Heraclitus (; ; ) was an

ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

pre-Socratic

Pre-Socratic philosophy, also known as early Greek philosophy, is ancient Greek philosophy before Socrates. Pre-Socratic philosophers were mostly interested in cosmology, the beginning and the substance of the universe, but the inquiries of the ...

philosopher from the city of

Ephesus

Ephesus (; ; ; may ultimately derive from ) was an Ancient Greece, ancient Greek city on the coast of Ionia, in present-day Selçuk in İzmir Province, Turkey. It was built in the 10th century BC on the site of Apasa, the former Arzawan capital ...

, which was then part of the

Persian Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire, also known as the Persian Empire or First Persian Empire (; , , ), was an Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid dynasty in 550 BC. Based in modern-day Iran, it was the larg ...

. He exerts a wide influence on

Western philosophy

Western philosophy refers to the Philosophy, philosophical thought, traditions and works of the Western world. Historically, the term refers to the philosophical thinking of Western culture, beginning with the ancient Greek philosophy of the Pre ...

, both

ancient

Ancient history is a time period from the beginning of writing and recorded human history through late antiquity. The span of recorded history is roughly 5,000 years, beginning with the development of Sumerian cuneiform script. Ancient h ...

and

modern, through the works of such authors as

Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

,

Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

,

Hegel

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a 19th-century German idealism, German idealist. His influence extends across a wide range of topics from metaphysical issues in epistemology and ontology, to political phi ...

,

Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher. He began his career as a classical philologist, turning to philosophy early in his academic career. In 1869, aged 24, Nietzsche became the youngest pro ...

, and

Heidegger

Martin Heidegger (; 26 September 1889 – 26 May 1976) was a German philosopher known for contributions to phenomenology, hermeneutics, and existentialism. His work covers a range of topics including metaphysics, art, and language.

In April ...

.

Little is known of Heraclitus's life. He wrote a single work, only

fragments of which have survived. Even in ancient times, his

paradoxical

A paradox is a logically self-contradictory statement or a statement that runs contrary to one's expectation. It is a statement that, despite apparently valid reasoning from true or apparently true premises, leads to a seemingly self-contradictor ...

philosophy, appreciation for

wordplay, and cryptic, oracular

epigram

An epigram is a brief, interesting, memorable, sometimes surprising or satirical statement. The word derives from the Greek (, "inscription", from [], "to write on, to inscribe"). This literary device has been practiced for over two millennia ...

s earned him the epithets "the dark" and "the obscure". He was considered arrogant and depressed, a

misanthrope

Misanthropy is the general hatred, dislike, or distrust of the Human, human species, human behavior, or human nature. A misanthrope or misanthropist is someone who holds such views or feelings. Misanthropy involves a negative evaluative attitu ...

who was subject to

melancholia

Melancholia or melancholy (from ',Burton, Bk. I, p. 147 meaning black bile) is a concept found throughout ancient, medieval, and premodern medicine in Europe that describes a condition characterized by markedly depressed mood, bodily complain ...

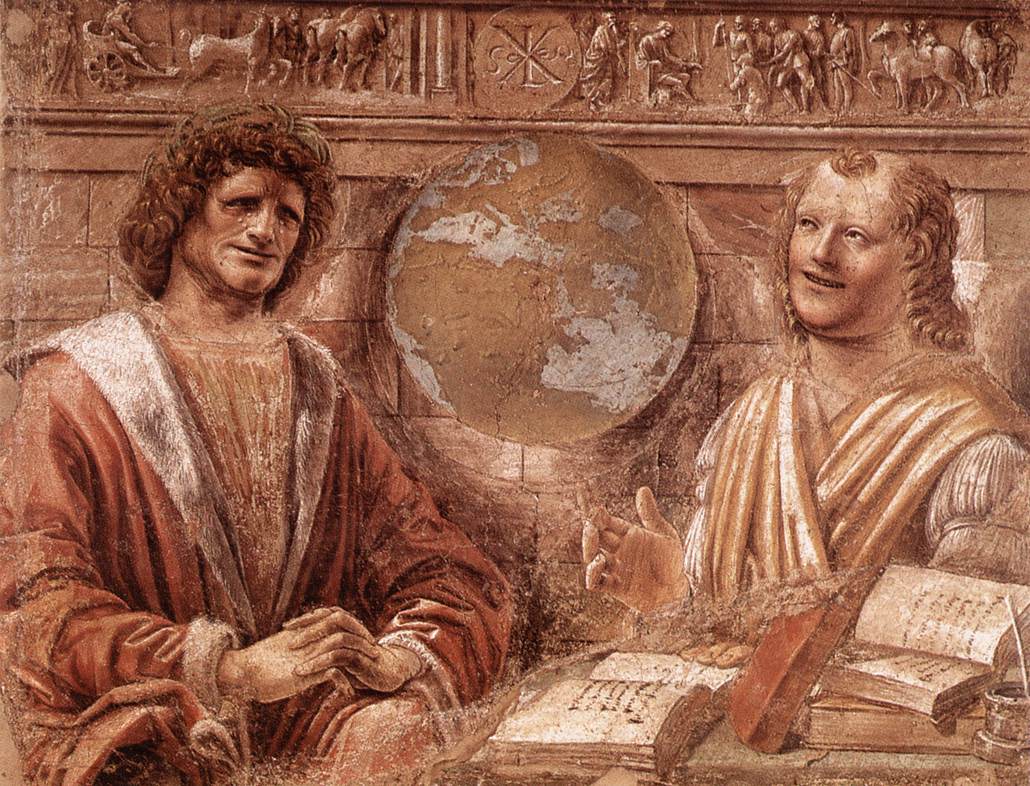

. Consequently, he became known as "the weeping philosopher" in contrast to the ancient

atomist philosopher

Democritus

Democritus (, ; , ''Dēmókritos'', meaning "chosen of the people"; – ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek Pre-Socratic philosophy, pre-Socratic philosopher from Abdera, Thrace, Abdera, primarily remembered today for his formulation of an ...

, who was known as "the laughing philosopher".

The central ideas of Heraclitus's philosophy are the

unity of opposites

The unity of opposites ( or ) is the philosophical idea that opposites are interconnected by the way each is defined in relation to the other. Their interdependence unites the seemingly opposed terms.

The unity of opposites is sometimes equated wi ...

and the concept of

change

Change, Changed or Changing may refer to the below. Other forms are listed at

Alteration

* Impermanence, a difference in a state of affairs at different points in time

* Menopause, also referred to as "the change", the permanent cessation of t ...

. Heraclitus saw

harmony

In music, harmony is the concept of combining different sounds in order to create new, distinct musical ideas. Theories of harmony seek to describe or explain the effects created by distinct pitches or tones coinciding with one another; harm ...

and

justice

In its broadest sense, justice is the idea that individuals should be treated fairly. According to the ''Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy'', the most plausible candidate for a core definition comes from the ''Institutes (Justinian), Inst ...

in

strife. He viewed the world as constantly in flux, always "becoming" but never "being". He expressed this in sayings like "Everything

flows" (, ''panta rhei'') and "No man ever steps in the same river twice". This insistence upon change contrasts with that of the ancient philosopher

Parmenides

Parmenides of Elea (; ; fl. late sixth or early fifth century BC) was a Pre-Socratic philosophy, pre-Socratic ancient Greece, Greek philosopher from Velia, Elea in Magna Graecia (Southern Italy).

Parmenides was born in the Greek colony of Veli ...

, who believed in a reality of static "

being

Existence is the state of having being or reality in contrast to nonexistence and nonbeing. Existence is often contrasted with essence: the essence of an entity is its essential features or qualities, which can be understood even if one do ...

".

Heraclitus believed fire was the ''

arche

In philosophy and science, a first principle is a basic proposition or assumption that cannot be deduced from any other proposition or assumption. First principles in philosophy are from first cause attitudes and taught by Aristotelians, and nuan ...

