The History of

Knoxville, Tennessee

Knoxville is a city in Knox County, Tennessee, United States, and its county seat. It is located on the Tennessee River and had a population of 190,740 at the 2020 United States census. It is the largest city in the East Tennessee Grand Division ...

, began with the establishment of

James White's Fort on the Trans-Appalachian frontier in 1786.

The fort was chosen as the capital of the

Southwest Territory

The Territory South of the River Ohio, more commonly known as the Southwest Territory or the old Southwest Territory, was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 26, 1790, until June 1, 1796, when it was ...

in 1790, and the city, named for Secretary of War

Henry Knox

Henry Knox (July 25, 1750 – October 25, 1806) was an American military officer, politician, bookseller, and a Founding Father of the United States. Knox, born in Boston, became a senior general of the Continental Army during the Revolutionar ...

, was platted the following year.

Knoxville became the first capital of the State of

Tennessee

Tennessee (, ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Kentucky to the north, Virginia to the northeast, North Carolina t ...

in 1796, and grew steadily during the early 19th century as a way station for westward-bound migrants and as a commercial center for nearby mountain communities.

The arrival of the railroad in the 1850s led to a boom in the city's population and commercial activity.

While a Southern city, Knoxville was home to a strong pro-Union element during the secession crisis of the early 1860s, and remained bitterly divided throughout the Civil War.

The city was occupied by Confederate forces until September 1863, when Union forces entered the city unopposed. Confederate forces laid siege to the city later that year, but retreated after failing to breach the city's fortifications during the

Battle of Fort Sanders

The Battle of Fort Sanders was the crucial engagement of the Knoxville Campaign of the American Civil War, fought in Knoxville, Tennessee, on November 29, 1863. Assaults by Confederate Lt. Gen. James Longstreet failed to break through the def ...

.

Following the war, business leaders, many from the North, established major iron and textile industries in Knoxville. As a nexus between rural towns in Southern Appalachia and the nation's great manufacturing centers, Knoxville grew to become the third-largest wholesaling center in the South.

Tennessee marble

Tennessee marble is a type of crystalline limestone found only in East Tennessee, in the southeastern United States. Long esteemed by architects and builders for its pinkish-gray color and the ease with which it is polished, the stone has been use ...

, extracted from quarries on the city's periphery, was used in the construction of numerous monumental buildings across the country, earning Knoxville the nickname, "The Marble City."

Knoxville's economy slowed in the early 1900s. Political factioning hampered revitalization efforts throughout much of the 20th century, though the creation of federal entities such as the

Tennessee Valley Authority

The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) is a federally owned electric utility corporation in the United States. TVA's service area covers all of Tennessee, portions of Alabama, Mississippi, and Kentucky, and small areas of Georgia, North Carolin ...

in the 1930s and the ten-fold expansion of the

University of Tennessee

The University of Tennessee, Knoxville (or The University of Tennessee; UT; UT Knoxville; or colloquially UTK or Tennessee) is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Knoxville, Tennessee, United St ...

helped keep the economy stable. Beginning in the late 1960s, a city council more open to change, along with economic diversification, urban renewal, and the hosting of the

1982 World's Fair

The 1982 World's Fair, officially known as the Knoxville International Energy Exposition (KIEE) and simply as Energy Expo '82 and Expo '82, was an international exposition held in Knoxville, Tennessee, Knoxville, Tennessee, United States. Focu ...

, helped the city revitalize to some extent.

[W. Bruce Wheeler]

Knoxville

''Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture'', 2009. Retrieved: 17 August 2011.

Prehistory and early recorded history

Native Americans

The first humans to form substantial settlements in what is now Knoxville arrived during the

Woodland period

In the classification of :category:Archaeological cultures of North America, archaeological cultures of North America, the Woodland period of North American pre-Columbian cultures spanned a period from roughly 1000 BC to European contact i ...

(c. 1000 B.C. – 1000 A.D).

[Fletcher Jolly III, "40KN37: An Early Woodland Habitation Site in Knox County, Tennessee", ''Tennessee Archaeologist'' 31, nos. 1-2 (1976), 51.] Knoxville's two most prominent prehistoric structures are Late Woodland period burial mounds, one located along Cherokee Boulevard in

Sequoyah Hills

Sequoyah Hills is a neighborhood in Knoxville, Tennessee, United States, named for the Cherokee scholar Sequoyah.[University of Tennessee

The University of Tennessee, Knoxville (or The University of Tennessee; UT; UT Knoxville; or colloquially UTK or Tennessee) is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Knoxville, Tennessee, United St ...]

campus. Substantial

Mississippian period (c. 1100–1600 A.D.) village sites have been found at Post Oak Island (along the river near the Knox-Blount line), and at

Bussell Island (near

Lenoir City).

The Spanish expedition of

Hernando de Soto

Hernando de Soto (; ; 1497 – 21 May 1542) was a Spanish explorer and conquistador who was involved in expeditions in Nicaragua and the Yucatan Peninsula. He played an important role in Francisco Pizarro's conquest of the Inca Empire in Peru, ...

is believed to have traveled down the

French Broad Valley and visited the Bussell Island village in 1540 en route to the

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the main stem, primary river of the largest drainage basin in the United States. It is the second-longest river in the United States, behind only the Missouri River, Missouri. From its traditional source of Lake Ita ...

. A follow-up expedition led by

Juan Pardo may have visited village sites in the

Little Tennessee Valley in 1567. The records of these two expeditions suggest the area was part of a Muskogean chiefdom known as

Chiaha

Chiaha was a Native American chiefdom located in the lower French Broad River valley in modern East Tennessee, in the southeastern United States. They lived in raised structures within boundaries of several stable villages. These overlooked the ...

, which was subject to the

Coosa chiefdom

The Coosa Chiefdom was a powerful Native American paramount chiefdom in what are now Gordon and Murray counties in Georgia, in the United States.[Cherokee

The Cherokee (; , or ) people are one of the Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, they were concentrated in their homelands, in towns along river valleys of what is now southwestern ...]

had become the dominant tribe in the East Tennessee region, although they were consistently at war with the

Creeks and

Shawnee

The Shawnee ( ) are a Native American people of the Northeastern Woodlands. Their language, Shawnee, is an Algonquian language.

Their precontact homeland was likely centered in southern Ohio. In the 17th century, they dispersed through Ohi ...

. The Cherokee people called the Knoxville area ''kuwanda'talun'yi'', which means "Mulberry Place." Most Cherokee habitation in the area was concentrated in the

Overhill settlements along the Little Tennessee River, southwest of Knoxville.

Early Exploration and late-18th Century Politics

By the early 1700s, traders from

South Carolina

South Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders North Carolina to the north and northeast, the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast, and Georgia (U.S. state), Georg ...

were visiting the Overhill towns regularly, and following the discovery of

Cumberland Gap

The Cumberland Gap is a Mountain pass, pass in the Eastern United States, eastern United States through the long ridge of the Cumberland Mountains, within the Appalachian Mountains and near the tripoint of Kentucky, Virginia, and Tennessee. At&n ...

in 1748,

long hunters from Virginia began pouring into the Tennessee Valley. At the outbreak of the

French and Indian War

The French and Indian War, 1754 to 1763, was a colonial conflict in North America between Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of France, France, along with their respective Native Americans in the United States, Native American ...

in 1754, the Cherokee supported the

British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

, who in return constructed

Fort Loudoun in 1756 to protect the Overhill towns from the French and their allies.

During the

Anglo-Cherokee War

The Anglo-Cherokee War (1758–1761; in the Cherokee language: the ''"war with those in the red coats"'' or ''"War with the English"''), was also known from the Anglo-European perspective as the Cherokee War, the Cherokee Uprising, or the Cherok ...

, however, the Cherokee attacked the fort and killed its occupants in 1760. A peace expedition to the Overhill towns led by

Henry Timberlake

Henry Timberlake (1730 or 1735 – September 30, 1765) was a colonial Anglo-American officer, journalist, and cartographer. He was born in the Colony of Virginia and died in England. He is best known for his work as an emissary from the Briti ...

passed along the river through what is now Knoxville in December 1761.

The Cherokee supported the British during the

Revolutionary War, and after the end of the war,

North Carolina

North Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, South Carolina to the south, Georgia (U.S. stat ...

, which considered the Tennessee Valley part of its territory, deemed Cherokee claims to the region void.

North Carolina made plans to cede its Trans-Appalachian territory to the federal government, but decided to open up the lands to settlement first. In 1783, land speculator

William Blount

William Blount ( ; April 6, 1749March 21, 1800) was an American politician, landowner and Founding Father who was one of the signers of the Constitution of the United States. He was a member of the North Carolina delegation at the Constitution ...

and his brother, John Gray Blount, convinced North Carolina to pass a law offering lands in the Tennessee Valley for sale.

