Italy–Spain Relations on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Italy–Spain relations are the

After 1557, the

After 1557, the

Italian submarines carried out a campaign against Republican ships, also targeting Mediterranean ports together with surface ships. The Italian ''

Italian submarines carried out a campaign against Republican ships, also targeting Mediterranean ports together with surface ships. The Italian ''

File:Ambasciata d'Italia a Madrid (Spagna) 01b.jpg, Embassy of Italy in Madrid

File:Consolat d'Itàlia a Barcelona - 01.jpg, Consulate-General of Italy in Barcelona

File:Embassy of Spain in Rome.JPG, Embassy of Spain in Rome

File:Torre Turati Mattioni.jpg, Building hosting the Consulate-General of Spain in Milan

Italian embassy in Madrid

{{DEFAULTSORT:Italy-Spain relations

interstate relations

International relations (IR, and also referred to as international studies, international politics, or international affairs) is an academic discipline. In a broader sense, the study of IR, in addition to multilateral relations, concerns al ...

between Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

and Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

. Both countries established diplomatic relations some time after the unification of Italy

The unification of Italy ( ), also known as the Risorgimento (; ), was the 19th century Political movement, political and social movement that in 1861 ended in the Proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, annexation of List of historic states of ...

in 1860.

Both nations are member states of the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are Geography of the European Union, located primarily in Europe. The u ...

(and both nations use the euro

The euro (currency symbol, symbol: euro sign, €; ISO 4217, currency code: EUR) is the official currency of 20 of the Member state of the European Union, member states of the European Union. This group of states is officially known as the ...

as currency) and are both members of the Council of Europe

The Council of Europe (CoE; , CdE) is an international organisation with the goal of upholding human rights, democracy and the Law in Europe, rule of law in Europe. Founded in 1949, it is Europe's oldest intergovernmental organisation, represe ...

, OECD

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD; , OCDE) is an international organization, intergovernmental organization with 38 member countries, founded in 1961 to stimulate economic progress and international trade, wor ...

, NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO ; , OTAN), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental Transnationalism, transnational military alliance of 32 Member states of NATO, member s ...

, Union for the Mediterranean

The Union for the Mediterranean (UfM; , ''Al-Ittiḥād min ajl al-Mutawasseṭ'') is an intergovernmental organization of 43 member states from Europe and the Mediterranean Basin: the 27 Member state of the European Union, EU member states (i ...

, and the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

.

History

Precedents

In 218 BC, theRomans

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of Roman civilization

*Epistle to the Romans, shortened to Romans, a letter w ...

, coming from ''Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

'', conquered the Iberian Peninsula, which later became the Roman province

The Roman provinces (, pl. ) were the administrative regions of Ancient Rome outside Roman Italy that were controlled by the Romans under the Roman Republic and later the Roman Empire. Each province was ruled by a Roman appointed as Roman g ...

of ''Hispania

Hispania was the Ancient Rome, Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula. Under the Roman Republic, Hispania was divided into two Roman province, provinces: Hispania Citerior and Hispania Ulterior. During the Principate, Hispania Ulterior was divide ...

''. The Romans introduced the Vulgar Latin

Vulgar Latin, also known as Colloquial, Popular, Spoken or Vernacular Latin, is the range of non-formal Register (sociolinguistics), registers of Latin spoken from the Crisis of the Roman Republic, Late Roman Republic onward. ''Vulgar Latin'' a ...

, the ancestor of the Romance languages

The Romance languages, also known as the Latin or Neo-Latin languages, are the languages that are Language family, directly descended from Vulgar Latin. They are the only extant subgroup of the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-E ...

, which are spoken in both current-day countries of Italy and Spain. As a result of the conquest, mining extractive processes in the southwest of the peninsula (which required a massive number of forced laborers, initially from Hispania and later also from the Gallic borderlands and other locations of the Mediterranean), increased by leaps and bounds, bringing the interaction of slaving and ecocide

Ecocide (from Greek 'home' and Latin 'to kill') is the destruction of the natural environment, environment by humans. Ecocide threatens all human populations that are dependent on natural resources for maintaining Ecosystem, ecosystems and ensu ...

