History Of The United States (1815–1849) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of the United States from 1815 to 1849—also called the Middle Period, the Antebellum Era, or the Age of Jackson—involved westward expansion across the American continent, the proliferation of suffrage to nearly all white men, and the rise of the

Monroe was re-elected without opposition in 1820, and the old caucus system for selecting Republican candidates soon collapsed into factions. In the presidential election of 1824, factions in Tennessee and Pennsylvania put forth

Monroe was re-elected without opposition in 1820, and the old caucus system for selecting Republican candidates soon collapsed into factions. In the presidential election of 1824, factions in Tennessee and Pennsylvania put forth

The charismatic Andrew Jackson collaborated with

The charismatic Andrew Jackson collaborated with

Starting in the 1820s, American politics became more democratic as many state and local offices went from being appointed to elective, and the old requirements for voters to own property were abolished. Voice voting in states gave way to ballots printed by the parties, and by the 1830s, presidential electors were chosen directly by the voters in all states except South Carolina.

Starting in the 1820s, American politics became more democratic as many state and local offices went from being appointed to elective, and the old requirements for voters to own property were abolished. Voice voting in states gave way to ballots printed by the parties, and by the 1830s, presidential electors were chosen directly by the voters in all states except South Carolina.

Toward the end of his first term, Jackson was forced to confront the state of South Carolina on the issue of the protective

Toward the end of his first term, Jackson was forced to confront the state of South Carolina on the issue of the protective

Even before the nullification issue had been settled, another controversy arose to challenge Jackson's leadership. It concerned the rechartering of the

Even before the nullification issue had been settled, another controversy arose to challenge Jackson's leadership. It concerned the rechartering of the

White abolitionists did not always face agreeable communities in the North. Garrison was almost lynched in Boston while newspaper publisher

White abolitionists did not always face agreeable communities in the North. Garrison was almost lynched in Boston while newspaper publisher

After 1815, the United States shifted its attention away from foreign policy to internal development. With the defeat of the eastern Indians in the War of 1812, American settlers moved in great numbers into the rich farmlands of the Midwest. Westward expansion was mostly undertaken by groups of young families.

After 1815, the United States shifted its attention away from foreign policy to internal development. With the defeat of the eastern Indians in the War of 1812, American settlers moved in great numbers into the rich farmlands of the Midwest. Westward expansion was mostly undertaken by groups of young families.

After a bitter debate in Congress the Republic of Texas was voluntarily annexed in 1845, which Mexico had repeatedly warned meant war. In May 1846, Congress declared war on Mexico after Mexican troops massacred a U.S. Army detachment in a disputed unsettled area. However the homefront was polarized as Whigs opposed and Democrats supported the war. The U.S. Army, augmented by tens of thousands of volunteers, commanded by General

After a bitter debate in Congress the Republic of Texas was voluntarily annexed in 1845, which Mexico had repeatedly warned meant war. In May 1846, Congress declared war on Mexico after Mexican troops massacred a U.S. Army detachment in a disputed unsettled area. However the homefront was polarized as Whigs opposed and Democrats supported the war. The U.S. Army, augmented by tens of thousands of volunteers, commanded by General

File:USA population distribution 1820.png, 1820

excerpt

* Cooke, Stuart Tipton. "Jacksonian Era American History Textbooks" (PhD Dissertation, University of Denver. Proquest Dissertations Publishing, 1986. 8612840. * Estes, Todd. "Beyond Whigs and Democrats: historians, historiography, and the paths toward a new synthesis for the Jacksonian era." ''American Nineteenth Century History'' 21.3 (2020): 255–281. * Lynn, Joshua A., and Harry L. Watson. "Introduction: Race, Politics, and Culture in the Age of Jacksonian 'Democracy'." ''Journal of the Early Republic'' 39.1 (2019): 81–87

excerpt

*

at Thayer's American History site

{{DEFAULTSORT:History of the United States (1815-1849) 1810s in the United States 1820s in the United States 1830s in the United States 1840s in the United States History of the United States by period

Second Party System

The Second Party System was the Political parties in the United States, political party system operating in the United States from about 1828 to early 1854, after the First Party System ended. The system was characterized by rapidly rising leve ...

of politics between Democrats and Whigs. Whigs—representing merchants, financiers, professionals, and a growing middle class—wanted to modernize society, using tariffs and federally funded internal improvements

Internal improvements is the term used historically in the United States for public works from the end of the American Revolution through much of the 19th century, mainly for the creation of a transportation infrastructure: roads, turnpikes, can ...

; Jacksonian Democrats opposed them and closed down the national bank in the 1830s. The Jacksonians favored expansion across the continent, known as manifest destiny

Manifest destiny was the belief in the 19th century in the United States, 19th-century United States that American pioneer, American settlers were destined to expand westward across North America, and that this belief was both obvious ("''m ...

, dispossessing American Indians of lands to be occupied by farmers, planters, and slaveholders. Thanks to the annexation of Texas

Texas ( , ; or ) is the most populous U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, New Mexico to the we ...

, the defeat of Mexico in war, and a compromise with Britain, the western third of the nation rounded out the continental United States by 1848.

The transformation America underwent was not so much political democratization but rather the explosive growth of technologies and networks of infrastructure and communication, including with the telegraph, railroads, the post office, and an expanding print industry. These developments made possible the religious revivals of the Second Great Awakening

The Second Great Awakening was a Protestant religious revival during the late 18th to early 19th century in the United States. It spread religion through revivals and emotional preaching and sparked a number of reform movements. Revivals were a k ...

, the expansion of education, and social reform. They modernized party politics and sped up business by enabling the fast, efficient movement of goods, money, and people across an expanding nation. They transformed a loose-knit collection of parochial agricultural communities into a powerful cosmopolitan nation. Economic modernization proceeded rapidly, thanks to highly profitable cotton crops in the South, new textile and machine-making industries in the Northeast, and a fast developing transportation infrastructure.

Breaking loose from European models, the Americans developed their own high culture, notably in literature and in higher education. The Second Great Awakening

The Second Great Awakening was a Protestant religious revival during the late 18th to early 19th century in the United States. It spread religion through revivals and emotional preaching and sparked a number of reform movements. Revivals were a k ...

brought revivals across the country, forming new denominations and greatly increasing church membership, especially among Methodists and Baptists

Baptists are a Christian denomination, denomination within Protestant Christianity distinguished by baptizing only professing Christian believers (believer's baptism) and doing so by complete Immersion baptism, immersion. Baptist churches ge ...

. By the 1840s, increasing numbers of immigrants were arriving from Europe, especially British, Irish, and Germans. Many settled in the cities, which were starting to emerge as a major factor in the economy and society. The Whigs had warned that annexation of Texas would lead to a crisis over slavery, and they were proven right by the turmoil of the 1850s that led to the Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

.

