General Franco on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (; 4 December 1892 – 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general who led the Nationalist forces in overthrowing the

Francisco Franco Bahamonde was born on 4 December 1892 in the Calle Frutos Saavedra in

Francisco Franco Bahamonde was born on 4 December 1892 in the Calle Frutos Saavedra in

In 1913, Franco transferred into the newly formed regulares: Moroccan colonial troops with Spanish officers, who acted as elite

In 1913, Franco transferred into the newly formed regulares: Moroccan colonial troops with Spanish officers, who acted as elite

On 5 February 1932, Franco was given a command in

On 5 February 1932, Franco was given a command in

Following the ''

Following the ''

The designated leader of the uprising, General José Sanjurjo, died on 20 July 1936 in a plane crash. In the nationalist zone, "political life ceased". Initially, only military command mattered: this was divided into regional commands (

The designated leader of the uprising, General José Sanjurjo, died on 20 July 1936 in a plane crash. In the nationalist zone, "political life ceased". Initially, only military command mattered: this was divided into regional commands (

On 19 April 1937, Franco and Serrano Súñer, with the acquiescence of Generals Mola and Quiepo de Llano, forcibly merged the ideologically distinct national-syndicalist Falange and the

On 19 April 1937, Franco and Serrano Súñer, with the acquiescence of Generals Mola and Quiepo de Llano, forcibly merged the ideologically distinct national-syndicalist Falange and the

'' El Mundo'', 7 July 2002

on the website of the '' Cité nationale de l'histoire de l'immigration'' The Chilean poet

In September 1939, World War II began. Franco had received important support from

In September 1939, World War II began. Franco had received important support from  In the winter of 1940 and 1941, Franco toyed with the idea of a "Latin Bloc" formed by Spain, Portugal, Vichy France, the Vatican and Italy, without much consequence. Franco had cautiously decided to enter the war on the Axis side in June 1940, and to prepare his people for war, an anti-British and anti-French campaign was launched in the Spanish media that demanded

In the winter of 1940 and 1941, Franco toyed with the idea of a "Latin Bloc" formed by Spain, Portugal, Vichy France, the Vatican and Italy, without much consequence. Franco had cautiously decided to enter the war on the Axis side in June 1940, and to prepare his people for war, an anti-British and anti-French campaign was launched in the Spanish media that demanded

Franco was recognised as the Spanish head of state by the United Kingdom, France and Argentina in February 1939. Already proclaimed ''

Franco was recognised as the Spanish head of state by the United Kingdom, France and Argentina in February 1939. Already proclaimed ''

''Fascism: Past, Present, Future''

Oxford University Press. . p. 13 De Meneses, Filipe Ribeiro (2001

''Franco and the Spanish Civil War''

Routledge. p. 87. .Gilmour, David (1985

''The Transformation of Spain: From Franco to the Constitutional Monarchy''

Quartet Books. p. 7. . although Stanley Payne argued that very few scholars consider him to be a "core fascist". Regarding the regime, the ''Oxford Living Dictionary'' uses Franco's regime as an example of

By the start of the 1950s Franco's state had become less violent, but during his entire rule, non-government trade unions and all political opponents across the

By the start of the 1950s Franco's state had become less violent, but during his entire rule, non-government trade unions and all political opponents across the

Second Spanish Republic

The Spanish Republic (), commonly known as the Second Spanish Republic (), was the form of government in Spain from 1931 to 1939. The Republic was proclaimed on 14 April 1931, after the deposition of King Alfonso XIII, and was dissolved on 1 ...

during the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlism, Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebeli ...

and thereafter ruled over Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' ( Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

from 1939 to 1975 as a dictator

A dictator is a political leader who possesses absolute power. A dictatorship is a state ruled by one dictator or by a small clique. The word originated as the title of a Roman dictator elected by the Roman Senate to rule the republic in ti ...

, assuming the title '' Caudillo''. This period in Spanish history, from the Nationalist victory to Franco's death, is commonly known as Francoist Spain

Francoist Spain ( es, España franquista), or the Francoist dictatorship (), was the period of Spanish history between 1939 and 1975, when Francisco Franco ruled Spain after the Spanish Civil War with the title . After his death in 1975, Sp ...

or as the Francoist dictatorship.

Born in Ferrol Ferrol may refer to:

Places

* Ferrol (comarca), a coastal region in A Coruña, Galicia, Spain

* Ferrol, Spain, industrial city and naval station in Galicia, Spain

** Racing de Ferrol, an association football club

* Ferrol, Romblon, municipality in ...

, Galicia

Galicia may refer to:

Geographic regions

* Galicia (Spain), a region and autonomous community of northwestern Spain

** Gallaecia, a Roman province

** The post-Roman Kingdom of the Suebi, also called the Kingdom of Gallaecia

** The medieval King ...

, into an upper-class military family, Franco served in the Spanish Army

The Spanish Army ( es, Ejército de Tierra, lit=Land Army) is the terrestrial army of the Spanish Armed Forces responsible for land-based military operations. It is one of the oldest active armies — dating back to the late 15th century.

The ...

as a cadet

A cadet is an officer trainee or candidate. The term is frequently used to refer to those training to become an officer in the military, often a person who is a junior trainee. Its meaning may vary between countries which can include youths in ...

in the Toledo Infantry Academy from 1907 to 1910. While serving in Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria ...

