Henry Ford on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Henry Ford (July 30, 1863 – April 7, 1947) was an American

In his farm workshop, Ford built a "steam wagon or tractor" and a steam car, but thought "steam was not suitable for light automobiles," as "the boiler was dangerous." Ford also said that he "did not see the use of experimenting with electricity, due to the expense of trolley wires, and "no storage battery was in sight of a weight that was practical." In 1885, Ford repaired an

In his farm workshop, Ford built a "steam wagon or tractor" and a steam car, but thought "steam was not suitable for light automobiles," as "the boiler was dangerous." Ford also said that he "did not see the use of experimenting with electricity, due to the expense of trolley wires, and "no storage battery was in sight of a weight that was practical." In 1885, Ford repaired an

"The Birth of Ford Motor Company"

, Henry Ford Heritage Association, retrieved August 20, 2012. Backed by the capital of Detroit

In response, Malcomson brought in another group of investors and convinced the Dodge brothers to accept a portion of the new company. Ford & Malcomson was reincorporated as the

In response, Malcomson brought in another group of investors and convinced the Dodge brothers to accept a portion of the new company. Ford & Malcomson was reincorporated as the

Ford created a huge publicity machine in Detroit to ensure every newspaper carried stories and ads about the new product. Ford's network of local dealers made the car ubiquitous in almost every city in North America. As independent dealers, the franchises grew rich and publicized not just the Ford but also the concept of car local

Ford created a huge publicity machine in Detroit to ensure every newspaper carried stories and ads about the new product. Ford's network of local dealers made the car ubiquitous in almost every city in North America. As independent dealers, the franchises grew rich and publicized not just the Ford but also the concept of car local

p. 72

Until the development of the assembly line, which mandated black because of its quicker drying time, Model Ts were available in other colors, including red. The design was fervently promoted and defended by Ford, and production continued as late as 1927; the final total production was 15,007,034. This record stood for the next 45 years, and was achieved in 19 years from the introduction of the first Model T (1908). Henry Ford turned the presidency of Ford Motor Company over to his son

Ford was a pioneer of "

Ford was a pioneer of "

pp. 126–30

It may have been

p. 130

p. 126

but in 1926 it was announced as five 8-hour days, giving a 40-hour week. The program apparently started with Saturday being designated a workday, before becoming a day off sometime later. On May 1, 1926, the Ford Motor Company's factory workers switched to a five-day, 40-hour workweek, with the company's office workers making the transition the following August. Ford had decided to boost productivity, as workers were expected to put more effort into their work in exchange for more leisure time. Ford also believed decent leisure time was good for business, giving workers additional time to purchase and consume more goods. However, charitable concerns also played a role. Ford explained, "It is high time to rid ourselves of the notion that leisure for workmen is either 'lost time' or a class privilege."

pp. 253–66

He thought they were too heavily influenced by leaders who would end up doing more harm than good for workers despite their ostensible good motives. Most wanted to restrict productivity as a means to foster employment, but Ford saw this as self-defeating because, in his view, productivity was necessary for economic prosperity to exist. He believed that productivity gains that obviated certain jobs would nevertheless stimulate the broader economy and grow new jobs elsewhere, whether within the same corporation or in others. Ford also believed that union leaders had a

Like other automobile companies, Ford entered the aviation business during

Like other automobile companies, Ford entered the aviation business during

"Michigan History: Willow Run and the Arsenal of Democracy."

''The Detroit News,'' January 28, 1997. Retrieved: August 7, 2010. Ford produced 9,000 B-24s at Willow Run, half of the 18,000 total B-24s produced during the war.

In Germany, Ford's ''The International Jew, the World's Foremost Problem'' was published by

In Germany, Ford's ''The International Jew, the World's Foremost Problem'' was published by  In July 1938, the German consul in Cleveland gave Ford, on his 75th birthday, the award of the Grand Cross of the German Eagle, the highest medal Nazi Germany could bestow on a foreigner. James D. Mooney, vice president of overseas operations for

In July 1938, the German consul in Cleveland gave Ford, on his 75th birthday, the award of the Grand Cross of the German Eagle, the highest medal Nazi Germany could bestow on a foreigner. James D. Mooney, vice president of overseas operations for

pp. 242–244

p. 50

Throughout the book, he continually returns to ideals such as transportation, production efficiency, affordability, reliability,

His health failing, Ford ceded the company presidency to his grandson

His health failing, Ford ceded the company presidency to his grandson

1865–67

Ford also had a long-standing interest in plastics developed from agricultural products, particularly

p. 281

) (at this time

pp. 275–276

and the potential uses of cotton. Ford was instrumental in developing charcoal briquets, under the brand name " Kingsford". His brother-in-law,

* In

* In

industrialist

A business magnate, also known as an industrialist or tycoon, is a person who is a powerful entrepreneur and investor who controls, through personal enterprise ownership or a dominant shareholding position, a firm or industry whose goods or ser ...

and business magnate

A business magnate, also known as an industrialist or tycoon, is a person who is a powerful entrepreneur and investor who controls, through personal enterprise ownership or a dominant shareholding position, a firm or industry whose goods or ser ...

. As the founder of the Ford Motor Company

Ford Motor Company (commonly known as Ford) is an American multinational corporation, multinational automobile manufacturer headquartered in Dearborn, Michigan, United States. It was founded by Henry Ford and incorporated on June 16, 1903. T ...

, he is credited as a pioneer in making automobile

A car, or an automobile, is a motor vehicle with wheels. Most definitions of cars state that they run primarily on roads, Car seat, seat one to eight people, have four wheels, and mainly transport private transport#Personal transport, peopl ...

s affordable for middle-class

The middle class refers to a class of people in the middle of a social hierarchy, often defined by occupation, income, education, or social status. The term has historically been associated with modernity, capitalism and political debate. Commo ...

Americans through the system that came to be known as Fordism

Fordism is an industrial engineering and manufacturing system that serves as the basis of modern social and labor-economic systems that support industrialized, standardized mass production and mass consumption. The concept is named after Henry ...

. In 1911, he was awarded a patent for the transmission mechanism that would be used in the Ford Model T

The Ford Model T is an automobile that was produced by the Ford Motor Company from October 1, 1908, to May 26, 1927. It is generally regarded as the first mass-affordable automobile, which made car travel available to middle-class Americans. Th ...

and other automobiles.

Ford was born in a farmhouse in Springwells Township, Michigan

Springwells Township is a defunct civil township in Wayne County, Michigan, Wayne County, in the U.S. state of Michigan. All of the land is now incorporated as part of the cities of Detroit and Dearborn, Michigan, Dearborn. Springwells is also f ...

, and left home at the age of 16 to find work in Detroit

Detroit ( , ) is the List of municipalities in Michigan, most populous city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is situated on the bank of the Detroit River across from Windsor, Ontario. It had a population of 639,111 at the 2020 United State ...

. It was a few years before this time that Ford first experienced automobiles, and throughout the later half of the 1880s, he began repairing and later constructing engines, and through the 1890s worked with a division of Edison Electric. He founded the Ford Motor Company in 1903 after prior failures in business, but success in constructing automobiles.

The introduction of the Ford Model T vehicle in 1908 is credited with having revolutionized both transportation and American industry. As the sole owner of the Ford Motor Company, Ford became one of the wealthiest people in the world. He was also among the pioneers of the five-day work-week. Ford believed that consumerism

Consumerism is a socio-cultural and economic phenomenon that is typical of industrialized societies. It is characterized by the continuous acquisition of goods and services in ever-increasing quantities. In contemporary consumer society, the ...

could help to bring about world peace

World peace is the concept of an ideal state of peace within and among all people and nations on Earth. Different cultures, religions, philosophies, and organizations have varying concepts on how such a state would come about.