'', the fundamental stuff of the world. In choosing an ''arche'' Heraclitus followed the

Milesians before him —

Thales

Thales of Miletus ( ; ; ) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek Pre-Socratic philosophy, pre-Socratic Philosophy, philosopher from Miletus in Ionia, Asia Minor. Thales was one of the Seven Sages of Greece, Seven Sages, founding figure ...

with water,

Anaximander

Anaximander ( ; ''Anaximandros''; ) was a Pre-Socratic philosophy, pre-Socratic Ancient Greek philosophy, Greek philosopher who lived in Miletus,"Anaximander" in ''Chambers's Encyclopædia''. London: George Newnes Ltd, George Newnes, 1961, Vol. ...

with ''

apeiron

''Apeiron'' (; ) is a Greek word meaning '(that which is) unlimited; boundless; infinite; indefinite' from ''a-'' 'without' and ''peirar'' 'end, limit; boundary', the Ionic Greek form of ''peras'' 'end, limit, boundary'.

Origin of everything

...

'' ("boundless" or "infinite"), and

Anaximenes with air. Heraclitus also thought the ''

logos

''Logos'' (, ; ) is a term used in Western philosophy, psychology and rhetoric, as well as religion (notably Logos (Christianity), Christianity); among its connotations is that of a rationality, rational form of discourse that relies on inducti ...

'' (

lit. word, discourse, or reason) gave structure to the world.

Life

Heraclitus, the son of Blyson, was from the

Ionian city of Ephesus, a

port

A port is a maritime facility comprising one or more wharves or loading areas, where ships load and discharge cargo and passengers. Although usually situated on a sea coast or estuary, ports can also be found far inland, such as Hamburg, Manch ...

on the

Cayster River, on the western coast of

Asia Minor

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

(modern-day

Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

). In the 6th century BC, Ephesus, like other cities in

Ionia

Ionia ( ) was an ancient region encompassing the central part of the western coast of Anatolia. It consisted of the northernmost territories of the Ionian League of Greek settlements. Never a unified state, it was named after the Ionians who ...

, lived under the effects of both the rise of

Lydia

Lydia (; ) was an Iron Age Monarchy, kingdom situated in western Anatolia, in modern-day Turkey. Later, it became an important province of the Achaemenid Empire and then the Roman Empire. Its capital was Sardis.

At some point before 800 BC, ...

under

Croesus

Croesus ( ; ; Latin: ; reigned:

)

was the Monarch, king of Lydia, who reigned from 585 BC until his Siege of Sardis (547 BC), defeat by the Persian king Cyrus the Great in 547 or 546 BC. According to Herodotus, he reigned 14 years. Croesus was ...

and his overthrow by

Cyrus the Great

Cyrus II of Persia ( ; 530 BC), commonly known as Cyrus the Great, was the founder of the Achaemenid Empire. Achaemenid dynasty (i. The clan and dynasty) Hailing from Persis, he brought the Achaemenid dynasty to power by defeating the Media ...

c. 547 BC. Ephesus appears to have subsequently cultivated a close relationship with the Persian Empire; during the suppression of the

Ionian revolt by

Darius the Great

Darius I ( ; – 486 BCE), commonly known as Darius the Great, was the third King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 522 BCE until his death in 486 BCE. He ruled the empire at its territorial peak, when it included much of West A ...

in 494 BC, Ephesus was spared and emerged as the dominant

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

city in Ionia.

Miletus

Miletus (Ancient Greek: Μίλητος, Mílētos) was an influential ancient Greek city on the western coast of Anatolia, near the mouth of the Maeander River in present day Turkey. Renowned in antiquity for its wealth, maritime power, and ex ...

, the home to the previous philosophers, was captured and sacked.

The main source for the life of Heraclitus is the

doxographer Diogenes Laërtius

Diogenes Laërtius ( ; , ; ) was a biographer of the Greek philosophers. Little is definitively known about his life, but his surviving book ''Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers'' is a principal source for the history of ancient Greek ph ...

. Although most of the information provided by Laertius is unreliable, and the ancient stories about Heraclitus are thought to be later fabrications based on interpretations of the preserved fragments; the anecdote that Heraclitus relinquished the hereditary title of "king" to his younger brother may at least imply that Heraclitus was from an

aristocratic

Aristocracy (; ) is a form of government that places power in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocrats.

Across Europe, the aristocracy exercised immense economic, political, and social influence. In Western Christian co ...

family in Ephesus. Heraclitus appears to have had little sympathy for

democracy

Democracy (from , ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which political power is vested in the people or the population of a state. Under a minimalist definition of democracy, rulers are elected through competitiv ...

or

the masses. However, it is unclear whether he was "an unconditional partisan of the rich", or if, like the

sage Solon

Solon (; ; BC) was an Archaic Greece#Athens, archaic History of Athens, Athenian statesman, lawmaker, political philosopher, and poet. He is one of the Seven Sages of Greece and credited with laying the foundations for Athenian democracy. ...

, he was "withdrawn from competing factions".

Since antiquity, Heraclitus has been labeled a solitary figure and an arrogant misanthrope. The

skeptic Timon of Phlius

Timon of Phlius (; , , ; BCc. 235 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosopher from the Hellenistic period, who was the student of Pyrrho. Unlike Pyrrho, who wrote nothing, Timon wrote satirical philosophical poetry called ''Silloi'' () as well ...

called Heraclitus a "mob-abuser" (''ochloloidoros''). Heraclitus considered himself self-taught. He criticized fools for being "put in a flutter by every word". He did not consider others incapable, but unwilling: "And though reason is common, most people live as though they had an understanding peculiar to themselves." Heraclitus did not seem to like the prevailing religion of the time, criticizing the popular

mystery cults,

blood sacrifice, and

prayer

File:Prayers-collage.png, 300px, alt=Collage of various religionists praying – Clickable Image, Collage of various religionists praying ''(Clickable image – use cursor to identify.)''

rect 0 0 1000 1000 Shinto festivalgoer praying in front ...

to statues. He also did not believe in

funeral rites, saying "Corpses are more fit to be cast out than dung." He further criticized

Homer

Homer (; , ; possibly born ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Despite doubts about his autho ...

,

Hesiod

Hesiod ( or ; ''Hēsíodos''; ) was an ancient Greece, Greek poet generally thought to have been active between 750 and 650 BC, around the same time as Homer.M. L. West, ''Hesiod: Theogony'', Oxford University Press (1966), p. 40.Jasper Gr ...

,

Pythagoras

Pythagoras of Samos (; BC) was an ancient Ionian Greek philosopher, polymath, and the eponymous founder of Pythagoreanism. His political and religious teachings were well known in Magna Graecia and influenced the philosophies of P ...

,

Xenophanes

Xenophanes of Colophon ( ; ; – c. 478 BC) was a Greek philosopher, theologian, poet, and critic of Homer. He was born in Ionia and travelled throughout the Greek-speaking world in early classical antiquity.

As a poet, Xenophanes was known f ...

, and

Hecataeus. He endorsed the sage

Bias of Priene, who is quoted as saying "Most men are bad". He praised a man named Hermodorus as the best among the Ephesians, who he says should all

kill themselves for exiling him.

Heraclitus is traditionally considered to have

flourished in the 69th

Olympiad

An olympiad (, ''Olympiás'') is a period of four years, particularly those associated with the Ancient Olympic Games, ancient and Olympic Games, modern Olympic Games.

Although the ancient Olympics were established during Archaic Greece, Greece ...

(504–501 BC), but this date may simply be based on a prior account synchronizing his life with the reign of

Darius the Great

Darius I ( ; – 486 BCE), commonly known as Darius the Great, was the third King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 522 BCE until his death in 486 BCE. He ruled the empire at its territorial peak, when it included much of West A ...

. However, this date can be considered "roughly accurate" based on a fragment that references Pythagoras, Xenophanes, and Hecataeus as older contemporaries, placing him near the end of the sixth century BC.

According to Diogenes Laertius, Heraclitus died covered in dung after failing to cure himself from

dropsy. This may be to parody his doctrine that for souls it is death to become water, and that a dry soul is best.

''On Nature''

Heraclitus is said to have produced a single work on

papyrus

Papyrus ( ) is a material similar to thick paper that was used in ancient times as a writing surface. It was made from the pith of the papyrus plant, ''Cyperus papyrus'', a wetland sedge. ''Papyrus'' (plural: ''papyri'' or ''papyruses'') can a ...