, he rose through the ranks to become a brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed t ...

in 1926 at age 33, which made him the youngest general in all of Europe. Two years later, Franco became the director of the General Military Academy in Zaragoza. As a conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

and monarchist, Franco regretted the abolition of the monarchy

A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, is head of state for life or until abdication. The political legitimacy and authority of the monarch may vary from restricted and largely symbolic (constitutional monarchy ...

and the establishment of the Second Republic in 1931, and was devastated by the closing of his academy; nevertheless, he continued his service in the Republican Army. His career was boosted after the right-wing

Right-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that view certain social orders and hierarchies as inevitable, natural, normal, or desirable, typically supporting this position on the basis of natural law, economics, autho ...

CEDA and PRR won the 1933 election, empowering him to lead the suppression of the 1934 uprising in Asturias. Franco was briefly elevated to Chief of Army Staff

Chief of Army Staff or Chief of the Army Staff which is generally abbreviated as COAS is a title commonly used for the appointment held by the most senior staff officer or the chief commander in several nations' armies.

* Chief of Army (Australia ...

before the 1936 election moved the leftist

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in soc ...

Popular Front

A popular front is "any coalition of working-class and middle-class parties", including liberal and social democratic ones, "united for the defense of democratic forms" against "a presumed Fascist assault".

More generally, it is "a coalitio ...

into power, relegating him to the Canary Islands

The Canary Islands (; es, Canarias, ), also known informally as the Canaries, are a Spanish autonomous community and archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, in Macaronesia. At their closest point to the African mainland, they are west of Mo ...

. Initially reluctant, he joined the July 1936 military coup, which, after failing to take Spain, sparked the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlism, Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebeli ...

.

During the war, he commanded Spain's African colonial army and later, following the deaths of much of the rebel leadership, became his faction's only leader, being appointed Generalissimo

''Generalissimo'' ( ) is a military rank of the highest degree, superior to field marshal and other five-star ranks in the states where they are used.

Usage

The word (), an Italian term, is the absolute superlative of ('general') thus m ...

and head of state

A head of state (or chief of state) is the public persona who officially embodies a state (polity), state#Foakes, Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representatitve of its international p ...

in 1936. He consolidated all nationalist parties into the FET y de las JONS

The Falange Española Tradicionalista y de las Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional Sindicalista (FET y de las JONS; ), frequently shortened to just "FET", was the sole legal party of the Francoist regime in Spain. It was created by General Francisco F ...

(creating a one-party state

A one-party state, single-party state, one-party system, or single-party system is a type of sovereign state in which only one political party has the right to form the government, usually based on the existing constitution. All other parties ...

). Three years later the Nationalists declared victory, which extended Franco's dictatorship over Spain through a period of repression of political opponents. His dictatorship's use of forced labor

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, violence including death, or other forms of e ...

, concentration camps

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simpl ...

and executions led to between 30,000 and 50,000 deaths. Combined with wartime killings, this brings the death toll of the White Terror to between 100,000 and 200,000.

In post-civil war Spain, Franco developed a cult of personality

A cult of personality, or a cult of the leader, Mudde, Cas and Kaltwasser, Cristóbal Rovira (2017) ''Populism: A Very Short Introduction''. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 63. is the result of an effort which is made to create an id ...

around his rule by founding the ''Movimiento Nacional

''Movimiento Nacional'' ( en, National Movement) was a governing institution of Spain established by General Francisco Franco during the Spanish Civil War in 1937. During Francoist rule in Spain, it purported to be the only channel of participa ...

''. During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

he maintained Spanish neutrality, but supported the Axis—whose members Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

and Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG),, is a country in Central Europe. It is the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany lies between the Baltic and North Sea to the north and the Alps to the sou ...

had supported him during the Civil War— damaging the country's international reputation in various ways. During the start of the Cold War, Franco lifted Spain out of its mid-20th century economic depression through technocratic and economically liberal policies, presiding over a period of accelerated growth known as the " Spanish miracle". At the same time, his regime transitioned from a totalitarian

Totalitarianism is a form of government and a political system that prohibits all opposition parties, outlaws individual and group opposition to the state and its claims, and exercises an extremely high if not complete degree of control and regul ...

state to an authoritarian one with limited pluralism

Pluralism denotes a diversity of views or stands rather than a single approach or method.

Pluralism or pluralist may refer to:

Politics and law

* Pluralism (political philosophy), the acknowledgement of a diversity of political systems

* Plur ...

. He became a leader in the anti-Communist movement, garnering support from the West, particularly the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., federal district, five ma ...

. As the dictatorship relaxed its hard-line policies, Luis Carrero Blanco

Admiral general (Spain), Admiral-General Luis Carrero Blanco (4 March 1904 – 20 December 1973) was a Spanish Navy officer and politician. A long-time confidant and right-hand man of dictator Francisco Franco, Carrero served as the Prime ...

became Franco's '' éminence grise'', whose role expanded after Franco began struggling with Parkinson's disease

Parkinson's disease (PD), or simply Parkinson's, is a long-term degenerative disorder of the central nervous system that mainly affects the motor system. The symptoms usually emerge slowly, and as the disease worsens, non-motor symptoms becom ...

in the 1960s. In 1973, Franco resigned as prime minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

—separated from the office of head of state since 1967—due to his advanced age and illness. Nevertheless, he remained in power as the head of state and as commander-in-chief. Franco died in 1975, aged 82, and was entombed in the Valle de los Caídos. He restored the monarchy in his final years, being succeeded by Juan Carlos, King of Spain, who led the Spanish transition to democracy.