, entailing far-reaching environmental outcome in terms of pollution records, unmatched in the Mediterranean region until the Industrial Revolution. Vis-à-vis the local aristocracies in Hispania, a long process consisting of the fusion of incoming Roman and Italic settlers and the romanized

In linguistics, romanization is the conversion of text from a different writing system to the Roman (Latin) script, or a system for doing so. Methods of romanization include transliteration, for representing written text, and transcription, ...

indigenous elites was chiefly completed by the 1st century CE. It had involved the granting of Roman citizenship to entire communities. Some of the members of the local aristocracies of the Baetica

Hispania Baetica, often abbreviated Baetica, was one of three Roman provinces created in Hispania (the Iberian Peninsula) in 27 BC. Baetica was bordered to the west by Lusitania, and to the northeast by Tarraconensis. Baetica remained one of ...

managed to insert themselves into the social and political structures of the High Roman Empire.

Rome's imperial authority over Hispania receded and was ultimately severed in the 5th century, during the Migration period

The Migration Period ( 300 to 600 AD), also known as the Barbarian Invasions, was a period in European history marked by large-scale migrations that saw the fall of the Western Roman Empire and subsequent settlement of its former territories ...

. The Rome-based Latin Church would go on to hold nonetheless substantial clout over Christian polities of the Peninsula for the rest of the Middle Ages.

