History Of Ireland (1801–1923) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Some members of the Repeal Association, called the

Some members of the Repeal Association, called the

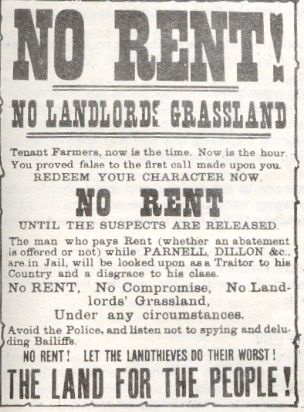

In the wake of the famine, many thousands of Irish peasant farmers and labourers either died or left the country. Those who remained waged a long campaign for better rights for tenant farmers and ultimately for land re-distribution. This period, known as the "

In the wake of the famine, many thousands of Irish peasant farmers and labourers either died or left the country. Those who remained waged a long campaign for better rights for tenant farmers and ultimately for land re-distribution. This period, known as the " The most effective tactic of the Land League was the

The most effective tactic of the Land League was the

Until the 1870s, most Irish people elected as their Members of Parliament (MPs) Liberals and

Until the 1870s, most Irish people elected as their Members of Parliament (MPs) Liberals and

For three years, from 1919 to 1921, acting largely on its own authority and independently of the Dáil assembly, the

For three years, from 1919 to 1921, acting largely on its own authority and independently of the Dáil assembly, the

de Valera stated in a speech n Killarney in March 1922, that if the Treaty was accepted by the electorate,

"IRA men will have to march over the dead bodies of their own brothers.

They will have to wade through Irish blood." opposed the treaty on the grounds that: * it had abolished the Irish Republic proclaimed in 1916, established under the First Dáil, * it imposed the controversial Dominion Oath of Allegiance (to the Irish Free State) and Fidelity (to the King) on Irish parliamentarians, and * it accepted the partition of the island and failed to create a fully independent republic. De Valera led his supporters out of the Dáil and, after a lapse of six months in which the IRA also split, a bloody

online edition

* Canny, Nicholas. ''From Reformation to Restoration: Ireland, 1534–1660'' (Dublin, 1987) * Cleary, Joe, and Claire Connolly, eds. ''The Cambridge Companion to Modern Irish Culture'' (2005) * Connolly, S. J. ed. ''The Oxford Companion to Irish History'' (1998

online edition

* Donnelly, James S., ed. ''Encyclopedia of Irish History and Culture.'' Macmillan Reference USA, 2004. 1084 pp. * Edwards, Ruth Dudley. ''An Atlas of Irish History.'' 2d ed. Methuen, 1981. 286 pp. * Fleming, N. C. and O'Day, Alan. ''The Longman Handbook of Modern Irish History since 1800.'' 2005. 808 pp. * Foster, R. F. ''Modern Ireland, 1600–1972'' (1988) * Foster, R. F., ed. ''The Oxford Illustrated History of Ireland.'' Oxford U. Press, 1989. 382 pp. * Foster, R. F. ''Vivid Faces: The Revolutionary Generation in Ireland, 1890–1923'' (2015

excerpt

* Fry, Peter and Fry, Fiona Somerset. ''A History of Ireland.'' Routledge, 1989. 366 pp. * Hachey, Thomas E., Joseph M. Hernon Jr., Lawrence J. McCaffrey; ''The Irish Experience: A Concise History'' M. E. Sharpe, 199

online edition

* Hayes, Alan and Urquhart, Diane, eds. ''Irish Women's History.'' (Dublin: Irish Academic Press, 2004.) 240 pp. * Hickey, D. J. and Doherty, J. E. ''A Dictionary of Irish History since 1800.'' Barnes & Noble, 1980. 615 pp. * Jackson, Alvin. ''Ireland: 1798–1998'' (1999) * Johnson, Paul. ''Ireland: Land of Troubles: A History from the Twelfth Century to the Present Day.'' Holmes & Meier, 1982. 224 pp. * * Larkin, Hilary. ''A History of Ireland, 1800–1922: Theatres of Disorder?'' (Anthem Press, 2014). * Lee, J. J. ''Ireland 1912–1985'' (1989) * Luddy, Maria. ''Women in Ireland, 1800–1918: A Documentary History. '' Cork U. Press, 1995. 356 pp. * McCormack, W. J. ed. ''The Blackwell Companion to Modern Irish Culture'' (2002) * Mokyr, Joel. ''Why Ireland Starved: A Quantitative and Analytical History of the Irish Economy, 1800–1850.'' Allen & Unwin, 1983. 330 pp

online edition

* Moody, T. W.; Martin, F. X.; and Byrne, F. J., eds. ''A New History of Ireland. Vol. 8: A Chronology of Irish History to 1976: A Companion to Irish History, Part 1.'' Oxford U. Press, 1982. 591 pp * Newman, Peter R. ''Companion to Irish History, 1603–1921: From the Submission of Tyrone to Partition.'' Facts on File, 1991. 256 pp * ÓGráda, Cormac. ''Ireland: A New Economic History, 1780–1939.'' Oxford U. Press, 1994. 536 pp. * Ranelagh, John O'Beirne. ''A Short History of Ireland.'' Cambridge U. Press, 1983. 272 pp. * Ranelagh, John. ''Ireland: An Illustrated History. '' Oxford U. Press, 1981. 267 pp. * * Vaughan, W. E., ed. ''A New History of Ireland. Vol. 5: Ireland under the Union, I, 1801–70.'' Oxford U. Press, 1990. 839 pp. * Vaughan, W. E., ed. ''A New History of Ireland. Vol. 6: Ireland under the Union. Part 2: 1870–1921.'' Oxford U. Press, 1996. 957 pp.

Allen & Unwin, 1973. *''Young Ireland and 1848'', Dennis Gwynn, Cork University Press 1949. *''Daniel O'Connell The Irish Liberator'', Dennis Gwynn, Hutchinson & Co, Ltd. *''The Fenians in Context Irish Politics & Society 1848–82'', R. V. Comerford, Wolfhound Press 1998 *''William Smith O'Brien and the Young Ireland Rebellion of 1848'', Robert Sloan, Four Courts Press 2000 *''Ireland Her Own'', T. A. Jackson, Lawrence & Wishart Ltd 1976. *''Paddy's Lament Ireland 1846–1847 Prelude to Hatred'', Thomas Gallagher, Poolbeg 1994. *''The Great Shame'', Thomas Keneally, Anchor Books 1999. *''James Fintan Lalor'', Thomas, P. O'Neill, Golden Publications 2003. *''Michael Collins, The Man Who Won The War'', T. Ryle Dwyer, Mercier Press, Ireland 1990 *''A History of Ireland'', Mike Cronin, Palgrave Publishers Ltd. 2002

An Gorta Mor

''Quinnipiac University''

19th Century Pamphlet Collection.

Collection of 19th-century pamphlets, predominantly of Irish interest and covering a broad spectrum of subjects. A UCD Digital Library Collection.

19th Century Social History Pamphlets Collection.

Collection of pamphlets relating to 19th-century Irish social history, particularly the themes of education, health, famine, poverty, business, and communications. A UCD Digital Library Collection. {{DEFAULTSORT:History of Ireland 1801-1923 * *

Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

was part of the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

from 1801 to 1922. For almost all of this period, the island was governed by the UK Parliament

The Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, and may also legislate for the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of ...

in London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

through its Dublin Castle administration in Ireland

Dublin Castle was the centre of the government of Ireland under English and later British rule. "Dublin Castle" is used metonymically to describe British rule in Ireland. The Castle held only the executive branch of government and the Privy Cou ...

