German Revolutions Of 1848–1849 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The German revolutions of 1848–1849 (), the opening phase of which was also called the March Revolution (), were initially part of the

The provisional government first appointed Joseph Martin Reichard, a lawyer, democrat and deputy in the Frankfurt Assembly, as the head of the military department in the Palatinate. The first Commander in Chief of the military forces of the Palatinate was Daniel Fenner von Fenneberg, a former Austrian officer who commanded the national guard in Vienna during the 1848 uprising. He was soon replaced by Felix Raquilliet, a former Polish staff general in the Polish insurgent army of 1830–1831. Finally Ludwik Mieroslawski was given supreme command of the armed forces in the Palatinate, and Franz Sznayde was given field command of the troops.

Other noteworthy military officers serving the provisional government in the city of

The provisional government first appointed Joseph Martin Reichard, a lawyer, democrat and deputy in the Frankfurt Assembly, as the head of the military department in the Palatinate. The first Commander in Chief of the military forces of the Palatinate was Daniel Fenner von Fenneberg, a former Austrian officer who commanded the national guard in Vienna during the 1848 uprising. He was soon replaced by Felix Raquilliet, a former Polish staff general in the Polish insurgent army of 1830–1831. Finally Ludwik Mieroslawski was given supreme command of the armed forces in the Palatinate, and Franz Sznayde was given field command of the troops.

Other noteworthy military officers serving the provisional government in the city of  Despite Sigel's plan, the new insurgent government did not go on the offensive. The uprising in Karlsruhe and the Grand Duchy of Baden was eventually suppressed by the

Despite Sigel's plan, the new insurgent government did not go on the offensive. The uprising in Karlsruhe and the Grand Duchy of Baden was eventually suppressed by the

On 13 March, after warnings by the police against public demonstrations went unheeded, the army charged a group of people returning from a meeting in the Tiergarten, leaving one person dead and many injured. On 18 March, a large demonstration occurred. After two shots were fired, fearing that some of the 20,000 soldiers would be used against them, demonstrators erected barricades, and a battle ensued until troops were ordered 13 hours later to retreat, leaving hundreds dead. Afterwards, Frederick William attempted to reassure the public that he would proceed with reorganizing his government. The King also approved arming the citizens.

On 13 March, after warnings by the police against public demonstrations went unheeded, the army charged a group of people returning from a meeting in the Tiergarten, leaving one person dead and many injured. On 18 March, a large demonstration occurred. After two shots were fired, fearing that some of the 20,000 soldiers would be used against them, demonstrators erected barricades, and a battle ensued until troops were ordered 13 hours later to retreat, leaving hundreds dead. Afterwards, Frederick William attempted to reassure the public that he would proceed with reorganizing his government. The King also approved arming the citizens.

In his memoirs, Field Marshal Alfred von Waldersee, who in March 1848 was a sixteen-year-old student at the Royal Prussian Cadet Corps, gave a vivid description of the revolutionary events in Berlin:

In his memoirs, Field Marshal Alfred von Waldersee, who in March 1848 was a sixteen-year-old student at the Royal Prussian Cadet Corps, gave a vivid description of the revolutionary events in Berlin:

A Constituent National Assembly was elected from various German states in late April and early May 1848 and gathered in St. Paul's Church in Frankfurt am Main on 18 May 1848. The deputies consisted of 122 government officials, 95 judges, 81 lawyers, 103 teachers, 17 manufacturers and wholesale dealers, 15 physicians, and 40 landowners. A majority of the Assembly were liberals. It became known as the "professors' parliament", as many of its members were academics in addition to their other responsibilities. The one working-class member was Polish and, like colleagues from the

A Constituent National Assembly was elected from various German states in late April and early May 1848 and gathered in St. Paul's Church in Frankfurt am Main on 18 May 1848. The deputies consisted of 122 government officials, 95 judges, 81 lawyers, 103 teachers, 17 manufacturers and wholesale dealers, 15 physicians, and 40 landowners. A majority of the Assembly were liberals. It became known as the "professors' parliament", as many of its members were academics in addition to their other responsibilities. The one working-class member was Polish and, like colleagues from the

The Prussian government mistook this quietude in the Rhineland for loyalty to the autocratic Prussian government. The Prussian government began offering military assistance to other states in suppressing the revolts in their territories and cities, ''i.e''. Dresden, the Palatinate, Baden, Wűrttemberg, Franconia, ''etc''. Soon the Prussians discovered that they needed additional troops in this effort. Taking the loyalty of the Rhineland for granted, in the spring of 1849 the Prussian government called up a large portion of the army reserve—the ''

The Prussian government mistook this quietude in the Rhineland for loyalty to the autocratic Prussian government. The Prussian government began offering military assistance to other states in suppressing the revolts in their territories and cities, ''i.e''. Dresden, the Palatinate, Baden, Wűrttemberg, Franconia, ''etc''. Soon the Prussians discovered that they needed additional troops in this effort. Taking the loyalty of the Rhineland for granted, in the spring of 1849 the Prussian government called up a large portion of the army reserve—the ''

Revolutions of 1848

The revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the springtime of the peoples or the springtime of nations, were a series of revolutions throughout Europe over the course of more than one year, from 1848 to 1849. It remains the most widespre ...

that broke out in many European countries. They were a series of loosely coordinated protests and rebellions in the states of the German Confederation

The German Confederation ( ) was an association of 39 predominantly German-speaking sovereign states in Central Europe. It was created by the Congress of Vienna in 1815 as a replacement of the former Holy Roman Empire, which had been dissolved ...

, including the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire, officially known as the Empire of Austria, was a Multinational state, multinational European Great Powers, great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the Habsburg monarchy, realms of the Habsburgs. Duri ...

. The revolutions, which stressed pan-Germanism

Pan-Germanism ( or '), also occasionally known as Pan-Germanicism, is a pan-nationalist political idea. Pan-Germanism seeks to unify all ethnic Germans, German-speaking people, and possibly also non-German Germanic peoples – into a sin ...

, liberalism and parliamentarianism, demonstrated popular discontent with the traditional, largely autocratic political structure of the thirty-nine independent states of the Confederation that inherited the German territory of the former Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

after its dismantlement as a result of the Napoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

. This process began in the mid-1840s.

The middle-class elements were committed to liberal principles, while the working class sought radical improvements to their working and living conditions. As the middle class and working class components of the Revolution split, the conservative aristocracy defeated it. Liberals were forced into exile to escape political persecution, where they became known as Forty-Eighters. Many emigrated to the United States, settling from Wisconsin

Wisconsin ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Great Lakes region, Great Lakes region of the Upper Midwest of the United States. It borders Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake Michigan to the east, Michig ...

to Texas

Texas ( , ; or ) is the most populous U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, New Mexico to the we ...

.

Events leading up to the revolutions

The groundwork of the 1848 uprising was laid as early as the Hambacher Fest of 1832, when public unrest began to grow in the face of heavy taxation and political censorship. The Hambacher Fest is also noteworthy for the Republicans adopting the black-red-gold colours used on today's nationalflag of Germany

The national flag of Germany () is a tricolour (flag), tricolour consisting of three equal horizontal bands displaying the national colours of Germany: Sable (heraldry), black, Gules, red, and Or (heraldry), gold (). The flag was first sight ...

as a symbol of the Republican movement and of the unity among the German-speaking people. The song " Fürsten zum Land Hinaus!" originated from the festival, and quickly garnered popular support for the abolition of monarchy and establishment of a Republic.

Activism for liberal reforms spread through many of the German states, each of which had distinct revolutions. They were also inspired by the street demonstrations in Paris, France, led by workers and artisans which took place through 22 to 24 February 1848, and resulted in the abdication of King Louis-Philippe of France

Louis Philippe I (6 October 1773 – 26 August 1850), nicknamed the Citizen King, was King of the French from 1830 to 1848, the penultimate monarch of France, and the last French monarch to bear the title "King". He abdicated from his thron ...

and his exile to Britain. In France the revolution of 1848 became known as the February Revolution

The February Revolution (), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and sometimes as the March Revolution or February Coup was the first of Russian Revolution, two revolutions which took place in Russia ...

.

The revolutions spread from France across Europe; demonstrations against the government erupted soon thereafter in both Austria and Germany, beginning with large protests on 13 March 1848, in Vienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

. This resulted in the resignation of Prince von Metternich as chief minister to Emperor Ferdinand I of Austria

Ferdinand I ( 19 April 1793 – 29 June 1875) was Emperor of Austria from March 1835 until his abdication in December 1848. He was also King of Hungary, King of Croatia, Croatia and King of Bohemia, Bohemia (as Ferdinand V), King of Lombardy– ...

, and his going into exile in Britain. Because of the date of the Vienna demonstrations, the protests throughout Germany are usually called the March Revolution ().

