History Of Jacksonville, Florida on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The city of

In 1513, Spanish explorers landed in Florida and claimed their discovery for Spain (see

In 1513, Spanish explorers landed in Florida and claimed their discovery for Spain (see

Following the

Following the

In the early 20th century, before

In the early 20th century, before

A significant part of Jacksonville's growth in the 20th century came from the presence of navy bases in the region. October 15, 1940, Naval Air Station Jacksonville ("NAS Jax") on the westside became the first navy installation in the city. This base was a major training center during World War II, with over 20,000 pilots and aircrewmen being trained there. After the war, the Navy's elite

A significant part of Jacksonville's growth in the 20th century came from the presence of navy bases in the region. October 15, 1940, Naval Air Station Jacksonville ("NAS Jax") on the westside became the first navy installation in the city. This base was a major training center during World War II, with over 20,000 pilots and aircrewmen being trained there. After the war, the Navy's elite

"Offshore Power Systems: Big Plants for a Big Customer"

Atomic Insights, August 1996Putnam, Walter

"Floating nuclear plants may become reality"

Boca Raton News, November 15, 1981 Construction of the new facility was projected to cost $200 million and create 10,000 new jobs when completed in 1976."Urban waterfront lands"

Page 136, National Research Council Committee, 1980 Contracts were signed by Public Service Electric and Gas Company with PSE&G paying for the startup costs for the manufacturing facility. Westinghouse named Zeke Zechella to be president of OPS in 1972.Kerr, Jessie-Lynne

“ALEXANDER P. 'ZEKE' ZECHELLA: 1920-2009”

Florida Times-Union, August 18, 2009 OPS obtained 850+ acres (3.4 km2) on

online edition

Photographic exhibit on the Great Fire of 1901

presented by the State Archives of Florida.

The Jacksonville Historical Society

{{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Jacksonville, Florida

Jacksonville, Florida

Jacksonville ( ) is the most populous city proper in the U.S. state of Florida, located on the Atlantic coast of North Florida, northeastern Florida. It is the county seat of Duval County, Florida, Duval County, with which the City of Jacksonv ...

, began to grow in the late 18th century as Cow Ford, settled by British colonists. Its major development occurred in the late nineteenth century, when it became a winter vacation destination for tourists from the North and Midwest. Its development was halted or slowed by the Great Fire of 1901, the Florida Land Bust of the 1920s, and the economic woes of the 1960s and 70s. Since the late 20th century, the city has experienced steady growth, with a new federal building constructed in downtown in 2003.

Since 1940, Jacksonville has also been a major port for the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

. The city is a thriving metropolis with over a million citizens. Due to its consolidated city-county

In local government in the United States, United States local government, a consolidated city-county (#Terminology, see below for alternative terms) is formed when one or more city, cities and their surrounding County (United States), county (Lis ...

government structure, it has the largest municipal population among Florida cities, as well as the largest land area of any city in the contiguous United States

The contiguous United States, also known as the U.S. mainland, officially referred to as the conterminous United States, consists of the 48 adjoining U.S. states and the District of Columbia of the United States in central North America. The te ...

.

Early days

Ancient history

Archaeological

Archaeology or archeology is the study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of Artifact (archaeology), artifacts, architecture, biofact (archaeology), biofacts or ecofacts, ...

evidence indicates 6,000 years of human habitation in the area. Pottery

Pottery is the process and the products of forming vessels and other objects with clay and other raw materials, which are fired at high temperatures to give them a hard and durable form. The place where such wares are made by a ''potter'' is al ...

has been found dating to 2500 BC, nearly the oldest in the United States and second to artifacts of the Savannah River

The Savannah River is a major river in the Southeastern United States, forming most of the border between the states of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia and South Carolina. The river flows from the Appalachian Mountains to the Atlantic Ocean, ...

area. In the 16th century, the beginning of the historical record period, the area was inhabited by the Mocama, a coastal subgroup of the Timucua

The Timucua were a Native American people who lived in Northeast and North Central Florida and southeast Georgia. They were the largest indigenous group in that area and consisted of about 35 chiefdoms, many leading thousands of people. The va ...

indigenous Native Americans. At the time of contact with Europeans, most Mocama villages in present-day Jacksonville were part of the powerful chiefdom known as the Saturiwa, centered on Fort George Island near the mouth of the St. Johns River

The St. Johns River () is the longest river in the U.S. state of Florida and is the most significant one for commercial and recreational use. At long, it flows north and winds through or borders 12 counties. The drop in elevation from River s ...

. They had a complex society, well-adapted to the environmental conditions of the area.

Colonial and territorial history

In 1513, Spanish explorers landed in Florida and claimed their discovery for Spain (see

In 1513, Spanish explorers landed in Florida and claimed their discovery for Spain (see Spanish Florida

Spanish Florida () was the first major European land-claim and attempted settlement-area in northern America during the European Age of Discovery. ''La Florida'' formed part of the Captaincy General of Cuba in the Viceroyalty of New Spain, and th ...

