History Of The United States (1865–1917) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of the United States from 1865 to 1917 was marked by the

Reconstruction was the period from 1863 to 1877, in which the federal government temporarily took control—one by one—of the Southern states of the Confederacy. Before his assassination in April 1865, President

Reconstruction was the period from 1863 to 1877, in which the federal government temporarily took control—one by one—of the Southern states of the Confederacy. Before his assassination in April 1865, President

In 1869, the

In 1869, the

A dramatic expansion in farming took place. The number of farms tripled from 2.0 million in 1860 to 6.0 million in 1905. The number of people living on farms grew from about 10 million in 1860 to 22 million in 1880 to 31 million in 1905. The value of farms soared from $8.0 billion in 1860 to $30 billion in 1906.

The federal government issued tracts virtually free to settlers under the

A dramatic expansion in farming took place. The number of farms tripled from 2.0 million in 1860 to 6.0 million in 1905. The number of people living on farms grew from about 10 million in 1860 to 22 million in 1880 to 31 million in 1905. The value of farms soared from $8.0 billion in 1860 to $30 billion in 1906.

The federal government issued tracts virtually free to settlers under the

From 1865 to about 1913, the U.S. grew to become the world's leading industrial nation. Land and labor, the diversity of climate, the ample presence of railroads (as well as navigable rivers), and the

From 1865 to about 1913, the U.S. grew to become the world's leading industrial nation. Land and labor, the diversity of climate, the ample presence of railroads (as well as navigable rivers), and the

The most militant working class organization of the 1905–1920 era was the

The most militant working class organization of the 1905–1920 era was the

From 1865 through 1918 an unprecedented and diverse stream of immigrants arrived in the United States, 27.5 million in total. In all, 24.4 million (89%) came from Europe, including 2.9 million from

From 1865 through 1918 an unprecedented and diverse stream of immigrants arrived in the United States, 27.5 million in total. In all, 24.4 million (89%) came from Europe, including 2.9 million from  Immigrants were pushed out of their homelands by poverty or religious threats, and pulled to America by jobs, farmland and kin connections. They found economic opportunity at factories, mines and construction sites, and found farm opportunities in the Plains states.

While most immigrants were welcomed, Asians were not. Many Chinese had been brought to the west coast to construct railroads, but unlike European immigrants, they were seen as being part of an entirely alien culture. After intense anti-Chinese agitation in California and the west, Congress passed the

Immigrants were pushed out of their homelands by poverty or religious threats, and pulled to America by jobs, farmland and kin connections. They found economic opportunity at factories, mines and construction sites, and found farm opportunities in the Plains states.

While most immigrants were welcomed, Asians were not. Many Chinese had been brought to the west coast to construct railroads, but unlike European immigrants, they were seen as being part of an entirely alien culture. After intense anti-Chinese agitation in California and the west, Congress passed the

Even before Reconstruction was officially concluded in 1877, the Supreme Court made a series of rulings curbing the 14th Amendment. Federal attempts at enforcing civil rights essentially ceased until the 1950s.

In the 1896 case ''

Even before Reconstruction was officially concluded in 1877, the Supreme Court made a series of rulings curbing the 14th Amendment. Federal attempts at enforcing civil rights essentially ceased until the 1950s.

In the 1896 case ''

The

The

Spain had once controlled a vast colonial empire, but by the second half of the 19th century only

Spain had once controlled a vast colonial empire, but by the second half of the 19th century only

A new spirit of the times, known as "Progressivism", arose in the 1890s and into the 1920s (although some historians date the ending with World War I).

In 1904, reflecting the age, and perhaps prescient of difficulties arising in the early part of the next millennium (including the rise of a

A new spirit of the times, known as "Progressivism", arose in the 1890s and into the 1920s (although some historians date the ending with World War I).

In 1904, reflecting the age, and perhaps prescient of difficulties arising in the early part of the next millennium (including the rise of a

Conservation of the nation's natural resources and beautiful places was a very high priority for Roosevelt, and he raised the national visibility of the issue. The President called for a far-reaching and integrated program of conservation, reclamation and irrigation as early as 1901 in his first annual message to Congress. Whereas his predecessors had set aside 46 million acres (188,000 km2) of timberland for preservation and parks, Roosevelt increased the area to 146 million acres (592,000 km2) and began systematic efforts to prevent forest fires and to retimber denuded tracts. His appointment of his friend

Conservation of the nation's natural resources and beautiful places was a very high priority for Roosevelt, and he raised the national visibility of the issue. The President called for a far-reaching and integrated program of conservation, reclamation and irrigation as early as 1901 in his first annual message to Congress. Whereas his predecessors had set aside 46 million acres (188,000 km2) of timberland for preservation and parks, Roosevelt increased the area to 146 million acres (592,000 km2) and began systematic efforts to prevent forest fires and to retimber denuded tracts. His appointment of his friend

online

old survey by scholar * Tindall, George B., and David E. Shi. ''America: A Narrative History'' (8th ed. 2009), university textbook * White, Richard. '' The Republic for Which It Stands: The United States During Reconstruction and the Gilded Age, 1865-1896'' (Oxford History of the United States, 2017).

''The Sequel of Appomattox, A Chronicle of the Reunion of the States''(1918)

short survey from

excerpt and text search

** Foner, Eric. ''Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877'' (1988), highly detailed history of Reconstruction emphasizing Black and abolitionist perspective

Hamilton, Peter Joseph. ''The Reconstruction Period''

(1906), history of era using

excerpt

online

* Edwards, Rebecca. ''New Spirits: Americans in the Gilded Age, 1865–1905'' (2005); 304p

excerpt and text search

* Faulkner, Harold U.; ''Politics, Reform, and Expansion, 1890–1900'' (1959), scholarly survey, strong on economic and political histor

online

* Fine, Sidney. ''Laissez Faire and the General-Welfare State: A Study of Conflict in American Thought'', 1865–1901. University of Michigan Press, 1956. * Ford, Henry Jones. ''The Cleveland Era: A Chronicle of the New Order in Politics'' (1921)

short overview online

* Garraty, John A. ''The New Commonwealth, 1877–1890,'' 1968 scholarly survey, strong on economic and political history * Hoffmann, Charles. "The depression of the nineties." ''Journal of Economic History'' 16#2 (1956): 137–164

in JSTOR

* Hoffmann, Charles. ''Depression of the nineties; an economic history'' (1970) * Jensen, Richard. "Democracy, Republicanism and Efficiency: The Values of American Politics, 1885–1930," in Byron Shafer and Anthony Badger, eds, ''Contesting Democracy: Substance and Structure in American Political History, 1775–2000'' (U of Kansas Press, 2001) pp. 149–180

online version

* Kirkland, Edward C. ''Industry Comes of Age, Business, Labor, and Public Policy 1860–1897'' (1961), standard survey * Kleppner; Paul. ''The Third Electoral System 1853–1892: Parties, Voters, and Political Cultures'' U of North Carolina Press, (1979

online

* Morgan, H. Wayne ed. ''The Gilded Age: A Reappraisal'' Syracuse University Press 1970. interpretive essays * Morgan, H. Wayne, ''From Hayes to McKinley: National Party Politics, 1877–1896'' (1969) * Nevins, Allan. ''John D. Rockefeller: The Heroic Age of American Enterprise'' (1940); 710pp; favorable scholarly biography

online

* Nevins, Allan. ''The Emergence of Modern America, 1865–1878'' (1933) , social history * Oberholtzer, Ellis Paxson. ''A History of the United States since the Civil War. Volume V, 1888–1901'' (Macmillan, 1937). 791pp; comprehensive old-fashioned political history * Rhodes, James Ford. ''History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850: 1877–1896'' (1919

online complete

old, factual and heavily political, by winner of Pulitzer Prize * Shannon, Fred A. ''The farmer's last frontier: agriculture, 1860–1897'' (1945

complete text online

* Smythe, Ted Curtis; ''The Gilded Age Press, 1865–1900'' Praeger. 2003.

online version

* Kagan Robert. ''The Ghost at the Feast: America and the Collapse of World Order, 1900–1941'' (Knopf, 2023

excerpt

* Kennedy, David M. ed., ''Progressivism: The Critical Issues'' (1971), readings * Mann, Arthur. ed., ''The Progressive Era'' (1975), readings * McGerr, Michael. ''A Fierce Discontent: The Rise and Fall of the Progressive Movement in America, 1870–1920'' (2003) * Mowry, George. ''The Era of Theodore Roosevelt and the Birth of Modern America, 1900–1912.'' survey by leading scholar * Pease, Otis, ed. ''The Progressive Years: The Spirit and Achievement of American Reform'' (1962), primary documents * Thelen, David P. "Social Tensions and the Origins of Progressivism," ''Journal of American History'' 56 (1969), 323–34

in JSTOR

* ; 904pp; full scale scholarly biography; winner of Pulitzer Prize

online free; 2nd ed. 1965

* Wiebe, Robert. ''The Search For Order, 1877–1920'' (1967), influential interpretation

excerpt and text search

H-SHGAPE discussion forum for people studying the Gilded Age and Progressive Era

Photographs of prominent politicians, 1861-1922; these are pre-1923 and out of copyright

* ttp://www.gilderlehrman.org The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History

Shapell Manuscript Foundation

{{DEFAULTSORT:History Of The United States (1865-1918) 1860s in the United States 1870s in the United States 1880s in the United States 1890s in the United States 1900s in the United States 1910s in the United States Progressive Era in the United States History of the United States by period

Reconstruction era

The Reconstruction era was a period in History of the United States, US history that followed the American Civil War (1861-65) and was dominated by the legal, social, and political challenges of the Abolitionism in the United States, abol ...

