History of telecommunications on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of telecommunication began with the use of

The history of telecommunication began with the use of

Experiments on communication with electricity, initially unsuccessful, started in about 1726. Scientists including

Experiments on communication with electricity, initially unsuccessful, started in about 1726. Scientists including

The electric telephone was invented in the 1870s, based on earlier work with harmonic (multi-signal) telegraphs. The first commercial telephone services were set up in 1878 and 1879 on both sides of the Atlantic in the cities of

The electric telephone was invented in the 1870s, based on earlier work with harmonic (multi-signal) telegraphs. The first commercial telephone services were set up in 1878 and 1879 on both sides of the Atlantic in the cities of

''The Master Switch: The Rise and Fall of Information Empires''

(2010) * Lundy, Bert. ''Telegraph, Telephone and Wireless: How Telecom Changed the World'' (2008)

, Electrical Engineering and Computer Science Department (EECS) Department, University of California, Berkeley.

International Telecommunication Union

From the Thurn & Taxis to the Phone Book of the World - 730 years of Telecom History

Telecommunications History Group Virtual Museum

Telecommunications History Germany

Telecommunications History France

{{Telecommunications History of telecommunications, History of science by discipline, Telecommunications

The history of telecommunication began with the use of

The history of telecommunication began with the use of smoke signal

The smoke signal is one of the oldest forms of long-distance communication. It is a form of visual communication used over a long distance. In general smoke signals are used to transmit news, signal danger, or to gather people to a common area. ...

s and drum

The drum is a member of the percussion group of musical instruments. In the Hornbostel–Sachs classification system, it is a membranophone. Drums consist of at least one membrane, called a drumhead or drum skin, that is stretched over a ...

s in Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surfac ...

, Asia

Asia ( , ) is the largest continent in the world by both land area and population. It covers an area of more than 44 million square kilometres, about 30% of Earth's total land area and 8% of Earth's total surface area. The continent, which ...

, and the Americas

The Americas, sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North America and South America.''Webster's New World College Dictionary'', 2010 by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Cleveland, Ohio. When viewed as a sing ...

. In the 1790s, the first fixed semaphore systems emerged in Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

. However, it was not until the 1830s that electrical telecommunication

Telecommunication, often used in its plural form or abbreviated as telecom, is the transmission of information over a distance using electronic means, typically through cables, radio waves, or other communication technologies. These means of ...

systems started to appear. This article details the history of telecommunication and the individuals who helped make telecommunication systems what they are today. The history of telecommunication is an important part of the larger history of communication

The history of communication technologies (media and appropriate inscription tools) have evolved in tandem with shifts in political and economic systems, and by extension, systems of power. Communication can range from very subtle processes of exc ...

.

Ancient systems and optical telegraphy

Early telecommunications includedsmoke signal

The smoke signal is one of the oldest forms of long-distance communication. It is a form of visual communication used over a long distance. In general smoke signals are used to transmit news, signal danger, or to gather people to a common area. ...

s and drum

The drum is a member of the percussion group of musical instruments. In the Hornbostel–Sachs classification system, it is a membranophone. Drums consist of at least one membrane, called a drumhead or drum skin, that is stretched over a ...

s. Talking drum

The talking drum is an hourglass-shaped drum from West Africa, which can be used as a form of speech surrogacy by regulating its pitch and rhythm to mimic the tone and prosody of human speech. It has two drumheads connected by leather t ...

s were used by natives in Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surfac ...

, and smoke signals in North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres. North America is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South Ameri ...

and China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

. These systems were often used to do more than announce the presence of a military camp.

In Rabbinical Judaism

Rabbinic Judaism (), also called Rabbinism, Rabbinicism, Rabbanite Judaism, or Talmudic Judaism, is rooted in the many forms of Judaism that coexisted and together formed Second Temple Judaism in the land of Israel, giving birth to classical rabb ...

a signal was given by means of kerchiefs or flags at intervals along the way back to the high priest to indicate the goat "for Azazel" had been pushed from the cliff.

Homing pigeon

The homing pigeon is a variety of domestic pigeon (''Columba livia domestica''), selectively bred for its ability to find its way home over extremely long distances. Because of this skill, homing pigeons were used to carry messages, a practice ...

s have occasionally been used throughout history by different cultures. Pigeon post

Pigeon post is the use of homing pigeons to carry messages. Pigeons are effective as messengers due to their natural homing abilities. The pigeons are transported to a destination in cages, where they are attached with messages, then the pigeo ...

had Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

n roots, and was later used by the Romans to aid their military.

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

hydraulic semaphore systems were used as early as the 4th century BC. The hydraulic semaphores, which worked with water filled vessels and visual signals, functioned as optical telegraphs. However, they could only utilize a very limited range of pre-determined messages, and as with all such optical telegraphs could only be deployed during good visibility conditions.

During the Middle Ages, chains of beacon

A beacon is an intentionally conspicuous device designed to attract attention to a specific location. A common example is the lighthouse, which draws attention to a fixed point that can be used to navigate around obstacles or into port. More mode ...

s were commonly used on hilltops as a means of relaying a signal. Beacon chains suffered the drawback that they could only pass a single bit of information, so the meaning of the message such as "the enemy has been sighted" had to be agreed upon in advance. One notable instance of their use was during the Spanish Armada

The Spanish Armada (often known as Invincible Armada, or the Enterprise of England, ) was a Spanish fleet that sailed from Lisbon in late May 1588, commanded by Alonso de Guzmán, Duke of Medina Sidonia, an aristocrat without previous naval ...

, when a beacon chain relayed a signal from Plymouth

Plymouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Devon, South West England. It is located on Devon's south coast between the rivers River Plym, Plym and River Tamar, Tamar, about southwest of Exeter and ...

to London that signaled the arrival of the Spanish warships.

In 1774, the Swiss physicist Georges Lesage built an electrostatic telegraph consisting of a set of 24 conductive wires a few meters long connected to 24 elder balls suspended from a silk thread (each wire corresponds to a letter). The electrification of a wire by means of an electrostatic generator causes the corresponding elder ball to deflect and designate a letter to the operator located at the end of the line. The sequence of selected letters leads to the writing and transmission of a message.

French engineer Claude Chappe

Claude Chappe (; 25 December 1763 – 23 January 1805) was a French inventor who in 1792 demonstrated a practical semaphore line, semaphore system that eventually spanned all of France. His system consisted of a series of towers, each within l ...

began working on visual telegraphy in 1790, using pairs of "clocks" whose hands pointed at different symbols. These did not prove quite viable at long distances, and Chappe revised his model to use two sets of jointed wooden beams. Operators moved the beams using cranks and wires. He built his first telegraph line

Electrical telegraphy is point-to-point distance communicating via sending electric signals over wire, a system primarily used from the 1840s until the late 20th century. It was the first electrical telecommunications system and the most wide ...

between Lille

Lille (, ; ; ; ; ) is a city in the northern part of France, within French Flanders. Positioned along the Deûle river, near France's border with Belgium, it is the capital of the Hauts-de-France Regions of France, region, the Prefectures in F ...

and Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

, followed by a line from Strasbourg

Strasbourg ( , ; ; ) is the Prefectures in France, prefecture and largest city of the Grand Est Regions of France, region of Geography of France, eastern France, in the historic region of Alsace. It is the prefecture of the Bas-Rhin Departmen ...

to Paris. In 1794, a Swedish engineer, Abraham Edelcrantz built a quite different system from Stockholm

Stockholm (; ) is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in Sweden by population, most populous city of Sweden, as well as the List of urban areas in the Nordic countries, largest urban area in the Nordic countries. Approximately ...

to Drottningholm. As opposed to Chappe's system which involved pulleys rotating beams of wood, Edelcrantz's system relied only upon shutters and was therefore faster.

