Humphrey Of Lancaster, Duke Of Gloucester on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Humphrey of Lancaster, Duke of Gloucester (3 October 1390 – 23 February 1447) was an English

He joined Henry V's campaigns in France. Before embarking, the army camped at Southampton, where the

He joined Henry V's campaigns in France. Before embarking, the army camped at Southampton, where the

After inheriting the manor of

After inheriting the manor of

In

In

prince

A prince is a male ruler (ranked below a king, grand prince, and grand duke) or a male member of a monarch's or former monarch's family. ''Prince'' is also a title of nobility (often highest), often hereditary, in some European states. The ...

, soldier and literary patron

Patronage is the support, encouragement, privilege, or financial aid that an organization or individual bestows on another. In the history of art, art patronage refers to the support that princes, popes, and other wealthy and influential people ...

. He was (as he styled himself) "son, brother and uncle of kings", being the fourth and youngest son of Henry IV of England

Henry IV ( – 20 March 1413), also known as Henry Bolingbroke, was King of England from 1399 to 1413. Henry was the son of John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster (a son of King Edward III), and Blanche of Lancaster.

Henry was involved in the 1388 ...

, the brother of Henry V Henry V may refer to:

People

* Henry V, Duke of Bavaria (died 1026)

* Henry V, Holy Roman Emperor (1081/86–1125)

* Henry V, Duke of Carinthia (died 1161)

* Henry V, Count Palatine of the Rhine (–1227)

* Henry V, Count of Luxembourg (1216–1281 ...

, and the uncle of Henry VI. Gloucester fought in the Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War (; 1337–1453) was a conflict between the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England and Kingdom of France, France and a civil war in France during the Late Middle Ages. It emerged from feudal disputes over the Duchy ...

and acted as Lord Protector

Lord Protector (plural: ''Lords Protector'') is a title that has been used in British constitutional law for the head of state. It was also a particular title for the British heads of state in respect to the established church. It was sometime ...

of England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

during the minority of his nephew. A controversial figure, he has been characterised as reckless, unprincipled, and fractious, but is also noted for his intellectual activity and for being the first significant English patron of humanism

Humanism is a philosophy, philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and Agency (philosophy), agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The me ...

, in the context of the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

.

Unlike his brothers, Humphrey was given no major military command by his father, instead receiving an intellectual upbringing. Created Duke of Gloucester

Duke of Gloucester ( ) is a British royal title (after Gloucester), often conferred on one of the sons of the reigning monarch. The first four creations were in the Peerage of England and the last in the Peerage of the United Kingdom; the curre ...

in 1414, he participated in Henry V's campaigns during the Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War (; 1337–1453) was a conflict between the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England and Kingdom of France, France and a civil war in France during the Late Middle Ages. It emerged from feudal disputes over the Duchy ...

in France: he fought at Agincourt in 1415 and at the conquest of Normandy

Normandy (; or ) is a geographical and cultural region in northwestern Europe, roughly coextensive with the historical Duchy of Normandy.

Normandy comprises Normandy (administrative region), mainland Normandy (a part of France) and insular N ...

in 1417–9. Following the king's death in 1422, Gloucester became one of the leading figures in the regency government of the infant Henry VI. He proved a rash, impulsive, unscrupulous and troublesome figure, he quarrelled constantly with his brother, John, Duke of Bedford

John of Lancaster, Duke of Bedford (20 June 1389 – 14 September 1435) was a medieval English prince, general, and statesman who commanded England's armies in France during a critical phase of the Hundred Years' War. Bedford was the third son ...

and uncle, Cardinal

Cardinal or The Cardinal most commonly refers to

* Cardinalidae, a family of North and South American birds

**''Cardinalis'', genus of three species in the family Cardinalidae

***Northern cardinal, ''Cardinalis cardinalis'', the common cardinal of ...

Henry Beaufort

Henry Beaufort (c. 1375 – 11 April 1447) was an English Catholic prelate and statesman who held the offices of Bishop of Lincoln (1398), Bishop of Winchester (1404) and cardinal (1426). He served three times as Lord Chancellor and played an ...

and went so far as to violently prosecute a dispute with the Duke of Burgundy

Duke of Burgundy () was a title used by the rulers of the Duchy of Burgundy, from its establishment in 843 to its annexation by the Crown lands of France, French crown in 1477, and later by members of the House of Habsburg, including Holy Roman E ...

