Immurement on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Immurement (; ), also called immuration or live entombment, is a form of

Immurement (; ), also called immuration or live entombment, is a form of

According to Finnish legend, a young maiden was wrongfully immured into the castle wall of

According to Finnish legend, a young maiden was wrongfully immured into the castle wall of  In the ruins of Thornton Abbey,

In the ruins of Thornton Abbey,  The actual punishment meted out to men found guilty of paederasty might vary between different status groups. In 1409 and 1532 in

The actual punishment meted out to men found guilty of paederasty might vary between different status groups. In 1409 and 1532 in

In Catholic monastic tradition, there existed a type of enforced, solitary confinement for nuns or monks who had broken their vows of chastity, or espoused heretical ideas. Henry Charles Lea offers an example:

Indeed, the punitive function of was that of perpetual seclusion. The guilty were condemned not to starve to death quickly, but to ''live'' in utter isolation from other human beings. As Lea describes in a footnote to this case:

Meanwhile, Sir

In Catholic monastic tradition, there existed a type of enforced, solitary confinement for nuns or monks who had broken their vows of chastity, or espoused heretical ideas. Henry Charles Lea offers an example:

Indeed, the punitive function of was that of perpetual seclusion. The guilty were condemned not to starve to death quickly, but to ''live'' in utter isolation from other human beings. As Lea describes in a footnote to this case:

Meanwhile, Sir

Immurement (; ), also called immuration or live entombment, is a form of

Immurement (; ), also called immuration or live entombment, is a form of imprisonment

Imprisonment or incarceration is the restraint of a person's liberty for any cause whatsoever, whether by authority of the government, or by a person acting without such authority. In the latter case it is considered " false imprisonment". Impri ...

, usually until death, in which someone is placed within an enclosed space without exits. This includes instances where people have been enclosed in extremely tight confinement, such as within a coffin

A coffin or casket is a funerary box used for viewing or keeping a corpse, for burial, entombment or cremation. Coffins are sometimes referred to as caskets, particularly in American English.

A distinction is commonly drawn between "coffins" a ...

. When used as a means of execution

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence ordering that an offender be punished in ...

, the prisoner is simply left to die from starvation

Starvation is a severe deficiency in caloric energy intake, below the level needed to maintain an organism's life. It is the most extreme form of malnutrition. In humans, prolonged starvation can cause permanent organ damage and eventually, de ...

or dehydration

In physiology, dehydration is a lack of total body water that disrupts metabolic processes. It occurs when free water loss exceeds intake, often resulting from excessive sweating, health conditions, or inadequate consumption of water. Mild deh ...

. This form of execution is distinct from being buried alive, in which the victim typically dies of asphyxia

Asphyxia or asphyxiation is a condition of deficient supply of oxygen to the body which arises from abnormal breathing. Asphyxia causes generalized hypoxia, which affects all the tissues and organs, some more rapidly than others. There are m ...

tion. By contrast, immurement has also occasionally been used as an early form of life imprisonment

Life imprisonment is any sentence (law), sentence of imprisonment under which the convicted individual is to remain incarcerated for the rest of their natural life (or until pardoned or commuted to a fixed term). Crimes that result in life impr ...

, in which cases the victims were regularly fed and given water. There have been a few cases in which people have survived for months or years after being walled up, as well as some people, such as anchorite

In Christianity, an anchorite or anchoret (female: anchoress); () is someone who, for religious reasons, withdraws from secular society to be able to lead an intensely prayer-oriented, Asceticism , ascetic, or Eucharist-focused life. Anchorit ...

s, who were voluntarily immured.

Notable examples of immurement as an established execution practice (with death from thirst or starvation as the intended aim) are attested. In the Roman Empire, Vestal Virgins faced live entombment as punishment if they were found guilty of breaking their chastity vows. Immurement has also been well established as a punishment of robbers in Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

, even into the early 20th century. Some ambiguous evidence exists of immurement as a practice of coffin-type confinement in Mongolia

Mongolia is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south and southeast. It covers an area of , with a population of 3.5 million, making it the world's List of countries and dependencies by po ...

. One famous, but likely mythical, immurement was that of Anarkali by Emperor Akbar because of her supposed relationship with Prince Saleem.

Isolated incidents of immurement, rather than elements of continuous traditions, are attested or alleged from numerous other parts of the world. Instances of immurement as an element of massacre within the context of war or revolution are also noted. Entombing living persons as a type of human sacrifice is also reported, for example, as part of grand burial ceremonies in some cultures.

As a motif in legends and folklore, many tales of immurement exist. In the folklore, immurement is prominent as a form of capital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence (law), sentence ordering that an offender b ...

, but its use as a type of human sacrifice

Human sacrifice is the act of killing one or more humans as part of a ritual, which is usually intended to please or appease deity, gods, a human ruler, public or jurisdictional demands for justice by capital punishment, an authoritative/prie ...

to make buildings sturdy has many tales attached to it as well. Skeletal remains have been, from time to time, found behind walls and in hidden rooms, and on several occasions have been asserted to be evidence of such sacrificial or punitive practices.

History

Europe

Olavinlinna

Olavinlinna (), also known as St. Olaf's Castle, is a 15th-century three-tower castle located in Savonlinna, Finland. It is built on an island in the Kyrönsalmi strait that connects the lakes Haukivesi and Pihlajavesi (Saimaa), Pihlajavesi. It is ...

as a punishment for treason. The subsequent growth of a rowan tree at the location of her execution, whose flowers were as white as her innocence and berries as red as her blood, inspired a ballad. Similar legends stem from Haapsalu

Haapsalu () is a seaside resort town located on the west coast of Estonia. It is the administrative centre of Lääne County, and on 1 January 2020 it had a population of 9,375.

History

The name ''Haapsalu'' derives from the Estonian words ' ...

, Kuressaare

Kuressaare () is a populated places in Estonia, town on the island of Saaremaa in Estonia. It is the administrative centre of Saaremaa Municipality and the seat of Saare County. Kuressaare is the westernmost town in Estonia. The recorded popul ...