However, semaphore as a communication system suffered from the need for skilled operators and expensive towers often at intervals of only ten to thirty kilometers (six to nineteen miles). As a result, the last commercial line was abandoned in 1880.

Electrical telegraph

Experiments on communication with electricity, initially unsuccessful, started in about 1726. Scientists including

Experiments on communication with electricity, initially unsuccessful, started in about 1726. Scientists including Laplace

Pierre-Simon, Marquis de Laplace (; ; 23 March 1749 – 5 March 1827) was a French polymath, a scholar whose work has been instrumental in the fields of physics, astronomy, mathematics, engineering, statistics, and philosophy. He summariz ...

, Ampère, and Gauss

Johann Carl Friedrich Gauss (; ; ; 30 April 177723 February 1855) was a German mathematician, astronomer, Geodesy, geodesist, and physicist, who contributed to many fields in mathematics and science. He was director of the Göttingen Observat ...

were involved.

An early experiment in electrical telegraph

Electrical telegraphy is point-to-point distance communicating via sending electric signals over wire, a system primarily used from the 1840s until the late 20th century. It was the first electrical telecommunications system and the most wid ...

y was an 'electrochemical' telegraph created by the German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

physician, anatomist and inventor Samuel Thomas von Sömmerring

Samuel Thomas von Sömmerring (28 January 1755 – 2 March 1830) was a German physician, anatomist, anthropologist, paleontologist and inventor. Sömmerring discovered the macula in the retina of the human eye. His investigations on the bra ...

in 1809, based on an earlier, less robust design of 1804 by Spanish polymath

A polymath or polyhistor is an individual whose knowledge spans many different subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific problems. Polymaths often prefer a specific context in which to explain their knowledge, ...

and scientist Francisco Salva Campillo. Both their designs employed multiple wires (up to 35) in order to visually represent almost all Latin letters and numerals. Thus, messages could be conveyed electrically up to a few kilometers (in von Sömmerring's design), with each of the telegraph receiver's wires immersed in a separate glass tube of acid. An electric current was sequentially applied by the sender through the various wires representing each digit of a message; at the recipient's end the currents electrolysed the acid in the tubes in sequence, releasing streams of hydrogen bubbles next to each associated letter or numeral. The telegraph receiver's operator would visually observe the bubbles and could then record the transmitted message, albeit at a very low baud

In telecommunications and electronics, baud (; symbol: Bd) is a common unit of measurement of symbol rate, which is one of the components that determine the speed of communication over a data channel.

It is the unit for symbol rate or modulat ...

rate.

The principal disadvantage to the system was its prohibitive cost, due to having to manufacture and string-up the multiple wire circuits it employed, as opposed to the single wire (with ground return) used by later telegraphs.

The first working telegraph was built by Francis Ronalds

Sir Francis Ronalds Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS (21 February 17888 August 1873) was an English scientist and inventor, and arguably the first History of electrical engineering, electrical engineer. He was knighted for creating the first wo ...

in 1816 and used static electricity.

Charles Wheatstone

Sir Charles Wheatstone (; 6 February 1802 – 19 October 1875) was an English physicist and inventor best known for his contributions to the development of the Wheatstone bridge, originally invented by Samuel Hunter Christie, which is used to m ...

and William Fothergill Cooke

Sir William Fothergill Cooke (4 May 1806 – 25 June 1879) was an English inventor. He was, with Charles Wheatstone, the co-inventor of the Cooke-Wheatstone electrical telegraph, which was patented in May 1837. Together with John Ricardo he fo ...

patented a five-needle, six-wire system, which entered commercial use in 1838. It used the deflection of needles to represent messages and started operating over twenty-one kilometres (thirteen miles) of the Great Western Railway

The Great Western Railway (GWR) was a History of rail transport in Great Britain, British railway company that linked London with the southwest, west and West Midlands (region), West Midlands of England and most of Wales. It was founded in 1833, ...

on 9 April 1839. Both Wheatstone and Cooke viewed their device as "an improvement to the xistingelectromagnetic telegraph" not as a new device.

On the other side of the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the ...

, Samuel Morse

Samuel Finley Breese Morse (April 27, 1791 – April 2, 1872) was an American inventor and painter. After establishing his reputation as a portrait painter, Morse, in his middle age, contributed to the invention of a Electrical telegraph#Morse ...

developed a version of the electrical telegraph which he demonstrated on 2 September 1837. Alfred Vail

Alfred Lewis Vail (September 25, 1807 – January 18, 1859) was an American machinist and inventor. Along with Samuel Morse, Vail was central in developing and commercializing American electrical telegraphy between 1837 and 1844.

Vail and Morse ...

saw this demonstration and joined Morse to develop the register—a telegraph terminal that integrated a logging device for recording messages to paper tape. This was demonstrated successfully over three miles (five kilometres) on 6 January 1838 and eventually over forty miles (sixty-four kilometres) between Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

, and Baltimore

Baltimore is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland. With a population of 585,708 at the 2020 census and estimated at 568,271 in 2024, it is the 30th-most populous U.S. city. The Baltimore metropolitan area is the 20th-large ...

on 24 May 1844. The patented invention proved lucrative and by 1851 telegraph lines in the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

spanned over . Morse's most important technical contribution to this telegraph was the simple and highly efficient Morse Code

Morse code is a telecommunications method which Character encoding, encodes Written language, text characters as standardized sequences of two different signal durations, called ''dots'' and ''dashes'', or ''dits'' and ''dahs''. Morse code i ...

, co-developed with Vail, which was an important advance over Wheatstone's more complicated and expensive system, and required just two wires. The communications efficiency of the Morse Code preceded that of the Huffman code in digital communications

Data communication, including data transmission and data reception, is the transfer of data, signal transmission, transmitted and received over a Point-to-point (telecommunications), point-to-point or point-to-multipoint communication chann ...

by over 100 years, but Morse and Vail developed the code purely empirical

Empirical evidence is evidence obtained through sense experience or experimental procedure. It is of central importance to the sciences and plays a role in various other fields, like epistemology and law.

There is no general agreement on how t ...

ly, with shorter codes for more frequent letters.

The submarine cable across the English Channel

The English Channel, also known as the Channel, is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that separates Southern England from northern France. It links to the southern part of the North Sea by the Strait of Dover at its northeastern end. It is the busi ...

, wire coated in gutta percha, was laid in 1851. Transatlantic cables installed in 1857 and 1858 only operated for a few days or weeks (carried messages of greeting back and forth between James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was the 15th president of the United States, serving from 1857 to 1861. He also served as the United States Secretary of State, secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and represented Pennsylvan ...

and Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in January 1901. Her reign of 63 year ...