Afraid of suffering the same fate as Louis-Philippe of France, some of the German monarchs acquiesced to the demands of the revolutionaries, at least temporarily. In the south and west, large popular assemblies and mass demonstrations took place. They demanded freedom of the press

Freedom of the press or freedom of the media is the fundamental principle that communication and expression through various media, including printed and electronic Media (communication), media, especially publication, published materials, shoul ...

, freedom of assembly

Freedom of assembly, sometimes used interchangeably with the freedom of association, is the individual right or ability of individuals to peaceably assemble and collectively express, promote, pursue, and defend their ideas. The right to free ...

, written constitutions, arming of the people and a Parliament.

Austria

In 1848, Austria was the predominant German state. After the collapse of theHoly Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

, which had been dissolved by Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

in 1806, it was succeeded by a similarly loose coalition of states known as the German Confederation at the Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon, Napol ...

in 1815. Austria served as President ''ex officio'' of this confederation. The (German) Austrian chancellor Klemens von Metternich had dominated Austrian politics from 1815 until 1848.

On 13 March 1848, university students mounted a large street demonstration in Vienna, and it was covered by the press across the German-speaking states. Following the important, but relatively minor, demonstrations against Lola Montez in Bavaria on 9 February 1848 (see below), the first major revolt of 1848 in German lands occurred in Vienna on 13 March 1848. The demonstrating students in Vienna had been restive and were encouraged by a sermon of Anton Füster, a liberal priest, on Sunday, 12 March 1848, in their university chapel. The student demonstrators demanded a constitution and a constituent assembly elected by universal male suffrage.

Emperor Ferdinand and his chief advisor Metternich directed troops to crush the demonstration. When demonstrators moved to the streets near the Hofburg

The Hofburg () is the former principal imperial palace of the Habsburg dynasty in Austria. Located in the Innere Stadt, center of Vienna, it was built in the 13th century by Ottokar II of Bohemia and expanded several times afterwards. It also ser ...

, the troops fired on the demonstrating students, killing several of them. The new working class of Vienna joined the student demonstrations, developing an armed insurrection. The Diet of Lower Austria

Lower Austria ( , , abbreviated LA or NÖ) is one of the nine states of Austria, located in the northeastern corner of the country. Major cities are Amstetten, Lower Austria, Amstetten, Krems an der Donau, Wiener Neustadt and Sankt Pölten, which ...

demanded Metternich's resignation. With no forces rallying to Metternich's defense, Ferdinand reluctantly complied and dismissed him. The former chancellor went into exile in London.

Ferdinand appointed new, nominally liberal, ministers. The Austrian government drafted a constitution in late April 1848. The people rejected this, as the majority was denied the right to vote. The citizens of Vienna returned to the streets from 26 May through 27, 1848, erecting barricades to prepare for an army attack. Ferdinand and his family fled to Innsbruck

Innsbruck (; ) is the capital of Tyrol (federal state), Tyrol and the List of cities and towns in Austria, fifth-largest city in Austria. On the Inn (river), River Inn, at its junction with the Wipptal, Wipp Valley, which provides access to the ...

, where they spent the next few months surrounded by the loyal peasantry of the Tyrol

Tyrol ( ; historically the Tyrole; ; ) is a historical region in the Alps of Northern Italy and western Austria. The area was historically the core of the County of Tyrol, part of the Holy Roman Empire, Austrian Empire and Austria-Hungary, f ...

. Ferdinand issued two manifestos on 16 May 1848, and 3 June 1848, which gave concessions to the people. He converted the Imperial Diet into a Constituent Assembly to be elected by the people. Other concessions were less substantial, and generally addressed the reorganizing and unification of Germany.

Ferdinand returned to Vienna from Innsbruck on 12 August 1848. Soon after his return, the working-class populace hit the streets again on 21 August to protest high unemployment and the government's decree to reduce wages. On 23 August 1848, Austrian troops opened fire on unarmed demonstrators and shot several of them.

In late September 1848, Emperor Ferdinand, who was also King Ferdinand V of Hungary, decided to send Austrian and Croatian troops to Hungary to crush a democratic rebellion there. On 29 September 1848, the Austrian troops were defeated by the Hungarian revolutionary forces. On 6 October through 7, 1848, the citizens of Vienna had demonstrated against the emperor's actions against forces in Hungary, resulting in the Vienna Uprising

The Vienna Uprising or October Revolution (, or ) of October 1848 was the last uprising in the Austrian Revolution of 1848.

On 6 October 1848, as the troops of the Austrian Empire were preparing to leave Vienna to suppress the Hungarian Revolu ...

. As a result, Emperor Ferdinand I fled Vienna on 7 October 1848, taking up residence in the fortress town of Olomouc

Olomouc (; ) is a city in the Czech Republic. It has about 103,000 inhabitants, making it the Statutory city (Czech Republic), sixth largest city in the country. It is the administrative centre of the Olomouc Region.

Located on the Morava (rive ...

in Moravia

Moravia ( ; ) is a historical region in the eastern Czech Republic, roughly encompassing its territory within the Danube River's drainage basin. It is one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The medieval and early ...

. On 2 December 1848, Ferdinand abdicated in favour of his nephew Franz Joseph

Franz Joseph I or Francis Joseph I ( ; ; 18 August 1830 – 21 November 1916) was Emperor of Austria, King of Hungary, and the ruler of the Grand title of the emperor of Austria, other states of the Habsburg monarchy from 1848 until his death ...

.

Baden

Baden

Baden (; ) is a historical territory in southern Germany. In earlier times it was considered to be on both sides of the Upper Rhine, but since the Napoleonic Wars, it has been considered only East of the Rhine.

History

The margraves of Ba ...

had a liberal constitution from 1811 until reaction resulted in Grand Duke Louis I Louis I may refer to:

Cardinals

* Louis I, Cardinal of Guise (1527–1578)

Counts

* Ludwig I, Count of Württemberg (c. 1098–1158)

* Louis I of Blois (1172–1205)

* Louis I of Flanders (1304–1346)

* Louis I of Châtillon (died 13 ...

revoking the constitution in 1825. In 1830, Leopold became Grand Duke. His reign brought liberal reforms in constitutional, civil and criminal law, and in education. In 1832 Baden joined the (Prussian) Customs Union. After news broke of revolutionary victories in February 1848 in Paris, uprisings occurred throughout Europe, including Austria and the German states.

Baden was the first state in Germany to have popular unrest, despite Baden being one of the most liberal states in Germany. After the news of the February Days in Paris reached Baden, there were several unorganized instances of peasants burning the mansions of local aristocrats and threatening them.

On 27 February 1848, in Mannheim

Mannheim (; Palatine German language, Palatine German: or ), officially the University City of Mannheim (), is the List of cities in Baden-Württemberg by population, second-largest city in Baden-Württemberg after Stuttgart, the States of Ger ...

, an assembly of people from Baden adopted a resolution demanding a bill of rights. Similar resolutions were adopted in Württemberg

Württemberg ( ; ) is a historical German territory roughly corresponding to the cultural and linguistic region of Swabia. The main town of the region is Stuttgart.

Together with Baden and Province of Hohenzollern, Hohenzollern, two other histo ...

, Hesse-Darmstadt, Nassau, and other German states. The surprisingly strong popular support for these movements forced rulers to give in to many of the (demands of March) almost without resistance.

