Horses in warfare on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The first evidence of horses in warfare dates from

The first evidence of horses in warfare dates from

Horses were not the only

Horses were not the only

The invention of the wheel was a major technological innovation that gave rise to

The invention of the wheel was a major technological innovation that gave rise to

Two major innovations that revolutionised the effectiveness of mounted warriors in battle were the saddle and the stirrup.Bennett and others, ''Fighting Techniques'', pp. 70, 84. Riders quickly learned to pad their horse's backs to protect themselves from the horse's spine and

Two major innovations that revolutionised the effectiveness of mounted warriors in battle were the saddle and the stirrup.Bennett and others, ''Fighting Techniques'', pp. 70, 84. Riders quickly learned to pad their horse's backs to protect themselves from the horse's spine and

The first

The first

Among the earliest evidence of chariot use are the burials of horse and chariot remains by the Andronovo (Sintashta-Petrovka) culture in modern Russia and

Among the earliest evidence of chariot use are the burials of horse and chariot remains by the Andronovo (Sintashta-Petrovka) culture in modern Russia and

Some of the earliest examples of horses being ridden in warfare were horse-mounted archers or javelin-throwers, dating to the reigns of the

Some of the earliest examples of horses being ridden in warfare were horse-mounted archers or javelin-throwers, dating to the reigns of the

Once gunpowder was invented, another major use of horses was as draught animals for

Once gunpowder was invented, another major use of horses was as draught animals for

Relations between

Relations between

In technological innovation, the early toe loop stirrup is credited to the cultures of India, and may have been in use as early as 500 BC. Not long after, the cultures of

In technological innovation, the early toe loop stirrup is credited to the cultures of India, and may have been in use as early as 500 BC. Not long after, the cultures of

The Chinese used

The Chinese used

During the period when various

During the period when various

During the European

During the European

The war horse was also seen in

The war horse was also seen in

Light cavalry continued to play a major role, particularly after the

Light cavalry continued to play a major role, particularly after the

In the 19th century distinctions between heavy and light cavalry became less significant; by the end of the

In the 19th century distinctions between heavy and light cavalry became less significant; by the end of the

Horses were used for warfare in the central Sudan since the 9th century, where they were considered "the most precious commodity following the slave." The first conclusive evidence of horses playing a major role in the warfare of

Horses were used for warfare in the central Sudan since the 9th century, where they were considered "the most precious commodity following the slave." The first conclusive evidence of horses playing a major role in the warfare of

The first evidence of horses in warfare dates from

The first evidence of horses in warfare dates from Eurasia

Eurasia (, ) is the largest continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. Primarily in the Northern and Eastern Hemispheres, it spans from the British Isles and the Iberian Peninsula in the west to the Japanese archipelag ...

between 4000 and 3000 BC. A Sumerian illustration of warfare from 2500 BC depicts some type of equine

Equinae is a subfamily of the family Equidae, which have lived worldwide (except Indonesia and Australia) from the Hemingfordian stage of the Early Miocene (16 million years ago) onwards. They are thought to be a monophyletic grouping.B. J. Mac ...

pulling wagons. By 1600 BC, improved harness

A harness is a looped restraint or support. Specifically, it may refer to one of the following harness types:

* Bondage harness

* Child harness

* Climbing harness

* Dog harness

* Pet harness

* Five-point harness

* Horse harness

* Parrot harness

* ...

and chariot

A chariot is a type of cart driven by a charioteer, usually using horses to provide rapid motive power. The oldest known chariots have been found in burials of the Sintashta culture in modern-day Chelyabinsk Oblast, Russia, dated to c. 2000&nb ...

designs made chariot warfare common throughout the Ancient Near East

The ancient Near East was the home of early civilizations within a region roughly corresponding to the modern Middle East: Mesopotamia (modern Iraq, southeast Turkey, southwest Iran and northeastern Syria), ancient Egypt, ancient Iran (Ela ...

, and the earliest written training manual for war horses was a guide for training chariot horses written about 1350 BC. As formal cavalry tactics

For much of history, humans have used some form of cavalry for war and, as a result, cavalry tactics have evolved over time. Tactically, the main advantages of cavalry over infantry troops were greater mobility, a larger impact, and a higher po ...

replaced the chariot, so did new training methods, and by 360 BC, the Greek cavalry officer Xenophon

Xenophon of Athens (; grc, Ξενοφῶν ; – probably 355 or 354 BC) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian, born in Athens. At the age of 30, Xenophon was elected commander of one of the biggest Greek mercenary armies of ...

had written an extensive treatise on horsemanship. The effectiveness of horses in battle was also revolutionized by improvements in technology

Technology is the application of knowledge to reach practical goals in a specifiable and reproducible way. The word ''technology'' may also mean the product of such an endeavor. The use of technology is widely prevalent in medicine, scie ...

, such as the invention of the saddle

The saddle is a supportive structure for a rider of an animal, fastened to an animal's back by a girth. The most common type is equestrian. However, specialized saddles have been created for oxen, camels and other animals. It is not kno ...

, the stirrup

A stirrup is a light frame or ring that holds the foot of a rider, attached to the saddle by a strap, often called a ''stirrup leather''. Stirrups are usually paired and are used to aid in mounting and as a support while using a riding animal ...

, and the horse collar

A horse collar is a part of a horse harness that is used to distribute the load around a horse's neck and shoulders when pulling a wagon or plough. The collar often supports and pads a pair of curved metal or wooden pieces, called hames, to wh ...

.

Many different types and sizes of horse were used in war, depending on the form of warfare. The type used varied with whether the horse was being ridden or driven, and whether they were being used for reconnaissance

In military operations, reconnaissance or scouting is the exploration of an area by military forces to obtain information about enemy forces, terrain, and other activities.

Examples of reconnaissance include patrolling by troops ( skirmishe ...

, cavalry charges, raiding, communication, or supply. Throughout history, mules and donkeys as well as horses played a crucial role in providing support to armies in the field.

Horses were well suited to the warfare tactics of the nomad

A nomad is a member of a community without fixed habitation who regularly moves to and from the same areas. Such groups include hunter-gatherers, pastoral nomads (owning livestock), tinkers and trader nomads. In the twentieth century, the po ...

ic cultures from the steppe

In physical geography, a steppe () is an ecoregion characterized by grassland plains without trees apart from those near rivers and lakes.

Steppe biomes may include:

* the montane grasslands and shrublands biome

* the temperate grasslan ...

s of Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes the former ...

. Several cultures in East Asia

East Asia is the eastern region of Asia, which is defined in both geographical and ethno-cultural terms. The modern states of East Asia include China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan. China, North Korea, South Korea ...

made extensive use of cavalry and chariots. Muslim warriors relied upon light cavalry

Light cavalry comprised lightly armed and armored cavalry troops mounted on fast horses, as opposed to heavy cavalry, where the mounted riders (and sometimes the warhorses) were heavily armored. The purpose of light cavalry was primarily ...

in their campaigns throughout Northern Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

, Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an ...

, and Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located enti ...

beginning in the 7th and 8th centuries AD. Europeans used several types of war horses in the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

, and the best-known heavy cavalry

Heavy cavalry was a class of cavalry intended to deliver a battlefield charge and also to act as a tactical reserve; they are also often termed '' shock cavalry''. Although their equipment differed greatly depending on the region and histori ...

warrior of the period was the armoured knight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the G ...