Various relig ...

. His commitment to systematically lowering costs resulted in many technical and business innovations, including a franchise system, which allowed for car dealership

A car dealership, or car dealer, is a business that sells new or used cars, at the retail level, based on a dealership contract with an automaker or its sales subsidiary. Car dealerships also often sell spare parts and automotive maintena ...

s throughout North America and in major cities on six continents.

Ford was known for his pacifism during the first years of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, although during the war his company became a major supplier of weapons. He promoted the League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

. In the 1920s, Ford promoted antisemitism

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

through his newspaper '' The Dearborn Independent'' and the book ''The International Jew

''The International Jew'' is a four-volume set of antisemitic booklets or pamphlets originally published and distributed in the early 1920s by the Dearborn Publishing Company, an outlet owned by Henry Ford, the American industrialist and autom ...

.'' He opposed his country's entry into World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, and served for a time on the board of the America First Committee

The America First Committee (AFC) was an American isolationist pressure group against the United States' entry into World War II. Launched in September 1940, it surpassed 800,000 members in 450 chapters at its peak. The AFC principally supporte ...

. After his son Edsel

Edsel is a discontinued division and brand of automobiles that was produced by the Ford Motor Company in the 1958 to 1960 model years. Deriving its name from Edsel Ford, son of company founder Henry Ford, Edsels were developed in an effort to ...

died in 1943, Ford resumed control of the company, but was too frail to make decisions and quickly came under the control of several of his subordinates. He turned over the company to his grandson Henry Ford II

Henry Ford II (September 4, 1917 – September 29, 1987), commonly known as Hank the Deuce, was an American businessman in the automotive industry. He was the oldest son of Edsel Ford I and oldest grandson of Henry Ford. He served as president ...

in 1945. Upon his death in 1947, he left most of his wealth to the Ford Foundation

The Ford Foundation is an American private foundation with the stated goal of advancing human welfare. Created in 1936 by Edsel Ford and his father Henry Ford, it was originally funded by a $25,000 (about $550,000 in 2023) gift from Edsel Ford. ...

, and control of the company to his family.

Early life

Henry Ford was born July 30, 1863, on a farm inSpringwells Township, Michigan

Springwells Township is a defunct civil township in Wayne County, Michigan, Wayne County, in the U.S. state of Michigan. All of the land is now incorporated as part of the cities of Detroit and Dearborn, Michigan, Dearborn. Springwells is also f ...

. His father, William Ford (1826–1905), was born in County Cork

County Cork () is the largest and the southernmost Counties of Ireland, county of Republic of Ireland, Ireland, named after the city of Cork (city), Cork, the state's second-largest city. It is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Munster ...

, Ireland, to a family that had emigrated from Somerset

Somerset ( , ), Archaism, archaically Somersetshire ( , , ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by the Bristol Channel, Gloucestershire, and Bristol to the north, Wiltshire to the east ...

, England in the 16th century. His mother, Mary Ford (née Litogot; 1839–1876), was born in Michigan as the youngest child of Belgian immigrants; her parents died when she was a child and she was adopted by neighbors, the O'Herns. Henry Ford's siblings were John Ford (1865–1927); Margaret Ford (1867–1938); Jane Ford (); William Ford (1871–1917) and Robert Ford (1873–1877). Ford finished eighth grade at a one-room school

One-room schoolhouses, or One-room schools, have been commonplace throughout rural portions of various countries, including Prussia, Norway, Sweden, the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, Ireland, Portugal, and Spa ...

, Springwells Middle School. He never attended high school

A secondary school, high school, or senior school, is an institution that provides secondary education. Some secondary schools provide both ''lower secondary education'' (ages 11 to 14) and ''upper secondary education'' (ages 14 to 18), i.e., ...

; he later took a bookkeeping course at a commercial school.

His father gave him a pocket watch

A pocket watch is a watch that is made to be carried in a pocket, as opposed to a wristwatch, which is strapped to the wrist.

They were the most common type of watch from their development in the 16th century until wristwatches became popula ...

when he was 12. At 15, Ford dismantled and reassembled the timepieces of friends and neighbors dozens of times, gaining the reputation of a watch repairman. At twenty, Ford walked four miles to their Episcopal church every Sunday.

Ford said two significant events occurred in 1875 when he was 12: he received the watch, and he witnessed the operation of a Nichols and Shepard road engine, "...the first automobile other than horse-drawn that I had ever seen".

Ford was devastated when his mother died in 1876. His father expected him to take over the family farm eventually, but he despised farm work. He later wrote, "I never had any particular love for the farm—it was the mother on the farm I loved."

In 1879, Ford left home to work as an apprentice machinist

A machinist is a tradesperson or trained professional who operates machine tools, and has the ability to set up tools such as milling machines, grinders, lathes, and drilling machines.

A competent machinist will generally have a strong mechan ...

in Detroit, first with James F. Flower & Brothers, and later with the Detroit Dry Dock Company. In 1882, he returned to Dearborn to work on the family farm, where he became adept at operating the Westinghouse portable steam engine. He was later hired by Westinghouse to service their steam engines.

In his farm workshop, Ford built a "steam wagon or tractor" and a steam car, but thought "steam was not suitable for light automobiles," as "the boiler was dangerous." Ford also said that he "did not see the use of experimenting with electricity, due to the expense of trolley wires, and "no storage battery was in sight of a weight that was practical." In 1885, Ford repaired an

In his farm workshop, Ford built a "steam wagon or tractor" and a steam car, but thought "steam was not suitable for light automobiles," as "the boiler was dangerous." Ford also said that he "did not see the use of experimenting with electricity, due to the expense of trolley wires, and "no storage battery was in sight of a weight that was practical." In 1885, Ford repaired an Otto engine

The Otto engine is a large stationary single-cylinder internal combustion engine, internal combustion four-stroke engine, designed by the German Nicolaus Otto. It was a low-RPM machine, and only fired every other stroke due to the Otto cycle, a ...

, and in 1887 he built a four-cycle model with a one-inch bore and a three-inch stroke

Stroke is a medical condition in which poor cerebral circulation, blood flow to a part of the brain causes cell death. There are two main types of stroke: brain ischemia, ischemic, due to lack of blood flow, and intracranial hemorrhage, hemor ...

. In 1890, Ford started work on a two-cylinder

The engine configuration describes the fundamental operating principles by which internal combustion engines are categorized.

Piston engines are often categorized by their cylinder layout, valves and camshafts. Wankel engines are often categoriz ...

engine.

Ford said, "In 1892, I completed my first motor car, powered by a two-cylinder four horsepower

Horsepower (hp) is a unit of measurement of power, or the rate at which work is done, usually in reference to the output of engines or motors. There are many different standards and types of horsepower. Two common definitions used today are t ...

motor, with a two-and-half-inch bore and a six-inch stroke, which was connected to a countershaft by a belt and then to the rear wheel by a chain. The belt was shifted by a clutch lever to control speeds at 10 or 20 miles per hour

Miles per hour (mph, m.p.h., MPH, or mi/h) is a British imperial and United States customary unit of speed expressing the number of miles travelled in one hour. It is used in the United Kingdom, the United States, and a number of smaller count ...

, augmented by a throttle

A throttle is a mechanism by which fluid flow is managed by construction or obstruction.

An engine's power can be increased or decreased by the restriction of inlet gases (by the use of a throttle), but usually decreased. The term ''throttle'' ha ...