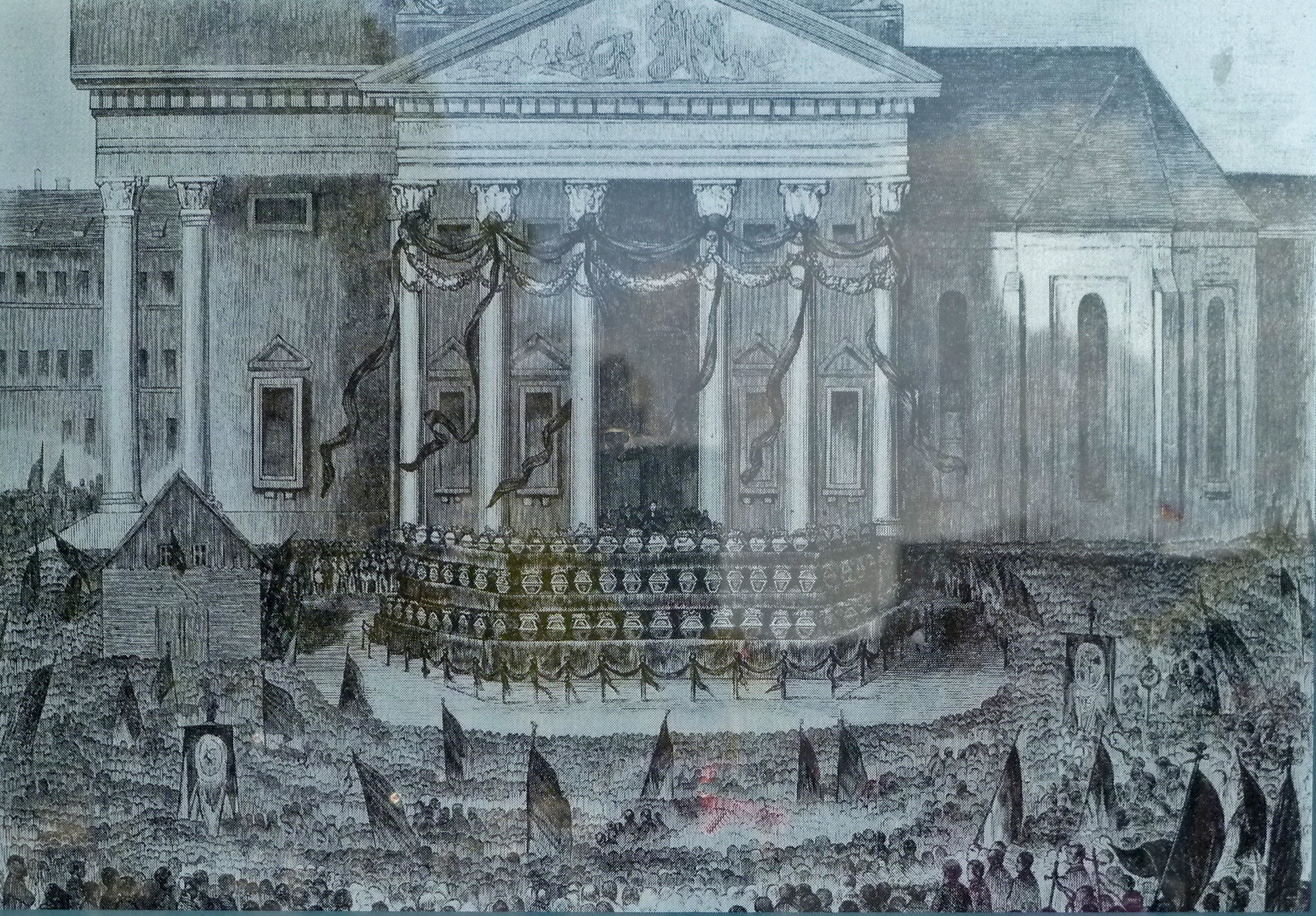

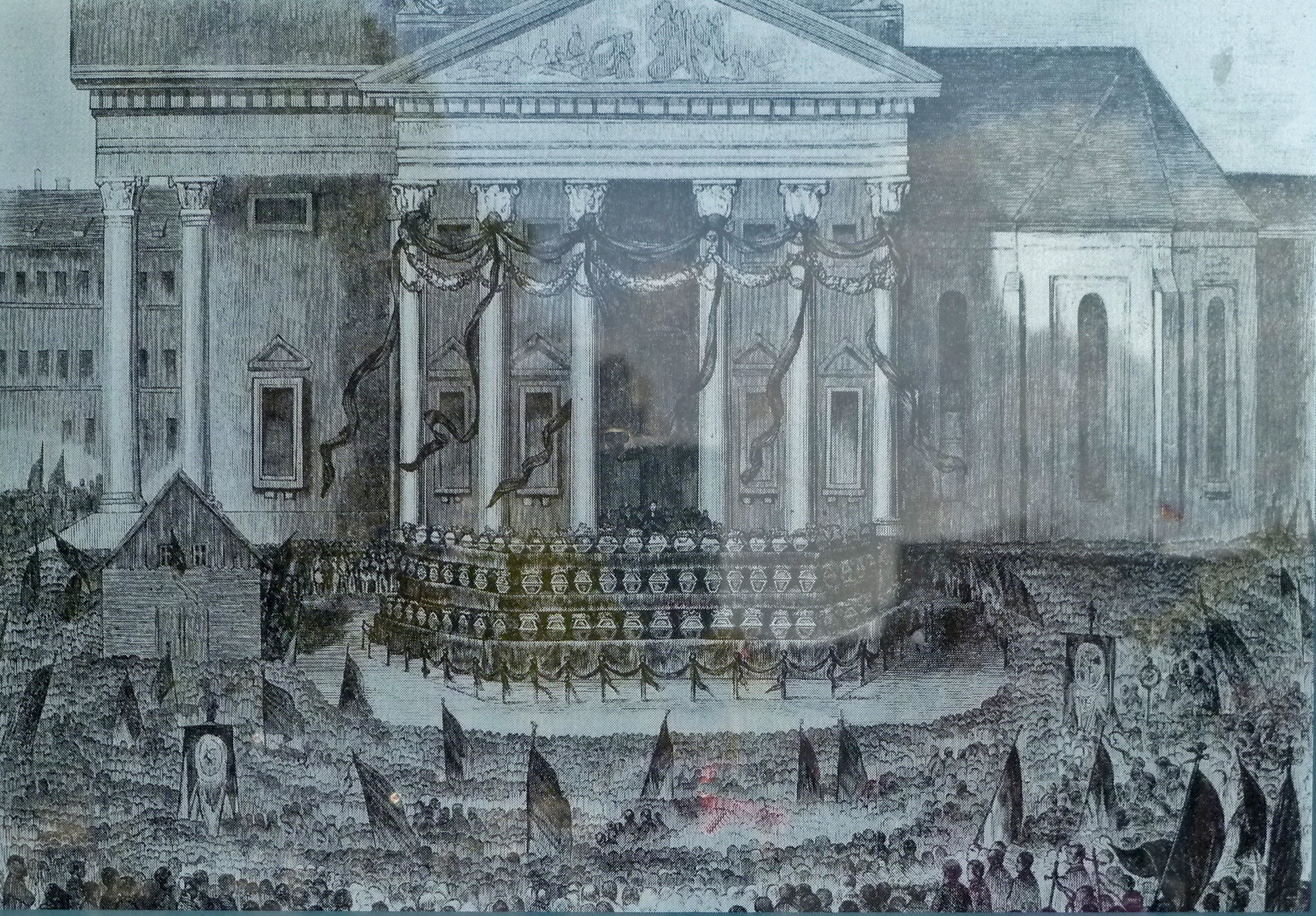

The March Revolution in Vienna was a catalyst to revolution throughout the German states. Popular demands were made for an elected representative government and for the unification of Germany. Fear on the part of the princes and rulers of the various German states caused them to concede in the demand for reform. They approved a provisional parliament, which was convened from 31 March 1848, until 4 April 1848, in St. Paul's Church in Frankfurt am Main, charged with the task of drafting a new constitution, to be called the "Fundamental Rights and Demands of the German People." The majority of the delegates to the provisional parliament were constitutional monarchists.

Baden sent two democrats, Friedrich Karl Franz Hecker and Gustav von Struve, to the provisional parliament. In the minority and frustrated with the lack of progress, Hecker and Struve walked out in protest on 2 April 1848. The walkout and the continuing revolutionary upsurge in Germany spurred the provisional parliament to action; they passed a resolution calling for an All-German National Assembly to be formed.

On 8 April 1848, a law allowing universal suffrage and an indirect (two-stage) voting system was agreed to by the assembly. A new National Assembly was selected, and on 18 May 1848, 809 delegates (585 of whom were elected) were seated at St. Paul's Church in Frankfurt to convene the Frankfurt Parliament

The Frankfurt National Assembly () was the first freely elected parliament for all German Confederation, German states, including the German-populated areas of the Austrian Empire, elected on 1 May 1848 (see German federal election, 1848).

The ...

. Karl Mathy, a right-center journalist, was among those elected as deputy to the Frankfurt National Assembly.

Disorder fomented by republican agitators continued in Baden. Fearing greater riots, the Baden government began to increase the size of its army

An army, ground force or land force is an armed force that fights primarily on land. In the broadest sense, it is the land-based military branch, service branch or armed service of a nation or country. It may also include aviation assets by ...

and to seek assistance from neighboring states. The Baden government sought to suppress the revolts by arresting Joseph Fickler, a journalist who was the leader of the Baden democrats. The arrests caused outrage and a rise in protests. A full-scale uprising broke out on 12 April 1848. The Bavarian government suppressed the revolutionary forces led by Friedrich Hecker

Friedrich Karl Franz Hecker (September 28, 1811 – March 24, 1881) was a German lawyer, politician and revolutionary. He was one of the most popular speakers and agitators of the 1848 Revolution. After moving to the United States, he served a ...

with the aid of Prussian troops at the Battle on the Scheideck on 20 April 1848, ending what became known as the Hecker Uprising.

In May 1849, a resurgence of revolutionary activity occurred in Baden. As this was closely connected to the uprising in the Palatinate, it is described below, in the section titled, "The Palatinate".

The Palatinate

When the revolutionary upsurge revived in the spring of 1849, the uprisings started inElberfeld

Elberfeld is a municipal subdivision of the Germany, German city of Wuppertal; it was an independent town until 1929.