. With the decline of the knight and rise of gunpowder in warfare, light cavalry again rose to prominence, used in both European warfare and in the conquest of the Americas. Battle cavalry developed to take on a multitude of roles in the late 18th century and early 19th century and was often crucial for victory in the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

. In the Americas, the use of horses and development of mounted warfare tactics were learned by several tribes of indigenous people

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

and in turn, highly mobile horse regiments were critical in the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by state ...

.

Horse cavalry began to be phased out after World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

in favour of tank warfare, though a few horse cavalry units were still used into World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, especially as scouts. By the end of World War II, horses were seldom seen in battle, but were still used extensively for the transport of troops and supplies. Today, formal battle-ready horse cavalry units have almost disappeared, though the United States Army Special Forces

The United States Army Special Forces (SF), colloquially known as the "Green Berets" due to their distinctive service headgear, are a special operations force of the United States Army.

The Green Berets are geared towards nine doctrinal mis ...

used horses in battle during the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan

In late 2001, the United States and its close allies invaded Afghanistan and toppled the Taliban government. The invasion's aims were to dismantle al-Qaeda, which had executed the September 11 attacks, and to deny it a safe base of operations ...

. Horses are still seen in use by organized armed fighters in developing countries

A developing country is a sovereign state with a lesser developed Industrial sector, industrial base and a lower Human Development Index (HDI) relative to other countries. However, this definition is not universally agreed upon. There is al ...

. Many nations still maintain small units of mounted riders for patrol and reconnaissance

In military operations, reconnaissance or scouting is the exploration of an area by military forces to obtain information about enemy forces, terrain, and other activities.

Examples of reconnaissance include patrolling by troops ( skirmishe ...

, and military horse units are also used for ceremonial and educational purposes. Horses are also used for historical reenactment

Historical reenactment (or re-enactment) is an educational entertainment, educational or entertainment activity in which mainly amateur hobbyists and history enthusiasts dress in historic uniforms or costumes and follow a plan to recreate aspect ...

of battles, law enforcement

Law enforcement is the activity of some members of government who act in an organized manner to enforce the law by discovering, deterring, rehabilitating, or punishing people who violate the rules and norms governing that society. The term ...

, and in equestrian

The word equestrian is a reference to equestrianism, or horseback riding, derived from Latin ' and ', "horse".

Horseback riding (or Riding in British English)

Examples of this are:

*Equestrian sports

*Equestrian order, one of the upper classes in ...

competitions derived from the riding and training skills once used by the military.

Types of horse used in warfare

A fundamental principle ofequine conformation

Equine conformation evaluates a horse's bone structure, musculature, and its body proportions in relation to each other. Undesirable conformation can limit the ability to perform a specific task. Although there are several faults with universa ...

is "form to function". Therefore, the type of horse used for various forms of warfare depended on the work performed, the weight a horse needed to carry or pull, and distance travelled. Weight affects speed and endurance, creating a trade-off: armour added protection, but added weight reduces maximum speed. Therefore, various cultures had different military needs. In some situations, one primary type of horse was favoured over all others. In other places, multiple types were needed; warriors would travel to battle riding a lighter horse of greater speed and endurance, and then switch to a heavier horse, with greater weight-carrying capacity, when wearing heavy armour in actual combat.Nicolle, ''Crusader Knight'', p. 14.

The average horse can carry up to approximately 30% of its body weight. While all horses can pull more weight than they can carry, the maximum weight that horses can pull varies widely, depending on the build of the horse, the type of vehicle, road conditions, and other factors. Horses harnessed to a wheeled vehicle on a paved road can pull as much as eight times their weight, but far less if pulling wheelless loads over unpaved terrain. Thus, horses that were driven varied in size and had to make a trade-off between speed and weight, just as did riding animals. Light horses could pull a small war chariot at speed. Heavy supply wagons, artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during sieg ...

, and support vehicles were pulled by heavier horses or a larger number of horses.Chamberlin, ''Horse'', p. 146. The method by which a horse was hitched to a vehicle also mattered: horses could pull greater weight with a horse collar

A horse collar is a part of a horse harness that is used to distribute the load around a horse's neck and shoulders when pulling a wagon or plough. The collar often supports and pads a pair of curved metal or wooden pieces, called hames, to wh ...

than they could with a breast collar, and even less with an ox yoke

A yoke is a wooden beam sometimes used between a pair of oxen or other animals to enable them to pull together on a load when working in pairs, as oxen usually do; some yokes are fitted to individual animals. There are several types of yoke, u ...

.Chamberlin, ''Horse'', pp. 106–110.

Light-weight

Light,oriental horse

The term oriental horse refers to the ancient breeds of horses developed in the Middle East, such as the Arabian, Akhal-Teke, Barb, and the now-extinct Turkoman horse. They tend to be thin-skinned, long-legged, slim in build and more physicall ...

s such as the ancestors of the modern Arabian

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plate. ...

, Barb

Barb or the BARBs or ''variation'' may refer to:

People

* Barb (name), a list of people and fictional characters with the given name or surname

* Barb, a term used by fans of Nicki Minaj to refer to themselves

* The Barbs, a band

Places

* Barb, ...

, and Akhal-Teke

The Akhal-Teke ( or ; from Turkmen ''Ahalteke'', ) is a Turkmen horse breed. They have a reputation for speed and endurance, intelligence, and a distinctive metallic sheen. The shiny coat of the breed led to their nickname, "Golden Horses". ...

were used for warfare that required speed, endurance and agility. Such horses ranged from about to just under , weighing approximately . To move quickly, riders had to use lightweight tack and carry relatively light weapons such as bows, light spears, javelins, or, later, rifles. This was the original horse used for early chariot warfare, raiding, and light cavalry.

Relatively light horses were used by many cultures, including the Ancient Egyptians, the Mongols

The Mongols ( mn, Монголчууд, , , ; ; russian: Монголы) are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, Inner Mongolia in China and the Buryatia Republic of the Russian Federation. The Mongols are the principal member ...

, the Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Wester ...

s, and the Native Americans. Throughout the Ancient Near East

The ancient Near East was the home of early civilizations within a region roughly corresponding to the modern Middle East: Mesopotamia (modern Iraq, southeast Turkey, southwest Iran and northeastern Syria), ancient Egypt, ancient Iran (Ela ...

, small, light animals were used to pull chariots designed to carry no more than two passengers, a driver and a warrior.Bennett ''Conquerors'' p. 29 In the European Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

, a lightweight war horse became known as the rouncey.

Medium-weight

Medium-weight horses developed as early as theIron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age (Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age (Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly appl ...

with the needs of various civilizations to pull heavier loads, such as chariots capable of holding more than two people, and, as light cavalry

Light cavalry comprised lightly armed and armored cavalry troops mounted on fast horses, as opposed to heavy cavalry, where the mounted riders (and sometimes the warhorses) were heavily armored. The purpose of light cavalry was primarily ...

evolved into heavy cavalry

Heavy cavalry was a class of cavalry intended to deliver a battlefield charge and also to act as a tactical reserve; they are also often termed '' shock cavalry''. Although their equipment differed greatly depending on the region and histori ...

