Ionosphere on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The ionosphere () is the

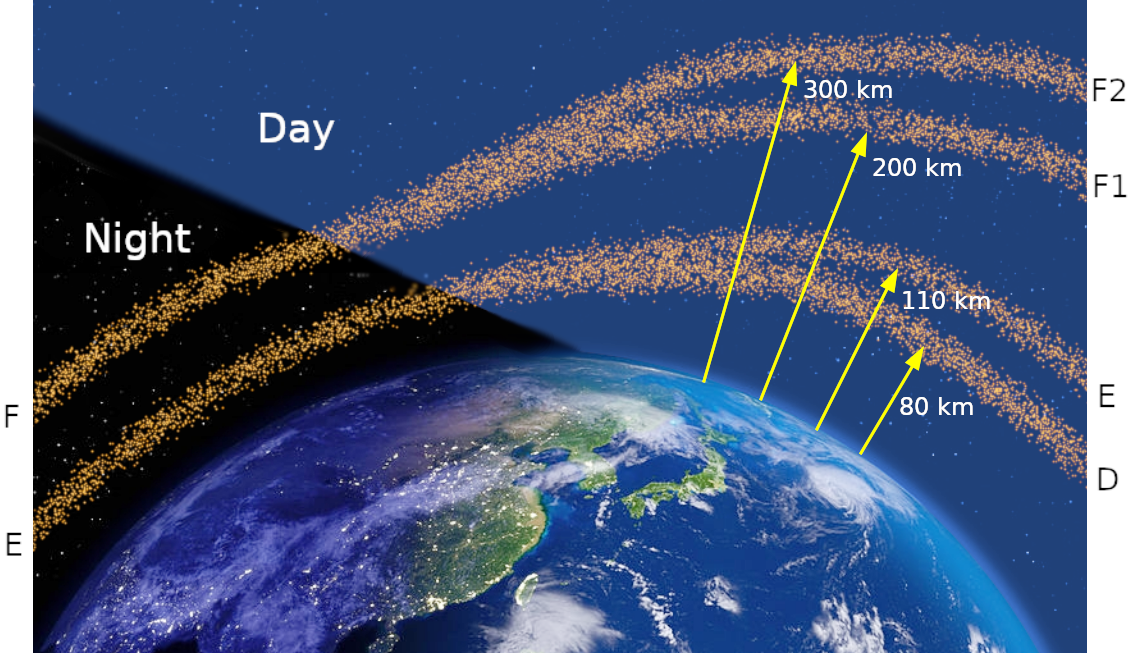

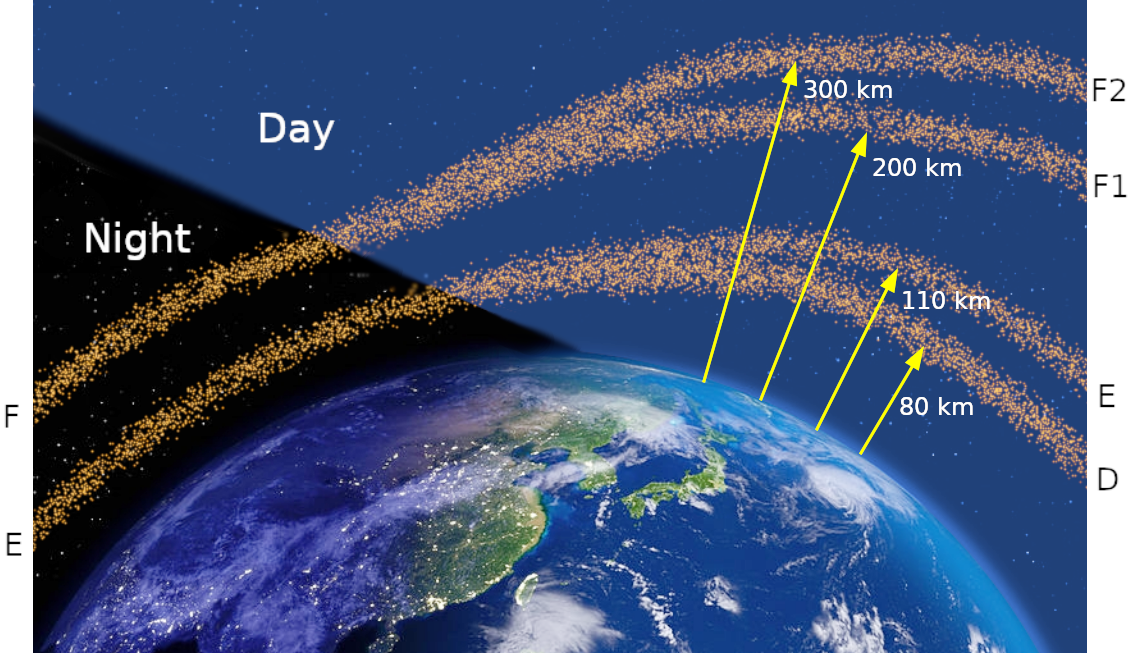

At night the F layer is the only layer of significant ionization present, while the ionization in the E and D layers is extremely low. During the day, the D and E layers become much more heavily ionized, as does the F layer, which develops an additional, weaker region of ionisation known as the F layer. The F layer persists by day and night and is the main region responsible for the refraction and reflection of radio waves.

At night the F layer is the only layer of significant ionization present, while the ionization in the E and D layers is extremely low. During the day, the D and E layers become much more heavily ionized, as does the F layer, which develops an additional, weaker region of ionisation known as the F layer. The F layer persists by day and night and is the main region responsible for the refraction and reflection of radio waves.

NASA/JPL: Titan's upper atmosphere

Accessed 2010-08-25 Ionospheres have also been observed at Io (moon), Io, Europa (moon), Europa, Ganymede (moon), Ganymede, and Triton (moon), Triton.

SWPC's Radio User's Page

'.

Amsat-Italia project on Ionospheric propagation (ESA SWENET website)

Layman Level Explanations Of "Seemingly" Mysterious 160 Meter (MF/HF) Propagation Occurrences

USGS Geomagnetism ProgramEncyclopædia Britannica, Ionosphere and magnetosphereCurrent Space Weather ConditionsSuper Dual Auroral Radar NetworkEuropean Incoherent Scatter radar system

{{Authority control Ionosphere, Radio frequency propagation

ionized

Ionization, or Ionisation is the process by which an atom or a molecule acquires a negative or positive charge by gaining or losing electrons, often in conjunction with other chemical changes. The resulting electrically charged atom or molecule ...

part of the upper atmosphere of Earth

The atmosphere of Earth is the layer of gases, known collectively as air, retained by Earth's gravity that surrounds the planet and forms its planetary atmosphere. The atmosphere of Earth protects life on Earth by creating pressure allowing fo ...

