German Corpse Factory on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The German Corpse Factory or ' (literally "Carcass-Utilization Factory"), also sometimes called the "German Corpse-Rendering Works" or "

The German Corpse Factory or ' (literally "Carcass-Utilization Factory"), also sometimes called the "German Corpse-Rendering Works" or "

The German Corpse Factory or ' (literally "Carcass-Utilization Factory"), also sometimes called the "German Corpse-Rendering Works" or "

The German Corpse Factory or ' (literally "Carcass-Utilization Factory"), also sometimes called the "German Corpse-Rendering Works" or "Tallow

Tallow is a rendered form of beef or mutton suet, primarily made up of triglycerides.

In industry, tallow is not strictly defined as beef or mutton suet. In this context, tallow is animal fat that conforms to certain technical criteria, inc ...

Factory" was a recurring work of atrocity propaganda

Atrocity propaganda is the spreading of information about the crimes committed by an enemy, which can be factual, but often includes or features deliberate fabrications or exaggerations. This can involve photographs, videos, illustrations, interv ...

among the Allies of World War I

The Allies or the Entente (, ) was an international military coalition of countries led by the French Republic, the United Kingdom, the Russian Empire, the United States, the Kingdom of Italy, and the Empire of Japan against the Central Powers ...

, describing the German Empire

The German Empire (),; ; World Book, Inc. ''The World Book dictionary, Volume 1''. World Book, Inc., 2003. p. 572. States that Deutsches Reich translates as "German Realm" and was a former official name of Germany. also referred to as Imperia ...

's supposed use of human corpses in fat rendering. In the postwar years, investigations in Britain and France revealed that these stories were false.

According to a typical version of the story, the was a special installation operated by the Germans in which, due to fat product scarcety amid the allied blockade, German battlefield corpses were rendered down for fat, which was then used to manufacture nitroglycerine

Nitroglycerin (NG) (alternative spelling nitroglycerine), also known as trinitroglycerol (TNG), nitro, glyceryl trinitrate (GTN), or 1,2,3-trinitroxypropane, is a dense, colorless or pale yellow, oily, explosive liquid most commonly produced by ...

, candles, lubricants, and even boot dubbin. It was supposedly operated behind the front lines by the DAVG — ' ("German Waste Utilization Company").

Historian Piers Brendon has called it "the most appalling atrocity story" of World War I, while journalist Phillip Knightley has called it "the most popular atrocity story of the war." After the war, John Charteris, the former Chief of Intelligence at the British Expeditionary Force, allegedly stated in a speech that he had invented the story for propaganda purposes, with the principal aim of getting the Chinese to join the war against Germany.

Recent scholars do not credit the claim that Charteris created the story. Propaganda historian Randal Marlin says "the real source for the story is to be found in the pages of the Northcliffe press", referring to newspapers owned by Lord Northcliffe. Adrian Gregory presumes that the story originated from rumours that had been circulating for years, and that it was not "invented" by any individual: "The corpse-rendering factory was not the invention of a diabolical propagandist; it was a popular folktale, an 'urban myth

Urban legend (sometimes modern legend, urban myth, or simply legend) is a genre of folklore concerning stories about an unusual (usually scary) or humorous event that many people believe to be true but largely are not.

These legends can be e ...

', which had been circulated for months before it received any official notice."Gregory, Adrian (2008). ''The Last Great War. British Society and the First World War'', Cambridge University Press, p. 57.

