Ireland–United Kingdom Relations on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ireland–United Kingdom relations are the

The separate Parliaments of

The separate Parliaments of

The Irish Free State had been governed, at least until 1936, under a form of constitutional monarchy linked to the United Kingdom. The King had a number of symbolically important duties, including exercising the executive (government), executive authority of the state, appointing the cabinet and promulgating the law. However, when Edward VIII proposed to marry Wallis Simpson, an American socialite and divorcée, in 1936, it caused a constitutional crisis across the

The Irish Free State had been governed, at least until 1936, under a form of constitutional monarchy linked to the United Kingdom. The King had a number of symbolically important duties, including exercising the executive (government), executive authority of the state, appointing the cabinet and promulgating the law. However, when Edward VIII proposed to marry Wallis Simpson, an American socialite and divorcée, in 1936, it caused a constitutional crisis across the

Today, the islands of Great Britain and

Today, the islands of Great Britain and

The

The

As a dominion of the

As a dominion of the

Many of the countries and regions of the isles, especially

Many of the countries and regions of the isles, especially

File:Irish embassy in London.JPG, Embassy of Ireland in London

File:British Embassy, Dublin.jpg, Embassy of the United Kingdom in Dublin

Irish Consulate, Edinburgh - 2025-04-19 02.jpg, Consulate General of Ireland in Edinburgh

online in English

* Doyle, John, and Eileen Connolly. "The Effects of Brexit on the Good Friday Agreement and the Northern Ireland Peace Process." in ''Peace, Security and Defence Cooperation in Post-Brexit Europe'' (Springer, Cham, 2019) pp. 79–95. * Edwards, Aaron, and Cillian McGrattan. ''The Northern Ireland conflict: a beginner's guide'' (Simon and Schuster, 2012). * Hammond, John L. ''Gladstone and the Irish nation'' (1938

online

* McLoughlin, P. J. "British–Irish relations and the Northern Ireland peace process: the importance of intergovernmentalism." in ''Dynamics of Political Change in Ireland'' (Routledge, 2016) pp. 103–118. * Mansergh, Nicholas. ''The Irish Question 1840–1921'' (3rd ed 1965

online

* Murphy, Mary C. "The Brexit crisis, Ireland and British–Irish relations: Europeanisation and/or de-Europeanisation?." ''Irish Political Studies'' 34.4 (2019): 530-550. * O'Kane, Eamonn. ''Britain, Ireland and Northern Ireland since 1980: the totality of relationships'' (Routledge, 2012). {{DEFAULTSORT:Ireland-United Kingdom relations Ireland–United Kingdom relations, Bilateral relations of Ireland, United Kingdom Bilateral relations of the United Kingdom Ireland and the Commonwealth of Nations Articles containing video clips

international relations

International relations (IR, and also referred to as international studies, international politics, or international affairs) is an academic discipline. In a broader sense, the study of IR, in addition to multilateral relations, concerns al ...

between the Republic of Ireland

Ireland ( ), also known as the Republic of Ireland (), is a country in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe consisting of 26 of the 32 Counties of Ireland, counties of the island of Ireland, with a population of about 5.4 million. ...

and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

. British rule in Ireland

British colonial rule in Ireland built upon the 12th-century Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland on behalf of the English king and eventually spanned several centuries that involved British control of parts, or the entirety, of the island of Irel ...

dates back to the Anglo-Norman invasion on behalf of the English king in the 12th century. Most of Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

gained independence from the United Kingdom following the Anglo-Irish War

The Irish War of Independence (), also known as the Anglo-Irish War, was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and British forces: the British Army, along wi ...

in the early 20th century.

Historically, relations between the two states have been influenced heavily by issues arising from the partition of Ireland

The Partition of Ireland () was the process by which the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (UK) divided Ireland into two self-governing polities: Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland (the area today known as the R ...

and the terms of Ireland's secession, its constitutional relationship with and obligations to the UK after independence, and the outbreak of political violence in Northern Ireland. Additionally, the high level of trade between the two states, their proximate geographic location, their common status as islands in the European Union until Britain's departure, common language and close cultural and personal links mean political developments in both states often closely follow each other.

Irish and British citizens are accorded equivalent reciprocal rights and entitlements (with a small number of minor exceptions), and a Common Travel Area

The Common Travel Area (CTA; , ) is an open borders area comprising the United Kingdom, Republic of Ireland, Ireland, the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands. The British Overseas Territories are not included. Governed by non-binding agreements ...

exists between Ireland, the United Kingdom, and the Crown Dependencies. The British–Irish Intergovernmental Conference acts as an official forum for co-operation between the Government of Ireland

The Government of Ireland () is the executive (government), executive authority of Republic of Ireland, Ireland, headed by the , the head of government. The government – also known as the cabinet (government), cabinet – is composed of Mini ...

and the Government of the United Kingdom

His Majesty's Government, abbreviated to HM Government or otherwise UK Government, is the central government, central executive authority of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

on matters of mutual interest generally, and with respect to Northern Ireland in particular. Two other bodies, the British–Irish Council

The British–Irish Council (BIC; ) is an intergovernmental organisation that aims to improve collaboration between its members in a number of areas including transport, the environment and energy. Its membership comprises Ireland, the United ...

and the British–Irish Parliamentary Assembly act as a forum for discussion between the executives and assemblies, respectively, of the region, including the devolved nations and regions in the UK and the three Crown dependencies. Co-operation between Northern Ireland and Ireland, including the execution of common policies in certain areas, occurs through the North/South Ministerial Council

The North/South Ministerial Council (NSMC) (, Ulster-Scots: ) is a body established under the Good Friday Agreement to co-ordinate activity and exercise certain governmental powers across the whole island of Ireland.

The Council takes the for ...

. In 2014, the UK Prime Minister David Cameron

David William Donald Cameron, Baron Cameron of Chipping Norton (born 9 October 1966) is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 2010 to 2016. Until 2015, he led the first coalition government in the UK s ...

, and the Irish Taoiseach Enda Kenny

Enda Kenny (born 24 April 1951) is an Irish former Fine Gael politician who served as Taoiseach from 2011 to 2017, Leader of Fine Gael from 2002 to 2017, Minister for Defence (Ireland), Minister for Defence from May to July 2014 and 2016 to 201 ...

described the relationship between the two countries as being at 'an all time high'.

Both Ireland and the United Kingdom joined the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are Geography of the European Union, located primarily in Europe. The u ...

(then the European Communities

The European Communities (EC) were three international organizations that were governed by the same set of Institutions of the European Union, institutions. These were the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), the European Atomic Energy Co ...

) in 1973. However, the three Crown dependencies remained outside of the EU. In June 2016, the UK held a referendum

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate (rather than their Representative democracy, representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either bin ...

in which a majority voted to leave the EU. Brexit

Brexit (, a portmanteau of "Britain" and "Exit") was the Withdrawal from the European Union, withdrawal of the United Kingdom (UK) from the European Union (EU).

Brexit officially took place at 23:00 GMT on 31 January 2020 (00:00 1 February ...

became effective on 31 January 2020, with a deal being reached on 24 December, keeping Northern Ireland in the European Union Single Market for goods and keeping a free border between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland. Relations between both sides became strained after the requested implementation of the Northern Ireland Protocol on 1 January 2021, which is strongly opposed by British citizens in Northern Ireland, the EU and the Irish government. Many Irish citizens in Northern Ireland saw Britain's withdrawal from the EU as a threat to the peace process and cross-border relations, especially as a majority of the NI electorate voted to remain in the EU. As a result of the tensions over the protocol, in February 2022, the DUP collapsed the Northern Ireland Assembly

The Northern Ireland Assembly (; ), often referred to by the metonym ''Stormont'', is the devolved unicameral legislature of Northern Ireland. It has power to legislate in a wide range of areas that are not explicitly reserved to the Parliam ...

and Executive

Executive ( exe., exec., execu.) may refer to:

Role or title

* Executive, a senior management role in an organization

** Chief executive officer (CEO), one of the highest-ranking corporate officers (executives) or administrators

** Executive dir ...

in protest, seeking a renegotiation of the deal. Consequently, Northern Ireland was left without a devolved executive government until February 2024, when the DUP re-entered following modifications to the protocol. This allowed a new NI Executive to be elected, with Michelle O'Neill of Sinn Fein becoming First Minister, alongside Emma Little-Pengelly

Emma Little-Pengelly ( Little; born 31 December 1979) is a Northern Irish barrister and Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) politician

serving as the First Minister and deputy First Minister of Northern Ireland, deputy First Minister of Northern ...

of the DUP as deputy First Minister.

