An institutional referendum (, or ) was held by

universal suffrage

Universal suffrage or universal franchise ensures the right to vote for as many people bound by a government's laws as possible, as supported by the " one person, one vote" principle. For many, the term universal suffrage assumes the exclusion ...

in the

Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy (, ) was a unitary state that existed from 17 March 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 10 June 1946, when the monarchy wa ...

on 2 June 1946, a key event of

contemporary Italian history. Until 1946,

Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

was a kingdom ruled by the

House of Savoy

The House of Savoy (, ) is a royal house (formally a dynasty) of Franco-Italian origin that was established in 1003 in the historical region of Savoy, which was originally part of the Kingdom of Burgundy and now lies mostly within southeastern F ...

, reigning since the

unification of Italy

The unification of Italy ( ), also known as the Risorgimento (; ), was the 19th century Political movement, political and social movement that in 1861 ended in the Proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, annexation of List of historic states of ...

in 1861 and previously rulers of the

Kingdom of Sardinia

The Kingdom of Sardinia, also referred to as the Kingdom of Sardinia and Corsica among other names, was a State (polity), country in Southern Europe from the late 13th until the mid-19th century, and from 1297 to 1768 for the Corsican part of ...

. In 1922, the rise of

Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

and the creation of the

Fascist regime in Italy, which eventually resulted in engaging the country in

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

alongside

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

, considerably weakened the role of the royal house.

Following the

Italian Civil War and the

Liberation of Italy from

Axis

An axis (: axes) may refer to:

Mathematics

*A specific line (often a directed line) that plays an important role in some contexts. In particular:

** Coordinate axis of a coordinate system

*** ''x''-axis, ''y''-axis, ''z''-axis, common names ...

troops in 1945, a popular referendum on the institutional form of the state was called the next year and resulted in voters choosing the replacement of the

monarchy

A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, reigns as head of state for the rest of their life, or until abdication. The extent of the authority of the monarch may vary from restricted and largely symbolic (constitutio ...

with a

republic

A republic, based on the Latin phrase ''res publica'' ('public affair' or 'people's affair'), is a State (polity), state in which Power (social and political), political power rests with the public (people), typically through their Representat ...

. The

1946 Italian general election to elect the

Constituent Assembly of Italy was held on the same day. As with the simultaneous Constituent Assembly elections, the referendum was not held in the

Julian March, in the

province of Zara or the

province of Bolzano, which were still under occupation by

Allied forces pending a final settlement of the status of the territories.

The results were proclaimed by the

Supreme Court of Cassation on 10 June 1946: 12,717,923 citizens in favor of the republic and 10,719,284 citizens in favor of the monarchy.

[Gazzetta Ufficiale n. 134 del 20 giugno 1946]

/ref> The event is commemorated annually by the ''Festa della Repubblica

''Festa della Repubblica'' (; English: ''Republic Day'') is the Italian National Day and Republic Day, which is celebrated on 2 June each year, with the main celebration taking place in Rome. The ''Festa della Repubblica'' is one of the nationa ...

''. The former King Umberto II voluntarily left the country on 13 June 1946, headed for Cascais

Cascais () is a town and municipality in the Lisbon District of Portugal, located on the Portuguese Riviera, Estoril Coast. The municipality has a total of 214,158 inhabitants in an area of 97.40 km2. Cascais is an important tourism in Port ...

, in southern Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, is a country on the Iberian Peninsula in Southwestern Europe. Featuring Cabo da Roca, the westernmost point in continental Europe, Portugal borders Spain to its north and east, with which it share ...

, without even waiting for the results to be defined and the ruling on the appeals presented by the monarchist party, which were rejected by the Supreme Court of Cassation on 18 June 1946. With the entry into force of the new Constitution of the Italian Republic, on 1 January 1948, Enrico De Nicola became the first to assume the functions of president of Italy

The president of Italy, officially titled President of the Italian Republic (), is the head of state of Italy. In that role, the president represents national unity and guarantees that Politics of Italy, Italian politics comply with the Consti ...

. It marked the first time that most of the Italian Peninsula was under a single republican government since the fall of the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( ) was the era of Ancient Rome, classical Roman civilisation beginning with Overthrow of the Roman monarchy, the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom (traditionally dated to 509 BC) and ending in 27 BC with the establis ...

.

Background

Republican ideas and the unification of Italy

In the

In the history of Italy

Italy has been inhabited by humans Prehistoric Italy, since the Paleolithic. During antiquity, there were many ancient peoples of Italy, peoples in the Italian peninsula, including Etruscan civilization, Etruscans, Latins, Samnites, Umbri, Cisal ...

there are several so-called "republican" governments that have followed one another over time. Examples are the ancient Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( ) was the era of Ancient Rome, classical Roman civilisation beginning with Overthrow of the Roman monarchy, the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom (traditionally dated to 509 BC) and ending in 27 BC with the establis ...

and the medieval maritime republics

The maritime republics (), also called merchant republics (), were Italian Thalassocracy , thalassocratic Port city, port cities which, starting from the Middle Ages, enjoyed political autonomy and economic prosperity brought about by their mar ...

. From Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, orator, writer and Academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises tha ...

to Niccolò Machiavelli

Niccolò di Bernardo dei Machiavelli (3 May 1469 – 21 June 1527) was a Florentine diplomat, author, philosopher, and historian who lived during the Italian Renaissance. He is best known for his political treatise '' The Prince'' (), writte ...

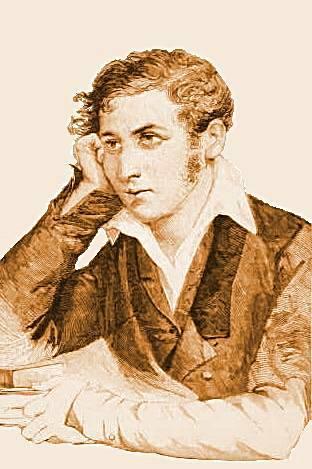

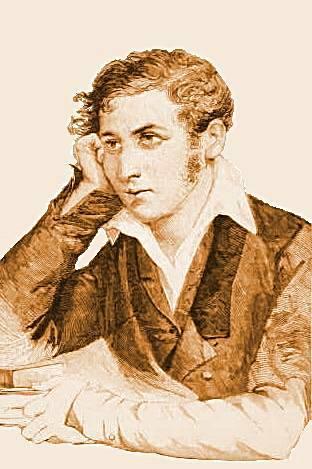

, Italian philosophers have imagined the foundations of political science and republicanism. But it was Giuseppe Mazzini

Giuseppe Mazzini (, ; ; 22 June 1805 – 10 March 1872) was an Italian politician, journalist, and activist for the unification of Italy (Risorgimento) and spearhead of the Italian revolutionary movement. His efforts helped bring about the ...

who revived the republican idea in Italy in the 19th century.

An Italian nationalist in the historical radical tradition and a proponent of a republicanism of social-democratic inspiration, Mazzini helped define the modern European movement for popular democracy

Popular democracy is a notion of direct democracy based on referendums and other devices of empowerment and concretization of popular will. The concept evolved out of the political philosophy of populism, as a fully democratic version of this p ...

in a republican state.[Swinburne, Algernon Charles (2013). ]

Delphi Complete Works of Algernon Charles Swinburne

'. Delphi Classics. . Mazzini's thoughts had a very considerable influence on the Italian and European republican movements, in the Constitution of Italy

The Constitution of the Italian Republic () was ratified on 22 December 1947 by the Constituent Assembly of Italy, Constituent Assembly, with 453 votes in favour and 62 against, before coming into force on 1 January 1948, one century after the p ...

, about Europeanism and more nuanced on many politicians of a later period, among them American president Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

, British prime minister David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. A Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, he was known for leadi ...

, Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (2October 186930January 1948) was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist, and political ethics, political ethicist who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful Indian ...

, Israeli prime minister Golda Meir

Golda Meir (; 3 May 1898 – 8 December 1978) was the prime minister of Israel, serving from 1969 to 1974. She was Israel's first and only female head of government.

Born into a Jewish family in Kyiv, Kiev, Russian Empire (present-day Ukraine) ...

and Indian prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru

Jawaharlal Nehru (14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat, and statesman who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20th century. Nehru was a pr ...

.[King, Bolton (2019). ]

The Life of Mazzini

'. Good Press. Mazzini formulated a concept known as "thought and action" in which thought and action must be joined together and every thought must be followed by action, therefore rejecting intellectualism

Intellectualism is the mental perspective that emphasizes the use, development, and exercise of the intellect, and is identified with the life of the mind of the intellectual. (Definition) In the field of philosophy, the term ''intellectualism'' in ...

and the notion of divorcing theory from practice.[Schumaker, Paul (2010). ''The Political Theory Reader'' (illustrated ed.). Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 58. .]

In July 1831, in exile in Marseille

Marseille (; ; see #Name, below) is a city in southern France, the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Bouches-du-Rhône and of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur Regions of France, region. Situated in the ...

, Giuseppe Mazzini founded the Young Italy movement, which aimed to transform Italy into a unitary democratic republic, according to the principles of freedom, independence and unity, but also to oust the monarchic regimes pre-existing the unification, including the Kingdom of Sardinia

The Kingdom of Sardinia, also referred to as the Kingdom of Sardinia and Corsica among other names, was a State (polity), country in Southern Europe from the late 13th until the mid-19th century, and from 1297 to 1768 for the Corsican part of ...

. The foundation of the Young Italy constitutes a key moment of the Italian Risorgimento

The unification of Italy ( ), also known as the Risorgimento (; ), was the 19th century political and social movement that in 1861 ended in the annexation of various states of the Italian peninsula and its outlying isles to the Kingdom of ...

and this republican program precedes in time the proposals for the unification of Italy of Vincenzo Gioberti and Cesare Balbo, aimed at reunifying the Italian territory under the presidency of the Pope

The pope is the bishop of Rome and the Head of the Church#Catholic Church, visible head of the worldwide Catholic Church. He is also known as the supreme pontiff, Roman pontiff, or sovereign pontiff. From the 8th century until 1870, the po ...

. Subsequently, the philosopher Carlo Cattaneo promoted a secular and republican Italy in the extension of Mazzini's ideas, but organized as a federal republic.

The political projects of Mazzini and Cattaneo were thwarted by the action of the Piedmontese Prime Minister

The political projects of Mazzini and Cattaneo were thwarted by the action of the Piedmontese Prime Minister Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour

Camillo Paolo Filippo Giulio Benso, Count of Cavour, Isolabella and Leri (; 10 August 1810 – 6 June 1861), generally known as the Count of Cavour ( ; ) or simply Cavour, was an Italian politician, statesman, businessman, economist, and no ...

, and Giuseppe Garibaldi

Giuseppe Maria Garibaldi ( , ;In his native Ligurian language, he is known as (). In his particular Niçard dialect of Ligurian, he was known as () or (). 4 July 1807 – 2 June 1882) was an Italian general, revolutionary and republican. H ...

. The latter set aside his republican ideas to favor Italian unity. After having obtained the conquest of the whole of southern Italy

Southern Italy (, , or , ; ; ), also known as () or (; ; ; ), is a macroregion of Italy consisting of its southern Regions of Italy, regions.

The term "" today mostly refers to the regions that are associated with the people, lands or cultu ...

during the Expedition of the Thousand

The Expedition of the Thousand () was an event of the unification of Italy that took place in 1860. A corps of volunteers led by Giuseppe Garibaldi sailed from Quarto al Mare near Genoa and landed in Marsala, Sicily, in order to conquer the Ki ...

, Garibaldi handed over the conquered territories to the king of Sardinia Victor Emmanuel II, which were annexed to the Kingdom of Sardinia after a plebiscite. This earned him heavy criticism from numerous republicans who accused him of treason. While a laborious administrative unification began, a first Italian parliament was elected and, on 17 March 1861, Victor Emmanuel II was proclaimed king of Italy.

From 1861 to 1946, Italy was a constitutional monarchy founded on the Albertine Statute, named after the king who promulgated it in 1848, Charles Albert of Sardinia. The parliament included a Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

, whose members were appointed by the king, and a Chamber of Deputies

The chamber of deputies is the lower house in many bicameral legislatures and the sole house in some unicameral legislatures.

Description

Historically, French Chamber of Deputies was the lower house of the French Parliament during the Bourb ...

, elected by census vote. In 1861 only 2% of Italians had the right to vote. In the political panorama of the time there was a republican political movement which had its martyrs, such as the soldier Pietro Barsanti. Barsanti was a supporter of republican ideas, and was a soldier in the Royal Italian Army with the rank of corporal. He was sentenced to death and shot in 1870 for having favored an insurrectional attempt against the Savoy monarchy and is therefore considered the first martyr of the modern Italian Republic

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

and a symbol of republican ideals in Italy.

Albertine Statute and liberal Italy

The balance of power between the Chamber and Senate initially shifted in favor of the Senate, composed mainly of nobles and industrial figures. Little by little, the Chamber of Deputies took on more and more importance with the evolution of the bourgeoisie and the large landowners, concerned with economic progress, but supporters of order and a certain

The balance of power between the Chamber and Senate initially shifted in favor of the Senate, composed mainly of nobles and industrial figures. Little by little, the Chamber of Deputies took on more and more importance with the evolution of the bourgeoisie and the large landowners, concerned with economic progress, but supporters of order and a certain social conservatism

Social conservatism is a political philosophy and a variety of conservatism which places emphasis on Tradition#In political and religious discourse, traditional social structures over Cultural pluralism, social pluralism. Social conservatives ...

.

The Republicans took part in the elections to the Italian Parliament, and in 1853 they formed the Action Party around Giuseppe Mazzini

Giuseppe Mazzini (, ; ; 22 June 1805 – 10 March 1872) was an Italian politician, journalist, and activist for the unification of Italy (Risorgimento) and spearhead of the Italian revolutionary movement. His efforts helped bring about the ...

. Although in exile, Mazzini was elected in 1866, but refused to take his seat in parliament. Carlo Cattaneo was elected deputy in 1860 and 1867, but refused so as not to have to swear loyalty to the House of Savoy

The House of Savoy (, ) is a royal house (formally a dynasty) of Franco-Italian origin that was established in 1003 in the historical region of Savoy, which was originally part of the Kingdom of Burgundy and now lies mostly within southeastern F ...

. The problem of the oath of loyalty to the monarchy, necessary to be elected, was the subject of controversy within the republican forces. In 1873 Felice Cavallotti, one of the most committed Italian politicians against the monarchy, preceded his oath with a declaration in which he reaffirmed his republican beliefs. In 1882, a new electoral law lowered the census limit for voting rights, increasing the number of voters to over two million, equal to 7% of the population. In the same year the Italian Workers' Party was created, which in 1895 became the Italian Socialist Party

The Italian Socialist Party (, PSI) was a Social democracy, social democratic and Democratic socialism, democratic socialist political party in Italy, whose history stretched for longer than a century, making it one of the longest-living parti ...

. In 1895 the intransigent republicans agreed to participate in the political life of the Kingdom, establishing the Italian Republican Party. Two years later, the far left reached its historical maximum level in Parliament with 81 deputies, for the three radical-democratic, socialist components and Republican. With the death of Felice Cavallotti in 1898, the radical left gave up on posing the institutional problem.

