Indiana In The Civil War on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

File:Don_Carlos_Buell.jpg,

File:Ambrose_Burnside2.jpg,

File:Lewis_Wallace.jpg,

File:General_Edward_Canby_525.jpg,

File:Robert_H._Milroy_-_Brady-Handy.jpg,

File:John_J._Reynolds_cph.3b20677.jpg,

File:Gen_Alvin_P_Hovey_06985r.jpg,

File:G_H_Chapman_UA_BGen_ACW.jpg,

File:Robert_S_Foster.jpg,

File:Edward_M._McCook_-_Brady-Handy.jpg,

File:J_W_McMillan_ACW.jpg,

File:John_Milton_Brannan_by_the_Studio_of_Mathew_Brady_-_NPG_81_M465.jpg,

File:R_A_Cameron_ACW.jpg,

File:John_Franklin_Miller.jpg,

File:Jefferson_C._Davis.jpg,

File:NKimball.jpg,

File:Solomon_Meredith_-_Brady-Handy.jpg,

File:Ebenezerdumontindiana.jpg,

File:William_M_Dunn.jpg,

File:James_Henry_Lane.jpg,

File:MDManson.jpg,

File:CharlesCruft.jpg,

File:RobertFrancisCatterson.jpg,

File:Walter_Q._Gresham_-_Brady-Handy.jpg,

File:WGrose.jpg,

File:MiloSHascall.jpg,

File:Pleasant_A._Hackleman.jpg,

File:George_Francis_McGinnis.jpg,

File:John_Coburn_congressman.jpg,

File:Thomas_W._Bennett_territorial_governor_-_Brady-Handy.jpg,

File:Pach_Brothers_-_Benjamin_Harrison.jpg,

File:Knefler_F.jpg,

File:GPBuell.JPG,

File:Colonel_Daniel_Macauley.jpg,

File:General_Henry_W._Lawton.jpg,

File:Sen_Henry_Smith_Lane.jpg,

File:Abierce.jpg,

Indianapolis was the site of Camp Morton, one of the Union's largest prisons for captured Confederate soldiers.

Indianapolis was the site of Camp Morton, one of the Union's largest prisons for captured Confederate soldiers.

Indiana troops participated in 308 military engagements, the majority of them between the

Indiana troops participated in 308 military engagements, the majority of them between the

Many of Indiana's regiments served with distinction in the war. The 19th Indiana Volunteer Infantry Regiment, 20th Indiana Infantry Regiment, and

Many of Indiana's regiments served with distinction in the war. The 19th Indiana Volunteer Infantry Regiment, 20th Indiana Infantry Regiment, and  The

The  The last casualty of the Civil War was a Hoosier serving in the

The last casualty of the Civil War was a Hoosier serving in the

The Civil War era showed the extent of the South's influence on Indiana. Much of southern and central Indiana had strong ties to the South. Many of Indiana's early settlers had come from the Confederate state of Virginia and from Kentucky. Governor Morton once complained to President Lincoln that "no other free state is so populated with southerners", which Morton believed kept him from being as forceful as he wanted to be.Thornbrough, pp. 108–09.

Due to their location across the

The Civil War era showed the extent of the South's influence on Indiana. Much of southern and central Indiana had strong ties to the South. Many of Indiana's early settlers had come from the Confederate state of Virginia and from Kentucky. Governor Morton once complained to President Lincoln that "no other free state is so populated with southerners", which Morton believed kept him from being as forceful as he wanted to be.Thornbrough, pp. 108–09.

Due to their location across the

More than half of the state's households, based on an average family size of four persons, contributed a family member to fight in the war, making the effects of the conflict widely felt throughout the state. More Hoosiers died in the Civil War than in any other conflict. Although twice as many Hoosiers served in World War II, almost twice as many died in the Civil War. After the war, veterans programs were initiated to help wounded soldiers with housing, food, and other basic needs. In addition, orphanages and asylums were established to assist women and children.

After the war, some women who had been especially active in supporting the war on the home front turned their organizational skills to other concerns, especially prohibition and woman suffrage. In 1874, for example, Zerelda Wallace, the wife of former Indiana governor David Wallace and stepmother of General Lew Wallace, became a founder of the Indiana chapter of the

More than half of the state's households, based on an average family size of four persons, contributed a family member to fight in the war, making the effects of the conflict widely felt throughout the state. More Hoosiers died in the Civil War than in any other conflict. Although twice as many Hoosiers served in World War II, almost twice as many died in the Civil War. After the war, veterans programs were initiated to help wounded soldiers with housing, food, and other basic needs. In addition, orphanages and asylums were established to assist women and children.

After the war, some women who had been especially active in supporting the war on the home front turned their organizational skills to other concerns, especially prohibition and woman suffrage. In 1874, for example, Zerelda Wallace, the wife of former Indiana governor David Wallace and stepmother of General Lew Wallace, became a founder of the Indiana chapter of the

online

* Foster Jr, John Michael. " 'For the Good of the Cause and the Protection of the Border': The Service of the Indiana Legion in the Civil War, 1861–1865." ''Civil War History'' 55.1 (2009): 31–55. Militia unit

summary

* * * Kramer, Carl E. ''Civil War Generals of Indiana'' (Arcadia Publishing, 2022). * Marshall, Joan E. "Aid for Union Soldiers' Families: A Comfortable Entitlement or a Pauper's Pittance? Indiana, 1861–1865." ''Social Service Review'' 78.2 (2004): 207–242

in JSTOR

* * * * * * *

online

* *

in JSTOR

* Madison, James H. "Civil War Memories and" Pardnership Forgittin'," 1865–1913." ''Indiana Magazine of History'' (2003): 198–230

online

* Rodgers, Thomas E. "Dupes and Demagogues: Caroline Krout's Narrative of Civil War Disloyalty." ''Historian'' 61#3 (1999): 621–638, analyzes a 1900 novel about Indiana Copperheads * Sacco, Nicholas W. "Kindling the Fires of Patriotism: The Grand Army of the Republic, Department of Indiana, 1866–1949" (MA Thesis, IUPUI. 2014) Bibliography pp 142–53.

online

* . Survey of recent scholarship and online resources dealing with the war and Indiana.

Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th s ...

, a state in the Midwest

The Midwestern United States, also referred to as the Midwest or the American Midwest, is one of four Census Bureau Region, census regions of the United States Census Bureau (also known as "Region 2"). It occupies the northern central part of ...

, played an important role in supporting the Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

. Despite anti-war

An anti-war movement (also ''antiwar'') is a social movement, usually in opposition to a particular nation's decision to start or carry on an armed conflict, unconditional of a maybe-existing just cause. The term anti-war can also refer to pa ...

activity within the state, and southern Indiana

Southern Indiana is a region consisting of the southern third of the state of Indiana.

The region's history and geography has led to a blend of Northern and Southern culture distinct from the remainder of Indiana. It is often considered to be p ...

's ancestral ties to the South

South is one of the cardinal directions or Points of the compass, compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Pro ...

, Indiana was a strong supporter of the Union. Indiana contributed approximately 210,000 Union soldiers, sailors, and marines. Indiana's soldiers served in 308 military engagements during the war; the majority of them in the western theater, between the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

and the Appalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, (french: Appalaches), are a system of mountains in eastern to northeastern North America. The Appalachians first formed roughly 480 million years ago during the Ordovician Period. They ...