The three devolved administrations of the United Kingdom in Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

, Wales

Wales ( ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by the Irish Sea to the north and west, England to the England–Wales border, east, the Bristol Channel to the south, and the Celtic ...

and Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ; ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, part of the United Kingdom in the north-east of the island of Ireland. It has been #Descriptions, variously described as a country, province or region. Northern Ireland shares Repub ...

, and the three dependencies of the British Crown

The Crown is a political concept used in Commonwealth realms. Depending on the context used, it generally refers to the entirety of the State (polity), state (or in federal realms, the relevant level of government in that state), the executive ...

, the Isle of Man

The Isle of Man ( , also ), or Mann ( ), is a self-governing British Crown Dependency in the Irish Sea, between Great Britain and Ireland. As head of state, Charles III holds the title Lord of Mann and is represented by a Lieutenant Govern ...

, Jersey

Jersey ( ; ), officially the Bailiwick of Jersey, is an autonomous and self-governing island territory of the British Islands. Although as a British Crown Dependency it is not a sovereign state, it has its own distinguishing civil and gov ...

and Guernsey

Guernsey ( ; Guernésiais: ''Guernési''; ) is the second-largest island in the Channel Islands, located west of the Cotentin Peninsula, Normandy. It is the largest island in the Bailiwick of Guernsey, which includes five other inhabited isl ...

, also participate in multilateral bodies created between the two states, such as the British Irish Council and the British-Irish Parliamentary Assembly.

Country comparison

History

There have been relations between the people inhabiting theBritish Isles

The British Isles are an archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner Hebrides, Inner and Outer Hebr ...

since the earliest recorded history of the region. A Romano-Briton, Patricius, later known as Saint Patrick

Saint Patrick (; or ; ) was a fifth-century Romano-British culture, Romano-British Christian missionary and Archbishop of Armagh, bishop in Gaelic Ireland, Ireland. Known as the "Apostle of Ireland", he is the primary patron saint of Irelan ...

, brought Christianity to Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

and, following the fall of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

, missionaries from Ireland re-introduced Christianity to Britain.

The expansion of Gaelic culture into what became known as Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

(after the Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

''Scoti

''Scoti'' or ''Scotti'' is a Latin name for the Gaels,Duffy, Seán. ''Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia''. Routledge, 2005. p.698 first attested in the late 3rd century. It originally referred to all Gaels, first those in Ireland and then those ...

'', meaning Gaels) brought close political and familial ties between people in Ireland and people in Great Britain, lasting from the early Middle Ages to the 17th century, including a common Gaelic language

The Goidelic ( ) or Gaelic languages (; ; ) form one of the two groups of Insular Celtic languages, the other being the Brittonic languages.

Goidelic languages historically formed a dialect continuum stretching from Ireland through the Isle o ...

spoken on both islands. Norse-Gaels in the Kingdom of Dublin

The Kingdom of Dublin (Old Norse: ''Dyflin'') was a Norse kingdom in Ireland that lasted from roughly 853 AD to 1170 AD. It was the first and longest-lasting Norse kingdom in Ireland, founded by Vikings who invaded the territory around Dublin ...

and Norman invasion of Ireland

The Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland took place during the late 12th century, when Anglo-Normans gradually conquered and acquired large swathes of land in Ireland over which the monarchs of England then claimed sovereignty. The Anglo-Normans ...

added religious, political, economic and social ties between Northumbria and Wales with Leinster in the Pale

The Pale ( Irish: ''An Pháil'') or the English Pale (' or ') was the part of Ireland directly under the control of the English government in the Late Middle Ages. It had been reduced by the late 15th century to an area along the east coast s ...

, the Isle of Man

The Isle of Man ( , also ), or Mann ( ), is a self-governing British Crown Dependency in the Irish Sea, between Great Britain and Ireland. As head of state, Charles III holds the title Lord of Mann and is represented by a Lieutenant Govern ...

and Galloway

Galloway ( ; ; ) is a region in southwestern Scotland comprising the counties of Scotland, historic counties of Wigtownshire and Kirkcudbrightshire. It is administered as part of the council areas of Scotland, council area of Dumfries and Gallow ...

, including Hiberno-English

Hiberno-English or Irish English (IrE), also formerly sometimes called Anglo-Irish, is the set of dialects of English native to the island of Ireland. In both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland, English is the first language in e ...

.

During the Tudor dynasty

The House of Tudor ( ) was an English and Welsh dynasty that held the throne of England from 1485 to 1603. They descended from the Tudors of Penmynydd, a Welsh noble family, and Catherine of Valois. The Tudor monarchs ruled the Kingdom of Eng ...

, the English regained control and in 1541 Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his Wives of Henry VIII, six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. ...

was crowned King of Ireland

Monarchical systems of government have existed in Ireland from ancient times. This continued in all of Ireland until 1949, when the Republic of Ireland Act removed most of Ireland's residual ties to the British monarch. Northern Ireland, as p ...

. The English Reformation

The English Reformation began in 16th-century England when the Church of England broke away first from the authority of the pope and bishops Oath_of_Supremacy, over the King and then from some doctrines and practices of the Catholic Church ...

in the 1500s increased the antagonism between England and Ireland, as the Irish remained Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

, which became a justification for the English to oppress the Irish. In Ireland, during the Tudor and Stuart eras, the English Crown initiated a large-scale colonization of Ireland with Protestant settlers from Britain, particularly in the province of Ulster

Ulster (; or ; or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional or historic provinces of Ireland, Irish provinces. It is made up of nine Counties of Ireland, counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kingdom); t ...

. These settlers became the economically and politically dominant land-owning class that would dominate Ireland for centuries. In reaction, there were a number of anti-English rebellions, such as the Desmond Rebellions

The Desmond Rebellions occurred in 1569–1573 and 1579–1583 in the Irish province of Munster. They were rebellions by the Earl of Desmond, the head of the FitzGerald dynasty in Munster, and his followers, the Geraldines and their allies, ...

and the Nine Years' War

The Nine Years' War was a European great power conflict from 1688 to 1697 between Kingdom of France, France and the Grand Alliance (League of Augsburg), Grand Alliance. Although largely concentrated in Europe, fighting spread to colonial poss ...

.

1600s

War

War is an armed conflict between the armed forces of states, or between governmental forces and armed groups that are organized under a certain command structure and have the capacity to sustain military operations, or between such organi ...

and colonisation

475px, Map of the year each country achieved List of sovereign states by date of formation, independence.

Colonization (British English: colonisation) is a process of establishing occupation of or control over foreign territories or peoples f ...

made Ireland completely subject to growing British colonial powers in the early 1600s. Forced settlement of newly conquered land and inequitable laws defined life for the Irish under British rule. England had previously conquered Scotland and Wales, leaving many people from western Scotland to seek opportunity in settling about 500,000 acres of newly seized land in Ireland. Some Irish people were displaced to an attempted "reservation". This resulted in Gaelic ties between Scotland and Ireland withering dramatically over the course of the 17th century, including a divergence in the Gaelic language into two distinct languages.