) before they failed. The project to lay a replacement line was delayed for five years by the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

. The first successful transatlantic telegraph cable

Transatlantic telegraph cables were undersea cables running under the Atlantic Ocean for telegraph communications. Telegraphy is a largely obsolete form of communication, and the cables have long since been decommissioned, but telephone and dat ...

was completed on 27 July 1866, allowing continuous transatlantic telecommunication for the first time.

Telephone

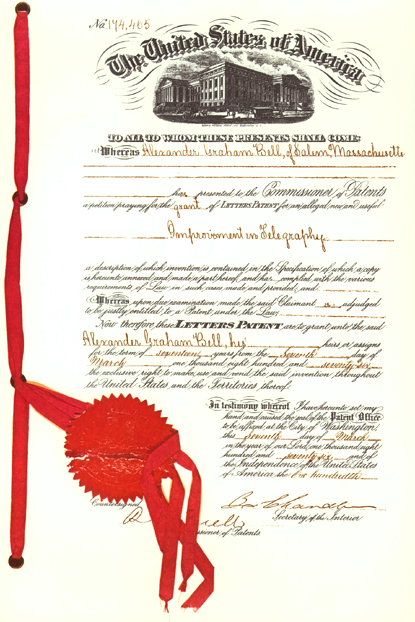

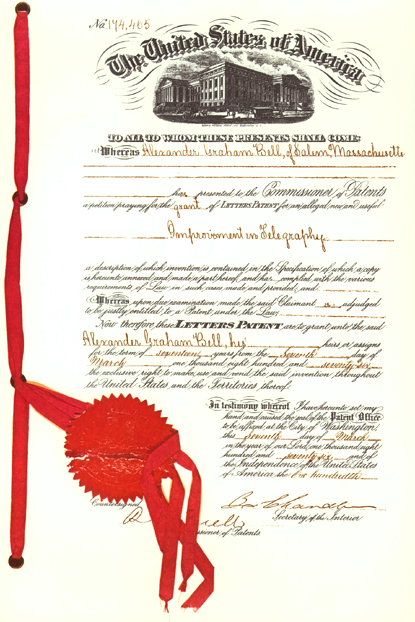

The electric telephone was invented in the 1870s, based on earlier work with harmonic (multi-signal) telegraphs. The first commercial telephone services were set up in 1878 and 1879 on both sides of the Atlantic in the cities of

The electric telephone was invented in the 1870s, based on earlier work with harmonic (multi-signal) telegraphs. The first commercial telephone services were set up in 1878 and 1879 on both sides of the Atlantic in the cities of New Haven

New Haven is a city of the U.S. state of Connecticut. It is located on New Haven Harbor on the northern shore of Long Island Sound. With a population of 135,081 as determined by the 2020 U.S. census, New Haven is the third largest city in Co ...

, Connecticut

Connecticut ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York (state), New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. ...

in the US and London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

, England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

in the UK. Alexander Graham Bell

Alexander Graham Bell (; born Alexander Bell; March 3, 1847 – August 2, 1922) was a Scottish-born Canadian Americans, Canadian-American inventor, scientist, and engineer who is credited with patenting the first practical telephone. He als ...

held the master patent for the telephone that was needed for such services in both countries. All other patents for electric telephone devices and features flowed from this master patent. Credit for the invention of the electric telephone has been frequently disputed, and new controversies over the issue have arisen from time-to-time. As with other great inventions such as radio, television, the light bulb, and the digital computer

A computer is a machine that can be programmed to automatically carry out sequences of arithmetic or logical operations (''computation''). Modern digital electronic computers can perform generic sets of operations known as ''programs'', wh ...

, there were several inventors who did pioneering experimental work on ''voice transmission over a wire'', who then improved on each other's ideas. However, the key innovators were Alexander Graham Bell and Gardiner Greene Hubbard

Gardiner Greene Hubbard (August 25, 1822 – December 11, 1897) was an American lawyer, financier, and community leader. He was a founder and first president of the National Geographic Society; a founder and the first president of the Bell Teleph ...

, who created the first telephone company, the Bell Telephone Company

The Bell Telephone Company was the initial corporate entity from which the Bell System originated to build a continental conglomerate and monopoly in telecommunication services in the United States and Canada.

The company was organized in Bost ...

in the United States, which later evolved into American Telephone & Telegraph

AT&T Corporation, an abbreviation for its former name, the American Telephone and Telegraph Company, was an American telecommunications company that provided voice, video, data, and Internet telecommunications and professional services to busi ...

(AT&T), at times the world's largest phone company.

Telephone technology grew quickly after the first commercial services emerged, with inter-city lines being built and telephone exchange

A telephone exchange, telephone switch, or central office is a central component of a telecommunications system in the public switched telephone network (PSTN) or in large enterprises. It facilitates the establishment of communication circuits ...

s in every major city of the United States by the mid-1880s. The first transcontinental telephone call occurred on January 25, 1915. Despite this, transatlantic voice communication remained impossible for customers until January 7, 1927, when a connection was established using radio. However no cable connection existed until TAT-1

TAT-1 (Transatlantic No. 1) was the first submarine transatlantic telephone cable system. It was laid between Kerrera, Oban, Scotland and Clarenville, Newfoundland. Two cables were laid between 1955 and 1956 with one cable for each direction. I ...

was inaugurated on September 25, 1956, providing 36 telephone circuits.

In 1880, Bell and co-inventor Charles Sumner Tainter

Charles Sumner Tainter (April 25, 1854 – April 20, 1940) was an American scientific instrument maker, engineer and inventor, best known for his collaborations with Alexander Graham Bell, Chichester Bell, Alexander's father-in-law Gardiner Hubba ...

conducted the world's first wireless telephone call via modulated lightbeams projected by photophone

The photophone is a telecommunications device that allows transmission of speech on a beam of light. It was invented jointly by Alexander Graham Bell and his assistant Charles Sumner Tainter on February 19, 1880, at Bell's laboratory at 1325 ...

s. The scientific principles of their invention would not be utilized for several decades, when they were first deployed in military and fiber-optic communication

Fiber-optic communication is a form of optical communication for transmitting information from one place to another by sending pulses of infrared or visible light through an optical fiber. The light is a form of carrier wave that is modul ...

s.

The first transatlantic ''telephone'' cable (which incorporated hundreds of electronic amplifier

An amplifier, electronic amplifier or (informally) amp is an electronic device that can increase the magnitude of a Signal (information theory), signal (a time-varying voltage or Electric current, current). It is a two-port network, two-port ...

s) was not operational until 1956, only six years before the first commercial telecommunications satellite, Telstar

Telstar refers to a series of communications satellites. The first two, Telstar 1 and Telstar 2, were experimental and nearly identical. Telstar 1 launched atop of a Thor-Delta rocket on July 10, 1962, successfully relayed the first televisi ...

, was launched into space.

