the military level, while Diamanti and Borghese proposed to wait for the inevitable surrender of a weapon in the foot, Pavolini and Costa continued to advocate the idea of extreme Valtellina Redoubt, resistance in Valtellina, while Graziani still remained convinced that the German troops were fighting loyally alongside those of CSR and rejected any hypothesis of an agreement that would have allowed the Germans for the second time to accuse Italy of treason.

After an unsuccessful attempt on the afternoon of 25 April to negotiate with the National Liberation Committee for Northern Italy exponents with the mediation of Cardinal Schuster and disoriented by the discovery of Wolff's secret negotiations with the Anglo-Americans, Mussolini decided to leave Milan in the direction of Lake Como at 8 PM, for reasons that are still not clear.

On the same day, while the gun battles between insurgents and Italian Social Republic and German forces multiplied,

The Social Republic had only a few days left, and Mussolini was agitated between various options. He was trying to initiate socialization, to leave Italy a socialist legacy (the "dragon eggs"), also as a final revenge against the "plutocracies". On the military level, while Diamanti and Borghese proposed to wait for the inevitable surrender of a weapon in the foot, Pavolini and Costa continued to advocate the idea of extreme Valtellina Redoubt, resistance in Valtellina, while Graziani still remained convinced that the German troops were fighting loyally alongside those of CSR and rejected any hypothesis of an agreement that would have allowed the Germans for the second time to accuse Italy of treason.

After an unsuccessful attempt on the afternoon of 25 April to negotiate with the National Liberation Committee for Northern Italy exponents with the mediation of Cardinal Schuster and disoriented by the discovery of Wolff's secret negotiations with the Anglo-Americans, Mussolini decided to leave Milan in the direction of Lake Como at 8 PM, for reasons that are still not clear.

On the same day, while the gun battles between insurgents and Italian Social Republic and German forces multiplied,

In Genoa, the commander of the square, General Meinhold, unsuccessfully tried to negotiate with the partisans of the Garibaldian Pinan-Cichero brigade stationed in the mountains near the city, while the vessel captain Bernighaus organized the destruction of the port. After violent clashes in the center between the GAP squads and the Garibaldini of the Balilla brigade and the German and Fascist units, General Meinhold signed the surrender of the garrison at 19.30 on 25 April. The captain of the vessel Berlinghaus and the captain Mario Arillo of the 10th MAS nevertheless continued the resistance, determined to carry out the planned destruction; after new clashes with the partisans of Cichero and Mingo who went down to the city on the evening of 26 April, the last Nazi-Fascist units surrendered. The partisans had saved the port from destruction and captured 6,000 prisoners, who were handed over to the allies, who arrived in Nervi on 27 April.

In Turin, while some Nazi-Fascist columns were heading towards Ivrea, to wait for the allies and surrender, the Italian Social Republic departments gathered some forces and engaged in bitter clashes with the partisans who reached the city from the mountains on 28 April. The German military columns managed to fold back through the town. So, while some departments of the Italian Social Republic were leaving the Piedmontese capital to go to Valtellina, the bulk of the Turin fascists who remained in arms decided to continue fighting. The Garibaldi brigades of "Nanni", the autonomous ones of "Enrico Martini, Mauri", and the "Justice and Freedom" departments freed a large part of the city after violent fighting and safeguarded the bridges awaiting the arrival of the allies, who arrived in Turin on May 1.

On the evening of 25 April,

In Genoa, the commander of the square, General Meinhold, unsuccessfully tried to negotiate with the partisans of the Garibaldian Pinan-Cichero brigade stationed in the mountains near the city, while the vessel captain Bernighaus organized the destruction of the port. After violent clashes in the center between the GAP squads and the Garibaldini of the Balilla brigade and the German and Fascist units, General Meinhold signed the surrender of the garrison at 19.30 on 25 April. The captain of the vessel Berlinghaus and the captain Mario Arillo of the 10th MAS nevertheless continued the resistance, determined to carry out the planned destruction; after new clashes with the partisans of Cichero and Mingo who went down to the city on the evening of 26 April, the last Nazi-Fascist units surrendered. The partisans had saved the port from destruction and captured 6,000 prisoners, who were handed over to the allies, who arrived in Nervi on 27 April.

In Turin, while some Nazi-Fascist columns were heading towards Ivrea, to wait for the allies and surrender, the Italian Social Republic departments gathered some forces and engaged in bitter clashes with the partisans who reached the city from the mountains on 28 April. The German military columns managed to fold back through the town. So, while some departments of the Italian Social Republic were leaving the Piedmontese capital to go to Valtellina, the bulk of the Turin fascists who remained in arms decided to continue fighting. The Garibaldi brigades of "Nanni", the autonomous ones of "Enrico Martini, Mauri", and the "Justice and Freedom" departments freed a large part of the city after violent fighting and safeguarded the bridges awaiting the arrival of the allies, who arrived in Turin on May 1.

On the evening of 25 April,

On the evening of 25 April, Mussolini left Milan, followed by a column of fascists, determined to reach Valtellina. After a stop in Como and several confused movements along the western coast of the lake, the fascist column, which had joined a German anti-aircraft unit, was stopped by the partisans. Mussolini was arrested and taken - together with his mistress Clara Petacci, Claretta Petacci - to Bonzanigo, a ''frazione'' of Mezzegra, where he spent the night between 27 and 28 April.

On 28 April, Mussolini, Petacci, and sixteen other leaders and members of the fascist column were killed by the partisans on the Dongo lakefront. There are controversial hypotheses and interpretations on the modalities of Mussolini's killing, on who ordered it and who actually carried it out. Subsequently, the eighteen corpses were transported to Milan, where on the 29th, exposed in Piazzale Loreto (site of a previous bloody fascist reprisal), they outraged the crowd.