, which has not survived; however, over 100 fragments of this work survive in quotations by other authors. The title is unknown, but many later writers refer to this work, and works by other pre-Socratics, as ''On Nature''. According to Diogenes Laërtius, Heraclitus deposited the book in the

Artemision as a dedication. It was available at least until the 2nd century AD, when

Plutarch

Plutarch (; , ''Ploútarchos'', ; – 120s) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo (Delphi), Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''Parallel Lives'', ...

and

Clement quote directly from it, if not later. Yet by the 6th-century,

Simplicius of Cilicia

Simplicius of Cilicia (; ; – c. 540) was a disciple of Ammonius Hermiae and Damascius, and was one of the last of the Neoplatonists. He was among the pagan philosophers persecuted by Justinian in the early 6th century, and was forced for ...

, who mentions Heraclitus 32 times in his

Commentaries on Aristotle, never quotes from him, implying that Heraclitus's work was so rare that it was apparently unavailable even to the

Neoplatonist

Neoplatonism is a version of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a series of thinkers. Among the common id ...

philosophers at the Platonic Academy in Athens.

The opening lines are quoted by

Sextus Empiricus

Sextus Empiricus (, ; ) was a Greek Pyrrhonist philosopher and Empiric school physician with Roman citizenship. His philosophical works are the most complete surviving account of ancient Greek and Roman Pyrrhonism, and because of the argument ...

:

Structure

Scholar

Martin Litchfield West

Martin Litchfield West, (23 September 1937 – 13 July 2015) was a British philologist and classical scholar. In recognition of his contribution to scholarship, he was appointed to the Order of Merit in 2014.

West wrote on ancient Greek music ...

claims that while the existing fragments do not give much of an idea of the overall structure, the beginning of the discourse can probably be determined.

Diogenes Laërtius wrote that the book was divided into three parts: the

universe

The universe is all of space and time and their contents. It comprises all of existence, any fundamental interaction, physical process and physical constant, and therefore all forms of matter and energy, and the structures they form, from s ...

,

politics

Politics () is the set of activities that are associated with decision-making, making decisions in social group, groups, or other forms of power (social and political), power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of Social sta ...

, and

theology

Theology is the study of religious belief from a Religion, religious perspective, with a focus on the nature of divinity. It is taught as an Discipline (academia), academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itse ...

, but, classicists have challenged that division. Classicist

John Burnet has argued that "it is not to be supposed that this division is due to

eraclitushimself; all we can infer is that the work fell naturally into these parts when the

Stoic commentators took their editions of it in hand". The Stoics divided their own philosophy into three parts: ethics, logic, and physics. The Stoic

Cleanthes

Cleanthes (; ; c. 330 BC – c. 230 BC), of Assos, was a Greek Stoic philosopher and boxer who was the successor to Zeno of Citium as the second head ('' scholarch'') of the Stoic school in Athens. Originally a boxer, he came to Athens where ...

further divided philosophy into

dialectic

Dialectic (; ), also known as the dialectical method, refers originally to dialogue between people holding different points of view about a subject but wishing to arrive at the truth through reasoned argument. Dialectic resembles debate, but the ...

s,

rhetoric

Rhetoric is the art of persuasion. It is one of the three ancient arts of discourse ( trivium) along with grammar and logic/ dialectic. As an academic discipline within the humanities, rhetoric aims to study the techniques that speakers or w ...

,

ethics

Ethics is the philosophy, philosophical study of Morality, moral phenomena. Also called moral philosophy, it investigates Normativity, normative questions about what people ought to do or which behavior is morally right. Its main branches inclu ...

, politics,

physics

Physics is the scientific study of matter, its Elementary particle, fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge whi ...

, and theology, and

philologist

Philology () is the study of language in oral and written historical sources. It is the intersection of textual criticism, literary criticism, history, and linguistics with strong ties to etymology. Philology is also defined as the study of ...

Karl Deichgräber has argued the last three are the same as the alleged division of Heraclitus.

[The Cynics](_blank)

by. Robert Brach Branham p. 51 The philosopher Paul Schuster has argued the division came from the ''

Pinakes''.

Style

Heraclitus's style has been compared to a

Sibyl

The sibyls were prophetesses or oracles in Ancient Greece.

The sibyls prophet, prophesied at holy sites.

A sibyl at Delphi has been dated to as early as the eleventh century BC by Pausanias (geographer), PausaniasPausanias 10.12.1 when he desc ...

,

[Nietzsche, Friedrich. ''Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the Greeks''. United States: Skyhorse Publishing. p. 64] who "with raving lips uttering things mirthless, unbedizened, and unperfumed, reaches over a thousand years with her voice, thanks to the god in her".

Heraclitus also seemed to pattern his style after

oracle

An oracle is a person or thing considered to provide insight, wise counsel or prophetic predictions, most notably including precognition of the future, inspired by deities. If done through occultic means, it is a form of divination.

Descript ...

s. Heraclitus wrote "nature loves to hide" and "a hidden connection is stronger than an obvious one". He also wrote "The lord whose

oracle

An oracle is a person or thing considered to provide insight, wise counsel or prophetic predictions, most notably including precognition of the future, inspired by deities. If done through occultic means, it is a form of divination.

Descript ...

is in

Delphi

Delphi (; ), in legend previously called Pytho (Πυθώ), was an ancient sacred precinct and the seat of Pythia, the major oracle who was consulted about important decisions throughout the ancient Classical antiquity, classical world. The A ...

neither speaks nor conceals, but gives a sign." Heraclitus is the earliest known literary reference for the

Delphic maxim to

know thyself.

Kahn characterized the main features of Heraclitus's writing as "linguistic density", meaning that single words and phrases have multiple meanings, and "resonance", meaning that expressions evoke one another. Heraclitus used

literary devices like

alliteration

Alliteration is the repetition of syllable-initial consonant sounds between nearby words, or of syllable-initial vowels if the syllables in question do not start with a consonant. It is often used as a literary device. A common example is " Pe ...

and

chiasmus

In rhetoric, chiasmus ( ) or, less commonly, chiasm (Latin term from Greek , "crossing", from the Ancient Greek, Greek , , "to shape like the letter chi (letter), Χ"), is a "reversal of grammatical structures in successive phrases or clauses ...

.

The Obscure

Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

quotes part of the opening line of Heraclitus's work in the ''

Rhetoric

Rhetoric is the art of persuasion. It is one of the three ancient arts of discourse ( trivium) along with grammar and logic/ dialectic. As an academic discipline within the humanities, rhetoric aims to study the techniques that speakers or w ...

'' to outline the difficulty in punctuating Heraclitus without ambiguity; he debated whether "forever" applied to "being" or to "prove". Aristotle's successor at the

lyceum

The lyceum is a category of educational institution defined within the education system of many countries, mainly in Europe. The definition varies among countries; usually it is a type of secondary school. Basic science and some introduction to ...

Theophrastus

Theophrastus (; ; c. 371 – c. 287 BC) was an ancient Greek Philosophy, philosopher and Natural history, naturalist. A native of Eresos in Lesbos, he was Aristotle's close colleague and successor as head of the Lyceum (classical), Lyceum, the ...

says about Heraclitus that "some parts of his work

rehalf-finished, while other parts

adea strange medley". Theophrastus thought an inability to finish the work showed Heraclitus was melancholic.

Diogenes Laërtius relays the story that the playwright

Euripides

Euripides () was a Greek tragedy, tragedian of classical Athens. Along with Aeschylus and Sophocles, he is one of the three ancient Greek tragedians for whom any plays have survived in full. Some ancient scholars attributed ninety-five plays to ...

gave

Socrates

Socrates (; ; – 399 BC) was a Ancient Greek philosophy, Greek philosopher from Classical Athens, Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and as among the first moral philosophers of the Ethics, ethical tradition ...

a copy of Heraclitus's work and asked for his opinion. Socrates replied: "The part I understand is excellent, and so too is, I dare say, the part I do not understand; but it needs a

Delian diver to get to the bottom of it."

Also according to Diogenes Laërtius, Timon of Phlius called Heraclitus "the Riddler" (; ). Timon said Heraclitus wrote his book "rather unclearly" (; ); according to Timon, this was intended to allow only the "capable" to attempt it.

