Harry Johnston (footballer, Born 1949) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Harry Hamilton Johnston (12 June 1858 – 31 July 1927) was a British

In 1896, in recognition of this achievement, Johnston was appointed

In 1896, in recognition of this achievement, Johnston was appointed

''British Central Africa''

(1897) * ''A History of the Colonization of Africa by Alien Races'' (1899) * ''The Uganda Protectorate'' (1902) * ''The Living Races of Mankind'' (1902). * ''The Nile Quest: The Story of Exploration'' (190

* ''Liberia'' (1907) * ''

* ''Phonetic Spelling'' (1913

online

*''Pioneers in India''] (1913

* ''A Comparative Study of the Bantu and Semi-Bantu Languages'' (1919, 1922)

online

* ''The Gay-Dombeys'' (1919) – a sequel to

* ''The Veneerings'' (1922) – a sequel to

* Manuscripts of collected vocabularies of Sir Harry Hamilton Johnston are held by SOAS University of London, SOAS Archives.

Full text of Johnston's book ''British Central Africa'' (1897).

(text only)

Full text of Johnston's book ''British Central Africa'' (1897).

(facsimile) * * * *Th

International Primary School

which bears Sir Harry Johnston's name was founded in the early 1950s in

explorer

Exploration is the process of exploring, an activity which has some Expectation (epistemic), expectation of Discovery (observation), discovery. Organised exploration is largely a human activity, but exploratory activity is common to most organis ...

, botanist

Botany, also called plant science, is the branch of natural science and biology studying plants, especially Plant anatomy, their anatomy, Plant taxonomy, taxonomy, and Plant ecology, ecology. A botanist or plant scientist is a scientist who s ...

, artist, colonial administrator

Colonialism is the control of another territory, natural resources and people by a foreign group. Colonizers control the political and tribal power of the colonised territory. While frequently an Imperialism, imperialist project, colonialism c ...

, and linguist who travelled widely across Africa to speak some of the languages spoken by people on that continent. He published 40 books on subjects related to the continent of Africa and was one of the key players in the Scramble for Africa

The Scramble for Africa was the invasion, conquest, and colonialism, colonisation of most of Africa by seven Western European powers driven by the Second Industrial Revolution during the late 19th century and early 20th century in the era of ...

that occurred at the end of the 19th century.

Early years

Johnston was born atKennington Park

Kennington Park is a public park in Kennington, south London and lies between Kennington Park Road and St. Agnes Place. It was opened in 1854 on the site of what had been Kennington Common, where the Chartists gathered for their biggest " ...

, south London, the son of John Brookes Johnstone and Esther Laetitia Hamilton. He attended Stockwell

Stockwell is a district located in South London, part of the London Borough of Lambeth, England. It is situated south of Charing Cross.

History

The name Stockwell is likely to have originated from a local well, with "stoc" being Old Englis ...

grammar school and then King's College London

King's College London (informally King's or KCL) is a public university, public research university in London, England. King's was established by royal charter in 1829 under the patronage of George IV of the United Kingdom, King George IV ...

, followed by four years studying painting at the Royal Academy

The Royal Academy of Arts (RA) is an art institution based in Burlington House in Piccadilly London, England. Founded in 1768, it has a unique position as an independent, privately funded institution led by eminent artists and architects. Its ...

. In connection with his studies, he travelled to Europe and North Africa, visiting the little-known (by Europeans) interior of Tunisia

Tunisia, officially the Republic of Tunisia, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered by Algeria to the west and southwest, Libya to the southeast, and the Mediterranean Sea to the north and east. Tunisia also shares m ...

.

Exploration in Africa

In 1882, he visited southernAngola

Angola, officially the Republic of Angola, is a country on the west-Central Africa, central coast of Southern Africa. It is the second-largest Portuguese-speaking world, Portuguese-speaking (Lusophone) country in both total area and List of c ...

with the Earl of Mayo

Earl of the County of Mayo, usually known simply as Earl of Mayo (), is a title in the Peerage of Ireland created, in 1785, for John Bourke, 1st Viscount Mayo (of the second creation). For many years he served as "First Commissioner of Revenue" ...

, and in the following year met Henry Morton Stanley

Sir Henry Morton Stanley (born John Rowlands; 28 January 1841 – 10 May 1904) was a Welsh-American explorer, journalist, soldier, colonial administrator, author, and politician famous for his exploration of Central Africa and search for missi ...

in the Congo, becoming one of the first Europeans after Stanley to see the river above the Stanley Pool

The Pool Malebo, formerly Stanley Pool, also known as Mpumbu, Lake Nkunda or Lake Nkuna by local indigenous people in pre-colonial times, is a lake-like widening in the lower reaches of the Congo River.

.

His developing reputation led the Royal Geographical Society

The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers), often shortened to RGS, is a learned society and professional body for geography based in the United Kingdom. Founded in 1830 for the advancement of geographical scien ...

and the British Association

The British Science Association (BSA) is a charity and learned society founded in 1831 to aid in the promotion and development of science. Until 2009 it was known as the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BA). The current Chief ...

to appoint him leader of a scientific expedition to Mount Kilimanjaro

Mount Kilimanjaro () is a dormant volcano in Tanzania. It is the highest mountain in Africa and the highest free-standing mountain above sea level in the world, at above sea level and above its plateau base. It is also the highest volcano i ...

in 1884. On the expedition, Johnston concluded treaties with local chiefs (which were then transferred to the British East Africa Company

The Imperial British East Africa Company (IBEAC) was a commercial association founded to develop African trade in the areas controlled by the British Empire. The company was incorporated in London on 18 April 1888 and granted a royal charter by ...

), in competition with German efforts to do likewise.

British colonial service and the Cape to Cairo vision

In October 1886, the British government appointed him vice-consul inCameroon

Cameroon, officially the Republic of Cameroon, is a country in Central Africa. It shares boundaries with Nigeria to the west and north, Chad to the northeast, the Central African Republic to the east, and Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, and the R ...

and the Niger River

The Niger River ( ; ) is the main river of West Africa, extending about . Its drainage basin is in area. Its source is in the Guinea Highlands in south-eastern Guinea near the Sierra Leone border. It runs in a crescent shape through Mali, Nige ...

delta area, where a protectorate had been declared in 1885, and he became acting consul in 1887, deposing and banishing the local chief Jaja

Jaja may refer to:

People

* Jajá Coelho (born 1986), Jakson Avelino Coelho, Brazilian football striker

* Jajá (footballer, born 1974), Jair Xavier de Brito, Brazilian football winger

* Jajá (footballer, born 1986), Francisco Jaílson de Sousa, ...