On the evening of 25 April, Mussolini left Milan, followed by a column of fascists, determined to reach Valtellina. After a stop in Como and several confused movements along the western coast of the lake, the fascist column, which had joined a German anti-aircraft unit, was stopped by the partisans. Mussolini was arrested and taken - together with his mistress Clara Petacci, Claretta Petacci - to Bonzanigo, a ''frazione'' of Mezzegra, where he spent the night between 27 and 28 April.

On 28 April, Mussolini, Petacci, and sixteen other leaders and members of the fascist column were killed by the partisans on the Dongo lakefront. There are controversial hypotheses and interpretations on the modalities of Mussolini's killing, on who ordered it and who actually carried it out. Subsequently, the eighteen corpses were transported to Milan, where on the 29th, exposed in Piazzale Loreto (site of a previous bloody fascist reprisal), they outraged the crowd.

The executions of the exponents of the Italian Social Republic took place quickly and with summary procedures also because - having ascertained the failure to renew the cadres of the old regime in royal Italy - the partisan leaders feared that the definitive transfer of powers to the Anglo-Americans and the return to "legality bourgeois" would have prevented a radical purge. This desire to speed up times is witnessed in a letter in which the shareholder Giorgio Agosti writes to party mate Dante Livio Bianco, commander of the Giustizia e Libertà formations, that "we need... before the Allied arrival, a St. Bartholomew's Day massacre, San Bartolomeo di fascists that take away the desire to start over for a good number of years ".

The death sentences for collaborationism in some cases also hit innocent people accused without evidence, as in the cases of the actors Elio Marcuzzo (of anti-fascist faith) and Luisa Ferida. In the climate of insurrectional violence, there were also murders linked to private events. In fact, the victims included not only personalities linked to the Republican Fascist Party, belonging to the armed departments of the

The executions of the exponents of the Italian Social Republic took place quickly and with summary procedures also because - having ascertained the failure to renew the cadres of the old regime in royal Italy - the partisan leaders feared that the definitive transfer of powers to the Anglo-Americans and the return to "legality bourgeois" would have prevented a radical purge. This desire to speed up times is witnessed in a letter in which the shareholder Giorgio Agosti writes to party mate Dante Livio Bianco, commander of the Giustizia e Libertà formations, that "we need... before the Allied arrival, a St. Bartholomew's Day massacre, San Bartolomeo di fascists that take away the desire to start over for a good number of years ".

The death sentences for collaborationism in some cases also hit innocent people accused without evidence, as in the cases of the actors Elio Marcuzzo (of anti-fascist faith) and Luisa Ferida. In the climate of insurrectional violence, there were also murders linked to private events. In fact, the victims included not only personalities linked to the Republican Fascist Party, belonging to the armed departments of the

Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

: ''Guerra civile italiana'', ) was a civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

in the Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy ( it, Regno d'Italia) was a state that existed from 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 1946, when civil discontent led to ...

fought during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

by Italian Fascists against the Italian partisans

The Italian resistance movement (the ''Resistenza italiana'' and ''la Resistenza'') is an umbrella term for the Italian resistance groups who fought the occupying forces of Nazi Germany and the fascist collaborationists of the Italian Social ...

(mostly politically organized in the National Liberation Committee

The National Liberation Committee ( it, Comitato di Liberazione Nazionale, CLN) was a political umbrella organization and the main representative of the Italian resistance movement fighting against Nazi Germany’s forces during the German occup ...

) and, to a lesser extent, the Italian Co-Belligerent Army. Many of the Italian Fascists were soldiers or supporters of the Italian Social Republic

The Italian Social Republic ( it, Repubblica Sociale Italiana, ; RSI), known as the National Republican State of Italy ( it, Stato Nazionale Repubblicano d'Italia, SNRI) prior to December 1943 but more popularly known as the Republic of Salò ...

, a collaborationist puppet state

A puppet state, puppet régime, puppet government or dummy government, is a State (polity), state that is ''de jure'' independent but ''de facto'' completely dependent upon an outside Power (international relations), power and subject to its o ...

created under the direction of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

during its occupation of Italy. The Italian Civil War lasted from around 8 September 1943 (the date of the Armistice of Cassibile

The Armistice of Cassibile was an armistice signed on 3 September 1943 and made public on 8 September between the Kingdom of Italy and the Allies during World War II.

It was signed by Major General Walter Bedell Smith for the Allies and Brig ...

) to 2 May 1945 (date of the Surrender of Caserta). The Italian partisans and the Italian Co-Belligerent Army of the Kingdom of Italy, sometimes materially supported by the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

, simultaneously fought against the occupying Nazi German

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

armed forces. Armed clashes between the Fascist National Republican Army

The National Republican Army (Esercito Nazionale Repubblicano, or ENR) was the army of the Italian Social Republic ( it, Repubblica Sociale Italiana, or RSI) from 1943 to 1945 that fought on the side of Nazi Germany during World War II.

The EN ...

of the Italian Social Republic and the Italian Co-Belligerent Army of the Kingdom of Italy were rare,. while clashes between the Italian Fascists and the Italian partisans were common; meanwhile, there was some internal conflict within the partisan movement. In this context, Germans, sometimes helped by Italian Fascists, committed several atrocities against Italian civilians and troops.

The event that later gave rise to the Italian Civil War was the deposition and arrest of Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

on 25 July 1943 by King Victor Emmanuel III

The name Victor or Viktor may refer to:

* Victor (name), including a list of people with the given name, mononym, or surname

Arts and entertainment

Film

* ''Victor'' (1951 film), a French drama film

* ''Victor'' (1993 film), a French shor ...

