Isaac Newton's Occult Studies on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

English physicist and mathematician

English physicist and mathematician

Much of what are known as Isaac Newton's

Much of what are known as Isaac Newton's

online review

* Principe, Lawrence M. "Reflections on Newton's alchemy in light of the new historiography of alchemy." in J.E. Force and S Hutton, eds. ''Newton and Newtonianism'' (Springer, 2004) pp. 205–219

online

* Schilt, Cornelis J. ''Isaac Newton and the Study of Chronology: Prophecy, History, and Method'' (Amsterdam University Press, 2021). * White, Michael. ''Isaac Newton: The Last Sorcerer'' (1997). * *

An archive of Newton's texts

*

English physicist and mathematician

English physicist and mathematician Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton () was an English polymath active as a mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author. Newton was a key figure in the Scientific Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment that followed ...

produced works exploring chronology

Chronology (from Latin , from Ancient Greek , , ; and , ''wikt:-logia, -logia'') is the science of arranging events in their order of occurrence in time. Consider, for example, the use of a timeline or sequence of events. It is also "the deter ...

, and biblical interpretation

Biblical hermeneutics is the study of the principles of interpretation concerning the books of the Bible. It is part of the broader field of hermeneutics, which involves the study of principles of interpretation, both theory and methodology, fo ...

(especially of the Apocalypse

Apocalypse () is a literary genre originating in Judaism in the centuries following the Babylonian exile (597–587 BCE) but persisting in Christianity and Islam. In apocalypse, a supernatural being reveals cosmic mysteries or the future to a ...

), and alchemy

Alchemy (from the Arabic word , ) is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practised in China, India, the Muslim world, and Europe. In its Western form, alchemy is first ...

. Some of this could be considered occult

The occult () is a category of esoteric or supernatural beliefs and practices which generally fall outside the scope of organized religion and science, encompassing phenomena involving a 'hidden' or 'secret' agency, such as magic and mysti ...

. Newton's scientific work may have been of lesser personal importance to him, as he placed emphasis on rediscovering the wisdom of the ancients. Historical research on Newton's occult studies in relation to his science have also been used to challenge the disenchantment

In social science, disenchantment () is the cultural rationalization and devaluation of religion apparent in modern society. The term was borrowed from Friedrich Schiller by Max Weber to describe the character of a modernized, bureaucratic, ...

narrative within critical theory

Critical theory is a social, historical, and political school of thought and philosophical perspective which centers on analyzing and challenging systemic power relations in society, arguing that knowledge, truth, and social structures are ...

.

Newton lived during the early modern period

The early modern period is a Periodization, historical period that is defined either as part of or as immediately preceding the modern period, with divisions based primarily on the history of Europe and the broader concept of modernity. There i ...

, when the educated embraced a world view

A worldview (also world-view) or is said to be the fundamental cognitive orientation of an individual or society encompassing the whole of the individual's or society's knowledge, culture, and point of view. However, when two parties view the s ...

different from that of later centuries. Distinctions between science, superstition

A superstition is any belief or practice considered by non-practitioners to be irrational or supernatural, attributed to fate or magic (supernatural), magic, perceived supernatural influence, or fear of that which is unknown. It is commonly app ...

, and pseudoscience

Pseudoscience consists of statements, beliefs, or practices that claim to be both scientific and factual but are incompatible with the scientific method. Pseudoscience is often characterized by contradictory, exaggerated or unfalsifiable cl ...

were still being formulated, and a devoutly Christian biblical perspective permeated Western culture.

Alchemical research

Much of what are known as Isaac Newton's

Much of what are known as Isaac Newton's occult

The occult () is a category of esoteric or supernatural beliefs and practices which generally fall outside the scope of organized religion and science, encompassing phenomena involving a 'hidden' or 'secret' agency, such as magic and mysti ...

studies can largely be attributed to his study of alchemy

Alchemy (from the Arabic word , ) is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practised in China, India, the Muslim world, and Europe. In its Western form, alchemy is first ...

. From a young age, Newton was deeply interested in all forms of natural sciences

Natural science or empirical science is one of the branches of science concerned with the description, understanding and prediction of natural phenomena, based on empirical evidence from observation and experimentation. Mechanisms such as peer ...

and materials science

Materials science is an interdisciplinary field of researching and discovering materials. Materials engineering is an engineering field of finding uses for materials in other fields and industries.

The intellectual origins of materials sci ...

, an interest which would ultimately lead to some of his better-known contributions to science. His earliest encounters with certain alchemical theories and practices were when he was twelve years old, and boarding in the attic of an apothecary's shop. During Newton's lifetime, the study of chemistry

Chemistry is the scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a physical science within the natural sciences that studies the chemical elements that make up matter and chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules a ...

was still in its infancy, so many of his experimental studies used esoteric language and vague terminology more typically associated with alchemy and occultism. It was not until several decades after Newton's death that experiments of stoichiometry

Stoichiometry () is the relationships between the masses of reactants and Product (chemistry), products before, during, and following chemical reactions.

