Gustave Le Bon on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

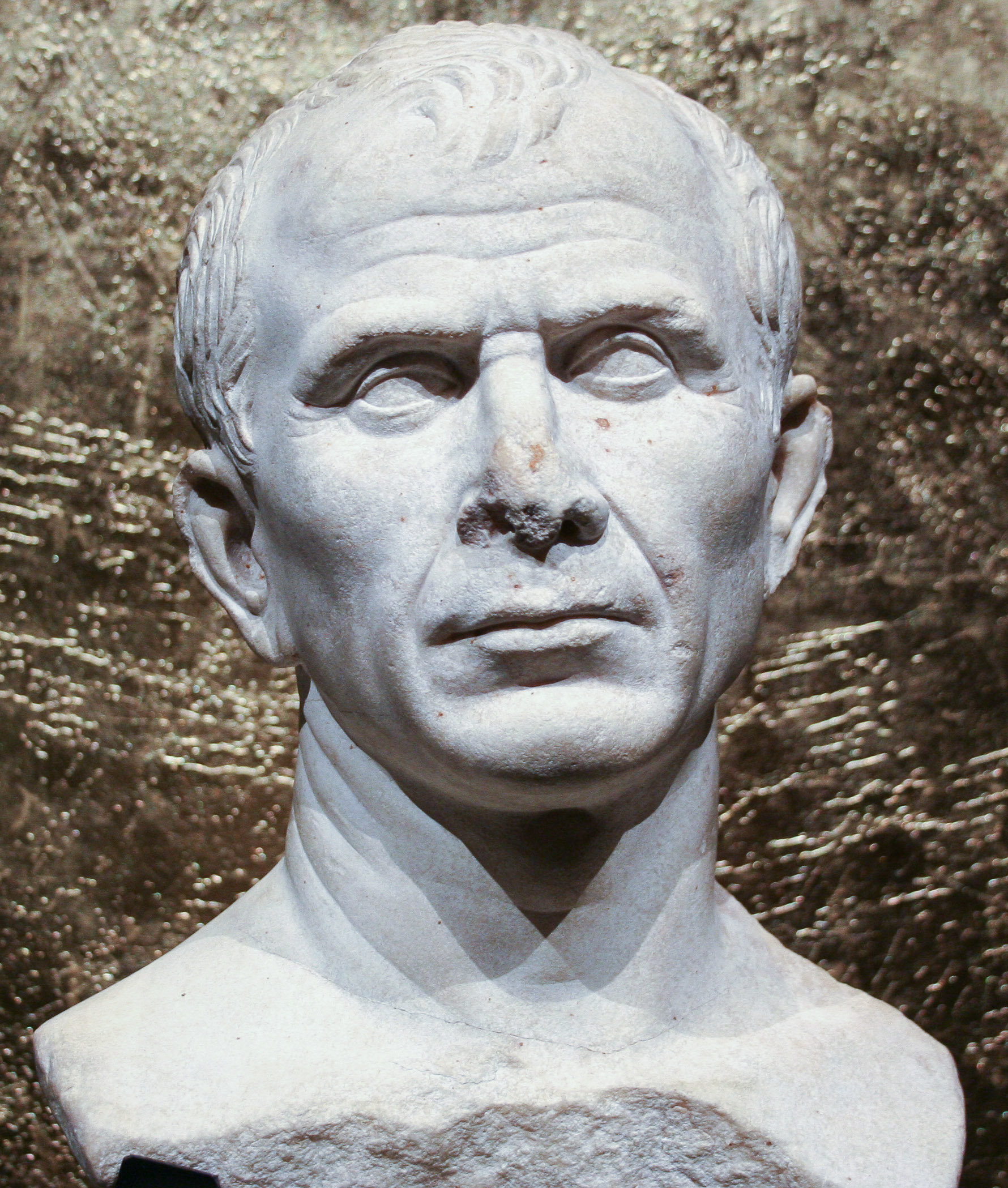

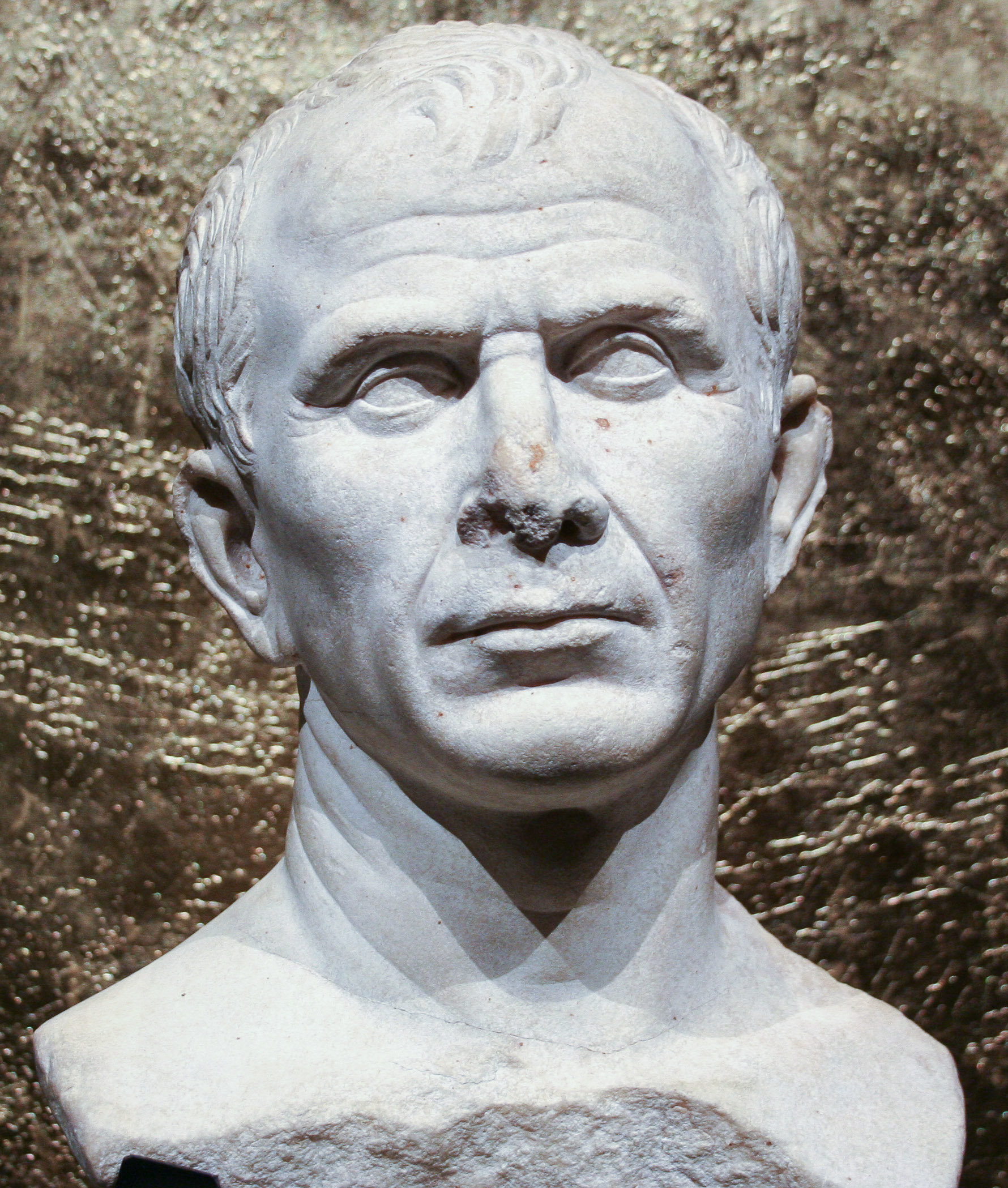

Charles-Marie Gustave Le Bon (7 May 1841 – 13 December 1931) was a leading French

After his graduation, Le Bon remained in Paris, where he taught himself English and German by reading

After his graduation, Le Bon remained in Paris, where he taught himself English and German by reading

Le Bon became interested in the emerging field of

Le Bon became interested in the emerging field of

On his travels, Le Bon travelled largely on horseback and noticed that techniques used by horse breeders and trainers varied dependent on the region. He returned to Paris and in 1892, while riding a high-spirited horse, he was bucked off and narrowly escaped death. He was unsure as to what caused him to be thrown off the horse, and decided to begin a study of what he had done wrong as a rider. The result of his study was ''L'Équitation actuelle et ses principes. Recherches expérimentales'' (1892), which consisted of numerous photographs of horses in action combined with analysis by Le Bon. This work became a respected cavalry manual, and Le Bon extrapolated his studies on the behaviour of horses to develop theories on

On his travels, Le Bon travelled largely on horseback and noticed that techniques used by horse breeders and trainers varied dependent on the region. He returned to Paris and in 1892, while riding a high-spirited horse, he was bucked off and narrowly escaped death. He was unsure as to what caused him to be thrown off the horse, and decided to begin a study of what he had done wrong as a rider. The result of his study was ''L'Équitation actuelle et ses principes. Recherches expérimentales'' (1892), which consisted of numerous photographs of horses in action combined with analysis by Le Bon. This work became a respected cavalry manual, and Le Bon extrapolated his studies on the behaviour of horses to develop theories on  Le Bon constructed a home laboratory in the early 1890s, and in 1896 reported observing "black light", a new kind of

Le Bon constructed a home laboratory in the early 1890s, and in 1896 reported observing "black light", a new kind of  Le Bon discontinued his research in physics in 1908, and turned again to psychology. He released ''La Psychologie politique et la défense sociale'', ''Les Opinions et les croyances'', ''La Révolution Française et la Psychologie des Révolutions'', ''Aphorismes du temps présent'', and ''La Vie des vérités'' in back-to-back years from 1910 to 1914, expounding in which his views on affective and rational thought, the psychology of race, and the history of civilisation.

Le Bon discontinued his research in physics in 1908, and turned again to psychology. He released ''La Psychologie politique et la défense sociale'', ''Les Opinions et les croyances'', ''La Révolution Française et la Psychologie des Révolutions'', ''Aphorismes du temps présent'', and ''La Vie des vérités'' in back-to-back years from 1910 to 1914, expounding in which his views on affective and rational thought, the psychology of race, and the history of civilisation.