Radio and television

Over several years starting in 1894, the Italian inventorGuglielmo Marconi

Guglielmo Giovanni Maria Marconi, 1st Marquess of Marconi ( ; ; 25 April 1874 – 20 July 1937) was an Italian electrical engineer, inventor, and politician known for his creation of a practical radio wave-based Wireless telegraphy, wireless tel ...

worked on adapting the newly discovered phenomenon of radio wave

Radio waves (formerly called Hertzian waves) are a type of electromagnetic radiation with the lowest frequencies and the longest wavelengths in the electromagnetic spectrum, typically with frequencies below 300 gigahertz (GHz) and wavelengths g ...

s to telecommunication, building the first wireless telegraphy system using them. In December 1901, he established wireless communication between St. John's, Newfoundland and Poldhu, Cornwall (England), earning him a Nobel Prize in Physics

The Nobel Prize in Physics () is an annual award given by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences for those who have made the most outstanding contributions to mankind in the field of physics. It is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the ...

(which he shared with Karl Braun) in 1909. In 1900, Reginald Fessenden

Reginald Aubrey Fessenden (October 6, 1866 – July 22, 1932) was a Canadian-American electrical engineer and inventor who received hundreds of List of Reginald Fessenden patents, patents in fields related to radio and sonar between 1891 and 1936 ...

was able to wirelessly transmit a human voice.

Millimetre wave

Extremely high frequency (EHF) is the International Telecommunication Union designation for the band of radio frequencies in the electromagnetic spectrum from 30 to 300 gigahertz (GHz). It is in the microwave part of the radio spectrum, between t ...

communication was first investigated by Bengali physicist Jagadish Chandra Bose

Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose (; ; 30 November 1858 – 23 November 1937) was a polymath with interests in biology, physics and writing science fiction. He was a pioneer in the investigation of radio microwave optics, made significant contributions ...

during 18941896, when he reached an extremely high frequency

Extremely high frequency (EHF) is the International Telecommunication Union designation for the band of radio frequencies in the electromagnetic spectrum from 30 to 300 gigahertz (GHz). It is in the microwave part of the radio spectrum, between t ...

of up to 60GHz

The hertz (symbol: Hz) is the unit of frequency in the International System of Units (SI), often described as being equivalent to one event (or Cycle per second, cycle) per second. The hertz is an SI derived unit whose formal expression in ter ...

in his experiments. He also introduced the use of semiconductor

A semiconductor is a material with electrical conductivity between that of a conductor and an insulator. Its conductivity can be modified by adding impurities (" doping") to its crystal structure. When two regions with different doping level ...

junctions to detect radio waves, when he patent

A patent is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the legal right to exclude others from making, using, or selling an invention for a limited period of time in exchange for publishing an sufficiency of disclosure, enabling discl ...

ed the radio

Radio is the technology of communicating using radio waves. Radio waves are electromagnetic waves of frequency between 3 hertz (Hz) and 300 gigahertz (GHz). They are generated by an electronic device called a transmitter connec ...

crystal detector

A crystal detector is an obsolete electronic component used in some early 20th century radio receivers. It consists of a piece of crystalline mineral that rectifies an alternating current radio signal. It was employed as a detector ( demod ...

in 1901.

In 1924, Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

ese engineer Kenjiro Takayanagi

was a Japanese engineer and a pioneer in the development of television. Although he failed to gain much recognition in the West, he built the world's first all-electronic television receiver, and is referred to as "the father of Japanese televis ...

began a research program on electronic television

Television (TV) is a telecommunication medium for transmitting moving images and sound. Additionally, the term can refer to a physical television set rather than the medium of transmission. Television is a mass medium for advertising, ...

. In 1925, he demonstrated a CRT

CRT or Crt most commonly refers to:

* Cathode-ray tube, a display

* Critical race theory, an academic framework of analysis

CRT may also refer to:

Law

* Charitable remainder trust, United States

* Civil Resolution Tribunal, Canada

* Columbia ...

television

Television (TV) is a telecommunication medium for transmitting moving images and sound. Additionally, the term can refer to a physical television set rather than the medium of transmission. Television is a mass medium for advertising, ...

with thermal electron emission. In 1926, he demonstrated a CRT television with 40-line resolution, the first working example of a fully electronic television

Television (TV) is a telecommunication medium for transmitting moving images and sound. Additionally, the term can refer to a physical television set rather than the medium of transmission. Television is a mass medium for advertising, ...

receiver. In 1927, he increased the television resolution to 100 lines, which was unrivaled until 1931. In 1928, he was the first to transmit human faces in half-tones on television, influencing the later work of Vladimir K. Zworykin

Vladimir Kosma Zworykin (1888/1889July 29, 1982) was a Russian-American inventor, engineer, and pioneer of television technology. Zworykin invented a television transmitting and receiving system employing cathode-ray tubes. He played a role in t ...

.

On March 25, 1925, Scottish inventor John Logie Baird

John Logie Baird (; 13 August 188814 June 1946) was a Scottish inventor, electrical engineer, and innovator who demonstrated the world's first mechanical Mechanical television, television system on 26 January 1926. He went on to invent the fi ...

publicly demonstrated the transmission

Transmission or transmit may refer to:

Science and technology

* Power transmission

** Electric power transmission

** Transmission (mechanical device), technology that allows controlled application of power

*** Automatic transmission

*** Manual tra ...

of moving silhouette pictures at the London department store Selfridge's. Baird's system relied upon the fast-rotating Nipkow disk

A Nipkow disk (sometimes Anglicized as Nipkov disk; patented in 1884), also known as scanning disk, is a mechanical, rotating, geometrically operating image scanning device, patented by Paul Gottlieb Nipkow in Berlin. This scanning disk was a f ...

, and thus it became known as the mechanical television

Mechanical television or mechanical scan television is an obsolete television system that relies on a mechanism (engineering), mechanical scanning device, such as a rotating disk with holes in it or a rotating mirror drum, to scan the scene and ...

. In October 1925, Baird was successful in obtaining moving pictures with halftone

Halftone is the reprographic technique that simulates continuous tone, continuous-tone imagery through the use of dots, varying either in size or in spacing, thus generating a gradient-like effect.Campbell, Alastair. ''The Designer's Lexicon''. ...

shades, which were by most accounts the first true television pictures. This led to a public demonstration of the improved device on 26 January 1926 again at Selfridges

Selfridges, also known as Selfridges & Co., is a chain of upmarket department stores in the United Kingdom that is operated by Selfridges Retail Limited. It was founded by Harry Gordon Selfridge in 1908. The historic Daniel Burnham-designed Self ...

. His invention formed the basis of semi-experimental broadcasts done by the British Broadcasting Corporation

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public broadcasting, public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved in ...

beginning September 30, 1929.

For most of the twentieth century televisions used the cathode ray tube

A cathode-ray tube (CRT) is a vacuum tube containing one or more electron guns, which emit electron beams that are manipulated to display images on a phosphorescent screen. The images may represent electrical waveforms on an oscilloscope, a ...

(CRT) invented by Karl Braun. Such a television was produced by Philo Farnsworth

Philo Taylor Farnsworth (August 19, 1906 – March 11, 1971), "The father of television", was the American inventor and pioneer who was granted the first patent for the television by the United States Government.

Burns, R. W. (1998), ''Televisi ...

, who demonstrated crude silhouette images to his family in Idaho on September 7, 1927. Farnsworth's device would compete with the concurrent work of Kalman Tihanyi and Vladimir Zworykin

Vladimir Kosma Zworykin (1888/1889July 29, 1982) was a Russian-American inventor, engineer, and pioneer of television technology. Zworykin invented a television transmitting and receiving system employing cathode-ray tubes. He played a role in t ...