[Stanley Folmsbee and Lucile Deaderick, "The Founding of Knoxville," East Tennessee Historical Society ''Publications'', Vol. 13 (1941), pp. 3-20.] Later that year, an expedition consisting of

James White (1747–1820), James Connor, Robert Love, and Francis Alexander Ramsey, explored the Upper Tennessee Valley, and discovered the future site of Knoxville.

Taking advantage of Blount's land-grab act, White took out a claim for the site shortly afterward.

Early Knoxville

White's Fort

In 1786, White moved to the future site of Knoxville, where he and fellow explorer James Connor built what became known as White's Fort.

The site straddled a hill that was bounded by the river on the south, creeks (First Creek and Second Creek) on the east and west, and a swampy declivity on the north. The fort, which originally stood along modern State Street, consisted of four heavily timbered cabins connected by an palisade, enclosing one-quarter acre of ground.

[J.G.M. Ramsey, ''The Annals of Tennessee to the End of the Eighteenth Century'' (Johnson City, Tenn.: Overmountain Press, 1999).] White also erected a mill for grinding grain on nearby First Creek.

White's Fort represented the western extreme of the so-called

State of Franklin

The State of Franklin (also the Free Republic of Franklin, Lost State of Franklin, or the State of Frankland) was an unrecognized proposed U.S. state, state located in present-day East Tennessee, in the United States. Franklin was created in ...

, which Tennessee settlers organized in 1784 after North Carolina reneged on its plans to cede its western territory to the federal government.

James White supported the State of Franklin, and served as its Speaker of the Senate in 1786. The federal government never recognized the State of Franklin, however, and by 1789, its supporters once again pledged allegiance to North Carolina.

[William MacArthur, Lucile Deaderick (ed.), "Knoxville's History: An Interpretation," ''Heart of the Valley: A History of Knoxville, Tennessee'' (Knoxville, Tenn.: East Tennessee Historical Society, 1976).]

In 1789, White, William Blount, and former State of Franklin leader

John Sevier

John Sevier (September 23, 1745 September 24, 1815) was an American soldier, frontiersman, and politician, and one of the founding fathers of the State of Tennessee. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, he played a leading role in Tennes ...

, now members of the North Carolina state legislature, helped convince the state to ratify the United States Constitution.

Following ratification, North Carolina ceded control of its Tennessee territory to the federal government.

In May 1790, the United States created the

Southwest Territory

The Territory South of the River Ohio, more commonly known as the Southwest Territory or the old Southwest Territory, was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 26, 1790, until June 1, 1796, when it was ...

, which included Tennessee, and President

George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

appointed Blount the territory's governor.

Establishment of Knoxville

Blount immediately moved to White's Fort (chosen for its central location) to begin resolving land disputes between the Cherokee and white settlers in the region.

In the Summer of 1791, he met with forty-one Cherokee chiefs at the mouth of First Creek to negotiate the Treaty of Holston, which was signed on July 2 of that year.

The treaty moved the boundary of Cherokee lands westward to the

Clinch River

The Clinch River is a river that flows southwest for more than through the Great Appalachian Valley in the U.S. states of Virginia and Tennessee, gathering various tributaries, including the Powell River, before joining the Tennessee River in ...

and southwestward to the

Little Tennessee River

The Little Tennessee River (known locally as the Little T) is a tributary of the Tennessee River that flows through the Blue Ridge Mountains from Georgia, into North Carolina, and then into Tennessee, in the southeastern United States. It dra ...

.

While Blount initially sought to place the territorial capital at the confluence of the Clinch and Tennessee rivers (near modern

Kingston

Kingston may refer to:

Places

* List of places called Kingston, including the six most populated:

** Kingston, Jamaica

** Kingston upon Hull, England

** City of Kingston, Victoria, Australia

** Kingston, Ontario, Canada

** Kingston upon Thames, ...

), where he had land claims, he was unable to convince the Cherokee to completely relinquish this area, and thus settled on White's Fort as the capital.

James White set aside land for a new town, which initially consisted of the area now bounded by Church Avenue, Walnut Street, First Creek, and the river, in what is now Downtown Knoxville. White's son-in-law,

Charles McClung

Charles McClung (May 13, 1761August 9, 1835) was an American pioneer, politician, and surveyor best known for drawing up the original plat of Knoxville, Tennessee, in 1791. While Knoxville has since expanded to many times its original size, the ...

, surveyed the land and divided it into 64 half-acre lots.

Lots were set aside for a church and cemetery, a courthouse, a jail, and a college.

On October 3, 1791, a lottery was held for those wishing to purchase lots in the new city, which was named "Knoxville" in honor of Blount's superior, Secretary of War Henry Knox.

Along with Blount and McClung, those who purchased lots in the city included merchants Hugh Dunlap, Thomas Humes, and Nathaniel and Samuel Cowan, newspaper publisher George Roulstone, the Reverend

Samuel Carrick

Samuel Czar Carrick (July 17, 1760 – August 17, 1809) was an American Presbyterian minister who was the first president of Blount College, the educational institution to which the University of Tennessee traces its origin. Milton M. KleinUT's ...

, frontiersman John Adair (who had built a fort just to the north in what is now

Fountain City), and tavern keeper John Chisholm.

Knoxville in the 1790s

Following the sale of lots, Knoxville's leaders set about constructing a courthouse and jail. A garrison of federal soldiers, under the command of David Henley, erected a blockhouse in Knoxville in 1792.

The Cowan brothers, Nathaniel and Samuel, opened the city's first general store in August 1792, and John Chisholm's tavern was in operation by December 1792.

The city's first newspaper, the ''

Knoxville Gazette

The ''Knoxville Gazette'' was the first newspaper published in the U.S. state of Tennessee and the third published west of the Appalachian Mountains. Established by George Roulstone (1767–1804) at the urging of Southwest Territory governor W ...

'', was established by George Roulstone in November 1791.

In 1794, Blount College, the forerunner of the

University of Tennessee

The University of Tennessee, Knoxville (or The University of Tennessee; UT; UT Knoxville; or colloquially UTK or Tennessee) is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Knoxville, Tennessee, United St ...

, was chartered, with Samuel Carrick as its first president.

Carrick also established the city's first church, the First Presbyterian Church, though a building wasn't constructed until 1816.

In many ways, early Knoxville was a typical rowdy late-18th century frontier village.

A detached group of Cherokee, known as the Chickamaugas, refused to recognize the Holston treaty, and remained a constant threat. In September 1793, a large force of Chickamaugas and Creeks marched on Knoxville, and massacred the inhabitants of Cavet's Station (near modern

Bearden) before dispersing.

Outlaws roamed the city's periphery, among them the

Harpe Brothers

Micajah "Big" Harpe, born Joshua Harper (before 1768 – August 24, 1799), and Wiley "Little" Harpe, born William Harper (before 1770 – February 8, 1804), were American murderers, highwaymen and river pirates who operated in Tennessee, Kentu ...

, who murdered at least one settler in 1797 before fleeing to Kentucky.

Abishai Thomas, an associate of Blount who visited Knoxville in 1794, noted that the city was full of taverns and tippling houses, no churches, and that the blockhouse's jail was overcrowded with criminals.

In 1795, James White set aside more land for the growing city, allowing it to expand northward to modern Clinch Avenue and westward to modern Henley Street.

[Samuel Heiskell, ''Andrew Jackson and Early Tennessee History'' (Nashville: Ambrose Publishing Company, 1918), pp. 46-81.] A census that year showed that Tennessee had a large enough population to apply for statehood. In January 1796, delegates from across Tennessee, including Blount, Sevier, and

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before Presidency of Andrew Jackson, his presidency, he rose to fame as a general in the U.S. Army and served in both houses ...

, convened in Knoxville to draw up a constitution for the new state, which was admitted to the Union on June 1, 1796. Knoxville was chosen as the initial capital of the state.

Antebellum Knoxville

Frontier Capital

While Knoxville's population grew steadily in the early 1800s, most new arrivals were westward-bound migrants staying in the town for a brief period.

By 1807, some 200 migrants were passing through the town every day.

Cattle drovers, who specialized in driving herds of cattle across the mountains to markets in South Carolina, were also frequent visitors to the city.

The city's merchants acquired goods from Baltimore and Philadelphia via wagon trains.

French botanist

André Michaux

André Michaux (' → ahn- mee-; sometimes Anglicisation, anglicised as Andrew Michaud; 8 March 174611 October 1802) was a French botanist and explorer. He is most noted for his study of North American flora. In addition Michaux collected specime ...

visited Knoxville in 1802, and reported the presence of approximately 100 houses and 10 "well-stocked" stores. While there was "brisk commerce" at the city's stores, Michaux noted, the only industries in the city were tanneries and blacksmiths. In February 1804, itinerant Methodist preacher

Lorenzo Dow

Lorenzo Dow (October 16, 1777February 2, 1834) was an eccentric itinerant American evangelist, said to have preached to more people than any other preacher of his era. He became an important figure and a popular writer. His autobiography at one ...

passed through Knoxville, and reported the widespread presence of a religious phenomenon in which worshippers would fall to the ground and go into seizure-like convulsions, or "jerks," at religious rallies. Illinois governor

John Reynolds, who studied law in Knoxville, recalled a raucous, anti-British celebration held in the city on July 4, 1812, at the onset of the

War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

.