History

Rumours and cartoons

Rumours that the Germans used the bodies of their soldiers to create fat appear to have been circulating by 1915. Cynthia Asquith noted in her diary on 16 June 1915: “We discussed the rumour that the Germans utilise even their corpses by converting them into glycerine with the by-product of soap.”Neander, Joachim, ''The German Corpse Factory. The Master Hoax of British Propaganda in the First World War'', Saarland University Press, 2013, pp.79-85. Such stories also appeared in the American press in 1915 and 1916. The French press also took it up in ', in February, 1916. In 1916 a book of cartoons by Louis Raemaekers was published. One depicted bodies of German soldiers being loaded onto a cart in neatly packaged batches. This was accompanied with a comment written by Horace Vachell: “I am told by an eminent chemist that six pounds of glycerine can be extracted from the corpse of a fairly well nourished Hun... These unfortunates, when alive, were driven ruthlessly to inevitable slaughter. They are sent as ruthlessly to the blast furnaces. One million dead men are resolved into six million pounds of glycerine." A later cartoon byBruce Bairnsfather

Captain Charles Bruce Bairnsfather (9 July 188729 September 1959) was a prominent British humour, humorist and cartoonist. His best-known cartoon character is Old Bill (comics), Old Bill. Bill and his pals Bert and Alf featured in Bairnsfather's ...

also referred to the rumour, depicting a German munitions worker looking at a can of glycerine and saying "Alas! My poor Brother!" (parodying a well-known advertisement for Bovril

Bovril is a thick and salty meat extract paste, similar to a yeast extract, developed in the 1870s by John Lawson Johnston. It is sold in a distinctive bulbous jar and as cubes and granules. Its appearance is similar to the British Marmite and ...

).

By 1917 the British and their allies were hoping to bring China into the war against Germany. On 26 February 1917 the English-language ''North-China Daily News'' published a story that the Chinese President Feng Guozhang

Feng Guozhang (; 7 January 1859 – 12 December 1919) was a Chinese general and politician in the late Qing dynasty and early republican China who was Vice President from 1916 to 1917 and then acting President of the Republic of China from 1917 ...

had been horrified by Admiral Paul von Hintze's attempts to impress him when the "Admiral triumphantly stated that they were extracting glycerine out of dead soldiers!". The story was picked up by other papers.

In all these cases the story was told as rumour, or as something heard from people supposed to be 'in the know'. It was not presented as documented fact.

The Corpse factory

The first English language account of a real and locatable ' appeared in the 16 April 1917 issue of ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

'' of London. In a short piece at the foot of its "Through German Eyes" review of the German press, it quoted from a recent issue of the German newspaper ' a very brief story by reporter Karl Rosner of only 59 words in length, which described the bad smell coming from a "" rendering factory, making no reference to the corpses being human. The following day, 17 April 1917, the story was repeated more prominently in editions of ''The Times'' and ''Daily Mail

The ''Daily Mail'' is a British daily Middle-market newspaper, middle-market Tabloid journalism, tabloid conservative newspaper founded in 1896 and published in London. , it has the List of newspapers in the United Kingdom by circulation, h ...

'' (both owned by Lord Northcliffe at the time), ''The Times'' running it under the title ''Germans and their Dead'', in the context of a 500-plus word story which the editorial introduction stated came from the 10 April edition of the Belgian newspaper ' published in England, which in turn had received it from ', another Belgian newspaper published in Leiden

Leiden ( ; ; in English language, English and Archaism, archaic Dutch language, Dutch also Leyden) is a List of cities in the Netherlands by province, city and List of municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality in the Provinces of the Nethe ...

, The Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

. The Belgian account stated specifically that the bodies were those of soldiers and interpreted the word "" as a reference to human corpses.

The story described how corpses arrived by rail at the factory, which was placed "deep in forest country" and surrounded by an electrified fence, and how they were rendered for their fats which were then further processed into stearin

Stearin , or tristearin, or glyceryl tristearate is an odourless, white powder. It is a triglyceride derived from three units of stearic acid. Most triglycerides are derived from at least two and more commonly three different fatty acids. Like ...

(a form of tallow). It went on to claim that this was then used to make soap, or refined into an oil "of yellowish brown colour". The supposedly incriminating passage in the original German article was translated in the following words:

A debate followed in the pages of ''The Times'' and other papers. ''The Times'' stated that it had received a number of letters "questioning the translation of the German word Kadaver, and suggesting that it is not used of human bodies. As to this, the best authorities are agreed that it is also used of the bodies of animals." Letters were also received confirming the story from Belgian and Dutch sources and later from Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

.