Names

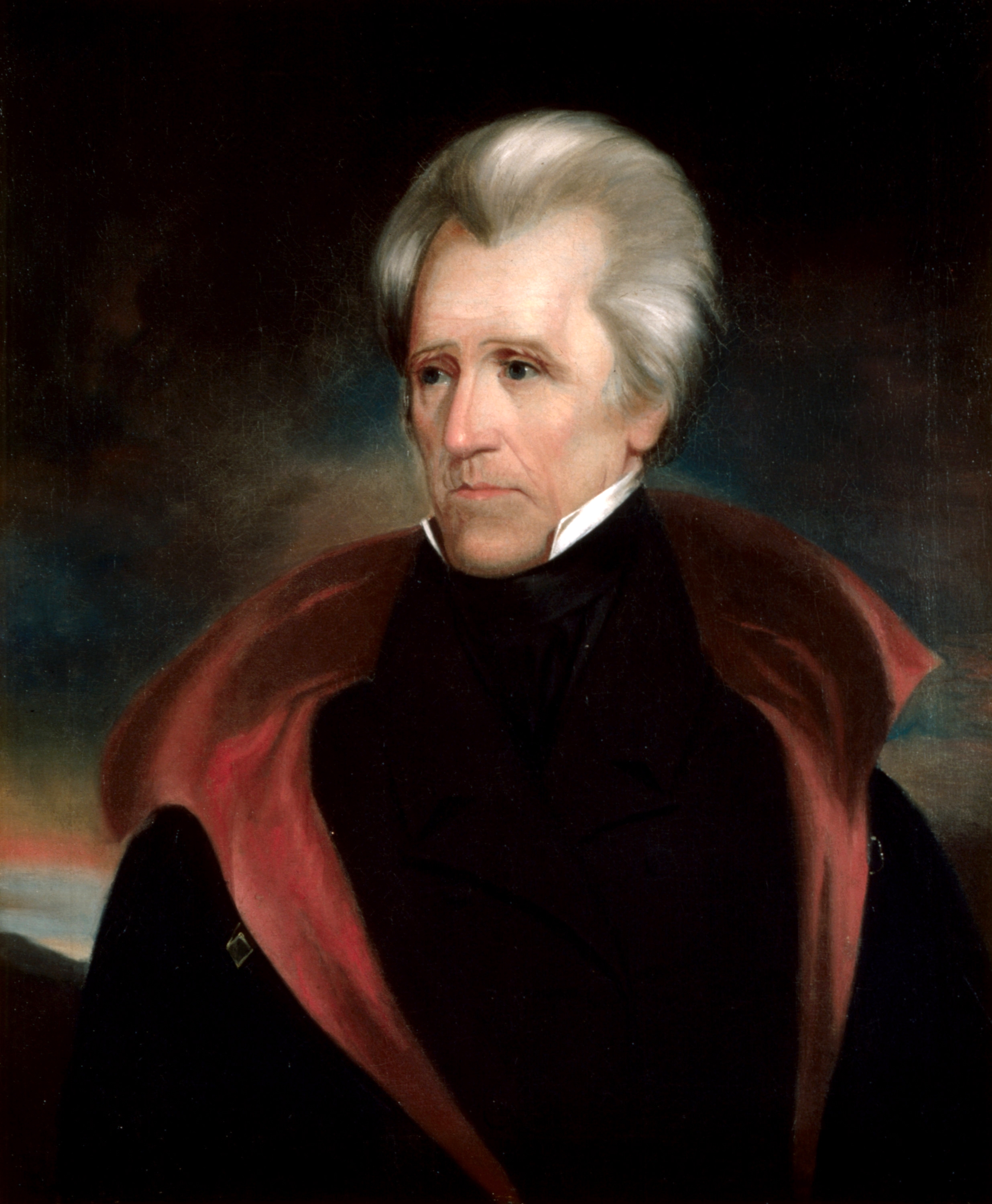

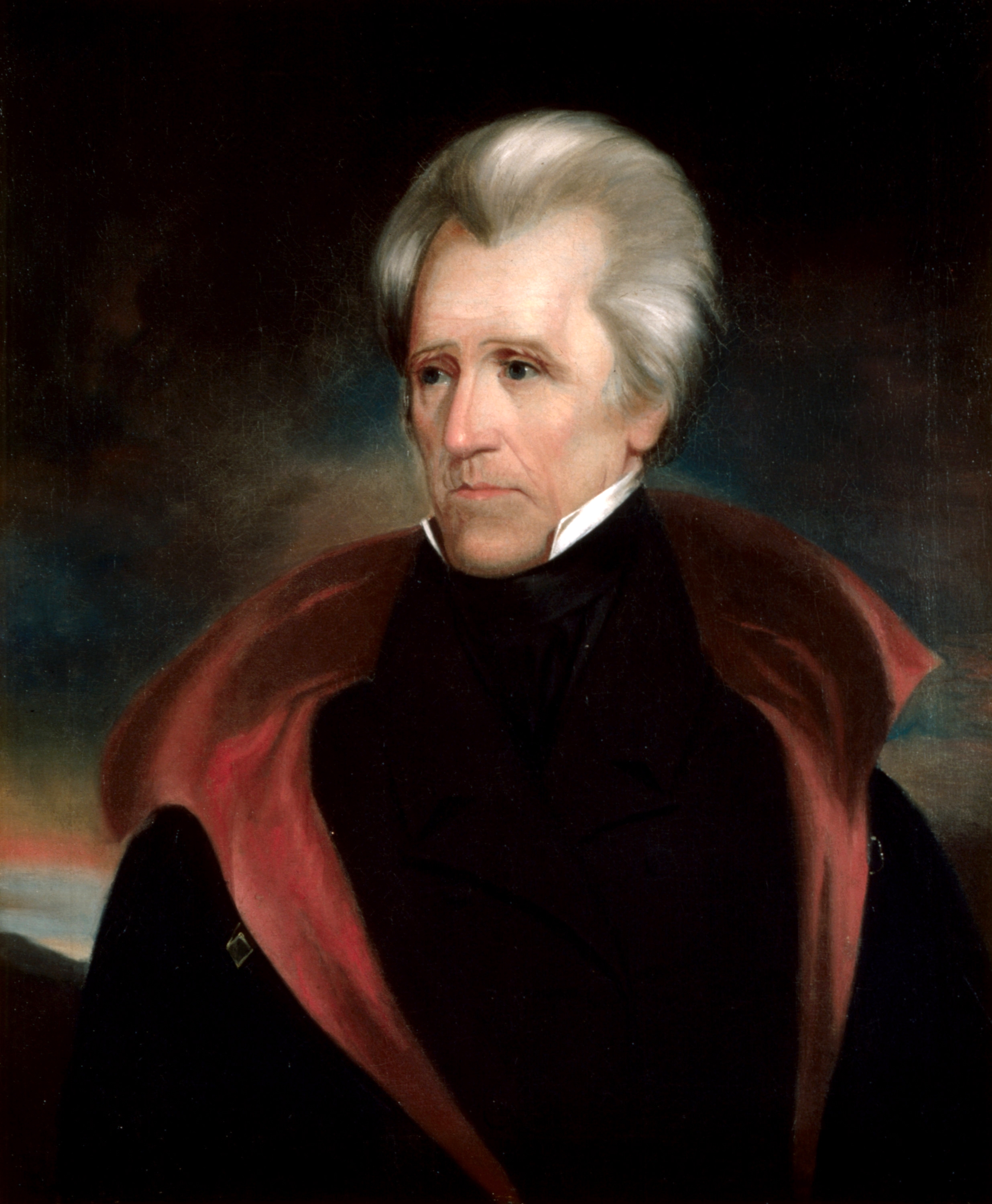

Historians of the United States have referred to this approximate period in American history using various names. It has been called the ''Middle Period''. According to Trevor Burnard in 2011, the era "used to be called the Middle Period". This span of years has also been called the ''Antebellum Era'' or ''Antebellum Period''. The word ''antebellum'' comes from the Latin ''ante bellum'', meaning "before the war", and the age preceded the Civil War era. Another name for the time period has been the ''Age of Jackson'' or ''Jacksonian era'', named after American presidentAndrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before Presidency of Andrew Jackson, his presidency, he rose to fame as a general in the U.S. Army and served in both houses ...

, said to have defined the era as a time when popular democracy

Popular democracy is a notion of direct democracy based on referendums and other devices of empowerment and concretization of popular will. The concept evolved out of the political philosophy of populism, as a fully democratic version of this p ...

became the United States' norm and ideal. Historian Daniel Walker Howe criticized this name, arguing that although Jackson used democratic rhetoric, his presidency was authoritarian and did not broadly represent the country.

Era of Good Feelings and the rise of nationalism

After theWar of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

, the United States began to assert a newfound sense of nationalism. America began to rally around national heroes like Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before Presidency of Andrew Jackson, his presidency, he rose to fame as a general in the U.S. Army and served in both houses ...

. Patriotic feelings were aroused by Francis Scott Key

Francis Scott Key (August 1, 1779January 11, 1843) was an American lawyer, author, and poet from Frederick, Maryland, best known as the author of the poem "Defence of Fort M'Henry" which was set to a popular British tune and eventually became t ...

's poem ''The Star-Spangled Banner

"The Star-Spangled Banner" is the national anthem of the United States. The lyrics come from the "Defence of Fort M'Henry", a poem written by American lawyer Francis Scott Key on September 14, 1814, after he witnessed the bombardment of Fort ...

''. Under the direction of Chief Justice John Marshall

John Marshall (September 24, 1755July 6, 1835) was an American statesman, jurist, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the fourth chief justice of the United States from 1801 until his death in 1835. He remai ...

, the Supreme Court

In most legal jurisdictions, a supreme court, also known as a court of last resort, apex court, high (or final) court of appeal, and court of final appeal, is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

issued a series of opinions reinforcing the role of the national government. These decisions included ''McCulloch v. Maryland

''McCulloch v. Maryland'', 17 U.S. (4 Wheat.) 316 (1819), was a landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision that defined the scope of the U.S. Congress's legislative power and how it relates to the powers of American state legislatures. The dispute in ...