Le Bon continued writing throughout

Le Bon continued writing throughout

George Lachmann Mosse claimed that fascist theories of leadership that emerged during the 1920s owed much to Le Bon's theories of crowd psychology.

George Lachmann Mosse claimed that fascist theories of leadership that emerged during the 1920s owed much to Le Bon's theories of crowd psychology.

"''The Psychology of Peoples''"

1898

Audiobook available

* '' Psychologie des Foules (1895); (" The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind''", 1986

Full text availableAudiobook available

* ''Psychologie du Socialisme'' (1896)

''The Psychology of Socialism''

(1899) * ''Psychologie de l'éducation'' (1902); ("The Psychology of Education") * ''La Psychologie Politique et la Défense Sociale'' (1910); ("The Psychology of Politics and Social Defense") * ''Les Opinions et les croyances'' (1911); ("Opinions and Beliefs") * ''La Révolution Française et la Psychologie des Révolutions'' (1912)

''The Psychology of Revolution''

(1913

Audiobook available

''The French Revolution and the Psychology of Revolution'' (1980). * ''Aphorismes du temps présent'' (1913); ("Aphorisms of Present Times") * ''La Vie des vérités'' (1914); ("Truths of Life") * ''Enseignements Psychologiques de la Guerre Européenne'' (1915)

''The Psychology of the Great War''

(1916) * ''Premières conséquences de la guerre: transformation mentale des peuples'' (1916); ("First Consequences of War: Mental Transformation of Peoples") * ''Hier et demain. Pensées brèves'' (1918); ("Yesterday and Tomorrow. Brief thoughts") * ''Psychologie des Temps Nouveaux'' (1920)

''The World in Revolt''

(1921) * ''Le Déséquilibre du Monde'' (1923)

''The World Unbalanced''

(1924) * ''Les Incertitudes de l'heure présente'' (1924); ("The Uncertainties of the Present Hour") * ''L'Évolution actuelle du monde, illusions et réalités'' (1927); ("The Current Evolution of the World, Illusions and Realities") * ''Bases scientifiques d'une philosophie de l'histoire'' (1931); ("Scientific Basis for a Philosophy of History") Natural science * ''La Méthode graphique et les appareils enregistreurs'' (1878); ("The Graphical Method and recording devices") * ''Recherches anatomiques et mathématiques sur les variations de volume du cerveau et sur leurs relations avec l'intelligence'' (1879); ("Anatomical and mathematical research on the changes in brain volume and its relationships with intelligence") * ''La Fumée du tabac'' (1880); ("Tobacco smoke") * ''Les Levers photographiques'' (1888); ("Photographic surveying") * ''L'Équitation actuelle et ses principes. Recherches expérimentales'' (1892); ("Equitation: The Psychology of the Horse") * ''L'Évolution de la Matière'' (1905)

