Helgoland Insel Düne 2190-Pano on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Heligoland (; , ; Heligolandic Frisian: , , Mooring Frisian: , ) is a small

Online ''Heiliges Land – Helgoland und seine früheren Namen''.

In: Uwe Ludwig, Thomas Schilp (eds.): ''Nomen et fraternitas. Festschrift für Dieter Geuenich zum 65. Geburtstag'' (Supplementary volumes to the ''Reallexikon des Germanischen Altertums''). De Gruyter, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-11-020238-0, p. 480. The discussion is complicated by a disagreement as to which of the listed names really refers to the island of Helgoland, and by a desire for the island still to be seen as holy today.

Heligoland is located off the German coastline and consists of two islands: the populated triangular main island () to the west, and the ('dune', Heligolandic: ) to the east. ''Heligoland'' generally refers to the former island. is somewhat smaller at , lower, and surrounded by sand beaches. It is not permanently inhabited, but is today the location of Heligoland's

Heligoland is located off the German coastline and consists of two islands: the populated triangular main island () to the west, and the ('dune', Heligolandic: ) to the east. ''Heligoland'' generally refers to the former island. is somewhat smaller at , lower, and surrounded by sand beaches. It is not permanently inhabited, but is today the location of Heligoland's

The German Bight and the area around the island are known to have been inhabited since prehistoric times.

The German Bight and the area around the island are known to have been inhabited since prehistoric times.

On 11 September 1807, during the

On 11 September 1807, during the  As related in ''

As related in ''

auf spurensuche-kreis-pinneberg.de On 3 December 1939, Heligoland was directly bombed by the

''1939 Dezember''

(Württemberg State Library, Stuttgart). Retrieved 4 July 2015. In three days in 1940, the

''Unter den Wellen Teil 3 – Britische U-Boote vor Helgoland''

. February 2013. Early in the war, the island was generally unaffected by bombing raids. Through the development of the

''Im Schutz der roten Felsen – Bunker auf Helgoland''

vom 19. April 2005, auf fr-online.de The bomb attacks rendered the island unsafe, and it was totally evacuated.

Heligoland, like the small exclave

Heligoland, like the small exclave

The island of Heligoland is a geological oddity; the presence of the main island's characteristic red

The island of Heligoland is a geological oddity; the presence of the main island's characteristic red

The Heligoland flag is very similar to its

The Heligoland flag is very similar to its

A special section in the German traffic regulations (''Straßenverkehrsordnung'', abbr. ''StVO''), §50, prohibits the use of automobiles and bicycles on the island.

The island received its first police car on 17 January 2006; until then the island's policemen moved on foot and by bicycle, being exempt from the bicycle ban.

A special section in the German traffic regulations (''Straßenverkehrsordnung'', abbr. ''StVO''), §50, prohibits the use of automobiles and bicycles on the island.

The island received its first police car on 17 January 2006; until then the island's policemen moved on foot and by bicycle, being exempt from the bicycle ban.

* Peter Andresen Oelrichs (1781–1869), a lexicographer and linguist.

*

* Peter Andresen Oelrichs (1781–1869), a lexicographer and linguist.

*

Film clip of coast defenses

Heligoland Tourist Board

– includes a virtual tour of the island.

Heligoland Bird Observatory

Footage of Destruction of Heligoland fortifications April 1947

{{Authority control Archipelagoes of Germany Landforms of Schleswig-Holstein Special territories of the European Union Former British colonies and protectorates in Europe Car-free islands of Europe Germany–United Kingdom relations Pinneberg (district) Frisian Islands 1807 establishments in the British Empire 1890 disestablishments in the British Empire Special economic zones Duty-free zones of Europe Tax avoidance

archipelago

An archipelago ( ), sometimes called an island group or island chain, is a chain, cluster, or collection of islands. An archipelago may be in an ocean, a sea, or a smaller body of water. Example archipelagos include the Aegean Islands (the o ...

in the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Denmark, Norway, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. A sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian Se ...

. The islands were historically possessions of Denmark

Denmark is a Nordic countries, Nordic country in Northern Europe. It is the metropole and most populous constituent of the Kingdom of Denmark,, . also known as the Danish Realm, a constitutionally unitary state that includes the Autonomous a ...

, then became possessions of the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

from 1807 to 1890. Since 1890, they have been part of the German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

state of Schleswig-Holstein

Schleswig-Holstein (; ; ; ; ; occasionally in English ''Sleswick-Holsatia'') is the Northern Germany, northernmost of the 16 states of Germany, comprising most of the historical Duchy of Holstein and the southern part of the former Duchy of S ...

, although they were managed by the United Kingdom as a war prize from 1945 to 1952.

The islands are located in the Heligoland Bight

The Heligoland Bight, also known as Helgoland Bight, (, ) is a bay which forms the southern part of the German Bight, itself a bay of the North Sea, located at the mouth of the Elbe river. The Heligoland Bight extends from the mouth of the Elb ...

(part of the German Bight

The German Bight ( ; ; ); ; ; sometimes also the German Bay) is the southeastern bight of the North Sea bounded by the Netherlands and Germany to the south, and Denmark and Germany to the east (the Jutland peninsula). To the north and west i ...

) in the southeastern corner of the North Sea and had a population of 1,127 at the end of 2016. They are the only German islands not in the vicinity of the mainland. They lie approximately by sea from Cuxhaven

Cuxhaven (; ) is a town and seat of the Cuxhaven district, in Lower Saxony, Germany. The town includes the northernmost point of Lower Saxony. It is situated on the shore of the North Sea at the mouth of the Elbe River. Cuxhaven has a footprint o ...

at the mouth of the River Elbe

The Elbe ( ; ; or ''Elv''; Upper Sorbian, Upper and , ) is one of the major rivers of Central Europe. It rises in the Giant Mountains of the northern Czech Republic before traversing much of Bohemia (western half of the Czech Republic), then Ge ...

.

In addition to German, the local population, who are ethnic Frisians

The Frisians () are an ethnic group indigenous to the German Bight, coastal regions of the Netherlands, north-western Germany and southern Denmark. They inhabit an area known as Frisia and are concentrated in the Dutch provinces of Friesland an ...

, speak the Heligolandic

Heligolandic (''Halunder'') is the dialect of the North Frisian language spoken on the German island of Heligoland in the North Sea. It is spoken today by some 500 of the island's 1,650 inhabitants and is also taught in schools. Heligolandic is ...

dialect of the North Frisian language

North Frisian is a minority language of Germany, spoken by about 10,000 people in North Frisia. The language is part of the larger group of the West Germanic Frisian languages. The language comprises 10 dialects which are themselves divided in ...

called .

During a visit to the islands in 1841, August Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben

August Heinrich Hoffmann (, calling himself von Fallersleben, after his hometown; 2 April 179819 January 1874) was a German poet. He is best known for writing "", whose third stanza is now the national anthem of Germany, and a number of popular ...

wrote the lyrics to the "", which became the national anthem of Germany.

Name

The island had no distinct name before the 19th century. It was often referred to by variants of theHigh German

The High German languages (, i.e. ''High German dialects''), or simply High German ( ) – not to be confused with Standard High German which is commonly also called "High German" – comprise the varieties of German spoken south of the Ben ...

''Heiligland'' ('holy land') and once even as the island of the Holy Virgin Ursula. Theodor Siebs

Theodor Siebs (; 26 August 1862 – 28 May 1941) was a German linguist most remembered today as the author of '' Deutsche Bühnenaussprache'' ('German stage pronunciation'), published in 1898. The work was largely responsible for setting the st ...

summarised the critical discussion of the name in the 19th century in 1909 with the thesis that, based on the Frisian self-designation of the Heligolanders as ''Halunder'', the island name meant 'high land' (similar to Hallig

The ''Halligen'' (German, singular ''Hallig'', ) or the ''halliger'' (Danish, singular ''hallig'') are small islands without protective dikes. They are variously pluralized in English as the Halligen, Halligs, Hallig islands, or Halligen islands ...