In Italian politics, the socialist party progressively divided into two tendencies: a maximalist one, led among others by Arturo Labriola and Enrico Ferri, and supporting the use of strikes; the other, reformist and pro-government, was led by Filippo Turati

Filippo Turati (; 26 November 1857 – 29 March 1932) was an Italian sociologist, criminologist, poet and socialist politician.

Early life

Born in Canzo, province of Como, he graduated in law at the University of Bologna in 1877, and particip ...

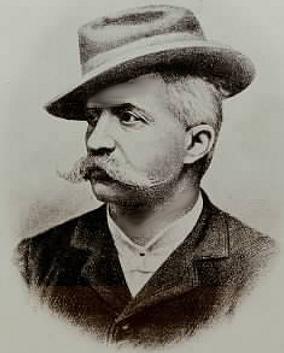

. A nationalist movement emerged, led in particular by Enrico Corradini

Enrico Corradini (20 July 1865 – 10 December 1931) was an Italian novelist, essayist, journalist and nationalist political figure.

Biography

Corradini was born near Montelupo Fiorentino, Tuscany.

A follower of Gabriele D'Annunzio, he founde ...

, as well as a Catholic social and democratic movement, the National Democratic League, led by Romolo Murri. In 1904, Pope Pius X

Pope Pius X (; born Giuseppe Melchiorre Sarto; 2 June 1835 – 20 August 1914) was head of the Catholic Church from 4 August 1903 to his death in August 1914. Pius X is known for vigorously opposing Modernism in the Catholic Church, modern ...

authorized Catholics to participate individually in political life, but in 1909 he condemned the National Democratic League created by Romolo Murri, who was excommunicated. Finally, a law of 3 June 1912 marked Italy's evolution towards a certain political liberalism by establishing universal male suffrage. In 1914, at the outbreak of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, Italy began to be counted among the world's liberal democracies.

Fascism

After World War I, Italian political life was animated by four great movements. Two of these movements were in favor of democratic development within the framework of existing monarchical institutions: the reformist socialists and the Italian People's Party. Two other movements challenged these institutions: the Republican Party on the one hand, and the maximalist socialists. In the 1919 elections, the parties most imbued with republican ideology (the maximalist socialists and the Republican Party) won, obtaining 165 out of 508 seats in the Chamber of Deputies. In the 1921 elections, after the foundation of the Italian Communist Party, the three parties republican, maximalist socialist and communist obtained 145 deputies out of 535. Overall, at the beginning of the interwar period, less than 30% of those elected were in favor of the establishment of a republican regime. In this context, the rise of Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

's fascist movement was based on the bitterness generated by the "mutilated victory

Mutilated victory () is a term coined by Gabriele D'Annunzio at the end of World War I, used by a part of Italian nationalists to denounce the partial infringement (and request the full application) of the 1915 pact of London concerning territori ...

", the fear of social unrest and the rejection of revolutionary, republican and Marxist ideology. The liberal political system and part of the aristocracy chose to erect fascism as a bulwark against, in their way of seeing, these dangers.

In October 1922, the nomination of Benito Mussolini as prime minister by King Victor Emmanuel III

Victor Emmanuel III (; 11 November 1869 – 28 December 1947) was King of Italy from 29 July 1900 until his abdication on 9 May 1946. A member of the House of Savoy, he also reigned as Emperor of Ethiopia from 1936 to 1941 and King of the Albani ...

, following the march on Rome

The March on Rome () was an organized mass demonstration in October 1922 which resulted in Benito Mussolini's National Fascist Party (, PNF) ascending to power in the Kingdom of Italy. In late October 1922, Fascist Party leaders planned a march ...

, paved the way for the establishment of the dictatorship. The Albertine Statute was progressively emptied of its content. Parliament was subject to the will of the new government. The legal opposition disintegrated. On 27 June 1924, 127 deputies left Parliament and retreated to the Aventine Hill, a clumsy maneuver which, in effect, left the field open to the fascists. They then had the fate of Italy in their hands for two decades.

Not only did Victor Emmanuel III appeal to Mussolini to form the government in 1922 and allow him to proceed with the domestication of Parliament, but he did not even draw the consequences of the assassination of Giacomo Matteotti in 1924. He accepted the title of emperor in 1936 at the end of Second Italo-Ethiopian War

The Second Italo-Ethiopian War, also referred to as the Second Italo-Abyssinian War, was a war of aggression waged by Fascist Italy, Italy against Ethiopian Empire, Ethiopia, which lasted from October 1935 to February 1937. In Ethiopia it is oft ...

, then the alliance with Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

and Italy's entry into World War II on 10 June 1940.

Anti-fascist parties in Italy and abroad

With the implementation of fascist laws (Royal Decree of 6 November 1926), all political parties operating on Italian territory were dissolved, with the exception of the

With the implementation of fascist laws (Royal Decree of 6 November 1926), all political parties operating on Italian territory were dissolved, with the exception of the National Fascist Party

The National Fascist Party (, PNF) was a political party in Italy, created by Benito Mussolini as the political expression of Italian fascism and as a reorganisation of the previous Italian Fasces of Combat. The party ruled the Kingdom of It ...

. Some of these parties expatriated and reconstituted themselves abroad, especially in France. Thus an anti-fascist coalition was formed on 29 March 1927 in Paris, the " Concentrazione Antifascista Italiana", which brought together the Italian Republican Party, the Italian Socialist Party

The Italian Socialist Party (, PSI) was a Social democracy, social democratic and Democratic socialism, democratic socialist political party in Italy, whose history stretched for longer than a century, making it one of the longest-living parti ...

, the Socialist Unitary Party of Italian Workers, the Italian League for Human Rights and the foreign representation of the Italian General Confederation of Labour. Some movements remained outside, including the Italian Communist Party

The Italian Communist Party (, PCI) was a communist and democratic socialist political party in Italy. It was established in Livorno as the Communist Party of Italy (, PCd'I) on 21 January 1921, when it seceded from the Italian Socialist Part ...

, the popular Catholic movement and other liberal movements. This coalition dissolved on 5 May 1934 and, in August of the same year, the pact of unity of action was signed between the Italian Socialist Party and the Italian Communist Party.Christian Democracy

Christian democracy is an ideology inspired by Christian social teaching to respond to the challenges of contemporary society and politics.

Christian democracy has drawn mainly from Catholic social teaching and neo-scholasticism, as well ...

. It brought together the veterans of Luigi Sturzo

Luigi Sturzo (; 26 November 1871 – 8 August 1959) was an Italian Catholic priest and prominent politician. He was known in his lifetime as a former Christian socialist turned Popolarismo, popularist, and is considered one of the fathers of th ...

's Italian People's Party and the young people of Catholic associations, in particular of the University Federation.

Institutional crisis

On 10 July 1943, the Allies landed in Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

in Operation Husky

Operation or Operations may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media

* ''Operation'' (game), a battery-operated board game that challenges dexterity

* Operation (music), a term used in musical set theory

* ''Operations'' (magazine), Multi-Man ...

. On 25 July 1943, Victor Emmanuel III revoked Mussolini's mandate as prime minister and had him arrested, entrusting the government to Marshal Pietro Badoglio

Pietro Badoglio, 1st Duke of Addis Abeba, 1st Marquess of Sabotino ( , ; 28 September 1871 – 1 November 1956), was an Italian general during both World Wars and the first viceroy of Italian East Africa. With the fall of the Fascist regim ...

. The new government contacted the Allies to reach an armistice. When the Armistice of Cassibile was announced on 8 September 1943, the Germans reacted by placing under their control all the part of Italian territory that still escaped the Allied advance and by disarming the Italian Royal Army. Victor Emmanuel III and Badoglio's government fled Rome and reached Brindisi

Brindisi ( ; ) is a city in the region of Apulia in southern Italy, the capital of the province of Brindisi, on the coast of the Adriatic Sea. Historically, the city has played an essential role in trade and culture due to its strategic position ...