''The'' ''New York Times'' reported on 20 April that the article was being credited by all the French newspapers with the exception of the ', which preferred to believe that the corpses in question were those of animals rather than humans. ''The New York Times'' itself did not credit the story, pointing out that it appeared in early April and that German newspapers traditionally indulged in April Fools' Day

April Fools' Day or April Fool's Day (rarely called All Fools' Day) is an annual custom on the 1st of April consisting of practical jokes, hoaxes, and pranks. Jokesters often expose their actions by shouting "April Fool " at the recipient. ...

pranks, and also that the expression "Kadaver" was not employed in current German usage to mean a human corpse, the word "Leichnam" being used instead. The only exception was corpses used for dissection—cadavers.

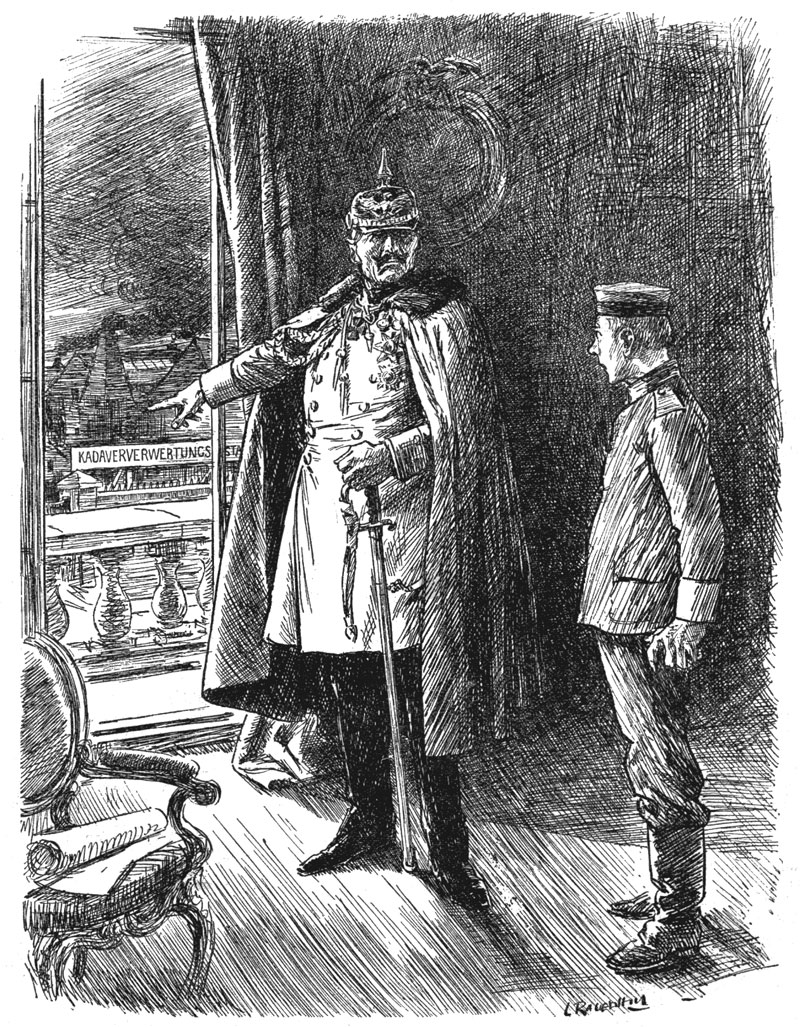

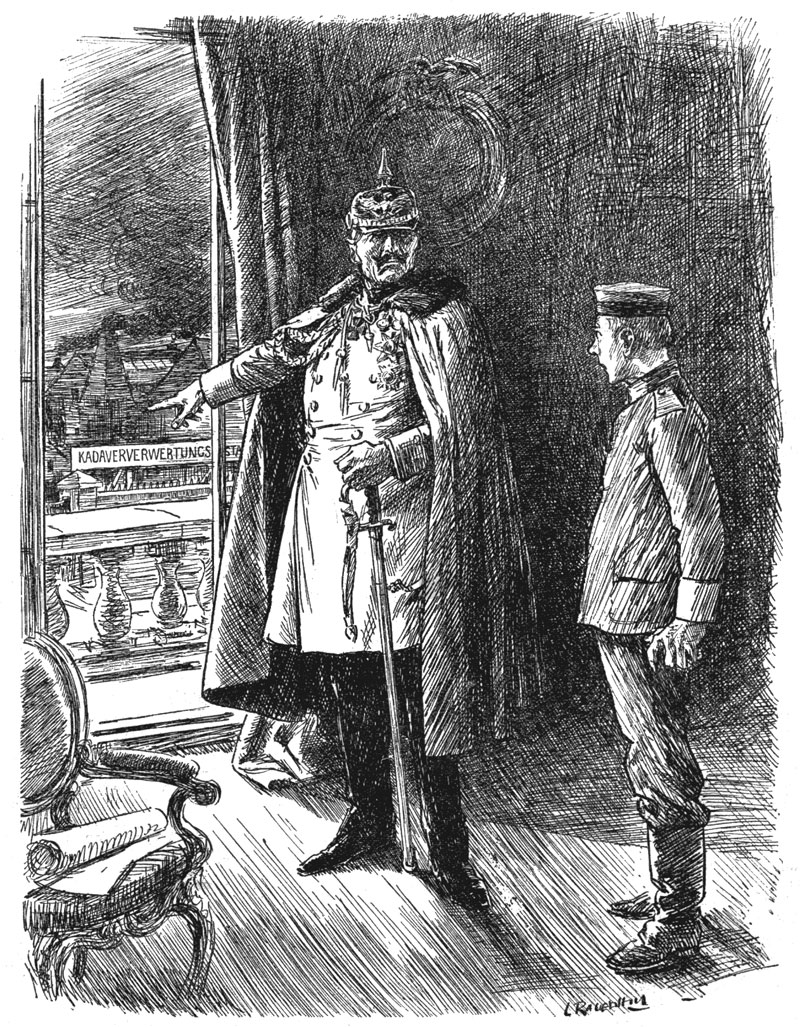

On 25 April the weekly British humorous magazine '' Punch'' printed a cartoon entitled "Cannon-Fodder—and After," which showed the Kaiser and a German recruit. Pointing out of a window at a factory with smoking chimneys and the sign "," the Kaiser tells the young man: "And don't forget that your Kaiser will find a use for you—alive or dead."

On 30 April the story was raised in the House of Commons, and the government declined to endorse it. Lord Robert Cecil declared that he had no information beyond newspaper reports. He added that, "in view of other actions by German military authorities, there is nothing incredible in the present charge against them." However, the government, he said, had neither the responsibility nor the resources to investigate the allegations. In the months that followed, the account of the ' circulated worldwide, but never expanded beyond the account printed in ''The Times''; no eyewitnesses ever appeared, and the story was never enlarged or amplified.

Some individuals within the government nonetheless hoped to exploit the story, and Charles Masterman

Charles Frederick Gurney Masterman Privy Council of the United Kingdom, PC Member of parliament, MP (24 October 1873 – 17 November 1927) was a British radical Liberal Party (UK), Liberal Party politician, intellectual and man of letters. He ...

, director of the War Propaganda Bureau at Wellington House, was asked to prepare a short pamphlet. This was never published, however. Masterman and his mentor, Prime Minister David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. A Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, he was known for leadi ...

, never took the story seriously. An undated anonymous pamphlet entitled ''A 'corpse-conversion' Factory: A Peep Behind the German Lines'' was published by Darling & Son, probably around this time in 1917.