The legacy of Franco in Spanish history remains controversial, as the nature of his dictatorship changed over time. His reign was marked by both brutal repression, with tens of thousands killed, and economic prosperity, which greatly improved the quality of life in Spain. His dictatorial style proved adaptable enough to allow social and economic reform, but still centred on highly centralised government, authoritarianism, nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a in-group and out-group, group of peo ...

, national Catholicism, anti-freemasonry and anti-Communism

Anti-communism is political and ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, when the United States and ...

.

Early life

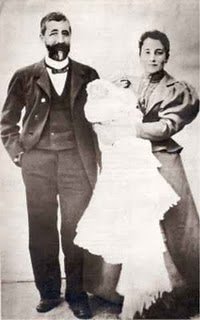

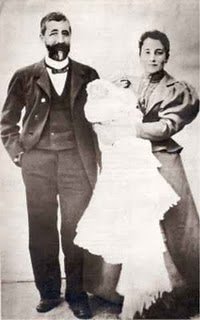

Francisco Franco Bahamonde was born on 4 December 1892 in the Calle Frutos Saavedra in

Francisco Franco Bahamonde was born on 4 December 1892 in the Calle Frutos Saavedra in El Ferrol

Ferrol () is a city in the Province of A Coruña in Galicia, on the Atlantic coast in north-western Spain, in the vicinity of Strabo's Cape Nerium (modern day Cape Prior). According to the 2021 census, the city has a population of 64,785, maki ...

, Galicia, into a seafaring family. He was baptised thirteen days later at the military church of San Francisco, with the baptismal name Francisco Paulino Hermenegildo Teódulo.

After relocating to Galicia

Galicia may refer to:

Geographic regions

* Galicia (Spain), a region and autonomous community of northwestern Spain

** Gallaecia, a Roman province

** The post-Roman Kingdom of the Suebi, also called the Kingdom of Gallaecia

** The medieval King ...

, the Franco family was involved in the Spanish Navy

The Spanish Navy or officially, the Armada, is the Navy, maritime branch of the Spanish Armed Forces and one of the oldest active naval forces in the world. The Spanish Navy was responsible for a number of major historic achievements in navigat ...

, and over the span of two centuries produced naval officers for six uninterrupted generations (including several admirals), down to Franco's father (22 November 1855 – 22 February 1942).

His mother, María del Pilar Bahamonde y Pardo de Andrade (15 October 1865 – 28 February 1934), was from an upper-middle-class Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

family. Her father, Ladislao Bahamonde Ortega, was the commissar

Commissar (or sometimes ''Kommissar'') is an English transliteration of the Russian (''komissar''), which means ' commissary'. In English, the transliteration ''commissar'' often refers specifically to the political commissars of Soviet and ...

of naval equipment at the Port of El Ferrol. Franco's parents married in 1890 in the Church of San Francisco in El Ferrol. The young Franco spent much of his childhood with his two brothers, Nicolás and Ramón, and his two sisters, María del Pilar and María de la Paz. His brother Nicolás was a naval officer

An officer is a person who has a position of authority in a hierarchical organization. The term derives from Old French ''oficier'' "officer, official" (early 14c., Modern French ''officier''), from Medieval Latin ''officiarius'' "an officer," ...

and diplomat who married María Isabel Pascual del Pobil. Ramón was an internationally known aviator and a Freemason, originally with leftist political leanings. He was also the second sibling to die, killed in an air accident on a military mission in 1938.

Franco's father was a naval officer who reached the rank of vice admiral (''intendente general''). When Franco was fourteen, his father moved to Madrid following a reassignment and ultimately abandoned his family, marrying another woman. While Franco did not suffer any great abuse by his father's hand, he would never overcome his antipathy for his father and largely ignored him for the rest of his life. Years after becoming dictator, under the pseudonym Jaime de Andrade, Franco wrote a brief novel called ''Raza'', whose protagonist is believed by Stanley Payne to represent the idealised man Franco wished his father had been. Conversely, Franco strongly identified with his mother (who always wore widow's black once she realised her husband had abandoned her) and learned from her moderation, austerity, self-control, family solidarity and respect for Catholicism, though he would also inherit his father's harshness, coldness and implacability.

Military career

Rif War and advancement through the ranks

Francisco followed his father into the Navy, but as a result of theSpanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (cl ...

the country lost much of its navy as well as most of its colonies. Not needing any more officers, the Naval Academy admitted no new entrants from 1906 to 1913. To his father's chagrin, Francisco decided to try the Spanish Army

The Spanish Army ( es, Ejército de Tierra, lit=Land Army) is the terrestrial army of the Spanish Armed Forces responsible for land-based military operations. It is one of the oldest active armies — dating back to the late 15th century.

The ...

. In 1907, he entered the Infantry Academy in Toledo

Toledo most commonly refers to:

* Toledo, Spain, a city in Spain

* Province of Toledo, Spain

* Toledo, Ohio, a city in the United States

Toledo may also refer to:

Places Belize

* Toledo District

* Toledo Settlement

Bolivia

* Toledo, Orur ...