Stoichiometry is based on the law of conservation of mass; the total mass of reactants must ...

under the pioneering works of Antoine Lavoisier

Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier ( ; ; 26 August 17438 May 1794), When reduced without charcoal, it gave off an air which supported respiration and combustion in an enhanced way. He concluded that this was just a pure form of common air and that i ...

were conducted, and analytical chemistry, with its associated nomenclature, came to resemble modern chemistry as we know it today. However, Newton's contemporary and fellow Royal Society member Robert Boyle

Robert Boyle (; 25 January 1627 – 31 December 1691) was an Anglo-Irish natural philosopher, chemist, physicist, Alchemy, alchemist and inventor. Boyle is largely regarded today as the first modern chemist, and therefore one of the foun ...

had already discovered the basic concepts of modern chemistry and began establishing modern norms of experimental practice and communication in chemistry, information which Newton did not use.

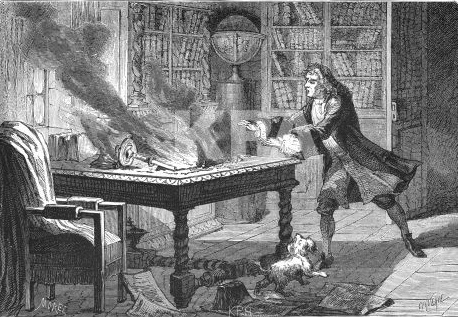

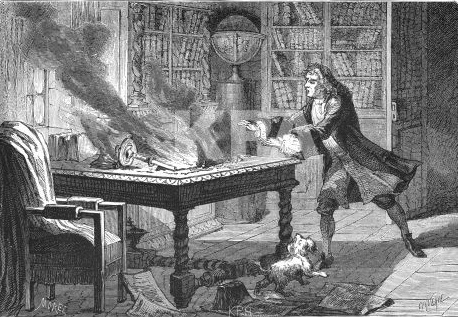

Much of Newton's writing on alchemy may have been lost in a fire in his laboratory, so the true extent of his work in this area may have been larger than is currently known. Newton also suffered a nervous breakdown

A mental disorder, also referred to as a mental illness, a mental health condition, or a psychiatric disability, is a behavioral or mental pattern that causes significant distress or impairment of personal functioning. A mental disorder is ...

during his period of alchemical work.

Newton's writings suggest that one of the main goals of his alchemy may have been the discovery of the philosopher's stone

The philosopher's stone is a mythic alchemical substance capable of turning base metals such as mercury into gold or silver; it was also known as "the tincture" and "the powder". Alchemists additionally believed that it could be used to mak ...

(a material believed to turn base metals into gold), and perhaps to a lesser extent, the discovery of the highly coveted Elixir of Life

The elixir of life (Medieval Latin: ' ), also known as elixir of immortality, is a potion that supposedly grants the drinker Immortality, eternal life and/or eternal youth. This elixir was also said to Panacea (medicine), cure all diseases. Alch ...

. Newton reportedly believed that Diana's Tree, an alchemical demonstration producing a dendritic

Dendrite derives from the Greek word "dendron" meaning ( "tree-like"), and may refer to:

Biology

*Dendrite, a branched projection of a neuron

*Dendrite (non-neuronal), branching projections of certain skin cells and immune cells

Physical

*Dendri ...

"growth" of silver from solution, was evidence that metals "possessed a sort of life."

Some practices of alchemy were banned in England during Newton's lifetime, due in part to unscrupulous practitioners who would often promise wealthy benefactors unrealistic results in an attempt to swindle them. The English Crown

The Crown is a political concept used in Commonwealth realms. Depending on the context used, it generally refers to the entirety of the state (or in federal realms, the relevant level of government in that state), the executive government spec ...

, also fearing the potential devaluation of gold because of the creation of fake gold, made penalties for alchemy very severe. In some cases, the punishment for unsanctioned alchemy would include the public hanging of an offender on a gilded scaffold while adorned with tinsel and other items.

Writings

Due to the threat of punishment and the potential scrutiny he feared from his peers within the scientific community, Newton may have deliberately left his work on alchemical subjects unpublished. Newton was well known as being highly sensitive to criticism, such as the numerous instances when he was criticized byRobert Hooke

Robert Hooke (; 18 July 16353 March 1703) was an English polymath who was active as a physicist ("natural philosopher"), astronomer, geologist, meteorologist, and architect. He is credited as one of the first scientists to investigate living ...

, and his admitted reluctance to publish any substantial information regarding calculus

Calculus is the mathematics, mathematical study of continuous change, in the same way that geometry is the study of shape, and algebra is the study of generalizations of arithmetic operations.