, to carry heavily armoured riders.Edwards, G., ''The Arabian'', pp. 11, 13. The Scythians

The Scythians or Scyths, and sometimes also referred to as the Classical Scythians and the Pontic Scythians, were an ancient Eastern

* : "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved for the ancient tribes of northern and eastern Cent ...

were among the earliest cultures to produce taller, heavier horses. Larger horses were also needed to pull supply wagons and, later on, artillery pieces. In Europe, horses were also used to a limited extent to maneuver cannons

A cannon is a large-caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder during ...

on the battlefield as part of dedicated horse artillery

Horse artillery was a type of light, fast-moving, and fast-firing artillery which provided highly mobile fire support, especially to cavalry units. Horse artillery units existed in armies in Europe, the Americas, and Asia, from the early 17th to ...

units. Medium-weight horses had the greatest range in size, from about but stocky, to as much as , weighing approximately . They generally were quite agile in combat, though they did not have the raw speed or endurance of a lighter horse. By the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

, larger horses in this class were sometimes called destrier

Mounted on a destrier, Richard Marshal unseats an opponent during a skirmish.

The destrier is the best-known war horse of the Middle Ages. It carried knights in battles, tournaments, and jousts. It was described by contemporary sources as th ...

s. They may have resembled modern Baroque or heavy warmblood

The heavy warmbloods (german: Schwere Warmblüter) are a group of horse breeds primarily from continental Europe. The title includes the Ostfriesen ("East Friesian") and Alt-Oldenburger ("Old-Oldenburger"), Groningen, and similar horses from Sil ...

breeds. Later, horses similar to the modern warmblood

Warmbloods are a group of middle-weight horse types and breeds primarily originating in Europe and registered with organizations that are characterized by open studbook policy, studbook selection, and the aim of breeding for equestrian spor ...

often carried European cavalry.

Heavy-weight

Large, heavy horses, weighing from , the ancestors of today'sdraught horses

A draft horse (US), draught horse (UK) or dray horse (from the Old English ''dragan'' meaning "to draw or haul"; compare Dutch ''dragen'' and German ''tragen'' meaning "to carry" and Danish ''drage'' meaning "to draw" or "to fare"), less ofte ...

, were used, particularly in Europe, from the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

onward. They pulled heavy loads like supply wagons and were disposed to remain calm in battle. Some historians believe they may have carried the heaviest-armoured knight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the G ...

s of the Late Medieval Period, though others dispute this claim, indicating that the destrier, or knight's battle horse, was a medium-weight animal. It is also disputed whether the destrier class included draught animals or not. Breeds at the smaller end of the heavyweight category may have included the ancestors of the Percheron

The Percheron is a breed of draft horse that originated in the Huisne river valley in western France, part of the former Perche province from which the breed takes its name. Usually gray or black in color, Percherons are well muscled, and ...

, agile for their size and physically able to manoeuvre in battle.

Ponies

The British Army's 2nd Dragoons in 1813 had 340 ponies of and 55 ponies of ; the Lovat Scouts, formed in 1899, were mounted on Highland ponies; the British Army recruited 200 Dales ponies in World War II for use as pack and artillery animals; and the British Territorial Army experimented with the use of Dartmoor ponies aspack animal

A pack animal, also known as a sumpter animal or beast of burden, is an individual or type of working animal used by humans as means of transporting materials by attaching them so their weight bears on the animal's back, in contrast to draft an ...

s in 1935, finding them to be better than mules for the job.

Other equids

Horses were not the only

Horses were not the only equids

Equidae (sometimes known as the horse family) is the taxonomic family of horses and related animals, including the extant horses, asses, and zebras, and many other species known only from fossils. All extant species are in the genus ''Equus'', ...

used to support human warfare. Donkeys

The domestic donkey is a hoofed mammal in the family Equidae, the same family as the horse. It derives from the African wild ass, ''Equus africanus'', and may be classified either as a subspecies thereof, ''Equus africanus asinus'', or as a ...

have been used as pack animals from antiquity to the present. Mules were also commonly used, especially as pack animals and to pull wagons, but also occasionally for riding. Because mules are often both calmer and hardier than horses,Equine Research ''Equine Genetics'' p. 190 they were particularly useful for strenuous support tasks, such as hauling supplies over difficult terrain. However, under gunfire, they were less cooperative than horses, so were generally not used to haul artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during sieg ...

on battlefields. The size of a mule and work to which it was put depended largely on the breeding of the mare

A mare is an adult female horse or other equine. In most cases, a mare is a female horse over the age of three, and a filly is a female horse three and younger. In Thoroughbred horse racing, a mare is defined as a female horse more than f ...

that produced the mule. Mules could be lightweight, medium weight, or even, when produced from draught horse mare

A mare is an adult female horse or other equine. In most cases, a mare is a female horse over the age of three, and a filly is a female horse three and younger. In Thoroughbred horse racing, a mare is defined as a female horse more than f ...

s, of moderate heavy weight.Ensminger, ''Horses and Horsemanship'', pp. 85–87.

Training and deployment

The oldest known manual on training horses for chariot warfare was written c. 1350 BC by the Hittite horsemaster,Kikkuli Kikkuli was the Hurrian "master horse trainer 'assussanni''of the land of Mitanni" (LÚ''A-AŠ-ŠU-UŠ-ŠA-AN-NI ŠA'' KUR URU''MI-IT-TA-AN-NI'') and author of a chariot horse training text written primarily in the Hittite language (as well as an ...

.Chamberlin ''Horse'' pp. 48–49 An ancient manual on the subject of training riding horses, particularly for the Ancient Greek cavalry is ''Hippike'' (''On Horsemanship

''On Horsemanship'' is the English title usually given to ', ''peri hippikēs'', one of the two treatises on horsemanship by the Athenian historian and soldier Xenophon (c. 430–354 BC). Other common titles for this work are ''De equis alendis' ...

'') written about 360 BC by the Greek cavalry officer Xenophon

Xenophon of Athens (; grc, Ξενοφῶν ; – probably 355 or 354 BC) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian, born in Athens. At the age of 30, Xenophon was elected commander of one of the biggest Greek mercenary armies of ...

.Hope, ''The Horseman's Manual'', ch. 1 and 2. and another early text was that of Kautilya

Chanakya (Sanskrit: चाणक्य; IAST: ', ; 375–283 BCE) was an ancient Indian polymath who was active as a teacher, author, strategist, philosopher, economist, jurist, and royal advisor. He is traditionally identified as Kauṭilya ...

, written about 323 BC.

Whether horses were trained to pull chariots, to be ridden as light or heavy cavalry, or to carry the armoured knight, much training was required to overcome the horse's natural instinct to flee from noise, the smell of blood, and the confusion of combat. They also learned to accept any sudden or unusual movements of humans while using a weapon or avoiding one.Hyland, ''The Medieval Warhorse'', pp. 115–117. Horses used in close combat may have been taught, or at least permitted, to kick, strike, and even bite, thus becoming weapons themselves for the warriors they carried.Gravett, ''Tudor Knight'', pp. 29–30.

In most cultures, a war horse used as a riding animal was trained to be controlled with limited use of rein

Reins are items of horse tack, used to direct a horse or other animal used for riding. They are long straps that can be made of leather, nylon, metal, or other materials, and attach to a bridle via either its bit or its noseband.

Use fo ...

s, responding primarily to the rider's legs and weight. The horse became accustomed to any necessary tack and protective armour placed upon it, and learned to balance under a rider who would also be laden with weapons and armour. Developing the balance and agility of the horse was crucial. The origins of the discipline of dressage came from the need to train horses to be both obedient and manoeuvrable. The ''Haute ecole'' or "High School" movements of classical dressage

Classical dressage evolved from cavalry movements and training for the battlefield, and has since developed into the competitive dressage seen today. Classical riding is the art of riding in harmony with, rather than against, the horse.