, Põlva and Visby

Visby () is an urban areas in Sweden, urban area in Sweden and the seat of Gotland Municipality in Gotland County on the island of Gotland with 24,330 inhabitants . Visby is also the episcopal see for the Diocese of Visby. The Hanseatic League, ...

.

According to a Latvian legend, as many as three people might have been immured in tunnels under the Grobiņa Castle. A daughter of a knight living in the castle did not approve of her father's choice of a young nobleman as her future husband. Said knight also pillaged surrounding areas and took prisoners to live in the tunnels, among these a handsome young man whom the daughter took a liking to, helping him escape. Her fate was not so lucky as the knight and his future son-in-law punished her by immuring her in one of the tunnels. Another nobleman's daughter and a Swedish soldier are also said to be immured in one of the tunnels after she had fallen in love with the Swedish soldier and requested her father to allow her to marry him. According to another legend, a maiden and a servant were immured after a failed attempt at spying on Germans

Germans (, ) are the natives or inhabitants of Germany, or sometimes more broadly any people who are of German descent or native speakers of the German language. The Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany, constitution of Germany, imple ...

to gain intelligence on their plans for what is now Latvia.

In book 3 of his ''History of the Peloponnesian War

The ''History of the Peloponnesian War'' () is a historical account of the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC), which was fought between the Peloponnesian League (led by Sparta) and the Delian League (led by Classical Athens, Athens). The account, ...

'', Thucydides

Thucydides ( ; ; BC) was an Classical Athens, Athenian historian and general. His ''History of the Peloponnesian War'' recounts Peloponnesian War, the fifth-century BC war between Sparta and Athens until the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been d ...

goes into great detail on the revolution that broke out at Corfu

Corfu ( , ) or Kerkyra (, ) is a Greece, Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands; including its Greek islands, small satellite islands, it forms the margin of Greece's northwestern frontier. The island is part of the Corfu (regio ...

in 427 BC:

The Vestal Virgin

In ancient Rome, the Vestal Virgins or Vestals (, singular ) were priestesses of Vesta, virgin goddess of Rome's sacred hearth and its flame.

The Vestals were unlike any other public priesthood. They were chosen before puberty from several s ...

s in ancient Rome constituted a class of priestesses whose principal duty was to maintain the sacred fire dedicated to Vesta (goddess of the home and the family), and they lived under a strict vow of chastity and celibacy. If that vow of chastity was broken, the offending priestess was immured alive as follows:

The order of the Vestal Virgins existed for about 1,000 years, but only about 10 effected immurements are attested in extant sources.

Flavius Basiliscus, emperor of the Eastern Roman Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived the events that caused the fall of the Western Roman E ...

from AD 475–476, was deposed, and in winter he was sent to Cappadocia

Cappadocia (; , from ) is a historical region in Central Anatolia region, Turkey. It is largely in the provinces of Nevşehir, Kayseri, Aksaray, Kırşehir, Sivas and Niğde. Today, the touristic Cappadocia Region is located in Nevşehir ...

with his family. There they were imprisoned in either a dry cistern, or a tower, and perished. The historian Procopius

Procopius of Caesarea (; ''Prokópios ho Kaisareús''; ; – 565) was a prominent Late antiquity, late antique Byzantine Greeks, Greek scholar and historian from Caesarea Maritima. Accompanying the Roman general Belisarius in Justinian I, Empe ...

said they died exposed to cold and hunger, while other sources, such as Priscus

Priscus of Panium (; ; 410s/420s AD – after 472 AD) was an Eastern Roman diplomat and Greek historian and rhetorician (or sophist)...: "For information about Attila, his court and the organization of life generally in his realm we have the ...

, merely speaks of death by starvation.

The patriarch of Aquileia

This is a list of bishops and patriarchs of Aquileia in northeastern Italy. For the ecclesiastical history of the diocese, see Patriarchate of Aquileia.

From 553 until 698 the archbishops renounced Papal authority as part of the Schism of the T ...

, Poppo of Treffen

Poppo of Treffen (also Wolfgang) was the fifty-seventh patriarch of Aquileia from 1019 to 1045.

In 1020, Poppo commanded the smallest of three armies which Emperor Henry II (who had appointed him as patriarch) led through Italy. Poppo followed the ...

(r. 1019–1045), was a mighty secular potentate, and in 1044 he sacked Grado. The newly elected Doge of Venice

The Doge of Venice ( ) – in Italian, was the doge or highest role of authority within the Republic of Venice (697–1797). The word derives from the Latin , meaning 'leader', and Venetian Italian dialect for 'duke', highest official of the ...

, Domenico I Contarini, captured him and allegedly let him be buried up to his neck, and left guards to watch over him until he died.

In 1149, Duke Otto III of Olomouc of the Moravia

Moravia ( ; ) is a historical region in the eastern Czech Republic, roughly encompassing its territory within the Danube River's drainage basin. It is one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The medieval and early ...

n Přemyslid dynasty

The Přemyslid dynasty or House of Přemysl (, , ) was a Bohemian royal dynasty that reigned in the Duchy of Bohemia and later Kingdom of Bohemia and Margraviate of Moravia (9th century–1306), as well as in parts of Poland (including Silesia ...

immured the abbot Deocar and 20 monks in the refectory

A refectory (also frater, frater house, fratery) is a dining room, especially in monastery, monasteries, boarding schools and academic institutions. One of the places the term is most often used today is in graduate seminary, seminaries. The name ...

in the monastery of Rhadisch, where they starved to death. Ostensibly this was because one of the monks had fondled his wife Duranna when she had spent the night there. However, Otto III confiscated the monastery's wealth, and some said this was the motive for the immurement.

In the ruins of Thornton Abbey,

In the ruins of Thornton Abbey, Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire (), abbreviated ''Lincs'', is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East Midlands and Yorkshire and the Humber regions of England. It is bordered by the East Riding of Yorkshire across the Humber estuary to th ...

, an immured skeleton was found behind a wall along with a table, a book, and a candlestick. By some, he is believed to be the fourteenth abbot, immured for some crime he had committed.

The actual punishment meted out to men found guilty of paederasty might vary between different status groups. In 1409 and 1532 in

The actual punishment meted out to men found guilty of paederasty might vary between different status groups. In 1409 and 1532 in Augsburg

Augsburg ( , ; ; ) is a city in the Bavaria, Bavarian part of Swabia, Germany, around west of the Bavarian capital Munich. It is a College town, university town and the regional seat of the Swabia (administrative region), Swabia with a well ...