, from about to above sea level, a region that includes the thermosphere

The thermosphere is the layer in the Earth's atmosphere directly above the mesosphere and below the exosphere. Within this layer of the atmosphere, ultraviolet radiation causes photoionization/photodissociation of molecules, creating ions; the ...

and parts of the mesosphere and exosphere. The ionosphere is ionized by solar radiation

Solar irradiance is the power per unit area (surface power density) received from the Sun in the form of electromagnetic radiation in the wavelength range of the measuring instrument.

Solar irradiance is measured in watts per square metre ( ...

. It plays an important role in atmospheric electricity

Atmospheric electricity is the study of electrical charges in the Earth's atmosphere (or that of another planet). The movement of charge between the Earth's surface, the atmosphere, and the ionosphere is known as the global atmospheric electr ...

and forms the inner edge of the magnetosphere. It has practical importance because, among other functions, it influences radio propagation

Radio propagation is the behavior of radio waves as they travel, or are propagated, from one point to another in vacuum, or into various parts of the atmosphere.

As a form of electromagnetic radiation, like light waves, radio waves are affect ...

to distant places on Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's surfa ...

.

History of discovery

As early as 1839, the German mathematician and physicistCarl Friedrich Gauss

Johann Carl Friedrich Gauss (; german: Gauß ; la, Carolus Fridericus Gauss; 30 April 177723 February 1855) was a German mathematician and physicist who made significant contributions to many fields in mathematics and science. Sometimes refer ...

postulated that an electrically conducting region of the atmosphere could account for observed variations of Earth's magnetic field. Sixty years later, Guglielmo Marconi

Guglielmo Giovanni Maria Marconi, 1st Marquis of Marconi (; 25 April 187420 July 1937) was an Italians, Italian inventor and electrical engineering, electrical engineer, known for his creation of a practical radio wave-based Wireless telegrap ...

received the first trans-Atlantic radio signal on December 12, 1901, in St. John's, Newfoundland

St. John's is the capital and largest city of the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador, located on the eastern tip of the Avalon Peninsula on the island of Newfoundland.

The city spans and is the easternmost city in North America ...

(now in Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

) using a kite-supported antenna for reception. The transmitting station in Poldhu, Cornwall, used a spark-gap transmitter

A spark-gap transmitter is an obsolete type of radio transmitter which generates radio waves by means of an electric spark."Radio Transmitters, Early" in Spark-gap transmitters were the first type of radio transmitter, and were the main type us ...

to produce a signal with a frequency

Frequency is the number of occurrences of a repeating event per unit of time. It is also occasionally referred to as ''temporal frequency'' for clarity, and is distinct from ''angular frequency''. Frequency is measured in hertz (Hz) which is eq ...

of approximately 500 kHz

The hertz (symbol: Hz) is the unit of frequency in the International System of Units (SI), equivalent to one event (or cycle) per second. The hertz is an SI derived unit whose expression in terms of SI base units is s−1, meaning that on ...

and a power of 100 times more than any radio signal previously produced. The message received was three dits, the Morse code

Morse code is a method used in telecommunication to encode text characters as standardized sequences of two different signal durations, called ''dots'' and ''dashes'', or ''dits'' and ''dahs''. Morse code is named after Samuel Morse, one of ...

for the letter S. To reach Newfoundland the signal would have to bounce off the ionosphere twice. Dr. Jack Belrose John S. (Jack) Belrose (born 24 November 1926), is a Canadian radio scientist.

He was born in the small town of Warner, Alberta. He attended the University of Cambridge, where he was awarded a PhD in 1958. He has worked for the Defence Research Te ...

has contested this, however, based on theoretical and experimental work. However, Marconi did achieve transatlantic wireless communications in Glace Bay, Nova Scotia, one year later.

In 1902, Oliver Heaviside

Oliver Heaviside FRS (; 18 May 1850 – 3 February 1925) was an English self-taught mathematician and physicist who invented a new technique for solving differential equations (equivalent to the Laplace transform), independently developed ...

proposed the existence of the Kennelly–Heaviside layer of the ionosphere which bears his name. Heaviside's proposal included means by which radio signals are transmitted around the Earth's curvature. Also in 1902, Arthur Edwin Kennelly

Arthur Edwin Kennelly (December 17, 1861 – June 18, 1939) was an American electrical engineer.

Biography

Kennelly was born December 17, 1861, in Colaba, in Bombay Presidency, British India, and was educated at University College School in Lond ...

discovered some of the ionosphere's radio-electrical properties.

In 1912, the U.S. Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washin ...

imposed the Radio Act of 1912

The Radio Act of 1912, formally known as "An Act to Regulate Radio Communication" (), is a United States federal law which was the first legislation to require licenses for radio stations. It was enacted before the introduction of broadcasting to ...

on amateur radio operators

An amateur radio operator is someone who uses equipment at an amateur radio station to engage in two-way personal communications with other amateur operators on radio frequencies assigned to the amateur radio service. Amateur radio operators hav ...

, limiting their operations to frequencies above 1.5 MHz (wavelength 200 meters or smaller). The government thought those frequencies were useless. This led to the discovery of HF radio propagation via the ionosphere in 1923.

In 1926, Scottish physicist Robert Watson-Watt

Sir Robert Alexander Watson Watt (13 April 1892 – 5 December 1973) was a Scottish pioneer of radio direction finding and radar technology.

Watt began his career in radio physics with a job at the Met Office, where he began looking for accura ...

introduced the term ''ionosphere'' in a letter published only in 1969 in ''Nature

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physics, physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomenon, phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. ...

'':

In the early 1930s, test transmissions of Radio Luxembourg

Radio Luxembourg was a multilingual commercial broadcaster in Luxembourg. It is known in most non-English languages as RTL (for Radio Television Luxembourg).

