History Of Australia (1788–1850) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of Australia from 1788 to 1850 covers the early British colonial period of

Governor Phillip was vested with complete authority over the inhabitants of the colony. His intention was to establish harmonious relations with local Aboriginal people and try to reform as well as discipline the convicts of the colony. Early efforts at agriculture were fraught and supplies from overseas were scarce. Between 1788 and 1792 about 3546 male and 766 female convicts were landed at Sydney. Many new arrivals were sick or unfit for work and the condition of healthy convicts also deteriorated due to the hard labour and poor food. The food situation reached crisis point in 1790 and the Second Fleet which finally arrived in June 1790 had lost a quarter of its passengers through sickness, while the condition of the convicts of the Third Fleet appalled Phillip. From 1791, however, the more regular arrival of ships and the beginnings of trade lessened the feeling of isolation and improved supplies.

In 1788, Phillip established a subsidiary settlement on

Governor Phillip was vested with complete authority over the inhabitants of the colony. His intention was to establish harmonious relations with local Aboriginal people and try to reform as well as discipline the convicts of the colony. Early efforts at agriculture were fraught and supplies from overseas were scarce. Between 1788 and 1792 about 3546 male and 766 female convicts were landed at Sydney. Many new arrivals were sick or unfit for work and the condition of healthy convicts also deteriorated due to the hard labour and poor food. The food situation reached crisis point in 1790 and the Second Fleet which finally arrived in June 1790 had lost a quarter of its passengers through sickness, while the condition of the convicts of the Third Fleet appalled Phillip. From 1791, however, the more regular arrival of ships and the beginnings of trade lessened the feeling of isolation and improved supplies.

In 1788, Phillip established a subsidiary settlement on

The

The

In 1820, British settlement was largely confined to a 100 kilometre radius around Sydney and to the central plain of Van Diemen's Land. The settler population was 26,000 on the mainland and 6,000 in Van Diemen's Land. Following the end of the

In 1820, British settlement was largely confined to a 100 kilometre radius around Sydney and to the central plain of Van Diemen's Land. The settler population was 26,000 on the mainland and 6,000 in Van Diemen's Land. Following the end of the

Pastoralists from Van Diemen's land began squatting in the

Pastoralists from Van Diemen's land began squatting in the

In 1826, the governor of New South Wales,

In 1826, the governor of New South Wales,

The Province of South Australia was established in 1836 as a privately financed settlement based on the theory of "systematic colonisation" developed by

The Province of South Australia was established in 1836 as a privately financed settlement based on the theory of "systematic colonisation" developed by

In 1824, the

In 1824, the

By the middle of the 17th century, the discoveries of Dutch explorers allowed the almost complete mapping of Australia's northern and western coasts and much of its southern and south-eastern Tasmanian coasts''.'' In 1770, James Cook had charted most of the east coast of the continent.

In 1798–99

By the middle of the 17th century, the discoveries of Dutch explorers allowed the almost complete mapping of Australia's northern and western coasts and much of its southern and south-eastern Tasmanian coasts''.'' In 1770, James Cook had charted most of the east coast of the continent.

In 1798–99

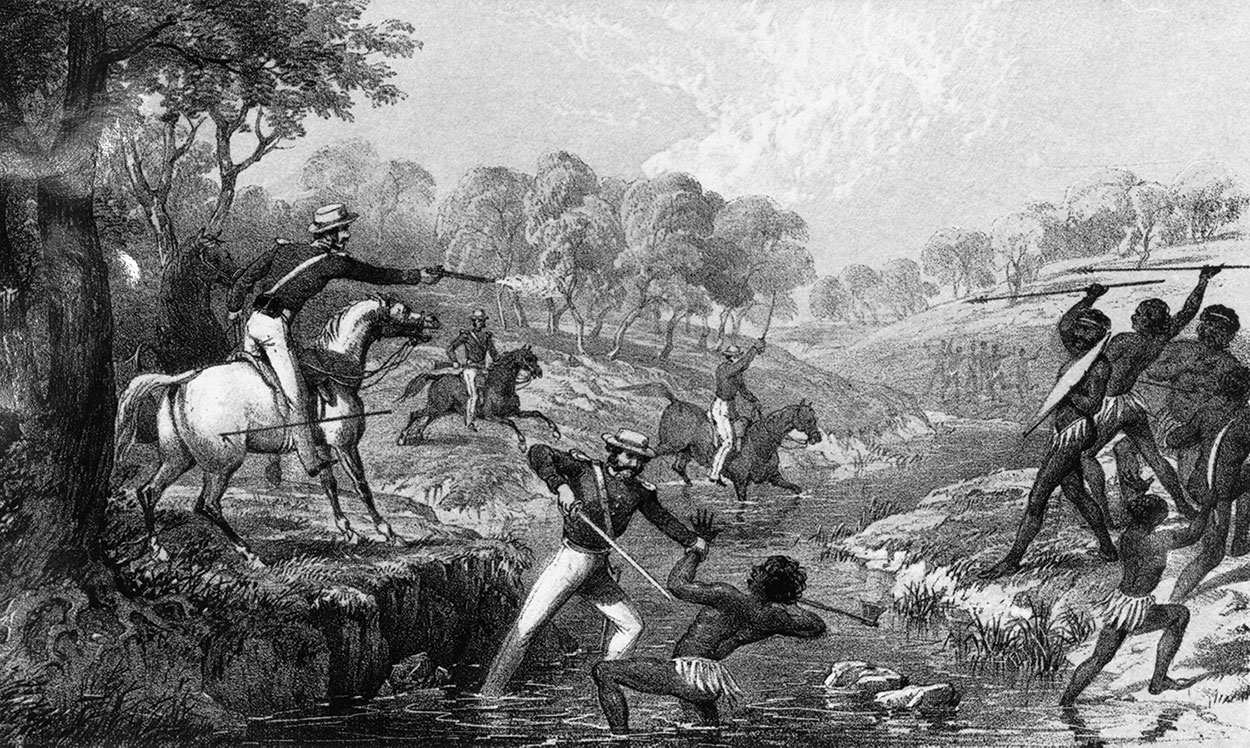

As the colony spread to the more fertile lands around the Hawkesbury river, north-west of Sydney, conflict between the settlers and the

As the colony spread to the more fertile lands around the Hawkesbury river, north-west of Sydney, conflict between the settlers and the

From 1788 until the 1850s, the governance of the colonies, including most policy decision-making, was largely in the hands of the governors, who were directly responsible to the government in London (

From 1788 until the 1850s, the governance of the colonies, including most policy decision-making, was largely in the hands of the governors, who were directly responsible to the government in London ( The

The

In 1840, the Adelaide City Council and the Sydney City Council were established. Men who possessed 1,000 pounds' worth of property were able to stand for election and wealthy landowners were permitted up to four votes each in elections.

The British government abolished transportation to New South Wales in 1840, and in 1842 granted limited representative government to the colony by establishing a reformed Legislative Council with one-third of its members appointed by the governor and two-thirds elected by male voters who met a property qualification. The property qualification meant that only 20 per cent of males were eligible to vote in the first Legislative Council elections in 1843.

The increasing immigration of free settlers, the declining number of convicts, and the growing middle class and working class population led to further agitation for liberal and democratic reforms. Public meetings in Adelaide in 1844 called for more representative government for South Australia. The Constitutional Association, formed in Sydney in 1848, called for manhood suffrage. The Anti-Transportation League, founded in Van Diemen's Land in 1849, also demanded more representative government. In the Port Phillip District, agitation for representative government was closely linked to demands for independence from New South Wales.

In 1850, the imperial parliament passed the '' Australian Colonies Government Act,'' granting Van Diemen's Land, South Australia and the newly created colony of Victoria semi-elected Legislative Councils on the New South Wales model. The Act also reduced the property requirement for voting. Government officials were to be responsible to the governor rather than the Legislative Council, so the imperial legislation provided for limited representative government rather than

In 1840, the Adelaide City Council and the Sydney City Council were established. Men who possessed 1,000 pounds' worth of property were able to stand for election and wealthy landowners were permitted up to four votes each in elections.

The British government abolished transportation to New South Wales in 1840, and in 1842 granted limited representative government to the colony by establishing a reformed Legislative Council with one-third of its members appointed by the governor and two-thirds elected by male voters who met a property qualification. The property qualification meant that only 20 per cent of males were eligible to vote in the first Legislative Council elections in 1843.