. Ireland underwent considerable difficulties in the 19th century, especially the Great Famine of the 1840s which started a population decline that continued for almost a century. The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw a vigorous campaign for Irish Home Rule. While legislation enabling Irish Home Rule was eventually passed, militant and armed opposition from Irish unionists, particularly in Ulster

Ulster (; or ; or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional or historic provinces of Ireland, Irish provinces. It is made up of nine Counties of Ireland, counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kingdom); t ...

, opposed it. Proclamation was shelved for the duration following the outbreak of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. By 1918, however, moderate Irish nationalism

Irish nationalism is a nationalist political movement which, in its broadest sense, asserts that the people of Ireland should govern Ireland as a sovereign state. Since the mid-19th century, Irish nationalism has largely taken the form of cult ...

had been eclipsed by militant republican separatism. In 1919, war broke out between republican separatists and British Government forces. Subsequent negotiations between Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( ; ; ) is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active in both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The History of Sinn Féin, original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur Griffit ...

, the major Irish party, and the UK government led to the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty

The 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty (), commonly known in Ireland as The Treaty and officially the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland, was an agreement between the government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain an ...

, which resulted in five-sixths of the island seceding from the United Kingdom, becoming the Irish Free State

The Irish Free State (6 December 192229 December 1937), also known by its Irish-language, Irish name ( , ), was a State (polity), state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-ye ...

(now the Republic of Ireland

Ireland ( ), also known as the Republic of Ireland (), is a country in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe consisting of 26 of the 32 Counties of Ireland, counties of the island of Ireland, with a population of about 5.4 million. ...

), with only the six northeastern counties remaining within the United Kingdom.

Acts of Union, politics from 1801-1922

Ireland opened the 19th century still reeling from the after-effects of theIrish Rebellion of 1798

The Irish Rebellion of 1798 (; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ''The Turn out'', ''The Hurries'', 1798 Rebellion) was a popular insurrection against the British Crown in what was then the separate, but subordinate, Kingdom of Ireland. The m ...

. Prisoners were still being deported to Australia and sporadic violence continued in County Wicklow

County Wicklow ( ; ) is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. The last of the traditional 32 counties, having been formed as late as 1606 in Ireland, 1606, it is part of the Eastern and Midland Region and the Provinces ...

. There was another abortive rebellion led by Robert Emmet

Robert Emmet (4 March 177820 September 1803) was an Irish Republican, orator and rebel leader. Following the suppression of the United Irish uprising in 1798, he sought to organise a renewed attempt to overthrow the British Crown and Prote ...

in 1803. The Acts of Union, which constitutionally made Ireland part of the British state, can largely be seen as an attempt to redress some of the grievances behind the 1798 rising and to prevent it from destabilising Britain or providing a base for foreign invasion.

In 1800 the Irish Parliament and the Parliament of Great Britain

The Parliament of Great Britain was formed in May 1707 following the ratification of the Acts of Union 1707, Acts of Union by both the Parliament of England and the Parliament of Scotland. The Acts ratified the treaty of Union which created a ...

each passed an Act of Union which, from 1 January 1801, abolished the Irish legislature and merged the Kingdom of Ireland

The Kingdom of Ireland (; , ) was a dependent territory of Kingdom of England, England and then of Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain from 1542 to the end of 1800. It was ruled by the monarchs of England and then List of British monarchs ...

and the Kingdom of Great Britain

Great Britain, also known as the Kingdom of Great Britain, was a sovereign state in Western Europe from 1707 to the end of 1800. The state was created by the 1706 Treaty of Union and ratified by the Acts of Union 1707, which united the Kingd ...

to create the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was the union of the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland into one sovereign state, established by the Acts of Union 1800, Acts of Union in 1801. It continued in this form until ...

.

After one failed attempt, the passage of the act in the Irish parliament was finally achieved, albeit, as with the 1707 Acts of Union

The Acts of Union refer to two acts of Parliament, one by the Parliament of Scotland in March 1707, followed shortly thereafter by an equivalent act of the Parliament of England. They put into effect the international Treaty of Union agre ...

that united Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

and England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

, with the mass bribery of members of both houses, who were awarded British peerage

A peerage is a legal system historically comprising various hereditary titles (and sometimes Life peer, non-hereditary titles) in a number of countries, and composed of assorted Imperial, royal and noble ranks, noble ranks.

Peerages include:

A ...

s and other "encouragements".

In this period, the administration of Ireland consisted of authorities appointed by the central British government. These were the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland

Lord Lieutenant of Ireland (), or more formally Lieutenant General and General Governor of Ireland, was the title of the chief governor of Ireland from the Williamite Wars of 1690 until the Partition of Ireland in 1922. This spanned the K ...

, who represented the King, and the Chief Secretary for Ireland

The Chief Secretary for Ireland was a key political office in the British Dublin Castle administration, administration in Ireland. Nominally subordinate to the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, Lord Lieutenant, and officially the "Chief Secretar ...

appointed by the British Prime Minister. Almost equally important was the Under Secretary for Ireland

The Under-Secretary for Ireland (Permanent Under-Secretary to the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland) was the permanent head (or most senior civil servant) of the Dublin Castle administration, British administration in Ireland prior to the establishment o ...

, who headed up the civil service in Ireland.

As the century went on, the UK Parliament and Cabinet took over from the monarch as the legislative and executive branches of government, respectively. For this reason, in Ireland, the Chief Secretary became more important than the Lord Lieutenant, who became of more symbolic than real importance. After the abolition of the Irish Parliament, Irish Members of Parliament were elected to the House of Commons of the United Kingdom

The House of Commons is the lower house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the upper house, the House of Lords, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England. The House of Commons is an elected body consisting of 650 memb ...

in Westminster.

The British Administration in Ireland – known by metonymy

Metonymy () is a figure of speech in which a concept is referred to by the name of something associated with that thing or concept. For example, the word " suit" may refer to a person from groups commonly wearing business attire, such as sales ...

as "Dublin Castle

Dublin Castle () is a major Government of Ireland, Irish government complex, conference centre, and tourist attraction. It is located off Dame Street in central Dublin.

It is a former motte-and-bailey castle and was chosen for its position at ...

" – remained largely dominated by the Anglo-Irish

Anglo-Irish people () denotes an ethnic, social and religious grouping who are mostly the descendants and successors of the English Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland. They mostly belong to the Anglican Church of Ireland, which was the State rel ...

establishment until its removal from Dublin in 1922.

Catholic Emancipation

Part of the Union's attraction for many Irish Catholics and Dissenters was the promised abolition of the remaining Penal Laws then in force (which discriminated against them), and the granting of Catholic Emancipation. However, KingGeorge III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland, Ireland from 25 October 1760 until his death in 1820. The Acts of Union 1800 unified Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and ...

blocked emancipation, believing that to grant it would break his coronation oath to defend the Anglican

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

church. A campaign under the Irish Catholic lawyer and politician Daniel O'Connell

Daniel(I) O’Connell (; 6 August 1775 – 15 May 1847), hailed in his time as The Liberator, was the acknowledged political leader of Ireland's Roman Catholic majority in the first half of the 19th century. His mobilisation of Catholic Irelan ...

and the Catholic Association

The Catholic Association was an Irish Roman Catholic political organization set up by Daniel O'Connell in the early nineteenth century to campaign for Catholic emancipation within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was one of ...

led to renewed agitation for the abolition of the Test Act. Arthur Wellesley, the Anglo-Irish soldier and statesman and First Duke of Wellington, was at the peak of his enormous prestige as the victor of the Napoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

. As Prime Minister he used his considerable political power and influence to steer the enabling legislation through the UK Parliament. He then persuaded King George IV to sign the Act into law under threat of resignation. The Roman Catholic Relief Act 1829

The Roman Catholic Relief Act 1829 ( 10 Geo. 4. c. 7), also known as the Catholic Emancipation Act 1829, was an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that removed the sacramental tests that barred Roman Catholics in the United Kingdom f ...