'' and ''Gibbons v. Ogden

''Gibbons v. Ogden'', 22 U.S. (9 Wheat.) 1 (1824), was a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States which held that the power to regulate interstate commerce, which is granted to the US Congress by the Commerce Clause of the US ...

'', both of which reaffirmed the supremacy of the national government over the states. The signing of the Adams–Onís Treaty

The Adams–Onís Treaty () of 1819, also known as the Transcontinental Treaty, the Spanish Cession, the Florida Purchase Treaty, or the Florida Treaty,Weeks, p. 168. was a treaty between the United States and Spain in 1819 that ceded Florida to ...

helped settle the western border of the country through popular and peaceable means.

Sectionalism

Even asnationalism

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation, Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Theory, I ...

increased across the country, its effects were limited by a renewed sense of sectionalism

Sectionalism is loyalty to one's own region or section of the country, rather than to the country as a whole.

Sectionalism occurs in many countries, such as in the United Kingdom.

In the United Kingdom

Sectionalism occurs most notably in the co ...

. The New England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

states that had opposed the War of 1812 felt an increasing decline in political power with the demise of the Federalist Party

The Federalist Party was a conservativeMultiple sources:

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

* and nationalist American political party and the first political party in the United States. It dominated the national government under Alexander Hamilton from 17 ...

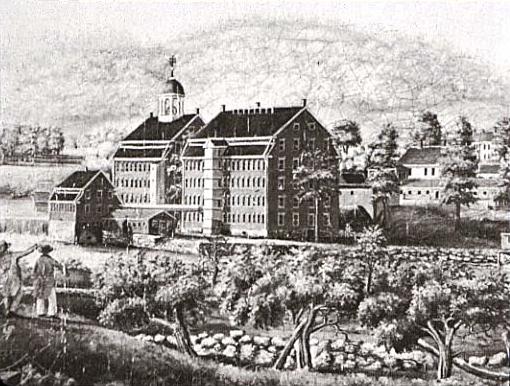

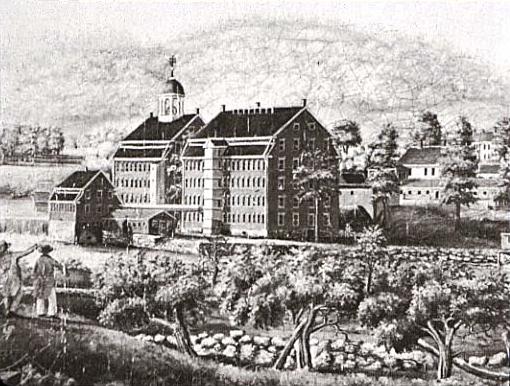

. This loss was tempered with the arrival of a new industrial movement and increased demands for northern banking. The Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, sometimes divided into the First Industrial Revolution and Second Industrial Revolution, was a transitional period of the global economy toward more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes, succee ...

in the United States was advanced by the immigration of Samuel Slater

Samuel Slater (June 9, 1768 – April 21, 1835) was an early English-American industrialist known as the "Father of the American Industrial Revolution", a phrase coined by Andrew Jackson, and the "Father of the American Factory System". In the ...

from Great Britain and arrival of textile mills beginning in Lowell, Massachusetts

Lowell () is a city in Massachusetts, United States. Alongside Cambridge, Massachusetts, Cambridge, it is one of two traditional county seat, seats of Middlesex County, Massachusetts, Middlesex County. With an estimated population of 115,554 in ...

. In the south, the invention of the cotton gin

A cotton gin—meaning "cotton engine"—is a machine that quickly and easily separates cotton fibers from their seeds, enabling much greater productivity than manual cotton separation.. Reprinted by McGraw-Hill, New York and London, 1926 (); ...

by Eli Whitney

Eli Whitney Jr. (December 8, 1765January 8, 1825) was an American inventor, widely known for inventing the cotton gin in 1793, one of the key inventions of the Industrial Revolution that shaped the economy of the Antebellum South.

Whitney's ...

radically increased the value of slave labor. The export of southern cotton was now the predominant export of the U.S. The western states continued to thrive under the "frontier spirit." Individualism was prized as exemplified by Davey Crockett

Colonel David Crockett (August 17, 1786 – March 6, 1836) was an American politician, militia officer and frontiersman. Often referred to in popular culture as the "King of the Wild Frontier", he represented Tennessee in the United States Ho ...

and James Fenimore Cooper

James Fenimore Cooper (September 15, 1789 – September 14, 1851) was an American writer of the first half of the 19th century, whose historical romances depicting colonial and indigenous characters from the 17th to the 19th centuries brought h ...

's folk hero Natty Bumppo

Nathaniel "Natty" Bumppo is a fictional character and the protagonist of James Fenimore Cooper's pentalogy of novels known as the ''Leatherstocking Tales''. He appears throughout the series as an archetypal American ranger, and has been portrayed ...

from ''Leatherstocking Tales

The ''Leatherstocking Tales'' is a series of five novels ('' The Deerslayer'', ''The Last of the Mohicans'', '' The Pathfinder'', '' The Pioneers'', and '' The Prairie'') by American writer James Fenimore Cooper, set in the eighteenth-centur ...

''. Following the death of Tecumseh

Tecumseh ( ; (March 9, 1768October 5, 1813) was a Shawnee chief and warrior who promoted resistance to the Territorial evolution of the United States, expansion of the United States onto Native Americans in the United States, Native American ...

in 1813, Native Americans lacked the unity to stop white settlement.

Era of Good Feelings

Domestically, thepresidency of James Monroe

James Monroe's tenure as the fifth president of the United States began on March 4, 1817, and ended on March 4, 1825. Monroe, a member of the Democratic-Republican Party, took office after winning the 1816 presidential election by in a landslide ...

(1817–1825) was hailed at the time and since as the "Era of Good Feelings" because of the decline of partisan politics and heated rhetoric after the war. The Federalist Party collapsed, but without an opponent the Democratic-Republican Party

The Democratic-Republican Party (also referred to by historians as the Republican Party or the Jeffersonian Republican Party), was an American political party founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the early 1790s. It championed li ...

decayed as sectional interests came to the fore.

The Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine is a foreign policy of the United States, United States foreign policy position that opposes European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It holds that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign ...

was drafted by Secretary of State John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was the sixth president of the United States, serving from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States secretary of state from 1817 to 1825. During his long diploma ...

in collaboration with the British, and proclaimed by Monroe in late 1823. He asserted the Americas should be free from additional European colonization and free from European interference in sovereign countries' affairs. It further stated the United States' intention to stay neutral in wars between European powers and their colonies but to consider any new colonies or interference with independent countries in the Americas as hostile acts towards the United States. No new colonies were ever formed.

Annexation of Florida and border treaties

As the 19th century dawned, Florida had been undisputed Spanish territory for almost 250 years, aside from 20 years of British control between the French and Indian Wars and the American Revolution. Although a sparsely inhabited swampland, expansionist-minded Americans were eager to grab it and already, in 1808, American settlers had invaded the westernmost tip of Florida and expelled the local Spanish authorities, after which Congress hastily passed a bill annexing it under the claim that the Louisiana Purchase had guaranteed the territory to the United States. During the War of 1812, American troops occupied and seized the area around Mobile Bay. Spain, then engulfed in war with France, did not react to either of these actions. Also taking advantage of the mother country's distraction, Spain's Latin American colonies rose up in revolt and Madrid was forced to denude Florida of troops to suppress the rebellions. As the Spanish withdrew, Native American and pirate raids from Florida to the US increased. In 1818, Andrew Jackson led an army into Florida to quell the chaotic situation there. He arrested and hanged two British agents who had been encouraging Indian raids, leading to an outcry in London and calls for war. However, cooler heads prevailed and the situation did not escalate further. A year later, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams negotiated theAdams–Onís Treaty

The Adams–Onís Treaty () of 1819, also known as the Transcontinental Treaty, the Spanish Cession, the Florida Purchase Treaty, or the Florida Treaty,Weeks, p. 168. was a treaty between the United States and Spain in 1819 that ceded Florida to ...

with Spain. The Spanish agreed to turn over the no-longer-defensible Florida to the US and also give up their extremely flimsy claims to the distant Oregon Territory, in exchange for which American claims on Texas were renounced (some Americans had also been claiming parts of that territory under the Louisiana Purchase). The heretofore vague border between the US and Spanish North America was also settled upon. Although American designs on Texas did not disappear, they were put on the backburner for the more immediately important Florida.