By the time of the pseudo-Aristotelian treatise ''

De Mundo'', this epithet became in Greek "The Dark" (; ). In

Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

this became "The Obscure". According to

Cicero, Heraclitus had spoken ''nimis obscurē'' ("too obscurely") concerning nature and had done so deliberately in order to be misunderstood. According to

Plotinus

Plotinus (; , ''Plōtînos''; – 270 CE) was a Greek Platonist philosopher, born and raised in Roman Egypt. Plotinus is regarded by modern scholarship as the founder of Neoplatonism. His teacher was the self-taught philosopher Ammonius ...

, it was "probably with the idea that it is for us to seek within ourselves, as he sought for himself and found".

Philosophy

Heraclitus has been the subject of numerous interpretations. According to scholar Daniel W. Graham, Heraclitus has been seen as a "

material monist or a

process philosopher; a scientific

cosmologist, a

metaphysician and a religious thinker; an

empiricist, a

rationalist, a

mystic; a conventional thinker and a revolutionary; a developer of

logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the study of deductively valid inferences or logical truths. It examines how conclusions follow from premises based on the structure o ...

– one who denied the

law of non-contradiction; the first genuine philosopher and an

anti-intellectual obscurantist".

Unity of opposites and flux

The hallmarks of Heraclitus's philosophy are the

unity of

opposites and change, or

flux

Flux describes any effect that appears to pass or travel (whether it actually moves or not) through a surface or substance. Flux is a concept in applied mathematics and vector calculus which has many applications in physics. For transport phe ...

. According to Aristotle, Heraclitus was a

dialetheist, or one who denies the

law of noncontradiction (a

law of thought or logical principle which states that something cannot be true and false at the same time).

[ Also according to Aristotle, Heraclitus was a ]materialist

Materialism is a form of philosophical monism according to which matter is the fundamental substance in nature, and all things, including mental states and consciousness, are results of material interactions. According to philosophical materia ...

.[Aristotle. "M". ''Metaphysics'' 1078b] Attempting to follow Aristotle's hylomorphic interpretation, scholar W. K. C. Guthrie interprets the distinction between flux and stability as one between matter

In classical physics and general chemistry, matter is any substance that has mass and takes up space by having volume. All everyday objects that can be touched are ultimately composed of atoms, which are made up of interacting subatomic pa ...

and form. On this view, Heraclitus is a flux theorist because he is a materialist who believes matter always changes.circle

A circle is a shape consisting of all point (geometry), points in a plane (mathematics), plane that are at a given distance from a given point, the Centre (geometry), centre. The distance between any point of the circle and the centre is cal ...

's circumference, are common"; and "Thou shouldst unite things whole and things not whole, that which tends to unite and that which tends to separate, the harmonious and the discordant; from all things arises the one, and from the one all things."

Over time, the opposites change into each other: "Mortals are immortals and immortals are mortals, the one living the others' death and dying the others' life"; "As the same thing in us is living and dead, waking and sleeping, young and old. For these things having changed around are those, and those in turn having changed around are these"; and "Cold things warm up, the hot cools off, wet becomes dry, dry becomes wet."

It also seems they change into each other depending on one's point of view, a case of relativism

Relativism is a family of philosophical views which deny claims to absolute objectivity within a particular domain and assert that valuations in that domain are relative to the perspective of an observer or the context in which they are assess ...

or perspectivism. Heraclitus states: "Disease makes health sweet and good; hunger, satiety; toil, rest." While men drink and wash with water, fish

A fish (: fish or fishes) is an aquatic animal, aquatic, Anamniotes, anamniotic, gill-bearing vertebrate animal with swimming fish fin, fins and craniate, a hard skull, but lacking limb (anatomy), limbs with digit (anatomy), digits. Fish can ...

prefer to drink saltwater, pigs prefer to wash in mud, and fowl

Fowl are birds belonging to one of two biological orders, namely the gamefowl or landfowl ( Galliformes) and the waterfowl ( Anseriformes). Anatomical and molecular similarities suggest these two groups are close evolutionary relatives; toget ...

s prefer to wash in dust. " Oxen are happy when they find bitter vetches to eat" and " asses would rather have refuse than gold

Gold is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol Au (from Latin ) and atomic number 79. In its pure form, it is a brightness, bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile metal. Chemically, gold is a transition metal ...

."

''Panta rhei''

Diogenes Laërtius summarizes Heraclitus's philosophy as follows: "All things come into being by conflict of opposites, and the sum of things ( ''ta hola'' ('the whole')) flows like a stream." Classicist Jonathan Barnes states that "''Panta rhei'', 'everything flows' is probably the most familiar of Heraclitus's sayings, yet few modern scholars think he said it". Barnes observes that although the ''exact'' phrase was not ascribed to Heraclitus until the 6th century by Simplicius, a similar saying expressing the same idea, ''panta chorei'', or "everything moves" is ascribed to Heraclitus by Plato in the '' Cratylus''.

You cannot step into the same river twice

Since Plato, Heraclitus's theory of flux has been associated with the metaphor of a flowing river, which cannot be stepped into twice. This fragment from Heraclitus's writings has survived in three different forms:

* "On those who step into the same rivers, different and different waters flow" – Arius Didymus, quoted in Stobaeus

Joannes Stobaeus (; ; 5th-century AD), from Stobi in Macedonia (Roman province), Macedonia, was the compiler of a valuable series of extracts from Greek authors. The work was originally divided into two volumes containing two books each. The tw ...

* "We both step and do not step into the same river, we both are and are not" – Heraclitus Homericus, ''Homeric Allegories''

* "It is not possible to step into the same river twice" – Plutarch

Plutarch (; , ''Ploútarchos'', ; – 120s) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo (Delphi), Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''Parallel Lives'', ...

, ''On the E at Delphi''

The classicist Karl Reinhardt identified the first river quote as the genuine one. The river fragments (especially the second "we both are and are not") seem to suggest not only is the river constantly changing, but we do as well, perhaps commenting on existential questions about humanity and personhood.

Scholars such as Reinhardt also interpreted the metaphor as illustrating what is stable, rather than the usual interpretation of illustrating change. Classicist has said: "You will not find anything, in which the river remains constant ... Just the fact, that there is a particular river bed, that there is a source and an estuary etc. is something, that stays identical. And this is ... the concept of a river." According to American philosopher W. V. O. Quine, the river parable illustrates that the river is a process through time. One cannot step twice into the same river-stage.

Professor M. M. McCabe has argued that the three statements on rivers should all be read as fragments from a discourse. McCabe suggests reading them as though they arose in succession. The three fragments "could be retained, and arranged in an argumentative sequence". In McCabe's reading of the fragments, Heraclitus can be read as a philosopher capable of sustained argument

An argument is a series of sentences, statements, or propositions some of which are called premises and one is the conclusion. The purpose of an argument is to give reasons for one's conclusion via justification, explanation, and/or persu ...

, rather than just aphorism

An aphorism (from Greek ἀφορισμός: ''aphorismos'', denoting 'delimitation', 'distinction', and 'definition') is a concise, terse, laconic, or memorable expression of a general truth or principle. Aphorisms are often handed down by tra ...

.

Strife is justice

Heraclitus said "strife is justice" and "all things take place by strife". He called the opposites in conflict (), " strife", and theorized that the apparently unitary state, (), "

Heraclitus said "strife is justice" and "all things take place by strife". He called the opposites in conflict (), " strife", and theorized that the apparently unitary state, (), "justice

In its broadest sense, justice is the idea that individuals should be treated fairly. According to the ''Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy'', the most plausible candidate for a core definition comes from the ''Institutes (Justinian), Inst ...

", results in "the most beautiful harmony

In music, harmony is the concept of combining different sounds in order to create new, distinct musical ideas. Theories of harmony seek to describe or explain the effects created by distinct pitches or tones coinciding with one another; harm ...

", in contrast to Anaximander

Anaximander ( ; ''Anaximandros''; ) was a Pre-Socratic philosophy, pre-Socratic Ancient Greek philosophy, Greek philosopher who lived in Miletus,"Anaximander" in ''Chambers's Encyclopædia''. London: George Newnes Ltd, George Newnes, 1961, Vol. ...