, in southern Italy

Southern Italy (, , or , ; ; ), also known as () or (; ; ; ), is a macroregion of Italy consisting of its southern Regions of Italy, regions.

The term "" today mostly refers to the regions that are associated with the people, lands or cultu ...

. The war continued, but was also accompanied by the Italian Civil War, with the creation by Mussolini of the Italian Social Republic

The Italian Social Republic (, ; RSI; , ), known prior to December 1943 as the National Republican State of Italy (; SNRI), but more popularly known as the Republic of Salò (, ), was a List of World War II puppet states#Germany, German puppe ...

, heavily dependent on the Germans, and by the division of Italy into two antagonistic territories, one occupied by the allied forces, the other occupied by Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

. In these dramatic circumstances, in the two territories the civil administration gave way to a military and police administration. However, the parties that existed before fascism were reconstituted, alongside new political parties.

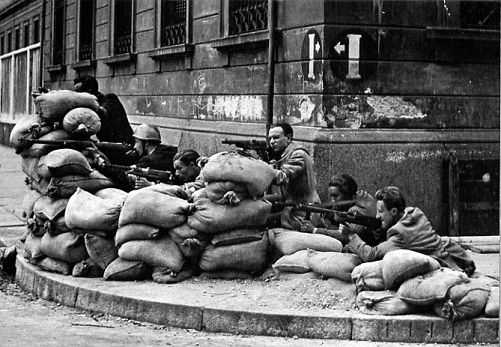

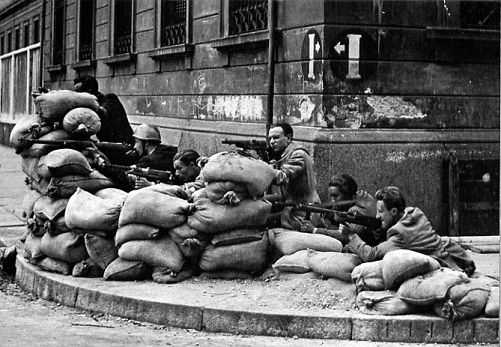

On 9 September 1943, in Rome (still occupied by the Germans), a National Liberation Committee (CLN) was created, which brought together the parties and movements opposed to fascism and German occupation. It was made up of representatives of the Italian Communist Party, members of the Action Party, Christian Democrats, liberals, socialists and progressive democrats. The National Liberation Committee gave priority to the fight against the Nazi-fascists, postponing the question of the institutional form of the Italian state until after the victory, but made the abdication of the king in favor of his son a prerequisite for the establishment of an anti-fascist government. The patriotic war of liberation led by the National Liberation Committee was also, for a significant part of its supporters, a war of social liberation, a war against a collaborationist elite. However, the Americans and English, anxious to prepare for the post-war period, facilitated the entry into German-occupied territory of Italian democratic and republican activists aimed at counterbalancing the communist influence in the leadership of the National Liberation Committee. This was the case, for example, of Leo Valiani, future member of the triumvirate responsible for the partisan insurrection in

On 9 September 1943, in Rome (still occupied by the Germans), a National Liberation Committee (CLN) was created, which brought together the parties and movements opposed to fascism and German occupation. It was made up of representatives of the Italian Communist Party, members of the Action Party, Christian Democrats, liberals, socialists and progressive democrats. The National Liberation Committee gave priority to the fight against the Nazi-fascists, postponing the question of the institutional form of the Italian state until after the victory, but made the abdication of the king in favor of his son a prerequisite for the establishment of an anti-fascist government. The patriotic war of liberation led by the National Liberation Committee was also, for a significant part of its supporters, a war of social liberation, a war against a collaborationist elite. However, the Americans and English, anxious to prepare for the post-war period, facilitated the entry into German-occupied territory of Italian democratic and republican activists aimed at counterbalancing the communist influence in the leadership of the National Liberation Committee. This was the case, for example, of Leo Valiani, future member of the triumvirate responsible for the partisan insurrection in Piedmont

Piedmont ( ; ; ) is one of the 20 regions of Italy, located in the northwest Italy, Northwest of the country. It borders the Liguria region to the south, the Lombardy and Emilia-Romagna regions to the east, and the Aosta Valley region to the ...

and Lombardy

The Lombardy Region (; ) is an administrative regions of Italy, region of Italy that covers ; it is located in northern Italy and has a population of about 10 million people, constituting more than one-sixth of Italy's population. Lombardy is ...

.

Institutional truce

On 31 March 1944, in Salerno

Salerno (, ; ; ) is an ancient city and ''comune'' (municipality) in Campania, southwestern Italy, and is the capital of the namesake province, being the second largest city in the region by number of inhabitants, after Naples. It is located ...

, Palmiro Togliatti, general secretary of the Italian Communist Party

The Italian Communist Party (, PCI) was a communist and democratic socialist political party in Italy. It was established in Livorno as the Communist Party of Italy (, PCd'I) on 21 January 1921, when it seceded from the Italian Socialist Part ...

, called for the formation of a government of national unity and no longer required the king's abdication as a prerequisite. This declaration pushed the parties of the National Liberation Committee to rally around a compromise drawn up by Enrico De Nicola, president of the Chamber of Deputies

The chamber of deputies is the lower house in many bicameral legislatures and the sole house in some unicameral legislatures.

Description

Historically, French Chamber of Deputies was the lower house of the French Parliament during the Bourb ...

until 1924, by Benedetto Croce

Benedetto Croce, ( , ; 25 February 1866 – 20 November 1952)

was an Italian idealist philosopher, historian, and politician who wrote on numerous topics, including philosophy, history, historiography, and aesthetics. A Cultural liberalism, poli ...

of the liberal party and by the king's entourage. As foreseen in this agreement, upon the liberation of Rome, on 4 June 1944, Victor Emmanuel III proclaimed his son Umberto lieutenant general of the kingdom, and the parties took political control of the nation, even if the war continued, stabilizing on the front on the Gothic line until April 1945.

From June 1944 to December 1945, three provisional coalition governments followed one another. The first was led by Ivanoe Bonomi

Ivanoe Bonomi (; 18 October 1873 – 20 April 1951) was an Italian politician and journalist who served as Prime Minister of Italy from 1921 to 1922 and again from 1944 to 1945.

Background and earlier career

Ivanoe Bonomi was born in Mant ...

, of the Labour Democratic Party. His government included the anti-fascist liberals Carlo Sforza

Count Carlo Sforza (24 January 1872 – 4 September 1952) was an Italian nobility, Italian nobleman, diplomat and Anti-fascism, anti-fascist politician.

Life and career

Sforza was born in Lucca, the second son of Count Giovanni Sforza (184 ...

and Benedetto Croce, as well as Palmiro Togliatti. Although temporarily put aside, the question of Italian institutions remained one of the main open political questions. Most of the forces supporting the National Liberation Committee were openly republicans and believed that the monarchy, in particular Victor Emmanuel III, had had a responsibility in the success of the fascist movement. The final agreement between the parties was to ask that at the end of the war, as soon as conditions were favourable, the calling of elections, an institutional referendum and the formation of a constituent assembly. Until then, on 31 January 1945, the Council of Ministers

Council of Ministers is a traditional name given to the supreme Executive (government), executive organ in some governments. It is usually equivalent to the term Cabinet (government), cabinet. The term Council of State is a similar name that also m ...

, chaired by Ivanoe Bonomi, issued a decree which recognized women's right to vote. Universal suffrage

Universal suffrage or universal franchise ensures the right to vote for as many people bound by a government's laws as possible, as supported by the " one person, one vote" principle. For many, the term universal suffrage assumes the exclusion ...

was thus recognized, after the vain attempts made in 1881 and 1907 by women of the various parties.