The English-language service of Radio Luxembourg began in 1933 as one of the earlies ...

inadvertently provided evidence of the first radio modification of the ionosphere; HAARP

The High-frequency Active Auroral Research Program (HAARP) was initiated as an ionospheric research program jointly funded by the U.S. Air Force, the U.S. Navy, the University of Alaska Fairbanks, and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Ag ...

ran a series of experiments in 2017 using the eponymous Luxembourg Effect.

Edward V. Appleton was awarded a Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." Alfr ...

in 1947 for his confirmation in 1927 of the existence of the ionosphere. Lloyd Berkner

Lloyd Viel Berkner (February 1, 1905 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin – June 4, 1967 in Washington, D.C.) was an American physicist and engineer. He was one of the inventors of the measuring device that since has become standard at ionospheric stations ...

first measured the height and density of the ionosphere. This permitted the first complete theory of short-wave radio propagation. Maurice V. Wilkes

Sir Maurice Vincent Wilkes (26 June 1913 – 29 November 2010) was a British computer scientist who designed and helped build the Electronic Delay Storage Automatic Calculator (EDSAC), one of the earliest stored program computers, and who in ...

and J. A. Ratcliffe researched the topic of radio propagation of very long radio waves in the ionosphere. Vitaly Ginzburg

Vitaly Lazarevich Ginzburg, ForMemRS (russian: Вита́лий Ла́заревич Ги́нзбург, link=no; 4 October 1916 – 8 November 2009) was a Russian physicist who was honored with the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2003, together wit ...

has developed a theory of electromagnetic wave propagation in plasmas such as the ionosphere.

In 1962, the Canadian

Canadians (french: Canadiens) are people identified with the country of Canada. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Canadians, many (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of ...

satellite Alouette 1

''Alouette 1'' is a deactivated Canadian satellite that studied the ionosphere. Launched in 1962, it was Canada's first satellite, and the first satellite constructed by a country other than the Soviet Union or the United States. Canada w ...

was launched to study the ionosphere. Following its success were Alouette 2 in 1965 and the two ISIS

Isis (; ''Ēse''; ; Meroitic: ''Wos'' 'a''or ''Wusa''; Phoenician: 𐤀𐤎, romanized: ʾs) was a major goddess in ancient Egyptian religion whose worship spread throughout the Greco-Roman world. Isis was first mentioned in the Old Kin ...

satellites in 1969 and 1971, further AEROS-A and -B in 1972 and 1975, all for measuring the ionosphere.

On July 26, 1963 the first operational geosynchronous satellite Syncom 2 was launched. On board radio beacons on this satellite (and its successors) enabled – for the first time – the measurement of total electron content

Total electron content (TEC) is an important descriptive quantity for the ionosphere of the Earth. TEC is the total number of electrons integrated between two points, along a tube of one meter squared cross section, i.e., the electron columnar n ...

(TEC) variation along a radio beam from geostationary orbit to an earth receiver. (The rotation of the plane of polarization directly measures TEC along the path.) Australian geophysicist Elizabeth Essex-Cohen

Elizabeth Essex-Cohen (1940-2004) was an Australian physicist who worked in global positioning satellite physics and was amongst the first women in Australia to be awarded a PhD in physics.

Early life and education

Elizabeth Annette Essex-Coh ...

from 1969 onwards was using this technique to monitor the atmosphere above Australia and Antarctica.

Geophysics

The ionosphere is a shell ofelectron

The electron ( or ) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary electric charge. Electrons belong to the first generation of the lepton particle family,

and are generally thought to be elementary particles because they have no ...

s and electrically charged atom

Every atom is composed of a nucleus and one or more electrons bound to the nucleus. The nucleus is made of one or more protons and a number of neutrons. Only the most common variety of hydrogen has no neutrons.

Every solid, liquid, gas, ...

s and molecule

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms held together by attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions which satisfy this criterion. In quantum physics, organic chemistry, and bioch ...

s that surrounds the Earth, stretching from a height of about to more than . It exists primarily due to ultraviolet

Ultraviolet (UV) is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelength from 10 nm (with a corresponding frequency around 30 PHz) to 400 nm (750 THz), shorter than that of visible light, but longer than X-rays. UV radiation ...

radiation from the Sun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is a nearly perfect ball of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core. The Sun radiates this energy mainly as light, ultraviolet, and infrared radi ...

.

The lowest part of the Earth's atmosphere

The atmosphere of Earth is the layer of gases, known collectively as air, retained by Earth's gravity that surrounds the planet and forms its planetary atmosphere. The atmosphere of Earth protects life on Earth by creating pressure allowing fo ...

, the troposphere

The troposphere is the first and lowest layer of the atmosphere of the Earth, and contains 75% of the total mass of the planetary atmosphere, 99% of the total mass of water vapour and aerosols, and is where most weather phenomena occur. From ...

extends from the surface to about . Above that is the stratosphere, followed by the mesosphere. In the stratosphere incoming solar radiation creates the ozone layer. At heights of above , in the thermosphere

The thermosphere is the layer in the Earth's atmosphere directly above the mesosphere and below the exosphere. Within this layer of the atmosphere, ultraviolet radiation causes photoionization/photodissociation of molecules, creating ions; the ...

, the atmosphere is so thin that free electrons can exist for short periods of time before they are captured by a nearby positive ion

An ion () is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge.

The charge of an electron is considered to be negative by convention and this charge is equal and opposite to the charge of a proton, which is considered to be positive by conve ...

. The number of these free electrons is sufficient to affect radio propagation

Radio propagation is the behavior of radio waves as they travel, or are propagated, from one point to another in vacuum, or into various parts of the atmosphere.

As a form of electromagnetic radiation, like light waves, radio waves are affect ...

. This portion of the atmosphere is partially ''ionized'' and contains a plasma which is referred to as the ionosphere.

Ultraviolet

Ultraviolet (UV) is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelength from 10 nm (with a corresponding frequency around 30 PHz) to 400 nm (750 THz), shorter than that of visible light, but longer than X-rays. UV radiation ...

(UV), X-ray

An X-ray, or, much less commonly, X-radiation, is a penetrating form of high-energy electromagnetic radiation. Most X-rays have a wavelength ranging from 10 picometers to 10 nanometers, corresponding to frequencies in the range 30&nb ...

and shorter wavelength

In physics, the wavelength is the spatial period of a periodic wave—the distance over which the wave's shape repeats.