.

While in West Africa in 1886, Johnston sketched what has been termed a "fantasy map" of his ideas of how the African continent could be divided among the colonial powers. This envisaged two blocks of British colonies, one of continuous territory in West Africa, the Nile

The Nile (also known as the Nile River or River Nile) is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa. It has historically been considered the List of river sy ...

valley and much of East Africa as far south as Lake Tanganyika

Lake Tanganyika ( ; ) is an African Great Lakes, African Great Lake. It is the world's List of lakes by volume, second-largest freshwater lake by volume and the List of lakes by depth, second deepest, in both cases after Lake Baikal in Siberia. ...

and Lake Nyasa

Lake Malawi, also known as Lake Nyasa in Tanzania and Lago Niassa in Mozambique, () is an African Great Lake and the southernmost lake in the East African Rift system, located between Malawi, Mozambique and Tanzania.

It is the fourth largest ...

, the other in southern Africa south of the Zambezi

The Zambezi (also spelled Zambeze and Zambesi) is the fourth-longest river in Africa, the longest east-flowing river in Africa and the largest flowing into the Indian Ocean from Africa. Its drainage basin covers , slightly less than half of t ...

. This left a continuous band in Portuguese occupation from Angola

Angola, officially the Republic of Angola, is a country on the west-Central Africa, central coast of Southern Africa. It is the second-largest Portuguese-speaking world, Portuguese-speaking (Lusophone) country in both total area and List of c ...

to Mozambique

Mozambique, officially the Republic of Mozambique, is a country located in Southeast Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi and Zambia to the northwest, Zimbabwe to the west, and Eswatini and South Afr ...

and Germany in possession of much of the East African coast.

The original proposal for a Cape to Cairo railway

The Cape to Cairo Railway is an unfinished project to create a railway line crossing from southern to northern Africa. It would have been the largest, and most important, railway of the continent. It was planned as a link between Cape Town i ...

was made in 1874 by Edwin Arnold

Sir Edwin Arnold (10 June 1832 – 24 March 1904) was an English poet and journalist. He is best known for his 1879 work, '' The Light of Asia''.

Born in Gravesend, Kent, Arnold's early education at King's School, Rochester, and later at Kin ...

, the then editor of the ''Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a British daily broadsheet conservative newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed in the United Kingdom and internationally. It was foun ...

'', which was joint sponsor of the expedition by H. M. Stanley

Sir Henry Morton Stanley (born John Rowlands; 28 January 1841 – 10 May 1904) was a Welsh-American explorer, journalist, soldier, colonial administrator, author, and politician famous for his exploration of Central Africa and search for missi ...

to Africa to discover the course of the Congo River

The Congo River, formerly also known as the Zaire River, is the second-longest river in Africa, shorter only than the Nile, as well as the third-largest river in the world list of rivers by discharge, by discharge volume, following the Amazon Ri ...

. The proposed route involved a mixture of railway and river transport between Elizabethville, now Lubumbashi

Lubumbashi ( , ; former ; former ) is the second-largest Cities of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, city in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, located in the country's southeasternmost part, along the border with Zambia. The capital ...

in the Belgian Congo

The Belgian Congo (, ; ) was a Belgian colonial empire, Belgian colony in Central Africa from 1908 until independence in 1960 and became the Republic of the Congo (Léopoldville). The former colony adopted its present name, the Democratic Repu ...

and Sennar

Sennar ( ') is a city on the Blue Nile in Sudan and possibly the capital of the state of Sennar. For several centuries it was the capital of the Funj Kingdom of Sennar and until at least 2011, Sennar was the capital of Sennar State.

Histo ...

in the Sudan

Sudan, officially the Republic of the Sudan, is a country in Northeast Africa. It borders the Central African Republic to the southwest, Chad to the west, Libya to the northwest, Egypt to the north, the Red Sea to the east, Eritrea and Ethiopi ...

rather than a completely rail one. Johnston later acknowledged his debt to Stanley and Arnold and when on leave in England in 1888, he revived the Cape-to-Cairo concept of acquiring a continuous band of British territory down Africa in discussion with Lord Salisbury

Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury (; 3 February 183022 August 1903), known as Lord Salisbury, was a British statesman and Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United ...

. Johnston then published an supporting the idea article in ''Times

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events, and a fundamental quantity of measuring systems.

Time or times may also refer to:

Temporal measurement

* Time in physics, defined by its measurement

* Time standard, civil time specificat ...

'' anonymously, as "by an African Explorer" and later in 1888 and 1889 published a number of articles in other newspapers and journals with Salisbury's tacit approval.

Scramble for Katanga

TheBerlin Conference

The Berlin Conference of 1884–1885 was a meeting of colonial powers that concluded with the signing of the General Act of Berlin,

had allocated Katanga to the sphere of influence of King Leopold of Belgium

This is a list of Belgian monarchs from 1831 when the first Belgian king, Leopold I, ascended the throne, after Belgium seceded from the Kingdom of the Netherlands during the Belgian Revolution of 1830.

Under the Belgian Constitution, the Belgi ...

's Congo Free State

The Congo Free State, also known as the Independent State of the Congo (), was a large Sovereign state, state and absolute monarchy in Central Africa from 1885 to 1908. It was privately owned by Leopold II of Belgium, King Leopold II, the const ...

, but under the Berlin Conference's Principle of Effectivity this was only provisional. In July 1890, Leopold protested to Lord Salisbury that Johnston, as agent for Cecil Rhodes

Cecil John Rhodes ( ; 5 July 185326 March 1902) was an English-South African mining magnate and politician in southern Africa who served as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony from 1890 to 1896. He and his British South Africa Company founded th ...

, was circulating maps showing that the Congo Free State did not include Katanga, and in response to Salisbury's enquiries, in August 1890 Johnston presented Rhodes' claim, which included the false information that Msiri

Msiri (c. 1830 – December 20, 1891) founded and ruled the Yeke Kingdom (also called the Garanganze or Garenganze kingdom) in south-east Katanga (now in DR Congo) from about 1856 to 1891. His name is sometimes spelled 'M'Siri' in articles in F ...

, King of Garanganze in Katanga had asked for British protection.