). The first Europeans to visit the area were Spanish missionaries

A missionary is a member of a religious group who is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Thomas Hale 'On Being a Miss ...

and explorers from this period. In February 1562, French naval officer Jean Ribault and 150 settlers arrived seeking land for a safe haven for the French Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , ; ) are a Religious denomination, religious group of French people, French Protestants who held to the Reformed (Calvinist) tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, ...

s, Protestants suffering religious persecution in France. Ribault explored the mouth of the St. Johns River

The St. Johns River () is the longest river in the U.S. state of Florida and is the most significant one for commercial and recreational use. At long, it flows north and winds through or borders 12 counties. The drop in elevation from River s ...

before moving north and establishing the colony of Charlesfort on what is now Parris Island, South Carolina. Ribault returned to France for supplies, but the French Wars of Religion

The French Wars of Religion were a series of civil wars between French Catholic Church, Catholics and Protestantism, Protestants (called Huguenots) from 1562 to 1598. Between two and four million people died from violence, famine or disease di ...

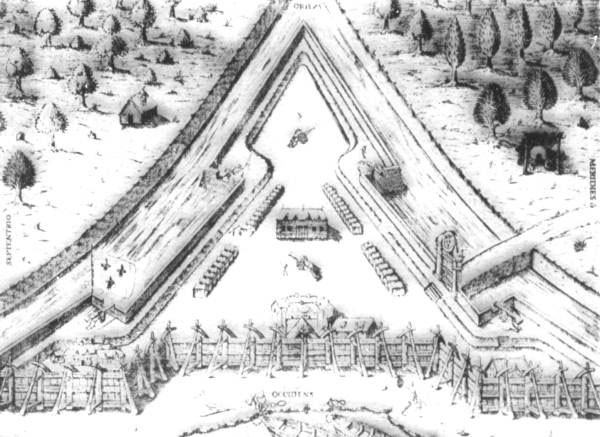

had broken out during his absence. His return to Florida was delayed as a result. Without leadership or provisions, the colonists abandoned Charlesfort. In 1564 Ribault's former lieutenant, René Goulaine de Laudonnière, launched a new expedition to found a colony on the St. Johns River. On June 22, 1564, the settlers established Fort Caroline atop the St. Johns Bluff.

Laudonnière made an alliance with the local tribe of Timucua

The Timucua were a Native American people who lived in Northeast and North Central Florida and southeast Georgia. They were the largest indigenous group in that area and consisted of about 35 chiefdoms, many leading thousands of people. The va ...

Indians, the Saturiwa. He also forged friendly relations with their competitors, the Utina tribe, who lived upriver to the south (around what is now Palatka and the Lake George area). Ribault intended to resupply Fort Caroline in early 1565, but was again delayed. As a result, the colony faced famine

A famine is a widespread scarcity of food caused by several possible factors, including, but not limited to war, natural disasters, crop failure, widespread poverty, an Financial crisis, economic catastrophe or government policies. This phenom ...

, three mutinies

Mutiny is a revolt among a group of people (typically of a military or a crew) to oppose, change, or remove superiors or their orders. The term is commonly used for insubordination by members of the military against an officer or superior, b ...

, and eventually warfare with the Utina. Ribault finally reached the fort with a relief expedition in the summer, and assumed command of the settlement. In the meantime, the Spanish admiral Pedro Menéndez de Avilés

Pedro Menéndez de Avilés (; ; 15 February 1519 – 17 September 1574) was a Spanish admiral, explorer and conquistador from Avilés, in Asturias, Spain. He is notable for planning the first regular trans-oceanic convoys, which became known as ...

had established the colony of St. Augustine 35 miles to the south, with the express mission to displace the French.

When he arrived, Ribault launched a naval expedition of 200 sailors and 400 soldiers to dislodge the Spanish, but a storm at sea incapacitated them for several days and caused numerous deaths. On September 20, 1565, Menéndez marched his men overland to Fort Caroline, defended by 200 or 250 people, and killed everyone except for 50 women and children and 26 men who escaped. The Spanish picked up the survivors of Ribault's fleet, and summarily executed all but 20.

The Spanish took over Fort Caroline, renaming it as San Matteo. In 1568 the French and Spanish confronted each other again here, when Dominique de Gourgues burned it to the ground. The Spanish rebuilt the fort, but abandoned it in 1569. The Spanish next built Fort San Nicolas further upriver to protect the rear flank of St. Augustine. "San Nicolas" served as their name for the Jacksonville area, a placename which survives in the neighborhood of St. Nicholas. The fort was located on the east side of the St. Johns, where Bishop Kenny High School now stands. The fort was abandoned in the late 17th century.

France and Spain were defeated by the British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

in the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War, 1754 to 1763, was a colonial conflict in North America between Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of France, France, along with their respective Native Americans in the United States, Native American ...

. During the war the British had defeated the Spanish in Cuba and occupied the island, whereas Florida had hardly seen any fighting. As part of the negotiations between the two nations in the aftermath of the war, Spain would cede Florida to Great Britain in exchange for the return of Cuba. The British agreed and Florida was ceded to the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

in 1763. The British soon constructed the King's Road connecting St. Augustine to Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

. The road crossed the St. Johns River at a narrow point, which the Seminole

The Seminole are a Native American people who developed in Florida in the 18th century. Today, they live in Oklahoma and Florida, and comprise three federally recognized tribes: the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, the Seminole Tribe of Florida, ...

called ''Wacca Pilatka'' and the British named the "Cow Ford", both names ostensibly reflecting the fact that cattle

Cattle (''Bos taurus'') are large, domesticated, bovid ungulates widely kept as livestock. They are prominent modern members of the subfamily Bovinae and the most widespread species of the genus '' Bos''. Mature female cattle are calle ...

were brought across the river there. The British divided Florida into the two colonies of British East Florida and British West Florida

British West Florida was a colony of the Kingdom of Great Britain from 1763 until 1783, when it was ceded to Kingdom of Spain, Spain as part of the Peace of Paris (1783), Peace of Paris.