. Other features included 28-inch wire bicycle wheels with rubber tire

A tire (North American English) or tyre (Commonwealth English) is a ring-shaped component that surrounds a Rim (wheel), wheel's rim to transfer a vehicle's load from the axle through the wheel to the ground and to provide Traction (engineeri ...

s, a foot brake, a 3-gallon gasoline tank, and later, a water jacket around the cylinders for cooling. Ford added that "in the spring of 1893 the machine was running to my partial satisfaction and giving an opportunity further to test out the design and material on the road." Between 1895 and 1896, Ford drove that machine about 1000 miles. He then started a second car in 1896, eventually building three of them in his home workshop.

Marriage and family

Ford married Clara Jane Bryant (1866–1950) on April 11, 1888, and supported himself by farming and running asawmill

A sawmill (saw mill, saw-mill) or lumber mill is a facility where logging, logs are cut into lumber. Modern sawmills use a motorized saw to cut logs lengthwise to make long pieces, and crosswise to length depending on standard or custom sizes ...

. They had one child, Edsel Ford

Edsel Bryant Ford (November 6, 1893 – May 26, 1943) was an American business executive and philanthropist, who was the only child of pioneering industrialist Henry Ford and his wife, Clara Jane Bryant Ford. He was the president of Ford Motor C ...

(1893–1943).

Career

In 1891, Ford became anengineer

Engineers, as practitioners of engineering, are professionals who Invention, invent, design, build, maintain and test machines, complex systems, structures, gadgets and materials. They aim to fulfill functional objectives and requirements while ...

with the Edison Illuminating Company of Detroit. After his promotion to Chief Engineer in 1893, he had enough time and money to devote attention to his experiments on gasoline engines

Gasoline (North American English) or petrol (Commonwealth English) is a petrochemical product characterized as a transparent, yellowish, and flammable liquid normally used as a fuel for spark-ignited internal combustion engines. When formulate ...

. These experiments culminated in 1896 with the completion of a self-propelled automobiles, which he named the Ford Quadricycle. He test-drove it on June 4. After various test drives, Ford brainstormed ways to improve the Quadricycle.

Also in 1896, Ford attended a meeting of Edison executives, where he was introduced to Thomas Edison

Thomas Alva Edison (February11, 1847October18, 1931) was an American inventor and businessman. He developed many devices in fields such as electric power generation, mass communication, sound recording, and motion pictures. These inventions, ...

. Edison approved of Ford's automobile experimentation. Encouraged by Edison, Ford designed and built a second automobile, completing it in 1898.Ford R. Bryan"The Birth of Ford Motor Company"

, Henry Ford Heritage Association, retrieved August 20, 2012. Backed by the capital of Detroit

lumber baron

A business magnate, also known as an industrialist or tycoon, is a person who is a powerful entrepreneur and investor who controls, through personal enterprise ownership or a dominant shareholding position, a firm or industry whose goods or ser ...

William H. Murphy, Ford resigned from the Edison Company and founded the Detroit Automobile Company

The Detroit Automobile Company (DAC) was an early American automobile manufacturer founded on August 5, 1899, in Detroit, Michigan. It was the first venture of its kind in Detroit. Automotive mechanic Henry Ford attracted the financial backing ...

on August 5, 1899. However, the automobiles produced were of a lower quality and higher price than Ford wanted. Ultimately, the company was not successful and was dissolved in January 1901.

With the help of C. Harold Wills, Ford designed, built, and successfully raced a 26-horsepower

Horsepower (hp) is a unit of measurement of power, or the rate at which work is done, usually in reference to the output of engines or motors. There are many different standards and types of horsepower. Two common definitions used today are t ...

automobile in October 1901. With this success, Murphy and other stockholders in the Detroit Automobile Company formed the Henry Ford Company

The Henry Ford Company was an automobile manufacturer active from 1901 to 1902. Named after Henry Ford, it was his second company after the Detroit Automobile Company, which had been founded in 1899. The Henry Ford Company was founded November 1 ...

on November 30, 1901, with Ford as chief engineer. In 1902, Murphy brought in Henry M. Leland as a consultant; Ford, in response, left the company bearing his name. With Ford gone, Leland renamed the company the Cadillac Automobile Company.

Teaming up with former racing cyclist Tom Cooper, Ford also produced the 80+ horsepower racer "999 999 or triple nine most often refers to:

* 999 (emergency telephone number), a telephone number for the emergency services in several countries

* 999 (number), an integer

* AD 999, a year

* 999 BC, a year

Media

Books

* 999 (anthology), ''99 ...

," which Barney Oldfield

Berna Eli "Barney" Oldfield (January 29, 1878 – October 4, 1946) was a pioneer American racing driver. His name was "synonymous with speed in the first two decades of the 20th century". He was the winner of the inaugural List of American ope ...

was to drive to victory in a race in October 1902. Ford received the backing of an old acquaintance, Alexander Y. Malcomson, a Detroit-area coal dealer. They formed a partnership, Ford & Malcomson, Limited, to manufacture automobiles. Ford went to work designing an inexpensive automobiles, and the duo leased a factory and contracted with a machine shop owned by John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second E ...

and Horace E. Dodge to supply over $160,000 in parts. Sales were slow, and a crisis arose when the Dodge brothers demanded payment for their first shipment.

Ford Motor Company

In response, Malcomson brought in another group of investors and convinced the Dodge brothers to accept a portion of the new company. Ford & Malcomson was reincorporated as the

In response, Malcomson brought in another group of investors and convinced the Dodge brothers to accept a portion of the new company. Ford & Malcomson was reincorporated as the Ford Motor Company

Ford Motor Company (commonly known as Ford) is an American multinational corporation, multinational automobile manufacturer headquartered in Dearborn, Michigan, United States. It was founded by Henry Ford and incorporated on June 16, 1903. T ...

on June 16, 1903, with $28,000 capital. The original investors included Ford and Malcomson, the Dodge brothers, Malcomson's uncle John S. Gray, Malcolmson's secretary James Couzens

James Joseph Couzens (August 26, 1872October 22, 1936) was an American businessman, politician and philanthropist. He served as mayor of Detroit (1919–1922) and U.S. Senator from Michigan (1922–1936). Prior to entering politics he served as ...

, and two of Malcomson's lawyers, John W. Anderson and Horace Rackham

Horace Hatcher Rackham (June 27, 1858 – June 12, 1933) was one of the original stockholders in the Ford Motor Company and a noted philanthropist.

Early life

Rackham was born in Harrison Township, Michigan. He graduated from high school in Les ...

. Because of Ford's volatility, Gray was elected president of the company. Ford then demonstrated a newly designed car on the ice of Lake St. Clair

Lake St. Clair () is a freshwater lake that lies between the Canadian province of Ontario and the U.S. state of Michigan. It was named in 1679 by French Catholic explorers after Saint Clare of Assisi, on whose feast day they first saw the lake. ...

, driving in 39.4 seconds and setting a new land speed record

The land speed record (LSR) or absolute land speed record is the highest speed achieved by a person using a vehicle on land. By a 1964 agreement between the Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA) and Fédération Internationale de M ...

at . Convinced by this success, race driver Barney Oldfield

Berna Eli "Barney" Oldfield (January 29, 1878 – October 4, 1946) was a pioneer American racing driver. His name was "synonymous with speed in the first two decades of the 20th century". He was the winner of the inaugural List of American ope ...

, who named this new Ford model "999 999 or triple nine most often refers to:

* 999 (emergency telephone number), a telephone number for the emergency services in several countries

* 999 (number), an integer

* AD 999, a year

* 999 BC, a year

Media

Books

* 999 (anthology), ''99 ...