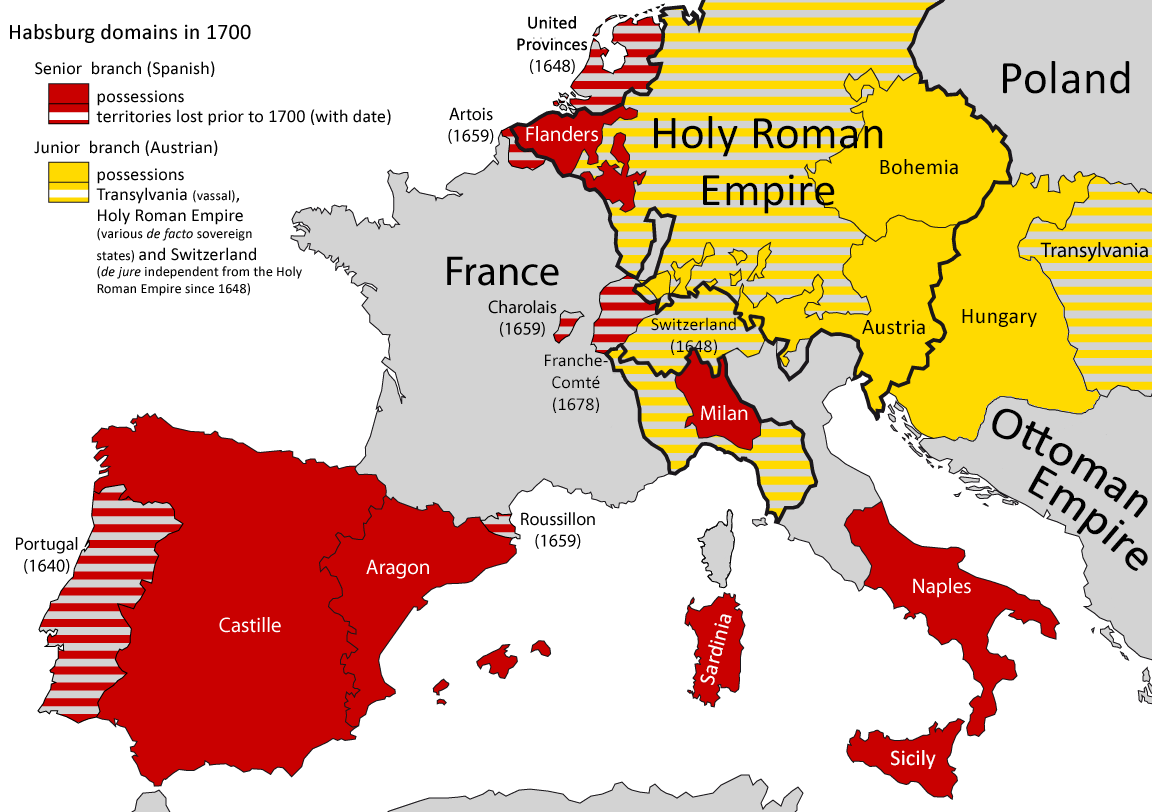

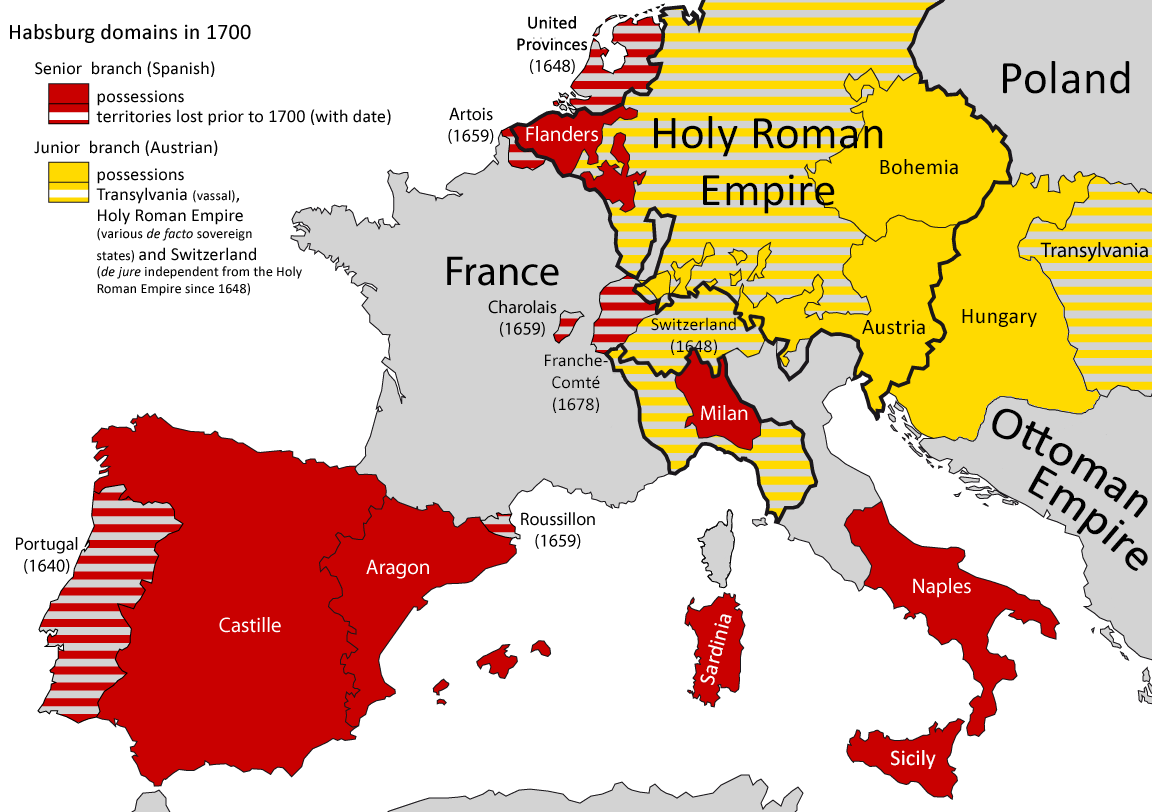

After 1557, the

After 1557, the Kingdom of Sicily

The Kingdom of Sicily (; ; ) was a state that existed in Sicily and the southern Italian peninsula, Italian Peninsula as well as, for a time, in Kingdom of Africa, Northern Africa, from its founding by Roger II of Sicily in 1130 until 1816. It was ...

, the Kingdom of Naples

The Kingdom of Naples (; ; ), officially the Kingdom of Sicily, was a state that ruled the part of the Italian Peninsula south of the Papal States between 1282 and 1816. It was established by the War of the Sicilian Vespers (1282–1302). Until ...

, and the Duchy of Milan

The Duchy of Milan (; ) was a state in Northern Italy, created in 1395 by Gian Galeazzo Visconti, then the lord of Milan, and a member of the important Visconti of Milan, Visconti family, which had been ruling the city since 1277. At that time, ...

under the Catholic Monarchy hitherto ruled by the Council of Aragon

The Council of Aragon, officially, the Royal and Supreme Council of Aragon (; ; ), was a ruling body and key part of the domestic government of the Spanish Empire in Europe, second only to the monarch himself. It administered the Crown of Arago ...

became ruled by the newly created Council of Italy

The Council of Italy, officially the Royal and Supreme Council of Italy (, ), was a ruling body and key part of the government of the Spanish Empire in Early Modern Europe, Europe, second only to the monarch himself. It was based in Madrid and ...