). In the following discussion by Jürgen Spanuth, Wolfgang Laur again proposed the original name of ''Heiligland''. The variant ''Helgoland'', which has appeared since the 16th century, is said to have been created by scholars who Latinized a North Frisian form ''Helgeland'', using it to refer to a legendary hero, Helgi

Helge or Helgi is a Scandinavian, German, and Dutch mostly male name.

The name is derived from Proto-Norse ''Hailaga'' with its original meaning being ''dedicated to the gods''. For its Slavic version, see Oleg. Its feminine equivalent is Olga ...

.

''Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde,'' Vol. 14, Artikel ''Helgoland.'' Berlin 1999.

For example, in Heike Grahn-HoekOnline ''Heiliges Land – Helgoland und seine früheren Namen''.

In: Uwe Ludwig, Thomas Schilp (eds.): ''Nomen et fraternitas. Festschrift für Dieter Geuenich zum 65. Geburtstag'' (Supplementary volumes to the ''Reallexikon des Germanischen Altertums''). De Gruyter, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-11-020238-0, p. 480. The discussion is complicated by a disagreement as to which of the listed names really refers to the island of Helgoland, and by a desire for the island still to be seen as holy today.

Geography

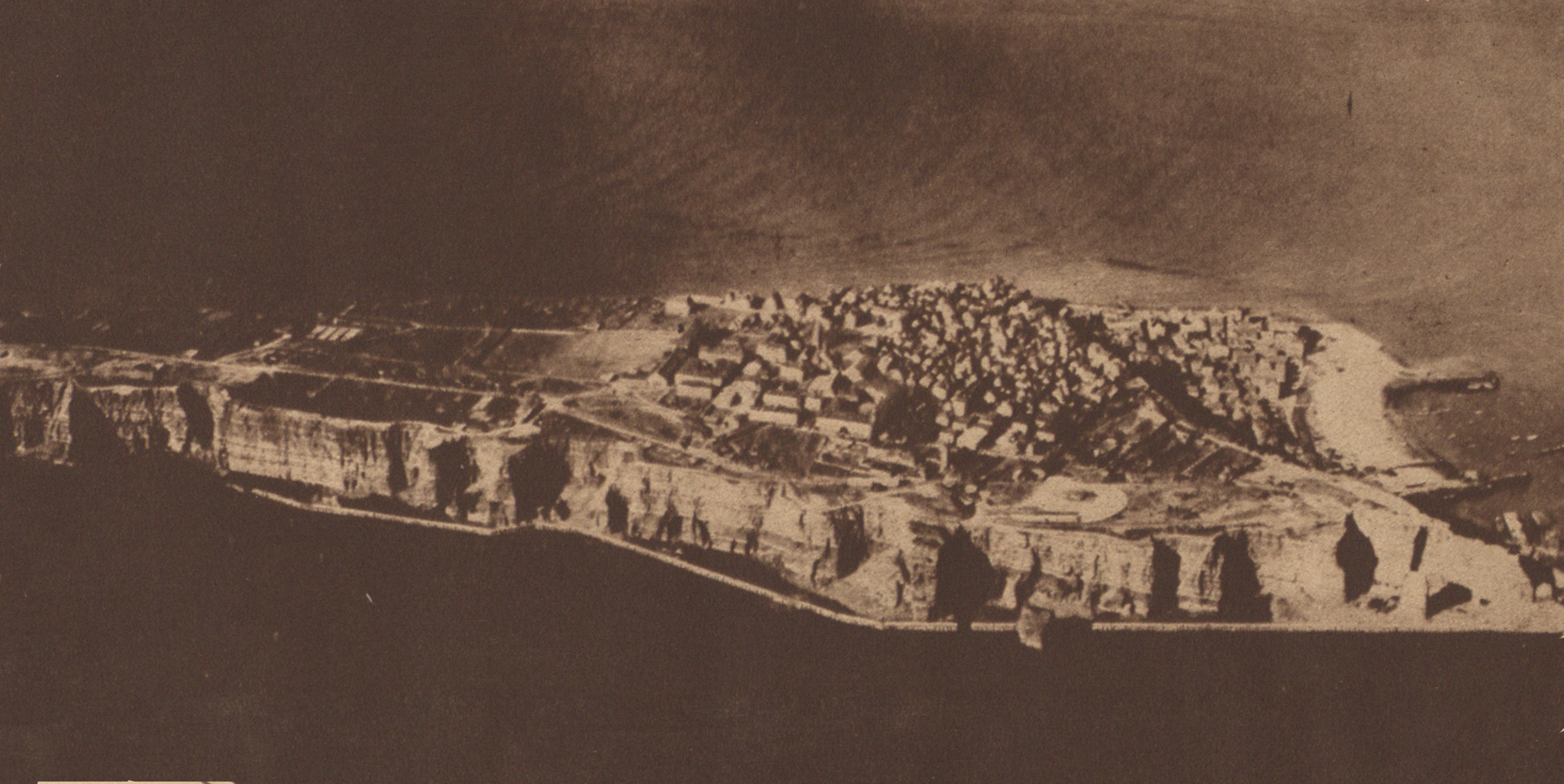

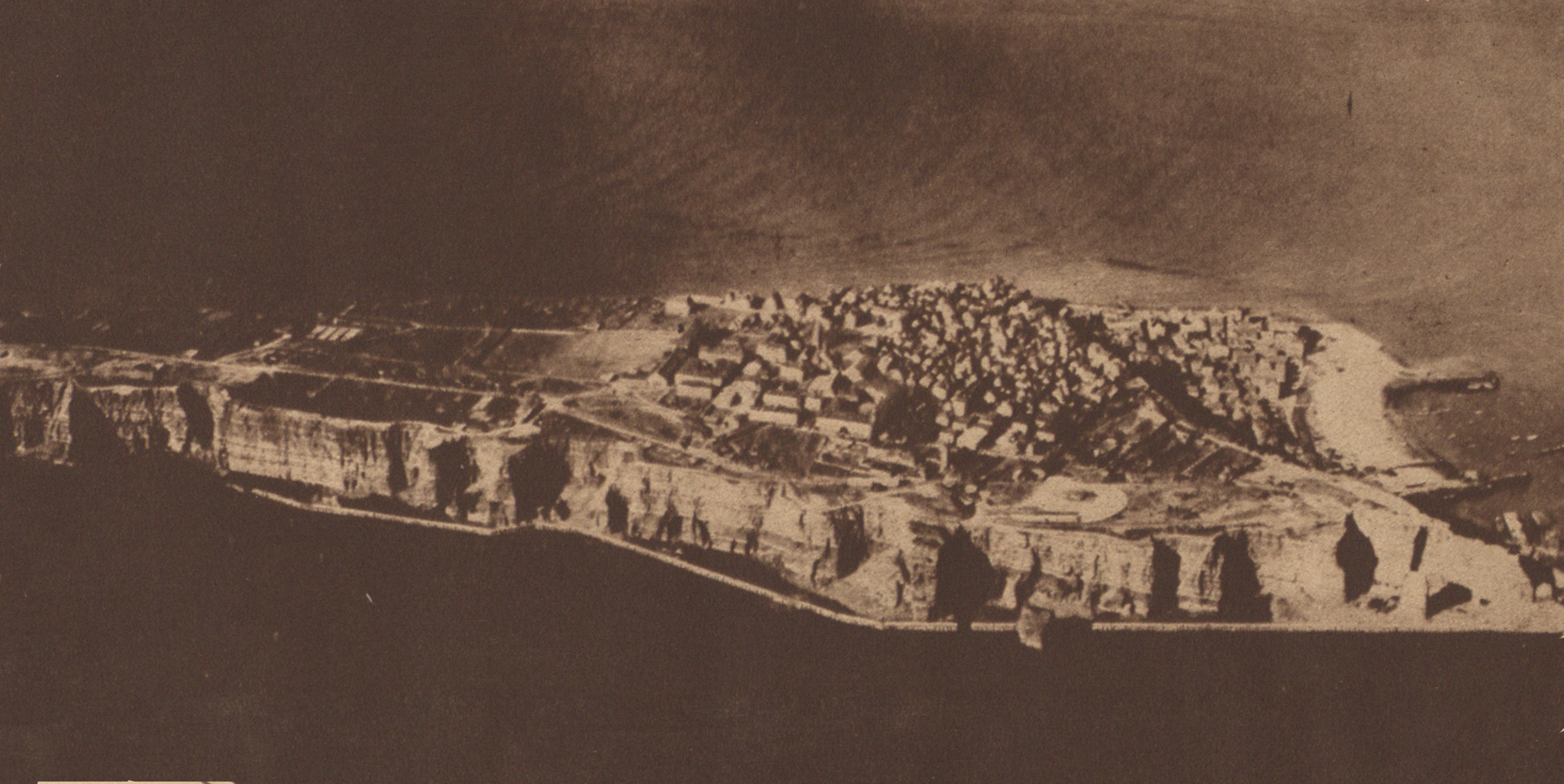

Heligoland is located off the German coastline and consists of two islands: the populated triangular main island () to the west, and the ('dune', Heligolandic: ) to the east. ''Heligoland'' generally refers to the former island. is somewhat smaller at , lower, and surrounded by sand beaches. It is not permanently inhabited, but is today the location of Heligoland's

Heligoland is located off the German coastline and consists of two islands: the populated triangular main island () to the west, and the ('dune', Heligolandic: ) to the east. ''Heligoland'' generally refers to the former island. is somewhat smaller at , lower, and surrounded by sand beaches. It is not permanently inhabited, but is today the location of Heligoland's airfield

An aerodrome, airfield, or airstrip is a location from which aircraft flight operations take place, regardless of whether they involve air cargo, passengers, or neither, and regardless of whether it is for public or private use. Aerodromes in ...

.

The main island is commonly divided into the ('Lower Land', Heligolandic: ) at sea level (to the right on the photograph, where the harbour is located), the ('Upper Land', Heligolandic: ) consisting of the plateau

In geology and physical geography, a plateau (; ; : plateaus or plateaux), also called a high plain or a tableland, is an area of a highland consisting of flat terrain that is raised sharply above the surrounding area on at least one side. ...

visible in the photographs, and the ('Middle Land') between them on one side of the island. The came into being in 1947 as a result of explosions detonated by the British Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

(the so-called "Big Bang"; see below).

The main island also features small beaches in the north and the south and drops to the sea high in the north, west and southwest. In the latter, the ground continues to drop underwater to a depth of below sea level. Heligoland's most famous landmark is the ('Long Anna' or 'Tall Anna'), a free-standing rock column (or stack

Stack may refer to:

Places

* Stack Island, an island game reserve in Bass Strait, south-eastern Australia, in Tasmania’s Hunter Island Group

* Blue Stack Mountains, in Co. Donegal, Ireland

People

* Stack (surname) (including a list of people ...

), high, found northwest of the island proper.

The two islands were connected until 1720 when the natural connection was destroyed by a storm flood

A storm surge, storm flood, tidal surge, or storm tide is a coastal flood or tsunami-like phenomenon of rising water commonly associated with low-pressure weather systems, such as cyclones. It is measured as the rise in water level above the ...

. The highest point is on the main island, reaching above sea level.

Although culturally and geographically closer to North Frisia

North Frisia (; ; ; ; ) is the northernmost portion of Frisia, located in Schleswig-Holstein, Germany, between the rivers Eider River, Eider and Vidå, Wiedau. It also includes the North Frisian Islands and Heligoland. The region is traditionally ...