. Indiana's war-related deaths reached 25,028 (7,243 from battle and 17,785 from disease). Its state government provided funds to purchase equipment, food, and supplies for troops in the field. Indiana, an agriculturally rich state containing the fifth-highest population in the Union, was critical to the North's success due to its geographical location, large population, and agricultural production. Indiana residents, also known as Hoosier

Hoosier is the official demonym for the people of the U.S. state of Indiana. The origin of the term remains a matter of debate, but "Hoosier" was in general use by the 1840s, having been popularized by Richmond resident John Finley's 1833 poem "T ...

s, supplied the Union with manpower for the war effort, a railroad network and access to the Ohio River

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of Illino ...

and the Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes in the mid-east region of North America that connect to the Atlantic Ocean via the Saint Lawrence River. There are five lakes ...

, and agricultural products such as grain and livestock. The state experienced two minor raids by Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

forces, and one major raid in 1863, which caused a brief panic in southern portions of the state and its capital city, Indianapolis

Indianapolis (), colloquially known as Indy, is the state capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the seat of Marion County. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the consolidated population of Indianapolis and Marion ...

.

Indiana experienced significant political strife during the war, especially after Governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

Oliver P. Morton

Oliver Hazard Perry Throck Morton (August 4, 1823 – November 1, 1877), commonly known as Oliver P. Morton, was a U.S. Republican Party politician from Indiana. He served as the 14th governor (the first native-born) of Indiana during the Amer ...

suppressed the Democratic-controlled state legislature, which had an anti-war (Copperhead) element. Major debates related to the issues of slavery and emancipation, military service for African Americans, and the draft, ensued. These led to violence. In 1863, after the state legislature failed to pass a budget and

left the state without the authority to collect taxes, Governor Morton acted outside his state's constitutional authority to secure funding through federal and private loans to operate the state government and avert a financial crisis.

The American Civil War altered Indiana's society, politics, and economy, beginning a population shift to central

Central is an adjective usually referring to being in the center of some place or (mathematical) object.

Central may also refer to:

Directions and generalised locations

* Central Africa, a region in the centre of Africa continent, also known as ...

and northern

Northern may refer to the following:

Geography

* North, a point in direction

* Northern Europe, the northern part or region of Europe

* Northern Highland, a region of Wisconsin, United States

* Northern Province, Sri Lanka

* Northern Range, a ra ...

Indiana, and contributed to a relative decline in the southern part of the state. Increased wartime manufacturing and industrial growth in Hoosier cities and towns ushered in a new era of economic prosperity. By the end of the war, Indiana had become a less rural state than it previously had been. Indiana's votes were closely split between the parties for several decades after the war, making it one of a few key swing state

In American politics, the term swing state (also known as battleground state or purple state) refers to any state that could reasonably be won by either the Democratic or Republican candidate in a statewide election, most often referring to pre ...

s that often decided national elections. Between 1868 and 1916, five Indiana politicians were vice-presidential nominees on the major party tickets. In 1888 Benjamin Harrison

Benjamin Harrison (August 20, 1833March 13, 1901) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 23rd president of the United States from 1889 to 1893. He was a member of the Harrison family of Virginia–a grandson of the ninth pr ...

, one of the state's former Civil War generals, was elected president of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United Stat ...

.

Indiana's contributions

Indiana was the first of the country's western states tomobilize

Mobilize may refer to:

* Mobilize (company), an American political technology platform

* ''Mobilize'' (Anti-Flag album) (2002)

* ''Mobilize'' (Grant-Lee Phillips album) (2001)

* Mobilize.org, an American not-for-profit

* Mobilize, a mobility c ...

for the Civil War. When news reached Indiana of the attack on Fort Sumter

Fort Sumter is a sea fort built on an artificial island protecting Charleston, South Carolina from naval invasion. Its origin dates to the War of 1812 when the British invaded Washington by sea. It was still incomplete in 1861 when the Battl ...

, South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

, on April 12, 1861, many Indiana residents were surprised, but their response was immediate. On the following day, two mass meetings were held in Indianapolis

Indianapolis (), colloquially known as Indy, is the state capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the seat of Marion County. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the consolidated population of Indianapolis and Marion ...

, the state capital of Indiana, and the state's position was decided: Indiana would remain in the Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

and would immediately contribute men to suppress the rebellion. On April 15, Indiana's governor, Oliver P. Morton

Oliver Hazard Perry Throck Morton (August 4, 1823 – November 1, 1877), commonly known as Oliver P. Morton, was a U.S. Republican Party politician from Indiana. He served as the 14th governor (the first native-born) of Indiana during the Amer ...

, issued a call for volunteer soldiers to meet the state's quota set by President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

.

Indiana's geographical location in the Midwest

The Midwestern United States, also referred to as the Midwest or the American Midwest, is one of four Census Bureau Region, census regions of the United States Census Bureau (also known as "Region 2"). It occupies the northern central part of ...

, its large population, and its agricultural production made the state's wartime support critical to the Union's success. Indiana, with the fifth-largest population of the states that remained in the Union, could supply much-needed manpower for the war effort, its railroad network and access to the Ohio River

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of Illino ...

and the Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes in the mid-east region of North America that connect to the Atlantic Ocean via the Saint Lawrence River. There are five lakes ...

could transport troops and supplies, and its agricultural yield, which became even more valuable to the Union after the loss of the rich farmland of the South, could provide grain and livestock.

Military service

On April 15, 1861, President Lincoln called for a total of 75,000 volunteers to join theUnion army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union (American Civil War), Union of the collective U.S. st ...

. On the same day, Governor Morton telegraphed the president offering 10,000 Indiana volunteers. The state's initial quota was set at six regiments (a total of 4,683 men) for three months of service. Orders were issued on April 16 to form the state's first regiments and to gather at Indianapolis. On the first day, five hundred men were encamped in the city; within a week more than 12,000 Hoosier volunteers had signed up to fight for the Union, nearly three times as many needed to meet the state's initial quota.Thornbrough, p. 124.

Governor Morton and Lew Wallace

Lewis Wallace (April 10, 1827February 15, 1905) was an American lawyer, Union general in the American Civil War, governor of the New Mexico Territory, politician, diplomat, and author from Indiana. Among his novels and biographies, Wallace is ...

, Indiana's adjutant general, established Camp Morton at the state fairgrounds in Indianapolis as the initial gathering place and training camp for the state's Union volunteers. (Camp Morton was converted to a prisoner-of-war camp in 1862.) By April 27, Indiana's first six regiments were fully organized as the First Brigade, Indiana Volunteers, under the command of Brigadier General Thomas A. Morris

Thomas Armstrong Morris (December 26, 1811 – March 22, 1904) was an American railroad executive and civil engineer from Kentucky and a soldier, serving as a brigadier general of the Indiana Militia in service to the Union during the early mo ...

. Members of companies not selected for these first regiments were given the option of volunteering for three years of service or returning home until they were needed; some companies formed into regiments in the state militia and were called into federal service within a few weeks.

Indiana ranked second among the states in terms of the percentage of its men of military age who served in the Union army. Indiana contributed 208,367 men, roughly 15 percent of the state's total population to serve in the Union army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union (American Civil War), Union of the collective U.S. st ...

,Other references state that 193,748 white men and 1,537 colored troops from Indiana served in the Union army. See See also and 2,130 to serve in the navy

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval warfare, naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral zone, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and ...

. Most of Indiana's soldiers were volunteers; 11,718 were re-enlistments.Barnhart, p. 221. Deserters numbered 10,846.

Indiana's volunteers responded to requests for military service in the early months of the war; however, as the war progressed and the number of casualties increased, the state government had to resort to conscription

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day un ...

(the draft) to fill its quotas.Madison, p. 159. Military conscription, which began in October 1862, was a divisive issue within the state. It was especially unpopular among Democrats, who viewed it as a threat to individual freedom and opposed legislation that allowed a man to purchase an exemption for $300 or pay another person to serve as his substitute. A total of 3,003 Hoosier men were drafted in October 1862; subsequent drafts in Indiana brought the total to 17,903.