, the Gilded Age

In History of the United States, United States history, the Gilded Age is the period from about the late 1870s to the late 1890s, which occurred between the Reconstruction era and the Progressive Era. It was named by 1920s historians after Mar ...

, and the Progressive Era

The Progressive Era (1890s–1920s) was a period in the United States characterized by multiple social and political reform efforts. Reformers during this era, known as progressivism in the United States, Progressives, sought to address iss ...

, and includes the rise of industrialization

Industrialisation (British English, UK) American and British English spelling differences, or industrialization (American English, US) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an i ...

and the resulting surge of immigration in the United States

Immigration to the United States has been a major source of population growth and Culture of the United States, cultural change throughout much of history of the United States, its history. As of January 2025, the United States has the la ...

.

This period of rapid economic growth and soaring prosperity in the Northern United States

The Northern United States, commonly referred to as the American North, the Northern States, or simply the North, is a geographical and historical region of the United States.

History Early history

Before the 19th century westward expansion, the ...

and the Western United States

The Western United States (also called the American West, the Western States, the Far West, the Western territories, and the West) is List of regions of the United States, census regions United States Census Bureau.

As American settlement i ...

saw the U.S. become the world's dominant economic, industrial, and agricultural power. The average annual income (after inflation) of non-farm workers grew by 75% from 1865 to 1900, and then grew another 33% by 1918.

With a victory in 1865 over the Southern Confederate States

The Confederate States of America (CSA), also known as the Confederate States (C.S.), the Confederacy, or Dixieland, was an unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United States from 1861 to 1865. It comprised eleven U.S. states th ...

in the Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

, the United States became a united nation with a stronger national government. Reconstruction brought the end of legalized slavery plus citizenship for the former slaves, but their new-found political power was rolled back within a decade, and they became second-class citizens under a "Jim Crow

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws introduced in the Southern United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that enforced racial segregation, " Jim Crow" being a pejorative term for an African American. The last of the ...

" system of deeply pervasive segregation Segregation may refer to:

Separation of people

* Geographical segregation, rates of two or more populations which are not homogenous throughout a defined space

* School segregation

* Housing segregation

* Racial segregation, separation of human ...

that would stand for the next 80–90 years. Politically, during the Third Party System

The Third Party System was a period in the history of political parties in the United States from the 1850s until the 1890s, which featured profound developments in issues of American nationalism, modernization, and race. This period was marke ...

and Fourth Party System

The Fourth Party System was the political party system in the United States from about 1896 to 1932 that was dominated by the Republican Party, except the 1912 split in which Democrats captured the White House and held it for eight years.

Am ...

the nation was mostly dominated by Republicans (except for two Democratic presidents). After 1900 and the assassination of President William McKinley, the Progressive Era brought political, business, and social reforms (e.g., new roles for and government expansion of education, higher status for women, a curtailment of corporate excesses, and modernization of many areas of government and society). The Progressives worked through new middle-class organizations to fight against the corruption and behind-the-scenes power of entrenched, state political party organizations and big-city "machines

A machine is a physical system that uses power to apply forces and control movement to perform an action. The term is commonly applied to artificial devices, such as those employing engines or motors, but also to natural biological macromolec ...

". They demanded—and won—women's right to vote

Women's suffrage is the women's rights, right of women to Suffrage, vote in elections. Several instances occurred in recent centuries where women were selectively given, then stripped of, the right to vote. In Sweden, conditional women's suffra ...

, and the nationwide prohibition of alcohol 1920–1933.

In an unprecedented wave of European immigration

Immigration is the international movement of people to a destination country of which they are not usual residents or where they do not possess nationality in order to settle as Permanent residency, permanent residents. Commuting, Commuter ...

, 27.5 million new arrivals between 1865 and 1918U.S. Bureau of the Census, ''Historical Statistics of the United States'' (1976) series C89 provided the labor base necessary for the expansion of industry and agriculture, as well as the population base for most of fast-growing urban America.

By the late nineteenth century, the United States had become a leading global industrial power, building on new technologies (such as the telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas ...

and steel

Steel is an alloy of iron and carbon that demonstrates improved mechanical properties compared to the pure form of iron. Due to steel's high Young's modulus, elastic modulus, Yield (engineering), yield strength, Fracture, fracture strength a ...

), an expanding railroad network, and abundant natural resources

Natural resources are resources that are drawn from nature and used with few modifications. This includes the sources of valued characteristics such as commercial and industrial use, aesthetic value, scientific interest, and cultural value. ...

such as coal, timber, oil, and farmland, to usher in the Second Industrial Revolution

The Second Industrial Revolution, also known as the Technological Revolution, was a phase of rapid Discovery (observation), scientific discovery, standardisation, mass production and industrialisation from the late 19th century into the early ...

.

