History Of Senegal on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of

The history of

In the absence of written sources and monumental ruins in this region, the history of the early centuries of the modern era must be based primarily on archaeological excavations, the writing of early Arab geographers and travelers, and data derived from oral tradition. Combining these data suggests that Senegal was first populated from the north and east in several waves of migration, the last being that of the Wolof, the Fulani and the Serer who dominate the area today. Oral traditions relate that in much of northern Senegal

In the absence of written sources and monumental ruins in this region, the history of the early centuries of the modern era must be based primarily on archaeological excavations, the writing of early Arab geographers and travelers, and data derived from oral tradition. Combining these data suggests that Senegal was first populated from the north and east in several waves of migration, the last being that of the Wolof, the Fulani and the Serer who dominate the area today. Oral traditions relate that in much of northern Senegal

The medieval history of the Sahel is characterized by the consolidation of settlements into large state entities – the

The medieval history of the Sahel is characterized by the consolidation of settlements into large state entities – the

Two other major political entities were formed and grew during the 13th and 14th century: the

Two other major political entities were formed and grew during the 13th and 14th century: the

Encouraged by

Encouraged by

Created in 1621, the

Created in 1621, the

The Black Code, enacted in 1685, regulated the trafficking of slaves in the American colonies.

In Senegal, trading posts were established in

The Black Code, enacted in 1685, regulated the trafficking of slaves in the American colonies.

In Senegal, trading posts were established in

, accessed 9 July 2008. In 1758 the French settlement was captured by a British expedition as part of the

The

The

In January 1959, Senegal and the

In January 1959, Senegal and the

full text online

411pp; *Robinson Jr, David Wallace ''Faidherbe, Senegal and Islam'', New York, Columbia University, 1965, 104 pages (thèse) * * Wikle, Thomas A., and Dale R. Lightfoot. "Landscapes of the Slave Trade in Senegal and The Gambia", ''Focus on Geography'' (2014) 57#1 pp. 14–24.

"VIIe Colloque euroafricain"

Aline Robert – Les sources écrites européennes du XVe au XIXe s : un apport complémentaire pour la connaissance du passé africain

{{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Senegal Senegal (colonial)

The history of

The history of Senegal

Senegal, officially the Republic of Senegal, is the westernmost country in West Africa, situated on the Atlantic Ocean coastline. It borders Mauritania to Mauritania–Senegal border, the north, Mali to Mali–Senegal border, the east, Guinea t ...

is commonly divided into a number of periods, encompassing the prehistoric

Prehistory, also called pre-literary history, is the period of human history between the first known use of stone tools by hominins million years ago and the beginning of recorded history with the invention of writing systems. The use o ...

era, the precolonial period, colonialism, and the contemporary era.

Paleolithic

The earliest evidence of human life is found in the valley of the Falémé in the south-east. The presence of man in theLower Paleolithic

The Lower Paleolithic (or Lower Palaeolithic) is the earliest subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age. It spans the time from around 3.3 million years ago when the first evidence for stone tool production and use by hominins appears ...

is attested by the discovery of stone tools

Stone tools have been used throughout human history but are most closely associated with prehistoric cultures and in particular those of the Stone Age. Stone tools may be made of either ground stone or knapped stone, the latter fashioned by a c ...

characteristic of Acheulean

Acheulean (; also Acheulian and Mode II), from the French after the type site of Saint-Acheul, is an archaeological industry of stone tool manufacture characterized by the distinctive oval and pear-shaped "hand axes" associated with ''Homo ...

such as hand axe

A hand axe (or handaxe or Acheulean hand axe) is a Prehistory, prehistoric stone tool with two faces that is the longest-used tool in human history. It is made from stone, usually flint or chert that has been "reduced" and shaped from a larger ...

s reported by Théodore Monod at the tip of Fann in the peninsula of Cap-Vert

Cap-Vert, or the Cape Verde Peninsula, and Kap Weert or Bopp bu Nëtëx (in Wolof), is a peninsula in Senegal and the westernmost point of the continent of Africa and of the Afro-Eurasia mainland. Portuguese explorers called it Cabo Verde or ...

in 1938, or cleavers found in the south-east. There were also found stones shaped by the Levallois technique

The Levallois technique () is a name given by archaeologists to a distinctive type of stone knapping developed around 250,000 to 400,000Shipton, C. (2022). Predetermined Refinement: The Earliest Levallois of the Kapthurin Formation. *Journal of ...

, characteristic of the Middle Paleolithic

The Middle Paleolithic (or Middle Palaeolithic) is the second subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age as it is understood in Europe, Africa and Asia. The term Middle Stone Age is used as an equivalent or a synonym for the Middle P ...

. Mousterian

The Mousterian (or Mode III) is an Industry (archaeology), archaeological industry of Lithic technology, stone tools, associated primarily with the Neanderthals in Europe, and with the earliest anatomically modern humans in North Africa and We ...

Industry is represented mainly by scrapers found in the peninsula of Cap-Vert, as well in the low and middle valleys of the Senegal

Senegal, officially the Republic of Senegal, is the westernmost country in West Africa, situated on the Atlantic Ocean coastline. It borders Mauritania to Mauritania–Senegal border, the north, Mali to Mali–Senegal border, the east, Guinea t ...

and the Falémé. Some pieces are explicitly linked to hunting, like those found in Tiémassass, near M'Bour, a controversial site that some claim belongs to the Upper Paleolithic

The Upper Paleolithic (or Upper Palaeolithic) is the third and last subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age. Very broadly, it dates to between 50,000 and 12,000 years ago (the beginning of the Holocene), according to some theories ...

, while other argue in favor of the Neolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

.

Neolithic

In Senegambia, the period when humans became hunters, fishermen and producers (farmer and artisan) are all well represented and studied. This is when more elaborate objects andceramic

A ceramic is any of the various hard, brittle, heat-resistant, and corrosion-resistant materials made by shaping and then firing an inorganic, nonmetallic material, such as clay, at a high temperature. Common examples are earthenware, porcela ...

s emerged. But gray areas remain. Although the characteristics and manifestations of civilization from the Neolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

have been identified their origins and relationship have not yet fully defined.

What can be distinguished is:

*The dig of Cape Manuel: the Neolithic deposit Manueline Dakar was discovered in 1940. Basalt

Basalt (; ) is an aphanite, aphanitic (fine-grained) extrusive igneous rock formed from the rapid cooling of low-viscosity lava rich in magnesium and iron (mafic lava) exposed at or very near the planetary surface, surface of a terrestrial ...

rocks including ankaramite were used for making microlithic tools such as axes or planes. Such tools have been found at Gorée

(; "Gorée Island"; ) is one of the 19 (i.e. districts) of the city of Dakar, Senegal. It is an island located at sea from the main harbour of Dakar (), famous as a destination for people interested in the Atlantic slave trade.

Its populatio ...

and the Magdalen Islands

The Magdalen Islands (, ) are a Canadian archipelago in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Since 2005, the 12-island archipelago is divided into two municipalities: the majority-francophone Municipality of Îles-de-la-Madeleine and the majority-angloph ...

, indicating the activity of shipbuilding

Shipbuilding is the construction of ships and other Watercraft, floating vessels. In modern times, it normally takes place in a specialized facility known as a shipyard. Shipbuilders, also called shipwrights, follow a specialized occupation th ...

by nearby fishermen.

*The dig of Bel-Air: Neolithic Bélarien tools, usually made out of flint

Flint, occasionally flintstone, is a sedimentary cryptocrystalline form of the mineral quartz, categorized as the variety of chert that occurs in chalk or marly limestone. Historically, flint was widely used to make stone tools and start ...

, are present in the dunes of the west, near the current capital. In addition to axes, adze

An adze () or adz is an ancient and versatile cutting tool similar to an axe but with the cutting edge perpendicular to the handle rather than parallel. Adzes have been used since the Stone Age. They are used for smoothing or carving wood in ha ...

s and pottery, there is also a statuette, the Venus Thiaroye

*The dig of Khant: the Khanty creek, located in the north near Kayar in the lower valley of the Senegal River

The Senegal River ( or "Senegal" - compound of the Serer term "Seen" or "Sene" or "Sen" (from Roog Seen, Supreme Deity in Serer religion) and "O Gal" (meaning "body of water")); , , , ) is a river in West Africa; much of its length mark ...

, gave its name to a Neolithic industry which mainly uses bone and wood. This deposit is on the list of closed sites and monuments of Senegal.