in the German district of , the two islands are part of the district of Pinneberg

Pinneberg (; ) is a town in the federal state of Schleswig-Holstein in northern Germany. It is the capital of the Pinneberg (district), district of Pinneberg and has a population of about 43,500 inhabitants. Pinneberg is located 18 km northw ...

in the state of Schleswig-Holstein

Schleswig-Holstein (; ; ; ; ; occasionally in English ''Sleswick-Holsatia'') is the Northern Germany, northernmost of the 16 states of Germany, comprising most of the historical Duchy of Holstein and the southern part of the former Duchy of S ...

. The main island has a good harbour and is frequented mostly by sailing yachts.

History

The German Bight and the area around the island are known to have been inhabited since prehistoric times.

The German Bight and the area around the island are known to have been inhabited since prehistoric times. Flint tools

Stone tools have been used throughout human history but are most closely associated with prehistory, prehistoric cultures and in particular those of the Stone Age. Stone tools may be made of either ground stone or Lithic reduction, knapped stone, ...

have been recovered from the bottom of the sea surrounding Heligoland. On the ''Oberland'', prehistoric burial mounds

A tumulus (: tumuli) is a mound of earth and stones raised over a grave or graves. Tumuli are also known as barrows, burial mounds, mounds, howes, or in Siberia and Central Asia as ''kurgans'', and may be found throughout much of the world. ...

were visible until the late 19th century, and excavations showed skeletons and artefacts. Moreover, prehistoric copper plates have been found under water near the island; those plates were almost certainly made on the ''Oberland''.

In 697, Radbod, the last Frisian king, retreated to the then-single island after his defeat by the Franks

file:Frankish arms.JPG, Aristocratic Frankish burial items from the Merovingian dynasty

The Franks ( or ; ; ) were originally a group of Germanic peoples who lived near the Rhine river, Rhine-river military border of Germania Inferior, which wa ...

– or so it is written in the ''Life of Willebrord'' by Alcuin

Alcuin of York (; ; 735 – 19 May 804), also called Ealhwine, Alhwin, or Alchoin, was a scholar, clergyman, poet, and teacher from York, Northumbria. He was born around 735 and became the student of Ecgbert of York, Archbishop Ecgbert at Yor ...

. By 1231, the island was listed as the property of the Danish king Valdemar II

Valdemar II Valdemarsen (28 June 1170 – 28 March 1241), later remembered as Valdemar the Victorious () and Valdemar the Conqueror, was King of Denmark from 1202 until his death in 1241.

In 1207, Valdemar invaded and conquered Lybeck and Hol ...

. Archaeological findings from the 12th to 14th centuries suggest that copper ore was processed on the island.

There is a general understanding that the name "Heligoland" means "Holy Land" (compare modern Dutch and German '' heilig'', "holy"). In the course of the centuries several alternative theories have been proposed to explain the name, from a Danish king Heligo to a Frisian word, ''hallig'', meaning "salt marsh island". The 1911 ''Encyclopædia Britannica'' suggests ''Hallaglun'', or ''Halligland'', i.e. "land of banks, which cover and uncover".

Traditional economic activities included fishing, hunting birds and seals, wrecking and – very important for many overseas powers – piloting overseas ships into the harbours of Hanseatic League

The Hanseatic League was a Middle Ages, medieval commercial and defensive network of merchant guilds and market towns in Central Europe, Central and Northern Europe, Northern Europe. Growing from a few Northern Germany, North German towns in the ...

cities such as Bremen

Bremen (Low German also: ''Breem'' or ''Bräm''), officially the City Municipality of Bremen (, ), is the capital of the States of Germany, German state of the Bremen (state), Free Hanseatic City of Bremen (), a two-city-state consisting of the c ...

and Hamburg

Hamburg (, ; ), officially the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg,. is the List of cities in Germany by population, second-largest city in Germany after Berlin and List of cities in the European Union by population within city limits, 7th-lar ...