In November 1890, to justify his claim, Johnston sent Alfred Sharpe

Sir Alfred Sharpe (19 May 1853 – 10 December 1935) was Commissioner and Consul-General for the British Central Africa Protectorate and first Governor of Nyasaland.

He trained as a solicitor but was in turn a planter and a professional hu ...

(who would become his successor in Nyasaland) to act for Rhodes and the British South Africa Company

The British South Africa Company (BSAC or BSACo) was chartered in 1889 following the amalgamation of Cecil Rhodes' Central Search Association and the London-based Exploring Company Ltd, which had originally competed to capitalize on the expecte ...

(BSAC), to obtain a treaty with Msiri, a move which had the potential to precipitate an Anglo-Belgian crisis. Sharpe failed with Msiri, though he obtained treaties with Mwata Kazembe covering the eastern side of the Luapula River

The Luapula River is a north-flowing river of central Africa, within the Congo River watershed. It rises in the wetlands of Lake Bangweulu (Zambia), which are fed by the Chambeshi River. The Luapula flows west then north, marking the border betw ...

and Lake Mweru

Lake Mweru (also spelled ''Mwelu'', ''Mwero'') (, ) is a freshwater lake on the longest arm of Africa's second-longest river, the Congo. Located on the border between Zambia and Democratic Republic of the Congo, it makes up of the total length ...

, and with other chiefs covering the southern end of Lake Tanganyika

Lake Tanganyika ( ; ) is an African Great Lakes, African Great Lake. It is the world's List of lakes by volume, second-largest freshwater lake by volume and the List of lakes by depth, second deepest, in both cases after Lake Baikal in Siberia. ...

. When Leopold again protested to Salisbury in May 1891, the latter had to admit Msiri had not signed a treaty asking for British protection and left Katanga open to Belgian colonisation. In 1891 Leopold sent the Stairs Expedition

The Stairs Expedition to Katanga (1891−92), led by Captain William Stairs, was the winner in a race between two imperial powers, the British South Africa Company BSAC and the Congo Free State, to claim Katanga, a vast mineral-rich territo ...

to Katanga. Johnston dissuaded it from entering Katanga through Nyasaland, but it went through German East Africa

German East Africa (GEA; ) was a German colonial empire, German colony in the African Great Lakes region, which included present-day Burundi, Rwanda, the Tanzania mainland, and the Kionga Triangle, a small region later incorporated into Portugu ...

instead, and took Katanga after killing Msiri. The southern border of the Congo Free State was settled by an Anglo-Congo agreement of 1894.

Nyasaland (British Central Africa Protectorate)

In 1879, the Portuguese government formally claimed the area south and east of theRuo River

Ruo River is the largest tributary of the Shire River in southern Malawi and Mozambique. It originates from the Mulanje Massif (Malawi) and forms of the Malawi-Mozambique border. It joins the Shire River at Chiromo.

The Ruo River watershed in ...

(currently the southeastern border of Malawi

Malawi, officially the Republic of Malawi, is a landlocked country in Southeastern Africa. It is bordered by Zambia to the west, Tanzania to the north and northeast, and Mozambique to the east, south, and southwest. Malawi spans over and ...

) and then, in 1882, occupied the lower Shire River

The Shire is the largest river in Malawi. It is the only outlet of Lake Malawi and flows into the Zambezi River in Mozambique. Its length is . The upper Shire River issues from Lake Malawi and runs approximately before it enters shallow Lake Malo ...

valley as far north as the Ruo. It attempted to gain British acceptance of this claim without success, and also failed in a claim that the Shire Highlands

The Shire Highlands are a plateau in southern Malawi, located east of the Shire River. It is a major agricultural area and the most densely populated part of the country.

Geography

The highlands cover an area of roughly 7250 square kilometers. ...

was part of Portuguese East Africa

Portuguese Mozambique () or Portuguese East Africa () were the common terms by which Mozambique was designated during the period in which it was a Portuguese Empire, Portuguese overseas province. Portuguese Mozambique originally constituted a str ...

, as it was not under effective occupation As late as 1888, the British Foreign Office

Foreign may refer to:

Government

* Foreign policy, how a country interacts with other countries

* Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in many countries

** Foreign Office, a department of the UK government

** Foreign office and foreign minister

* United ...

would not accept responsibility for British missionaries and settlers in the Shire Highlands after the African Lakes Corporation

The African Lakes Corporation plc was a British company originally set-up in 1877 by Scottish businessmen to co-operate with Presbyterian missions in what is now Malawi. Despite its original connections with the Free Church of Scotland, it operated ...

had tried but failed to become a Chartered company

A chartered company is an association with investors or shareholders that is Incorporation (business), incorporated and granted rights (often Monopoly, exclusive rights) by royal charter (or similar instrument of government) for the purpose of ...

with interests there and around the western shore of Lake Malawi

Lake Malawi, also known as Lake Nyasa in Tanzania and Lago Niassa in Mozambique, () is an African Great Lakes, African Great Lake and the southernmost lake in the East African Rift system, located between Malawi, Mozambique and Tanzania.

It is ...

.

However, in 1885–86, Alexandre de Serpa Pinto

Alexandre Alberto da Rocha de Serpa Pinto, Viscount of Serpa Pinto (aka Serpa Pinto; 20 April 184628 December 1900) was a Portuguese explorer of southern Africa and a colonial administrator.

Early life

Serpa Pinto was born at the Quinta das Po ...

had undertaken an expedition which reached Shire Highlands, which had failed to make any treaties of protection with the Yao chiefs west of Lake Malawi. To prevent possible Portuguese occupation, in November 1888, Johnston was appointed as Commissioner and Consul-general for the Mozambique and the Nyasa districts, and arrived in Blantyre

Blantyre is Malawi's centre of finance and commerce, and its second largest city, with a population of 800,264 . It is sometimes referred to as the commercial and industrial capital of Malawi as opposed to the political capital, Lilongwe. It is ...

in March 1889. On his way to take up his appointment, Johnston spent six weeks in Lisbon

Lisbon ( ; ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 567,131, as of 2023, within its administrative limits and 3,028,000 within the Lisbon Metropolitan Area, metropolis, as of 2025. Lisbon is mainlan ...

attempting to negotiate an acceptable agreement on Portuguese and British spheres of influence

In the field of international relations, a sphere of influence (SOI) is a spatial region or concept division over which a state or organization has a level of cultural, economic, military, or political exclusivity.