British West Florida comprised parts of the modern U.S ...

.

The British government gave land grants to officers and soldiers who had fought in the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War, 1754 to 1763, was a colonial conflict in North America between Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of France, France, along with their respective Native Americans in the United States, Native American ...

in order to encourage settlement. In order to induce settlers to move to the two new colonies reports of Florida

Florida ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders the Gulf of Mexico to the west, Alabama to the northwest, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the north, the Atlantic ...

's natural wealth were published in England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

. A large number of British colonists who were "energetic and of good character" moved to Florida

Florida ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders the Gulf of Mexico to the west, Alabama to the northwest, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the north, the Atlantic ...

, mostly coming from South Carolina

South Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders North Carolina to the north and northeast, the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast, and Georgia (U.S. state), Georg ...

, Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

and England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

though there was also a group of settlers who came from the colony of Bermuda

Bermuda is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean. The closest land outside the territory is in the American state of North Carolina, about to the west-northwest.

Bermuda is an ...

. This would be the first permanent English-speaking population in what is now Duval County, Baker County, St. Johns County and Nassau County. The British built good public roads and introduced the cultivation of sugar cane, indigo and fruits as well the export of lumber. As a result of these initiatives northeastern Florida prospered economically in a way it never did under Spanish rule. Furthermore, the British governors were directed to call general assemblies as soon as possible in order to make laws for the Floridas and in the meantime they were, with the advice of councils, to establish courts. This would be the first introduction of much of the English-derived legal system which Florida still has today including trial-by-jury, habeas corpus

''Habeas corpus'' (; from Medieval Latin, ) is a legal procedure invoking the jurisdiction of a court to review the unlawful detention or imprisonment of an individual, and request the individual's custodian (usually a prison official) to ...

and county-based government.

The British gave control of the territory back to Spain in 1783. Americans of English descent and Americans of Scots-Irish descent began moving into northern Florida from the backwoods of Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

and South Carolina

South Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders North Carolina to the north and northeast, the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast, and Georgia (U.S. state), Georg ...

. Though technically not allowed by the Spanish authorities, the Spanish were never able to effectively police the border region and the backwoods settlers from the United States would continue to migrate into Florida unchecked. These migrants, mixing with the already present English-speaking settlers who had lived in Florida since the British period, would be the progenitors of the population known as Florida Crackers. The Spanish also accepted fugitive slaves from the newly-created United States if they accepted Catholic baptism.

Between 1812 and 1814 during the War of 1812 between the US and Britain, the US Navy assisted American settlers in Florida in "The Patriot War", a covert attempt to seize control of Florida from the Spanish. They began with invasions of Fernandina and Amelia Island. Spain sold the Florida Territory

The Territory of Florida was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 30, 1822, until March 3, 1845, when it was admitted to the Union as the state of Florida. Originally the major portion of the Spanish ...

to the United States in 1821 and, by 1822, Jacksonville's current name had come into use, to honor General Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before Presidency of Andrew Jackson, his presidency, he rose to fame as a general in the U.S. Army and served in both houses ...

. It first appears on a petition sent on June 15, 1822 to U.S. Secretary of State John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was the sixth president of the United States, serving from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States secretary of state from 1817 to 1825. During his long diploma ...

, asking that Jacksonville be named a port of entry

In general, a port of entry (POE) is a place where one may lawfully enter a country. It typically has border control, border security staff and facilities to check passports and visas and to inspect luggage to assure that contraband is not impo ...

. The city is named for Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before Presidency of Andrew Jackson, his presidency, he rose to fame as a general in the U.S. Army and served in both houses ...

, military governor of the Florida Territory and eventual President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

of the United States. U.S. settlers led by Isaiah D. Hart wrote a charter for a town government, which was approved by the Florida Legislative Council on February 9, 1832. Remembered as the city's most important founding father, Hart is memorialized with the Isaiah D. Hart Bridge over the St. Johns.

Civil War

Even before the outbreak of war, a militia unit was raised in Jacksonville in April 1859. The unit, called the Jacksonville Light Infantry, would become Company A of the 3rd Florida Infantry Regiment. The company carried a battle flag bearing the slogan "Let Us Alone" and was commanded by Dr. Holmes Steele, a former mayor of the city. During theAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

, Jacksonville was a key supply point for hogs and cattle leaving Florida and aiding the Confederate cause. Throughout most of the war, the US Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

maintained a blockade around Florida's ports, including Jacksonville. In October 1862 Union forces captured a Confederate battery in the Battle of St. Johns Bluff and occupied Jacksonville. Throughout the war Jacksonville changed hands several times, though never with a battle. On February 20, 1864, Union soldiers from Jacksonville marched inland and confronted the Confederate Army at the Battle of Olustee.