. Though the execution of the device was not yet what everyone hoped it could be, it earned Farnsworth a small production company. In 1934, he gave the first public demonstration of the television at Philadelphia's Franklin Institute and opened his own broadcasting station. Zworykin's camera, based on Tihanyi's Radioskop, which later would be known as the Iconoscope

The iconoscope (from the Greek Language, Greek: ''εἰκών'' "image" and ''σκοπεῖν'' "to look, to see") was the first practical video camera tube to be used in early television cameras. The iconoscope produced a much stronger signal tha ...

, had the backing of the influential Radio Corporation of America

RCA Corporation was a major American electronics company, which was founded in 1919 as the Radio Corporation of America. It was initially a patent pool, patent trust owned by General Electric (GE), Westinghouse Electric Corporation, Westinghou ...

(RCA). In the United States, court action between Farnsworth and RCA would resolve in Farnsworth's favour. John Logie Baird

John Logie Baird (; 13 August 188814 June 1946) was a Scottish inventor, electrical engineer, and innovator who demonstrated the world's first mechanical Mechanical television, television system on 26 January 1926. He went on to invent the fi ...

switched from mechanical television and became a pioneer of colour television using cathode-ray tubes.

After mid-century the spread of coaxial cable and microwave radio relay

Microwave transmission is the Data transmission, transmission of information by electromagnetic waves with wavelengths in the microwave frequency range of 300 MHz to 300 GHz (1 m - 1 mm wavelength) of the electromagnetic spectrum ...

allowed television network

A television broadcaster or television network is a telecommunications network for the distribution of television show, television content, where a central operation provides programming to many television stations, pay television providers or ...

s to spread across even large countries.

Semiconductor era

The modern period of telecommunication history from 1950 onwards is referred to as thesemiconductor

A semiconductor is a material with electrical conductivity between that of a conductor and an insulator. Its conductivity can be modified by adding impurities (" doping") to its crystal structure. When two regions with different doping level ...

era, due to the wide adoption of semiconductor devices

A semiconductor device is an electronic component that relies on the electronics, electronic properties of a semiconductor material (primarily silicon, germanium, and gallium arsenide, as well as organic semiconductors) for its function. Its co ...

in telecommunication technology. The development of transistor

A transistor is a semiconductor device used to Electronic amplifier, amplify or electronic switch, switch electrical signals and electric power, power. It is one of the basic building blocks of modern electronics. It is composed of semicondu ...

technology and the semiconductor industry

The semiconductor industry is the aggregate of companies engaged in the design and fabrication of semiconductors and semiconductor devices, such as transistors and integrated circuits. Its roots can be traced to the invention of the transistor ...

enabled significant advances in telecommunication technology, led to the price of telecommunications services declining significantly, and led to a transition away from state-owned narrowband

Narrowband signals are signals that occupy a narrow range of frequencies or that have a small fractional bandwidth. In the audio spectrum, ''narrowband sounds'' are sounds that occupy a narrow range of frequencies. In telephony, narrowband is ...

circuit-switched network

Circuit switching is a method of implementing a telecommunications network in which two network nodes establish a dedicated communications channel ( circuit) through the network before the nodes may communicate. The circuit guarantees the full ...

s to private broadband

In telecommunications, broadband or high speed is the wide-bandwidth (signal processing), bandwidth data transmission that exploits signals at a wide spread of frequencies or several different simultaneous frequencies, and is used in fast Inter ...

packet-switched network

In telecommunications, packet switching is a method of grouping data into short messages in fixed format, i.e. '' packets,'' that are transmitted over a digital network. Packets consist of a header and a payload. Data in the header is used b ...

s. In turn, this led to a significant increase in the total number of telephone subscribers, reaching nearly 1billion users worldwide by the end of the 20th century.

The development of metal–oxide–semiconductor

upright=1.3, Two power MOSFETs in amperes">A in the ''on'' state, dissipating up to about 100 watt">W and controlling a load of over 2000 W. A matchstick is pictured for scale.

In electronics, the metal–oxide–semiconductor field- ...

(MOS) large-scale integration

An integrated circuit (IC), also known as a microchip or simply chip, is a set of electronic circuits, consisting of various electronic components (such as transistors, resistors, and capacitors) and their interconnections. These components a ...

(LSI) technology, information theory

Information theory is the mathematical study of the quantification (science), quantification, Data storage, storage, and telecommunications, communication of information. The field was established and formalized by Claude Shannon in the 1940s, ...

and cellular network

A cellular network or mobile network is a telecommunications network where the link to and from end nodes is wireless network, wireless and the network is distributed over land areas called ''cells'', each served by at least one fixed-locatio ...

ing led to the development of affordable mobile communications. There was a rapid growth of the telecommunications industry

The telecommunications industry within the sector of information and communication technology comprises all telecommunication/ telephone companies and Internet service providers, and plays a crucial role in the evolution of mobile communications ...

towards the end of the 20th century, primarily due to the introduction of digital signal processing

Digital signal processing (DSP) is the use of digital processing, such as by computers or more specialized digital signal processors, to perform a wide variety of signal processing operations. The digital signals processed in this manner are a ...

in wireless communications, driven by the development of low-cost, very large-scale integration

Very may refer to:

* English's prevailing intensifier

Businesses

* The Very Group, a British retail/consumer finance corporation

** Very (online retailer), their main e-commerce brand

* VERY TV, a Thai television channel

Places

* Véry, ...

(VLSI) RF CMOS

RF CMOS is a metal–oxide–semiconductor (MOS) integrated circuit (IC) technology that integrates radio-frequency (RF), analog and digital electronics on a mixed-signal CMOS (complementary MOS) RF circuit chip. It is widely used in modern wir ...

(radio-frequency complementary MOS

Complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor (CMOS, pronounced "sea-moss

", , ) is a type of metal–oxide–semiconductor field-effect transistor (MOSFET) fabrication process that uses complementary and symmetrical pairs of p-type and n-type ...

) technology.

Videotelephony

The development ofvideotelephony

Videotelephony (also known as videoconferencing or video calling) is the use of audio signal, audio and video for simultaneous two-way communication. Today, videotelephony is widespread. There are many terms to refer to videotelephony. ''Vide ...

involved the historical development of several technologies which enabled the use of live video in addition to voice telecommunications. The concept of videotelephony was first popularized in the late 1870s in both the United States and Europe, although the basic sciences to permit its very earliest trials would take nearly a half century to be discovered. This was first embodied in the device which came to be known as the video telephone, or videophone, and it evolved from intensive research and experimentation in several telecommunication fields, notably electrical telegraphy

Electrical telegraphy is point-to-point distance communicating via sending electric signals over wire, a system primarily used from the 1840s until the late 20th century. It was the first electrical telecommunications system and the most wide ...

, telephony

Telephony ( ) is the field of technology involving the development, application, and deployment of telecommunications services for the purpose of electronic transmission of voice, fax, or data, between distant parties. The history of telephony is ...