Indiana's volunteers and draftees provided the Union army with 129 infantry regiments, 13 cavalry regiments, 3 cavalry companies, 1 regiment of heavy artillery, and 26 light artillery batteries.Thornbrough, p. 142. In addition to providing Union troops, Indiana also organized its own volunteer militia, known as the Indiana Legion. Formed in May 1861, the Legion was responsible for protecting Indiana's citizens from attack and maintaining order within the state.

More than 35 percent of the Hoosiers who joined the Union army became casualties: 24,416, roughly 12.6 percent of Indiana's soldiers who served, died in the conflict.Indiana's death toll from the war eventually reached 25,028, roughly 12.6 percent of those from Indiana who served. See See also Thornbrough, pp. 160–61. An estimated 48,568 soldiers, double the number of Hoosiers killed in the war, were wounded.Terrell, v. 1, Appendix, p. 115. The report explains that its totals, while not "entirely accurate," were based on the best data available at the time it was prepared. Indiana's war-related death toll eventually reached 25,028 (7,243 from battle and 17,785 from disease).Madison, p. 153.

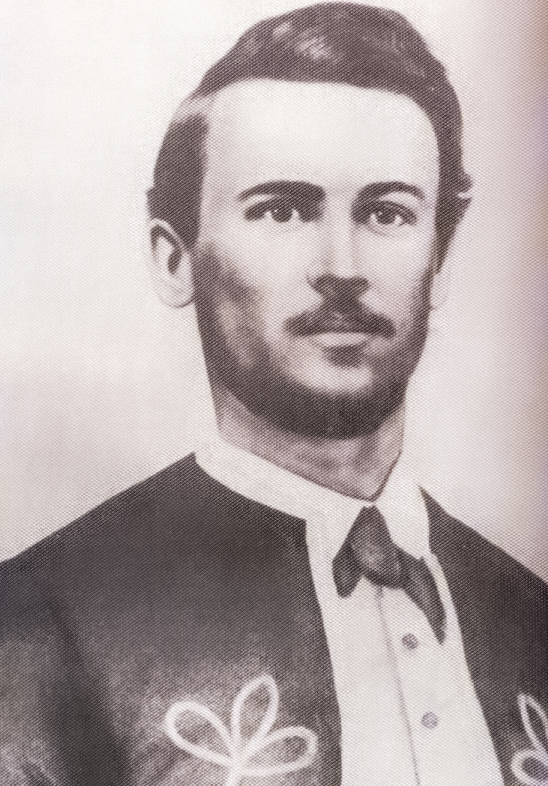

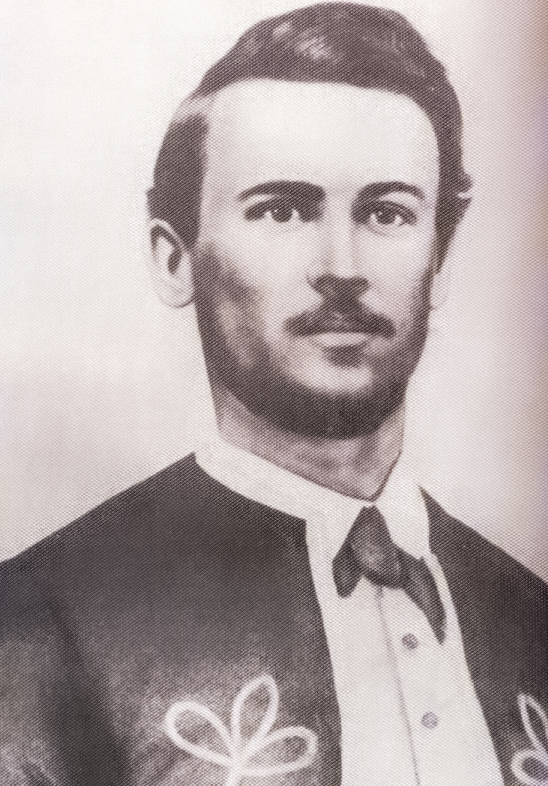

Notable leaders from Indiana

By the end of the war, Indiana could claim 46 general officers in the Union army who had at one time resided in the state. These men includedDon Carlos Buell

Don Carlos Buell (March 23, 1818November 19, 1898) was a United States Army officer who fought in the Seminole War, the Mexican–American War, and the American Civil War. Buell led Union armies in two great Civil War battles— Shiloh and Perr ...

, Ambrose Burnside

Ambrose Everett Burnside (May 23, 1824 – September 13, 1881) was an American army officer and politician who became a senior Union general in the Civil War and three times Governor of Rhode Island, as well as being a successful inventor ...

, Lew Wallace

Lewis Wallace (April 10, 1827February 15, 1905) was an American lawyer, Union general in the American Civil War, governor of the New Mexico Territory, politician, diplomat, and author from Indiana. Among his novels and biographies, Wallace is ...

, Robert H. Milroy, and Joseph J. Reynolds

Joseph Jones Reynolds (January 4, 1822 – February 25, 1899) was an American engineer, educator, and military officer who fought in the American Civil War and the postbellum Indian Wars.

Early life and career

Reynolds was born in Fleming ...

, and Jefferson C. Davis

Jefferson Columbus Davis (March 2, 1828 – November 30, 1879) was a regular officer of the United States Army during the American Civil War, known for the similarity of his name to that of Confederate President Jefferson Davis and for his kil ...

, among others.

Training and support

Slightly more than 60 percent of Indiana's regiments mustered into service and trained atIndianapolis

Indianapolis (), colloquially known as Indy, is the state capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the seat of Marion County. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the consolidated population of Indianapolis and Marion ...

.Bodenhamer and Barrows, eds., p. 441. Other camps for Union soldiers were established elsewhere in the state, including Fort Wayne

Fort Wayne is a city in and the county seat of Allen County, Indiana, United States. Located in northeastern Indiana, the city is west of the Ohio border and south of the Michigan border. The city's population was 263,886 as of the 2020 Censu ...

, Gosport

Gosport ( ) is a town and non-metropolitan borough on the south coast of Hampshire, South East England. At the 2011 Census, its population was 82,662. Gosport is situated on a peninsula on the western side of Portsmouth Harbour, opposite t ...

, Jeffersonville, Kendallville, Lafayette

Lafayette or La Fayette may refer to:

People

* Lafayette (name), a list of people with the surname Lafayette or La Fayette or the given name Lafayette

* House of La Fayette, a French noble family

** Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette (1757� ...

, Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, Virginia, the capital of Virginia, United States

* Richmond, London, a part of London

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town in England

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, ...

, South Bend

South Bend is a city in and the county seat of St. Joseph County, Indiana, on the St. Joseph River near its southernmost bend, from which it derives its name. As of the 2020 census, the city had a total of 103,453 residents and is the fourt ...

, Terre Haute

Terre Haute ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Vigo County, Indiana, United States, about 5 miles east of the state's western border with Illinois. As of the 2010 census, the city had a population of 60,785 and its metropolitan area had a ...

, Wabash, and in LaPorte County.

Governor Morton was called the "Soldier's Friend" because of his efforts to equip, train, and care for Union soldiers in the field. Indiana's state government financed a large portion of the costs involved in preparing its regiments for war, including housing, feeding, and equipping them, before their assignment to the standing Union armies. To secure arms for Indiana's troops, the governor appointed purchasing agents to act on the state's behalf. Early in the war, for example, Robert Dale Owen

Robert Dale Owen (7 November 1801 – 24 June 1877) was a Scottish-born Welsh social reformer who immigrated to the United States in 1825, became a U.S. citizen, and was active in Indiana politics as member of the Democratic Party in the Indian ...

purchased more than $891,000 in arms, clothing, blankets, and cavalry equipment for Indiana troops; the state government made additional purchases of arms and supplies exceeding $260,000. To provide ammunition, Morton established a state-owned arsenal at Indianapolis served the Indiana militia, home guard, and as a backup supply depot for the Union army. The state arsenal operated until April 1864, employing 700 at its peak; many of its employees were women. A federal arsenal was also established in Indianapolis in 1863.