On October 27, 1815, Knoxville officially incorporated as a city.

The city's new charter set up an alderman-mayor form of government, in which a Board of Aldermen was popularly elected, and in turn selected a mayor from one of their own.

This remained Knoxville's style of government until the early 20th century, though the city's charter was amended in 1838 to allow for popular election of mayor as well.

In January 1816, Knoxville's newly elected Board of Aldermen chose Judge

Thomas Emmerson

Thomas Emmerson (June 23, 1773 – July 22, 1837) was an American judge and newspaper editor, active in the early 19th century. He was a justice of the Tennessee Superior Court of Law and Equity (1807) and the Tennessee Court of Errors and Ap ...

(1773–1837) as the city's first mayor.

With the exceptions of the years 1802, 1807, 1811 and 1812, Knoxville remained the capital of Tennessee until 1817 when the state legislature was moved to

Murfreesboro

Murfreesboro is a city in Rutherford County, Tennessee, United States, and its county seat. Its population was 165,430 according to the 2023 census estimate, up from 108,755 residents certified in 2010 United States census, 2010. Murfreesboro i ...

.

Sectionalism and Struggles with Isolation

Historian William MacArthur once described Knoxville as a "product and prisoner of its environment."

Throughout the first half of the 19th century, Knoxville's economic growth was stunted by its isolation. The rugged terrain of the Appalachian Mountains made travel in and out of the city by road difficult, with wagon trips to Philadelphia or Baltimore requiring a round trip of several months.

Flatboat

A flatboat (or broadhorn) was a rectangular flat-bottomed boat with square ends used to transport freight and passengers on inland waterways in the United States. The flatboat could be any size, but essentially it was a large, sturdy tub with a ...

s were in use as early as 1795 to carry goods from Knoxville to New Orleans via the Tennessee,

Ohio

Ohio ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Erie to the north, Pennsylvania to the east, West Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Indiana to the ...

, and

Mississippi

Mississippi ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Alabama to the east, the Gulf of Mexico to the south, Louisiana to the s ...

rivers,

[Stanley Folmsbee, Mary Rothrock (ed.), "Transportation Prior to the Civil War," ''The French Broad-Holston Country: A History of Knox County, Tennessee'' (Knoxville, Tenn.: East Tennessee Historical Society, 1972).] but river hazards near

Muscle Shoals

Muscle Shoals is the largest city in Colbert County, Alabama, United States. It is located on the left bank of the Tennessee River in the northern part of the state and, as of the 2010 census, its population was 13,146. The estimated popula ...

and Chattanooga made such a trek risky.

During the 1790s, several roads, many of which followed old Indian trails, were constructed that connected Knoxville to other settlements across East Tennessee. The first of these roads to be constructed was

Kingston Pike

Kingston Pike is a highway in Knox County, Tennessee, United States, that connects Downtown Knoxville with West Knoxville, Farragut, and other communities in the western part of the county. The road follows a merged stretch of U.S. Route&nb ...

which was laid out by Charles McClung in 1792. Beginning around 1810,

stagecoach

A stagecoach (also: stage coach, stage, road coach, ) is a four-wheeled public transport coach used to carry paying passengers and light packages on journeys long enough to need a change of horses. It is strongly sprung and generally drawn by ...

service was introduced to Knoxville and continued to operate prior to the Civil War. Known as the "Great Western Line," the route ran westward from

Raleigh, North Carolina

Raleigh ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of North Carolina. It is the List of municipalities in North Carolina, second-most populous city in the state (after Charlotte, North Carolina, Charlotte) ...

, over the mountains to Knoxville, and then continued west to

Nashville

Nashville, often known as Music City, is the capital and List of municipalities in Tennessee, most populous city in the U.S. state of Tennessee. It is the county seat, seat of Davidson County, Tennessee, Davidson County in Middle Tennessee, locat ...

. Although the introduction of stagecoach service somewhat helped to break Knoxville's boundaries of isolation, the trips were often long and rough.

During the 1820s and 1830s, state legislators from East Tennessee continuously bickered with legislators from Middle and West Tennessee over funding for road and navigational improvements. East Tennesseans felt the state had squandered the proceeds from the sale of land in the Hiwassee District (1819) on a failed state bank, rather than on badly needed

internal improvements

Internal improvements is the term used historically in the United States for public works from the end of the American Revolution through much of the 19th century, mainly for the creation of a transportation infrastructure: roads, turnpikes, can ...

.

[Stanley Folmsbee, ''Sectionalism and Internal Improvements in Tennessee, 1796-1845'' (Knoxville, Tenn.: East Tennessee Historical Society, 1939), pp. 28-32, 54-55, 83-86, 132, 161.] It wasn't until 1828 that a

steamboat

A steamboat is a boat that is marine propulsion, propelled primarily by marine steam engine, steam power, typically driving propellers or Paddle steamer, paddlewheels. The term ''steamboat'' is used to refer to small steam-powered vessels worki ...

, the ''Atlas'', managed to navigate Muscle Shoals and make it upriver to Knoxville. River improvements in the 1830s allowed Knoxville semi-annual access to the Mississippi, though by this time the city's merchants had shifted their focus to railroad construction.

Life in Knoxville, 1816–1854

In 1816, as the ''Gazette'' was in decline, businessmen

Frederick Heiskell

Frederick Steidinger Heiskell (1786 – November 29, 1882) was an American newspaper publisher, politician, and civic leader, active primarily in Knoxville, Tennessee, throughout much of the 19th century. He cofounded the ''Knoxville Register ...

and Hugh Brown established a newspaper, the ''

Knoxville Register

The ''Knoxville Register'' was an American newspaper published primarily in Knoxville, Tennessee, during the 19th century. Founded in 1816, the paper was East Tennessee's dominant newspaper until 1863, when its pro-secession editor, Jacob Austin Sp ...

''. Along with the ''Register'', Heiskell and Brown published a pro-emancipation newsletter, the ''Western Monitor and Religious Observer'', as well as books such as John Haywood's ''Civil and Political History of the State of Tennessee'' (1823), one of the state's first comprehensive histories.

The ''Register'' celebrated the move of East Tennessee College (the new name of Blount College following its rechartering in 1807) to Barbara Hill in 1826, and encouraged the trustees of the

Knoxville Female Academy, which had been chartered in 1811, to finally hire a faculty and hold its first classes in 1827.

In the April 1839 issue of the ''Southern Literary Messenger'', a traveler who had recently visited Knoxville described the people of the city as "moral, sociable and hospitable," but "with less refinement of mind and manners" than people in older towns. In 1842, English travel writer James Gray Smith reported that the city was home to a university, an academy, a "ladies' school," three churches, two banks, two hotels, 25-30 stores, and several "handsome country residences" occupied by people "as aristocratic as even an Englishman... could possibly desire."

In 1816, merchant Thomas Humes began building a lavish hotel on Gay Street, later known as the

Lamar House Hotel, which for decades would provide a gathering place for the city's elite. In 1848, the

Tennessee School for the Deaf opened in Knoxville, giving an important boost to the city's economy. In 1854, land speculators

Joseph Mabry and

William Swan donated land for the creation of

Market Square

A market square (also known as a market place) is an urban square meant for trading, in which a market is held. It is an important feature of many towns and cities around the world. A market square is an open area where market stalls are tradit ...

, creating a venue for farmers from the surrounding region to sell their produce.

[Jack Neely, ''Market Square: A History of the Most Democratic Place on Earth'' (Knoxville, Tenn.: Market Square District Association, 2009).]

Arrival of the Railroads

As early as the 1820s, Knoxville's business leaders viewed railroads— then a relatively new form of transportation— as a solution to the city's economic isolation. Led by banker

J. G. M. Ramsey (1797–1884), Knoxville business leaders joined calls to build a rail line connecting the city to

Cincinnati, Ohio

Cincinnati ( ; colloquially nicknamed Cincy) is a city in Hamilton County, Ohio, United States, and its county seat. Settled in 1788, the city is located on the northern side of the confluence of the Licking River (Kentucky), Licking and Ohio Ri ...

to the north and

Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the List of municipalities in South Carolina, most populous city in the U.S. state of South Carolina. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint of South Carolina's coastline on Charleston Harbor, an inlet of the Atla ...

to the southeast, which led to the chartering of the Louisville, Cincinnati and Charleston Railroad (LC&C) in 1836.

The Hiwassee Railroad, chartered two years later, was to connect this line with a rail line in

Dalton, Georgia

Dalton is a city and the county seat of Whitfield County, Georgia, Whitfield County, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia, United States. It is also the principal city of the Dalton metropolitan area, Dalton Metropolitan Statistical Area, which encomp ...