, who described the same as injustice.[W. K. C. Guthrie "Pre-Socratic Philosophy" ''Cambridge Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' (1961) p. 443]

Heraclitus suggests that the world and its various parts are kept together through the tension produced by the unity of opposites, like the string of a bow or a lyre

The lyre () (from Greek λύρα and Latin ''lyra)'' is a string instrument, stringed musical instrument that is classified by Hornbostel–Sachs as a member of the History of lute-family instruments, lute family of instruments. In organology, a ...

. On one account, this is the earliest use of the concept of force

In physics, a force is an influence that can cause an Physical object, object to change its velocity unless counterbalanced by other forces. In mechanics, force makes ideas like 'pushing' or 'pulling' mathematically precise. Because the Magnitu ...

.[Cambridge Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Force, by M. Jammer (1961)] A quote about the bow shows his appreciation for wordplay: "The bow's name is life, but its work is death." Each substance contains its opposite, making for a continual circular exchange of generation, destruction, and motion that results in the stability of the world. This can be illustrated by the quote "Even the '' kykeon'' separates if it is not stirred."

According to Abraham Schoener: "War is the central principle in Heraclitus' thought." Another of Heraclitus's famous sayings highlights the idea that the unity of opposites is also a conflict of opposites: "War is father of all and king of all; and some he manifested as gods, some as men; some he made slaves, some free"; war is a creative tension that brings things into existence. Heraclitus says further "Gods and men honour those slain in war"; "Greater deaths gain greater portions"; and "Every beast is tended by blows."

''Logos''

A core concept for Heraclitus is ''

A core concept for Heraclitus is ''logos

''Logos'' (, ; ) is a term used in Western philosophy, psychology and rhetoric, as well as religion (notably Logos (Christianity), Christianity); among its connotations is that of a rationality, rational form of discourse that relies on inducti ...

'', an ancient Greek word literally meaning "word, speech, discourse, or meaning". For Heraclitus, the ''logos'' seems to designate the rational structure or ordered composition of the world.[Hoffman, David. (2006). Structural Logos in Heraclitus and the Sophists. Advances in the History of Rhetoric. 9. 1–32. .] As well as the opening quote of his book, one fragment reads: "Listening not to me but to the ''logos'', it is wise to agree (''homologein'') that all things are one." Another fragment reads: " 'hoi polloi''">hoi_polloi.html" ;"title="'hoi polloi">'hoi polloi''... do not know how to listen [to ''Logos''] or how to speak [the truth]."

The word ''logos'' has a wide variety of other uses, such that Heraclitus might have a different meaning of the word for each usage in his book. Kahn has argued that Heraclitus used the word in multiple senses, whereas Guthrie has argued that there is no evidence Heraclitus used it in a way that was significantly different from that in which it was used by contemporaneous speakers of Greek.

Professor Michael Stokes interprets Heraclitus's use of ''logos'' as a public fact

A fact is a truth, true data, datum about one or more aspects of a circumstance. Standard reference works are often used to Fact-checking, check facts. Science, Scientific facts are verified by repeatable careful observation or measurement by ...

like a proposition

A proposition is a statement that can be either true or false. It is a central concept in the philosophy of language, semantics, logic, and related fields. Propositions are the object s denoted by declarative sentences; for example, "The sky ...

or formula

In science, a formula is a concise way of expressing information symbolically, as in a mathematical formula or a ''chemical formula''. The informal use of the term ''formula'' in science refers to the general construct of a relationship betwe ...

; like Guthrie, he views Heraclitus as a materialist, so he grants Heraclitus would not have considered these as abstract objects

In philosophy and the arts, a fundamental distinction exists between abstract and concrete entities. While there is no universally accepted definition, common examples illustrate the difference: numbers, sets, and ideas are typically classified ...

or immaterial things. Another possibility is the ''logos'' referred to the truth

Truth or verity is the Property (philosophy), property of being in accord with fact or reality.Merriam-Webster's Online Dictionarytruth, 2005 In everyday language, it is typically ascribed to things that aim to represent reality or otherwise cor ...

, or to the book itself. Classicist Walther Kranz translated it as "sense

A sense is a biological system used by an organism for sensation, the process of gathering information about the surroundings through the detection of Stimulus (physiology), stimuli. Although, in some cultures, five human senses were traditio ...

".

Heraclitus's ''logos'' doctrine may also be the origin of the doctrine of natural law

Natural law (, ) is a Philosophy, philosophical and legal theory that posits the existence of a set of inherent laws derived from nature and universal moral principles, which are discoverable through reason. In ethics, natural law theory asserts ...

. Heraclitus stated "People ought to fight to keep their law as to defend the city walls. For all human laws get nourishment from the one divine law." "Far from arguing like the latter Sophists, that the human law, because it is a conventional law, deserves to be abandoned in favor of the law of nature, Herakleitos argued that the human law partakes of the law of nature, which is at the same time a divine law."

Fire as the ''arche''

The Milesians before Heraclitus had a view called

The Milesians before Heraclitus had a view called material monism

In philosophy and science, a first principle is a basic proposition or assumption that cannot be deduced from any other proposition or assumption. First principles in philosophy are from first cause attitudes and taught by Aristotelians, and nuan ...

which conceived of certain elements as the ''arche'' – Thales with water, Anaximander with ''apeiron'', and Anaximenes with air. Since antiquity, philosophers have concluded that Heraclitus construed of fire as the ''arche'', the ultimate reality or the fundamental element that gave rise to the other elements. Pre-Socratic scholar Eduard Zeller has argued that Heraclitus believed that heat in general and dry exhalation in particular, rather than visible fire, was the ''arche''.

In one fragment, Heraclitus writes:

This is the oldest extant quote using ''kosmos'', or order, to mean the world. Heraclitus seems to say fire is the one thing eternal in the universe. From fire all things originate and all things return again in a process of never-ending cycles. Plato and Aristotle attribute to Heraclitus a periodic destruction of the world by a great conflagration, known as ''ekpyrosis,'' which happens every Great Year

The term Great Year has multiple meanings. In scientific astronomy, it refers to the time required for the equinoxes to complete one full cycle around the ecliptic, a period of approximately 25,800 years. According to Ptolemy, his teacher Hipparc ...

– according to Plato, every 36,000 years.[Mondolfo, Rodolfo, and D. J. Allan. "Evidence of Plato and Aristotle Relating to the Ekpyrosis in Heraclitus." Phronesis, vol. 3, no. 2, 1958, pp. 75–82. . Accessed 30 May 2024.]

Heraclitus more than once describes the transformations to and from fire:

Fire as symbolic

However, it is also argued by many that Heraclitus never identified fire as the ''arche''; rather, he only used fire to explain his notion of flux, as the basic stuff which changes or moves the most. Others conclude he used it as the physical form of ''logos''.

On yet another interpretation, Heraclitus is not a material monist explicating flux nor stability, but a revolutionary process philosopher who chooses fire in an attempt to say there is no ''arche''. Fire is a symbol or metaphor for change, rather than the basic stuff which changes the most. Perspectives of this sort emphasize his statements on change such as "The way up is the way down", as well as the quote "All things are an exchange for Fire, and Fire for all things, even as wares for gold and gold for wares", which has been understood as stating that while all can be transformed into fire, not everything comes from fire, just as not everything comes from gold.

Cosmology

While considered an ancient cosmologist, Heraclitus did not seem as interested in astronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that studies celestial objects and the phenomena that occur in the cosmos. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and their overall evolution. Objects of interest includ ...

, meteorology

Meteorology is the scientific study of the Earth's atmosphere and short-term atmospheric phenomena (i.e. weather), with a focus on weather forecasting. It has applications in the military, aviation, energy production, transport, agricultur ...

, or mathematics

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

as his predecessors. It is surmised Heraclitus believed that the earth was flat and extended infinitely in all directions.

Heraclitus held all things occur according to fate

Destiny, sometimes also called fate (), is a predetermined course of events. It may be conceived as a predeterminism, predetermined future, whether in general or of an individual.

Fate

Although often used interchangeably, the words wiktionary ...

. He said "Time ('' Aion'') is a child playing draughts

Checkers (American English), also known as draughts (; Commonwealth English), is a group of strategy board games for two players which involve forward movements of uniform game pieces and mandatory captures by jumping over opponent pieces. ...