History

The first official mentioning of the geographic area on the banks of today's Wupper River as "''elverfelde''" was ...

in the Rhineland on 6 May 1849. However, the uprisings soon spread to the Grand Duchy of Baden

Baden (; ) is a historical territory in southern Germany. In earlier times it was considered to be on both sides of the Upper Rhine, but since the Napoleonic Wars, it has been considered only East of the Rhine.

History

The margraves of Ba ...

, when a riot broke out in Karlsruhe

Karlsruhe ( ; ; ; South Franconian German, South Franconian: ''Kallsruh'') is the List of cities in Baden-Württemberg by population, third-largest city of the States of Germany, German state of Baden-Württemberg, after its capital Stuttgart a ...

. The state of Baden and the Palatinate (then part of the Kingdom of Bavaria

The Kingdom of Bavaria ( ; ; spelled ''Baiern'' until 1825) was a German state that succeeded the former Electorate of Bavaria in 1806 and continued to exist until 1918. With the unification of Germany into the German Empire in 1871, the kingd ...

) were separated only by the Rhine. The uprising in Baden and the Palatinate took place largely in the Rhine Valley along their mutual border, and are considered aspects of the same movement. In May 1849, the Grand Duke was forced to leave Karlsruhe, Baden and seek help from Prussia. Provisional governments were declared in both the Palatinate and Baden. In Baden conditions for the provisional government were ideal: the public and army were both strongly in support of constitutional change and democratic reform in the government. The army strongly supported the demands for a constitution; the state had amply supplied arsenals, and a full exchequer. The Palatinate did not have the same conditions.

The Palatinate traditionally contained more upper-class citizens than other areas of Germany, and they resisted the revolutionary changes. In the Palatinate, the army did not support the revolution, and it was not well supplied. When the insurrectionary government took over in the Palatinate, they did not find a fully organized state or a full exchequer. Arms in the Palatinate were limited to privately held muskets, rifles and sporting guns. The provisional government of the Palatinate sent agents to France and Belgium to purchase arms but they were unsuccessful. France banned sales and export of arms to either Baden or the Palatinate.

The provisional government first appointed Joseph Martin Reichard, a lawyer, democrat and deputy in the Frankfurt Assembly, as the head of the military department in the Palatinate. The first Commander in Chief of the military forces of the Palatinate was Daniel Fenner von Fenneberg, a former Austrian officer who commanded the national guard in Vienna during the 1848 uprising. He was soon replaced by Felix Raquilliet, a former Polish staff general in the Polish insurgent army of 1830–1831. Finally Ludwik Mieroslawski was given supreme command of the armed forces in the Palatinate, and Franz Sznayde was given field command of the troops.

Other noteworthy military officers serving the provisional government in the city of

The provisional government first appointed Joseph Martin Reichard, a lawyer, democrat and deputy in the Frankfurt Assembly, as the head of the military department in the Palatinate. The first Commander in Chief of the military forces of the Palatinate was Daniel Fenner von Fenneberg, a former Austrian officer who commanded the national guard in Vienna during the 1848 uprising. He was soon replaced by Felix Raquilliet, a former Polish staff general in the Polish insurgent army of 1830–1831. Finally Ludwik Mieroslawski was given supreme command of the armed forces in the Palatinate, and Franz Sznayde was given field command of the troops.

Other noteworthy military officers serving the provisional government in the city of Kaiserslautern

Kaiserslautern (; ) is a town in southwest Germany, located in the state of Rhineland-Palatinate at the edge of the Palatinate Forest. The historic centre dates to the 9th century. It is from Paris, from Frankfurt am Main, 666 kilometers (414 m ...

, were Friedrich Strasser, Alexander Schimmelpfennig, Captain Rudolph von Manteuffel, Albert Clement, Herr Zychlinski, Friedrich von Beust, Eugen Oswald, Amand Goegg, Gustav Struve, Otto Julius Bernhard von Corvin-Wiersbitzki, Joseph Moll, Johann Gottfried Kinkel, Herr Mersy, Karl Emmermann, Franz Sigel, Major Nerlinger, Colonel Kurz, Friedrich Karl, Franz Hecker and Herman von Natzmer. Hermann von Natzmer was the former Prussian officer who had been in charge of the arsenal of Berlin

Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List of cities in Germany by population, population. With 3.7 million inhabitants, it has the List of cities in the European Union by population withi ...

. Refusing to shoot insurgent forces who stormed the arsenal on 14 June 1848, Natzmer became a hero to insurgents across Germany. He was sentenced to 15 years in prison for refusing orders to shoot, but in 1849, he escaped prison and fled to the Palatinate to join its insurgent forces. Gustav Adolph Techow, a former Prussian officer, also joined Palatinate forces. Organizing the artillery and providing services in the ordnance shops was Lieutenant Colonel Freidrich Anneke. He was a member of the Communist League and one of the founders of the Cologne Workers Association in 1848, editor of the and a member of the Rhenish District Committee of Democrats.

Democrats of the Palatinate and across Germany considered the Baden-Palatinate insurrection to be part of the wider all-German struggle for constitutional rights. Franz Sigel, a second lieutenant in the Baden army, a democrat and a supporter of the provisional government, developed a plan to protect the reform movement in Karlsruhe and the Palatinate. He recommended using a corps of the Baden army to advance on the town of Hechingen

Hechingen (; Swabian: ''Hächenga'') is a town in central Baden-Württemberg, Germany. It is situated about south of the state capital of Stuttgart and north of Lake Constance and the Swiss border.

Geography

The town lies at the foot of th ...

and declare the Hohenzollern Republic, then to march on Stuttgart

Stuttgart (; ; Swabian German, Swabian: ; Alemannic German, Alemannic: ; Italian language, Italian: ; ) is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Baden-Württemberg by population, largest city of the States of Germany, German state of ...

. After inciting Stuttgart and the surrounding Kingdom of Württemberg

The Kingdom of Württemberg ( ) was a German state that existed from 1806 to 1918, located within the area that is now Baden-Württemberg. The kingdom was a continuation of the Electorate of Württemberg, which existed from 1803 to 1806.

Geogr ...

, the military corps would march to Nuremberg

Nuremberg (, ; ; in the local East Franconian dialect: ''Nämberch'' ) is the Franconia#Towns and cities, largest city in Franconia, the List of cities in Bavaria by population, second-largest city in the States of Germany, German state of Bav ...

and set up camp in the state of Franconia

Franconia ( ; ; ) is a geographical region of Germany, characterised by its culture and East Franconian dialect (). Franconia is made up of the three (governmental districts) of Lower Franconia, Lower, Middle Franconia, Middle and Upper Franco ...

. Sigel failed to account for dealing with the separate Free City of Frankfurt

Frankfurt was a major city of the Holy Roman Empire, being the seat of imperial elections since 885 and the city for Coronation of the Holy Roman emperor, imperial coronations from 1562 (previously in Free Imperial City of Aachen) until 1792. F ...

, the home of the Frankfurt Assembly, in order to establish an All-German character to the military campaign for the German constitution.

Despite Sigel's plan, the new insurgent government did not go on the offensive. The uprising in Karlsruhe and the Grand Duchy of Baden was eventually suppressed by the

Despite Sigel's plan, the new insurgent government did not go on the offensive. The uprising in Karlsruhe and the Grand Duchy of Baden was eventually suppressed by the Bavarian Army

The Bavarian Army () was the army of the Electorate of Bavaria, Electorate (1682–1806) and then Kingdom of Bavaria, Kingdom (1806–1918) of Bavaria. It existed from 1682 as the standing army of Bavaria until the merger of the military sovereig ...

. Lorenz Peter Brentano, a lawyer and democrat from Baden, headed its government, wielding absolute power. He appointed Karl Eichfeld as War Minister. Later, Eichfeld was replaced as War Minister by Rudolph Mayerhofer. Florian Mördes was appointed as Minister of the Interior. Other members of the provisional government included Joseph Fickler, a journalist and a democrat from Baden. Leaders of the constitutional forces in Baden included Karl Blind, a journalist and a democrat in Baden; and Gustav Struve, another journalist and democrat from Baden. John Phillip Becker was placed in charge of the peoples' militia. Ludwik Mieroslawski, a Polish-born national who had taken part in the military operations during the Polish uprising of 1830–1831, was placed in charge of the military operation on the Palatinate side of the Rhine River.

Brentano ordered the day-to-day affairs of the uprising in Baden, and Mieroslawski directed a military command on the Palatinate side. They did not coordinate well. For example, Mieroslawski decided to abolish the long-standing toll on the Mannheim-Ludwigshaven bridge over the Rhine River. It was not collected on the Palatinate side, but Brentano's government collected it on the Baden side. Due to the continued lack of coordination, Mieroslawski lost battles in Waghausle and Ubstadt in Baden. He and his troops were forced to retreat across the mountains of southern Baden, where they fought a last battle against the Prussians in the town of Murg, on the frontier between Baden and Switzerland

Switzerland, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a landlocked country located in west-central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the south, France to the west, Germany to the north, and Austria and Liechtenstein to the east. Switzerland ...