*The dig the Falémé located in the south-east of Senegal, has uncovered a Neolithic Falemian tools industry that produced polished materials as diverse as sandstone

Sandstone is a Clastic rock#Sedimentary clastic rocks, clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of grain size, sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate mineral, silicate grains, Cementation (geology), cemented together by another mineral. Sand ...

, hematite

Hematite (), also spelled as haematite, is a common iron oxide compound with the formula, Fe2O3 and is widely found in rocks and soils. Hematite crystals belong to the rhombohedral lattice system which is designated the alpha polymorph of . ...

, shale

Shale is a fine-grained, clastic sedimentary rock formed from mud that is a mix of flakes of Clay mineral, clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g., Kaolinite, kaolin, aluminium, Al2Silicon, Si2Oxygen, O5(hydroxide, OH)4) and tiny f ...

, quartz

Quartz is a hard, crystalline mineral composed of silica (silicon dioxide). The Atom, atoms are linked in a continuous framework of SiO4 silicon–oxygen Tetrahedral molecular geometry, tetrahedra, with each oxygen being shared between two tet ...

, and flint

Flint, occasionally flintstone, is a sedimentary cryptocrystalline form of the mineral quartz, categorized as the variety of chert that occurs in chalk or marly limestone. Historically, flint was widely used to make stone tools and start ...

. Grinding equipment and pottery from the period are well represented at the site.

*The Neolithic civilization of the Senegal River valley and the Ferlo are the least well known due to not always being separated.

Prehistory

In the case of Senegal, the periodization ofprehistory

Prehistory, also called pre-literary history, is the period of human history between the first known use of stone tools by hominins million years ago and the beginning of recorded history with the invention of writing systems. The use ...

remains controversial. It is often described as beginning with the age of metallurgy

Metallurgy is a domain of materials science and engineering that studies the physical and chemical behavior of metallic elements, their inter-metallic compounds, and their mixtures, which are known as alloys.

Metallurgy encompasses both the ...

, thus placing it between the first metalworking

Metalworking is the process of shaping and reshaping metals in order to create useful objects, parts, assemblies, and large scale structures. As a term, it covers a wide and diverse range of processes, skills, and tools for producing objects on e ...

and the appearance of writing

Writing is the act of creating a persistent representation of language. A writing system includes a particular set of symbols called a ''script'', as well as the rules by which they encode a particular spoken language. Every written language ...

. Other approaches exist such as that of Guy Thilmans and his team in 1980, who felt that any archeology from pre-colonial could be attached to that designation or that of Hamady Bocoum, who speaks of "Historical Archaeology" from the 4th century, at least for the former Tekrur.

A variety of archaeological remains have been found:

* On the coast and in river estuaries of the Senegal

Senegal, officially the Republic of Senegal, is the westernmost country in West Africa, situated on the Atlantic Ocean coastline. It borders Mauritania to Mauritania–Senegal border, the north, Mali to Mali–Senegal border, the east, Guinea t ...

, Saloum

The Kingdom of Saloum ( Serer: ''Saluum'' or ''Saalum'') was a Serer kingdom in present-day Senegal and parts of Gambia. The precolonial capital was the city of Kahone. Re-established in 2017, Saloum is now a non-sovereign traditional monarch ...

, Gambia

The Gambia, officially the Republic of The Gambia, is a country in West Africa. Geographically, The Gambia is the List of African countries by area, smallest country in continental Africa; it is surrounded by Senegal on all sides except for ...

, and Casamance rivers, burial mounds with clusters of shells often referred to as middens. 217 of these clusters have been identified in the Saloum Delta alone, for example in Joal-Fadiouth, Mounds in the Saloum Delta have been dated back as far as 400 BCE, and part of the Saloum Delta is now a World Heritage Site

World Heritage Sites are landmarks and areas with legal protection under an treaty, international treaty administered by UNESCO for having cultural, historical, or scientific significance. The sites are judged to contain "cultural and natural ...

. Funerary sites or tumuli were built there during the 8th to 16th centuries. They are also found in the north near Saint-Louis, and in the estuary of the Casamance.

*The West is rich in burial mounds of sand that the Wolof refer to as ''mbanaar'', which translates to "graves", A solid gold pectoral

Pectoral may refer to:

* The chest region and anything relating to it.

* Pectoral cross, a cross worn on the chest

* a decorative, usually jeweled version of a gorget

* Pectoral (Ancient Egypt), a type of jewelry worn in ancient Egypt

* Pectora ...

of mass 191 g has also been discovered near Saint-Louis.

*In a huge area of nearly km2 located in the center-south around the Gambia there have been found alignments of boulders known as the Stone Circles of Senegambia which were placed on the list of UNESCO World Heritage

World Heritage Sites are landmarks and areas with legal protection under an international treaty

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between sovereign states and/or international organizations that is governed by int ...

sites in 2006. Two of these sites are located within the territory of Senegal: Sine Ngayène and Sine Wanar, both located in the Nioro du Rip Department. Sine Ngayène has 52 stone circles including a double circle. At Wanar, they number 24 and the stones are smaller. There are stone-carved lyre in the laterite

Laterite is a soil type rich in iron and aluminium and is commonly considered to have formed in hot and wet tropical areas. Nearly all laterites are of rusty-red coloration, because of high iron oxide content. They develop by intensive and prolo ...

, Y- or A-shaped.

*The existence of proto-historic ruins in the middle Senegal River valley was confirmed in the late 1970s. Pottery, perforated ceramic

A ceramic is any of the various hard, brittle, heat-resistant, and corrosion-resistant materials made by shaping and then firing an inorganic, nonmetallic material, such as clay, at a high temperature. Common examples are earthenware, porcela ...

discs or ornaments have been unearthed. Excavations at thé site of Sinthiou Bara, near Matam, have proved particularly fruitful. They have revealed, for example, the flow of trans-Saharan trade from distant parts of North Africa.

Early inhabitants

In the absence of written sources and monumental ruins in this region, the history of the early centuries of the modern era must be based primarily on archaeological excavations, the writing of early Arab geographers and travelers, and data derived from oral tradition. Combining these data suggests that Senegal was first populated from the north and east in several waves of migration, the last being that of the Wolof, the Fulani and the Serer who dominate the area today. Oral traditions relate that in much of northern Senegal

In the absence of written sources and monumental ruins in this region, the history of the early centuries of the modern era must be based primarily on archaeological excavations, the writing of early Arab geographers and travelers, and data derived from oral tradition. Combining these data suggests that Senegal was first populated from the north and east in several waves of migration, the last being that of the Wolof, the Fulani and the Serer who dominate the area today. Oral traditions relate that in much of northern Senegal Mande people

Mande may refer to:

* Mandé peoples of western Africa

* Mande languages, their Niger-Congo languages

* Manding, a term covering a subgroup of Mande peoples, and sometimes used for one of them, Mandinka

* Garo people of northeastern India and no ...

were the earliest inhabitants, although archaeological evidence of this is slim. Africanist historian Donald R. Wright has suggested that place-names in the Gambia

The Gambia, officially the Republic of The Gambia, is a country in West Africa. Geographically, The Gambia is the List of African countries by area, smallest country in continental Africa; it is surrounded by Senegal on all sides except for ...

and Casamance regions indicate "that the earliest inhabitants might be identified most closely with one of several related groups—Bainunk, Kasanga, Beafada... To these were added Serer, who moved southward during the first millennium A.D. from the Senegal River valley, and Mande-speaking peoples, who arrived later still from the east." He also cautions, however, that attempting to project modern-day ethnic definitions onto people who lived hundreds or thousands of years ago is at best highly speculative and at worst counterproductive.

