Independence Of Jamaica on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The

The

The

The Colony of Jamaica

The Crown Colony of Jamaica and Dependencies was a British colony from 1655, when it was Invasion of Jamaica (1655), captured by the The Protectorate, English Protectorate from the Spanish Empire. Jamaica became a British Empire, British colon ...

gained independence from the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

on 6 August 1962. In Jamaica

Jamaica is an island country in the Caribbean Sea and the West Indies. At , it is the third-largest island—after Cuba and Hispaniola—of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean. Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, west of Hispaniola (the is ...

, this date is celebrated as Independence Day, a national holiday.

History up to independence

Indigenous origins

TheCaribbean

The Caribbean ( , ; ; ; ) is a region in the middle of the Americas centered around the Caribbean Sea in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, mostly overlapping with the West Indies. Bordered by North America to the north, Central America ...

island now known as Jamaica was settled first by hunter-gatherers from the Yucatán and then by two waves of Taino people from South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a considerably smaller portion in the Northern Hemisphere. It can also be described as the southern Subregion#Americas, subregion o ...

. Genoan explorer Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus (; between 25 August and 31 October 1451 – 20 May 1506) was an Italians, Italian explorer and navigator from the Republic of Genoa who completed Voyages of Christopher Columbus, four Spanish-based voyages across the At ...

arrived in Jamaica in 1494 during his second voyage to the New World

The term "New World" is used to describe the majority of lands of Earth's Western Hemisphere, particularly the Americas, and sometimes Oceania."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: ...

, and claimed it for Crown of Castile

The Crown of Castile was a medieval polity in the Iberian Peninsula that formed in 1230 as a result of the third and definitive union of the crowns and, some decades later, the parliaments of the kingdoms of Kingdom of Castile, Castile and Kingd ...

. At this time, over two hundred villages existed in Jamaica, largely located on the south coast and ruled by ''caciques,'' or "chiefs of villages".

Spanish rule

TheSpanish Empire

The Spanish Empire, sometimes referred to as the Hispanic Monarchy (political entity), Hispanic Monarchy or the Catholic Monarchy, was a colonial empire that existed between 1492 and 1976. In conjunction with the Portuguese Empire, it ushered ...

began its official rule in Jamaica in 1509, with formal occupation of the island by conquistador

Conquistadors (, ) or conquistadores (; ; ) were Spanish Empire, Spanish and Portuguese Empire, Portuguese colonizers who explored, traded with and colonized parts of the Americas, Africa, Oceania and Asia during the Age of Discovery. Sailing ...

Juan de Esquivel and his men. The Spaniards enslaved many of the native people, overworking and harming them to the point that many perished within fifty years of European arrival. Subsequently, the Spanish Empire’s continuing need for labor was no longer filled by the capacity of the surviving indigenous population. Spanish colonialists adapted by turning to the trade in enslaved Africans. Disappointed by the lack of gold on the island, the Spanish mainly used Jamaica as a military base

A military base is a facility directly owned and operated by or for the military or one of its branches that shelters military equipment and personnel, and facilitates training and operations. A military base always provides accommodations for ...

to supply colonizing efforts in the mainland Americas.

British colony

After 146 years of Spanish rule, a large group of British sailors and soldiers landed in theKingston Harbour

Kingston Harbour in Jamaica is the seventh-largest natural harbour in the world. It is an almost landlocked area of water approximately long by wide. Most of it is deep enough to accommodate large ships, even close to shore. It is bordered to th ...

on 10 May 1655, during the Anglo-Spanish War. The English, who had set their sights on Jamaica after a disastrous defeat in an earlier attempt to take the island of Hispaniola

Hispaniola (, also ) is an island between Geography of Cuba, Cuba and Geography of Puerto Rico, Puerto Rico in the Greater Antilles of the Caribbean. Hispaniola is the most populous island in the West Indies, and the second-largest by List of C ...

, marched toward Villa de la Vega, the administrative center of the island. Spanish forces surrendered without much fight on 11 May, many of them fleeing to Spanish Cuba or the northern portion of the island.

British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

colonial jurisdiction over the island was quickly established, with the newly renamed Spanish Town

Spanish Town (Jamaican Patois: Spain) is the capital and the largest town in the Parishes of Jamaica, parish of St. Catherine, Jamaica, St. Catherine in the historic county of Middlesex, Jamaica, Middlesex, Jamaica. It was the Spanish and Briti ...

named the capital and home of the local House of Assembly, Jamaica's directly elected legislature.