. Mieroslawski and the other survivors of the battle escaped across the frontier to Switzerland, and the commander went into exile in Paris.

Frederick Engels took part in the uprising in Baden and the Palatinate. On 10 May 1848, he and Karl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

traveled from Cologne

Cologne ( ; ; ) is the largest city of the States of Germany, German state of North Rhine-Westphalia and the List of cities in Germany by population, fourth-most populous city of Germany with nearly 1.1 million inhabitants in the city pr ...

, Germany, to observe the events of the region. From 1 June 1848, Engels and Marx became editors of the . Less than a year later, on 19 May 1849, the Prussian authorities closed down the newspaper because of its support for constitutional reforms.

In late 1848, Marx and Engels intended to meet with Karl Ludwig Johann D'Ester, then serving as a member of the provisional government in Baden and the Palatinate. He was a physician, democrat and socialist who had been a member of the Cologne community chapter of the Communist League. D'Ester had been elected as a deputy to the Prussian National Assembly in 1848. D'Ester had been elected to the Central committee of the German Democrats, together with Reichenbach and Hexamer

In chemistry and biochemistry, an oligomer () is a molecule that consists of a few repeating units which could be derived, actually or conceptually, from smaller molecules, monomer, monomers.Quote: ''Oligomer molecule: A molecule of intermediate ...

, at the Second Democratic Congress held in Berlin from 26 October through 30 October 1848. Because of his commitments to the provisional government, D'Ester was unable to attend an important meeting in Paris on behalf of the German Central Committee. He wanted to provide Marx with the mandate to attend the meeting in his place. Marx and Engels met with D'Ester in the town of Kaiserslautern

Kaiserslautern (; ) is a town in southwest Germany, located in the state of Rhineland-Palatinate at the edge of the Palatinate Forest. The historic centre dates to the 9th century. It is from Paris, from Frankfurt am Main, 666 kilometers (414 m ...

. Marx obtained the mandate and headed off to Paris.

Engels remained in the Palatinate, where in 1849 he joined citizens at the barricades of Elberfeld in the Rhineland, preparing to fight the Prussian troops expected to attack the uprising. On his way to Elberfeld, Engels took two cases of rifle cartridges which had been gathered by the workers of Solingen

Solingen (; ) is a city in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, 25 km east of Düsseldorf along the northern edge of the Bergisches Land, south of the Ruhr. After Wuppertal, it is the second-largest city in the Bergisches Land, and a member of ...

, when those workers had stormed the arsenal at Gräfrath. The Prussian troops arrived and crushed the uprising in August 1849. Engels and some others escaped to Kaiserslautern. While in Kaiserslautern on 13 June 1849, Engels joined an 800-member group of workers being formed as a military corps by August Willich, a former Prussian military officer. He was also a member of the Communist League and supported revolutionary change in Germany. The newly formed Willich Corps combined with other revolutionary groups to form an army of about 30,000 strong; it fought to resist the highly trained Prussian troops. Engels fought with the Willich Corps for their entire campaign in the Palatinate.

The Prussians defeated this revolutionary army at the Battle of Rinnthal, and the survivors of Willich's Corps crossed over the frontier into the safety of Switzerland. Engels did not reach Switzerland until 25 July 1849. He sent word of his survival to Marx and friends and comrades in London, England. A refugee in Switzerland, Engels began to write about his experiences during the revolution. He published the article, "The Campaign for the German Imperial Constitution." Due to the Prussian Army's ease in crushing the uprising, many South German states came to believe that Prussia, not Austria, was going to be the new power in the region. The suppression of the uprising in Baden and the Palatinate was the end of the German revolutionary uprisings that had begun in the spring of 1848.

Prussia

On 13 March, after warnings by the police against public demonstrations went unheeded, the army charged a group of people returning from a meeting in the Tiergarten, leaving one person dead and many injured. On 18 March, a large demonstration occurred. After two shots were fired, fearing that some of the 20,000 soldiers would be used against them, demonstrators erected barricades, and a battle ensued until troops were ordered 13 hours later to retreat, leaving hundreds dead. Afterwards, Frederick William attempted to reassure the public that he would proceed with reorganizing his government. The King also approved arming the citizens.

On 13 March, after warnings by the police against public demonstrations went unheeded, the army charged a group of people returning from a meeting in the Tiergarten, leaving one person dead and many injured. On 18 March, a large demonstration occurred. After two shots were fired, fearing that some of the 20,000 soldiers would be used against them, demonstrators erected barricades, and a battle ensued until troops were ordered 13 hours later to retreat, leaving hundreds dead. Afterwards, Frederick William attempted to reassure the public that he would proceed with reorganizing his government. The King also approved arming the citizens.

In his memoirs, Field Marshal Alfred von Waldersee, who in March 1848 was a sixteen-year-old student at the Royal Prussian Cadet Corps, gave a vivid description of the revolutionary events in Berlin:

In his memoirs, Field Marshal Alfred von Waldersee, who in March 1848 was a sixteen-year-old student at the Royal Prussian Cadet Corps, gave a vivid description of the revolutionary events in Berlin:

Those March days of 1848 left the most lasting impression on us young soldiers. From the so-called alongside the Spree we could see the erection of the barricades on the . The outbreak began at different parts of the city at two o'clock in the afternoon of the 18th, our attention being called to it by the circumstance that shots were fired at the sentinels in front of the Franz Regiment's barracks, which adjoined those of the Cadet Corps. The report went that the Cadet Corps, that breeding place of reaction, was to be up rooted ic This put our superior officers in a very awkward predicament; all connection with the outer world was cut off, and the Franz Regiment, which had been quartered next door to us, had been moved away, so we had to decide for ourselves what to do. General von Below was a feeble old man, Lieut.-Colonel Richter and our company commanders were all elderly—most of them had taken part in the War of Liberation—and some of them were no good as officers, so it was small wonder if a lack of vigour or decision was displayed. It was under debate whether we should not abstain from any attempt at resistance, when the senior lieutenant, Besserer von Dahlfingen, of my company, an exceptionally small man, spoke out at the Council of War and declared that it would be a disgrace if we surrendered to the Revolutionaries without a blow. Thereupon it was resolved to put up a fight. Our main position was to be on the first floor, led, up to by four stone staircases, each of which was allotted to a company. Our firearms, which had been placed in hiding already, were taken out again, and we began to block up the entrances to the staircases. Unfortunately we had no ammunition! This lack was in some degree made good by such officers as were sportsmen and had some powder and shot to distribute, so that firing might have been done by each of the companies; percussion-caps we secured from the Franz Regiment's barracks. However, things were not to become serious, for a battalion of the 1st Regiment of Guards pushed forward to the Marschallbrücke and averted all possibility of danger for us. The noise of the fighting died down now a little, only to revive again in the evening. The advanced to theOn 21 March, crowds of people gathered in Berlin to present their demands in an "address to the king". King Frederick William IV, taken by surprise, verbally yielded to all the demonstrators' demands, including parliamentary elections, a constitution, and freedom of the press. He promised that "Prussia was to be merged forthwith into Germany." The next day the King proceeded through the streets of Berlin to attend a mass funeral at the Friedrichshain cemetery for the civilian victims of the uprising. He and his ministers and generals wore the revolutionary tricolor of black, red, and gold. Polish prisoners, who had been jailed for planning a rebellion in formerly Polish territories now ruled by Prussia, were liberated and paraded through the city to the acclaim of the people. The 254 persons killed during the riots were laid out on catafalques on theAlexanderplatz (, ''Alexander Square'') is a large public square and transport hub in the central Mitte district of Berlin. The square is named after the Russian Tsar Alexander I, which also denotes the larger neighbourhood stretching from in the north-ea ...from the Frankfurter Gate, amidst the same kind of continuous but unsystematic fighting which the Guards also had encountered. Early in the morning of the 19th—it may have been about 4 o'clock, the shooting had been followed by silence throughout the city—we were given the alarm and had to don our cloaks and fall in with our guns and march to the Schloss (the Royal Palace in Berlin), by order of General von Prittwitz. We set out just as day was breaking. In the Königstrasse we passed three or four deserted barricades; we could see that most of the windows in the street were broken and that all the houses showed marks of bullets. Arrived at the Schloss, led by General von Below, himself afoot, we were ushered through "Portal No. I" into the Castle Yard, where General von Prittwitz was to be seen mounted on a chestnut with some officers round about him. We had now to down arms and we began almost to freeze in the cold morning air. It was very pleasant for us, therefore, when we were taken, troop by troop, into the kitchen, and given coffee. There was now a lively ''va-et-vient'' of mounted aides-de-camp, and others in the Castle Yard. The streets through which we had passed, and the open places outside the Schloss, had, of course, been empty. Now we saw many waggons icand bodies of troops bivouacking. Prisoners were being brought in every now and again and taken into the Castle cellars. After a wait of two hours or so we were given orders to march back toPotsdam Potsdam () is the capital and largest city of the Germany, German States of Germany, state of Brandenburg. It is part of the Berlin/Brandenburg Metropolitan Region. Potsdam sits on the Havel, River Havel, a tributary of the Elbe, downstream of B ....