Meanwhile, in 1818, the U.S. and Britain also agreed to settle the western border with Canada, which was established at the 49th parallel running straight from the Great Lakes to the Rocky Mountains. Included in this settlement was the headwaters of the Red River in what would eventually become Minnesota, and the Mesabi Range

The Mesabi Iron Range is a mining district and mountain range in northeastern Minnesota following an elongate trend containing large deposits of iron ore. It is the largest of four major iron ranges in the region collectively known as the Iro ...

, which eventually proved to contain vast amounts of iron ore. The eastern border of Canada continued to be disputed and was not settled until 1845.

Emergence of Second Party System

Monroe was re-elected without opposition in 1820, and the old caucus system for selecting Republican candidates soon collapsed into factions. In the presidential election of 1824, factions in Tennessee and Pennsylvania put forth

Monroe was re-elected without opposition in 1820, and the old caucus system for selecting Republican candidates soon collapsed into factions. In the presidential election of 1824, factions in Tennessee and Pennsylvania put forth Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before Presidency of Andrew Jackson, his presidency, he rose to fame as a general in the U.S. Army and served in both houses ...

. From Kentucky came Speaker of the House

The speaker of a deliberative assembly, especially a legislative body, is its presiding officer, or the chair. The title was first used in 1377 in England.

Usage

The title was first recorded in 1377 to describe the role of Thomas de Hung ...

Henry Clay

Henry Clay (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the United States Senate, U.S. Senate and United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives. He was the seventh Spea ...

, while Massachusetts produced Secretary of State Adams; a rump congressional caucus put forward Treasury Secretary William H. Crawford

William Harris Crawford (February 24, 1772 – September 15, 1834) was an American politician who served as U.S. Secretary of War and U.S. Secretary of the Treasury. He later ran for U.S. president in the 1824 United States presidential electi ...

. Personality and sectional allegiance played important roles in determining the outcome of the election. Adams won the electoral votes from New England and most of New York; Clay won his western base of Kentucky, Ohio, and Missouri; Jackson won his base in the Southeast, and plus Illinois, Indiana, North Carolina, South Carolina, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and New Jersey; and Crawford won his base in the South, Virginia, Georgia, and Delaware. No candidate gained a majority in the Electoral College

An electoral college is a body whose task is to elect a candidate to a particular office. It is mostly used in the political context for a constitutional body that appoints the head of state or government, and sometimes the upper parliament ...

, so the president was selected by the House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entities. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often ...

, where Clay was the most influential figure. In return for Clay's support in winning the presidency, John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was the sixth president of the United States, serving from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States secretary of state from 1817 to 1825. During his long diploma ...

appointed Clay as secretary of state in what Jacksonians denounced as a corrupt bargain

In American political jargon, corrupt bargain is a backdoor deal for or involving the U.S. presidency. Three events in particular in American political history have been called the corrupt bargain: the 1824 United States presidential election, ...

.

During Adams' administration, new party alignments appeared. Adams' followers took the name of "National Republicans

The National Republican Party, also known as the Anti-Jacksonian Party or simply Republicans, was a political party in the United States which evolved from a conservative-leaning faction of the Democratic-Republican Party that supported John ...

", to reflect the mainstream of Jeffersonian Republicanism. Elected with less than 35% of the popular vote, Adams was a minority president and his cold, aloof personality did not win many friends. Adams was also a poor politician and alienated potential political allies with his commitment to principles when he refused to remove Federal officeholders and replace them with supporters out of patronage. A strong nationalist, he called for the construction of national road networks and canals and renewed George Washington's call for a national academy. Adams even went so far as to suggest the construction of astronomical observatories to rival those of Europe. These extravagant proposals offended many average Americans. Southerners in particular opposed them because they would require continued heavy tariffs, and they feared government overreach of this type could easily lead to action taken against slavery. Adams had little to boast about in domestic affairs.

Despite his sterling career in foreign affairs, Adams also proved less than successful at foreign policy. His old rival, British Foreign Secretary George Canning

George Canning (; 11 April 17708 August 1827) was a British Tory statesman. He held various senior cabinet positions under numerous prime ministers, including two important terms as foreign secretary, finally becoming Prime Minister of the U ...

, played a cat-and-mouse game with him. Ever since the Treaty of Paris 42 years earlier, Britain had barred American merchantmen from doing business in its islands in the West Indies, although smugglers frequently evaded this ban. When Adams demanded that London open the islands to trade, Canning rejected his request. Another fiasco for the president occurred when the newly independent Latin American republics held a congress in Panama in 1826. Adams requested permission and funding from Congress to send two delegates. Some Congressmen worried about becoming involved in foreign entanglements, while Southerners, sensitive to racial issues, disliked the idea of granting recognition and equal status to the "black" and "mixed" Latin American states. Although Adams was ultimately successful in getting approval, one of the two delegates died en route to Panama and the Panama Congress ultimately accomplished little of value.

Jacksonian democracy

The charismatic Andrew Jackson collaborated with

The charismatic Andrew Jackson collaborated with Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was the eighth president of the United States, serving from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he served as Attorney General o ...

to rally his followers in the newly formed Democratic Party. In the election of 1828, Jackson defeated Adams by an overwhelming electoral majority in the first presidential election since 1800 to mark a wholesale voter rejection of the previous administration's policies. The electoral campaign was correspondingly as vicious as the one 28 years earlier, with Jackson and Adams camps hurtling the worst mudslinging accusations at one another. The former painted himself as a war hero and the champion of the masses against Northeastern elites while the latter argued that he was a man of education and social grace against an uncouth, semi-literate backwoodsman. This belied the fact that Andrew Jackson was a societal elite by any definition, owning a large plantation with dozens of slaves and mostly surrounding himself with men of wealth and property. The election saw the coming to power of Jacksonian democracy, thus marking the transition from the First Party System

The First Party System was the political party system in the United States between roughly 1792 and 1824. It featured two national parties competing for control of the presidency, Congress, and the states: the Federalist Party, created largel ...

(which reflected Jeffersonian democracy

Jeffersonian democracy, named after its advocate Thomas Jefferson, was one of two dominant political outlooks and movements in the United States from the 1790s to the 1820s. The Jeffersonians were deeply committed to American republicanism, wh ...

) to the Second Party System

The Second Party System was the Political parties in the United States, political party system operating in the United States from about 1828 to early 1854, after the First Party System ended. The system was characterized by rapidly rising leve ...

. Historians debate the significance of the election, with many arguing that it marked the beginning of modern American politics, with the decisive establishment of democracy and the formation of the two party system.

When Jackson took office on March 4, 1829, many doubted if he would survive his term in office. A week short of his 63rd birthday, he was the oldest man yet elected president and suffering from the effects of old battle wounds. He also had a frequent hacking cough and sometimes spit up blood. The inauguration ball became a notorious event in the history of the American presidency as a large mob of guests swarmed through the White House, tracking dirt and mud everywhere, and consuming a giant cheese that had been presented as an inaugural gift to the president. A contemporary journalist described the spectacle as "the reign of King Mob".

Suffrage of all white men

Starting in the 1820s, American politics became more democratic as many state and local offices went from being appointed to elective, and the old requirements for voters to own property were abolished. Voice voting in states gave way to ballots printed by the parties, and by the 1830s, presidential electors were chosen directly by the voters in all states except South Carolina.

Starting in the 1820s, American politics became more democratic as many state and local offices went from being appointed to elective, and the old requirements for voters to own property were abolished. Voice voting in states gave way to ballots printed by the parties, and by the 1830s, presidential electors were chosen directly by the voters in all states except South Carolina. Jacksonian democracy

Jacksonian democracy, also known as Jacksonianism, was a 19th-century political ideology in the United States that restructured a number of federal institutions. Originating with the seventh U.S. president, Andrew Jackson and his supporters, i ...

drew its support from the small farmers of the West, and the workers, artisans and small merchants of the East. They favored geographical expansion to create more farms for people like them, and distrusted the upper classes who envisioned an industrial nation built on finance and manufacturing. The entrepreneurs, for whom Henry Clay

Henry Clay (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the United States Senate, U.S. Senate and United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives. He was the seventh Spea ...

and Daniel Webster

Daniel Webster (January 18, 1782 – October 24, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented New Hampshire and Massachusetts in the U.S. Congress and served as the 14th and 19th United States Secretary of State, U.S. secretary o ...

were heroes, fought back and formed the Whig party.

