His Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Privy Council, formally His Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council, is a formal body of advisers to the sovereign of the United Kingdom. Its members, known as privy counsellors, are mainly senior politicians who are current or former members of either the

What's the Point of ... The Privy Council

, 12 May 2009 In the 1960s, the Privy Council made an order to evict an estimated 1,200 to 2,000 inhabitants of the 55-island Chagos Archipelago in the Indian Ocean, in preparation for the establishment of a joint United States–United Kingdom military base on the largest island in the archipelago, Diego Garcia. In 2000, the

Court victory for Chagos families

, 11 May 2006 and the Court of Appeal were persuaded by this argument, but in 2007 the Law Lords of the Appellate Committee of the House of Lords found the original decision to be flawed and overturned the ruling by a 3–2 decision, thereby upholding the terms of the Order in Council. As of 2023, negotiations between the Mauritian and UK governments that included the sovereignty of the Chagossians were still ongoing.

The Privy Council have the following committees:

The Privy Council have the following committees:

The Sovereign, when acting on the Council's advice, is known as the '' King-in-Council'' or '' Queen-in-Council'', depending on the sex of the reigning monarch. The members of the Council are collectively known as ''The Lords of His Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council'' (sometimes ''The Lords and others of ...''). The chief officer of the body is the Lord President of the Council, who is the fourth-highest

The Sovereign, when acting on the Council's advice, is known as the '' King-in-Council'' or '' Queen-in-Council'', depending on the sex of the reigning monarch. The members of the Council are collectively known as ''The Lords of His Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council'' (sometimes ''The Lords and others of ...''). The chief officer of the body is the Lord President of the Council, who is the fourth-highest

Privy Council Office homepage

Judicial Committee of the Privy Council homepage

BBC: Do we need the Privy Council?BBC Radio 4: Whats the point of the Privy Council?

BBC: Privy Council: Guide to its origins, powers and members

8 October 2015 *

Guardian Comment – Roy Hattersley on the Privy Council

{{authority control History of the Commonwealth of Nations 1708 establishments in Great Britain

House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

or the House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the lower house, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England. One of the oldest ext ...

.

The Privy Council formally advises the sovereign on the exercise of the royal prerogative

The royal prerogative is a body of customary authority, Privilege (law), privilege, and immunity recognised in common law (and sometimes in Civil law (legal system), civil law jurisdictions possessing a monarchy) as belonging to the monarch, so ...

. The King-in-Council issues executive instruments known as Orders in Council. The Privy Council also holds the delegated authority to issue Orders of Council, mostly used to regulate certain public institutions. It advises the sovereign on the issuing of royal charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, but ...

s, which are used to grant special status to incorporated bodies, and city

A city is a human settlement of a substantial size. The term "city" has different meanings around the world and in some places the settlement can be very small. Even where the term is limited to larger settlements, there is no universally agree ...

or borough

A borough is an administrative division in various English language, English-speaking countries. In principle, the term ''borough'' designates a self-governing walled town, although in practice, official use of the term varies widely.

History

...

status to local authorities. Otherwise, the Privy Council's powers have now been largely replaced by its executive committee, the Cabinet of the United Kingdom. The council is administratively headed by the Lord President of the Council who is a member of the cabinet, and appointed on the advice of the Prime Minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

.

Certain judicial functions are also performed by the King-in-Council, although in practice its actual work of hearing and deciding upon cases is carried out day-to-day by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. The Judicial Committee consists of senior judges appointed as privy counsellors: predominantly justices of the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom and senior judges from the Commonwealth. The Privy Council formerly acted as the final court of appeal for the entire British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

(other than for the United Kingdom itself). It continues to be the highest court of appeal in some Commonwealth countries

The Commonwealth of Nations, often referred to as the British Commonwealth or simply the Commonwealth, is an international association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire from which i ...

, Crown Dependencies

The Crown Dependencies are three dependent territory, offshore island territories in the British Islands that are self-governing possessions of the The Crown, British Crown: the Bailiwick of Guernsey and the Jersey, Bailiwick of Jersey, both lo ...

, British Overseas Territories

The British Overseas Territories (BOTs) or alternatively referred to as the United Kingdom Overseas Territories (UKOTs) are the fourteen dependent territory, territories with a constitutional and historical link with the United Kingdom that, ...

, as well as for a few institutions in the United Kingdom.