While there may be a formal a ...

in southeastern Africa. However, as the draft agreement did not expressly exclude the Shire Highlands

The Shire Highlands are a plateau in southern Malawi, located east of the Shire River. It is a major agricultural area and the most densely populated part of the country.

Geography

The highlands cover an area of roughly 7250 square kilometers. ...

from the Portuguese sphere, it was rejected by the Foreign Office

Foreign may refer to:

Government

* Foreign policy, how a country interacts with other countries

* Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in many countries

** Foreign Office, a department of the UK government

** Foreign office and foreign minister

* United ...

.

Among several pressing problems was the Karonga War

The name Karonga War is given to a number of armed clashes that took place between mid-1887 and mid-1889 near Karonga at the northern end of Lake Malawi in what is now Malawi between a Scottish trading concern called the African Lakes Company Lim ...

, a dispute between Swahili

Swahili may refer to:

* Swahili language, a Bantu language officially used in Tanzania, Kenya and Uganda and widely spoken in the African Great Lakes.

* Swahili people, an ethnic group in East Africa.

* Swahili culture, the culture of the Swahili p ...

traders in slaves and ivory with their Henga allies on one side and the African Lakes Trading Company and factions of the Ngonde people on the other which had broken out in 1887. As Johnston had no significant forces at that time, he agreed to a truce with the Swahili leaders in October 1889, but the Swahili traders did not adhere to its terms.

In late 1888 and early 1889, the Portuguese government sent two expeditions to make treaties of protection with local chiefs, one under Antonio Cardoso set off toward Lake Malawi, the other under Alexandre de Serpa Pinto

Alexandre Alberto da Rocha de Serpa Pinto, Viscount of Serpa Pinto (aka Serpa Pinto; 20 April 184628 December 1900) was a Portuguese explorer of southern Africa and a colonial administrator.

Early life

Serpa Pinto was born at the Quinta das Po ...

moved up the Shire valley. Between them, they made more than twenty treaties with chiefs in what is now Malawi. Johnston met Serpa Pinto in August 1889, east of the Ruo, and advised him not to cross the river, but Serpa Pinto disregarded this and crossed the river to Chiromo

Chiromo is a town in southern Malawi by the Shire River.

Name

The Nairobi suburb of Chiromo near Westlands, as well as University of Nairobi Chiromo Campus and Nairobi's Chiromo Road got their name from this town. Ewart Grogan saw the two ri ...

, now in Malawi. In September, following minor clashes between Serpa Pinto's force and local Africans, Johnston's deputy declared a Shire Highlands Protectorate, despite the contrary instructions. Johnston's proclamation of a further protectorate west of Lake Malawi, the Nyasaland Districts Protectorate, was endorsed by the Foreign Office in May 1891.

Johnston arrived in Chiromo, in the south of Nyasaland, on 16 July 1891. By that time, he had already selected a team of men who were to assist in forming the administration of the new protectorate. They included Alfred Sharpe

Sir Alfred Sharpe (19 May 1853 – 10 December 1935) was Commissioner and Consul-General for the British Central Africa Protectorate and first Governor of Nyasaland.

He trained as a solicitor but was in turn a planter and a professional hu ...

(Johnston's Deputy Commissioner), Bertram L. Sclater (surveyor, roadmaker, and Commandant of the Constabulary), Alexander Whyte

''For the British colonial administrator, see Alexander Frederick Whyte''

Rev Alexander Whyte D.D.,LL.D. (13 January 18366 January 1921) was a Scotland, Scottish Anglican divine, divine. He was Moderator of the General Assembly of the Free Chu ...

(a zoologist who was to discover several new species in Nyasaland), Cecil Montgomery Maguire (military commandant), Hugh Charlie Marshall (Customs Officer, Collector of Revenues and Postmaster for the Chiromo district), John Buchanan (an agriculturalist who had been in Nyasaland since 1876, and was appointed Vice Consul by Johnston), and others.

In 1891, Johnston only controlled a fraction of the Shire Highlands, itself a small part of the whole protectorate. He was provided with a small force of Indian troops in 1891, and began to train African soldiers and police. At first, Johnston used his small force in the south of the protectorate to suppress slave trading by Yao chiefs, who had established links with Swahili traders in ivory and slaves from the early 19th century. As the Yao people had no central authority, Johnston was able to defeat one group at a time, although this took until 1894, as he left the most powerful chief, Makanjira, until almost last, starting an amphibious operation against him in late 1893.

Before the British Central Africa Protectorate was proclaimed in May 1891, a number of European companies and settlers had made, or claimed to have made, treaties with local chiefs under which the land owned by the African communities that occupied it was transferred to the Europeans in exchange for protection and some trade goods. The African Lakes Company

The African Lakes Corporation plc was a British company originally set-up in 1877 by Scottish businessmen to co-operate with Presbyterian missions in what is now Malawi. Despite its original connections with the Free Church of Scotland, it operated ...

claimed more than 2.75 million acres in the north of the protectorate, some under treaties that claimed to transfer sovereignty

Sovereignty can generally be defined as supreme authority. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within a state as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the person, body or institution that has the ultimate au ...

to the company, and three others individuals claimed to have purchased large areas of land in the south. Eugene Sharrer

Eugene Charles Albert Sharrer was a British subject by naturalisation but of German descent, who was a leading entrepreneur in what is now Malawi for around fifteen years between his arrival in 1888 and his departure. He rapidly built-up commercia ...

claimed 363,034 acres, Alexander Low Bruce A. L. Bruce Estates was one of three largest owners of agricultural estates in colonial Nyasaland. Alexander Low Bruce, the son-in-law of David Livingstone, acquired a large estate at Magomero in the Shire Highlands of Nyasaland in 1893, together wi ...

claimed 176,000 acres, and John Buchanan and his brothers claimed a further 167,823 acres. These lands were purchased for trivial quantities of goods under agreements signed by chiefs with no understanding of English concepts of land tenure

In Common law#History, common law systems, land tenure, from the French verb "" means "to hold", is the legal regime in which land "owned" by an individual is possessed by someone else who is said to "hold" the land, based on an agreement betw ...

.