, as a cog of the polysynodial system

The Polysynodial System, Polysynodial Regime () or System of Councils was the way of organization of the composite monarchy ruled by the Catholic Monarchs and the Spanish Habsburgs, which entrusted the central administration in a group of collegia ...

underpinning the administration of the Habsburg empire

The Habsburg monarchy, also known as Habsburg Empire, or Habsburg Realm (), was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities (composite monarchy) that were ruled by the House of Habsburg. From the 18th century it is ...

, a composite monarchy. The Kingdom of Sardinia

The Kingdom of Sardinia, also referred to as the Kingdom of Sardinia and Corsica among other names, was a State (polity), country in Southern Europe from the late 13th until the mid-19th century, and from 1297 to 1768 for the Corsican part of ...

remained for the time being ruled by the Council of Aragon. The Council of Italy was dissolved for good in the wake of the Peace of Utrecht

The Peace of Utrecht was a series of peace treaty, peace treaties signed by the belligerents in the War of the Spanish Succession, in the Dutch city of Utrecht between April 1713 and February 1715. The war involved three contenders for the vac ...

.

Establishment of diplomatic relations

After the proclamation ofVictor Emmanuel II

Victor Emmanuel II (; full name: ''Vittorio Emanuele Maria Alberto Eugenio Ferdinando Tommaso di Savoia''; 14 March 1820 – 9 January 1878) was King of Sardinia (also informally known as Piedmont–Sardinia) from 23 March 1849 until 17 March ...

as King of Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

in 1861 Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

failed to initially recognise the country, still considering Victor Emmanuel as the "Sardinian King". The recognition was met by the opposition of Queen Isabella II of Spain

Isabella II (, María Isabel Luisa de Borbón y Borbón-Dos Sicilias; 10 October 1830 – 9 April 1904) was Queen of Spain from 1833 until her deposition in 1868. She is the only queen regnant in the history of unified Spain.

Isabella wa ...

, influenced by the stance of Pope Pius IX

Pope Pius IX (; born Giovanni Maria Battista Pietro Pellegrino Isidoro Mastai-Ferretti; 13 May 1792 – 7 February 1878) was head of the Catholic Church from 1846 to 1878. His reign of nearly 32 years is the longest verified of any pope in hist ...

. Once Leopoldo O'Donnell

Leopoldo O'Donnell y Jorris, 1st Duke of Tetuán, GE (12 January 1809 – 5 November 1867), was a Spanish general and Grandee who was Prime Minister of Spain on several occasions.

Early life

He was born at Santa Cruz de Tenerife in the Cana ...

overcame the opposition of the Queen, Spain finally recognised the Kingdom of Italy on 15 July 1865. Soon later, in 1870, following the dethronement of Isabella II at the 1868 Glorious Revolution, the second son of Victor Emmanuel II, Amadeo I

Amadeo I (; 30 May 184518 January 1890), also known as Amadeus, was an Italian prince who reigned as King of Spain from 1870 to 1873. The only king of Spain to come from the House of Savoy, he was the second son of Victor Emmanuel II of Italy an ...

, was elected King of Spain, reigning from 1871 until his abdication in 1873.

Situation after World War I

Despite some incipient attempts to promote further understanding between the two countries, immediately after the end ofWorld War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, there were still issues restraining further Italian-Spanish engagement in Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

. This includes a sector of public opinion showing aversion towards Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

; a prominent example being Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

-born Queen Mother Maria Christina.

Rapprochement between the Mediterranean dictatorships

Once dictatorsBenito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

(1922) and Miguel Primo de Rivera

Miguel Primo de Rivera y Orbaneja, 2nd Marquis of Estella, Grandee, GE (8 January 1870 – 16 March 1930), was a Spanish dictator and military officer who ruled as prime minister of Spain from 1923 to 1930 during the last years of the Resto ...

(1923) got to power, conditions for closer relations became more clear, with the notion of a rapprochement to Italy becoming more interesting to the Spanish Government policy, particularly in terms of the profit those improved relations could deliver to Spain vis-à-vis the Tangier question. For Italy, the installment of the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera

General Miguel Primo de Rivera's dictatorship over Spain began with a coup on 13 September 1923 and ended with his resignation on 28 January 1930. It took place during the wider reign of King Alfonso XIII. In establishing his dictatorship, ...

offered a prospect for greater ascendancy over a country with a government now widely interested in the reforms carried out in Fascist Italy

Fascist Italy () is a term which is used in historiography to describe the Kingdom of Italy between 1922 and 1943, when Benito Mussolini and the National Fascist Party controlled the country, transforming it into a totalitarian dictatorship. Th ...

