HMAS Australia (1927) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

HMAS ''Australia'' (I84/D84/C01) was a County-class heavy cruiser of the

''Australia'' was designed to carry a single

''Australia'' was designed to carry a single

When the

When the

After returning, ''Australia'' spent the remainder of 1936 in the vicinity of Sydney and

After returning, ''Australia'' spent the remainder of 1936 in the vicinity of Sydney and

Royal Australian Navy

The Royal Australian Navy (RAN) is the principal naval force of the Australian Defence Force (ADF). The professional head of the RAN is Chief of Navy (CN) Vice Admiral Mark Hammond AM, RAN. CN is also jointly responsible to the Minister of ...

(RAN). One of two ''Kent''-subclass ships ordered for the RAN in 1924, ''Australia'' was laid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one ...

in Scotland in 1925, and entered service in 1928. Apart from an exchange deployment to the Mediterranean from 1934 to 1936, during which she became involved in the planned British response to the Abyssinia Crisis

The Abyssinia Crisis (; ) was an international crisis in 1935 that originated in what was called the Walwal incident during the ongoing conflict between the Kingdom of Italy and the Empire of Ethiopia (then commonly known as "Abyssinia"). The Le ...

, ''Australia'' operated in local and South-West Pacific waters until World War II began.

The cruiser remained near Australia until mid-1940, when she was deployed for duties in the eastern Atlantic, including hunts for German ships and participation in Operation Menace

The Battle of Dakar, also known as Operation Menace, was an unsuccessful attempt in September 1940 by the Allies of World War II, Allies to capture the strategic port of Dakar in French West Africa (modern-day Senegal). It was hoped that the succ ...

. During 1941, ''Australia'' operated in home and Indian Ocean waters, but was reassigned as flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the f ...

of the ANZAC Squadron

The ANZAC Squadron, also called the ''Allied Naval Squadron'', was an Allied naval warship task force which was tasked with defending northeast Australia and surrounding area in early 1942 during the Pacific Campaign of World War II. The squad ...

in early 1942. As part of this force (which was later redesignated Task Force 44

Task Force 44 was an Allied naval task force during the Pacific Campaign of World War II. The task force consisted of warships from the United States Navy and the Royal Australian Navy (RAN). It was generally assigned as a striking force to ...

, then Task Force 74), ''Australia'' operated in support of United States naval and amphibious operations throughout South-East Asia until the start of 1945, including involvement in the battles at the Coral Sea and Savo Island

Savo Island is an island in Solomon Islands in the southwest South Pacific ocean. Administratively, Savo Island is a part of the Central Province of the Solomon Islands. It is about from the capital Honiara. The principal village is Alialia, i ...

, the amphibious landings at Guadalcanal

Guadalcanal (; indigenous name: ''Isatabu'') is the principal island in Guadalcanal Province of Solomon Islands, located in the south-western Pacific, northeast of Australia. It is the largest island in the Solomon Islands by area, and the se ...

and Leyte Gulf

Leyte Gulf is a gulf in the Eastern Visayan region in the Philippines. The bay is part of the Philippine Sea of the Pacific Ocean, and is bounded by two islands; Samar in the north and Leyte in the west. On the south of the bay is Mindana ...

, and numerous actions during the New Guinea campaign. She was forced to withdraw following a series of kamikaze

, officially , were a part of the Japanese Special Attack Units of military aviators who flew suicide attacks for the Empire of Japan against Allied naval vessels in the closing stages of the Pacific campaign of World War II, intending to ...

attacks during the invasion of Lingayen Gulf

The Invasion of Lingayen Gulf ( fil, Paglusob sa Golpo ng Lingayen), 6–9 January 1945, was an Allies of World War II, Allied Amphibious warfare, amphibious operation in the Commonwealth of the Philippines, Philippines during World War II. In t ...

. The prioritisation of shipyard work in Australia for British Pacific Fleet

The British Pacific Fleet (BPF) was a Royal Navy formation that saw action against Japan during the Second World War. The fleet was composed of empire naval vessels. The BPF formally came into being on 22 November 1944 from the remaining ships ...

vessels saw the Australian cruiser sail to England for repairs, where she was at the end of the war.