It is the distance between consecutive corresponding points of the same phase on the wave, such as two adjacent crests, t ...

s of solar radiation

Solar irradiance is the power per unit area (surface power density) received from the Sun in the form of electromagnetic radiation in the wavelength range of the measuring instrument.

Solar irradiance is measured in watts per square metre ( ...

are ''ionizing,'' since photon

A photon () is an elementary particle that is a quantum of the electromagnetic field, including electromagnetic radiation such as light and radio waves, and the force carrier for the electromagnetic force. Photons are massless, so they a ...

s at these frequencies contain sufficient energy to dislodge an electron from a neutral gas atom or molecule upon absorption. In this process the light electron obtains a high velocity so that the temperature

Temperature is a physical quantity that expresses quantitatively the perceptions of hotness and coldness. Temperature is measurement, measured with a thermometer.

Thermometers are calibrated in various Conversion of units of temperature, temp ...

of the created electronic gas is much higher (of the order of thousand K) than the one of ions and neutrals. The reverse process to ionization

Ionization, or Ionisation is the process by which an atom or a molecule acquires a negative or positive charge by gaining or losing electrons, often in conjunction with other chemical changes. The resulting electrically charged atom or molecul ...

is recombination, in which a free electron is "captured" by a positive ion. Recombination occurs spontaneously, and causes the emission of a photon carrying away the energy produced upon recombination. As gas density increases at lower altitudes, the recombination process prevails, since the gas molecules and ions are closer together. The balance between these two processes determines the quantity of ionization present.

Ionization depends primarily on the Sun and its Extreme Ultraviolet (EUV) and X-ray irradiance which varies strongly with solar activity

Solar phenomena are natural phenomena which occur within the atmosphere of the Sun. These phenomena take many forms, including solar wind, radio wave flux, solar flares, coronal mass ejections, coronal heating and sunspots.

These phenomena are ...

. The more magnetically active the Sun is, the more sunspot active regions there are on the Sun at any one time. Sunspot active regions are the source of increased coronal heating

A corona ( coronas or coronae) is the outermost layer of a star's atmosphere. It consists of plasma.

The Sun's corona lies above the chromosphere and extends millions of kilometres into outer space. It is most easily seen during a total solar ...

and accompanying increases in EUV and X-ray irradiance, particularly during episodic magnetic eruptions that include solar flares that increase ionization on the sunlit side of the Earth and solar energetic particle

Solar energetic particles (SEP), formerly known as solar cosmic rays, are Particle physics, high-energy, charged particles originating in the solar atmosphere and solar wind. They consist of protons, electrons and heavy ions with energies rangin ...

events that can increase ionization in the polar regions. Thus the degree of ionization in the ionosphere follows both a diurnal (time of day) cycle and the 11-year solar cycle

The solar cycle, also known as the solar magnetic activity cycle, sunspot cycle, or Schwabe cycle, is a nearly periodic 11-year change in the Sun's activity measured in terms of variations in the number of observed sunspots on the Sun's surfa ...

. There is also a seasonal dependence in ionization degree since the local winter hemisphere

Hemisphere refers to:

* A half of a sphere

As half of the Earth

* A hemisphere of Earth

** Northern Hemisphere

** Southern Hemisphere

** Eastern Hemisphere

** Western Hemisphere

** Land and water hemispheres

* A half of the (geocentric) celes ...

is tipped away from the Sun, thus there is less received solar radiation. Radiation received also varies with geographical location (polar, auroral

An aurora (plural: auroras or aurorae), also commonly known as the polar lights, is a natural light display in Earth's sky, predominantly seen in high-latitude regions (around the Arctic and Antarctic). Auroras display dynamic patterns of br ...

zones, mid-latitudes

The middle latitudes (also called the mid-latitudes, sometimes midlatitudes, or moderate latitudes) are a spatial region on Earth located between the Tropic of Cancer (latitudes 23°26'22") to the Arctic Circle (66°33'39"), and Tropic of Caprico ...

, and equatorial regions). There are also mechanisms that disturb the ionosphere and decrease the ionization.

Sydney Chapman proposed that the region below the ionosphere be called ''neutrosphere''

(the ''neutral atmosphere'').

Layers of ionization

D layer

The D layer is the innermost layer, to above the surface of the Earth. Ionization here is due toLyman series In physics and chemistry, the Lyman series is a hydrogen spectral series of transitions and resulting ultraviolet emission lines of the hydrogen atom as an electron goes from ''n'' ≥ 2 to ''n'' = 1 (where ''n'' is the princip ...

-alpha hydrogen radiation at a wavelength

In physics, the wavelength is the spatial period of a periodic wave—the distance over which the wave's shape repeats.

It is the distance between consecutive corresponding points of the same phase on the wave, such as two adjacent crests, t ...

of 121.6 nanometre (nm) ionizing nitric oxide (NO). In addition, solar flares can generate hard X-rays (wavelength ) that ionize N and O. Recombination rates are high in the D layer, so there are many more neutral air molecules than ions.

Medium frequency (MF) and lower high frequency (HF) radio waves are significantly attenuated within the D layer, as the passing radio waves cause electrons to move, which then collide with the neutral molecules, giving up their energy. Lower frequencies experience greater absorption because they move the electrons farther, leading to greater chance of collisions. This is the main reason for absorption of HF radio waves, particularly at 10 MHz and below, with progressively less absorption at higher frequencies. This effect peaks around noon and is reduced at night due to a decrease in the D layer's thickness; only a small part remains due to cosmic rays

Cosmic rays are high-energy particles or clusters of particles (primarily represented by protons or atomic nuclei) that move through space at nearly the speed of light. They originate from the Sun, from outside of the Solar System in our ow ...

. A common example of the D layer in action is the disappearance of distant AM broadcast band

A broadcast band is a segment of the radio spectrum used for broadcasting.

See also

* North American broadcast television frequencies

* AM broadcasting

* FM broadcasting

* Dead air

* Internet radio

* Radio network

* Music radio

* Old-time r ...

stations in the daytime.

During solar proton event

In solar physics, a solar particle event (SPE), also known as a solar energetic particle (SEP) event or solar radiation storm, is a solar phenomenon which occurs when particles emitted by the Sun, mostly protons, become accelerated either in th ...

s, ionization can reach unusually high levels in the D-region over high and polar latitudes. Such very rare events are known as Polar Cap Absorption (or PCA) events, because the increased ionization significantly enhances the absorption of radio signals passing through the region. In fact, absorption levels can increase by many tens of dB during intense events, which is enough to absorb most (if not all) transpolar HF radio signal transmissions. Such events typically last less than 24 to 48 hours.