Kingdoms and empires

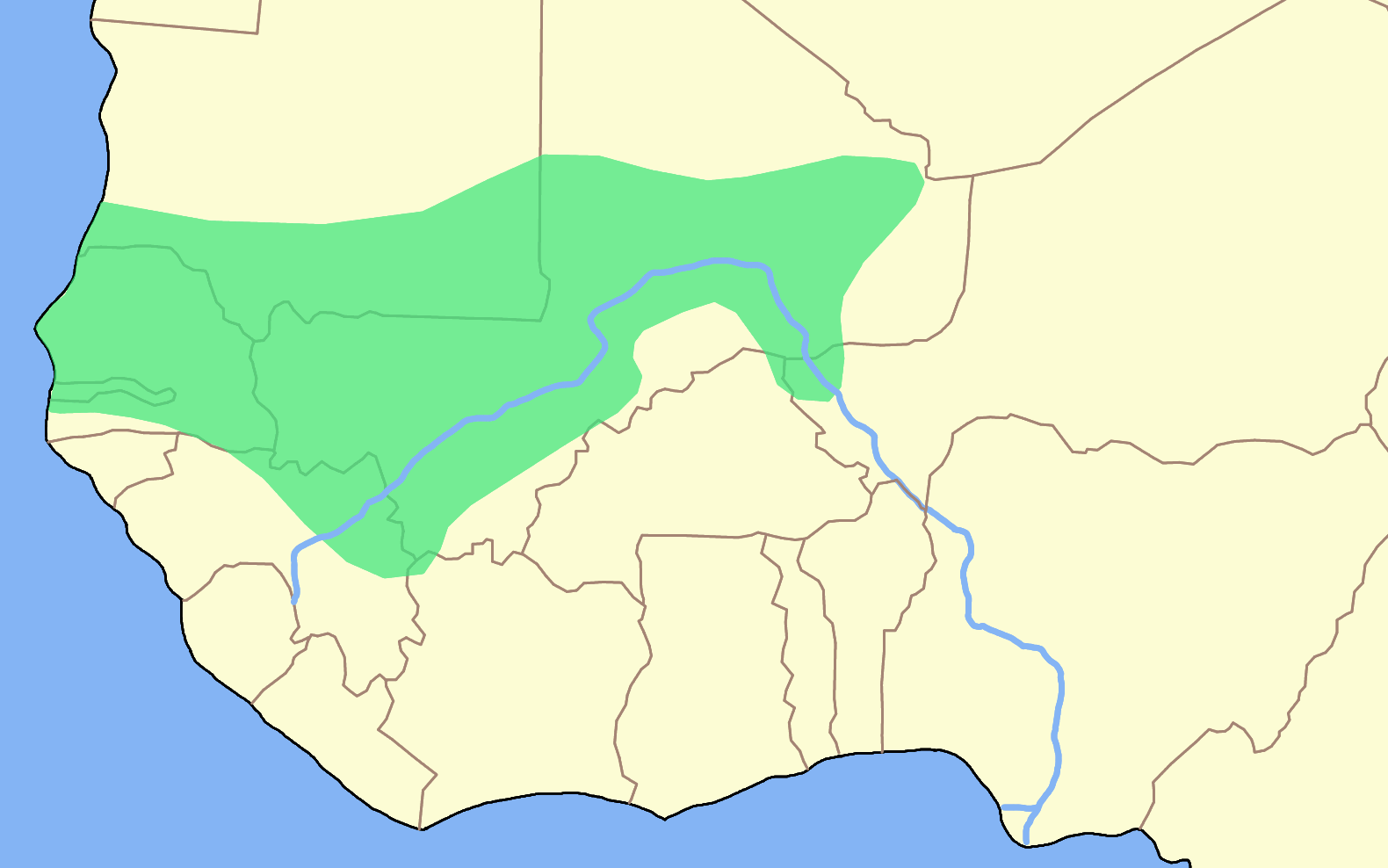

The medieval history of the Sahel is characterized by the consolidation of settlements into large state entities – the

The medieval history of the Sahel is characterized by the consolidation of settlements into large state entities – the Ghana Empire

The Ghana Empire (), also known as simply Ghana, Ghanata, or Wagadu, was an ancient western-Sahelian empire based in the modern-day southeast of Mauritania and western Mali.

It is uncertain among historians when Ghana's ruling dynasty began. T ...

, the Mali Empire

The Mali Empire (Manding languages, Manding: ''Mandé''Ki-Zerbo, Joseph: ''UNESCO General History of Africa, Vol. IV, Abridged Edition: Africa from the Twelfth to the Sixteenth Century'', p. 57. University of California Press, 1997. or ''Manden ...

and the Songhai Empire

The Songhai Empire was a state located in the western part of the Sahel during the 15th and 16th centuries. At its peak, it was one of the largest African empires in history. The state is known by its historiographical name, derived from its lar ...

. The cores of these great empires were located on the territory of the current Republic of Mali, so current-day Senegal occupied a peripheral position.

The earliest of these empires is that of Ghana, probably founded in the first millennium

File:1st millennium montage.png, From top left, clockwise: Depiction of Jesus, the central figure in Christianity; The Colosseum, a landmark of the once-mighty Roman Empire; Kaaba, the Great Mosque of Mecca, the holiest site of Islam; Chess, a ne ...

by Soninke and whose animist

Animism (from meaning 'breath, spirit, life') is the belief that objects, places, and creatures all possess a distinct spiritual essence. Animism perceives all things—animals, plants, rocks, rivers, weather systems, human handiwork, and in ...

populations subsisted by agriculture and trade across the Sahara, including gold, salt and cloth. Its area of influence slowly spread to regions between the river valleys of the Senegal

Senegal, officially the Republic of Senegal, is the westernmost country in West Africa, situated on the Atlantic Ocean coastline. It borders Mauritania to Mauritania–Senegal border, the north, Mali to Mali–Senegal border, the east, Guinea t ...

and Niger

Niger, officially the Republic of the Niger, is a landlocked country in West Africa. It is a unitary state Geography of Niger#Political geography, bordered by Libya to the Libya–Niger border, north-east, Chad to the Chad–Niger border, east ...

.

A contemporary empire of Ghana, but less extensive, the kingdom of Tekrur was its vassal. Ghana and Tekrur were the only organized populations before Islamization. The territory of Tekrur approximates that of the current Fouta Toro. Its existence in the 9th century is attested by Arabic manuscripts. The formation of the state may have taken place as an influx of Fulani from the east settled in the Senegal valley. John Donnelly Fage suggests that Takrur was formed through the interaction of Berbers from the Sahara and "Negro agricultural peoples" who were "essentially Serer" although its kings after 1000 CE might have been Soninke (northern Mande). The name, borrowed from Arabic writings, may be linked to that of the ethnicity Toucouleur. Trade with the Arabs was prevalent. The Kingdom imported wool

Wool is the textile fiber obtained from sheep and other mammals, especially goats, rabbits, and camelids. The term may also refer to inorganic materials, such as mineral wool and glass wool, that have some properties similar to animal w ...

, copper

Copper is a chemical element; it has symbol Cu (from Latin ) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish-orang ...

and pearl

A pearl is a hard, glistening object produced within the soft tissue (specifically the mantle (mollusc), mantle) of a living Exoskeleton, shelled mollusk or another animal, such as fossil conulariids. Just like the shell of a mollusk, a pear ...

s and exported gold and slaves

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

. Indeed, the growth of a vast empire by Arab-Muslim Jihad

''Jihad'' (; ) is an Arabic word that means "exerting", "striving", or "struggling", particularly with a praiseworthy aim. In an Islamic context, it encompasses almost any effort to make personal and social life conform with God in Islam, God ...

s is not devoid of economic and political issues and brought in its wake the first real growth of the slave trade Slave trade may refer to:

* History of slavery - overview of slavery

It may also refer to slave trades in specific countries, areas:

* Al-Andalus slave trade

* Atlantic slave trade

** Brazilian slave trade

** Bristol slave trade

** Danish sl ...

. This trade called the trans-Saharan slave trade

The trans-Saharan slave trade, also known as the Arab slave trade, was a Slavery, slave trade in which slaves Trans-Saharan trade, were mainly transported across the Sahara. Most were moved from sub-Saharan Africa to North Africa to be sold to ...

provided North Africa and Saharan Africa with slave labor. The Tekrur were among the first converts to Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

, certainly before 1040.

Mali Empire

The Mali Empire (Manding languages, Manding: ''Mandé''Ki-Zerbo, Joseph: ''UNESCO General History of Africa, Vol. IV, Abridged Edition: Africa from the Twelfth to the Sixteenth Century'', p. 57. University of California Press, 1997. or ''Manden ...

and the Jolof Empire

The Jolof Empire (), also known as Great Jolof or the Wolof Empire, was a Wolof state in modern-day Senegal, that ruled portions of Mauritania and Gambia from the mid-14th centuryFage, J. D.; Oliver, Roland; "The Cambridge History of Africa." Vo ...

which become the vassal of the first in its heyday. Originating in the Mandinka invasion, Mali continued to expand, encompassing first eastern Senegal, and later almost all the present territory. Founded in the 14th century by the possibly mythical chief of the Wolof Ndiadiane Ndiaye, who was a Serer of Waalo

Waalo () was a kingdom on the lower Senegal River in West Africa, in what is now Senegal and Mauritania. It included parts of the valley proper and areas north and south, extending to the Atlantic Ocean. To the north were Moorish emirates; to the ...