, the kingly power is a child's." It is disputed whether this means time and life is determined by rules

Rule or ruling may refer to:

Human activity

* The exercise of political or personal control by someone with authority or power

* Business rule, a rule pertaining to the structure or behavior internal to a business

* School rule, a rule tha ...

like a game

A game is a structured type of play usually undertaken for entertainment or fun, and sometimes used as an educational tool. Many games are also considered to be work (such as professional players of spectator sports or video games) or art ...

, by conflict like a game, or by arbitrary whims of the gods like a child plays.

Sun

Similar to his views on rivers, Heraclitus believed "the Sun

The Sun is the star at the centre of the Solar System. It is a massive, nearly perfect sphere of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core, radiating the energy from its surface mainly as visible light a ...

is new each day." He also said the Sun never sets. According to Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British philosopher, logician, mathematician, and public intellectual. He had influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, and various areas of analytic ...

, this was "obviously inspired by scientific reflection, and no doubt seemed to him to obviate the difficulty of understanding how the sun can work its way underground from west to east during the night".[ The physician ]Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus (; September 129 – AD), often Anglicization, anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Ancient Rome, Roman and Greeks, Greek physician, surgeon, and Philosophy, philosopher. Considered to be one o ...

explains: "Heraclitus says that the sun is a burning mass, kindled at its rising, and quenched at its setting."[Lewis, G. C. (1862). An Historical Survey of the Astronomy of the Ancients. Kiribati: Parker, Son, and Bourn. p. 96-97]

Heraclitus also believed that the Sun is as large as it looks, and said Hesiod "did not know night

Night, or nighttime, is the period of darkness when the Sun is below the horizon. Sunlight illuminates one side of the Earth, leaving the other in darkness. The opposite of nighttime is daytime. Earth's rotation causes the appearance of ...

and day

A day is the time rotation period, period of a full Earth's rotation, rotation of the Earth with respect to the Sun. On average, this is 24 hours (86,400 seconds). As a day passes at a given location it experiences morning, afternoon, evening, ...

, for they are one." However, he also explained the phenomenon of day and night by if the Sun "oversteps his measures", then "Erinyes

The Erinyes ( ; , ), also known as the Eumenides (, the "Gracious ones"), are chthonic goddesses of vengeance in ancient Greek religion and mythology. A formulaic oath in the ''Iliad'' invokes them as "the Erinyes, that under earth tak ...

, the ministers of Justice, will find him out". Heraclitus further wrote the Sun is in charge of the seasons.

Moon

On one account, Heraclitus believed the Sun and Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It Orbit of the Moon, orbits around Earth at Lunar distance, an average distance of (; about 30 times Earth diameter, Earth's diameter). The Moon rotation, rotates, with a rotation period (lunar ...

were bowl

A bowl is a typically round dish or container generally used for preparing, serving, storing, or consuming food. The interior of a bowl is characteristically shaped like a spherical cap, with the edges and the bottom, forming a seamless curve ...

s containing fire, with lunar phase

A lunar phase or Moon phase is the apparent shape of the Moon's directly sunlit portion as viewed from the Earth. Because the Moon is tidally locked with the Earth, the same hemisphere is always facing the Earth. In common usage, the four maj ...

s explained by the turning of the bowl.Oxyrhynchus Papyri

The Oxyrhynchus Papyri are a group of manuscripts discovered during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries by papyrology, papyrologists Bernard Pyne Grenfell and Arthur Surridge Hunt at an ancient Landfill, rubbish dump near Oxyrhync ...

, a group of manuscript

A manuscript (abbreviated MS for singular and MSS for plural) was, traditionally, any document written by hand or typewritten, as opposed to mechanically printed or reproduced in some indirect or automated way. More recently, the term has ...

s found in an ancient landfill

A landfill is a site for the disposal of waste materials. It is the oldest and most common form of waste disposal, although the systematic burial of waste with daily, intermediate and final covers only began in the 1940s. In the past, waste was ...

. This is the best evidence of Heraclitean astronomy.

God

Heraclitus said " thunderbolt steers all things", a rare comment on meteorology and likely a reference to

Heraclitus said " thunderbolt steers all things", a rare comment on meteorology and likely a reference to Zeus

Zeus (, ) is the chief deity of the List of Greek deities, Greek pantheon. He is a sky father, sky and thunder god in ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology, who rules as king of the gods on Mount Olympus.

Zeus is the child ...

as the supreme being. Even his theology proves contradictory: "One being, the only wise one, would and would not be called by the name of Zeus." He invokes relativism with the divine too: God sees man the same way man sees children and apes; and he seems to give a theodicy

In the philosophy of religion, a theodicy (; meaning 'vindication of God', from Ancient Greek θεός ''theos'', "god" and δίκη ''dikē'', "justice") is an argument that attempts to resolve the problem of evil that arises when all powe ...

, "for god all things are fair and good and just, but men suppose that some are unjust and others just". Yet another interpretation for Heraclitus's use of fire is it refers to the sun god, Apollo

Apollo is one of the Twelve Olympians, Olympian deities in Ancient Greek religion, ancient Greek and Ancient Roman religion, Roman religion and Greek mythology, Greek and Roman mythology. Apollo has been recognized as a god of archery, mu ...

;ethos

''Ethos'' is a Greek word meaning 'character' that is used to describe the guiding beliefs or ideals that characterize a community, nation, or ideology; and the balance between caution and passion. The Greeks also used this word to refer to the ...

'' means "character", while ''daimon

The daimon (), also spelled daemon (meaning "god", "godlike", "power", "fate"), denotes an "unknown superfactor", which can be either good or hostile.

In ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology a daimon was imagined to be a lesser ...

'' has various meanings, one of which being "the power controlling the destiny of individuals: hence, one's lot or fortune."

The Soul

Heraclitus believed the soul

The soul is the purported Mind–body dualism, immaterial aspect or essence of a Outline of life forms, living being. It is typically believed to be Immortality, immortal and to exist apart from the material world. The three main theories that ...

('' psyche'') was complex, stating: "The limits of the soul you could not discover, though traversing every path." Heraclitus regarded the soul as a mixture of fire and water, and believed that fire was the noble part of the soul and water the ignoble part. He considered mastery of one's worldly desires to be a noble pursuit that purified the soul's fire, while drunkenness

Alcohol intoxication, commonly described in higher doses as drunkenness or inebriation, and known in overdose as alcohol poisoning, is the behavior and physical effects caused by recent consumption of alcohol. The technical term ''intoxication ...

damages the soul by causing it to be moist. Heraclitus seems to advise against anger: "It is hard to fight with anger, for what it wants it buys at the price of the soul."

Heraclitus associates being awake with comprehension;mind

The mind is that which thinks, feels, perceives, imagines, remembers, and wills. It covers the totality of mental phenomena, including both conscious processes, through which an individual is aware of external and internal circumstances ...

and in sleep we become forgetful, but in waking we regain our sense

A sense is a biological system used by an organism for sensation, the process of gathering information about the surroundings through the detection of Stimulus (physiology), stimuli. Although, in some cultures, five human senses were traditio ...

s. For in sleep the passages of perception

Perception () is the organization, identification, and interpretation of sensory information in order to represent and understand the presented information or environment. All perception involves signals that go through the nervous syste ...

are shut, and hence the mind ... the only thing preserved is the connection through breathing

Breathing (spiration or ventilation) is the rhythmical process of moving air into ( inhalation) and out of ( exhalation) the lungs to facilitate gas exchange with the internal environment, mostly to flush out carbon dioxide and bring in oxy ...

." Heraclitus stated: "If all things should become smoke

Smoke is an aerosol (a suspension of airborne particulates and gases) emitted when a material undergoes combustion or pyrolysis, together with the quantity of air that is entrained or otherwise mixed into the mass. It is commonly an unwante ...

, then perception would be by the nostrils".

Heraclitus compares the soul to a spider

Spiders (order (biology), order Araneae) are air-breathing arthropods that have eight limbs, chelicerae with fangs generally able to inject venom, and spinnerets that extrude spider silk, silk. They are the largest order of arachnids and ran ...

and the body to the web

Web most often refers to:

* Spider web, a silken structure created by the animal

* World Wide Web or the Web, an Internet-based hypertext system

Web, WEB, or the Web may also refer to:

Computing

* WEB, a literate programming system created by ...