, two men were burned alive for their offences; a rather different fate was prescribed to four clerics found guilty of the same offence in another 1409 case. Instead of burning, they were locked into a wooden casket that was hung up in the Perlachturm

The 70-metre-tall Perlachturm is a belltower in front of the church of St. Peter am Perlach in the central district of Augsburg, Germany. It originated as a watchtower in the 10th century. The existing Renaissance structure was built in the 1610s ...

, and they starved to death.

After confessing in an Inquisition Court to an alleged conspiracy involving lepers, the Jewry, the King of Granada, and the Sultan of Babylon, Guillaume Agassa, head of the leper asylum at Lestang, was condemned in 1322 to be immured in shackles for life.

Hungarian countess

Count (feminine: countess) is a historical title of nobility in certain European countries, varying in relative status, generally of middling rank in the hierarchy of nobility. Pine, L. G. ''Titles: How the King Became His Majesty''. New York: ...

Elizabeth Báthory de Ecsed (''Báthory Erzsébet'' in Hungarian; 1560–1614) was immured in a set of rooms in 1610 for the death of several girls, with figures being as high as several hundred, though the actual number of victims is uncertain. The highest number of victims cited during the trial of Báthory's accomplices was 650; this number comes from a claim by a servant girl named Susannah that Jakab Szilvássy, Báthory's court official, had seen that figure in one of Báthory's private books. The book was never revealed and Szilvássy never mentioned it in his testimony. Being labeled the most prolific female serial killer in history has earned her the nickname of the "Blood Countess", and she is often compared with Vlad III the Impaler

Vlad III, commonly known as Vlad the Impaler ( ) or Vlad Dracula (; ; 1428/31 – 1476/77), was List of princes of Wallachia, Voivode of Wallachia three times between 1448 and his death in 1476/77. He is often considered one of the most imp ...

of Wallachia

Wallachia or Walachia (; ; : , : ) is a historical and geographical region of modern-day Romania. It is situated north of the Lower Danube and south of the Southern Carpathians. Wallachia was traditionally divided into two sections, Munteni ...

in folklore

Folklore is the body of expressive culture shared by a particular group of people, culture or subculture. This includes oral traditions such as Narrative, tales, myths, legends, proverbs, Poetry, poems, jokes, and other oral traditions. This also ...

. She was allowed to live in immurement until she died, four years after being sealed, ultimately dying of causes other than starvation; evidently her rooms were well supplied with food. According to other sources (written documents from the visit of priests, July 1614), she was able to move freely and unhindered within the castle, more akin to house arrest

House arrest (also called home confinement, or nowadays electronic monitoring) is a legal measure where a person is required to remain at their residence under supervision, typically as an alternative to imprisonment. The person is confined b ...

.

Asceticism

A particularly severe form ofasceticism

Asceticism is a lifestyle characterized by abstinence from worldly pleasures through self-discipline, self-imposed poverty, and simple living, often for the purpose of pursuing Spirituality, spiritual goals. Ascetics may withdraw from the world ...

within Christianity is that of anchorites, who typically allowed themselves to be immured, and subsisted on minimal food. For example, in the 4th century AD, one nun named Alexandra immured herself in a tomb for ten years with a tiny aperture enabling her to receive meager provisions. Saint Jerome

Jerome (; ; ; – 30 September 420), also known as Jerome of Stridon, was an early Christian priest, confessor, theologian, translator, and historian; he is commonly known as Saint Jerome.

He is best known for his translation of the Bible ...

() spoke of one follower who spent his entire life in a cistern, consuming no more than five figs a day. Gregory of Tours

Gregory of Tours (born ; 30 November – 17 November 594 AD) was a Gallo-Roman historian and Bishop of Tours during the Merovingian period and is known as the "father of French history". He was a prelate in the Merovingian kingdom, encom ...

, in his writings, related two stories of immurement, including that of a nun in Poitiers

Poitiers is a city on the river Clain in west-central France. It is a commune in France, commune, the capital of the Vienne (department), Vienne department and the historical center of Poitou, Poitou Province. In 2021, it had a population of 9 ...

. She was immured in a cell at her own request after experiencing a vision of Salvius of Albi, who was himself immured for a period prior to becoming bishop.