The increasing immigration of free settlers, the declining number of convicts, and the growing middle class and working class population led to further agitation for liberal and democratic reforms. Public meetings in Adelaide in 1844 called for more representative government for South Australia. The Constitutional Association, formed in Sydney in 1848, called for manhood suffrage. The Anti-Transportation League, founded in Van Diemen's Land in 1849, also demanded more representative government. In the Port Phillip District, agitation for representative government was closely linked to demands for independence from New South Wales.

In 1850, the imperial parliament passed the '' Australian Colonies Government Act,'' granting Van Diemen's Land, South Australia and the newly created colony of Victoria semi-elected Legislative Councils on the New South Wales model. The Act also reduced the property requirement for voting. Government officials were to be responsible to the governor rather than the Legislative Council, so the imperial legislation provided for limited representative government rather than

The instructions provided to the first five governors of New South Wales show that the initial plans for the colony were limited. The settlement was to be a self-sufficient penal colony based on subsistence agriculture. Trade, shipping and ship building were banned in order to keep the convicts isolated and so as not to interfere with the trade monopoly of the

The instructions provided to the first five governors of New South Wales show that the initial plans for the colony were limited. The settlement was to be a self-sufficient penal colony based on subsistence agriculture. Trade, shipping and ship building were banned in order to keep the convicts isolated and so as not to interfere with the trade monopoly of the

The colonists also transmitted their cultures orally and through song, music, art and performance, but also through writing. Governor Macquarie commissioned emancipist Michael Massey Robinson to write verse to celebrate the birthdays of

The colonists also transmitted their cultures orally and through song, music, art and performance, but also through writing. Governor Macquarie commissioned emancipist Michael Massey Robinson to write verse to celebrate the birthdays of

*Duyker, Edward & Maryse. 2001. ''Voyage to Australia and the Pacific 1791–1793''. Melbourne University Press. . *Duyker, Edward & Maryse. 2003. ''Citizen Labillardière – A Naturalist's Life in Revolution and Exploration''. The Miegunyah Press. . *Horner, Frank. 1995. ''Looking for La Pérouse''. Melbourne University Press. . *Lepailleur, François-Maurice. 1980. ''Land of a Thousand Sorrows. The Australian Prison Journal 1840–1842, of the Exiled Canadien'' Patriote, ''François-Maurice Lepailleur''. Trans. and edited by F. Murray Greenwood. University of British Columbia Press, Vancouver. . * John Holland Rose, Rose, J. Holland; Newton, A. P.; Benians, E. A. (1968), '' The Cambridge History of the British Empire'', Volume II—The Growth of the New Empire 1783–1870. Available at the

*Th

Australian History

page a

Project Gutenberg of Australia

– digitised versions of many old books {{DEFAULTSORT:History of Australia (1788-1850) History of Australia (1788–1850), 19th century in Australia

Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

's history. This started with the arrival in 1788 of the First Fleet

The First Fleet were eleven British ships which transported a group of settlers to mainland Australia, marking the beginning of the History of Australia (1788–1850), European colonisation of Australia. It consisted of two Royal Navy vessel ...

of British ships at Port Jackson

Port Jackson, commonly known as Sydney Harbour, is a natural harbour on the east coast of Australia, around which Sydney was built. It consists of the waters of Sydney Harbour, Middle Harbour, North Harbour and the Lane Cove and Parramatta ...

on the lands of the Eora, and the establishment of the penal colony of New South Wales

New South Wales (commonly abbreviated as NSW) is a States and territories of Australia, state on the Eastern states of Australia, east coast of :Australia. It borders Queensland to the north, Victoria (state), Victoria to the south, and South ...

as part of the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

. It further covers the European scientific exploration of the continent and the establishment of the other Australian colonies

The states and territories are the national subdivisions and second level of government of Australia. The states are partially sovereignty, sovereign, administrative divisions that are autonomous administrative division, self-governing polity, ...

that make up the modern states

State most commonly refers to:

* State (polity), a centralized political organization that regulates law and society within a territory

**Sovereign state, a sovereign polity in international law, commonly referred to as a country

**Nation state, a ...

of Australia.

After several years of privation, the penal colony gradually expanded and developed an economy based on farming, fishing, whaling, trade with incoming ships, and construction using convict labour. By 1820, however, British settlement was largely confined to a radius around Sydney

Sydney is the capital city of the States and territories of Australia, state of New South Wales and the List of cities in Australia by population, most populous city in Australia. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Syd ...

and to the central plain of Van Diemen's land

Van Diemen's Land was the colonial name of the island of Tasmania during the European exploration of Australia, European exploration and colonisation of Australia in the 19th century. The Aboriginal Tasmanians, Aboriginal-inhabited island wa ...

. From 1816, penal transportation

Penal transportation (or simply transportation) was the relocation of convicted criminals, or other persons regarded as undesirable, to a distant place, often a colony, for a specified term; later, specifically established penal colonies bec ...

to Australia increased rapidly and the number of free settlers grew steadily. Van Diemen's Land became a separate colony in 1825, and free settlements were established at the Swan River Colony

The Swan River Colony, also known as the Swan River Settlement, or just ''Swan River'', was a British colony established in 1829 on the Swan River, in Western Australia. This initial settlement place on the Swan River was soon named Perth, an ...

in Western Australia (1829), the Province of South Australia (1836), and in the Port Philip District (1836). The grazing of cattle and sheep expanded inland, leading to increasing conflict with Aboriginal people on their traditional lands.

The growing population of free settlers, former convicts and Australian-born currency lads and lasses led to public demands for representative government

Representative democracy, also known as indirect democracy or electoral democracy, is a type of democracy where elected delegates represent a group of people, in contrast to direct democracy. Nearly all modern Western-style democracies funct ...

. Penal transportation to New South Wales ended in 1840 and a semi-elected Legislative Council was established in 1842. In 1850, Britain granted Van Diemen's Land, South Australia and the newly created colony of Victoria semi-representative Legislative Councils.

British settlement led to a decline in the Aboriginal population and the disruption of their cultures due to introduced diseases, violent conflict and dispossession of their traditional lands. Aboriginal resistance to British encroachment on their land often led to reprisals from settlers including massacres of Aboriginal people. Many Aboriginal people, however, sought an accommodation with the settlers and established viable communities, often on small areas of their traditional lands, where many aspects of their cultures were maintained.

Colonisation

Decision to colonise New South Wales

The decision to establish a colony in Australia was made byThomas Townshend, 1st Viscount Sydney

Thomas Townshend, 1st Viscount Sydney (24 February 1733 – 30 June 1800) was a British politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1754 to 1783 when he was raised to the peerage as Baron Sydney. He held several important Cabinet posts in ...

. This was taken for two reasons: the ending of transportation of criminals to North America following the American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

, as well as the need for a base

in the Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is bounded by the cont ...

to counter French expansion. Approximately 50,000 convicts are estimated to have been transported to the colonies over 150 years. The First Fleet

The First Fleet were eleven British ships which transported a group of settlers to mainland Australia, marking the beginning of the History of Australia (1788–1850), European colonisation of Australia. It consisted of two Royal Navy vessel ...

, which established the first colony, was an unprecedented project for the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

, as well as the first forced migration of settlers to a newly established colony.

The American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

(1775–1783) saw Britain lose most of its North American colonies and consider establishing replacement territories. Britain had transported about 50,000 convicts to the New World from 1718 to 1775 and was now searching for an alternative. The temporary solution of floating prison hulks had reached capacity and was a public health hazard, while the option of building more jails and workhouses was deemed too expensive.

Sir Joseph Banks

Sir Joseph Banks, 1st Baronet, (19 June 1820) was an English Natural history, naturalist, botanist, and patron of the natural sciences.

Banks made his name on the European and American voyages of scientific exploration, 1766 natural-history ...

, the eminent scientist who had accompanied Lieutenant James Cook

Captain (Royal Navy), Captain James Cook (7 November 1728 – 14 February 1779) was a British Royal Navy officer, explorer, and cartographer famous for his three voyages of exploration to the Pacific and Southern Oceans, conducted between 176 ...

on his 1770 voyage, recommended Botany Bay

Botany Bay (Dharawal language, Dharawal: ''Kamay'') is an open oceanic embayment, located in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, south of the Sydney central business district. Its source is the confluence of the Georges River at Taren Point a ...

, then known to the local Gweagal

The Gweagal (also spelt Gwiyagal) are a clan of the Tharawal, Dharawal people of Aboriginal Australians. Their descendants are Traditional owners, traditional custodians of the southern areas of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia.

Country

The ...

people as Kamay, as a suitable site. Banks accepted an offer of assistance from the American Loyalist

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cr ...