. Heraclitus believed the soul is what unifies the body and also what grants linguistic understanding, departing from Homer's conception of it as merely the breath of life.[Nussbaum, Martha C. "ΨΥΧΗ in Heraclitus, II." Phronesis, vol. 17, no. 2, 1972, pp. 153–170. . Accessed 18 June 2023.] Heraclitus ridicules Homer's conception of souls in the afterlife as shades by saying "Souls smell in Hades

Hades (; , , later ), in the ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology, is the god of the dead and the king of the Greek underworld, underworld, with which his name became synonymous. Hades was the eldest son of Cronus and Rhea ...

". His own views on the afterlife remain unclear, but Heraclitus did state: "There await men after they are dead things which they do not expect or imagine."

The Aristotelian tradition is responsible for a great part of the transmission of Heraclitus's physical conception of the soul. Aristotle wrote in '' De Anima'': "Heraclitus too says that the first principle—the 'warm exhalation' of which, according to him, everything else is composed—is soul; further, that this exhalation is most incorporeal and in ceaseless flux".

Foreign influence

Heraclitus's originality and placement near the beginning of Greek philosophy has resulted in several writers looking for possible influence from the surrounding nations.

Persia

The Persian Empire had a close connection with Ephesus and Zoroastrianism

Zoroastrianism ( ), also called Mazdayasnā () or Beh-dīn (), is an Iranian religions, Iranian religion centred on the Avesta and the teachings of Zoroaster, Zarathushtra Spitama, who is more commonly referred to by the Greek translation, ...

was the state religion of the Persian Empire. Heraclitus's emphasis on fire has been investigated for influence from Zoroastrian fire worship

Worship or deification of fire (also pyrodulia, pyrolatry or pyrolatria), or fire rituals, religious rituals centred on a fire, are known from various religions. Fire has been an important part of homo, human culture since the Lower Paleolithic. ...

and specifically the concept of '' Atar''. While many of the doctrines of Zoroastrian fire do not match exactly with those of Heraclitus, such as the relation of fire to earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to Planetary habitability, harbor life. This is enabled by Earth being an ocean world, the only one in the Solar System sustaining liquid surface water. Almost all ...

, it is still argued he may have taken some inspiration from them. Zoroastrian parallels to Heraclitus are often difficult to identify specifically due to a lack of surviving Zoroastrian literature from the period and mutual influence with Greek philosophy.

India

The interchange of other elements with fire has parallels in Vedic

upright=1.2, The Vedas are ancient Sanskrit texts of Hinduism. Above: A page from the '' Atharvaveda''.

The Vedas ( or ; ), sometimes collectively called the Veda, are a large body of religious texts originating in ancient India. Composed ...

literature from the same time period, such as the Upanishads

The Upanishads (; , , ) are late Vedic and post-Vedic Sanskrit texts that "document the transition from the archaic ritualism of the Veda into new religious ideas and institutions" and the emergence of the central religious concepts of Hind ...

. The ''Brihadaranyaka Upanishad

The ''Brihadaranyaka Upanishad'' (, ) is one of the Mukhya Upanishads, Principal Upanishads and one of the first Upanishadic scriptures of Hinduism. A key scripture to various schools of Hinduism, the ''Brihadaranyaka Upanisad'' is tenth in the ...

'' states that "Death is fire and the food of water" and the '' Taittiriya Upanishad'' states "from wind fire, from fire water, from water earth." Heraclitus may have also been influenced by a Vedic meditation

Meditation is a practice in which an individual uses a technique to train attention and awareness and detach from reflexive, "discursive thinking", achieving a mentally clear and emotionally calm and stable state, while not judging the meditat ...

known as the " Doctrine of the Five Fires." West however stresses that these doctrines of the interchange of elements were common throughout written works on philosophy that have survived from that period; so Heraclitus's doctrine of fire can not be definitively said to have been influenced by any other particular Iranian or Indian influence, but may have been part of a mutual interchange of influence over time across the Ancient Near East.

Egypt

Philosopher Gustav Teichmüller sought to prove Heraclitus was influenced by the Egyptians

Egyptians (, ; , ; ) are an ethnic group native to the Nile, Nile Valley in Egypt. Egyptian identity is closely tied to Geography of Egypt, geography. The population is concentrated in the Nile Valley, a small strip of cultivable land stretchi ...

,Horus

Horus (), also known as Heru, Har, Her, or Hor () in Egyptian language, Ancient Egyptian, is one of the most significant ancient Egyptian deities who served many functions, most notably as the god of kingship, healing, protection, the sun, and t ...

, as Ra of the sun, daily proceeded from Lotus the water." Paul Tannery took up Teichmüller's interpretation. They both thought Heraclitus's book was an offering to the temple to be read only by few initiates, rather than deposited in the temple to the public for safe-keeping. Edmund Pfleiderer argued that Heraclitus was influenced by the mystery cults. He interprets Heraclitus's apparent condemning of the mystery cults as the condemning of abuses rather than the idea itself.

Legacy

Heraclitus's writings have exerted a wide influence on Western philosophy

Western philosophy refers to the Philosophy, philosophical thought, traditions and works of the Western world. Historically, the term refers to the philosophical thinking of Western culture, beginning with the ancient Greek philosophy of the Pre ...

, including the works of Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

and Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

, who interpreted him in terms of their own doctrines.

His influence also extends into art, literature, and even medicine, as writings in the Hippocratic corpus

The Hippocratic Corpus (Latin: ''Corpus Hippocraticum''), or Hippocratic Collection, is a collection of around 60 early Ancient Greek medical works strongly associated with the physician Hippocrates and his teachings. The Hippocratic Corpus cov ...

show signs of Heraclitean themes. Heraclitus is also considered a potential source for understanding the Ancient Greek religion

Religious practices in ancient Greece encompassed a collection of beliefs, rituals, and Greek mythology, mythology, in the form of both popular public religion and Cult (religious practice), cult practices. The application of the modern concept ...

since the discovery of the Derveni papyrus, an Orphic poem which contains two fragments of Heraclitus.

Ancient

Pre-Socratics

It is unknown whether or not Heraclitus had any students in his lifetime. Diogenes Laertius states Heraclitus's book "won so great a fame that there arose followers of him called Heracliteans." Scholars took this to mean Heraclitus had no disciples and became renowned only after his death. According to one author, "The school of disciples founded by Heraclitus flourished for long after his death". According to another, "there were no doubt other Heracliteans whose names are now lost to us".

In his dialogue ''Cratylus'', Plato presented Cratylus as a Heraclitean and as a linguistic naturalist who believed that names must apply naturally to their objects. According to Aristotle, Cratylus went a step beyond his master's doctrine and said that one cannot step into the same river once. He took the view that nothing can be said about the ever-changing world and "ended by thinking that one need not say anything, and only moved his finger".

= Eleatics

=

Parmenides

Parmenides of Elea (; ; fl. late sixth or early fifth century BC) was a Pre-Socratic philosophy, pre-Socratic ancient Greece, Greek philosopher from Velia, Elea in Magna Graecia (Southern Italy).

Parmenides was born in the Greek colony of Veli ...

of Elea, a philosopher and near-contemporary, proposed a doctrine of changelessness, in contrast to the doctrine of flux put forth by Heraclitus. He is generally agreed to either have influenced or been influenced by Heraclitus. Different philosophers have argued that either one of them may have substantially influenced each other, some taking Heraclitus to be responding to Parmenides, but more often Parmenides is seen as responding to Heraclitus. Some also argue that any direct chain of influence between the two is impossible to determine. Although Heraclitus refers to older figures such as Pythagoras, neither Parmenides or Heraclitus refer to each other by name in any surviving fragments, so any speculation on influence must be based on interpretation.