E layer

TheE layer

E, or e, is the fifth Letter (alphabet), letter and the second vowel#Written vowels, vowel letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the English alphabet, modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worl ...

is the middle layer, to above the surface of the Earth. Ionization is due to soft X-ray (1–10 nm) and far ultraviolet (UV) solar radiation ionization of molecular oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements as wel ...

(O). Normally, at oblique incidence, this layer can only reflect radio waves having frequencies lower than about 10 MHz and may contribute a bit to absorption on frequencies above. However, during intense sporadic E

Sporadic E (usually abbreviated E) is an unusual form of radio propagation using a low level of the Earth's ionosphere that normally does not refract radio waves.

Sporadic E propagation reflects signals off relatively small "clouds" in ...

events, the E layer can reflect frequencies up to 50 MHz and higher. The vertical structure of the E layer is primarily determined by the competing effects of ionization and recombination. At night the E layer weakens because the primary source of ionization is no longer present. After sunset an increase in the height of the E layer maximum increases the range to which radio waves can travel by reflection from the layer.

This region is also known as the Kennelly–Heaviside layer or simply the Heaviside layer. Its existence was predicted in 1902 independently and almost simultaneously by the American electrical engineer Arthur Edwin Kennelly

Arthur Edwin Kennelly (December 17, 1861 – June 18, 1939) was an American electrical engineer.

Biography

Kennelly was born December 17, 1861, in Colaba, in Bombay Presidency, British India, and was educated at University College School in Lond ...

(1861–1939) and the British physicist Oliver Heaviside

Oliver Heaviside FRS (; 18 May 1850 – 3 February 1925) was an English self-taught mathematician and physicist who invented a new technique for solving differential equations (equivalent to the Laplace transform), independently developed ...

(1850–1925). In 1924 its existence was detected by Edward V. Appleton and Miles Barnett

Miles Aylmer Fulton Barnett (30 April 1901 – 27 March 1979) was a New Zealand physicist and meteorologist. Born in Dunedin, New Zealand, he studied in that country but obtained his PhD in the United Kingdom at the University of Cambridge. He ...

.

E layer

The E layer ( sporadic E-layer) is characterized by small, thin clouds of intense ionization, which can support reflection of radio waves, frequently up to 50 MHz and rarely up to 450 MHz. Sporadic-E events may last for just a few minutes to many hours.Sporadic E propagation

Sporadic E (usually abbreviated E) is an unusual form of radio propagation using a low level of the Earth's ionosphere that normally does not refract radio waves.

Sporadic E propagation reflects signals off relatively small "clouds" in ...

makes VHF-operating by radio amateurs

An amateur radio operator is someone who uses equipment at an amateur radio station to engage in two-way communication, two-way personal communications with other amateur operators on Frequency, radio frequencies Amateur radio frequency allocatio ...

very exciting when long distance propagation paths that are generally unreachable "open up" to two-way communication. There are multiple causes of sporadic-E that are still being pursued by researchers. This propagation occurs every day during June and July in northern hemisphere mid-latitudes when high signal levels are often reached. The skip distances are generally around . Distances for one hop propagation can be anywhere from to . Multi-hop propagation over is also common, sometimes to distances of or more.

F layer

TheF layer

The F region of the ionosphere is home to the F layer of ionization, also called the Appleton–Barnett layer, after the English physicist Edward Appleton and New Zealand physicist and meteorologist Miles Barnett. As with other ionospheric secto ...

or region, also known as the Appleton–Barnett layer, extends from about to more than above the surface of Earth. It is the layer with the highest electron density, which implies signals penetrating this layer will escape into space. Electron production is dominated by extreme ultraviolet

Extreme ultraviolet radiation (EUV or XUV) or high-energy ultraviolet radiation is electromagnetic radiation in the part of the electromagnetic spectrum spanning wavelengths from 124 nm down to 10 nm, and therefore (by the Planck–E ...

(UV, 10–100 nm) radiation ionizing atomic oxygen. The F layer consists of one layer (F) at night, but during the day, a secondary peak (labelled F) often forms in the electron density profile. Because the F layer remains by day and night, it is responsible for most skywave propagation of radio

Radio is the technology of signaling and communicating using radio waves. Radio waves are electromagnetic waves of frequency between 30 hertz (Hz) and 300 gigahertz (GHz). They are generated by an electronic device called a transmit ...

waves and long distance high frequency (HF, or shortwave) radio communications.

Above the F layer, the number of oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements as wel ...

ions decreases and lighter ions such as hydrogen and helium become dominant. This region above the F layer peak and below the plasmasphere

The plasmasphere, or inner magnetosphere, is a region of the Earth's magnetosphere consisting of low-energy (cool) plasma. It is located above the ionosphere. The outer boundary of the plasmasphere is known as the plasmapause, which is defined ...

is called the topside ionosphere.

From 1972 to 1975 NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil space program, aeronautics research, and space research.

NASA was established in 1958, succeeding t ...

launched the AEROS and AEROS B satellites to study the F region. p. 12 AEROS

Ionospheric model

An ionospheric model is a mathematical description of the ionosphere as a function of location, altitude, day of year, phase of the sunspot cycle and geomagnetic activity. Geophysically, the state of the ionospheric plasma may be described by four parameters: ''electron density, electron and iontemperature

Temperature is a physical quantity that expresses quantitatively the perceptions of hotness and coldness. Temperature is measurement, measured with a thermometer.

Thermometers are calibrated in various Conversion of units of temperature, temp ...

'' and, since several species of ions are present, ''ionic composition''. Radio propagation

Radio propagation is the behavior of radio waves as they travel, or are propagated, from one point to another in vacuum, or into various parts of the atmosphere.

As a form of electromagnetic radiation, like light waves, radio waves are affect ...

depends uniquely on electron density.

Models are usually expressed as computer programs. The model may be based on basic physics of the interactions of the ions and electrons with the neutral atmosphere and sunlight, or it may be a statistical description based on a large number of observations or a combination of physics and observations. One of the most widely used models is the International Reference Ionosphere

International Reference Ionosphere (IRI) is a common permanent scientific project of the Committee on Space Research (COSPAR) and the International Union of Radio Science (URSI) started 1968/69. It is the international standard empirical model f ...