, a key English ally in France, over conflicting claims to lands in the Low Countries

The Low Countries (; ), historically also known as the Netherlands (), is a coastal lowland region in Northwestern Europe forming the lower Drainage basin, basin of the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta and consisting today of the three modern "Bene ...

.

Humphrey was the exemplar of the romantic chivalric persona. Mettled and courageous, he was a foil for the countess Jacqueline of Hainaut, his first wife. His learned, widely read, scholarly approach to the early renaissance cultural expansion demonstrated the quintessential well-rounded princely character. He was a paragon for Eton College

Eton College ( ) is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school providing boarding school, boarding education for boys aged 13–18, in the small town of Eton, Berkshire, Eton, in Berkshire, in the United Kingdom. It has educated Prime Mini ...

and an exemplar for the University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a collegiate university, collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the List of oldest un ...

, accomplished, diplomatic, with political cunning. Despite the errors in his public and private life and the mischief he caused in politics, Gloucester is also at times praised as a patron of learning and a benefactor to the University of Oxford. He was popular among the literary figures of his age for his scholarly activity and with the common people for his advocacy of a spirited foreign policy. For these causes, he was known as the "good Duke Humphrey".

Gloucester never fully achieved his desired dominance in England, and his attempts to gain a foreign principality for himself were fruitless. A staunch opponent of concessions in the French conflict and a proponent of offensive warfare, Gloucester gradually lost favour among the political community, and King Henry VI after the end of his minority, following defeats in France. The trial in 1441 of Eleanor Cobham

Eleanor Cobham (c.1400 – 7 July 1452) was an English noblewoman, first the mistress and then the second wife of Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester. In 1441 she was forcibly divorced and sentenced to life imprisonment for treasonable necromancy, a p ...

, his second wife, under charges of witchcraft

Witchcraft is the use of Magic (supernatural), magic by a person called a witch. Traditionally, "witchcraft" means the use of magic to inflict supernatural harm or misfortune on others, and this remains the most common and widespread meanin ...

, destroyed Gloucester's political influence. In 1447, he was accused, probably falsely, of treason and died a few days later while under arrest.

Childhood and early career

The place of Humphrey's birth is unknown, but he was named after his maternal grandfather,Humphrey de Bohun, 7th Earl of Hereford

Humphrey de Bohun, 7th Earl of Hereford, 6th Earl of Essex, 2nd Earl of Northampton, Order of the Garter, KG (25 March 1342 – 16 January 1373) was the son of William de Bohun, 1st Earl of Northampton, and Elizabeth de Badlesmere, and grandson o ...

. He was the youngest in a powerful quadrumvirate of brothers, who were very close companions; on 20 March 1413, Henry and Humphrey had been at their dying father's bedside. Thomas

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas the A ...

, John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second E ...

and Humphrey had all been knighted

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of a knighthood by a head of state (including the pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church, or the country, especially in a military capacity.

The concept of a knighthood ...

in 1399. They joined the Order of the Garter

The Most Noble Order of the Garter is an order of chivalry founded by Edward III of England in 1348. The most senior order of knighthood in the Orders, decorations, and medals of the United Kingdom, British honours system, it is outranked in ...

together in 1400.

During the reign of Henry IV, Humphrey received a scholar's education, possibly at Balliol College, Oxford

Balliol College () is a constituent college of the University of Oxford. Founded in 1263 by nobleman John I de Balliol, it has a claim to be the oldest college in Oxford and the English-speaking world.

With a governing body of a master and aro ...

, while his elder brothers fought on the Welsh and Scottish borders. Following his father's death he was created Duke of Gloucester

Duke of Gloucester ( ) is a British royal title (after Gloucester), often conferred on one of the sons of the reigning monarch. The first four creations were in the Peerage of England and the last in the Peerage of the United Kingdom; the curre ...

in 1414, and Chamberlain of England, and he took his seat in Parliament. He became a member of the Privy Council in 1415.

Diplomatic and military career

He joined Henry V's campaigns in France. Before embarking, the army camped at Southampton, where the

He joined Henry V's campaigns in France. Before embarking, the army camped at Southampton, where the Earl of Cambridge

The title of Earl of Cambridge was created several times in the Peerage of England, and since 1362 the title has been closely associated with the Royal family (see also Duke of Cambridge, Marquess of Cambridge).