Gendarmenmarkt

The is a square in Berlin and the site of an architectural ensemble that includes the Berlin concert hall, along with the French and German Churches. In the centre of the square stands a monumental statue of poet Friedrich Schiller. The ...

. Some 40,000 people accompanied these fallen demonstrators to their burial place at Friedrichshain.

A Constituent National Assembly was elected from various German states in late April and early May 1848 and gathered in St. Paul's Church in Frankfurt am Main on 18 May 1848. The deputies consisted of 122 government officials, 95 judges, 81 lawyers, 103 teachers, 17 manufacturers and wholesale dealers, 15 physicians, and 40 landowners. A majority of the Assembly were liberals. It became known as the "professors' parliament", as many of its members were academics in addition to their other responsibilities. The one working-class member was Polish and, like colleagues from the

A Constituent National Assembly was elected from various German states in late April and early May 1848 and gathered in St. Paul's Church in Frankfurt am Main on 18 May 1848. The deputies consisted of 122 government officials, 95 judges, 81 lawyers, 103 teachers, 17 manufacturers and wholesale dealers, 15 physicians, and 40 landowners. A majority of the Assembly were liberals. It became known as the "professors' parliament", as many of its members were academics in addition to their other responsibilities. The one working-class member was Polish and, like colleagues from the Tyrol

Tyrol ( ; historically the Tyrole; ; ) is a historical region in the Alps of Northern Italy and western Austria. The area was historically the core of the County of Tyrol, part of the Holy Roman Empire, Austrian Empire and Austria-Hungary, f ...

, not taken seriously.

Starting on 18 May 1848, the Frankfurt Assembly worked to find ways to unite the various German states and to write a constitution. The Assembly was unable to pass resolutions and dissolved into endless debate.

On 22 May 1848, another elected assembly sat for the first time in Berlin. They were elected under the law of 8 April 1848, which allowed for universal manhood suffrage and a two-stage voting system. Most of the deputies elected to the Prussian National Assembly were members of the burghers or liberal bureaucracy. They set about the task of writing a constitution "by agreement with the Crown", but on 9 November, before it had completed its work, the Assembly was adjourned and "for its own safety" moved to Brandenburg an der Havel

Brandenburg an der Havel (; ) is a town in Brandenburg, Germany, which served as the capital of the Margraviate of Brandenburg until it was replaced by Berlin in 1417.

With a population of 72,040 (as of 2020), it is located on the banks of the ...

.

Saxony

InDresden

Dresden (; ; Upper Saxon German, Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; , ) is the capital city of the States of Germany, German state of Saxony and its second most populous city after Leipzig. It is the List of cities in Germany by population, 12th most p ...

, the capital of the Kingdom of Saxony

The Kingdom of Saxony () was a German monarchy in Central Europe between 1806 and 1918, the successor of the Electorate of Saxony. It joined the Confederation of the Rhine after the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, later joining the German ...

, the people took to the streets asking King Frederick Augustus II of Saxony to engage in electoral reform, social justice and for a constitution.

German composer Richard Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, essayist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most o ...

passionately engaged himself in the revolution in Dresden, supporting the democratic-republican movement. Later during the May Uprising in Dresden

The May Uprising took place in Dresden, Kingdom of Saxony in 1849; it was one of the last of the series of events known as the Revolutions of 1848.

Events leading to the May Uprising

In the German states, revolutions began in March 1848, start ...

from 3–9 May 1849, he supported the provisional government. Others participating in the Uprising were the Russian revolutionary Michael Bakunin

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin. Sometimes anglicized to Michael Bakunin. ( ; – 1 July 1876) was a Russian revolutionary anarchist. He is among the most influential figures of anarchism and a major figure in the revolutionary socialist, so ...

and the German working-class leader Stephen Born. In all, about 2,500 combatants manned the barricades during the May Uprising. On 9 May 1849, together with the leaders of the uprising, Wagner left Dresden for Switzerland to avoid arrest. He spent a number of years in exile abroad, in Switzerland, Italy, and Paris. Finally the government lifted its ban against him and he returned to Germany.

Since the revolutionary events of 1830, Saxony had been ruled as a constitutional monarchy with a two-chamber legislature and an accountable ministry. This constitution continued to serve as the basis of the Saxon government until 1918. The Revolution of 1848 brought more popular reforms in the government of Saxony.

In 1849, many Saxon residents emigrated to the United States, including Michael Machemehl. They landed in Galveston, Texas

Galveston ( ) is a Gulf Coast of the United States, coastal resort town, resort city and port off the Southeast Texas coast on Galveston Island and Pelican Island (Texas), Pelican Island in the U.S. state of Texas. The community of , with a pop ...

, and created what became the German Texan

Texas Germans () are descendants of Germans who settled in Texas since the 1830s. The arriving Germans tended to cluster in ethnic enclaves; the majority settled in a broad, fragmented belt across the south-central part of the state, where many be ...

community. In mid-century, some lived in cities, but many developed substantial farms to the west in Texas.

The Rhineland or Rhenish Prussia

The Rhineland shared a common history with the Rhenish Hesse, Luxembourg and the Palatinate of having been under the control of Revolutionary and then Napoleonic France from 1795. His rule established social, administrative and legislative measures that broke up the feudal rule that the clergy and the nobility had exercised over the area previously. The soil of the Rhineland is not the best for agriculture, but forestry has traditionally been a strong industry there. The relative lack of agriculture, late 18th-century elimination of the feudal structure, and the strong logging industry contributed to the industrialization of the Rhineland. With nearby sources of coal in the Mark, and access via the Rhine to theNorth Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Denmark, Norway, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. A sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian Se ...

, the west bank of the Rhine in the Rhineland became the premier industrial area in Germany in the 19th century. By 1848, the towns of Aachen

Aachen is the List of cities in North Rhine-Westphalia by population, 13th-largest city in North Rhine-Westphalia and the List of cities in Germany by population, 27th-largest city of Germany, with around 261,000 inhabitants.

Aachen is locat ...

, Cologne

Cologne ( ; ; ) is the largest city of the States of Germany, German state of North Rhine-Westphalia and the List of cities in Germany by population, fourth-most populous city of Germany with nearly 1.1 million inhabitants in the city pr ...

and Düsseldorf

Düsseldorf is the capital city of North Rhine-Westphalia, the most populous state of Germany. It is the second-largest city in the state after Cologne and the List of cities in Germany with more than 100,000 inhabitants, seventh-largest city ...

were heavily industrialized, with a number of different industries represented. At the beginning of the 19th century, more than 90% of the population of the Rhineland was engaged in agriculture (including lumbering), but by 1933, only 12% were still working in agriculture

By 1848, a large industrial working class, the proletariat, had developed and, owing to Napoleonic France, the level of education was relatively high and it was politically active. While in other German states the liberal petty bourgeoisie

''Petite bourgeoisie'' (, ; also anglicised as petty bourgeoisie) is a term that refers to a social class composed of small business owners, shopkeepers, small-scale merchants, semi-autonomous peasants, and artisans. They are named as such ...

led the uprisings of 1848, in the Rhineland the proletariat was asserting its interests openly against the bourgeoisie as early as 1840.

In 1848, Prussia controlled the Rhineland as part of "Western Prussia", having first acquired territory in this area in 1614. During the Napoleonic Era, as noted above, the Rhineland west of the Rhine had been incorporated into France and its feudal structures dismantled. But, following the defeat of Napoleon in 1814, Prussia took over the west bank of the Rhineland. Its government treated the Rhinelanders as subjects and alien peoples, and it began to reinstate the hated feudal structures. Much of the revolutionary impulse in the Rhineland in 1848 was colored by a strong anti-Prussian feeling. The Rhinelanders took careful note of the announcement by King Frederick William IV on 18 March 1848, in Berlin that a United Diet would be formed and that other democratic reforms would be instituted. Elections for the United Diet were indirect. The elections were conducted on the basis of universal male suffrage, and they were to choose the members of the United Diet. Rhinelanders remained hopeful regarding this progress and did not participate in the early round of uprisings that were occurring in other parts of Germany.