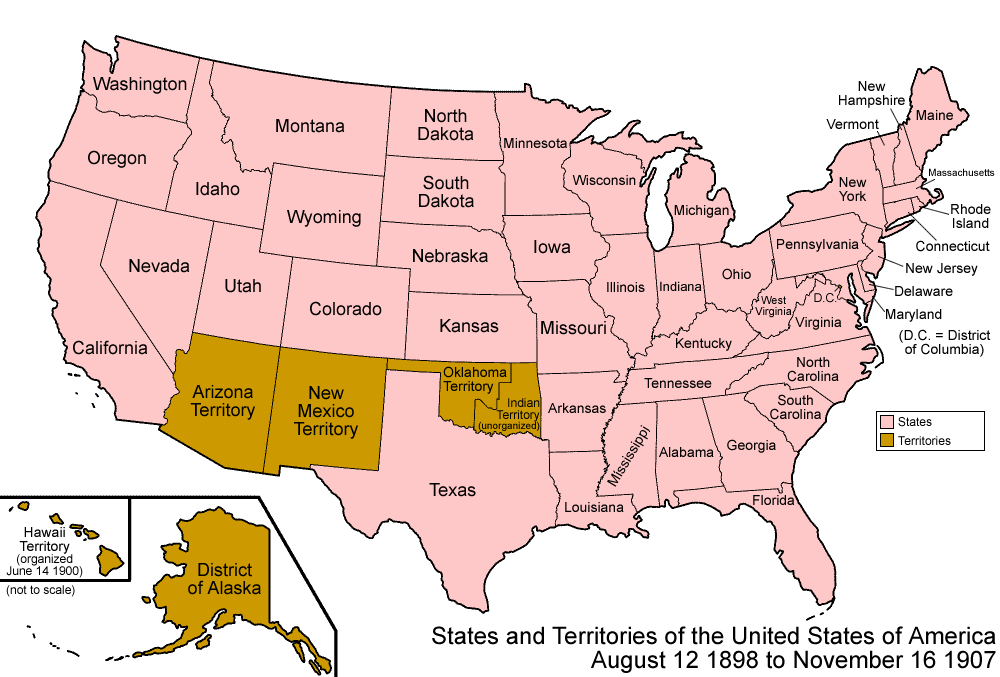

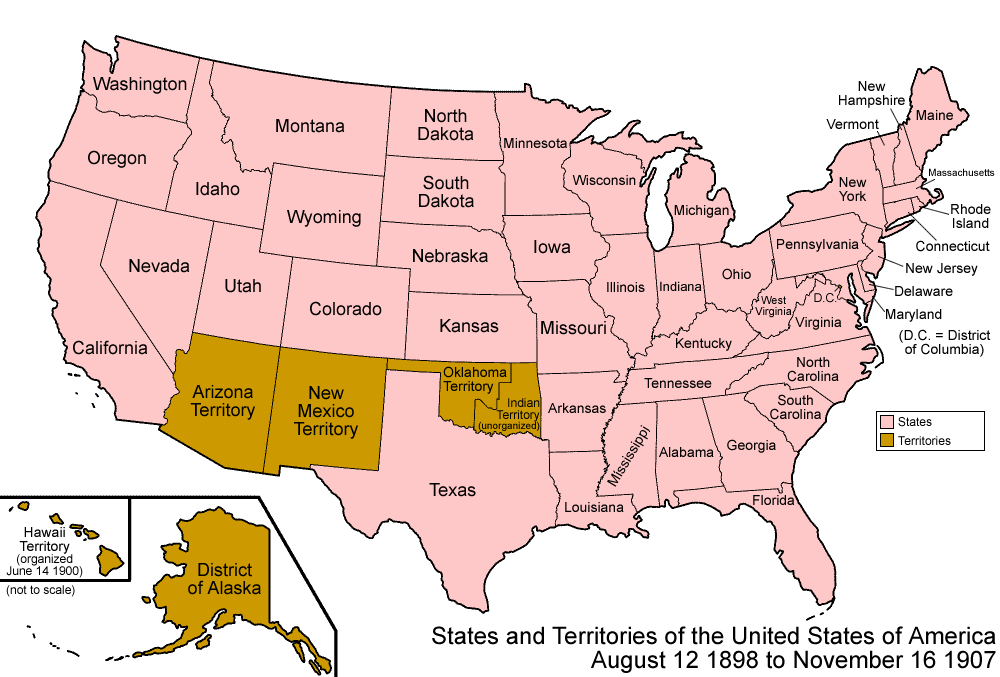

It was also during this period that the United States began to emerge as a global superpower. The U.S. easily defeated Spain in 1898, which unexpectedly brought a small empire. Cuba quickly was given independence, and the Philippines eventually became independent in 1946. Puerto Rico

; abbreviated PR), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, is a Government of Puerto Rico, self-governing Caribbean Geography of Puerto Rico, archipelago and island organized as an Territories of the United States, unincorporated territo ...

(and some smaller islands) became permanent U.S. territories, as did Alaska

Alaska ( ) is a non-contiguous U.S. state on the northwest extremity of North America. Part of the Western United States region, it is one of the two non-contiguous U.S. states, alongside Hawaii. Alaska is also considered to be the north ...

(added by purchase in 1867). The independent Republic of Hawaii

The Republic of Hawaii (Hawaiian language, Hawaiian: ''Lepupalika o Hawaii'' epupəˈlikə o həˈvɐjʔi was a short-lived one-party state in Hawaii, Hawaii between July 4, 1894, when the Provisional Government of Hawaii had Black Week (H ...

was annexed

Annexation, in international law, is the forcible acquisition and assertion of legal title over one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. In current international law, it is generally held to ...

by the U.S. as a territory in 1898.

Reconstruction era

Reconstruction was the period from 1863 to 1877, in which the federal government temporarily took control—one by one—of the Southern states of the Confederacy. Before his assassination in April 1865, President

Reconstruction was the period from 1863 to 1877, in which the federal government temporarily took control—one by one—of the Southern states of the Confederacy. Before his assassination in April 1865, President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

had announced moderate plans for reconstruction to re-integrate the former Confederates as fast as possible. Lincoln set up the Freedmen's Bureau

The Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, usually referred to as simply the Freedmen's Bureau, was a U.S. government agency of early post American Civil War Reconstruction, assisting freedmen (i.e., former enslaved people) in the ...

in March 1865, to aid former enslaved people in finding education, health care, and employment. The final abolition of slavery was achieved by the Thirteenth Amendment, ratified in December 1865. However, Lincoln was opposed by the Radical Republicans

The Radical Republicans were a political faction within the Republican Party originating from the party's founding in 1854—some six years before the Civil War—until the Compromise of 1877, which effectively ended Reconstruction. They ca ...

within his own party who feared that the former Confederates would never truly give up on slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

and Confederate nationalism, and would always try to reinstate them behind-the-scenes. As a result, the Radical Republicans tried to impose legal restrictions that would strip most ex-rebels' rights to vote and hold elected office. The Radicals were opposed by Lincoln's vice president and successor, Tennessee Democrat Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. The 16th vice president, he assumed the presidency following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a South ...

. However, the Radicals won the critical elections of 1866, winning enough seats in Congress to override President Johnson's vetoes of such legislation. They even successfully impeached President Johnson (in the House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entities. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often ...

), and almost removed him from office (in the Senate) in 1868. Meanwhile, they gave the South's "freedmen" new constitutional and federal legal protections.

The Radicals' reconstruction plans took effect in 1867 under the supervision of the U.S. Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of the United Stat ...

, allowing a Republican coalition

The Republican Coalition (), previously known as the Multicolor Coalition (), is a big tent political coalition formed in Uruguay in 2019.

It is led by Uruguayan ex-president Luis Lacalle Pou and is composed of Lacalle's centre-right National ...

of Freedmen, sympathetic local whites, and recent arrivals from the North to take control of Southern state governments. They ratified the Fourteenth Amendment, giving enormous new powers to the federal courts to deal with justice at the state level. These state governments borrowed heavily to build railroads and public schools, increasing taxation rates. The backlash of increasingly fierce opposition to these policies drove most of the sympathetic local whites out of the Republican Party and into the Democratic Party. President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was the 18th president of the United States, serving from 1869 to 1877. In 1865, as Commanding General of the United States Army, commanding general, Grant led the Uni ...

enforced civil rights protections for African-Americans that were being challenged in South Carolina

South Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders North Carolina to the north and northeast, the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast, and Georgia (U.S. state), Georg ...

, Mississippi

Mississippi ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Alabama to the east, the Gulf of Mexico to the south, Louisiana to the s ...

, and Louisiana

Louisiana ( ; ; ) is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It borders Texas to the west, Arkansas to the north, and Mississippi to the east. Of the 50 U.S. states, it ranks 31st in area and 25 ...

. The Fifteenth Amendment was ratified in 1870 giving African-Americans the right to vote in American elections.

U.S. Representative Thaddeus Stevens

Thaddeus Stevens (April 4, 1792August 11, 1868) was an American politician and lawyer who served as a member of the United States House of Representatives from Pennsylvania, being one of the leaders of the Radical Republican faction of the Histo ...

was one of the major policymakers regarding Reconstruction, and obtained a House vote of impeachment against President Andrew Johnson. Hans Trefousse, his leading biographer, concludes that Stevens "was one of the most influential representatives ever to serve in Congress. e dominatedthe House with his wit, knowledge of parliamentary law, and sheer willpower, even though he was often unable to prevail."

Reconstruction ended at different times in each state, the last in 1877, when Republican Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was the 19th president of the United States, serving from 1877 to 1881.

Hayes served as Cincinnati's city solicitor from 1858 to 1861. He was a staunch Abolitionism in the Un ...

won the contentious presidential election of 1876 over his opponent, Samuel J. Tilden. To deal with disputed electoral votes, Congress set up an Electoral Commission. It awarded the disputed votes to Hayes. The white South accepted the "Compromise of 1877

The Compromise of 1877, also known as the Wormley Agreement, the Tilden-Hayes Compromise, the Bargain of 1877, or Corrupt bargain, the Corrupt Bargain, was a speculated unwritten political deal in the United States to settle the intense dispute ...

" knowing that Hayes proposed to end Army control over the remaining three state governments in Republican hands. White Northerners accepted that the Civil War was over and that Southern whites posed no threat to the nation.

The end of Reconstruction marked the end of the brief period of civil rights and civil liberties for African Americans in the South, where most lived. Reconstruction caused permanent resentment, distrust, and cynicism among white Southerners toward the federal government, and helped create the "Solid South," which typically voted for the (then-)socially conservative Democrat

In American politics, a conservative Democrat is a member of the Democratic Party with more conservative views than most Democrats. Traditionally, conservative Democrats have been elected to office from the Southern states, rural areas, and t ...

s for all local, state, and national offices. White supremacists

White supremacy is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White supremacy has roots in the now-discredited doctrine o ...

created a segregated society through "Jim Crow Laws

The Jim Crow laws were U.S. state, state and local laws introduced in the Southern United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that enforced Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, "Jim Crow (character), Ji ...

" that made black people second-class citizens with very little political power or public voice. The white elites (called the "Redeemers

The Redeemers were a political coalition in the Southern United States during the Reconstruction era of the United States, Reconstruction Era that followed the American Civil War. Redeemers were the Southern wing of the Democratic Party (Unite ...

"—the southern wing of the "Bourbon Democrats

Bourbon Democrat was a term used in the United States in the later 19th century and early 20th century (1872–1904) to refer to members of the Democratic Party who were ideologically aligned with fiscal conservatism or classical liberalism, es ...

") were in firm political and economic control of the south until the rise of the Populist movement in the 1890s. Local law enforcement was weak in rural areas, allowing outraged mobs to use lynching

Lynching is an extrajudicial killing by a group. It is most often used to characterize informal public executions by a mob in order to punish an alleged or convicted transgressor or to intimidate others. It can also be an extreme form of i ...

to redress alleged-but-often-unproven crimes charged to black people.