. In some periods Heligoland was an excellent base point for huge herring

Herring are various species of forage fish, belonging to the Order (biology), order Clupeiformes.

Herring often move in large Shoaling and schooling, schools around fishing banks and near the coast, found particularly in shallow, temperate wate ...

catches. Until 1714 ownership switched several times between Denmark–Norway

Denmark–Norway (Danish language, Danish and Norwegian language, Norwegian: ) is a term for the 16th-to-19th-century multi-national and multi-lingual real unionFeldbæk 1998:11 consisting of the Kingdom of Denmark, the Kingdom of Norway (includ ...

and the Duchy of Schleswig

The Duchy of Schleswig (; ; ; ; ; ) was a duchy in Southern Jutland () covering the area between about 60 km (35 miles) north and 70 km (45 mi) south of the current border between Germany and Denmark. The territory has been di ...

, with one period of control by Hamburg. In August 1714, it was conquered by Denmark–Norway, and it remained Danish until 1807.

19th century

On 11 September 1807, during the

On 11 September 1807, during the Napoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

, brought to the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

* Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Tra ...

the despatches from Admiral Thomas MacNamara Russell

Vice-Admiral Thomas Macnamara Russell (died 22 July 1824) was a Royal Navy officer who served in the American War of Independence and French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. Russell is best remembered for his command of a squadron in the North ...

announcing Heligoland's capitulation to the British. Heligoland became a centre of resistance and intrigue against Napoleon. Denmark then ceded Heligoland to George III of the United Kingdom

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and Ireland from 25 October 1760 until his death in 1820. The Acts of Union 1800 unified Great Britain and Ireland into the United Kingdom of Great ...

by the Treaty of Kiel

The Treaty of Kiel () or Peace of Kiel ( Swedish and or ') was concluded between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and the Kingdom of Sweden on one side and the Kingdoms of Denmark and Norway on the other side on 14 January 1814 ...

(14 January 1814). Thousands of Germans came to Britain and joined the King's German Legion

The King's German Legion (KGL; ) was a formation of the British Army during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. Consisting primarily of expatriate Germans, it existed from 1803 to 1816 and achieved the distinction of being the on ...

via Heligoland.

The British annexation of Heligoland was ratified by the Treaty of Paris signed on 30 May 1814, as part of a number of territorial reallocations following the abdication of Napoleon as Emperor of the French.

The prime reason at the time for Britain's retention of a small and seemingly worthless acquisition was to restrict any future French naval aggression against the Scandinavian or German states. In the event, no effort was made during the period of British administration to make use of the islands for military purposes, partly for financial reasons but principally because the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

considered Heligoland to be too exposed as a forward base.

In 1826, Heligoland became a seaside spa and soon turned into a popular tourist resort for the European upper class. The island attracted artists and writers, especially from Germany and Austria who apparently enjoyed the comparatively liberal atmosphere, including Heinrich Heine

Christian Johann Heinrich Heine (; ; born Harry Heine; 13 December 1797 – 17 February 1856) was an outstanding poet, writer, and literary criticism, literary critic of 19th-century German Romanticism. He is best known outside Germany for his ...

and August Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben

August Heinrich Hoffmann (, calling himself von Fallersleben, after his hometown; 2 April 179819 January 1874) was a German poet. He is best known for writing "", whose third stanza is now the national anthem of Germany, and a number of popular ...

. More vitally it was a refuge for revolutionaries of the 1830s and the 1848 German revolution.

The Leisure Hour

''The Leisure Hour'' was a British general-interest periodical of the Victorian era published weekly from 1852 to 1905. It was the most successful of several popular magazines published by the Religious Tract Society, which produced Christian lite ...

'', it was "a land where there are no bankers, no lawyers, and no crime; where all gratuities are strictly forbidden, the landladies are all honest and the boatmen take no tips", while ''The English Illustrated Magazine

''The English Illustrated Magazine'' was a monthly publication that ran for 359 issues between October 1883 and August 1913. Features included travel, topography, and a large amount of fiction and were contributed by writers such as Thomas Hardy ...

'' provided a description in the most glowing terms: "No one should go there who cannot be content with the charms of brilliant light, of ever-changing atmospheric effects, of a land free from the countless discomforts of a large and busy population, and of an air that tastes like draughts of life itself."

Britain ceded the islands to Germany in 1890 in the Heligoland–Zanzibar Treaty

The Heligoland–Zanzibar Treaty (; also known as the Anglo-German Agreement of 1890) was an agreement signed on 1 July 1890 between Germany and the United Kingdom.

The accord gave Germany control of the Caprivi Strip (a ribbon of land that gav ...

. The newly unified Germany was concerned about a foreign power controlling land from which it could command the western entrance to the militarily-important Kiel Canal

The Kiel Canal (, until 1948 called in German the ) is a fresh water canal that links the North Sea () to the Baltic Sea (). It runs through the Germany, German states of Germany, state of Schleswig-Holstein, from Brunsbüttel to the Holtenau di ...

, then under construction along with other naval installations in the area and thus traded for it. A " grandfathering"/ optant approach prevented the inhabitants of the islands from forfeiting advantages because of this imposed change of status.

Heligoland has an important place in the history of the study of ornithology

Ornithology, from Ancient Greek ὄρνις (''órnis''), meaning "bird", and -logy from λόγος (''lógos''), meaning "study", is a branch of zoology dedicated to the study of birds. Several aspects of ornithology differ from related discip ...

, and especially the understanding of bird migration. The book ''Heligoland, an Ornithological Observatory'' by Heinrich Gätke

Heinrich Gätke (born 19 May or 19 March 1814 in Pritzwalk – died 1 January 1897 in Heligoland) was a German ornithologist and artist.

Biography

The son of a baker, he was sent to study commerce in Berlin but became a painter. In 1837 he tr ...

, published in German in 1890 and in English in 1895, described an astonishing array of migrant birds on the island and was a major influence on future studies of bird migration

Bird migration is a seasonal movement of birds between breeding and wintering grounds that occurs twice a year. It is typically from north to south or from south to north. Animal migration, Migration is inherently risky, due to predation and ...

.

In 1892, the Biological Station of Helgoland was founded by phycologist Paul Kuckuck, a student of Johannes Reinke

Johannes Reinke (February 3, 1849 – February 25, 1931) was a German botanist and philosopher, born in Ziethen, Lauenburg. He is remembered for his research of benthic marine algae.

Academic background

Reinke studied botany with his father ...

(leading marine phycologist).

20th century

Under theGerman Empire

The German Empire (),; ; World Book, Inc. ''The World Book dictionary, Volume 1''. World Book, Inc., 2003. p. 572. States that Deutsches Reich translates as "German Realm" and was a former official name of Germany. also referred to as Imperia ...

, the islands became a major naval base, and during the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

the civilian population was evacuated to the mainland. The island was fortified with concrete gun emplacements along its cliffs similar to the Rock of Gibraltar

The Rock of Gibraltar (from the Arabic name Jabal Ṭāriq , meaning "Mountain of Tariq ibn Ziyad, Tariq") is a monolithic limestone mountain high dominating the western entrance to the Mediterranean Sea. It is situated near the end of a nar ...

. Island defences included 364 mounted guns including 142 disappearing gun

A disappearing gun, a gun mounted on a ''disappearing carriage'', is an obsolete type of artillery which enabled a gun to hide from direct fire and observation. The overwhelming majority of carriage designs enabled the gun to rotate bac ...

s overlooking shipping channels defended with ten rows of naval mine

A naval mine is a self-contained explosive weapon placed in water to damage or destroy surface ships or submarines. Similar to anti-personnel mine, anti-personnel and other land mines, and unlike purpose launched naval depth charges, they are ...

s. The first naval engagement of the war, the Battle of Heligoland Bight, was fought nearby in the first month of the war. The islanders returned in 1918, but during the Nazi

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During H ...

era the naval base was reactivated.