Johnston had the task of reviewing these land claims, and he began to do so in late 1892, as the proclamation of the protectorate had been followed by a wholesale land grab, with huge areas of land bought for trivial sums and some claims overlapping. He rejected any suggestion that treaties made before the protectorate was established could transfer sovereignty to individuals or companies, but accept that they could be evidence of land sales. Although Johnston accepted that the land belonged to its African communities, so their chiefs had no right to alienate it, he suggested that each community had given their chief this right. Despite having no legal training, he claimed that, as Commissioner, he was entitled to investigate these land sales and to issue Certificates of Claim registering freehold

Freehold may refer to:

In real estate

*Freehold (law), the tenure of property in fee simple

* Customary freehold, a form of feudal tenure of land in England

*Parson's freehold, where a Church of England rector or vicar of holds title to benefice ...

title to the European claimants. He rejected very few claims, despite the questionable evidence for several major ones. The existing African villages and farms were exempted from these sales, and the villagers were told that their homes and fields were not being alienated. Despite this, the concentration of much of the most fertile land in the Shire Highlands in the hands of European owners had profound economic consequences that lasted throughout the colonial period.

In April 1894, Johnston returned to England and was away for a year. He had quarrelled with Cecil Rhodes

Cecil John Rhodes ( ; 5 July 185326 March 1902) was an English-South African mining magnate and politician in southern Africa who served as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony from 1890 to 1896. He and his British South Africa Company founded th ...

, who had so far provided most of his funds, and during the first three years the administration had run up a deficit of £20,000. During his leave, Johnston managed to persuade the British Government to agree to take over the financing of the country. On his way back, he visited Egypt and India with a view to recruiting soldiers, and eventually arrived back in Nyasaland with a flotilla of boats, 202 Sikh soldiers, and more than 400 other men; 4,000 porters were recruited in the Shire Highlands to carry stores and equipment. Johnston reached Zomba on 3 May 1895.

Johnston visited Karonga in June 1895 to try to make a settlement, but the Swahili leaders refused either to meet him or to curtail their raiding activities, so Johnston decided on military action. In November 1895, Johnston embarked with a force of more than 400 Sikh and African riflemen, with artillery and machine guns on steamers, to Karonga

Karonga is a township in the Karonga District in Northern Region of Malawi. Located on the western shore of Lake Nyasa, it was established as a slaving centre sometime before 1877. As of 2018 estimates, Karonga has a population of 61,609. Th ...

and surrounded the traders' main stockaded town, bombarding it for two days and finally assaulting it on 4 December. The Swahili leader, Mlozi, was captured, given a cursory trial and hanged on 5 December, and between 200 and 300 of fighters and several hundred non-combatants were killed, many while attempting to surrender. Other Swahili stockades did not resist and were destroyed.

North-Eastern Rhodesia and Nyasaland

Johnston realised the strategic importance of Lake Tanganyika to the British, especially since the territory between the lake and the coast had becomeGerman East Africa

German East Africa (GEA; ) was a German colonial empire, German colony in the African Great Lakes region, which included present-day Burundi, Rwanda, the Tanzania mainland, and the Kionga Triangle, a small region later incorporated into Portugu ...

, forming a break of nearly in the chain of British colonies in the Cape to Cairo dream. However, the north end of Lake Tanganyika was only from British-controlled Uganda

Uganda, officially the Republic of Uganda, is a landlocked country in East Africa. It is bordered to the east by Kenya, to the north by South Sudan, to the west by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, to the south-west by Rwanda, and to the ...

, and so a British presence at the south end of the lake was a priority. Although the northern boundaries of North-Eastern Rhodesia and Nyasaland were eventually settled by negotiations between Britain, Germany. Portugal and the Congo Free State, Johnston ensured that British bomas were established (in addition to those in Nyasaland) east of Luapula-Mweru at Chiengi

Chiengi or is a historic colonial boma of the British Empire in central Africa and today is a settlement in the Luapula Province of Zambia, and headquarters of Chiengi District. Chiengi is in the north-east corner of Lake Mweru, and at the foo ...

and the Kalungwishi River

The Kalungwishi River flows west in northern Zambia into Lake Mweru. It is known for its waterfall

A waterfall is any point in a river or stream where water flows over a vertical drop or a series of steep drops. Waterfalls also occur where ...

, at the south end of Lake Tanganyika

Lake Tanganyika ( ; ) is an African Great Lakes, African Great Lake. It is the world's List of lakes by volume, second-largest freshwater lake by volume and the List of lakes by depth, second deepest, in both cases after Lake Baikal in Siberia. ...

at Abercorn

Abercorn ( Gaelic: ''Obar Chùirnidh'', Old English: ''Æbbercurnig'') is a village and civil parish in West Lothian, Scotland. Close to the south coast of the Firth of Forth, the village is around west of South Queensferry. The parish had a ...

, and at Fort Jameson between Mozambique

Mozambique, officially the Republic of Mozambique, is a country located in Southeast Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi and Zambia to the northwest, Zimbabwe to the west, and Eswatini and South Afr ...

and the Luangwa valley

The Luangwa River is one of the major tributaries of the Zambezi River, and one of the four biggest rivers of Zambia. The river generally floods in the rainy season (December to March) and then falls considerably in the dry season. It is one of ...

to demonstrate effective occupation.

Until 1899, Johnston had administrative control of the territory which became North-Eastern Rhodesia

North-Eastern Rhodesia was a British protectorate in south central Africa formed in 1900.North-Eastern Rhodesia Order in Council, 1900 The protectorate was administered under charter by the British South Africa Company. It was one of what were ...

(the north-eastern half of today's Zambia

Zambia, officially the Republic of Zambia, is a landlocked country at the crossroads of Central Africa, Central, Southern Africa, Southern and East Africa. It is typically referred to being in South-Central Africa or Southern Africa. It is bor ...

), and he helped to set up and oversee the British South Africa Company's administration in that area. North-Eastern Rhodesia was little developed in this period, being regarded principally as a labour reserve, with only a handful of company administrators.

Despite having missed out in Katanga, altogether he helped to consolidate an area of nearly half a million square kilometres into the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

– nearly , or twice the area of the United Kingdom in 2009 – lying between the lower Luangwa River

The Luangwa River is one of the major Tributary, tributaries of the Zambezi River, and one of the four biggest rivers of Zambia. The river generally floods in the rainy season (December to March) and then falls considerably in the dry season. I ...

valley and lakes Nyasa, Tanganyika, and Mweru.

Later years

In 1896, in recognition of this achievement, Johnston was appointed

In 1896, in recognition of this achievement, Johnston was appointed Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by King George I of Great Britain, George I on 18 May 1725. Recipients of the Order are usually senior British Armed Forces, military officers or senior Civil Service ...