In 1641, the Irish were finally able to drive out the English for a short time through a successful rebellion and proclaim the Irish Catholic Confederation, which was allied with the Royalists in the English Civil War

The English Civil War or Great Rebellion was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Cavaliers, Royalists and Roundhead, Parliamentarians in the Kingdom of England from 1642 to 1651. Part of the wider 1639 to 1653 Wars of th ...

. Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in British history. He came to prominence during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, initially ...

succeeded in reconquering Ireland by brutal methods and by 1652 all of Ireland was under English control. Cromwell then granted land in Ireland to his followers and the Catholic aristocracy in Ireland was increasingly dispossessed. Cromwell exiled numerous Catholics to Connacht

Connacht or Connaught ( ; or ), is the smallest of the four provinces of Ireland, situated in the west of Ireland. Until the ninth century it consisted of several independent major Gaelic kingdoms (Uí Fiachrach, Uí Briúin, Uí Maine, C ...

and up to 40 percent of Ireland's population died as a result of the English invasion. The defeat of the Jacobites at the Battle of the Boyne

The Battle of the Boyne ( ) took place in 1690 between the forces of the deposed King James II, and those of King William III who, with his wife Queen Mary II (his cousin and James's daughter), had acceded to the Crowns of England and Sc ...

in 1690 further reinforced the Protestant Ascendancy

The Protestant Ascendancy (also known as the Ascendancy) was the sociopolitical and economical domination of Ireland between the 17th and early 20th centuries by a small Anglicanism, Anglican ruling class, whose members consisted of landowners, ...

in Ireland.

1782–1918

Although Ireland gained near-independence from Great Britain in 1782, there were revolutionary movements in the 1790s that favoured France, Britain's great enemy.Secret societies

A secret society is an organization about which the activities, events, inner functioning, or membership are concealed. The society may or may not attempt to conceal its existence. The term usually excludes covert groups, such as intelligence a ...

staged the failed 1798 Rebellion. Therefore the kingdoms of Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

and Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

were merged in 1801 to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was the union of the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland into one sovereign state, established by the Acts of Union 1800, Acts of Union in 1801. It continued in this form until ...

.

On 1 January 1801, Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

and Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

joined to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was the union of the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland into one sovereign state, established by the Acts of Union 1800, Acts of Union in 1801. It continued in this form until ...

. The Act of Union 1800 was passed in both the Parliament of Great Britain and the Parliament of Ireland, dominated by the Protestant Ascendancy and lacking representation of the country's Roman Catholic population. Substantial majorities were achieved, and according to contemporary documents this was assisted by bribery in the form of the awarding of peerage

A peerage is a legal system historically comprising various hereditary titles (and sometimes Life peer, non-hereditary titles) in a number of countries, and composed of assorted Imperial, royal and noble ranks, noble ranks.

Peerages include:

A ...

s and honours

Honour (Commonwealth English) or honor (American English; see spelling differences) is a quality of a person that is of both social teaching and personal ethos, that manifests itself as a code of conduct, and has various elements such as valo ...

to opponents to gain their votes. The separate Parliaments of

The separate Parliaments of Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

and Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

were now abolished, and replaced by a united Parliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, and may also legislate for the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace ...

. Ireland thus became an integral part of the United Kingdom, sending around 100 MPs to the House of Commons at Westminster and 28 Irish representative peers to the House of Lords, elected from among their number by the Irish peers themselves, except that Roman Catholic peers were not permitted to take their seats in the Lords. Part of the trade-off for the Irish Catholics was to be the granting of Catholic Emancipation, which had been fiercely resisted by the all-Anglican Irish Parliament. However, this was blocked by King George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland, Ireland from 25 October 1760 until his death in 1820. The Acts of Union 1800 unified Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and ...

, who argued that emancipating the Roman Catholics would breach his Coronation Oath. The Roman Catholic hierarchy had endorsed the Union. However the decision to block Catholic Emancipation fatally undermined the appeal of the Union. The slow emancipation of Catholics in Ireland began later the early 1800s.

British oppression led to increasing impoverishment and depopulation of Ireland (the island had still not returned to its 1800 population by the early 21st century). Between 1845 and 1849, Ireland experienced a great famine caused by potato blight. However, the British government, in keeping with its laissez-faire ideology, refused to intervene and help the Irish. Also, grain from Ireland continued to be exported abroad, exacerbating the famine. One million Irish died and many emigrated. Ireland's demographics never recovered from this, as large numbers of Irish continued to move away (mainly to the US). The famine and its aftermath led to lasting bitterness in Ireland and increased the desire for self-determination

Self-determination refers to a people's right to form its own political entity, and internal self-determination is the right to representative government with full suffrage.

Self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international la ...

.

In 1873, the Home Rule League

The Home Rule League (1873–1882), sometimes called the Home Rule Party, was an Irish political party which campaigned for home rule for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, until it was replaced by the Irish Parliam ...

was formed, which sought Irish Home Rule

The Home Rule movement was a movement that campaigned for self-government (or "home rule") for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was the dominant political movement of Irish nationalism from 1870 to the end of ...

. After another famine in 1879, the Irish Land League

The Irish National Land League ( Irish: ''Conradh na Talún''), also known as the Land League, was an Irish political organisation of the late 19th century which organised tenant farmers in their resistance to exactions of landowners. Its prima ...

was formed, which opposed the oppression of the Irish peasantry. The struggle for Irish self-determination was also supported by the Irish diaspora in the United States, where the militant Fenian Brotherhood attacked British North America

British North America comprised the colonial territories of the British Empire in North America from 1783 onwards. English colonisation of North America began in the 16th century in Newfoundland, then further south at Roanoke and Jamestown, ...

. Irish nationalists in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

exerted increasing pressure on British policy. In 1886 and 1893, two Irish Home Rule Bills

The Home Rule movement was a movement that campaigned for self-government (or "home rule") for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was the dominant political movement of Irish nationalism from 1870 to the end of ...

were defeated in Parliament because British conservatives, together with Anglo-Irish Protestants, rejected Irish self-determination. Some concessions had to be made, however, such as land reforms in 1903 and 1909. Irish nationalism only strengthened as a result and in 1905 the militant Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( ; ; ) is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active in both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The History of Sinn Féin, original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur Griffit ...

was founded by Arthur Griffith

Arthur Joseph Griffith (; 31 March 1871 – 12 August 1922) was an Irish writer, newspaper editor and politician who founded the political party Sinn Féin. He led the Irish delegation at the negotiations that produced the 1921 Anglo-Irish Trea ...

, which advocated secession from the British Empire by any means necessary.

In the 1910s, a political crisis arose in Ireland between supporters of Home Rule and its opponents, consisting of the Protestants in Ulster (Northern Ireland). In 1914, the Government of Ireland Act was finally passed, promising self-government for Ireland, but implementation had to be postponed with the start of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. In 1916, the Easter Rising

The Easter Rising (), also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed insurrection in Ireland during Easter Week in April 1916. The Rising was launched by Irish republicans against British rule in Ireland with the aim of establishing an ind ...

in Ireland saw an attempt to force Irish independence by force. The uprising was violently put down by the British, with Dublin devastated.

Independence 1919–1922

After World War I, violent and constitutional campaigns forautonomy

In developmental psychology and moral, political, and bioethical philosophy, autonomy is the capacity to make an informed, uncoerced decision. Autonomous organizations or institutions are independent or self-governing. Autonomy can also be ...

or independence culminated in an election in 1918 returning almost 70% of seats to Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( ; ; ) is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active in both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The History of Sinn Féin, original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur Griffit ...

, who declared Irish independence from Britain and set up a parliament in Dublin, and declared the independence of Ireland from the United Kingdom. A war of independence

Wars of national liberation, also called wars of independence or wars of liberation, are conflicts fought by nations to gain independence. The term is used in conjunction with wars against foreign powers (or at least those perceived as foreign) ...

followed that ended with the Anglo-Irish Treaty

The 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty (), commonly known in Ireland as The Treaty and officially the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland, was an agreement between the government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain an ...

of 1921, which partitioned Ireland between the Irish Free State

The Irish Free State (6 December 192229 December 1937), also known by its Irish-language, Irish name ( , ), was a State (polity), state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-ye ...