James Matra

James Mario Matra (c. 174629 March 1806), sailor and diplomat, was a Province of New York-born midshipman on the voyage by James Cook to Botany Bay in 1770. He was the first person of Corsican heritage to visit the future nation of Australia. The ...

in July 1783. Matra had visited Botany Bay with Banks in 1770 as a junior officer on the ''Endeavour'' commanded by James Cook. Under Banks's guidance, he rapidly produced "A Proposal for Establishing a Settlement in New South Wales" (24 August 1783), with a fully developed set of reasons for a colony composed of American Loyalists, Chinese and South Sea Islanders (but not convicts).

Following an interview with Secretary of State Lord Sydney in March 1784, Matra amended his proposal to include convicts as settlers. Matra's plan can be seen to have “provided the original blueprint for settlement in New South Wales”. A cabinet memorandum December 1784 shows the Government had Matra's plan in mind when considering the creation of a settlement in New South Wales.

The major alternative to Botany Bay was sending convicts to Africa. From 1775 convicts had been sent to garrison British forts in west Africa, but the experiment had proved unsuccessful. In 1783, the Pitt government considered exiling convicts to a small river island in Gambia where they could form a self-governing community, a "colony of thieves", at no expense to the government.

In 1785, a parliamentary select committee chaired by Lord Beauchamp recommended against the Gambia plan, but failed to endorse the alternative of Botany Bay. In a second report, Beauchamp recommended a penal settlement at Das Voltas Bay in modern Namibia. The plan was dropped, however, when an investigation of the site in 1786 found it to be unsuitable. Two weeks later, in August 1786, the Pitt government announced its intention to send convicts to Botany Bay. The Government incorporated the settlement of Norfolk Island

Norfolk Island ( , ; ) is an States and territories of Australia, external territory of Australia located in the Pacific Ocean between New Zealand and New Caledonia, directly east of Australia's Evans Head, New South Wales, Evans Head and a ...

into their plan, with its attractions of timber and flax, proposed by Banks's Royal Society colleagues, Sir John Call and Sir George Young.

There has been a longstanding debate over whether the key consideration in the decision to establish a penal colony at Botany Bay was the pressing need to find a solution to the penal management problem, or whether broader imperial goals — such as trade, securing new supplies of timber and flax for the navy, and the desirability of strategic ports in the region — were paramount. Leading historians in the debate have included Sir Ernest Scott, Geoffrey Blainey

Geoffrey Norman Blainey, (born 11 March 1930) is an Australian historian, academic, best selling author and commentator.

Blainey is noted for his authoritative texts on the economic and social history of Australia, including ''The Tyranny of ...

, and Alan Frost

Alan J. Frost , (29 March 1943 – 12 April 2023) was an Australian historian and professor emeritus at La Trobe University. A major theme of his research involved the European exploration of the Pacific Ocean over the second half of the eighte ...

.

The decision to settle was taken when it seemed the outbreak of civil war in the Netherlands might precipitate a war in which Britain would be again confronted with the alliance of the three naval Powers, France, Holland and Spain, which had brought her to defeat in 1783. Under these circumstances a naval base in New South Wales which could facilitate attacks on Dutch and Spanish interests in the region would be attractive. Specific plans for using the colony as a strategic base against Spanish interests were occasionally made after 1788, but never implemented.

Macintyre argues that the evidence for a military-strategic motive in establishing the colony is largely circumstantial and hard to reconcile with the strict ban on establishing a shipyard in the colony. Karskens points out that the instructions provided to the first five governors of New South Wales show that the initial plans for the colony were limited. The settlement was to be a self-sufficient penal colony based on subsistence agriculture. Trade, shipping and ship building were banned in order to keep the convicts isolated and so as not to interfere with the trade monopoly of the British East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company that was founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to Indian Ocean trade, trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (South A ...

. There was no plan for economic development apart from investigating the possibility of producing raw materials for Britain. Christopher and Maxwell-Stewart argue that whatever the government's original motives were in establishing the colony, by the 1790s it had at least achieved the imperial objective of providing a harbour where vessels could be careened and resupplied.

Establishment of colony

On 13 May 1787, theFirst Fleet

The First Fleet were eleven British ships which transported a group of settlers to mainland Australia, marking the beginning of the History of Australia (1788–1850), European colonisation of Australia. It consisted of two Royal Navy vessel ...

of 11 ships and about 1,530 people (736 convicts, 17 convicts' children, 211 marines, 27 marines' wives, 14 marines' children and about 300 officers and others) under the command of Captain Arthur Phillip

Arthur Phillip (11 October 1738 – 31 August 1814) was a British Royal Navy officer who served as the first Governor of New South Wales, governor of the Colony of New South Wales.

Phillip was educated at Royal Hospital School, Gree ...

set sail for Botany Bay. A few days after arrival at Botany Bay

Botany Bay (Dharawal language, Dharawal: ''Kamay'') is an open oceanic embayment, located in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, south of the Sydney central business district. Its source is the confluence of the Georges River at Taren Point a ...

the fleet moved to the more suitable Port Jackson

Port Jackson, commonly known as Sydney Harbour, is a natural harbour on the east coast of Australia, around which Sydney was built. It consists of the waters of Sydney Harbour, Middle Harbour, North Harbour and the Lane Cove and Parramatta ...

where a settlement was established at Sydney Cove

Sydney Cove (Eora language, Eora: ) is a bay on the southern shore of Sydney Harbour, one of several harbours in Port Jackson, on the coast of Sydney, New South Wales. Sydney Cove is a focal point for community celebrations, due to its central ...

, known by the Indigenous name Warrane, on 26 January 1788. This date later became Australia's national day, Australia Day

Australia Day is the official national day of Australia. Observed annually on 26 January, it marks the 1788 landing of the First Fleet and raising of the Flag of Great Britain, Union Flag of Great Britain by Arthur Phillip at Sydney Cove, a ...

. The colony was formally proclaimed by Governor Phillip on 7 February 1788 at Sydney. Sydney Cove offered a fresh water supply and a safe harbour, which Philip famously described as:

Phillip named the settlement after the

Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, more commonly known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom and the head of the Home Office. The position is a Great Office of State, maki ...

, Lord Sydney. The only people at the flag raising ceremony and the formal taking of possession of the land in the name of King George III were Phillip and a few dozen marines and officers from the ''Supply'', the rest of the ship's company and the convicts witnessing it from on board ship. The remaining ships of the Fleet were unable to leave Botany Bay until later on 26 January because of a tremendous gale. The new colony was formally proclaimed as the Colony of New South Wales on 7 February.

The colony included all of Australia eastward of the meridian of 135° East. This included more than half of mainland Australia and reflected the line of division between the claims of Spain and Portugal established in the Treaty of Tordesillas

The Treaty of Tordesillas, signed in Tordesillas, Spain, on 7 June 1494, and ratified in Setúbal, Portugal, divided the newly discovered lands outside Europe between the Kingdom of Portugal and the Crown of Castile, along a meridian (geography) ...

in 1494.Robert J. King, "Terra Australis, New Holland and New South Wales: the Treaty of Tordesillas and Australia", ''The Globe'', No. 47, 1998, pp. 35–55. Watkin Tench subsequently commented in ''A Narrative of the Expedition to Botany Bay'', "By this partition, it may be fairly presumed, that every source of future litigation between the Dutch and us, will be for ever cut off, as the discoveries of English navigators only are comprized in this territory".

The claim also included "all the Islands adjacent in the Pacific" between the latitudes of Cape York and the southern tip of Van Diemen's Land

Van Diemen's Land was the colonial name of the island of Tasmania during the European exploration of Australia, European exploration and colonisation of Australia in the 19th century. The Aboriginal Tasmanians, Aboriginal-inhabited island wa ...

(Tasmania). King argues that an unofficial British map published in 1786 (''A General Chart of New Holland'') showed the possible extent of this claim. In 1817, the British government

His Majesty's Government, abbreviated to HM Government or otherwise UK Government, is the central government, central executive authority of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

withdrew the extensive territorial claim over the South Pacific, passing an act specifying that Tahiti, New Zealand and other islands of the South Pacific were not within His Majesty's dominions. However, it is unclear whether the claim ever extended to the current islands of New Zealand.

On 24 January 1788 a French expedition of two ships led by Admiral Jean-François de La Pérouse had arrived off Botany Bay, on the latest leg of a three-year voyage. Though amicably received, the French expedition was a troublesome matter for the British, as it showed the interest of France in the new land.

Nevertheless, on 2 February Lieutenant King, at Phillip's request, paid a courtesy call on the French and offered them any assistance they may need. The French made the same offer to the British, as they were much better provisioned than the British and had enough supplies to last three years. Neither of these offers was accepted. On 10 March the French expedition, having taken on water and wood, left Botany Bay, never to be seen again.