Historians' interpretations of the Radical Republicans have dramatically shifted over the years, from the pre-1950 view of them as tools of big business

Big business involves large-scale corporate-controlled financial or business activities. As a term, it describes activities that run from "huge transactions" to the more general "doing big things". In corporate jargon, the concept is commonly ...

motivated by partisanship and hatred of the white South, to the perspective of the neoabolitionists of the 1950s and afterwards, who applauded their efforts to give equal rights to the freed slaves.

In the South itself the interpretation of the tumultuous 1860s differed sharply by race. Americans often interpreted great events in religious terms. Historian Wilson Fallin contrasts the interpretation of Civil War and Reconstruction in white versus black using Baptist sermons in Alabama. White preachers expressed the view that:

: God had chastised them and given them a special mission – to maintain orthodoxy, strict Biblicism

Biblical literalism or biblicism is a term used differently by different authors concerning biblical interpretation. It can equate to the dictionary definition of literalism: "adherence to the exact letter or the literal sense", where literal me ...

, personal piety, and traditional race relations. Slavery, they insisted, had not been sinful. Rather, emancipation was a historical tragedy and the end of Reconstruction was a clear sign of God's favor.

In sharp contrast, Black preachers interpreted the Civil War, emancipation and Reconstruction as:

: God's gift of freedom. They appreciated opportunities to exercise their independence, to worship in their own way, to affirm their worth and dignity, and to proclaim the fatherhood of God and the brotherhood of man. Most of all, they could form their own churches, associations, and conventions. These institutions offered self-help and racial uplift, and provided places where the gospel of liberation could be proclaimed. As a result, black preachers continued to insist that God would protect and help them; God would be their rock in a stormy land.

Historians in the 21st century typically consider Reconstruction to be a failure, but they "disagree on what caused Reconstruction to fail, focusing on whether it went too far, too fast or did not go far enough."

However, historian Mark Summers in 2014 sees a positive outcome:

:if we see Reconstruction's purpose as making sure that the main goals of the war would be filled, of a Union held together forever, of a North and South able to work together, of slavery extirpated, and sectional rivalries confined, of a permanent banishment of the fear of vaunting appeals to state sovereignty, backed by armed force, then Reconstruction looks like what in that respect it was, a lasting and unappreciated success.

The West

In 1869, the

In 1869, the first transcontinental railroad

America's first transcontinental railroad (known originally as the "Pacific Railroad" and later as the "Overland Route (Union Pacific Railroad), Overland Route") was a continuous railroad line built between 1863 and 1869 that connected the exis ...

opened up the far west mining and ranching regions. Travel from New York to San Francisco now took six days instead of six months. After the Civil War, many from the East Coast and Europe were lured west by reports from relatives and by extensive advertising campaigns promising "the Best Prairie Lands", "Low Prices", "Large Discounts For Cash", and "Better Terms Than Ever!". The new railroads provided the opportunity for migrants to go out and take a look, with special family tickets, the cost of which could be applied to land purchases offered by the railroads. Farming the plains was indeed more difficult than back east. Water management was more critical, lightning fires were more prevalent, the weather was more extreme, rainfall was less predictable. The fearful stayed home. The actual migrants looked beyond fears of the unknown. Their chief motivation to move west was to find a better economic life than the one they had. Farmers sought larger, cheaper and more fertile land; merchants and tradesmen sought new customers and new leadership opportunities. Laborers wanted higher paying work and better conditions. With the Homestead Act of 1862

The Homestead Acts were several laws in the United States by which an applicant could acquire ownership of government land or the public domain, typically called a homestead. In all, more than of public land, or nearly 10 percent of t ...

providing free land to citizens and the railroads selling cheap lands to European farmers, the settlement of the Great Plains

The Great Plains is a broad expanse of plain, flatland in North America. The region stretches east of the Rocky Mountains, much of it covered in prairie, steppe, and grassland. They are the western part of the Interior Plains, which include th ...

was swiftly accomplished, and the frontier had virtually ended by 1890.

American Indian assimilation

Expansion into the plains and mountains by miners, ranchers and most of settlers led to conflict with some of the regional American Indian tribes. The government insisted the American Indians either move into the general society and become assimilated, or remain on assigned reservations. State and territorialmilitias

A militia ( ) is a military or paramilitary force that comprises civilian members, as opposed to a professional standing army of regular, full-time military personnel. Militias may be raised in times of need to support regular troops or serve ...

used force to keep those choosing reservation life from threatening nearby tribes or settlers. The violence petered out in the 1880s and practically ceased after 1890. By 1880 the buffalo herds, a foundation for the hunting economy, had disappeared.

American Indians had the choice of living on reservations. The US government provided food, supplies, education and medical care. Individuals could move out on their own in Western society and earning wages, typically on a ranch. Reformers wanted to give as many American Indians as possible the opportunity to own and operate their own farms and ranches, and the issue was how to give individual Indians land owned by the tribe. To assimilate the Indians into American society, reformers set up training programs and schools, such as the Carlisle Indian Industrial School

The United States Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, generally known as Carlisle Indian Industrial School, was the flagship Indian boarding school in the United States from its founding in 1879 to 1918. It was based in the histo ...

in Carlisle, Pennsylvania

Carlisle is a Borough (Pennsylvania), borough in and the county seat of Cumberland County, Pennsylvania, United States. Carlisle is located within the Cumberland Valley, a highly productive agricultural region. As of the 2020 United States census ...

, that produced many prominent Indian leaders. The anti-assimilation traditionalists on the reservations, however, resisted integration. The reformers decided the solution was to allow Indians still on reservations to own land as individuals.

The Dawes Act

The Dawes Act of 1887 (also known as the General Allotment Act or the Dawes Severalty Act of 1887) regulated land rights on tribal territories within the United States. Named after Senator Henry L. Dawes of Massachusetts, it authorized the P ...

of 1887 was an effort to integrate American Indians into the mainstream; the majority accepted integration and were absorbed into American society, leaving a trace of American Indian ancestry in millions of American families. Those who refused to assimilate remained in poverty on the reservations, supported by Federal food, medicine and schooling. In 1934, U.S. policy was reversed again by the Indian Reorganization Act

The Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of June 18, 1934, or the Wheeler–Howard Act, was U.S. federal legislation that dealt with the status of American Indians in the United States. It was the centerpiece of what has been often called the "Indian ...

which attempted to protect tribal and communal life on the reservations.

Farming

A dramatic expansion in farming took place. The number of farms tripled from 2.0 million in 1860 to 6.0 million in 1905. The number of people living on farms grew from about 10 million in 1860 to 22 million in 1880 to 31 million in 1905. The value of farms soared from $8.0 billion in 1860 to $30 billion in 1906.

The federal government issued tracts virtually free to settlers under the

A dramatic expansion in farming took place. The number of farms tripled from 2.0 million in 1860 to 6.0 million in 1905. The number of people living on farms grew from about 10 million in 1860 to 22 million in 1880 to 31 million in 1905. The value of farms soared from $8.0 billion in 1860 to $30 billion in 1906.

The federal government issued tracts virtually free to settlers under the Homestead Act

The Homestead Acts were several laws in the United States by which an applicant could acquire ownership of Federal lands, government land or the American frontier, public domain, typically called a Homestead (buildings), homestead. In all, mo ...

of 1862. Even larger numbers purchased lands at very low interest from the new railroads, which were trying to create markets. The railroads advertised heavily in Europe and brought over, at low fares, hundreds of thousands of farmers from Germany, Scandinavia and Britain.

Despite their remarkable progress and general prosperity, 19th-century U.S. farmers experienced recurring cycles of hardship, caused primarily by falling world prices for cotton and wheat.

Along with the mechanical improvements which greatly increased yield per unit area, the amount of land under cultivation grew rapidly throughout the second half of the century, as the railroads opened up new areas of the West for settlement. The wheat farmers enjoyed abundant output and good years from 1876 to 1881 when bad European harvests kept the world price high. They then suffered from a slump in the 1880s when conditions in Europe improved. The farther west the settlers went, the more dependent they became on the monopolistic railroads to move their goods to market, and the more inclined they were to protest, as in the Populist movement of the 1890s. Wheat farmers blamed local grain elevator

A grain elevator or grain terminal is a facility designed to stockpile or store grain. In the grain trade, the term "grain elevator" also describes a tower containing a bucket elevator or a pneumatic conveyor, which scoops up grain from a lowe ...

owners (who purchased their crop), railroads and eastern bankers for the low prices.