Werner Heisenberg

Werner Karl Heisenberg (; ; 5 December 1901 – 1 February 1976) was a German theoretical physicist, one of the main pioneers of the theory of quantum mechanics and a principal scientist in the German nuclear program during World War II.

He pub ...

(1901–1976) first formulated the equation underlying his theory of quantum mechanics while on Heligoland in the 1920s. While a student of Arnold Sommerfeld

Arnold Johannes Wilhelm Sommerfeld (; 5 December 1868 – 26 April 1951) was a German Theoretical physics, theoretical physicist who pioneered developments in Atomic physics, atomic and Quantum mechanics, quantum physics, and also educated and ...

at Munich, Heisenberg first met the Danish physicist Niels Bohr

Niels Henrik David Bohr (, ; ; 7 October 1885 – 18 November 1962) was a Danish theoretical physicist who made foundational contributions to understanding atomic structure and old quantum theory, quantum theory, for which he received the No ...

in 1922 at the Bohr Festival, Göttingen

Göttingen (, ; ; ) is a college town, university city in Lower Saxony, central Germany, the Capital (political), capital of Göttingen (district), the eponymous district. The River Leine runs through it. According to the 2022 German census, t ...

. He and Bohr went for long hikes in the mountains and discussed the failure of existing theories to account for the new experimental results on the quantum structure of matter. Following these discussions, Heisenberg plunged into several months of intensive theoretical research but met with continual frustration. Finally, suffering from a severe attack of hay fever

Allergic rhinitis, of which the seasonal type is called hay fever, is a type of rhinitis, inflammation in the nose that occurs when the immune system overreacts to allergens in the air. It is classified as a Allergy, type I hypersensitivity re ...

that his aspirin and cocaine treatment was failing to alleviate, he retreated to the treeless (and pollenless) island of Heligoland in the summer of 1925. There he conceived the basis of the quantum theory.

In 1937, construction began on a major reclamation project () intended to expand existing naval facilities and restore the island to its pre-1629 dimensions, restoring large areas which had been eroded by the sea. The project was largely abandoned after the start of World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

and was never completed.

World War II

The area was the setting of the aerial Battle of the Heligoland Bight in 1939, a result ofRoyal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the Air force, air and space force of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. It was formed towards the end of the World War I, First World War on 1 April 1918, on the merger of t ...

bombing raids on Kriegsmarine

The (, ) was the navy of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It superseded the Imperial German Navy of the German Empire (1871–1918) and the inter-war (1919–1935) of the Weimar Republic. The was one of three official military branch, branche ...

warships in the area. The waters surrounding the island were frequently mined by Allied aircraft.

Heligoland also had a military function as a sea fortress in the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. Completed and ready for use were the submarine bunker North Sea III, coastal artillery

Coastal artillery is the branch of the armed forces concerned with operating anti-ship artillery or fixed gun batteries in coastal fortifications.

From the Middle Ages until World War II, coastal artillery and naval artillery in the form of ...

, an air-raid shelter system with extensive bunker tunnels, and an airfield used by air force

An air force in the broadest sense is the national military branch that primarily conducts aerial warfare. More specifically, it is the branch of a nation's armed services that is responsible for aerial warfare as distinct from an army aviati ...

– (April to October 1943). Forced labour

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, or violence, including death or other forms of ...

of, among others, citizens of the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

was used in the construction of these military installations.''Lager russischer Offiziere und Soldaten, Helgoland Nordost''auf spurensuche-kreis-pinneberg.de On 3 December 1939, Heligoland was directly bombed by the

Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not an explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are calle ...

for the first time. The attack, by twenty four Wellington bombers of 38, 115, and 149 squadrons of the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the Air force, air and space force of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. It was formed towards the end of the World War I, First World War on 1 April 1918, on the merger of t ...

, failed to destroy the German warships at anchor.Seekrieg''1939 Dezember''

(Württemberg State Library, Stuttgart). Retrieved 4 July 2015. In three days in 1940, the

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

lost three submarine

A submarine (often shortened to sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. (It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability.) The term "submarine" is also sometimes used historically or infor ...

s near Heligoland: on 6 January, on 7 January and on 9 January.bremerhaven.de''Unter den Wellen Teil 3 – Britische U-Boote vor Helgoland''

. February 2013. Early in the war, the island was generally unaffected by bombing raids. Through the development of the

Luftwaffe

The Luftwaffe () was the aerial warfare, aerial-warfare branch of the before and during World War II. German Empire, Germany's military air arms during World War I, the of the Imperial German Army, Imperial Army and the of the Imperial Ge ...

, the island had largely lost its strategic importance. The , temporarily used for defence against Allied bombing raids, was equipped with a rare variant of the Messerschmitt Bf 109 fighter originally designed for use on aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and hangar facilities for supporting, arming, deploying and recovering carrier-based aircraft, shipborne aircraft. Typically it is the ...

s.

Not long before the war ended in 1945, Georg Braun and Erich Friedrichs succeeded in forming a resistance group on the island. Shortly before they were to execute their plans, however, they were betrayed by two members of the group. About twenty men were arrested on 18 April 1945; fourteen of them were transported to Cuxhaven

Cuxhaven (; ) is a town and seat of the Cuxhaven district, in Lower Saxony, Germany. The town includes the northernmost point of Lower Saxony. It is situated on the shore of the North Sea at the mouth of the Elbe River. Cuxhaven has a footprint o ...

. After a short trial, five resisters were executed by firing squad

Execution by firing squad, in the past sometimes called fusillading (from the French , rifle), is a method of capital punishment, particularly common in the military and in times of war. Some reasons for its use are that firearms are usually re ...

at Cuxhaven-Sahlenburg on 21 April 1945 by the German authorities.Wolfgang Stelljes. ''Verräter kam aus den eigenen Reihen.'' In: ''Journal'' (weekend edition of ''Nordwest Zeitung''), Volume 70, No. 84 (1112 April 2015), s. 1.

To honour them, in April 2010 the Helgoland Museum installed six stumbling blocks on the roads of Heligoland. Their names are Erich P. J. Friedrichs, Georg E. Braun, Karl Fnouka, Kurt A. Pester, Martin O. Wachtel, and Heinrich Prüß.

With two waves of bombing raids on 18 and 19 April 1945, 1,000 Allied aircraft dropped about 7,000 bombs on the islands. The populace took shelter in air raid shelters. The German military suffered heavy casualties during the raids.Imke Zimmermann''Im Schutz der roten Felsen – Bunker auf Helgoland''

vom 19. April 2005, auf fr-online.de The bomb attacks rendered the island unsafe, and it was totally evacuated.

Explosion

From 1945 to 1952 the uninhabited islands fell within theBritish Occupation zone

The British occupation zone in Germany (German: ''Britische Besatzungszone Deutschlands'') was one of the Allied-occupied areas in Germany after World War II. The United Kingdom, along with the Commonwealth, was one of the three major Allied po ...

. On 18 April 1947, the Royal Navy simultaneously detonated 6,700 metric tons of explosives (" Operation Big Bang" or "British Bang"), successfully destroying the island's principal military installations (namely, the submarine pens, the coastal batteries at the north and south ends of the island and of main storage tunnels) while leaving the town, already damaged by Allied bombing during the Second World War, "looking little worse" (according to an observer quoted in ''The Guardian'' newspaper). The destruction of the submarine pens resulted in the creation of the Mittelland crater. The British later used the island, from which the population had been evacuated, as a bombing range. The explosion was one of the biggest single non-nuclear detonations in history.

Return of sovereignty to Germany

On 20 December 1950, two students fromHeidelberg

Heidelberg (; ; ) is the List of cities in Baden-Württemberg by population, fifth-largest city in the States of Germany, German state of Baden-Württemberg, and with a population of about 163,000, of which roughly a quarter consists of studen ...