''The Evolution of Matter''

(1907) * ''La Naissance et l'évanouissement de la matière'' (1907); ("The birth and disappearance of matter") * ''L'Évolution des Forces'' (1907)

''The Evolution of Forces''

(1908)

Gustave Le Bon's works:

Page on Gustave Le Bon with his works available in French and in English

{{DEFAULTSORT:Le Bon, Gustave 1841 births 1931 deaths People from Nogent-le-Rotrou Burials at Père Lachaise Cemetery Crowd psychologists French anthropologists French archaeologists French people of Breton descent French physicists French psychologists 19th-century French social scientists French sociologists Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour History of psychology Propaganda theorists Social psychologists University of Paris alumni

polymath

A polymath or polyhistor is an individual whose knowledge spans many different subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific problems. Polymaths often prefer a specific context in which to explain their knowledge, ...

whose areas of interest included anthropology

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, society, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including archaic humans. Social anthropology studies patterns of behav ...

, psychology

Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior. Its subject matter includes the behavior of humans and nonhumans, both consciousness, conscious and Unconscious mind, unconscious phenomena, and mental processes such as thoughts, feel ...

, sociology

Sociology is the scientific study of human society that focuses on society, human social behavior, patterns of Interpersonal ties, social relationships, social interaction, and aspects of culture associated with everyday life. The term sociol ...

, medicine

Medicine is the science and Praxis (process), practice of caring for patients, managing the Medical diagnosis, diagnosis, prognosis, Preventive medicine, prevention, therapy, treatment, Palliative care, palliation of their injury or disease, ...

, invention, and physics

Physics is the scientific study of matter, its Elementary particle, fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge whi ...

. He is best known for his 1895 work '' The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind'', which is considered one of the seminal works of crowd psychology

Crowd psychology (or mob psychology) is a subfield of social psychology which examines how the psychology of a group of people differs from the psychology of any one person within the group. The study of crowd psychology looks into the actions ...

.

A native of Nogent-le-Rotrou, Le Bon qualified as a doctor of medicine at the University of Paris

The University of Paris (), known Metonymy, metonymically as the Sorbonne (), was the leading university in Paris, France, from 1150 to 1970, except for 1793–1806 during the French Revolution. Emerging around 1150 as a corporation associated wit ...

in 1866. He opted against the formal practice of medicine as a physician, instead beginning his writing career the same year of his graduation. He published a number of medical articles and books before joining the French Army

The French Army, officially known as the Land Army (, , ), is the principal Army, land warfare force of France, and the largest component of the French Armed Forces; it is responsible to the Government of France, alongside the French Navy, Fren ...

after the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the War of 1870, was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the North German Confederation led by the Kingdom of Prussia. Lasting from 19 July 1870 to 28 Janua ...

. Defeat in the war coupled with being a first-hand witness to the Paris Commune

The Paris Commune (, ) was a French revolutionary government that seized power in Paris on 18 March 1871 and controlled parts of the city until 28 May 1871. During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, the French National Guard (France), Nation ...

of 1871 strongly shaped Le Bon's worldview. He then travelled widely, touring Europe, Asia and North Africa. He analysed the peoples and the civilisations he encountered under the umbrella of the nascent field of anthropology, developing an essentialist view of humanity, and invented a portable cephalometer during his travels.

In the 1890s, he turned to psychology and sociology, in which fields he released his most successful works. Le Bon developed the view that crowds are not the sum of their individual parts, proposing that within crowds there forms a new psychological entity, the characteristics of which are determined by the " racial unconscious" of the crowd. At the same time he created his psychological and sociological theories, he performed experiments in physics and published popular books on the subject, anticipating the mass–energy equivalence

In physics, mass–energy equivalence is the relationship between mass and energy in a system's rest frame. The two differ only by a multiplicative constant and the units of measurement. The principle is described by the physicist Albert Einstei ...

and prophesising the Atomic Age. Le Bon maintained his eclectic interests up until his death in 1931.

Ignored or maligned by sections of the French academic and scientific establishment during his life due to his politically conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

and reactionary

In politics, a reactionary is a person who favors a return to a previous state of society which they believe possessed positive characteristics absent from contemporary.''The New Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought'' Third Edition, (1999) p. 729. ...

views, Le Bon was critical of majoritarianism

Majoritarianism is a political philosophy or ideology with an agenda asserting that a majority, whether based on a religion, language, social class, or other category of the population, is entitled to a certain degree of primacy in society, ...

and socialism

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

.

Biography

Youth

Charles-Marie Gustave Le Bon was born in Nogent-le-Rotrou,Centre-Val de Loire

Centre-Val de Loire (; ,In isolation, ''Centre'' is pronounced . ) or Centre Region (, ), as it was known until 2015, is one of the eighteen Regions of France, administrative regions of France. It straddles the middle Loire Valley in the interior ...

on 7 May 1841 to a family of Breton ancestry. At the time of Le Bon's birth, his mother, Annette Josephine Eugénic Tétiot Desmarlinais, was twenty-six and his father, Jean-Marie Charles Le Bon, was forty-one and a provincial functionary of the French government. Le Bon was a direct descendant of Jean-Odet Carnot, whose grandfather, Jean Carnot, had a brother, Denys, from whom the fifth president of the French Third Republic

The French Third Republic (, sometimes written as ) was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 1940, after the Fall of France durin ...

, Marie François Sadi Carnot, was directly descended.

When Le Bon was eight years old, his father obtained a new post in French government and the family, including Gustave's younger brother Georges, left Nogent-le-Rotrou never to return. Nonetheless, the town was proud that Gustave Le Bon was born there and later named a street after him. Little else is known of Le Bon's childhood, except for his attendance at a lycée in Tours

Tours ( ; ) is the largest city in the region of Centre-Val de Loire, France. It is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Indre-et-Loire. The Communes of France, commune of Tours had 136,463 inhabita ...

, where he was an unexceptional student.

In 1860, he began medicinal studies at the University of Paris

The University of Paris (), known Metonymy, metonymically as the Sorbonne (), was the leading university in Paris, France, from 1150 to 1970, except for 1793–1806 during the French Revolution. Emerging around 1150 as a corporation associated wit ...