. Relations during this period were often embedded in a diplomatic triangle between France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

, and Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

. While showing a will for friendship and rapprochement, the "Treaty for Conciliation and Arbitration" signed in August 1926 between the two countries delivered limited substance in practical terms, compared to the expectations at the starting point of the ''Primorriverista'' dictatorship.

A diplomatic "honeymoon" between the two regimes followed the signing of the treaty, nonetheless.

Conspirations against the Spanish Republic

The early monarchist conspirations against theSecond Spanish Republic

The Spanish Republic (), commonly known as the Second Spanish Republic (), was the form of democratic government in Spain from 1931 to 1939. The Republic was proclaimed on 14 April 1931 after the deposition of Alfonso XIII, King Alfonso XIII. ...

enjoyed support from Mussolini. One of the most important Italian communities in Spain resided in Catalonia

Catalonia is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a ''nationalities and regions of Spain, nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia of 2006, Statute of Autonomy. Most of its territory (except the Val d'Aran) is situate ...

as well as the Italian economic interests in Spain lied there, hence that region became a significant point of attention for the Italian diplomacy during the Spanish Second Republic, and the Italian diplomacy established some contacts with incipient filo-fascist elements within Republican Left of Catalonia

The Republican Left of Catalonia (, ERC; ; generically branded as ) is a pro-Catalan independence, social democratic political party in the Spanish autonomous community of Catalonia, with a presence also in Valencia, the Balearic Islands and t ...

, including Josep Dencàs, although Italy eventually went on to bet on Spanish fascism. Although both monarchists from Renovación Española, the traditionalists and the Fascist falangist

Falangism () was the political ideology of three political parties in Spain that were known as the Falange, namely first the Falange Española, the Falange Española de las Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional Sindicalista (FE de las JONS), and afterwa ...

s engaged in negotiations asking help from Fascist Italy regarding the preparations of the 1936 coup d'état, Mussolini decided not to take part at the time.

Italian intervention in the Spanish Civil War

After 18 July 1936 and the beginning of theSpanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War () was a military conflict fought from 1936 to 1939 between the Republican faction (Spanish Civil War), Republicans and the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalists. Republicans were loyal to the Left-wing p ...

, Mussolini changed the strategy and intervened on the side of the Rebel faction A rebel faction usually refers to a rebellious group.

Rebel faction may also refer to: Politics

* Nationalist faction during the Spanish Civil War

* Rebel Red Guards during the Cultural Revolution Fiction

* Rebel Alliance, a fictional organ ...

. The Corps of Volunteer Troops

The Corps of Volunteer Troops () was a Fascist Italian expeditionary force of military volunteers, which was sent to Spain to support the Nationalist forces under General Francisco Franco against the Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil ...

(CTV), a fascist expeditionary force from Italy, brought in about 78,000 Italian troops, sent to help Franco and vowing to establish a Fascist Spain and a Fascist Europe. In 1937, key military actions in which the CTV took part included the battles of Málaga

Málaga (; ) is a Municipalities in Spain, municipality of Spain, capital of the Province of Málaga, in the Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia. With a population of 591,637 in 2024, it is the second-most populo ...

, Bermeo, Santander and the fiasco of Guadalajara. Between 1938 and 1939, according to the historian Rodrigo Javier, "the Italians were crucial to the success of the Rebel army...in breaking through and stabilizing the Aragon front, in the occupation of Barcelona and Girona and in concluding the Levantine campaign".

Italian submarines carried out a campaign against Republican ships, also targeting Mediterranean ports together with surface ships. The Italian ''

Italian submarines carried out a campaign against Republican ships, also targeting Mediterranean ports together with surface ships. The Italian ''Regia Marina

The , ) (RM) or Royal Italian Navy was the navy of the Kingdom of Italy () from 1861 to 1946. In 1946, with the birth of the Italian Republic (''Repubblica Italiana''), the changed its name to '' Marina Militare'' ("Military Navy").

Origin ...