During the late 1940s, ''Australia'' served with the British Commonwealth Occupation Force

The British Commonwealth Occupation Force (BCOF) was the British Commonwealth taskforce consisting of Australian, British, Indian and New Zealand military forces in occupied Japan, from 1946 until the end of occupation in 1952.

At its pea ...

in Japan, and participated in several port visits to other nations, before being retasked as a training ship in 1950. The cruiser was decommissioned in 1954, and sold for scrapping

Scrap consists of recyclable materials, usually metals, left over from product manufacturing and consumption, such as parts of vehicles, building supplies, and surplus materials. Unlike waste, scrap has monetary value, especially recovered me ...

in 1955.

Design

''Australia'' was one of seven warships built to the ''Kent'' design of County-class heavy cruiser, which were based on design work byEustace Tennyson-D'Eyncourt

Sir Eustace Henry William Tennyson d'Eyncourt, 1st Baronet (1 April 1868 – 1 February 1951) was a British naval architect and engineer. As Director of Naval Construction for the Royal Navy, 1912–1924, he was responsible for the design a ...

. She was designed with a standard displacement

Displacement may refer to:

Physical sciences

Mathematics and Physics

*Displacement (geometry), is the difference between the final and initial position of a point trajectory (for instance, the center of mass of a moving object). The actual path ...

of 10,000 tons, a length between perpendiculars

Length between perpendiculars (often abbreviated as p/p, p.p., pp, LPP, LBP or Length BPP) is the length of a ship along the summer load line from the forward surface of the stem, or main bow perpendicular member, to the after surface of the stern ...

of , a length overall of , a beam of , and a maximum draught of .Cassells, ''The Capital Ships'', p. 21

The propulsion machinery consisted of eight Yarrow superheated boilers feeding Curtis high-pressure and Parsons low-pressure geared turbines. This delivered up to 80,000 shaft horsepower to the cruiser's four three-bladed propellers. The cruiser's top speed was , with a range of , while her economical range and cruising speed was at .

The ship's company consisted of 64 officers and 678 sailors in 1930; this dropped to 45 officers and 654 sailors from 1937 to 1941. While operating as flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the f ...

, ''Australia''s company was 710. During wartime, the ship's company increased to 815.

Armament and armour

''Australia'' was designed with eight guns in four twin turrets ('A' and 'B' forward, 'X' and 'Y' aft) as primary armament, with 150 shells per gun.Gillett, ''Australian and New Zealand Warships, 1914–1945'', p. 86 Secondary armament consisted of four guns in four single mounts, with 200 shells per gun, and four 2-pounder pom-poms for anti-aircraft defence, with 1,000 rounds each. A mixture of .303-inch machine guns () were carried for close defence work: initially this consisted of fourVickers machine gun

The Vickers machine gun or Vickers gun is a water-cooled .303 British (7.7 mm) machine gun produced by Vickers Limited, originally for the British Army. The gun was operated by a three-man crew but typically required more men to move and ...

s and twelve Lewis machine guns, although four Lewis guns were later removed. Two sets of quadruple torpedo tube

A torpedo tube is a cylindrical device for launching torpedoes.

There are two main types of torpedo tube: underwater tubes fitted to submarines and some surface ships, and deck-mounted units (also referred to as torpedo launchers) installed abo ...

s were fitted. Four 3-pounder quick-firing Hotchkiss guns were used as saluting gun

A salute is usually a formal hand gesture or other action used to display respect in military situations. Salutes are primarily associated with the military and law enforcement, but many civilian organizations, such as Girl Guides, Boy Sco ...

s. During her 1939 modernisation, the four single guns were replaced by four twin Mark XVI guns. The torpedo tubes were removed in 1942, and the 'X' turret was taken off in 1945.

The close-range anti-aircraft armament of the ship fluctuated during her career. During the mid-1930s, two quadruple machine gun mounts were installed to supplement the weapons.Bastock, ''Australia's Ships of War'', p. 101 These were replaced in late 1943 by seven single 20mm Oerlikon

The Oerlikon 20 mm cannon is a series of autocannons, based on an original German Becker Type M2 20 mm cannon design that appeared very early in World War I. It was widely produced by Oerlikon Contraves and others, with various models emplo ...

s. By early 1944, all seven Oerlikons had been upgraded to double mountings. These were in turn replaced by eight single 40 mm Bofors Bofors 40 mm gun is a name or designation given to two models of 40 mm calibre anti-aircraft guns designed and developed by the Swedish company Bofors:

* Bofors 40 mm L/60 gun - developed in the 1930s, widely used in World War II and into the 199 ...

guns in 1945.