, which gained dominion status

A dominion was any of several largely self-governing countries of the British Empire, once known collectively as the ''British Commonwealth of Nations''. Progressing from colonies, their degrees of colonial self-governance increased (and, in ...

within the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

, and a devolved administration in Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ; ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, part of the United Kingdom in the north-east of the island of Ireland. It has been #Descriptions, variously described as a country, province or region. Northern Ireland shares Repub ...

, which remained part of the UK. In 1937, Ireland declared itself fully independent of the United Kingdom and became a Republic

A republic, based on the Latin phrase ''res publica'' ('public affair' or 'people's affair'), is a State (polity), state in which Power (social and political), political power rests with the public (people), typically through their Representat ...

.

Post-independence conflicts

Boundary commission

The day after the establishment of theIrish Free State

The Irish Free State (6 December 192229 December 1937), also known by its Irish-language, Irish name ( , ), was a State (polity), state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-ye ...

, the Houses of the Parliament of Northern Ireland

The Parliament of Northern Ireland was the home rule legislature of Northern Ireland, created under the Government of Ireland Act 1920, which sat from 7 June 1921 to 30 March 1972, when it was suspended because of its inability to restore ord ...

resolved to make an address to the King so as to opt out of the Irish Free State Immediately afterwards, the need to settle an agreed border between the Irish Free State and Northern Ireland arose. In response to this issue a commission was set up involving representatives from the Government of the Irish Free State, the Government of Northern Ireland

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government is a ...

, and the Government of the United Kingdom

His Majesty's Government, abbreviated to HM Government or otherwise UK Government, is the central government, central executive authority of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

which would chair the Commission. Ultimately and after some controversy, the present border was fixed, not by the Commission but by agreement between the United Kingdom (including Northern Ireland) and the Irish Free State.

Anglo-Irish Trade War

A further dispute arose in 1930 over the issue of the Irish government's refusal to reimburse the United Kingdom with "land annuities". These annuities were derived from government financedsoft loan

A soft loan is a loan with a below-market rate of interest. This is also known as ''soft financing''. Sometimes, soft loans provide other concessions to borrowers, such as long repayment periods or interest holidays. Soft loans are usually provi ...

s given to Irish tenant farmers before independence to allow them to buy out their farms from landlords (see Irish Land Acts

The Land Acts (officially Land Law (Ireland) Acts) were a series of measures to deal with the question of tenancy contracts and peasant proprietorship of land in Ireland in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Five such acts were introduced by ...

). These loans were intended to redress the issue of landownership in Ireland arising from the wars of the 17th century. The refusal of the Irish government to pass on monies it collected from these loans to the British government led to a retaliatory and escalating trade war

A trade war is an economic conflict often resulting from extreme protectionism, in which states raise or implement tariffs or other trade barriers against each other as part of their commercial policies, in response to similar measures imposed ...

between the two states from 1932 until 1938, a period known as the Anglo-Irish Trade War or the Economic War.

While the UK was less affected by the Economic War, the Irish economy was virtually crippled by the resulting capital flight

Capital flight, in economics, is the rapid flow of assets or money out of a country, due to an event of economic consequence or as the result of a political event such as regime change or economic globalization. Such events could be erratic or ...

. Unemployment was extremely high and the effects of the Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

compounded the difficulties. The government urged people to support the confrontation with the UK as a national hardship to be shared by every citizen. Pressures, especially from agricultural producers in Ireland and exporters in the UK, led to an agreement between the two governments in 1938 resolving the dispute.

Many infant industries were established during this "economic war". Almost complete import substitution was achieved in many sectors behind a protective tariff barrier. These industries proved valuable during the war years as they reduced the need for imports.

Under the terms of resulting Anglo-Irish Trade Agreement, all duties imposed during the previous five years were lifted but Ireland was still entitled to impose tariffs on British imports to protect new Irish "infant" industries. Ireland was to pay a one-off £10 million sum to the United Kingdom (as opposed to annual repayments of £250,000 over 47 more years). Arguably the most significant outcome, however, was the return of so-called "Treaty Ports

Treaty ports (; ) were the port cities in China and Japan that were opened to foreign trade mainly by the unequal treaties forced upon them by Western powers, as well as cities in Korea opened up similarly by the Qing dynasty of China (before th ...

", three ports in Ireland maintained by the UK as sovereign bases under the terms of the Anglo-Irish Treaty

The 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty (), commonly known in Ireland as The Treaty and officially the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland, was an agreement between the government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain an ...

. The handover of these ports facilitated Irish neutrality during World War II

The policy of neutral country, neutrality was adopted by Ireland's Oireachtas at the instigation of the Taoiseach Éamon de Valera upon the outbreak of World War II in Europe. It was maintained throughout the conflict, in spite of Bombing of Du ...

, and made it much harder for Britain to ensure the safety of the Atlantic Conveys.

Articles 2 and 3 and the name ''Ireland''

Ireland adopted a new constitution in 1937. This declared Ireland to be a sovereign, independent state, but did not explicitly declare Ireland to be a republic. However, it did change the name of the state from ''Irish Free State'' to ''Ireland'' (or in the Irish language). It also containedirredentist

Irredentism () is one state's desire to annex the territory of another state. This desire can be motivated by ethnic reasons because the population of the territory is ethnically similar to or the same as the population of the parent state. Hist ...

claims on Northern Ireland, stating that the "national territory f the Irish stateconsists of the whole island of Ireland" (Article 2). This was measured in some way by Article 3, which stated that, "Pending the re-integration of the national territory ... the laws enacted by the parliament f Irelandshall have the like area and extent of application as the laws of Saorstat Éireann" ( is the Irish language name of the Irish Free State

The Irish Free State (6 December 192229 December 1937), also known by its Irish-language, Irish name ( , ), was a State (polity), state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-ye ...

).

The United Kingdom initially accepted the change in the name to ''Ireland''. However, it subsequently changed its practice and passed legislation providing that the Irish state could be called ''Eire ''(notably without a ) in British law. For some time, the United Kingdom was supported by some other Commonwealth countries

The Commonwealth of Nations, often referred to as the British Commonwealth or simply the Commonwealth, is an international association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire from which i ...

. However, by the mid-1960s, ''Ireland'' was the accepted diplomatic name of the Irish state.

During the Troubles

The Troubles () were an ethno-nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland that lasted for about 30 years from the late 1960s to 1998. Also known internationally as the Northern Ireland conflict, it began in the late 1960s and is usually deemed t ...

, the disagreement led to request for extradition of terrorist suspects to be struck invalid by the Supreme Court of Ireland unless the name ''Ireland'' was used. Increasingly positive relations between the two states required the two states to explore imaginative work-arounds to the disagreement. For example, while the United Kingdom would not agree to refer to Mary Robinson as ''President of Ireland'' on an official visit to Queen Elizabeth II (the first such visit in the two states' history), they agreed to refer to her instead as "President Robinson of Ireland".

As a consequence of the Northern Ireland peace process, Articles 2 and 3 were changed in 1999 formalising shared Irish and British citizenship in Northern Ireland, removing the irredentist claim and making provisions for common "[institutions] with executive powers and functions ... in respect of all or any part of the island."