'' also provided key logistical support to the Rebels, including escort of commercial shipment transporting war supplies, and, seeking to facilitate the naval blockade on the Republic, it also allowed the Rebel Navy the use of anchorages in Sicily and Sardinia.

Italians forces in the Balearic Islands

The Balearic Islands are an archipelago in the western Mediterranean Sea, near the eastern coast of the Iberian Peninsula. The archipelago forms a Provinces of Spain, province and Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Spain, ...

established an air base of the Aviazione Legionaria

The Legionary Air Force (, ) was an expeditionary corps from the Italian Royal Air Force that was set up in 1936. It was sent to provide logistical and tactical support to the Nationalist faction after the Spanish coup of July 1936, which mar ...

in Mallorca, from which Italians were given permission by the rebel authorities to bomb locations across the Peninsular Levante controlled by the Republic (including the bombings of Barcelona investigated as crimes against humanity

Crimes against humanity are certain serious crimes committed as part of a large-scale attack against civilians. Unlike war crimes, crimes against humanity can be committed during both peace and war and against a state's own nationals as well as ...

). A Fascist ''squadristi'', Arconovaldo Bonaccorsi, led a wild repression in the Balearic islands.

World War II

During World War II, 1939 to 1943, Spanish-Italian ties were close. Though Italy fought alongside Germany during the war, Spain was recovering from a civil war and remained neutral. In February 1941, the meeting between Mussolini and Franco in Bordighera took place; during the meeting the ''Duce'' asked Franco to join theAxis

An axis (: axes) may refer to:

Mathematics

*A specific line (often a directed line) that plays an important role in some contexts. In particular:

** Coordinate axis of a coordinate system

*** ''x''-axis, ''y''-axis, ''z''-axis, common names ...

.

The fall of Mussolini came as a shock to the Franco administration. During the first few weeks the tightly-censored Spanish press limited themselves to laconic, matter-of-fact information when providing news on the Italian developments. However, after the Italian-American armistice had been made public, the Spanish papers extensively quoted the official German statement, which lambasted the Italian treason. Some Spanish officers sent their Italian military decorations back to the Italian embassy in Madrid.

Since mid-September 1943 two Italian states, the one headed by Mussolini and the one headed by king Victor Emmanuel III

Victor Emmanuel III (; 11 November 1869 – 28 December 1947) was King of Italy from 29 July 1900 until his abdication on 9 May 1946. A member of the House of Savoy, he also reigned as Emperor of Ethiopia from 1936 to 1941 and King of the Albani ...

, competed for Spanish diplomatic recognition; the German diplomatic representatives in Madrid pressed the case of Mussolini, the Allied ones advised strongly against it. Following a period of hesitation, in late September Spain declared it would continue its official relations with the Kingdom of Italy.

The Italian ambassador in Madrid Paulucci di Calboli opted for the Badoglio government, even though some Italian consuls in Spain declared loyalty to Mussolini. The Spanish ambassador in Fascist Italy, Raimundo Fernández-Cuesta

Raimundo Fernández-Cuesta y Merelo (5 October 1896, Madrid – 9 July 1992, Madrid) was a leading Spain, Spanish politician with both the Falangism, Falange and its successor movement the Spanish Traditionalist Phalanx of the Assemblies of N ...

, formally remained at the post of the Spanish representative in the Kingdom, though he returned to Madrid; in practice before the Badoglio administration Spain was represented by lower-rank officials. However, Spain maintained informal relations with the Repubblica Sociale Italiana. The former Italian consul in Málaga, Eugenio Morreale, became an unofficial Mussolini representative in Madrid; the Spanish consul in Milan, Fernando Chantel, became an unofficial Franco representative in RSI.

In practice, Spain maintained distance towards both the so-called ''Kingdom of the South

The Kingdom of the South ( Italian: ''Regno del Sud'') is a term which is used in historiography to describe the Kingdom of Italy (initially Pietro Badoglio and later Ivanoe Bonomi as prime ministers) under the control of the Allied Military G ...

'' and the RSI. Badoglio sought Madrid's good offices to expedite negotiations with the Allies, but he was turned down. Major Fascist figures who sought Spanish passports were almost always denied assistance. During the final months of the war new ambassadors were appointed by both Spain ( José Antonio de Sangróniz y Castro) and the Kingdom of Italy ( Tommaso Gallarati Scotti), though Sangróniz arrived no earlier than in May 1945.