Originally called infinitesimal calculus or "the ...

before 1693. A perfectionist by nature, Newton also refrained from publication of material that he felt was incomplete, as evident from a 38-year gap from Newton's conception of calculus in 1666 and its final full publication in 1704, which would ultimately lead to the infamous Leibniz–Newton calculus controversy

In the history of calculus, the calculus controversy () was an argument between mathematicians Isaac Newton and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz over who had first discovered calculus. The question was a major intellectual controversy, beginning in 16 ...

.

Most of the scientist's manuscript heritage after his death passed to John Conduitt

John Conduitt (; c. 8 March 1688 – 23 May 1737), of Cranbury Park, Hampshire, was a British landowner and Whig politician. He sat in the House of Commons from 1721 to 1737. He was married to the half-niece of Sir Isaac Newton, whom Conduitt ...

, the husband of his niece Catherine

Katherine (), also spelled Catherine and Catherina, other variations, is a feminine given name. The name and its variants are popular in countries where large Christian populations exist, because of its associations with one of the earliest Ch ...

. To evaluate the manuscripts, physician Thomas Pellet was involved, who decided that only " the Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms", an unreleased fragment of " Principia", "Observations upon the Prophesies of Daniel and the Apocalypse of St. John" and "Paradoxical Questions Concerning the Morals and Actions of Athanasius and His Followers" were suitable for publication. The remaining manuscripts, according to Pellet, were "foul draughts of the Prophetic stile" and were not suitable for publication. After the death of J. Conduitt in 1737, manuscripts were transferred to Catherine, who unsuccessfully tried to publish the theological notes of her uncle. She consulted with Newton's friend, the theologian Arthur Ashley Sykes (1684–1756). Sykes kept eleven manuscripts for himself, and the rest of the archive passed into the family of Catherine's daughter, who married the John Wallop, Viscount Lymington, and was then owned by the Earls of Portsmouth. After Sykes' death, his documents came to the Rev. Jeffery Ekins (d. 1791) and were kept in his family until they were presented to the New College, Oxford

New College is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. Founded in 1379 by Bishop William of Wykeham in conjunction with Winchester College as New College's feeder school, New College was one of the first col ...

in 1872. Until the mid-19th century, few had access to the Portsmouth collection, including David Brewster, a renowned physicist and biographer of Newton. In 1872, the fifth Earl of Portsmouth transferred part of the manuscripts (mainly of a physical and mathematical nature) to Cambridge University

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

.

In 1936, a collection of Isaac Newton's unpublished works was auctioned by Sotheby's

Sotheby's ( ) is a British-founded multinational corporation with headquarters in New York City. It is one of the world's largest brokers of fine art, fine and decorative art, jewellery, and collectibles. It has 80 locations in 40 countries, an ...

on behalf of Gerard Wallop, 9th Earl of Portsmouth

Gerard Vernon Wallop, 9th Earl of Portsmouth (16 May 1898 – 28 September 1984), styled Viscount Lymington from 1925 until 1943, was a British landowner, writer on agricultural topics, and pro-Axis fascist politician.

Early life

Gerard was bo ...

. Known as the "Portsmouth Papers", this material consisted of 329 lots of Newton's manuscripts, over a third of which were filled with content that appeared to be alchemical in nature. At the time of Newton's death this material was considered "unfit to publish" by Newton's estate, and consequently fell into obscurity until their somewhat sensational reemergence in 1936.

At the auction, many of these documents, along with Newton's death mask

A death mask is a likeness (typically in wax or plaster cast) of a person's face after their death, usually made by taking a cast or impression from the corpse. Death masks may be mementos of the dead or be used for creation of portraits. The m ...

, were purchased by economist John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes, 1st Baron Keynes ( ; 5 June 1883 – 21 April 1946), was an English economist and philosopher whose ideas fundamentally changed the theory and practice of macroeconomics and the economic policies of governments. Originall ...

, who throughout his life collected many of Newton's alchemical writings. Much of the Keynes collection later passed to document collector Abraham Yahuda, who was himself a vigorous collector of Isaac Newton's original manuscripts.

Many of the documents collected by Keynes and Yahuda are now in the Jewish National and University Library in Jerusalem. In recent years, several projects have begun to gather, catalogue, and transcribe the fragmented collection of Newton's work on alchemical subjects and make them freely available for online access. Two of these are ''The Chymistry of Isaac Newton Project'' supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation

The U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) is an Independent agencies of the United States government#Examples of independent agencies, independent agency of the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government that su ...

, and The Newton Project supported by the U.K. Arts and Humanities Research Board

The arts or creative arts are a vast range of human practices involving creative expression, storytelling, and cultural participation. The arts encompass diverse and plural modes of thought, deeds, and existence in an extensive range of me ...