, after which Italy signed the Armistice of Cassibile on 8 September 1943, ending its war with the Allies. However, German forces began occupying Italy immediately prior to the armistice, through Operation Achse

Operation Achse (german: Fall Achse, lit=Case Axis), originally called Operation Alaric (), was the codename for the German operation to forcibly disarm the Italian armed forces after Italy's armistice with the Allies on 3 September 1943.

S ...

, and then invaded and occupied Italy on a larger scale after the armistice, taking control of northern and central Italy and creating the Italian Social Republic (RSI), with Mussolini installed as leader after he was rescued by German paratroopers in the Gran Sasso raid

During World War II, the Gran Sasso raid (codenamed ''Unternehmen Eiche'', , literally "Operation Oak", by the German military) on 12 September 1943 was a successful operation by German paratroopers and ''Waffen-SS'' commandos to rescue the dep ...

. As a result, the Italian Co-Belligerent Army was created to fight against the Germans, while other Italian troops, loyal to Mussolini, continued to fight alongside the Germans in the National Republican Army. In addition, a large Italian resistance movement

The Italian resistance movement (the ''Resistenza italiana'' and ''la Resistenza'') is an umbrella term for the Italian resistance groups who fought the occupying forces of Nazi Germany and the fascist collaborationists of the Italian Social ...

started a guerrilla war

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare in which small groups of combatants, such as paramilitary personnel, armed civilians, or irregulars, use military tactics including ambushes, sabotage, raids, petty warfare, hit-and-run tactic ...

against the German and Italian fascist forces. The anti-fascist victory led to the execution of Mussolini

The death of Benito Mussolini, the deposed Italian fascist dictator, occurred on 28 April 1945, in the final days of World War II in Europe, when he was summarily executed by an Italian partisan in the small village of Giulino di Mezzegra in ...

, the liberation of the country from dictatorship, and the birth of the Italian Republic

An institutional referendum ( it, referendum istituzionale, or ) was held in Italy on 2 June 1946, Dieter Nohlen & Philip Stöver (2010) ''Elections in Europe: A data handbook'', p1047 a key event of Italian contemporary history.

Until 194 ...

under the control of the Allied Military Government of Occupied Territories, which was operational until the Treaty of Peace with Italy in 1947.

Terminology

Although other European countries such asNorway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and t ...

, the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

, and France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

also had partisan movements and collaborationist governments with Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

, armed confrontation between compatriots was most intense in Italy, making the Italian case unique. In 1965, the definition of "civil war" was used for the first time by fascist politician and historian Giorgio Pisanò in his books,

while Claudio Pavone

Claudio Pavone (30 November 1920 – 29 November 2016) was an Italian historian and archivist.

Pavone was the president of the Historic Institute of the Liberation movement in Italy, the president of the Italian Society of Contemporary History an ...

's book ''Una guerra civile. Saggio storico sulla moralità della Resistenza'' (''A Civil War. Historical Essay On the Morality Of the Resistance''), published in 1991, led the term "Italian Civil War" to become a widespread term used in Italian and international historiography.

Factions

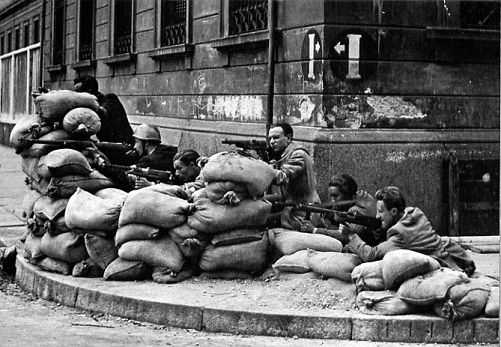

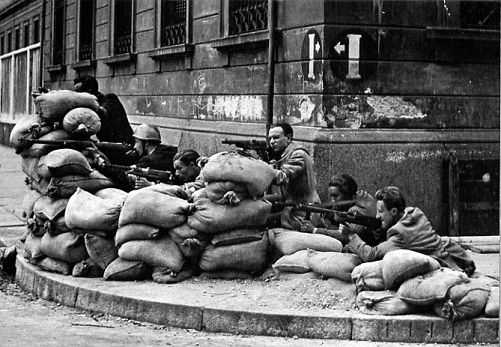

The confrontations between the factions resulted in the torture and death of many civilians. During the Italian Campaign, partisans were supplied with small arms, ammunition and explosives by theWestern Allies

The Allies, formally referred to as the United Nations from 1942, were an international military coalition formed during the Second World War (1939–1945) to oppose the Axis powers, led by Nazi Germany, Imperial Japan, and Fascist Italy ...

. Allied forces and partisans cooperated on military missions, parachuting or landing personnel behind enemy lines, often including Italian-American

Italian Americans ( it, italoamericani or ''italo-americani'', ) are Americans who have full or partial Italian ancestry. The largest concentrations of Italian Americans are in the urban Northeast and industrial Midwestern metropolitan areas, w ...

members of OSS. Other operations were carried out exclusively by secret service personnel. Where possible, both sides avoided situations in which Italian units of opposite fronts were involved in combat episodes.

Partisans

The first groups of partisans were formed in Boves,

The first groups of partisans were formed in Boves, Piedmont

it, Piemontese

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 ...

, and Bosco Martese, Abruzzo

Abruzzo (, , ; nap, label=Neapolitan language, Abruzzese Neapolitan, Abbrùzze , ''Abbrìzze'' or ''Abbrèzze'' ; nap, label=Sabino dialect, Aquilano, Abbrùzzu; #History, historically Abruzzi) is a Regions of Italy, region of Southern Italy wi ...