. At the age of fourteen, Franco was one of the youngest members of his class, with most boys being between sixteen and eighteen. He was short and was bullied for his small size. His grades were average; though his good memory meant he seldom struggled academically, his small stature was a hindrance in physical tests. He graduated in July 1910 as a second lieutenant, standing 251st out of 312 cadets in his class, though this might have had less to do with his grades than with his small size and young age. Stanley Payne observes that by the time civil war began, Franco had already become a major general and would soon be a generalissimo, while none of his higher-ranking fellow cadets had managed to get beyond the rank of lieutenant-colonel. Franco was promoted to the rank of first lieutenant in June 1912 at age 19. Two years later, he obtained a commission to Morocco. Spanish efforts to occupy the new African protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over most of its inte ...

provoked the Second Melillan campaign in 1909 against native Moroccans, the first of several Riffian rebellions. Their tactics resulted in heavy losses among Spanish military officers

An officer is a person who holds a position of authority as a member of an armed force or uniformed service.

Broadly speaking, "officer" means a commissioned officer, a non-commissioned officer, or a warrant officer. However, absent conte ...

, and also provided an opportunity to earn promotion through merit on the battlefield. It was said that officers would receive either ''la caja o la faja'' (a coffin or a general's sash). Franco quickly gained a reputation as an effective officer.  In 1913, Franco transferred into the newly formed regulares: Moroccan colonial troops with Spanish officers, who acted as elite

In 1913, Franco transferred into the newly formed regulares: Moroccan colonial troops with Spanish officers, who acted as elite shock troops

Shock troops or assault troops are formations created to lead an attack. They are often better trained and equipped than other infantry, and expected to take heavy casualties even in successful operations.

"Shock troop" is a calque, a loose tran ...

. In 1916, aged 23 with the rank of captain, Franco was shot in the abdomen by guerilla gunfire during an assault on Moroccan positions at ''El Biutz'', in the hills near Ceuta; this was the only time he was wounded in ten years of fighting. The wound was serious, and he was not expected to live. His recovery was seen by his Moroccan troops as a spiritual event – they believed Franco to be blessed with ''baraka

Baraka or Barakah may refer to:

* Berakhah or Baraka, in Judaism, a blessing usually recited during a ceremony

* Barakah or Baraka, in Islam, the beneficent force from God that flows through the physical and spiritual spheres

* Baraka, full ''� ...

,'' or protected by God. He was recommended for promotion to major and to receive Spain's highest honour for gallantry, the coveted '' Cruz Laureada de San Fernando''. Both proposals were denied, with the 23-year-old Franco's young age being given as the reason for denial. Franco appealed the decision to the king, who reversed it. Franco also received the ''Cross of Maria Cristina, First Class''.

With that he was promoted to major at the end of February 1917 at age 24. This made him the youngest major in the Spanish army. From 1917 to 1920, he served in Spain. In 1920, Lieutenant Colonel José Millán Astray, a histrionic but charismatic officer, founded the Spanish Foreign Legion, along similar lines as the French Foreign Legion

The French Foreign Legion (french: Légion étrangère) is a corps of the French Army which comprises several specialties: infantry, cavalry, engineers, airborne troops. It was created in 1831 to allow foreign nationals into the French Army ...

. Franco became the Legion's second-in-command and returned to Africa. In the Rif War

The Rif War () was an armed conflict fought from 1921 to 1926 between Spain (joined by France in 1924) and the Berber tribes of the mountainous Rif region of northern Morocco.

Led by Abd el-Krim, the Riffians at first inflicted several d ...

, the poorly commanded and overextended Spanish Army was defeated by the Republic of the Rif under the leadership of the Abd el-Krim

Muhammad ibn Abd al-Karim al-Khattabi (; Tarifit: Muḥend n Ɛabd Krim Lxeṭṭabi, ⵎⵓⵃⵏⴷ ⵏ ⵄⴰⴱⴷⵍⴽⵔⵉⵎ ⴰⵅⵟⵟⴰⴱ), better known as Abd el-Krim (1882/1883, Ajdir, Morocco – 6 February 1963, Cairo, Egypt) ...

brothers, who crushed a Spanish offensive on 24 July 1921, at Annual. The Legion and supporting units relieved the Spanish city of Melilla

Melilla ( , ; ; rif, Mřič ; ar, مليلية ) is an autonomous city of Spain located in north Africa. It lies on the eastern side of the Cape Three Forks, bordering Morocco and facing the Mediterranean Sea. It has an area of . It was ...

after a three-day forced march led by Franco. In 1923, now a lieutenant colonel, he was made commander of the Legion.

On 22 October 1923, Franco married María del Carmen Polo y Martínez-Valdès (11 June 1900 – 6 February 1988). Following his honeymoon Franco was summoned to Madrid to be presented to King Alfonso XIII

Alfonso XIII (17 May 1886 – 28 February 1941), also known as El Africano or the African, was King of Spain from 17 May 1886 to 14 April 1931, when the Second Spanish Republic was proclaimed. He was a monarch from birth as his father, Al ...

. This and other occasions of royal attention would mark him during the Republic as a monarchical officer.

Disappointed with the plans for a strategic retreat from the interior to the African coastline by Primo de Rivera, Franco wrote in the April 1924 issue of ''Revista de Tropas Coloniales'' (''Colonial Troops Magazine'') that he would disobey orders of retreat given by a superior. He also held a tense meeting with Primo de Rivera in July 1924. According to fellow ''africanista'', Gonzalo Queipo de Llano, Franco visited him on 21 September 1924 to propose that he lead a coup d'état against Primo. In the end, Franco complied with Primo's orders, taking part in the in late 1924, and thus earning a promotion to colonel.

Franco led the first wave of troops ashore at Al Hoceima

Al Hoceima ( ber, translit=Lḥusima, label= Riffian-Berber, ⵍⵃⵓⵙⵉⵎⴰ; ar, الحسيمة; '' es, Alhucemas'') is a Riffian city in the north of Morocco, on the northern edge of the Rif Mountains and on the Mediterranean coast. I ...