Political machines appeared early in the history of the United States, and for all the exhortations of Jacksonian Democracy, it was they and not the average voter that nominated candidates. In addition, the system supported establishment politicians and party loyalists, and much of the legislation was designed to reward men and businesses who supported a particular party or candidate. As a consequence, the chance of single issue and ideology-based candidates being elected to major office dwindled and so those parties who were successful were pragmatist ones which appealed to multiple constituencies.

Single issue parties included the Anti-Masonic Party

The Anti-Masonic Party was the earliest Third party (United States), third party in the United States. Formally a Single-issue politics, single-issue party, it strongly opposed Freemasonry in the United States. It was active from the late 1820s, ...

, which emerged in the Northeastern states. Its goal was to outlaw Freemasonry

Freemasonry (sometimes spelled Free-Masonry) consists of fraternal groups that trace their origins to the medieval guilds of stonemasons. Freemasonry is the oldest secular fraternity in the world and among the oldest still-existing organizati ...

as a violation of republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology that encompasses a range of ideas from civic virtue, political participation, harms of corruption, positives of mixed constitution, rule of law, and others. Historically, it emphasizes the idea of self ...

; its members were energized by reports that a man who threatened to expose Masonic secrets had been murdered. They ran a candidate for president ( William Wirt) in 1832; he won 8% of the popular vote nationwide, carried Vermont, and ran well in rural Pennsylvania and Massachusetts. The party then merged into the new Whig Party. Others included abolitionist parties, workers' parties like the Workingmen's Party, the Locofocos

The Locofocos (also Loco Focos or Loco-focos) were a faction of the Democratic Party in American politics that existed from 1835 until the mid-1840s.

History

The faction, originally named the Equal Rights Party, was created in New York City as ...

(who opposed monopolies), and assorted nativist parties who denounced the Roman Catholic Church as a threat to republicanism. None of these parties were capable of mounting a broad enough appeal to voters or winning major elections.

The election of 1828 was a significant benchmark, marking the climax of the trend toward broader voter eligibility and participation. Vermont

Vermont () is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Massachusetts to the south, New Hampshire to the east, New York (state), New York to the west, and the Provinces and territories of Ca ...

had universal male suffrage since its entry into the Union, and Tennessee permitted suffrage for the vast majority of taxpayers. New Jersey, Maryland, and South Carolina all abolished property and tax-paying requirements between 1807 and 1810. States entering the Union after 1815 either had universal white male suffrage or a low taxpaying requirement. From 1815 to 1821, Connecticut

Connecticut ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York (state), New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. ...

, Massachusetts and New York abolished all property requirements. In 1824, members of the Electoral College were still selected by six state legislatures. By 1828, presidential electors were chosen by popular vote in every state but Delaware and South Carolina. Nothing dramatized this democratic sentiment more than the election of Andrew Jackson. In addition, the 1828 election marked the decisive emergence of the West as a major political bloc and an end to the dominance of the original 13 states on national affairs.

Indian removal

In 1830, Congress passed theIndian Removal Act

The Indian Removal Act of 1830 was signed into law on May 28, 1830, by United States president Andrew Jackson. The law, as described by Congress, provided "for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or territories, ...

, which authorized the president to negotiate treaties that exchanged Indian tribal lands in the eastern states for lands west of the Mississippi River. In 1834, a special Indian Territory

Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the Federal government of the United States, United States government for the relocation of Native Americans in the United States, ...

was established in what is now the eastern part of Oklahoma

Oklahoma ( ; Choctaw language, Choctaw: , ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Texas to the south and west, Kansas to the north, Missouri to the northea ...

. In all, Native American tribes signed 94 treaties during Jackson's two terms, ceding thousands of square miles to the Federal government.

The Cherokee

The Cherokee (; , or ) people are one of the Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, they were concentrated in their homelands, in towns along river valleys of what is now southwestern ...

s insisted on their independence from state government authority and faced expulsion from their lands when a faction of Cherokees signed the Treaty of New Echota

The Treaty of New Echota was a treaty signed on December 29, 1835, in New Echota, Georgia, by officials of the United States government and representatives of a minority Cherokee political faction, the Treaty Party.

The treaty established terms ...

in 1835, obtaining money in exchange for their land. Despite protests from the elected Cherokee government and many white supporters, the Cherokees were forced to trek to the Indian Territory in 1838. Many died of disease and privation in the "Trail of Tears".

Nullification crisis

Toward the end of his first term, Jackson was forced to confront the state of South Carolina on the issue of the protective

Toward the end of his first term, Jackson was forced to confront the state of South Carolina on the issue of the protective tariff

A tariff or import tax is a duty (tax), duty imposed by a national Government, government, customs territory, or supranational union on imports of goods and is paid by the importer. Exceptionally, an export tax may be levied on exports of goods ...

. The protective tariff passed by Congress and signed into law by Jackson in 1832 was milder than that of 1828, but it further embittered many in the state. In response, several South Carolina citizens endorsed the "states rights

In American political discourse, states' rights are political powers held for the state governments rather than the federal government according to the United States Constitution, reflecting especially the enumerated powers of Congress and t ...

" principle of "nullification", which was enunciated by John C. Calhoun

John Caldwell Calhoun (; March 18, 1782March 31, 1850) was an American statesman and political theorist who served as the seventh vice president of the United States from 1825 to 1832. Born in South Carolina, he adamantly defended American s ...

, Jackson's vice president until 1832, in his South Carolina Exposition and Protest

The South Carolina Exposition and Protest, also known as Calhoun's Exposition, was written in December 1828 by John C. Calhoun, then Vice President of the United States under John Quincy Adams and later under Andrew Jackson. Calhoun did not formal ...

(1828). South Carolina dealt with the tariff by adopting the Ordinance of Nullification, which declared both the Tariff of 1828

A tariff or import tax is a duty imposed by a national government, customs territory, or supranational union on imports of goods and is paid by the importer. Exceptionally, an export tax may be levied on exports of goods or raw materials an ...

and the Tariff of 1832

The Tariff of 1832 ( 22nd Congress, session 1, ch. 227, , enacted July 14, 1832) was a protectionist tariff in the United States. Enacted under Andrew Jackson's presidency, it was largely written by former President John Quincy Adams, who had be ...

null and void within state borders.

Nullification was only the most recent in a series of state challenges to the authority of the federal government. In response to South Carolina's threat, Jackson sent seven small naval vessels and a man-of-war to Charleston in November 1832. On December 10, he issued a resounding proclamation against the nullifiers. South Carolina, the President declared, stood on "the brink of insurrection and treason", and he appealed to the people of the state to reassert their allegiance to that Union for which their ancestors had fought.

Senator Henry Clay, though an advocate of protection and a political rival of Jackson, piloted a compromise measure through Congress. Clay's 1833 compromise tariff specified that all duties more than 20% of the value of the goods imported were to be reduced by easy stages, so that by 1842, the duties on all articles would reach the level of the moderate tariff of 1816.

The rest of the South declared South Carolina's course unwise and unconstitutional. Eventually, South Carolina rescinded its action. Jackson had committed the federal government to the principle of Union supremacy. South Carolina, however, had obtained many of the demands it sought and had demonstrated that a single state could force its will on Congress.

Banking

Even before the nullification issue had been settled, another controversy arose to challenge Jackson's leadership. It concerned the rechartering of the

Even before the nullification issue had been settled, another controversy arose to challenge Jackson's leadership. It concerned the rechartering of the Second Bank of the United States

The Second Bank of the United States was the second federally authorized Second Report on Public Credit, Hamiltonian national bank in the United States. Located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the bank was chartered from February 1816 to January ...