. Other groups, composed mainly of Slavs

Slavs are the largest European ethnolinguistic group. They speak the various Slavic languages, belonging to the larger Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout northern Eurasia, main ...

and communists

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a so ...

, sprang up in the Julian March

Venezia Giulia, traditionally called Julian March (Serbo-Croatian, Slovene: ''Julijska krajina'') or Julian Venetia ( it, Venezia Giulia; vec, Venesia Julia; fur, Vignesie Julie; german: Julisch Venetien) is an area of southeastern Europe wh ...

. Others grew around Allied prisoners of war, released or escaped from captivity following the events of 8 September. These first organized units soon dissolved because of the rapid German reaction. In Boves, on 19 September 1943, the Nazis committed their first massacre on Italian territory.

On 8 September, hours after the radio announcement of the armistice, the representatives of several antifascist organizations converged on Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

. They were Mauro Scoccimarro

Mauro Scoccimarro (30 October 1895 – 2 January 1972) was an Italian economist and communist politician. He was one of the founders of the Italian Communist Party and the minister of finance between 1945 and 1947.

Early life and education

Scocc ...

and Giorgio Amendola

Giorgio Amendola (21 November 1907 – 5 June 1980) was an Italian writer and politician. He is regarded and often cited as one of the main precursors of the Olive Tree. Born in Rome in 1907, Amendola was the son of Lithuanian intellectual Eva K ...

(Italian Communist Party

The Italian Communist Party ( it, Partito Comunista Italiano, PCI) was a communist political party in Italy.

The PCI was founded as ''Communist Party of Italy'' on 21 January 1921 in Livorno by seceding from the Italian Socialist Party (PSI). ...

), Alcide De Gasperi

Alcide Amedeo Francesco De Gasperi (; 3 April 1881 – 19 August 1954) was an Italian politician who founded the Christian Democracy party and served as prime minister of Italy in eight successive coalition governments from 1945 to 1953.

De Gasp ...

(Christian Democracy

Christian democracy (sometimes named Centrist democracy) is a political ideology that emerged in 19th-century Europe under the influence of Catholic social teaching and neo-Calvinism.

It was conceived as a combination of modern democratic ...

), Ugo La Malfa

Ugo La Malfa (16 May 1903 – 26 March 1979) was an Italian politician and an important leader of the Italian Republican Party (''Partito Repubblicano Italiano''; PRI).

Early years and anti-fascist resistance

La Malfa was born in Palermo, Sic ...

and Sergio Fenoaltea ( Action Party), Pietro Nenni

Pietro Sandro Nenni (; 9 February 1891 – 1 January 1980) was an Italian socialist politician, the national secretary of the Italian Socialist Party (PSI) and senator for life since 1970. He was a recipient of the Lenin Peace Prize in 1951. He w ...

and Giuseppe Romita

Giuseppe Romita (7 January 1887 – 15 March 1958) was an Italian socialist politician. In his life he served several times as a cabinet minister and member of the Parliament.

Early life and career

The son of Guglielmo Romita and Maria Gianneli, ...

(Italian Socialist Party

The Italian Socialist Party (, PSI) was a socialist and later social-democratic political party in Italy, whose history stretched for longer than a century, making it one of the longest-living parties of the country.

Founded in Genoa in 1892, ...

), Ivanoe Bonomi

Ivanoe Bonomi (18 October 1873 – 20 April 1951) was an Italian politician and journalist who served as Prime Minister of Italy from 1921 to 1922 and again from 1944 to 1945.

Background and earlier career

Ivanoe Bonomi was born in Mantua, I ...

and Meuccio Ruini

Meuccio Ruini (14 December 1877 – 6 March 1970) was an Italian jurist and socialist politician who served as the president of the Italian Senate and the minister of the colonies.

Biography

After graduating in law from the University of Bologna, ...

(Labour Democratic Party

The Labour Democratic Party ( it, Partito Democratico del Lavoro), previously known as Labour Democracy (), was a social-democratic and social-liberal political party in Italy, founded in 1943 as the heir of defunct Italian Reformist Socialist P ...

), and Alessandro Casati

Alessandro Casati (5 March 1881 – 4 June 1955) was an Italian academic, commentator and politician. He served as a senator between 1923 and 1924 and again between 1948 and 1953. He also held ministerial office, most recently as Ministe ...

(Italian Liberal Party

The Italian Liberal Party ( it, Partito Liberale Italiano, PLI) was a liberal and conservative political party in Italy.

The PLI, which is the heir of the liberal currents of both the Historical Right and the Historical Left, was a minor party ...

). They formed the first Committee of National Liberation (CLN), with Bonomi taking over its presidency.

The Italian Communist Party

The Italian Communist Party ( it, Partito Comunista Italiano, PCI) was a communist political party in Italy.

The PCI was founded as ''Communist Party of Italy'' on 21 January 1921 in Livorno by seceding from the Italian Socialist Party (PSI). ...

was anxious to take the initiative without waiting for the Allies:

The Allies did not believe in the guerillas' effectiveness, so General Alexander postponed their attacks against the Nazis. On 16 October, the CLN issued its first important political and operational press release, which rejected the calls for reconciliation launched by Republican leaders. CLN Milan asked "the Italian people to fight against the German invaders and against their fascist lackeys".

Luigi Longo

Luigi Longo (15 March 1900 – 16 October 1980), also known as Gallo, was an Italian communist politician and secretary of the Italian Communist Party from 1964 to 1972. He was also the first foreigner to be awarded an Order of Lenin.