(KCB), but afflicted by tropical fevers, he transferred to Tunis

Tunis (, ') is the capital city, capital and largest city of Tunisia. The greater metropolitan area of Tunis, often referred to as "Grand Tunis", has about 2,700,000 inhabitants. , it is the third-largest city in the Maghreb region (after Casabl ...

as consul-general

A consul is an official representative of a government who resides in a foreign country to assist and protect citizens of the consul's country, and to promote and facilitate commercial and diplomatic relations between the two countries.

A consu ...

. In the same year, he had married the Hon. Winifred Mary Irby, daughter of Florance George Henry Irby, fifth Baron Boston

Baron Boston, of Boston in the County of Lincoln, is a title in the Peerage of Great Britain. It was created in 1761 for the court official and former Member of Parliament, Sir William Irby, 2nd Baronet. He had earlier represented Launceston ...

.

In 1899, Sir Harry was sent to Uganda

Uganda, officially the Republic of Uganda, is a landlocked country in East Africa. It is bordered to the east by Kenya, to the north by South Sudan, to the west by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, to the south-west by Rwanda, and to the ...

as special commissioner to reorganize the administration of that protectorate after the suppression of the mutiny of the Sudanese soldiers and to end an ongoing war with Unyoro. He improved the colonial administration, and concluded the Buganda Agreement of 1900, dividing the land between the UK and the chiefs. For his services in Uganda, he received the Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George

The Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George is a British order of chivalry founded on 28 April 1818 by George, Prince of Wales (the future King George IV), while he was acting as prince regent for his father, King George III ...

(GCMG) in the King's Birthday Honours list in November 1901. Also in 1901, Johnston was the first recipient of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society

The Royal Scottish Geographical Society (RSGS) is an educational charity based in Perth, Scotland, founded in 1884. The purpose of the society is to advance the subject of geography worldwide, inspire people to learn more about the world around ...

's Livingstone Medal, and in the following year he was appointed a member of the council of the Zoological Society of London

The Zoological Society of London (ZSL) is a charity and organization devoted to the worldwide animal conservation, conservation of animals and their habitat conservation, habitats. It was founded in 1826. Since 1828, it has maintained London Zo ...

. He received the honorary degree ''Doctor of Science

A Doctor of Science (; most commonly abbreviated DSc or ScD) is a science doctorate awarded in a number of countries throughout the world.

Africa

Algeria and Morocco

In Algeria, Morocco, Libya and Tunisia, all universities accredited by the s ...

'' (D.Sc.) from the University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

in May 1902. The Royal Geographical Society

The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers), often shortened to RGS, is a learned society and professional body for geography based in the United Kingdom. Founded in 1830 for the advancement of geographical scien ...

awarded him their 1904 Founder's Medal

The Founder's Medal is a medal awarded annually by the Royal Geographical Society, upon approval of the Sovereign of the United Kingdom, to individuals for "the encouragement and promotion of geographical science and discovery".

Foundation

From ...

for his services to African exploration.

In 1902, his wife gave birth to twin boys, but neither survived more than a few hours, and the couple had no more children. Johnston's sister, Mabel Johnston, married Arnold Dolmetsch

Eugène Arnold Dolmetsch (24 February 185828 February 1940), was a French-born musician and instrument maker who spent much of his working life in England and established an instrument-making workshop in Haslemere, Surrey. He was a leading figu ...

, an instrument maker and member of the Bloomsbury set

The Bloomsbury Group was a group of associated British writers, intellectuals, philosophers and artists in the early 20th century. Among the people involved in the group were Virginia Woolf, John Maynard Keynes, E. M. Forster, Vanessa Bell, ...

, in 1903.

In 1903

Events January

* January 1 – Edward VII is proclaimed Emperor of India.

* January 10 – The Aceh Sultanate was fully annexed by the Dutch forces, deposing the last sultan, marking the end of the Aceh War that have lasted for al ...

and in 1906

Events

January–February

* January 12 – Persian Constitutional Revolution: A nationalistic coalition of merchants, religious leaders and intellectuals in Persia forces the shah Mozaffar ad-Din Shah Qajar to grant a constitution, ...

, Johnston stood for parliament for the Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world.

The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left. For example, while the political systems ...

, but was unsuccessful on both occasions. In 1906, the Johnstons moved to the hamlet of Poling, near Arundel

Arundel ( ) is a market town and civil parish in the Arun District of the South Downs, West Sussex, England.

The much-conserved town has a medieval castle and Roman Catholic cathedral. Arundel has a museum and comes second behind much la ...

in West Sussex, where Johnston largely concentrated on his literary endeavours. He took to writing novels, which were frequently short-lived, while his accounts of his own voyages through central Africa were rather more enduring.

Speaker at David Livingstone Centenary event in 1913

At the event in March 1913 in theRoyal Albert Hall

The Royal Albert Hall is a concert hall on the northern edge of South Kensington, London, England. It has a seating capacity of 5,272.

Since the hall's opening by Queen Victoria in 1871, the world's leading artists from many performance genres ...

celebrating the centenary of the birth of David Livingstone

David Livingstone (; 19 March 1813 – 1 May 1873) was a Scottish physician, Congregationalist, pioneer Christian missionary with the London Missionary Society, and an explorer in Africa. Livingstone was married to Mary Moffat Livings ...

, Johnston expressed his feelings about what he termed the "inadequate consideration" shown to Livingstone during his lifetime and the "stupidity" preventing the piblication of his journals.

Illness and death

Johnston suffered two strokes in 1925, from which he became partially paralysed and never recovered, dying two years later in 1927 at Woodsetts House nearWorksop

Worksop ( ) is a market town in the Bassetlaw District in Nottinghamshire, England. It is located south of Doncaster, south-east of Sheffield and north of Nottingham. Located close to Nottinghamshire's borders with South Yorkshire and Derbys ...

in Nottinghamshire. He was buried in the churchyard of St Nicholas, Poling, West Sussex, where there is a commemorative wall plaque within the nave of the church designed and cut by the Arts and Crafts

The Arts and Crafts movement was an international trend in the Decorative arts, decorative and fine arts that developed earliest and most fully in the British Isles and subsequently spread across the British Empire and to the rest of Europe and ...

sculptor and typeface designer Eric Gill

Arthur Eric Rowton Gill (22 February 1882 – 17 November 1940) was an English sculptor, letter cutter, typeface designer, and printmaker. Although the ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' describes Gill as "the greatest artist-craftsma ...

who lived in nearby Ditchling

Ditchling is a village and civil parish in the Lewes (district), Lewes District of East Sussex, England. The village is contained within the boundaries of the South Downs National Park; the order confirming the establishment of the park was sign ...