Rebellions and brewing nationalism

Jamaican Maroons

The Anglo-Spanish war afforded the opportunity to escape slavery to people enslaved by Spanish colonizers, and many fled into the mountainous and forested regions of the colony to join the ranks of surviving Tainos. Asinterracial marriage

Interracial marriage is a marriage involving spouses who belong to different "Race (classification of human beings), races" or Ethnic group#Ethnicity and race, racialized ethnicities.

In the past, such marriages were outlawed in the United Sta ...

became extremely prevalent, the two racial groups underwent assimilation. The formerly enslaved and their descendants, known as the Jamaican Maroons

Jamaican Maroons descend from Africans who freed themselves from slavery in the Colony of Jamaica and established communities of Free black people in Jamaica, free black people in the island's mountainous interior, primarily in the eastern Pari ...

, were the source of many disturbances in the colony, raiding plantations and occupying parts of the island's interior. Imported African slaves would frequently escape to Maroon territory, known as Cockpit Country. Over the first seventy-six years of British rule, skirmishes between Maroon warriors and the British colonial militia grew increasingly common, along with rebellions by enslaved Blacks.

These conflicts culminated in 1728, when the First Maroon War began between the English and Maroons. Largely owing to the easily defendable, dense forest of Cockpit Country, the British were unsuccessful in defeating the Maroons. Following negotiations, the Maroons were granted semi-autonomy within their five towns, living under a British supervisor and their native leader.

In 1795, tensions between the Maroons of Cudjoe's Town (Trelawny Town) and the British erupted into the Second Maroon War. The conflict ended on a less favorable term for Maroons, with a bloody stalemate reigning over the island for five months. Following the killings of plantation owners and their families and the release of slaves by the Maroons, Major-General George Walpole planned to trap the Maroons in Trelawney Town via the use of armed posts and bloodhound

The bloodhound is a large scent hound, originally bred for hunting deer, wild boar, rabbits, and since the Middle Ages, for tracking people. Believed to be descended from hounds once kept at the Abbey of Saint-Hubert, Belgium, in French it is ...

s, pushing them to accept peace terms in early January 1796. Fearing British victory, the Maroons accepted open discussions in March. This delay was used as a pretext to have the large majority of the Trelawney Maroons deported to Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada, located on its east coast. It is one of the three Maritime Canada, Maritime provinces and Population of Canada by province and territory, most populous province in Atlan ...

. They were later moved to Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone, officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered to the southeast by Liberia and by Guinea to the north. Sierra Leone's land area is . It has a tropical climate and envi ...

.

Garvey

Slavery was abolished in the British Empire by the Slavery Abolition Act in 1834. Following a period of intense debate, the native and African populace of Jamaica were granted the right to vote; as the 19th century continued the government allowed some of them to holdpublic office

Public administration, or public policy and administration refers to "the management of public programs", or the "translation of politics into the reality that citizens see every day",Kettl, Donald and James Fessler. 2009. ''The Politics of the ...

. Despite these accomplishments, the white members of Jamaican colonial society continued to hold the real power.

During the first half of the 20th century the most notable Black leader was Marcus Garvey

Marcus Mosiah Garvey Jr. (17 August 188710 June 1940) was a Jamaican political activist. He was the founder and first President-General of the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League (UNIA-ACL) (commonly known a ...

, a labour leader and advocate of Black nationalism

Black nationalism is a nationalist movement which seeks representation for Black people as a distinct national identity, especially in racialized, colonial and postcolonial societies. Its earliest proponents saw it as a way to advocate for ...

. Garvey, rather than advocating independence of Jamaica and other colonies, promoted the Back-to-Africa movement

The back-to-Africa movement was a political movement in the 19th and 20th centuries advocating for a return of the descendants of African American slaves to Sub-Saharan Africa in the African continent. The small number of freed slaves who did ...

, which called for everyone of African descent

Black is a racial classification of people, usually a political and skin color-based category for specific populations with a mid- to dark brown complexion. Not all people considered "black" have dark skin and often additional phenotypical ...

to return to the homelands of their ancestors. Garvey, to no avail, pleaded with the colonial government to improve living conditions for indigenous peoples in the West Indies

The West Indies is an island subregion of the Americas, surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, which comprises 13 independent island country, island countries and 19 dependent territory, dependencies in thr ...

. Upon returning from international travels, he founded the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League in 1914, which promoted civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' political freedom, freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and ...

for blacks in Jamaica and abroad. Garvey served a five-year prison sentence at the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary for defrauding investors in the league, following which he was deported to Jamaica in November 1927, after having his sentence commuted by President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

Calvin Coolidge

Calvin Coolidge (born John Calvin Coolidge Jr.; ; July 4, 1872January 5, 1933) was the 30th president of the United States, serving from 1923 to 1929. A Republican Party (United States), Republican lawyer from Massachusetts, he previously ...