(IRI), which is based on data and specifies the four parameters just mentioned. The IRI is an international project sponsored by the Committee on Space Research

The Committee on Space Research (COSPAR) was established on October 3, 1958 by the International Council for Scientific Unions (ICSU). Among COSPAR's objectives are the promotion of scientific research in space on an international level, wi ...

(COSPAR) and the International Union of Radio Science

The International Union of Radio Science (abbreviated ''URSI'', after its French name, french: link=no, Union radio-scientifique internationale) is one of 26 international scientific unions affiliated to the International Council for Science ( ...

(URSI). The major data sources are the worldwide network of ionosonde

An ionosonde, or chirpsounder, is a special radar for the examination of the ionosphere. The basic ionosonde technology was invented in 1925 by Gregory Breit and Merle A. Tuve and further developed in the late 1920s by a number of prominent phys ...

s, the powerful incoherent scatter Incoherent scattering is a type of scattering phenomenon in physics. The term is most commonly used when referring to the scattering of an electromagnetic wave (usually light or radio frequency) by random fluctuations in a gas of particles (most o ...

radars (Jicamarca, Arecibo

Arecibo (; ) is a city and municipality on the northern coast of Puerto Rico, on the shores of the Atlantic Ocean, located north of Utuado and Ciales; east of Hatillo; and west of Barceloneta and Florida. It is about west of San Juan, th ...

, Millstone Hill, Malvern, St Santin), the ISIS and Alouette topside sounders, and in situ instruments on several satellites and rockets. IRI is updated yearly. IRI is more accurate in describing the variation of the electron density from bottom of the ionosphere to the altitude of maximum density than in describing the total electron content

Total electron content (TEC) is an important descriptive quantity for the ionosphere of the Earth. TEC is the total number of electrons integrated between two points, along a tube of one meter squared cross section, i.e., the electron columnar n ...

(TEC). Since 1999 this model is "International Standard" for the terrestrial ionosphere (standard TS16457).

Persistent anomalies to the idealized model

Ionogram

An ionosonde, or chirpsounder, is a special radar for the examination of the ionosphere. The basic ionosonde technology was invented in 1925 by Gregory Breit and Merle A. Tuve and further developed in the late 1920s by a number of prominent phys ...

s allow deducing, via computation, the true shape of the different layers. Nonhomogeneous structure of the electron

The electron ( or ) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary electric charge. Electrons belong to the first generation of the lepton particle family,

and are generally thought to be elementary particles because they have no ...

/ion

An ion () is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge.

The charge of an electron is considered to be negative by convention and this charge is equal and opposite to the charge of a proton, which is considered to be positive by conve ...

- plasma produces rough echo traces, seen predominantly at night and at higher latitudes, and during disturbed conditions.

Winter anomaly

At mid-latitudes, the F2 layer daytime ion production is higher in the summer, as expected, since the Sun shines more directly on the Earth. However, there are seasonal changes in the molecular-to-atomic ratio of the neutral atmosphere that cause the summer ion loss rate to be even higher. The result is that the increase in the summertime loss overwhelms the increase in summertime production, and total F2 ionization is actually lower in the local summer months. This effect is known as the winter anomaly. The anomaly is always present in the northern hemisphere, but is usually absent in the southern hemisphere during periods of low solar activity.Equatorial anomaly

Within approximately ± 20 degrees of the ''magnetic equator'', is the '' equatorial anomaly''. It is the occurrence of a trough in the ionization in the F2 layer at the equator and crests at about 17 degrees in magnetic latitude. TheEarth's magnetic field

Earth's magnetic field, also known as the geomagnetic field, is the magnetic field that extends from Earth's interior out into space, where it interacts with the solar wind, a stream of charged particles emanating from the Sun. The magnetic f ...

lines are horizontal at the magnetic equator. Solar heating and Tide, tidal oscillations in the lower ionosphere move plasma up and across the magnetic field lines. This sets up a sheet of electric current in the E region which, with the Horizontal plane, horizontal magnetic field, forces ionization up into the F layer, concentrating at ± 20 degrees from the magnetic equator. This phenomenon is known as the ''equatorial fountain''.

Equatorial electrojet

The worldwide solar-driven wind results in the so-called Sq (solar quiet) current system in the E region of the Earth's ionosphere (ionospheric dynamo region) ( altitude). Resulting from this current is an electrostatic field directed west–east (dawn–dusk) in the equatorial day side of the ionosphere. At the magnetic dip equator, where the geomagnetic field is horizontal, this electric field results in an enhanced eastward current flow within ± 3 degrees of the magnetic equator, known as the equatorial electrojet.Ephemeral ionospheric perturbations

X-rays: sudden ionospheric disturbances (SID)

When the Sun is active, strong solar flares can occur that hit the sunlit side of Earth with hard X-rays. The X-rays penetrate to the D-region, releasing electrons that rapidly increase absorption, causing a high frequency (3–30 MHz) radio blackout that can persist for many hours after strong flares. During this time very low frequency (3–30 kHz) signals will be reflected by the D layer instead of the E layer, where the increased atmospheric density will usually increase the absorption of the wave and thus dampen it. As soon as the X-rays end, the sudden ionospheric disturbance (SID) or radio black-out steadily declines as the electrons in the D-region recombine rapidly and propagation gradually returns to pre-flare conditions over minutes to hours depending on the solar flare strength and frequency.Protons: polar cap absorption (PCA)

Associated with solar flares is a release of high-energy protons. These particles can hit the Earth within 15 minutes to 2 hours of the solar flare. The protons spiral around and down the magnetic field lines of the Earth and penetrate into the atmosphere near the magnetic poles increasing the ionization of the D and E layers. PCA's typically last anywhere from about an hour to several days, with an average of around 24 to 36 hours. Coronal mass ejections can also release energetic protons that enhance D-region absorption in the polar regions.Geomagnetic storms

A geomagnetic storm is a temporary—sometimes intense—disturbance of the Earth's magnetosphere. * During a geomagnetic storm the F₂ layer will become unstable, fragment, and may even disappear completely. * In the Northern and Southern polar regions of the Earth polar aurora, aurorae will be observable in the night sky.Lightning