Governor Phillip was vested with complete authority over the inhabitants of the colony. His intention was to establish harmonious relations with local Aboriginal people and try to reform as well as discipline the convicts of the colony. Early efforts at agriculture were fraught and supplies from overseas were scarce. Between 1788 and 1792 about 3546 male and 766 female convicts were landed at Sydney. Many new arrivals were sick or unfit for work and the condition of healthy convicts also deteriorated due to the hard labour and poor food. The food situation reached crisis point in 1790 and the Second Fleet which finally arrived in June 1790 had lost a quarter of its passengers through sickness, while the condition of the convicts of the Third Fleet appalled Phillip. From 1791, however, the more regular arrival of ships and the beginnings of trade lessened the feeling of isolation and improved supplies.

In 1788, Phillip established a subsidiary settlement on

Governor Phillip was vested with complete authority over the inhabitants of the colony. His intention was to establish harmonious relations with local Aboriginal people and try to reform as well as discipline the convicts of the colony. Early efforts at agriculture were fraught and supplies from overseas were scarce. Between 1788 and 1792 about 3546 male and 766 female convicts were landed at Sydney. Many new arrivals were sick or unfit for work and the condition of healthy convicts also deteriorated due to the hard labour and poor food. The food situation reached crisis point in 1790 and the Second Fleet which finally arrived in June 1790 had lost a quarter of its passengers through sickness, while the condition of the convicts of the Third Fleet appalled Phillip. From 1791, however, the more regular arrival of ships and the beginnings of trade lessened the feeling of isolation and improved supplies.

In 1788, Phillip established a subsidiary settlement on Norfolk Island

Norfolk Island ( , ; ) is an States and territories of Australia, external territory of Australia located in the Pacific Ocean between New Zealand and New Caledonia, directly east of Australia's Evans Head, New South Wales, Evans Head and a ...

in the South Pacific where he hoped to obtain timber and flax for the navy. The island, however, had no safe harbour, which led the settlement to be abandoned and the settlers evacuated to Tasmania in 1807. The island was subsequently re-established as a site for secondary transportation in 1825.

Phillip sent exploratory missions in search of better soils, fixed on the Parramatta

Parramatta (; ) is a suburb (Australia), suburb and major commercial centre in Greater Western Sydney. Parramatta is located approximately west of the Sydney central business district, Sydney CBD, on the banks of the Parramatta River. It is co ...

region as a promising area for expansion, and moved many of the convicts from late 1788 to establish a small township, which became the main centre of the colony's economic life. This left Sydney Cove only as an important port and focus of social life. Poor equipment and unfamiliar soils and climate continued to hamper the expansion of farming from Farm Cove to Parramatta and Toongabbie, but a building program, assisted by convict labour, advanced steadily. Between 1788 and 1792, convicts and their gaolers made up the majority of the population; however, a free population soon began to grow, consisting of emancipated convicts, locally born children, soldiers whose military service had expired and, finally, free settlers from Britain. Governor Phillip departed the colony for England on 11 December 1792, with the new settlement having survived near starvation and immense isolation for four years.

A number of foreign commentators pointed to the strategic importance of the new colony. Spanish naval commander Alessandro Malaspina, who visited Sydney in March–April 1793 reported to his government that imperialism and trade were the real objects of the colony. Frenchman François Péron, of the Baudin expedition visited Sydney in 1802 and reported to the French Government his surprise that the Spanish had not protested at a colony strategically place to challenge Spanish interests in the region.

King points out that supporters of the penal colony frequently compared the venture to the foundation of Rome, and that the first Great Seal of New South Wales alluded to this. Phillip, however, wrote, "I would not wish Convicts to lay the foundations of an Empire...

Consolidation of colony

After the departure of Phillip, trade developed with visiting ships and farming spread to more fertile lands on the fringes of Sydney. The

The New South Wales Corps

The New South Wales Corps, later known as the 102d Regiment of Foot, and lastly as the 100th Regiment of Foot, was a formation of the British Army organised in 1789 in England to relieve the New South Wales Marine Corps, which had accompanied ...

was formed in England in 1789 as a permanent regiment of the British Army

The British Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of the United Kingdom. the British Army comprises 73,847 regular full-time personnel, 4,127 Brigade of Gurkhas, Gurkhas, 25,742 Army Reserve (United Kingdom), volunteer reserve perso ...

to relieve the marines who had accompanied the First Fleet. Officers of the Corps soon became involved in the corrupt and lucrative rum trade in the colony. Governor William Bligh

William Bligh (9 September 1754 – 7 December 1817) was a Vice-admiral (Royal Navy), Royal Navy vice-admiral and colonial administrator who served as the governor of New South Wales from 1806 to 1808. He is best known for his role in the Muti ...

(1806 1808) tried to suppress the rum trade and the illegal use of Crown Land, resulting in the Rum Rebellion

The Rum Rebellion of 1808 was a ''coup d'état'' in the British penal colony of New South Wales, staged by the New South Wales Corps in order to depose Governor William Bligh. Australia's first and only military coup, its name derives from the ...

of 1808. The Corps, working closely with the newly established wool trader John Macarthur, staged the only successful armed takeover of government in Australian history, deposing Bligh and instigating a brief period of military rule prior to the arrival from Britain of Governor Lachlan Macquarie

Major-general (United Kingdom), Major General Lachlan Macquarie, Companion of the Order of the Bath, CB (; ; 31 January 1762 – 1 July 1824) was a British Army officer and colonial administrator from Scotland. Macquarie served as the fifth Gove ...

in 1810.

Macquarie served as the last autocratic Governor of New South Wales

The governor of New South Wales is the representative of the monarch, King Charles III, in the state of New South Wales. In an analogous way to the governor-general of Australia, Governor-General of Australia at the national level, the governor ...

, from 1810 to 1821, and had a leading role in the social and economic development of New South Wales, which saw it transition from a penal colony to a budding civil society. He established a bank, a currency and a hospital, and commissioned extensive public works.

Central to Macquarie's policy was his treatment of the emancipist

An emancipist was a convict sentenced and transported under the convict system to Australia, who had been given a conditional or absolute pardon. The term was also used to refer to those convicts whose sentences had expired, and might sometimes ...

s, whom he considered should be treated as social equals to free-settlers in the colony. He appointed emancipists to key government positions including Francis Greenway

Francis Greenway (20 November 1777 - September 1837) was an English-Australian convict and colonial architect. After being convicted of forgery in England and subsequently transported to New South Wales, Australia (known then as New Holland) ...

as colonial architect and William Redfern

William Redfern (1775 – 17 July 1833) was the Surgeon’s First Mate aboard HMS ''Standard'' during the May 1797 Nore mutiny, and at a court martial in August 1797 he was sentenced to death for his involvement. His sentence was later commuted ...

as a magistrate. His policy on emancipists was opposed by many influential free settlers, officers and officials, and London became concerned at the cost of his public works. In 1819, London appointed J. T. Bigge to conduct an inquiry into the colony, and Macquarie resigned shortly before the report of the inquiry was published.

Expansion (18211850)

In 1820, British settlement was largely confined to a 100 kilometre radius around Sydney and to the central plain of Van Diemen's Land. The settler population was 26,000 on the mainland and 6,000 in Van Diemen's Land. Following the end of the

In 1820, British settlement was largely confined to a 100 kilometre radius around Sydney and to the central plain of Van Diemen's Land. The settler population was 26,000 on the mainland and 6,000 in Van Diemen's Land. Following the end of the Napoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

in 1815 the transportation of convicts increased rapidly and the number of free settlers grew steadily. From 1821 to 1840, 55,000 convicts arrived in New South Wales and 60,000 in Van Diemen's Land. However, by 1830, free settlers and the locally born exceeded the convict population of New South Wales.

From the 1820s, grazing of sheep and cattle expanded rapidly, and the colony spread beyond the official bounds of settlement. In 1825, the western boundary of New South Wales was extended to longitude 129° East, which is the current boundary of Western Australia. As a result, the territory of New South Wales reached its greatest extent, covering the area of the modern state as well as modern Queensland, Victoria, Tasmania, South Australia and the Northern Territory.

The ''Proclamation of Governor Bourke'', (10 October 1835) reinforced the doctrine that Australia had been ''terra nullius

''Terra nullius'' (, plural ''terrae nullius'') is a Latin expression meaning " nobody's land".

Since the nineteenth century it has occasionally been used in international law as a principle to justify claims that territory may be acquired ...