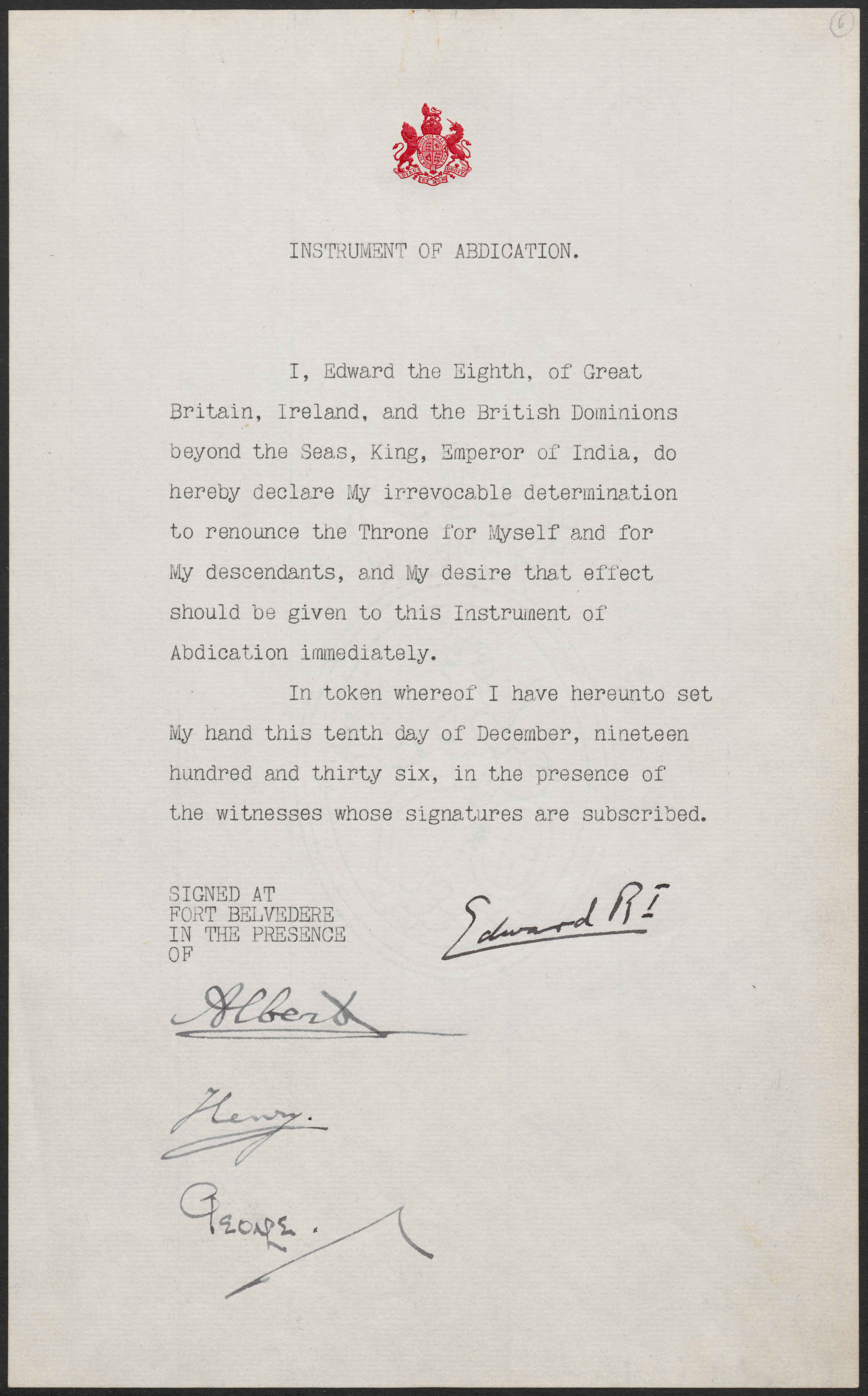

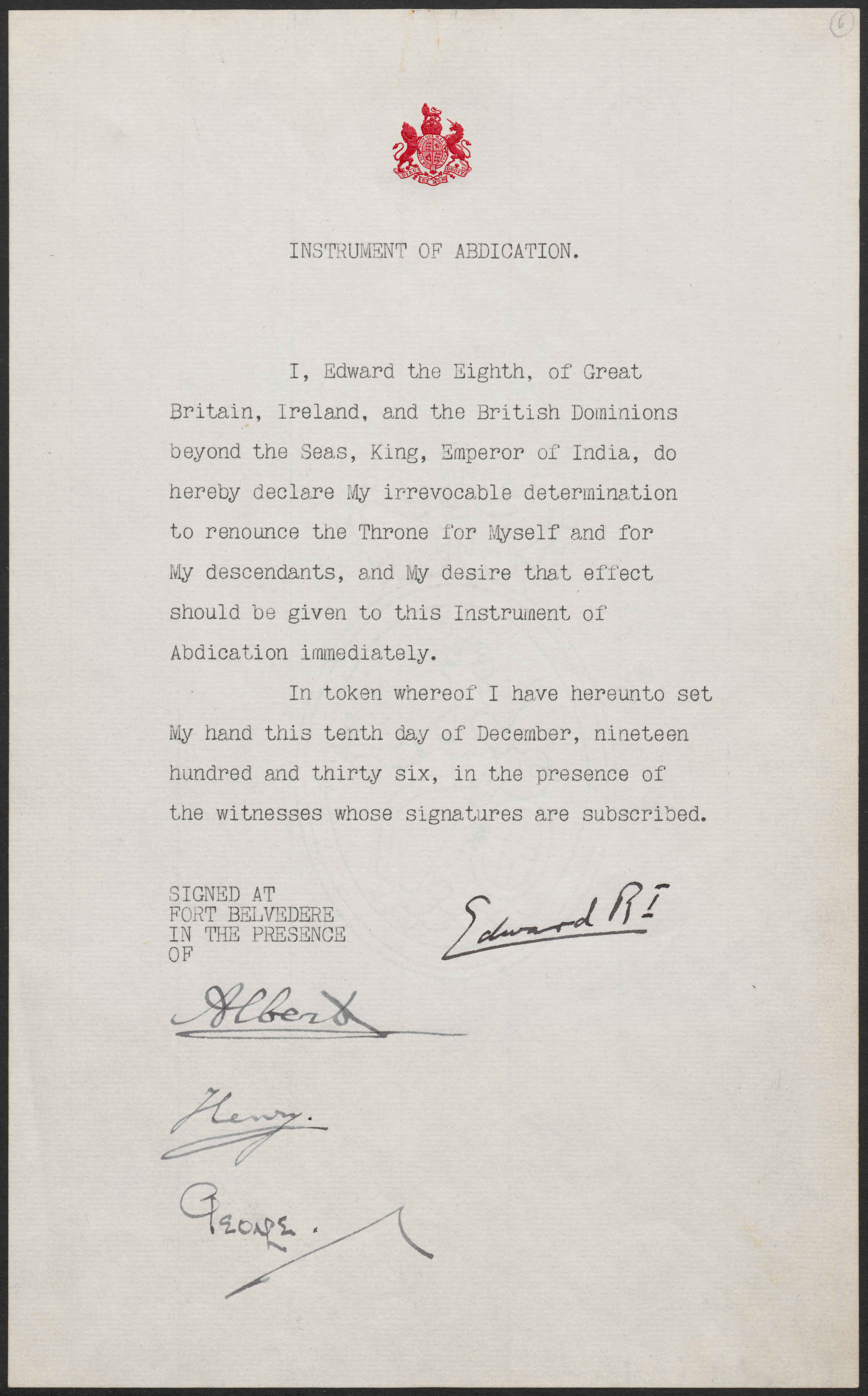

Abdication crisis and the Republic of Ireland Act

The Irish Free State had been governed, at least until 1936, under a form of constitutional monarchy linked to the United Kingdom. The King had a number of symbolically important duties, including exercising the executive (government), executive authority of the state, appointing the cabinet and promulgating the law. However, when Edward VIII proposed to marry Wallis Simpson, an American socialite and divorcée, in 1936, it caused a constitutional crisis across the

The Irish Free State had been governed, at least until 1936, under a form of constitutional monarchy linked to the United Kingdom. The King had a number of symbolically important duties, including exercising the executive (government), executive authority of the state, appointing the cabinet and promulgating the law. However, when Edward VIII proposed to marry Wallis Simpson, an American socialite and divorcée, in 1936, it caused a constitutional crisis across the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

. In the chaos that ensued his abdication, the Irish Free State took the opportunity to amend its constitution and remove all of the functions of the King except one: that of representing the state abroad.