Lightning can cause ionospheric perturbations in the D-region in one of two ways. The first is through VLF (very low frequency) radio waves launched into the magnetosphere. These so-called "whistler" mode waves can interact with radiation belt particles and cause them to precipitate onto the ionosphere, adding ionization to the D-region. These disturbances are called "lightning-induced electron precipitation" (LEP) events. Additional ionization can also occur from direct heating/ionization as a result of huge motions of charge in lightning strikes. These events are called early/fast. In 1925, C. T. R. Wilson proposed a mechanism by which electrical discharge from lightning storms could propagate upwards from clouds to the ionosphere. Around the same time, Robert Watson-Watt, working at the Radio Research Station in Slough, UK, suggested that the ionospheric sporadic E layer (Es) appeared to be enhanced as a result of lightning but that more work was needed. In 2005, C. Davis and C. Johnson, working at the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory in Oxfordshire, UK, demonstrated that the Es layer was indeed enhanced as a result of lightning activity. Their subsequent research has focused on the mechanism by which this process can occur.Applications

Radio communication

Due to the ability of ionized atmospheric gases to refract high frequency (HF, or shortwave) radio waves, the ionosphere can reflect radio waves directed into the sky back toward the Earth. Radio waves directed at an angle into the sky can return to Earth beyond the horizon. This technique, called "skip" or " skywave" propagation, has been used since the 1920s to communicate at international or intercontinental distances. The returning radio waves can reflect off the Earth's surface into the sky again, allowing greater ranges to be achieved with multiple Hop (telecommunications), hops. This communication method is variable and unreliable, with reception over a given path depending on time of day or night, the seasons, weather, and the 11-year sunspot cycle. During the first half of the 20th century it was widely used for transoceanic telephone and telegraph service, and business and diplomatic communication. Due to its relative unreliability, shortwave radio communication has been mostly abandoned by the telecommunications industry, though it remains important for high-latitude communication where satellite-based radio communication is not possible. Shortwave broadcasting is useful in crossing international boundaries and covering large areas at low cost. Automated services still use shortwave radio frequencies, as do radio amateur hobbyists for private recreational contacts and to assist with emergency communications during natural disasters. Armed forces use shortwave so as to be independent of vulnerable infrastructure, including satellites, and the low latency of shortwave communications make it attractive to stock traders, where milliseconds count.Mechanism of refraction

When a radio wave reaches the ionosphere, the electric field in the wave forces the electrons in the ionosphere into oscillation at the same frequency as the radio wave. Some of the radio-frequency energy is given up to this resonant oscillation. The oscillating electrons will then either be lost to recombination or will re-radiate the original wave energy. Total refraction can occur when the collision frequency of the ionosphere is less than the radio frequency, and if the electron density in the ionosphere is great enough. A qualitative understanding of how an electromagnetic wave propagates through the ionosphere can be obtained by recalling geometric optics. Since the ionosphere is a plasma, it can be shown that the refractive index is less than unity. Hence, the electromagnetic "ray" is bent away from the normal rather than toward the normal as would be indicated when the refractive index is greater than unity. It can also be shown that the refractive index of a plasma, and hence the ionosphere, is frequency-dependent, see Dispersion (optics). The critical frequency is the limiting frequency at or below which a radio wave is reflected by an ionospheric layer at vertical angle of incidence (optics), incidence. If the transmitted frequency is higher than the plasma frequency of the ionosphere, then the electrons cannot respond fast enough, and they are not able to re-radiate the signal. It is calculated as shown below: : where N = electron density per m3 and fcritical is in Hz. The Maximum Usable Frequency (MUF) is defined as the upper frequency limit that can be used for transmission between two points at a specified time. : where = angle of arrival, the angle of the wave relative to the horizon, and sin is the sine function. The cutoff frequency is the frequency below which a radio wave fails to penetrate a layer of the ionosphere at the incidence angle required for transmission between two specified points by refraction from the layer.GPS/GNSS ionospheric correction

There are a number of models used to understand the effects of the ionosphere global navigation satellite systems. The Klobuchar model is currently used to compensate for ionospheric effects in GPS. This model was developed at the US Air Force Geophysical Research Laboratory circa 1974 by John (Jack) Klobuchar. The Galileo (satellite navigation), Galileo navigation system uses the NeQuick model.Other applications

The open system (systems theory), open system electrodynamic tether, which uses the ionosphere, is being researched. The space tether uses plasma contactors and the ionosphere as parts of a circuit to extract energy from the Earth's magnetic field by electromagnetic induction.Measurements

Overview

Scientists explore the structure of the ionosphere by a wide variety of methods. They include: * passive observations of optical and radio emissions generated in the ionosphere * bouncing radio waves of different frequencies from it *incoherent scatter Incoherent scattering is a type of scattering phenomenon in physics. The term is most commonly used when referring to the scattering of an electromagnetic wave (usually light or radio frequency) by random fluctuations in a gas of particles (most o ...

radars such as the EISCAT, Sondre Stromfjord, Millstone Hill Observatory, Millstone Hill, Arecibo

Arecibo (; ) is a city and municipality on the northern coast of Puerto Rico, on the shores of the Atlantic Ocean, located north of Utuado and Ciales; east of Hatillo; and west of Barceloneta and Florida. It is about west of San Juan, th ...

, Advanced Modular Incoherent Scatter Radar (AMISR) and Jicamarca Radio Observatory, Jicamarca radars

* coherent scatter radars such as the Super Dual Auroral Radar Network, Super Dual Auroral Radar Network (SuperDARN) radars

* special receivers to detect how the reflected waves have changed from the transmitted waves.

A variety of experiments, such as HAARP (High Frequency Active Auroral Research Program), involve high power radio transmitters to modify the properties of the ionosphere. These investigations focus on studying the properties and behavior of ionospheric plasma, with particular emphasis on being able to understand and use it to enhance communications and surveillance systems for both civilian and military purposes. HAARP was started in 1993 as a proposed twenty-year experiment, and is currently active near Gakona, Alaska.

The SuperDARN radar project researches the high- and mid-latitudes using coherent backscatter of radio waves in the 8 to 20 MHz range. Coherent backscatter is similar to Bragg scattering in crystals and involves the constructive interference of scattering from ionospheric density irregularities. The project involves more than 11 countries and multiple radars in both hemispheres.