The first Earl of the fourth cre ...

failed in the Southampton Plot

The Southampton Plot was a conspiracy to depose King Henry V of England, revealed in 1415 just as the king was about to sail on campaign to France as part of the Hundred Years' War. The plan was to replace him with Edmund Mortimer, 5th Earl of ...

an assassination plot against the king. Humphrey and his brother, the Duke of Clarence, led an Inquiry of Lords to try Cambridge and Scrope Scrope (pronounced "scroop") is the name of an old English family of Norman origin that first came into prominence in the 14th century. The family has held the noble titles of Baron Scrope of Masham, Baron Scrope of Bolton, and for a brief time, t ...

for high treason on 5 August.

During the campaign, Humphrey gained a reputation as a commander. His knowledge of siege warfare, gained from his classical studies, contributed to the fall of Honfleur

Honfleur () is a commune in the Calvados department in northwestern France. It is located on the southern bank of the estuary of the Seine across from Le Havre and very close to the exit of the Pont de Normandie. The people that inhabit Hon ...

. During the Battle of Agincourt

The Battle of Agincourt ( ; ) was an English victory in the Hundred Years' War. It took place on 25 October 1415 (Saint Crispin's Day) near Azincourt, in northern France. The unexpected victory of the vastly outnumbered English troops agains ...

Humphrey was wounded; as he fell, the king sheltered him and withstood a determined assault from French knights. For his services, Humphrey was granted offices including Constable of Dover

Dover ( ) is a town and major ferry port in Kent, southeast England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies southeast of Canterbury and east of Maidstone. ...

, Warden of the Cinque Ports

Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports is the name of a ceremonial post in the United Kingdom. The post dates from at least the 12th century, when the title was Keeper of the Coast, but it may be older. The Lord Warden was originally in charge of the ...

on 27 November and King's Lieutenant. His tenure in government was peaceful and successful. This period commenced with Emperor Sigismund Sigismund (variants: Sigmund, Siegmund) is a German proper name, meaning "protection through victory", from Old High German ''sigu'' "victory" + ''munt'' "hand, protection". Tacitus latinises it ''Segimundus''. There appears to be an older form of ...

's peace mission, the only visit of a medieval emperor to England. According to ''Holinshed's Chronicles

''Holinshed's Chronicles'', also known as ''Holinshed's Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland'', is a collaborative work published in several volumes and two editions, the first edition in 1577, and the second in 1587. It was a large, co ...

'', Humphrey was the principal actor in a symbolic ceremony. He welcomed the emperor on the shoreline with a sword in his hand, "extorting" from Sigismund the renunciation of his prerogatives of dominion over the king of England before allowing him to land on the evening of 1 May 1416. The Treaty of "eternal friendship" signed at Canterbury on 15 August served only to anticipate renewed hostility from France.

Upon the death of his brother in 1422, Humphrey became Lord Protector

Lord Protector (plural: ''Lords Protector'') is a title that has been used in British constitutional law for the head of state. It was also a particular title for the British heads of state in respect to the established church. It was sometime ...

to his young nephew Henry VI, then a baby. He also claimed the right to the regency of England following the death of his elder brother, John, Duke of Bedford

John of Lancaster, Duke of Bedford (20 June 1389 – 14 September 1435) was a medieval English prince, general, and statesman who commanded England's armies in France during a critical phase of the Hundred Years' War. Bedford was the third son ...

, in 1435. Humphrey's claims were strongly contested by the lords of the king's council and in particular his half-uncle, Cardinal Henry Beaufort

Henry Beaufort (c. 1375 – 11 April 1447) was an English Catholic prelate and statesman who held the offices of Bishop of Lincoln (1398), Bishop of Winchester (1404) and cardinal (1426). He served three times as Lord Chancellor and played an ...

. Henry V's will, rediscovered at Eton College

Eton College ( ) is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school providing boarding school, boarding education for boys aged 13–18, in the small town of Eton, Berkshire, Eton, in Berkshire, in the United Kingdom. It has educated Prime Mini ...

in 1978, actually supported Humphrey's claims. In 1436 Philip

Philip, also Phillip, is a male name derived from the Macedonian Old Koine language, Greek (''Philippos'', lit. "horse-loving" or "fond of horses"), from a compound of (''philos'', "dear", "loved", "loving") and (''hippos'', "horse"). Prominen ...

, Duke of Burgundy

Duke of Burgundy () was a title used by the rulers of the Duchy of Burgundy, from its establishment in 843 to its annexation by the Crown lands of France, French crown in 1477, and later by members of the House of Habsburg, including Holy Roman E ...