(Spanish: ''Alhucemas'') in 1925. This landing in the heartland of Abd el-Krim's tribe, combined with the French invasion from the south, spelled the beginning of the end for the short-lived Republic of the Rif. Franco was eventually recognised for his leadership, and he was promoted to brigadier general on 3 February 1926, making him the youngest general in Europe at age 33, according to Payne and Palacios. On 14 September 1926, Franco and Polo had a daughter, María del Carmen

''María del Carmen'' is an opera in three acts composed by Enrique Granados to a Spanish libretto by José Feliú i Codina based on his 1896 play of the same name. It was Granados's first operatic success and, although it is largely forgotten tod ...

. Franco would have a close relationship with his daughter and was a proud parent, though his traditionalist attitudes and increasing responsibilities meant he left much of the child-rearing to his wife. In 1928 Franco was appointed director of the newly created General Military Academy of Zaragoza, a new college for all Spanish army cadet

A cadet is an officer trainee or candidate. The term is frequently used to refer to those training to become an officer in the military, often a person who is a junior trainee. Its meaning may vary between countries which can include youths in ...

s, replacing the former separate institutions for young men seeking to become officers in infantry, cavalry, artillery, and other branches of the army. Franco was removed as Director of the Zaragoza Military Academy in 1931; when the Civil War began, the colonels, majors, and captains of the Spanish Army who had attended the academy when he was its director displayed unconditional loyalty to him as Caudillo.

During the Second Spanish Republic

The municipal elections of 12 April 1931 were largely seen as a plebiscite on the monarchy. The Republican-Socialist alliance failed to win the majority of the municipalities in Spain, but had a landslide victory in all the large cities and in almost all the provincial capitals. The monarchists and the army deserted Alfonso XIII and consequently the king decided to leave the country and go into exile, giving way to theSecond Spanish Republic

The Spanish Republic (), commonly known as the Second Spanish Republic (), was the form of government in Spain from 1931 to 1939. The Republic was proclaimed on 14 April 1931, after the deposition of King Alfonso XIII, and was dissolved on 1 ...

. Although Franco believed that the majority of the Spanish people still supported the crown, and although he regretted the end of the monarchy, he did not object, nor did he challenge the legitimacy of the republic. The closing of the academy in June by the provisional War Minister Manuel Azaña however was a major setback for Franco and provoked his first clash with the Spanish Republic. Azaña found Franco's farewell speech to the cadets insulting. In his speech Franco stressed the Republic's need for discipline and respect. Azaña entered an official reprimand into Franco's personnel file and for six months Franco was without a post and under surveillance.

In December 1931, a new reformist, liberal, and democratic constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princip ...

was declared. It included strong provisions enforcing a broad secularisation

In sociology, secularization (or secularisation) is the transformation of a society from close identification with religious values and institutions toward non-religious values and secular institutions. The ''secularization thesis'' expresses t ...

of the Catholic country, which included the abolishing of Catholic schools and charities, which many moderate committed Catholics opposed. At this point, once the constituent assembly had fulfilled its mandate of approving a new constitution, it should have arranged for regular parliamentary elections and adjourned, according to historian Carlton J. H. Hayes. Fearing the increasing popular opposition, the Radical and Socialist majority postponed the regular elections, thereby prolonging their stay in power for two more years. This way the republican government of Manuel Azaña initiated numerous reforms to what in their view would "modernize" the country.

Franco was a subscriber to the journal of Acción Española, a monarchist organisation, and a firm believer in a supposed Jewish-Masonic-Bolshevik conspiracy, or ''contubernio'' (conspiracy). The conspiracy suggested that Jews, Freemasons, Communists, and other leftists alike sought the destruction of Christian Europe, with Spain being the principal target.

On 5 February 1932, Franco was given a command in

On 5 February 1932, Franco was given a command in A Coruña

A Coruña (; es, La Coruña ; historical English: Corunna or The Groyne) is a city and municipality of Galicia, Spain. A Coruña is the most populated city in Galicia and the second most populated municipality in the autonomous community and ...

. Franco avoided involvement in José Sanjurjo's attempted coup that year, and even wrote a hostile letter to Sanjurjo expressing his anger over the attempt. As a result of Azaña's military reform, in January 1933 Franco was relegated from first to 24th in the list of brigadiers. The same year, on 17 February he was given the military command of the Balearic Islands. The post was above his rank, but Franco was still unhappy that he was stuck in a position he disliked. The prime minister wrote in his diary that it was probably more prudent to have Franco away from Madrid.

In 1932, the Jesuits, who were in charge of many schools throughout the country, were banned and had all their property confiscated. The army was further reduced and landowners were expropriated. Home rule was granted to Catalonia, with a local parliament and a president of its own. In June 1933 Pope Pius XI

Pope Pius XI ( it, Pio XI), born Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti (; 31 May 1857 – 10 February 1939), was head of the Catholic Church from 6 February 1922 to his death in February 1939. He was the first sovereign of Vatican City fr ...

issued the encyclical Dilectissima Nobis (Our Dearly Beloved), "On Oppression of the Church of Spain", in which he criticised the anti-clericalism of the Republican government.