The Bonomi governments ( II then III) were succeeded by the Parri government in June 1945, then by the First De Gasperi government in December 1945. The question of the future form of the state, monarchy or republic, absorbed the minds of political circles. The majority of Christian Democratic

Christian democracy is an ideology inspired by Christian social teaching to respond to the challenges of contemporary society and politics.

Christian democracy has drawn mainly from Catholic social teaching and neo-scholasticism, as well ...

activists, especially young people, increasingly distanced themselves from the monarchy. During the local meetings of the leaders of this party, in Rome and Milan, motions were presented aimed at making official a political line favorable to a democratic republic. The central political office tried to curb these pressures and maintain an intermediate position.

Organization

On 16 March 1946, Prince Umberto decreed, as expected in 1944, that the question of the institutional form of the state would be decided by a referendum organized simultaneously with the election of a constituent assembly. The date was set for 2 June 1946. The Supreme Court of Cassation was responsible for examining the appeals. Its role was to be limited to observing the progress of voting operations and consolidating the bulletins issued by the offices that communicated the results in each constituency. The counting of the ballots of the candidates for the constituent assembly had to precede that of the referendum. If the monarchy had won, it would have been the Constituent Assembly

A constituent assembly (also known as a constitutional convention, constitutional congress, or constitutional assembly) is a body assembled for the purpose of drafting or revising a constitution. Members of a constituent assembly may be elected b ...

that would have had to choose the head of state.

Abdication and departure of King Victor Emmanuel III

Wanted by the Allies to verify that the conditions existed for voting in a country torn apart by the civil war only a few months earlier, partial municipal and provincial elections were held in March and April 1946 in half of the Italian municipalities and provinces. These elections, which mainly involved left-wing cities, brought out three parties, with a clear advantage for the Christian Democrats, led by Alcide De Gasperi, which exceeded the sum of votes cast for the Italian Communist Party

The Italian Communist Party (, PCI) was a communist and democratic socialist political party in Italy. It was established in Livorno as the Communist Party of Italy (, PCd'I) on 21 January 1921, when it seceded from the Italian Socialist Part ...

and the Italian Socialist Party

The Italian Socialist Party (, PSI) was a Social democracy, social democratic and Democratic socialism, democratic socialist political party in Italy, whose history stretched for longer than a century, making it one of the longest-living parti ...

. After these administrative elections, the monarchists, already worried about the outcome of the referendum, became even more discouraged.

But a political event changed the situation during the referendum campaign. A month before the referendum, Victor Emmanuel III

Victor Emmanuel III (; 11 November 1869 – 28 December 1947) was King of Italy from 29 July 1900 until his abdication on 9 May 1946. A member of the House of Savoy, he also reigned as Emperor of Ethiopia from 1936 to 1941 and King of the Albani ...

abdicated in favor of his son Umberto, who was proclaimed king and took the name Umberto II. The act of abdication, drawn up privately, is dated 9 May 1946. This abdication was desired by the monarchists, since the crown prince was less compromised than his father in Mussolini's rise to power and in coexistence with the fascist forces. It is also possible that the command of the allied forces present on Italian territory encouraged the sovereign to abdicate in favor of his son.

Results

The vote for the choice between monarchy or republic took place on 2 June and on the morning of 3 June 1946. After the transfer of the electoral cards from all of Italy and the minutes of the 31 constituencies to Rome, the results were expected on 8 June.

The vote for the choice between monarchy or republic took place on 2 June and on the morning of 3 June 1946. After the transfer of the electoral cards from all of Italy and the minutes of the 31 constituencies to Rome, the results were expected on 8 June.Naples

Naples ( ; ; ) is the Regions of Italy, regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 908,082 within the city's administrative limits as of 2025, while its Metropolitan City of N ...

, in Apulia

Apulia ( ), also known by its Italian language, Italian name Puglia (), is a Regions of Italy, region of Italy, located in the Southern Italy, southern peninsular section of the country, bordering the Adriatic Sea to the east, the Strait of Ot ...

, in Calabria

Calabria is a Regions of Italy, region in Southern Italy. It is a peninsula bordered by the region Basilicata to the north, the Ionian Sea to the east, the Strait of Messina to the southwest, which separates it from Sicily, and the Tyrrhenian S ...

and in Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

, the monarchists carried out protest demonstrations, sometimes violent.national personification

A national personification is an anthropomorphic personification of a state or the people(s) it inhabits. It may appear in political cartoons and propaganda. In the first personifications in the Western World, warrior deities or figures symboliz ...

of Italy, as their unitary symbol to be used in the electoral campaign and on the referendum ballot on the institutional form of the State, in contrast to the Savoy coat of arms, which represented the monarchy. This triggered various controversies, given that the iconography of the allegorical personification of Italy had, and still has, a universal and unifying meaning that should have been common to all Italians and not only to a part of them: this was the last appearance in the institutional context of ''Italia turrita''.

However, some voters were unable to vote. Before the closure of the electoral lists in April 1945, many Italian soldiers were still outside the national territory, in detention or internment camps abroad. Citizens of the provinces of Bolzano, Gorizia

Gorizia (; ; , ; ; ) is a town and (municipality) in northeastern Italy, in the autonomous region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia. It is located at the foot of the Julian Alps, bordering Slovenia. It is the capital of the Province of Gorizia, Region ...

, Trieste

Trieste ( , ; ) is a city and seaport in northeastern Italy. It is the capital and largest city of the Regions of Italy#Autonomous regions with special statute, autonomous region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia, as well as of the Province of Trieste, ...

, Pola, Fiume

Rijeka (;

Fiume ( �fjuːme in Italian and in Fiuman Venetian) is the principal seaport and the third-largest city in Croatia. It is located in Primorje-Gorski Kotar County on Kvarner Bay, an inlet of the Adriatic Sea and in 2021 had a po ...

and Zara, located in territories not administered by the Italian government but by the Allied authorities, which were still under occupation pending a final settlement of the status of the territories (in fact in 1947 most of these territories were then annexed by Yugoslavia after the Paris peace treaties of 1947, such as most of the Julian March and the province of Zara). These provinces, however, were all located in the north of the country, an area where the Republican vote obtained a fairly large majority.

By district

The conservative, rural '' Mezzogiorno'' (southern Italy) region voted solidly for the monarchy (63.8%) while the more urbanised and industrialised ''Nord'' (northern Italy) voted equally firmly for a republic (66.2%).

The conservative, rural '' Mezzogiorno'' (southern Italy) region voted solidly for the monarchy (63.8%) while the more urbanised and industrialised ''Nord'' (northern Italy) voted equally firmly for a republic (66.2%).

By most populated city

Provinces excluded from voting

The referendum was not held in the Julian March, in the province of Zara or the province of Bolzano, which were still under occupation by Allied forces pending a final settlement of the status of the territories.

Results of the Constituent Assembly elections

The distribution of votes is as follows:

Analysis of voting results

At first glance, the referendum seemed to simply divide Italy in two, between North and South, but the situation was more complex. For example, the districts located to the north of

At first glance, the referendum seemed to simply divide Italy in two, between North and South, but the situation was more complex. For example, the districts located to the north of Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

gave the majority to the republic, while those located to the south chose the monarchy. The electoral college of Rome was very divided and gave a slight majority to the choice of the monarchic regime. The Republican choice turned into a plebiscite, with over 80% of the votes cast in the electoral college of Bologna

Bologna ( , , ; ; ) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in northern Italy. It is the List of cities in Italy, seventh most populous city in Italy, with about 400,000 inhabitants and 150 different nationalities. Its M ...

, and even more in that of Trento

Trento ( or ; Ladin language, Ladin and ; ; ; ; ; ), also known in English as Trent, is a city on the Adige, Adige River in Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol in Italy. It is the capital of the Trentino, autonomous province of Trento. In the 16th ...