.

In spite of Knoxvillians' enthusiasm (the city celebrated the passage of a state appropriations bill for the LC&C with a 56-gun salute in 1837), the LC&C was doomed by a financial recession in the late 1830s, and construction of the Hiwassee Railroad was stalled by lack of funding amidst continued sectional bickering.

The Hiwassee was rechartered as the

East Tennessee and Georgia Railroad

The East Tennessee and Georgia Railroad Company was incorporated under special act of Tennessee on February 19, 1836 as the Hiwassee Rail Road Company.Interstate Commerce Commission. ''Southern Ry. Co.'', Volume 37, Interstate Commerce Commission ...

in 1847, and construction finally began the following year. The first train rolled into Knoxville on June 22, 1855, to great fanfare.

With the arrival of the railroad, Knoxville expanded rapidly. The city's northern boundary extended northward to absorb the tracks, and its population grew from about 2,000 in 1850 to over 5,000 in 1860.

Local crop prices spiked, the number of wholesaling firms in Knoxville grew from 4 to 14,

[Robert McKenzie, ''Lincolnites and Rebels: A Divided Town in the American Civil War'' (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006).] and two new factories— the Knoxville Manufacturing Company, which made steam engines, and Shepard, Leeds and Hoyt, which built railroad cars— were established.

In 1859, the city had four hotels, at least seven factories, six churches, three newspapers, four banks, and over 45 stores.

Secession crisis in Knoxville

Antebellum Politics in Knoxville

Early-19th century Knoxville was often caught in the middle of the sectionalist fighting between East Tennessee and the state as a whole.

Following the presidential election of 1836, in which Knoxvillian

Hugh Lawson White

Hugh Lawson White (October 30, 1773April 10, 1840) was an American politician during the first third of the 19th century. After filling in several posts particularly in Tennessee's judiciary and state legislature since 1801, thereunder as a Tenn ...

(James White's son) ran against

Andrew Jackson's hand-picked successor,

Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was the eighth president of the United States, serving from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he served as Attorney General o ...

, political divisions in the city manifested along Whig (anti-Jackson) and Democratic party lines.

In 1839, W.B.A. Ramsey won the city's first popular mayoral election by a single vote, illustrating how strong these divisions had become.

[Aelred Gray and Susan Adams, Lucile Deaderick (ed.), "Government," ''Heart of the Valley: A History of Knoxville, Tennessee'' (Knoxville, Tenn.: East Tennessee Historical Society, 1976).]

In 1849,

William G. "Parson" Brownlow moved his radical Whig newspaper, the ''

Whig'', to Knoxville. Brownlow's editorial style, which often involved vicious personal attacks, intensified the already-sharp political divisions within the city. In 1857, he quarreled with the pro-Secession ''Southern Citizen'' and its publishers, Knoxville businessman William G. Swan and Irish Patriot John Mitchell (then in exile), to the point of threatening Swan with a pistol.

[E. Merton Coulter, ''William G. Brownlow: Fighting Parson of the Southern Highlands'' (Knoxville, Tenn.: University of Tennessee Press, 1999).] Brownlow's attacks drove Whig-turned-Democrat

John Hervey Crozier from public life,

[William Gannaway Brownlow, ''Sketches of the Rise, Progress, and Decline of Secession'' (Philadelphia: G.W. Childs, 1862).] and forced two directors of the failed Bank of East Tennessee, A.R. Crozier and William Churchwell, to flee town. He brought charges of swindling against a third director, J.G.M. Ramsey, the former railroad promoter and a staunch Democrat.

Following the nationwide collapse of the Whig Party in 1854, many of Knoxville's Whigs, including Brownlow, were unwilling to support the new Republican Party formed by northern Whigs, and instead aligned themselves with the anti-immigrant American Party (commonly called the "

Know Nothing

The American Party, known as the Native American Party before 1855 and colloquially referred to as the Know Nothings, or the Know Nothing Party, was an Old Stock Americans, Old Stock Nativism in United States politics, nativist political movem ...

s").

When this movement disintegrated, Knoxville's ex-Whigs turned to the

Opposition Party

In politics, the opposition comprises one or more political parties or other organized groups that are opposed to the government (or, in American English, the administration), party or group in political control of a city, region, state, coun ...

. In 1858, Opposition Party candidate

Horace Maynard

Horace Maynard (August 30, 1814 – May 3, 1882) was an American educator, attorney, politician and diplomat active primarily in the second half of the 19th century. Initially elected to the House of Representatives from Tennessee's 2nd Cong ...

, with Brownlow's endorsement, soundly defeated Democratic candidate J.C. Ramsey (J.G.M. Ramsey's son) for the 2nd district's congressional seat.

Knoxville and Slavery

By 1860, slaves comprised 22% of Knoxville's population, which was higher than the percentage across East Tennessee (approximately 10%) but lower than the rest of the South (about one-third).

[C. E. Allred, et al., "Farming From the Beginning to 1860," ''The French Broad-Holston Country: A History of Knox County, Tennessee'' (Knoxville, Tenn.: East Tennessee Historical Society, 1972).] Most of Knox County's farms were small (only one was larger than ) and typically focused on livestock or other products that weren't labor-intensive.

The city was home to a chapter of the American Colonization Society,

led by St. John's Episcopal Church rector

Thomas William Humes

Thomas William Humes (April 22, 1815 – January 16, 1892) was an American clergyman and educator, active in Knoxville, Tennessee, during the latter half of the 19th century. Elected rector of St. John's Episcopal Church in 1846, Humes led t ...

.

While Knoxville was far less dependent on slavery than the rest of the South, most of the city's leaders, even those who opposed secession, were pro-slavery at the onset of the Civil War.

Some, such as J.G.M. Ramsey, had always been pro-slavery.

However, numerous prominent Knoxvillians, including Brownlow,

Oliver Perry Temple

Oliver Perry Temple (January 27, 1820 – November 2, 1907) was an American attorney, author, judge, and economic promoter active primarily in East Tennessee in the latter half of the 19th century.Mary Rothrock, ''The French Broad-Holston Country: ...

, and Horace Maynard, had been pro-emancipation in the 1830s, but, for reasons not fully understood, were pro-slavery by the 1850s.

Temple later wrote that he and others abandoned their anti-slavery stance due to the social ostracism abolitionists faced in the South.

Historian Robert McKenzie, however, argues that the aggression of northern abolitionists toward Southerners pushed many Southern abolitionists toward pro-slavery views, though he points out that no one explanation neatly explains this shift.

In any case, by the late-1850s, most of Knoxville's leaders were pro-slavery. The views of Brownlow and Ramsey, bitter enemies on many fronts, were virtually identical on the issue of slavery.

Secession debate in Knoxville

The election of

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

in 1860 drastically intensified the secession debate in Knoxville, and the city's leaders met on November 26 to discuss the issue.

Those who favored secession, such as J.G.M. Ramsey, believed it was the only way to ensure the rights of Southerners. Those who rejected secession, such as Maynard and Temple, believed that East Tennesseans, most of whom were yeoman farmers, would be rendered subservient to a government dominated by Southern planters.

In February 1861, Tennessee held a vote on whether or not to hold a statewide convention to consider seceding and joining the

Confederacy

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a political union of sovereign states united for purposes of common action. Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical issu ...

.

In Knoxville, 77% voted against this measure, affirming the city's allegiance to the Union.

Throughout the first half of 1861, Brownlow and J. Austin Sperry (the radical secessionist editor of the ''Knoxville Register'') assailed one another mercilessly in their respective papers,

and Union and Secessionist leaders blasted one another in speeches across the region. Simultaneous Union and Confederate recruiting rallies were held on Gay Street.

Following the attack on Fort Sumter in April, Governor

Isham Harris

Isham Green Harris (February 10, 1818July 8, 1897) was an American and Confederate politician who served as the 16th governor of Tennessee from 1857 to 1862, and as a U.S. senator from 1877 until his death. He was the state's first governor from ...

made moves to align the state with the

Confederacy

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a political union of sovereign states united for purposes of common action. Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical issu ...

, prompting the region's Unionists to form the

East Tennessee Convention

The East Tennessee Convention was an assembly of Southern Unionist delegates primarily from East Tennessee that met on three occasions during the Civil War. The convention most notably declared the secessionist actions taken by the Tennessee sta ...

, which met at Knoxville on May 30, 1861. The convention submitted a petition to Governor

Isham Harris

Isham Green Harris (February 10, 1818July 8, 1897) was an American and Confederate politician who served as the 16th governor of Tennessee from 1857 to 1862, and as a U.S. senator from 1877 until his death. He was the state's first governor from ...

, calling his actions undemocratic and unconstitutional.