Cold War

After World War II, the Francoist dictatorship provided financial support to post-fascist Italian partyItalian Social Movement

The Italian Social Movement (, MSI) was a neo-fascist political party in Italy. A far-right party, it presented itself until the 1990s as the defender of Italian fascism's legacy, and later moved towards national conservatism. In 1972, the Itali ...

(MSI), by means of a scheme set up by foreign minister Alberto Martín-Artajo. Starting in the 1960s, Franco also provided support to Ordine Nuovo

Ordine Nuovo (Italian language, Italian for "New Order", full name Centro Studi Ordine Nuovo, "New Order Scholarship Center") was an Italian far right cultural and extra-parliamentary political and paramilitary organization founded by Pino Rau ...

and National Vanguard, also lending sanctuary to putschist Junio Valerio Borghese

Junio Valerio Scipione Ghezzo Marcantonio Maria Borghese (6 June 1906 – 26 August 1974), nicknamed The Black Prince, was an Italian Navy commander during the regime of Benito Mussolini's National Fascist Party and a prominent hardline neo-fa ...

in 1970, with Spain henceforth serving as a den for some Italian far-right terrorists, who eventually played themselves a role in the so-called Spanish Transition

The Spanish transition to democracy, known in Spain as (; ) or (), is a period of History of Spain, modern Spanish history encompassing the regime change that moved from the Francoist dictatorship to the consolidation of a parliamentary system ...

.

21st century

Nowadays,Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

and Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

are full member countries of the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are Geography of the European Union, located primarily in Europe. The u ...

(EU), NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO ; , OTAN), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental Transnationalism, transnational military alliance of 32 Member states of NATO, member s ...

, and the Union for the Mediterranean

The Union for the Mediterranean (UfM; , ''Al-Ittiḥād min ajl al-Mutawasseṭ'') is an intergovernmental organization of 43 member states from Europe and the Mediterranean Basin: the 27 Member state of the European Union, EU member states (i ...

(UfM). Bilateral relations between the two countries are very close due to the historical ties that unite them and due to their membership in the EU. Meetings between governments and at the business level are frequent. All of this is reflected in economic exchanges marked by a very significant weight.

Diplomatic relations under the EU have been mired by underlying issues of common mistrust between both countries; cultural proximity and common challenges notwithstanding. They underwent a period of "freezing cold" during the simultaneous premierships of Mariano Rajoy

Mariano Rajoy Brey (, ; born 27 March 1955) is a Spanish politician who served as Prime Minister of Spain from 2011 to 2018, when a 2018 vote of no confidence in the government of Mariano Rajoy, vote of no confidence ousted his government. A m ...

and Matteo Renzi

Matteo Renzi (; born 11 January 1975) is an Italian politician who served as prime minister of Italy from 2014 to 2016. He has been a senator for Florence since 2018. Renzi has served as the leader of Italia Viva (IV) since 2019, having bee ...

, who did not get along on a personal level. Both governments outlined plans for the empowerment of a Madrid-Rome axis vis-à-vis EU negotiations of post COVID-19 reconstruction during the second cabinet of Italian prime minister Giuseppe Conte

Giuseppe Conte (; born 8 August 1964) is an Italian jurist, academic, and politician who served as Prime Minister of Italy, prime minister of Italy from June 2018 to February 2021. He has been the president of the Five Star Movement (M5S) sin ...

, with Pedro Sánchez

Pedro Sánchez Pérez-Castejón (; born 29 February 1972) is a Spanish politician who has served as Prime Minister of Spain since 2018. He has also been Secretary-General of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) since July 2017, having p ...

as his Spanish counterpart. The arrival of Mario Draghi

Mario Draghi (; born 3 September 1947) is an Italian politician, economist, academic, banker, statesman, and civil servant, who served as the prime minister of Italy from 13 February 2021 to 22 October 2022. Prior to his appointment as prime mi ...

to Italian premiership, however, further distanced the position between both countries, contrasting to the hitherto "relative alignment" cultivated by Conte.