. After returning to his place of birth, Garvey tried and failed to be elected into public office. The latter defeat is attributed to his followers lacking the proper voter qualifications. Despite these shortcomings, Marcus Garvey is regarded as a national hero in present-day Jamaica.

Party politics

The spike of nationalist sentiment in colonial Jamaica is primarily attributed to the British West Indian labour unrest of 1934–39, which protested the inequalities of wealth between native and British residents of theBritish West Indies

The British West Indies (BWI) were the territories in the West Indies under British Empire, British rule, including Anguilla, the Cayman Islands, the Turks and Caicos Islands, Montserrat, the British Virgin Islands, Bermuda, Antigua and Barb ...

. Through these popular opinions Alexander Bustamante, a White native-born moneylender

In finance, a loan is the tender of money by one party to another with an agreement to pay it back. The recipient, or borrower, incurs a debt and is usually required to pay interest for the use of the money.

The document evidencing the debt ( ...

, rose to political prominence and founded the Bustamante Industrial Trade Union. Bustamante advocated autonomy of the island, and a more equal balance of power. He captured the attention and admiration of many black Jamaican youths with his passionate speeches on behalf of Jamaican workers. After a waterfront protest in September 1940, he was arrested by colonial authorities and remained incarcerated for the better part of two years.

As Bustamante Industrial Trade Union gained support, a cousin of Alexander Bustamante's, Norman Manley, founded the People's National Party

The People's National Party (PNP) (PNP; ) is a Social democracy, social democratic List of political parties in Jamaica, political party in Jamaica, founded in 1938 by Norman Manley, Norman Washington Manley who served as party president unti ...

(PNP), a democratic socialist

Democratic socialism is a left-wing economic and political philosophy that supports political democracy and some form of a socially owned economy, with a particular emphasis on economic democracy, workplace democracy, and workers' self-mana ...

movement which also advocated trade unions. Although Bustamante was originally a founding member of the PNP, he resigned from his position there in 1939, citing its socialist

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

tendencies as "too radical."

In July 1943, Bustamante launched the Jamaica Labour Party (JLP), which his opponents brushed aside as just a political label of Bustamante Industrial Trade Union. In the following elections, the JLP defeated the PNP with an 18-point lead over the latter in the House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entities. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often ...

.

The following year, the JLP led government enacted a new constitution that granted universal adult suffrage

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise is the right to vote in public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in English, the right to v ...

, undoing the high voter eligibility standards put in place by British. The new constitution, which was made official on 20 November 1944, established a bicameral legislature

Bicameralism is a type of legislature that is divided into two separate assemblies, chambers, or houses, known as a bicameral legislature. Bicameralism is distinguished from unicameralism, in which all members deliberate and vote as a single ...

and organised an Executive Council made up of ten members of the legislature and chaired by the newly created position of Premier

Premier is a title for the head of government in central governments, state governments and local governments of some countries. A second in command to a premier is designated as a deputy premier.

A premier will normally be a head of govern ...

, the head of government. A checks and balances

The separation of powers principle functionally differentiates several types of state power (usually law-making, adjudication, and execution) and requires these operations of government to be conceptually and institutionally distinguishabl ...

system was also established for this council.

Path to independence, 1945–1962

AsWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

came to a close, a sweeping movement of decolonization

Decolonization is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby Imperialism, imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. The meanings and applications of the term are disputed. Some scholar ...

overtook the world. British Government and local politicians began a long transition of Jamaica from a crown colony

A Crown colony or royal colony was a colony governed by Kingdom of England, England, and then Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain or the United Kingdom within the English overseas possessions, English and later British Empire. There was usua ...

into an independent state. The political scene was dominated by PNP and JLP, with the houses of legislature switching hands between the two throughout the 1950s.

After Norman Manley was elected Chief Minister in 1955, he sped up the process of decolonisation via several constitutional amendments. These amendments allowed for greater self-government

Self-governance, self-government, self-sovereignty or self-rule is the ability of a person or group to exercise all necessary functions of regulation without intervention from an external authority. It may refer to personal conduct or to any ...

and established a cabinet of ministers under a Prime Minister of Jamaica

The prime minister of Jamaica () is Jamaica's head of government, currently Andrew Holness. Holness, as leader of the governing Jamaica Labour Party (JLP), was sworn in as prime minister on 7 September 2020, having been re-elected as a result ...

.