The first organized effort to address general agricultural problems was the Grange movement

The National Grange, also known as The Grange and officially named The National Grange of the Order of Patrons of Husbandry, is a social organization in the United States that encourages families to band together to promote the economic and pol ...

that reached out to farmers. It grew to 20,000 chapters and 1.6 million members. The Granges set up their own marketing systems, stores, processing plants, factories and cooperative

A cooperative (also known as co-operative, coöperative, co-op, or coop) is "an autonomy, autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly owned a ...

s. Most went bankrupt. The movement also enjoyed some political success during the 1870s. A few Midwestern states passed "Granger Laws

The Granger Laws were a series of laws passed in several midwestern states of the United States, namely Minnesota, Iowa, Wisconsin, and Illinois, in the late 1860s and early 1870s.American History, “The Granger Laws,” From Revolution to Reconst ...

", limiting railroad and warehouse fees.

Family life

Few single men attempted to operate a farm; farmers clearly understood the need for a hard-working wife, and numerous children, to handle the many chores, including child-rearing, feeding and clothing the family, managing the housework, and feeding the hired hands. During the early years of settlement, farm women played an integral role in assuring family survival by working outdoors. After a generation or so, women increasingly left the fields, thus redefining their roles within the family. New conveniences such as sewing and washing machines encouraged women to turn to domestic roles. This was further supported by the scientific housekeeping movement, promoted across the land by the media and government extension agents, as well as county fairs which featured achievements in home cookery and canning, advice columns for women in the farm papers, and home economics courses in the schools. Although the eastern image of farm life on the prairies emphasizes the isolation of the lonely farmer and farm life, in reality rural folk created a rich social life for themselves. For example, many joined a local branch of the Grange; a majority had ties to local churches. It was popular to organize activities that combined practical work, abundant food, and simple entertainment such asbarn raising

A barn raising, also historically called a raising bee or rearing in the U.K., is an action in which a barn for a resident of a community is built or rebuilt collectively by its members. Barn raising was particularly common in 18th- and 19th-cen ...

s, corn huskings, and quilting bees. One could keep busy with scheduled Grange meetings, church services, and school functions. The womenfolk organized shared meals and potluck events, as well as extended visits between families.

Childhood on the American frontier is contested territory. One group of scholars argues the rural environment was salubrious for it allowed children to break loose from urban hierarchies of age and gender, promoted family interdependence, and in the end produced children who were more self-reliant, mobile, adaptable, responsible, independent and more in touch with nature than their urban or eastern counterparts. However other historians offer a grim portrait of loneliness, privation, abuse, and demanding physical labor from an early age.

Industrialization

natural resources

Natural resources are resources that are drawn from nature and used with few modifications. This includes the sources of valued characteristics such as commercial and industrial use, aesthetic value, scientific interest, and cultural value. ...

all fostered the cheap extraction of energy, fast transport, and the availability of capital that powered this Second Industrial Revolution

The Second Industrial Revolution, also known as the Technological Revolution, was a phase of rapid Discovery (observation), scientific discovery, standardisation, mass production and industrialisation from the late 19th century into the early ...

. The average annual income (after inflation) of non-farm workers grew by 75% from 1865 to 1900, and then grew another 33% by 1918.

Where the First Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, sometimes divided into the First Industrial Revolution and Second Industrial Revolution, was a transitional period of the global economy toward more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes, succee ...

shifted production from artisans to factories, the Second Industrial Revolution pioneered an expansion in organization, coordination, and the scale of industry

Industry may refer to:

Economics

* Industry (economics), a generally categorized branch of economic activity

* Industry (manufacturing), a specific branch of economic activity, typically in factories with machinery

* The wider industrial sector ...

, spurred on by technology and transportation advancements. Railroads opened the West, creating farms, towns, and markets where none had existed. The first transcontinental railroad

America's first transcontinental railroad (known originally as the "Pacific Railroad" and later as the "Overland Route (Union Pacific Railroad), Overland Route") was a continuous railroad line built between 1863 and 1869 that connected the exis ...

, built by nationally oriented entrepreneurs with British money and Irish and Chinese

Chinese may refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people identified with China, through nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**Han Chinese, East Asian ethnic group native to China.

**'' Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic ...

labor, provided access to previously remote expanses of land. Railway construction boosted opportunities for capital, credit, and would-be farmers.

New technologies in iron and steel manufacturing, such as the Bessemer process

The Bessemer process was the first inexpensive industrial process for the mass production of steel from molten pig iron before the development of the open hearth furnace. The key principle is steelmaking, removal of impurities and undesired eleme ...

and open-hearth furnace

An open-hearth furnace or open hearth furnace is any of several kinds of industrial furnace in which excess carbon and other impurities are burnt out of pig iron to produce steel. Because steel is difficult to manufacture owing to its high mel ...

, combined with similar innovations in chemistry and other sciences to vastly improve productivity. New communication tools, such as the telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas ...

and telephone

A telephone, colloquially referred to as a phone, is a telecommunications device that enables two or more users to conduct a conversation when they are too far apart to be easily heard directly. A telephone converts sound, typically and most ...

allowed corporate managers to coordinate across great distances. Innovations also occurred in how work was organized, typified by Frederick Winslow Taylor

Frederick Winslow Taylor (March 20, 1856 – March 21, 1915) was an American mechanical engineer. He was widely known for his methods to improve industrial efficiency. He was one of the first management consulting, management consultants. In 190 ...

's ideas of scientific management

Scientific management is a theory of management that analyzes and synthesizes workflows. Its main objective is improving economic efficiency, especially labor productivity. It was one of the earliest attempts to apply science to the engineer ...

.

To finance the larger-scale enterprises required during this era, the corporation emerged as the dominant form of business organization. Corporations expanded by merging, creating single firms out of competing firms known as "trusts

A trust is a legal relationship in which the owner of property, or any transferable right, gives it to another to manage and use solely for the benefit of a designated person. In the English common law, the party who entrusts the property is k ...

" (a form of monopoly). High tariffs sheltered U.S. factories and workers from foreign competition, especially in the woolen industry. Federal railroad land grants enriched investors, farmers and railroad workers, and created hundreds of towns and cities. Business often went to court to stop labor from organizing into unions or from organizing strikes.

The nation's industrial base remained firmly rooted in the Northeast and Midwestern states. The South benefited less and remained poor, rural, and backward, although the abolition of slavery and the breakup of large plantations after the Civil War had a leveling effect and reduced the wealth inequality that had become a serious problem in the late antebellum period—during the postwar years it became possible for many lower class Southerners to own land for the first time. The South did not attract immigration outside New Orleans

New Orleans (commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy among other nicknames) is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 at the 2020 ...

due to its lack of major port cities and the ethnic makeup of the non-black population remained primarily Anglo-Irish with small communities of Jews, French Huguenots, and Germans. Some Southerners felt keenly aware of their backwardness and believed the South ought to compete with Northern industry—one Atlanta newspaper editor in the 1880s wrote "A Confederate army veteran died. He was buried in a Yankee suit in a Yankee coffin in a hole dug with a Yankee shovel. The only things the South furnished were the hole and the corpse." Attempts at trying to set up industry in the South met with only modest success as the region lacked investment money and Northern financiers were content to keep the place as a source of raw materials for Northern factories. The sweltering summer weather of the region also discouraged industrial activity. The most successful Southern industrial venture by far was textiles which benefited from low labor costs and right to work laws forbidding workers from unionizing.

Powerful industrialists, such as Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie ( , ; November 25, 1835August 11, 1919) was a Scottish-American industrialist and philanthropist. Carnegie led the expansion of the History of the iron and steel industry in the United States, American steel industry in the late ...

, John D. Rockefeller

John Davison Rockefeller Sr. (July 8, 1839 – May 23, 1937) was an American businessman and philanthropist. He was one of the List of richest Americans in history, wealthiest Americans of all time and one of the richest people in modern hist ...

and Jay Gould

Jason Gould (; May 27, 1836 – December 2, 1892) was an American railroad magnate and financial speculator who founded the Gould family, Gould business dynasty. He is generally identified as one of the Robber baron (industrialist), robber bar ...

, known collectively by their critics as " robber barons", held great wealth and power, so much so that in 1888 Rutherford B. Hayes noted in his diary that the United States ceased being a government for the people and had been replaced by a "government of the corporation, by the corporation, and for the corporation." Critics in this period also bemoaned the disappearance of great political minds in America—the age of Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and Henry Clay was gone and the nation's best and brightest gravitated to industry rather than government or politics. In a context of cutthroat competition for wealth accumulation, the skilled labor of artisans gave way to well-paid skilled workers and engineers, as the nation deepened its technological base. Meanwhile, a steady stream of immigrants

Immigration is the international movement of people to a destination country of which they are not usual residents or where they do not possess nationality in order to settle as permanent residents. Commuters, tourists, and other short- ...

encouraged the availability of cheap labor, especially in mining

Mining is the Resource extraction, extraction of valuable geological materials and minerals from the surface of the Earth. Mining is required to obtain most materials that cannot be grown through agriculture, agricultural processes, or feasib ...

and manufacturing

Manufacturing is the creation or production of goods with the help of equipment, labor, machines, tools, and chemical or biological processing or formulation. It is the essence of the

secondary sector of the economy. The term may refer ...