(Ndiaye is originally a Serer surname

which is also found among the Wolof). Djolof expanded its dominance of small chiefdoms south of the Senegal River (Waalo

Waalo () was a kingdom on the lower Senegal River in West Africa, in what is now Senegal and Mauritania. It included parts of the valley proper and areas north and south, extending to the Atlantic Ocean. To the north were Moorish emirates; to the ...

, Cayor

The Cayor Kingdom (; ) was from 1549 to 1876 the largest and most powerful kingdom that split off from the Jolof Empire in what is now Senegal. The Cayor Kingdom was located in northern and central Senegal, southeast of Waalo, west of the kingdom ...

, Baol

Baol or Bawol was a kingdom in what is now central Senegal. Founded in the 11th century, it was a vassal of the Jolof Empire before becoming independent in the mid-16th century. The ruler bore the title of Teigne (title), Teigne (or Teeň) and re ...

, Sine

In mathematics, sine and cosine are trigonometric functions of an angle. The sine and cosine of an acute angle are defined in the context of a right triangle: for the specified angle, its sine is the ratio of the length of the side opposite th ...

– Saloum

The Kingdom of Saloum ( Serer: ''Saluum'' or ''Saalum'') was a Serer kingdom in present-day Senegal and parts of Gambia. The precolonial capital was the city of Kahone. Re-established in 2017, Saloum is now a non-sovereign traditional monarch ...

), bringing together all the Senegambia to which he gave religious and social unity: the "Grand Djolof" which collapsed in 1550.

The Jolof Empire was founded by a voluntary confederacy of States; it was not an empire built on military conquest in spite of what the word "empire" implies. The Serer tradition of Sine attests that the Kingdom of Sine

The Kingdom of Sine (or Siin in Serer, variations: ''Sin'' or ''Siine'') was a post-classical Serer kingdom along the north bank of the Saloum River delta in modern Senegal.

Toponymy and Demonym

During the Guelowar Era the region was named a ...

never paid tribute to Ndiadiane Ndiaye nor to any member of his descendants that ruled Djolof. Historian Sylviane Diouf states that "Each vassal kingdom—Walo, Takrur, Kayor, Baol, Sine, Salum, Wuli, and Niani—recognized the hegemony of Jolof and paid tribute." It went on to state that, Ndiadiane Ndiaye himself received his name from the mouth of Maissa Wali (the King of Sine).Diouf, Niokhobaye. "Chronique du royaume du Sine" par suivie de Notes sur les traditions orales et les sources écrites concernant le royaume du Sine par Charles Becker et Victor Martin. Bulletin de l'Ifan, Tome 34, Série B, n° 4, 1972. p706 In the epics of Ndiadiane and Maissa Wali, it is well acknowledged that Maissa Wali was pivotal in the founding of this Empire. It was he who nominated Ndiadiane Ndiaye and called for the other states to join this confederacy, which they did, and the "empire" headed by Ndiadiane, who took residence at Djolof. It is for this reason scholars propose that the empire was more like a voluntary confederacy than an empire built on military conquest.Charles, Eunice A. Precolonial Senegal: the Jolof Kingdom, 1800–1890. African Studies Center, Boston University, 1977. p 3Ham, Anthony. West Africa. Lonely Planet. 2009. p 670. ()

The arrival of Europeans engendered autonomy of small kingdoms which were under the influence of Djolof. Less dependent on trans-Saharan trade with the new shipping lanes, they turn more readily to trade with the New World

The term "New World" is used to describe the majority of lands of Earth's Western Hemisphere, particularly the Americas, and sometimes Oceania."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: ...

. The decline of these kingdoms can be explained by internal rivalries, then by the arrival of Europeans, who organized the mass exodus of young Africans to the New World. Ghazis, wars, epidemics and famine afflicted the people, along with the Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade or transatlantic slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of Slavery in Africa, enslaved African people to the Americas. European slave ships regularly used the triangular trade route and its Middle Pass ...

, in exchange for weapons and manufactured goods. Under the influence of Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

, these kingdoms were transformed and marabouts played an increasing role.

In Casamance, the Baïnounks, the Manjaques and Diola

The Jola or Diola (endonym: Ajamat) are an ethnic group found in Senegal, the Gambia, and Guinea-Bissau. Most Jola live in small villages scattered throughout southern Senegal, especially in the Lower Casamance region. The main dialect of the J ...

inhabited the coastal area while the mainland – unified 13th century under the name of Kaabu

Kaabu (1537–1867), also written Gabu, Ngabou, and N'Gabu, was a federation of Mandinka kingdoms in the Senegambia region centered within modern northeastern Guinea-Bissau, large parts of today's Gambia, and extending into Koussanar, Kou ...

– was occupied by the Mandingo. In the 15th century, the king of one of the tribes, Kassas gave his name to the region: Kassa Mansa (King of Kassas). Until the French intervention The Casamance was a heterogeneous entity, weakened by internal rivalries.

The era of trading posts and trafficking

According to several ancient sources, including occasions by the ''Dictionnaire de pédagogie et d'instruction primaire'' by Ferdinand Buisson in 1887, the first French settlement in Senegal dates back to theDieppe

Dieppe (; ; or Old Norse ) is a coastal commune in the Seine-Maritime department, Normandy, northern France.

Dieppe is a seaport on the English Channel at the mouth of the river Arques. A regular ferry service runs to Newhaven in England ...

Mariners in the 14th century. Flattering for Norman sailors, this argument gives credence also to the idea of a precedence of the French presence in the region, but it is not confirmed by subsequent work.

In the mid-15th century, several European nations reached the coast of West Africa, vested successively or simultaneously by the Portuguese, the Dutch, the English and French. Europeans first settled along the coasts, on islands in the mouths of rivers and then a little further upstream. They opened trading posts and engaged in the "trade:" – a term which, under the Ancien Régime

''Ancien'' may refer to

* the French word for " ancient, old"

** Société des anciens textes français

* the French for "former, senior"

** Virelai ancien

** Ancien Régime

** Ancien Régime in France

{{disambig ...

, means any type of trade (wheat, pepper, ivory

Ivory is a hard, white material from the tusks (traditionally from elephants) and Tooth, teeth of animals, that consists mainly of dentine, one of the physical structures of teeth and tusks. The chemical structure of the teeth and tusks of mamm ...

...), and not necessarily, or only, the slave trade Slave trade may refer to:

* History of slavery - overview of slavery

It may also refer to slave trades in specific countries, areas:

* Al-Andalus slave trade

* Atlantic slave trade

** Brazilian slave trade

** Bristol slave trade

** Danish sl ...

, although this "infamous traffic", as it was called at the end of the 18th century, was indeed at the heart of a new economic order, controlled by powerful companies in privilege.

The Portuguese navigators

Encouraged by

Encouraged by Henry the Navigator

Princy Henry of Portugal, Duke of Viseu ( Portuguese: ''Infante Dom Henrique''; 4 March 1394 – 13 November 1460), better known as Prince Henry the Navigator (), was a Portuguese prince and a central figure in the early days of the Portuguese ...

and always in search of the Passage to India, and not forgetting gold and slave

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

s, Portuguese explorers explored the African coast and ventured still farther south.

In 1444 Dinis Dias went off the mouth of the Senegal River

The Senegal River ( or "Senegal" - compound of the Serer term "Seen" or "Sene" or "Sen" (from Roog Seen, Supreme Deity in Serer religion) and "O Gal" (meaning "body of water")); , , , ) is a river in West Africa; much of its length mark ...

to reach the westernmost point of Africa he calls ''Cabo Verde'', Cape Vert, because of the lush vegetation seen there. He also reached the island of Gorée

(; "Gorée Island"; ) is one of the 19 (i.e. districts) of the city of Dakar, Senegal. It is an island located at sea from the main harbour of Dakar (), famous as a destination for people interested in the Atlantic slave trade.

Its populatio ...