. The First Bank of the United States

The President, Directors and Company of the Bank of the United States, commonly known as the First Bank of the United States, was a National bank (United States), national bank, chartered for a term of twenty years, by the United States Congress ...

had been established in 1791, under Alexander Hamilton's guidance and had been chartered for a 20-year period. After the Revolutionary War, the United States had a large war debt

War reparations are compensation payments made after a war by one side to the other. They are intended to cover Collateral damage, damage or injury inflicted during a war. War reparations can take the form of hard currency, precious metals, natur ...

to France and others, and the banking system of the fledgling nation was in disarray, as state banks printed their own currency, and the plethora of different bank notes

A banknote or bank notealso called a bill (North American English) or simply a noteis a type of paper money that is made and distributed ("issued") by a bank of issue, payable to the bearer on demand. Banknotes were originally issued by commer ...

made commerce difficult. Hamilton's national bank had been chartered to solve the debt problem and to unify the nation under one currency. While it stabilized the currency and stimulated trade, it was resented by Westerners and workers who believed that it was granting special favors to a few powerful men. When its charter expired in 1811, it was not renewed.

For the next few years, the banking business was in the hands of State-Chartered banks, which issued currency in excessive amounts, creating great confusion and fueling inflation and concerns that state banks could not provide the country with a uniform currency. The absence of a national bank during the War of 1812 greatly hindered financial operations of the government; therefore a second Bank of the United States was created in 1816.

From its inception, the Second Bank was unpopular in the newer states and territories and with less prosperous people everywhere. Opponents claimed the bank possessed a virtual monopoly over the country's credit and currency, and reiterated that it represented the interests of the wealthy elite. Jackson, elected as a popular champion against it, vetoed a bill to recharter the bank. He also detested banks due to a brush with bankruptcy in his youth. In his message to Congress, he denounced monopoly and special privilege, saying that "our rich men have not been content with equal protection and equal benefits, but have besought us to make them richer by act of Congress".

In the election campaign that followed, the bank question caused a fundamental division between the merchant, manufacturing and financial interests (generally creditors who favored tight money and high interest rates), and the laboring and agrarian sectors, who were often in debt to banks and therefore favored an increased money supply

In macroeconomics, money supply (or money stock) refers to the total volume of money held by the public at a particular point in time. There are several ways to define "money", but standard measures usually include currency in circulation (i ...

and lower interest rates. The outcome was an enthusiastic endorsement of "Jacksonism". Jackson saw his reelection in 1832 as a popular mandate to crush the bank irrevocably; he found a ready-made weapon in a provision of the bank's charter authorizing the removal of public funds.

In September 1833 Jackson ordered that no more government money be deposited in the bank and that the money already in its custody be gradually withdrawn in the ordinary course of meeting the expenses of government. Carefully selected state banks, stringently restricted, were provided as a substitute. For the next generation, the US would get by on a relatively unregulated state banking system. This banking system helped fuel westward expansion through easy credit, but kept the nation vulnerable to periodic panics. It was not until the Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

that the Federal government again chartered a national bank.

Jackson groomed Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was the eighth president of the United States, serving from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he served as Attorney General o ...

as his successor, and he was easily elected president in 1836. However, a few months into his administration, the country fell into a deep economic slump known as the Panic of 1837

The Panic of 1837 was a financial crisis in the United States that began a major depression (economics), depression which lasted until the mid-1840s. Profits, prices, and wages dropped, westward expansion was stalled, unemployment rose, and pes ...

, caused in large part by excessive speculation. Banks failed and unemployment soared. It was a devastating economic and social catastrophe that can be compared with the Panic of 1893

The Panic of 1893 was an economic depression in the United States. It began in February 1893 and officially ended eight months later. The Panic of 1896 followed. It was the most serious economic depression in history until the Great Depression of ...

and the Great Depression of 1929

Great may refer to:

Descriptions or measurements

* Great, a relative measurement in physical space, see Size

* Greatness, being divine, majestic, superior, majestic, or transcendent

People

* List of people known as "the Great"

* Artel Great (bo ...

, an event with repercussions every bit as deep as the Great Depression of the 1930s. There was an international dimension: much of the growth in the private sector and the investment in infrastructure by state governments had been financed by British capital. Several states and corporations defaulted permanently on their debts owed to London. For Europeans, investment in America became a dubious proposition, so American access to capital sharply declined for decades.

The depression had its roots in Jackson's economic hard money policies that blocked investment using paper money, insisting on gold and silver. But he had retired so his chosen successor van Buren was blamed for the disaster. In the 1840 presidential election, he was defeated by the Whig candidate William Henry Harrison and his running on a "People's Crusade" platform, despite descending from a plantation family. However, his presidency would prove a non-starter when he fell ill with pneumonia and died after only a month in office. John Tyler

John Tyler (March 29, 1790 – January 18, 1862) was the tenth president of the United States, serving from 1841 to 1845, after briefly holding office as the tenth vice president of the United States, vice president in 1841. He was elected ...

, the new vice president, succeeded him. Tyler was not popular since he had not been elected to the presidency, and was widely referred to as "His Accidency". He rejected Whig economic policies, so that party expelled him, and the Whigs lost their opportunity to reshape government policy.

Economic historians have explored the high degree of financial and economic instability in the Jacksonian era. For the most part, they follow the conclusions of Peter Temin

Peter Temin (; born 17 December 1937) is an economist and economic historian, serving as the Gray Professor Emeritus of Economics at MIT, where he was formerly the head of the Economics Department.

Education

Temin graduated from Swarthmore Colle ...

, who absolved Jackson's policies, and blamed international events beyond American control, such as conditions in Mexico, China and Britain. A survey of economic historians in 1995 show that the vast majority concur with Temin's conclusion that "the inflation and financial crisis of the 1830s had their origin in events largely beyond President Jackson's control and would have taken place whether or not he had acted as he did vis-a-vis the Second Bank of the U.S."

Age of Reform

Spurred on by theSecond Great Awakening

The Second Great Awakening was a Protestant religious revival during the late 18th to early 19th century in the United States. It spread religion through revivals and emotional preaching and sparked a number of reform movements. Revivals were a k ...

, Americans entered a period of rapid social change and experimentation. New social movements arose, as well as many new alternatives to traditional religious thought. This period of American history was marked by the destruction of some traditional roles of society and the erection of new social standards. One of the unique aspects of the Age of Reform was that it was heavily grounded in religion, unlike the anti-clericalism that characterized contemporary European reformers.

Second Great Awakening

TheSecond Great Awakening

The Second Great Awakening was a Protestant religious revival during the late 18th to early 19th century in the United States. It spread religion through revivals and emotional preaching and sparked a number of reform movements. Revivals were a k ...

was a Protestant religious revival movement that flourished in 1800–1840 in every region. It expressed Arminian theology by which every person could be saved through a direct personal confrontation with Jesus Christ during an intensely emotional revival meeting. Millions joined the churches, often new denominations. Many converts believed that the Awakening heralded a new millennial age

Millennialism () or chiliasm (from the Greek equivalent) is a belief which is held by some religious denominations. According to this belief, a Messianic Age will be established on Earth prior to the Last Judgment and the future permanent stat ...

, so that the Second Great Awakening stimulated the establishment of many reform movements designed to remedy the evils of society before the Second Coming of Jesus Christ. For example, the charismatic Charles Grandison Finney

Charles Grandison Finney (August 29, 1792 – August 16, 1875) was a controversial American Presbyterian minister and leader in the Second Great Awakening in the United States. He has been called the "Father of Old Christian revival, Revivalism ...

, in upstate New York

Upstate New York is a geographic region of New York (state), New York that lies north and northwest of the New York metropolitan area, New York City metropolitan area of downstate New York. Upstate includes the middle and upper Hudson Valley, ...

and the Old Northwest

The Northwest Territory, also known as the Old Northwest and formally known as the Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, was formed from part of the unorganized western territory of the United States after the American Revolution. Established ...

was highly effective. At the Rochester Revival of 1830, prominent citizens concerned with the city's poverty and absenteeism had invited Finney to the city. The wave of religious revival contributed to tremendous growth of the Methodist, Baptists, Disciples, and other evangelical denominations.