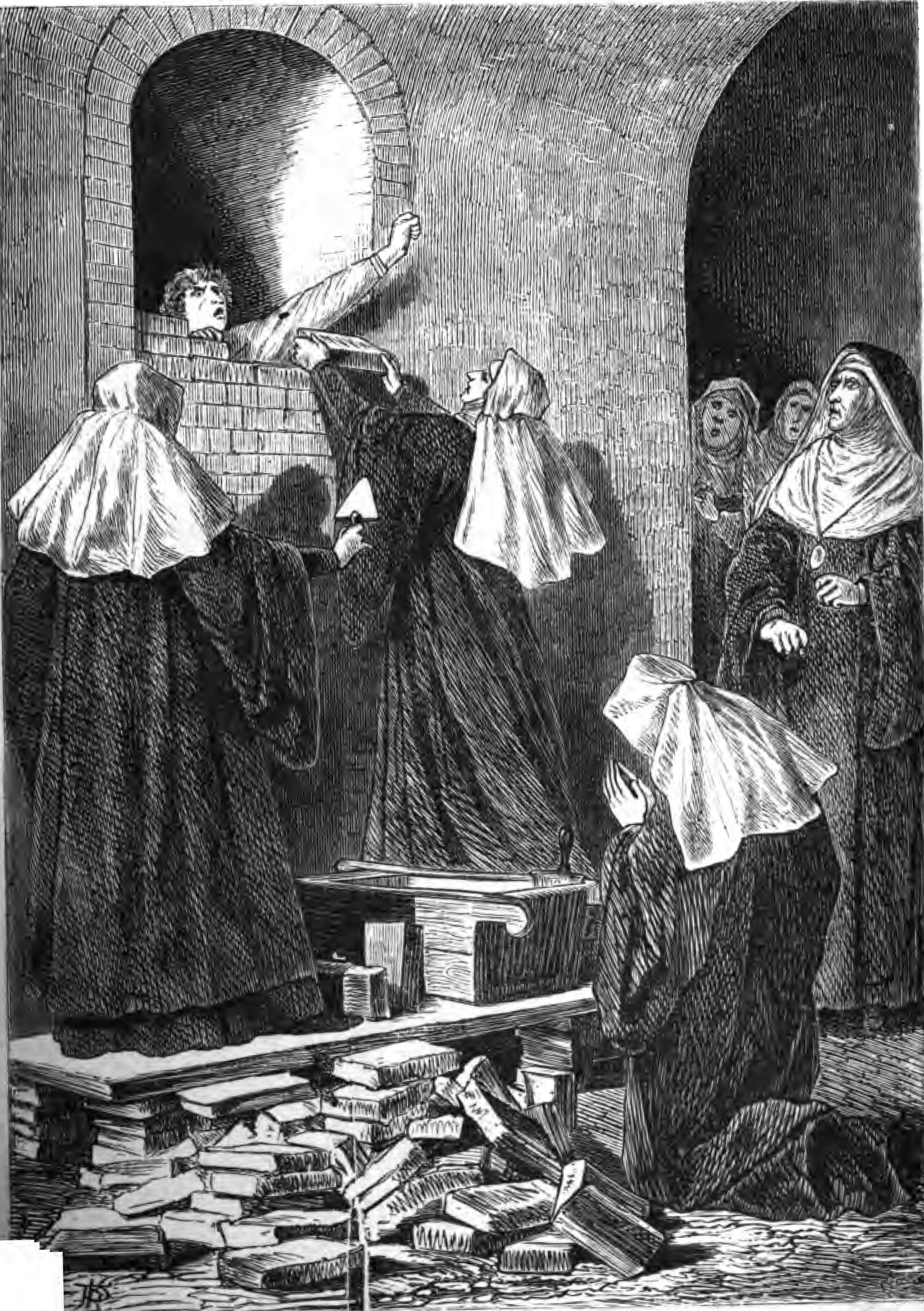

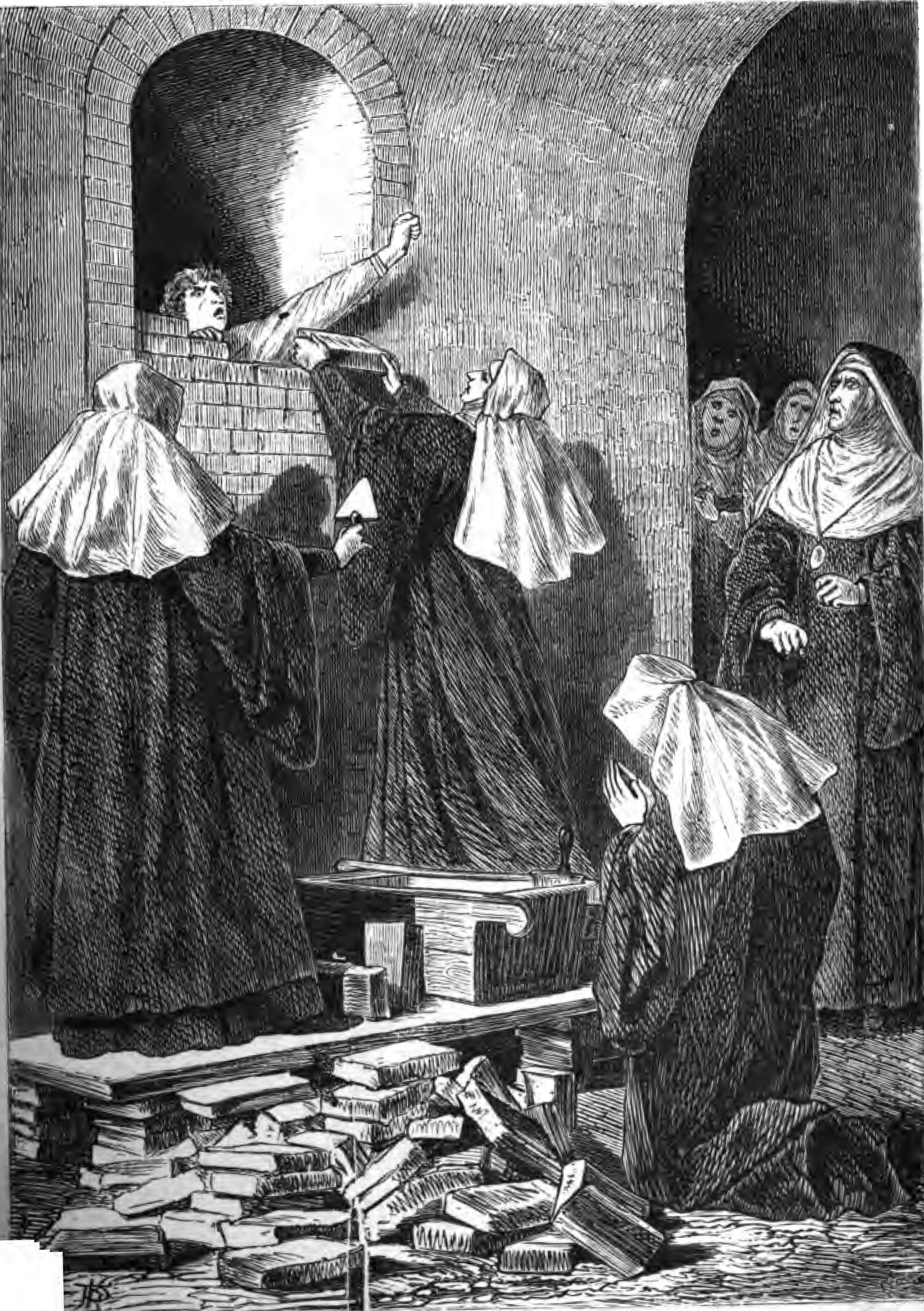

In Catholic monastic tradition, there existed a type of enforced, solitary confinement for nuns or monks who had broken their vows of chastity, or espoused heretical ideas. Henry Charles Lea offers an example:

Indeed, the punitive function of was that of perpetual seclusion. The guilty were condemned not to starve to death quickly, but to ''live'' in utter isolation from other human beings. As Lea describes in a footnote to this case:

Meanwhile, Sir

In Catholic monastic tradition, there existed a type of enforced, solitary confinement for nuns or monks who had broken their vows of chastity, or espoused heretical ideas. Henry Charles Lea offers an example:

Indeed, the punitive function of was that of perpetual seclusion. The guilty were condemned not to starve to death quickly, but to ''live'' in utter isolation from other human beings. As Lea describes in a footnote to this case:

Meanwhile, Sir Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European literature, European and Scottish literature, notably the novels ''Ivanhoe'' (18 ...