In a second statewide vote on June 8, 1861, a majority of East Tennesseans still rejected secession,

but the measure succeeded in Middle and West Tennessee, and the state thus joined the Confederacy. In Knoxville, the vote was 777 to 377 in favor of secession.

McKenzie points out, however, that 436 Confederate soldiers from outside Knox County were stationed in Knoxville at the time and were allowed to vote.

If these votes are removed, the tally in Knoxville was 377 to 341 ''against'' secession.

Following the vote, the East Tennessee Union Convention petitioned the state legislature, asking that East Tennessee be allowed to form a separate, Union-aligned state. The petition was rejected, however, and Governor Harris ordered Confederate troops into the region.

[Oliver P. Temple, ''East Tennessee and the Civil War'' (Johnson City, Tenn.: Overmountain Press, 1995).]

Civil War

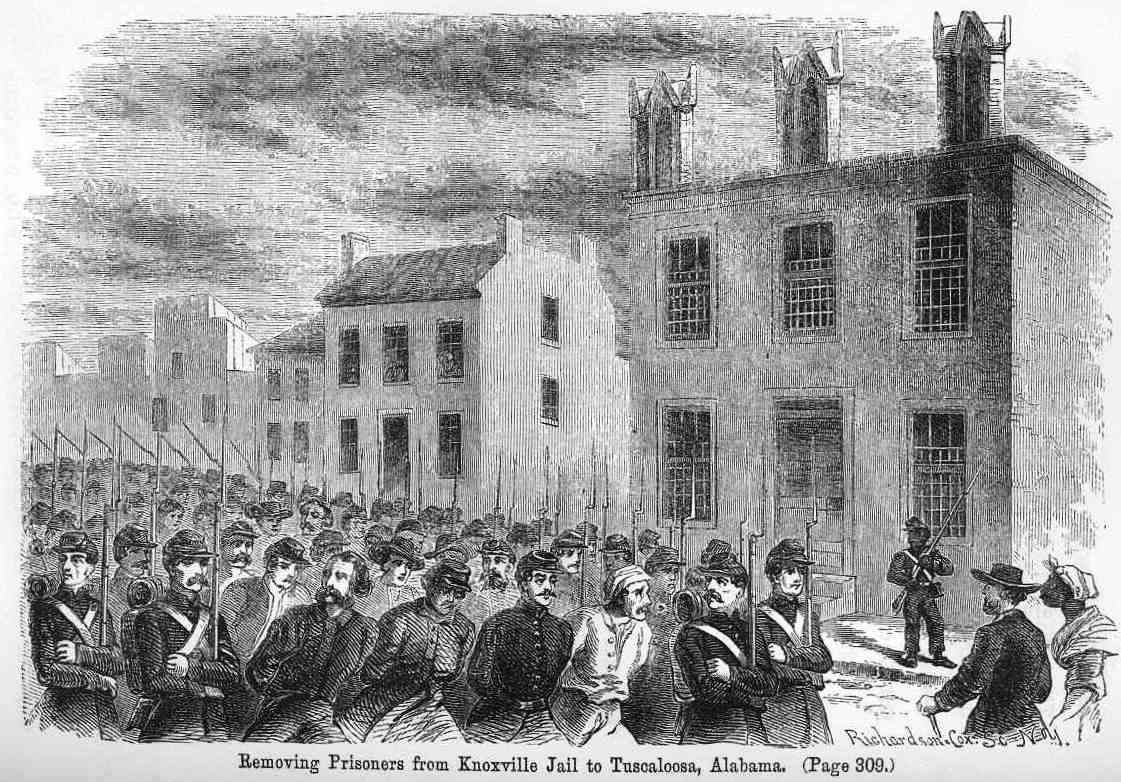

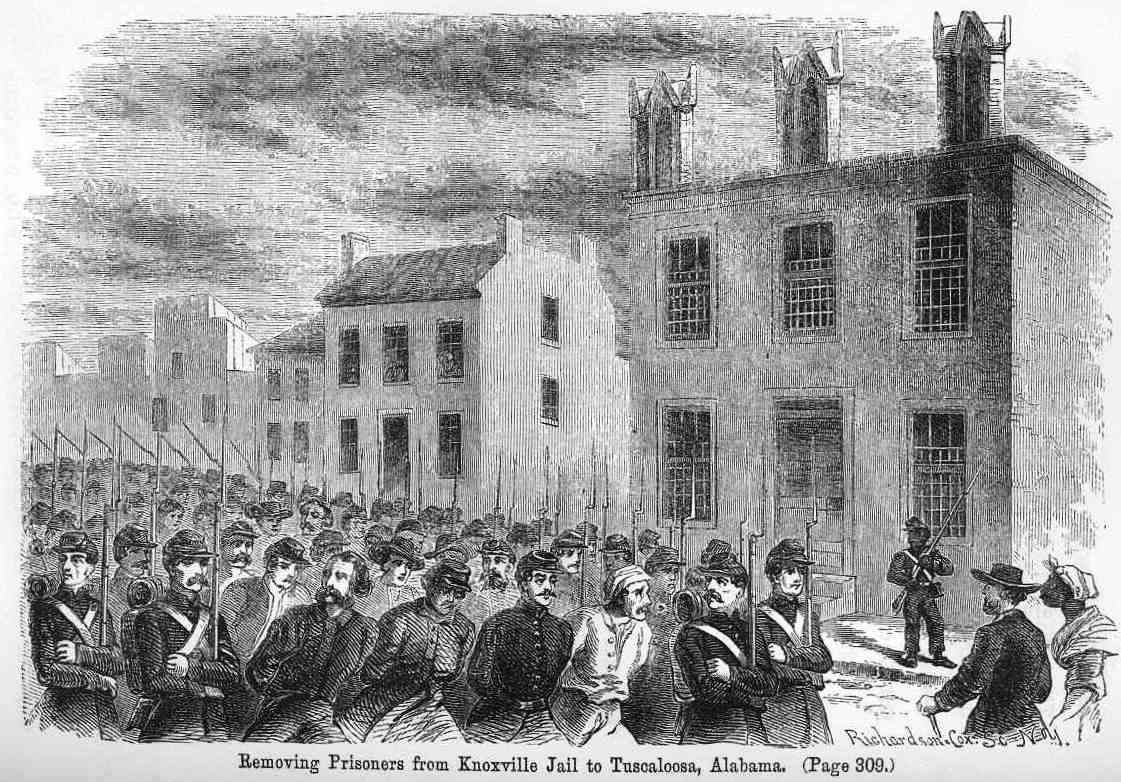

Confederate Occupation

The Confederate commander in East Tennessee,

Felix Zollicoffer, initially took a lenient stance toward the region's Unionists. In November 1861, however,

Union guerrillas destroyed several railroad bridges across East Tennessee, prompting Confederate authorities to institute

martial law

Martial law is the replacement of civilian government by military rule and the suspension of civilian legal processes for military powers. Martial law can continue for a specified amount of time, or indefinitely, and standard civil liberties ...

.

Suspected bridge-burning conspirators were tried and executed, and hundreds of other Unionists were jailed, causing the county jail at the southwestern corner of Main and Walnut streets to become overcrowded with prisoners.

Brownlow was among those arrested, but was released after a few weeks. He spent 1862 touring the north in an attempt to rally support for a Union invasion of East Tennessee.

Zollicoffer was replaced by John Crittenden in November 1861,

and Crittenden was in turn replaced by

Edmund Kirby Smith

Edmund Kirby Smith (May 16, 1824March 28, 1893) was a General officers in the Confederate States Army, Confederate States Army Four-star rank, general, who oversaw the Trans-Mississippi Department (comprising Arkansas, Missouri, Texas, western L ...

in March 1862,

as Confederate authorities consistently struggled to find an acceptable commander for its East Tennessee forces. In June 1862, George Wilson, one of

Andrews' Raiders, was tried and convicted in Knoxville.

In July 1862, 40 Union soldiers captured by

Nathan Bedford Forrest

Nathan Bedford Forrest (July 13, 1821October 29, 1877) was an List of slave traders of the United States, American slave trader, active in the lower Mississippi River valley, who served as a General officers in the Confederate States Army, Con ...

near Murfreesboro were marched down Gay Street, with Confederate soldiers jokingly reading aloud their personal correspondence afterward.

The divided 2nd District sent representatives to both the U.S. Congress (Horace Maynard) and the Confederate Congress (William G. Swan) in 1861.

Maynard, along with fellow East Tennessee Unionist

Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. The 16th vice president, he assumed the presidency following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a South ...

, consistently pleaded with President Lincoln to send troops into the region.

For nearly two years, however, Union generals in Kentucky consistently ignored orders to march on Knoxville, and instead focused on Middle Tennessee.

On June 20, 1863,

William P. Sanders's Union cavalry briefly laid siege to Knoxville, but a Confederate citizens' guard within the city managed to fend them off.