. He completed his internship at Hôtel-Dieu de Paris In French-speaking countries, a hôtel-Dieu () was originally a hospital for the poor and needy, run by the Catholic Church. Nowadays these buildings or institutions have either kept their function as a hospital, the one in Paris being the oldest an ...

, and received his doctorate

A doctorate (from Latin ''doctor'', meaning "teacher") or doctoral degree is a postgraduate academic degree awarded by universities and some other educational institutions, derived from the ancient formalism '' licentia docendi'' ("licence to teach ...

in 1866. From that time on, he referred to himself as "Doctor" though he never formally worked as a physician. During his university years, Le Bon wrote articles on a range of medical topics, the first of which related to the maladies that plagued those who lived in swamp

A swamp is a forested wetland.Keddy, P.A. 2010. Wetland Ecology: Principles and Conservation (2nd edition). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 497 p. Swamps are considered to be transition zones because both land and water play a role in ...

-like conditions. He published several other about loa loa filariasis and asphyxia

Asphyxia or asphyxiation is a condition of deficient supply of oxygen to the body which arises from abnormal breathing. Asphyxia causes generalized hypoxia, which affects all the tissues and organs, some more rapidly than others. There are m ...

before releasing his first full-length book in 1866, ''De la mort apparente et des inhumations prématurées''. This work dealt with the definition of death

Death is the end of life; the irreversible cessation of all biological functions that sustain a living organism. Death eventually and inevitably occurs in all organisms. The remains of a former organism normally begin to decompose sh ...

, preceding 20th-century legal debates on the issue.

Life in Paris

After his graduation, Le Bon remained in Paris, where he taught himself English and German by reading

After his graduation, Le Bon remained in Paris, where he taught himself English and German by reading William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

's works in each language. He maintained his passion for writing and authored several papers on physiological

Physiology (; ) is the science, scientific study of function (biology), functions and mechanism (biology), mechanisms in a life, living system. As a branches of science, subdiscipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ syst ...

studies, as well as an 1868 textbook about sexual reproduction

Sexual reproduction is a type of reproduction that involves a complex life cycle in which a gamete ( haploid reproductive cells, such as a sperm or egg cell) with a single set of chromosomes combines with another gamete to produce a zygote tha ...

, before joining the French Army

The French Army, officially known as the Land Army (, , ), is the principal Army, land warfare force of France, and the largest component of the French Armed Forces; it is responsible to the Government of France, alongside the French Navy, Fren ...

as a medical officer after the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the War of 1870, was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the North German Confederation led by the Kingdom of Prussia. Lasting from 19 July 1870 to 28 Janua ...

in July 1870. During the war, Le Bon organised a division of military ambulance

An ambulance is a Medical device, medically-equipped vehicle used to transport patients to Health facility, treatment facilities, such as hospitals. Typically, out-of-hospital medical care is provided to the patient during the transport. Ambu ...

s. In that capacity, he observed the behaviour of the military under the worst possible condition—total defeat, and wrote about his reflections on military discipline, leadership and the behaviour of man in a state of stress and suffering. These reflections garnered praise from generals, and were later studied at Saint-Cyr and other military academies in France. At the end of the war, Le Bon was named a ''Chevalier'' of the Legion of Honour

The National Order of the Legion of Honour ( ), formerly the Imperial Order of the Legion of Honour (), is the highest and most prestigious French national order of merit, both military and Civil society, civil. Currently consisting of five cl ...

.

Le Bon also witnessed the Paris Commune

The Paris Commune (, ) was a French revolutionary government that seized power in Paris on 18 March 1871 and controlled parts of the city until 28 May 1871. During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, the French National Guard (France), Nation ...

of 1871, which deeply affected his worldview. The then thirty-year-old Le Bon looked on as Parisian revolutionary crowds burned down the Tuileries Palace

The Tuileries Palace (, ) was a palace in Paris which stood on the right bank of the Seine, directly in the west-front of the Louvre Palace. It was the Parisian residence of most French monarchs, from Henri IV to Napoleon III, until it was b ...

, the library of the Louvre

The Louvre ( ), or the Louvre Museum ( ), is a national art museum in Paris, France, and one of the most famous museums in the world. It is located on the Rive Droite, Right Bank of the Seine in the city's 1st arrondissement of Paris, 1st arron ...

, the Hôtel de Ville, the Gobelins Manufactory, the Palais de Justice, and other irreplaceable works of architectural art.

From 1871 on, Le Bon was an avowed opponent of socialist

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

pacifists

Pacifism is the opposition to war or violence. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaigner Émile Arnaud and adopted by other peace activists at the tenth Universal Peace Congress in Glasgow in 1901. A related term is ''a ...

and protectionists, who he believed were halting France's martial development and stifling her industrial growth; stating in 1913: "Only people with lots of cannons have the right to be pacifists." He also warned his countrymen of the deleterious effects of political rivalries in the face of German military might and rapid industrialisation, and therefore was uninvolved in the Dreyfus Affair which dichotomised France.

Widespread travels

Le Bon became interested in the emerging field of

Le Bon became interested in the emerging field of anthropology

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, society, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including archaic humans. Social anthropology studies patterns of behav ...

in the 1870s and travelled throughout Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

, Asia

Asia ( , ) is the largest continent in the world by both land area and population. It covers an area of more than 44 million square kilometres, about 30% of Earth's total land area and 8% of Earth's total surface area. The continent, which ...

and North Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

. Influenced by Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

, Herbert Spencer

Herbert Spencer (27 April 1820 – 8 December 1903) was an English polymath active as a philosopher, psychologist, biologist, sociologist, and anthropologist. Spencer originated the expression "survival of the fittest", which he coined in '' ...

and Ernst Haeckel

Ernst Heinrich Philipp August Haeckel (; ; 16 February 1834 – 9 August 1919) was a German zoologist, natural history, naturalist, eugenics, eugenicist, Philosophy, philosopher, physician, professor, marine biology, marine biologist and artist ...

, Le Bon supported biological determinism

Biological determinism, also known as genetic determinism, is the belief that human behaviour is directly controlled by an individual's genes or some component of their physiology, generally at the expense of the role of the environment, wheth ...

and a hierarchical view of the races and sexes; after extensive field research, he posited a correlation between cranial capacity and intelligence in ''Recherches anatomiques et mathématiques sur les variations de volume du cerveau et sur leurs relations avec l'intelligence'' (1879), which earned him the Godard Prize from the French Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (, ) is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French Scientific method, scientific research. It was at the forefron ...