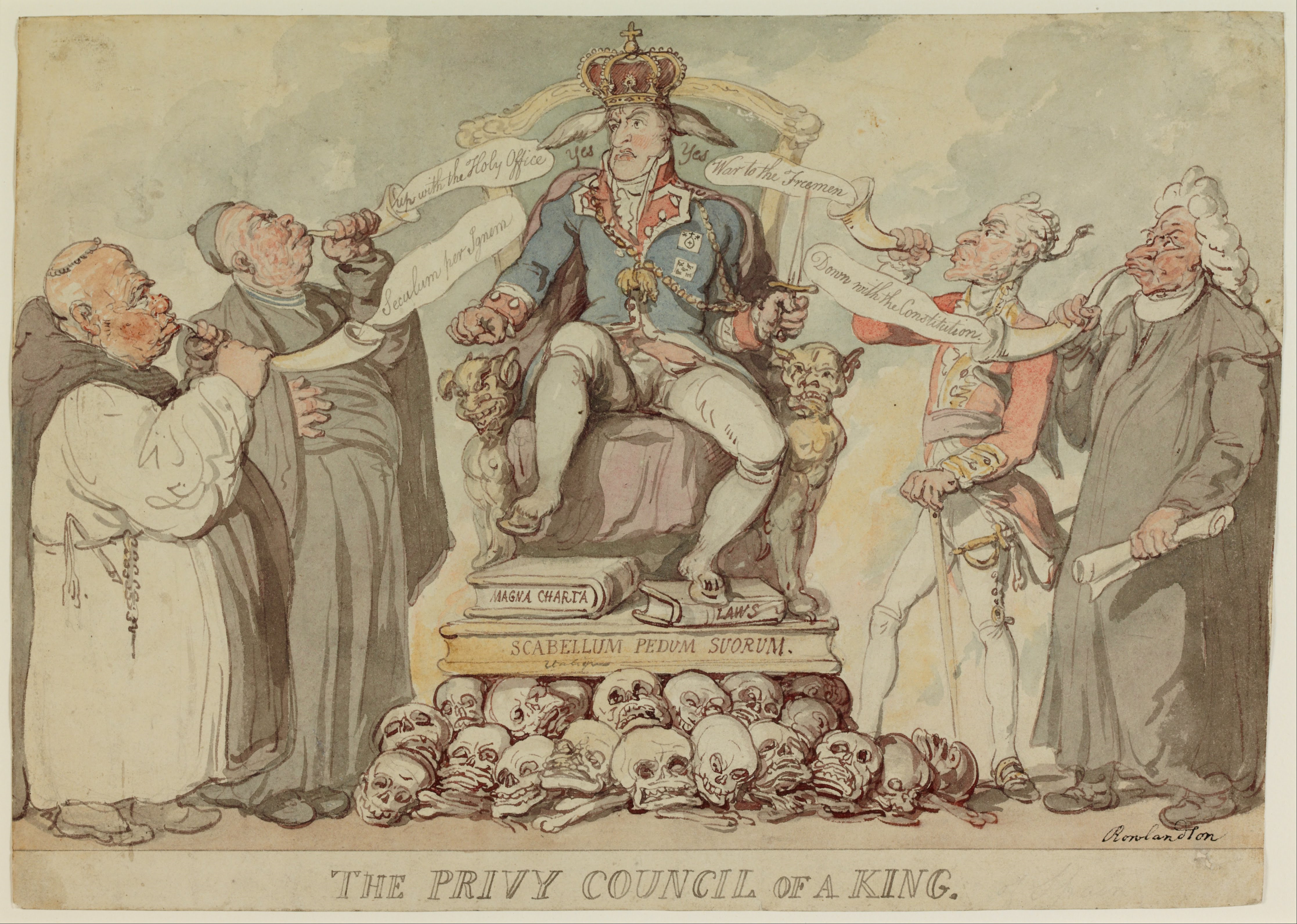

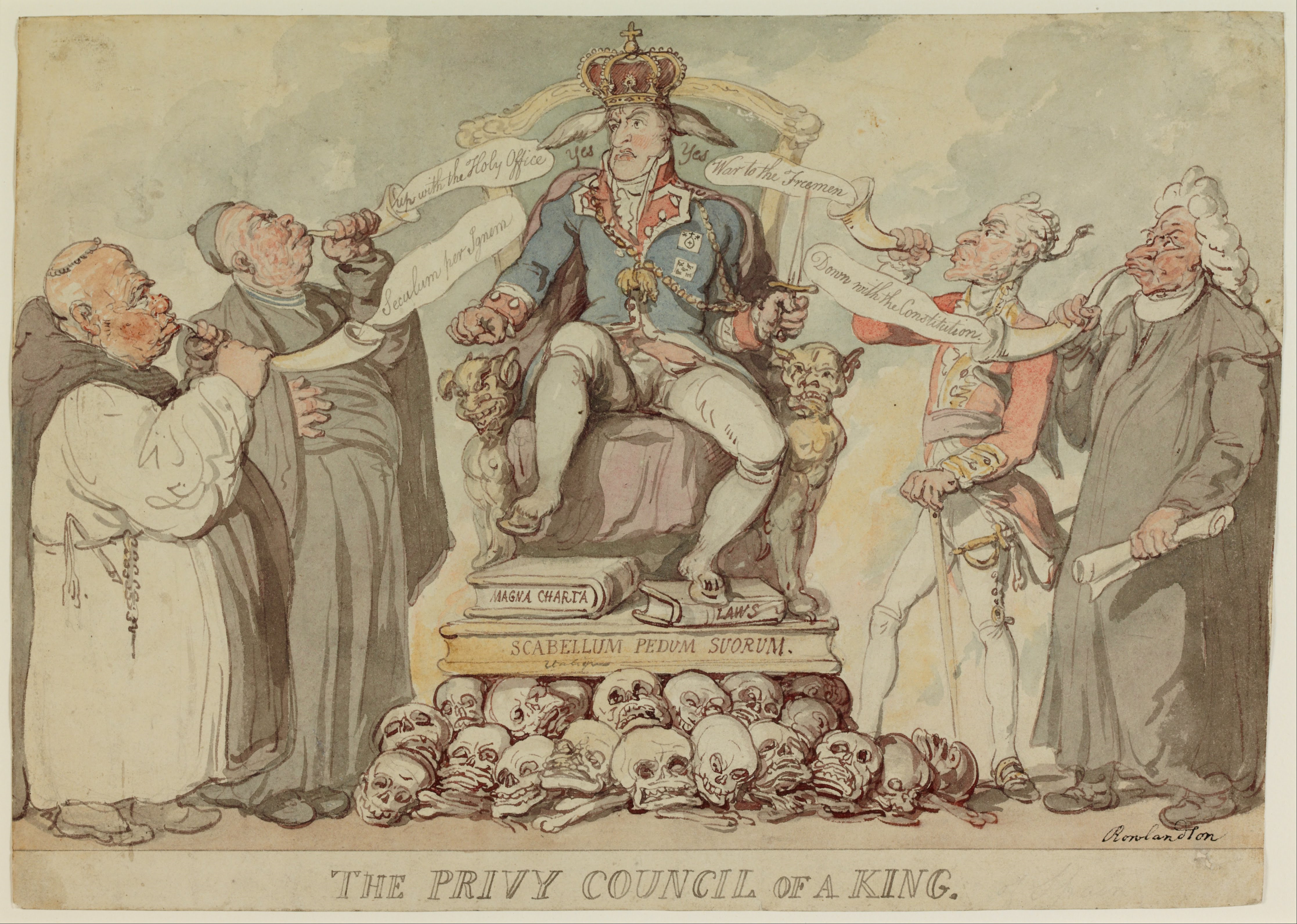

History

The Privy Council of the United Kingdom, created on 1 January 1801, was preceded by the Privy Council ofScotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

, the Privy Council of England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

, and the Privy Council of Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

(1708–1800). Its continued existence has been described as "more or less a constitutional and historical accident". The key events in the formation of the modern Privy Council are given below:

In Anglo-Saxon England, the Witenagemot was an early equivalent to the Privy Council of England. During the reigns of the Norman monarchs, the English Crown was advised by a royal court or , which consisted of magnates, ecclesiastics and high officials. The body originally concerned itself with advising the sovereign on legislation, administration and justice. Later, different bodies assuming distinct functions evolved from the court. The courts of law took over the business of dispensing justice

In its broadest sense, justice is the idea that individuals should be treated fairly. According to the ''Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy'', the most plausible candidate for a core definition comes from the ''Institutes (Justinian), Inst ...