Scientists are also examining the ionosphere by the changes to radio waves, from satellites and stars, passing through it. The Arecibo Telescope located in Puerto Rico, was originally intended to study Earth's ionosphere.

Ionograms

Ionograms show the virtual heights and critical frequencies of the ionospheric layers and which are measured by anionosonde

An ionosonde, or chirpsounder, is a special radar for the examination of the ionosphere. The basic ionosonde technology was invented in 1925 by Gregory Breit and Merle A. Tuve and further developed in the late 1920s by a number of prominent phys ...

. An ionosonde sweeps a range of frequencies, usually from 0.1 to 30 MHz, transmitting at vertical incidence to the ionosphere. As the frequency increases, each wave is refracted less by the ionization in the layer, and so each penetrates further before it is reflected. Eventually, a frequency is reached that enables the wave to penetrate the layer without being reflected. For ordinary mode waves, this occurs when the transmitted frequency just exceeds the peak plasma, or critical, frequency of the layer. Tracings of the reflected high frequency radio pulses are known as ionograms. Reduction rules are given in: "URSI Handbook of Ionogram Interpretation and Reduction", edited by William Roy Piggott and Karl Rawer, Elsevier Amsterdam, 1961 (translations into Chinese, French, Japanese and Russian are available).

Incoherent scatter radars

Incoherent scatter radars operate above the critical frequencies. Therefore, the technique allows probing the ionosphere, unlike ionosondes, also above the electron density peaks. The thermal fluctuations of the electron density scattering the transmitted signals lack Coherence (physics), coherence, which gave the technique its name. Their power spectrum contains information not only on the density, but also on the ion and electron temperatures, ion masses and drift velocities.GNSS radio occultation

Radio occultation is a remote sensing technique where a GNSS signal tangentially scrapes the Earth, passing through the atmosphere, and is received by a Low Earth Orbit (LEO) satellite. As the signal passes through the atmosphere, it is refracted, curved and delayed. An LEO satellite samples the total electron content and bending angle of many such signal paths as it watches the GNSS satellite rise or set behind the Earth. Using an Inverse Abel transform, Abel's transform, a radial profile of refractivity at that tangent point on earth can be reconstructed. Major GNSS radio occultation missions include the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment, GRACE, CHAMP (satellite), CHAMP, and Constellation Observing System for Meteorology, Ionosphere, and Climate, COSMIC.Indices of the ionosphere

In empirical models of the ionosphere such as Nequick, the following indices are used as indirect indicators of the state of the ionosphere.Solar intensity

F10.7 and R12 are two indices commonly used in ionospheric modelling. Both are valuable for their long historical records covering multiple solar cycles. F10.7 is a measurement of the intensity of solar radio emissions at a frequency of 2800 MHz made using a ground radio telescope. R12 is a 12 months average of daily sunspot numbers. The two indices have been shown to be correlated with each other. However, both indices are only indirect indicators of solar ultraviolet and X-ray emissions, which are primarily responsible for causing ionization in the Earth's upper atmosphere. We now have data from the GOES spacecraft that measures the background X-ray flux from the Sun, a parameter more closely related to the ionization levels in the ionosphere.Geomagnetic disturbances

* The ''A-index, A''- and ''K-index, K''-indices are a measurement of the behavior of the horizontal component of the geomagnetic field. The ''K''-index uses a semi-logarithmic scale from 0 to 9 to measure the strength of the horizontal component of the geomagnetic field. The Boulder ''K''-index is measured at the Boulder Geomagnetic Observatory. * The geomagnetic activity levels of the Earth are measured by the fluctuation of the Earth's magnetic field in SI units called tesla (unit), teslas (or in non-SI gauss (unit), gauss, especially in older literature). The Earth's magnetic field is measured around the planet by many observatories. The data retrieved is processed and turned into measurement indices. Daily measurements for the entire planet are made available through an estimate of the ''A''p-index, called the ''planetary A-index'' (PAI).Ionospheres of other planets and natural satellites

Objects in the Solar System that have appreciable atmospheres (i.e., all of the major planets and many of the larger natural satellites) generally produce ionospheres. Planets known to have ionospheres include Atmosphere of Venus#Upper atmosphere and ionosphere, Venus, Mars, Magnetosphere of Jupiter#Interaction with rings and moons, Jupiter, Saturn, Atmosphere of Uranus#Thermosphere and ionosphere, Uranus, Neptune and Pluto. The atmosphere of Titan includes an ionosphere that ranges from about to in altitude and contains carbon compounds.Accessed 2010-08-25 Ionospheres have also been observed at Io (moon), Io, Europa (moon), Europa, Ganymede (moon), Ganymede, and Triton (moon), Triton.

See also

* Aeronomy * Geospace * Space physics * Geophysics **International Reference Ionosphere

International Reference Ionosphere (IRI) is a common permanent scientific project of the Committee on Space Research (COSPAR) and the International Union of Radio Science (URSI) started 1968/69. It is the international standard empirical model f ...

** Ionospheric dynamo region

** Magnetospheric electric convection field

** Protonosphere

** Schumann resonances

** Van Allen radiation belt

* Radio

** Earth–ionosphere waveguide

** Fading

** Ionospheric absorption

** Ionospheric scintillation

** Line-of-sight propagation

** Sferics

* Related

** Canadian Geospace Monitoring

** High Frequency Active Auroral Research Program

** Ionospheric heater

** S4 Index

** Soft gamma repeater

** Sprite halo, Upper-atmospheric lightning

** Sura Ionospheric Heating Facility

** TIMED (Thermosphere Ionosphere Mesosphere Energetics and Dynamics)

Notes

References

* * * * * * * J. Lilensten, P.-L. Blelly: ''Du Soleil à la Terre, Aéronomie et météorologie de l'espace'', Collection Grenoble Sciences, Université Joseph Fourier Grenoble I, 2000. . * P.-L. Blelly, D. Alcaydé: ''Ionosphere'', in: Y. Kamide, A. Chian, ''Handbook of the Solar-Terrestrial Environment'', Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 189–220, 2007. * *External links

* Gehred, Paul, and Norm Cohen,SWPC's Radio User's Page

'.

Amsat-Italia project on Ionospheric propagation (ESA SWENET website)

Layman Level Explanations Of "Seemingly" Mysterious 160 Meter (MF/HF) Propagation Occurrences

USGS Geomagnetism Program

{{Authority control Ionosphere, Radio frequency propagation