Early l ...

, under the political direction of Pietro Secchia

Pietro Secchia (19 December 1903 – 7 July 1971) was an Italian politician, anti-fascist partisan leader and a prominent leader of the Italian Communist Party.

Biography

Early life

Secchia was born into a working-class family. His father wa ...

and Giancarlo Pajetta

Giancarlo Pajetta (24 June 1911 – 13 September 1990) was an Italian communist politician.

Biography

Pajetta was born in a working-class district of Turin to Carlo, a bank employee, and Elvira Berrini, an elementary schoolteacher. He attended ...

, Chief of Staff. The first operational order, dated 25 November, ordered the partisans to:

* attack and annihilate in every way officers, soldiers, and material deposits of Hitler's armed forces;

* attack and annihilate in every way people, places, and properties of fascists and traitors who collaborate with the occupying Germans;

* attack and annihilate in every way war industries, communication systems and everything that might help the war plans of the Nazi occupants.

Shortly after the Armistice, parts of the Italian Communist Party

The Italian Communist Party ( it, Partito Comunista Italiano, PCI) was a communist political party in Italy.

The PCI was founded as ''Communist Party of Italy'' on 21 January 1921 in Livorno by seceding from the Italian Socialist Party (PSI). ...

, the ''Gruppi di Azione Patriottica

The Patriotic Action Groups (GAP), formed by the general command of the Garibaldi Brigades at the end of October 1943, were small groups of partisans that were born on the initiative of the Italian Communist Party to operate mainly in the city, ...

'' ("Patriotic Action Groups") or simply ''GAP'', established small cells whose main purpose was to unleash urban terror through bomb attacks against fascists, Germans and their supporters. They operated independently in case of arrest or betrayal of individual elements. The success of these attacks led the German and Italian police to believe they were composed of foreign intelligence agents. A public announcement from the PCI in September 1943 stated:

The GAP's mission was claimed to be delivering "justice" to Nazi tyranny and terror, with emphasis on the selection of targets: "the official, hierarchical collaborators, agents hired to denounce men of the Resistance and Jews, the Nazi police informants and law enforcement organizations of CSR", thus differentiating it from the Nazi terror. However, partisan memoirs discussed the "elimination of enemies especially heinous", such as torturers, spies and provocateurs. Some orders from branch command partisans insisted on protecting the innocent, instead of providing lists of categories to be hit as individuals deserving of punishment. Part of the Italian press during the war agreed that murders were carried out against moderate Republican fascists willing to compromise and negotiate, such as Aldo Resega, Igino Ghisellini, Eugenio Facchini, and the philosopher Giovanni Gentile

Giovanni Gentile (; 30 May 1875 – 15 April 1944) was an Italian neo-Hegelian idealist philosopher, educator, and fascist politician. The self-styled "philosopher of Fascism", he was influential in providing an intellectual foundation for I ...

.

Women also participated in the resistance, mainly by procuring supplies, clothing and medicines, distributing anti-fascist propaganda, fundraising, maintaining communications, organizing partisan rallies, and participating in strikes and demonstrations against fascism. Some women actively participated in the conflict as combatants.

The first detachment of guerilla fighters rose up in Piedmont

it, Piemontese

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 ...

in mid-1944 as the Garibaldi Brigade ''Eusebio Giambone''. Partisan forces varied by seasons, German and fascist repression and also by Italian topography, never exceeding 200,000 people actively involved.

Fascist forces

When the Italian Resistance movement began, consisting of various Italian soldiers of disbanded units and many young people not willing to be conscripted into the fascist forces, Mussolini's

When the Italian Resistance movement began, consisting of various Italian soldiers of disbanded units and many young people not willing to be conscripted into the fascist forces, Mussolini's Italian Social Republic

The Italian Social Republic ( it, Repubblica Sociale Italiana, ; RSI), known as the National Republican State of Italy ( it, Stato Nazionale Repubblicano d'Italia, SNRI) prior to December 1943 but more popularly known as the Republic of Salò ...

(RSI) also began putting together an army. This was formed with what was left of the previous Regio Esercito and Regia Marina corps, fascist volunteers, and drafted personnel. At first it was organized into four regular divisions (''1ª Divisione Bersaglieri Italia'' – light infantry, ''2ª Divisione Granatieri Littorio'' – grenadiers, ''3ª Divisione fanteria di marina San Marco'' – marines, ''4ª Divisione Alpina Monterosa'' – mountain troops), together with various irregular formations and the fascist militia ''Guardia Nazionale Repubblicana'' (GNR) that in 1944 were brought under the control of the regular army.

The fascist republic fought against the partisans to keep control of the territory. The fascists claimed their armed forces numbered 780,000 men and women, but sources indicate that there were no more than 558,000. Partisans and their active supporters numbered 82,000 in June 1944.

In addition to regular units of the Republican Army and the Black Brigades, various special units of fascists were organized, at first spontaneously and afterward from regular units that were part of Salò's armed forces. These formations, often including criminals, adopted brutal methods during counterinsurgency

Counterinsurgency (COIN) is "the totality of actions aimed at defeating irregular forces". The Oxford English Dictionary defines counterinsurgency as any "military or political action taken against the activities of guerrillas or revolutionar ...

operations, repression and retaliation.

Among the first to form was the ''banda'' of the Federal Guido Bardi and William Pollastrini in Rome, whose methods shocked even the Germans. In Rome, the ''Banda Koch'' helped dismantle the clandestine structure of the Partito d'Azione

The Action Party ( it, Partito d'Azione, PdA) was a liberal-socialist political party in Italy. The party was anti-fascist and republican. Its prominent leaders were Carlo Rosselli, Ferruccio Parri, Emilio Lussu and Ugo La Malfa. Other prominen ...