, while Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

became the supreme legislature of the kingdom. Nevertheless, the Council retained the power to hear legal disputes, either in the first instance or on appeal. Furthermore, laws made by the sovereign on the advice of the Council, rather than on the advice of Parliament, were accepted as valid.Gay, p. 2. Powerful sovereigns often used the body to circumvent the Courts and Parliament. For example, a committee of the Council—which later became the Court of the Star Chamber—was during the 15th century permitted to inflict any punishment except death, without being bound by normal court procedure. During Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his Wives of Henry VIII, six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. ...

's reign, the sovereign, on the advice of the Council, was allowed to enact laws by mere proclamation. The legislative pre-eminence of Parliament was not restored until after Henry VIII's death. By 1540 the nineteen-member council had become a new national institution, most probably the creation of Thomas Cromwell

Thomas Cromwell (; – 28 July 1540) was an English statesman and lawyer who served as List of English chief ministers, chief minister to King Henry VIII from 1534 to 1540, when he was beheaded on orders of the king, who later blamed false cha ...

, without there being exact definitions of its powers. Though the royal Council retained legislative and judicial responsibilities, it became a primarily administrative body. In 1553 the Council consisted of forty members, whereas Henry VII swore over a hundred servants to his council. Sovereigns relied on a smaller working committee which evolved into the modern Cabinet.

By the end of the English Civil War

The English Civil War or Great Rebellion was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Cavaliers, Royalists and Roundhead, Parliamentarians in the Kingdom of England from 1642 to 1651. Part of the wider 1639 to 1653 Wars of th ...

, the monarchy, House of Lords, and Privy Council had been abolished. The remaining parliamentary chamber, the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

, instituted a Council of State

A council of state is a governmental body in a country, or a subdivision of a country, with a function that varies by jurisdiction. It may be the formal name for the cabinet or it may refer to a non-executive advisory body associated with a head ...

to execute laws and to direct administrative policy. The forty-one members of the Council were elected by the House of Commons; the body was headed by Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in British history. He came to prominence during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, initially ...

, ''de facto'' military dictator of the nation. In 1653, however, Cromwell became Lord Protector

Lord Protector (plural: ''Lords Protector'') is a title that has been used in British constitutional law for the head of state. It was also a particular title for the British heads of state in respect to the established church. It was sometime ...

, and the Council was reduced to between thirteen and twenty-one members, all elected by the Commons. In 1657, the Commons granted Cromwell even greater powers, some of which were reminiscent of those enjoyed by monarchs. The Council became known as the Protector's Privy Council; its members were appointed by the Lord Protector, subject to Parliament's approval.

In 1659, shortly before the restoration of the monarchy, the Protector's Council was abolished. King Charles II restored the Royal Privy Council, but he, like previous Stuart monarchs, chose to rely on a small group of advisers. The formation of the Kingdom of Great Britain

Great Britain, also known as the Kingdom of Great Britain, was a sovereign state in Western Europe from 1707 to the end of 1800. The state was created by the 1706 Treaty of Union and ratified by the Acts of Union 1707, which united the Kingd ...

in 1707 combined the Privy Councils of England and Scotland, the latter body coming to an end in 1708.

Under King George I, even more power transferred to a small committee of the Council, which began to meet in the absence of the sovereign, communicating its decisions to him after the fact. Thus, the Privy Council, as a whole, ceased to be a body of important confidential advisers to the Sovereign; the role passed to a committee of the Council, now known as the Cabinet.

With the creation of the United Kingdom on 1 January 1801, a single Privy Council was created for Great Britain and Ireland, although the Privy Council of Ireland

His or Her Majesty's Privy Council in Ireland, commonly called the Privy Council of Ireland, Irish Privy Council, or in earlier centuries the Irish Council, was the institution within the Dublin Castle administration which exercised formal executi ...

continued to exist until 1922, when it was abolished upon the creation of the Irish Free State

The Irish Free State (6 December 192229 December 1937), also known by its Irish-language, Irish name ( , ), was a State (polity), state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-ye ...

as an independent Dominion

A dominion was any of several largely self-governance, self-governing countries of the British Empire, once known collectively as the ''British Commonwealth of Nations''. Progressing from colonies, their degrees of self-governing colony, colon ...

outside the United Kingdom, but within the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

. The Privy Council of Northern Ireland was created in 1922, but became defunct in 1972, when the Parliament of Northern Ireland was closed down.

Functions

The sovereign may make Orders in Council upon the advice of the Privy Council. Orders in Council, which are drafted by thegovernment

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive (government), execu ...

rather than by the sovereign, are forms of either primary or secondary legislation, depending on the power they are made under. Orders made under prerogative

In law, a prerogative is an exclusive right bestowed by a government or State (polity), state and invested in an individual or group, the content of which is separate from the body of rights enjoyed under the general law. It was a common facet of ...

powers, such as the power to grant royal assent

Royal assent is the method by which a monarch formally approves an act of the legislature, either directly or through an official acting on the monarch's behalf. In some jurisdictions, royal assent is equivalent to promulgation, while in othe ...

to legislation, are a form of primary legislation, while orders made under statutory powers are a form of secondary legislation.

Orders of Council, distinct from Orders in Council, are issued by members of the Privy Council without requiring the approval of the sovereign. Like Orders in Council, they can be made under statutory powers or royal prerogative. Orders of Council are most commonly used for the regulation of public institutions and regulatory bodies.

The sovereign also grants royal charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, but ...

s on the advice of the Privy Council. Charters bestow special status to incorporated bodies; they are used to grant chartered status to certain professional, educational or charitable bodies, and sometimes also city

A city is a human settlement of a substantial size. The term "city" has different meanings around the world and in some places the settlement can be very small. Even where the term is limited to larger settlements, there is no universally agree ...

and borough

A borough is an administrative division in various English language, English-speaking countries. In principle, the term ''borough'' designates a self-governing walled town, although in practice, official use of the term varies widely.

History

...

status to towns. The Privy Council therefore deals with a wide range of matters, which also includes university and livery company statutes,Gay and Rees, p. 5. churchyard

In Christian countries, a churchyard is a patch of land adjoining or surrounding a church (building), church, which is usually owned by the relevant church or local parish itself. In the Scots language and in both Scottish English and Ulster S ...

s, coinage and the dates of bank holidays. The Privy Council formerly had sole power to grant academic degree-awarding powers and the title of university

A university () is an educational institution, institution of tertiary education and research which awards academic degrees in several Discipline (academia), academic disciplines. ''University'' is derived from the Latin phrase , which roughly ...