. During his research, he invented a portable cephalometer to aid with measuring the physical characteristics of remote peoples, and in 1881 published a paper, "''The Pocket Cephalometer, or Compass of Coordinates''", detailing his invention and its application.

In 1884, he was commissioned by the French government to travel around Asia

Asia ( , ) is the largest continent in the world by both land area and population. It covers an area of more than 44 million square kilometres, about 30% of Earth's total land area and 8% of Earth's total surface area. The continent, which ...

and report on the civilisations there. The results of his journeys were a number of books, and a development in Le Bon's thinking to also view culture to be influenced chiefly by hereditary factors such as the unique racial features of the people. The first book, entitled ''La Civilisation des Arabes'', was released in 1884. In this, Le Bon praised Arabs

Arabs (, , ; , , ) are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in West Asia and North Africa. A significant Arab diaspora is present in various parts of the world.

Arabs have been in the Fertile Crescent for thousands of yea ...

highly for their contributions to civilisation, but criticised Islamism

Islamism is a range of religious and political ideological movements that believe that Islam should influence political systems. Its proponents believe Islam is innately political, and that Islam as a political system is superior to communism ...

as an agent of stagnation. He also described their culture as superior to that of the Turks who governed them, and translations of this work were inspirational to early Arab nationalists

Arab nationalism () is a political ideology asserting that Arabs constitute a single nation. As a traditional nationalist ideology, it promotes Arab culture and civilization, celebrates Arab history, the Arabic language and Arabic literatur ...

. He followed this with a trip to Nepal

Nepal, officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal, is a landlocked country in South Asia. It is mainly situated in the Himalayas, but also includes parts of the Indo-Gangetic Plain. It borders the Tibet Autonomous Region of China Ch ...

, becoming the first Frenchman to visit the country, and released ''Voyage au Népal'' in 1886.

He next published ''Les Civilisations de l'Inde'' (1887), in which he applauded Indian architecture, art and religion but argued that Indians were comparatively inferior to Europeans in regard to scientific advancements, and that this had facilitated British domination. In 1889, he released ''Les Premières Civilisations de l'Orient'', giving in it an overview of the Mesopotamian, Indian, Chinese and Egyptian civilisations. The same year, he delivered a speech to the International Colonial Congress criticising colonial policies which included attempts of cultural assimilation

Cultural assimilation is the process in which a minority group or culture comes to resemble a society's Dominant culture, majority group or fully adopts the values, behaviors, and beliefs of another group. The melting pot model is based on this ...

, stating: "Leave to the natives their customs, their institutions and their laws." Le Bon released the last book on the topic of his travels, entitled ''Les monuments de l'Inde'', in 1893, again praising the architectural achievements of the Indian people.

Development of theories

On his travels, Le Bon travelled largely on horseback and noticed that techniques used by horse breeders and trainers varied dependent on the region. He returned to Paris and in 1892, while riding a high-spirited horse, he was bucked off and narrowly escaped death. He was unsure as to what caused him to be thrown off the horse, and decided to begin a study of what he had done wrong as a rider. The result of his study was ''L'Équitation actuelle et ses principes. Recherches expérimentales'' (1892), which consisted of numerous photographs of horses in action combined with analysis by Le Bon. This work became a respected cavalry manual, and Le Bon extrapolated his studies on the behaviour of horses to develop theories on

On his travels, Le Bon travelled largely on horseback and noticed that techniques used by horse breeders and trainers varied dependent on the region. He returned to Paris and in 1892, while riding a high-spirited horse, he was bucked off and narrowly escaped death. He was unsure as to what caused him to be thrown off the horse, and decided to begin a study of what he had done wrong as a rider. The result of his study was ''L'Équitation actuelle et ses principes. Recherches expérimentales'' (1892), which consisted of numerous photographs of horses in action combined with analysis by Le Bon. This work became a respected cavalry manual, and Le Bon extrapolated his studies on the behaviour of horses to develop theories on early childhood education

Early childhood education (ECE), also known as nursery education, is a branch of Education sciences, education theory that relates to the teaching of children (formally and informally) from birth up to the age of eight. Traditionally, this is ...

.

Le Bon's behavioural study of horses also sparked a long-standing interest in psychology

Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior. Its subject matter includes the behavior of humans and nonhumans, both consciousness, conscious and Unconscious mind, unconscious phenomena, and mental processes such as thoughts, feel ...

, and in 1894 he released ''Lois psychologiques de l'évolution des peuples''. This work was dedicated to his friend Charles Richet though it drew much from the theories of Théodule-Armand Ribot

Théodule-Armand Ribot (18 December 18399 December 1916) was a French psychologist. He was born at Guingamp, and was educated at the Lycée de St Brieuc. He is known as the founder of scientific psychology in France, and gave his name to Ribot's ...

, to whom Le Bon dedicated '' Psychologie des Foules'' (1895). ''Psychologie des Foules'' was in part a summation of Le Bon's 1881 work, ''L'Homme et les sociétés,'' to which Émile Durkheim

David Émile Durkheim (; or ; 15 April 1858 – 15 November 1917) was a French Sociology, sociologist. Durkheim formally established the academic discipline of sociology and is commonly cited as one of the principal architects of modern soci ...

referred in his doctoral dissertation, '' De la division du travail social''.

Both were best-sellers, with ''Psychologie des Foules'' being translated into nineteen languages within one year of its appearance. Le Bon followed these with two more books on psychology, ''Psychologie du Socialisme'' and ''Psychologie de l'Éducation'', in 1896 and 1902 respectively. These works rankled the largely socialist academic establishment of France.

Le Bon constructed a home laboratory in the early 1890s, and in 1896 reported observing "black light", a new kind of

Le Bon constructed a home laboratory in the early 1890s, and in 1896 reported observing "black light", a new kind of radiation

In physics, radiation is the emission or transmission of energy in the form of waves or particles through space or a material medium. This includes:

* ''electromagnetic radiation'' consisting of photons, such as radio waves, microwaves, infr ...

that he believed was distinct from, but possibly related to, X-ray

An X-ray (also known in many languages as Röntgen radiation) is a form of high-energy electromagnetic radiation with a wavelength shorter than those of ultraviolet rays and longer than those of gamma rays. Roughly, X-rays have a wavelength ran ...

s and cathode ray

Cathode rays are streams of electrons observed in discharge tubes. If an evacuated glass tube is equipped with two electrodes and a voltage is applied, glass behind the positive electrode is observed to glow, due to electrons emitted from the c ...

s. Not the same type of radiation as what is now known as black light

A blacklight, also called a UV-A light, Wood's lamp, or ultraviolet light, is a lamp (fixture), lamp that emits long-wave (UV-A) ultraviolet light and very little visible light. One type of lamp has a violet light filter, filter material, eith ...