Union Occupation

In August 1863, Simon Buckner, the last of a string of Confederate commanders based in Knoxville, evacuated the city. On September 1, the vanguard of Union general

Ambrose Burnside

Ambrose Everts Burnside (May 23, 1824 – September 13, 1881) was an American army officer and politician who became a senior Union general in the American Civil War and a three-time Governor of Rhode Island, as well as being a successfu ...

entered the city to great fanfare (the unit briefly chased future mayor

Peter Staub

Johann Peter Staub colloquially Peter Staub (February 22, 1827 – May 19, 1904) was a Swiss-born American businessman, politician, and diplomat. Staub held several public offices, most notably as U.S. Consul to St. Gallen, appointed in 1885 b ...

through the streets).

Oliver Perry Temple joyously ran behind the soldiers the length of Gay Street,

and pro-Union Mayor

James C. Luttrell raised a large American flag he had saved for the occasion.

Burnside set up his headquarters at John Hervey Crozier's house at the corner of Gay and Union. Thomas William Humes was reinstalled as rector of St. John's Episcopal,

[Digby Gordon Seymour, ''Divided Loyalties: Fort Sanders and the Civil War in East Tennessee'' (Knoxville, Tenn.: University of Tennessee Press, 1963).] and Brownlow returned to the city and once again began publication of the ''Whig''.

Anticipating the Confederates would soon attempt to retake the city, Burnside and his chief engineer,

Orlando Poe, set about fortifying the city with a string of earthworks, bastions, and trenches.

In November 1863, Confederate general

James Longstreet

James Longstreet (January 8, 1821January 2, 1904) was a General officers in the Confederate States Army, Confederate general during the American Civil War and was the principal subordinate to General Robert E. Lee, who called him his "Old War Ho ...

moved north from Chattanooga in hopes of forcing Burnside out of Knoxville. Burnside's forces managed to delay Longstreet at the

Battle of Campbell's Station

The Battle of Campbell's Station (November 16, 1863) saw Confederate States Army, Confederate forces under Lieutenant General James Longstreet attack Union (American Civil War), Union troops led by Major General Ambrose Burnside at Campbell's St ...

on November 16, but was forced to retreat back to Knoxville with Longstreet in pursuit.

General Sanders was mortally wounded on November 18 executing a critical delaying action along Kingston Pike. Fort Loudon, one of the city's earthen bastions, was renamed "Fort Sanders" in his honor.

Longstreet's forces laid siege to Knoxville for two weeks, though the Union Army managed to resupply Burnside via the river.

On the morning of November 29, 1863, Longstreet ordered his forces to attack Fort Sanders. During the

Battle of Fort Sanders

The Battle of Fort Sanders was the crucial engagement of the Knoxville Campaign of the American Civil War, fought in Knoxville, Tennessee, on November 29, 1863. Assaults by Confederate Lt. Gen. James Longstreet failed to break through the def ...

, the Confederate attackers struggled to overcome Union trenches and the barrage of Union gunfire, and were forced to withdraw after just 20 minutes.

On December 2, Longstreet lifted the siege and withdrew to Virginia, leaving the city in Union hands until the end of the war.

Aftermath

In April 1864, the East Tennessee Union Convention reconvened in Knoxville, and while its delegates were badly divided, several, including Brownlow and Maynard, supported a resolution recognizing the Emancipation Proclamation.

Confederate businessman Joseph Mabry and future business leaders such as

Charles McClung McGhee

Charles McClung McGhee (January 23, 1828 – May 5, 1907) was an American industrialist and financier, active primarily in Knoxville, Tennessee. As director of the East Tennessee, Virginia, and Georgia Railway (ETV&G), McGhee was responsible ...

and

Peter Kern began working with Union leaders to rebuild the city.

[Jerome Taylor, "The Extraordinary Life and Death of Joseph A. Mabry," East Tennessee Historical Society ''Publications'', No. 44 (1972), pp. 41-70.] Brownlow remained vengeful, however, seizing the property of Confederate leaders J.G.M. Ramsey, William Sneed (including the

Lamar House Hotel), and William Swan, and expelling known Confederate sympathizers from the city.

Acts of Civil War-related violence occurred in Knoxville for years after the war. On September 4, 1865, Confederate soldier Abner Baker was lynched in Knoxville after killing a Union soldier who had killed his father.

On July 10, 1868, Union major

E.C. Camp shot and killed Confederate colonel Henry Ashby on Main Street in front of the courthouse over a Civil War grievance. On June 13, 1870, Joseph Mabry shot pro-Union attorney John Baxter in front of the Lamar House, capping a feud that had been building since the war.

The following year, David Nelson, the son of pro-Union congressman

T.A.R. Nelson, shot and killed Confederate general

James Holt Clanton

James Holt Clanton (January 8, 1827 – September 27, 1871) was an American soldier, lawyer, legislator, and was later also a Confederate soldier. He enlisted in the United States Army for service during the Mexican–American War, and later was ...

on Gay Street in front of the Lamar House.

Knoxville and the rise of the New South (1866–1920)

Economic Growth

According to historian William MacArthur, Knoxville "grew from a town to a city between 1870 and 1900."

A number of newcomers from the North, with the help of prewar local business elites, quickly established the city's first heavy industries. Hiram Chamberlain and the

Welsh-born Richards brothers established the

Knoxville Iron Company

The Knoxville Iron Company was an iron production and coal mining company that operated primarily in Knoxville, Tennessee, United States, and its vicinity, in the late 19th and 20th centuries.J. S. Rabun, National Register of Historic Places Regis ...

in 1868, and erected a large mill in the Second Creek Valley.

[John Wooldridge, George Mellen, William Rule (ed.), ''Standard History of Knoxville, Tennessee'' (Chicago: Lewis Publishing Company, 1900; reprinted by Kessinger Books, 2010).] The following year, Charles McClung McGhee and several investors purchased the city's two major railroads and merged them into the

East Tennessee, Virginia and Georgia Railway

The East Tennessee, Virginia and Georgia Railroad (ETV&G) was a rail transport system that operated in the southeastern United States during the late 19th century. Created with the consolidation of the East Tennessee and Virginia Railroad and th ...

, which would eventually control over of tracks in five states.

[Edwin Patton, Lucile Deaderick (ed.), "Transportation Development," ''Heart of the Valley: A History of Knoxville, Tennessee'' (Knoxville, Tenn.: East Tennessee Historical Society, 1976).] The city's textile industry took shape with the establishment of the Knoxville Woolen Mills and

Brookside Mills

Brookside Mills was a textile manufacturing company that operated in Knoxville, Tennessee, United States, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The company's Second Creek factory was the city's largest employer in the early 1900s.East Tenne ...

in 1884 and 1885, respectively.

As one of the largest cities in the Southern Appalachian region, Knoxville had long been a nexus between the surrounding rural mountain hinterland and the major industrial centers of the North, and thus had long been home to a thriving wholesaling (or "jobbing") market. Rural merchants from across East Tennessee purchased goods for their general stores from Knoxville wholesalers.

With the arrival of the railroad, the city's wholesaling sector expanded rapidly, with over a dozen firms in operation by 1860, and 50 by 1896.

In 1866, Knoxville-based wholesaler Cowan, McClung and Company was the most profitable company in the state. By the late-1890s, Knoxville had the third-largest wholesaling market in the South.

[William Bruce Wheeler, ''Knoxville, Tennessee: A Mountain City in the New South'' (Knoxville, Tenn.: University of Tennessee Press, 2005).]

The railroad also led to a boom in the quarrying and production of

Tennessee marble

Tennessee marble is a type of crystalline limestone found only in East Tennessee, in the southeastern United States. Long esteemed by architects and builders for its pinkish-gray color and the ease with which it is polished, the stone has been use ...

, a type of crystalline limestone found in abundance in the ridges surrounding Knoxville. By the early 1890s, twenty-two quarries and three finishing mills were in operation in Knox County alone, and the industry as a whole was generating over a million dollars in annual profits.

Tennessee marble was used in monumental construction projects across the nation, earning Knoxville the nickname, "The Marble City," during the late 19th century.

[Ask Doc Knox,]

What's With All This Marble City Business?

''Metro Pulse'', 10 May 2010. Retrieved: 10 August 2011. The

Flag of Knoxville, Tennessee

The city flag of Knoxville, Tennessee was officially adopted by municipal ordinance on October 16, 1896. It is the third oldest official city flag in the United States and the oldest flag of any state or city governmental entity in Tennessee.

S ...

incorporates the color white to symbolize marble and displays a

derrick

A derrick is a lifting device composed at minimum of one guyed mast, as in a gin pole, which may be articulated over a load by adjusting its Guy-wire, guys. Most derricks have at least two components, either a guyed mast or self-supporting tower ...

used in marble mining.

Demographic Changes

Knoxville's pre-1850s population consisted primarily of European-American (of mostly English, Scots-Irish, or German descent) Protestants and a small community of free blacks and slaves.