, but following the Higher Education and Research Act 2017

The Higher Education and Research Act 2017 (c. 29) was enacted into law in the United Kingdom by the Houses of Parliament on 27 April 2017. It is intended to create a new regulatory framework for Higher education in the United Kingdom, higher edu ...

these powers have been transferred to the Office for Students

The Office for Students (OfS) is a non-departmental public body of the Department for Education of the Government of the United Kingdom, United Kingdom Government. It acts as the regulator and competition authority for the higher education sector ...

for educational institutions in England.

Notable orders

Before the Constitutional Reform and Governance Act 2010 theCivil Service

The civil service is a collective term for a sector of government composed mainly of career civil service personnel hired rather than elected, whose institutional tenure typically survives transitions of political leadership. A civil service offic ...

was governed by powers of royal prerogative

The royal prerogative is a body of customary authority, Privilege (law), privilege, and immunity recognised in common law (and sometimes in Civil law (legal system), civil law jurisdictions possessing a monarchy) as belonging to the monarch, so ...

. These powers were usually delegated to ministers by Orders in Council, and were used by Margaret Thatcher to ban GCHQ

Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) is an intelligence and security organisation responsible for providing signals intelligence (SIGINT) and information assurance (IA) to the government and armed forces of the United Kingdom. Primar ...

staff from joining trade unions.

Another, the Civil Service (Amendment) Order in Council 1997, permitted the Prime Minister to grant up to three political advisers management authority over some Civil Servants.BBC Radio 4

BBC Radio 4 is a British national radio station owned and operated by the BBC. The station replaced the BBC Home Service on 30 September 1967 and broadcasts a wide variety of spoken-word programmes from the BBC's headquarters at Broadcasti ...

�What's the Point of ... The Privy Council

, 12 May 2009 In the 1960s, the Privy Council made an order to evict an estimated 1,200 to 2,000 inhabitants of the 55-island Chagos Archipelago in the Indian Ocean, in preparation for the establishment of a joint United States–United Kingdom military base on the largest island in the archipelago, Diego Garcia. In 2000, the

High Court of Justice

The High Court of Justice in London, known properly as His Majesty's High Court of Justice in England, together with the Court of Appeal (England and Wales), Court of Appeal and the Crown Court, are the Courts of England and Wales, Senior Cour ...

ruled that the inhabitants had a right to return to the archipelago.

In 2004, the Privy Council, under Jack Straw's tenure, overturned the ruling. In 2006, the High Court of Justice

The High Court of Justice in London, known properly as His Majesty's High Court of Justice in England, together with the Court of Appeal (England and Wales), Court of Appeal and the Crown Court, are the Courts of England and Wales, Senior Cour ...

found the Privy Council's decision to be unlawful. Justice Kentridge stated that there was no known precedent

Precedent is a judicial decision that serves as an authority for courts when deciding subsequent identical or similar cases. Fundamental to common law legal systems, precedent operates under the principle of ''stare decisis'' ("to stand by thin ...

"for the lawful use of prerogative powers to remove or exclude an entire population of British subjects from their homes and place of birth",BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...

�Court victory for Chagos families

, 11 May 2006 and the Court of Appeal were persuaded by this argument, but in 2007 the Law Lords of the Appellate Committee of the House of Lords found the original decision to be flawed and overturned the ruling by a 3–2 decision, thereby upholding the terms of the Order in Council. As of 2023, negotiations between the Mauritian and UK governments that included the sovereignty of the Chagossians were still ongoing.

Committees

The Privy Council have the following committees:

The Privy Council have the following committees:

Baronetage Committee

The Baronetage Committee was established by a 1910 Order in Council, duringEdward VII

Edward VII (Albert Edward; 9 November 1841 – 6 May 1910) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 22 January 1901 until Death and state funeral of Edward VII, his death in 1910.

The second child ...

's reign, to scrutinise all succession claims (and thus reject doubtful ones) to be placed on the Roll of Baronets.

Committee for the Affairs of Jersey and Guernsey

The Committee for the Affairs of Jersey and Guernsey recommends approval ofChannel Islands

The Channel Islands are an archipelago in the English Channel, off the French coast of Normandy. They are divided into two Crown Dependencies: the Jersey, Bailiwick of Jersey, which is the largest of the islands; and the Bailiwick of Guernsey, ...

legislation.

Committee for the Purposes of the Crown Office Act 1877

The Committee for the purposes of the Crown Office Act 1877 consists of theLord Chancellor

The Lord Chancellor, formally titled Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom. The lord chancellor is the minister of justice for England and Wales and the highest-ra ...

and Lord Privy Seal as well as a secretary of state. The Committee, which last met in 1988, is concerned with the design and usage of wafer seals.

Executive Committee

The Cabinet of the United Kingdom is the executive committee of the Privy Council and the senior decision-making body of British Government.Judicial Committee

The Judicial Committee serves as the final court of appeal for theCrown Dependencies

The Crown Dependencies are three dependent territory, offshore island territories in the British Islands that are self-governing possessions of the The Crown, British Crown: the Bailiwick of Guernsey and the Jersey, Bailiwick of Jersey, both lo ...

, the British Overseas Territories

The British Overseas Territories (BOTs) or alternatively referred to as the United Kingdom Overseas Territories (UKOTs) are the fourteen dependent territory, territories with a constitutional and historical link with the United Kingdom that, ...

, some Commonwealth countries, military sovereign base areas and a few institutions in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

. The Judicial Committee also hears very occasional appeals from a number of ancient and ecclesiastical courts. These include the Church Commissioners, the Arches Court of Canterbury, the Chancery Court of York, prize courts, the High Court of Chivalry, and the Court of Admiralty of the Cinque Ports. This committee usually consists of members of the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom and senior judges of the Commonwealth of Nations

The Commonwealth of Nations, often referred to as the British Commonwealth or simply the Commonwealth, is an International organization, international association of member states of the Commonwealth of Nations, 56 member states, the vast majo ...

who are Privy Counsellors.

Within the United Kingdom, the Judicial Committee hears appeals from ecclesiastical courts

In organized Christianity, an ecclesiastical court, also called court Christian or court spiritual, is any of certain non-adversarial courts conducted by church-approved officials having jurisdiction mainly in spiritual or religious matters. Histo ...