. In addition, The Jewish National and University Library has published a number of high-quality scanned images of various Newton documents.

The Philosopher's Stone

Of the material sold during the 1936 Sotheby's auction, several documents indicate an interest by Newton in the procurement or development of thephilosopher's stone

The philosopher's stone is a mythic alchemical substance capable of turning base metals such as mercury into gold or silver; it was also known as "the tincture" and "the powder". Alchemists additionally believed that it could be used to mak ...

. Most notable are documents entitled ''Artephius his secret Book'', followed by ''The Epistle of Iohn Pontanus, wherein he beareth witness of ye book of Artephius''; these are themselves a collection of excerpts from another work entitled ''Nicholas Flammel, His Exposition of the Hieroglyphicall Figures which he caused to be painted upon an Arch in St Innocents Church-yard in Paris''. Together with ''The secret Booke of Artephius, And the Epistle of Iohn Pontanus: Containing both the Theoricke and the Practicke of the Philosophers Stone''. This work may also have been referenced by Newton in its Latin version found within Lazarus Zetzner's '' Theatrum Chemicum'', a volume often associated with the '' Turba Philosophorum'', and other early European alchemical manuscripts. Nicolas Flamel, one subject of the aforementioned work, was a notable, though mysterious figure, often associated with the discovery of the philosopher's stone, hieroglyphical figures, early forms of tarot

Tarot (, first known as ''trionfi (cards), trionfi'' and later as ''tarocchi'' or ''tarocks'') is a set of playing cards used in tarot games and in fortune-telling or divination. From at least the mid-15th century, the tarot was used to play t ...

, and occultism. Artephius, and his "secret book", were also subjects of interest to 17th-century alchemists.

Also in the 1936 auction of Newton's collection was ''The Epitome of the treasure of health written by Edwardus Generosus Anglicus innominatus who lived Anno Domini 1562''. This is a twenty-eight-page treatise on the philosopher's stone, the Animal or Angelicall Stone, the Prospective stone or magical stone of Moses, and the vegetable or the growing stone. The treatise concludes with an alchemical poem.

Other works

Newton's various surviving alchemical notebooks clearly show that he made no distinctions between alchemy and what's now considered science. Optical experiments were written on the same pages as recipes from arcane sources. Newton did not always record his chemical experiments in the most transparent way. Alchemists were notorious for veiling their writings in impenetrable jargon; Newton himself invented new symbols and systems.Biblical studies

In a manuscript from 1704, Newton describes his attempts to extract scientific information from the Bible and estimates that the world would end no earlier than 2060. In predicting this, he said, "This I mention not to assert when the time of the end shall be, but to put a stop to the rash conjectures of fanciful men who are frequently predicting the time of the end, and by doing so bring the sacred prophecies into discredit as often as their predictions fail."Newton's studies of the Temple of Solomon

Newton extensively studied and wrote about the Temple of Solomon, dedicating an entire chapter of ''The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms Amended

''The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms Amended'' is a work of chronology, historical chronology written by Sir Isaac Newton, first published posthumously in 1728. Since then it has been republished. The work, some 87,000 words, represents one of N ...

'' to his observations of the temple. Newton's primary source for information was the description of the structure given within 1 Kings of the Hebrew Bible as well as the Book of Ezekiel

The Book of Ezekiel is the third of the Nevi'im#Latter Prophets, Latter Prophets in the Hebrew Bible, Tanakh (Hebrew Bible) and one of the Major Prophets, major prophetic books in the Christian Bible, where it follows Book of Isaiah, Isaiah and ...

, which he translated himself from Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

with the help of dictionaries, as his knowledge of that language was limited.

In addition to scripture, Newton also relied upon various ancient and contemporary sources while studying the temple. He believed that many ancient sources were endowed with sacred wisdom and that the proportions of many of their temples were in themselves sacred. This concept, often termed '' prisca sapientia'' (sacred wisdom and also the ancient wisdom that was revealed to Adam and Moses directly by God), was a common belief of many scholars during Newton's lifetime.

A more contemporary source for Newton's studies of the temple was Juan Bautista Villalpando, who just a few decades earlier had published an influential manuscript entitled ''In Ezechielem explanationes et apparatus urbis, ac templi Hierosolymitani'' (1596–1605), in which Villalpando comments on the visions of the biblical prophet Ezekiel

Ezekiel, also spelled Ezechiel (; ; ), was an Israelite priest. The Book of Ezekiel, relating his visions and acts, is named after him.

The Abrahamic religions acknowledge Ezekiel as a prophet. According to the narrative, Ezekiel prophesied ...

, including within this work his own interpretations and elaborate reconstructions of Solomon's Temple. In its time, Villalpando's work on the temple produced a great deal of interest throughout Europe and had a significant impact upon later architects and scholars.