, attacked Calais. Duke Humphrey was appointed garrison commander. The Flemings assaulted from the landward but the English resistance was stubborn. Humphrey marched the army to Baillieul, taking the English to safety; he threatened St. Omer before sailing home.

Humphrey was consistently popular with the citizens of London and the Commons. He also had a widespread reputation as a patron of learning and the arts. His popularity with the people and his ability to keep the peace earned him the appointment of Chief Justice of South Wales. His unpopular marriage to Eleanor Cobham

Eleanor Cobham (c.1400 – 7 July 1452) was an English noblewoman, first the mistress and then the second wife of Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester. In 1441 she was forcibly divorced and sentenced to life imprisonment for treasonable necromancy, a p ...

became ammunition for his enemies. Eleanor was arrested and tried for sorcery and heresy in 1441 and Humphrey retired from public life. He was arrested on a charge of treason on 20 February 1447 and died at Bury St Edmunds

Bury St Edmunds (), commonly referred to locally as ''Bury,'' is a cathedral as well as market town and civil parish in the West Suffolk District, West Suffolk district, in the county of Suffolk, England.OS Explorer map 211: Bury St. Edmunds an ...

in Suffolk

Suffolk ( ) is a ceremonial county in the East of England and East Anglia. It is bordered by Norfolk to the north, the North Sea to the east, Essex to the south, and Cambridgeshire to the west. Ipswich is the largest settlement and the county ...

three days later. He was buried at St Albans Abbey

St Albans Cathedral, officially the Cathedral and Abbey Church of St Alban, also known as "the Abbey", is a Church of England cathedral in St Albans, England.

Much of its architecture dates from Norman times. It ceased to be an abbey follo ...

, adjacent to St Alban's shrine. Some suspected that he had been poisoned, though it is more probable that he died of a stroke.

In each subsequent year, a petition was made to Parliament to rehabilitate 'Good Duke Humphrey', and by the end of the century his reputation had been restored.

Marriages

He married twice but left no surviving legitimate progeny.First marriage: Jacqueline, Countess of Hainaut and Holland

In about 1423 he married Jacqueline, Countess of Hainaut and Holland (died 1436), daughter of William VI, Count of Hainaut. Through this marriage Gloucester assumed the title "Count of Holland

The counts of Holland ruled over the County of Holland in the Low Countries between the 10th and the 16th century.

The Frisian origins

While the Frisian kingdom had comprised most of the present day Netherlands, the later province of Friesland ...

, Zeeland and Hainault", and briefly fought to retain these titles when they were contested by Jacqueline's cousin Philip the Good

Philip III the Good (; ; 31 July 1396 – 15 June 1467) ruled as Duke of Burgundy from 1419 until his death in 1467. He was a member of a cadet line of the Valois dynasty, to which all 15th-century kings of France belonged. During his reign, ...

(see: War of Succession in Holland). They had a stillborn child in 1424. The marriage was annulled in 1428, and Jacqueline died (disinherited) in 1436.

Second marriage: Eleanor Cobham

In 1428 Humphrey married, secondly,Eleanor Cobham

Eleanor Cobham (c.1400 – 7 July 1452) was an English noblewoman, first the mistress and then the second wife of Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester. In 1441 she was forcibly divorced and sentenced to life imprisonment for treasonable necromancy, a p ...

, his mistress, who in 1441 was tried and convicted of practising witchcraft against the king in an attempt to retain power for her husband. She was condemned to public penance followed by exile and life imprisonment. The marriage was without progeny.

Children

By mistresses unknown Humphrey had two illegitimate children. Eleanor Cobham was possibly the mother of one or both, before their marriage. Due to their illegitimacy, they were unable to succeed to their father's titles. The illegitimate children were: * Arthur Plantagenet (died after 1447) * Antigone Plantagenet, who married firstly Henry Grey, 2nd Earl of Tankerville, Lord of Powys (–1450) and secondly John d'Amancier.Legacy