, himself an antiquarian, favors the alternative in a remark to his epic poem

In poetry, an epic is a lengthy narrative poem typically about the extraordinary deeds of extraordinary characters who, in dealings with gods or other superhuman forces, gave shape to the mortal universe for their descendants. With regard to ...

'' Marmion'' (1808):

The practice of immuring nuns or monks on breaches of chastity continued for several centuries into the early modern period. Francesca Medioli writes the following in her essay "Dimensions of the Cloister":

Asia

In the ancientSumer

Sumer () is the earliest known civilization, located in the historical region of southern Mesopotamia (now south-central Iraq), emerging during the Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age, early Bronze Ages between the sixth and fifth millennium BC. ...

ian city of Ur some graves (as early as 2500 BC.) clearly show the burial of attendants, along with that of the principal dead person. In one such grave, as Gerda Lerner wrote on page 60 of her book ''The Creation of Patriarchy'':

The Neo-Assyrian Empire

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was the fourth and penultimate stage of ancient Assyrian history. Beginning with the accession of Adad-nirari II in 911 BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire grew to dominate the ancient Near East and parts of South Caucasus, Nort ...

is notorious for its brutal repression techniques. Several of its rulers memorialized their victories in self-congratulatory detail. Here is a commemoration Ashurnasirpal II

Ashur-nasir-pal II (transliteration: ''Aššur-nāṣir-apli'', meaning " Ashur is guardian of the heir") was the third king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 883 to 859 BC. Ashurnasirpal II succeeded his father, Tukulti-Ninurta II. His son and s ...

(r. 883–859 BC) made that includes immurement:

Émile Durkheim

David Émile Durkheim (; or ; 15 April 1858 – 15 November 1917) was a French Sociology, sociologist. Durkheim formally established the academic discipline of sociology and is commonly cited as one of the principal architects of modern soci ...

in his work ''Suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death.

Risk factors for suicide include mental disorders, physical disorders, and substance abuse. Some suicides are impulsive acts driven by stress (such as from financial or ac ...

'' writes the following about certain followers of Amida Buddha:

By popular legend, Anarkali was immured between two walls in Lahore

Lahore ( ; ; ) is the capital and largest city of the Administrative units of Pakistan, Pakistani province of Punjab, Pakistan, Punjab. It is the List of cities in Pakistan by population, second-largest city in Pakistan, after Karachi, and ...

by order of Mughal Emperor Akbar

Akbar (Jalal-ud-din Muhammad Akbar, – ), popularly known as Akbar the Great, was the third Mughal emperor, who reigned from 1556 to 1605. Akbar succeeded his father, Humayun, under a regent, Bairam Khan, who helped the young emperor expa ...

for having a relationship with crown prince Salim (later Emperor Jehangir

Nur-ud-din Muhammad Salim (31 August 1569 – 28 October 1627), known by his imperial name Jahangir (; ), was List of emperors of the Mughal Empire, Emperor of Hindustan from 1605 until his death in 1627, and the fourth Mughal emperors, Mughal ...

) in the 16th century. A bazaar developed around the site, and was named Anarkali Bazaar

Anarkali Bazaar (Punjabi language, Punjabi, ) is a major bazaar in Lahore, Punjab, Pakistan, Punjab, Pakistan. Anarkali also serves as a neighbourhood and union council of Data Gunj Buksh Town, Data Gunj Buksh Tehsil of Lahore. It is situated in ...

in her honour.

A tradition existed in Persia of walling up criminals and leaving them to die of hunger or thirst. The traveller M. E. Hume-Griffith stayed in Persia from 1900 to 1903, and she wrote the following:

Travelling back and forth to Persia from 1630 to 1668 as a gem merchant, Jean-Baptiste Tavernier observed much the same custom that Hume-Griffith noted some 250 years later. Tavernier notes that immuring was principally a punishment for thieves, and that immurement left the convict's head out in the open. According to him, many of these individuals would implore passers-by to cut off their heads, an amelioration of the punishment forbidden by law. John Fryer John Fryer may refer to:

*John Fryer (physician, died 1563), English physician, humanist and early reformer

*John Fryer (physician, died 1672), English physician

*John Fryer (travel writer) (1650–1733), British travel-writer and doctor

*Sir John ...

, travelling Persia in the 1670s, writes:

In the late 1650s, various sons of the Mughal emperor

The emperors of the Mughal Empire, who were all members of the Timurid dynasty (House of Babur), ruled the empire from its inception on 21 April 1526 to its dissolution on 21 September 1857. They were supreme monarchs of the Mughal Empire in ...

Shah Jahan

Shah Jahan I, (Shahab-ud-Din Muhammad Khurram; 5 January 1592 – 22 January 1666), also called Shah Jahan the Magnificent, was the Emperor of Hindustan from 1628 until his deposition in 1658. As the fifth Mughal emperor, his reign marked the ...

became embroiled in wars of succession, in which Aurangzeb

Alamgir I (Muhi al-Din Muhammad; 3 November 1618 – 3 March 1707), commonly known by the title Aurangzeb, also called Aurangzeb the Conqueror, was the sixth Mughal emperors, Mughal emperor, reigning from 1658 until his death in 1707, becomi ...

was victorious. One of his half-brothers, Shah Shujah proved particularly troublesome, but in 1661 Aurangzeb defeated him, and Shah Shuja and his family sought the protection of the King of Arakan

Arakan ( or ; , ), formerly anglicised as Aracan, is the historical geographical name for the northeastern coastal region of the Bay of Bengal, covering present-day Bangladesh and Myanmar. The region was called "Arakan" for centuries. It is ...