'' when settled by the British in 1788, and that the Crown had obtained beneficial ownership of all the land of New South Wales from that date. The proclamation stated that British subjects could not obtain title over vacant Crown land directly from Aboriginal Australians, effectively quashing the treaty between John Batman

John Batman (21 January 18016 May 1839) was an Australian Pastoral farming, grazier, entrepreneur and explorer, who had a prominent role in the foundation of Melbourne, founding of Melbourne. He also was involved in many attacks against Indigen ...

and the Aboriginal people of the Port Phillip area.

By 1850 the settler population of New South Wales had grown to 180,000, not including the 70–75 thousand living in the area which became the separate colony of Victoria in 1851.

Establishment of further colonies

Van Diemen's Land

After hosting Nicholas Baudin's French naval expedition in Sydney in 1802, Governor Phillip Gidley King decided to establish a settlement inVan Diemen's Land

Van Diemen's Land was the colonial name of the island of Tasmania during the European exploration of Australia, European exploration and colonisation of Australia in the 19th century. The Aboriginal Tasmanians, Aboriginal-inhabited island wa ...

(modern Tasmania

Tasmania (; palawa kani: ''Lutruwita'') is an island States and territories of Australia, state of Australia. It is located to the south of the Mainland Australia, Australian mainland, and is separated from it by the Bass Strait. The sta ...

) in 1803, partly to forestall a possible French settlement. The British settlement of the island soon centred on Launceston in the north and Hobart in the south. For the first two decades the settlement relied heavily on convict labour, small-scale farming and sheep grazing, sealing, whaling and the "dog and kangaroo" economy where emancipists and escaped convicts hunted native game with guns and dogs.

From the 1820s free settlers were encouraged by the offer of land grants in proportion to the capital the settlers would bring. Almost 2 million acres of land was granted to free settlers in the decade, and the number of sheep in the island increased from 170,000 to a million. The land grants created a social division between large landowners and a majority of landless convicts and emancipists.

Van Diemen's Land became a separate colony from New South Wales in December 1825 and continued to expand through the 1830s, supported by farming, sheep grazing and whaling. Following the suspension of convict transportation to New South Wales in 1840, Van Diemen's land became the main destination for convicts. Transportation to Van Diemen's Land ended in 1853 and in 1856 the colony officially changed its name to Tasmania.

Victoria

Pastoralists from Van Diemen's land began squatting in the

Pastoralists from Van Diemen's land began squatting in the Port Phillip

Port Phillip (Kulin languages, Kulin: ''Narm-Narm'') or Port Phillip Bay is a horsehead-shaped bay#Types, enclosed bay on the central coast of southern Victoria (Australia), Victoria, Australia. The bay opens into the Bass Strait via a short, ...

hinterland on the mainland in 1834, attracted by its rich grasslands. In 1835, John Batman

John Batman (21 January 18016 May 1839) was an Australian Pastoral farming, grazier, entrepreneur and explorer, who had a prominent role in the foundation of Melbourne, founding of Melbourne. He also was involved in many attacks against Indigen ...

and others negotiated the transfer of 100,000 acres of land from the Kulin people. However, the treaty was annulled the same year when the British Colonial Office

The Colonial Office was a government department of the Kingdom of Great Britain and later of the United Kingdom, first created in 1768 from the Southern Department to deal with colonial affairs in North America (particularly the Thirteen Colo ...

issued the ''Proclamation of Governor Bourke'' stating that all unalienated land in the colony was vacant Crown Land, irrespective of whether it was occupied by traditional landowners. Its publication meant that from then, all people found occupying land without the authority of the government would be considered illegal trespassers.

In 1836, Port Phillip was officially recognised as a district of New South Wales and opened for settlement. The main settlement of Melbourne was established in 1837 as a planned town on the instructions of Governor Bourke. Squatters and settlers from Van Diemen's Land and New South Wales soon arrived in large numbers, and by 1850 the district had a population of 75,000 Europeans, 2,000 Indigenous inhabitants and 5 million sheep. In 1851, the Port Phillip District separated from New South Wales as the colony of Victoria.

Western Australia

In 1826, the governor of New South Wales,

In 1826, the governor of New South Wales, Ralph Darling

General Sir Ralph Darling, GCH (1772 – 2 April 1858) was a British Army officer who served as Governor of New South Wales from 1825 to 1831. His period of governorship was unpopular, with Darling being broadly regarded as a tyrant. He introd ...

, sent a military garrison to King George Sound

King George Sound (Mineng ) is a sound (geography), sound on the south coast of Western Australia. Named King George the Third's Sound in 1791, it was referred to as King George's Sound from 1805. The name "King George Sound" gradually came in ...

(the basis of the later town of Albany), to deter the French from establishing a settlement in Western Australia. In 1827, the head of the expedition, Major Edmund Lockyer, formally annexed the western third of the continent as a British colony.

In 1829, the Swan River colony was established at the sites of modern Fremantle

Fremantle () () is a port city in Western Australia located at the mouth of the Swan River (Western Australia), Swan River in the metropolitan area of Perth, the state capital. Fremantle Harbour serves as the port of Perth. The Western Australi ...

and Perth

Perth () is the list of Australian capital cities, capital city of Western Australia. It is the list of cities in Australia by population, fourth-most-populous city in Australia, with a population of over 2.3 million within Greater Perth . The ...

, becoming the first convict-free and privatised colony in Australia. However, much of the arable land was allocated to absentee owners and the development of the colony was hampered by poor soil, the dry climate, and a lack of capital and labour. By 1850 there were a little more than 5,000 settlers, half of them children. The colony accepted convicts from that year because of the acute shortage of labour.

South Australia

The Province of South Australia was established in 1836 as a privately financed settlement based on the theory of "systematic colonisation" developed by

The Province of South Australia was established in 1836 as a privately financed settlement based on the theory of "systematic colonisation" developed by Edward Gibbon Wakefield

Edward Gibbon Wakefield (20 March 179616 May 1862) was an English politician in colonial Canada and New Zealand. He is considered a key figure in the establishment of the colonies of South Australia and New Zealand (where he later served as a ...

. The intention was to found a free colony based on private investment at little cost to the British government. Power was divided between the Crown and a Board of Commissioners of Colonisation, responsible to about 300 shareholders. Settlement was to be controlled to promote a balance between land, capital and labour. Convict labour was banned in the hope of making the colony more attractive to "respectable" families and promote an even balance between male and female settlers. The city of Adelaide

Adelaide ( , ; ) is the list of Australian capital cities, capital and most populous city of South Australia, as well as the list of cities in Australia by population, fifth-most populous city in Australia. The name "Adelaide" may refer to ei ...

was to be planned with a generous provision of churches, parks and schools. Land was to be sold at a uniform price and the proceeds used to secure an adequate supply of labour through selective assisted migration.Ford, Lisa; Roberts, David Andrew (2013). pp. 139–40 Various religious, personal and commercial freedoms were guaranteed, and the Letters Patent

Letters patent (plurale tantum, plural form for singular and plural) are a type of legal instrument in the form of a published written order issued by a monarch, President (government title), president or other head of state, generally granti ...

enabling the South Australia Act 1834

The South Australia Act 1834 ( 4 & 5 Will. 4. c. 95), or Foundation Act 1834 and also known as the South Australian Colonization Act, was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which provided for the settlement of a province or multipl ...

included a guarantee of the rights of "any Aboriginal Natives" and their descendants to lands they "now actually occupied or enjoyed".

The colony was badly hit by the depression of 1841–44, and overproduction of wheat and overinvestment in infrastructure almost bankrupted it. Conflict with Indigenous traditional landowners also reduced the protections they had been promised. In 1842, the settlement became a Crown colony administered by the governor and an appointed Legislative Council. The economy recovered from 1845, supported by wheat farming, sheep grazing and a boom in copper mining. By 1850 the settler population had grown to 60,000 and the following year the colony achieved limited self-government with a partially elected Legislative Council.

Queensland

In 1824, the

In 1824, the Moreton Bay penal settlement

The Moreton Bay Penal Settlement operated from 1825 to 1842. It became the city of Brisbane, Queensland, Australia.

History

The Moreton Bay Penal Settlement was established on the Redcliffe Peninsula on Moreton Bay in September 1824, under t ...

was established on the site of present-day Brisbane

Brisbane ( ; ) is the List of Australian capital cities, capital and largest city of the States and territories of Australia, state of Queensland and the list of cities in Australia by population, third-most populous city in Australia, with a ...

as a place of secondary punishment. In 1842, the penal colony was closed and the area was opened for free settlement. By 1850 the population of Brisbane had reached 8,000 and increasing numbers of pastoralists were grazing cattle and sheep in the Darling Downs west of the town. However, several attempts to establish settlements north of the Tropic of Capricorn had failed, and the settler population in the north remained small. Frontier violence between settlers and the Indigenous population became severe as pastoralism expanded north of the Tweed River. A series of disputes between northern pastoralists and the government in Sydney led to increasing demands from the northern settlers for separation from New South Wales. In 1857, the British government agreed to the separation and in 1859 the colony of Queensland was proclaimed. The settler population of the new colony was 25,000 and the vast majority of its territory was still occupied by its traditional owners

Native title is the set of rights, recognised by Australian law, held by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups or individuals to land that derive from their maintenance of their traditional laws and customs. These Aboriginal title rig ...