, the Admiralty Court of the Cinque Ports, Prize Courts and the Disciplinary Committee of the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons, appeals against schemes of the Church Commissioners and appeals under certain Acts of Parliament (e.g., the House of Commons Disqualification Act 1975). The Crown-in-Council was formerly the supreme appellate court for the entire British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

, but a number of Commonwealth countries have now abolished the right to such appeals. The Judicial Committee continues to hear appeals from several Commonwealth countries, from British Overseas Territories

The British Overseas Territories (BOTs) or alternatively referred to as the United Kingdom Overseas Territories (UKOTs) are the fourteen dependent territory, territories with a constitutional and historical link with the United Kingdom that, ...

, Sovereign Base Areas and Crown Dependencies

The Crown Dependencies are three dependent territory, offshore island territories in the British Islands that are self-governing possessions of the The Crown, British Crown: the Bailiwick of Guernsey and the Jersey, Bailiwick of Jersey, both lo ...

. The Judicial Committee had direct jurisdiction in cases relating to the Scotland Act 1998, the Government of Wales Act 1998

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government is a ...

and the Northern Ireland Act 1998, but this was transferred to the new Supreme Court of the United Kingdom in 2009.Gay and Rees, p. 6.

Scottish Universities Committee

The Scottish Universities Committee considers proposed amendments to the statutes of Scotland's four ancient universities.Universities Committee

The Universities Committee, which last met in 1995, considerspetition

A petition is a request to do something, most commonly addressed to a government official or public entity. Petitions to a deity are a form of prayer called supplication.

In the colloquial sense, a petition is a document addressed to an officia ...

s against statutes made by Oxford and Cambridge universities and their colleges.

Board of Trade

The Committee for Trade and Foreign Plantations is responsible for foreign trade and used to manage the Crown colonies, but currently has only one member (thePresident of the Board of Trade

The president of the Board of Trade is head of the Board of Trade. A committee of the His Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council, Privy Council of the United Kingdom, it was first established as a temporary committee of inquiry in the 17th centur ...

).

Other committees

In addition to the standing committees, ''ad hoc'' committees are notionally set up to consider and report on petitions forroyal charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, but ...

s of Incorporation and to approve changes to the bye-laws of bodies created by royal charter.

Committees of privy counsellors are occasionally established to examine specific issues. Such committees are independent of the Privy Council Office and therefore do not report directly to the lord president of the council. Examples of such committees include:

* the Butler Committee – operation of the intelligence services in the runup to military intervention in Iraq

* the Chilcot Committee – for the Chilcot Inquiry on the use of intercept materials

* the Gibson Committee of enquiry set up in 2010 – to consider whether the UK security services were complicit in torture of detainees.

Former committees

Historical, but now defunct committees include: * Lord President's Committee * Court of Star ChamberMembership

Composition

The Sovereign, when acting on the Council's advice, is known as the '' King-in-Council'' or '' Queen-in-Council'', depending on the sex of the reigning monarch. The members of the Council are collectively known as ''The Lords of His Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council'' (sometimes ''The Lords and others of ...''). The chief officer of the body is the Lord President of the Council, who is the fourth-highest

The Sovereign, when acting on the Council's advice, is known as the '' King-in-Council'' or '' Queen-in-Council'', depending on the sex of the reigning monarch. The members of the Council are collectively known as ''The Lords of His Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council'' (sometimes ''The Lords and others of ...''). The chief officer of the body is the Lord President of the Council, who is the fourth-highest Great Officer of State

Government in medieval monarchies generally comprised the king's companions, later becoming the royal household, from which the officers of state arose. These officers initially had household and governmental duties. Later some of these offic ...

, a Cabinet member and normally, either the Leader of the House of Lords or of the House of Commons. Another important official is the Clerk

A clerk is a white-collar worker who conducts record keeping as well as general office tasks, or a worker who performs similar sales-related tasks in a retail environment. The responsibilities of clerical workers commonly include Records managem ...

, whose signature is appended to all orders made in the Council.

Both ''Privy Counsellor'' and ''Privy Councillor'' may correctly be used to refer to a member of the Council. The former, however, is preferred by the Privy Council Office, emphasising English usage of the term ''Counsellor'' as "one who gives counsel", as opposed to "one who is a member of a council". A Privy Counsellor is traditionally said to be "''sworn of''" the Council after being received by the sovereign.

The sovereign may appoint any person as a Privy Counsellor, but in practice, appointments are made only on the advice of His Majesty's Government

His Majesty's Government, abbreviated to HM Government or otherwise UK Government, is the central government, central executive authority of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

. The majority of appointees are senior politicians, including ministers of the Crown, the leader of the main opposition party, the leader of the third-largest party in the House of Commons, the heads of the devolved administrations, and senior politicians from Commonwealth countries. Besides these, the Council includes a small number of members of the Royal Family

A royal family is the immediate family of monarchs and sometimes their extended family.

The term imperial family appropriately describes the family of an emperor or empress, and the term papal family describes the family of a pope, while th ...

, some senior British and Commonwealth judges, some senior clergy, and a small number of senior civil servants.

There is no statutory limit to the membership of the Privy Council.Gay, p. 3. Members have no automatic right to attend all Privy Council meetings, and only some are summoned regularly to meetings (in practice at the Prime Minister's discretion).

The Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

's three senior bishops – the Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the Primus inter pares, ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the bishop of the diocese of Canterbury. The first archbishop ...

, the Archbishop of York

The archbishop of York is a senior bishop in the Church of England, second only to the archbishop of Canterbury. The archbishop is the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of York and the metropolitan bishop of the province of York, which covers the ...

and the Bishop of London

The bishop of London is the Ordinary (church officer), ordinary of the Church of England's Diocese of London in the Province of Canterbury. By custom the Bishop is also Dean of the Chapel Royal since 1723.

The diocese covers of 17 boroughs o ...

– become privy counsellors upon appointment. Senior members of the Royal Family may also be appointed, but this is confined to the Monarch's consort __NOTOC__

Consort may refer to:

Music

* "The Consort" (Rufus Wainwright song), from the 2000 album ''Poses''

* Consort of instruments, term for instrumental ensembles

* Consort song (musical), a characteristic English song form, late 16th–earl ...

, heir apparent

An heir apparent is a person who is first in the order of succession and cannot be displaced from inheriting by the birth of another person. A person who is first in the current order of succession but could be displaced by the birth of a more e ...

, and heir apparent's spouse. The Private Secretary to the Sovereign is always appointed a Privy Counsellor, as are the Lord Chamberlain, the Speaker of the House of Commons, and the Lord Speaker. Justices of the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom, judges of the Court of Appeal of England and Wales

The Court of Appeal (formally "His Majesty's Court of Appeal in England", commonly cited as "CA", "EWCA" or "CoA") is the highest court within the Senior Courts of England and Wales, and second in the legal system of England and Wales only to ...