.

Labor and management

In the fast-growing industrial sector, wages were about double the level in Europe, but the work was harder with less leisure. Economic depressions swept the nation in 1873–75 and 1893–97, with low prices for farm goods and heavy unemployment in factories and mines. Full prosperity returned in 1897 and continued (with minor dips) to 1920. The pool of unskilled labor was constantly growing, as unprecedented numbers of immigrants—27.5 million between 1865 and 1918 —entered the U.S. Most were young men eager for work. The rapid growth of engineering and the need to master the new technology created a heavy demand for engineers, technicians, and skilled workers. Before 1874, whenMassachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

passed the nation's first legislation limiting the number of hours women and child factory workers could perform to 10 hours a day, virtually no labor legislation existed in the country. Child labor reached a peak around 1900 and then declined (except in Southern textile mills) as compulsory education laws kept children in school. It was finally ended in the 1930s.

Labor organization

The first major effort to organize workers' groups on a nationwide basis appeared with The Noble Order of theKnights of Labor

The Knights of Labor (K of L), officially the Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor, was the largest American labor movement of the 19th century, claiming for a time nearly one million members. It operated in the United States as well in ...

in 1869. Originally a secret, ritualistic society organized by Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

garment workers, it was open to all workers, including African Americans, women, and farmers. The Knights grew slowly until they succeeded in facing down the great railroad baron, Jay Gould

Jason Gould (; May 27, 1836 – December 2, 1892) was an American railroad magnate and financial speculator who founded the Gould family, Gould business dynasty. He is generally identified as one of the Robber baron (industrialist), robber bar ...

, in an 1885 strike. Within a year, they added 500,000 workers to their rolls, far more than the thin leadership structure of the Knights could handle.

The Knights of Labor soon fell into decline, and their place in the labor movement was gradually taken by the American Federation of Labor

The American Federation of Labor (A.F. of L.) was a national federation of labor unions in the United States that continues today as the AFL-CIO. It was founded in Columbus, Ohio, in 1886 by an alliance of craft unions eager to provide mutual ...

(AFL). Rather than open its membership to all, the AFL, under former cigar-makers union official Samuel Gompers

Samuel Gompers (; January 27, 1850December 11, 1924) was a British-born American cigar maker, labor union leader and a key figure in American labor history. Gompers founded the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and served as the organization's ...

, focused on skilled workers. His objectives were "pure and simple": increasing wages, reducing hours, and improving working conditions. As such, Gompers helped turn the labor movement away from the socialist

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

views earlier labor leaders had espoused. The AFL would gradually become a respected organization in the U.S., although it would have nothing to do with unskilled laborers.