A month later, ''The Times'' revived the rumour by publishing a captured German Army order that made reference to a factory. It was issued by the , which ''The Times'' interpreted as ' ("instructions department"). The ', however, insisted that it stood for ' (veterinary station). The Foreign Office agreed that order could only be referring to "the carcasses of horses."

Paul Fussell

Paul Fussell Jr. (22 March 1924 – 23 May 2012) was an American cultural and literary historian, author and university professor. His writings cover a variety of topics, from scholarly works on eighteenth-century English literature to commentary ...

has also suggested that this may have been a deliberate British mistranslation of the phrase ' on a captured German order that all available animal remains be sent to an installation to be reduced to tallow.

Postwar claims

Charteris' speech

On 20 October 1925, the ''New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' reported on a speech given by Brigadier General John Charteris at the National Arts Club the previous evening. Charteris was then a Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

MP for Glasgow

Glasgow is the Cities of Scotland, most populous city in Scotland, located on the banks of the River Clyde in Strathclyde, west central Scotland. It is the List of cities in the United Kingdom, third-most-populous city in the United Kingdom ...

, but had served as Chief of Army Intelligence for part of the war. According to the '' Times'', the brigadier told his audience that he had invented the cadaver-factory story as a way of turning the Chinese against the Germans, and he had transposed the captions of two photographs that came into his possession, one showing dead soldiers being removed by train for funerals, the second showing a train car bearing horses to be processed for fertiliser. A subordinate had suggested forging a diary of a German soldier to verify the accusation, but Charteris vetoed the idea.Knightley, p. 105

On his return to the UK, Charteris unequivocally denied the ''New York Times'' report in a statement to ''The Times'', saying that he was only repeating speculation that had already been published in the 1924 book ''These Eventful Years: The Twentieth Century In The Making''. This referred to an essay by Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British philosopher, logician, mathematician, and public intellectual. He had influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, and various areas of analytic ...

, in which Russell asserted that,

Charteris stated that he had merely repeated Russell's speculations, adding the extra information about the proposed fake diary:

The question was once again raised in Parliament, and Sir Laming Worthington-Evans said that the story that the Germans had set up a factory for the conversion of dead bodies first appeared on 10 April 1917, in the ', and in the Belgian newspapers ' and '.

Sir Austen Chamberlain

Sir Joseph Austen Chamberlain (16 October 1863 – 16 March 1937) was a British statesman, son of Joseph Chamberlain and older half-brother of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. He served as a Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), Member of ...

finally established that the British government accepted that the story was untrue, when in a reply in Parliament on 2 December 1925 he said that the German Chancellor had authorised him to say on the authority of the German government, that there was never any foundation for the story, and that he accepted the denial on behalf of His Majesty's Government.

Interwar and World War II

The claim that Charteris invented the story to sway the opinion of the Chinese against the Germans was given wide circulation in Lord Arthur Ponsonby's highly influential book, '' Falsehood in War-Time'', which examined, according to its subtitle, an "Assortment of Lies Circulated Throughout the Nations During the Great War". In his 1931 book ''Spreading Germs of Hate'', pro-Nazi writer George Sylvester Viereck also insisted that Charteris had originated the story:The explanation was vouchsafed by General Charteris himself in , at a dinner at the National Arts Club, New York City. It met with diplomatic denial later on, but is generally accepted.Charteris's alleged 1925 comments later gave Adolf Hitler rhetorical ammunition to portray the British as liars who would invent imaginary war crimes. The widespread belief that the ' had been invented as propaganda had an adverse effect during

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

on rumours emerging about the Holocaust

The Holocaust (), known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as the (), was the genocide of History of the Jews in Europe, European Jews during World War II. From 1941 to 1945, Nazi Germany and Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy ...