The battle was a devastating loss for the Union and a decisive victory for the Confederacy. Soldiers on both sides were veterans of the great battles in the eastern and western theaters of war, but many of them remarked in letters and diaries that they had never experienced such terrible fighting. The Confederate dead were buried at Oaklawn Cemetery in nearby Lake City. The Union losses caused Northern authorities to question the necessity of further Union involvement in the militarily insignificant region of northern Florida. On the morning of 22 February, as the Union forces were still retreating to Jacksonville, the 54th Massachusetts was ordered to counter-march back to Ten-Mile Station. The locomotive of a train carrying wounded Union soldiers had broken down and the wounded were in danger of capture. When the 54th Massachusetts arrived, the men attached ropes to the engine and cars and manually pulled the train approximately three miles to Camp Finnegan, where horses were secured to help pull the train. After that, the train was pulled by both men and horses to Jacksonville for a total distance of ten miles. It took forty-two hours to pull the train that distance.

The US Transport Maple Leaf was sunk at Jacksonville, April 1, 1864.

The U.S. Transport General Hunter was sunk in the St. John's River, April 16, 1864, close to where the Maple Leaf was sunk.

In the fall of 1865, a black enlisted man in the 3rd USCT was hung by his thumbs for stealing from a field kitchen. The punishment led to a riot and gunfire was exchanged between black enlisted men and their white officers. The riot was put down and several soldiers were put on trial for mutiny, with 6 of them being executed.

By the end of the war in 1865, a Union commander commented that Jacksonville had become "pathetically dilapidated, a mere skeleton of its former self, a victim of war."

Post Civil War

Winter resort era

Following the

Following the Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

, during Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Union ...

and afterward, Jacksonville and nearby St. Augustine became popular winter resorts for the rich and famous of the Gilded Age

In History of the United States, United States history, the Gilded Age is the period from about the late 1870s to the late 1890s, which occurred between the Reconstruction era and the Progressive Era. It was named by 1920s historians after Mar ...

. Visitors arrived by steamboat

A steamboat is a boat that is marine propulsion, propelled primarily by marine steam engine, steam power, typically driving propellers or Paddle steamer, paddlewheels. The term ''steamboat'' is used to refer to small steam-powered vessels worki ...

and (beginning in the 1880s) by railroad

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport using wheeled vehicles running in railway track, tracks, which usually consist of two parallel steel railway track, rails. Rail transport is one of the two primary means of ...

, and wintered at dozens of hotels and boarding houses. The 1888 Subtropical Exposition was held in Jacksonville and attended by President Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was the 22nd and 24th president of the United States, serving from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. He was the first U.S. president to serve nonconsecutive terms and the first Hist ...

, but the Florida-style world's fair did not lead to a lasting boost for tourism in Jacksonville. The area declined in importance as a resort destination after Henry Flagler

Henry Morrison Flagler (January 2, 1830 – May 20, 1913) was an American industrialist and a founder of Standard Oil, which was first based in Ohio. He was also a key figure in the development of the Atlantic coast of Florida and founder ...

extended the Florida East Coast Railroad to the south, reaching Palm Beach in 1894 and the Miami area in 1896. This drew tourism to the southern Atlantic Coast.

Yellow fever epidemics

Jacksonville's prominence as a winter resort was dealt another blow by major yellow fever epidemics in 1886 and 1888. During the second one, nearly ten percent of the more than 4,000 victims died, including the city's mayor. In the absence of scientific knowledge concerning the cause of yellow fever, nearly half (10,000 out of 25,000) of the city's panicked residents fled despite the imposition ofquarantine

A quarantine is a restriction on the movement of people, animals, and goods which is intended to prevent the spread of disease or pests. It is often used in connection to disease and illness, preventing the movement of those who may have bee ...

s. Inbound and outbound mail was fumigated in an effort to reduce contagion. Jacksonville's reputation as a healthful tourist destination suffered. The African-American population did not appear to catch the disease, leading the panicked population into erroneously believing that the black residents were "carriers" of the Yellow Fever. In fact, Black people had immunity from catching the disease earlier, as children.

Spanish–American War

During theSpanish–American War

The Spanish–American War (April 21 – August 13, 1898) was fought between Restoration (Spain), Spain and the United States in 1898. It began with the sinking of the USS Maine (1889), USS ''Maine'' in Havana Harbor in Cuba, and resulted in the ...

, gunrunners helping the Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

n rebels used Jacksonville as the center for smuggling illegal arms and supplies to the island. Duval County sheriff and future state governor, Napoleon Bonaparte Broward, was one of the many gunrunners operating out of the city. Author Stephen Crane travelled to Jacksonville to cover the war.