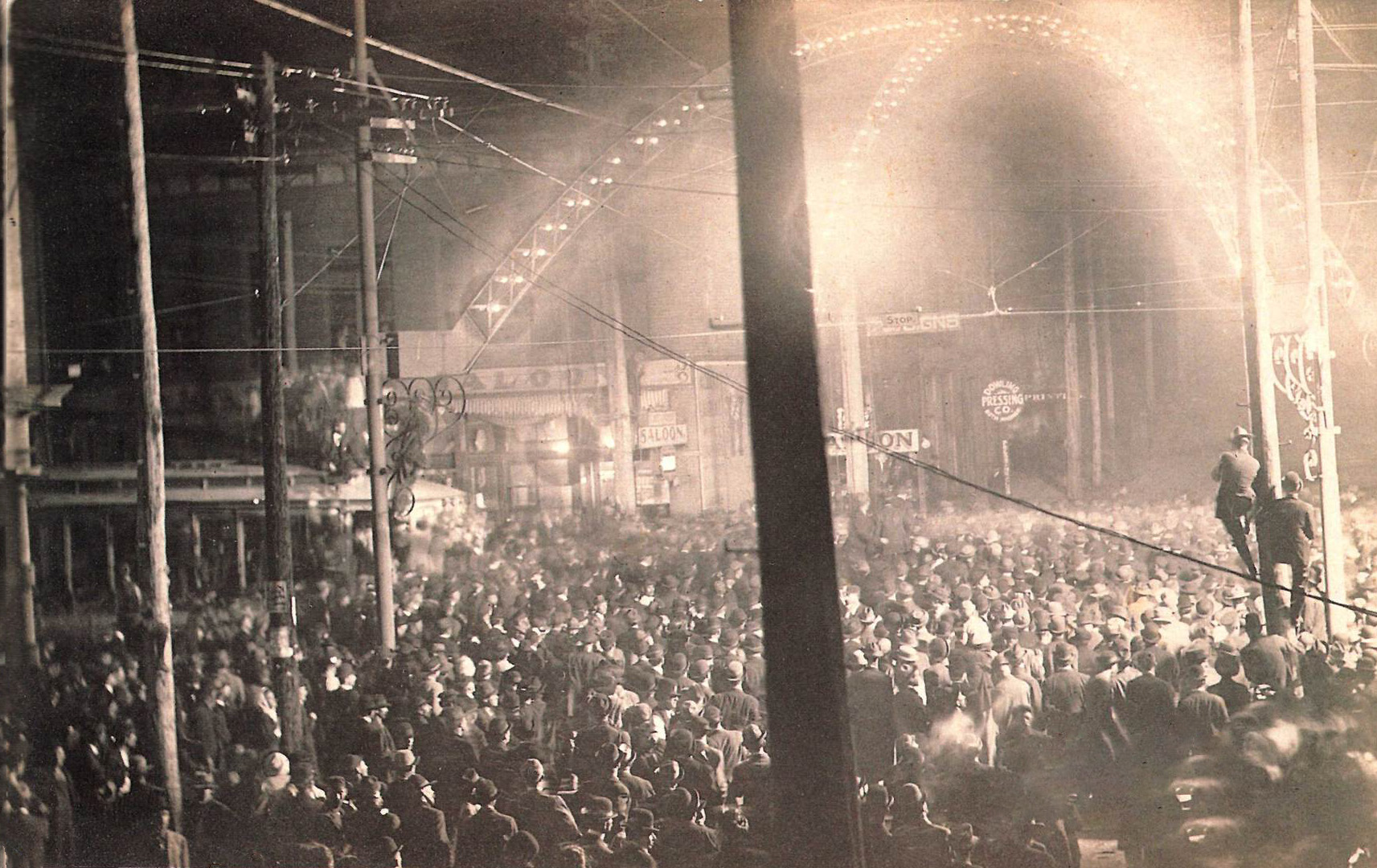

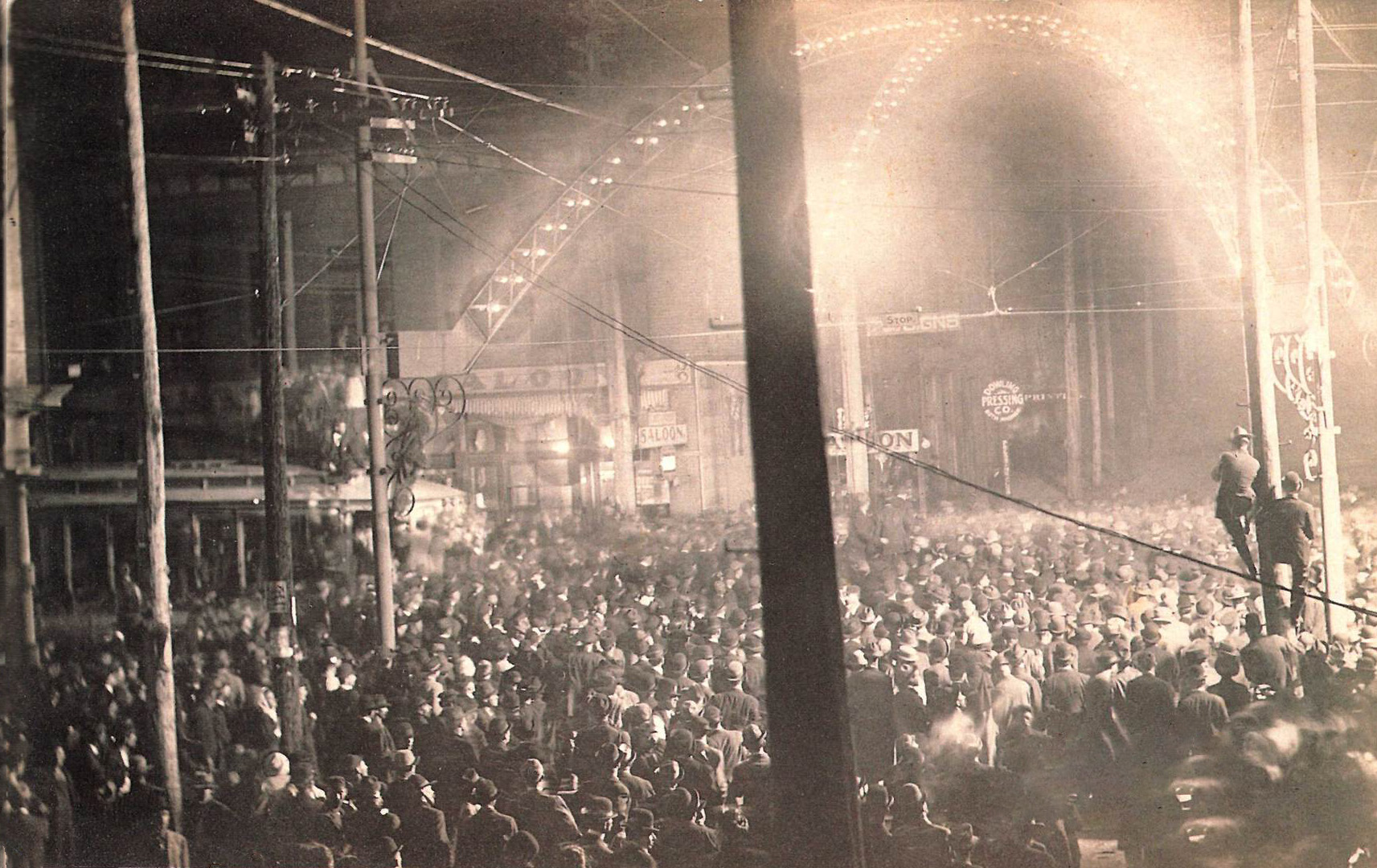

In times of economic depression, layoffs and wage cuts angered workers, leading to violent labor conflicts in 1877 and 1894. In the Great Railroad Strike in 1877, railroad workers across the nation went on strike in response to a 10-percent pay cut. Attempts to break the strike led to bloody uprisings in several cities. The Haymarket Riot

The Haymarket affair, also known as the Haymarket massacre, the Haymarket riot, the Haymarket Square riot, or the Haymarket Incident, was the aftermath of a bombing that took place at a labor demonstration on May 4, 1886 at Haymarket Square i ...

took place in 1886, when an anarchist allegedly threw a bomb that killed several police dispersing a strike rally at the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company

The International Harvester Company (often abbreviated IH or International) was an American manufacturer of agricultural and construction equipment, automobiles, commercial trucks, lawn and garden products, household equipment, and more. It wa ...

in Chicago. Anarchists were arrested and convicted, weakening the movement.

In commemoration of the Haymarket Riots, May 1 would be acknowledged by socialist and communist movements worldwide as International Workers' Day, Labor Day, or May Day, and became an official holiday in many countries. In 1893, President Cleveland signed into law a bill making Labor Day an official US holiday, but on the first weekend of September to avoid the socialistic connotations of May Day.

At its peak, the Knights claimed 700,000 members. By 1890, membership had plummeted to fewer than 100,000, then faded away. The killing of policemen greatly embarrassed the Knights of Labor, which was not involved with the bomb but which took much of the blame.

In the riots

A riot or mob violence is a form of civil disorder commonly characterized by a group lashing out in a violent public disturbance against authority, property, or people.

Riots typically involve destruction of property, public or private. The p ...

of 1892 at Carnegie's steel works in Homestead, Pennsylvania

Homestead is a borough in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, United States, along the Monongahela River southeast of downtown Pittsburgh. The borough is known for the Homestead strike of 1892, an important event in the history of labor relation ...

, a group of 300 Pinkerton detectives, whom the company had hired to break a bitter strike by the Amalgamated Association of Iron, Steel and Tin Workers, were fired upon by strikers and 10 were killed. As a result, the National Guard

National guard is the name used by a wide variety of current and historical uniformed organizations in different countries. The original National Guard was formed during the French Revolution around a cadre of defectors from the French Guards.

...

was called in to guard the plant; non-union workers were hired and the strike broken. The Homestead plant completely barred unions until 1937.

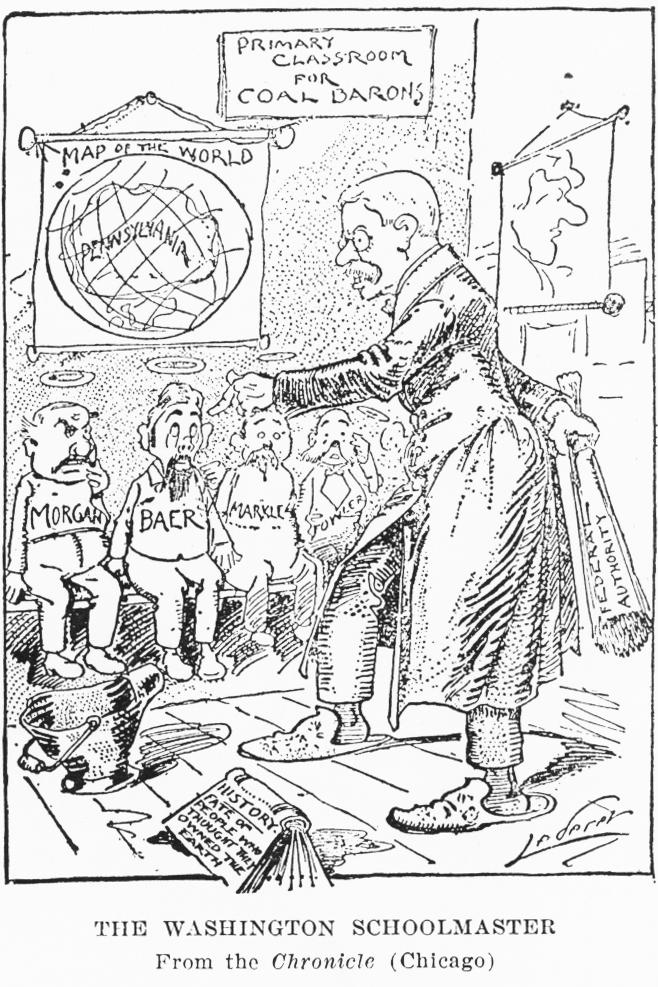

Two years later, wage cuts at the Pullman Palace Car Company, just outside Chicago, led to a strike, which, with the support of the American Railway Union

The American Railway Union (ARU) was briefly among the largest labor unions of its time and one of the first Industrial unionism, industrial unions in the United States. Launched at a meeting held in Chicago in February 1893, the ARU won an early ...

, soon brought the nation's railway industry to a halt. The shutdown of rail traffic meant the virtual shutdown of the entire national economy, and President Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was the 22nd and 24th president of the United States, serving from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. He was the first U.S. president to serve nonconsecutive terms and the first Hist ...

acted vigorously. He secured injunctions in federal court, which Eugene Debs

Eugene Victor Debs (November 5, 1855 – October 20, 1926) was an American socialist, political activist, trade unionist, one of the founding members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), and five-time candidate of the Socialist Party o ...

and the other strike leaders ignored. Cleveland then sent in the Army to stop the rioting and get the trains moving. The strike collapsed, as did the ARU, and Debs, a once middle-of-the-road social reformer, converted to a full-blown socialist while serving a sentence in Federal prison for defying a court order to cease striking.

The most militant working class organization of the 1905–1920 era was the

The most militant working class organization of the 1905–1920 era was the Industrial Workers of the World

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), whose members are nicknamed "Wobblies", is an international labor union founded in Chicago, United States in 1905. The nickname's origin is uncertain. Its ideology combines general unionism with indu ...

(IWW), formed largely in response to abysmal labor conditions (in 1904, the year before its founding, 27,000 workers were killed on the job) and discrimination against women, minorities, and unskilled laborers by other unions, particularly the AFL. The "Wobblies," as they were commonly known, gained particular prominence from their incendiary and revolutionary rhetoric. Openly calling for class warfare

''Class Warfare'' is a book of collected interviews with Noam Chomsky conducted by David Barsamian. It was first published in the United States by Common Courage Press, and in the United Kingdom by Pluto Press, in 1996.

Publishing history

The ...

, direct action

Direct action is a term for economic and political behavior in which participants use agency—for example economic or physical power—to achieve their goals. The aim of direct action is to either obstruct a certain practice (such as a governm ...

, workplace democracy

Workplace democracy is the application of democracy in various forms to the workplace, such as voting systems, consensus, debates, democratic structuring, due process, adversarial process, and systems of appeal. It can be implemented in a ...

and " One Big Union" for all workers regardless of sex, race or skills, the Wobblies gained many adherents after they won a difficult 1912 textile strike (commonly known as the "Bread and Roses

"Bread and Roses" is a political slogan associated with women's suffrage and the labor movement, as well as an associated poem and song. It originated in a speech given by American women's suffrage activist Helen Todd; a line in that speech ab ...