The elections held in October 1933 resulted in a centre-right majority. The political party with the most votes was the Confederación Español de Derechas Autónomas ("CEDA"), but president Alcalá-Zamora declined to invite the leader of the CEDA, Gil Robles, to form a government. Instead he invited the Radical Republican Party's Alejandro Lerroux to do so. Despite receiving the most votes, CEDA was denied cabinet positions for nearly a year. After a year of intense pressure, CEDA, the largest party in the congress, was finally successful in forcing the acceptance of three ministries. The entrance of CEDA in the government, despite being normal in a parliamentary democracy, was not well accepted by the left. The Socialists triggered an insurrection that they had been preparing for nine months. The leftist Republican parties did not directly join the insurrection, but their leadership issued statements that they were "breaking all relations" with the Republican government. The Catalan ''Bloc Obrer i Camperol'' (BOC) advocated the need to form a broad workers' front, and took the lead in forming a new and more encompassing ''Alianza Obrera'', which included the Catalan UGT and the Catalan sector of the PSOE, with the goal of defeating fascism and advancing the socialist revolution. The ''Alianza Obrera'' declared a general strike "against fascism" in Catalonia in 1934. A Catalan state was proclaimed by Catalan nationalist leader Lluis Companys, but it lasted just ten hours. Despite an attempt at a general stoppage in Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), an ...

, other strikes did not endure. This left the striking Asturian miners to fight alone.

In several mining towns in Asturias, local unions gathered small arms and were determined to see the strike through. It began on the evening of 4 October, with the miners occupying several towns, attacking and seizing local Civil

Civil may refer to:

*Civic virtue, or civility

*Civil action, or lawsuit

* Civil affairs

*Civil and political rights

*Civil disobedience

*Civil engineering

*Civil (journalism), a platform for independent journalism

*Civilian, someone not a membe ...

and Assault Guard barracks. Thirty four priests, six young seminarists with ages between 18 and 21, and several businessmen and civil guards were summarily executed by the revolutionaries in Mieres and Sama

Sama or SAMA may refer to:

Places

* Sama, Burkina Faso, a town in the Kouka Department, Banwa Province, Burkina Faso

* Sama, China (Sanya), a city in Hainan, China

* Sama, Chalus, a village in Mazandaran Province, Iran

* Sama, Nowshahr, a vil ...

, 58 religious buildings including churches, convents and part of the university at Oviedo were burned and destroyed, and over 100 priests were killed in the diocese. Franco, already General of Division and aide to the war minister, Diego Hidalgo, was put in command of the operations directed to suppress the violent insurgency. Troops of the Spanish Army of Africa carried this out, with General Eduardo López Ochoa as commander in the field. After two weeks of heavy fighting (and a death toll estimated between 1,200 and 2,000), the rebellion was suppressed.

The insurgency in Asturias in October 1934 sparked a new era of violent anti-Christian persecutions with the massacre of 34 priests, initiating the practice of atrocities against the clergy, and sharpened the antagonism between Left and Right. Franco and López Ochoa (who, prior to the campaign in Asturias, had been seen as a left-leaning officer) emerged as officers prepared to use "troops against Spanish civilians as if they were a foreign enemy". Franco described the rebellion to a journalist in Oviedo

Oviedo (; ast, Uviéu ) is the capital city of the Principality of Asturias in northern Spain and the administrative and commercial centre of the region. It is also the name of the municipality that contains the city. Oviedo is located ap ...

as, "a frontier war and its fronts are socialism, communism and whatever attacks civilisation to replace it with barbarism." Though the colonial units sent to the north by the government at Franco's recommendation consisted of the Spanish Foreign Legion and the Moroccan Regulares Indigenas, the right-wing press portrayed the Asturian rebels as lackeys of a foreign Jewish-Bolshevik conspiracy.

With this rebellion against legitimate established political authority, the socialists also repudiated the representative institutional system as the anarchists had done. The Spanish historian Salvador de Madariaga

Salvador de Madariaga y Rojo (23 July 1886 – 14 December 1978) was a Spanish diplomat, writer, historian, and pacifist. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature, and the Nobel Peace Prize. He was awarded the Charlemagne Prize in 19 ...

, an Azaña supporter, and an exiled vocal opponent of Francisco Franco is the author of a sharp critical reflection against the participation of the left in the revolt: "The uprising of 1934 is unforgivable. The argument that Mr Gil Robles tried to destroy the Constitution to establish fascism was, at once, hypocritical and false. With the rebellion of 1934, the Spanish left lost even the shadow of moral authority to condemn the rebellion of 1936."

At the start of the Civil War, López Ochoa was assassinated; his head was severed and paraded around the streets on a pole, with a card reading, 'This is the butcher of Asturias'. Some time after these events, Franco was briefly commander-in-chief of the Army of Africa (from 15 February onwards), and from 19 May 1935, on, Chief of the General Staff

Staff may refer to:

Pole

* Staff, a weapon used in stick-fighting

** Quarterstaff, a European pole weapon

* Staff of office, a pole that indicates a position

* Staff (railway signalling), a token authorizing a locomotive driver to use a particula ...

.

1936 general election

At the end of 1935, President Alcalá-Zamora manipulated a petty-corruption issue into a major scandal in parliament, and eliminated Alejandro Lerroux, the head of the Radical Republican Party, from the premiership. Subsequently, Alcalá-Zamora vetoed the logical replacement, a majority center-right coalition, led by the CEDA, which would reflect the composition of the parliament. He then arbitrarily appointed an interim prime minister and after a short period announced the dissolution of parliament and new elections. Two wide coalitions formed: thePopular Front

A popular front is "any coalition of working-class and middle-class parties", including liberal and social democratic ones, "united for the defense of democratic forms" against "a presumed Fascist assault".