.

Convict society

Between 1788 and 1868, approximately 161,700 convicts (of whom 25,000 were women) were transported to the Australian colonies of New South Wales, Van Diemen's Land and Western Australia. Historian Lloyd Robson has estimated that perhaps two-thirds were thieves from working class towns, particularly fromthe Midlands

The Midlands is the central region of England, to the south of Northern England, to the north of southern England, to the east of Wales, and to the west of the North Sea. The Midlands comprises the ceremonial counties of Derbyshire, Herefords ...

and north of England. The majority were repeat offenders. The literacy rate of convicts was above average and they brought a range of useful skills to the new colony including building, farming, sailing, fishing and hunting. The small number of free settlers meant that early governors also had to rely on convicts and emancipists for professions such as lawyers, architects, surveyors and teachers.

The first governors saw New South Wales as a place of punishment and reform of convicts. Convicts worked on government farms and public works such as land clearing and building. After 1792 the majority were assigned to work for private employers including emancipists (as transported convicts who had completed their sentence or had been pardoned called themselves). Emancipists were granted small plots of land for farming and a year of government rations. Later they were assigned convict labour to help them work their farms. Some convicts were assigned to military officers to run their businesses because the officers did not want to be directly associated with trade. These convicts learnt commercial skills which could help them work for themselves when their sentence ended or they were granted a "ticket of leave" (a form of parole). Female convicts were usually assigned as domestic servants to the free settlers, many being forced into prostitution.

Convicts soon established a system of piece work which allowed them to work for wages once their allocated tasks were completed. Due to the shortage of labour, wage rates before 1815 were high for male workers although much lower for females engaged in domestic work. In 1814, Governor Macquarie ordered that convicts had to work until 3pm, after which private employers had to pay them wages for any additional work.

By 1821 convicts, emancipists and their children owned two-thirds of the land under cultivation, half the cattle and one-third of the sheep. They also worked in trades and small business. Emancipists employed about half of the convicts assigned to private masters.

After 1815 wages and employment opportunities for convicts and emancipists deteriorated as a sharp increase in the number of convicts transported led to an oversupply of labour. A series of reforms recommended by J. T. Bigge in 1822 and 1823 also sought to change the nature of the colony and make transportation "an object of real terror". The food ration for convicts was cut and their opportunities to work for wages restricted. More convicts were assigned to rural work gangs, bureaucratic control and surveillance of convicts was made more systematic, isolated penal settlements were established as places of secondary punishment, the rules for tickets of leave were tightened, and land grants were skewed to favour free settlers with large capital. As a result, convicts who arrived after 1820 were far less likely to become property owners, to marry, and to establish families.

Growth of free settlement

The Bigge reforms also aimed to encourage affluent free settlers by offering them land grants for farming and grazing in proportion to their capital. From 1831 the colonies replaced land grants with land sales by auction at a fixed minimum price per acre, the proceeds being used to fund the assisted migration of workers. From 1821 to 1850 Australia attracted 200,000 immigrants from the United Kingdom. Although most immigrants settled in towns, many were attracted to the high wages and business opportunities available in rural areas. However, the system of land grants, and later land sales, led to the concentration of land in the hands of a small number of affluent settlers. Two-thirds of the migrants to Australia during this period received assistance from the British or colonial governments. Healthy young workers without dependants were favoured for assisted migration, especially those with experience as agricultural labourers or domestic workers. Families of convicts were also offered free passage and about 3,500 migrants were selected under theEnglish Poor Laws

The English Poor Laws were a system of poor relief in England and Wales that developed out of the codification of late-medieval and Tudor-era laws in 1587–1598. The system continued until the modern welfare state emerged in the late 1940s.

En ...

. Various special-purpose and charitable schemes, such as those of Caroline Chisholm

Caroline Chisholm ( ; born Caroline Jones; 30 May 1808 – 25 March 1877) was an English humanitarian known mostly for her support of immigrant female and family welfare in Australia. She is commemorated on 16 May in the Calendar of saints (Ch ...

and John Dunmore Lang

John Dunmore Lang (25 August 1799 – 8 August 1878) was a Scottish-born Australian Presbyterian minister, writer, historian, politician and activist. He was the first prominent advocate of an independent Australian nation and of Australian rep ...

, also provided migration assistance.

Women

Colonial Australia was characterised by an imbalance of the sexes as women comprised only about 15 per cent of convicts transported. The first female convicts brought a range of skills including experience as domestic workers, dairy women and farm workers. Due to the shortage of women in the colony they were more likely to marry than men and tended to choose older, skilled men with property as husbands. The early colonial courts enforced the property rights of women independently of their husbands, and the ration system also gave women and their children some protection from abandonment. Women were active in business and agriculture from the early years of the colony, among the most successful being the former convict turned entrepreneur Mary Reibey and the agriculturalist Elizabeth Macarthur. One-third of the shareholders of the first colonial bank (founded in 1817) were women. One of the goals of the assisted migration programs from the 1830s was to promote migration of women and families to provide a more even gender balance in the colonies. The philanthropist Caroline Chisholm established a shelter and labour exchange for migrant women in New South Wales in the 1840s and promoted the settlement of single and married women in rural areas where she hoped they would have a civilising influence on rough colonial manners and act as "God's police". Between 1830 and 1850 the female proportion of the Australian settler population increased from 24 per cent to 41 per cent.European exploration

By the middle of the 17th century, the discoveries of Dutch explorers allowed the almost complete mapping of Australia's northern and western coasts and much of its southern and south-eastern Tasmanian coasts''.'' In 1770, James Cook had charted most of the east coast of the continent.

In 1798–99

By the middle of the 17th century, the discoveries of Dutch explorers allowed the almost complete mapping of Australia's northern and western coasts and much of its southern and south-eastern Tasmanian coasts''.'' In 1770, James Cook had charted most of the east coast of the continent.

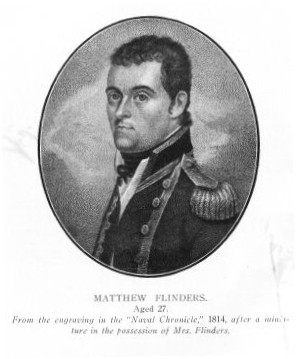

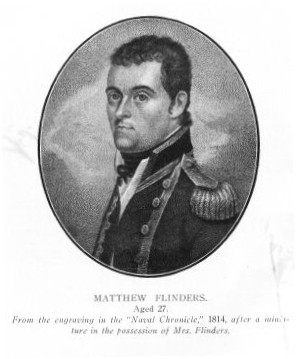

In 1798–99 George Bass

George Bass (; 30 January 1771 – after 5 February 1803) was a British naval surgeon and explorer of Australia.

Early life

Bass was born on 30 January 1771 at Aswarby, a hamlet near Sleaford, Lincolnshire, the son of a tenant farmer, George B ...

and Matthew Flinders

Captain (Royal Navy), Captain Matthew Flinders (16 March 1774 – 19 July 1814) was a British Royal Navy officer, navigator and cartographer who led the first littoral zone, inshore circumnavigate, circumnavigation of mainland Australia, then ...

set out from Sydney in a sloop and circumnavigated Tasmania

Tasmania (; palawa kani: ''Lutruwita'') is an island States and territories of Australia, state of Australia. It is located to the south of the Mainland Australia, Australian mainland, and is separated from it by the Bass Strait. The sta ...

, thus proving it to be an island. In 1801–02 Flinders, in , led the first circumnavigation of Australia. Aboard ship was the Aboriginal explorer Bungaree, who became the first person born on the Australian continent to circumnavigate it.

In 1798, the former convict John Wilson and two companions crossed the Blue Mountains, west of Sydney, in an expedition ordered by Governor Hunter. Hunter suppressed news of the feat for fear that it would encourage convicts to abscond from the settlement. In 1813, Gregory Blaxland

Gregory Blaxland (17 June 1778 – 1 January 1853) was an English pioneer farmer and explorer in Australia, noted especially for initiating and co-leading the first successful crossing of the Blue Mountains by European settlers.