Newton believed that the temple was designed by King Solomon

King is a royal title given to a male monarch. A king is an absolute monarch if he holds unrestricted governmental power or exercises full sovereignty over a nation. Conversely, he is a constitutional monarch if his power is restrained by f ...

with privileged eyes and divine guidance. To Newton, the geometry of the temple represented more than a mathematical blueprint; it also provided a time-frame chronology of Hebrew history. It was for this reason that he included a chapter devoted to the temple within ''The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms Amended''.

Newton felt that just as the writings of ancient philosophers, scholars, and biblical figures contained within them unknown sacred wisdom, the same was true of their architecture. He believed that these men had hidden their knowledge in a complex code of symbolic and mathematical language that, when deciphered, would reveal an unknown knowledge of how nature works.

In 1675, Newton annotated a copy of ''Manna – a disquisition of the nature of alchemy'', an anonymous treatise which had been given to him by his fellow scholar Ezechiel Foxcroft

Ezechiel Foxcroft (1633, London – 1676) was an English esotericist who produced the first translation of the '' Chymical Wedding of Christian Rosenkreutz '' published in 1690.

Life

He was the son of the prominent merchant George Foxcroft, and ...

. In his annotation Newton reflected upon his reasons for examining Solomon's Temple:

During Newton's lifetime, there was great interest in the Temple of Solomon in Europe, due to the success of Villalpando's publications, and a vogue for detailed engraving

Engraving is the practice of incising a design on a hard, usually flat surface by cutting grooves into it with a Burin (engraving), burin. The result may be a decorated object in itself, as when silver, gold, steel, or Glass engraving, glass ar ...

s and physical model

A model is an informative representation of an object, person, or system. The term originally denoted the plans of a building in late 16th-century English, and derived via French and Italian ultimately from Latin , .

Models can be divided int ...

s presented in various galleries for public viewing. In 1628, Judah Leon Templo produced a model of the temple and surrounding Jerusalem, which was popular in its day. Around 1692, Gerhard Schott produced a highly detailed model of the temple, for use in an opera in Hamburg composed by Christian Heinrich Postel. This immense and model was later sold in 1725 and was exhibited in London as early as 1723, and then later temporarily installed at the London Royal Exchange from 1729 to 1730, where it could be viewed for half-a-crown. Isaac Newton's most comprehensive work on the temple, found within ''The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms Amended'', was published posthumously in 1728, only adding to the public interest in the temple.

Newton's interpretations of prophecy

Newton considered himself to be one of a select group of individuals who were specially chosen by God for the task of understanding biblical scripture. He was a strong believer in a prophetic interpretation of the Bible, and like many of his contemporaries in Protestant England, he developed a strong affinity and deep admiration for the teachings and works ofJoseph Mede

Joseph Mede (1586 in Berden – 1639) was an English scholar with a wide range of interests. He was educated at Christ's College, Cambridge, where he became a Fellow in 1613. He is now remembered as a biblical scholar. He was also a naturalist ...

. Although he never wrote a cohesive body of work on prophecy, Newton's belief led him to write several treatises on the subject, including an unpublished guide for prophetic interpretation entitled ''Rules for interpreting the words & language in Scripture''. In this manuscript he details the necessary requirements for what he considered to be the proper interpretation of the Bible.

In addition, Newton would spend much of his life seeking and revealing what could be considered a Bible Code

The Bible code (, ), also known as the Torah code, is a purported set of encoded words within a Hebrew text of the Torah that, according to proponents, has predicted significant historical events. The statistical likelihood of the Bible code a ...

. He placed a great deal of emphasis upon the interpretation of the Book of Revelation

The Book of Revelation, also known as the Book of the Apocalypse or the Apocalypse of John, is the final book of the New Testament, and therefore the final book of the Bible#Christian Bible, Christian Bible. Written in Greek language, Greek, ...

, writing generously upon this book and authoring several manuscripts detailing his interpretations. Unlike a prophet

In religion, a prophet or prophetess is an individual who is regarded as being in contact with a divinity, divine being and is said to speak on behalf of that being, serving as an intermediary with humanity by delivering messages or teachings ...

in the true sense of the word, Newton relied upon existing Scripture to prophesy for him, believing his interpretations would set the record straight in the face of what he considered to be "so little understood". In 1754, 27 years after his death, Isaac Newton's treatise '' An Historical Account of Two Notable Corruptions of Scripture'' would be published, and although it does not argue any prophetic meaning, it does exemplify what Newton considered to be just one popular misunderstanding of Scripture.

Although Newton's approach to these studies could not be considered a scientific approach, he did write as if his findings were the result of evidence-based research.

2060

In late February and early March 2003, a large amount of media attention circulated around the globe regarding largely unknown and unpublished documents, evidently written by Isaac Newton, indicating that he believed the world would end no earlier than 2060. The story garnered vast amounts of public interest and found its way onto the front page of several widely distributed newspapers, including the UK'sDaily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a British daily broadsheet conservative newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed in the United Kingdom and internationally. It was foun ...