, its existence was never confirmed and, similar to N ray

N-rays (or N rays) were a hypothesized form of radiation described by :French physicists, French physicist Prosper-René Blondlot in 1903. They were initially confirmed by others, but subsequently found to be illusory.

Background

The N-ray a ...

s, it is now generally understood to be non-existent, but the discovery claim attracted much attention among French scientists at the time, many of whom supported it and Le Bon's general ideas on matter and radiation, and he was even nominated for the Nobel Prize in Physics

The Nobel Prize in Physics () is an annual award given by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences for those who have made the most outstanding contributions to mankind in the field of physics. It is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the ...

in 1903.

In 1902, Le Bon began a series of weekly luncheons to which he invited prominent intellectuals, nobles and ladies of fashion. The strength of his personal networks is apparent from the guest list: participants included cousins Henri and Raymond Poincaré

Raymond Nicolas Landry Poincaré (; 20 August 1860 – 15 October 1934) was a French statesman who served as President of France from 1913 to 1920, and three times as Prime Minister of France. He was a conservative leader, primarily committed to ...

, Paul Valéry

Ambroise Paul Toussaint Jules Valéry (; 30 October 1871 – 20 July 1945) was a French poet, essayist, and philosopher.

In addition to his poetry and fiction (drama and dialogues), his interests included aphorisms on art, history, letters, m ...

, Alexander Izvolsky, Henri Bergson

Henri-Louis Bergson (; ; 18 October 1859 – 4 January 1941) was a French philosopher who was influential in the traditions of analytic philosophy and continental philosophy, especially during the first half of the 20th century until the S ...

, Marcellin Berthelot and Aristide Briand

Aristide Pierre Henri Briand (; 28 March 18627 March 1932) was a French statesman who served eleven terms as Prime Minister of France during the French Third Republic. He is mainly remembered for his focus on international issues and reconciliat ...

.

In ''L'Évolution de la Matière'' (1905), Le Bon anticipated the mass–energy equivalence

In physics, mass–energy equivalence is the relationship between mass and energy in a system's rest frame. The two differ only by a multiplicative constant and the units of measurement. The principle is described by the physicist Albert Einstei ...

, and in a 1922 letter to Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein (14 March 187918 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist who is best known for developing the theory of relativity. Einstein also made important contributions to quantum mechanics. His mass–energy equivalence f ...

complained about his lack of recognition. Einstein responded and conceded that a mass–energy equivalence had been proposed before him, but only the theory of relativity

The theory of relativity usually encompasses two interrelated physics theories by Albert Einstein: special relativity and general relativity, proposed and published in 1905 and 1915, respectively. Special relativity applies to all physical ph ...

had cogently proved it. Gaston Moch gave Le Bon credit for anticipating Einstein's theory of relativity. In ''L'Évolution des Forces'' (1907), Le Bon prophesied the Atomic Age. He wrote about "the manifestation of a new force—namely intra-atomic energy—which surpasses all others by its colossal magnitude," and stated that a scientist who discovered a way to dissociate

Dissociation in chemistry is a general process in which molecules (or ionic compounds such as salts, or complexes) separate or split into other things such as atoms, ions, or radicals, usually in a reversible manner. For instance, when an aci ...

rapidly one gram of any metal would "not witness the results of his experiments ... the explosion produced would be so formidable that his laboratory and all neighbouring houses, with their inhabitants, would be instantaneously pulverised."

Le Bon discontinued his research in physics in 1908, and turned again to psychology. He released ''La Psychologie politique et la défense sociale'', ''Les Opinions et les croyances'', ''La Révolution Française et la Psychologie des Révolutions'', ''Aphorismes du temps présent'', and ''La Vie des vérités'' in back-to-back years from 1910 to 1914, expounding in which his views on affective and rational thought, the psychology of race, and the history of civilisation.

Le Bon discontinued his research in physics in 1908, and turned again to psychology. He released ''La Psychologie politique et la défense sociale'', ''Les Opinions et les croyances'', ''La Révolution Française et la Psychologie des Révolutions'', ''Aphorismes du temps présent'', and ''La Vie des vérités'' in back-to-back years from 1910 to 1914, expounding in which his views on affective and rational thought, the psychology of race, and the history of civilisation.

Later life and death

Le Bon continued writing throughout

Le Bon continued writing throughout World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, publishing ''Enseignements Psychologiques de la Guerre Européenne'' (1915), ''Premières conséquences de la guerre: transformation mentale des peuples'' (1916) and ''Hier et demain. Pensées brèves'' (1918) during the war.

He then released ''Psychologie des Temps Nouveaux'' (1920) before resigning from his position as Professor of Psychology and Allied Sciences at the University of Paris and retiring to his home.

He released ''Le Déséquilibre du Monde'', ''Les Incertitudes de l'heure présente'' and ''L'évolution actuelle du monde, illusions et réalités'' in 1923, 1924 and 1927 respectively, giving in them his views of the world during the volatile interwar period

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period, also known as the interbellum (), lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days) – from the end of World War I (WWI) to the beginning of World War II ( ...

.

He became a ''Grand-Croix'' of the Legion of Honour in 1929. He published his last work, entitled ''Bases scientifiques d'une philosophie de l'histoire'', in 1931 and on 13 December, died in Marnes-la-Coquette

Marnes-la-Coquette () is a commune in the western suburbs of Paris, France. Located from the centre of Paris, the town is situated in the Hauts-de-Seine department on the departmental border with Yvelines

Yvelines () is a department in th ...

, Île-de-France

The Île-de-France (; ; ) is the most populous of the eighteen regions of France, with an official estimated population of 12,271,794 residents on 1 January 2023. Centered on the capital Paris, it is located in the north-central part of the cou ...

at the age of ninety.