In 1937, Constitution of Ireland, a new constitution was adopted which entrenched the monarch's diminished role by transferring many of the functions performed by the King until 1936 to a new office of the President of Ireland, who was declared to "take precedence over all other persons in the State". However, the 1937 constitution did not explicitly declare that the state was a republic, nor that the President was head of state. Without explicit mention, the King continued to retain his role in external relations and the Irish Free State continued to be regarded as a member of the British Commonwealth and to be associated with the United Kingdom.

During the period from December 1936 to April 1949, it was unclear whether or not the Irish state was a republic or a form of constitutional monarchy and (from 1937) whether its head of state was the President of Ireland (Douglas Hyde until 1945, and Seán T. O'Kelly afterwards) or the King of Ireland

Monarchical systems of government have existed in Ireland from ancient times. This continued in all of Ireland until 1949, when the Republic of Ireland Act removed most of Ireland's residual ties to the British monarch. Northern Ireland, as p ...

(George VI of the United Kingdom, George VI). The exact constitutional status of the state during this period has been a matter of scholarly and political dispute.

The state's ambiguous status ended in 1949, when the Republic of Ireland Act 1948, Republic of Ireland Act stripped the King of his role in external relations and declared that the state may be described as the ''Republic of Ireland''. The decision to do so was sudden and unilateral. However, it did not result in greatly strained relations between Ireland and the United Kingdom. The question of the head of the Irish state from 1936 to 1949 was largely a matter of symbolism and had little practical significance. The UK response was to legislate that it would not grant Northern Ireland to the Irish state without the consent of the Parliament of Northern Ireland

The Parliament of Northern Ireland was the home rule legislature of Northern Ireland, created under the Government of Ireland Act 1920, which sat from 7 June 1921 to 30 March 1972, when it was suspended because of its inability to restore ord ...

(which was unlikely to happen in Unionism in Ireland, unionist-majority Northern Ireland).

One practical implication of explicitly declaring the state to be a republic in 1949 was that it automatically terminated the state's membership of the British Commonwealth, in accordance with the rules in operation at the time. However, despite this, the United Kingdom legislated that Irish citizens would retain similar rights to Commonwealth subjects and were not to be regarded as foreigners.

The Republic of Ireland Act came into force on 18 April 1949. Ten days later, 28 April 1949, the rules of the Commonwealth of Nations were changed through the London Declaration so that, when India declared itself a republic, it would not have to leave. The prospect of Ireland rejoining the Commonwealth, even today, is still occasionally raised but has never been formally considered by the Irish government.

Toponyms

A minor, though recurring, source of antagonism between Britain and Ireland is the name of the archipelago in which they both are located. Known as the ''British Isles'' in Britain, this name is opposed by most in Ireland and its use is objected to by the Irish Government. A spokesman for the Irish Embassy in London recently said, "The British Isles has a dated ring to it, as if we are still part of the Empire. We are independent, we are not part of Britain, not even in geographical terms. We would discourage its usage .". No consensus on another name for the islands exists. In practice, the two Governments and the shared institutions of the archipelago avoid use of the term, frequently using the more appropriate term ''these islands'' in place of any term.The Troubles

Political violence broke out in Northern Ireland in 1968 following clashes over a civil rights campaign. The civil rights campaign demanding an end to institutionalised discrimination against Irish nationalism, nationalists by the Unionism in Ireland, unionist Government of Northern Ireland. As the violence escalated, 1969 Northern Ireland riots, rioting and attacks by nationalist and unionist groups began to de-stabilise the province and required the presence of Operation Banner, British troops on the ground. In the wake of the riots, theRepublic of Ireland

Ireland ( ), also known as the Republic of Ireland (), is a country in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe consisting of 26 of the 32 Counties of Ireland, counties of the island of Ireland, with a population of about 5.4 million. ...

expressed its concern about the situation. In a televised broadcast, Taoiseach Jack Lynch stated that the Irish Government could "no longer stand by" while hundreds of people were being injured. This was interpreted as a threat of military intervention. While Exercise Armageddon, a plan for an Irish invasion of Northern Ireland was rejected by the Government of Ireland, a secret Irish government fund of £100,000 was dedicated to helping refugees from the violence. Some more actively nationalist Irish Ministers were tried in 1970 when it emerged that most of the fund had been Arms Crisis, spent covertly on buying arms for nationalists.

Angry crowds burned down the Embassy of the United Kingdom, Dublin, British Embassy in Dublin in protest at the shooting by British troops of 13 civilians in Derry, Northern Ireland on Bloody Sunday (1972) and in 1981 protesters tried to storm the British Embassy in response to the IRA hunger strikes of that year. In 1978, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) trial ''Ireland v. the United Kingdom'' ruled that the techniques used in interrogating prisoners in Northern Ireland "amounted to a practice of inhuman or degrading treatment, inhuman and degrading treatment", in breach of the European Convention on Human Rights.

Throughout the conflict, the Republic of Ireland was primarily crucial for the Provisional Irish Republican Army campaign, IRA campaign against British troops and Ulster_loyalism#Paramilitary_and_vigilante_groups, loyalist paramilitaries. Irish historian Gearóid Ó Faoleán wrote for ''The Irish Times'' that "[t]hroughout the country, Irish republicanism, republicans were as much a part of their communities as any others. Many were involved in the Gaelic Athletic Association, GAA or other local organisations and their neighbours could, to paraphrase [Irish writer Tim Pat Coogan, Tim Pat] Coogan, quietly and approvingly mutter about the 'boys' – and then go off without a qualm the next day to vote for a political party aggressively opposed to the IRA." Shannon Airport and Cork Harbour, Cork and Cobh harbours were used extensively by the Provisional Irish Republican Army arms importation, IRA for arms importation overseas during the early 1970s aided by sympathetic workers on-site. Most IRA training camps were located in the republic, as did safe houses and arms factories. The vast majority of the finances used in the IRA campaign came from criminal and legitimate activities in the Republic of Ireland rather than overseas sources. Large numbers of improvised explosive devices and firearms were manufactured by IRA members and supporters in Southern Ireland and then transported into Northern Ireland and England for use against targets in these regions. For example, one IRA arms factory near Stannaway Road, Dublin, was producing six firearms a day in 1973. An arms factory in the County Dublin village of Donabate in 1975 was described as "a centre for the manufacture of grenades, rockets and mortars." Gelignite stolen from quarries, farms and construction sites in the Republic was behind the 48,000lbs of explosives detonated in Northern Ireland in the first six months of 1973 alone. IRA training ranged from basic small arms and explosives manufacturing to heavy machine guns, overseen by Southern Irish citizens, including a former member of the Defence Forces (Ireland), Irish Defence Forces. Thousands of Irish citizens in the Republic joined the IRA throughout the conflict; for example, the assassination of Louis Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma, assassination of Louis Mountbatten in August 1979 was carried out by IRA member Thomas McMahon (Irish republican), Thomas McMahon from Monaghan.

An attempt by the two governments to resolve the conflict in Northern Ireland politically in 1972 through the Sunningdale Agreement failed due to opposition by hard-line factions in Northern Ireland. With no resolution to the conflict in sight, the Irish government established the New Ireland Forum in 1984 to look into solutions. While the British Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher rejected the forum's proposals, it informed the British government's opinion and it is said to have given the Irish Taoiseach Garret FitzGerald a Mandate (politics), mandate during the negotiation of the 1985 Anglo-Irish Agreement, which was directed at resolving the conflict. The 1992 Downing Street Declaration further consolidated the views of the two Governments and the 1998 Good Friday Agreement eventually formed the basis for peace in the province.