Correct ...

taught today at the Spanish Riding School

The Spanish Riding School (german: Spanische Hofreitschule) is an Austrian institution dedicated to the preservation of classical dressage and the training of Lipizzaner horses, based in Vienna, Austria, whose performances in the Hofburg are al ...

have their roots in manoeuvres designed for the battlefield. However, the ''airs above the ground

The airs above the ground or school jumps are a series of higher-level, Haute ecole, classical dressage movements in which the horse leaves the ground. They include the capriole, the courbette, the mezair, the croupade and the levade. None a ...

'' were unlikely to have been used in actual combat, as most would have exposed the unprotected underbelly of the horse to the weapons of foot soldiers.Chamberlin, ''Horse'', pp. 197–198.

Horses used for chariot warfare

A chariot is a type of cart driven by a charioteer, usually using horses to provide rapid motive power. The oldest known chariots have been found in burials of the Sintashta culture in modern-day Chelyabinsk Oblast, Russia, dated to c. 2000&nb ...

were not only trained for combat conditions, but because many chariots were pulled by a team of two to four horses, they also had to learn to work together with other animals in close quarters under chaotic conditions.Hyland, ''Equus'', pp. 214–218.

Technological innovations

Horses were probably ridden in prehistory before they were driven. However, evidence is scant, mostly simple images of human figures on horse-like animals drawn on rock or clay.Trench, ''A History of Horsemanship'', p. 16. The earliest tools used to control horses werebridle

A bridle is a piece of equipment used to direct a horse. As defined in the ''Oxford English Dictionary'', the "bridle" includes both the that holds a bit that goes in the mouth of a horse, and the reins that are attached to the bit.

Headgear ...

s of various sorts, which were invented nearly as soon as the horse was domesticated

Domestication is a sustained multi-generational relationship in which humans assume a significant degree of control over the reproduction and care of another group of organisms to secure a more predictable supply of resources from that group. A ...

. Evidence of bit

The bit is the most basic unit of information in computing and digital communications. The name is a portmanteau of binary digit. The bit represents a logical state with one of two possible values. These values are most commonly represented a ...

wear appears on the teeth of horses excavated at the archaeology sites of the Botai culture

The Botai culture is an archaeological culture (c. 3700–3100 BC) of prehistoric northern Central Asia. It was named after the settlement of Botai in today's northern Kazakhstan. The Botai culture has two other large sites: Krasnyi Y ...

in northern Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a transcontinental country located mainly in Central Asia and partly in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental coun ...

, dated 3500–3000 BC.

Harness and vehicles

The invention of the wheel was a major technological innovation that gave rise to

The invention of the wheel was a major technological innovation that gave rise to chariot

A chariot is a type of cart driven by a charioteer, usually using horses to provide rapid motive power. The oldest known chariots have been found in burials of the Sintashta culture in modern-day Chelyabinsk Oblast, Russia, dated to c. 2000&nb ...

warfare. At first, equines, both horses and onagers

The onager (; ''Equus hemionus'' ), A new species called the kiang (''E. kiang''), a Tibetan relative, was previously considered to be a subspecies of the onager as ''E. hemionus kiang'', but recent molecular studies indicate it to be a distinct ...

, were hitched to wheeled carts by means of a yoke

A yoke is a wooden beam sometimes used between a pair of oxen or other animals to enable them to pull together on a load when working in pairs, as oxen usually do; some yokes are fitted to individual animals. There are several types of yoke, u ...

around their necks in a manner similar to that of oxen

An ox ( : oxen, ), also known as a bullock (in BrE, AusE, and IndE), is a male bovine trained and used as a draft animal. Oxen are commonly castrated adult male cattle; castration inhibits testosterone and aggression, which makes the ma ...

.Pritchard, ''The Ancient Near East'', illustration 97. However, such a design is incompatible with equine anatomy

Equine anatomy encompasses the gross and microscopic anatomy of horses, ponies and other equids, including donkeys, mules and zebras. While all anatomical features of equids are described in the same terms as for other animals by the Internati ...

, limiting both the strength and mobility of the animal. By the time of the Hyksos

Hyksos (; Egyptian '' ḥqꜣ(w)- ḫꜣswt'', Egyptological pronunciation: ''hekau khasut'', "ruler(s) of foreign lands") is a term which, in modern Egyptology, designates the kings of the Fifteenth Dynasty of Egypt (fl. c. 1650–1550 BC). ...

invasions of Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Med ...

, c. 1600 BC, horses were pulling chariots with an improved harness

A harness is a looped restraint or support. Specifically, it may refer to one of the following harness types:

* Bondage harness

* Child harness

* Climbing harness

* Dog harness

* Pet harness

* Five-point harness

* Horse harness

* Parrot harness

* ...

design that made use of a breastcollar

A breastplate (used interchangeably with breastcollar, breaststrap and breastgirth) is a piece of riding equipment used on horses. Its purpose is to keep the saddle or harness from sliding back.

On riding horses, it is most helpful on horses wit ...

and breeching, which allowed a horse to move faster and pull more weight.Chamberlin, ''Horse'', pp. 102–108.

Even after the chariot had become obsolete as a tool of war, there still was a need for technological innovations in pulling technologies; horses were needed to pull heavy loads of supplies and weapons. The invention of the horse collar

A horse collar is a part of a horse harness that is used to distribute the load around a horse's neck and shoulders when pulling a wagon or plough. The collar often supports and pads a pair of curved metal or wooden pieces, called hames, to wh ...

in China during the 5th century AD (Northern and Southern dynasties

The Northern and Southern dynasties () was a period of political division in the history of China that lasted from 420 to 589, following the tumultuous era of the Sixteen Kingdoms and the Eastern Jin dynasty. It is sometimes considered a ...

) allowed horses to pull greater weight than they could when hitched to a vehicle with the ox yokes or breast collars used in earlier times.Needham, ''Science and Civilization in China'', p. 322. The horse collar arrived in Europe during the 9th century,Chamberlin, ''Horse'', pp. 109–110. and became widespread by the 12th century.Needham, ''Science and Civilization in China'', p. 317.

Riding equipment

withers

The withers is the ridge between the shoulder blades of an animal, typically a quadruped. In many species, it is the tallest point of the body. In horses and dogs, it is the standard place to measure the animal's height. In contrast, cattle ...

, and fought on horseback for centuries with little more than a blanket or pad on the horse's back and a rudimentary bridle. To help distribute the rider's weight and protect the horse's back, some cultures created stuffed padding that resembles the panels of today's English saddle

English saddles are used to ride horses in English riding disciplines throughout the world. The discipline is not limited to England, the United Kingdom in general or other English-speaking countries. This style of saddle is used in all of the O ...

.Bennett, ''Conquerors'' p. 43. Both the Scythians

The Scythians or Scyths, and sometimes also referred to as the Classical Scythians and the Pontic Scythians, were an ancient Eastern

* : "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved for the ancient tribes of northern and eastern Cent ...

and Assyria

Assyria (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , romanized: ''māt Aššur''; syc, ܐܬܘܪ, ʾāthor) was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization which existed as a city-state at times controlling regional territories in the indigenous lands of the As ...

ns used pads with added felt attached with a surcingle

A surcingle is a strap made of leather or leather-like synthetic materials such as nylon or neoprene, sometimes with elastic, that fastens around the horse's girth.