Under Manley, Jamaica entered the West Indies Federation

The West Indies Federation, also known as the West Indies, the Federation of the West Indies or the West Indian Federation, was a short-lived political union that existed from 3 January 1958 to 31 May 1962. Various islands in the Caribbean th ...

, a political union

A political union is a type of political entity which is composed of, or created from, smaller politics or the process which achieves this. These smaller polities are usually called federated states and federal territories in a federal gove ...

of colonial Caribbean islands that, if it had survived, would have united ten British colonial territories into a single, independent state. Jamaica's participation in the Federation was unpopular, and the results of the 1961 West Indies referendum held by Premier Manley cemented the colony's withdrawal from the union in 1962. The West Indies Federation collapsed later that year following the departure of Trinidad and Tobago

Trinidad and Tobago, officially the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago, is the southernmost island country in the Caribbean, comprising the main islands of Trinidad and Tobago, along with several List of islands of Trinidad and Tobago, smaller i ...

.

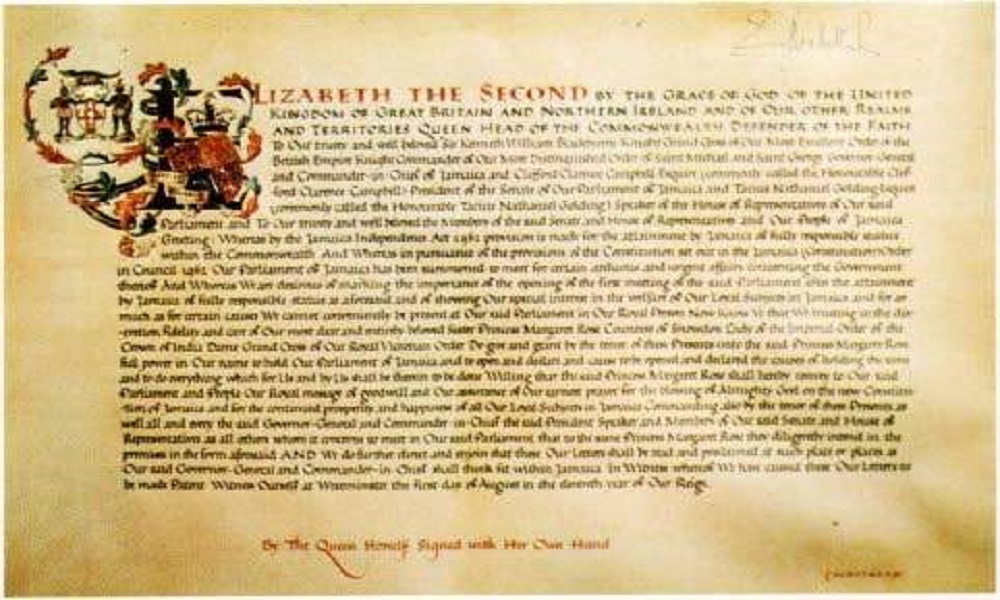

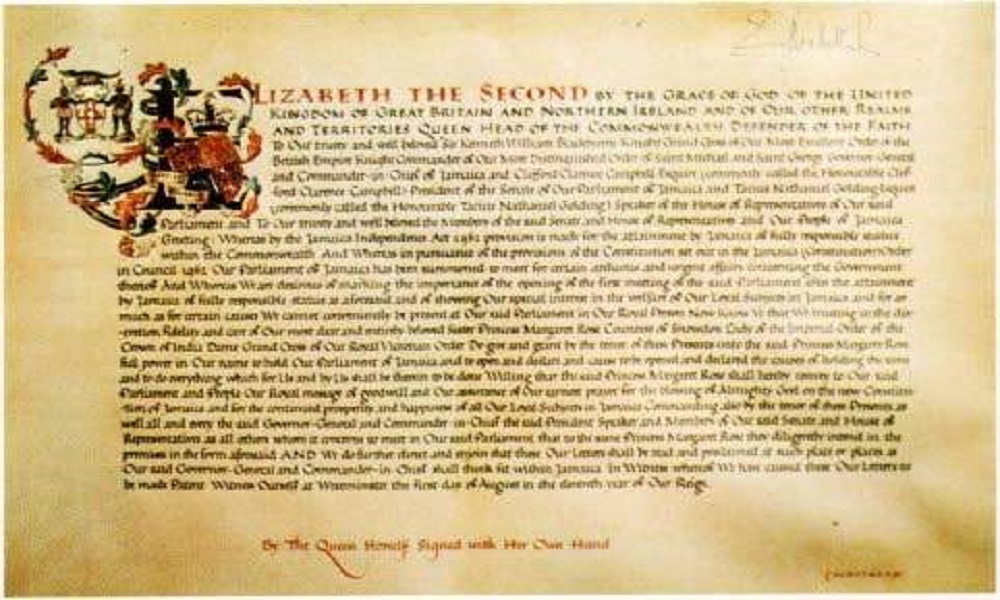

Independence

In the elections of 1962, the JLP defeated the PNP, resulting in the ascension of Sir Alexander Bustamante to the premiership in April of that year. On 19 July 1962, theParliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, and may also legislate for the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace ...