, Canada's National Post

The ''National Post'' is a Canadian English-language broadsheet newspaper and the flagship publication of the American-owned Postmedia Network. It is published Mondays through Saturdays, with Monday released as a digital e-edition only.

, Israel's Maariv

''Maariv'' or ''Maʿariv'' (, ), also known as ''Arvit'', or ''Arbit'' (, ), is a Jewish prayer service held in the evening or at night. It consists primarily of the evening '' Shema'' and ''Amidah''.

The service will often begin with two ...

and Yediot Aharonot

(, ; lit. "Latest News") is an Israeli daily mass market newspaper published in Tel Aviv. Founded in 1939, is Israel's largest paid newspaper by sales and circulation and has been described as "undoubtedly the country's number-one paper."

, and was also featured in an article in the scientific journal '' Canadian Journal of History''. Television and internet stories in the following weeks heightened the exposure and ultimately would include the production of several documentary films focused upon the topic of the 2060 prediction and some of Newton's lesser known beliefs and practices.

The two documents detailing this prediction are currently housed within the Jewish National and University Library in Jerusalem. Both were believed to be written toward the end of Newton's life, circa 1705, a time frame most notably established by the use of the full title of ''Sir'' Isaac Newton within portions of the documents.

These documents do not appear to have been written with the intention of publication and Newton expressed a strong personal dislike for individuals who provided specific dates for the Apocalypse purely for sensational value. Furthermore, he at no time provides a specific date for the end of the world in either of these documents.

To understand the reasoning behind the 2060 prediction, an understanding of Newton's theological beliefs should be taken into account, particularly his apparent antitrinitarian

Nontrinitarianism is a form of Christianity that rejects the orthodox Christian theology of the Trinity—the belief that God is three distinct hypostases or persons who are coeternal, coequal, and indivisibly united in one being, or essence ...

beliefs and his Protestant views on the Papacy

The pope is the bishop of Rome and the Head of the Church#Catholic Church, visible head of the worldwide Catholic Church. He is also known as the supreme pontiff, Roman pontiff, or sovereign pontiff. From the 8th century until 1870, the po ...

. Both of these lay essential to his calculations, which ultimately would provide the 2060 time frame. See Isaac Newton's religious views

Isaac Newton (4 January 1643 – 31 March 1727) was considered an insightful and erudite theologian by his Protestant contemporaries. NGLISH & LATINIslamic theology

Schools of Islamic theology are various Islamic schools and branches in different schools of thought regarding creed. The main schools of Islamic theology include the extant Mu'tazili, Ash'ari, Maturidi, and Athari schools; the extinct ones ...

this concept is often referred to as The Second Coming

The Second Coming (sometimes called the Second Advent or the Parousia) is the Christianity, Christian and Islam, Islamic belief that Jesus, Jesus Christ will return to Earth after his Ascension of Jesus, ascension to Heaven (Christianity), Heav ...

of Jesus Christ

Jesus (AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ, Jesus of Nazareth, and many Names and titles of Jesus in the New Testament, other names and titles, was a 1st-century Jewish preacher and religious leader. He is the Jesus in Chris ...

and the establishment of The Kingdom of God

The concept of the kingship of God appears in all Abrahamic religions, where in some cases the terms kingdom of God and kingdom of Heaven are also used. The notion of God's kingship goes back to the Hebrew Bible, which refers to "his kingdom" ...

on Earth. In a separate manuscript, Isaac Newton paraphrases Revelation 21 and 22 and relates the post 2060 events by writing:

Newton's chronology

Newton wrote extensively upon the historical topic ofchronology

Chronology (from Latin , from Ancient Greek , , ; and , ''wikt:-logia, -logia'') is the science of arranging events in their order of occurrence in time. Consider, for example, the use of a timeline or sequence of events. It is also "the deter ...

. In 1728 ''The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms Amended

''The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms Amended'' is a work of chronology, historical chronology written by Sir Isaac Newton, first published posthumously in 1728. Since then it has been republished. The work, some 87,000 words, represents one of N ...

'', an approximately 87,000-word composition that details the rise and history of various ancient kingdoms, was published. It was published posthumously, although the majority of it had been reviewed for publication by Newton himself. As such, this work represents one of his last known personally reviewed publications. Sometime around 1701, he also produced a thirty-page unpublished treatise entitled "The Original of Monarchies" detailing the rise of several monarchs throughout antiquity, and tracing them back to the biblical figure of Noah

Noah (; , also Noach) appears as the last of the Antediluvian Patriarchs (Bible), patriarchs in the traditions of Abrahamic religions. His story appears in the Hebrew Bible (Book of Genesis, chapters 5–9), the Quran and Baháʼí literature, ...