" in honor of the fastest locomotive

A locomotive is a rail transport, rail vehicle that provides the motive power for a train. Traditionally, locomotives pulled trains from the front. However, Push–pull train, push–pull operation has become common, and in the pursuit for ...

of the day, took the car around the country, making the Ford brand known throughout the United States. Ford also was one of the early backers of the Indianapolis 500

The Indianapolis 500, formally known as the Indianapolis 500-Mile Race, and commonly shortened to Indy 500, is an annual automobile race held at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway in Speedway, Indiana, United States, an enclave suburb of Indian ...

.

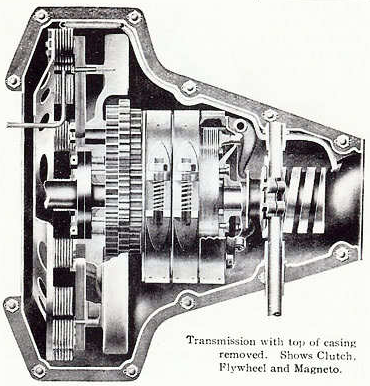

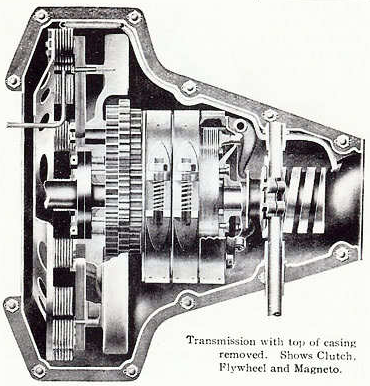

Transmission Patent

In 1909, Ford applied for a patent on his newtransmission

Transmission or transmit may refer to:

Science and technology

* Power transmission

** Electric power transmission

** Transmission (mechanical device), technology that allows controlled application of power

*** Automatic transmission

*** Manual tra ...

mechanism. It was awarded a patent in 1911.

Model T

TheModel T

The Ford Model T is an automobile that was produced by the Ford Motor Company from October 1, 1908, to May 26, 1927. It is generally regarded as the first mass-affordable automobile, which made car travel available to middle-class Americans. Th ...

debuted on October 1, 1908. It had the steering wheel

A steering wheel (also called a driving wheel, a hand wheel, or simply wheel) is a type of steering control in vehicles.

Steering wheels are used in most modern land vehicles, including all mass-production automobiles, buses, light and hea ...

on the left, which every other company soon copied. The entire engine and transmission

Transmission or transmit may refer to:

Science and technology

* Power transmission

** Electric power transmission

** Transmission (mechanical device), technology that allows controlled application of power

*** Automatic transmission

*** Manual tra ...

were enclosed; the four cylinders were cast in a solid block; the suspension used two semi-elliptic springs. The car was simple to drive, and easy and inexpensive to repair. It was so inexpensive at $825 in 1908 ($ today), with the price falling every year, that by the 1920s, a majority of American drivers had learned to drive on the Model T.

Ford created a huge publicity machine in Detroit to ensure every newspaper carried stories and ads about the new product. Ford's network of local dealers made the car ubiquitous in almost every city in North America. As independent dealers, the franchises grew rich and publicized not just the Ford but also the concept of car local

Ford created a huge publicity machine in Detroit to ensure every newspaper carried stories and ads about the new product. Ford's network of local dealers made the car ubiquitous in almost every city in North America. As independent dealers, the franchises grew rich and publicized not just the Ford but also the concept of car local motor club

An automobile association, also referred to as a motoring club, motoring association, or motor club, is an organization, either for-profit or non-profit, which motorists (drivers and vehicle owners) can join to enjoy benefits provided by the club ...

s sprang up to help new drivers and encourage them to explore the countryside. Ford was always eager to sell to farmers, who looked at the automobile as a commercial device to help their business. Sales skyrocketed—several years posted 100% gains on the previous year. In 1913, Ford introduced moving assembly belts into his plants, which enabled an enormous increase in production. Although Ford is often credited with the idea, contemporary sources indicate that the concept and development came from employees Clarence Avery, Peter E. Martin, Charles E. Sorensen, and C. Harold Wills. (See Ford Piquette Avenue Plant

The Ford Piquette Avenue Plant is a former factory located within the Milwaukee Junction area of Detroit, Michigan, in the United States. Built in 1904, it was the second center of automobile production for the Ford Motor Company, after the Fo ...

.)

Sales passed 250,000 in 1914. By 1916, as the price dropped to $360 for the basic touring car, sales reached 472,000.

By 1918, half of all cars in the United States were Model Ts. All new cars were black; as Ford wrote in his autobiography, "Any customer can have a car painted any color that he wants so long as it is black."p. 72

Until the development of the assembly line, which mandated black because of its quicker drying time, Model Ts were available in other colors, including red. The design was fervently promoted and defended by Ford, and production continued as late as 1927; the final total production was 15,007,034. This record stood for the next 45 years, and was achieved in 19 years from the introduction of the first Model T (1908). Henry Ford turned the presidency of Ford Motor Company over to his son

Edsel Ford

Edsel Bryant Ford (November 6, 1893 – May 26, 1943) was an American business executive and philanthropist, who was the only child of pioneering industrialist Henry Ford and his wife, Clara Jane Bryant Ford. He was the president of Ford Motor C ...

in December 1918. Henry retained final decision authority and sometimes reversed the decisions of his son. Ford started another company, Henry Ford and Son, and made a show of taking himself and his best employees to the new company; the goal was to scare the remaining holdout stockholders of the Ford Motor Company to sell their stakes to him before they lost most of their value. (He was determined to have full control over strategic decisions.) The ruse worked, and Henry and Edsel purchased all remaining stock from the other investors, thus giving the family sole ownership of the company.

In 1922, Ford also purchased Lincoln Motor Co., founded by Cadillac founder Henry Leland

Henry Martyn Leland (February 16, 1843 – March 26, 1932) was an American machinist, inventor, engineer, and automotive entrepreneur. He founded the two premier American luxury automotive marques, Cadillac and Lincoln.

Early years

Henry M. Le ...

and his son Wilfred during World War I. The Lelands briefly stayed to manage the company, but were soon expelled from it. Despite this acquisition of a premium car maker, Henry displayed relatively little enthusiasm for luxury automobiles in contrast to Edsel, who actively sought to expand Ford into the upscale market.. The original Lincoln Model L that the Lelands had introduced in 1920 was also kept in production, untouched for a decade until it became too outdated. It was replaced by the modernized Model K in 1931.

By the mid-1920s, General Motors

General Motors Company (GM) is an American Multinational corporation, multinational Automotive industry, automotive manufacturing company headquartered in Detroit, Michigan, United States. The company is most known for owning and manufacturing f ...

was rapidly rising as the leading American vehicle manufacturer. GM president Alfred Sloan

Alfred Pritchard Sloan Jr. ( ; May 23, 1875February 17, 1966) was an American business executive in the automotive industry. He was a longtime president, chairman and CEO of General Motors Corporation. First as a senior executive and later as t ...

established the company's "price ladder" whereby GM would offer an automobile for "every purse and purpose" in contrast to Ford's lack of interest in anything outside the low-end market. Although Henry Ford was against replacing the Model T, now 16 years old, Chevrolet was mounting a bold new challenge as GM's entry-level division in the company's price ladder. Ford also resisted the increasingly popular idea of payment plans for cars. With Model T sales starting to slide, Ford was forced to relent and approve work on a successor model, shutting down production for 18 months. During this time, Ford constructed a massive new assembly plant at River Rouge for the new Model A, which launched in 1927.

In addition to its price ladder, GM also quickly established itself at the forefront of automotive styling under Harley Earl

Harley Jarvis Earl (November 22, 1893 – April 10, 1969) was an American Automotive design, automotive designer and business executive. He was the initial designated head of design at General Motors, later becoming vice president, the first ...