René Leudesdorff and Georg von Hatzfeld, accompanied by journalistsspent two days and a night on the island, planting in various combinations the flags of West Germany

West Germany was the common English name for the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) from its formation on 23 May 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with East Germany on 3 October 1990. It is sometimes known as the Bonn Republi ...

, the European Movement International

The European Movement International is a lobbying association that coordinates the efforts of associations and national councils with the goal of promoting European integration, and disseminating information about it.

History

Initially the Eur ...

and Heligoland. They returned with others on 27 December and on 29 December were joined by Heidelberg history professor and publicist Hubertus zu Löwenstein. The occupation was ended by British authorities, with cooperation of West German police, on 3 January 1951. The event started a movement to restore the islands to Germany, which gained the support of the West German parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

. On 1 March 1952, Heligoland was placed under West German control and the former inhabitants were allowed to return. The first of March is an official holiday on the island. The government of West Germany cleared a significant quantity of unexploded ordnance

Unexploded ordnance (UXO, sometimes abbreviated as UO) and unexploded bombs (UXBs) are explosive weapons (bombs, shell (projectile), shells, grenades, land mines, naval mines, cluster munition, and other Ammunition, munitions) that did not e ...

and rebuilt the houses before allowing its citizens to resettle there.

21st century

Heligoland, like the small exclave

Heligoland, like the small exclave Büsingen am Hochrhein

Büsingen am Hochrhein (, ; Alemannic: ', ), often known simply as Büsingen, is a German municipality () in the south of Baden-Württemberg with a population of about 1,548 inhabitants. It is an exclave of Germany and Baden-Württemberg, and ...

, is now a holiday resort and enjoys a tax-exempt status

Tax exemption is the reduction or removal of a liability to make a compulsory payment that would otherwise be imposed by a ruling power upon persons, property, income, or transactions. Tax-exempt status may provide complete relief from taxes, redu ...

, being part of Germany and the EU but excluded from the EU VAT area and customs union

A customs union is generally defined as a type of trade bloc which is composed of a free trade area with a common external tariff.GATTArticle 24 s. 8 (a)

Customs unions are established through trade pacts where the participant countries set u ...

. Consequently, much of the economy is founded on sales of cigarettes, alcoholic beverages, and perfume to tourists who visit the islands. The ornithological heritage of Heligoland has also been re-established, with the Heligoland Bird Observatory

The Heligoland Bird Observatory (''Vogelwarte Helgoland'' in German), one of the world's first ornithological observatories, is operated by the Ornithologische Arbeitsgemeinschaft Helgoland e.V., a non-profit organization which was founded in 1 ...

, now managed by the ("Ornithological Society of Heligoland") which was founded in 1991. A search and rescue

Search and rescue (SAR) is the search for and provision of aid to people who are in distress or imminent danger. The general field of search and rescue includes many specialty sub-fields, typically determined by the type of terrain the search ...

(SAR) base of the DGzRS, the (German Maritime Search and Rescue Service), is located on Heligoland.

Energy supply

Before the island was connected to the mainland network by a submarine cable in 2009, electricity on Heligoland was generated by a local diesel plant. Heligoland was the site of a trial of GROWIAN, a large wind-turbine testing project. In 1990, a 1.2 MW turbine of the MAN type WKA 60 was installed. Besides technical problems, the turbine was not lightning-proof and insurance companies would not provide coverage. The wind energy project was viewed as a failure by the islanders and was stopped. The Heligoland Power Cable has a length of and is one of the longest ACsubmarine power cable

A submarine power cable is a transmission cable for carrying electric power below the surface of the water.barge

A barge is typically a flat-bottomed boat, flat-bottomed vessel which does not have its own means of mechanical propulsion. Original use was on inland waterways, while modern use is on both inland and ocean, marine water environments. The firs ...

''Nostag 10'' in 2009. The cable is designed for an operational voltage

Voltage, also known as (electrical) potential difference, electric pressure, or electric tension, is the difference in electric potential between two points. In a Electrostatics, static electric field, it corresponds to the Work (electrical), ...

of 30 kV, and reaches the German mainland at Sankt Peter-Ording

Sankt Peter-Ording () is a popular German seaside spa and a municipality in the district of Nordfriesland, in Schleswig-Holstein, Germany. It is the only German seaside resort that has a sulphur spring and thus terms itself "North Sea spa and sul ...

.

Expansion plans and wind industry

Plans to re-enlarge the land bridge between different parts of the island by means ofland reclamation

Land reclamation, often known as reclamation, and also known as land fill (not to be confused with a waste landfill), is the process of creating new Terrestrial ecoregion, land from oceans, list of seas, seas, Stream bed, riverbeds or lake ...

came up between 2008 and 2010. However, the local community voted against the project.

Since 2013, a new industrial site is being expanded on the southern harbour. E.ON

E.ON SE is a European multinational electric utility company based in Essen, Germany. It operates as one of the world's largest investor-owned electric utility service providers. The name originates from the Latin word '' aeon'', derived from ...

, RWE

RWE AG is a German multinational energy company headquartered in Essen. It generates and trades electricity in the Asia-Pacific region, Europe and the United States.

In July 2020, RWE completed a far-reaching asset swap deal with E.ON first ...

and ''WindMW'' plan to manage operation and services of large offshore windparks from Heligoland. The range had been cleared of leftover ammunition.

Demographics

At the beginning of 2020, 1,399 people lived on Heligoland. As of 2018, the population is mostlyLutheran

Lutheranism is a major branch of Protestantism that emerged under the work of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German friar and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practices of the Catholic Church launched ...

(63%), while a minority (18%) is Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

. There is a multi-sport club on the island, VfL Fosite Helgoland, of which an estimated 500 islanders are members.

Climate

The climate of Heligoland is typical of an oceanic climate (Köppen Köppen is a German surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Bernd Köppen (1951–2014), German pianist and composer

* Carl Köppen (1833-1907), German military advisor in Meiji era Japan

* Edlef Köppen (1893–1939), German author ...

: ''Cfb''; Trewartha

Glenn Thomas Trewartha (1896 – 1984) was an American geographer of Cornish American descent.

He graduated from the University of Wisconsin–Madison, with a Ph.D. in 1924. He taught at the University of Wisconsin.

He gave an address to th ...

: ''Dolk''), being almost free of pollen and thus ideal for people with pollen allergies

Allergies, also known as allergic diseases, are various conditions caused by hypersensitivity of the immune system to typically harmless substances in the environment. These diseases include Allergic rhinitis, hay fever, Food allergy, food al ...

. Temperatures rarely drop below even in the winter. At times, winter temperatures can be higher than in Hamburg by up to because cold air from the east is warmed up over the North Sea. While spring tends to be comparatively cool, autumn on Heligoland is often longer and warmer than on the mainland, and statistically, the climate is generally sunnier.

Owing to the mild climate, figs

The fig is the edible fruit of ''Ficus carica'', a species of tree or shrub in the flowering plant family Moraceae, native to the Mediterranean region, together with western and southern Asia. It has been cultivated since ancient times and i ...

have reportedly been grown on the island as early as 1911, and a 2005 article mentioned Japanese bananas, figs, agave

''Agave'' (; ; ) is a genus of monocots native to the arid regions of the Americas. The genus is primarily known for its succulent and xerophytic species that typically form large Rosette (botany), rosettes of strong, fleshy leaves.

Many plan ...

s, palm tree

The Arecaceae () is a family of perennial, flowering plants in the monocot order Arecales. Their growth form can be climbers, shrubs, tree-like and stemless plants, all commonly known as palms. Those having a tree-like form are colloquially c ...

s and other exotic plants that had been planted on Heligoland and were thriving. There still is an old mulberry

''Morus'', a genus of flowering plants in the family Moraceae, consists of 19 species of deciduous trees commonly known as mulberries, growing wild and under cultivation in many temperate world regions. Generally, the genus has 64 subordinat ...

tree in the Upper Town.