A surcingle may be used for ground training, some types of in-hand exhibition, ...

or girth around the horse's barrel

A barrel or cask is a hollow cylindrical container with a bulging center, longer than it is wide. They are traditionally made of wooden staves and bound by wooden or metal hoops. The word vat is often used for large containers for liquids, ...

for increased security and comfort. Xenophon mentioned the use of a padded cloth on cavalry mounts as early as the 4th century BC.

The saddle with a solid framework, or "tree

In botany, a tree is a perennial plant with an elongated stem, or trunk, usually supporting branches and leaves. In some usages, the definition of a tree may be narrower, including only woody plants with secondary growth, plants that are ...

", provided a bearing surface to protect the horse from the weight of the rider, but was not widespread until the 2nd century AD. However, it made a critical difference, as horses could carry more weight when distributed across a solid saddle tree. A solid tree, the predecessor of today's Western saddle

Western saddles are used for western riding and are the saddles used on working horses on cattle ranches throughout the United States, particularly in the west. They are the "cowboy" saddles familiar to movie viewers, rodeo fans, and those ...

, also allowed a more built-up seat to give the rider greater security in the saddle. The Romans

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

are credited with the invention of the solid-treed saddle.

An invention that made cavalry particularly effective was the stirrup. A toe loop that held the big toe was used in India possibly as early as 500 BC,Chamberlin, ''Horse'', pp. 110–114. and later a single stirrup was used as a mounting aid. The first set of paired stirrups appeared in China about 322 AD during the Jin dynasty.Ellis, ''Cavalry'', pp. 51–53. Following the invention of paired stirrups, which allowed a rider greater leverage with weapons, as well as both increased stability and mobility while mounted, nomadic groups such as the Mongols

The Mongols ( mn, Монголчууд, , , ; ; russian: Монголы) are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, Inner Mongolia in China and the Buryatia Republic of the Russian Federation. The Mongols are the principal member ...

adopted this technology and developed a decisive military advantage. By the 7th century, due primarily to invaders from Central Asia, stirrup technology spread from Asia to Europe.Bennett, ''Dictionary of Ancient & Medieval Warfare'', p. 300. The Avar invaders are viewed as primarily responsible for spreading the use of the stirrup into central Europe.Curta, '"The Other Europe,'' p. 319 However, while stirrups were known in Europe in the 8th century, pictorial and literary references to their use date only from the 9th century. Widespread use in Northern Europe, including England, is credited to the Viking

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and s ...

s, who spread the stirrup in the 9th and 10th centuries to those areas.Nicolle, ''Medieval Warfare Sourcebook: Warfare in Western Christendom'', pp. 88–89.

Tactics

The first

The first archaeological

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscape ...

evidence of horses used in warfare dates from between 4000 and 3000 BC in the steppe

In physical geography, a steppe () is an ecoregion characterized by grassland plains without trees apart from those near rivers and lakes.

Steppe biomes may include:

* the montane grasslands and shrublands biome

* the temperate grasslan ...

s of Eurasia

Eurasia (, ) is the largest continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. Primarily in the Northern and Eastern Hemispheres, it spans from the British Isles and the Iberian Peninsula in the west to the Japanese archipelag ...

, in what today is Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian invas ...

, Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croa ...

, and Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Moldova to the east, a ...

. Not long after domestication of the horse

A number of hypotheses exist on many of the key issues regarding the domestication of the horse. Although horses appeared in Paleolithic cave art as early as 30,000 BCE, these were wild horses and were probably hunted for meat.

How and when ho ...

, people in these locations began to live together in large fortified towns for protection from the threat of horseback-riding raiders, who could attack and escape faster than people of more sedentary cultures could follow.Keegan, ''A History of Warfare'', p. 188. Horse-mounted nomads of the steppe

In physical geography, a steppe () is an ecoregion characterized by grassland plains without trees apart from those near rivers and lakes.

Steppe biomes may include:

* the montane grasslands and shrublands biome

* the temperate grasslan ...

and current day Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, wh ...

spread Indo-European Languages

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family, English, French, Portuguese, Russian, ...

as they conquered other tribes and groups.

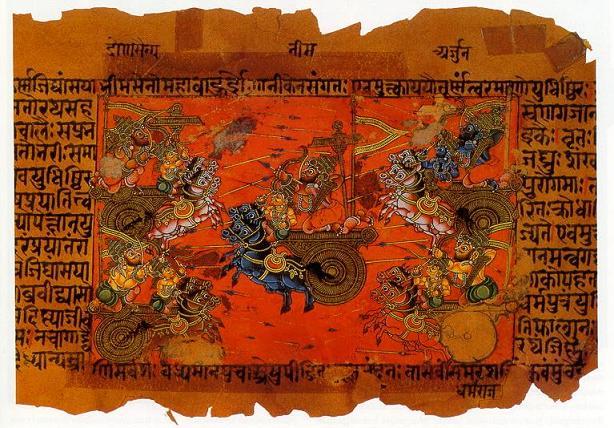

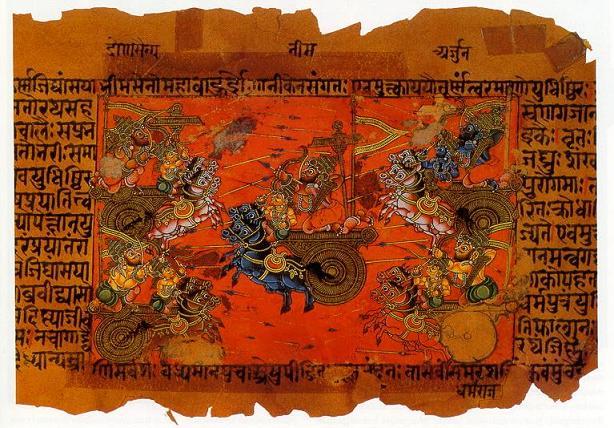

The use of horses in organised warfare was documented early in recorded history. One of the first depictions is the "war panel" of the Standard of Ur, in Sumer, dated c. 2500 BC, showing horses (or possibly onagers or mules) pulling a four-wheeled wagon.

Chariot warfare

Among the earliest evidence of chariot use are the burials of horse and chariot remains by the Andronovo (Sintashta-Petrovka) culture in modern Russia and

Among the earliest evidence of chariot use are the burials of horse and chariot remains by the Andronovo (Sintashta-Petrovka) culture in modern Russia and Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a transcontinental country located mainly in Central Asia and partly in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental coun ...

, dated to approximately 2000 BC. The oldest documentary evidence of what was probably chariot warfare in the Ancient Near East

The ancient Near East was the home of early civilizations within a region roughly corresponding to the modern Middle East: Mesopotamia (modern Iraq, southeast Turkey, southwest Iran and northeastern Syria), ancient Egypt, ancient Iran (Ela ...

is the Old Hittite Anitta text, of the 18th century BC, which mentioned 40 teams of horses at the siege of Salatiwara. The Hittites

The Hittites () were an Anatolian people who played an important role in establishing first a kingdom in Kussara (before 1750 BC), then the Kanesh or Nesha kingdom (c. 1750–1650 BC), and next an empire centered on Hattusa in north-cent ...

became well known throughout the ancient world for their prowess with the chariot. Widespread use of the chariot in warfare across most of Eurasia coincides approximately with the development of the composite bow

A composite bow is a traditional bow made from horn, wood, and sinew laminated together, a form of laminated bow. The horn is on the belly, facing the archer, and sinew on the outer side of a wooden core. When the bow is drawn, the sinew (s ...