's Arts & Color Department, another area of automobile design that Henry Ford did not entirely appreciate or understand. Ford would not have a true equivalent of the GM styling department for many years.

Model A and Ford's later career

By 1926, flagging sales of the Model T finally convinced Ford to make a new model. He pursued the project with a great deal of interest in the design of the engine, chassis, and other mechanical necessities, while leaving the body design to his son. Although Ford fancied himself an engineering genius, he had little formal training in mechanical engineering and could not even read a blueprint. A talented team of engineers performed most of the actual work of designing the Model A (and later the flathead V8) with Ford supervising them closely and giving them overall direction. Edsel also managed to prevail over his father's initial objections in the inclusion of a sliding-shift transmission.. The result was the Ford Model A, introduced in December 1927 and produced through 1931, with a total output of more than four million. Subsequently, the Ford company adopted an annual model change system similar to that recently pioneered by its competitor General Motors (and still in use by automobiles today). Not until the 1930s did Ford overcome his objection to finance companies, and the Ford-owned Universal Credit Corporation became a major car-financing operation. Henry Ford still resisted many technological innovations such as hydraulic brakes and all-metal roofs, which Ford automobiles did not adopt until 1935–1936. For 1932 however, Ford dropped a bombshell with the flathead Ford V8, the first low-price eight-cylinder engine. The flathead V8, variants of which were used in Ford automobiles for 20 years, was the result of a secret project launched in 1930 and Henry had initially considered a radical X-8 engine before agreeing to a conventional design. It gave Ford a reputation as a performance make well-suited for hot-rodding. Also, at Edsel's insistence, Ford launched Mercury in 1939 as a mid-range make to challenge Dodge and Buick, although Henry also displayed relatively little enthusiasm for it.Labor philosophy

=Five-dollar wage

= Ford was a pioneer of "

Ford was a pioneer of "welfare capitalism

Welfare capitalism is capitalism that includes social welfare policies and/or the practice of businesses providing welfare services to their employees. Welfare capitalism in this second sense, or industrial paternalism, was centered on indust ...

", designed to improve the lot of his workers and especially to reduce the heavy turnover that had many departments hiring 300 men per year to fill 100 slots. Efficiency meant hiring and keeping the best workers.

Ford astonished the world in 1914 by offering a $5 daily wage ($ in ), which more than doubled the rate of most of his workers. A Cleveland, Ohio

Cleveland is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County, Ohio, Cuyahoga County. Located along the southern shore of Lake Erie, it is situated across the Canada–United States border, Canada–U.S. maritime border ...

, newspaper editorialized that the announcement "shot like a blinding rocket through the dark clouds of the present industrial depression". The move proved extremely profitable; instead of constant employee turnover, the best mechanics in Detroit flocked to Ford, bringing their human capital

Human capital or human assets is a concept used by economists to designate personal attributes considered useful in the production process. It encompasses employee knowledge, skills, know-how, good health, and education. Human capital has a subs ...

and expertise, raising productivity, and lowering training costs. Ford announced his $5-per-day program on January 5, 1914, raising the minimum daily pay from $2.34 to $5 for qualifying male workers.

Detroit was already a high-wage city, but competitors were forced to raise wages or lose their best workers. Ford's policy proved that paying employees more would enable them to afford the cars they were producing and thus boost the local economy. He viewed the increased wages as profit-sharing linked with rewarding those who were most productive and of good character.pp. 126–30

It may have been

James Couzens

James Joseph Couzens (August 26, 1872October 22, 1936) was an American businessman, politician and philanthropist. He served as mayor of Detroit (1919–1922) and U.S. Senator from Michigan (1922–1936). Prior to entering politics he served as ...

who convinced Ford to adopt the $5-day wage.

Real profit-sharing was offered to employees who had worked at the company for six months or more, and, importantly, conducted their lives in a manner of which Ford's "Social Department" approved. They frowned on heavy drinking, gambling, and on what are now called deadbeat dads. The Social Department used 50 investigators and support staff to maintain employee standards; a large percentage of workers were able to qualify for this "profit-sharing".

Ford's incursion into his employees' private lives was highly controversial, and he soon backed off from the most intrusive aspects. By the time he wrote his 1922 memoir, he spoke of the Social Department and the private conditions for profit-sharing in the past tense. He admitted that "paternalism has no place in the industry. Welfare work that consists in prying into employees' private concerns is out of date. Men need counsel and men need help, often special help; and all this ought to be rendered for decency's sake. But the broad workable plan of investment and participation will do more to solidify the industry and strengthen the organization than will any social work on the outside. Without changing the principle we have changed the method of payment."p. 130

=Five-day workweek

= In addition to raising his workers' wages, Ford also introduced a new, reduced workweek in 1926. The decision was made in 1922, when Ford and Crowther described it as six 8-hour days, giving a 48-hour week,p. 126

but in 1926 it was announced as five 8-hour days, giving a 40-hour week. The program apparently started with Saturday being designated a workday, before becoming a day off sometime later. On May 1, 1926, the Ford Motor Company's factory workers switched to a five-day, 40-hour workweek, with the company's office workers making the transition the following August. Ford had decided to boost productivity, as workers were expected to put more effort into their work in exchange for more leisure time. Ford also believed decent leisure time was good for business, giving workers additional time to purchase and consume more goods. However, charitable concerns also played a role. Ford explained, "It is high time to rid ourselves of the notion that leisure for workmen is either 'lost time' or a class privilege."

=Labor unions

= Ford was adamantly againstlabor unions

A trade union (British English) or labor union (American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers whose purpose is to maintain or improve the conditions of their employment, such as attaining better wages ...

. He explained his views on unions in Chapter 18 of ''My Life and Work''.pp. 253–66

He thought they were too heavily influenced by leaders who would end up doing more harm than good for workers despite their ostensible good motives. Most wanted to restrict productivity as a means to foster employment, but Ford saw this as self-defeating because, in his view, productivity was necessary for economic prosperity to exist. He believed that productivity gains that obviated certain jobs would nevertheless stimulate the broader economy and grow new jobs elsewhere, whether within the same corporation or in others. Ford also believed that union leaders had a

perverse incentive

The phrase "perverse incentive" is often used in economics to describe an incentive structure with undesirable results, particularly when those effects are unexpected and contrary to the intentions of its designers.

The results of a perverse in ...

to foment perpetual socio-economic crises to maintain their power. Meanwhile, he believed that smart managers had an incentive to do right by their workers, because doing so would maximize their profits. However, Ford did acknowledge that many managers were basically too bad at managing to understand this fact. But Ford believed that eventually, if good managers such as he, could fend off the attacks of misguided people from both left and right (i.e., both socialists and bad-manager reactionaries), the good managers would create a socio-economic system wherein neither bad management nor bad unions could find enough support to continue existing.

To forestall union activity, Ford promoted Harry Bennett, a former Navy

A navy, naval force, military maritime fleet, war navy, or maritime force is the military branch, branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval warfare, naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral z ...

boxer, to head the Service Department. Bennett employed various intimidation tactics to quash union organizing. On March 7, 1932, during the Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

, unemployed Detroit auto workers staged the Ford Hunger March to the Ford River Rouge Complex

The Ford River Rouge complex (commonly known as the Rouge complex, River Rouge, or The Rouge) is a Ford Motor Company automobile factory complex located in Dearborn, Michigan, along the River Rouge (Michigan), River Rouge, upstream from its c ...

to present 14 demands to Henry Ford. The Dearborn police department and Ford security guards opened fire on workers leading to over sixty injuries and five deaths. On May 26, 1937, Bennett's security men beat members of the United Automobile Workers

The United Auto Workers (UAW), fully named International Union, United Automobile, Aerospace and Agricultural Implement Workers of America, is an American labor union that represents workers in the United States (including Puerto Rico) and sou ...