More generally, it is "a coalitio ...

on the left, ranging from Republican Union to Communists

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a ...

, and the Frente Nacional on the right, ranging from the centre radicals

Radical may refer to:

Politics and ideology Politics

*Radical politics, the political intent of fundamental societal change

*Radicalism (historical), the Radical Movement that began in late 18th century Britain and spread to continental Europe and ...

to the conservative Carlists

Carlism ( eu, Karlismo; ca, Carlisme; ; ) is a Traditionalist and Legitimist political movement in Spain aimed at establishing an alternative branch of the Bourbon dynasty – one descended from Don Carlos, Count of Molina (1788–1855) – ...

. On 16 February 1936 the elections ended in a virtual draw, but in the evening leftist mobs started to interfere in the balloting and in the registration of votes, distorting the results. Stanley G. Payne

Stanley George Payne (born September 9, 1934) is an American historian of modern Spain and European Fascism at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. He retired from full-time teaching in 2004 and is currently Professor Emeritus at its Department ...

claims that the process was blatant electoral fraud, with widespread violation of the laws and the constitution. In line with Payne's point of view, in 2017 two Spanish scholars, Manuel Álvarez Tardío and Roberto Villa García published the result of a major research work in which they concluded that the 1936 elections were rigged, a view disputed by Paul Preston, and other scholars such as Iker Itoiz Ciáurriz, who denounces their conclusions as revisionist "classic Francoist anti-republican tropes".

On 19 February, the cabinet presided over by Portela Valladares

Manuel Portela y Valladares (Pontevedra, 31 January 1867 – Bandol, Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur, France 29 April 1952) was a Spanish political figure during the Second Spanish Republic. He served as the 43rd Attorney General of Spain betwe ...

resigned, with a new cabinet being quickly set up, composed chiefly of members of the Republican Left and the Republican Union and presided over by Manuel Azaña.

José Calvo Sotelo, who made anti-communism the focus of his parliamentary speeches, began spreading violent propaganda—advocating for a military coup d'état; formulating a catastrophist discourse of a dichotomous choice between "communism" or a markedly totalitarian "National" State, and setting the mood of the masses for a military rebellion. The diffusion of the myth about an alleged Communist coup d'état as well a pretended state of "social chaos" became pretexts for a coup. Franco himself along with General Emilio Mola

Emilio Mola y Vidal, 1st Duke of Mola, Grandee of Spain (9 July 1887 – 3 June 1937) was one of the three leaders of the Nationalist coup of July 1936, which started the Spanish Civil War.

After the death of Sanjurjo on 20 July 1936, M ...

had stirred an anti-Communist campaign in Morocco.

At the same time PSOE's left-wing socialists became more radical. Julio Álvarez del Vayo talked about "Spain's being converted into a socialist Republic in association with the Soviet Union". Francisco Largo Caballero declared that "the organized proletariat will carry everything before it and destroy everything until we reach our goal". The country rapidly descended into anarchy. Even the staunch socialist Indalecio Prieto, at a party rally in Cuenca in May 1936, complained: "We Spaniards have never seen so tragic a panorama or so great a collapse as in Spain at this moment. Abroad, Spain is classified as insolvent. This is not the road to socialism or communism but to desperate anarchism without even the advantage of liberty."

On 23 February, Franco was sent to the Canary Islands

The Canary Islands (; es, Canarias, ), also known informally as the Canaries, are a Spanish autonomous community and archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, in Macaronesia. At their closest point to the African mainland, they are west of Mo ...

to serve as the islands' military commander, an appointment perceived by him as a ''destierro'' (banishment). Meanwhile, a conspiracy led by General Mola was taking shape.

Interested in the parliamentary immunity granted by a seat at the Cortes, Franco intended to stand as candidate of the Right Bloc alongside José Antonio Primo de Rivera

José Antonio Primo de Rivera y Sáenz de Heredia, 1st Duke of Primo de Rivera, 3rd Marquess of Estella (24 April 1903 – 20 November 1936), often referred to simply as José Antonio, was a Spanish politician who founded the falangist Falang ...

for the by-election in the province of Cuenca

Cuenca is one of the five provinces of the autonomous community of Castilla-La Mancha. It is located in the eastern part of this autonomous community and covers 17,141 square km. It has a population of 203,841 inhabitants -- the least populated of ...

programmed for 3 May 1936, after the results of the February 1936 election were annulled in the constituency. But Primo de Rivera refused to run alongside a military officer (Franco in particular) and Franco himself ultimately desisted on 26 April, one day before the decision of the election authority. By that time, PSOE politician Indalecio Prieto had already deemed Franco as a "possible caudillo for a military uprising".

Disenchantment with Azaña's rule continued to grow and was dramatically voiced by Miguel de Unamuno

Miguel de Unamuno y Jugo (29 September 1864 – 31 December 1936) was a Spanish essayist, novelist, poet, playwright, philosopher, professor of Greek and Classics, and later rector at the University of Salamanca.

His major philosophical essay w ...

, a republican and one of Spain's most respected intellectuals, who in June 1936 told a reporter who published his statement in El Adelanto that President Manuel Azaña should "...debiera suicidarse como acto patriótico" ("commit suicide as a patriotic act").