. The ''Banda Koch,'' led by Pietro Koch

Pietro Koch (18 August 1918 – 4 June 1945) was an Italian soldier and leader of the Banda Koch, a group notorious for its anti-partisan activity in the Republic of Salò.

Biography

The son of an Imperial German Navy officer, Koch was born in B ...

, then under the protection of General Kurt Mälzer

Kurt Mälzer (2 August 1894 – 24 March 1952) was a German general of the ''Luftwaffe'' and a war criminal during World War II. In 1943, Mälzer was appointed the military commander of the city of Rome, subordinated to General Eberhard von Mack ...

, the German military commander for the Rome region, were known for their brutal treatment of anti-fascist partisans. After the fall of Rome, Koch moved to Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city h ...

. He gained the confidence of Interior Minister Guido Buffarini Guidi

Guido Buffarini Guidi (17 August 1895 – 10 July 1945) was an Italian army officer and politician, executed for war crimes in 1945.

Biography

Buffarini Guidi was born in Pisa in 1895. When Italy entered World War I, he volunteered in an ...

and continued his repressive activity in various Republican police forces. The ''Banda Carità'', a special unit constituted within the 92nd Legion Blackshirts

The Voluntary Militia for National Security ( it, Milizia Volontaria per la Sicurezza Nazionale, MVSN), commonly called the Blackshirts ( it, Camicie Nere, CCNN, singular: ) or (singular: ), was originally the paramilitary wing of the Natio ...

, operated in Tuscany

Tuscany ( ; it, Toscana ) is a Regions of Italy, region in central Italy with an area of about and a population of about 3.8 million inhabitants. The regional capital is Florence (''Firenze'').

Tuscany is known for its landscapes, history, art ...

and Veneto

Veneto (, ; vec, Vèneto ) or Venetia is one of the 20 regions of Italy. Its population is about five million, ranking fourth in Italy. The region's capital is Venice while the biggest city is Verona.

Veneto was part of the Roman Empire unt ...

. It became infamous for violent repression, such as the 1944 Piazza Tasso massacre The Piazza Tasso massacre (Italian: ''Eccidio in Piazza Tasso'') was a massacre that occurred on July 17, 1944, at Piazza Tasso in Florence, Tuscany, Italy.

History

On the above named date, Italian militias of the fascist Italian Social Republic ...

in Florence.

corporal

Corporal is a military rank in use in some form by many militaries and by some police forces or other uniformed organizations. The word is derived from the medieval Italian phrase ("head of a body"). The rank is usually the lowest ranking non ...

Francesco Colombo, already expelled from the PNF for embezzlement. Considering him dangerous to the public, in November 1943, the Federal (i.e., fascist provincial leader) Aldo Resega wanted to depose him, but was killed by a GAP attack. Colombo remained at his post despite complaints and inquiries. On 10 August 1944, Muti's ''Squadrists'', together with the GNR, perpetrated the Piazzale Loreto

is a major city square in Milan, Italy.

Origin

The name ''Loreto'' is also used in a wider sense to refer to the district surrounding the square, which is part of the Zone 2 administrative division, in the northeastern part of the city. The ...

massacre in Milan. The victims were fifteen anti-fascist rebels, killed in retaliation for an assault against a German truck. Following the massacre, the mayor

In many countries, a mayor is the highest-ranking official in a municipal government such as that of a city or a town. Worldwide, there is a wide variance in local laws and customs regarding the powers and responsibilities of a mayor as well a ...

and chief of the Province of Milan, Piero Parini, resigned in an attempt to strengthen the cohesion of moderate forces, who were undermined by the heavy German repression and various militias of Social Republic.

The command of the National Republican Army

The National Republican Army (Esercito Nazionale Repubblicano, or ENR) was the army of the Italian Social Republic ( it, Repubblica Sociale Italiana, or RSI) from 1943 to 1945 that fought on the side of Nazi Germany during World War II.

The EN ...

was in the hands of Marshall Graziani and his deputies Mischi and Montagna. They controlled the repression and coordinated anti-partisan actions of the regular troops, the GNR, the Black Brigades, and various semi-official police, together with the Germans, who made the reprisals. The Republican Army was augmented by the ''Graziani call-up'' which conscripted several thousand men. ''Graziani'' were only nominally involved in the armed forces, under the apolitical CSR.

The Republican Police Corps

The Republican Police Corps (Italian: ''Corpo di Polizia Repubblicana'') was a police force of the Italian Social Republic during the Italian Civil War.

History

The Republican Police Corps was established in December 1944 as part of the Itali ...

formed in 1944 under Lieutenant-General Renato Ricci

Renato Ricci (1 June 1896 – 22 January 1956) was an Italian fascist politician active during the government of Benito Mussolini.

Biography

Ricci was born on 1 June 1896 in Carrara into working-class family. He first came to prominence ...

. It included the Fascist Blackshirts, the Italian Africa Police

140px, Badge

The Italian African Police (Italian: ''Polizia dell'Africa Italiana'', or PAI), was the police force of Italian North Africa and Italian East Africa from 1 June 1936 to 1 December 1945.

Characteristics

Towards the end of the war i ...

members serving in Rome, and the Carabinieri

The Carabinieri (, also , ; formally ''Arma dei Carabinieri'', "Arm of Carabineers"; previously ''Corpo dei Carabinieri Reali'', "Royal Carabineers Corps") are the national gendarmerie of Italy who primarily carry out domestic and foreign polic ...