, radio

Radio is the technology of communicating using radio waves. Radio waves are electromagnetic waves of frequency between 3 hertz (Hz) and 300 gigahertz (GHz). They are generated by an electronic device called a transmitter connec ...

, and television

Television (TV) is a telecommunication medium for transmitting moving images and sound. Additionally, the term can refer to a physical television set rather than the medium of transmission. Television is a mass medium for advertising, ...

.

The development of the crucial video technology first started in the latter half of the 1920s in the United Kingdom and the United States, spurred notably by John Logie Baird

John Logie Baird (; 13 August 188814 June 1946) was a Scottish inventor, electrical engineer, and innovator who demonstrated the world's first mechanical Mechanical television, television system on 26 January 1926. He went on to invent the fi ...

and AT&T's Bell Labs. This occurred in part, at least by AT&T, to serve as an adjunct supplementing the use of the telephone. A number of organizations believed that videotelephony would be superior to plain voice communications. However, video technology was to be deployed in analog television broadcasting

A television broadcaster or television network is a telecommunications network for the distribution of television content, where a central operation provides programming to many television stations, pay television providers or, in the United ...

long before it could become practical—or popular—for videophones.

Videotelephony developed in parallel with conventional voice telephone systems from the mid-to-late 20th century. Only in the late 20th century with the advent of powerful video codec

A video codec is software or Computer hardware, hardware that data compression, compresses and Uncompressed video, decompresses digital video. In the context of video compression, ''codec'' is a portmanteau of ''encoder'' and ''decoder'', while ...

s and high-speed broadband did it become a practical technology for regular use. With the rapid improvements and popularity of the Internet, it became widespread through the use of videoconferencing

Videotelephony (also known as videoconferencing or video calling) is the use of audio signal, audio and video for simultaneous two-way communication. Today, videotelephony is widespread. There are many terms to refer to videotelephony. ''Vide ...

and webcam

A webcam is a video camera which is designed to record or stream to a computer or computer network. They are primarily used in Videotelephony, video telephony, live streaming and social media, and Closed-circuit television, security. Webcams can b ...

s, which frequently utilize Internet telephony

Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP), also known as IP telephony, is a set of technologies used primarily for voice communication sessions over Internet Protocol (IP) networks, such as the Internet. VoIP enables voice calls to be transmitted as ...

, and in business, where telepresence technology has helped reduce the need to travel.

Practical digital videotelephony was only made possible with advances in video compression

In information theory, data compression, source coding, or bit-rate reduction is the process of encoding information using fewer bits than the original representation. Any particular compression is either lossy or lossless. Lossless compression ...

, due to the impractically high bandwidth requirements of uncompressed video

Uncompressed video is digital video that either has never been compressed or was generated by decompressing previously compressed digital video. It is commonly used by video cameras, video monitors, video recording devices (including general-pur ...

. To achieve Video Graphics Array

Video Graphics Array (VGA) is a video display controller and accompanying de facto graphics standard, first introduced with the IBM PS/2 line of computers in 1987, which became ubiquitous in the IBM PC compatible industry within three years. T ...

(VGA) quality video (480p

480p is the shorthand name for a family of video display resolutions. The p stands for progressive scan, i.e. non-interlaced. The ''480'' denotes a vertical resolution of 480 pixels, usually with a horizontal resolution of 640 pixels and 4:3 a ...

resolution and 256 colors) with raw uncompressed video, it would require a bandwidth of over 92Mbps

In telecommunications, data transfer rate is the average number of bits (bitrate), characters or symbols ( baudrate), or data blocks per unit time passing through a communication link in a data-transmission system. Common data rate units are mul ...

.

Satellite

The first U.S. satellite to relay communications wasProject SCORE

SCORE (Signal Communications by Orbiting Relay Equipment) was the world's first purpose-built communications satellite. Launched aboard an American Atlas rocket on December 18, 1958, SCORE provided the first broadcast of a human voice from spa ...

in 1958, which used a tape recorder to store and forward

Store and forward is a telecommunications technique in which information is sent to an intermediate station where it is kept and sent at a later time to the final destination or to another intermediate station. The intermediate station, or node in ...

voice messages. It was used to send a Christmas greeting to the world from U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

. In 1960 NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the federal government of the United States, US federal government responsible for the United States ...

launched an Echo satellite; the aluminized PET film balloon served as a passive reflector for radio communications. Courier 1B, built by Philco

Philco (an acronym for Philadelphia Battery Company) is an American electronics industry, electronics manufacturer headquartered in Philadelphia. Philco was a pioneer in battery, radio, and television production. In 1961, the company was purchase ...

, also launched in 1960, was the world's first active repeater satellite. Satellites these days are used for many applications such as GPS, television, internet and telephone.

Telstar

Telstar refers to a series of communications satellites. The first two, Telstar 1 and Telstar 2, were experimental and nearly identical. Telstar 1 launched atop of a Thor-Delta rocket on July 10, 1962, successfully relayed the first televisi ...

was the first active, direct relay commercial communications satellite

A communications satellite is an artificial satellite that relays and amplifies radio telecommunication signals via a Transponder (satellite communications), transponder; it creates a communication channel between a source transmitter and a Rad ...

. Belonging to AT&T

AT&T Inc., an abbreviation for its predecessor's former name, the American Telephone and Telegraph Company, is an American multinational telecommunications holding company headquartered at Whitacre Tower in Downtown Dallas, Texas. It is the w ...

as part of a multi-national agreement between AT&T, Bell Telephone Laboratories

Nokia Bell Labs, commonly referred to as ''Bell Labs'', is an American industrial research and development company owned by Finnish technology company Nokia. With headquarters located in Murray Hill, New Jersey, Murray Hill, New Jersey, the compa ...

, NASA, the British General Post Office

The General Post Office (GPO) was the state postal system and telecommunications carrier of the United Kingdom until 1969. Established in England in the 17th century, the GPO was a state monopoly covering the dispatch of items from a specific ...

, and the French National PTT (Post Office) to develop satellite communications, it was launched by NASA from Cape Canaveral

Cape Canaveral () is a cape (geography), cape in Brevard County, Florida, in the United States, near the center of the state's Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coast. Officially Cape Kennedy from 1963 to 1973, it lies east of Merritt Island, separated ...

on July 10, 1962, the first privately sponsored space launch. Relay 1

The Relay program consisted of Relay 1 and Relay 2, two early American satellites in elliptical medium Earth orbit. Both were primarily experimental communications satellites funded by NASA and developed by RCA. As of December 2, 2016, both sate ...

was launched on December 13, 1962, and became the first satellite to broadcast across the Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is bounded by the cont ...

on November 22, 1963.

The first and historically most important application for communication satellites was in intercontinental long-distance telephony. The fixed Public Switched Telephone Network

The public switched telephone network (PSTN) is the aggregate of the world's telephone networks that are operated by national, regional, or local telephony operators. It provides infrastructure and services for public telephony. The PSTN consists o ...

relays telephone call

A telephone call, phone call, voice call, or simply a call, is the effective use of a connection over a telephone network between the calling party and the called party.

Telephone calls are the form of human communication that was first enabl ...

s from land line telephones to an earth station

A ground station, Earth station, or Earth terminal is a terrestrial radio station designed for extraplanetary telecommunication with spacecraft (constituting part of the ground segment of the spacecraft system), or reception of radio waves fro ...