Utopians

As theSecond Great Awakening

The Second Great Awakening was a Protestant religious revival during the late 18th to early 19th century in the United States. It spread religion through revivals and emotional preaching and sparked a number of reform movements. Revivals were a k ...

challenged the traditional beliefs of the Calvinist

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed Protestantism, Continenta ...

faith, the movement inspired other groups to call into question their views on religion and society. Many of these utopia

A utopia ( ) typically describes an imagined community or society that possesses highly desirable or near-perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book ''Utopia (book), Utopia'', which describes a fictiona ...

nist groups also believed in millennialism

Millennialism () or chiliasm (from the Greek equivalent) is a belief which is held by some religious denominations. According to this belief, a Messianic Age will be established on Earth prior to the Last Judgment and the future permanent s ...

which prophesied the return of Christ and the beginning of a new age. The Harmony Society

The Harmony Society was a Christian theosophy and pietist society founded in Iptingen, Germany, in 1785. Due to religious persecution by the Lutheran Church and the government in Württemberg, the group moved to the United States,Robert Paul S ...

made three attempts to effect a millennial society with the most notable example at New Harmony, Indiana

New Harmony is a historic town on the Wabash River in Harmony Township, Posey County, Indiana, Harmony Township, Posey County, Indiana, Posey County, Indiana. It lies north of Mount Vernon, Indiana, Mount Vernon, the county seat, and is part of ...

. Later, Scottish industrialist Robert Owen

Robert Owen (; 14 May 1771 – 17 November 1858) was a Welsh textile manufacturer, philanthropist, political philosopher and social reformer, and a founder of utopian socialism and the cooperative movement, co-operative movement. He strove to ...

bought New Harmony and attempted to form a secular Utopian community there. Frenchman Charles Fourier

François Marie Charles Fourier (; ; 7 April 1772 – 10 October 1837) was a French philosopher, an influential early socialist thinker, and one of the founders of utopian socialism. Some of his views, held to be radical in his lifetime, have be ...

began a similar secular experiment with his "phalanxes" spread across the Midwestern United States. However, none of these utopian communities lasted very long except for the Shakers.

One of the earliest movements was that of the Shakers

The United Society of Believers in Christ's Second Appearing, more commonly known as the Shakers, are a Millenarianism, millenarian Restorationism, restorationist Christianity, Christian sect founded in England and then organized in the Unit ...

, who held all their possessions in "common

Common may refer to:

As an Irish surname, it is anglicised from Irish Gaelic surname Ó Comáin.

Places

* Common, a townland in County Tyrone, Northern Ireland

* Boston Common, a central public park in Boston, Massachusetts

* Cambridge Com ...

" and lived in a prosperous, inventive, self-supporting society, with no sexual activity. The Shakers, founded by an English immigrant to the United States Mother Ann Lee

Ann Lee (29 February 1736 – 8 September 1784), commonly known as Mother Ann Lee, was the founding leader of the Shakers, later changed to United Society of Believers in Christ's Second Appearing following her death. She was born during ...

, peaked at around 6,000 in 1850 in communities from Maine to Kentucky. The Shakers condemned sexuality

Human sexuality is the way people experience and express themselves sexually. This involves biological, psychological, physical, erotic, emotional, social, or spiritual feelings and behaviors. Because it is a broad term, which has varied ...

and demanded absolute celibacy. New members could only come from conversions, and from children brought to the Shaker villages. The Shakers persist to this day—there is still an active Shaker community in Sabbathday Lake, Maine—but the Shaker population declined dramatically by the Civil War. They are famed for their design, especially their furniture and handicrafts.

The Perfectionist movement, led by John Humphrey Noyes

John Humphrey Noyes (September 3, 1811 – April 13, 1886) was an American preacher, radical religious philosopher, and Utopian socialism, utopian socialist. He founded the Putney Community, Putney, Oneida Community, Oneida, and Wallingford ...

, founded the utopian Oneida Community

The Oneida Community ( ) was a Christian perfection, perfectionist religious communal society founded by John Humphrey Noyes and his followers in 1848 near Oneida, New York. The community believed that Jesus had Hyper-preterism, already return ...

in 1848 with fifty-one devotees, in Oneida, New York

Oneida () is a city in Madison County in the U.S. state of New York. It is located west of Oneida Castle (in Oneida County) and east of Wampsville. The population was 10,329 at the 2020 census, down from 11,390 in 2010. The city, like b ...

. Noyes believed that the act of final conversion led to absolute and complete release from sin. The Oneida Community believed in the abolition of marriage or monogamous relationships and that sex should be free to whoever consented to it. As opposed to 20th century social movements such as the Sexual revolution

The sexual revolution, also known as the sexual liberation, was a social movement that challenged traditional codes of behavior related to sexuality and interpersonal relationships throughout the Western world from the late 1950s to the early 1 ...

of the 1960s, the Onedians did not seek consequence-free sex for mere pleasure, but believed that, because the logical outcome of intercourse was pregnancy, that raising children should be a communal responsibility. After the original founders died or became elderly, their children rejected the concept of free love and returned to traditional family models. Oneida thrived for many years as a joint-stock company

A joint-stock company (JSC) is a business entity in which shares of the company's stock can be bought and sold by shareholders. Each shareholder owns company stock in proportion, evidenced by their shares (certificates of ownership). Shareho ...

and continues today as a silverware company.

Mormon

Mormons are a religious and cultural group related to Mormonism, the principal branch of the Latter Day Saint movement started by Joseph Smith in upstate New York during the 1820s. After Smith's death in 1844, the movement split into several ...

history began in this era under Joseph Smith

Joseph Smith Jr. (December 23, 1805June 27, 1844) was an American religious and political leader and the founder of Mormonism and the Latter Day Saint movement. Publishing the Book of Mormon at the age of 24, Smith attracted tens of thou ...

's guidance after he experienced a religious conversion. Because of their unusual beliefs, which included recognition of the Book of Mormon

The Book of Mormon is a religious text of the Latter Day Saint movement, first published in 1830 by Joseph Smith as ''The Book of Mormon: An Account Written by the Hand of Mormon upon Plates Taken from the Plates of Nephi''.

The book is one of ...

as an additional book of scripture comparable to the Bible, Mormons were rejected by mainstream Christians and forced to flee en masse from upstate New York to Ohio, to Missouri and then to Nauvoo, Illinois

Nauvoo ( ; from the ) is a small city in Hancock County, Illinois, United States, on the Mississippi River near Fort Madison, Iowa. The population of Nauvoo was 950 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. Nauvoo attracts visitors for its h ...

, where Smith was killed and they were again forced to flee. They settled around the Great Salt Lake

The Great Salt Lake is the largest saltwater lake in the Western Hemisphere and the eighth-largest terminal lake in the world. It lies in the northern part of the U.S. state of Utah and has a substantial impact upon the local climate, partic ...

, then part of Mexico. In 1848, the region came under American control and later formed the Utah

Utah is a landlocked state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is one of the Four Corners states, sharing a border with Arizona, Colorado, and New Mexico. It also borders Wyoming to the northea ...

Territory. National policy was to suppress polygamy, and Utah was only admitted as a state in 1896 after the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, informally known as the LDS Church or Mormon Church, is a Nontrinitarianism, nontrinitarian Restorationism, restorationist Christianity, Christian Christian denomination, denomination and the ...

backtracked from Smith's demand that all the leaders practice polygamy.

For Americans wishing to bridge the gap between the earthly and spiritual worlds, spiritualism

Spiritualism may refer to:

* Spiritual church movement, a group of Spiritualist churches and denominations historically based in the African-American community

* Spiritualism (beliefs), a metaphysical belief that the world is made up of at leas ...

provided a means of communing with the dead. Spiritualists used mediums

Mediumship is the practice of purportedly mediating communication between familiar spirits or spirits of the dead and living human beings. Practitioners are known as "mediums" or "spirit mediums". There are different types of mediumship or spir ...

to communicate between the living and the dead through a variety of different means. The Fox sisters

The Fox sisters were three sisters from Rochester, New York who played an important role in the creation of Spiritualism: Leah (April 8, 1813 – November 1, 1890), Margaretta (also called Maggie), (October 7, 1833 – March 8, 1893) and Catheri ...

, the most famous mediums, claimed to have a direct link to the spirit world. Spiritualism would gain a much larger following after the heavy number of casualties during the Civil War; First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln

Mary Ann Todd Lincoln (Birth name, née Todd; December 13, 1818July 16, 1882) was First Lady of the United States from 1861 until the assassination of her husband, President Abraham Lincoln, in 1865.

Mary Todd was born into a large and wealthy ...

was a believer.

Other groups seeking spiritual awakening also gained popularity in the mid-19th century. Philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson (May 25, 1803April 27, 1882), who went by his middle name Waldo, was an American essayist, lecturer, philosopher, minister, abolitionism, abolitionist, and poet who led the Transcendentalism, Transcendentalist movement of th ...

began the American transcendentalist movement in New England, to promote self-reliance and better understanding of the universe through contemplation of the over-soul

"The Over-Soul" is an essay by Ralph Waldo Emerson first published in 1841. With the human soul as its overriding subject, several general themes are treated: (1) the existence and nature of the human soul; (2) the relationship between the soul a ...