Early life ...

, William Lawson and William Wentworth

William Charles Wentworth (August 179020 March 1872) was an Australian statesman, pastoralist, explorer, newspaper editor, lawyer, politician and author, who became one of the wealthiest and most powerful figures in colonial New South Wales. He ...

crossed the mountains by a different route and a road was soon built to the Central Tablelands

The Central Tablelands in New South Wales is a geographic area that lies between the Sydney Metropolitan Area and the Central Western Slopes and Plains. The Great Dividing Range passes in a north–south direction through the Central Tablelands ...

.

In 1824 the Governor Sir Thomas Brisbane

Major-general (United Kingdom), Major General Sir Thomas MacDougall Brisbane, 1st Baronet, (23 July 1773 – 27 January 1860), was a British Army officer, administrator, and astronomer. Upon the recommendation of the Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke ...

, commissioned Hamilton Hume

Hamilton Hume (19 June 1797 – 19 April 1873) was an early explorer of the present-day Australian states of New South Wales and Victoria (Australia), Victoria. In 1824, along with William Hovell, Hume participated in an expedition that first t ...

and former Royal Navy Captain William Hovell to lead an expedition to find new grazing land in the south of the colony, and also to find an answer to the mystery of where New South Wales's western rivers flowed. Over 16 weeks in 1824–25, Hume and Hovell journeyed to the bay Naarm on the land of the Kulin nation

The Kulin nation is an alliance of five Aboriginal nations in the south of Australia - up into the Great Dividing Range and the Loddon and Goulburn River valleys - which shares Culture and Language.

History

Before British colonisation, the ...

, later named Port Phillip, and back. They found many important sites including the Murray River

The Murray River (in South Australia: River Murray; Ngarrindjeri language, Ngarrindjeri: ''Millewa'', Yorta Yorta language, Yorta Yorta: ''Dhungala'' or ''Tongala'') is a river in Southeastern Australia. It is List of rivers of Australia, Aust ...

(which they named the Hume), many of its tributaries, and good agricultural and grazing lands between Gunning, New South Wales and Corio Bay, Victoria.

Charles Sturt

Charles Napier Sturt (28 April 1795 – 16 June 1869) was a British officer and explorer of Australia, and part of the European land exploration of Australia, European exploration of Australia. He led several expeditions into the interior of the ...

led an expedition along the Macquarie River

The Macquarie River or Wambuul is part of the Macquarie–Barwon River (New South Wales), Barwon catchment within the Murray–Darling basin, is one of the main inland rivers in New South Wales, Australia.

The river rises in the central highl ...

in 1828 and found the Darling River

The Darling River (or River Darling; Paakantyi: ''Baaka'' or ''Barka''), is the third-longest river in Australia, measuring from its source in northern New South Wales to its confluence with the Murray River at Wentworth. Including its long ...

. A theory had developed that the inland rivers of New South Wales were draining into an inland sea. Leading a second expedition in 1829, Sturt followed the Murrumbidgee River

The Murrumbidgee River () is a major tributary of the Murray River within the Murray–Darling basin and the second longest river in Australia. It flows through the Australian state of New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory, desce ...

into a 'broad and noble river', the Murray River, which he named after Sir George Murray, secretary of state for the colonies. His party then followed this river to its junction with the Darling River

The Darling River (or River Darling; Paakantyi: ''Baaka'' or ''Barka''), is the third-longest river in Australia, measuring from its source in northern New South Wales to its confluence with the Murray River at Wentworth. Including its long ...

, facing two threatening encounters with local Aboriginal people along the way. Sturt continued downriver on to Lake Alexandrina, where the Murray meets the sea in South Australia. Suffering greatly, the party had to then row back upstream hundreds of kilometres for the return journey.

Surveyor General Sir Thomas Mitchell conducted a series of expeditions from the 1830s to "fill in the gaps" left by these previous expeditions. He was meticulous in seeking to record the original Aboriginal place names around the colony, for which reason the majority of place names to this day retain their Aboriginal titles.

The Polish scientist and explorer Count Paul Edmund Strzelecki conducted surveying work in the Australian Alps

The Australian Alps are a mountain range in southeast Australia. The range comprises an Interim Biogeographic Regionalisation for Australia, interim Australian bioregion,

in 1839 and became the first European to ascend Australia's highest peak which he named Mount Kosciuszko

Mount Kosciuszko ( ; ; Ngarigo: ) is the highest mountain of the mainland Australia, at above sea level. It is located on the Main Range of the Snowy Mountains in Kosciuszko National Park, a part of the Australian Alps National Parks and ...

in honour of the Polish patriot Tadeusz Kosciuszko.

European explorers penetrated deeper into the interior in the 1840s in a quest to discover new lands for agriculture or answer scientific enquiries. The German scientist Ludwig Leichhardt

Friedrich Wilhelm Ludwig Leichhardt (; 23 October 1813 – ), known as Ludwig Leichhardt, was a German explorer and naturalist, most famous for his exploration of northern and central Australia.Ken Eastwood,'Cold case: Leichhardt's disappearanc ...

led three expeditions in northern Australia in this decade, sometimes with the help of Aboriginal guides, identifying the grazing potential of the region and making important discoveries in the fields of botany and geology. He and his party disappeared in 1848 while attempting to cross the continent from east to west. Edmund Kennedy led an expedition into what is now far-western Queensland in 1847 before being speared by Aborigines in the Cape York Peninsula in 1848.

Aboriginal resistance and accommodation

Impact of introduced diseases

The relative isolation of the Indigenous population for some 60,000 years meant that they had little resistance to many introduced diseases. An outbreak of smallpox in April 1789 killed about half the Aboriginal population of the Sydney region while only one death was recorded among the settlers. The source of the outbreak is controversial; some researchers contend that it originated from contact with Indonesian fisherman in the far north and spread along Aboriginal trade routes while others argue that it is more likely to have been inadvertently or deliberately spread by settlers. There were further smallpox outbreaks devastating Aboriginal populations from the late 1820s (affecting south-eastern Australia), in the early 1860s (travelling inland from the Coburg Peninsula in the north to the Great Australian Bight in the south), and in the late 1860s (from the Kimberley to Geraldton). According to Josphine Flood, the estimated Aboriginal mortality rate from smallpox was 60 per cent on first exposure, 50 per cent in the tropics, and 25 per cent in the arid interior. Other introduced diseases such as measles, influenza, typhoid and tuberculosis also resulted in high death rates in Aboriginal communities. Butlin estimates that the Aboriginal population in the area of modern Victoria was around 50,000 in 1788 before two smallpox outbreaks reduced it to about 12,500 in 1830. Between 1835 (the settlement of Port Phillip) and 1853, the Aboriginal population of Victoria fell from 10,000 to around 2,000. It is estimated that about 60 per cent of these deaths were from introduced diseases, 18 per cent from natural causes and 15 per cent from settler violence. Venereal diseases were also a factor in Indigenous depopulation, reducing Aboriginal fertility rates in south-eastern Australia by an estimated 40 per cent by 1855. By 1890 up to 50 per cent of the Aboriginal population in some regions of Queensland were affected.Frontier violence