, where they are then transmitted a receiving satellite dish

A satellite dish is a dish-shaped type of parabolic antenna designed to receive or transmit information by radio waves to or from a communication satellite. The term most commonly means a dish which receives direct-broadcast satellite televisio ...

via a geostationary satellite in Earth orbit. Improvements in submarine communications cable

A submarine communications cable is a cable laid on the seabed between land-based stations to carry telecommunication signals across stretches of ocean and sea. The first submarine communications cables were laid beginning in the 1850s and car ...

s, through the use of fiber-optics, caused some decline in the use of satellites for fixed telephony in the late 20th century, but they still exclusively service remote islands such as Ascension Island

Ascension Island is an isolated volcanic island, 7°56′ south of the Equator in the Atlantic Ocean, South Atlantic Ocean. It is about from the coast of Africa and from the coast of South America. It is governed as part of the British Overs ...

, Saint Helena

Saint Helena (, ) is one of the three constituent parts of Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha, a remote British overseas territory.

Saint Helena is a volcanic and tropical island, located in the South Atlantic Ocean, some 1,874 km ...

, Diego Garcia

Diego Garcia is the largest island of the Chagos Archipelago. It has been used as a joint UK–U.S. military base since the 1970s, following the expulsion of the Chagossians by the UK government. The Chagos Islands are set to become a former B ...

, and Easter Island

Easter Island (, ; , ) is an island and special territory of Chile in the southeastern Pacific Ocean, at the southeasternmost point of the Polynesian Triangle in Oceania. The island is renowned for its nearly 1,000 extant monumental statues, ...

, where no submarine cables are in service. There are also some continents and some regions of countries where landline telecommunications are rare to nonexistent, for example Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean (also known as the Antarctic Ocean), it contains the geographic South Pole. ...

, plus large regions of Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

, South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a considerably smaller portion in the Northern Hemisphere. It can also be described as the southern Subregion#Americas, subregion o ...

, Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surfac ...

, Northern Canada

Northern Canada (), colloquially the North or the Territories, is the vast northernmost region of Canada, variously defined by geography and politics. Politically, the term refers to the three Provinces_and_territories_of_Canada#Territories, terr ...

, China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

, Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

and Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous territory in the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. It is by far the largest geographically of three constituent parts of the kingdom; the other two are metropolitan Denmark and the Faroe Islands. Citizens of Greenlan ...

.

After commercial long-distance telephone service was established via communication satellites, a host of other commercial telecommunications were also adapted to similar satellites starting in 1979, including mobile satellite phones, satellite radio

Satellite radio is defined by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU)'s ITU Radio Regulations (RR) as a '' broadcasting-satellite service''. The satellite's signals are broadcast nationwide, across a much wider geographical area than te ...

, satellite television

Satellite television is a service that delivers television programming to viewers by relaying it from a communications satellite orbiting the Earth directly to the viewer's location.ITU Radio Regulations, Section IV. Radio Stations and Systems ...

and satellite Internet access

Satellite Internet access is Internet access provided through communication satellites; if it can sustain high-speed Internet, high speeds, it is termed satellite broadband. Modern consumer grade satellite Internet service is typically provide ...

. The earliest adaption for most such services occurred in the 1990s as the pricing for commercial satellite transponder channels continued to drop significantly.

Realization and demonstration, on October 29, 2001, of the first digital cinema

Digital cinema is the digital technology used within the film industry to distribute or project motion pictures as opposed to the historical use of reels of motion picture film, such as 35 mm film. Whereas film reels have to be shipped to mo ...

transmission by satellite

A satellite or an artificial satellite is an object, typically a spacecraft, placed into orbit around a celestial body. They have a variety of uses, including communication relay, weather forecasting, navigation ( GPS), broadcasting, scient ...

in Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

of a feature film

A feature film or feature-length film (often abbreviated to feature), also called a theatrical film, is a film (Film, motion picture, "movie" or simply “picture”) with a running time long enough to be considered the principal or sole present ...

by Bernard Pauchon, Alain Lorentz, Raymond Melwig and Philippe Binant.

Computer networks and the Internet

On September 11, 1940,George Stibitz

George Robert Stibitz (April 30, 1904 – January 31, 1995) was an American researcher at Bell Labs who is internationally recognized as one of the fathers of the modern digital computer. He was known for his work in the 1930s and 1940s on the r ...

was able to transmit problems using teletype

A teleprinter (teletypewriter, teletype or TTY) is an electromechanical device that can be used to send and receive typed messages through various communications channels, in both point-to-point and point-to-multipoint configurations.

Init ...

to his Complex Number Calculator in New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

and receive the computed results back at Dartmouth College

Dartmouth College ( ) is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Hanover, New Hampshire, United States. Established in 1769 by Eleazar Wheelock, Dartmouth is one of the nine colonial colleges chartered before the America ...

in New Hampshire

New Hampshire ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec t ...

. This configuration of a centralized computer or mainframe

A mainframe computer, informally called a mainframe or big iron, is a computer used primarily by large organizations for critical applications like bulk data processing for tasks such as censuses, industry and consumer statistics, enterpris ...

with remote dumb terminals remained popular throughout the 1950s. However, it was not until the 1960s that researchers started to investigate packet switching

In telecommunications, packet switching is a method of grouping Data (computing), data into short messages in fixed format, i.e. ''network packet, packets,'' that are transmitted over a digital Telecommunications network, network. Packets consi ...

a technology that would allow chunks of data to be sent to different computers without first passing through a centralized mainframe. A four-node network emerged on December 5, 1969, between the University of California, Los Angeles

The University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) is a public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Los Angeles, California, United States. Its academic roots were established in 1881 as a normal school the ...

, the Stanford Research Institute

SRI International (SRI) is a nonprofit organization, nonprofit scientific research, scientific research institute and organization headquartered in Menlo Park, California, United States. It was established in 1946 by trustees of Stanford Univer ...

, the University of Utah

The University of Utah (the U, U of U, or simply Utah) is a public university, public research university in Salt Lake City, Utah, United States. It was established in 1850 as the University of Deseret (Book of Mormon), Deseret by the General A ...

and the University of California, Santa Barbara

The University of California, Santa Barbara (UC Santa Barbara or UCSB) is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Santa Barbara County, California, United States. Tracing its roots back to 1891 as an ...

. This network would become ARPANET

The Advanced Research Projects Agency Network (ARPANET) was the first wide-area packet-switched network with distributed control and one of the first computer networks to implement the TCP/IP protocol suite. Both technologies became the tec ...

, which by 1981 would consist of 213 nodes. In June 1973, the first non-US node was added to the network belonging to Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the archipelago of Svalbard also form part of the Kingdom of ...

's NORSAR project. This was shortly followed by a node in London.

ARPANET's development centred on the Request for Comments

A Request for Comments (RFC) is a publication in a series from the principal technical development and standards-setting bodies for the Internet, most prominently the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF). An RFC is authored by individuals or ...

process and on April 7, 1969, RFC 1 was published. This process is important because ARPANET would eventually merge with other networks to form the Internet

The Internet (or internet) is the Global network, global system of interconnected computer networks that uses the Internet protocol suite (TCP/IP) to communicate between networks and devices. It is a internetworking, network of networks ...

and many of the protocols the Internet relies upon today were specified through this process. The first Transmission Control Protocol

The Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) is one of the main communications protocol, protocols of the Internet protocol suite. It originated in the initial network implementation in which it complemented the Internet Protocol (IP). Therefore, th ...