, allowed British and Irish Catholics to sit in the Parliament. Daniel O'Connell became the first Catholic MP to be seated since 1689. As head of the Repeal Association

The Repeal Association was an Irish mass membership political movement set up by Daniel O'Connell in 1830 to campaign for a repeal of the Acts of Union of 1800 between Great Britain and Ireland.

The Association's aim was to revert Ireland to ...

, O'Connell mounted an unsuccessful campaign for the repeal of the Act of Union and the restoration of Irish self-government.

O'Connell's tactics were largely peaceful, using mass rallies to show the popular support for his campaign. While O'Connell failed to gain repeal of the Union, his efforts led to reforms in matters such as local government and the Poor Laws

The English Poor Laws were a system of poor relief in England and Wales that developed out of the codification of late-medieval and Tudor-era laws in 1587–1598. The system continued until the modern welfare state emerged in the late 1940s.

E ...

.

Despite O'Connell's peaceful methods, there was also a good deal of sporadic violence and rural unrest in the country in the first half of the 19th century. In Ulster

Ulster (; or ; or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional or historic provinces of Ireland, Irish provinces. It is made up of nine Counties of Ireland, counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kingdom); t ...

, there were repeated outbreaks of sectarian violence, such as the riot at Dolly's Brae, between Catholics and the nascent Orange Order

The Loyal Orange Institution, commonly known as the Orange Order, is an international Protestant fraternal order based in Northern Ireland and primarily associated with Ulster Protestants. It also has lodges in England, Grand Orange Lodge of ...

. Elsewhere, tensions between the rapidly growing rural population on one side and their landlords and the state on the other gave rise to much agrarian violence and social unrest. Secret peasant societies such as the Whiteboys

The Whiteboys () were a secret Irish agrarian organisation in 18th-century Ireland which defended tenant-farmer land-rights for subsistence farming. Their name derives from the white smocks that members wore in their nighttime raids. Becaus ...

and the Ribbonmen used sabotage and violence to intimidate landlords into better treatment of their tenants. The most sustained outbreak of violence was the Tithe War of the 1830s, over the obligation of the mostly Catholic peasantry to pay tithes to the Protestant Church of Ireland

The Church of Ireland (, ; , ) is a Christian church in Ireland, and an autonomy, autonomous province of the Anglican Communion. It is organised on an all-Ireland basis and is the Christianity in Ireland, second-largest Christian church on the ...

. The Royal Irish Constabulary

The Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC, ; simply called the Irish Constabulary 1836–67) was the police force in Ireland from 1822 until 1922, when all of the island was part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom. A sep ...

(RIC) was set up to police rural areas in response to this violence.

Socioeconomic situation 1800-1840

There were economic booms during theNapoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

(1803–15). Most people in pre-famine Ireland had little or no access to land. Landless laborers or cottiers comprised the single most common profession in the 1841 census, when 40% of Irish houses "were one room mud cabins with natural earth floors, no windows and no chimneys".

The Great Famine, 1845-1851

Ireland underwent major highs and lows economically during the 19th century; from economic booms during theNapoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

to severe economic downturns and a series of famines, the last threatening in 1879. The worst of these was the Great Irish Famine

The Great Famine, also known as the Great Hunger ( ), the Famine and the Irish Potato Famine, was a period of mass starvation and disease in Ireland lasting from 1845 to 1852 that constituted a historical social crisis and had a major impact o ...

(1845–1851), in which about one million people died and another million emigrated.

The economic problems of most Irish people were in part the result of the small size of their landholdings and a large increase in the population in the years before the famine. In particular, both the law and social tradition provided for subdivision of land, with all sons inheriting equal shares in a farm, meaning that farms became so small that only one crop, potatoes, could be grown in sufficient amounts to feed a family. Furthermore, many estates, from whom the small farmers rented, were poorly run by absentee landlords and in many cases heavily mortgaged. Enclosures of land since the start of the 19th century had also exacerbated the problem, and the extensive grazing of cattle had contributed to the decrease in size in the plots of land available to tenants to raise their crops.

In the new Whig government (from 1846), Charles Trevelyan became assistant secretary to the Treasury, and largely responsible for the British Government's response to the famine in Ireland. When potato blight hit the island in 1845, much of the rural population was left without food. At this time, the then Prime Minister Lord John Russell

John Russell, 1st Earl Russell (18 August 1792 – 28 May 1878), known as Lord John Russell before 1861, was a British Whig and Liberal statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1846 to 1852 and again from 1865 to 186 ...

adhered to a strict ''laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( , from , ) is a type of economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies or regulations). As a system of thought, ''laissez-faire'' ...

'' economic policy it has been claimed, which maintained that further state intervention would have the whole country dependent on hand-outs, and that what was needed was for economic viability to be encouraged. The government of Lord John Russell

John Russell, 1st Earl Russell (18 August 1792 – 28 May 1878), known as Lord John Russell before 1861, was a British Whig and Liberal statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1846 to 1852 and again from 1865 to 186 ...

attempted to raise a loan of £8 million and intended a further loan but this provoked a financial crisis

A financial crisis is any of a broad variety of situations in which some financial assets suddenly lose a large part of their nominal value. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, many financial crises were associated with Bank run#Systemic banki ...

made worse by demand for funds for railways and food imports. The crisis prevented the expending of the loan if the pound was to remain convertible to gold and government funding was slashed in 1847 and the costs of relief transferred to local taxes in Ireland.

Despite Ireland producing a net surplus of food, most of it was exported to England and elsewhere. Public works schemes were set up but proved inadequate, and the situation became catastrophic when epidemics of typhoid

Typhoid fever, also known simply as typhoid, is a disease caused by ''Salmonella enterica'' serotype Typhi bacteria, also called ''Salmonella'' Typhi. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often ther ...

, cholera

Cholera () is an infection of the small intestine by some Strain (biology), strains of the Bacteria, bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea last ...

and dysentery

Dysentery ( , ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications may include dehyd ...

took hold. About £2,000,000 was donated all over the world by charities and private donors, including the Choctaw

The Choctaw ( ) people are one of the Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States, originally based in what is now Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama. The Choctaw language is a Western Muskogean language. Today, Choct ...

people in the US, former slaves in the Caribbean, Sultan Abdülmecid I of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

, Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in January 1901. Her reign of 63 year ...

, and future Tsar Alexander II of Russia

Alexander II ( rus, Алекса́ндр II Никола́евич, Aleksándr II Nikoláyevich, p=ɐlʲɪˈksandr ftɐˈroj nʲɪkɐˈlajɪvʲɪtɕ; 29 April 181813 March 1881) was Emperor of Russia, Congress Poland, King of Poland and Grand Du ...

. However the inadequate nature of the British Government

His Majesty's Government, abbreviated to HM Government or otherwise UK Government, is the central government, central executive authority of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

's initiatives led to a problem becoming a catastrophe.

Emigration was not uncommon in Ireland in the years preceding the Famine. Between 1815 and 1845, Ireland had already established itself as the major supplier of overseas labour to Great Britain and North America.Fitzpatrick, David. ''Irish Emigration 1801–1921'', 3 However, emigration reached a peak during the famine, particularly in the years 1846–1855. The famine also saw increased emigration to Canada and assisted passages to Australia. Because of ongoing political tensions between the US and the UK, the resulting large and influential Irish American

Irish Americans () are Irish ethnics who live within in the United States, whether immigrants from Ireland or Americans with full or partial Irish ancestry.