20th century

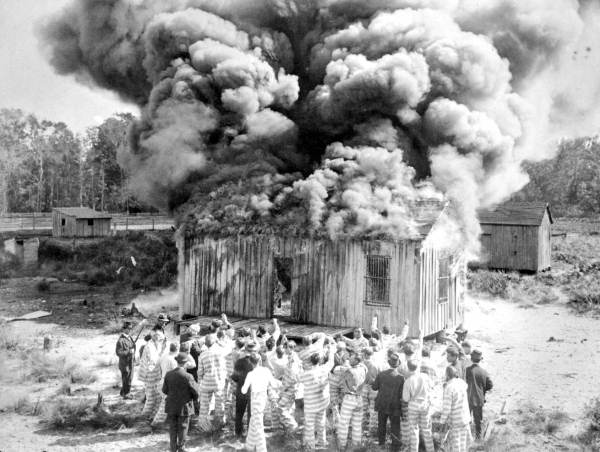

Great Fire of 1901

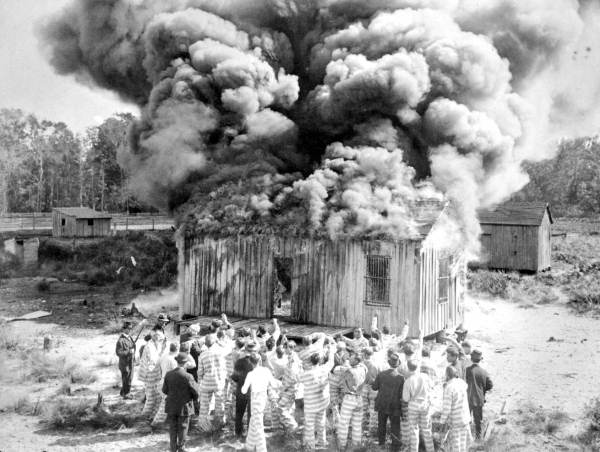

On May 3, 1901, downtown Jacksonville was ravaged by the Great Fire—the largest-ever urban fire in theSoutheastern United States

The Southeastern United States, also known as the American Southeast or simply the Southeast, is a geographical List of regions in the United States, region of the United States located in the eastern portion of the Southern United States and t ...

, which started when hot ash from a shantyhouse's chimney landed on the drying moss at Cleaveland's Fiber Factory. At half past noon most of the Cleaveland workers were at lunch, but by the time they returned the entire city block was engulfed in flames. The fire destroyed the business district and rendered 10,000 residents homeless in the course of eight hours. Florida Governor William S. Jennings declared a state of martial law

Martial law is the replacement of civilian government by military rule and the suspension of civilian legal processes for military powers. Martial law can continue for a specified amount of time, or indefinitely, and standard civil liberties ...

in Jacksonville and dispatched several state militia

A militia ( ) is a military or paramilitary force that comprises civilian members, as opposed to a professional standing army of regular, full-time military personnel. Militias may be raised in times of need to support regular troops or se ...

units to help. Reconstruction started immediately, and the city was returned to civil authority on May 17. Despite the widespread damage, only seven deaths were reported.

Young architect Henry John Klutho had just returned to New York from a year in Europe when he read about the Jacksonville fire and, seeing a rare opportunity, he headed south. Klutho and other architects, enamored by the " Prairie Style" of architecture then being popularized by architect Frank Lloyd Wright

Frank Lloyd Wright Sr. (June 8, 1867 – April 9, 1959) was an American architect, designer, writer, and educator. He designed List of Frank Lloyd Wright works, more than 1,000 structures over a creative period of 70 years. Wright played a key ...

in Chicago

Chicago is the List of municipalities in Illinois, most populous city in the U.S. state of Illinois and in the Midwestern United States. With a population of 2,746,388, as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the List of Unite ...

and other Midwestern cities, designed exuberant local buildings with a Florida flair. While many of Klutho's buildings were demolished by the 1980s, a number of his creations remain, including the St. James Building from 1911 (a former department store that is now Jacksonville's City Hall) and the Morocco Temple from 1910. The Klutho Apartments, in Springfield, were recently restored and converted into office space by local charity Fresh Ministries. Despite the losses of the last several decades, Jacksonville still has one of the largest collections of Prairie Style buildings (particularly residences) outside the Midwest.

Motion picture industry

In the early 20th century, before

In the early 20th century, before Hollywood

Hollywood usually refers to:

* Hollywood, Los Angeles, a neighborhood in California

* Hollywood, a metonym for the cinema of the United States

Hollywood may also refer to:

Places United States

* Hollywood District (disambiguation)

* Hollywood ...

, the motion picture industry was based in Fort Lee, New Jersey#America's first motion picture industry. In need of a winter headquarters, moviemakers were attracted to Jacksonville due to its warm climate, exotic locations, excellent rail access, and cheaper labor, earning the city the title of "The Winter Film Capital of the World."

In 1908, New York-based Kalem Studios

The Kalem Company was an early American film studio founded in New York City in 1907. It was one of the first companies to make films abroad and to set up winter production facilities, first in Florida and then in California. Kalem was sold to V ...

was the first to open a permanent studio in Jacksonville. Over the course of the next decade, more than 30 silent film companies established studios in town, including Metro Pictures

Metro Pictures Corporation was a Film, motion picture production company founded in early 1915 in Jacksonville, Florida. It was a forerunner of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. The company produced its films in New York, Los Angeles, and sometimes at le ...

(later MGM

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc. (also known as Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Pictures, commonly shortened to MGM or MGM Studios) is an American Film production, film and television production and film distribution, distribution company headquartered ...

), Edison Studios

Edison Studios was an American film production organization, owned by companies controlled by inventor and entrepreneur, Thomas Edison. The studio made close to 1,200 films, as part of the Edison Manufacturing Company (1894–1911) and then Tho ...