The Indiana Sanitary Commission, created in 1862, and soldiers' aid societies throughout the state raised funds and gathered supplies for troops in the field. Hoosiers also provided other forms of support for soldiers and their families, including a Soldiers' Home and a Ladies' Home, and Orphans' Home to help meet the needs of Indiana's soldiers and their families as they passed through Indianapolis.

During the war some women took on the added responsibility of running family farms and businesses. Hoosier women also contributed to the war effort as nurses and volunteers in charitable organizations, most commonly the local Ladies' Aid Societies. In January 1863 Governor Morton and the Indiana Sanitary Commission began recruiting women to work as nurses in military hospitals and on hospital ships and transport trains in Indiana as well as the South

South is one of the cardinal directions or Points of the compass, compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Pro ...

; others served behind the lines at battlefields. It is not known how many women from Indiana became wartime nurses, but several died during their service, including Eliza George

Elizabeth "Eliza" George (October 20, 1808 – May 9, 1865), nicknamed "Mother George" by the Union army soldiers under her care, served the final two-and-a-half years of her life as a volunteer nurse in the South during the American Civil War. I ...

of Fort Wayne

Fort Wayne is a city in and the county seat of Allen County, Indiana, United States. Located in northeastern Indiana, the city is west of the Ohio border and south of the Michigan border. The city's population was 263,886 as of the 2020 Censu ...

and Hannah Powell and Asinae Martin of Goshen. Oher women nurses who returned to their homes in Indiana following their service include Jane Chambers McKinney Graydon, Jane Merrill Ketcham, and Bettie Bates, all three from Indianapolis

Indianapolis (), colloquially known as Indy, is the state capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the seat of Marion County. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the consolidated population of Indianapolis and Marion ...

; Harriet Reese Colfax and Lois Dennett from Michigan City; Adelia Carter New, among the few women from Indiana who served at hospitals in the East

East or Orient is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from west and is the direction from which the Sun rises on the Earth.

Etymology

As in other languages, the word is formed from the fa ...

; Amanda Way of Winchester

Winchester is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city in Hampshire, England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government Districts of England, district, at the western end of the South Downs Nation ...

; Mary F. Thomas from Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, Virginia, the capital of Virginia, United States

* Richmond, London, a part of London

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town in England

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, ...

, who was trained as a physician; members of the Sisters of the Holy Cross

The Sisters of the Holy Cross (CSC) are one of three Catholic congregations of religious sisters which trace their origins to the foundation of the Congregation of Holy Cross by the Blessed Basil Anthony Moreau, CSC, at Le Mans, France in 1837. ...

; and members of the Sisters of Providence of Saint Mary of the Woods, among other women.

Wounded soldiers were cared for at Indiana facilities in Clark County ( Port Fulton, near Jeffersonville and New Albany), Jefferson County (Madison Madison may refer to:

People

* Madison (name), a given name and a surname

* James Madison (1751–1836), fourth president of the United States

Place names

* Madison, Wisconsin, the state capital of Wisconsin and the largest city known by this ...

), Knox County (Vincennes

Vincennes (, ) is a commune in the Val-de-Marne department in the eastern suburbs of Paris, France. It is located from the centre of Paris. It is next to but does not include the Château de Vincennes and Bois de Vincennes, which are attached ...

), Marion County (Indianapolis), Warrick County

Warrick County is a county located in the U.S. state of Indiana. As of 2020, the population was 63,898. The county seat is Boonville. It was organized in 1813 and was named for Captain Jacob Warrick, an Indiana militia company commander killed ...

( Newburgh), and Vanderburgh County

Vanderburgh County is a county in the U.S. state of Indiana. As of 2010, the population was 179,703. The county seat is in Evansville. While Vanderburgh County was the seventh-largest county in 2010 population with 179,703 people, it is also the ...

(Evansville

Evansville is a city in, and the county seat of, Vanderburgh County, Indiana, United States. The population was 118,414 at the 2020 census, making it the state's third-most populous city after Indianapolis and Fort Wayne, the largest city in S ...

). Jefferson General Hospital

Jefferson General Hospital was the third-largest hospital during the American Civil War, located at Port Fulton, Indiana (now part of Jeffersonville, Indiana) and was active between February 21, 1864 and December 1866. The land was owned by U.S ...

at Port Fulton, Indiana

Port Fulton was a town located two miles up the river from Louisville, within present-day Jeffersonville, Indiana. At its height it stretched from the Ohio River to modern-day 10th Street, and from Crestview to Jefferson/Main Streets.

Port Ful ...

, now a part of present-day Jeffersonville, was briefly the third-largest hospital in the United States. Between 1864, when Jefferson General opened, and 1866, when it closed, the hospital treated 16,120 patients.

Prison camps

Indianapolis was the site of Camp Morton, one of the Union's largest prisons for captured Confederate soldiers.

Indianapolis was the site of Camp Morton, one of the Union's largest prisons for captured Confederate soldiers. Lafayette

Lafayette or La Fayette may refer to:

People

* Lafayette (name), a list of people with the surname Lafayette or La Fayette or the given name Lafayette

* House of La Fayette, a French noble family

** Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette (1757� ...

, Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, Virginia, the capital of Virginia, United States

* Richmond, London, a part of London

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town in England

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, ...

, and Terre Haute, Indiana

Terre Haute ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Vigo County, Indiana, United States, about 5 miles east of the state's western border with Illinois. As of the 2010 census, the city had a population of 60,785 and its metropolitan area had a ...

, occasionally held prisoners of war as well.

Military cemeteries

Two national military cemeteries were established in Indiana as a result of the war. In 1882 the federal government established inNew Albany, Indiana

New Albany is a city in Floyd County, Indiana, United States, situated along the Ohio River, opposite Louisville, Kentucky. The population was 37,841 as of the 2020 census. The city is the county seat of Floyd County. It is bounded by I-265 t ...

, the New Albany National Cemetery

New Albany National Cemetery is a United States National Cemetery located in the city of New Albany, Indiana, New Albany, in Floyd County, Indiana. Administered by the United States Department of Veterans Affairs, it encompasses , and as of the en ...

, one of fourteen national cemeteries established that year. In 1866 the federal government authorized a national cemetery for Indianapolis; Crown Hill National Cemetery was established within the grounds of Crown Hill Cemetery

Crown Hill Cemetery is a historic rural cemetery located at 700 West 38th Street in Indianapolis, Marion County, Indiana. The privately owned cemetery was established in 1863 at Strawberry Hill, whose summit was renamed "The Crown", a high poi ...

, a privately owned cemetery northwest of downtown.

Conflicts

Indiana troops participated in 308 military engagements, the majority of them between the

Indiana troops participated in 308 military engagements, the majority of them between the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

and the Appalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, (french: Appalaches), are a system of mountains in eastern to northeastern North America. The Appalachians first formed roughly 480 million years ago during the Ordovician Period. They ...

. Soldiers from Indiana were present on most of the Civil War battlefields, beginning with the first engagement involving Hoosier troops at the Battle of Philippi (West Virginia)

The Battle of Philippi formed part of the Western Virginia Campaign of the American Civil War and was fought in and around Philippi, Virginia (now West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern ...

on June 3, 1861, to the Battle of Palmetto Ranch

The Battle of Palmito Ranch, also known as the Battle of Palmito Hill, is considered by some criteria as the final battle of the American Civil War. It was fought May 12 and 13, 1865, on the banks of the Rio Grande east of Brownsville, Texas, an ...

(Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2 ...

) on May 13, 1865. Nearly all the fighting was outside of the state's boundaries. Only one significant conflict, known as Morgan's Raid

Morgan's Raid was a diversionary incursion by Confederate cavalry into the Union states of Indiana, Kentucky, Ohio and West Virginia during the American Civil War. The raid took place from June 11 to July 26, 1863, and is named for the commander ...

, occurred on Indiana soil during the war. The raid, which caused a brief panic in Indianapolis and southern Indiana, was preceded by two minor incursions into Indiana.

Raids

On July 18, 1862, during theNewburgh Raid

The Newburgh Raid was a successful raid by Confederate partisans on Newburgh, Indiana, on July 18, 1862, making it the first town in a northern state to be captured during the American Civil War. Confederate colonel Adam Rankin Johnson led the ...

, Confederate officer Adam Johnson briefly captured Newburgh, Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th s ...

, making it the first town in a Northern state to be captured during the American Civil War. Johnson and his men succeeded after convincing the town's Union garrison

A garrison (from the French ''garnison'', itself from the verb ''garnir'', "to equip") is any body of troops stationed in a particular location, originally to guard it. The term now often applies to certain facilities that constitute a mil ...

that they had cannon

A cannon is a large- caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder ...

on the surrounding hills (they were merely camouflaged stovepipes). The raid convinced the federal government of the need to supply Indiana with a permanent force of regular Union Army soldiers to counter future raids.

On June 17, 1863, in preparation for a planned cavalry offensive by Confederate troops under the command of John Hunt Morgan

John Hunt Morgan (June 1, 1825 – September 4, 1864) was an American soldier who served as a Confederate general in the American Civil War of 1861–1865.

In April 1862, Morgan raised the 2nd Kentucky Cavalry Regiment (CSA) and fought in t ...

, one of his officers, Captain Thomas Hines and approximately 80 men crossed the Ohio River to search for horses and support from Hoosiers in southern Indiana. During the minor incursion, which became known as Hines' Raid, local citizens and members of Indiana's home guard pursued the Confederates and succeeded in capturing most of them without a fight. Hines and a few of his men escaped across the river into Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia to ...

.Barnhart, pp. 212–13.

Morgan's Raid

Morgan's Raid was a diversionary incursion by Confederate cavalry into the Union states of Indiana, Kentucky, Ohio and West Virginia during the American Civil War. The raid took place from June 11 to July 26, 1863, and is named for the commander ...

, the Confederate army's major incursion into Indiana, occurred a month after Hines' raid. On July 8, 1863, General Morgan crossed the Ohio River, landing at Mauckport, Indiana

Mauckport is a town in Heth Township, Harrison County, Indiana, Heth Township, Harrison County, Indiana, Harrison County, Indiana, along the Ohio River. The population was 81 at the 2010 census.

History

In the earliest times Daniel Boone and his ...

, with 2,400 troopers. Their arrival was initially contested by a small party from the Indiana Legion, who withdrew after Morgan's men began firing artillery from the river's southern shore. The state militia quickly retreated towards Corydon, Indiana

Corydon is a town in Harrison Township, Harrison County, Indiana. Located north of the Ohio River in the extreme southern part of the U.S. state of Indiana, it is the seat of government for Harrison County. Corydon was founded in 1808 and served ...

, where a larger body was gathering to block Morgan's advance. The Confederates advanced rapidly on the town and engaged in the Battle of Corydon

The Battle of Corydon was a minor engagement that took place July 9, 1863, just south of Corydon, which had been the original capital of Indiana until 1825, and was the county seat of Harrison County. The attack occurred during Morgan's Raid in ...

. After a brief but fierce fight, Morgan took command of high ground south of town, and Corydon's local militia and citizens promptly surrendered after Morgan's artillery fired two warning shots. Corydon was sacked, but little damage was done to its buildings. Morgan continued his raid north and burned most of the town of Salem.

When Morgan's movements appeared to be headed toward Indianapolis, panic spread through the capital city. Governor Morton had called up the state militia as soon as Morgan's intention to cross into the state was known, and more than 60,000 men of all ages volunteered to protect Indiana against Morgan's men.

Morgan considered attacking Camp Morton, the prisoner-of-war camp in Indianapolis, to free more than 5,000 Confederate prisoners of war imprisoned there, but decided against it. Instead, his raiders turned abruptly east and began moving towards Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

. With Indiana's militia in pursuit, Morgan's men continued to raid and pillage their way toward the Indiana-Ohio border, crossing into Ohio on July 13. By the time Morgan left Indiana, his raid had become a desperate attempt to escape to the South. He was captured on July 26 in Ohio.

Indiana regiments

Many of Indiana's regiments served with distinction in the war. The 19th Indiana Volunteer Infantry Regiment, 20th Indiana Infantry Regiment, and

Many of Indiana's regiments served with distinction in the war. The 19th Indiana Volunteer Infantry Regiment, 20th Indiana Infantry Regiment, and 27th Indiana Infantry Regiment

The 27th Indiana Infantry Regiment was an infantry regiment that served in the Union Army during the American Civil War.

Service

*The 27th Indiana Volunteer Infantry was organized at Indianapolis, Indiana, on September 12, 1861.

*First Battle of ...

suffered the highest casualties of the state's infantry regiments as a percentage of the regiment's total enrollment.

Indiana's first six regiments organized during the Civil War were the 6th, 7th, 8th, 9th, 10th, and 11th Indiana infantry regiments. The men in these regiments volunteered for three months of service at the start of the war, but their brief terms proved inadequate; most of these soldiers re-enlisted for three additional years of service.

By the end of 1861, forty-seven Indiana regiments had mustered into service; most of the men enlisted for terms of three years. The majority of the three-year regiments were deployed in the western theater. In 1862 another forty-one regiments from Indiana were mustered into service; about half were sent to the eastern theater and the other half remained in the west. During 1863 six more regiments were mustered into service to replace the casualties of the first two years' fighting, and on July 8, 1863, and additional thirteen temporary regiments were established during Morgan's Raid into southern Indiana. The men in these temporary regiments enlisted for terms of three months, but the regiments disbanded once the threat posed by Morgan's troops was gone. In 1864 twenty-one Indiana regiments mustered into service. As the fighting declined, most of Indiana's regiments mustered out of service by the end of 1864, but some continued to serve. During 1865 fourteen additional Indiana regiments were mustered into a year of service. On November 10, 1865, the 13th Regiment Indiana Cavalry became the state's final regiment to be mustered out of the U.S. Army.

The

The 11th Indiana Infantry Regiment

The 11th Indiana Zouaves (officially, "11th Regiment, Indiana Volunteer Infantry") was an infantry regiment that served in the Union Army during the American Civil War.

Service 3 Month

The 11th Indiana was enlisted in Indianapolis, Indiana, to ...

, also known as the Indiana Zouaves, under the command of Lew Wallace, was the first regiment organized in Indiana during the Civil War and the first one to march into battle. The 11th Indiana fought in the Battle of Fort Donelson

The Battle of Fort Donelson was fought from February 11–16, 1862, in the Western Theater of the American Civil War. The Union capture of the Confederate fort near the Tennessee–Kentucky border opened the Cumberland River, an important ave ...

, the Siege of Vicksburg

The siege of Vicksburg (May 18 – July 4, 1863) was the final major military action in the Vicksburg campaign of the American Civil War. In a series of maneuvers, Union Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and his Army of the Tennessee crossed the Missis ...

, the second day of the Battle of Shiloh

The Battle of Shiloh (also known as the Battle of Pittsburg Landing) was fought on April 6–7, 1862, in the American Civil War. The fighting took place in southwestern Tennessee, which was part of the war's Western Theater. The battlefield i ...