The Prussian government mistook this quietude in the Rhineland for loyalty to the autocratic Prussian government. The Prussian government began offering military assistance to other states in suppressing the revolts in their territories and cities, ''i.e''. Dresden, the Palatinate, Baden, Wűrttemberg, Franconia, ''etc''. Soon the Prussians discovered that they needed additional troops in this effort. Taking the loyalty of the Rhineland for granted, in the spring of 1849 the Prussian government called up a large portion of the army reserve—the ''

The Prussian government mistook this quietude in the Rhineland for loyalty to the autocratic Prussian government. The Prussian government began offering military assistance to other states in suppressing the revolts in their territories and cities, ''i.e''. Dresden, the Palatinate, Baden, Wűrttemberg, Franconia, ''etc''. Soon the Prussians discovered that they needed additional troops in this effort. Taking the loyalty of the Rhineland for granted, in the spring of 1849 the Prussian government called up a large portion of the army reserve—the ''Landwehr

''Landwehr'' (), or ''Landeswehr'', is a German language term used in referring to certain national army, armies, or militias found in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Europe. In different context it refers to large-scale, low-strength fo ...

'' in Westphalia and the Rhineland. This action was opposed: the order to call up the affected all males under the age of 40 years, and such a call up was to be done only in time of war, not in peacetime, when it was considered illegal. The Prussian King dissolved the Second Chamber of the United Diet because on 27 March 1849 it passed an unpopular constitution. The entire citizenry of the Rhineland, including the petty bourgeoisie, the grand bourgeoisie and the proletariat, rose up to protect the political reforms which they believed were slipping away.

On 9 May 1849, uprisings occurred in the Rhenish towns of Elberfeld

Elberfeld is a municipal subdivision of the Germany, German city of Wuppertal; it was an independent town until 1929.

History

The first official mentioning of the geographic area on the banks of today's Wupper River as "''elverfelde''" was ...

, Düsseldorf, Iserlohn

Iserlohn (; Westphalian language, Westphalian: ''Iserlaun'') is a city in the Märkischer Kreis district, in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. It is the largest city by population and area within the district and the Sauerland region.

Geogr ...

and Solingen

Solingen (; ) is a city in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, 25 km east of Düsseldorf along the northern edge of the Bergisches Land, south of the Ruhr. After Wuppertal, it is the second-largest city in the Bergisches Land, and a member of ...

. The uprising in Düsseldorf was suppressed the following day on 10 May 1849. In the town of Elberfeld, the uprising showed strength and persistence, as 15,000 workers took to the streets and erected barricades; they confronted the Prussian troops sent to suppress the unrest and to collect a quota of conscripts. In the end, the troops collected only about 40 conscripts from Elberfeld. A Committee of Public Safety was formed in the town, to organize the citizens in revolt. Members of the Committee included Karl Nickolaus Riotte, a democrat and a lawyer in Elberfeld; Ernst Hermann Höchster, another lawyer and democrat, elected as chairman of the Committee, and Alexis Heintzmann, a lawyer and a liberal who was also the public prosecutor in Elberfeld. Members of the Palatinate provisional government included Nikolaus Schmitt, serving as Minister of the Interior, and Theodor Ludwig Greiner. Karl Hecker, Franz Heinrich Zitz and Ludwig Blenker were among the other of the leaders of the Elberfeld uprising.

The members of the Committee for Public Safety could not agree on a common plan, let alone control the various groups taking part in the uprising. The awakened working classes were pursuing their goals with single-minded determination. Citizen-military forces (paramilitary) organized to support the uprising. Military leaders of these forces included August Willich and Feliks Trociński and Captain Christian Zinn. On 17 May through 18, 1849, a group of workers and democrats from Trier and neighboring townships stormed the arsenal at Prüm

Prüm () is a town in the Westeifel (Rhineland-Palatinate), Germany. Formerly a district capital, today it is the administrative seat of the ''Verbandsgemeinde'' ("collective municipality") Prüm (Verbandsgemeinde), Prüm.

Geography

Prüm lies o ...

to obtain arms for the insurgents. Workers from Solingen stormed the arsenal at Gräfrath and obtained arms and cartridges for the insurgents. (As noted above under the heading on "The Palatinate") Frederick Engels was active in the uprising in Elberfeld from 11 May 1849 until the end of the revolt. On 10 May 1849, he was in Solingen and making his way toward Elberfeld. He obtained two cases of cartridges from the arsenal at Gräfrath and carried them to Elberfeld.

The upper bourgeoisie were frightened by the armed working classes taking to the streets. They began to separate themselves from the movement for constitutional reform and the Committee of Public Safety, describing the leaders as bloodthirsty terrorists. Leaders of the Committee, who were mostly petty bourgeoisie, were starting to vacillate. Rather than working to organize and direct the various factions of protests, they began to draw back from the revolutionary movement, especially the destruction of property. The Committee of Public Safety tried to calm the reformist movement and quell the demonstrations.

Bavaria

InBavaria

Bavaria, officially the Free State of Bavaria, is a States of Germany, state in the southeast of Germany. With an area of , it is the list of German states by area, largest German state by land area, comprising approximately 1/5 of the total l ...

, King Ludwig I lost prestige because of his open relationship with his favourite mistress Lola Montez, a dancer and actress unacceptable to the aristocracy and the Church. She tried to launch liberal reforms through a Protestant prime minister, which outraged the state's Catholic conservatives. On 9 February, conservatives came out onto the streets in protest. This 9 February 1848, demonstration was the first in that revolutionary year. It was an exception among the wave of liberal protests. The conservatives wanted to be rid of Lola Montez, and had no other political agenda. Liberal students took advantage of the Lola Montez affair to stress their demands for political change. All over Bavaria, students started demonstrating for constitutional reform, just as students were doing in other cities.

Ludwig tried to institute a few minor reforms but they proved insufficient to quell the storm of protests. On 16 March 1848, Ludwig I abdicated in favor of his eldest son Maximilian II. Ludwig complained that "I could not rule any longer, and I did not want to give up my powers. In order to not become a slave, I became a lord." Although some popular reforms were introduced, the government regained full control.

Liechtenstein

Encouraged by similar uprisings the same year, demonstrations emerged which caused increased opposition against the absolute monarchy of Aloys II. The aim of the revolution was to improve the economic and political situation of ordinary citizens in Liechtenstein, primarily fuelled by the worsening economy in the country in the years prior. On 22 March 1848, the people's committee appointed a three-person committee to lead the Liechtenstein revolutionary movement, which includedPeter Kaiser

Peter Kaiser (born 4 December 1958) is an Austrian politician of the Social Democratic Party of Austria, Social Democratic Party. Since March 2013 he is List of governors of Carinthia, governor of Carinthia and since March 2010 also chairman of ...

, Karl Schädler and Ludwig Grass. Together, they managed to maintain order in Liechtenstein and formed a constitutional council. Liechtenstein was a member of the National Assembly in Frankfurt until April 1849.

Following the revolution, a constitutional council was elected on 27 July 1848 in response to popular demand from the revolutionaries, of which Schädler was elected as its president. The primary task of the council was the creation the draft for a new Liechtenstein constitution, of which the work was done primarily by him and Michael Menzinger. The District Council was formed on 7 March 1849 with 24 elected representatives and acted as the first democratic representation in Liechtenstein, with Schädler was elected as District Administrator. However, after the failure of the German revolutions, Aloys II once again instated absolute power over Liechtenstein on 20 July 1852 and disbanded the district council.

Greater Poland and Pomerelia

While technically neitherGreater Poland

Greater Poland, often known by its Polish name Wielkopolska (; ), is a Polish Polish historical regions, historical region of west-central Poland. Its chief and largest city is Poznań followed by Kalisz, the oldest city in Poland.

The bound ...

nor Pomerelia

Pomerelia, also known as Eastern Pomerania, Vistula Pomerania, and also before World War II as Polish Pomerania, is a historical sub-region of Pomerania on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in northern Poland.

Gdańsk Pomerania is largely c ...

were German states, the respective roughly corresponding territories of the Grand Duchy of Posen

The Grand Duchy of Posen (; ) was part of the Kingdom of Prussia, created from Prussian Partition, territories annexed by Prussia after the Partitions of Poland, and formally established following the Congress of Vienna in 1815. On 9 February 1 ...

and West Prussia

The Province of West Prussia (; ; ) was a province of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and from 1878 to 1919. West Prussia was established as a province of the Kingdom of Prussia in 1773, formed from Royal Prussia of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonweal ...

had been under Prussian control since the First and Second Partition of Poland

The 1793 Second Partition of Poland was the second of partitions of Poland, three partitions (or partial annexations) that ended the existence of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth by 1795. The second partition (politics), partition occurred i ...

in the late 18th century. The Greater Poland Uprising of 1848, also known as the Posen Uprising, was an unsuccessful military insurrection of Polish troops under Ludwik Mierosławski against the Prussian forces. It began on 20 March 1848, and resulted in Prussia demoting the Grand Duchy to an ordinary Province of Posen

The Province of Posen (; ) was a Provinces of Prussia, province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1848 to 1920, occupying most of the historical Greater Poland. The province was established following the Greater Poland Uprising (1848), Poznań Uprisi ...