''Australia'' was designed to carry a single

''Australia'' was designed to carry a single amphibious aircraft

An amphibious aircraft or amphibian is an aircraft (typically fixed-wing) that can take off and land on both solid ground and water, though amphibious helicopters do exist as well. Fixed-wing amphibious aircraft are seaplanes ( flying boat ...

: a Supermarine Seagull III

The Supermarine Seagull was a amphibian biplane flying boat designed and produced by the British aircraft manufacturer Supermarine. It was developed from the experimental Supermarine Seal II.

Development of the Seagull started during 1920; it ...

aircraft, which was replaced in 1936 by a Supermarine Walrus

The Supermarine Walrus (originally designated the Supermarine Seagull V) was a British single-engine amphibious biplane reconnaissance aircraft designed by R. J. Mitchell and manufactured by Supermarine at Woolston, Southampton.

The Walrus ...

. Both aircraft were operated by the Royal Australian Air Force

"Through Adversity to the Stars"

, colours =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries = RAAF Anniversary Commemoration ...

's Fleet Co-operation Unit; initially by No. 101 Flight RAAF, which was expanded in 1936 to form No. 5 Squadron RAAF

No. 5 Squadron was a Royal Australian Air Force training, army co-operation and helicopter squadron. The squadron was formed in 1917 as a training unit of the Australian Flying Corps in Britain, readying pilots for service on the Western Front ...

, then renumbered in 1939 to No. 9 Squadron RAAF

No. 9 Squadron was a unit of the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF). The squadron was formed in early 1939 and saw active service in World War II as a fleet co-operation unit providing aircrews for seaplanes operating off Royal Australian Navy ...

. As the aircraft catapult

An aircraft catapult is a device used to allow aircraft to take off from a very limited amount of space, such as the deck of a vessel, but can also be installed on land-based runways in rare cases. It is now most commonly used on aircraft carrier ...

was not installed until September 1935, the Seagull was initially lowered into the water by the ship's recovery crane to launch under its own power. The catapult and Walrus were removed in October 1944.

Armour aboard ''Australia'' was initially limited to an armour deck over the machinery spaces and magazines, ranging from in thickness. Armour plate was also fitted to the turrets (up to thick) and the conning tower ( thick). Anti-torpedo bulge

The anti-torpedo bulge (also known as an anti-torpedo blister) is a form of defence against naval torpedoes occasionally employed in warship construction in the period between the First and Second World Wars. It involved fitting (or retrofitti ...

s were also fitted. During 1938 and 1939, belt armour

Belt armor is a layer of heavy metal armor plated onto or within the outer hulls of warships, typically on battleships, battlecruisers and cruisers, and aircraft carriers.

The belt armor is designed to prevent projectiles from penetrating to ...

up to thick was fitted along the waterline to provide additional protection to the propulsion machinery.

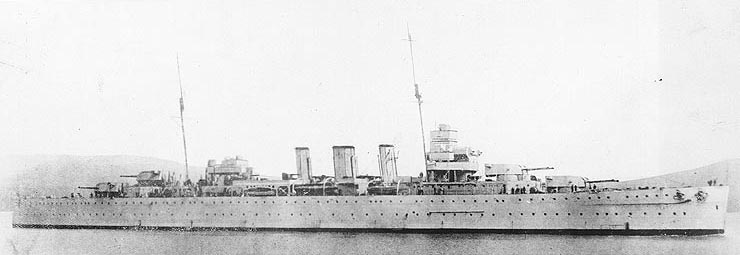

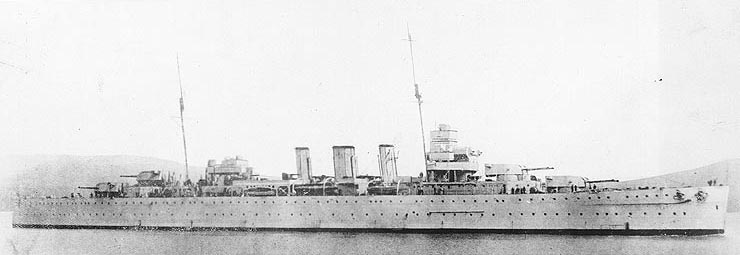

Acquisition and construction

''Australia'' was ordered in 1924 as part of a five-year plan to develop the RAN. She was laid down byJohn Brown and Company