(UAW), including Walter Reuther

Walter Philip Reuther (; September 1, 1907 – May 9, 1970) was an American leader of organized labor and civil rights activist who built the United Automobile Workers (UAW) into one of the most progressive labor unions in American history. He ...

, with clubs. While Bennett's men were beating the UAW representatives, the supervising police chief on the scene was Carl Brooks, an alumnus of Bennett's Service Department, and Brooks "did not give orders to intervene".The following day photographs of the injured UAW members appeared in newspapers, later becoming known as The Battle of the Overpass

The Battle of the Overpass was an attack by Ford Motor Company against the United Auto Workers (UAW) on May 26, 1937, at the River Rouge complex in Dearborn, Michigan. The UAW had recently organized workers at Ford's competitors, and planned to ...

.

In the late 1930s and early 1940s, Edsel—who was president of the company—thought Ford had to come to a collective bargaining

Collective bargaining is a process of negotiation between employers and a group of employees aimed at agreements to regulate working salaries, working conditions, benefits, and other aspects of workers' compensation and labour rights, rights for ...

agreement with the unions because the violence, work disruptions, and bitter stalemates could not go on forever. But Ford, who still had the final veto in the company on a ''de facto'' basis even if not an official one, refused to cooperate. For several years, he kept Bennett in charge of talking to the unions trying to organize the Ford Motor Company. Sorensen's memoir. makes clear that Ford's purpose in putting Bennett in charge was to make sure no agreements were ever reached.

The Ford Motor Company was the last Detroit automaker to recognize the UAW, despite pressure from the rest of the U.S. automotive industry and even the U.S. government. A sit-down strike by the UAW union in April 1941 closed the River Rouge Plant

The Ford River Rouge complex (commonly known as the Rouge complex, River Rouge, or The Rouge) is a Ford Motor Company automobile factory complex located in Dearborn, Michigan, along the River Rouge, upstream from its confluence with the Detr ...

. Sorensen recounted. that a distraught Henry Ford was very close to following through with a threat to break up the company rather than cooperate. Still, his wife Clara told him she would leave him if he destroyed the family business. In her view, it would not be worth the chaos it would create. Ford complied with his wife's ultimatum and even agreed with her in retrospect.

Overnight, the Ford Motor Company went from the most stubborn holdout among automakers to the one with the most favorable UAW contract terms. The contract was signed in June 1941. About a year later, Ford told Walter Reuther, "It was one of the most sensible things Harry Bennett ever did when he got the UAW into this plant." Reuther inquired, "What do you mean?" Ford replied, "Well, you've been fighting General Motors and the Wall Street crowd. Now you're in here and we've given you a union shop and more than you got out of them. That puts you on our side, doesn't it? We can fight General Motors and Wall Street together, eh?"

Ford Airplane Company

Like other automobile companies, Ford entered the aviation business during

Like other automobile companies, Ford entered the aviation business during World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, building Liberty engines. After the war, it returned to auto manufacturing until 1925, when Ford acquired the Stout Metal Airplane Company.

Ford's most successful aircraft was the Ford 4AT Trimotor, often called the "Tin Goose" because of its corrugated metal construction. It used a new alloy called Alclad that combined the corrosion resistance of aluminum with the strength of duralumin

Duralumin (also called duraluminum, duraluminium, duralum, dural(l)ium, or dural) is a trade name for one of the earliest types of age hardening, age-hardenable aluminium–copper alloys. The term is a combination of ''Düren'' and ''aluminium'' ...

. The plane was similar to Fokker

Fokker (; ) was a Dutch aircraft manufacturer that operated from 1912 to 1996. The company was founded by the Dutch aviator Anthony Fokker and became famous during World War I for its fighter aircraft. During its most successful period in the 19 ...

's V.VII–3m. The Trimotor first flew on June 11, 1926, and was the first successful U.S. passenger airliner, accommodating about 12 passengers in a rather uncomfortable fashion. Several variants were also used by the U.S. Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of the United Stat ...

. The Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums, Education center, education and Research institute, research centers, created by the Federal government of the United States, U.S. government "for the increase a ...

has honored Ford for changing the aviation industry. 199 Trimotors were built before it was discontinued in 1933, when the Ford Airplane Division shut down because of poor sales during the Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

.

In 1985, Ford was posthumously inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame

The National Aviation Hall of Fame (NAHF) is a museum, annual awards ceremony and learning and research center that was founded in 1962 as an Ohio non-profit corporation in Dayton, Ohio, United States, known as the "Birthplace of Aviation" with ...

for his impact on the industry.

World War I era and peace activism

Ford opposed war, which he viewed as a terrible waste,Henry Ford, Biography (March 25, 1999). ''A&E Television''. and supported causes that opposedmilitary intervention

Interventionism, in international politics, is the interference of a state or group of states into the domestic affairs of another state for the purposes of coercing that state to do something or refrain from doing something. The intervention ca ...

. Ford became highly critical of those who he felt financed war, and he tried to stop them. In 1915, the pacifist Rosika Schwimmer

Rosika Schwimmer (; 11 September 1877 – 3 August 1948) was a Hungarian-born pacifist, feminist, world federalist and women's suffragist. A co-founder of the Campaign for World Government with Lola Maverick Lloyd, her radical vision of world ...

gained favor with Ford, who agreed to fund a Peace Ship to Europe, where World War I was raging. He led 170 other peace activists. Ford's Episcopalian pastor, Reverend Samuel S. Marquis, accompanied him on the mission. Marquis headed Ford's Sociology Department from 1913 to 1921. Ford talked to President Woodrow Wilson about the mission but had no government support. His group went to neutral Sweden and the Netherlands to meet with peace activists. A target of much ridicule, Ford left the ship as soon as it reached Sweden. In 1915, Ford blamed "German-Jewish bankers" for instigating the war.

According to biographer Steven Watts, Ford's status as a leading industrialist gave him a worldview that warfare was wasteful folly that retarded long-term economic growth. The losing side in the war typically suffered heavy damage. Small business were especially hurt, for it takes years to recuperate. He argued in many newspaper articles that a focus on business efficiency would discourage warfare because, "If every man who manufactures an article would make the very best he can in the very best way at the very lowest possible price the world would be kept out of war, for commercialists would not have to search for outside markets which the other fellow covets." Ford admitted that munitions makers enjoyed wars, but he argued that most businesses wanted to avoid wars and instead work to manufacture and sell useful goods, hire workers, and generate steady long-term profits.

Ford's British factories produced Fordson

Fordson was a brand name of tractors and trucks. It was used on a range of mass-produced general-purpose tractors manufactured by Henry Ford & Son Inc from 1917 to 1920, by Ford Motor Company (U.S.) and Ford Motor Company Ltd (U.K.) from 1920 ...

tractors to increase the British food supply, as well as trucks and warplane engines. When the U.S. entered the war in 1917, Ford went quiet on foreign policy. His company became a major supplier of weapons, especially the Liberty engine for warplanes and anti-submarine boats.

In 1918, with the war on and the League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

a growing issue in global politics, President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

, a Democrat, encouraged Ford to run for a Michigan seat in the U.S. Senate. Wilson believed that Ford could tip the scales in Congress in favor of Wilson's proposed League. "You are the only man in Michigan who can be elected and help bring about the peace you so desire," the president wrote Ford. Ford wrote back: "If they want to elect me let them do so, but I won't make a penny's investment." Ford did run, however, and came within 7,000 votes of winning, out of more than 400,000 cast statewide. He was defeated in a close election by the Republican candidate, Truman Newberry, a former United States Secretary of the Navy

The Secretary of the Navy (SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the United States Department of the Navy, Department of the Navy, a military department within the United States Department of Defense. On Mar ...