Irish immigration to the United States

From the 17th century to the mid-19th c ...

diaspora

A diaspora ( ) is a population that is scattered across regions which are separate from its geographic place of birth, place of origin. The word is used in reference to people who identify with a specific geographic location, but currently resi ...

created, financed and encouraged the Irish independence movement. In 1858, the Irish Republican Brotherhood

The Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB; ) was a secret oath-bound fraternal organisation dedicated to the establishment of an "independent democratic republic" in Ireland between 1858 and 1924.McGee, p. 15. Its counterpart in the United States ...

(IRB, also known as the Fenians

The word ''Fenian'' () served as an umbrella term for the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) and their affiliate in the United States, the Fenian Brotherhood. They were secret political organisations in the late 19th and early 20th centurie ...

) was founded as a secret society dedicated to armed rebellion against the British. A related organisation formed in New York was known as Clan na Gael

Clan na Gael (CnG) (, ; "family of the Gaels") is an Irish republican organization, founded in the United States in the late 19th and 20th centuries, successor to the Fenian Brotherhood and a sister organization to the Irish Republican Bro ...

, which several times organised raids into the British Province of Canada

The Province of Canada (or the United Province of Canada or the United Canadas) was a British colony in British North America from 1841 to 1867. Its formation reflected recommendations made by John Lambton, 1st Earl of Durham, in the Report ...

. While the Fenians had a considerable presence in rural Ireland, the Fenian Rising

The Fenian Rising of 1867 (, ) was a rebellion against British rule in Ireland, organised by the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB).

After the suppression of the ''Irish People'' newspaper in September 1865, disaffection among Irish radical n ...

launched in 1867 was a fiasco. Moreover, wider support for Irish republicanism

Irish republicanism () is the political movement for an Irish Republic, Irish republic, void of any British rule in Ireland, British rule. Throughout its centuries of existence, it has encompassed various tactics and identities, simultaneously ...

, in the face of harsh laws against sedition

Sedition is overt conduct, such as speech or organization, that tends toward rebellion against the established order. Sedition often includes subversion of a constitution and incitement of discontent toward, or insurrection against, establ ...

, was minimal in the period.

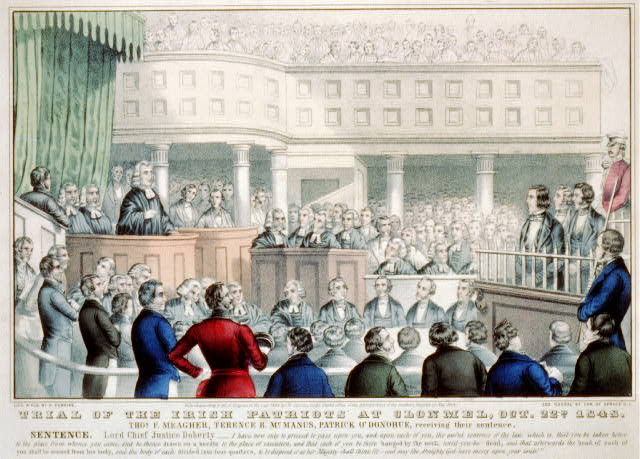

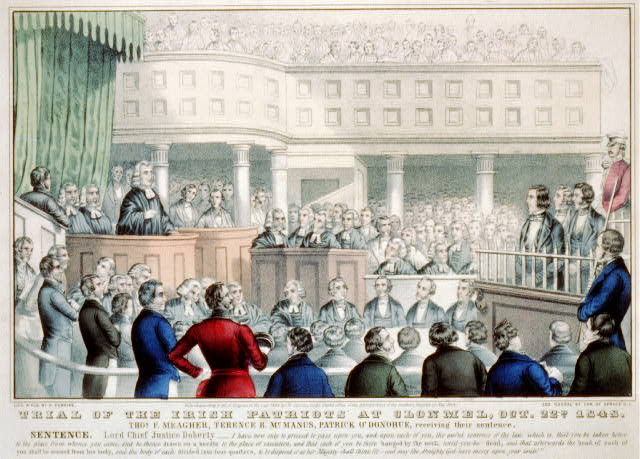

Young Irelander Rebellion

Some members of the Repeal Association, called the

Some members of the Repeal Association, called the Young Irelanders

Young Ireland (, ) was a political and cultural movement in the 1840s committed to an all-Ireland struggle for independence and democratic reform. Grouped around the Dublin weekly ''The Nation'', it took issue with the compromises and clerical ...

, formed the Irish Confederation

The Irish Confederation was an Irish nationalist independence movement, established on 13 January 1847 by members of the Young Ireland movement who had seceded from Daniel O'Connell's Repeal Association. Historian T. W. Moody described it as "t ...

and tried to launch a rebellion

Rebellion is an uprising that resists and is organized against one's government. A rebel is a person who engages in a rebellion. A rebel group is a consciously coordinated group that seeks to gain political control over an entire state or a ...

against British rule in 1848. This coincided with the worst years of the famine and was contained by British military action. William Smith O'Brien

William Smith O'Brien (; 17 October 1803 – 18 June 1864) was an Irish republicanism, Irish republican who, in the course of Ireland's Great Famine (Ireland), Great Famine, had been converted to the cause of Irish nationalism, national i ...

, leader of the Confederates, failed to capture a party of police barricaded in Widow McCormack's house, who were holding her children as hostages, marking the effective end of the revolt. Although intermittent resistance continued until late 1849, O'Brien and his colleagues were quickly arrested. Originally sentenced to death, this sentence was later commuted to transportation to Van Diemen's Land

Van Diemen's Land was the colonial name of the island of Tasmania during the European exploration of Australia, European exploration and colonisation of Australia in the 19th century. The Aboriginal Tasmanians, Aboriginal-inhabited island wa ...

, where they joined John Mitchel

John Mitchel (; 3 November 1815 – 20 March 1875) was an Irish nationalism, Irish nationalist writer and journalist chiefly renowned for his indictment of British policy in Ireland during the years of the Great Famine (Ireland), Great Famin ...

.

Land agitation and agrarian resurgence

Land War

The Land War () was a period of agrarian agitation in rural History of Ireland (1801–1923), Ireland (then wholly part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom) that began in 1879. It may refer specifically to the firs ...

" in Ireland, had a nationalist as well as a social element. The reason for this was that the land-owning class in Ireland, since the period of the 17th century Plantations of Ireland

Plantation (settlement or colony), Plantations in 16th- and 17th-century Ireland () involved the confiscation of Irish-owned land by the Kingdom of England, English The Crown, Crown and the colonisation of this land with settlers from Great Br ...

, had been composed of Protestant settlers, originally from England, who had a British identity. The Irish (Roman Catholic) population widely believed that the land had been unjustly taken from their ancestors and given to this Protestant Ascendancy

The Protestant Ascendancy (also known as the Ascendancy) was the sociopolitical and economical domination of Ireland between the 17th and early 20th centuries by a small Anglicanism, Anglican ruling class, whose members consisted of landowners, ...

during the English conquest of the country.

The Irish National Land League

The Irish National Land League ( Irish: ''Conradh na Talún''), also known as the Land League, was an Irish political organisation of the late 19th century which organised tenant farmers in their resistance to exactions of landowners. Its prima ...

, was formed to defend the interests of tenant farmers, at first demanding the "Three Fs

Free sale, fixity of tenure, and fair rent, also known as the Three Fs, were a set of demands first issued by the Tenant Right League during their campaign for land reform in Ireland starting in the 1850s. They were:

* Free sale—meaning a tena ...

" – Fair rent, Free sale and Fixity of tenure. Members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood

The Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB; ) was a secret oath-bound fraternal organisation dedicated to the establishment of an "independent democratic republic" in Ireland between 1858 and 1924.McGee, p. 15. Its counterpart in the United States ...