[Mark Banker, ''Appalachians All: East Tennessee and the Elusive History of an American Region'' (Knoxville, Tenn.: University of Tennessee Press, 2010).] Railroad construction in the 1850s brought to the city large numbers of Irish Catholic immigrants, who helped establish the city's first Catholic congregation in 1855.

The Swiss were another important group in 19th-century Knoxville, with businessmen

James G. Sterchi and Peter Staub, Supreme Court justice

Edward Terry Sanford

Edward Terry Sanford (July 23, 1865 – March 8, 1930) was an American jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1923 until his death in 1930. Prior to his nomination to the high court, Sanford ser ...

, philosopher

Albert Chavannes, and builder David Getaz, all claiming descent from the city's Swiss immigrants.

[Ann Bennett, "Historic and Architectural Resources in Knoxville and Knox County, Tennessee," National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Listing Registration Form, May 1994, Section E.] Welsh immigrants brought mining and metallurgical expertise to the city in the late 1860s and 1870s.

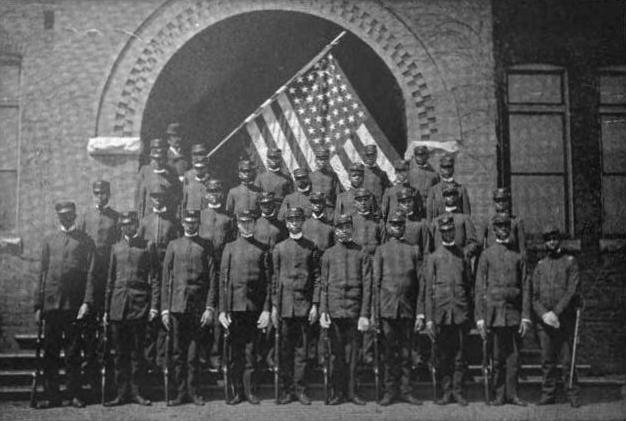

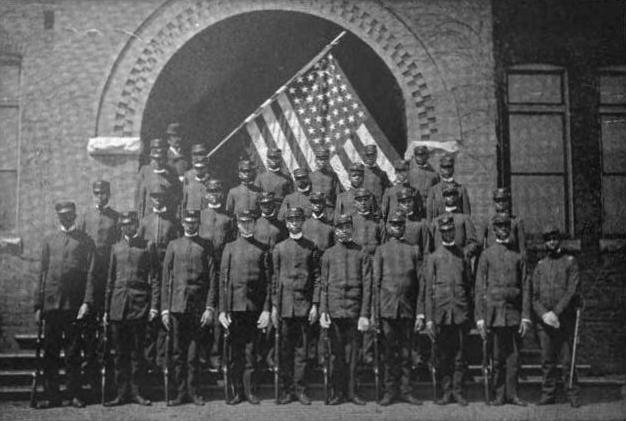

After the Civil War, African Americans, both freed slaves and blacks that had been free prior to the war, played an increasing role in the city's political and economic affairs. Racetrack and saloon owner

Cal Johnson, born a slave, was one of the wealthiest African Americans in the state by the time of his death.

[Becky French Brewer and Douglas Stuart McDaniel, ''Park City'' (Arcadia Publishing, 2005), p. 38.] Attorney

William F. Yardley

William Francis Yardley (January 8, 1844 – May 20, 1924) was an American attorney, politician and civil rights advocate, operating primarily out of Knoxville, Tennessee, in the late 19th century. He was Tennessee's first African-American gu ...

, a member of the city's free black community, was Tennessee's first black gubernatorial candidate in 1876.

Knoxville College

Knoxville College is an unaccredited private historically black college in Knoxville, Tennessee, United States. It was founded in 1875 by the United Presbyterian Church of North America. The college is a United Negro College Fund member sch ...

was founded in 1875 to provide educational opportunities for the city's black community.

Greek immigrants began arriving in Knoxville in significant numbers in the early 20th century. Knoxville's Greek community is perhaps best known for its restaurateurs, namely the Regas family, who operated a restaurant on North Gay Street from 1919 to 2010, and the Paskalis family, who founded the Gold Sun Cafe on Market Square around 1909.

Notable members of Knoxville's Jewish community included jeweler Max Friedman and department store owner Max Arnstein.

One of Knoxville's largest migrant groups consisted of rural people who moved to the city from the surrounding rural counties, often seeking wage-paying jobs in mills.

Many of Knoxville's political and business leaders throughout the 20th century hailed from rural areas of Southern Appalachia.

Knoxville in the Gilded Age

Swiss immigrant Peter Staub built Knoxville's first opera house, Staub's Theatre, on Gay Street in 1872. This was also one of the first major structures designed by architect

Joseph Baumann, who would design many of the city's more prominent late-19th-century buildings. During this same period, the Lamar House Hotel, located across the street from the theater, was a popular gathering place for the city's elite. The hotel hosted lavish masquerade balls, and served oysters, cigars, and imported wines.

[Jack Neely, ''Knoxville's Secret History'' (Scruffy Books, 1995).]

Initially a place for farmers to sell produce,

Market Square

A market square (also known as a market place) is an urban square meant for trading, in which a market is held. It is an important feature of many towns and cities around the world. A market square is an open area where market stalls are tradit ...

had evolved into one of the city's commercial and cultural centers by the 1870s. The square's most notable business was Peter Kern's ice cream saloon and confections factory, which hosted numerous festivals for various groups in the late 19th century.

The square also attracted street preachers, early

country

A country is a distinct part of the world, such as a state, nation, or other political entity. When referring to a specific polity, the term "country" may refer to a sovereign state, state with limited recognition, constituent country, ...

musicians,

and political activists. Women's suffragist

Lizzie Crozier French

Margaret Elizabeth Crozier French (May 7, 1851 – May 14, 1926) was an American educator, women's suffragist and social reform activist. She was one of the primary leaders in the push for women's rights in Tennessee in the early 1900s, and ...

was delivering speeches on Market Square as early as the 1880s.

After the Civil War, Thomas William Humes was named president of East Tennessee University (renamed the University of Tennessee in 1879), and managed to acquire for the institution the state's

Morrill Act land-grant funds, allowing the school to expand. In 1886, Charles McClung McGhee established the Lawson McGhee Library, named for his late daughter, which became the basis of Knox County's public library system. In 1873, Humes managed to obtain a Peabody Fund grant that allowed Knoxville to establish a public school system.

Expansion (1869–1917)

Knoxville's first major annexation following the Civil War came in 1869, when it annexed the city of East Knoxville, an area east of First Creek that had incorporated in 1856.

In 1883, Knoxville annexed

Mechanicsville, which had developed just northwest of the city as a village for Knoxville Iron Company and other factory workers. In the 1870s and 1880s, the development of Knoxville's

streetcar

A tram (also known as a streetcar or trolley in Canada and the United States) is an urban rail transit in which vehicles, whether individual railcars or multiple-unit trains, run on tramway tracks on urban public streets; some include s ...

system (electrified by

William Gibbs McAdoo

William Gibbs McAdoo Jr.McAdoo is variously differentiated from family members of the same name:

* Dr. William Gibbs McAdoo (1820–1894) – sometimes called "I" or "Senior"

* William Gibbs McAdoo (1863–1941) – sometimes called "II" or "J ...

in 1890) led to the rapid development of suburbs on the city's periphery.

Neighborhoods such as

Fort Sanders,

Fourth and Gill

Fourth and Gill is a neighborhood in Knoxville, Tennessee, United States, located north of the city's downtown area. Initially developed in the late nineteenth century as a residential area for Knoxville's growing middle and professional classe ...

,

Old North Knoxville

Old North Knoxville is a neighborhood in Knoxville, Tennessee, United States, located just north of the city's downtown area. Initially established as the town of North Knoxville in 1889, the area was a prominent suburb for Knoxville's upper m ...

, and

Parkridge, are all rooted in "

streetcar suburb

A streetcar suburb is a residential community whose growth and development was strongly shaped by the use of streetcar lines as a primary means of transportation. Such suburbs developed in the United States in the years before the automobile, when ...

s" developed during this period.

In 1888, the area now consisting of Fort Sanders and the U.T. campus were incorporated as the City of West Knoxville, and in 1889 the area now consisting of Old North Knoxville and Fourth and Gill incorporated as the City of North Knoxville. Knoxville annexed both in 1897.

In 1907, Parkridge,

Chilhowee Park

Chilhowee Park is a public park, fairgrounds and exhibition venue in Knoxville, Tennessee, United States, located off Magnolia Avenue in East Knoxville. Developed in the late 19th century, the park is home to the Tennessee Valley Fair and hosts ...

, and adjacent neighborhoods incorporated as Park City.

, a factory village northwest of the city, and Mountain View, located south of Park City, incorporated that same year.

Oakwood, which developed alongside the Southern Railway's Coster rail yard, was incorporated in 1913.