. Ford remained a staunch Wilsonian and supporter of the League. When Wilson made a major speaking tour in the summer of 1919 to promote the League, Ford helped fund the attendant publicity.

World War II era and controversies

Ford opposed the United States' entry into World War II and continued to believe that international business could generate the prosperity that would head off wars. Ford "insisted that war was the product of greedy financiers who sought profit in human destruction". In 1939, he went so far as to claim that the torpedoing of U.S. merchant ships by German submarines was the result of conspiratorial activities undertaken by financier war-makers. The financiers to whom he was referring was Ford's code for Jews; he had also accused Jews of fomenting the First World War. In the run-up to World War II and when the war erupted in 1939, he reported that he did not want to trade with belligerents. Like many other businessmen of the Great Depression era, he never liked or entirely trusted the Franklin Roosevelt Administration, and thought Roosevelt was inching the U.S. closer to war. Ford continued to do business withNazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

, including the manufacture of war materiel

Materiel or matériel (; ) is supplies, equipment, and weapons in military supply-chain management, and typically supplies and equipment in a commerce, commercial supply chain management, supply chain context.

Military

In a military context, ...

. However, he also agreed to build warplane engines for the British government. In early 1940, he boasted that Ford Motor Company would soon be able to produce 1,000 U.S. warplanes a day, even though it did not have an aircraft production facility at that time. Ford was a prominent early member of the America First Committee

The America First Committee (AFC) was an American isolationist pressure group against the United States' entry into World War II. Launched in September 1940, it surpassed 800,000 members in 450 chapters at its peak. The AFC principally supporte ...

against World War II involvement, but was forced to resign from its executive board when his involvement proved too controversial.

Beginning in 1940, with the requisitioning of between 100 and 200 French POWs

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of war for a ...

to work as slave laborers, '' Ford-Werke'' contravened Article 31 of the 1929 Geneva Convention

upright=1.15, The original document in single pages, 1864

The Geneva Conventions are international humanitarian laws consisting of four treaties and three additional protocols that establish international legal standards for humanitarian t ...

.

When Rolls-Royce

Rolls-Royce (always hyphenated) may refer to:

* Rolls-Royce Limited, a British manufacturer of cars and later aero engines, founded in 1906, now defunct

Automobiles

* Rolls-Royce Motor Cars, the current car manufacturing company incorporated in ...

sought a U.S. manufacturer as an additional source for the Merlin

The Multi-Element Radio Linked Interferometer Network (MERLIN) is an interferometer array of radio telescopes spread across England. The array is run from Jodrell Bank Observatory in Cheshire by the University of Manchester on behalf of UK Re ...

engine (as fitted to Spitfire

The Supermarine Spitfire is a British single-seat fighter aircraft that was used by the Royal Air Force and other Allied countries before, during, and after World War II. It was the only British fighter produced continuously throughout the ...

and Hurricane

A tropical cyclone is a rapidly rotating storm system with a low-pressure area, a closed low-level atmospheric circulation, strong winds, and a spiral arrangement of thunderstorms that produce heavy rain and squalls. Depending on its ...

fighters), Ford first agreed to do so and then reneged. He "lined up behind the war effort" when the U.S. entered in December 1941.

Willow Run

Before the U.S. entered the war, responding to President Roosevelt's call in December 1940 for the "Great Arsenal of Democracy", Ford directed theFord Motor Company

Ford Motor Company (commonly known as Ford) is an American multinational corporation, multinational automobile manufacturer headquartered in Dearborn, Michigan, United States. It was founded by Henry Ford and incorporated on June 16, 1903. T ...

to construct a vast new purpose-built aircraft factory at Willow Run

Willow Run, also known as Air Force Plant 31, was a manufacturing complex in Michigan, United States, located between Ypsilanti Township and Belleville, built by the Ford Motor Company to manufacture aircraft, especially the Consolidated B-24 ...

near Detroit, Michigan. Ford broke ground on Willow Run in the spring of 1941, B-24 component production began in May 1942, and the first complete B-24

The Consolidated B-24 Liberator is an American heavy bomber, designed by Consolidated Aircraft of San Diego, California. It was known within the company as the Model 32, and some initial production aircraft were laid down as export models desi ...

came off the assembly line in October 1942. At , it was the largest assembly line in the world at the time. At its peak in 1944, the Willow Run plant produced 650 B-24s per month, and by 1945 Ford was completing each B-24 in eighteen hours, with one rolling off the assembly line every 58 minutes.Nolan, Jenny"Michigan History: Willow Run and the Arsenal of Democracy."

''The Detroit News,'' January 28, 1997. Retrieved: August 7, 2010. Ford produced 9,000 B-24s at Willow Run, half of the 18,000 total B-24s produced during the war.

Edsel's death

When Edsel Ford died of cancer in 1943, at age 49, Henry Ford nominally resumed control of the company, but a series of strokes in the late 1930s had left him increasingly debilitated, and his mental ability was fading. Ford was increasingly sidelined, and others made decisions in his name. The company was controlled by a handful of senior executives led by Charles Sorensen, an important engineer and production executive at Ford; and Harry Bennett, the chief of Ford's Service Unit, Ford's paramilitary force that spied on, and enforced discipline upon, Ford employees. Ford grew jealous of the publicity Sorensen received and forced Sorensen out in 1944. Ford's incompetence led to discussions in Washington about how to restore the company, whether by wartime government fiat, or by instigating a coup among executives and directors..Forced out

Nothing happened until 1945 when, with bankruptcy a serious risk, Ford's wife Clara and Edsel's widow Eleanor confronted him and demanded he cede control of the company to his grandsonHenry Ford II

Henry Ford II (September 4, 1917 – September 29, 1987), commonly known as Hank the Deuce, was an American businessman in the automotive industry. He was the oldest son of Edsel Ford I and oldest grandson of Henry Ford. He served as president ...

. They threatened to sell off their stock, which amounted to three quarters of the company's total shares, if he refused. Ford was reportedly infuriated, but he had no choice but to give in. The young man took over and, as his first act of business, fired Harry Bennett.

Antisemitism and ''The Dearborn Independent''

Ford was aconspiracy theorist

A conspiracy theory is an explanation for an event or situation that asserts the existence of a conspiracy (generally by powerful sinister groups, often political in motivation), when other explanations are more probable.Additional sources:

*

...

who drew on a long tradition of false allegations against Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

. Ford claimed that Jewish internationalism posed a threat to traditional American values, which he deeply believed were at risk in the modern world. Part of his racist and antisemitic legacy includes the funding of square-dancing in American schools because he hated jazz

Jazz is a music genre that originated in the African-American communities of New Orleans, Louisiana, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Its roots are in blues, ragtime, European harmony, African rhythmic rituals, spirituals, h ...

and associated its creation with Jewish people. In 1920, Ford wrote, "If fans wish to know the trouble with American baseball they have it in three words—too much Jew." (citing the 2010 documentary film '' Jews and Baseball: An American Love Story'', by Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prizes () are 23 annual awards given by Columbia University in New York City for achievements in the United States in "journalism, arts and letters". They were established in 1917 by the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made his fo ...

winner Ira Berkow

Ira Berkow (born January 7, 1940) is an American sports reporter, columnist, and writer. He shared the 2001 Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, which was awarded to the staff of ''The New York Times'' for their serie''How Race Is Lived in Ame ...