. In the South, however, the monarchist choice reached nearly 80% in the college of Naples. But, in other regions, the vote was very fragmented. There was not a total break with the past, but an interference between the two possible choices, which was expressed everywhere.

The occupation of the North by the German army and the period of the Italian Civil War, with the last gasps of the fascist movement, undoubtedly favored an increase in the importance of the socialist and communist parties in this region, which were republican in tendency. During these dark years, the populations concerned placed part of their hopes in dreams of revolution, or at least of change. The South, not having experienced this situation and having welcomed King Victor Emmanuel III and his government, was perhaps more wary of these parties and placed its trust in the monarchic regime, preferring continuity to the "leap into the unknown" represented by the republican form. Furthermore, the clientelism

Clientelism or client politics is the exchange of goods and services for political support, often involving an implicit or explicit ''quid-pro-quo''. It is closely related to patronage politics and vote buying.

Clientelism involves an asymmetri ...

prevalent in the South favored a vote that tended to be conservative, and therefore monarchist. Some analysts also cite the influence of the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

or the Catholic press.

Aftermath

First results and events in Naples

On 10 June, at 6 pm, in the Sala della Lupa ("Hall of the Wolf"), which owes its name to the presence of a bronze sculpture of the

On 10 June, at 6 pm, in the Sala della Lupa ("Hall of the Wolf"), which owes its name to the presence of a bronze sculpture of the Capitoline Wolf

The Capitoline Wolf (Italian language, Italian: ''Lupa Capitolina'') is a bronze sculpture depicting a scene from the legend of the founding of Rome. The sculpture shows a She-wolf (Roman mythology), she-wolf suckling the mythical twin founders ...

, of Palazzo Montecitorio in Rome, the Supreme Court of Cassation read out the partial results of the referendum, postponing the definitive proclamation of the results to Parliament for 18 June, after having taken the relevant decisions on appeals, protests and complaints. At the same time, republican demonstrations took place in many cities. The Milanese newspaper, , on Tuesday 11 June, ran the headline: "The Italian Republic is born". ''La Stampa

(English: "The Press") is an Italian daily newspaper published in Turin with an average circulation of 87,143 copies in May 2023. Distributed in Italy and other European nations, it is one of the oldest newspapers in Italy. Until the late 1970 ...

'', a Turin daily newspaper, declared more soberly: "The government confirms the victory of the republicans", and completed its coverage by asking: "the question is whether the republic has been proclaimed or not".

In Naples, a city with a population largely supportive of the monarchy, an incident occurred on 11 June. A procession of supporters of the monarchy advanced towards the municipal buildings and then changed objective and headed towards the headquarters of the Italian Communist Party

The Italian Communist Party (, PCI) was a communist and democratic socialist political party in Italy. It was established in Livorno as the Communist Party of Italy (, PCd'I) on 21 January 1921, when it seceded from the Italian Socialist Part ...

. The crowd saw a red flag, but also a tricolor flag from which the royal coat of arms had been cut. Despite the presence of armored vehicles, the demonstrators attempted to storm the communist party headquarters. Protesters and law enforcement officers exchange gunfire. According to the prefect's report, the demonstrators shot first. In any case the response was deadly, with machine gun fire. There were nine deaths among royalist demonstrators and a large number of injuries. Calm returned to the city only on 13 June.

The protests of the monarchists, like those bloodily repressed the day before in Naples and a new monarchist demonstration dispersed on 12 June, aroused the concerns of the ministers intending to establish the Republic as soon as possible (according to the famous phrase of the socialist leader Pietro Nenni: "either the Republic or chaos!").

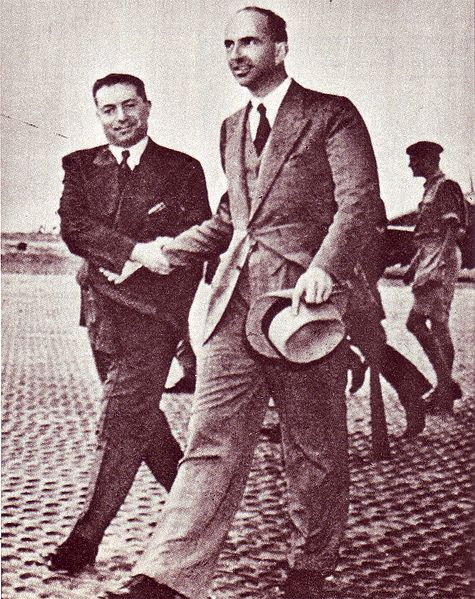

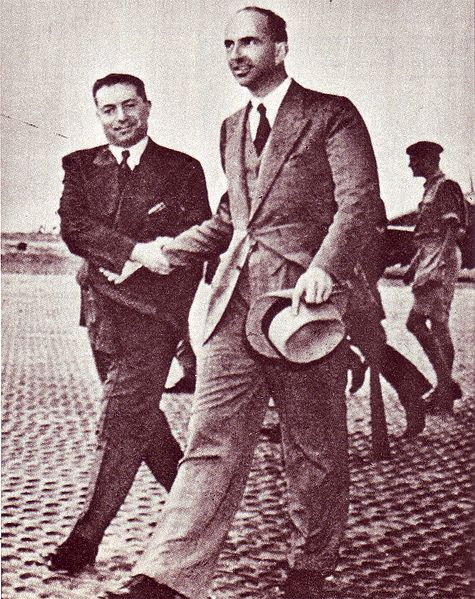

Early establishment of the republic and departure of the former king

On the night of 12 June the government met at Alcide De Gasperi's invitation. The Prime Minister received a written communication from the King, in which he said he was ready to respect the verdict of the electors' vote, but adding that he would await the final declaration of the Supreme Court of Cassation. The letter and the protests of the monarchists, like the bloody events of the day before in Naples, as well as the new demonstrations announced by the monarchists worried the ministers.

On 13 June, the Council of Ministers, extending the meeting begun the previous day, resolved that, following the proclamation of the provisional results on 10 June, the functions of provisional head of state would be exercised by Prime Minister Alcide De Gasperi, without wait for the final official confirmation from the Court of Cassation. The Prime Minister collected all the votes of the government members, with the exception of the liberal minister Leone Cattani.

Although some members of his entourage encouraged him to oppose this decision, the king, informed, decided to leave the country the following day, thus making a peaceful transfer of power possible, not without having denounced De Gasperi's "revolutionary gesture".

The former King of Italy, Umberto II, decided to leave Italy on 13 June, without even waiting for the results to be defined and the ruling on the appeals presented by the monarchist party, to avoid the clashes between monarchists and republicans, already manifested in bloody events in various Italian cities, for fear they could extend throughout the country. He went into exile in

On the night of 12 June the government met at Alcide De Gasperi's invitation. The Prime Minister received a written communication from the King, in which he said he was ready to respect the verdict of the electors' vote, but adding that he would await the final declaration of the Supreme Court of Cassation. The letter and the protests of the monarchists, like the bloody events of the day before in Naples, as well as the new demonstrations announced by the monarchists worried the ministers.

On 13 June, the Council of Ministers, extending the meeting begun the previous day, resolved that, following the proclamation of the provisional results on 10 June, the functions of provisional head of state would be exercised by Prime Minister Alcide De Gasperi, without wait for the final official confirmation from the Court of Cassation. The Prime Minister collected all the votes of the government members, with the exception of the liberal minister Leone Cattani.

Although some members of his entourage encouraged him to oppose this decision, the king, informed, decided to leave the country the following day, thus making a peaceful transfer of power possible, not without having denounced De Gasperi's "revolutionary gesture".