, and elsewhere. In 1861 the 9th Indiana Infantry Regiment

The 9th Indiana Volunteer Infantry Regiment was a volunteer infantry regiment in the Union Army during the American Civil War. It was organized on April 22, 1861, for three-months' service in Indianapolis. After being reorganized for three years' s ...

became one of the first Hoosier regiments to see action in the war. The 9th Indiana fought in many major battles, including the Battle of Shiloh, the Battle of Stones River

The Battle of Stones River, also known as the Second Battle of Murfreesboro, was a battle fought from December 31, 1862, to January 2, 1863, in Middle Tennessee, as the culmination of the Stones River Campaign in the Western Theater of the Ame ...

, the Atlanta Campaign, and the Battle of Nashville

The Battle of Nashville was a two-day battle in the Franklin-Nashville Campaign that represented the end of large-scale fighting west of the coastal states in the American Civil War. It was fought at Nashville, Tennessee, on December 15–16, 1 ...

, among others.

The 14th Indiana Infantry Regiment was nicknamed the "Gibraltar Brigade" for maintaining its position at the Battle of Antietam

The Battle of Antietam (), or Battle of Sharpsburg particularly in the Southern United States, was a battle of the American Civil War fought on September 17, 1862, between Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia and Union G ...

. It secured Cemetery Hill on the first day of the three-day fight at the Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg () was fought July 1–3, 1863, in and around the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, by Union and Confederate forces during the American Civil War. In the battle, Union Major General George Meade's Army of the Po ...

, where it lost 123 of its men. The 19th Indiana Volunteer Infantry Regiment, part of the Iron Brigade

The Iron Brigade, also known as The Black Hats, Black Hat Brigade, Iron Brigade of the West, and originally King's Wisconsin Brigade was an infantry brigade in the Union Army of the Potomac during the American Civil War. Although it fought enti ...

, made critical contributions to some of the most important engagements of the war, including the Second Battle of Bull Run

The Second Battle of Bull Run or Battle of Second Manassas was fought August 28–30, 1862, in Prince William County, Virginia, as part of the American Civil War. It was the culmination of the Northern Virginia Campaign waged by Confederate ...

, but was almost completely destroyed in the Battle of Gettysburg, where it sustained 210 casualties. The 19th Indiana suffered the heaviest battle losses of any Indiana unit; 15.9 percent of its men were killed or mortally wounded during the war.Thornbrough, p. 161. The 27th Indiana Infantry Regiment

The 27th Indiana Infantry Regiment was an infantry regiment that served in the Union Army during the American Civil War.

Service

*The 27th Indiana Volunteer Infantry was organized at Indianapolis, Indiana, on September 12, 1861.

*First Battle of ...

earned the nickname "giants in the cornfield" at the Battle of Antietam. The regiment also fought at the Battle of Chancellorsville

The Battle of Chancellorsville, April 30 – May 6, 1863, was a major battle of the American Civil War (1861–1865), and the principal engagement of the Chancellorsville campaign.

Chancellorsville is known as Lee's "perfect battle" because h ...

, the Battle of Gettysburg, and in the Atlanta Campaign. The 27th Indiana's casualties were 15.3 percent of its total enrollment, nearly as many as the 19th Indiana.

Most of Indiana's regimental units were organized within towns or counties, but ethnic units were also formed, including the 32nd Indiana, a German-American infantry regiment, and the 35th Indiana, composed of Irish Americans. The 28th Regiment U.S. Colored Troops, formed at Indianapolis between December 24, 1863, and March 31, 1864, was the only black regiment formed in Indiana during the war. It trained at Indianapolis's Camp Fremont, near Fountain Square

A fountain square is a park or plaza in a city that features a fountain. It may stand alone or as part of a larger public park.

In the United States, there are numerous fountain squares, many of which are actually called "fountain square." Ther ...

, and included 518 enlisted men who signed on for three years of service. The regiment lost 212 men during the conflict.Bodenhamer and Barrows, eds., p.442. The 28th participated in the Siege of Petersburg

The Richmond–Petersburg campaign was a series of battles around Petersburg, Virginia, fought from June 9, 1864, to March 25, 1865, during the American Civil War. Although it is more popularly known as the Siege of Petersburg, it was not a cla ...

and at the Battle of the Crater

The Battle of the Crater was a battle of the American Civil War, part of the siege of Petersburg. It took place on Saturday, July 30, 1864, between the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, commanded by General Robert E. Lee, and the Union Arm ...

, where twenty-two of its men were killed. At the end of the war the regiment served in Texas, where it mustered out of service on November 8, 1865.

The last casualty of the Civil War was a Hoosier serving in the

The last casualty of the Civil War was a Hoosier serving in the 34th Regiment Indiana Infantry

The 34th Indiana Veteran Volunteer Infantry Regiment, nicknamed ''The Morton Rifles'', was an Infantry Regiment that served in the Union Army during the American Civil War. It had the distinction of fighting in the last land action of the war, the ...

. Private John J. Williams died at the Battle of Palmetto Ranch

The Battle of Palmito Ranch, also known as the Battle of Palmito Hill, is considered by some criteria as the final battle of the American Civil War. It was fought May 12 and 13, 1865, on the banks of the Rio Grande east of Brownsville, Texas, an ...

on May 13, 1865.

Politics

Hoosiers voted in favor of the Republicans in 1860, and in January 1861, Indiana's newly elected lieutenant governor, Oliver P. Morton, became governor afterHenry Smith Lane

Henry Smith Lane (February 24, 1811 – June 19, 1881) was a United States representative, Senator, and the 13th Governor of Indiana; he was by design the shortest-serving Governor of Indiana, having made plans to resign the office should his ...

resigned from the office to take a vacant seat in the U.S. Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and powe ...

. Hoosiers also helped Abraham Lincoln win the presidency in the 1860 election and voted in favor of his re-election in 1864. Although Lincoln won only 40 percent of the country's popular vote in the U.S. presidential election in 1860, he earned Indiana's 13 electoral votes with 51.09 percent of its popular vote, compared to Stephen Douglas

Stephen Arnold Douglas (April 23, 1813 – June 3, 1861) was an American politician and lawyer from Illinois. A senator, he was one of two nominees of the badly split Democratic Party for president in the 1860 presidential election, which was ...

's 42.44 percent, John Breckenridge's 4.52 percent, and John Bell's 1.95 percent. In the 1864 presidential election

A presidential election is the election of any head of state whose official title is President.

Elections by country

Albania

The president of Albania is elected by the Assembly of Albania who are elected by the Albanian public.

Chile

The pre ...

, Lincoln once again carried the state, this time by a wider margin, earning Indiana's electoral votes with 53.6 percent of the state's popular vote compared to George McClellan

George Brinton McClellan (December 3, 1826 – October 29, 1885) was an American soldier, Civil War Union general, civil engineer, railroad executive, and politician who served as the 24th governor of New Jersey. A graduate of West Point, McCl ...

's 46.4 percent.

As one of Lincoln's "war governors", Morton and the president maintained a close alliance throughout the war; however, as war casualties mounted, Hoosiers began to doubt the necessity of war and many became concerned over the increase in governmental power and the loss of personal freedom, which resulted in major conflicts between the state's Republicans and Democrats.

Southern influence

The Civil War era showed the extent of the South's influence on Indiana. Much of southern and central Indiana had strong ties to the South. Many of Indiana's early settlers had come from the Confederate state of Virginia and from Kentucky. Governor Morton once complained to President Lincoln that "no other free state is so populated with southerners", which Morton believed kept him from being as forceful as he wanted to be.Thornbrough, pp. 108–09.