, Majestic Films, King Bee Film Company, Vim Comedy Company, Norman Studios

Norman Studios, also known as Norman Film Manufacturing Company is a former American film studio in Jacksonville, Florida. Founded by Richard Edward Norman, the studio produced silent films featuring African-American casts from 1919 to 1928. The ...

, Gaumont Studios and the Lubin Manufacturing Company

The Lubin Manufacturing Company was an American motion picture production company that produced silent films from 1896 to 1916. Lubin films were distributed with a Liberty Bell trademark.

*

*

History

The Lubin Manufacturing Company was forme ...

.

In 1914, Oliver ''"Babe"'' Hardy, a comedic actor and Georgia native, began his motion picture career in Jacksonville. He starred in over 36 short silent films his first year acting. With the closing of Lubin in early 1915, Oliver moved to New York then New Jersey to find film jobs. Acquiring a job with the Vim Company in early 1915, he returned to Jacksonville

Jacksonville ( ) is the most populous city proper in the U.S. state of Florida, located on the Atlantic coast of North Florida, northeastern Florida. It is the county seat of Duval County, Florida, Duval County, with which the City of Jacksonv ...

in the spring of 1917 before relocating to Los Angeles in October 1917.

In 1915, Joseph Engel opened Metro Pictures

Metro Pictures Corporation was a Film, motion picture production company founded in early 1915 in Jacksonville, Florida. It was a forerunner of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. The company produced its films in New York, Los Angeles, and sometimes at le ...

in Jacksonville.

In 1917, the first motion picture made in Technicolor

Technicolor is a family of Color motion picture film, color motion picture processes. The first version, Process 1, was introduced in 1916, and improved versions followed over several decades.

Definitive Technicolor movies using three black-and ...

and the first feature-length color movie produced in the United States, '' The Gulf Between'', was filmed on location in Jacksonville.

Jacksonville's mostly conservative residents, however, objected to the hallmarks of the early movie industry, such as car chases in the streets, simulated bank robberies and fire alarms in public places, and even the occasional riot.

In 1917, conservative Democrat John W. Martin was elected mayor on the platform of taming the city's movie industry. By that time, southern California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

was emerging as the major movie production center, thanks in large part to the move of film pioneers like William Selig and D.W. Griffith to the area. These factors hastened the demise of Jacksonville as a place for film production.

In 1920, Richard Norman, founder of Norman Film Manufacturing Company, a European American

European Americans are Americans of European ancestry. This term includes both people who descend from the first European settlers in the area of the present-day United States and people who descend from more recent European arrivals. Since th ...

, purchased the bankrupt Eagle Film studios, on the Eagle Film City property in Jacksonville’s rural Arlington section. and created a string of African American films starring black actors in the vein of Oscar Micheaux

Oscar Devereaux Micheaux (; January 2, 1884 – March 25, 1951) was an American author, film director and independent producer of more than 44 films. Although the short-lived Lincoln Motion Picture Company was the first movie company owned and c ...

and the Lincoln Motion Picture Company. In contrast to the degrading parts offered in certain white films such as ''The Birth of a Nation

''The Birth of a Nation'' is a 1915 American Silent film, silent Epic film, epic Drama (film and television), drama film directed by D. W. Griffith and starring Lillian Gish. The screenplay is adapted from Thomas Dixon Jr.'s 1905 novel and ...

'', Norman and his contemporaries sought to create positive stories featuring African Americans in what he termed "splendidly assuming different roles."

"Gateway to Florida"

The 1920s brought significant real estate development and speculation to the city during the great Florida land boom (and bust). Hordes of train passengers passed through Jacksonville on their way south to the new tourist destinations of South Florida, as most of the passenger trains arriving from the population centers of the North were routed through Jacksonville. The Riverside Theater, which opened in 1927, was the first theater in Florida to show talking pictures. Completion of theDixie Highway

Dixie Highway was a United States auto trail first planned in 1914 to connect the Midwest with the South. It was part of a system and was expanded from an earlier Miami to Montreal highway. The final system is better understood as a network o ...

(portions of which became U.S. 1) in the 1920s began to draw significant automobile traffic as well. An important entry point to the state since the 1870s, Jacksonville now justifiably billed itself as the "Gateway to Florida."

US Navy

Blue Angels

The Blue Angels, formally named the U.S. Navy Flight Demonstration Squadron, are a Aerobatics, flight demonstration squadron of the United States Navy.. Blue Angels official site. Formed in 1946, the unit is the second oldest formal aerobatics ...

were established at NAS Jax. Today NAS Jax is the third largest navy installation in the country and employs over 23,000 civilian and active-duty personnel.

In June 1941, land in the westernmost side of Duval County was earmarked for a second naval air facility. This became NAS Cecil Field, which during the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

was designated a Master Jet Base, the only one in the South. RF-8 Crusaders out of Cecil Field detected missiles in Cuba, precipitating the Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis () in Cuba, or the Caribbean Crisis (), was a 13-day confrontation between the governments of the United States and the Soviet Union, when American deployments of Nuclear weapons d ...