, such as Michael Davitt

Michael Davitt (25 March 1846 – 30 May 1906) was an Irish republicanism, Irish republican activist for a variety of causes, especially Home Rule (Ireland), Home Rule and land reform. Following an eviction when he was four years old, Davitt's ...

, were prominent among the leadership of this movement. When they saw its potential for popular mobilisation, nationalist leaders such as Charles Stewart Parnell

Charles Stewart Parnell (27 June 1846 – 6 October 1891) was an Irish nationalist politician who served as a Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), Member of Parliament (MP) in the United Kingdom from 1875 to 1891, Leader of the Home Rule Leag ...

also became involved.boycott

A boycott is an act of nonviolent resistance, nonviolent, voluntary abstention from a product, person, organisation, or country as an expression of protest. It is usually for Morality, moral, society, social, politics, political, or Environmenta ...

(the word originates in Ireland in this period), where unpopular landlords were ostracised by the local community. Grassroots Land League members used violence against landlords and their property; attempted evictions of tenant farmers regularly turned into armed confrontations. Under the British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield (21 December 1804 – 19 April 1881) was a British statesman, Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician and writer who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. He played a ...

, an Irish Coercion Act

A Coercion Act was an Act of Parliament that gave a legal basis for increased state powers to suppress popular discontent and disorder. The label was applied, especially in Ireland, to acts passed from the 18th to the early 20th century by the ...

was first introduced – a form of martial law – to contain the violence. Parnell, Davitt, William O'Brien

William O'Brien (2 October 1852 – 25 February 1928) was an Irish nationalist, journalist, agrarian agitator, social revolutionary, politician, party leader, newspaper publisher, author and Member of Parliament (MP) in the House of Commons of ...

and the other leaders of the Land League were temporarily imprisoned – being held responsible for the violence.

Ultimately, the land question was settled through successive Irish Land Acts by the United Kingdom – beginning with the Landlord and Tenant (Ireland) Act 1870

The Landlord and Tenant (Ireland) Act 1870 (33 & 34 Vict. c. 46) was an Act of Parliament (UK), act passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom in 1870.

Background

Between the Acts of Union 1800 and the year 1870, Parliament had passed ma ...

and the Land Law (Ireland) Act 1881

The Land Law (Ireland) Act 1881 (44 & 45 Vict. c. 49) was the second Land Acts (Ireland), Irish land act passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom.

Background

The Liberal Party (UK), Liberal government of William Ewart Gladstone had previ ...

of William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British politican, starting as Conservative MP for Newark and later becoming the leader of the Liberal Party (UK), Liberal Party.

In a career lasting over 60 years, he ...

, which first gave extensive rights to tenant farmers, then the Wyndham Land Purchase (Ireland) Act 1903

The Land Acts (officially Land Law (Ireland) Acts) were a series of measures to deal with the question of tenancy contracts and peasant proprietorship of land in Ireland in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Five such acts were introduced by ...

won by William O'Brien after the 1902 Land Conference, enabling tenant farmers purchase their plots of land from their landlords, the problems of non-existent rural housing resolved by D. D. Sheehan under the Bryce Labourers (Ireland) Act (1906). These acts created a very large class of small property owners in the Irish countryside, and dissipated the power of the old Anglo-Irish landed class. The 1908 J.J. Clancy Town Housing Act then advanced the building of urban council housing.

Unrest and agitation also resulted in the successful introduction of agricultural co-operatives through the initiative of Horace Plunkett

Sir Horace Curzon Plunkett (24 October 1854 – 26 March 1932), was an Anglo-Irish agricultural reformer, pioneer of agricultural cooperatives, Unionist MP, supporter of Home Rule, Irish Senator and author.

Plunkett, a younger brother of J ...

, but the most positive changes came after the introduction of the Local Government (Ireland) Act 1898

The Local Government (Ireland) Act 1898 ( 61 & 62 Vict. c. 37) was an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland that established a system of local government in Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots diale ...

which put the control and running of rural affairs into local hands. However, it did not end support for independent Irish nationalism, as British Governments had hoped. After Independence, Irish governments from 1923 completed a final land settlement under Free State Land Acts. ''See also Irish Land Commission

The Irish Land Commission was created by the British crown in 1843 to "inquire into the occupation of the land in Ireland. The office of the commission was in Dublin Castle, and the records were, on its conclusion, deposited in the records tower ...

.''

Culture and the Gaelic revival

TheCulture of Ireland

The culture of Ireland includes the art, music, dance, folklore, traditional clothing, language, literature, cuisine and sport associated with Ireland and the Irish people. For most of its recorded history, the country’s culture has been ...

underwent a massive change in the course of the 19th century. After the Famine, the Irish language

Irish (Standard Irish: ), also known as Irish Gaelic or simply Gaelic ( ), is a Celtic language of the Indo-European language family. It is a member of the Goidelic languages of the Insular Celtic sub branch of the family and is indigenous ...

went into steep decline. This process was started in the 1830s, when the first National Schools were set up in the country. These had the advantage of encouraging literacy, but classes were provided only in English and the speaking of Irish was prohibited. However, before the 1840s, Irish was still the majority language in the country and numerically (given the rise in population) may have had more speakers than ever before. The Famine devastated the Irish speaking areas of the country, which tended also to be rural and poor. As well as causing the deaths of thousands of Irish speakers, the famine also led to sustained and widespread emigration from the Irish-speaking south and west of the country. By 1900, for the first time in perhaps two millennia, Irish was no longer the majority language in Ireland, and continued to decline in importance. By the time of Irish independence, the Gaeltacht

A ( , , ) is a district of Ireland, either individually or collectively, where the Irish government recognises that the Irish language is the predominant vernacular, or language of the home.

The districts were first officially recognised ...

s had shrunk to small areas along the western seaboard.

In reaction to this, Irish nationalists began a Gaelic revival

The Gaelic revival () was the late-nineteenth-century national revival of interest in the Irish language (also known as Gaelic) and Irish Gaelic culture (including folklore, mythology, sports, music, arts, etc.). Irish had diminished as a sp ...

in the late 19th century, hoping to revive the Irish language and Irish literature and sports. While social organizations such as the Gaelic League

(; historically known in English as the Gaelic League) is a social and cultural organisation which promotes the Irish language in Ireland and worldwide. The organisation was founded in 1893 with Douglas Hyde as its first president, when it eme ...

and the Gaelic Athletic Association

The Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA; ; CLG) is an Irish international amateur sports, amateur sporting and cultural organisation, focused primarily on promoting indigenous Gaelic games and pastimes, which include the traditional Irish sports o ...

were very successful in attracting members, most of their activists were English speakers and the movement did not halt the decline of the Irish language.

The form of English established in Ireland differed somewhat from British English

British English is the set of Variety (linguistics), varieties of the English language native to the United Kingdom, especially Great Britain. More narrowly, it can refer specifically to the English language in England, or, more broadly, to ...

and its variants. Blurring linguistic structures from older forms of English (notably Elizabethan English) and the Irish language, it is known as Hiberno-English

Hiberno-English or Irish English (IrE), also formerly sometimes called Anglo-Irish, is the set of dialects of English native to the island of Ireland. In both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland, English is the first language in e ...

and was strongly associated with early 20th century Celtic Revival

The Celtic Revival (also referred to as the Celtic Twilight) is a variety of movements and trends in the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries that see a renewed interest in aspects of Celtic culture. Artists and writers drew on the traditions of Gae ...

and Irish writers like J.M. Synge, George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from the 188 ...

, Seán O'Casey

Seán O'Casey ( ; born John Casey; 30 March 1880 – 18 September 1964) was an Irish dramatist and memoirist. A committed socialist, he was the first Irish playwright of note to write about the Dublin working classes.