. Nevertheless, both Prussian-held Polish-speaking territories of Province of Posen and West Prussia

The Province of West Prussia (; ; ) was a province of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and from 1878 to 1919. West Prussia was established as a province of the Kingdom of Prussia in 1773, formed from Royal Prussia of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonweal ...

were formally integrated into Germany only 17 years later, upon foundation of the North German Confederation

The North German Confederation () was initially a German military alliance established in August 1866 under the leadership of the Kingdom of Prussia, which was transformed in the subsequent year into a confederated state (a ''de facto'' feder ...

in 1866.

National Assembly in Frankfurt

InHeidelberg

Heidelberg (; ; ) is the List of cities in Baden-Württemberg by population, fifth-largest city in the States of Germany, German state of Baden-Württemberg, and with a population of about 163,000, of which roughly a quarter consists of studen ...

, in the Grand Duchy of Baden, on 6 March 1848, a group of German liberals began to make plans for an election to a German national assembly. This provisional Parliament met on 31 March, in Frankfurt

Frankfurt am Main () is the most populous city in the States of Germany, German state of Hesse. Its 773,068 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the List of cities in Germany by population, fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located in the forela ...

's St. Paul's Church. Its members called for free elections to an assembly for all of Germany – and the German states agreed.

Finally, on 18 May 1848, the National Assembly opened its session in St. Paul's Church. Of the 586 delegates of the first freely elected German parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

, so many were professors (94), teachers (30) or had a university education (233) that it was called a "professors' parliament" ("").

There were few practical politicians. Some 400 delegates can be identified in terms of political factions

A political faction is a group of people with a common political purpose, especially a subgroup of a political party that has interests or opinions different from the rest of the political party. Intragroup conflict between factions can lead to ...

– usually named after their meeting places:

* Café Milani – Right/Conservative (40)

* Casino

A casino is a facility for gambling. Casinos are often built near or combined with hotels, resorts, restaurants, retail shops, cruise ships, and other tourist attractions. Some casinos also host live entertainment, such as stand-up comedy, conce ...

– Right centre/Liberal-conservative (120)

* Landsberg – Centre/Liberal (40)

* Württemberger Hof – Left centre (100)

* Deutscher Hof – Left/Liberal democrats (60)

* Donnersberg

The Donnersberg (; literally: "thunder mountain") is the highest peak of the Palatinate () region of Germany. The mountain lies between the towns of Rockenhausen and Kirchheimbolanden, in the Donnersbergkreis district, which is named after th ...

– Far left/Democrats (40)

Under the chairmanship of the liberal politician Heinrich von Gagern, the assembly started on its ambitious plan to create a modern constitution as the foundation for a unified Germany.

From the beginning the main problems were regionalism, support of local issues over pan-German issues, and Austro-Prussian conflicts. Archduke John of Austria

Archduke John of Austria (, ; (or simply ''Nadvojvoda Janez''); 20 January 1782 – 11 May 1859), a member of the House of Habsburg-Lorraine, was an Austrian field marshal and imperial regent (''Reichsverweser'') of the short-lived German Emp ...

was chosen as a temporary head of state (""). This was an attempt to create a provisional executive power, but it did not get very far since most states failed to fully recognize the new government. The National Assembly lost reputation in the eyes of the German public when Prussia carried through its own political intentions in the Schleswig-Holstein Question

Schleswig-Holstein (; ; ; ; ; occasionally in English ''Sleswick-Holsatia'') is the northernmost of the 16 states of Germany, comprising most of the historical Duchy of Holstein and the southern part of the former Duchy of Schleswig. Its c ...

without the prior consent of Parliament. A similar discrediting occurred when Austria suppressed a popular uprising in Vienna by military force.

Nonetheless, discussions on the future constitution had started. The main questions to be decided were:

* Should the new united Germany include the German-speaking areas of Austria and thus separate these territories constitutionally from the remaining areas of the Habsburg Empire ("greater German solution"), or should it exclude Austria, with leadership falling to Prussia ("smaller German solution")? Finally, this question was settled when the Austrian Chancellor introduced a centralised constitution for the entire Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire, officially known as the Empire of Austria, was a Multinational state, multinational European Great Powers, great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the Habsburg monarchy, realms of the Habsburgs. Duri ...

, thus delegates had to give up their hopes for a "Greater Germany".

* Should Germany become a hereditary monarchy

A hereditary monarchy is a form of government and succession of power in which the throne passes from one member of a ruling family to another member of the same family. A series of rulers from the same family would constitute a dynasty. It is ...

, have an elected monarch, or even become a republic?

* Should it be a federation of relatively independent states or have a strong central government?

Soon events began to overtake discussions. Delegate Robert Blum had been sent to Vienna by his left-wing political colleagues on a fact-finding mission to see how Austria's government was rolling back liberal achievements by military force. Blum participated in the street fighting, was arrested and executed on 9 November, despite his claim to immunity from prosecution as a member of the National Assembly.

Although the achievements of the March Revolution were rolled back in many German states, the discussions in Frankfurt continued, increasingly losing touch with events.

In December 1848 the "Basic Rights for the German People" proclaimed equal rights for all citizens before the law. On 28 March 1849, the draft of the constitution was finally passed. The new Germany was to be a constitutional monarchy

Constitutional monarchy, also known as limited monarchy, parliamentary monarchy or democratic monarchy, is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in making decisions. ...

, and the office of head of state ("Emperor of the Germans") was to be hereditary and held by the respective King of Prussia. The latter proposal was carried by a mere 290 votes in favour, with 248 abstentions. The constitution was recognized by 29 smaller states but not by Austria, Prussia, Bavaria, Hanover

Hanover ( ; ; ) is the capital and largest city of the States of Germany, German state of Lower Saxony. Its population of 535,932 (2021) makes it the List of cities in Germany by population, 13th-largest city in Germany as well as the fourth-l ...

and Saxony.

Backlash in Prussia

By late 1848, the Prussian aristocrats and generals had regained power in Berlin. They had not been defeated permanently during the incidents of March, but had only retreated temporarily. General von Wrangel led the troops who recaptured Berlin for the old powers, and KingFrederick William IV of Prussia

Frederick William IV (; 15 October 1795 – 2 January 1861), the eldest son and successor of Frederick William III of Prussia, was King of Prussia from 7 June 1840 until his death on 2 January 1861. Also referred to as the "romanticist on the th ...

immediately rejoined the old forces. In November, the king dissolved the Prussian National Assembly and put forth a constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organization or other type of entity, and commonly determines how that entity is to be governed.

When these pri ...

of his own which was based upon the work of the Assembly yet maintained the ultimate authority of the king. Revised in 1850 and amended frequently in the following years, the constitution provided for an appointed upper house, the House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the lower house, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England. One of the oldest ext ...

, and a lower house, the Prussian House of Representatives, House of Representatives, elected by universal manhood suffrage but under a Prussian three-class franchise, three-class system of voting (""): representation was proportional to taxes paid, so that more than 80% of the electorate controlled only one-third of the seats. Otto von Bismarck was a member of the first ''Landtag of Prussia, Landtag'' elected under the new constitution.

On 2 April 1849, a delegation of the National Assembly met with King Frederick William IV in Berlin and offered him the crown of the Emperor under this new constitution. Frederick William told the delegation that he felt honoured but could only accept the crown with the consent of his peers, the other sovereign monarchs and free cities. But later, in a letter to a relative in England, he wrote that he felt deeply insulted by being offered a crown "from the gutter", "disgraced by the stink of revolution, defiled with dirt and mud".

Austria and Prussia withdrew their delegates from the Assembly, which was now little more than a debating club. The radical members were forced to go to Stuttgart, where they sat from 6–18 June as a rump parliament until it too was dispersed by Army of Württemberg, Württemberg troops. Armed uprisings in support of the constitution, especially in Saxony, the Palatinate and Baden were short-lived, as the local militaries, aided by Prussian troops, crushed them quickly. Leaders and participants, if caught, were executed or sentenced to long prison terms.

The achievements of the revolutionaries of March 1848 were reversed in all of the German states and by 1851, the Basic Rights had also been abolished nearly everywhere. In the end, the revolution fizzled because of the divisions between the various factions in Frankfurt, the calculating caution of the liberals, the failure of the left to marshal popular support and the overwhelming superiority of the monarchist forces.

Many disappointed German patriots went to the United States, among them most notably Carl Schurz, Franz Sigel and Friedrich Hecker

Friedrich Karl Franz Hecker (September 28, 1811 – March 24, 1881) was a German lawyer, politician and revolutionary. He was one of the most popular speakers and agitators of the 1848 Revolution. After moving to the United States, he served a ...

. Such emigrants became known as the Forty-Eighters.

Failure of the revolution