. In 1993, the Navy decided to close NAS Cecil Field, and this was completed in 1999. The land once occupied by this installation is now known as the "Cecil Commerce Center" and contains one of the campuses of Florida Community College which now offers civil aeronautics classes.

December 1942 saw the addition of a third naval installation to Jacksonville: Naval Station Mayport at the mouth of the St. Johns River. This port developed through World War II and today is the home port for many types of navy ships, most notably the aircraft carrier from 1995 to 26 July 2007, when Big John was towed away, eventually to be mothballed in Philadelphia. NS Mayport current employs about 14,000 personnel.

Jacksonville is also not far from Naval Submarine Base Kings Bay in St. Marys, Georgia, which is home to part of the US Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

's nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine ( SSBN) fleet.

The naval base became a key training ground in the 1950s and 1960s and as such, the population of the city rose dramatically. More than half of the residents in Jacksonville had some tie to the naval base, whether it be a relative stationed there, or due to employment opportunities, by 1970, necessitating the opening of an international airport

An international airport is an airport with customs and border control facilities enabling passengers to travel between countries. International airports are usually larger than domestic airports, and feature longer runways and have faciliti ...

in the area.

Hotel Roosevelt fire

On December 29, 1963, a fire gutted the first couple of stories of the Hotel Roosevelt on Adams Street, killing 22 people, setting a record for the highest one-day death toll in Jacksonville history. The hotel was later abandoned, with most businesses inside moving to the nearby Hotel George Washington.Floating nuclear power plants

Offshore Power Systems (OPS) was a 1970 joint venture betweenWestinghouse Electric Company

Westinghouse Electric Company LLC is an American nuclear power company formed in 1999 from the nuclear power division of the original Westinghouse Electric Corporation. It offers nuclear products and services to utilities internationally, includ ...

, who constructed nuclear generating plants, and Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock, who had recently merged with Tenneco

Tenneco, Inc. (formerly Tenneco Automotive and originally Tennessee Gas Transmission Company) is an American automotive components original equipment manufacturer and an aftermarket ride control and emissions products manufacturer. It is a ''F ...

, to create floating nuclear power plant

A nuclear power plant (NPP), also known as a nuclear power station (NPS), nuclear generating station (NGS) or atomic power station (APS) is a thermal power station in which the heat source is a nuclear reactor. As is typical of thermal power st ...

s at the Port of Jacksonville.Adams, Rod"Offshore Power Systems: Big Plants for a Big Customer"

Atomic Insights, August 1996Putnam, Walter

"Floating nuclear plants may become reality"

Boca Raton News, November 15, 1981 Construction of the new facility was projected to cost $200 million and create 10,000 new jobs when completed in 1976."Urban waterfront lands"

Page 136, National Research Council Committee, 1980 Contracts were signed by Public Service Electric and Gas Company with PSE&G paying for the startup costs for the manufacturing facility. Westinghouse named Zeke Zechella to be president of OPS in 1972.Kerr, Jessie-Lynne

“ALEXANDER P. 'ZEKE' ZECHELLA: 1920-2009”

Florida Times-Union, August 18, 2009 OPS obtained 850+ acres (3.4 km2) on

Blount Island

Blount Island is an island of approximately on the St. Johns River in Jacksonville, Florida, nine nautical miles (16.7 km) west of the Atlantic Ocean. One of three public cargo facilities at the Port of Jacksonville is located there, and ...

from the Jacksonville Port Authority (JPA) for $2,000/acre, then installed infrastructure using over 1,000 workers. A total of $125 million was invested in the property and facility, however; no plants were ever built.

Ax Handle Saturday

Because of its high visibility and patronage, the Hemming Park and surrounding stores were the site of numerouscivil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' political freedom, freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and ...

demonstrations in the 1960s. Black Sit-in

A sit-in or sit-down is a form of direct action that involves one or more people occupying an area for a protest, often to promote political, social, or economic change. The protestors gather conspicuously in a space or building, refusing to mo ...

s began on August 13, 1960 when students asked to be served at the segregated lunch counter at Woolworths, Morrison's Cafeteria and other eateries. They were denied service and kicked, spit at and addressed with racial slurs. This came to a head on "Ax Handle Saturday", August 27, 1960. A group of 200 middle aged and older white men (allegedly some were also members of the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to KKK or Klan, is an American Protestant-led Christian terrorism, Christian extremist, white supremacist, Right-wing terrorism, far-right hate group. It was founded in 1865 during Reconstruction era, ...

) gathered in Hemming Park armed with baseball bats and ax handles. They attacked the protesters conducting sit-ins. The violence spread, and the white mob started attacking all African-Americans in sight. Rumors were rampant on both sides that the unrest was spreading around the county (in reality, the violence stayed in relatively the same location, and did not spill over into the mostly-white, upper-class Cedar Hills neighborhood, for example). A black street gang called the "Boomerangs" attempted to protect the demonstrators. Police, who had not intervened when the protesters were attacked, now became involved, arresting members of the Boomerangs and other black residents who attempted to stop the beatings.

Nat Glover, who worked in Jacksonville law enforcement for 37 years, including eight years as Sheriff of Jacksonville, recalled stumbling into the riot. Glover said he ran to the police, expecting them to arrest the thugs, but was told to leave town or risk being killed.