.

Legacy

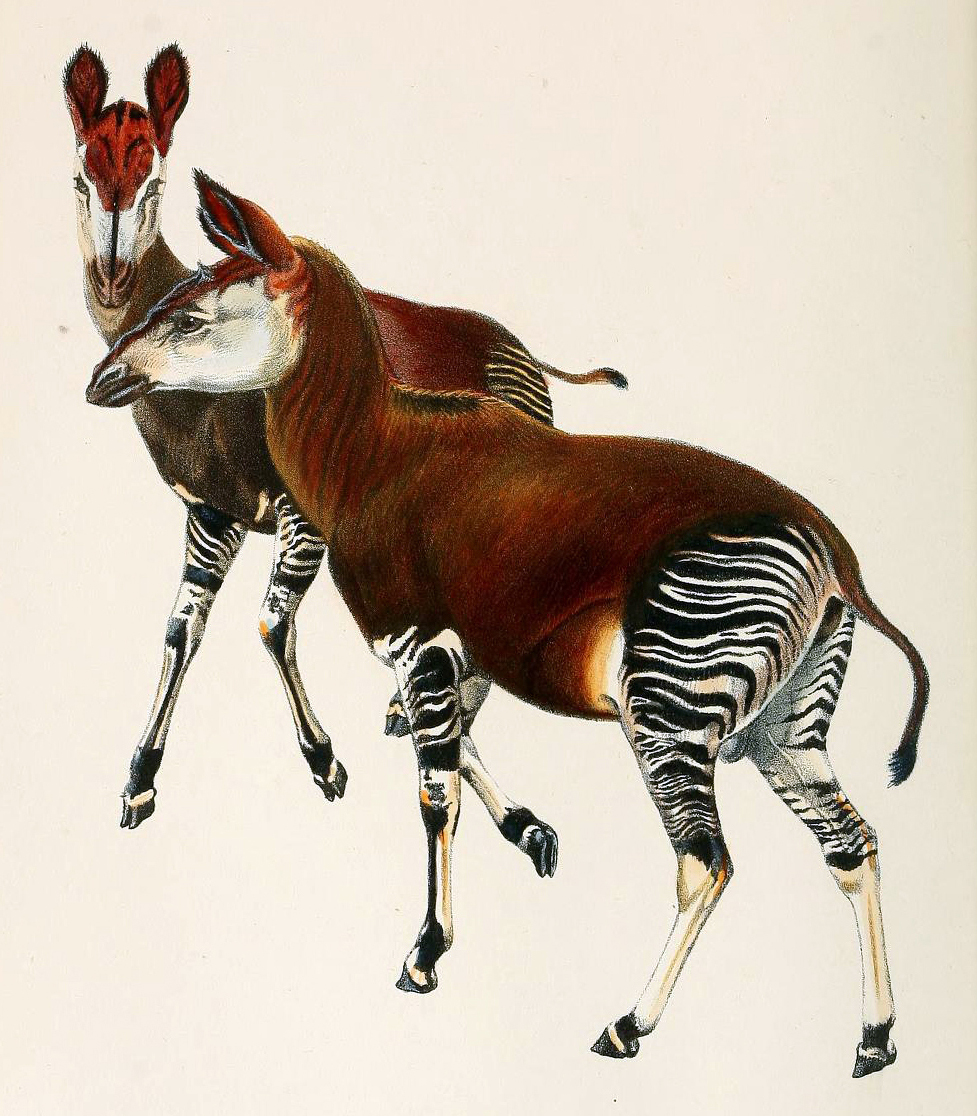

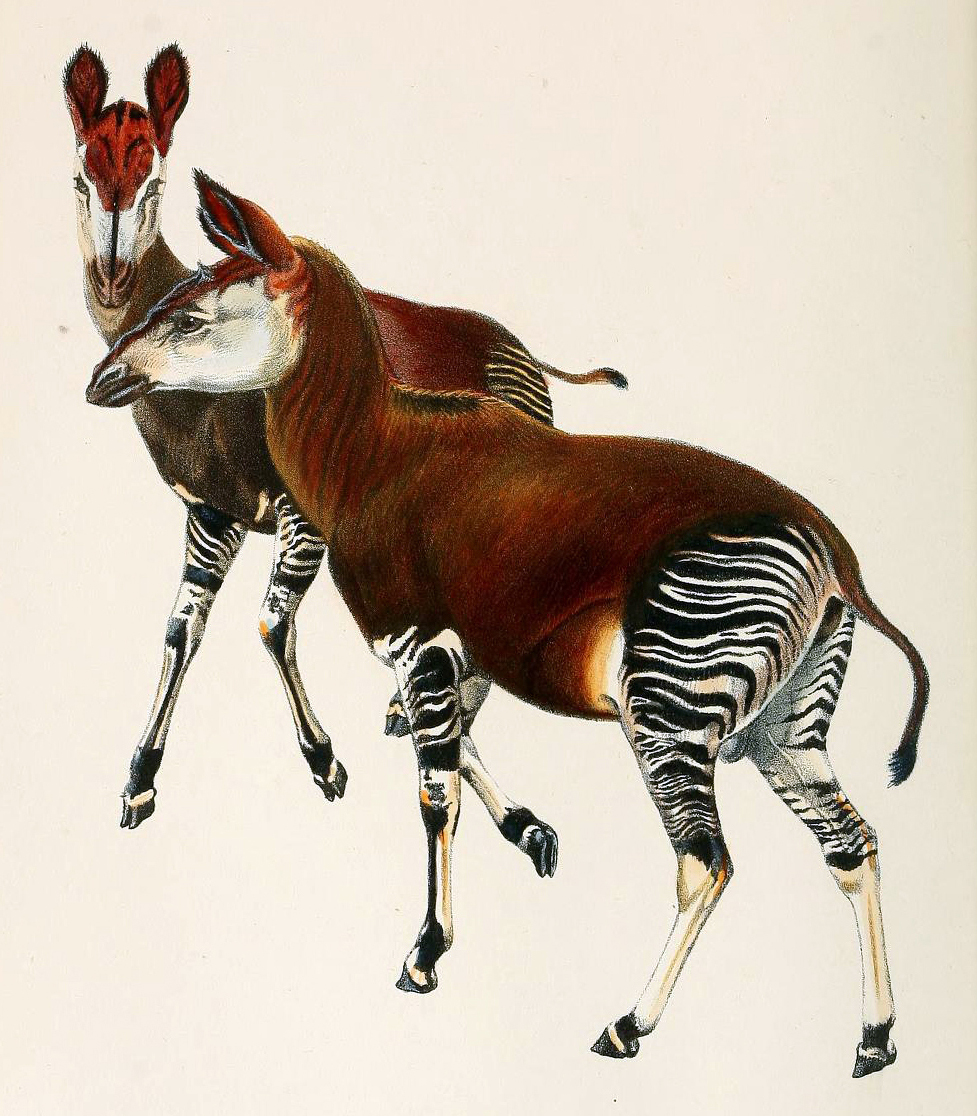

Harry Johnston is commemorated in the scientific names of theokapi

The okapi (; ''Okapia johnstoni''), also known as the forest giraffe, Congolese giraffe and zebra giraffe, is an artiodactyl mammal that is endemic to the northeast Democratic Republic of the Congo in central Africa. However, non-invasive gen ...

, ''Okapia johnstoni'', and of two species of African lizards, '' Trioceros johnstoni'' and '' Latastia johnstonii''.

The falls at Mambidima on the Luapula River

The Luapula River is a north-flowing river of central Africa, within the Congo River watershed. It rises in the wetlands of Lake Bangweulu (Zambia), which are fed by the Chambeshi River. The Luapula flows west then north, marking the border betw ...

were named '' Johnston Falls'' by the British in his honour.

Sir Harry Johnston Primary school in Zomba, Malawi is also named after him.

Prominent Bengali author Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay

Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay (; 12 September 1894 – 1 November 1950) was a Bengali novelist and short story writer of Indian nationality. His best known works are the autobiographical novel ''Pather Panchali'' (''Song of the Road''), '' Apar ...

mentioned the influence of Sir H. H. Johnston's works, one of many, in helping him portray scenes convincingly in his famous Bengali adventure novel Chander Pahar

''Chander Pahar'' () is a Bengali language, Bengali adventure novel written by Bibhutibhushan Bandopadhyay and published in 1937. The novel follows the adventures of a young Bengali people, Bengali man in the forests of Africa. The novel is o ...

.

Books

* ''The River Congo'' (1884) * ''The Kilima-Njaro Expedition'' (1886) * ''The History of a Slave'' (1889)''British Central Africa''

(1897) * ''A History of the Colonization of Africa by Alien Races'' (1899) * ''The Uganda Protectorate'' (1902) * ''The Living Races of Mankind'' (1902). * ''The Nile Quest: The Story of Exploration'' (190

* ''Liberia'' (1907) * ''

George Grenfell

George Grenfell (21 August 1849, in Sancreed, Cornwall – 1 July 1906, in Basoko, Congo Free State (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo) was a Cornish missionary and explorer.

Early years

Grenfell was born at Sancreed, near Penza ...

and the Congo'' (1908)

* '' The Negro in the New World'' (1910)

* ''The Opening Up of Africa''(1911)(London: Williams & Norgate* ''Phonetic Spelling'' (1913

online

*''Pioneers in India''] (1913

* ''A Comparative Study of the Bantu and Semi-Bantu Languages'' (1919, 1922)

online

* ''The Gay-Dombeys'' (1919) – a sequel to

Dombey and Son

''Dombey and Son'' is a novel by English author Charles Dickens. It follows the fortunes of a shipping firm owner, who is frustrated at the lack of a son to follow him in his footsteps; he initially rejects his daughter's love before eventual ...

by Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English novelist, journalist, short story writer and Social criticism, social critic. He created some of literature's best-known fictional characters, and is regarded by ...