Early life

O'Casey was ...

, and had resonances in the English of Dubliner Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Fflahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 185430 November 1900) was an Irish author, poet, and playwright. After writing in different literary styles throughout the 1880s, he became one of the most popular and influential playwright ...

. Some nationalists saw the celebration of Hiberno-Irish by predominantly Anglo-Irish

Anglo-Irish people () denotes an ethnic, social and religious grouping who are mostly the descendants and successors of the English Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland. They mostly belong to the Anglican Church of Ireland, which was the State rel ...

writers as offensive "stage Irish

Stage Irish, also known as Drunk Irish, or collectively as Paddywhackery, is a Stereotype, stereotyped portrayal of Irish people once common in plays.

" caricature. Synge's play ''The Playboy of the Western World

''The Playboy of the Western World'' is a three-act play written by Irish playwright John Millington Synge, first performed at the Abbey Theatre, Dublin, on 26 January 1907. The work is considered a centerpiece of the Irish Literary Revival mo ...

'' was marked by rioting at performances.

Home Rule movement

Until the 1870s, most Irish people elected as their Members of Parliament (MPs) Liberals and

Until the 1870s, most Irish people elected as their Members of Parliament (MPs) Liberals and Conservatives

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilizati ...

who belonged to the main British political parties. The Conservatives, for example, won a majority in the 1859 general election in Ireland. A significant minority also voted for Unionists, who resisted fiercely any dilution of the Act of Union. In the 1870s a former Conservative barrister turned nationalist

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation,Anthony D. Smith, Smith, A ...

campaigner, Isaac Butt

Isaac Butt (6 September 1813 – 5 May 1879) was an Irish barrister, editor, politician, Member of Parliament in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, economist and the founder and first leader of a number of Irish nationalist par ...

, established a new moderate nationalist movement, the Home Rule League

The Home Rule League (1873–1882), sometimes called the Home Rule Party, was an Irish political party which campaigned for home rule for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, until it was replaced by the Irish Parliam ...

. After his death, William Shaw and in particular a radical young Protestant landowner, Charles Stewart Parnell

Charles Stewart Parnell (27 June 1846 – 6 October 1891) was an Irish nationalist politician who served as a Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), Member of Parliament (MP) in the United Kingdom from 1875 to 1891, Leader of the Home Rule Leag ...

, turned the home rule movement, or the Irish Parliamentary Party

The Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP; commonly called the Irish Party or the Home Rule Party) was formed in 1874 by Isaac Butt, the leader of the Nationalist Party, replacing the Home Rule League, as official parliamentary party for Irish nati ...

(IPP) as it became known, into a major political force. It came to dominate Irish politics, to the exclusion of the previous Liberal, Conservative and Unionist parties that had existed there. The party's growing electoral strength was first shown in the 1880 general election in Ireland, when it won 63 seats (two MPs later defected to the Liberals). By the 1885 general election in Ireland it had won 86 seats (including one in the heavily Irish-populated English city of Liverpool

Liverpool is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. It is situated on the eastern side of the River Mersey, Mersey Estuary, near the Irish Sea, north-west of London. With a population ...

). Parnell's movement proved to be a broad one, from conservative landowners to the Land League

The Irish National Land League ( Irish: ''Conradh na Talún''), also known as the Land League, was an Irish political organisation of the late 19th century which organised tenant farmers in their resistance to exactions of landowners. Its prima ...

.

Parnell's movement also campaigned for the right of Ireland to govern herself as a region within the United Kingdom, in contrast to O'Connell who had wanted a complete repeal of the Act of Union. Two home rule bills (in 1886

Events January

* January 1 – Upper Burma is formally annexed to British rule in Burma, British Burma, following its conquest in the Third Anglo-Burmese War of November 1885.

* January 5–January 9, 9 – Robert Louis Stevenson ...

and 1893) were introduced by Liberal Prime Minister William Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British politican, starting as Conservative MP for Newark and later becoming the leader of the Liberal Party.

In a career lasting over 60 years, he was Prime Minister ...

, but neither became law. Gladstone, says his biographer, "totally rejected the widespread English view that the Irish had no taste for justice, common sense, moderation or national prosperity and looked only to perpetual strife and dissension." The problem for Gladstone was his rural supporters in England would not support home rule for Ireland. A large faction of Liberals, led by Joseph Chamberlain

Joseph Chamberlain (8 July 1836 – 2 July 1914) was a British statesman who was first a radical Liberal Party (UK), Liberal, then a Liberal Unionist after opposing home rule for Ireland, and eventually was a leading New Imperialism, imperial ...

, formed a Unionist faction that supported the Conservative party. The Liberals were out of power and home rule proposals languished.

Home Rule divided Ireland: a significant minority of Unionists (largely based in Ulster) were opposed. The revived Orange Order

The Loyal Orange Institution, commonly known as the Orange Order, is an international Protestant fraternal order based in Northern Ireland and primarily associated with Ulster Protestants. It also has lodges in England, Grand Orange Lodge of ...

mobilized the opposition, warning that a Dublin parliament dominated by Catholics and nationalists would discriminate against them and would impose tariffs on trade with Great Britain. (Whilst most of Ireland was primarily agricultural, north-east Ulster was the location of almost all the island's heavy industry and would have been affected by any tariff barriers imposed by a Dublin parliament.) Intense rioting broke out in Belfast in 1886, as the first Home Rule Bill was being debated.

In 1889, the scandal surrounding Parnell's divorce proceedings split the Irish party, when it became public that Parnell, popularly acclaimed as the 'Uncrowned King of Ireland', had for many years been living in a family relationship with Mrs. Katharine O'Shea

Katharine Parnell (née Wood; 30 January 1846 – 5 February 1921), known before her second marriage as Katharine O'Shea and popularly as Kitty O'Shea, was an English woman of aristocratic background whose adulterous relationship with Irish ...

, the long-separated wife of a fellow MP. When the scandal broke, religious non-conformists in Great Britain, who were the backbone of the pro-Home Rule Liberal Party, forced its leader W. E. Gladstone to abandon support for the Irish cause as long as Parnell remained leader of the IPP. Inside Ireland, the Catholic Church turned against him. Parnell fought for control but lost. He died in 1891. But the Party and the country remained split between pro-Parnellites and anti-Parnellites, who fought each other in elections.

The United Irish League

The United Irish League (UIL) was a nationalist political party in Ireland, launched 23 January 1898 with the motto ''"The Land for the People"''. Its objective to be achieved through agrarian agitation and land reform, compelling larger grazi ...

founded in 1898 forced the reunification of the party to stand under John Redmond

John Edward Redmond (1 September 1856 – 6 March 1918) was an Irish nationalism, Irish nationalist politician, barrister, and Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), MP in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom. He was best known as leader ...

in the 1900 general election. After a brief attempt by the Irish Reform Association

The Irish Reform Association (1904–1905) was an attempt to introduce limited Devolution, devolved self-government to Ireland by a group of reform oriented Unionism in Ireland, Irish unionist Protestant Ascendancy, land owners who proposed to i ...

to introduce devolution

Devolution is the statutory delegation of powers from the central government of a sovereign state to govern at a subnational level, such as a regional or local level. It is a form of administrative decentralization. Devolved territori ...

in 1904, the Irish Party subsequently held the balance of power in the House of Commons after the 1910 general election.

The last obstacle to achieving Home Rule was removed with the Parliament Act 1911

The Parliament Act 1911 ( 1 & 2 Geo. 5. c. 13) is an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It is constitutionally important and partly governs the relationship between the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two Houses of Parl ...

when the House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the lower house, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England. One of the oldest ext ...

lost its power to veto legislation and could only delay a bill for two years. In 1912, with the Irish Parliamentary Party at its zenith, a new third Home Rule Bill was introduced by Prime Minister H. H. Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928) was a British statesman and Liberal Party (UK), Liberal politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1908 to 1916. He was the last ...