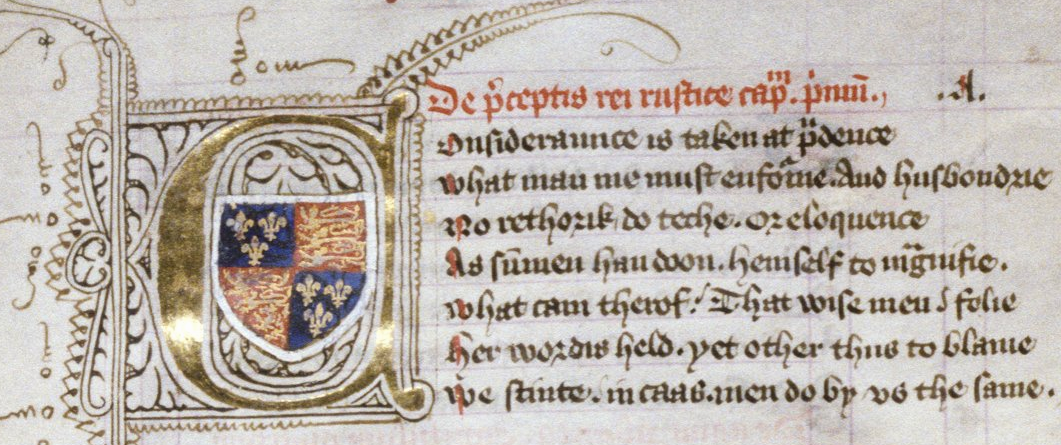

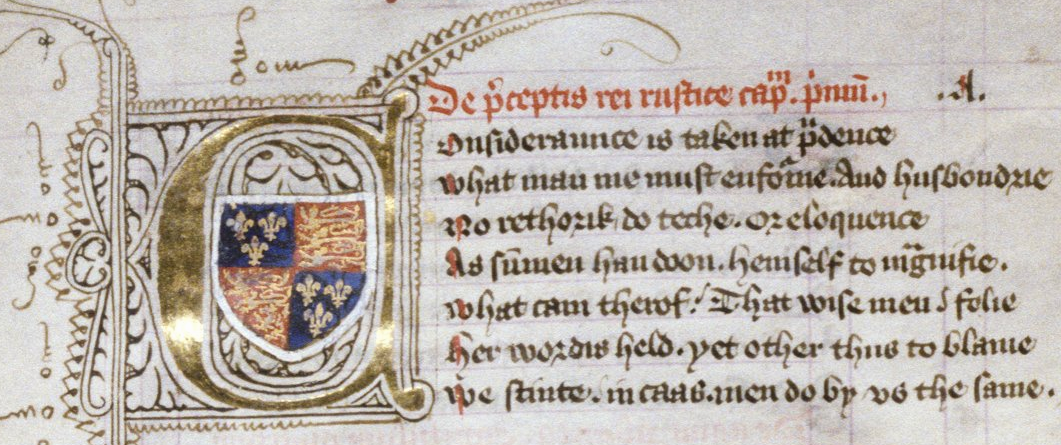

After inheriting the manor of

After inheriting the manor of Greenwich

Greenwich ( , , ) is an List of areas of London, area in south-east London, England, within the Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county of Greater London, east-south-east of Charing Cross.

Greenwich is notable for its maritime hi ...

, Gloucester enclosed Greenwich Park

Greenwich Park is a former hunting park in Greenwich and one of the largest single green spaces in south-east London. One of the eight Royal Parks of London, and the first to be enclosed (in 1433), it covers , and is part of the Greenwich World H ...

and from 1428 had a palace built there on the banks of the Thames, known as ''Bella Court'' and later as the Palace of Placentia

The Palace of Placentia, also known as Greenwich Palace,

was an English royal residence that was initially built by Prince Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, in 1443. Over the centuries it took several different forms, until it was turned into a ho ...

or La Pleasaunce. The Duke Humphrey Tower surmounting Greenwich Park was demolished in the 1660s and the site was chosen for building the Royal Observatory. His name lives on in Duke Humfrey's Library

Duke Humfrey's Library is the oldest Reference library, reading room in the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford. It is named after Humphrey of Lancaster, 1st Duke of Gloucester, who donated 281 books after his death in 1447. Sections ...

, part of the Bodleian Library

The Bodleian Library () is the main research library of the University of Oxford. Founded in 1602 by Sir Thomas Bodley, it is one of the oldest libraries in Europe. With over 13 million printed items, it is the second-largest library in ...

in Oxford University

The University of Oxford is a collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the second-oldest continuously operating u ...

, and in Duke Humphrey Road on Blackheath, south of Greenwich. Duke Humphrey was a patron and protector of Oxford, donating more than 280 manuscripts to the university. The possession of such a library did much to stimulate new learning.