. The Corps worked against anti-fascist groups and was autonomous (it did not report to Rodolfo Graziani

Rodolfo Graziani, 1st Marquis of Neghelli (; 11 August 1882 – 11 January 1955), was a prominent Italian military officer in the Kingdom of Italy's '' Regio Esercito'' ("Royal Army"), primarily noted for his campaigns in Africa before and durin ...

), according to an order issued by Mussolini on 19 November 1944.

Civil war

Background

The fall of the Fascist regime in Italy

After the victory achieved in the North African campaign, the

After the victory achieved in the North African campaign, the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

started the Italian Campaign: between 11 and 12 June 1943, Lampedusa

Lampedusa ( , , ; scn, Lampidusa ; grc, Λοπαδοῦσσα and Λοπαδοῦσα and Λοπαδυῦσσα, Lopadoûssa; mt, Lampeduża) is the largest island of the Italian Pelagie Islands in the Mediterranean Sea.

The ''comune'' of L ...

and Pantelleria

Pantelleria (; Sicilian: ''Pantiddirìa'', Maltese: ''Pantellerija'' or ''Qawsra''), the ancient Cossyra or Cossura, is an Italian island and comune in the Strait of Sicily in the Mediterranean Sea, southwest of Sicily and east of the Tunis ...

were the first Italian territories to be conquered in Operation Corkscrew

Operation Corkscrew was the codename for the Allied invasion of the Italian island of Pantelleria (between Sicily and Tunisia) on 11 June 1943, prior to the Allied invasion of Sicily, during the Second World War. There had been an early plan to ...

. On 10 July, the landing in Sicily

Landing is the last part of a flight, where a flying animal, aircraft, or spacecraft returns to the ground. When the flying object returns to water, the process is called alighting, although it is commonly called "landing", "touchdown" or ...

began, and on 19 July, Rome was bombed for the first time.

The threat of the invasion of the national territory, the conviction of the inevitability of defeat, the inability of Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

to "detach himself from Germany", together with the awareness that his presence prevented any negotiations with the Allies, determined the fall of the his government: on the night between 24 and 25 July, the Grand Council of Fascism

The Grand Council of Fascism (, also translated "Fascist Grand Council") was the main body of Mussolini's Fascist government in Italy, that held and applied great power to control the institutions of government. It was created as a body of th ...

approved a motion of no confidence against the prime minister, called the Grandi agenda, named after its promoter Dino Grandi

Dino Grandi (4 June 1895 – 21 May 1988), 1st Conte di Mordano, was an Italian Fascist politician, minister of justice, minister of foreign affairs and president of parliament.

Early life

Born at Mordano, province of Bologna, Grandi was a gr ...

. The next day King Victor Emmanuel III

The name Victor or Viktor may refer to:

* Victor (name), including a list of people with the given name, mononym, or surname

Arts and entertainment

Film

* ''Victor'' (1951 film), a French drama film

* ''Victor'' (1993 film), a French shor ...

had Mussolini put under arrest and replaced him with Marshal Pietro Badoglio

Pietro Badoglio, 1st Duke of Addis Abeba, 1st Marquess of Sabotino (, ; 28 September 1871 – 1 November 1956), was an Italian general during both World Wars and the first viceroy of Italian East Africa. With the fall of the Fascist regime ...

.

Faced with the coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

, the fascists remained inert and the army was able to occupy both Wedekind and Braschi palaces, the headquarters of the party and of the Roman federation respectively, without encountering resistance. In the absence of orders from General Enzo Galbiati

Enzo Emilio Galbiati (23 May 1897 – 23 May 1982) was an Italian soldier and fascist politician.

Biography

Born in Monza, Galbiati was a lieutenant in the Royal Italian Army's elite Arditi during the First World War. He was wounded in action ...

(who had also voted against the dismissal of Mussolini), not even the Blackshirts

The Voluntary Militia for National Security ( it, Milizia Volontaria per la Sicurezza Nazionale, MVSN), commonly called the Blackshirts ( it, Camicie Nere, CCNN, singular: ) or (singular: ), was originally the paramilitary wing of the Natio ...

moved, although they could count on the 1st Armored Division "M", made up of elements loyal to the regime, which was located north of Lake Bracciano

Lake Bracciano ( it, Lago di Bracciano) is a lake of volcanic origin in the Italian region of Lazio, northwest of Rome. It is the second largest lake in the region (second only to Lake Bolsena) and one of the major lakes of Italy. It has a circu ...

.

The "45 days"

The news of Mussolini's resignation was considered by a part of the Italians, exhausted by the conflict, as proof of its imminent conclusion; there were manifestations of jubilation, but also of violence, with the destruction of goods and property of theNational Fascist Party

The National Fascist Party ( it, Partito Nazionale Fascista, PNF) was a political party in Italy, created by Benito Mussolini as the political expression of Italian Fascism and as a reorganization of the previous Italian Fasces of Combat. The ...

and party organizations and the removal and damage of symbols and monuments linked to fascism. However, the hopes of peace soon vanished, following the proclamation in which Badoglio announced: "The war continues. Italy ..keeps its word ". Thus began the period of "forty-five days", in which secret negotiations began to conclude a separate peace with the Allies, disguised by public declarations of loyalty to Germany. Meanwhile, the Germans, prepared for the eventuality of an Italian surrender, were planning Operation Achse

Operation Achse (german: Fall Achse, lit=Case Axis), originally called Operation Alaric (), was the codename for the German operation to forcibly disarm the Italian armed forces after Italy's armistice with the Allies on 3 September 1943.

S ...

to occupy Italy.