, referred to by its inhabitants as ''Berzeguiche'', but which he called ''Ilha de Palma'', the island of Palms. The Portuguese did not settle there permanently, but used the site for landing and engaged in commerce in the region. They built a chapel there in 1481. Portuguese trading posts were installed in Tanguegueth in Cayor

The Cayor Kingdom (; ) was from 1549 to 1876 the largest and most powerful kingdom that split off from the Jolof Empire in what is now Senegal. The Cayor Kingdom was located in northern and central Senegal, southeast of Waalo, west of the kingdom ...

, a town they renamed ''Fresco Rio'' (the future Rufisque

Rufisque (; Wolof: Tëngeéj) is a city in the Dakar region of western Senegal, at the base of the Cap-Vert Peninsula east of Dakar, the capital. It has a population of 295,459 (2023 census).

) because of the freshness of its sources in the Baol

Baol or Bawol was a kingdom in what is now central Senegal. Founded in the 11th century, it was a vassal of the Jolof Empire before becoming independent in the mid-16th century. The ruler bore the title of Teigne (title), Teigne (or Teeň) and re ...

Sali (later the seaside town of Saly

Saly (also called Sali or Saly Portudal) is a seaside resort and urban commune in Thiès Region on the Petite Côte of Senegal, south of Dakar. It is a major tourist destination in Senegal.

History

Saly was originally a Portuguese trading post kn ...

) which takes the name of ''Portudal'', or to Joal in the Kingdom of Sine

The Kingdom of Sine (or Siin in Serer, variations: ''Sin'' or ''Siine'') was a post-classical Serer kingdom along the north bank of the Saloum River delta in modern Senegal.

Toponymy and Demonym

During the Guelowar Era the region was named a ...

.

They also traversed the lower Casamance and founded Ziguinchor in 1645. The introduction of Christianity accompanied this business expansion.

The Dutch West India Company

After the Act of Abjuration in 1581, the United Provinces flouted the authority of theKing of Spain

The monarchy of Spain or Spanish monarchy () is the constitutional form of government of Spain. It consists of a Hereditary monarchy, hereditary monarch who reigns as the head of state, being the highest office of the country.

The Spanish ...

. They based their growth on maritime trade and expanded their colonial empire in Asia, the Americas

The Americas, sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North America and South America.''Webster's New World College Dictionary'', 2010 by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Cleveland, Ohio. When viewed as a sing ...

and South Africa. In West Africa trading posts were opened at some points of the current Senegal

Senegal, officially the Republic of Senegal, is the westernmost country in West Africa, situated on the Atlantic Ocean coastline. It borders Mauritania to Mauritania–Senegal border, the north, Mali to Mali–Senegal border, the east, Guinea t ...

, Gambia

The Gambia, officially the Republic of The Gambia, is a country in West Africa. Geographically, The Gambia is the List of African countries by area, smallest country in continental Africa; it is surrounded by Senegal on all sides except for ...

, Ghana

Ghana, officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It is situated along the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, and shares borders with Côte d’Ivoire to the west, Burkina Faso to the north, and Togo to t ...

and Angola

Angola, officially the Republic of Angola, is a country on the west-Central Africa, central coast of Southern Africa. It is the second-largest Portuguese-speaking world, Portuguese-speaking (Lusophone) country in both total area and List of c ...

.

Created in 1621, the

Created in 1621, the Dutch West India Company

The Dutch West India Company () was a Dutch chartered company that was founded in 1621 and went defunct in 1792. Among its founders were Reynier Pauw, Willem Usselincx (1567–1647), and Jessé de Forest (1576–1624). On 3 June 1621, it was gra ...

purchased the island of Gorée

(; "Gorée Island"; ) is one of the 19 (i.e. districts) of the city of Dakar, Senegal. It is an island located at sea from the main harbour of Dakar (), famous as a destination for people interested in the Atlantic slave trade.

Its populatio ...

in 1627. The company built two forts that are in ruins today: in 1628 on the face of Nassau Cove and 1639 at Nassau on the hill, as well as warehouses for goods destined for the mainland trading posts .

In his ''Description of Africa'' (1668), the humanist

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "humanism" ha ...

Dutch Olfert Dapper gives the etymology of the name given to it by his countrymen, ''Goe-ree'' ''Goede Reede'', that is to say "good harbor"., which is the name of (part of) an island in the Dutch province of Zeeland as well.

The Dutch settlers occupied the island for nearly half a century, dealing in wax, amber

Amber is fossilized tree resin. Examples of it have been appreciated for its color and natural beauty since the Neolithic times, and worked as a gemstone since antiquity."Amber" (2004). In Maxine N. Lurie and Marc Mappen (eds.) ''Encyclopedia ...

, gold, ivory

Ivory is a hard, white material from the tusks (traditionally from elephants) and Tooth, teeth of animals, that consists mainly of dentine, one of the physical structures of teeth and tusks. The chemical structure of the teeth and tusks of mamm ...

and also participated in the slave trade Slave trade may refer to:

* History of slavery - overview of slavery

It may also refer to slave trades in specific countries, areas:

* Al-Andalus slave trade

* Atlantic slave trade

** Brazilian slave trade

** Bristol slave trade

** Danish sl ...

, but kept away from foreign trading posts on the coast. The Dutch were dislodged several times: in 1629 by the Portuguese, in 1645 and 1659 by the French and in 1663 by the English.

Against the backdrop of Anglo-French rivalry

The "trade" and the slave trade intensified in the 17th century. In Senegal, the French and British competed mainly on two issues, the island ofGorée

(; "Gorée Island"; ) is one of the 19 (i.e. districts) of the city of Dakar, Senegal. It is an island located at sea from the main harbour of Dakar (), famous as a destination for people interested in the Atlantic slave trade.

Its populatio ...

and St. Louis

St. Louis ( , sometimes referred to as St. Louis City, Saint Louis or STL) is an independent city in the U.S. state of Missouri. It lies near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a populatio ...

. On 10 February 1763 the Treaty of Paris ended the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War, 1756 to 1763, was a Great Power conflict fought primarily in Europe, with significant subsidiary campaigns in North America and South Asia. The protagonists were Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of Prus ...

and reconciled, after three years of negotiations, France, Great Britain and Spain. Great Britain returned the island of Gorée to France. Britain then acquired from France, among many other territories, "the river of Senegal, with forts & trading posts St. Louis, Podor, and Galam and all rights & dependencies of the said River of Senegal.".

Under Louis XIII

Louis XIII (; sometimes called the Just; 27 September 1601 – 14 May 1643) was King of France from 1610 until his death in 1643 and King of Navarre (as Louis II) from 1610 to 1620, when the crown of Navarre was merged with the French crown.

...

and especially Louis XIV

LouisXIV (Louis-Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was King of France from 1643 until his death in 1715. His verified reign of 72 years and 110 days is the List of longest-reign ...

, the privileges were quite extensively granted to certain French shipping lines, which still faced many difficulties. In 1626 Richelieu founded the Norman Company, an association of Dieppe

Dieppe (; ; or Old Norse ) is a coastal commune in the Seine-Maritime department, Normandy, northern France.

Dieppe is a seaport on the English Channel at the mouth of the river Arques. A regular ferry service runs to Newhaven in England ...

and Rouen

Rouen (, ; or ) is a city on the River Seine, in northwestern France. It is in the prefecture of Regions of France, region of Normandy (administrative region), Normandy and the Departments of France, department of Seine-Maritime. Formerly one ...

merchants responsible for the operation in Senegal and the Gambia

The Gambia, officially the Republic of The Gambia, is a country in West Africa. Geographically, The Gambia is the List of African countries by area, smallest country in continental Africa; it is surrounded by Senegal on all sides except for ...

. It was dissolved in 1658 and its assets were acquired by the Company of Cape Vert and Senegal, itself expropriated following the creation by Colbert in 1664 of the French West India Company.

The Company of Senegal was in turn founded by Colbert in 1673. It became the major tool of French colonialism in Senegal, but saddled with debt, it was dissolved 1681 and replaced by another that lasted until 1694, the date of creation of the Royal Company of Senegal, whose director, Andre Brue, would be captured by Lat Sukaabe Fall the Damel of Cayor

The Cayor Kingdom (; ) was from 1549 to 1876 the largest and most powerful kingdom that split off from the Jolof Empire in what is now Senegal. The Cayor Kingdom was located in northern and central Senegal, southeast of Waalo, west of the kingdom ...

and released against ransom in 1701. A third Company of Senegal was founded in 1709 and lasted until 1718. On the British side, the monopoly of trade with Africa was granted to the Royal African Company in 1698.