John Brown and Company of Clydebank was a Scottish marine engineering and shipbuilding firm. It built many notable and world-famous ships including , , , , , and the ''Queen Elizabeth 2''.

At its height, from 1900 to the 1950s, it was one of ...

at their shipyard in Clydebank

Clydebank ( gd, Bruach Chluaidh) is a town in West Dunbartonshire, Scotland. Situated on the north bank of the River Clyde, it borders the village of Old Kilpatrick (with Bowling and Milton beyond) to the west, and the Yoker and Drumchapel areas ...

, Scotland, on 26 August 1925.Cassells, ''The Capital Ships'', p. 22 The cruiser was launched on 17 March 1927 by Dame Mary Cook

Dame Mary Cook (née Turner; – 24 September 1950) was the wife of Australian Prime Minister, Sir Joseph Cook.

Biography

Early years

Mary Turner was 22 years old and had been a schoolteacher for eight years when she married Joseph Cook in 188 ...

, wife of Sir Joseph Cook

Sir Joseph Cook, (7 December 1860 – 30 July 1947) was an Australian politician who served as the sixth Prime Minister of Australia, in office from 1913 to 1914. He was the leader of the Liberal Party from 1913 to 1917, after earlier servin ...

, the Australian High Commissioner to the United Kingdom and former Australian Prime Minister

The prime minister of Australia is the head of government of the Commonwealth of Australia. The prime minister heads the executive branch of the federal government of Australia and is also accountable to federal parliament under the principle ...

.

The cruiser was initially fitted with short exhaust funnels, but during sea trial

A sea trial is the testing phase of a watercraft (including boats, ships, and submarines). It is also referred to as a " shakedown cruise" by many naval personnel. It is usually the last phase of construction and takes place on open water, and ...

s of ''Australia'' and other ''Kent''-class ships, it was found that smoke from the boilers was affecting the bridge and aft control position.Bastock, ''Australia's Ships of War'', p. 102 The funnel design was subsequently lengthened by ; the taller funnels on the under-construction were later switched over to ''Australia'' as she neared completion.

When the

When the ship's badge

Naval heraldry is a form of identification used by naval vessels from the end of the 19th century onwards, after distinguishing features such as figureheads and gilding were discouraged or banned by several navies.

Naval heraldry commonly takes t ...

came up for consideration on 26 December 1926, both Richard Lane-Poole

Vice Admiral Sir Richard Hayden Owen Lane-Poole (1 April 1883 – 25 March 1971) was a senior officer in the Royal Navy. He was the Rear Admiral Commanding His Majesty's Australian Squadron from 1936 to 1938.

Naval career

Lane-Poole was born ...

, commander of the Australian Squadron, and William Napier, First Naval Member of the Australian Commonwealth Naval Board

The Australian Commonwealth Naval Board was the governing authority over the Royal Australian Navy from its inception and through World Wars I and II. The board was established on 1 March 1911 and consisted of civilian members of the Australian ...

disapproved of the design previously carried by the battlecruiser , and requested new designs.Cassells, ''The Capital Ships'', p. 26 On 26 July 1927, it was decided to use the Coat of arms of Australia as the basis for the badge, with the shield

A shield is a piece of personal armour held in the hand, which may or may not be strapped to the wrist or forearm. Shields are used to intercept specific attacks, whether from close-ranged weaponry or projectiles such as arrows, by means of ...

bearing the symbols of the six states and the Federation Star

The Commonwealth Star (also known as the Federation Star, the Seven Point Star, or the Star of Federation) is a seven-pointed star symbolising the Federation of Australia which came into force on 1 January 1901.