The Badoglio government began the work of dismantling the fascist state and took measures to maintain order in the country: it dissolved the PNF, maintained the prohibition of the establishment of political parties and imposed martial law. In addition, some

The Badoglio government began the work of dismantling the fascist state and took measures to maintain order in the country: it dissolved the PNF, maintained the prohibition of the establishment of political parties and imposed martial law. In addition, some anti-fascist

Anti-fascism is a political movement in opposition to fascist ideologies, groups and individuals. Beginning in European countries in the 1920s, it was at its most significant shortly before and during World War II, where the Axis powers were ...

demonstrations were bloodily repressed, such as those that took place on 28 July in Bari

Bari ( , ; nap, label= Barese, Bare ; lat, Barium) is the capital city of the Metropolitan City of Bari and of the Apulia region, on the Adriatic Sea, southern Italy. It is the second most important economic centre of mainland Southern Italy a ...

(massacre of via Nicolò dell'Arca) and Reggio Emilia

Reggio nell'Emilia ( egl, Rèz; la, Regium Lepidi), usually referred to as Reggio Emilia, or simply Reggio by its inhabitants, and known until 1861 as Reggio di Lombardia, is a city in northern Italy, in the Emilia-Romagna region. It has abou ...

(massacre of Reggiane), where the military fired at the demonstrators as set out in a circulated memo written by General Mario Roatta

Mario Roatta (2 February 1887 – 7 January 1968) was an Italian general. After serving in World War I he rose to command the Corpo Truppe Volontarie which assisted Francisco Franco's force during the Spanish Civil War. He was the Deputy Chief of ...

, chief of staff of the army, who ordered soldiers to face the riots "in combat formation" and to "open fire at a distance even with mortars and artillery without warning of any kind".

These provisions made it possible for the anti-fascists to spread the idea of a substantial continuity between the government of Mussolini and that of Badoglio, to the point of "asking oneself whether the liquidation of fascism is not by chance a tragic deception". This sentiment was also supported by the fact that many public officials of the fascist period in key posts had been left in their place by the new government, as remarked by the verse of ''La Badoglieide'': "You called the squadrists back / the anti-fascists you put them in jail / the shirt was no longer black / but fascism remained the master."

Subsequently, Badoglio managed to completely neutralize the militia, incorporating it into the army and replacing the senior cadres with officers of sure monarchical faith. Galbiati's successor in command of the corps, Quirino Armellini

Quirino Armellini (31 January 1889 in Legnaro – 13 January 1975 in Rome) was an Italian Officer (armed forces), military officer, who served as a General officer, general in both the Royal Italian Army and the Italian Army.

Biography

Arme ...

, issued a circulated memo on July 30 in which he guaranteed Badoglio the harmlessness of the black shirts, stigmatizing "the reaction of the country, unpleasant and often brutal towards the militia", and assuring the will of the new government to continue the war against the Anglo-Americans, described as an enemy "animated by inhuman hatred and by the determined resolve to annihilate" the homeland, to which it was necessary to "oppose our breasts and our weapons, strenuously fighting alongside the ally".

In the same days, the anti-fascists began to reorganize themselves thanks to the return from prison, confinement or exile of numerous leaders: Luigi Longo

Luigi Longo (15 March 1900 – 16 October 1980), also known as Gallo, was an Italian communist politician and secretary of the Italian Communist Party from 1964 to 1972. He was also the first foreigner to be awarded an Order of Lenin.

Early l ...

, Pietro Secchia

Pietro Secchia (19 December 1903 – 7 July 1971) was an Italian politician, anti-fascist partisan leader and a prominent leader of the Italian Communist Party.

Biography

Early life

Secchia was born into a working-class family. His father wa ...

and Mauro Scoccimarro

Mauro Scoccimarro (30 October 1895 – 2 January 1972) was an Italian economist and communist politician. He was one of the founders of the Italian Communist Party and the minister of finance between 1945 and 1947.

Early life and education

Scocc ...

for the communists

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a so ...

; Pietro Nenni

Pietro Sandro Nenni (; 9 February 1891 – 1 January 1980) was an Italian socialist politician, the national secretary of the Italian Socialist Party (PSI) and senator for life since 1970. He was a recipient of the Lenin Peace Prize in 1951. He w ...

, Sandro Pertini

Alessandro "Sandro" Pertini (; 25 September 1896 – 24 February 1990) was an Italian socialist politician who served as the president of Italy from 1978 to 1985.

Early life

Born in Stella (Province of Savona) as the son of a wealthy landown ...

, Rodolfo Morandi

Rodolfo Morandi (30 July 1902 – 26 July 1955) was an Italian socialist politician and economist. He was a member of the Socialist Party and was one of its leading figures following World War II. He served as the minister of industry and commerc ...

and Giuseppe Saragat

Giuseppe Saragat (; 19 September 1898 – 11 June 1988) was an Italian politician who served as the president of Italy from 1964 to 1971.

Early life

Born to Sardinian parents, he was a member of the Unitary Socialist Party (Italy, 1922), Unita ...

for the socialists

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the eco ...

; and Riccardo Bauer

Riccardo Bauer (1896–1982) was an Italian anti-fascist journalist and political figure. He was one of the early Italians who fought against Benito Mussolini's rule. Due to his activities Bauer was imprisoned for a long time and was freed only a ...

, Ugo La Malfa

Ugo La Malfa (16 May 1903 – 26 March 1979) was an Italian politician and an important leader of the Italian Republican Party (''Partito Repubblicano Italiano''; PRI).

Early years and anti-fascist resistance

La Malfa was born in Palermo, Sic ...

and Emilio Lussu