In 1917, Knoxville annexed these four cities, along with the burgeoning suburb of

Sequoyah Hills

Sequoyah Hills is a neighborhood in Knoxville, Tennessee, United States, named for the Cherokee scholar Sequoyah.[Chilhowee Park

Chilhowee Park is a public park, fairgrounds and exhibition venue in Knoxville, Tennessee, United States, located off Magnolia Avenue in East Knoxville. Developed in the late 19th century, the park is home to the Tennessee Valley Fair and hosts ...]

.

[Robert Lukens]

Appalachian Exposition of 1910

''Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture'', 2009. Retrieved: 10 August 2011. A third, the

National Conservation Exposition

The National Conservation Exposition was an World's Fair, exposition held in Knoxville, Tennessee, United States, between September 1, 1913, and November 1, 1913. The exposition celebrated the cause of bringing national attention to conservation e ...

, was held in 1913. The fairs demonstrated the economic trend known as the "New South," the transition of the South from an agricultural-based economy to an industrial one.

The fairs also advocated the responsible usage of the region's natural resources.

Urban Issues

Knoxville's rapid growth in the late 19th century led to increased pollution, mainly from the increasing use of coal,

and a rise in the crime rate, exacerbated by the influx of large numbers of people with very low-paying jobs.

The city, which had suffered serious

cholera

Cholera () is an infection of the small intestine by some Strain (biology), strains of the Bacteria, bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea last ...

outbreaks in 1849, 1854, 1866, and 1873, and

smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by Variola virus (often called Smallpox virus), which belongs to the genus '' Orthopoxvirus''. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (W ...

epidemics in 1850, 1855, 1862, 1863, 1864, and 1866, created a health department in 1879, and established a city hospital in 1883.

Activists such as Lizzie Crozier French and businessmen such as E.C. Camp established organizations that helped the poor.

By the 1880s, Knoxville had a murder rate that was higher than

Los Angeles

Los Angeles, often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, most populous city in the U.S. state of California, and the commercial, Financial District, Los Angeles, financial, and Culture of Los Angeles, ...

's murder rate in the 1990s.

Journalist Jack Neely points out that "saloons, whorehouses, cocaine parlors, gambling dens, and poolrooms" lined Central Street from the railroad tracks to the river. High-profile shootouts were not uncommon, the most well-known being the Mabry-O'Connor shootout on Gay Street, which left banker Thomas O'Connor, businessman Joseph Mabry, and Mabry's son, dead in 1882. In 1901,

Kid Curry

(Known month and day)

(known month)

(known year) -->

, birth_place = Richland Township, Tama County, Iowa, United States

, death_date =

, death_place = Parachute, Colorado, United States

, re ...

, a member of

Butch Cassidy's Wild Bunch

Butch Cassidy's Wild Bunch was one of the loosely organized outlaw gangs operating out of the Hole-in-the-Wall, near Kaycee in Wyoming, a natural fortress of caves, with a narrow entrance that was constantly guarded. In the beginning, the gang w ...

, shot and killed two police officers at Ike Jones's Bar on Central.

[Jack Neely,]

Knoxville's Oldest Bar

" ''Metro Pulse'', 20 August 2008. Retrieved: 10 August 2011. The Kid Curry shooting helped fuel calls for citywide prohibition, which was enacted in 1907.

After

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, the United States suffered a major economic recession, and Knoxville, like many other cities, experienced an influx of migrants moving to the city in search of work. Racial tensions heightened as poor whites and blacks competed for the few available jobs, and both the

Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to KKK or Klan, is an American Protestant-led Christian terrorism, Christian extremist, white supremacist, Right-wing terrorism, far-right hate group. It was founded in 1865 during Reconstruction era, ...

and the

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is an American civil rights organization formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. B. Du&nbs ...

(NAACP) opened chapters in the city.

[Matthew Lakin, "'A Dark Night': The Knoxville Race Riot of 1919," ''Journal of East Tennessee History'', 72 (2000), pp. 1-29.] On August 30, 1919, these tensions erupted in the so-called

Riot of 1919, the city's worst race riot, which shattered the city's vision of itself as a racially tolerant Southern town.

Transition to a modern city (1920–1960)

Louis Brownlow

In 1912, Knoxvillians replaced their mayor-alderman form of government with a commissioner form of government that consisted of five commissioners elected at-large, and a mayor chosen from among the five.

Following the 1917 annexations, the city began to struggle as it extended services to the newly annexed areas, and it became clear the new government was ineffective at dealing with the city's financial issues.

In 1923, the city voted to replace the commissioners with a city manager-council form of government, which involved the election of a city council, who would then hire a city manager to oversee the city's business affairs.

The first city manager hired by Knoxville was

Louis Brownlow

Louis Brownlow (August 29, 1879 – September 27, 1963) was an American author, political scientist, and consultant in the area of public administration. As chairman of the Committee on Administrative Management (better known as the Brownlow Comm ...

, the successful city manager of

Petersburg, Virginia

Petersburg is an independent city (United States), independent city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population was 33,458 with a majority bla ...

, and a cousin of Parson Brownlow.

When Brownlow arrived in Knoxville, he was horrified by the city's condition, later writing that he found "something new and more disturbing" every day.

[Louis Brownlow, ''A Passion for Anonymity'' (University of Chicago Press, 1958).] There were no paved roads connecting Knoxville with other major cities. The lone operable tank of the city's waterworks was full of cracks that Knoxvillians had been lazily plugging with

gunny sack

A gunny sack, also known as a gunny shoe, burlap sack, hessian sack or tow sack, is a large Bag, sack, traditionally made of burlap (Hessian fabric) formed from jute, hemp, sisal, or other natural fibres, usually in the crude Spinning (textile ...

s.

The city hospital was unable to buy drugs, as it was deeply in debt, and its credit had been cut off.

City Hall, then located on Market Square, was filthy, noisy and disorganized.

Brownlow immediately got to work, negotiating a more favorable bond rate and ordering greater scrutiny of all purchases.

He also convinced the city to purchase the vacated

Tennessee School for the Deaf building for use as a city hall.

While Brownlow had some initial success, his initiatives met staunch opposition from South Knoxville councilman Lee Monday, who according to Brownlow, was "representative of that top-of-the-voice screamology of East Tennessee mountain politics."

Opposition to Brownlow gradually intensified, especially after he called for a tax increase, and following the election of a less-friendly city council in 1926, Brownlow resigned.

Economic struggles

While Knoxville experienced tremendous growth in the late 19th century, by the early 1900s, the city's economy was beginning to show signs of stagnation.

The natural resources of the surrounding region were either exhausted or their demand fell sharply, and the decline of railroads in favor of other forms of shipping led to the collapse of the city's wholesaling sector.

Population growth also declined, though this trend was masked by the 1917 annexations.

Historian Bruce Wheeler suggests that the city's overly provincial economic "elite," which had long demonstrated a disdain for change, and the masses of new rural ("Appalachian") and African-American migrants, both of whom were suspicious of government, formed an odd alliance that consistently rejected major attempts at reform.

As Knoxvillians were adamantly opposed to tax increases, the city consistently had to rely on bond issues to pay for city services.

An increasingly greater portion of existing revenues was required to pay interest on these bonds, leaving little money for civic improvements. Urban neighborhoods fell into ruin and the downtown area deteriorated.

Those who could afford it fled to new suburbs on the city's periphery, such as Sequoyah Hills,

Lindbergh Forest

Lindbergh Forest is a neighborhood in Knoxville, Tennessee, United States, located off Chapman Highway ( US-441) in South Knoxville, that is listed on the National Register of Historic Places as an historic district. Initially developed in the ...

, or

North Hills.

During the

Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

, Knoxville's six largest banks either failed or were forced into mergers.

Construction fell 70%, and unemployment tripled.

African Americans were hit hardest, as business owners began hiring whites for jobs traditionally held by black workers, such as bakers, telephone workers, and road pavers.

The city was forced pay its employees in

scrip

A scrip (or ''wikt:chit#Etymology 3, chit'' in India) is any substitute for legal tender. It is often a form of credit (finance), credit. Scrips have been created and used for a variety of reasons, including exploitative payment of employees un ...

, and begged creditors to allow it to refinance its debt.

Federal programs and infrastructure growth

In the 1930s and early 1940s, several major federal programs provided some relief to Knoxvillians suffering amidst the Depression. The

Great Smoky Mountains National Park

Great Smoky Mountains National Park is a List of national parks of the United States, national park of the United States in the southeastern United States, southeast, with parts in North Carolina and Tennessee. The park straddles the ridgeline o ...

, which wealthy Knoxvillians had led the drive to create, opened in 1932.

In 1933, the

Tennessee Valley Authority

The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) is a federally owned electric utility corporation in the United States. TVA's service area covers all of Tennessee, portions of Alabama, Mississippi, and Kentucky, and small areas of Georgia, North Carolin ...