Le Bonian thought

Convinced that human actions are guided by eternal laws, Le Bon attempted to synthesiseAuguste Comte

Isidore Auguste Marie François Xavier Comte (; ; 19 January 1798 – 5 September 1857) was a French philosopher, mathematician and writer who formulated the doctrine of positivism. He is often regarded as the first philosopher of science in the ...

and Herbert Spencer

Herbert Spencer (27 April 1820 – 8 December 1903) was an English polymath active as a philosopher, psychologist, biologist, sociologist, and anthropologist. Spencer originated the expression "survival of the fittest", which he coined in '' ...

with Jules Michelet

Jules Michelet (; 21 August 1798 – 9 February 1874) was a French historian and writer. He is best known for his multivolume work ''Histoire de France'' (History of France). Michelet was influenced by Giambattista Vico; he admired Vico's emphas ...

and Alexis de Tocqueville

Alexis Charles Henri Clérel, comte de Tocqueville (29 July 180516 April 1859), was a French Aristocracy (class), aristocrat, diplomat, political philosopher, and historian. He is best known for his works ''Democracy in America'' (appearing in t ...

.

Inspirations

According to Steve Reicher, Le Bon was not the first crowd psychologist: "The first debate in crowd psychology was actually between twocriminologists

Criminology (from Latin , 'accusation', and Ancient Greek , ''-logia'', from λόγος ''logos'', 'word, reason') is the interdisciplinarity, interdisciplinary study of crime and Deviance (sociology), deviant behaviour. Criminology is a mul ...

, Scipio Sighele and Gabriel Tarde, concerning how to determine and assign criminal responsibility within a crowd and hence who to arrest." Le Bon, who also explicitly recognised the positive potential of crowds, viewed the criminological focus of the earlier authors as an unnecessary restriction for the study of crowd psychology.

Crowds

Le Bon theorised that the new entity, the "psychological crowd", which emerges from incorporating the assembled population not only forms a new body but also creates a collective "unconsciousness". As a group of people gather together and coalesces to form a crowd, there is a "magnetic influence given out by the crowd" that transmutes every individual's behaviour until it becomes governed by the " group mind". This model treats the crowd as a unit in its composition which robs every individual member of their opinions, values and beliefs; as Le Bon states: "An individual in a crowd is a grain of sand amid other grains of sand, which the wind stirs up at will". Le Bon detailed three key processes that create the psychological crowd: i) Anonymity, ii) Contagion and iii) Suggestibility. Anonymity provides to rational individuals a feeling of invincibility and the loss of personal responsibility. An individual becomes primitive, unreasoning, and emotional. This lack of self-restraint allows individuals to "yield to instincts" and to accept the instinctual drives of their " unconscious". For Le Bon, the crowd inverts Darwin's law of evolution and becomes atavistic, provingErnst Haeckel

Ernst Heinrich Philipp August Haeckel (; ; 16 February 1834 – 9 August 1919) was a German zoologist, natural history, naturalist, eugenics, eugenicist, Philosophy, philosopher, physician, professor, marine biology, marine biologist and artist ...

's embryological theory: "ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny

Ontogeny (also ontogenesis) is the origination and development of an organism (both physical and psychological, e.g., moral development), usually from the time of fertilization of the ovum, egg to adult. The term can also be used to refer to t ...

". Contagion refers to the spread in the crowd of particular behaviours and individuals sacrifice their personal interest for the collective interest. Suggestibility is the mechanism through which the contagion is achieved; as the crowd coalesces into a singular mind, suggestions made by strong voices in the crowd create a space for the unconscious to come to the forefront and guide its behaviour. At this stage, the psychological crowd becomes homogeneous and malleable to suggestions from its strongest members. "The leaders we speak of," says Le Bon, "are usually men of action rather than of words. They are not gifted with keen foresight... They are especially recruited from the ranks of those morbidly nervous excitable half-deranged persons who are bordering on madness."

Influence

George Lachmann Mosse claimed that fascist theories of leadership that emerged during the 1920s owed much to Le Bon's theories of crowd psychology.

George Lachmann Mosse claimed that fascist theories of leadership that emerged during the 1920s owed much to Le Bon's theories of crowd psychology. Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

is known to have read ''The Crowd'' and in ''Mein Kampf

(; ) is a 1925 Autobiography, autobiographical manifesto by Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler. The book outlines many of Political views of Adolf Hitler, Hitler's political beliefs, his political ideology and future plans for Nazi Germany, Ge ...

'' drew on the propaganda techniques

Propaganda techniques are methods used in propaganda to convince an audience to believe what the propagandist wants them to believe. Many propaganda techniques are based on social psychology, socio-psychological research. Many of these same tech ...

proposed by Le Bon. Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

also made a careful study of Le Bon.

Le Bon was widely read within the Committee of Union and Progress

The Ottoman Committee of Union and Progress (CUP, also translated as the Society of Union and Progress; , French language, French: ''Union et Progrès'') was a revolutionary group, secret society, and political party, active between 1889 and 1926 ...

in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Philosophical and military leaders who would later lead the Young Turk Revolution

The Young Turk Revolution (July 1908; ) was a constitutionalist revolution in the Ottoman Empire. Revolutionaries belonging to the Internal Committee of Union and Progress, an organization of the Young Turks movement, forced Sultan Abdul Hamid II ...

, such as Ahmet Rıza and Enver Bey, took inspiration from Le Bon and movements such as Social Darwinism

Charles Darwin, after whom social Darwinism is named

Social Darwinism is a body of pseudoscientific theories and societal practices that purport to apply biological concepts of natural selection and survival of the fittest to sociology, economi ...

to define their elitist and authoritarian approach to politics, as well as their advocacy of revolution from above.

Some commentators have drawn a link between Le Bon and Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

/ the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

.

Just prior to World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, Wilfred Trotter

Wilfred Batten Lewis Trotter, FRS (3 November 1872 – 25 November 1939) was an English surgeon, a pioneer in neurosurgery. He was also known for his studies on social psychology, most notably for his concept of the herd instinct, which he f ...

introduced Wilfred Bion

Wilfred Ruprecht Bion (; 8 September 1897 – 8 November 1979) was an influential English psychoanalyst, who became president of the British Psychoanalytical Society from 1962 to 1965.

Early life and military service

Bion was born in Mathu ...

to Le Bon's writings and Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud ( ; ; born Sigismund Schlomo Freud; 6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating psychopathology, pathologies seen as originating fro ...

's work ''Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego

''Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego'' () is a 1921 book by Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis.

In this monograph, Freud describes psychological mechanisms at work within mass movements. A ''mass'', according to Freud, is ...

''. Trotter's book ''Instincts of the Herd in Peace and War'' (1919) forms the basis for the research of both Wilfred Bion and Ernest Jones who established what would be called group dynamics

Group dynamics is a system of behaviors and psychological processes occurring within a social group (''intra''group dynamics), or between social groups ( ''inter''group dynamics). The study of group dynamics can be useful in understanding decision ...