(TCP) specification, (''Specification of Internet Transmission Control Program''), was written by Vinton Cerf, Yogen Dalal, and Carl Sunshine, and published in December 1974. It coined the term "Internet" as a shorthand for internetworking. In September 1981, RFC 791 introduced the Internet Protocol

The Internet Protocol (IP) is the network layer communications protocol in the Internet protocol suite for relaying datagrams across network boundaries. Its routing function enables internetworking, and essentially establishes the Internet.

IP ...

v4 (IPv4). This established the TCP/IP

The Internet protocol suite, commonly known as TCP/IP, is a framework for organizing the communication protocols used in the Internet and similar computer networks according to functional criteria. The foundational protocols in the suite are ...

protocol, which much of the Internet relies upon today. The User Datagram Protocol

In computer networking, the User Datagram Protocol (UDP) is one of the core communication protocols of the Internet protocol suite used to send messages (transported as datagrams in Network packet, packets) to other hosts on an Internet Protoco ...

(UDP), a more relaxed transport protocol that, unlike TCP, did not guarantee the orderly delivery of packets, was submitted on 28 August 1980 as RFC 768. An e-mail protocol, SMTP

The Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP) is an Internet standard communication protocol for electronic mail transmission. Mail servers and other message transfer agents use SMTP to send and receive mail messages. User-level email clients typi ...

, was introduced in August 1982 by RFC 821 and http://1.0 a protocol that would make the hyperlinked Internet possible was introduced in May 1996 by RFC 1945.

However, not all important developments were made through the Request for Comments process. Two popular link protocols for local area network

A local area network (LAN) is a computer network that interconnects computers within a limited area such as a residence, campus, or building, and has its network equipment and interconnects locally managed. LANs facilitate the distribution of da ...

s (LANs) also appeared in the 1970s. A patent for the Token Ring

Token Ring is a Physical layer, physical and data link layer computer networking technology used to build local area networks. It was introduced by IBM in 1984, and standardized in 1989 as IEEE Standards Association, IEEE 802.5. It uses a sp ...

protocol was filed by Olof Söderblom on October 29, 1974. And a paper on the Ethernet

Ethernet ( ) is a family of wired computer networking technologies commonly used in local area networks (LAN), metropolitan area networks (MAN) and wide area networks (WAN). It was commercially introduced in 1980 and first standardized in 198 ...

protocol was published by Robert Metcalfe

Robert "Bob" Melancton Metcalfe (born April 7, 1946) is an American engineer and entrepreneur who contributed to the development of the internet in the 1970s. He co-invented Ethernet, co-founded 3Com, and formulated Metcalfe's law, which desc ...

and David Boggs

David Reeves Boggs (June 17, 1950 – February 19, 2022) was an American electrical and radio engineer who developed early prototypes of Internet protocols, file servers, gateways, network interface cards and, along with Robert Metcalfe and o ...

in the July 1976 issue of ''Communications of the ACM

''Communications of the ACM'' (''CACM'') is the monthly journal of the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM).

History

It was established in 1958, with Saul Rosen as its first managing editor. It is sent to all ACM members.

Articles are i ...

''. The Ethernet protocol had been inspired by the ALOHAnet protocol which had been developed by electrical engineering

Electrical engineering is an engineering discipline concerned with the study, design, and application of equipment, devices, and systems that use electricity, electronics, and electromagnetism. It emerged as an identifiable occupation in the l ...

researchers at the University of Hawaii

A university () is an educational institution, institution of tertiary education and research which awards academic degrees in several Discipline (academia), academic disciplines. ''University'' is derived from the Latin phrase , which roughly ...

.

Internet access

Internet access is a facility or service that provides connectivity for a computer, a computer network, or other network device to the Internet, and for individuals or organizations to access or use applications such as email and the World Wide ...

became widespread late in the century, using the old telephone and television networks.

Digital telephone technology

MOS technology was initially overlooked by Bell because they did not find it practical for analog telephone applications. MOS technology eventually became practical for telephone applications with the MOSmixed-signal integrated circuit

A mixed-signal integrated circuit is any integrated circuit that has both analog circuits and digital circuits on a single semiconductor die.digital signal processing

Digital signal processing (DSP) is the use of digital processing, such as by computers or more specialized digital signal processors, to perform a wide variety of signal processing operations. The digital signals processed in this manner are a ...

on a single chip, developed by former Bell engineer David A. Hodges with Paul R. Gray at UC Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California), is a public land-grant research university in Berkeley, California, United States. Founded in 1868 and named after the Anglo-Irish philosopher George Berkele ...

in the early 1970s. In 1974, Hodges and Gray worked with R.E. Suarez to develop MOS switched capacitor

A switched capacitor (SC) is an electronic circuit that implements a function by moving charges into and out of capacitors when electronic switches are opened and closed. Usually, non-overlapping clock signals are used to control the switches ...

(SC) circuit technology, which they used to develop the digital-to-analog converter

In electronics, a digital-to-analog converter (DAC, D/A, D2A, or D-to-A) is a system that converts a digital signal into an analog signal. An analog-to-digital converter (ADC) performs the reverse function.

DACs are commonly used in musi ...

(DAC) chip, using MOSFETs and MOS capacitor

upright=1.3, Two power MOSFETs in amperes">A in the ''on'' state, dissipating up to about 100 watt">W and controlling a load of over 2000 W. A matchstick is pictured for scale.

In electronics, the metal–oxide–semiconductor field- ...

s for data conversion. This was followed by the analog-to-digital converter

In electronics, an analog-to-digital converter (ADC, A/D, or A-to-D) is a system that converts an analog signal, such as a sound picked up by a microphone or light entering a digital camera, into a Digital signal (signal processing), digi ...

(ADC) chip, developed by Gray and J. McCreary in 1975.

MOS SC circuits led to the development of PCM codec-filter chips in the late 1970s. The silicon-gate

In semiconductor electronics fabrication technology, a self-aligned gate is a transistor manufacturing approach whereby the gate electrode of a MOSFET (metal–oxide–semiconductor field-effect transistor) is used as a mask for the doping of the ...

CMOS

Complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor (CMOS, pronounced "sea-moss

", , ) is a type of MOSFET, metal–oxide–semiconductor field-effect transistor (MOSFET) semiconductor device fabrication, fabrication process that uses complementary an ...

(complementary MOS) PCM codec-filter chip, developed by Hodges and W.C. Black in 1980, has since been the industry standard for digital telephony. By the 1990s, telecommunication network

A telecommunications network is a group of nodes interconnected by telecommunications links that are used to exchange messages between the nodes. The links may use a variety of technologies based on the methodologies of circuit switching, messa ...

s such as the public switched telephone network

The public switched telephone network (PSTN) is the aggregate of the world's telephone networks that are operated by national, regional, or local telephony operators. It provides infrastructure and services for public telephony. The PSTN consists o ...