Six points of the Star represent ...

crest

Crest or CREST may refer to:

Buildings

* The Crest (Huntington, New York), a historic house in Suffolk County, New York

*"The Crest", an alternate name for 63 Wall Street, in Manhattan, New York

* Crest Castle (Château Du Crest), Jussy, Switze ...

depicted in the design.Cassells, ''The Capital Ships'', p. 27 No motto was given to the ship, but when the badge design was updated prior to the planned 1983 acquisition of the British aircraft carrier (which was to be renamed HMAS ''Australia''), the motto from the battlecruiser, "Endeavour", was added.

The warship was commissioned into the RAN on 24 April 1928. Construction of ''Australia'' cost 1.9 million pounds, very close to the estimated cost. ''Australia'' and sister ship (also constructed by John Brown) were the only County-class vessels built in Scotland.

Operational history

Early career

''Australia'' left Portsmouth for her namesake country on 3 August 1928 after completingsea trial

A sea trial is the testing phase of a watercraft (including boats, ships, and submarines). It is also referred to as a " shakedown cruise" by many naval personnel. It is usually the last phase of construction and takes place on open water, and ...

s.''HMAS Australia (II)'', Royal Australian Navy During the voyage, the cruiser visited Canada, the United States of America, several Pacific islands, and New Zealand before she reached Sydney on 23 October. Following the start of the Great Depression, the RAN fleet was downscaled in 1930 to three active ships (''Australia'', ''Canberra'', and seaplane carrier ) while one of the S-class destroyers would remain active at a time, with a reduced ship's company. In 1932, ''Australia'' cruised to the Pacific islands. In 1933, she visited New Zealand.

On 10 December 1934, ''Australia'' was sent to the United Kingdom on exchange duty, with the Duke of Gloucester

Duke of Gloucester () is a British royal title (after Gloucester), often conferred on one of the sons of the reigning monarch. The first four creations were in the Peerage of England and the last in the Peerage of the United Kingdom; the curre ...

, who had visited Victoria

Victoria most commonly refers to:

* Victoria (Australia), a state of the Commonwealth of Australia

* Victoria, British Columbia, provincial capital of British Columbia, Canada

* Victoria (mythology), Roman goddess of Victory

* Victoria, Seychelle ...

for the state's centenary of foundation the month previous, aboard. The cruiser reached Portsmouth on 28 March 1935, and was assigned to the Mediterranean Fleet

The British Mediterranean Fleet, also known as the Mediterranean Station, was a formation of the Royal Navy. The Fleet was one of the most prestigious commands in the navy for the majority of its history, defending the vital sea link between t ...

. ''Australia'' returned to England from 21 June to 12 September to represent Australia at King George V's Silver Jubilee

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother Que ...

Naval Review

A fleet review or naval review is an event where a gathering of ships from a particular navy is paraded and reviewed by an incumbent head of state and/or other official civilian and military dignitaries. A number of national navies continue to ...

at Spithead.Bastock, ''Australia's Ships of War'', p. 103 Following the outbreak of the Abyssinian crisis

The Abyssinia Crisis (; ) was an international crisis in 1935 that originated in what was called the Walwal incident during the ongoing conflict between the Kingdom of Italy and the Empire of Ethiopia (then commonly known as "Abyssinia"). The Leag ...

, ''Australia'' began to train for a potential war.Sears, in Stevens, ''The Royal Australian Navy'', p. 95 ''Australia''s initial role in any British assault on the Italian Navy was to cover the withdrawal of the aircraft carrier after an air attack on the base at Taranto

Taranto (, also ; ; nap, label=Tarantino dialect, Tarantino, Tarde; Latin: Tarentum; Old Italian: ''Tarento''; Ancient Greek: Τάρᾱς) is a coastal city in Apulia, Southern Italy. It is the capital of the Province of Taranto, serving as an ...

. The crisis eased before the need for British involvement occurred. ''Australia'' remained in the Mediterranean until 14 July 1936, then visited Gallipoli in company with the new light cruiser , before the two ships sailed for Australia.Frame, ''No Pleasure Cruise'', p. 145 They arrived in Sydney on 11 August. During the cruiser's time on exchange, the British cruiser operated with the RAN.