, senior judges of the Inner House of the Court of Session (Scotland's highest law court) and the Lord Chief Justice of Northern Ireland also join the Privy Council ''ex officio''.

The balance of Privy Counsellors is largely made up of politicians. The Prime Minister, Cabinet ministers and the Leader of HM Opposition are traditionally sworn into the Privy Council upon appointment. Leaders of major parties in the House of Commons, first ministers of the devolved administrations, some senior ministers outside Cabinet, and on occasion other respected senior parliamentarians are appointed privy counsellors.

Because Privy Counsellors are bound by oath

Traditionally, an oath (from Old English, Anglo-Saxon ', also a plight) is a utterance, statement of fact or a promise taken by a Sacred, sacrality as a sign of Truth, verity. A common legal substitute for those who object to making sacred oaths ...

to keep matters discussed at Council meetings secret, the appointment of the leaders of opposition parties as privy counsellors allows the Government to share confidential information with them "on Privy Council terms". This usually only happens in special circumstances, such as in matters of national security

National security, or national defence (national defense in American English), is the security and Defence (military), defence of a sovereign state, including its Citizenship, citizens, economy, and institutions, which is regarded as a duty of ...

. For example, Tony Blair

Sir Anthony Charles Lynton Blair (born 6 May 1953) is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1997 to 2007 and Leader of the Labour Party (UK), Leader of the Labour Party from 1994 to 2007. He was Leader ...

met Iain Duncan Smith (then Leader of HM Opposition) and Charles Kennedy (then Leader of the Liberal Democrats) "on Privy Council terms" to discuss the evidence for Iraq's weapons of mass destruction.

Members from other Commonwealth realms

Although the Privy Council is primarily a British institution, officials from some otherCommonwealth realm

A Commonwealth realm is a sovereign state in the Commonwealth of Nations that has the same constitutional monarch and head of state as the other realms. The current monarch is King Charles III. Except for the United Kingdom, in each of the re ...

s are also appointed. By 2000, the most notable instance was New Zealand, whose prime minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

, senior politicians, chief justice and Court of Appeal justices were traditionally appointed privy counsellors. However, appointments of New Zealand members have since been discontinued. The prime minister, the speaker, the governor-general

Governor-general (plural governors-general), or governor general (plural governors general), is the title of an official, most prominently associated with the British Empire. In the context of the governors-general and former British colonies, ...

and the chief justice are still accorded the style

Style, or styles may refer to:

Film and television

* ''Style'' (2001 film), a Hindi film starring Sharman Joshi, Riya Sen, Sahil Khan and Shilpi Mudgal

* ''Style'' (2002 film), a Tamil drama film

* ''Style'' (2004 film), a Burmese film

* '' ...

''Right Honourable

''The Right Honourable'' (abbreviation: The Rt Hon. or variations) is an honorific style traditionally applied to certain persons and collective bodies in the United Kingdom, the former British Empire, and the Commonwealth of Nations. The term is ...

'', but without membership of the Council. Until the late 20th century, the prime ministers and chief justices of Canada and Australia were also appointed privy counsellors. Canada also has its own Privy Council, the King's Privy Council for Canada (''see'' below). Prime ministers of some other Commonwealth countries that retain the King as their sovereign continue to be sworn of the Council.

Meetings

Meetings of the Privy Council are normally held once each month wherever the Sovereign may be in residence at the time. The quorum, according to the Privy Council Office, is three, though some statutes provide for other quorums (for example, section 35 of the Opticians Act 1989 provides for a lower quorum of two). The Sovereign attends the meeting, though their place may be taken by two or more Counsellors of State.Gay and Rees, p. 4. Under the Regency Acts 1937 to 1953 and the Counsellors of State Act 2022, Counsellors of State may be chosen from among the sovereign's spouse, the four individuals next in the line of succession who are over 21 years of age (18 for the first in line), Prince Edward and Princess Anne. Customarily the sovereign remains standing at meetings of the Privy Council, so that no other members may sit down, thereby keeping meetings short. The Lord President reads out a list of orders to be made, and the sovereign merely says "Approved". Few Privy Counsellors are required to attend regularly. The settled practice is that day-to-day meetings of the Council are attended by four Privy Counsellors, usually the relevant minister to the matter(s) pertaining. The Cabinet Minister holding the office of Lord President of the Council invariably presides. Under Britain's modern conventions of parliamentary government andconstitutional monarchy

Constitutional monarchy, also known as limited monarchy, parliamentary monarchy or democratic monarchy, is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in making decisions. ...

, every Order-in-Council is drafted by a government department

Ministry or department (also less commonly used secretariat, office, or directorate) are designations used by first-level Executive (government), executive bodies in the Machinery of government, machinery of governments that manage a specific se ...

and has already been approved by the minister responsible – thus actions taken by the King-in-Council are formalities required for validation of each measure.

Full meetings of the Privy Council are held only when the reigning Sovereign announces their own engagement (which last happened on 23 November 1839, in the reign of Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in January 1901. Her reign of 63 year ...

); or when there is a Demise of the Crown, either by the death or abdication of the Monarch. A full meeting of the Privy Council was also held on 6 February 1811, when the Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales (, ; ) is a title traditionally given to the male heir apparent to the History of the English monarchy, English, and later, the British throne. The title originated with the Welsh rulers of Kingdom of Gwynedd, Gwynedd who, from ...

was sworn in as regent

In a monarchy, a regent () is a person appointed to govern a state because the actual monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge their powers and duties, or the throne is vacant and a new monarch has not yet been dete ...

by Act of Parliament. The statutes regulating the establishment of a regency in the case of minority or incapacity of the sovereign also require any regents to swear their oaths before the Privy Council.

In the case of a Demise of the Crown, the Privy Council – together with the Lords Spiritual

The Lords Spiritual are the bishops of the Church of England who sit in the House of Lords of the United Kingdom. Up to 26 of the 42 diocesan bishops and archbishops of the Church of England serve as Lords Spiritual (not including retired bish ...

, the Lords Temporal

The Lords Temporal are secular members of the House of Lords, the upper house of the British Parliament. These can be either life peers or hereditary peers, although the hereditary right to sit in the House of Lords was abolished for all but n ...