. One of the earliest reports in September 1942, known as the "Sternbuch cable" stated that the Germans were "bestially murdering about one hundred thousand Jews" in Warsaw and that "from the corpses of the murdered, soap and artificial fertilizers are produced".Neander, Joachim, ''The German Corpse Factory. The Master Hoax of British Propaganda in the First World War'', Saarland University Press, 2013, pp.8-9. Victor Cavendish-Bentinck, chairman of the British Joint Intelligence Committee, noted that these reports were rather too similar to "stories of employment of human corpses during the last war for the manufacture of fat which was a grotesque lie." Likewise, '' The Christian Century'' commented that "The parallel between this story and the ‘corpse factory’ atrocity tale of the First World War is too striking to be overlooked.” German scholar Joachim Neander notes that "There can be no doubt that the reported commercial use of the corpses of the murdered Jews undermined the credibility of the news coming from Poland and delayed action that might have rescued many Jewish lives."

Recent scholarship

Modern scholarship supports the view that the story arose from rumours circulating among troops and civilians in Belgium, and was not an invention of the British propaganda machine. It moved from rumour to apparent "fact" after the report in the ' appeared about a real cadaver-processing factory. The ambiguous wording of the report allowed Belgian and British newspapers to interpret it as proof of the rumours that human corpses were used. Phillip Knightley says that Charteris may have concocted the claim that he invented the story in order to impress his audience, not realising a reporter was present. Randal Marlin says that Charteris's claim to have invented the story is "demonstrably false" in a number of details. However, it is possible that a fake diary was created but never used. Nevertheless, this diary, which Charteris claimed to still exist “in the war museum in London”, has never been found. It is also possible that Charteris suggested that the story would be useful propaganda in China, and that he created a miscaptioned photograph to be sent to the Chinese, but again there is no evidence of this. Adrian Gregory is highly critical of Lord Ponsonby's account in ''Falsehood in War-Time'', arguing that the story, like many other anti-German atrocity tales, originated with ordinary soldiers and members of the public: “the process was bottom-up more than top-down,” and that in most of the false atrocity stories “the public were misleading the press”, rather than a sinister press propaganda machine deceiving an innocent public. Joachim Neander says that the process was more like a "feedback loop" in which plausible stories were picked up and used by propagandists such as Charteris: "Charteris and his office most probably did not have a part in creating the 'Corpse factory' story. It can, however, be safely assumed that they were actively involved in its spreading." Furthermore, the story would have remained little more than rumour and tittle-tattle if it had not been taken up by respectable newspapers such as ''The Times'' in 1917.Neander, Joachim, ''The German Corpse Factory. The Master Hoax of British Propaganda in the First World War'', Saarland University Press, 2013, p.175. Israeli writer Shimon Rubinstein suggested in 1987 that it was possible that the story of the corpse factory was true, but that Charteris wished to discredit it in order to foster harmonious relations with post-war Germany after the 1925 Treaty of Locarno. Rubinstein posited that such factories were “possible pilot-plants for the extermination centers the Nazis built during World War II.” Joachim Neander has commented that the absence of any reliable evidence that the “Corpse factory” establishments actually existed, completely undermines Rubinstein’s claims.Similar claims in later conflicts

During the2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine

On 24 February 2022, , starting the largest and deadliest war in Europe since World War II, in a major escalation of the Russo-Ukrainian War, conflict between the two countries which began in 2014. The fighting has caused hundreds of thou ...

, a claim emerged in 2023 that the Russian military was concealing its losses with a similar method of packing human corpses into meat, often referred to as " wikt:mobik meat cubes". These claims were never able to be verified and have since been dismissed as another case of disinformation in the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

See also

*Anti-German sentiment

Anti-German sentiment (also known as anti-Germanism, Germanophobia or Teutophobia) is fear or dislike of Germany, its Germans, people, and its Culture of Germany, culture. Its opposite is Germanophile, Germanophilia.

Anti-German sentiment main ...

* Soap made from human corpses

* Lampshades made from human skin

Notes

{{Urban legends World War I propaganda Belgium in World War I Propaganda legends Propaganda in the United Kingdom Corpses Necroviolence