, known from c. 1600 BC. Further improvements in wheels and axles, as well as innovations in weaponry, soon resulted in chariots being driven in battle by Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

societies from China to Egypt.

The Hyksos

Hyksos (; Egyptian '' ḥqꜣ(w)- ḫꜣswt'', Egyptological pronunciation: ''hekau khasut'', "ruler(s) of foreign lands") is a term which, in modern Egyptology, designates the kings of the Fifteenth Dynasty of Egypt (fl. c. 1650–1550 BC). ...

invaders brought the chariot to Ancient Egypt in the 16th century BC and the Egyptians adopted its use from that time forward. The oldest preserved text related to the handling of war horses in the ancient world is the Hittite manual of Kikkuli Kikkuli was the Hurrian "master horse trainer 'assussanni''of the land of Mitanni" (LÚ''A-AŠ-ŠU-UŠ-ŠA-AN-NI ŠA'' KUR URU''MI-IT-TA-AN-NI'') and author of a chariot horse training text written primarily in the Hittite language (as well as an ...

, which dates to about 1350 BC, and describes the conditioning of chariot horses.

Chariots existed in the Minoan civilization, as they were inventoried on storage lists from Knossos

Knossos (also Cnossos, both pronounced ; grc, Κνωσός, Knōsós, ; Linear B: ''Ko-no-so'') is the largest Bronze Age archaeological site on Crete and has been called Europe's oldest city.

Settled as early as the Neolithic period, the na ...

in Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cypru ...

,Adkins, ''Handbook to Life in Ancient Greece'', pp. 94–95. dating to around 1450 BC.Willetts, "Minoans" in ''Penguin Encyclopedia of Ancient Civilizations'' p. 209. Chariots were also used in China as far back as the Shang dynasty

The Shang dynasty (), also known as the Yin dynasty (), was a Dynasties in Chinese history, Chinese royal dynasty founded by Tang of Shang (Cheng Tang) that ruled in the Yellow River valley in the second millennium BC, traditionally suc ...

(c. 1600–1050 BC), where they appear in burials. The high point of chariot use in China was in the Spring and Autumn period

The Spring and Autumn period was a period in Chinese history from approximately 770 to 476 BC (or according to some authorities until 403 BC) which corresponds roughly to the first half of the Eastern Zhou period. The period's name derives fr ...

(770–476 BC), although they continued in use up until the 2nd century BC.Bennett, ''Dictionary of Ancient & Medieval Warfare'', p. 67.

Descriptions of the tactical role of chariots in Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cult ...

and Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

are rare. The Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; grc, Ἰλιάς, Iliás, ; "a poem about Ilium") is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the '' Odys ...

, possibly referring to Mycenae

Mycenae ( ; grc, Μυκῆναι or , ''Mykē̂nai'' or ''Mykḗnē'') is an archaeological site near Mykines in Argolis, north-eastern Peloponnese, Greece. It is located about south-west of Athens; north of Argos; and south of Corinth. ...

n practices used c. 1250 BC, describes the use of chariots for transporting warriors to and from battle, rather than for actual fighting. Later, Julius Caesar, invading Britain in 55 and 54 BC, noted British charioteers throwing javelins, then leaving their chariots to fight on foot.Warry, ''Warfare in the Classical World'', pp. 220–221.

Cavalry

Assyria

Assyria (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , romanized: ''māt Aššur''; syc, ܐܬܘܪ, ʾāthor) was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization which existed as a city-state at times controlling regional territories in the indigenous lands of the As ...

n rulers Ashurnasirpal II

Ashur-nasir-pal II ( transliteration: ''Aššur-nāṣir-apli'', meaning "Ashur is guardian of the heir") was king of Assyria from 883 to 859 BC.

Ashurnasirpal II succeeded his father, Tukulti-Ninurta II, in 883 BC. During his reign he embarke ...

and Shalmaneser III

Shalmaneser III (''Šulmānu-ašarēdu'', "the god Shulmanu is pre-eminent") was king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from the death of his father Ashurnasirpal II in 859 BC to his own death in 824 BC.

His long reign was a constant series of campaign ...

. However, these riders sat far back on their horses, a precarious position for moving quickly, and the horses were held by a handler on the ground, keeping the archer free to use the bow. Thus, these archers were more a type of mounted infantry

Mounted infantry were infantry

Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry & mechanized infantry, airborne infant ...

than true cavalry. The Assyrians developed cavalry in response to invasions by nomadic people from the north, such as the Cimmerians

The Cimmerians (Akkadian: , romanized: ; Hebrew: , romanized: ; Ancient Greek: , romanized: ; Latin: ) were an ancient Eastern Iranian equestrian nomadic people originating in the Caspian steppe, part of whom subsequently migrated into W ...

, who entered Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The ...

in the 8th century BC and took over parts of Urartu

Urartu (; Assyrian: ',Eberhard Schrader, ''The Cuneiform inscriptions and the Old Testament'' (1885), p. 65. Babylonian: ''Urashtu'', he, אֲרָרָט ''Ararat'') is a geographical region and Iron Age kingdom also known as the Kingdom of Va ...

during the reign of Sargon II

Sargon II (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , meaning "the faithful king" or "the legitimate king") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 722 BC to his death in battle in 705. Probably the son of Tiglath-Pileser III (745–727), Sargon is genera ...

, approximately 721 BC. Mounted warriors such as the Scythians

The Scythians or Scyths, and sometimes also referred to as the Classical Scythians and the Pontic Scythians, were an ancient Eastern

* : "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved for the ancient tribes of northern and eastern Cent ...

also had an influence on the region in the 7th century BC.Ellis, ''Cavalry'', p. 14. By the reign of Ashurbanipal in 669 BC, the Assyrians had learned to sit forward on their horses in the classic riding position still seen today and could be said to be true light cavalry

Light cavalry comprised lightly armed and armored cavalry troops mounted on fast horses, as opposed to heavy cavalry, where the mounted riders (and sometimes the warhorses) were heavily armored. The purpose of light cavalry was primarily ...

. The ancient Greeks

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cult ...

used both light horse scouts and heavy cavalry, although not extensively, possibly due to the cost of keeping horses.

Heavy cavalry

Heavy cavalry was a class of cavalry intended to deliver a battlefield charge and also to act as a tactical reserve; they are also often termed '' shock cavalry''. Although their equipment differed greatly depending on the region and histori ...

was believed to have been developed by the Ancient Persians

The Persians are an Iranian ethnic group who comprise over half of the population of Iran. They share a common cultural system and are native speakers of the Persian language as well as of the languages that are closely related to Persian.

...

, although others argue for the Sarmatians

The Sarmatians (; grc, Σαρμαται, Sarmatai; Latin: ) were a large confederation of ancient Eastern Iranian equestrian nomadic peoples of classical antiquity who dominated the Pontic steppe from about the 3rd century BC to the 4th ...

. By the time of Darius (558–486 BC), Persian military tactics required horses and riders that were completely armoured, and selectively bred

Selective breeding (also called artificial selection) is the process by which humans use animal breeding and plant breeding to selectively develop particular phenotypic traits (characteristics) by choosing which typically animal or plant ma ...

a heavier, more muscled horse to carry the additional weight. The cataphract

A cataphract was a form of armored heavy cavalryman that originated in Persia and was fielded in ancient warfare throughout Eurasia and Northern Africa.