After returning, ''Australia'' spent the remainder of 1936 in the vicinity of Sydney and

After returning, ''Australia'' spent the remainder of 1936 in the vicinity of Sydney and Jervis Bay

Jervis Bay () is a oceanic bay and village on the south coast of New South Wales, Australia, said to possess the whitest sand in the world.

A area of land around the southern headland of the bay is a territory of the Commonwealth of Austral ...

, excluding a visit to Melbourne in November. The warship sailed to New Zealand in April 1937, then in July departed on a three-month northern cruise, with visits to ports in Queensland, New Guinea, and New Britain. ''Australia'' repeated her November visit to Melbourne, and cruised to Hobart in February 1938, before being placed in reserve on 24 April 1938. She underwent a modernisation refit at Cockatoo Island Dockyard

The Cockatoo Island Dockyard was a major dockyard in Sydney, Australia, based on Cockatoo Island. The dockyard was established in 1857 to maintain Royal Navy warships. It later built and repaired military and battle ships, and played a key role ...

, during which her single 4-inch guns were replaced with twin mountings, belt armour

Belt armor is a layer of heavy metal armor plated onto or within the outer hulls of warships, typically on battleships, battlecruisers and cruisers, and aircraft carriers.

The belt armor is designed to prevent projectiles from penetrating to ...

measuring up to thick was fitted over the machinery spaces, and handling arrangements for the ship's aircraft and boats were improved. Although the modernisation was scheduled for completion in March 1939, inconsistencies between ''Australia''s construction and the supplied drawings

Drawing is a visual art that uses an instrument to mark paper or another two-dimensional surface. The instruments used to make a drawing are pencils, crayons, pens with inks, brushes with paints, or combinations of these, and in more modern times ...

caused delays.Jeremey, ''Cockatoo Island'', p. 118 The cruiser was recommissioned on 28 August, but did not leave the dockyard until 28 September.

World War II

1939–1941

Following the outbreak of World War II, ''Australia'' was initially assigned to Australian waters. From 28 November to 1 December, ''Australia'', ''Canberra'', and ''Sydney'' hunted for the German pocket battleship ''Admiral Graf Spee'' in the Indian Ocean.Frame, ''No Pleasure Cruise'', p. 153 From 10 to 20 January 1940, ''Australia'' was part of the escort forAnzac convoy US 1

The Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) was a First World War army corps of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force. It was formed in Egypt in December 1914, and operated during the Gallipoli campaign. General William Birdwood comma ...

as it proceeded from Sydney to Fremantle, then sailed with it to the edge of the Australia Station

The Australia Station was the British, and later Australian, naval command responsible for the waters around the Australian continent.Dennis et al. 2008, p.53. Australia Station was under the command of the Commander-in-Chief, Australia Station, ...

en route to Colombo, before returning to Fremantle.Gill, ''Royal Australian Navy, 1939–1942'', pp. 91–93 On arrival, ''Australia'' relieved as the cruiser assigned to the western coast until 6 February, when she was in turn relieved by and returned to the east coast. On 12 May, ''Australia'' and ''Canberra'' left Fremantle to escort Anzac convoy US 3

The Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) was a First World War army corps of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force. It was formed in Egypt in December 1914, and operated during the Gallipoli campaign. General William Birdwood comma ...

to Cape Town.Cassells, ''The Capital Ships'', p. 23 After arriving on 31 May, the two ships were offered for service under the Royal Navy; ''Australia'' was accepted for service in European waters, although she spent most of June escorting ship around southern and western Africa.Gill, ''Royal Australian Navy, 1939–1942'', p. 170

On 3 July, ''Australia'' and the carrier were ordered to sail to Dakar

Dakar ( ; ; wo, Ndakaaru) (from daqaar ''tamarind''), is the capital and largest city of Senegal. The city of Dakar proper has a population of 1,030,594, whereas the population of the Dakar metropolitan area is estimated at 3.94 million in ...

, where the cruiser was shadowing the French battleship ''Richelieu'' and preparing to deny her use to the Vichy French

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its t ...

if required. ''Australia'' and ''Hermes'' reached the rendezvous in the early morning of 5 July. Attempts to disable the battleship were made by boat and air during 7 and 8 July; on the second day, ''Australia'' fired in anger

{{Short pages monitor