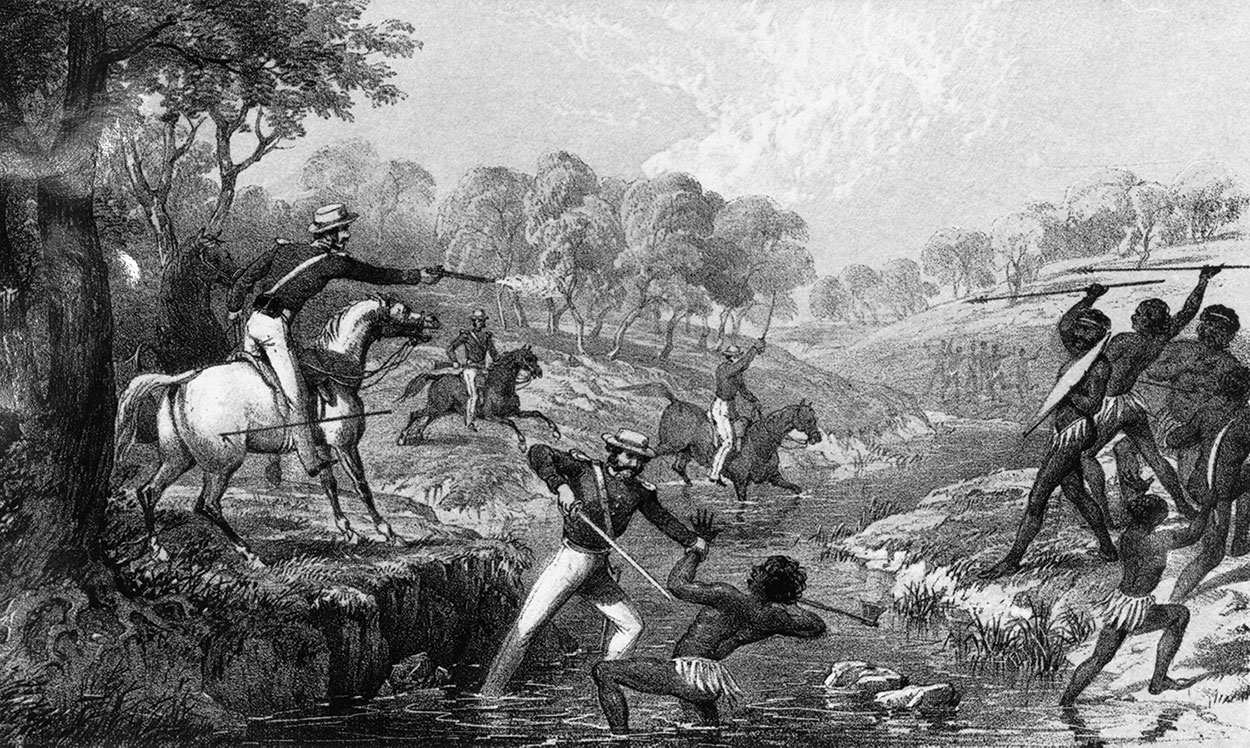

Aboriginal reactions to the arrival of British settlers were varied, but often hostile when the presence of the colonists led to competition over resources, and to the occupation of Aboriginal lands. By contrast with New Zealand, no valid treaty was signed with any of Aboriginal peoples in Australia. Flood, however, points out that unlike New Zealand, Australia's Indigenous population was divided into hundreds of tribes and language groups, which did not have "chiefs" with whom treaties could be negotiated. Moreover, Aboriginal Australians had no concept of alienating their traditional land in return for political or economic benefits. The British settlement was initially planned to be a self-sufficient penal colony based on agriculture. Karskens argues that conflict broke out between the settlers and the traditional owners of the land because of the settlers' assumptions about the superiority of British civilisation and their entitlement to land which they had "improved" through building and cultivation. Conflict also arose from cross-cultural misunderstandings and from reprisals for previous actions such as the kidnapping of Aboriginal men, women and children. Reprisal attacks and collective punishments were perpetrated by colonists and Aboriginal groups alike. Sustained Aboriginal attacks on settlers, the burning of crops and the mass killing of livestock were more obviously acts of resistance to the loss of traditional land and food resources. As the colony spread to the more fertile lands around the Hawkesbury river, north-west of Sydney, conflict between the settlers and the

As the colony spread to the more fertile lands around the Hawkesbury river, north-west of Sydney, conflict between the settlers and the Darug

The Dharug or Darug people, are a nation of Aboriginal Australian clans, who share ties of kinship, country and culture. In pre-colonial times, they lived as hunters in the region of current day Sydney. The Darug speak one of two dialects o ...

people intensified, reaching a peak from 1794 to 1810. Bands of Darug people, led by Pemulwuy

Pemulwuy ( /pɛməlwɔɪ/ ''PEM-əl-woy''; 1750 – 2 June 1802) was a Bidjigal warrior of the Dharug, an Aboriginal Australian people from New South Wales. One of the most famous Aboriginal resistance fighters in the colonial era, he is n ...

and later by his son Tedbury, burned crops, killed livestock and raided settler huts and stores in a pattern of resistance that was to be repeated as the colonial frontier expanded. A military garrison was established on the Hawkesbury in 1795. The death toll from 1794 to 1800 was 26 settlers and up to 200 Darug.

Conflict again erupted from 1814 to 1816 with the expansion of the colony into Dharawal country in the Nepean region south-west of Sydney. Following the deaths of several settlers, Governor Macquarie despatched three military detachments into Dharawal lands, culminating in the Appin massacre

The Appin Massacre was the mass murder of Aboriginal Australians, Aboriginal men, women and children in the New South Wales settlement of Appin, New South Wales, Appin, South Western Sydney, on 17 April 1816 by members of the 46th (South Devonshir ...

(April 1816) in which at least 14 Aboriginal people were killed.

In the 1820s the colony spread to the lightly wooded pastures west of the Great Dividing Range

The Great Dividing Range, also known as the East Australian Cordillera or the Eastern Highlands, is a cordillera system in eastern Australia consisting of an expansive collection of mountain ranges, plateaus and rolling hills. It runs roughl ...

, opening the way for large scale farming and grazing in Wiradjuri

The Wiradjuri people (; ) are a group of Aboriginal Australian people from central New South Wales, united by common descent through kinship and shared traditions. They survived as skilled hunter-fisher-gatherers, in family groups or clans, a ...

country. From 1822 to 1824 Windradyne

Windradyne ( 1800 – 21 March 1829) was an Aboriginal warrior and resistance leader of the Wiradjuri nation, in what is now central-western New South Wales, Australia; he was also known to the British settlers as Saturday. Windradyne led his ...

led a group of 50-100 Aboriginal men in raids on livestock and stockmen's huts resulting in the death of 15-20 colonists. Martial law was declared in August 1824 and ended five months later when Windradyne and 260 of his followers ended their armed resistance. Estimates of Aboriginal deaths in the conflict range from 15 to 100.

After two decades of sporadic violence between settlers and Aboriginal Tasmanians in Van Diemen's land, the Black War

The Black War was a period of violent conflict between British colonists and Aboriginal Tasmanians in Tasmania from the mid-1820s to 1832 that precipitated the near-extermination of the indigenous population. The conflict was fought largely as ...

broke out in 1824, following a rapid expansion of settler numbers and sheep grazing in the island's interior. When Eumarrah, leader of the North Midlands people, was captured in 1828 he said his patriotic duty was to kill as many white people as possible because they had driven his people off their kangaroo hunting grounds. Martial law was declared in the settled districts of Van Diemen's Land in November 1828 and was extended to the entire island in October 1830. A "Black Line" of around 2,200 troops and settlers then swept the island with the intention of driving the Aboriginal population from the settled districts. From 1830 to 1834 George Augustus Robinson

George Augustus Robinson (22 March 1791 – 18 October 1866) was an English born builder and self-trained preacher who was employed by the British colonial authorities to conciliate the Indigenous Australians of Van Diemen's Land and the Po ...

and Aboriginal ambassadors including Truganini led a series of "Friendly Missions" to the Aboriginal tribes which effectively ended the Black War. Flood states that around 200 settler and 330 Aboriginal Tasmanian deaths in frontier violence were recorded during the period 1803 to 1834, but adds that it will never be known how many Aboriginal deaths went unreported. Clements estimates that colonists killed 600 Aboriginal people in eastern Van Diemen's Land during the Black War. Around 220 Aboriginal Tasmanians were eventually relocated to Flinders Island.

As settlers and pastoralists spread into the region of modern Victoria in the 1830s, competition for land and natural resources again sparked conflict with traditional landowners. Aboriginal resistance was so intense that it was not unusual for sheep runs to be abandoned after repeated attacks. Broome estimates that 80 settlers and 1,000–1,500 Aboriginal people died in frontier conflict in Victoria from 1835 to 1853.

The growth of the Swan River Colony (centred on Fremantle and Perth) in the 1830s led to conflict with a number of clans of the Noongar people. Governor Sterling established a mounted police force in 1834 and in October that year he led a mixed force of soldiers, mounted police and civilians in a punitive expedition against the Pindjarup. The expedition culminated in the Pinjarra massacre in which some 15 to 30 Aboriginal people were killed. According to Neville Green, 30 settlers and 121 Aboriginal people died in violent conflict in Western Australia between 1826 and 1852.

Aboriginal casualty rates in conflicts increased as the colonists made greater use of mounted police, Native Police

Australian native police were specialised mounted military units consisting of detachments of Aboriginal Australians, Aboriginal troopers under the command of European officers appointed by British colonial governments. The units existed in va ...

units, and newly developed revolvers and breech-loaded guns. Civilian colonists often launched punitive raids against Aboriginal groups without the knowledge of colonial authorities. Conflict was particularly intense in NSW in the 1840s.

The spread of British settlement also led to an increase in inter-tribal Aboriginal conflict as more people were forced off their traditional lands into the territory of other, often hostile, tribes. Butlin estimated that of the 8,000 Aboriginal deaths in Victoria from 1835 to 1855, 200 were from inter-tribal violence.

Accommodation and protection