, the Lord Mayor of the City of London and Court of Aldermen of the City of London

The City of London, also known as ''the City'', is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county and Districts of England, local government district with City status in the United Kingdom, city status in England. It is the Old town, his ...

as well as representatives of Commonwealth realm

A Commonwealth realm is a sovereign state in the Commonwealth of Nations that has the same constitutional monarch and head of state as the other realms. The current monarch is King Charles III. Except for the United Kingdom, in each of the re ...

s – makes a proclamation declaring the accession of the new Sovereign and receives an oath from the new Monarch relating to the security of the Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland (CoS; ; ) is a Presbyterian denomination of Christianity that holds the status of the national church in Scotland. It is one of the country's largest, having 245,000 members in 2024 and 259,200 members in 2023. While mem ...

, as required by law. It is also customary for the new Sovereign to make an allocution to the Privy Council on that occasion, and this Sovereign's Speech is formally published in ''The London Gazette''. Any such Special Assembly of the Privy Council, convened to proclaim the accession of a new Sovereign and witness the Monarch's statutory oath, is known as an Accession Council. The last such meeting was held on 10 September 2022 following the death of Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 19268 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until Death and state funeral of Elizabeth II, her death in 2022. ...

and the accession of Charles III

Charles III (Charles Philip Arthur George; born 14 November 1948) is King of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth realms.

Charles was born at Buckingham Palace during the reign of his maternal grandfather, King George VI, and ...

.

Term of office

Membership is conferred for life. Formerly, the death of a monarch (" demise of the Crown") brought an immediate dissolution of the council, as all Crown appointments automatically lapsed. By the 18th century, it was enacted that the council would not be dissolved until up to six months after the demise of the Crown. By convention, however, the sovereign would reappoint all members of the council after its dissolution. In practice, therefore, membership continued without a break. In 1901, the law was changed to ensure that Crown appointments became wholly unaffected by any succession of monarch. The sovereign, however, may remove an individual from the Privy Council. Former MP Elliot Morley was expelled on 8 June 2011, following hisconviction

In law, a conviction is the determination by a court of law that a defendant is Guilty (law), guilty of a crime. A conviction may follow a guilty plea that is accepted by the court, a jury trial in which a verdict of guilty is delivered, or a ...

on charges of false accounting in connection with the British parliamentary expenses scandal. Before this, the last individual to be expelled from the Council was Sir Edgar Speyer, Bt., who was removed on 13 December 1921 for collaborating with the enemy German Empire

The German Empire (),; ; World Book, Inc. ''The World Book dictionary, Volume 1''. World Book, Inc., 2003. p. 572. States that Deutsches Reich translates as "German Realm" and was a former official name of Germany. also referred to as Imperia ...

, during the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

.

Individuals can choose to resign, sometimes to avoid expulsion. Three members voluntarily left the Privy Council in the 20th century: John Profumo, who resigned on 26 June 1963; John Stonehouse, who resigned on 17 August 1976 and Jonathan Aitken, who resigned on 25 June 1997 following allegations of perjury.

So far, four Privy Counsellors have resigned in the 21st century, three in the same year. On 4 February 2013, Chris Huhne announced that he would voluntarily leave the Privy Council after pleading guilty to perverting the course of justice. Lord Prescott stood down on 6 July 2013, in protest against delays in the introduction of press regulation, expecting others to follow. Denis MacShane resigned on 9 October 2013, before an Old Bailey

The Central Criminal Court of England and Wales, commonly referred to as the Old Bailey after the street on which it stands, is a criminal court building in central London, one of several that house the Crown Court of England and Wales. The s ...

hearing at which he pleaded guilty of false accounting and was subsequently imprisoned. In April 2022, former Prime Minister of Jamaica P. J. Patterson resigned to make the case for Jamaica to become a republic.

Rights and privileges

The Privy Council as a whole is termed "The Most Honourable

The honorific prefix "The Most Honourable" is a form of address that is used in several countries. In the United Kingdom, it precedes the name of a marquess or marchioness.

Overview

In Jamaica, Governor-General of Jamaica, Governors-General of J ...

" whilst its members individually, the Privy Counsellors, are entitled to be styled "The Right Honourable

''The Right Honourable'' (abbreviation: The Rt Hon. or variations) is an honorific Style (form of address), style traditionally applied to certain persons and collective bodies in the United Kingdom, the former British Empire, and the Commonwealt ...

". Nonetheless, some nobles automatically have higher styles: non-royal Dukes are styled "His Grace" and "The Most Noble", and Marquesses as "The Most Honourable

The honorific prefix "The Most Honourable" is a form of address that is used in several countries. In the United Kingdom, it precedes the name of a marquess or marchioness.

Overview

In Jamaica, Governor-General of Jamaica, Governors-General of J ...

". Modern custom as recommended by '' Debrett's'' is to use the post-nominal letters "PC" in a social style of address for peers who are Privy Counsellors. For commoner

A commoner, also known as the ''common man'', ''commoners'', the ''common people'' or the ''masses'', was in earlier use an ordinary person in a community or nation who did not have any significant social status, especially a member of neither ...

s, "The Right Honourable" is sufficient identification of their status as a Privy Counsellor and they do not use the post-nominal letters "PC". The Ministry of Justice revises the practice of this convention from time to time.

Each Privy Counsellor has the right of personal access to the sovereign. Peers were considered to enjoy this right individually; members of the House of Commons possess the right collectively. In each case, personal access may only be used to tender advice on public affairs.N. Cox, ''Peerage Privileges'', pp. 25–6.

Only Privy Counsellors can signify Royal Consent to the examination of a Bill affecting the rights of the Crown.

Privy Counsellors have the right to sit on the steps of the Sovereign's Throne in the Chamber of the House of Lords during debates, a privilege which was shared with heirs apparent of those hereditary peer

The hereditary peers form part of the peerage in the United Kingdom. As of April 2025, there are 800 hereditary peers: 30 dukes (including six royal dukes), 34 marquesses, 189 earls, 108 viscounts, and 439 barons (not counting subsidiary ...

s who were to become members of the House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the lower house, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England. One of the oldest ext ...

before Labour's partial Reform of the Lords in 1999, diocesan bishops of the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

yet to be Lords Spiritual

The Lords Spiritual are the bishops of the Church of England who sit in the House of Lords of the United Kingdom. Up to 26 of the 42 diocesan bishops and archbishops of the Church of England serve as Lords Spiritual (not including retired bish ...

, retired bishops who formerly sat in the House of Lords, the Dean of Westminster, Peers of Ireland, the Clerk of the Crown in Chancery, and the Gentleman Usher of the Black Rod. While Privy Counsellors have the right to sit on the steps of the Sovereign's Throne they do so only as observers and are not allowed to participate in any of the workings of the House of Lords. Nowadays this privilege is rarely exercised. A notable recent instance of the exercising of this privilege was used by the Prime Minister, Theresa May, and David Lidington, who watched the opening of the debate of the European Union (Notification of Withdrawal) Bill 2017 in the House of Lords.