The Irish Department of Foreign Affairs established a "Reconciliation Fund" in 1982 to support organisations whose work tends to improve cross-community or North–South relations. Since 2006, the Minister for Foreign Affairs and Trade, Minister for Foreign Affairs has hosted an annual "Reconciliation Networking Forum" (sometimes called the "Reconciliation Forum"; not to be confused with the Forum for Peace and Reconciliation) in Dublin to which such groups are invited.

Brexit

There is Irish border question, a controversy about the impact that Britain's withdrawal from the European Union will have at the end of the transition period on the border between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland, in particular the impact it may have on the economy and people of the island were customs or immigration checks to be put in place at the border. It was prioritized as one of the three most important areas to resolve in order to reach the Withdrawal Agreement, Agreement on the withdrawal of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland from the European Union. The people of the UK voted to leave the European Union in a non-binding 2016 United Kingdom European Union membership referendum, referendum on 23 June 2016, an act which would effectively make the Republic of Ireland-Northern Ireland border an External border of the European Union, external EU border. Due to the lack of supporting legislation, all referendums in the UK are not legally binding, which was confirmed by a Supreme Court judge in November 2016. Nevertheless, the UK government chose to proceed with the departure from the European Union. All parties have stated that they want to avoid a hard border in Ireland particularly due to the sensitive nature of the border. The border issue is concerned by a protocol related to the withdrawal agreement, known as the Irish backstop, Protocol on Ireland and Northern Ireland.Good Friday Agreement

The conflict in Northern Ireland, as well as dividing both Governments, paradoxically also led to increasingly closer co-operation and improved relations between Ireland and the United Kingdom. A 1981 meeting between the two governments established the Anglo-Irish Intergovernmental Council. This was further developed in 1985 under the Anglo-Irish Agreement whereby the two governments created the Anglo-Irish Intergovernmental Conference, under the Anglo-Irish Intergovernmental Council, as a regular forum for the two Governments to reach agreement on, "(i) political matters; (ii) security and related matters; (iii) legal matters, including the administration of justice; (iv) the promotion of cross-border co-operation." The Conference was "mainly concerned with Northern Ireland; but some of the matters under consideration will involve cooperative action in both parts of the island of Ireland, and possibly also in Great Britain." The Agreement also recommended the establishment of the Anglo-Irish Interparliamentary Body, a body where parliamentarians from the Houses of the Oireachtas (Ireland) and Houses of Parliament (United Kingdom) would regularly meet to share views and ideas. This was created in 1990 as the British–Irish Inter-Parliamentary Body. The Northern Ireland peace process culminated in the Good Friday Agreement of 1998 that further developed the institutions established under these Anglo-Irish Agreement. New institutions were established interlocking across "strands": * Strand I: an Assembly and Executive for Northern Ireland based on the D'Hondt method, D'Hondt system; * Strand II: aNorth/South Ministerial Council

The North/South Ministerial Council (NSMC) (, Ulster-Scots: ) is a body established under the Good Friday Agreement to co-ordinate activity and exercise certain governmental powers across the whole island of Ireland.

The Council takes the for ...

to develop co-operation and common policies within the island of Ireland;

* Strand III:

*# a British–Irish Council

The British–Irish Council (BIC; ) is an intergovernmental organisation that aims to improve collaboration between its members in a number of areas including transport, the environment and energy. Its membership comprises Ireland, the United ...

"to promote the harmonious and mutually beneficial development of the totality of relationships among the peoples of these islands"

*# a new British–Irish Intergovernmental Conference, established under the British–Irish Agreement, replaced the Anglo-Irish Intergovernmental Council and the Anglo-Irish Intergovernmental Conference.

The scope of the British–Irish Intergovernmental Conference is broader that the original Conference, and is intended to "bring together the British and Irish Governments to promote bilateral co-operation at all levels on all matters of mutual interest within the competence of both Governments." The Conference also provides a joint institution for the government of Northern Ireland on non-devolved matters (or all matters when the Northern Ireland Assembly is suspended). However, the United Kingdom retains ultimate sovereignty over Northern Ireland. Representatives from Northern Ireland participate in the Conference when matters relating to Northern Ireland are concerned.

The members of the British–Irish Council (sometimes called the ''Council of the Isles'') are representatives of the Irish and British Governments, the devolved administrations in Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales, together with representatives of the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands. It meets regularly to discuss matters of mutual interest divided into work areas (such as energy, environment or housing) allocated to individual members to work and report on.

The Anglo-Irish Interparliamentary Body developed independently over the same period, eventually becoming known as the British–Irish Parliamentary Assembly and including members from the devolved administrations of the UK and the Crown Dependencies.

The development of these institutions was supported by acts such the visit of efforts by Mary Robinson (as President of Ireland) to the Queen Elizabeth II (Queen of the United Kingdom), an apology by Tony Blair (as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom) to Irish people for the failures of the British Government during the Great Famine (Ireland), Great Famine of 1845—1852 and the creation of the Island of Ireland Peace Park. A Queen Elizabeth II's visit to the Republic of Ireland, state visit of Queen Elizabeth II to Ireland in May 2011 – including the laying of a wreath at a memorial to Irish Republican Army, IRA fighters in the Anglo-Irish war – symbolically sealed the change in relationships between the two states following the transfer of police and justice powers to Northern Ireland. The visit came a century after her grandfather, King George V, was the last monarch of the United Kingdom to pay a state visit to Ireland in July 1911, while it was still part of the United Kingdom.

Political landscape

Today, the islands of Great Britain and

Today, the islands of Great Britain and Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

contain two sovereign states: Republic of Ireland, Ireland (alternatively described as the ''Republic of Ireland'') and the United Kingdom, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. The United Kingdom comprises four countries of the United Kingdom. All but Northern Ireland have been independent states at one point.

There are also three Crown dependencies, Guernsey

Guernsey ( ; Guernésiais: ''Guernési''; ) is the second-largest island in the Channel Islands, located west of the Cotentin Peninsula, Normandy. It is the largest island in the Bailiwick of Guernsey, which includes five other inhabited isl ...

, Jersey

Jersey ( ; ), officially the Bailiwick of Jersey, is an autonomous and self-governing island territory of the British Islands. Although as a British Crown Dependency it is not a sovereign state, it has its own distinguishing civil and gov ...

and the Isle of Man

The Isle of Man ( , also ), or Mann ( ), is a self-governing British Crown Dependency in the Irish Sea, between Great Britain and Ireland. As head of state, Charles III holds the title Lord of Mann and is represented by a Lieutenant Govern ...

, in the archipelago which are not part of the United Kingdom, although the United Kingdom maintains responsibility for certain affairs such as international affairs and ensuring good governance, on behalf of the British crown, and can legislate directly for them. These participate in the shared institutions created between Ireland and the United Kingdom under the Good Friday Agreement. The United Kingdom and the Crown dependencies form what are called the ''British Islands''.

The devolved administrations of the United Kingdom and the three Crown Dependencies also participate in the shared institutions established under the Good Friday Agreement.

The British monarch was head of state of all of these states and countries of the archipelago from the Union of the Crowns in 1603 until their role in Ireland became ambiguous with the enactment of the Constitution of Ireland in 1937. The remaining functions of the monarch in Ireland were transferred to the President of Ireland, with coming into effect of the Republic of Ireland Act in 1949.