Duke Humphrey was also a patron of literature, notably of the poet John Lydgate

John Lydgate of Bury () was an English monk and poet, born in Lidgate, near Haverhill, Suffolk, Haverhill, Suffolk, England.

Lydgate's poetic output is prodigious, amounting, at a conservative count, to about 145,000 lines. He explored and estab ...

and of John Capgrave. He corresponded with many leading Italian humanists and commissioned translations of Greek classics into Latin. His friendship with Zano Castiglione, Bishop of Bayeux, led to many further connections on the Continent, including Leonardo Bruni

Leonardo Bruni or Leonardo Aretino ( – March 9, 1444) was an Italian humanist, historian and statesman, often recognized as the most important humanist historian of the early Renaissance. He has been called the first modern historian. He was t ...

, Pietro Candido Decembrio and Tito Livio Frulovisi. Duke Humphrey also patronised the Abbey of St Albans.

Together with his second wife, Eleanor, he commissioned a hanap, a drinking goblet, possibly as their wedding cup. This hanap, known as the Wreathen Cup, was used when they hosted dinners at La Pleasance and their London residence, Baynard's Castle

Baynard's Castle refers to buildings on two neighbouring sites in the City of London, between where Blackfriars station and St. Paul's Cathedral now stand. The first was a Norman fortification constructed by Ralph Baynard ( 1086), 1st feuda ...

. It found its way into the possession of his kinswoman, Lady Margaret Beaufort

Lady Margaret Beaufort ( ; 31 May 1443 – 29 June 1509) was a major figure in the Wars of the Roses of the late 15th century, and mother of King Henry VII of England, the first House of Tudor, Tudor monarch. She was also a second cousin o ...

, who bequeathed it to her confessor, Dr Edmund Wilford, of Oriel College, Oxford

Oriel College () is Colleges of the University of Oxford, a constituent college of the University of Oxford in Oxford, England. Located in Oriel Square, the college has the distinction of being the oldest royal foundation in Oxford (a title for ...

. He exchanged it for another piece of silver left by Lady Margaret to her foundation at Christ's College, Cambridge

Christ's College is a Colleges of the University of Cambridge, constituent college of the University of Cambridge, England. The college includes the Master, the Fellows of the College, and about 450 undergraduate and 250 graduate students. The c ...

, where it remains. How it reached Lady Margaret is unclear, but a fellow of the college has conjectured that it came through her husband, Thomas Stanley, who had custody of Eleanor during her imprisonment and was involved in liquidating Humphrey's estate.

Duke Humphrey's Walk was the name of an aisle in Old St Paul's Cathedral

Old St Paul's Cathedral was the cathedral of the City of London that, until the Great Fire of London, Great Fire of 1666, stood on the site of the present St Paul's Cathedral. Built from 1087 to 1314 and dedicated to Paul of Tarsus, Saint Paul ...

near to what was popularly believed to be Duke Humphrey's tomb, though, according to W. Carew Hazlitt, it was, in reality, a monument to John Lord Beauchamp de Warwick (died 1360). This was an area frequented by thieves and beggars. The phrase "to dine with Duke Humphrey" was used of poor people who had no money for a meal, in reference to this. Saki

Hector Hugh Munro (18 December 1870 – 14 November 1916), popularly known by his pen name Saki and also frequently as H. H. Munro, was a British writer whose witty, mischievous and sometimes macabre stories satirise Edwardian society and ...

updates the phrase by referring to a "Duke Humphrey picnic", one without food, in his short story "The Feast of Nemesis". In fact, Humphrey's tomb is in the Abbey of St Albans (the cathedral): it was restored by Hertfordshire Freemasons

Freemasonry (sometimes spelled Free-Masonry) consists of fraternal groups that trace their origins to the medieval guilds of stonemasons. Freemasonry is the oldest secular fraternity in the world and among the oldest still-existing organizati ...

in 2000 to celebrate the millennium.

In literature

In

In Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

's History plays, the portrayal of Humphrey is notable for being one of the most unambiguously sympathetic: in the War of the Roses Tetralogy

A tetralogy (from Greek τετρα- ''tetra-'', "four" and -λογία ''-logia'', "discourse") is a compound work that is made up of four distinct works. The name comes from the Attic theater, in which a tetralogy was a group of three tragedies ...