Several whites had joined the black protesters on that day. Richard Charles Parker, a 25-year-old student attending Florida State University

Florida State University (FSU or Florida State) is a Public university, public research university in Tallahassee, Florida, United States. It is a senior member of the State University System of Florida and a preeminent university in the s ...

was among them. White protesters were the object of particular dislike by racists, so when the fracas began, Parker was hustled out of the area for his own protection. The police had been watching him and arrested him as an instigator, charging him with vagrancy, disorderly conduct and inciting a riot. After Parker stated that he was proud to be a member of the NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is an American civil rights organization formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. B. Du&nbs ...

, Judge John Santora sentenced him to 90 days in jail.

Hurricanes

Jacksonville has been largely spared from the impacts ofhurricane

A tropical cyclone is a rapidly rotating storm system with a low-pressure area, a closed low-level atmospheric circulation, strong winds, and a spiral arrangement of thunderstorms that produce heavy rain and squalls. Depending on its ...

s. Hurricane Dora made landfall near St. Augustine, Florida on September 11, 1964, with winds of , becoming the first on record to make landfall in the region. Despite the storm damage, over 20,000 fans attended a live concert the next day at the Gator Bowl Stadium

The Gator Bowl was an American football stadium located in Jacksonville, Florida. Originally built in 1927, all but a small portion of the facility was razed in 1994 in preparation for the 1995 Jacksonville Jaguars season, inaugural season of the ...

by the British rock-and-roll band, "The Beatles

The Beatles were an English Rock music, rock band formed in Liverpool in 1960. The core lineup of the band comprised John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr. They are widely regarded as the Cultural impact of the Beatle ...

". The winds were blowing so hard that Ringo Starr

Sir Richard Starkey (born 7 July 1940), known professionally as Ringo Starr, is an English musician, songwriter and actor who achieved international fame as the drummer for the Beatles. Starr occasionally sang lead vocals with the group, us ...

's drum set had to be nailed down to the stage.

Dora was the only storm in recorded history to affect Jacksonville with hurricane-force winds, though the city has been affected by weaker storms as well as hurricanes that lost intensity before reaching the area. In September 1999, after Hurricane Floyd

Hurricane Floyd was a very powerful and large tropical cyclone which struck the Bahamas and the East Coast of the United States. It was the sixth list of named tropical cyclones, named storm, fourth hurricane, and third major hurricane in the 1 ...

struck the Bahamas

The Bahamas, officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic and island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the Atlantic Ocean. It contains 97 per cent of the archipelago's land area and 88 per cent of ...

, over one million Floridians were evacuated from coastal areas, many of them from Jacksonville. Mayor John Delaney announced the mandatory evacuation of the Jacksonville Beaches and other low lying neighborhoods early on September 14; in total, nearly 80,000 Jacksonville residents left their homes. Ultimately the storm turned northward 125 miles off the coast, causing only minor damage in Jacksonville and the southeastern U.S. before making landfall in North Carolina

North Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, South Carolina to the south, Georgia (U.S. stat ...

. In September 2017, Jacksonville experienced record flooding from Hurricane Irma

Hurricane Irma was an extremely powerful and devastating tropical cyclone that was the first Category 5 hurricane to strike the Leeward Islands on record, followed by Hurricane Maria, Maria two weeks later. At the time, it was considered ...

.

Consolidation

Through the 1960s Jacksonville, like most other large cities in the US, suffered from the effects ofurban sprawl

Urban sprawl (also known as suburban sprawl or urban encroachment) is defined as "the spreading of urban developments (such as houses and shopping centers) on undeveloped land near a city". Urban sprawl has been described as the unrestricted ...

. To compensate for the loss of population and tax revenue and end waste and corruption, voters elected to consolidate the government of Jacksonville with the government of Duval County. The move was carried out on October 1, 1968, and Hans Tanzler, elected mayor of Jacksonville the year before, became the first mayor of the consolidated government. Jacksonville became the largest city in Florida and the 13th largest in the United States, and has a greater land area than any other American city outside Alaska

Alaska ( ) is a non-contiguous U.S. state on the northwest extremity of North America. Part of the Western United States region, it is one of the two non-contiguous U.S. states, alongside Hawaii. Alaska is also considered to be the north ...

. All areas of Duval County are considered part of Jacksonville besides the four independent municipalities of Jacksonville Beach, Atlantic Beach, Neptune Beach, and Baldwin, although residents of these towns vote in city elections and are eligible for services provided by Jacksonville.

Claude Yates began the "quiet revolution" with the ''Yates Manifesto'' and J. J. Daniel was chairman of the ''Local Government Study Commission''. Lex Hester was Executive Director of the commission and the key architect of Jacksonville's consolidated government, transition coordinator and chief administrative officer following consolidation.

See also

* List of people from Jacksonville, Florida * Timeline of Jacksonville, Florida * History of African Americans in JacksonvilleBibliography

* Bartley, Abel A. ''Keeping the Faith: Race, Politics, and Social Development in Jacksonville, Florida, 1940–1970.'' (2000). 177 pponline edition

References

External links

Photographic exhibit on the Great Fire of 1901

presented by the State Archives of Florida.

The Jacksonville Historical Society

{{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Jacksonville, Florida