, passing its first reading in the Imperial House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

but again defeated in the House of Lords (as with the bill of 1893). During the following two years in which the bill was delayed, debates in the Commons were largely dominated by questions surrounding Home Rule and Ulster Unionists' determined resistance to it. By 1914 the situation had escalated into militancy on both sides, first unionists then nationalists arming and drilling openly, bringing about a Home Rule crisis.

Labour conflicts

Although nationalism dominated Irish politics, social and economic issues were far from absent and came to the fore in the first two decades of the 20th century.Dublin

Dublin is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Situated on Dublin Bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, and is bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, pa ...

was a city marked by extremes of poverty and wealth, being home to several tenement areas and possessing some of the worst slums anywhere in the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

. It also possessed one of the world's biggest "red light districts" known as Monto (after its focal point, Montgomery Street, on the north side of the city).

Unemployment was high in Ireland and worker's pay and conditions were often very poor. In response to this, socialist activists such as James Larkin

James Larkin (28 January 1874 – 30 January 1947), sometimes known as Jim Larkin or Big Jim, was an Irish republicanism, Irish republican, socialist and trade union leader. He was one of the founders of the Irish Labour Party (Ireland), Labou ...

and James Connolly

James Connolly (; 5 June 1868 – 12 May 1916) was a Scottish people, Scottish-born Irish republicanism, Irish republican, socialist, and trade union leader, executed for his part in the Easter Rising, 1916 Easter Rising against British rule i ...

began to organize Trade Unions on syndicalist

Syndicalism is a labour movement within society that, through industrial unionism, seeks to unionize workers according to industry and advance their demands through strikes and other forms of direct action, with the eventual goal of gainin ...

principles.

In 1907, Belfast

Belfast (, , , ; from ) is the capital city and principal port of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan and connected to the open sea through Belfast Lough and the North Channel (Great Britain and Ireland), North Channel ...

saw a bitter strike (by dockers organized by Larkin), in which 10,000 workers went on strike and the police mutinied – a rare instance of non-sectarian mobilization in Ulster. In Dublin, there was an even more vicious dispute – the Dublin Lockout of 1913 – in which over 20,000 workers were fired for belonging to Larkin's Union. Three people died in the rioting that accompanied the lock-out and many more were injured.

However, the labor movement was split into nationalist lines. Southern unions formed the Irish Trades Union Congress

The Irish Trades Union Congress (ITUC) was a union federation covering the island of Ireland.

History

Until 1894, representatives of Irish trade unions attended the British Trades Union Congress (TUC). However, many felt that they had little i ...

whereas those in Ulster affiliated themselves to British unions. Mainstream Irish nationalists were deeply opposed to social radicalism but socialist and labor activists found some sympathy among more extreme Irish Republicans

Irish republicanism () is the political movement for an Irish republic, void of any British rule. Throughout its centuries of existence, it has encompassed various tactics and identities, simultaneously elective and militant and has been both w ...

. James Connolly founded the Irish Citizen Army

The Irish Citizen Army (), or ICA, was a paramilitary group first formed in Dublin to defend the picket lines and street demonstrations of the Irish Transport and General Workers' Union (ITGWU) against the police during the Great Dublin Lock ...

to defend strikers from the police in 1913. In 1916 it participated in the Easter Rising

The Easter Rising (), also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed insurrection in Ireland during Easter Week in April 1916. The Rising was launched by Irish republicans against British rule in Ireland with the aim of establishing an ind ...

alongside the Irish Republican Brotherhood

The Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB; ) was a secret oath-bound fraternal organisation dedicated to the establishment of an "independent democratic republic" in Ireland between 1858 and 1924.McGee, p. 15. Its counterpart in the United States ...

and part of the Irish Volunteers

The Irish Volunteers (), also known as the Irish Volunteer Force or the Irish Volunteer Army, was a paramilitary organisation established in 1913 by nationalists and republicans in Ireland. It was ostensibly formed in response to the format ...

.

Home Rule crisis

Since early 1914, Ireland seemed to be on the brink of civil war between rival private armies, the Nationalist and Unionist Volunteer groups, over the proposed introduction of Home Rule for Ireland. Already in April 1912, 100,000 unionists, led by the barristerSir Edward Carson

Edward Henry Carson, Baron Carson, PC, PC (Ire), KC (9 February 1854 – 22 October 1935), from 1900 to 1921 known as Sir Edward Carson, was an Irish unionist politician, barrister and judge, who was the Attorney General and Solicitor Gen ...

founded the Ulster Volunteers

The Ulster Volunteers was an Irish unionist, loyalist paramilitary organisation founded in 1912 to block domestic self-government ("Home Rule") for Ireland, which was then part of the United Kingdom. The Ulster Volunteers were based in the ...

to resist Home Rule. September saw Carson and James Craig organize the "Ulster Covenant

Ulster's Solemn League and Covenant, commonly known as the Ulster Covenant, was signed by nearly 500,000 people on and before 28 September 1912, in protest against the Third Home Rule Bill introduced by the British Government in the same year.

...

", with over 470,000 signatories pledging to resist Home Rule. This movement then formed the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) in January 1913. In April 1914 30,000 German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

rifles with 3,000,000 rounds were landed at Larne

Larne (, , the name of a Gaelic Ireland, Gaelic territory)Larne/Latharna

Placenames Database of Ireland. is a to ...

, with the authorities blockaded by the UVF (see Larne gunrunning). The Placenames Database of Ireland. is a to ...

Curragh Incident

The Curragh incident of 20 March 1914, sometimes known as the Curragh mutiny, occurred in the Curragh, County Kildare, Ireland. The Curragh Camp was then the main base for the British Army in Ireland, which at the time still formed part of the ...

showed it would be difficult to use the British Army to coerce Ulster into home rule from Dublin. In response, Irish nationalists created the Irish Volunteers

The Irish Volunteers (), also known as the Irish Volunteer Force or the Irish Volunteer Army, was a paramilitary organisation established in 1913 by nationalists and republicans in Ireland. It was ostensibly formed in response to the format ...

, part of which later became the forerunner of the Irish Republican Army

The Irish Republican Army (IRA) is a name used by various Resistance movement, resistance organisations in Ireland throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Organisations by this name have been dominantly Catholic and dedicated to anti-imperiali ...

(IRA) – to seek to ensure the passing of Home Rule, arming themselves following the Howth gun-running

The Howth gun-running ( ) was the smuggling of 1,500 Mauser rifles to Howth harbour for the Irish Volunteers, an Irish nationalist paramilitary force, on 26 July 1914. The unloading of guns from a private yacht during daylight hours attracted a ...

.

In September 1914, just as the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

broke out, the UK Parliament finally passed the Government of Ireland Act 1914

The Government of Ireland Act 1914 ( 4 & 5 Geo. 5. c. 90), also known as the Home Rule Act, and before enactment as the Third Home Rule Bill, was an Act passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom intended to provide home rule (self-gover ...

to establish self-government for Ireland, condemned by the dissident nationalists' All-for-Ireland League

The All-for-Ireland League (AFIL) was an Irish, Munster-based political party (1909–1918). Founded by William O'Brien Member of parliament, MP, it generated a new national movement to achieve agreement between the different parties concerned o ...

party as a " partition deal". The Act was suspended for the duration of the war, expected to last only a year. In order to ensure the implementation of Home Rule after the war, nationalist leaders and the Irish Parliamentary Party

The Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP; commonly called the Irish Party or the Home Rule Party) was formed in 1874 by Isaac Butt, the leader of the Nationalist Party, replacing the Home Rule League, as official parliamentary party for Irish nati ...

under Redmond supported Ireland's participation with the British war effort and Allied cause under the Triple Entente

The Triple Entente (from French meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was built upon th ...

against the expansion of the Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,; ; , ; were one of the two main coalitions that fought in World War I (1914–1918). It consisted of the German Empire, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Bulga ...