Due to their location across the

The Civil War era showed the extent of the South's influence on Indiana. Much of southern and central Indiana had strong ties to the South. Many of Indiana's early settlers had come from the Confederate state of Virginia and from Kentucky. Governor Morton once complained to President Lincoln that "no other free state is so populated with southerners", which Morton believed kept him from being as forceful as he wanted to be.Thornbrough, pp. 108–09.

Due to their location across the Ohio River

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of Illino ...

from Louisville

Louisville ( , , ) is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky and the 28th most-populous city in the United States. Louisville is the historical seat and, since 2003, the nominal seat of Jefferson County, on the Indiana border.

...

, Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia to ...

, the Indiana cities of Jeffersonville, New Albany, and Port Fulton saw increased trade and military activity. Some of this increase was due to Kentucky's desire to stay neutral in the war. In addition, Kentucky was home to many Confederate sympathizers. Military bases in southern Indiana were needed to support Union operations against Confederates in Kentucky, and it was safer to store war supplies in towns on the north side of the river. Jeffersonville served as an important military depot for Union troops heading south. Towards the end of the war, Port Fulton was home to the third-largest hospital in the United States, Jefferson General Hospital

Jefferson General Hospital was the third-largest hospital during the American Civil War, located at Port Fulton, Indiana (now part of Jeffersonville, Indiana) and was active between February 21, 1864 and December 1866. The land was owned by U.S ...

.

In 1861, Kentucky's governor Beriah Magoffin

Beriah Magoffin (April 18, 1815 – February 28, 1885) was the 21st Governor of Kentucky, serving during the early part of the Civil War. Personally, Magoffin adhered to a states' rights position, including the right of a state to secede from t ...

refused to allow pro-Union forces to mobilize in his state and issued a similar order regarding Confederate forces. Governor Morton, who repeatedly came to the military rescue of Kentucky's pro-Union government during the war and became known as the "Governor of Indiana and Kentucky" allowed Kentuckians to form Union regiments on Indiana soil. Kentucky troops, especially from Louisville, which included the 5th Kentucky Infantry and others, at Indiana's Camp Joe Holt. Camp Joe Holt was established in Clarksville, Indiana

Clarksville is a town in Clark County, Indiana, United States, along the Ohio River and is a part of the Louisville Metropolitan area. The population was 22,333 at the 2020 census. The town was founded in 1783 by early resident George Rogers Cla ...

, between Jeffersonville and New Albany.

Jesse D. Bright

Jesse David Bright (December 18, 1812 – May 20, 1875) was the ninth Lieutenant Governor of Indiana and U.S. Senator from Indiana who served as President pro tempore of the Senate on three occasions. He was the only senator from a Northern sta ...

, who represented Indiana in the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

had been a leader among the state's Democratics for several years prior to the outbreak of the war. In January 1862, Bright was expelled from the Senate on allegations of disloyalty to the Union. He had written a letter of introduction for an arms merchant addressed to "His Excellency, Jefferson Davis

Jefferson F. Davis (June 3, 1808December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the United States Senate and the House of Representatives as a ...

, President of the Confederation." In the letter, Bright offered the merchant's services as a firearms supplier. Bright's Senate replacement was Joseph A. Wright

Joseph Albert Wright (April 17, 1810 – May 11, 1867) was the tenth governor of the U.S. state of Indiana from December 5, 1849, to January 12, 1857, most noted for his opposition to banking. His positions created a rift between him and the I ...

, a pro-Union Democrat and former Indiana governor. As of 2015, Bright was the last senator to be expelled by the Senate.

Political conflict

Hoosiers cooperated in support of the war effort at its outset, but political differences soon erupted into the "most violent political battles" in the state's history. The major debates, which also led to violence, related to the issues of slavery and emancipation; military service for African Americans; and the draft. On April 24, 1861, Morton addressed a special session of theIndiana General Assembly

The Indiana General Assembly is the state legislature, or legislative branch, of the state of Indiana. It is a bicameral legislature that consists of a lower house, the Indiana House of Representatives, and an upper house, the Indiana Senate. ...

to obtain the legislature's approval to borrow and spend funds to purchase arms and supplies for Indiana's troops. Morton also urged Indiana's legislators to set aside party considerations for the duration of the war and unite in defense of the Union, but the Republicans and Democrats did not cooperate for long. Initially, the Democratic-controlled legislature was supportive of Morton's measures and passed the legislation he requested. After the state legislature adjourned in May, however, some of the state's prominent Democrats changed their opinion about the war. In January 1862 the Democrats clarified their position at a state convention chaired by Thomas Hendricks

Thomas Andrews Hendricks (September 7, 1819November 25, 1885) was an American politician and lawyer from Indiana who served as the 16th governor of Indiana from 1873 to 1877 and the 21st vice president of the United States from March until his ...

. Indiana's Democrats stated their support for the integrity of the Union and the war effort, but opposed emancipation of blacks and the abolition of slavery.

After the elections in the fall of 1862, Governor Morton feared that the legislature's Democratic majority would attempt to hinder the war effort, reduce his authority, and vote to secede from the Union. After the legislative session convened in 1863, all but four Republican legislators stayed away from Indianapolis to prevent the general assembly from attaining the quorum

A quorum is the minimum number of members of a deliberative assembly (a body that uses parliamentary procedure, such as a legislature) necessary to conduct the business of that group. According to ''Robert's Rules of Order Newly Revised'', the ...

it needed to pass legislation, including funding the state government or making tax provisions. This rapidly led to a crisis as the state government began to run out of money to conduct its business and was nearly bankrupt. Going beyond his constitutional powers, Morton solicited millions of dollars in federal and private loans to avert the crisis. To obtain funds to run the state government, Morton turned to James Lanier

James Franklin Doughty Lanier (November 22, 1800 – August 27, 1881) was an entrepreneur who lived in Madison, Indiana prior to the outbreak of the American Civil War (1861–1865). Lanier became a wealthy banker with interests in pork packing, ...

, a wealthy banker from Madison Madison may refer to:

People

* Madison (name), a given name and a surname

* James Madison (1751–1836), fourth president of the United States

Place names

* Madison, Wisconsin, the state capital of Wisconsin and the largest city known by this ...

, Indiana. On two occasions, Lanier provided the state with more than $1 million (USD

The United States dollar (symbol: $; code: USD; also abbreviated US$ or U.S. Dollar, to distinguish it from other dollar-denominated currencies; referred to as the dollar, U.S. dollar, American dollar, or colloquially buck) is the official ...

) in unsecured loans. Morton's move was successful, and he was able to fund the state government and the war effort in Indiana. There was little the legislature could do but watch.

Indiana's political polarity continued to worsen after the Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the Civil War. The Proclamation changed the legal sta ...

(1863) made freeing the slaves a war goal. Many of the formerly pro-war Democrats moved to openly oppose the war, and Governor Morton began a crackdown on dissidents. During one notorious incident in May 1863, the governor had soldiers disrupt a Democratic state convention in Indianapolis, causing what would latter be referred to as the Battle of Pogue's Run

The "Battle" of Pogue's Run took place in Indianapolis, Indiana on May 20, 1863. It was believed that many of the delegates to the Democrat state convention had firearms, in the hope of inciting a rebellion. Union soldiers entered the hall th ...

. No regular session of the Indiana General Assembly was convened until June 1865.

While most of the state was decidedly pro-Union, a group of Southern sympathizers known as the Knights of the Golden Circle

The Knights of the Golden Circle (KGC) was a secret society founded in 1854 by American George W. L. Bickley, the objective of which was to create a new country, known as the Golden Circle ( es, Círculo Dorado), where slavery would be legal. T ...

had a strong presence in southern Indiana. The group proved enough of a threat that General Lew Wallace, commander of Union forces in the region, spent considerable time countering their activities. By June 1863, the group was successfully broken up. Many Golden Circle members were arrested without formal charges, the pro-Confederate press was prevented from printing anti-war material, and the writ of ''habeas corpus

''Habeas corpus'' (; from Medieval Latin, ) is a recourse in law through which a person can report an unlawful detention or imprisonment to a court and request that the court order the custodian of the person, usually a prison official, t ...