The English word derives from the Greek ' (plural: '), literally meaning "armored" or "c ...

was a type of heavily armoured cavalry with distinct tactics, armour, and weaponry used from the time of the Persians up until the Middle Ages.Bennett and others., ''Fighting Techniques'', pp. 76–81.

In Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cult ...

, Phillip of Macedon

Philip II of Macedon ( grc-gre, Φίλιππος ; 382 – 21 October 336 BC) was the king ('' basileus'') of the ancient kingdom of Macedonia from 359 BC until his death in 336 BC. He was a member of the Argead dynasty, founders of the a ...

is credited with developing tactics allowing massed cavalry charges. The most famous Greek heavy cavalry units were the companion cavalry

The Companions ( el, , ''hetairoi'') were the elite cavalry of the Macedonian army from the time of king Philip II of Macedon, achieving their greatest prestige under Alexander the Great, and regarded as the first or among the first shock ca ...

of Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

.Chamberlin, ''Horse'', pp. 154–158. The Chinese of the 4th century BC during the Warring States period

The Warring States period () was an era in ancient Chinese history characterized by warfare, as well as bureaucratic and military reforms and consolidation. It followed the Spring and Autumn period and concluded with the Qin wars of conquest ...

(403–221 BC) began to use cavalry against rival states.Ebrey and others, ''Pre-Modern East Asia'', pp. 29–30. To fight nomadic raiders from the north and west, the Chinese of the Han dynasty

The Han dynasty (, ; ) was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China (202 BC – 9 AD, 25–220 AD), established by Emperor Gaozu of Han, Liu Bang (Emperor Gao) and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by th ...

(202 BC – 220 AD) developed effective mounted units.Goodrich, ''Short History'', p. 32. Cavalry was not used extensively by the Romans

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

during the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Kingd ...

period, but by the time of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Medite ...

, they made use of heavy cavalry.Ellis, ''Cavalry'', pp. 30–35.Adkins, ''Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome'', pp. 51–55. However, the backbone of the Roman army was the infantry.

Horse artillery

Once gunpowder was invented, another major use of horses was as draught animals for

Once gunpowder was invented, another major use of horses was as draught animals for heavy artillery

The formal definition of large-calibre artillery used by the United Nations Register of Conventional Arms (UNROCA) is "guns, howitzers, artillery pieces, combining the characteristics of a gun, howitzer, mortar, or multiple-launch rocket system ...

, or cannon

A cannon is a large-caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder duri ...

. In addition to field artillery

Field artillery is a category of mobile artillery used to support armies in the field. These weapons are specialized for mobility, tactical proficiency, short range, long range, and extremely long range target engagement.

Until the early 20 ...

, where horse-drawn guns were attended by gunners on foot, many armies had artillery batteries

In military organizations, an artillery battery is a unit or multiple systems of artillery, mortar systems, rocket artillery, multiple rocket launchers, surface-to-surface missiles, ballistic missiles, cruise missiles, etc., so grouped to faci ...

where each gunner was provided with a mount.Nofi, ''The Waterloo Campaign'', p. 124. Horse artillery units generally used lighter pieces, pulled by six horses. "9-pounders" were pulled by eight horses, and heavier artillery pieces needed a team of twelve. With the individual riding horses required for officers, surgeons and other support staff, as well as those pulling the artillery guns and supply wagons, an artillery battery of six guns could require 160 to 200 horses.Nofi, ''The Waterloo Campaign'', pp. 128–130. Horse artillery usually came under the command of cavalry divisions, but in some battles, such as Waterloo, the horse artillery were used as a rapid response force, repulsing attacks and assisting the infantry.Holmes, ''Military History'', p. 415. Agility was important; the ideal artillery horse was high, strongly built, but able to move quickly.

Asia

Central Asia

Relations between

Relations between steppe

In physical geography, a steppe () is an ecoregion characterized by grassland plains without trees apart from those near rivers and lakes.

Steppe biomes may include:

* the montane grasslands and shrublands biome

* the temperate grasslan ...

nomads and the settled people in and around Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes the former ...

were often marked by conflict.Nicolle, ''Medieval Warfare Source Book: Christian Europe and its Neighbors'', p. 185.Ellis, ''Cavalry'', p. 120. The nomadic lifestyle was well suited to warfare, and steppe cavalry became some of the most militarily potent forces in the world, only limited by nomads' frequent lack of internal unity. Periodically, strong leaders would organise several tribes into one force, creating an almost unstoppable power.Nicolle, ''Attila'', pp. 6–10. These unified groups included the Huns

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th century AD. According to European tradition, they were first reported living east of the Volga River, in an area that was par ...

, who invaded Europe,Nicolle, ''Attila'', pp. 20–23. and under Attila

Attila (, ; ), frequently called Attila the Hun, was the ruler of the Huns from 434 until his death in March 453. He was also the leader of a tribal empire consisting of Huns, Ostrogoths, Alans, and Bulgars, among others, in Central and ...

, conducted campaigns in both eastern France and northern Italy, over 500 miles apart, within two successive campaign seasons. Other unified nomadic forces included the Wu Hu attacks on China,Goodrich, ''Short History'', p. 83. and the Mongol conquest

The Mongol invasions and conquests took place during the 13th and 14th centuries, creating history's largest contiguous empire: the Mongol Empire (1206-1368), which by 1300 covered large parts of Eurasia. Historians regard the Mongol devastation ...

of much of Eurasia.Nicolle, ''Medieval Warfare Source Book: Christian Europe and its Neighbors'', pp. 91–94.

South Asia

The literature of ancientIndia

India, officially the Republic of India ( Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the ...

describes numerous horse nomads. Some of the earliest references to the use of horses in South Asian warfare are Puranic

Purana (; sa, , '; literally meaning "ancient, old"Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of Literature (1995 Edition), Article on Puranas, , page 915) is a vast genre of Indian literature about a wide range of topics, particularly about legends an ...

texts, which refer to an attempted invasion of India by the joint cavalry forces of the Saka

The Saka (Old Persian: ; Kharoṣṭhī: ; Ancient Egyptian: , ; , old , mod. , ), Shaka (Sanskrit ( Brāhmī): , , ; Sanskrit (Devanāgarī): , ), or Sacae (Ancient Greek: ; Latin: ) were a group of nomadic Iranian peoples who hist ...

s, Kambojas

Kamboja ( sa, कम्बोज) was a kingdom of Iron Age India that spanned parts of South and Central Asia, frequently mentioned in Sanskrit and Pali literature. Eponymous with the kingdom name, the Kambojas were an Indo-Iranian peopl ...

, Yavanas

The word Yona in Pali and the Prakrits, and the analogue Yavana in Sanskrit and Yavanar in Tamil, were words used in Ancient India to designate Greek speakers. "Yona" and "Yavana" are transliterations of the Greek word for " Ionians" ( grc, ...

, Pahlavas

The Pahlavas are a people mentioned in ancient Indian texts like the Manu Smriti, various Puranas, the Ramayana, the Mahabharata, and the Brihat Samhita. According to P. Carnegy, In the 4th century BCE, Vartika of Katyayana mentions the ''Sakah- ...

, and Paradas, called the "five hordes" (''pañca.ganah'') or " Kśatriya" hordes (''Kśatriya ganah''). About 1600 BC, they captured the throne of Ayodhya

Ayodhya (; ) is a city situated on the banks of holy river Saryu in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh.