, he is one of only a handful of historical personages to be portrayed in a uniformly positive light. He appears as a minor character in ''Henry IV, Part 2

''Henry IV, Part 2'' is a history play by William Shakespeare believed to have been written between 1596 and 1599. It is the third part of a tetralogy, preceded by '' Richard II'' and ''Henry IV, Part 1'' and succeeded by '' Henry V''.

The p ...

'' and ''Henry V Henry V may refer to:

People

* Henry V, Duke of Bavaria (died 1026)

* Henry V, Holy Roman Emperor (1081/86–1125)

* Henry V, Duke of Carinthia (died 1161)

* Henry V, Count Palatine of the Rhine (–1227)

* Henry V, Count of Luxembourg (1216–1281 ...

'', but as a major character in two others: his conflict with Cardinal Beaufort is portrayed in ''Henry VI, Part 1

''Henry VI, Part 1'', often referred to as ''1 Henry VI'', is a Shakespearean history, history play by William Shakespeare—possibly in collaboration with Thomas Nashe and others—believed to have been written in 1591. It is set during the ...

'', and his disgrace and death following his wife's alleged sorcery is depicted in ''Henry VI, Part 2

''Henry VI, Part 2'' (1591) is a Shakespearean history play about King Henry VI of England's inability to quell the bickering of his noblemen, the death of his trusted advisor Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, and the political rise of Richard of ...

''. Shakespeare portrays Humphrey's death as a murder, ordered by William de la Pole, 1st Duke of Suffolk

William de la Pole, 1st Duke of Suffolk (16 October 1396 – 2 May 1450), nicknamed Jackanapes, was an English magnate, statesman and military commander during the Hundred Years' War. He became a favourite of Henry VI of England, and consequent ...

, and Queen Margaret of Anjou

Margaret of Anjou (; 23 March 1430 – 25 August 1482) was Queen of England by marriage to King Henry VI from 1445 to 1461 and again from 1470 to 1471. Through marriage, she was also nominally Queen of France from 1445 to 1453. Born in the ...

.

The 1723 play ''Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester

Humphrey of Lancaster, Duke of Gloucester (3 October 1390 – 23 February 1447) was an English prince, soldier and literary patron. He was (as he styled himself) "son, brother and uncle of kings", being the fourth and youngest son of Henry IV ...

'' by Ambrose Philips

Ambrose Philips (167418 June 1749) was an England, English poet and politician. He feuded with other poets of his time, resulting in Henry Carey (writer), Henry Carey bestowing the nickname "Namby-Pamby" upon him, which came to mean affected, wea ...

revolves around the life of Gloucester. In the original Drury Lane

Drury Lane is a street on the boundary between the Covent Garden and Holborn areas of London, running between Aldwych and High Holborn. The northern part is in the borough of London Borough of Camden, Camden and the southern part in the City o ...

production he was played by Barton Booth

Barton Booth (168210 May 1733) was one of the most famous British dramatic actors of the first part of the 18th century.

Early life

Booth was the son of The Hon and Very Revd Dr Robert Booth, Dean of Bristol, by his first wife and distant co ...

.

Margaret Frazer's 2003 historical mystery, '' The Bastard's Tale'', revolves around the events surrounding Gloucester's arrest and death.

Titles, honours and arms

* Duke of Gloucester; created in 1414 (second creation). *Earl of Pembroke

Earl of Pembroke is a title in the Peerage of England that was first created in the 12th century by King Stephen of England. The title, which is associated with Pembroke, Pembrokeshire in West Wales, has been recreated ten times from its origin ...

; created in 1414 (fifth creation). The title was subsequently made hereditary, but defaulted to William de la Pole.

* Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports

Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports is the name of a ceremonial post in the United Kingdom. The post dates from at least the 12th century, when the title was Keeper of the Coast, but it may be older. The Lord Warden was originally in charge of the ...

, 1415.

Ancestry

References

Further reading

* * Hollman, Gemma (2019). ''Royal Witches: From Joan of Navarre to Elizabeth Woodville''. Cheltenham: The History Press. * * * * * , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester 1390 births 1447 deaths 15th-century English politicians 15th-century regents Peers created by Henry V Burials at St Albans Cathedral Dukes of Gloucester Earls of Pembroke Governors of Jersey Heirs presumptive to the English throne House of Lancaster Knights Bachelor Knights of the Garter Lords Protector of England Lords Warden of the Cinque Ports British patrons of literature Regents of England Sons of kings Children of Henry IV of England Members of the Privy Council of England Medieval governors of Guernsey English princes