).

In 1918, Ford purchased his hometown newspaper, '' The Dearborn Independent''. A year and a half later, Ford began publishing a series of articles in the paper under his own name, claiming a vast Jewish conspiracy was affecting America. The series ran in 91 issues. Every Ford dealership nationwide was required to carry the paper and distribute it to its customers. Ford later bound the articles into four volumes entitled ''The International Jew: The World's Foremost Problem'', which was translated into multiple languages and distributed widely across the US and Europe. ''The International Jew'' blamed nearly all the troubles it saw in American society on Jews. The ''Independent'' ran under Ford's ownership until its closure in 1927. With around 700,000 readers of his newspaper, Ford emerged as a "spokesman for right-wing extremism and religious prejudice."

In Germany, Ford's ''The International Jew, the World's Foremost Problem'' was published by

In Germany, Ford's ''The International Jew, the World's Foremost Problem'' was published by Theodor Fritsch

Theodor Fritsch (born Emil Theodor Fritsche; 28 October 1852 – 8 September 1933) was a German publisher and journalist. His antisemitic writings did much to influence popular German opinion against Jews in the late 19th and early 20th centur ...

, founder of several antisemitic parties and a member of the Reichstag, influencing German anti-Semitic discourse. In a letter written in 1924, Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler (; 7 October 1900 – 23 May 1945) was a German Nazism, Nazi politician and military leader who was the 4th of the (Protection Squadron; SS), a leading member of the Nazi Party, and one of the most powerful p ...

described Ford as "one of our most valuable, important, and witty fighters". Ford is the only American mentioned favorably in Hitler's autobiography ''Mein Kampf

(; ) is a 1925 Autobiography, autobiographical manifesto by Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler. The book outlines many of Political views of Adolf Hitler, Hitler's political beliefs, his political ideology and future plans for Nazi Germany, Ge ...

'', which appeared five years after Ford's anti-Semitic pamphlets were published in book form.

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

wrote, "only Ford, ho to he Jews'

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (letter), the fifth letter of the Semitic abjads

* He (pronoun), a pronoun in Modern English

* He (kana), one of the Japanese kana (へ in hiragana and ヘ in katakana)

* Ge (Cyrillic), a Cyrillic letter cal ...

fury, still maintains full independence ... rom

Rom, or ROM may refer to:

Biomechanics and medicine

* Risk of mortality, a medical classification to estimate the likelihood of death for a patient

* Rupture of membranes, a term used during pregnancy to describe a rupture of the amniotic sac

* ...

the controlling masters of the producers in a nation of one hundred and twenty millions." Speaking in 1931 to a ''Detroit News

''The Detroit News'' is one of the two major newspapers in the U.S. city of Detroit, Michigan. The paper began in 1873, when it rented space in the rival ''Detroit Free Press'' building. ''The News'' absorbed the ''Detroit Tribune'' on February ...

'' reporter, Hitler said "I regard Henry Ford as my inspiration," explaining his reason for keeping a life-size portrait of Ford behind his desk. Steven Watts wrote that Hitler "revered" Ford, proclaiming that "I shall do my best to put his theories into practice in Germany", and modeling the Volkswagen Beetle

The Volkswagen Beetle, officially the Volkswagen Type 1, is a small family car produced by the German company Volkswagen from 1938 to 2003. One of the most iconic cars in automotive history, the Beetle is noted for its distinctive shape. Its pr ...

, the people's car, on the Model T, which was designed by members of the Austrian-German Porsche

Dr. Ing. h.c. F. Porsche AG, usually shortened to Porsche (; see below), is a German automobile manufacturer specializing in luxury, high-performance sports cars, SUVs and sedans, headquartered in Stuttgart, Baden-Württemberg, Germany. Th ...

family of sportscar makers. Max Wallace has stated, "History records that ... Adolf Hitler was an ardent Anti-Semite before he ever read Ford's ''The International Jew''." Ford also paid to print and distribute 500,000 copies of the antisemitic fabricated text ''The Protocols of the Elders of Zion

''The Protocols of the Elders of Zion'' is a fabricated text purporting to detail a Jewish plot for global domination. Largely plagiarized from several earlier sources, it was first published in Imperial Russia in 1903, translated into multip ...

'' and is reported to have paid for the English translation of Hitler's ''Mein Kampf.'' Historians say Hitler distributed Ford's books and articles throughout Germany, stoking the hatred that helped fuel the Holocaust.

On February 1, 1924, Ford received Kurt Ludecke, a representative of Hitler, at home. Ludecke was introduced to Ford by Siegfried Wagner

Siegfried Helferich Richard Wagner (6 June 18694 August 1930) was a German composer and conductor, the son of Richard Wagner. He was an opera composer and the artistic director of the Bayreuth Festival from 1908 to 1930.

Life

Siegfried Wagner ...

(son of the composer Richard Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, essayist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most o ...

) and his wife Winifred, both Nazi

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During H ...

sympathizers and anti-Semites. Ludecke asked Ford for a contribution to the Nazi cause, but was apparently refused. Ford did, however, give considerable sums of money to Boris Brasol, a member of the Aufbau Vereinigung

The Wirtschaftliche Aufbau-Vereinigung (Economic Reconstruction Organization) was a Munich-based counterrevolutionary conspiratorial group formed in the aftermath of the German occupation of Ukraine in 1918 and of the Latvian Intervention of 19 ...

, an organization linking German Nazis and White Russian emigrants which financed the recently established Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party ( or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported the ideology of Nazism. Its precursor ...

.

Ford's articles were denounced by the Anti-Defamation League (ADL). While these articles explicitly condemned pogrom

A pogrom is a violent riot incited with the aim of Massacre, massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe late 19th- and early 20th-century Anti-Jewis ...

s and violence against Jews, they blamed the Jews themselves for provoking them. According to some trial testimony, none of this work was written by Ford, but he allowed his name to be used as an author. Friends and business associates said they warned Ford about the contents of the ''Independent'' and that he probably never read the articles (he claimed he only read the headlines). On the other hand, court testimony in a libel

Defamation is a communication that injures a third party's reputation and causes a legally redressable injury. The precise legal definition of defamation varies from country to country. It is not necessarily restricted to making assertions ...

suit, brought by one of the targets of the newspaper, alleged that Ford did know about the contents of the ''Independent'' in advance of publication.

A libel lawsuit was brought by San Francisco

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

lawyer

A lawyer is a person who is qualified to offer advice about the law, draft legal documents, or represent individuals in legal matters.

The exact nature of a lawyer's work varies depending on the legal jurisdiction and the legal system, as w ...

and Jewish farm cooperative organizer Aaron Sapiro

Aaron Leland Sapiro (February 5, 1884 – November 23, 1959) was a Jewish American cooperative activist and lawyer for the farmers' movement during the 1920s. He became notable for suing Henry Ford the auto-magnate for libel as a result of an ar ...

in response to the antisemitic remarks, and led Ford to close the ''Independent'' in December 1927. News reports at the time quoted him as saying he was shocked by the content and unaware of its nature. During the trial, the editor of Ford's "Own Page", William Cameron, testified that Ford had nothing to do with the editorials even though they were under his byline. Cameron testified at the libel trial that he never discussed the content of the pages or sent them to Ford for his approval. Investigative journalist Max Wallace noted that "whatever credibility this absurd claim may have had was soon undermined when James M. Miller, a former ''Dearborn Independent'' employee, swore under oath that Ford had told him he intended to expose Sapiro."

Michael Barkun

__NOTOC__

Michael Barkun (born April 8, 1938) is an American academic who serves as Professor Emeritus of political science at the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs, Syracuse University, specializing in political and religious ex ...