Grand Master of the naval war of Louis XIV

LouisXIV (Louis-Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was King of France from 1643 until his death in 1715. His verified reign of 72 years and 110 days is the List of longest-reign ...

, Admiral Jean II d'Estrées

Jean may refer to:

People

* Jean (female given name)

* Jean (male given name)

* Jean (surname)

Fictional characters

* Jean Grey, a Marvel Comics character

* Jean Valjean, fictional character in novel ''Les Misérables'' and its adaptations

* J ...

seized Gorée

(; "Gorée Island"; ) is one of the 19 (i.e. districts) of the city of Dakar, Senegal. It is an island located at sea from the main harbour of Dakar (), famous as a destination for people interested in the Atlantic slave trade.

Its populatio ...

on 1 November 1677. The island was taken by the English on 4 February 1693 before being again occupied by the French four months later. In 1698 the Director of the Company of Senegal, Andre Brue, restored the fortifications. But Gorée was again captured by the British in 1758 during the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War, 1756 to 1763, was a Great Power conflict fought primarily in Europe, with significant subsidiary campaigns in North America and South Asia. The protagonists were Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of Prus ...

. However, under the 1763 Treaty of Paris ending the war, although Senegal was given to the British, the island of Gorée was returned to France."His Britannick Majesty shall restore to France the island of Goree in the condition it was in when conquered: and his Most Christian Majesty cedes, in full right, and guaranties to the King of Great Britain the river Senegal, with the forts and factories of St. Lewis, Podor, and Galam, and with all the rights and dependencies of the said river Senegal." – Article X of the Treaty of Paris (1763)

The Treaty of Paris, also known as the Treaty of 1763, was signed on 10 February 1763 by the kingdoms of Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain, Kingdom of France, France and Spanish Empire, Spain, with Kingdom of Portugal, Portugal in agree ...

at Wikisource

Wikisource is an online wiki-based digital library of free-content source text, textual sources operated by the Wikimedia Foundation. Wikisource is the name of the project as a whole; it is also the name for each instance of that project, one f ...

.

The excellent location of St. Louis caught the attention of the English, who occupied it three times, first for a few months in 1693, second during the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War, 1756 to 1763, was a Great Power conflict fought primarily in Europe, with significant subsidiary campaigns in North America and South Asia. The protagonists were Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of Prus ...

from 1758 until it was retaken for the French by Armand Louis de Gontaut

Armand Louis de Gontaut (), duc de Lauzun, later duc de Biron, and usually referred to by historians of the French Revolution simply as Biron (13 April 174731 December 1793), was a French soldier and politician, known for the part he played in t ...

in 1779, and lastly from 1809 to 1816 during the Napoleonic wars.

After the 1763 Treaty of Paris, the British united their colony of The Gambia

The Gambia, officially the Republic of The Gambia, is a country in West Africa. Geographically, The Gambia is the List of African countries by area, smallest country in continental Africa; it is surrounded by Senegal on all sides except for ...

with Senegal into Senegambia

The Senegambia (other names: Senegambia region or Senegambian zone,Barry, Boubacar, ''Senegambia and the Atlantic Slave Trade'', (Editors: David Anderson, Carolyn Brown; trans. Ayi Kwei Armah; contributors: David Anderson, American Council of Le ...

. The British retook Gorée during the Anglo-French War; however, British possession of Gorée was brief.

In 1783 the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was a peace treaty signed on 28 June 1919. As the most important treaty of World War I, it ended the state of war between Germany and most of the Allies of World War I, Allied Powers. It was signed in the Palace ...

returned Senegal to France, and Senegambia was no more.

Nine companies, in succession, received the African monopoly of gum acacia from the French Crown. Seven of them went bankrupt. Among them were the '' Compagnie d’Afrique'' and the '' Compagnie du Sénégal''. The last was the ''Compagnie de la Gomme'' which failed in 1793.

Appointed governor in 1785, Knight Boufflers focuses for two years to enhance the colony, while engaged in the smuggling of gum arabic and gold with signares.

In 1789 the people of St. Louis

St. Louis ( , sometimes referred to as St. Louis City, Saint Louis or STL) is an independent city in the U.S. state of Missouri. It lies near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a populatio ...

wrote a List of Grievances. The same year the French were driven out of Fort St. Joseph in Galam (Gajaaga) and the Kingdom of Galam.

A trading economy

The Europeans were sometimes disappointed because they hoped to find more gold in West Africa, but when the development ofplantation

Plantations are farms specializing in cash crops, usually mainly planting a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. Plantations, centered on a plantation house, grow crops including cotton, cannabis, tob ...

s in the Americas, mainly in the Caribbean, in Brazil and in the south of the United States raised a great need for cheap labor, the area received more attention. The Papacy

The pope is the bishop of Rome and the Head of the Church#Catholic Church, visible head of the worldwide Catholic Church. He is also known as the supreme pontiff, Roman pontiff, or sovereign pontiff. From the 8th century until 1870, the po ...

, who had sometimes opposed slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

, did not condemn it explicitly to the end of the 17th century; in fact the Church

Church may refer to:

Religion

* Church (building), a place/building for Christian religious activities and praying

* Church (congregation), a local congregation of a Christian denomination

* Church service, a formalized period of Christian comm ...

itself has an interest in the colonial system. Traffic of "ebony" was an issue for warriors who traditionally reduced the vanquished to slavery. Some people specialized in the slave trade, for example the Dyula in West Africa. States and kingdoms competed, along with private traders who became much richer in the triangular trade

Triangular trade or triangle trade is trade between three ports or regions. Triangular trade usually evolves when a region has export commodities that are not required in the region from which its major imports come. It has been used to offset ...

(although some shipments resulted in real financial disaster). Politico-military instability in the region was compounded by the slave trade.

The Black Code, enacted in 1685, regulated the trafficking of slaves in the American colonies.

In Senegal, trading posts were established in

The Black Code, enacted in 1685, regulated the trafficking of slaves in the American colonies.

In Senegal, trading posts were established in Gorée

(; "Gorée Island"; ) is one of the 19 (i.e. districts) of the city of Dakar, Senegal. It is an island located at sea from the main harbour of Dakar (), famous as a destination for people interested in the Atlantic slave trade.

Its populatio ...

, St. Louis

St. Louis ( , sometimes referred to as St. Louis City, Saint Louis or STL) is an independent city in the U.S. state of Missouri. It lies near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a populatio ...

, Rufisque

Rufisque (; Wolof: Tëngeéj) is a city in the Dakar region of western Senegal, at the base of the Cap-Vert Peninsula east of Dakar, the capital. It has a population of 295,459 (2023 census).

, Portudal and Joal and the upper valley of the Senegal River

The Senegal River ( or "Senegal" - compound of the Serer term "Seen" or "Sene" or "Sen" (from Roog Seen, Supreme Deity in Serer religion) and "O Gal" (meaning "body of water")); , , , ) is a river in West Africa; much of its length mark ...

, including Fort St. Joseph, in the Kingdom of Galam, was in the 18th century a French engine of trafficking in Senegambia

The Senegambia (other names: Senegambia region or Senegambian zone,Barry, Boubacar, ''Senegambia and the Atlantic Slave Trade'', (Editors: David Anderson, Carolyn Brown; trans. Ayi Kwei Armah; contributors: David Anderson, American Council of Le ...

.

In parallel, a mestizo society develops in St. Louis and Gorée.

Slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

was abolished by the National Convention

The National Convention () was the constituent assembly of the Kingdom of France for one day and the French First Republic for its first three years during the French Revolution, following the two-year National Constituent Assembly and the ...

in 1794, then reinstated by Bonaparte in 1802. The British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

abolished slavery in 1833; in France it was finally abolished in the Second Republic in 1848, under the leadership of Victor Schœlcher

Victor Schœlcher (; 22 July 1804 – 25 December 1893) was a French abolitionist, writer, politician and journalist, best known for his leading role in the End of slavery in France, abolition of slavery in France in 1848, during the French Secon ...

.

The progressive weakening of the colony

In 1815, theCongress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon, Napol ...

condemned slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

. But this would not change much economically for the Africans.

After the departure of Governor Schmaltz (he had taken office at the end of the ''wreck of the Medusa''), Roger Baron particularly encouraged the development of the peanut

The peanut (''Arachis hypogaea''), also known as the groundnut, goober (US), goober pea, pindar (US) or monkey nut (UK), is a legume crop grown mainly for its edible seeds. It is widely grown in the tropics and subtropics by small and large ...