* ''Mrs. Warren's Daughter'' (1920) —a sequel to Mrs. Warren's Profession

''Mrs. Warren's Profession'' is a play written by George Bernard Shaw in 1893, and first performed in London in 1902. It is one of the three plays Shaw published as ''Plays Unpleasant'' in 1898, alongside ''The Philanderer'' and '' Widowers' H ...

by George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from the 188 ...

* ''The Backward Peoples and Our Relations with Them'' (1920)

*''The Man Who Did the Right Thing'' (1921) – nove* ''The Veneerings'' (1922) – a sequel to

Our Mutual Friend

''Our Mutual Friend'', published in 1864–1865, is the last novel completed by English author Charles Dickens and is one of his most sophisticated works, combining savage satire with social analysis. It centres on, in the words of critic J. ...

by Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English novelist, journalist, short story writer and Social criticism, social critic. He created some of literature's best-known fictional characters, and is regarded by ...

*''The Story of my Life'' (1923) – autobiograph* Manuscripts of collected vocabularies of Sir Harry Hamilton Johnston are held by SOAS University of London, SOAS Archives.

References

Sources

* Thomas Pakenham, ''The Scramble for Africa

The Scramble for Africa was the invasion, conquest, and colonisation of most of Africa by seven Western European powers driven by the Second Industrial Revolution during the late 19th century and early 20th century in the era of "New Imperia ...

'', 1991.

* Roland Oliver

Roland Anthony Oliver Fellow of the British Academy, FBA (30 March 1923 – 9 February 2014) was an Indian-born English academic and Emeritus Professor of African history at the University of London.

Throughout a long career he was an eminent ...

, ''Sir Harry Johnston and the Scramble for Africa'', 1958.

* James A. Casada, ''Sir Harry H. Johnston: A Bio-Bibliographical Study'', 1977.

External links

*Full text of Johnston's book ''British Central Africa'' (1897).

(text only)

Full text of Johnston's book ''British Central Africa'' (1897).

(facsimile) * * * *Th

International Primary School

which bears Sir Harry Johnston's name was founded in the early 1950s in

Zomba, Malawi

Zomba is a city in southern Malawi, in the Shire Highlands. It is the former capital city of Malawi.

It was the capital of first British Central Africa and then Nyasaland Protectorate before the establishment of Malawi in 1964. It was also t ...

*

{{DEFAULTSORT:Johnston, Harry

1858 births

1927 deaths

Alumni of King's College London

British expatriates in Angola

British expatriates in British Nigeria

British expatriates in Malawi

British expatriates in Mozambique

British expatriates in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

British expatriates in Tunisia

British expatriates in Zambia

19th-century British explorers

British explorers of Africa

Knights Commander of the Order of the Bath

Knights Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George

Liberal Party (UK) parliamentary candidates

People from Arun District

it:Harry Johnston