In November 2021, Italian President Sergio Mattarella

Sergio Mattarella (; born 23 July 1941) is an Italian politician and jurist who has served as the president of Italy since 2015. He is the longest-serving president in the history of the Italian Republic. Since Giorgio Napolitano's death in 20 ...

made a state visit to Spain, and was received by King Felipe VI

Felipe VI (; Felipe Juan Pablo Alfonso de Todos los Santos de Borbón y Grecia; born 30 January 1968) is King of Spain. In accordance with the Spanish Constitution, as monarch, he is head of state and commander-in-chief of the Spanish Armed For ...

at the Royal Palace of Madrid

The Royal Palace of Madrid () is the official residence of the Spanish royal family at the city of Madrid, although now used only for state ceremonies.

The palace has of floor space and contains 3,418 rooms. It is the largest royal palace in Eu ...

.

In January 2022, Spain proposed to Italy the signing of a Friendship Treaty between the two countries. Spanish foreign minister Albares proposed to his Italian counterpart Di Maio the "relaunch" of the relationship between the parliaments of Spain and Italy and raised the prospect of creating an investment forum between companies from both countries pertaining to projects making use of EU funds. In November, the Italian Prime Minister, Giorgia Meloni

Giorgia Meloni (; born 15 January 1977) is an Italian politician who has served as Prime Minister of Italy since 2022. She is the first woman to hold the office. A member of the Chamber of Deputies (Italy), Chamber of Deputies since 2006, s ...

, stated that cooperation on energy, "real economy" and immigration will continue, strengthening bilateral relations within the common framework of the EU and NATO.

Cultural exchange

During theAge of Discovery

The Age of Discovery (), also known as the Age of Exploration, was part of the early modern period and overlapped with the Age of Sail. It was a period from approximately the 15th to the 17th century, during which Seamanship, seafarers fro ...

, famous Italian explorers and travelers were part of modern Spanish history. Examples include Amerigo Vespucci

Amerigo Vespucci ( , ; 9 March 1454 – 22 February 1512) was an Italians, Italian explorer and navigator from the Republic of Florence for whom "Naming of the Americas, America" is named.

Vespucci participated in at least two voyages of the A ...

, Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus (; between 25 August and 31 October 1451 – 20 May 1506) was an Italians, Italian explorer and navigator from the Republic of Genoa who completed Voyages of Christopher Columbus, four Spanish-based voyages across the At ...

and Francesco Guicciardini

Francesco Guicciardini (; 6 March 1483 – 22 May 1540) was an Italian historian and politician, statesman. A friend and critic of Niccolò Machiavelli, he is considered one of the major political writers of the Italian Renaissance. In his maste ...

.

Diaspora

AEurostat

Eurostat ("European Statistical Office"; also DG ESTAT) is a department of the European Commission ( Directorate-General), located in the Kirchberg quarter of Luxembourg City, Luxembourg. Eurostat's main responsibilities are to provide statist ...

publication in 2016 estimated that 187,847 Italian citizens live in Spain and 19,094 Spanish citizens live in Italy.

Resident diplomatic missions

* Italy has an embassy inMadrid

Madrid ( ; ) is the capital and List of largest cities in Spain, most populous municipality of Spain. It has almost 3.5 million inhabitants and a Madrid metropolitan area, metropolitan area population of approximately 7 million. It i ...

and a consulate-general in Barcelona

Barcelona ( ; ; ) is a city on the northeastern coast of Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second-most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within c ...

.

* Spain has an embassy in Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

and consulate-generals in Milan

Milan ( , , ; ) is a city in northern Italy, regional capital of Lombardy, the largest city in Italy by urban area and the List of cities in Italy, second-most-populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of nea ...

and Naples

Naples ( ; ; ) is the Regions of Italy, regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 908,082 within the city's administrative limits as of 2025, while its Metropolitan City of N ...

.

See also

*Spanish–Italian Amphibious Battlegroup

The Spanish–Italian Amphibious Battlegroup is one of 18 European Union battlegroups.

It is formed by the Spanish–Italian Landing Force (''SILF'') of the Spanish–Italian Amphibious Force (''SIAF'' ; ). It consists of 1500 Marines with manpow ...

References

Bibliography

* * Albanese, Matteo, and Pablo Del Hierro. ''Transnational fascism in the twentieth century: Spain, Italy and the global neo-fascist network'' (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2016). * * Dandelet, Thomas, and John Marino, eds. ''Spain in Italy: Politics, Society, and Religion 1500-1700'' (Brill, 2006). * * * * * * * * *External links

Italian embassy in Madrid

{{DEFAULTSORT:Italy-Spain relations

Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

Bilateral relations of Spain