passed the Jamaica Independence Act, granting independence as of 6 August with The Queen as Head of State. On that day, the Union Jack

The Union Jack or Union Flag is the ''de facto'' national flag of the United Kingdom. The Union Jack was also used as the official flag of several British colonies and dominions before they adopted their own national flags.

It is sometimes a ...

was ceremonially lowered and replaced by the Jamaican flag throughout the country. Princess Margaret

Princess Margaret, Countess of Snowdon (Margaret Rose; 21 August 1930 – 9 February 2002) was the younger daughter of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother. She was the younger sister and only sibling of Queen Elizabeth II.

...

opened the first session of the Parliament of Jamaica

The Parliament of Jamaica () is the legislature, legislative branch of the government of Jamaica. Officially, they are known as the Houses of Parliament. It consists of three elements: The Monarchy of Jamaica, Crown (represented by the Govern ...

on behalf of The Queen.

With the independence of Jamaica, the Cayman Islands

The Cayman Islands () is a self-governing British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory, and the largest by population. The territory comprises the three islands of Grand Cayman, Cayman Brac and Little Cayman, which are located so ...

reverted from being a self-governing territory of Jamaica to direct British rule.

Since independence

Sir Alexander Bustamante became the firstPrime Minister of Jamaica

The prime minister of Jamaica () is Jamaica's head of government, currently Andrew Holness. Holness, as leader of the governing Jamaica Labour Party (JLP), was sworn in as prime minister on 7 September 2020, having been re-elected as a result ...

and joined the Commonwealth of Nations

The Commonwealth of Nations, often referred to as the British Commonwealth or simply the Commonwealth, is an International organization, international association of member states of the Commonwealth of Nations, 56 member states, the vast majo ...

, an organisation of ex-British territories. Today, Jamaica continues to be a Commonwealth realm

A Commonwealth realm is a sovereign state in the Commonwealth of Nations that has the same constitutional monarch and head of state as the other realms. The current monarch is King Charles III. Except for the United Kingdom, in each of the re ...

, with the British monarch

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the form of government used by the United Kingdom by which a hereditary monarch reigns as the head of state, with their powers regulated by the British con ...

, Charles III, remaining as King of Jamaica and head of state

A head of state is the public persona of a sovereign state.#Foakes, Foakes, pp. 110–11 "

.

Jamaica spent its first ten years of independence under conservative governments, with its economy undergoing continuous growth. However, as it had been throughout much of its history, the independent Jamaica was plagued by issues of class inequality. After the he head of state

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (letter), the fifth letter of the Semitic abjads

* He (pronoun), a pronoun in Modern English

* He (kana), one of the Japanese kana (へ in hiragana and ヘ in katakana)

* Ge (Cyrillic), a Cyrillic letter cal ...

being an embodiment of the State itself or representative of its international persona." The name given to the office of head of sta ...global economy

The world economy or global economy is the economy of all humans in the world, referring to the global economic system, which includes all economic activities conducted both within and between nations, including production, consumption, econ ...

underwent deterioration, the leftist PNP returned to power after the 1972 elections. Uncertain economic conditions troubled the country well into the 1980s.

Michael Manley

Michael Norman Manley (10 December 1924 – 6 March 1997) was a Jamaican politician who served as the fourth prime minister of Jamaica, from 1972 to 1980, and from 1989 to 1992. Manley championed a democratic socialist program, and has been ...

, the son of Norman Manley, who led what was largely the opposition party throughout the development of independent Jamaica, went on to become the fourth Prime Minister of Jamaica and maintained the People's National Party's status as one of two major political factions of the country.

Colonial legacy

While independence is widely celebrated within Jamaican society, it has become a subject of debate. In 2011, a survey showed that approximately 60% of Jamaicans "think the country would be better off today if it was still under British rule", citing years of social and fiscal mismanagement in the country.References

{{Jamaica year nav 1962 in Jamaica Independence movements Politics of Jamaica History of the Colony of Jamaica History of the Commonwealth of Nations Jamaica and the Commonwealth of Nations Foundations of countries