, "the earth pistachio", whose monoculture

In agriculture, monoculture is the practice of growing one crop species in a field at a time. Monocultures increase ease and efficiency in planting, managing, and harvesting crops short-term, often with the help of machinery. However, monocultur ...

would be long because of the severe economic backwardness of Senegal. Despite the ferocity of the Baron, the company was a failure.

The colonization of Casamance also continued. The island of Carabane

Carabane, also known as Karabane, is an island and a village located in the extreme south-west of Senegal, in the mouth of the Casamance River. This relatively recent geological formation consists of a shoal and alluvium to which soil is added b ...

, acquired by France in 1836, was profoundly transformed between 1849 and 1857 by the resident Emmanuel Bertrand Bocandé, a Nantes

Nantes (, ; ; or ; ) is a city in the Loire-Atlantique department of France on the Loire, from the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coast. The city is the List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, sixth largest in France, with a pop ...

businessman.

Modern colonialism

Various European powers – Portugal, the Netherlands, and England – competed for trade in the area from the 15th century onward, until in 1677, France ended up in possession of what had become a minor slave trade departure point—the infamous island ofGorée

(; "Gorée Island"; ) is one of the 19 (i.e. districts) of the city of Dakar, Senegal. It is an island located at sea from the main harbour of Dakar (), famous as a destination for people interested in the Atlantic slave trade.

Its populatio ...

next to modern Dakar

Dakar ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Senegal, largest city of Senegal. The Departments of Senegal, department of Dakar has a population of 1,278,469, and the population of the Dakar metropolitan area was at 4.0 mill ...

."Goree and the Atlantic Slave Trade", Philip Curtin, History Net, accessed 9 July 2008. In 1758 the French settlement was captured by a British expedition as part of the

Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War, 1756 to 1763, was a Great Power conflict fought primarily in Europe, with significant subsidiary campaigns in North America and South Asia. The protagonists were Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of Prus ...

, but was later returned to France. It was only in the 1850s that the French, under the governor, Louis Faidherbe, began to expand their foothold onto the Senegalese mainland, at the expense of the native kingdoms.

The Four Communes of Saint-Louis, Dakar

Dakar ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Senegal, largest city of Senegal. The Departments of Senegal, department of Dakar has a population of 1,278,469, and the population of the Dakar metropolitan area was at 4.0 mill ...

, Gorée

(; "Gorée Island"; ) is one of the 19 (i.e. districts) of the city of Dakar, Senegal. It is an island located at sea from the main harbour of Dakar (), famous as a destination for people interested in the Atlantic slave trade.

Its populatio ...

, and Rufisque

Rufisque (; Wolof: Tëngeéj) is a city in the Dakar region of western Senegal, at the base of the Cap-Vert Peninsula east of Dakar, the capital. It has a population of 295,459 (2023 census).

were the oldest colonial towns in French controlled west Africa. In 1848, the French Second Republic

The French Second Republic ( or ), officially the French Republic (), was the second republican government of France. It existed from 1848 until its dissolution in 1852.

Following the final defeat of Napoleon, Napoleon Bonaparte at the Battle ...

extended the rights of full French citizenship to their inhabitants. While those who were born in these towns could technically enjoy all the rights of native French citizens, substantial legal and social barriers prevented the full exercise of these rights, especially by those seen by authorities as full blooded Africans.

Most of the African population of these towns were termed ''originaires'': those Africans born into the commune, but who retained recourse to African and/or Islamic law (the so-called "personal status"). Those few Africans from the four communes who were able to pursue higher education and were willing to renounce their legal protections could "rise" to be termed Évolué

In the Belgian colonial empire, Belgian and French colonial empires, an (, 'evolved one' or 'developed one') was an African who had been Europeanised through education and cultural assimilation, assimilation and had accepted European values and ...

("Evolved") and were nominally granted full French citizenship, including the vote. Despite this legal framework, Évolués still faced substantial discrimination in Africa and the Metropole alike.

On 27 April 1848, following the February revolution in France, a law was passed in Paris enabling the Four Communes to elect a Deputy to the French Parliament for the first time. On 2 April 1852 the parliamentary seat for Senegal was abolished by Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles-Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was President of France from 1848 to 1852 and then Emperor of the French from 1852 until his deposition in 1870. He was the first president, second emperor, and last ...

. Following the downfall of the French Second Empire

The Second French Empire, officially the French Empire, was the government of France from 1852 to 1870. It was established on 2 December 1852 by Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, president of France under the French Second Republic, who proclaimed hi ...

, the Four Communes was again allowed a parliamentary seat which was granted by law on 1 February 1871. On 30 December 1875 this seat was again abolished, but only for a few years as it was reinstated on 8 April 1879, and remained the single parliamentary representation from sub-Saharan Africa anywhere in a European legislature until the fall of the third republic in 1940.

It was only in 1916 that ''originaires'' were granted full voting rights while maintaining legal protections. Blaise Diagne, who was the prime advocate behind the change, was in 1914 the first African deputy elected to the French National Assembly

The National Assembly (, ) is the lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral French Parliament under the French Fifth Republic, Fifth Republic, the upper house being the Senate (France), Senate (). The National Assembly's legislators are known ...

. From that time until independence in 1960, the deputies of the Four Communes were always African, and were at the forefront of the decolonisation

Decolonization is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby Imperialism, imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. The meanings and applications of the term are disputed. Some scholar ...

struggle.

List of deputies elected to the French Parliament

TheFrench Second Republic

The French Second Republic ( or ), officially the French Republic (), was the second republican government of France. It existed from 1848 until its dissolution in 1852.

Following the final defeat of Napoleon, Napoleon Bonaparte at the Battle ...

:

* Barthélémy Durand Valantin 1848–1850 (Mixed race)

*Vacant 1850–1852

*Abolished 1852–1871

The

The French Third Republic

The French Third Republic (, sometimes written as ) was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 1940, after the Fall of France durin ...

:

* Jean-Baptiste Lafon de Fongauffier 1871–1876 (Mixed race)

*Abolished 1876–1879

* Alfred Gasconi 1879–1889 (Mixed race)

* Aristide Vallon 1889–1893

* Jules Couchard 1893–1898

* Hector D'Agoult 1898–1902

* François Carpot 1902–1914 (Mixed race)

* Blaise Diagne 1914–1934 (African)

* Galandou Diouf 1934–1940 (African)

1945–1959:

* Amadou Lamine Guèye 1945–1951 (African)

* Léopold Sedar Senghor 1945–1959 (African)

* Abbas Guèye 1951–1955 (African)

*Mamadou Dia

Mamadou Dia (18 July 1910 – 25 January 2009) was a Senegalese politician who served as the first Prime Minister of Senegal from 1957 until 1962, when he was forced to resign and was subsequently imprisoned amidst allegations that he was p ...

1956–1959 (African)

Following the 1945 elections to the Constituent Assembly in France, which were held with a very limited franchise, the French authorities gradually extended the franchise until—in November 1955—the principle of universal suffrage

Universal suffrage or universal franchise ensures the right to vote for as many people bound by a government's laws as possible, as supported by the " one person, one vote" principle. For many, the term universal suffrage assumes the exclusion ...

was passed into law and implemented the following year. The first electoral contests held under universal suffrage were the municipal elections of November 1956. The first national contest was the 31 March 1957 election of the Territorial Assembly.

Independence

French Sudan

French Sudan (; ') was a French colonial territory in the Federation of French West Africa from around 1880 until 1959, when it joined the Mali Federation, and then in 1960, when it became the independent state of Mali. The colony was formall ...

merged to form the Mali Federation, which became fully independent on 20 June 1960. The transfer of power agreement with France was signed on 4 April 1960. Due to internal political difficulties, the Federation broke up on 20 August 1960. Senegal and Soudan (renamed the Republic of Mali

Mali, officially the Republic of Mali, is a landlocked country in West Africa. It is the List of African countries by area, eighth-largest country in Africa, with an area of over . The country is bordered to the north by Algeria, to the east b ...

) proclaimed independence. Léopold Senghor, internationally known poet, politician, and statesman, was elected Senegal's first president in August 1960.

The 1960s and early 1970s saw the continued and persistent violating of Senegal's borders by the Portuguese military from Portuguese Guinea

Portuguese Guinea (), called the Overseas Province of Guinea from 1951 until 1972 and then State of Guinea from 1972 until 1974, was a Portuguese overseas province in West Africa from 1588 until 10 September 1974, when it gained independence as G ...