Academic perspectives

Several academic perspectives are important in the study and understanding of Ireland–United Kingdom relations. Important strands of scholarship include research on identity, especially Britishness and Irishness, and studies of the major political movements, such as separatism, Unionism in the United Kingdom, unionism and nationalism. The concept of post-nationalism is also contemporary trend in studies of history, culture and politics in the isles.Co-operation

The British–Irish Intergovernmental Conference provides for co-operation between the Government of Ireland and the Government of the United Kingdom on all matters of mutual interest for which they have competence. Meetings take the form of Summit (meeting), summits between the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and the Irish Taoiseach, on an "as required" basis. Otherwise, the two governments are represented by the appropriate ministers. In light of Ireland's particular interest in the governance of Northern Ireland, "regular and frequent" meetings co-chaired by the Irish Minister for Foreign Affairs and the UK Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, dealing with non-devolved matters to do with Northern Ireland and non-devolved all-Ireland issues, are required to take place under the establishing treaty. At these meetings, the Irish government may put forward views and proposals, however sovereignty over Northern Ireland remains with the United Kingdom. In all of the work of the Conference, "All decisions will be by agreement between both Governments [who] will make determined efforts to resolve disagreements between them." The Conference is supported by a standing secretariat located at Belfast, Northern Ireland, dealing with non-devolved matters affecting Northern Ireland.'All-islands' institutions

The British–Irish Council (BIC) is an international organisation laid out under the Belfast Agreement in 1998 and created by the established by the two Governments in 1999. Its members are: * the two Sovereign state, sovereign governments of Republic of Ireland, Ireland and the United Kingdom; * the three devolved administrations inNorthern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ; ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, part of the United Kingdom in the north-east of the island of Ireland. It has been #Descriptions, variously described as a country, province or region. Northern Ireland shares Repub ...

, Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

and Wales

Wales ( ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by the Irish Sea to the north and west, England to the England–Wales border, east, the Bristol Channel to the south, and the Celtic ...

* the three governments of the Crown dependencies of Guernsey

Guernsey ( ; Guernésiais: ''Guernési''; ) is the second-largest island in the Channel Islands, located west of the Cotentin Peninsula, Normandy. It is the largest island in the Bailiwick of Guernsey, which includes five other inhabited isl ...

, the Isle of Man

The Isle of Man ( , also ), or Mann ( ), is a self-governing British Crown Dependency in the Irish Sea, between Great Britain and Ireland. As head of state, Charles III holds the title Lord of Mann and is represented by a Lieutenant Govern ...

and Jersey

Jersey ( ; ), officially the Bailiwick of Jersey, is an autonomous and self-governing island territory of the British Islands. Although as a British Crown Dependency it is not a sovereign state, it has its own distinguishing civil and gov ...

.

The Council formally came into being on 2 December 1999. Its stated aim is to "promote the harmonious and mutually beneficial development of the totality of relationships among the peoples of these islands". The BIC has a standing secretariat, located in Edinburgh, Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

, and meets in bi-annual summits and regular sectoral meetings. Summit meetings are attended by the heads of each administrations (e.g. the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom) whereas sectoral meetings are attended by the relevant Government minister, ministers form each administration.

While the Council is made up of representatives from the executive of the various administrations in the region, it does not have executive power itself. Instead, its decisions, so far as they exist, are implemented separately by each administration on the basis of consensus. Given this – that the Council has no means to force its member administrations into implementing programmes of action – the Council has been dismissed as a "talking shop" and its current role appears to be one mainly of "information exchange and consultation".

In addition to the Council, the British–Irish Parliamentary Assembly (BIPA) is composed of members of the legislative bodies in the United Kingdom, including the devolved legislatures, Republic of Ireland, Ireland, and the British crown dependency, Crown dependencies. It is the older of the two 'all-islands' institutions (BIC and BIPA) having been founded in 1990 as the British–Irish Inter-Parliamentary Body. Its purpose is to foster common understanding between elected representatives from these jurisdictions and, while having no legislative power, it conducts parliamentary activities such as receiving oral submissions, preparing reports and debating topical issues. The Assembly meets in plenary on a bi-annual basis, alternating in venue between Britain and Ireland, and maintains on-going work in committee.

These institutions have been described as part of a confederation, confederal approach to the government of the British–Irish archipelago.

All-Ireland institutions

The

The North/South Ministerial Council

The North/South Ministerial Council (NSMC) (, Ulster-Scots: ) is a body established under the Good Friday Agreement to co-ordinate activity and exercise certain governmental powers across the whole island of Ireland.

The Council takes the for ...

(NSMC) coordinates activity and exercises certain governmental functions across the island of Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

. The Council is responsible for developing and executing policy in at least twelve areas of co-operation, of which:

* at least six are executed separately in each jurisdiction

* at least six are executed by an all-Ireland "implementation body"

Further development of the role and function of the Council are possible "with the specific endorsement of the Northern Ireland Assembly and Oireachtas, subject to the extent of the competences and responsibility of the two Administrations."

The North/South Ministerial Council and the Northern Ireland Assembly are defined in the Good Friday Agreement as being "mutually inter-dependent, and that one cannot successfully function without the other." Participation in the Council is a requisite for the operation of the Northern Ireland Assembly and participation in the Northern Ireland Executive. When devolution in Northern Ireland is suspended, the powers of the Northern Ireland Executive revert to the British–Irish Intergovernmental Conference.

Meetings of the Council take the form of "regular and frequent" sectoral meetings between ministers from the Government of Ireland

The Government of Ireland () is the executive (government), executive authority of Republic of Ireland, Ireland, headed by the , the head of government. The government – also known as the cabinet (government), cabinet – is composed of Mini ...

and the Northern Ireland Executive. Plenary meetings, attended by all ministers and led by the First Minister and deputy First Minister and the Taoiseach, take place twice a year. Institutional and cross-sectoral meetings, including matters in relation to the EU or to resolved disagreements, happen "in an appropriate format" on a ''ad hoc'' basis. The Council has a permanent office located in Armagh, Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ; ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, part of the United Kingdom in the north-east of the island of Ireland. It has been #Descriptions, variously described as a country, province or region. Northern Ireland shares Repub ...

, staffed by a standing secretariat.

There is no joint parliamentary forum for the island of Ireland. However, under the Good Friday Agreement, the Oireachtas and Northern Ireland Assembly are asked to consider developing one. The Agreement also contains a suggestion for the creation of a consultative forum composed of members of civil society from Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. Under the 2007, St. Andrew's Agreement, the Northern Ireland Executive agreed to support the establishment of a North/South Consultative Forum and to encourage parties in the Northern Ireland Assembly to support the creation of a North/South parliamentary forum.

Inter-regional relationships

Independent of the direct involvement of Government of the United Kingdom, the devolved administrations of the mainland United Kingdom and the Crown dependencies also have relationships and with Ireland. For example, the Irish and Welsh governments collaborate on various economic development projects through the Ireland Wales Programme, under the Interreg initiative of the European Union. The governments of Ireland and Scotland, together with the Northern Ireland Executive, also collaborated on the ISLES project under the aegis of the Special EU Programmes Body, set up under the Good Friday Agreement. The project was to facilitate the development of offshore renewable energy sources, such as Wind power, wind, Wave power, wave and Tidal power, tidal energy, and trade in renewable energy betweenScotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

, the Republic of Ireland

Ireland ( ), also known as the Republic of Ireland (), is a country in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe consisting of 26 of the 32 Counties of Ireland, counties of the island of Ireland, with a population of about 5.4 million. ...

and Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ; ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, part of the United Kingdom in the north-east of the island of Ireland. It has been #Descriptions, variously described as a country, province or region. Northern Ireland shares Repub ...

.

Common Travel Area

Ireland is the only Member state of the European Union, member state in the European Union not obliged to join the Schengen Area, Schengen free-travel area (The United Kingdom also had an opt out from joining prior to its withdrawal from the bloc in 2020). Instead, aCommon Travel Area

The Common Travel Area (CTA; , ) is an open borders area comprising the United Kingdom, Republic of Ireland, Ireland, the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands. The British Overseas Territories are not included. Governed by non-binding agreements ...

exists between the two states and the Crown Dependencies (which were never part of the EU, thus never obliged to join Schengen).