Privy Counsellors are accorded a formal rank of precedence, if not already having a higher one. At the beginning of each new Parliament, and at the discretion of the Speaker, those members of the House of Commons who are Privy Counsellors usually take the oath of allegiance before all other members except the Speaker and the Father of the House (who is the member of the House who has the longest continuous service). Should a Privy Counsellor rise to speak in the House of Commons at the same time as another Honourable Member, the Speaker usually gives priority to the "Right Honourable" Member. This parliamentary custom, however, was discouraged under New Labour after 1998, despite the government not being supposed to exert influence over the Speaker.

Oath and initiation rite

The oath of the king's council (later the Privy Council) was first formulated in the early thirteenth century. This oath went through a series of revisions, but the modern form of the oath was essentially settled in 1571. It was regarded by some members of the Privy Council as criminal, and possiblytreason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state (polity), state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to Coup d'état, overthrow its government, spy ...

ous, to disclose the oath

Traditionally, an oath (from Old English, Anglo-Saxon ', also a plight) is a utterance, statement of fact or a promise taken by a Sacred, sacrality as a sign of Truth, verity. A common legal substitute for those who object to making sacred oaths ...

administered to privy counsellors as they take office. However, the oath was officially made public by the Blair Government in a written parliamentary answer in 1998, as follows. It had also previously been read out in full in the House of Lords during debate by Lord Rankeillour on 21 December 1932, and has been openly printed in full in widely published books during the 19th and 20th centuries.

Privy counsellors can choose to affirm their allegiance in similar terms, should they prefer not to take a religious oath. At the induction ceremony, the order of precedence places Anglicans (being those of the established church) before others.

The initiation ceremony for newly appointed privy counsellors is held in private, and typically requires kneeling on a stool before the Sovereign and then kissing hands. According to ''The Royal Encyclopaedia'': "The new Privy Counsellor or Minister will extend his or her right hand, palm upwards, and, taking the Queen's hand lightly, will kiss it with no more than a touch of the lips." The ceremony has caused difficulties for Privy Counsellors who advocate republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology that encompasses a range of ideas from civic virtue, political participation, harms of corruption, positives of mixed constitution, rule of law, and others. Historically, it emphasizes the idea of self ...

; Tony Benn

Anthony Neil Wedgwood Benn (3 April 1925 – 14 March 2014), known between 1960 and 1963 as Viscount Stansgate, was a British Labour Party (UK), Labour Party politician and political activist who served as a Cabinet of the United Kingdom, Cabine ...

said in his diaries that he kissed his own thumb, rather than the Queen's hand, while Jeremy Corbyn

Jeremy Bernard Corbyn (; born 26 May 1949) is a British politician who has been Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), Member of Parliament (MP) for Islington North (UK Parliament constituency), Islington North since 1983. Now an Independent ...

reportedly did not kneel. Not all members of the Privy Council go through the initiation ceremony; appointments are frequently made by an Order in Council

An Order in Council is a type of legislation in many countries, especially the Commonwealth realms. In the United Kingdom, this legislation is formally made in the name of the monarch by and with the advice and consent of the Privy Council ('' ...

, although it is "rare for a party leader to use such a course."

Other councils

The Privy Council is one of the four principal councils of the sovereign. The other three are the courts of law, the '' Commune Concilium'' (Common Council, i.e. Parliament) and the '' Magnum Concilium'' (Great Council, i.e. the assembly of all the peers of the realm). All are still in existence, or at least have never been formally abolished, but the ''Magnum Concilium'' has not been summoned since 1640 and was considered defunct even then. Several other privy councils have advised the sovereign. England and Scotland once had separate privy councils (the Privy Council of England and Privy Council of Scotland). TheActs of Union 1707

The Acts of Union refer to two acts of Parliament, one by the Parliament of Scotland in March 1707, followed shortly thereafter by an equivalent act of the Parliament of England. They put into effect the international Treaty of Union agree ...

united the two countries into the Kingdom of Great Britain

Great Britain, also known as the Kingdom of Great Britain, was a sovereign state in Western Europe from 1707 to the end of 1800. The state was created by the 1706 Treaty of Union and ratified by the Acts of Union 1707, which united the Kingd ...

and in 1708 the Parliament of Great Britain

The Parliament of Great Britain was formed in May 1707 following the ratification of the Acts of Union 1707, Acts of Union by both the Parliament of England and the Parliament of Scotland. The Acts ratified the treaty of Union which created a ...

abolished the Privy Council of Scotland and the Privy Council of England. Thereafter there was one Privy Council of Great Britain sitting in London. Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

, on the other hand, continued to have a separate Privy Council even after the Act of Union 1800. The last appointments to the Privy Council of Ireland

His or Her Majesty's Privy Council in Ireland, commonly called the Privy Council of Ireland, Irish Privy Council, or in earlier centuries the Irish Council, was the institution within the Dublin Castle administration which exercised formal executi ...

were made in 1922, when the greater part of Ireland separated from the United Kingdom as an independent Dominion

A dominion was any of several largely self-governance, self-governing countries of the British Empire, once known collectively as the ''British Commonwealth of Nations''. Progressing from colonies, their degrees of self-governing colony, colon ...

. It was succeeded by the Privy Council of Northern Ireland, which became dormant after the suspension of the Parliament of Northern Ireland in 1972.

Canada has had its own Privy Council — the King's Privy Council for Canada — since 1867. While the Canadian Privy Council is specifically "for Canada", the Privy Council discussed above is not "for the United Kingdom"; to clarify the ambiguity where necessary, the latter was historically referred to as the Imperial Privy Council. Equivalent organs of state in other Commonwealth realms, such as Australia and New Zealand, are called Executive Councils.

See also

* List of Royal members of the Privy Council * List of current Privy Counsellors * List of Privy Council orders * Clerk to the Privy Council * Court uniform and dress in the United Kingdom * Historic list of Privy Counsellors * Minister of State for the Privy Council OfficeNotes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

Privy Council Office homepage

Judicial Committee of the Privy Council homepage

BBC: Do we need the Privy Council?

BBC: Privy Council: Guide to its origins, powers and members

8 October 2015 *

Guardian Comment – Roy Hattersley on the Privy Council

{{authority control History of the Commonwealth of Nations 1708 establishments in Great Britain