. In response, Senegal petitioned the United Nations Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international peace and security, recommending the admission of new UN members to the General Assembly, an ...

in 1963, 1965

Events January–February

* January 14 – The First Minister of Northern Ireland and the Taoiseach of the Republic of Ireland meet for the first time in 43 years.

* January 20

** Lyndon B. Johnson is Second inauguration of Lynd ...

, 1969 (in response to shelling by Portuguese artillery), 1971 *

The year 1971 had three partial solar eclipses (Solar eclipse of February 25, 1971, February 25, Solar eclipse of July 22, 1971, July 22 and Solar eclipse of August 20, 1971, August 20) and two total lunar eclipses (February 1971 lunar eclip ...

and finally in 1972

Within the context of Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) it was the longest year ever, as two leap seconds were added during this 366-day year, an event which has not since been repeated. (If its start and end are defined using Solar time, ...

.

After the breakup of the Mali Federation, President Senghor and Prime Minister Mamadou Dia

Mamadou Dia (18 July 1910 – 25 January 2009) was a Senegalese politician who served as the first Prime Minister of Senegal from 1957 until 1962, when he was forced to resign and was subsequently imprisoned amidst allegations that he was p ...

governed together under a parliamentary system. In December 1962, their political rivalry led to an attempted coup by Prime Minister Dia. The coup was put down without bloodshed and Dia was arrested and imprisoned. Senegal adopted a new constitution that consolidated the President's power.

Senghor was considerably more tolerant of opposition than most African leaders became in the 1960s. Nonetheless, political activity was somewhat restricted for a time. Senghor's party, the Senegalese Progressive Union (now the Socialist Party of Senegal), was the only legally permitted party from 1965 until 1975. In the latter year, Senghor allowed the formation of two opposition parties that began operation in 1976—a Marxist party (the African Independence Party) and a liberal party (the Senegalese Democratic Party).

In 1980, President Senghor retired from politics, and handed power over to his handpicked successor, Prime Minister Abdou Diouf, in 1981.

1980–present

Senegal joined withThe Gambia

The Gambia, officially the Republic of The Gambia, is a country in West Africa. Geographically, The Gambia is the List of African countries by area, smallest country in continental Africa; it is surrounded by Senegal on all sides except for ...

to form the nominal confederation of Senegambia

The Senegambia (other names: Senegambia region or Senegambian zone,Barry, Boubacar, ''Senegambia and the Atlantic Slave Trade'', (Editors: David Anderson, Carolyn Brown; trans. Ayi Kwei Armah; contributors: David Anderson, American Council of Le ...

on 1 February 1982. However, the envisaged integration of the two countries was never carried out and the union was dissolved in 1989. Despite peace talks, a southern separatist group in the Casamance region has clashed sporadically with government forces since 1982. Senegal has a long history of participating in international peacekeeping.

Abdou Diouf was president between 1981 and 2000. Diouf served four terms as president. In the presidential election of 2000, he was defeated in a free and fair election by opposition leader Abdoulaye Wade

Abdoulaye Wade (, ; born 29 May 1926) is a Senegalese politician who served as the third president of Senegal from 2000 to 2012. He is also the Secretary-General of the Senegalese Democratic Party (PDS), having led the party since it was founded ...

. Senegal experienced its second peaceful transition of power

A peaceful transition or transfer of power is a concept important to democracy, democratic governments in which the leadership of a government peacefully hands over control of government to a newly elected leadership. This may be after elections o ...

and its first from one political party to another.

On 30 December 2004, President Abdoulaye Wade announced that he would sign a peace treaty with two separatist factions of the Movement of Democratic Forces of Casamance (MFDC) in the Casamance region. This will end West Africa's longest-running civil conflict. As of late 2006, it seemed the peace treaty was holding, as both factions and the Senegalese military appeared to honor the treaty. With recognized prospects for peace, refugees

A refugee, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), is a person "forced to flee their own country and seek safety in another country. They are unable to return to their own country because of feared persecution as ...

began returning home from neighboring Guinea-Bissau

Guinea-Bissau, officially the Republic of Guinea-Bissau, is a country in West Africa that covers with an estimated population of 2,026,778. It borders Senegal to Guinea-Bissau–Senegal border, its north and Guinea to Guinea–Guinea-Bissau b ...

. However, at the beginning of 2007, refugees began fleeing again as the sight of Senegalese troops rekindled fears of a new outbreak of violence between the separatists and the government.

Abdoulaye Wade conceded defeat to Macky Sall

Macky Sall (, , ; born 11 December 1961) is a Senegalese politician who served as the fourth president of Senegal from 2012 to 2024. He previously served as the eighth Prime Minister of Senegal, prime minister from 2004 to 2007, under President ...

in the election of 2012. In February 2019, president Macky Sall was re-elected and he won a second term. The length of presidential term was reduced from seven years to five.

In March 2024, Opposition candidate Bassirou Diomaye Faye

Bassirou Diomaye Diakhar Faye (; born 25 March 1980), commonly known mononymously as Diomaye, is a Senegalese politician and former tax official who is serving as the fifth and current president of Senegal since 2024. He is the general secretary ...

won the Senegal’s presidential election

An election is a formal group decision-making process whereby a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold Public administration, public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative d ...

over the candidate of the ruling coalition, becoming the youngest president in Senegal’s history. In December 2024, President Bassirou Diomaye Faye announced that France should shut down its military bases in Senegal. The status of the end of the presence of French forces in Senegal is planned for September 2025.

See also

*Dakarhistory

History is the systematic study of the past, focusing primarily on the Human history, human past. As an academic discipline, it analyses and interprets evidence to construct narratives about what happened and explain why it happened. Some t ...

and timeline

A timeline is a list of events displayed in chronological order. It is typically a graphic design showing a long bar labelled with dates paralleling it, and usually contemporaneous events.

Timelines can use any suitable scale representing t ...

* Four Communes

*French , 1817–1946

*History of Africa

Archaic humans Out of Africa 1, emerged out of Africa between 0.5 and 1.8 million years ago. This was followed by the Recent African origin of modern humans, emergence of anatomically modern humans, modern humans (''Homo sapiens'') in East A ...

* History of West Africa

* Politics of Senegal

*President of Senegal

The president of Senegal () is the head of state of Senegal. In accordance with the 2001 Senegalese constitutional referendum, constitutional reform of 2001 and since a 2016 Senegalese constitutional referendum, referendum that took place on 20 ...

*Prime Minister of Senegal

The prime minister of Senegal () is the head of government of Senegal. The prime minister is appointed by the president of Senegal, who is directly elected for a five-year term. The prime minister, in turn, appoints the Cabinet of Senegal, afte ...

*Saint-Louis history

History is the systematic study of the past, focusing primarily on the Human history, human past. As an academic discipline, it analyses and interprets evidence to construct narratives about what happened and explain why it happened. Some t ...

and timeline

A timeline is a list of events displayed in chronological order. It is typically a graphic design showing a long bar labelled with dates paralleling it, and usually contemporaneous events.

Timelines can use any suitable scale representing t ...

*

References

Further reading

English Language

*Auchnie, Ailsa. ''"The commandement indigène" in Senegal. 1919–1947'', London: SOAS, 1983, 405 pages (Thèse) * *Chafer, Tony. ''The End of Empire in French West Africa: France's Successful Decolonization''. Berg (2002). * Gellar, Sheldon. ''Senegal: an African nation between Islam and the West'' (Boulder: Westview Press, 1982). *Idowu, H. Oludare. ''The Conseil General in Senegal, 1879–1920'', Ibadan: University of Ibadan, 1970 (Thèse) *Leland, Conley Barrows. ''Général Faidherbe, the Maurel and Prom Company, and French Expansion in Senegal'', University of California, Los Angeles, 1974, XXI-t.1, pp. 1–519; t.2, pages 520–976, (thèse) * Nelson, Harold D., et al. ''Area Handbook for Senegal'' (2nd ed. Washington: American University, 1974full text online

411pp; *Robinson Jr, David Wallace ''Faidherbe, Senegal and Islam'', New York, Columbia University, 1965, 104 pages (thèse) * * Wikle, Thomas A., and Dale R. Lightfoot. "Landscapes of the Slave Trade in Senegal and The Gambia", ''Focus on Geography'' (2014) 57#1 pp. 14–24.

French language