The Heligoland weather station has recorded the following extreme values:

* Its highest temperature was on 25 July 1994.

* Its lowest temperature was on 15 February 1956.

* Its greatest annual precipitation was in 1998.

* Its least annual precipitation was in 1959.

* The longest annual sunshine was 2078 hours in 1959.

* The shortest annual sunshine was 1461.3 hours in 1985.

Geology

The island of Heligoland is a geological oddity; the presence of the main island's characteristic red

The island of Heligoland is a geological oddity; the presence of the main island's characteristic red sedimentary rock

Sedimentary rocks are types of rock (geology), rock formed by the cementation (geology), cementation of sediments—i.e. particles made of minerals (geological detritus) or organic matter (biological detritus)—that have been accumulated or de ...

in the middle of the German Bight is unusual. It is the only such formation of cliffs along the continental coast of the North Sea. The formation itself, called the Bunter sandstone or Buntsandstein

The Buntsandstein (German for ''coloured'' or ''colourful sandstone'') or Bunter sandstone is a lithostratigraphy, lithostratigraphic and allostratigraphy, allostratigraphic unit (a sequence of rock strata) in the Subsurface (geology), subsurface ...

, is from the early Triassic

The Triassic ( ; sometimes symbolized 🝈) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.5 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.4 Mya. The Triassic is t ...

geologic age. It is older than the white chalk that underlies the island Düne, the same rock that forms the White Cliffs of Dover

The White Cliffs of Dover are the region of English coastline facing the Strait of Dover and France. The cliff face, which reaches a height of , owes its striking appearance to its composition of chalk accented by streaks of black flint, depo ...

in England and cliffs of Danish and German islands in the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by the countries of Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden, and the North European Plain, North and Central European Plain regions. It is the ...

. A small chalk rock close to Heligoland, called ''witt Kliff'' (white cliff), is known to have existed within sight of the island to the west until the early 18th century, when storm floods finally eroded

Erosion is the action of surface processes (such as water flow or wind) that removes soil, rock, or dissolved material from one location on the Earth's crust and then transports it to another location where it is deposited. Erosion is disti ...

it to below sea level.

Heligoland's rock is significantly harder than the postglacial sediments and sands forming the islands and coastlines to the east of the island. This is why the core of the island, which a thousand years ago was still surrounded by a large low-lying marshland and sand dunes separated from coast in the east only by narrow channels, has remained to this day, although the onset of the North Sea has long eroded away all of its surroundings. A small piece of Heligoland's sand dunes remains – the sand isle just across the harbour called Düne (Dune). A referendum in June 2011 dismissed a proposal to reconnect the main island to the Düne islet with a landfill

A landfill is a site for the disposal of waste materials. It is the oldest and most common form of waste disposal, although the systematic burial of waste with daily, intermediate and final covers only began in the 1940s. In the past, waste was ...

.

Flag

coat of arms

A coat of arms is a heraldry, heraldic communication design, visual design on an escutcheon (heraldry), escutcheon (i.e., shield), surcoat, or tabard (the last two being outer garments), originating in Europe. The coat of arms on an escutcheon f ...

– it is a tricolour flag with three horizontal bars, from top to bottom: green, red and white. Each of the colours has its symbolic meaning, as expressed in its motto:

There is an alternative version in which the word ("sand") is replaced with ("beach").

Road restrictions

A special section in the German traffic regulations (''Straßenverkehrsordnung'', abbr. ''StVO''), §50, prohibits the use of automobiles and bicycles on the island.

The island received its first police car on 17 January 2006; until then the island's policemen moved on foot and by bicycle, being exempt from the bicycle ban.

A special section in the German traffic regulations (''Straßenverkehrsordnung'', abbr. ''StVO''), §50, prohibits the use of automobiles and bicycles on the island.

The island received its first police car on 17 January 2006; until then the island's policemen moved on foot and by bicycle, being exempt from the bicycle ban.

Emergency services

Ambulance services are provided by the Paracelsus North Sea Clinic Helgoland in co-operation with the State Rescue Service of Schleswig-Holstein (RKiSH). There are three ambulances available: one on the main island and one on Düne; the third is in reserve on the main island. The ambulance service drives first to the Paracelsus North Sea Clinic. In the event of serious injuries or illnesses, the patients are transferred to the mainland either with a rescue helicopter or a sea rescue cruiser operated by the German Society for the Rescue of Shipwrecked Persons (DGzRS). If there is an emergency on the Düne, the ambulance crew takes a boat to the Düne and carries out the operation with the ambulance based there. Fire protection and technical assistance are provided by the Helgoland volunteer fire brigade, which has three stations (Unterland, Oberland and Düne).The tasks also include ensuring fire protection during flight operations at the Heligoland-Düne airfield. Volunteer firefighters are deployed on Düne in the summer, who report for 14 days and go on holiday with their families on the island and go into action in an emergency. There are normally five police officers based on Heligoland. They have the use of an electric car and a number of bicycles. In the summer months the population can also triple with up to 3,000 day-trippers and additional overnight visitors. Occasionally, the usual complement of police officers is supplemented by additional officers from the mainland during this period. Since 2021, the so-called BOS centre, a joint service building for the fire brigade, ambulance service and police, has been under construction on the Oberland, and will incorporate five apartments for police staff on the upper floor.Notable residents

* Peter Andresen Oelrichs (1781–1869), a lexicographer and linguist.

*

* Peter Andresen Oelrichs (1781–1869), a lexicographer and linguist.

* John Hindmarsh

Rear-Admiral Sir John Hindmarsh KH (baptised 22 May 1785 – 29 July 1860) was a naval officer and the first Governor of South Australia, from 28 December 1836 to 16 July 1838.

Family

His grandfather William Hindmarsh was a gardener in Coni ...

(1785–1860), veteran of the Battle of Trafalgar

The Battle of Trafalgar was a naval engagement that took place on 21 October 1805 between the Royal Navy and a combined fleet of the French Navy, French and Spanish Navy, Spanish navies during the War of the Third Coalition. As part of Na ...

and first governor of South Australia

The governor of South Australia is the representative in South Australia of the monarch, currently King Charles III. The governor performs the same constitutional and ceremonial functions at the state level as does the governor-general of Aust ...

, the governor of Heligoland 1840–57

* Heinrich Gätke

Heinrich Gätke (born 19 May or 19 March 1814 in Pritzwalk – died 1 January 1897 in Heligoland) was a German ornithologist and artist.

Biography

The son of a baker, he was sent to study commerce in Berlin but became a painter. In 1837 he tr ...

(1814–1897), artist and ornithologist, died on the island

* August Uihlein

Georg Karl August Uihlein (August 25, 1842 – October 11, 1911) was a German-Americans, German-American brewing, brewer, business executive, and horse breeder.

Early life

August Uihlein was born Georg Karl August Ühlein in 1842 in Wertheim am ...

(1842–1911), a German-American brewer, business executive and horse breeder, died on the island

* Richard Mansfield

Richard Mansfield (24 May 1857 – 30 August 1907) was a German-born English actor-manager best known for his performances in Shakespeare plays, Gilbert and Sullivan operas, and the play ''Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1887 play), Dr. Jekyll and Mr ...

(1857–1907), actor, brought up on the island.

* Robert Knud Friedrich Pilger

Robert Knud Friedrich Pilger (3 July 1876, Helgoland – 1 September 1953, Berlin) Eva von der Osten

Eva Helga Bertha von der Osten (19 August 1881 – 5 May 1936) was a German dramatic soprano.

Biography

She was born in Helgoland, the daughter of actor (1847–1905) and Rosa von der Osten-Hildebrandt (1850–1911). Von der Osten debuted in 19 ...

(1881–1936), the soprano, was born here.