. The UVF and a majority of the Irish Volunteers who split off to form the National Volunteers

The National Volunteers were the majority faction of the Irish Volunteers that sided with Irish Parliamentary Party leader John Redmond after the movement split over the question of the Volunteers' Ireland and World War I, role in World War I.

O ...

joined in their thousands their respective Irish regiment

The Irish military diaspora refers to the many people of either Irish birth or extraction (see Irish diaspora) who have served in overseas armed forces, military forces, regardless of rank, duration of service, or success.

Many overseas militar ...

s of the New British Army. A significant section of the Irish Volunteers

The Irish Volunteers (), also known as the Irish Volunteer Force or the Irish Volunteer Army, was a paramilitary organisation established in 1913 by nationalists and republicans in Ireland. It was ostensibly formed in response to the format ...

bitterly disagreed with the National Volunteers serving with the Irish Divisions.

The 10th (Irish) Division

The 10th (Irish) Division, was one of the first of Kitchener's New Army K1 Army Group divisions (formed from Kitchener's 'first hundred thousand' new volunteers), authorized on 21 August 1914, after the outbreak of the Great War. It included ba ...

, the 16th (Irish) Division

The 16th (Irish) Division was an infantry division of the British Army, raised for service during World War I. The division was a voluntary 'Service' formation of Lord Kitchener's New Armies, created in Ireland from the 'National Volunteers', ...

and the 36th (Ulster) Division

The 36th (Ulster) Division was an infantry division of the British Army, part of Lord Kitchener's New Army, formed in September 1914. Originally called the ''Ulster Division'', it was made up of mainly members of the Ulster Volunteers, who f ...

suffered crippling losses in the trenches on the Western Front, in Gallipoli

The Gallipoli Peninsula (; ; ) is located in the southern part of East Thrace, the European part of Turkey, with the Aegean Sea to the west and the Dardanelles strait to the east.

Gallipoli is the Italian form of the Greek name (), meaning ' ...

and the Middle East. Between 35,000 and 50,000 Irishmen (in all armies) are believed to have died in the War. Each side believed that, after the war, Great Britain would favour their respective goals of remaining fully part of the United Kingdom or becoming a self-governing United Ireland

United Ireland (), also referred to as Irish reunification or a ''New Ireland'', is the proposition that all of Ireland should be a single sovereign state. At present, the island is divided politically: the sovereign state of Ireland (legally ...

within the union with the United Kingdom. Before the war ended, Britain made two concerted efforts to implement Home Rule, one in May 1916 after the Easter Rising

The Easter Rising (), also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed insurrection in Ireland during Easter Week in April 1916. The Rising was launched by Irish republicans against British rule in Ireland with the aim of establishing an ind ...

and again during 1917–1918, but during the Irish Convention

The Irish Convention was an assembly which sat in Dublin, Ireland from July 1917 until March 1918 to address the '' Irish question'' and other constitutional problems relating to an early enactment of self-government for Ireland, to debate it ...

the Irish sides (Nationalist, Unionist) were unable to agree on terms for the temporary or permanent exclusion of Ulster

Ulster (; or ; or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional or historic provinces of Ireland, Irish provinces. It is made up of nine Counties of Ireland, counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kingdom); t ...

from its provisions. However, the combination of postponement of Home Rule and the involvement of Ireland with Great Britain in the war ("England's difficulty is Ireland's opportunity" as an old Republican saying went) provoked some on the radical fringes of Irish nationalism to resort to physical force.

Until 1918, the Irish Parliamentary Party, which sought independent self-government for the whole of Ireland through the principles of parliamentary constitutionalism, remained the dominant Irish party. But from the early 20th century, a radical fringe among Home Rulers became associated with militant republicanism, particularly Irish-American republicanism. It was from the former Irish Volunteer ranks that the Irish Republican Brotherhood

The Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB; ) was a secret oath-bound fraternal organisation dedicated to the establishment of an "independent democratic republic" in Ireland between 1858 and 1924.McGee, p. 15. Its counterpart in the United States ...

organized an armed rebellion in 1916.

Easter Rising

Because of divisions among the Volunteer leadership, only a small part of their numbers was mobilized. Indeed,Eoin MacNeill

Eoin MacNeill (; born John McNeill; 15 May 1867 – 15 October 1945) was an Irish scholar, Irish language enthusiast, Gaelic revivalist, nationalist, and politician who served as Minister for Education from 1922 to 1925, Ceann Comhairle of D ...

, the Volunteer commander, countermanded orders to units to begin the insurrection. Nevertheless, at Easter 1916, a small band of 1500 republican rebels (Volunteers and Irish Citizen Army) staged a rebellion, called the "Easter Rising

The Easter Rising (), also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed insurrection in Ireland during Easter Week in April 1916. The Rising was launched by Irish republicans against British rule in Ireland with the aim of establishing an ind ...

" in Dublin, under Padraig Pearse and James Connolly

James Connolly (; 5 June 1868 – 12 May 1916) was a Scottish people, Scottish-born Irish republicanism, Irish republican, socialist, and trade union leader, executed for his part in the Easter Rising, 1916 Easter Rising against British rule i ...

. The Rising was put down after a week's fighting. Initially, their acts were widely condemned by nationalists, who had suffered severe losses in the war as their sons fought at Gallipoli

The Gallipoli Peninsula (; ; ) is located in the southern part of East Thrace, the European part of Turkey, with the Aegean Sea to the west and the Dardanelles strait to the east.

Gallipoli is the Italian form of the Greek name (), meaning ' ...

during the Landing at Cape Helles, and on the Western Front. Major newspapers such as the ''Irish Independent

The ''Irish Independent'' is an Irish daily newspaper

A newspaper is a Periodical literature, periodical publication containing written News, information about current events and is often typed in black ink with a white or gray backgrou ...

'' and local authorities openly called for the execution of Pearse and the Rising's leadership. However, the government's handling of the aftermath, and the execution of rebels and others in stages, ultimately led to widespread public sympathy for the rebels.

The government and the Irish media wrongly blamed Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( ; ; ) is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active in both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The History of Sinn Féin, original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur Griffit ...

, then a small monarchist political party with little popular support for the rebellion, even though in reality it had not been involved. Nonetheless, Rising survivors, notably Éamon de Valera

Éamon de Valera (; ; first registered as George de Valero; changed some time before 1901 to Edward de Valera; 14 October 1882 – 29 August 1975) was an American-born Irish statesman and political leader. He served as the 3rd President of Ire ...

returning from imprisonment in Great Britain, joined the party in great numbers, radicalized its programme and took control of its leadership.

Until 1917, Sinn Féin, under its founder Arthur Griffith

Arthur Joseph Griffith (; 31 March 1871 – 12 August 1922) was an Irish writer, newspaper editor and politician who founded the political party Sinn Féin. He led the Irish delegation at the negotiations that produced the 1921 Anglo-Irish Trea ...

, had campaigned for a form of government championed first by O'Connell, namely that Ireland would become independent as a dual monarchy with Great Britain, under a shared king. Such a system operated under Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

, where the same monarch, Emperor Charles I, reigned separately in both Austria and Hungary. Indeed, Griffith in his book, '' The Resurrection of Hungary'', modeled his ideas on the manner in which Hungary had forced Austria to create a dual monarchy linking both states.