. Transcendentalism was essentially an American offshoot of the Romantic movement in Europe. Among transcendentalists' core beliefs was an ideal spiritual state that "transcends" the physical, and is only realized through intuition

Intuition is the ability to acquire knowledge without recourse to conscious reasoning or needing an explanation. Different fields use the word "intuition" in very different ways, including but not limited to: direct access to unconscious knowledg ...

rather than doctrine. Like many of the movements, the transcendentalists split over the idea of self-reliance. While Emerson and Henry David Thoreau

Henry David Thoreau (born David Henry Thoreau; July 12, 1817May 6, 1862) was an American naturalist, essayist, poet, and philosopher. A leading Transcendentalism, transcendentalist, he is best known for his book ''Walden'', a reflection upon sim ...

promoted the idea of independent living, George Ripley George Ripley may refer to:

*George Ripley (alchemist) (died 1490), English author and alchemist

*George Ripley (transcendentalist)

George Ripley (October 3, 1802 – July 4, 1880) was an American social reformer, Unitarian minister, and jour ...

brought transcendentalists together in a phalanx at Brook Farm

Brook Farm, also called the Brook Farm Institute of Agriculture and EducationFelton, 124 or the Brook Farm Association for Industry and Education,Rose, 140 was a utopian experiment in communal living in the United States in the 1840s. It was ...

to live cooperatively. Other authors such as Nathaniel Hawthorne

Nathaniel Hawthorne (né Hathorne; July 4, 1804 – May 19, 1864) was an American novelist and short story writer. His works often focus on history, morality, and religion.

He was born in 1804 in Salem, Massachusetts, from a family long associat ...

and Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe (; January 19, 1809 – October 7, 1849) was an American writer, poet, editor, and literary critic who is best known for his poetry and short stories, particularly his tales involving mystery and the macabre. He is widely re ...

rejected transcendentalist beliefs.

So many of these new religious and spiritual groups began or concentrated within miles of each other in upstate New York that this area was nicknamed "the burned-over district

The term "burned-over district" refers to the western and parts of the central regions of New York State in the early 19th century, where religious revivals and the formation of new religious movements of the Second Great Awakening took place ...

" because so few people had not converted.

Public schools movement

Education in the United States had long been a local affair with schools governed by locally elected school boards. As with much of the culture of the United States, education varied widely in the North and the South. In the New England statespublic education

A state school, public school, or government school is a primary school, primary or secondary school that educates all students without charge. They are funded in whole or in part by taxation and operated by the government of the state. State-f ...

was common, although it was often class-based with the working class receiving little benefits. Instruction and curriculum were all locally determined and teachers were expected to meet rigorous demands of strict moral behaviour. Schools taught religious values and applied Calvinist

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed Protestantism, Continenta ...

philosophies of discipline which included corporal punishment

A corporal punishment or a physical punishment is a punishment which is intended to cause physical pain to a person. When it is inflicted on Minor (law), minors, especially in home and school settings, its methods may include spanking or Padd ...

and public humiliation. In the South, there was very little organization of a public education system. Public schools were very rare and most education took place in the home with the family acting as instructors. The wealthier planter families hired tutors for instruction in the classics

Classics, also classical studies or Ancient Greek and Roman studies, is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, ''classics'' traditionally refers to the study of Ancient Greek literature, Ancient Greek and Roman literature and ...

, but many yeoman farming families had little access to education outside of the family unit.

The reform movement in education began in Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

when Horace Mann

Horace Mann (May 4, 1796August 2, 1859) was an American educational reformer, slavery abolitionist and Whig Party (United States), Whig politician known for his commitment to promoting public education, he is thus also known as ''The Father of A ...

started the common school movement. Mann advocated a statewide curriculum and instituted financing of school through local property taxes. Mann also fought protracted battles against the Calvinist influence in discipline, preferring positive reinforcement to physical punishment. Most children learned to read and write and spell from Noah Webster

Noah Webster (October 16, 1758 – May 28, 1843) was an American lexicographer, textbook pioneer, English-language spelling reformer, political writer, editor, and author. He has been called the "Father of American Scholarship and Education" ...

's ''Blue Backed Speller'' and later the McGuffey Readers

The Eclectic Readers (commonly, but informally known as the McGuffey Readers) were a series of graded primers for grade levels 1–6. They were widely used as textbooks in American schools from the mid-19th century to the early 20th century, and ...

. The readings inculcated moral values as well as literacy. Most states tried to emulate Massachusetts, and New England retained its leadership position for another century. German immigrants brought in kindergarten

Kindergarten is a preschool educational approach based on playing, singing, practical activities such as drawing, and social interaction as part of the transition from home to school. Such institutions were originally made in the late 18th cen ...

s and the Gymnasium (school)

''Gymnasium'' (and Gymnasium (school)#By country, variations of the word) is a term in various European languages for a secondary school that prepares students for higher education at a university. It is comparable to the US English term ''U ...

, while Yankee orators sponsored the Lyceum

The lyceum is a category of educational institution defined within the education system of many countries, mainly in Europe. The definition varies among countries; usually it is a type of secondary school. Basic science and some introduction to ...

movement that provided popular education for hundreds of towns and small cities.

Asylum movement

The social conscience that was raised in the early 19th century helped to elevate the awareness of mental illness and its treatment. A leading advocate of reform for mental illness wasDorothea Dix

Dorothea Lynde Dix (April 4, 1802July 17, 1887) was an American advocate on behalf of the poor insane, mentally ill. By her vigorous and sustained program of lobbying state legislatures and the United States Congress, she helped create the fir ...

, a Massachusetts woman who made an intensive study of the conditions that the mentally ill were kept in. Dix's report to the Massachusetts state legislature along with the development of the Kirkbride Plan

The Kirkbride Plan was a system of mental asylum design advocated by American psychiatrist Thomas Story Kirkbride (1809–1883) in the mid-19th century. The asylums built in the Kirkbride design, often referred to as Kirkbride Buildings (or simp ...

helped to alleviate the miserable conditions for many of the mentally ill. Although these facilities often fell short of their intended purpose, reformers continued to follow Dix's advocacy and call for increased study and treatment of mental illness.

Women

Feminist essays fromJohn Neal

John Neal (August 25, 1793 – June 20, 1876) was an American writer, critic, editor, lecturer, and activist. Considered both eccentric and influential, he delivered speeches and published essays, novels, poems, and short stories between the 1 ...

in the 1820s filled an intellectual gap between Judith Sargent Murray

Judith Sargent Stevens Murray (May 1, 1751 – June 9, 1820) was an early American advocate for women's rights, an essay writer, playwright, poet, and letter writer. She was one of the first American proponents of the idea of the equality of the ...

and her pre-Seneca Falls Convention

The Seneca Falls Convention was the first women's rights convention. Its organizers advertised it as "a convention to discuss the social, civil, and religious condition and rights of woman". Held in the Wesleyan Chapel of the town of Seneca ...

successors like Sarah Moore Grimké

Sarah Moore Grimké (November 26, 1792 – December 23, 1873) was an American abolitionist, widely held to be the mother of the women's suffrage movement. Born and reared in South Carolina to a prominent and wealthy planter family, she mo ...

, Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton ( Cady; November 12, 1815 – October 26, 1902) was an American writer and activist who was a leader of the women's rights movement in the U.S. during the mid- to late-19th century. She was the main force behind the 1848 ...

, and Margaret Fuller

Sarah Margaret Fuller (May 23, 1810 – July 19, 1850), sometimes referred to as Margaret Fuller Ossoli, was an American journalist, editor, critic, translator, and women's rights advocate associated with the American transcendentalism movemen ...

. As a male writer insulated from many common forms of attack against female feminist thinkers, Neal's advocacy was crucial to bringing the field back into the American mainstream.

During the building of the new republic, American women gained a limited political voice in what is known as republican motherhood

"Republican motherhood" is a 20th-century term for an 18th-century attitude toward women's roles present in the emerging United States before, during, and after the American Revolution. It centered on the belief that the patriots' daughters shou ...

. Under this philosophy, as promoted by leaders such as Abigail Adams