* James Krüss

James Krüss (31 May 1926 – 2 August 1997) was a German writer of children's literature, children's and picture books, illustrator, poet, dramatist, scriptwriter, translator, and collector of children's poems and folk songs. For his contributi ...

(1926–1997), writer of children's and picture books, illustrator, poet, dramatist and scriptwriter

In culture

* Heligoland appeared in the BritishShipping Forecast

The ''Shipping Forecast'' is a BBC Radio broadcast of weather reports and forecasts for the seas around the British Isles. It is produced by the Met Office and broadcast by BBC Radio 4 on behalf of the Maritime and Coastguard Agency. The for ...

up until 1956 when it was renamed German Bight. The name of Shena Mackay

Shena Mackay FRSL (born 6 June 1944) is a Scottish novelist born in Edinburgh. She was shortlisted for the Booker Prize for Fiction in 1996 for '' The Orchard on Fire'', and was shortlisted for the Whitbread Prize and the Orange Prize for Fictio ...

's 2003 novel ''Heligoland

Heligoland (; , ; Heligolandic Frisian: , , Mooring Frisian: , ) is a small archipelago in the North Sea. The islands were historically possessions of Denmark, then became possessions of the United Kingdom from 1807 to 1890. Since 1890, the ...

'' is prompted by its disappearance from the forecast.

* Physicist Carlo Rovelli

Carlo Rovelli (born 3 May 1956) is an Italian theoretical physicist and writer who has worked in Italy, the United States, France, and Canada. He is currently Emeritus Professor at the Centre de Physique Theorique of Marseille in France, a Disti ...

titled his 2020 popular science book on quantum mechanics

Quantum mechanics is the fundamental physical Scientific theory, theory that describes the behavior of matter and of light; its unusual characteristics typically occur at and below the scale of atoms. Reprinted, Addison-Wesley, 1989, It is ...

''Helgoland

Heligoland (; , ; Heligolandic Frisian: , , Mooring Frisian: , ) is a small archipelago in the North Sea. The islands were historically possessions of Denmark, then became possessions of the United Kingdom from 1807 to 1890. Since 1890, the ...

''. This is because Werner Heisenberg

Werner Karl Heisenberg (; ; 5 December 1901 – 1 February 1976) was a German theoretical physicist, one of the main pioneers of the theory of quantum mechanics and a principal scientist in the German nuclear program during World War II.

He pub ...

got the first intuition about the theory while staying on the island in the 1920s.

* In the game ''Battlefield 1

''Battlefield 1'' is a 2016 first-person shooter game developed by DICE and published by Electronic Arts. It is the tenth installment in the ''Battlefield'' series and the first main entry in the series since ''Battlefield 4'' in 2013. It was ...

'', Heligoland Bight appeared as a map in the Turning Tides expansion DLC with the German army defending against the British Royal Marines.

*Composer Anton Bruckner

Joseph Anton Bruckner (; ; 4 September 182411 October 1896) was an Austrian composer and organist best known for his Symphonies by Anton Bruckner, symphonies and sacred music, which includes List of masses by Anton Bruckner, Masses, Te Deum (Br ...

wrote a cantata in 1893 titled Helgoland

Heligoland (; , ; Heligolandic Frisian: , , Mooring Frisian: , ) is a small archipelago in the North Sea. The islands were historically possessions of Denmark, then became possessions of the United Kingdom from 1807 to 1890. Since 1890, the ...

commemorating Britain's gift of the island to Germany a few years earlier. It was Bruckner's last completed work.

*British trip-hop group Massive Attack

Massive Attack are an English trip hop collective formed in 1988 in Bristol, England, by Robert Del Naja, Robert "3D" Del Naja, Daddy G, Grant "Daddy G" Marshall, Tricky (musician), Adrian "Tricky" Thaws and Andrew Vowles, Andrew "Mushroom" ...

named their studio

A studio is a space set aside for creative work of any kind, including art, dance, music and theater.

The word ''studio'' is derived from the , from , from ''studere'', meaning to study or zeal.

Types Art

The studio of any artist, esp ...

album after the island.

Leaders of Heligoland

Lieutenant-Governors

The British Lieutenant-Governors of Heligoland from 1807 to 1890 were: * 1807–1808: Corbet James d'Auvergne * 1808–1815: William Osborne Hamilton (1750–1818) * 1815–1840: Sir Henry King * 1840–1856: SirJohn Hindmarsh

Rear-Admiral Sir John Hindmarsh KH (baptised 22 May 1785 – 29 July 1860) was a naval officer and the first Governor of South Australia, from 28 December 1836 to 16 July 1838.

Family

His grandfather William Hindmarsh was a gardener in Coni ...

* 1857–1863: Richard Pattinson

* 1863–1881: Sir Henry Berkeley Fitzhardinge Maxse

Lieutenant-Colonel Sir Henry Berkeley Fitzhardinge Maxse (1 January 1832 – 10 September 1883) was a British Army officer of the Crimean War and colonial official who was Governor of Newfoundland.

Biography

Maxse was the son of James Max ...

* 1881–1888: Sir John Terence Nicholls O'Brien

* 1888–1890: Arthur Cecil Stuart Barkly

See also

*Forseti

''Forseti Seated in Judgment'' (1881) by Carl Emil Doepler

Forseti (Old Norse "the presiding one", " president" in modern Icelandic and Faroese) is the god of justice and reconciliation in Norse mythology. He is generally identified with Fosi ...

– a Norse god whose central place of worship was at Heligoland

* Location hypotheses of Atlantis

There exist a variety of speculative proposals that real-world events could have inspired Plato's fictional story of Atlantis, told in the ''Timaeus (dialogue), Timaeus'' and ''Critias (dialogue), Critias''. While Plato's story was not part of th ...

– Heligoland is hypothesized as a possible location for Atlantis by the Austrian-born author Jürgen Spanuth.

* Postage stamps and postal history of Heligoland

During the period when Heligoland (a German island in the North Sea) was a British possession, about 20 postage stamps were issued between 1867 and 1890. There were up to eight printings of a single denomination and also a large volume of postag ...

* Heligoland–Zanzibar Treaty

The Heligoland–Zanzibar Treaty (; also known as the Anglo-German Agreement of 1890) was an agreement signed on 1 July 1890 between Germany and the United Kingdom.

The accord gave Germany control of the Caprivi Strip (a ribbon of land that gav ...

References

Further reading

Papers

* * Historical synopsis with review of modern economy and society on Heligoland. *Books

* Andres, Jörg: ''Insel Helgoland. Die »Seefestung« und ihr Erbe.'' Ch. Links Verlag, Berlin 2015, . * * Dierschke, Jochen: ''Die Vogelwelt der Insel Helgoland.'' Missing Link E. G., 2011, . * (originally published in 2002, ) * Friederichs, A.: ''Wir wollten Helgoland retten – Auf den Spuren der Widerstandsgruppe von 1945.'' Museum Helgoland, 2010, . * Grahn-Hoek, Heike: ''Roter Flint und Heiliges Land Helgoland.'' Wachholtz-Verlag, Neumünster 2009, . * * Wallmann, Eckhard: ''Eine Kolonie wird deutsch – Helgoland zwischen den Weltkriegen.'' Nordfriisk Instituut, Bredstedt 2012, . 1890 cessionSecond Reading in the House of Commons

External links

Film clip of coast defenses

Heligoland Tourist Board

– includes a virtual tour of the island.

Heligoland Bird Observatory

Footage of Destruction of Heligoland fortifications April 1947

{{Authority control Archipelagoes of Germany Landforms of Schleswig-Holstein Special territories of the European Union Former British colonies and protectorates in Europe Car-free islands of Europe Germany–United Kingdom relations Pinneberg (district) Frisian Islands 1807 establishments in the British Empire 1890 disestablishments in the British Empire Special economic zones Duty-free zones of Europe Tax avoidance