.

Newton's chronological writing focuses on Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

, Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

, Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

, and the Levant

The Levant ( ) is the subregion that borders the Eastern Mediterranean, Eastern Mediterranean sea to the west, and forms the core of West Asia and the political term, Middle East, ''Middle East''. In its narrowest sense, which is in use toda ...

. Many of his dates do not correlate with current historical knowledge. While Newton mentions several pre-historical events found within the Bible, the oldest actual historical date he provides is 1125 BC. In this entry he mentions Mephres, a ruler over Upper Egypt

Upper Egypt ( ', shortened to , , locally: ) is the southern portion of Egypt and is composed of the Nile River valley south of the delta and the 30th parallel North. It thus consists of the entire Nile River valley from Cairo south to Lake N ...

from the territories of Syene to Heliopolis, and his successor Misphragmuthosis. However, during 1125 BC the Pharaoh of Egypt is now understood to be Ramesses IX.

Although some of the dates Newton provides for various events are accurate by 17th century standards, archaeology

Archaeology or archeology is the study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of Artifact (archaeology), artifacts, architecture, biofact (archaeology), biofacts or ecofacts, ...

as a form of modern science did not exist in Newton's time. In fact, the majority of the conclusionary dates which Newton cites are based on the works of Herodotus

Herodotus (; BC) was a Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus (now Bodrum, Turkey), under Persian control in the 5th century BC, and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria, Italy. He wrote the '' Histori ...

, Pliny, Plutarch

Plutarch (; , ''Ploútarchos'', ; – 120s) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo (Delphi), Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''Parallel Lives'', ...

, Homer

Homer (; , ; possibly born ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Despite doubts about his autho ...

, and various other classical historians, authors, and poets who were themselves often citing secondary sources and oral records of uncertain date.

Newton's Atlantis

''The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms Amended'' contains passages on the land ofAtlantis

Atlantis () is a fictional island mentioned in Plato's works '' Timaeus'' and ''Critias'' as part of an allegory on the hubris of nations. In the story, Atlantis is described as a naval empire that ruled all Western parts of the known world ...

. The first such passage is part of his ''Short Chronicle'' which indicates his belief that Homer's Ulysses left the island of Ogygia

Ogygia (; , or ''Ōgygíā'' ) is an island mentioned in Homer's ''Odyssey'', Book V, as the home of the nymph Calypso (mythology), Calypso, the daughter of the Titan (mythology), Titan Atlas (mythology), Atlas. In Homer's ''Odyssey'', Calyps ...

in 896 BC. In Greek mythology

Greek mythology is the body of myths originally told by the Ancient Greece, ancient Greeks, and a genre of ancient Greek folklore, today absorbed alongside Roman mythology into the broader designation of classical mythology. These stories conc ...

, Ogygia was home to Calypso, the daughter of Atlas

An atlas is a collection of maps; it is typically a bundle of world map, maps of Earth or of a continent or region of Earth. Advances in astronomy have also resulted in atlases of the celestial sphere or of other planets.

Atlases have traditio ...

(after whom Atlantis was named). Some scholars have suggested that Ogygia and Atlantis are locationally connected, or possibly the same island. From his writings it appears Newton may have shared this belief. Newton also lists Cadis or Cales

Cales was an ancient city of Campania, in today's ''comune'' of Calvi Risorta in southern Italy, belonging originally to the Aurunci/ Ausoni, on the Via Latina.

The Romans captured it in 335 BC and established a colony with Latin rights of ...

as possible candidates for Ogygia, though does not cite his reasons for believing so.

Newton and secret societies

Newton has often been associated with varioussecret societies

A secret society is an organization about which the activities, events, inner functioning, or membership are concealed. The society may or may not attempt to conceal its existence. The term usually excludes covert groups, such as intelligence a ...

and fraternal orders

Fraternal may refer to:

* Fraternal organization, an organized society of men associated together in an environment of companionship and brotherhood, dedicated to the intellectual, physical, and social development of its members

* Fraternal order ...

throughout history. Due to a lack of reliable sources, it is difficult to establish his actual membership in any specific organization, despite the number of Masonic buildings named after him.

Regardless of his own membership status, Newton was a known associate of many individuals who themselves have often been labeled as members of various esoteric groups. It is unclear if these associations were a result of his being a well established and prominently publicized scholar, an early member and sitting President of the Royal Society

The president of the Royal Society (PRS), also known as the Royal Society of London, is the elected Head of the Royal Society who presides over meetings of the society's council.

After an informal meeting (a lecture) by Christopher Wren at Gres ...

(1703–1727), a prominent figure of State and Master of the Mint

Master of the Mint is a title within the Royal Mint given to the most senior person responsible for its operation. It was an office in the governments of Scotland and England, and later Great Britain and then the United Kingdom, between the 16th ...