Ayodhya, also known as Saketa, is an ancient city of India, the birthplace of Rama and setting of the great epic Ramayana. Ayodhy ...

by dethroning the Vedic

upright=1.2, The Vedas are ancient Sanskrit texts of Hinduism. Above: A page from the '' Atharvaveda''.

The Vedas (, , ) are a large body of religious texts originating in ancient India. Composed in Vedic Sanskrit, the texts constitute the ...

king, Bahu.Partiger, ''Ancient Indian Historical Tradition'', pp. 147–148, 182–183. Later texts, such as the Mahābhārata

The ''Mahābhārata'' ( ; sa, महाभारतम्, ', ) is one of the two major Sanskrit epics of ancient India in Hinduism, the other being the ''Rāmāyaṇa''. It narrates the struggle between two groups of cousins in the Kuru ...

, c. 950 BC, appear to recognise efforts taken to breed war horses and develop trained mounted warriors, stating that the horses of the Sindhu

The Indus ( ) is a transboundary river of Asia and a trans-Himalayan river of South and Central Asia. The river rises in mountain springs northeast of Mount Kailash in Western Tibet, flows northwest through the disputed region of Kash ...

and Kamboja regions were of the finest quality, and the Kambojas, Gandharas, and Yavanas were expert in fighting from horses.

In technological innovation, the early toe loop stirrup is credited to the cultures of India, and may have been in use as early as 500 BC. Not long after, the cultures of

In technological innovation, the early toe loop stirrup is credited to the cultures of India, and may have been in use as early as 500 BC. Not long after, the cultures of Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the F ...

and Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cult ...

clashed with those of central Asia and India. Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria ( Italy). He is known for ...

(484–425 BC) wrote that Gandarian mercenaries of the Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Based in Western Asia, it was contemporarily the largest em ...

were recruited into the army of emperor Xerxes I of Persia

Xerxes I ( peo, 𐎧𐏁𐎹𐎠𐎼𐏁𐎠 ; grc-gre, Ξέρξης ; – August 465 BC), commonly known as Xerxes the Great, was the fourth King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, ruling from 486 to 465 BC. He was the son and successor of ...

(486–465 BC), which he led against the Greeks. A century later, the "Men of the Mountain Land," from north of Kabul River, served in the army of Darius III of Persia

Darius III ( peo, 𐎭𐎠𐎼𐎹𐎺𐎢𐏁 ; grc-gre, Δαρεῖος ; c. 380 – 330 BC) was the last Achaemenid King of Kings of Persia, reigning from 336 BC to his death in 330 BC.

Contrary to his predecessor Artaxerxes IV Arses, Dari ...

when he fought against Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

at Arbela in 331 BC. In battle against Alexander at Massaga in 326 BC, the Assakenoi forces included 20,000 cavalry. The Mudra-Rakshasa

The Mudrarakshasa (मुद्राराक्षस, IAST: ''Mudrārākṣasa'', ) is a Sanskrit-language play by Vishakhadatta that narrates the ascent of the king Chandragupta Maurya ( BCE) to power in India. The play is an example of ...

recounted how cavalry of the Shakas, Yavanas, Kambojas, Kirata

The Kirāta ( sa, किरात) is a generic term in Sanskrit literature for people who had territory in the mountains, particularly in the Himalayas and Northeast India and who are believed to have been Sino-Tibetan in origin. The meaning o ...

s, Parasikas, and Bahlikas

The Bahlikas ( sa, बाह्लिक; ''Bāhlika'') were the inhabitants of Bahlika ( sa, बह्लिक, located in Bactria), mentioned in Atharvaveda, Mahabharata, Ramayana, Puranas, Vartikka of Katyayana, Brhatsamhita, Amarkosha etc. ...

helped Chandragupta Maurya

Chandragupta Maurya (350-295 BCE) was a ruler in Ancient India who expanded a geographically-extensive kingdom based in Magadha and founded the Maurya dynasty. He reigned from 320 BCE to 298 BCE. The Maurya kingdom expanded to become an emp ...

(c. 320–298 BC) defeat the ruler of Magadha

Magadha was a region and one of the sixteen sa, script=Latn, Mahajanapadas, label=none, lit=Great Kingdoms of the Second Urbanization (600–200 BCE) in what is now south Bihar (before expansion) at the eastern Ganges Plain. Magadha was ruled ...

and take the throne, thus laying the foundations of the Mauryan dynasty

The Maurya Empire, or the Mauryan Empire, was a geographically extensive Iron Age historical power in the Indian subcontinent based in Magadha, having been founded by Chandragupta Maurya in 322 BCE, and existing in loose-knit fashion until 1 ...

in Northern India.

Mughal cavalry used gunpowder weapons, but were slow to replace the traditional composite bow.Gordon, ''The Limited Adoption of European-style Military Forces by Eighteenth Century Rulers in India'', pp. 229–232. Under the impact of European military successes in India, some Indian rulers adopted the European system of massed cavalry charges, although others did not.Gordon, ''The Limited Adoption of European-style Military Forces by Eighteenth Century Rulers in India'', p. 241. By the 18th century, Indian armies continued to field cavalry, but mainly of the heavy variety.

East Asia

The Chinese used

The Chinese used chariots

A chariot is a type of cart driven by a charioteer, usually using horses to provide rapid motive power. The oldest known chariots have been found in burials of the Sintashta culture in modern-day Chelyabinsk Oblast, Russia, dated to c. 2000 ...

for horse-based warfare until light cavalry forces became common during the Warring States

The Warring States period () was an era in ancient Chinese history characterized by warfare, as well as bureaucratic and military reforms and consolidation. It followed the Spring and Autumn period and concluded with the Qin wars of conquest ...

era (402–221 BC). A major proponent of the change to riding horses from chariots was King Wuling of Zhao

King Wuling of Zhao () (died 295 BCE, reigned 325 BCE – 299 BCE) reigned in the State of Zhao during the Warring States period of Chinese history. His reign was famous for one important event: the reforms consisting of "Wearing the Hu (styled) A ...

, c. 320 BC. However, conservative forces in China often opposed change, as cavalry did not benefit from the additional cachet attached to being the military branch dominated by the nobility as in medieval Europe.Ellis, ''Cavalry'', pp. 19–20. Nevertheless, during the reign of Emperor Wu of Han

Emperor Wu of Han (156 – 29 March 87BC), formally enshrined as Emperor Wu the Filial (), born Liu Che (劉徹) and courtesy name Tong (通), was the seventh emperor of the Han dynasty of ancient China, ruling from 141 to 87 BC. His reign ...

(r. 141–87 BC), it is recorded that 300,000 government-owned

State ownership, also called government ownership and public ownership, is the ownership of an industry, asset, or enterprise by the state or a public body representing a community, as opposed to an individual or private party. Public ownersh ...

horses were insufficient for the cavalry and baggage train

''Wagon Train'' is an American Western series that aired 8 seasons: first on the NBC television network (1957–1962), and then on ABC (1962–1965). ''Wagon Train'' debuted on September 18, 1957, and became number one in the Nielsen ratings. I ...

s of the Han military

Han may refer to:

Ethnic groups

* Han Chinese, or Han People (): the name for the largest ethnic group in China, which also constitutes the world's largest ethnic group.

** Han Taiwanese (): the name for the ethnic group of the Taiwanese ...

in the campaigns to expel the Xiongnu nomads from the Ordos Desert