. According to Francois Bernier, the King reneged on his promise of asylum, and Shuja's sons were decapitated, while his daughters were immured and died of starvation.

During Mughal rule in early 18th century India, the two youngest sons of Guru Gobind Singh

Guru Gobind Singh (; born Gobind Das; 22 December 1666 – 7 October 1708) was the tenth and last human Sikh gurus, Sikh Guru. He was a warrior, poet, and philosopher. In 1675, at the age of nine he was formally installed as the leader of the ...

were sentenced to death by being bricked in alive for their refusal to convert to Islam and abandon the Sikh

Sikhs (singular Sikh: or ; , ) are an ethnoreligious group who adhere to Sikhism, a religion that originated in the late 15th century in the Punjab region of the Indian subcontinent, based on the revelation of Guru Nanak. The term ''Si ...

faith. On 26 December 1705, Fateh Singh was killed in this manner at Sirhind

Sirhind is a Twin cities, twin city of Fatehgarh Sahib in Punjab, India, Punjab, India. It is hosts the municipal council of Fatehgarh Sahib district.

Demographics

In the 2011 census of India, 2011 census Sirhind-Fatehgarh had a population of ...

along with his elder brother, Zorawar Singh. Gurdwara Fatehgarh Sahib which is situated 5 km north of Sirhind marks the site of the execution of the two younger sons of Guru Gobind Singh at the behest of Wazir Khan of Kunjpura, the Governor of Sirhind. The three shrines within this Gurdwara complex mark the exact spot where these events were witnessed in 1705.

Jezzar Pasha, the Ottoman governor of provinces in modern Lebanon, and Palestine from 1775 to 1804, was infamous for his cruelties. When building the new walls of Beirut

Beirut ( ; ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, just under half of Lebanon's population, which makes it the List of largest cities in the Levant region by populatio ...

, he was charged with, among other things, the following:

Staying as a diplomat in Persia from 1860 to 1863, E. B. Eastwick met at one time, the '' Sardar i Kull'', or military high commander, Aziz Khan. Eastwick notes that he "did not strike me as one who would greatly err on the side of leniency". Eastwick was told that just recently, Aziz Khan had ordered 14 robbers walled up alive, two of them head-downwards. Staying for the year 1887–1888 primarily in Shiraz

Shiraz (; ) is the List of largest cities of Iran, fifth-most-populous city of Iran and the capital of Fars province, which has been historically known as Pars (Sasanian province), Pars () and Persis. As of the 2016 national census, the popu ...

, Edward Granville Browne

Edward Granville Browne FBA (7 February 1862 – 5 January 1926) was a British Iranologist. He published numerous articles and books, mainly in the areas of history and literature.

Life

Browne was born in Stouts Hill, Uley, Gloucestershire, ...

noted the gloomy reminders of a particularly bloodthirsty governor there, Firza Ahmed, who in his four years of office (ending circa 1880) had caused, for example, more than 700 hands cut off for various offences. Browne continues:

Immurement was practiced in Mongolia as recently as the early 20th century. It is not clear that all thus immured were meant to die of starvation. In a newspaper report from 1914, it is written:

North Africa

In 1906, Hadj Mohammed Mesfewi, a cobbler fromMarrakesh

Marrakesh or Marrakech (; , ) is the fourth-largest city in Morocco. It is one of the four imperial cities of Morocco and is the capital of the Marrakesh–Safi Regions of Morocco, region. The city lies west of the foothills of the Atlas Mounta ...

, was found guilty of murdering 36 women; the bodies were found buried underneath his shop and nearby. Due to the nature of his crimes, he was walled up alive. For two days his screams were heard incessantly before silence by the third day.

Sacrificial variations

Construction

A number of cultures have tales and ballads containing as a motif the sacrifice of a human being to ensure the strength of a building. For example, there was a culture of human sacrifice in the construction of large buildings in East and Southeast Asia. Such practices ranged from da sheng zhuang (打生樁) in China to hitobashira in Japan and myosade (မြို့စတေး) in Burma. The folklore of manySoutheastern Europe

Southeast Europe or Southeastern Europe is a geographical sub-region of Europe, consisting primarily of the region of the Balkans, as well as adjacent regions and Archipelago, archipelagos. There are overlapping and conflicting definitions of t ...

an peoples refers to immurement as the mode of death for the victim sacrificed during the completion of a construction project, such as a bridge or fortress (mostly real buildings). The Castle of Shkodra is the subject of such stories in both the Albanian oral tradition and in the Slavic one. The Albanian version is The Legend of Rozafa, in which three brothers uselessly toil at building walls which always disappear at night: when told that they must bury one of their wives in the wall, they pledge to choose the one that brings them luncheon the next day, and not to warn their respective spouses. However, two brothers secretly inform their wives (the topos of two fellows betraying one being common in Balkan poetry, cf. Miorița or the Song of Çelo Mezani), leaving Rozafa, wife of the honest brother, to die. She accepts her fate, but asks that they leave exposed a foot to rock the infant son's cradle, a breast to feed him, and a hand to stroke his hair.

One of the most famous versions of the same legend is the Serbian epic poem called '' The Building of Skadar'' (Зидање Скадра, ''Zidanje Skadra'') published by Vuk Karadžić

Vuk Stefanović Karadžić ( sr-Cyrl, Вук Стефановић Караџић, ; 6 November 1787 (26 October OS)7 February 1864) was a Serbian philologist, anthropologist and linguist. He was one of the most important reformers of the moder ...

, after he recorded a folk song sung by a Herzegovinian storyteller named Old Rashko. The version of the song in the Serbian language

Serbian (, ) is the standard language, standardized Variety (linguistics)#Standard varieties, variety of the Serbo-Croatian language mainly used by Serbs. It is the official and national language of Serbia, one of the three official languages of ...

is the oldest collected version of the legend, and the first one which earned literary fame. The three brothers in the legend were represented by members of the noble Mrnjavčević family

The House of Mrnjavčević ( sr-Cyrl, Мрњавчевић, Mrnjavčevići / Мрњавчевићи, ) was a medieval Serbian noble house during the Serbian Empire, its fall, and the subsequent years when it held a region of present-day Mac ...