, a recognized Knight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of a knighthood by a head of state (including the pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church, or the country, especially in a military capacity.

The concept of a knighthood ...

, or if Newton actually sought active membership within these esoteric organizations himself. Considering the nature and legality of alchemical practices during his lifetime, as well as his possession of various materials and manuscripts pertaining to alchemical research, Newton may very well have been a member of a group of like minded thinkers and colleagues. The organized level of this group (if in fact any existed), the level of their secrecy, as well as the depth of Newton's involvement within them, remains unclear.

He was known to be a member of The Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, r ...

of London for the Improvement of Natural Knowledge and the Spalding Gentlemen's Society

The Spalding Gentlemen's Society is a learned society based in Spalding, Lincolnshire, Spalding, Lincolnshire, England, concerned with cultural, scientific and antiquarian subjects. It is Britain's oldest such provincial body, founded in 1710 by ...

, but these are considered learned societies

A learned society ( ; also scholarly, intellectual, or academic society) is an organization that exists to promote an academic discipline, profession, or a group of related disciplines such as the arts and sciences. Membership may be open to al ...

, and not esoteric societies. Newton's membership status within any particular secret society remains largely speculative.

Newton and the Rosicrucians

Perhaps the movement which most influenced Isaac Newton wasRosicrucianism

Rosicrucianism () is a spiritual and cultural movement that arose in early modern Europe in the early 17th century after the publication of several texts announcing to the world a new esoteric order. Rosicrucianism is symbolized by the Rose ...

.

The Rosicrucian belief in being specially chosen for the ability to communicate with angels or spirits is echoed in Newton's prophetic beliefs. Additionally, the Rosicrucians proclaimed to have the ability to live forever through the use of the '' elixir vitae'' and the ability to produce limitless amounts of time and gold from the use of the philosopher's stone

The philosopher's stone is a mythic alchemical substance capable of turning base metals such as mercury into gold or silver; it was also known as "the tincture" and "the powder". Alchemists additionally believed that it could be used to mak ...

, which they claimed to have in their possession. Like Newton, the Rosicrucians were deeply religious, avowedly Christian, anti-Catholic, and highly politicised. Isaac Newton would have a deep interest in not just their alchemical pursuits, but also their belief in esoteric truths of the ancient past and the belief in enlightened individuals with the ability to gain insight into nature, the physical universe, and the spiritual realm.

At the time of his death, Newton had 169 books on the topic of alchemy in his personal library, and was believed to have considerably more books on this topic during his Cambridge years, though he may have sold them before moving to London in 1696. For its time, his was considered one of the finest alchemical libraries in the world. In his library, Newton left behind a heavily annotated personal copy of ''The Fame and Confession of the Fraternity R.C.'', by Thomas Vaughan which represents an English translation of The Rosicrucian Manifestos. Newton also possessed copies of '' Themis Aurea'' and '' Symbola Aurea Mensae Duodecium'' by the learned alchemist Michael Maier

Michael Maier (; 1568–1622) was a German physician and counsellor to Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor, Rudolf II Habsburg. He was a learned Alchemy, alchemist, epigramist, and amateur composer.

Early life

Maier was born in Rendsburg, Duchy of ...

, both of which are significant early books about the Rosicrucian movement. These books were also extensively annotated by Newton.

Newton's ownership of these materials by no means denotes membership within any early Rosicrucian order. Furthermore, considering that his personal alchemical investigations were focused upon discovering materials which the Rosicrucians professed to already be in possession of long before he was born, would seem to some to exclude Newton from their membership. During his own life, Newton was openly accused of being a Rosicrucian, as were many members of The Royal Society.

References

Further reading

* Dobbs, Betty Jo Teeter. ''The foundations of Newton's alchemy'' (Cambridge UP, 1983). * Iliffe, Rob. '' Priest of Nature: The Religious Worlds of Isaac Newton'' (Oxford UP, 2017), 536 pponline review

* Principe, Lawrence M. "Reflections on Newton's alchemy in light of the new historiography of alchemy." in J.E. Force and S Hutton, eds. ''Newton and Newtonianism'' (Springer, 2004) pp. 205–219

online

* Schilt, Cornelis J. ''Isaac Newton and the Study of Chronology: Prophecy, History, and Method'' (Amsterdam University Press, 2021). * White, Michael. ''Isaac Newton: The Last Sorcerer'' (1997). * *

External links

* *An archive of Newton's texts

*

Writings by Isaac Newton

* (Biblical interpretation, the architecture of the Jewish Temple, ancient history, alchemy and the Apocalypse). * * * *Writings about Newton

* * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Newton, IsaacOccult

The occult () is a category of esoteric or supernatural beliefs and practices which generally fall outside the scope of organized religion and science, encompassing phenomena involving a 'hidden' or 'secret' agency, such as magic and mysti ...

Alchemy

Hermeticism

Occult