= Pluralists and atomists

=

The surviving fragments of several other pre-Socratic philosophers show Heraclitean themes. Diogenes of Apollonia thought the action of one thing on another meant they were made of one substance. The pluralists may have been influenced by Heraclitus. The philosopher Anaxagoras

Anaxagoras (; , ''Anaxagóras'', 'lord of the assembly'; ) was a Pre-Socratic Greek philosopher. Born in Clazomenae at a time when Asia Minor was under the control of the Persian Empire, Anaxagoras came to Athens. In later life he was charged ...

refuses to separate the opposites in the "one cosmos". Empedocles

Empedocles (; ; , 444–443 BC) was a Ancient Greece, Greek pre-Socratic philosopher and a native citizen of Akragas, a Greek city in Sicily. Empedocles' philosophy is known best for originating the Cosmogony, cosmogonic theory of the four cla ...

has forces (arguably the first since Heraclitus's tension)

= Sophists

=

The sophists, including Protagoras of Abdera and Gorgias

Gorgias ( ; ; – ) was an ancient Greek sophist, pre-Socratic philosopher, and rhetorician who was a native of Leontinoi in Sicily. Several doxographers report that he was a pupil of Empedocles, although he would only have been a few years ...

of Leontini, may also have been influenced by Heraclitus. Sophists in general seemed to share Heraclitus's conception of the ''logos''. Heraclitus and others used "measure" to mean the balance and order of nature; hence Protagoras' famous statement "man is the measure of all things". In Plato's

Heraclitus and others used "measure" to mean the balance and order of nature; hence Protagoras' famous statement "man is the measure of all things". In Plato's dialogue

Dialogue (sometimes spelled dialog in American and British English spelling differences, American English) is a written or spoken conversational exchange between two or more people, and a literature, literary and theatrical form that depicts suc ...

'' Theaetetus'', Socrates sees Protagoras's "man is the measure" doctrine and Theaetetus' hypothesis that "knowledge is perception" as justified by Heraclitean flux.

Gorgias seems to have been influenced by the ''logos'', when he argued in his work ''On Non-Being'', possibly parodying the Eleatics, that being cannot exist or be communicated. According to one author, Gorgias "in a sense ... completes Heraclitus."[Rereading the Sophists by Susan Jarratt](_blank)

p. 44

Classical and Hellenistic philosophy

Plato knew of the teachings of Heraclitus through the Heraclitean philosopher Cratylus.[Sironi, Francesco, "Heraclitus in Verse: The Poetic Fragments of Scythinus of Teos," Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies 59 (2019): 551–57.] A four-volume work on Heraclitus was written by the academic Heraclides Ponticus

Heraclides Ponticus ( ''Herakleides''; c. 390 BC – c. 310 BC) was a Greek philosopher and astronomer who was born in Heraclea Pontica, now Karadeniz Ereğli, Turkey, and migrated to Athens. He is best remembered for proposing that the Earth ...

, but has not survived. Plutarch also wrote a lost treatise on Heraclitus. The Neoplatonists were influenced by Heraclitus on the topic of the One; quoting Plotinus

Plotinus (; , ''Plōtînos''; – 270 CE) was a Greek Platonist philosopher, born and raised in Roman Egypt. Plotinus is regarded by modern scholarship as the founder of Neoplatonism. His teacher was the self-taught philosopher Ammonius ...

"Heraclitus, with his sense of bodily forms as things of ceaseless process and passage, knows the One as eternal and intellectual."

Aristotle accused Heraclitus of denying the law of noncontradiction, and charges that he thereby failed in his reasoning. However, Aristotle's material monist and world conflagration (''ekpyrosis'') interpretation of Heraclitus influenced the Stoics.[

]

= Stoics

=

The Stoics believed major tenets of their philosophy derived from the thought of Heraclitus; especially the ''logos,'' used to support their belief that rational law governs the universe. Scholar A. A. Long concludes the earliest Stoic fragments are "modifications of Heraclitus". According to philosopher Philip Hallie

Philip Paul Hallie (1922–1994) was an author, philosopher and professor at Wesleyan University for 32 years. During World War II he served in the US Army. His degrees were from Harvard, Oxford (where he was a Fulbright Scholar at Jesus Colleg ...

, "Heraclitus of Ephesus was the father of Stoic physics

Stoicism is a school of Hellenistic philosophy that flourished in ancient Greece and Rome. The Stoics believed that the universe operated according to reason, ''i.e.'' by a God which is immersed in nature itself. Of all the schools of ancient ...

."

A four-volume work titled ''Interpretation of Heraclitus'' was written by the Stoic philosopher Cleanthes, but has not survived. In surviving stoic writings, Heraclitean influence is most evident in the writings of Marcus Aurelius

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus ( ; ; 26 April 121 – 17 March 180) was Roman emperor from 161 to 180 and a Stoicism, Stoic philosopher. He was a member of the Nerva–Antonine dynasty, the last of the rulers later known as the Five Good Emperors ...

. Marcus Aurelius understood the ''Logos'' as "the account which governs everything". Heraclitus also states, "We should not act and speak like children of our parents", which Marcus Aurelius interpreted to mean one should not simply accept what others believe.

Many of the later Stoics interpreted the ''logos'' as the ''arche'', as a creative fire that ran through all things due to sunlight;

= Cynics

=

The Cynics were influenced by Heraclitus, such as by his condemnation of the mystery cults.[ According to one source, "the Cynic affinity with Heraclitus lies not so much in his philosophy as in his cultural criticism and (idealised) lifestyle." The Cynics attributed several of the later Cynic epistles to his authorship.][J. F. Kindstrand, "The Cynics and Heraclitus", ''Eranos'' 82 (1984), 149–178] Heraclitus is sometimes even depicted as a cynic.

Heraclitus' idea that most people live as if in a deep state of sleep resembles what the Cynics said about a cloud of mist or fog shrouding all of existence.

Heraclitus wrote: "Dogs bark at every one they do not know." Similarly, Diogenes the Cynic

Diogenes the Cynic, also known as Diogenes of Sinope (c. 413/403–c. 324/321 BC), was an ancient Greek philosopher and one of the founders of Cynicism (philosophy), Cynicism. Renowned for his ascetic lifestyle, biting wit, and radical critique ...

, when asked by Alexander

Alexander () is a male name of Greek origin. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia who created one of the largest empires in ancient history.

Variants listed here ar ...

why he considered himself a dog, responded that he "barks at those who give me nothing".

= Pyrrhonists

=

The skeptical philosophers known as Pyrrhonists were also influenced by Heraclitus. He may be the predecessor to Pyrrho

Pyrrho of Elis (; ; ) was a Greek philosopher of Classical antiquity, credited as being the first Greek skeptic philosopher and founder of Pyrrhonism.

Life

Pyrrho of Elis is estimated to have lived from around 365/360 until 275/270 BCE. Py ...

's relativistic doctrine "No More This than That ", that nothing is one way rather than another way. According to Pyrrhonist Sextus Empiricus, Aenesidemus

Aenesidemus ( or Αἰνεσίδημος) was a 1st-century BC Greek Pyrrhonist philosopher from Knossos who revived the doctrines of Pyrrho and introduced ten skeptical "modes" (''tropai'') for the suspension of judgment. He broke with the Acad ...

, one of the major ancient Pyrrhonist philosophers, claimed in a now-lost work that Pyrrhonism was a way to Heraclitean philosophy because Pyrrhonist practice helps one to see how opposites appear to be the case about the same thing, leading to the Heraclitean view that opposites actually are true about the same thing.dogma

Dogma, in its broadest sense, is any belief held definitively and without the possibility of reform. It may be in the form of an official system of principles or doctrines of a religion, such as Judaism, Roman Catholicism, Protestantism, or Islam ...

of the Pyrrhonists but a matter occurring to the Pyrrhonists, to the other philosophers, and to all of humanity.Sextus Empiricus

Sextus Empiricus (, ; ) was a Greek Pyrrhonist philosopher and Empiric school physician with Roman citizenship. His philosophical works are the most complete surviving account of ancient Greek and Roman Pyrrhonism, and because of the argument ...

''Outlines of Pyrrhonism'' Book I, Chapter 29, Sections 210–211

Early Christianity

Hippolytus of Rome

Hippolytus of Rome ( , ; Romanized: , – ) was a Bishop of Rome and one of the most important second–third centuries Christian theologians, whose provenance, identity and corpus remain elusive to scholars and historians. Suggested communitie ...

, one of the early Church Fathers

The Church Fathers, Early Church Fathers, Christian Fathers, or Fathers of the Church were ancient and influential Christian theologians and writers who established the intellectual and doctrinal foundations of Christianity. The historical peri ...