, Vukašin

Vukašin () is an old Slavic name of Serbian origin. It is composed from two words: Vuk (wolf) and sin ( son), so it means sin vuka (son of wolf). In some places in Croatia and Bosnia it can be found as a surname.

The name Vukašin can be foun ...

, Uglješa and Gojko. In 1824, Karadžić sent a copy of his folksong collection to Jacob Grimm

Jacob Ludwig Karl Grimm (4 January 1785 – 20 September 1863), also known as Ludwig Karl, was a German author, linguist, philologist, jurist, and folklorist. He formulated Grimm's law of linguistics, and was the co-author of the ''Deutsch ...

, who was particularly enthralled by the poem. Grimm translated it into German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

, and described it as "one of the most touching poems of all nations and all times". Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Johann Wolfgang (von) Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German polymath who is widely regarded as the most influential writer in the German language. His work has had a wide-ranging influence on Western literature, literary, Polit ...

published the German translation, but did not share Grimm's opinion because he found the poem's spirit "superstitiously barbaric". Alan Dundes, a famous folklorist

Folklore studies (also known as folkloristics, tradition studies or folk life studies in the UK) is the academic discipline devoted to the study of folklore. This term, along with its synonyms, gained currency in the 1950s to distinguish the ac ...

, noted that Grimm's opinion prevailed and that the ballad continued to be admired by generations of folksingers and ballad scholars.

A very similar Romanian legend, that of Meşterul Manole, tells of the building of the Curtea de Argeș Monastery. Ten expert masons, among them Master Manole himself, are ordered by Neagu Voda to build a beautiful monastery, but incur the same fate, and also decide to immure the wife who will bring them luncheon. Manole, working on the roof, sees her approach, and pleads in vain with God to unleash the elements in order to stop her. When she arrives, he proceeds to wall her in, pretending to be doing so in jest, while she cries out increasingly in pain and distress. When the building is finished, Neagu Voda takes away the masons' ladders, fearing they will build a more beautiful building. They try to escape, but all fall to their deaths. Only from Manole's fall a stream is created.

Many other Bulgarian and Romanian folk poems and songs describe a bride offered for such purposes, and her subsequent pleas to the builders to leave her hands and breasts free, that she might still nurse her child. Later versions of the songs revise the bride's death; her fate to languish entombed within the construction is transmuted to her nonphysical shadow, and its loss yet leads to her pining away and eventual death.

Other variations include the Hungarian folk ballad "Kőmíves Kelemen" (Kelemen the Stonemason). This is the story of twelve unfortunate stonemasons tasked with building the fort of Déva. To remedy its recurring collapses, it is agreed that one of the builders must sacrifice his bride, and the bride to be sacrificed will be she who first comes to visit. In some versions of the ballad the victim is shown some mercy; rather than being trapped alive she is burned and only her ashes are immured.

A Greek story, " The Bridge of Arta" (), describes numerous failed attempts to build a bridge in that city. Again, a cycle wherein a team of skilled builders toils all day only to return the next morning to find their work demolished is eventually ended when the master mason's wife is immured. Legend has it that a maiden was immured in the walls of Madliena

Madliena (), formerly spelt Madalena, is an area in Swieqi, in Northern Region, Malta, Northern Region, Malta, formerly part of the adjacent town of Għargħur.

Etymology

It takes its name from a chapel dedicated to St. Mary Magdalene, which w ...

church as a sacrifice or offering after continuous failed construction attempts. The pastor achieved this by inviting all of the most beautiful maidens to a feast; the most beautiful one, Madaļa, falls into a deep sleep after the pastor offers wine from "certain goblet".

Ceremonial

Within Inca culture, it is reported that one element in the great Sun festival was the sacrifice of young maidens (between ten and twelve years old), who after their ceremonial duties were done were lowered down in a waterlesscistern

A cistern (; , ; ) is a waterproof receptacle for holding liquids, usually water. Cisterns are often built to catch and store rainwater. To prevent leakage, the interior of the cistern is often lined with hydraulic plaster.

Cisterns are disti ...

and immured alive. The children of Llullaillaco represent another form of Incan child sacrifice.

Acknowledging the traditions of human sacrifice in the context of the building of structures within German and Slavic folklore, Jacob Grimm

Jacob Ludwig Karl Grimm (4 January 1785 – 20 September 1863), also known as Ludwig Karl, was a German author, linguist, philologist, jurist, and folklorist. He formulated Grimm's law of linguistics, and was the co-author of the ''Deutsch ...

offers some examples of the sacrifice of animals as well. According to him, within Danish traditions, a lamb was immured under an erected altar in order to preserve it, while a churchyard was to be ensured protection by immuring a living horse as part of the ceremony. In the ceremonies of erection of other types of constructions, Grimm notices that other animals were sacrificed as well, such as pigs, hens and dogs.

Harold Edward Bindloss, in his 1898 non-fiction ''In the Niger country'', writes of the funeral of a great chief:

Similarly, the 14th century traveller Ibn Batuta

Ibn Battuta (; 24 February 13041368/1369), was a Maghrebis, Maghrebi traveller, explorer and scholar. Over a period of 30 years from 1325 to 1354, he visited much of Africa, the Middle East, Asia and the Iberian Peninsula. Near the end of his ...

observed the burial of a great khan:

In literature and the arts

;Opera At the end of Verdi's opera ''Aida

''Aida'' (or ''Aïda'', ) is a tragic opera in four acts by Giuseppe Verdi to an Italian libretto by Antonio Ghislanzoni. Set in the Old Kingdom of Egypt, it was commissioned by Cairo's Khedivial Opera House and had its première there on 24 De ...

'' the Egyptian General Radames is found guilty of treason and is immured in a cave as punishment. Once the cave is enclosed, he discovers that his lover Aida has hidden in the cave to be with him, and they die there together.

;Literature

In Honoré de Balzac

Honoré de Balzac ( , more commonly ; ; born Honoré Balzac; 20 May 1799 – 18 August 1850) was a French novelist and playwright. The novel sequence ''La Comédie humaine'', which presents a panorama of post-Napoleonic French life, is ...