'' was denied to anyone suspected of disloyalty. In reaction to Governor Morton's actions against dissenters, Indiana's Democrats Party called him a "dictator" and an "underhanded mobster;" Republicans countered that the Democrats were using treasonable and obstructionist tactics in the conduct of the war.

Confederate special agent Thomas Hines went to French Lick

French Lick is a town in French Lick Township, Orange County, Indiana. The population was 1,807 at the time of the 2010 census. In November 2006, the French Lick Resort Casino, the state's tenth casino in the modern legalized era, opened, drawing ...

in June 1863, seeking support for Confederate General John Hunt Morgan's eventual raid into Indiana. Hines met with Sons of Liberty

The Sons of Liberty was a loosely organized, clandestine, sometimes violent, political organization active in the Thirteen American Colonies founded to advance the rights of the colonists and to fight taxation by the British government. It pl ...

"major general" William A. Bowles, to inquire if Bowles could offer any support for Morgan's upcoming raid. Bowles claimed he could raise a force of 10,000, but before the deal was finalized, Hines was informed that a Union force was approaching and fled the state. As a result, Bowles provided no support for Morgan's raiders, which caused Morgan to harshly treat anyone in Indiana who claimed to be sympathetic to the Confederacy.

Large-scale support for the Confederacy among Golden Circle members and Southern Hoosiers in general declined after Morgan's Confederate raiders ransacked many homes bearing the banners of the Golden Circle, despite their proclaimed support for the Confederates. As Confederate Colonel Basil W. Duke

Basil Wilson Duke (May 28, 1838 – September 16, 1916) was a Confederate States Army, Confederate general officer during the American Civil War. His most noted service in the war was as second-in-command for his brother-in-law John Hunt Mo ...

recalled after the incident, "The Copperheads and Vallandighammers fought harder than the others" against Morgan's raiders. When Hoosiers failed to support Morgan's men in significant numbers, Governor Morton slowed his crackdown on Confederate sympathizers, theorizing that because they had failed to come to Morgan's aid in large numbers, they would similarly fail to aid a larger invasion.

Although raids into Indiana were infrequent, smuggling goods into Confederate territory was common, especially in the early days of the war when the Union army had not yet pushed the front lines far to the south of the Ohio River. New Albany and Jeffersonville, Indiana, were origination points for many Northern goods smuggled into the Confederacy. The ''Cincinnati Daily Gazette'' pressured both towns to stop trading with the South, especially with Louisville, because Kentucky's proclaimed neutrality was perceived as sympathetic to the South. A fraudulent steamboat company was established to ply the Ohio River between Madison, Indiana, and Louisville; its boat, the ''Masonic Gem'', made regular trips to Confederate ports.

Southern sympathizers

While it is believed that they were not particularly numerous, the exact number of Hoosiers to serve in Confederate armies is unknown. It is likely that most traveled to Kentucky to join Confederate regiments formed in that state. Former U.S. Army officer Francis A. Shoup, who briefly led the IndianapolisZouave

The Zouaves were a class of light infantry regiments of the French Army serving between 1830 and 1962 and linked to French North Africa; as well as some units of other countries modelled upon them. The zouaves were among the most decorated unit ...

militia unit, left for Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

prior to the war, and ultimately become a Confederate brigadier general.

Republican legislative majority

After the elections in 1864 the state's Republican legislative majority arrived at a critical turning point, as the North was slowly tightening itsblockade

A blockade is the act of actively preventing a country or region from receiving or sending out food, supplies, weapons, or communications, and sometimes people, by military force.

A blockade differs from an embargo or sanction, which are le ...

of the South. The new Republican-controlled legislature fully supported Morton's policies and worked to meet the state's commitments to the war effort. In 1865 the Indiana General Assembly validated the loans Morton had secured to run the state government, assumed them as state debt, and commended Morton for his actions during the interim.

Aftermath

News of Confederate General Robert E. Lee'ssurrender

Surrender may refer to:

* Surrender (law), the early relinquishment of a tenancy

* Surrender (military), the relinquishment of territory, combatants, facilities, or armaments to another power

Film and television

* ''Surrender'' (1927 film), an ...

at Appomattox Courthouse, Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

, reached Indianapolis at 11 p.m. on April 9, 1865, causing immediate and enthusiastic public celebrations that the ''Indianapolis Journal

The ''Indianapolis Journal'' was a newspaper published in Indianapolis, Indiana, during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The paper published daily editions every evening except on Sundays, when it published a morning edition.

The fir ...

'' characterized as "demented".Bodenhamer and Barrows, eds., p. 443. A week later, the community's excitement turned to sadness when news of Lincoln's assassination

On April 14, 1865, Abraham Lincoln, the 16th president of the United States, was Assassination, assassinated by well-known stage actor John Wilkes Booth, while attending the play ''Our American Cousin'' at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C.

S ...

arrived on April 15. Lincoln's funeral train passed through the capital city on April 30, and 100,000 people attended his bier

A bier is a stand on which a corpse, coffin, or casket containing a corpse is placed to lie in state or to be carried to the grave.''The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language'' (American Heritage Publishing Co., Inc., New York, ...

at the Indiana Statehouse

The Indiana Statehouse is the state capitol building of the U.S. state of Indiana. It houses the Indiana General Assembly, the office of the Governor of Indiana, the Indiana Supreme Court, and other state officials. The Statehouse is located in ...

.

Economic

The Civil War forever altered Indiana's economy. Despite hardships during the war, Indiana's economic situation improved. Farmers received higher prices for their agricultural products, railroads and commercial businesses thrived in the state's cities and towns, and manpower shortages gave laborers more bargaining power. The war also helped establish a national banking system to replace state-chartered banking institutions; by 1862 there were thirty-one national banks in the state. Wartime prosperity was particularly evident in Indianapolis, whose population more than doubled during the war, reaching 45,000 at the end of 1864. Increased wartime manufacturing and industrial growth in Hoosier cities and towns ushered in a new era of economic prosperity. By the end of the war, Indiana had become less rural that it previously had been. Overall, the war caused Indiana's industries to grow exponentially, although the state's southern counties experienced growth after the war at a slower rate than its other counties. The state's population shifted to central and northern Indiana as new industries and cities began to develop around theGreat Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes in the mid-east region of North America that connect to the Atlantic Ocean via the Saint Lawrence River. There are five lakes ...

and the railroad depots erected during the war.Barnhart, pp. 221–23. In 1876 Colonel Eli Lilly

Eli Lilly (July 8, 1838 – June 6, 1898) was an American soldier, pharmacist, chemist, and businessman who founded the Eli Lilly and Company pharmaceutical corporation. Lilly enlisted in the Union Army during the American Civil War and ...

opened a new pharmaceutical laboratory in Indianapolis, founding what later became Eli Lilly and Company

Eli Lilly and Company is an American pharmaceutical company headquartered in Indianapolis, Indiana, with offices in 18 countries. Its products are sold in approximately 125 countries. The company was founded in 1876 by, and named after, Colonel ...

.Bodenhamer and Barrows, eds., p. 911. Indianapolis was also the wartime home of Richard Gatling

Richard Jordan Gatling (September 12, 1818 – February 26, 1903) was an American inventor best known for his invention of the Gatling gun, which is considered to be the first successful machine gun.

Life

Gatling was born in Hertford County, Nort ...

, inventor of the Gatling Gun