" strike) in Lawrence, Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

. They proved ineffective in managing peaceful labor relations and members dropped away, primarily because the union failed to build long-term worker organizations even after a successful campaign, leaving the workers involved at the mercy of employers once the IWW had moved on. However, this was not fatal to the union. That the IWW directly challenged capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

via direct action at the point of production prompted swift and decisive action from the state, especially during and after World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. According to historian Howard Zinn

Howard Zinn (August 24, 1922January 27, 2010) was an American historian and a veteran of World War II. He was chair of the history and social sciences department at Spelman College, and a political science professor at Boston University. Zinn ...

, "the IWW became a threat to the capitalist class, exactly when capitalist growth was enormous and profits huge." The IWW strongly opposed the 1917–18 war effort and faced a campaign of repression from the federal government. More than a few Wobblies, such as Frank Little, were beaten or lynched by mobs or died in American jails.

Gilded Age

The "Gilded Age" that was enjoyed by the topmost percentiles of American society after the recovery from thePanic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 was a financial crisis that triggered an economic depression in Europe and North America that lasted from 1873 to 1877 or 1879 in France and in Britain. In Britain, the Panic started two decades of stagnation known as the "L ...

floated on the surface of the newly industrialized economy of the Second Industrial Revolution. It was further fueled by a period of wealth transfer that catalyzed dramatic social changes. It created for the first time a class of the super-rich "captains of industry", the " robber barons" whose network of business, social and family connections ruled a largely White Anglo-Saxon Protestant

In the United States, White Anglo-Saxon Protestants or Wealthy Anglo-Saxon Protestants (WASP) is a Sociology, sociological term which is often used to describe White Americans, white Protestantism in the United States, Protestant Americans of E ...

social world that possessed clearly defined boundaries. The term ''Gilded Age'' for this era was adopted by 1920s historians who took it from Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910), known by the pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, and essayist. He was praised as the "greatest humorist the United States has produced," with William Fau ...

and Charles Dudley Warner

Charles Dudley Warner (September 12, 1829 – October 20, 1900) was an American essayist, novelist, and friend of Mark Twain, with whom he co-authored the novel '' The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today''.

Biography

Warner was born of Puritan descen ...

's 1873 book, '' The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today'', which pointed out the ironic difference between a "gilded" and a Golden Age

The term Golden Age comes from Greek mythology, particularly the ''Works and Days'' of Hesiod, and is part of the description of temporal decline of the state of peoples through five Ages of Man, Ages, Gold being the first and the one during wh ...

.

Politically, the Republican Party was in ascendancy and would largely remain so until the 1930s with brief interruptions. The Civil War had collapsed the Democrats' national machine and given the GOP the chance to entrench its own national machine that held for 70 years. Republicans fully took credit for winning the war and abolishing slavery, and were firmly established as the party of big business, the gold standard, and economic protectionism. Republican voter strength came mostly out of the small and medium sized towns and rural areas of the Northeast and Midwest, as well as the majority of Union army veterans—the Grand Army of the Republic, a veterans' fraternal organization that wielded huge political power in the 1880s-1890s, was also referred to as "Generally All Republicans." The addition of new states in the West gave the GOP still more national strength.

Democrats in the North were mostly an urban party that relied on immigrant laborers for a base, however in the Gilded Age there was not a major ideological gap between the two parties outside tariffs versus free trade. In the South, the end of Reconstruction quickly established the Democrat Party's absolute rule over the region that held for a century. Only small pockets of Republican support existed in the South once black voter suppression was complete by the 1890s—usually these consisted of counties that had not supported secession during the war. German-Americans provided a small but stable Republican presence in a few areas of Texas and Eastern Tennessee remained a largely Republican area.

Nonetheless, national elections in the Gilded Age were close, contentious, and attracted a lot of energy and voter enthusiasm. This began to change after William McKinley's victory in 1896. For 17 years afterward, the country came close to a one party Republican state and there were periods when Democrats were nearly reduced to a regional Southern party. Voter turnout and enthusiasm sharply fell off.

With the end of Reconstruction, there were few major political issues at stake and the 1880 presidential election was the quietest in a long time. James Garfield

James Abram Garfield (November 19, 1831 – September 19, 1881) was the 20th president of the United States, serving from March 1881 until Assassination of James A. Garfield, his death in September that year after being shot two months ea ...

, the Republican candidate, won a very close election, but a few months into his administration was shot by a disgruntled public office seeker. Garfield was succeeded by Vice President Chester Arthur

Chester Alan Arthur (October 5, 1829 – November 18, 1886) was the 21st president of the United States, serving from 1881 to 1885. He was a Republican from New York who previously served as the 20th vice president under President James A. ...

.

Reformers, especially the "Mugwump

The Mugwumps were History of the Republican Party (United States), Republican political activists in the United States who were intensely opposed to political corruption. They were never formally organized. They famously Party switching, swit ...

s" complained that powerful parties made for corruption during the Gilded Age or "Third Party System

The Third Party System was a period in the history of political parties in the United States from the 1850s until the 1890s, which featured profound developments in issues of American nationalism, modernization, and race. This period was marke ...

". Voter enthusiasm and turnout during the period 1872–1892 was very high, often reaching practically all men. The major issues involved modernization, money, railroads, corruption, and prohibition. National elections, and many state elections, were very close. The 1884 presidential election saw a mudslinging campaign in which Republican James G. Blaine

James Gillespie Blaine (January 31, 1830January 27, 1893) was an American statesman and Republican politician who represented Maine in the United States House of Representatives from 1863 to 1876, serving as speaker of the U.S. House of Rep ...

was defeated by Democrat Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was the 22nd and 24th president of the United States, serving from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. He was the first U.S. president to serve nonconsecutive terms and the first Hist ...

, a reformer. During Cleveland's presidency, he pushed to have Congress cut tariff duties. He also expanded civil services and vetoed many private pension bills. Many people were worried that these issues would hurt his chances in the 1888 election. When they expressed these concerns to Cleveland, he said "What is the use of being elected or reelected, unless you stand for something?" As was typical of the age, Cleveland took a conservative, constrained view of the Constitution and Federal powers. When the Texas port of Indianola was flattened by a devastating 1886 hurricane, he declined to give Federal relief funds for the town as he believed the Constitution did not grant him any such authority. "Although the people should support the government, the government should not support the people," Cleveland said.

The dominant social class of the Northeast possessed the confidence to proclaim an "American Renaissance

The American Renaissance was a period of American architecture and the arts from 1876 to 1917, characterized by renewed national self-confidence and a feeling that the United States was the heir to Greek democracy, Roman law, and Renaissance hu ...

", which could be identified in the rush of new public institutions that marked the period—hospitals, museums, colleges, opera houses, libraries, orchestras— and by the Beaux-Arts architectural idiom in which they splendidly stood forth, after Chicago hosted the World's Columbian Exposition

The World's Columbian Exposition, also known as the Chicago World's Fair, was a world's fair held in Chicago from May 5 to October 31, 1893, to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus's arrival in the New World in 1492. The ...

of 1893.

Social history

Urbanization

Urbanization (or urbanisation in British English) is the population shift from Rural area, rural to urban areas, the corresponding decrease in the proportion of people living in rural areas, and the ways in which societies adapt to this change. ...

(the rapid growth of cities) went hand in hand with industrialization (the growth of factories and railroads), as well as expansion of farming. The rapid growth was made possible by high levels of immigration.

Immigration

From 1865 through 1918 an unprecedented and diverse stream of immigrants arrived in the United States, 27.5 million in total. In all, 24.4 million (89%) came from Europe, including 2.9 million from

From 1865 through 1918 an unprecedented and diverse stream of immigrants arrived in the United States, 27.5 million in total. In all, 24.4 million (89%) came from Europe, including 2.9 million from Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

, 2.2 million from Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

, 2.1 million from Scandinavia

Scandinavia is a subregion#Europe, subregion of northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. It can sometimes also ...

, 3.8 million from Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

, 4.1 million from Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

, 7.8 million from Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

and other parts of Central and Eastern Europe

Central and Eastern Europe is a geopolitical term encompassing the countries in Baltic region, Northeast Europe (primarily the Baltic states, Baltics), Central Europe (primarily the Visegrád Group), Eastern Europe, and Southeast Europe (primaril ...

. Another 1.7 million came from Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

. Most came through the port of New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

, and from 1892, through the immigration station on Ellis Island

Ellis Island is an island in New York Harbor, within the U.S. states of New Jersey and New York (state), New York. Owned by the U.S. government, Ellis Island was once the busiest immigrant inspection and processing station in the United State ...

, but various ethnic groups settled in different locations. New York and other large cities of the East Coast became home to large Jewish, Irish, and Italian populations, while many Germans and Central Europe

Central Europe is a geographical region of Europe between Eastern Europe, Eastern, Southern Europe, Southern, Western Europe, Western and Northern Europe, Northern Europe. Central Europe is known for its cultural diversity; however, countries in ...

ans moved to the Midwest