The former King of Italy, Umberto II, decided to leave Italy on 13 June, without even waiting for the results to be defined and the ruling on the appeals presented by the monarchist party, to avoid the clashes between monarchists and republicans, already manifested in bloody events in various Italian cities, for fear they could extend throughout the country. He went into exile in Cascais

Cascais () is a town and municipality in the Lisbon District of Portugal, located on the Portuguese Riviera, Estoril Coast. The municipality has a total of 214,158 inhabitants in an area of 97.40 km2. Cascais is an important tourism in Port ...

, Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, is a country on the Iberian Peninsula in Southwestern Europe. Featuring Cabo da Roca, the westernmost point in continental Europe, Portugal borders Spain to its north and east, with which it share ...

.

Changing the national flag and the national anthem

On the same day as the former king's departure, the flag of Italy with the Savoy coat of arms in the centre was lowered from the Quirinal Palace

The Quirinal Palace ( ) is a historic building in Rome, Italy, the main official residence of the President of Italy, President of the Italian Republic, together with Villa Rosebery in Naples and the Tenuta di Castelporziano, an estate on the outs ...

. The Italian flag was modified with the decree of the president of the Council of Ministers No. 1 of 19 June 1946. Compared to the monarchic banner, the Savoy coat of arms was eliminated. This decision was later confirmed in the session of 24 March 1947 by the Constituent Assembly

A constituent assembly (also known as a constitutional convention, constitutional congress, or constitutional assembly) is a body assembled for the purpose of drafting or revising a constitution. Members of a constituent assembly may be elected b ...

, which decreed the insertion of article 12 of the Italian Constitution, subsequently ratified by the Italian Parliament

The Italian Parliament () is the national parliament of the Italy, Italian Republic. It is the representative body of Italian citizens and is the successor to the Parliament of the Kingdom of Sardinia (1848–1861), the Parliament of the Kingd ...

, which states:

The Republican tricolour was then officially and solemnly delivered to the Italian military corps on 4 November 1947 on the occasion of National Unity and Armed Forces Day. The universally adopted ratio is 2:3, while the war flag is squared (1:1). Each ''comune

A (; : , ) is an administrative division of Italy, roughly equivalent to a township or municipality. It is the third-level administrative division of Italy, after regions () and provinces (). The can also have the City status in Italy, titl ...

'' also has a ''gonfalone

The gonfalon, gonfanon, gonfalone (from the early Italian language, Italian ''confalone'') is a type of heraldic flag or banner, often pointed, swallow-tailed, or with several streamers, and suspended from a crossbar in an identical manner to t ...

'' bearing its coat of arms. On 27 May 1949, a law was passed that described and regulated the way the flag was displayed outside public buildings and during national holidays.

After the birth of the Italian Republic, " La leggenda del Piave" was temporarily chosen as the provisional national anthem, which replaced "

After the birth of the Italian Republic, " La leggenda del Piave" was temporarily chosen as the provisional national anthem, which replaced "Marcia Reale

The "Marcia Reale d'Ordinanza" (; "Royal March of Ordinance"), or "Fanfara Reale" (; "Royal Fanfare"), was the official national anthem of the Kingdom of Italy between 1861 and 1946.(2001). National anthems. Grove Music Online. Retrieved 7 Feb. ...

", the national anthem of the Kingdom of Italy. For the choice of the national anthem a debate was opened which identified, among the possible options: the " Va, pensiero" from Giuseppe Verdi's ''Nabucco

''Nabucco'' (; short for ''Nabucodonosor'' , i.e. "Nebuchadnezzar II, Nebuchadnezzar") is an Italian-language opera in four acts composed in 1841 by Giuseppe Verdi to an Italian libretto by Temistocle Solera. The libretto is based on the biblic ...

'', the drafting of a completely new musical piece, "Il Canto degli Italiani

"" (; ) is a patriotic song written by Goffredo Mameli and set to music by Michele Novaro in 1847, currently used as the national anthem of Italy. It is best known among Italians as the "" (; ), after the author of the lyrics, or "" (; ), from ...

", the "Inno di Garibaldi" and the confirmation of "La Leggenda del Piave". The political class of the time then approved the proposal of the War Minister Cipriano Facchinetti, who foresaw the adoption of "Il Canto degli Italiani" as a provisional anthem of the State.

"La Leggenda del Piave" then had the function of the national anthem of the Italian Republic until the Council of Ministers

Council of Ministers is a traditional name given to the supreme Executive (government), executive organ in some governments. It is usually equivalent to the term Cabinet (government), cabinet. The term Council of State is a similar name that also m ...

of 12 October 1946, when Cipriano Facchinetti (of republican political belief), officially announced that during the celebrations of 4 November for National Unity and Armed Forces Day, in which the armed services of the republic will perform their oath of loyalty to the young republic, as a provisional anthem, "Il Canto degli Italiani" would have been adopted. The press release stated that:official

An official is someone who holds an office (function or Mandate (politics), mandate, regardless of whether it carries an actual Office, working space with it) in an organization or government and participates in the exercise of authority (eithe ...

status on 4 December 2017.

Final announcement of results and first steps of the Italian Republic

On 18 June 1946 at 6 pm, in the Sala della Lupa of Palazzo Montecitorio in Rome, the Supreme Court of Cassation proceeded to proclaim the results of the referendum, without accompanying this formalization with reservations as it had done previously.Constituent Assembly

A constituent assembly (also known as a constitutional convention, constitutional congress, or constitutional assembly) is a body assembled for the purpose of drafting or revising a constitution. Members of a constituent assembly may be elected b ...

, on 28 June 1946, Enrico De Nicola was elected provisional head of the State, in the first round with 396 votes out of 501. In addition to his personal qualities, the choice of a man born in Naples and long monarchic history, it was a sign of pacification and union towards the populations of southern Italy, in this accelerated transition towards the Republic. He was initially only provisional head of state and not president of Italy, since the latter did not yet have a constitution.Prime Minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

of the monarchic era and the first of republican Italy.President of Italy

The president of Italy, officially titled President of the Italian Republic (), is the head of state of Italy. In that role, the president represents national unity and guarantees that Politics of Italy, Italian politics comply with the Consti ...

. The validity of the provision that prohibited the entry in Italy of some members of the House of Savoy

The House of Savoy (, ) is a royal house (formally a dynasty) of Franco-Italian origin that was established in 1003 in the historical region of Savoy, which was originally part of the Kingdom of Burgundy and now lies mostly within southeastern F ...

ceased with the entry into force of the Constitutional Law of 23 October 2002, No. 1, after a debate in parliament and in the country that lasted many years and Vittorio Emanuele, Prince of Naples, son of King Umberto II, was able to enter Italy with his family already in the following December for a short visit. The former queen Marie-José had already been authorized to return to Italy in 1987 since, with the death of her husband Umberto II and having become a widow, her status as "spouse" was recognized as having ceased.

The symbolic photo of the birth of the Republic

The photo, which later became a "symbol" of the celebrations for the outcome of the referendum, portrays the face of a young woman emerging from a copy of '' Il Corriere della Sera'' of 6 June 1946 with the title «''È nata la Repubblica Italiana''» ("The Italian Republic is born").

The symbolic photo of the birth of the Republic was taken by Federico Patellani for the weekly ''Tempo

In musical terminology, tempo (Italian for 'time'; plural 'tempos', or from the Italian plural), measured in beats per minute, is the speed or pace of a given musical composition, composition, and is often also an indication of the composition ...

'' (n. 22, 15-22 June 1946) as part of a photo shoot celebrating the Republic and the new role of women; it was also featured on the front page of the ''Il Corriere della Sera'' itself and was later reused in many campaigns and posters.

''Festa della Repubblica''

''

''Festa della Repubblica

''Festa della Repubblica'' (; English: ''Republic Day'') is the Italian National Day and Republic Day, which is celebrated on 2 June each year, with the main celebration taking place in Rome. The ''Festa della Repubblica'' is one of the nationa ...