. During the first half of the twentieth century, Le Bon's writings were used by media researchers such as Hadley Cantril

Albert Hadley Cantril, Jr. (16 June 1906 – 28 May 1969) was an American psychologist from Princeton University, who expanded the scope of the field.

Cantril made "major contributions in psychology of propaganda; public opinion research; applica ...

and Herbert Blumer

Herbert George Blumer (March 7, 1900 – April 13, 1987) was an American sociologist whose main scholarly interests were symbolic interactionism and methods of social research. Believing that individuals create social reality through collective ...

to describe the reactions of subordinate groups to media.

Edward Bernays

Edward Louis Bernays ( ; ; November 22, 1891 − March 9, 1995) was an American pioneer in the field of public relations and propaganda, referred to in his obituary as "the father of public relations". While credited with advancing the profession ...

, a nephew of Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud ( ; ; born Sigismund Schlomo Freud; 6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating psychopathology, pathologies seen as originating fro ...

, was influenced by Le Bon and Trotter. In his influential book ''Propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded l ...

'', he declared that a major feature of democracy

Democracy (from , ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which political power is vested in the people or the population of a state. Under a minimalist definition of democracy, rulers are elected through competitiv ...

was the manipulation of the electorate by the mass media

Mass media include the diverse arrays of media that reach a large audience via mass communication.

Broadcast media transmit information electronically via media such as films, radio, recorded music, or television. Digital media comprises b ...

and advertising

Advertising is the practice and techniques employed to bring attention to a Product (business), product or Service (economics), service. Advertising aims to present a product or service in terms of utility, advantages, and qualities of int ...

. Some have claimed that, Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

and Charles G. Dawes and many other American progressives in the early 20th century were also deeply affected by Le Bon's writings.

See also

* Philosophical anthropology * ''Völkerpsychologie Völkerpsychologie is a method of psychology that was founded in the nineteenth century by the famous psychologist, Wilhelm Wundt. However, the term was first coined by post-Hegelian social philosophers Heymann Steinthal and Moritz Lazarus.

Wund ...

''

Works

:''Bibliography compiled from the 1984 reissue of Psychologie du Socialisme.'' Medical * ''De la mort apparente et des inhumations prématurées'' (1866); ("Apparent Death and Premature Burials") * ''Traité pratique des maladies des organes génitaux-urinaires'' (1869); ("Practical Treatise of Diseases of the Genitourinary System") * ''La Vie physiologique humaine appliquée à l'hygiène et à la médecine'' (1874); ("Life (Treatise of Human Physiology)") Anthropology, psychology and sociology * ''Histoire des origines et du développement de l'homme et des sociétés'' (1877); ("History of the Origins and Development of Man and Society") * ''Voyage aux Monts-Tatras'' (1881); ("Travel to Tatra Mountains") * ''L'Homme et les sociétés'' (1881); ("Man and Society") * ''La Civilisation des Arabes'' (1884); ''The World of Islamic Civilization'' (1884) * ''Voyage au Népal'' (1886); ("Travel to Nepal") * ''Les Civilisations de l'Inde'' (1887); ("The Civilisations of India") * ''Les Premières Civilisations de l'Orient'' (1889); ("The First Civilisations of the Orient") * ''Les Monuments de l'Inde'' (1893); ("The Monuments of India") * ''Les Lois Psychologiques de l'Évolution des Peuples'' (1894);"''The Psychology of Peoples''"

1898

Audiobook available

* '' Psychologie des Foules (1895); (" The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind''", 1986

Full text available

* ''Psychologie du Socialisme'' (1896)

''The Psychology of Socialism''

(1899) * ''Psychologie de l'éducation'' (1902); ("The Psychology of Education") * ''La Psychologie Politique et la Défense Sociale'' (1910); ("The Psychology of Politics and Social Defense") * ''Les Opinions et les croyances'' (1911); ("Opinions and Beliefs") * ''La Révolution Française et la Psychologie des Révolutions'' (1912)

''The Psychology of Revolution''

(1913

Audiobook available

''The French Revolution and the Psychology of Revolution'' (1980). * ''Aphorismes du temps présent'' (1913); ("Aphorisms of Present Times") * ''La Vie des vérités'' (1914); ("Truths of Life") * ''Enseignements Psychologiques de la Guerre Européenne'' (1915)

''The Psychology of the Great War''

(1916) * ''Premières conséquences de la guerre: transformation mentale des peuples'' (1916); ("First Consequences of War: Mental Transformation of Peoples") * ''Hier et demain. Pensées brèves'' (1918); ("Yesterday and Tomorrow. Brief thoughts") * ''Psychologie des Temps Nouveaux'' (1920)

''The World in Revolt''

(1921) * ''Le Déséquilibre du Monde'' (1923)

''The World Unbalanced''

(1924) * ''Les Incertitudes de l'heure présente'' (1924); ("The Uncertainties of the Present Hour") * ''L'Évolution actuelle du monde, illusions et réalités'' (1927); ("The Current Evolution of the World, Illusions and Realities") * ''Bases scientifiques d'une philosophie de l'histoire'' (1931); ("Scientific Basis for a Philosophy of History") Natural science * ''La Méthode graphique et les appareils enregistreurs'' (1878); ("The Graphical Method and recording devices") * ''Recherches anatomiques et mathématiques sur les variations de volume du cerveau et sur leurs relations avec l'intelligence'' (1879); ("Anatomical and mathematical research on the changes in brain volume and its relationships with intelligence") * ''La Fumée du tabac'' (1880); ("Tobacco smoke") * ''Les Levers photographiques'' (1888); ("Photographic surveying") * ''L'Équitation actuelle et ses principes. Recherches expérimentales'' (1892); ("Equitation: The Psychology of the Horse") * ''L'Évolution de la Matière'' (1905)

''The Evolution of Matter''

(1907) * ''La Naissance et l'évanouissement de la matière'' (1907); ("The birth and disappearance of matter") * ''L'Évolution des Forces'' (1907)

''The Evolution of Forces''

(1908)

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * *External links

* * * *Gustave Le Bon's works:

Page on Gustave Le Bon with his works available in French and in English

{{DEFAULTSORT:Le Bon, Gustave 1841 births 1931 deaths People from Nogent-le-Rotrou Burials at Père Lachaise Cemetery Crowd psychologists French anthropologists French archaeologists French people of Breton descent French physicists French psychologists 19th-century French social scientists French sociologists Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour History of psychology Propaganda theorists Social psychologists University of Paris alumni