's 1831 story " La Grande Bretèche," Madame de Merret is accused by her husband of hiding a lover in her bedroom closet; she swears on a crucifix that no one is in there and threatens to leave him if he casts doubt on her character by checking. In response, her husband has the closet door sealed and plastered over, then spends the next twenty days living in his wife's room to ensure her lover cannot escape.

Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe (; January 19, 1809 – October 7, 1849) was an American writer, poet, editor, and literary critic who is best known for his poetry and short stories, particularly his tales involving mystery and the macabre. He is widely re ...

's short story "The Cask of Amontillado

"The Cask of Amontillado" is a short story by the American writer Edgar Allan Poe, first published in the November 1846 issue of ''Godey's Lady's Book''. The story, set in an unnamed Italy, Italian city at carnival time, is about a man taking fa ...

" involves the narrator murdering a rival by immuring him in a crypt. This story has been adapted for screen over the years

Ariana Franklin's ''Mistress of the Art of Death'' (2007) includes the execution of a nun by walling her into her cell, to circumvent the protection usually afforded by her vows.

In the 1978 novel ''The Three-Arched Bridge

''The Three Arched Bridge'' () is a 1978 novel by Albanian author Ismail Kadare. The story concerns a very old Albanian legend written in verses, the " Legjenda e Rozafes". The book differs from the original legend, as the legend calls for a ...

'' by Albanian writer Ismail Kadare

Ismail Kadare (; 28 January 1936 – 1 July 2024) was an Albanian novelist, poet, essayist, screenwriter and playwright. He was a leading international literary figure and intellectual, focusing on poetry until the publication of his first novel ...

, the immurement of a villager plays an important role; whether or not he volunteered or was punished remains unclear. The book also contains discussion on the background and motives of the characters in the Legend of Rozafa.

;Stage, film, and television

In the 1944 film '' The Canterville Ghost,'' Sir Simon (Charles Laughton

Charles Laughton (; 1 July 1899 – 15 December 1962) was a British and American actor. He was trained in London at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art and first appeared professionally on the stage in 1926. In 1927, he was cast in a play wi ...

) is immured by his father while he is hiding to avoid fighting a duel.

At the end of the 1955 movie '' Land of the Pharaohs'', scheming Princess Nellifer (Joan Collins

Dame Joan Henrietta Collins (born 23 May 1933) is an English actress, author and columnist. She is the recipient of several accolades, including a Golden Globe Awards, a People's Choice Award, two Soap Opera Digest Awards and a Primetime Emm ...

) is shocked to learn that she has been immured in the tomb of her husband Pharaoh Khufu ( Jack Hawkins).

In " The Ikon of Elijah", a 1960 episode of ''Alfred Hitchcock Presents

''Alfred Hitchcock Presents'' is an American television anthology series created, hosted and produced by Alfred Hitchcock, airing on CBS and NBC, alternately, between 1955 and 1965. It features dramas, thrillers, and mysteries. Between 1962 ...

'', the main character is immured in a monastic cell as penance for having killed a monk.

Poe's ''The Cask of Amontillado'' has been adapted for film and television, including a segment in Roger Corman

Roger William Corman (April 5, 1926 – May 9, 2024) was an American film director, producer, and actor. Known under various monikers such as "The Pope of Pop Cinema", "The Spiritual Godfather of the New Hollywood", and "The King of Cult", he w ...

's anthology '' Tales of Terror'' (1962) and an episode of the 2023 Netflix

Netflix is an American subscription video on-demand over-the-top streaming service. The service primarily distributes original and acquired films and television shows from various genres, and it is available internationally in multiple lang ...

series '' The Fall of the House of Usher.''

The walling-in of wayward monastics, individuals and entire cloisters alike, is common in the genre of nunsploitation; several such films draw on the historical case of the Nun of Monza in particular. Though in reality she was released from immurement after serving some 10 or 15 years, some movies dramatize her fate as one of permanent confinement.

In the 1976 Danish comedy film '' The Olsen Gang Sees Red'' the protagonist is momentarily immured in a castle dungeon next to actual immurements.

In a 1984 episode of ''Thomas the Tank Engine

Thomas the Tank Engine is a fictional, anthropomorphised tank locomotive who originated from the British children's books ''The Railway Series'', created and written by Wilbert Awdry with his son Christopher Awdry, Christopher, first publish ...

'' "The Sad Story of Henry" the engine Henry was immured as punishment for disobeying the orders of The Fat Controller

The Fat Controller is a fictional character originating from ''The Railway Series'' books written by Wilbert Awdry, Reverend W. Awdry and his son, Christopher Awdry.

In the first two books in the series (''List of books in The Railway Series# ...

.

In a 2003 episode of ''The Simpsons

''The Simpsons'' is an American animated sitcom created by Matt Groening and developed by Groening, James L. Brooks and Sam Simon for the Fox Broadcasting Company. It is a Satire (film and television), satirical depiction of American life ...

'', " C.E.D'oh", Mr. Burns unsuccessfully tries to immure Homer Simpson as revenge for taking over the Springfield Nuclear Power Plant.

See also

* "The Cask of Amontillado

"The Cask of Amontillado" is a short story by the American writer Edgar Allan Poe, first published in the November 1846 issue of ''Godey's Lady's Book''. The story, set in an unnamed Italy, Italian city at carnival time, is about a man taking fa ...

"

* Dried cat

* Oubliette

A dungeon is a room or cell in which prisoners are held, especially underground. Dungeons are generally associated with medieval castles, though their association with torture probably derives more from the Renaissance period. An oubliette (fr ...

* Life imprisonment

Life imprisonment is any sentence (law), sentence of imprisonment under which the convicted individual is to remain incarcerated for the rest of their natural life (or until pardoned or commuted to a fixed term). Crimes that result in life impr ...

* Human sacrifice

Human sacrifice is the act of killing one or more humans as part of a ritual, which is usually intended to please or appease deity, gods, a human ruler, public or jurisdictional demands for justice by capital punishment, an authoritative/prie ...

* Anarkali

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

{{Capital punishment Execution methods Causes of death Starvation Dehydration