'' (; English: ''Republic Day'') is the Italian National Day and Republic Day, which is celebrated on 2 June each year, with the main celebration taking place in Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

. The ''Festa della Repubblica'' is one of the national symbols of Italy. The day commemorates the institutional referendum held by universal suffrage

Universal suffrage or universal franchise ensures the right to vote for as many people bound by a government's laws as possible, as supported by the " one person, one vote" principle. For many, the term universal suffrage assumes the exclusion ...

in 1946, in which the Italian people

Italians (, ) are a European peoples, European ethnic group native to the Italian geographical region. Italians share a common Italian culture, culture, History of Italy, history, Cultural heritage, ancestry and Italian language, language. ...

were called to the polls to decide on the form of government following World War II and the fall of Fascism

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural social hie ...

, monarchy or republic. On 2 June the birth of the modern Italian Republic is celebrated in a similar way to the French 14 July (anniversary of the storming of the Bastille

The Storming of the Bastille ( ), which occurred in Paris, France, on 14 July 1789, was an act of political violence by revolutionary insurgents who attempted to storm and seize control of the medieval armoury, fortress, and political prison k ...

) and to 4 July in the United States (anniversary of the declaration of independence from Great Britain). The first celebration of the ''Festa della Repubblica'' took place on 2 June 1947, while in 1948 there was the first military parade

A military parade is a formation of military personnels whose movement is restricted by close-order manoeuvering known as Drill team, drilling or marching. Large military parades are today held on major holidays and military events around the ...

in Via dei Fori Imperiali

The Via dei Fori Imperiali (formerly ''Via dei Monti'', then ''Via dell'Impero'') is a road in the centre of the city of Rome, Italy, that is in a straight line from the Piazza Venezia to the Colosseum. Its course takes it over parts of the For ...

in Rome;laurel wreath

A laurel wreath is a symbol of triumph, a wreath (attire), wreath made of connected branches and leaves of the bay laurel (), an aromatic broadleaf evergreen. It was also later made from spineless butcher's broom (''Ruscus hypoglossum'') or cher ...

by the President of Italy

The president of Italy, officially titled President of the Italian Republic (), is the head of state of Italy. In that role, the president represents national unity and guarantees that Politics of Italy, Italian politics comply with the Consti ...

in the presence of the most important officers of the State, or of the President of the Senate

President of the Senate is a title often given to the presiding officer of a senate. It corresponds to the Speaker (politics), speaker in some other assemblies.

The senate president often ranks high in a jurisdiction's Order of succession, succes ...

, the President of the Chamber of Deputies, the President of the Council of Ministers

The president of the Council of Ministers (sometimes titled chairman of the Council of Ministers) is the most senior member of the cabinet in the executive branch of government in some countries. Some presidents of the Council of Ministers are ...

, the President of the Constitutional Court, the Minister of Defense and the Chief of Defense.Il Canto degli Italiani

"" (; ) is a patriotic song written by Goffredo Mameli and set to music by Michele Novaro in 1847, currently used as the national anthem of Italy. It is best known among Italians as the "" (; ), after the author of the lyrics, or "" (; ), from ...

'', the Frecce Tricolori cross the skies of Rome.Via dei Fori Imperiali

The Via dei Fori Imperiali (formerly ''Via dei Monti'', then ''Via dell'Impero'') is a road in the centre of the city of Rome, Italy, that is in a straight line from the Piazza Venezia to the Colosseum. Its course takes it over parts of the For ...

, gets down the vehicle, and processes there to meet other dignitaries and as he arrives in his spot in the dais the Corazzieri's mounted troopers, which had provided the rear escort during the review phrase, salute the President as the anthem is played.Italian government

The government of Italy is that of a democratic republic, established by the Italian constitution in 1948. It consists of Legislature, legislative, Executive (government), executive, and Judiciary, judicial subdivisions, as well as of a head of ...

and for the presidents of the two chambers of parliament, to have pinned on their jacket, during the whole ceremony, an Italian tricolor cockade. Following the anthem, the military parade

A military parade is a formation of military personnels whose movement is restricted by close-order manoeuvering known as Drill team, drilling or marching. Large military parades are today held on major holidays and military events around the ...

begins, which the ground columns of military personnel saluting the President with eyes left or right with their colours dipped as they march past the dais. Mobile column crew contingent colour guards perform the salute in a like manner. The military parade also includes some military delegations from the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

, NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO ; , OTAN), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental Transnationalism, transnational military alliance of 32 Member states of NATO, member s ...

, the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are Geography of the European Union, located primarily in Europe. The u ...

and representatives of multinational departments with an Italian component.

On the holiday, at the Quirinale Palace, the Changing of the Guard with the Corazzieri Regiment and the Fanfare of the Carabinieri Cavalry Regiment in high uniform is carried out in solemn form.prefecture

A prefecture (from the Latin word, "''praefectura"'') is an administrative jurisdiction traditionally governed by an appointed prefect. This can be a regional or local government subdivision in various countries, or a subdivision in certain inter ...

for the local authorities, which are preceded by solemn public demonstrations with reduced military parades that have been reviewed by the prefect

Prefect (from the Latin ''praefectus'', substantive adjectival form of ''praeficere'': "put in front", meaning in charge) is a magisterial title of varying definition, but essentially refers to the leader of an administrative area.

A prefect' ...

in his capacity as the highest governmental authority in the province. Similar ceremonies are also organized by the Regions

In geography, regions, otherwise referred to as areas, zones, lands or territories, are portions of the Earth's surface that are broadly divided by physical characteristics (physical geography), human impact characteristics (human geography), and ...

and Municipalities

A municipality is usually a single administrative division having municipal corporation, corporate status and powers of self-government or jurisdiction as granted by national and regional laws to which it is subordinate.

The term ''municipality' ...

. All over the world, Italian embassies organize ceremonies to which the Heads of State of the host country are invited. Greetings from the other Heads of State reach the President of Italy from all over the world.

See also

* 1946 Italian general election

* Constituent Assembly of Italy

* Democracy in Europe

* History of the Italian Republic

* History of the Kingdom of Italy (1861–1946)

* Italian presidential elections

* Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy (, ) was a unitary state that existed from 17 March 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 10 June 1946, when the monarchy wa ...

* List of presidents of Italy

* President of Italy

The president of Italy, officially titled President of the Italian Republic (), is the head of state of Italy. In that role, the president represents national unity and guarantees that Politics of Italy, Italian politics comply with the Consti ...

* Presidential standard of Italy

* Proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy

The proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy happened with a legal norm, normative act of the House of Savoy, Savoyard Kingdom of Sardinia — the law 17 March 1861, n. 4761 — with which Victor Emmanuel II assumed for himself and for his successors ...

* '' Semestre bianco''

* Spouses and companions of the presidents of Italy

Notes

References

Sources

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

External links

Gazzetta Ufficiale No. 134, 20 June 1946

Constitution of the Italian Republic

{{Authority control

History of the Italian Republic

Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

Institutional

An institution is a humanly devised structure of rules and norms that shape and constrain social behavior. All definitions of institutions generally entail that there is a level of persistence and continuity. Laws, rules, social conventions and ...

Referendums in Italy

Monarchy referendums

Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

Victor Emmanuel III

Umberto II of Italy

In the

In the  The political projects of Mazzini and Cattaneo were thwarted by the action of the Piedmontese Prime Minister

The political projects of Mazzini and Cattaneo were thwarted by the action of the Piedmontese Prime Minister

The balance of power between the Chamber and Senate initially shifted in favor of the Senate, composed mainly of nobles and industrial figures. Little by little, the Chamber of Deputies took on more and more importance with the evolution of the bourgeoisie and the large landowners, concerned with economic progress, but supporters of order and a certain