In June 1936, Franco was contacted and a secret meeting was held within La Esperanza forest on Tenerife

Tenerife (; ; formerly spelled ''Teneriffe'') is the largest and most populous island of the Canary Islands. It is home to 43% of the total population of the Archipelago, archipelago. With a land area of and a population of 978,100 inhabitant ...

to discuss starting a military coup. An obelisk (which has subsequently been removed) commemorating this historic meeting was erected at the site in a clearing at Las Raíces in Tenerife.

Outwardly, Franco maintained an ambiguous attitude until nearly July. On 23 June 1936, he wrote to the head of the government, Casares Quiroga

Santiago Casares y Quiroga (8 May 1884, in A Coruña, Galicia – 17 February 1950, in Paris) was Prime Minister of Spain from 13 May to 19 July 1936.

Biography

Leader and founder of the Autonomous Galician Republican Organization (ORGA), a Ga ...

, offering to quell the discontent in the Spanish Republican Army

The Spanish Republican Army ( es, Ejército de la República Española) was the main branch of the Armed Forces of the Second Spanish Republic between 1931 and 1939.

It became known as People's Army of the Republic (''Ejército Popular de la Rep ...

, but received no reply. The other rebels were determined to go ahead ''con Paquito o sin Paquito'' (with ''Paquito'' or without ''Paquito''; ''Paquito'' being a diminutive of ''Paco'', which in turn is short for ''Francisco''), as it was put by José Sanjurjo, the honorary leader of the military uprising. After various postponements, 18 July was fixed as the date of the uprising. The situation reached a point of no return and, as presented to Franco by Mola, the coup was unavoidable and he had to choose a side. He decided to join the rebels and was given the task of commanding the Army of Africa. A privately owned DH 89 De Havilland Dragon Rapide, flown by two British pilots, Cecil Bebb and Hugh Pollard, was chartered in England on 11 July to take Franco to Africa.

The coup underway was precipitated by the assassination of the right-wing opposition leader Calvo Sotelo in retaliation for the murder of assault guard José Castillo, which had been committed by a group headed by a civil guard

Civil Guard refers to various policing organisations:

Current

* Civil Guard (Spain), Spanish gendarmerie

* Civil Guard (Israel), Israeli volunteer police reserve

* Civil Guard (Brazil), Municipal law enforcement corporations in Brazil

Histori ...

and composed of assault guards

The Cuerpo de Seguridad y Asalto ( en, Security and Assault Corps) was the heavy reserve force of the blue-uniformed urban police force of Spain during the Spanish Second Republic. The Assault Guards were special police and paramilitary units c ...

and members of the socialist militias. On 17 July, one day earlier than planned, the Army of Africa rebelled, detaining their commanders. On 18 July, Franco published a manifesto and left for Africa, where he arrived the next day to take command.

A week later the rebels, who soon called themselves the ''Nationalists'', controlled a third of Spain; most naval units remained under control of the Republican loyalist forces, which left Franco isolated. The coup had failed in the attempt to bring a swift victory, but the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlism, Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebeli ...

had begun.

From the Spanish Civil War to World War II

Franco rose to power during the Spanish Civil War, which began in July 1936 and officially ended with the victory of his Nationalist forces in April 1939. Although it is impossible to calculate precise statistics concerning the Spanish Civil War and its aftermath, Payne writes that if civilian fatalities above the norm are added to the total number of deaths for victims of violence, the number of deaths attributable to the civil war would reach approximately 344,000. During the war,rape

Rape is a type of sexual assault usually involving sexual intercourse or other forms of sexual penetration carried out against a person without their consent. The act may be carried out by physical force, coercion, abuse of authority, or ...

, torture

Torture is the deliberate infliction of severe pain or suffering on a person for reasons such as punishment, extracting a confession, interrogation for information, or intimidating third parties. Some definitions are restricted to acts ...

and summary execution

A summary execution is an execution in which a person is accused of a crime and immediately killed without the benefit of a Right to a fair trial, full and fair trial. Executions as the result of summary offense, summary justice (such as a drumhea ...

s committed by soldiers under Franco's command were used as a means of retaliation and to repress political dissent.

The war was marked by foreign intervention on behalf of both sides. Franco's Nationalists were supported by Fascist Italy

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy and the ...

, which sent the ''Corpo Truppe Volontarie

The Corps of Volunteer Troops ( it, Corpo Truppe Volontarie, CTV) was a Fascist Italian expeditionary force of military volunteers, which was sent to Spain to support the Nationalist forces under General Francisco Franco against the Spanish ...

'' and by Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

, which sent the Condor Legion

The Condor Legion (german: Legion Condor) was a unit composed of military personnel from the air force and army of Nazi Germany, which served with the Nationalist faction during the Spanish Civil War of July 1936 to March 1939. The Condor Le ...

. Italian aircraft stationed on Majorca

Mallorca, or Majorca, is the largest island in the Balearic Islands, which are part of Spain and located in the Mediterranean.

The capital of the island, Palma, is also the capital of the autonomous community of the Balearic Islands. The Bale ...

bombed Barcelona 13 times, dropping 44 tons of bombs aimed at civilians. These attacks were requested by General Franco as retribution against the Catalan population. Similarly, both Italian and German planes bombed the Basque town of Guernica at Franco's request. The Republican opposition was supported by communists, socialists, and anarchists within Spain as well as the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

and volunteers who fought in the International Brigades

The International Brigades ( es, Brigadas Internacionales) were military units set up by the Communist International to assist the Popular Front government of the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War. The organization existed ...

.

The first months

Following the ''

Following the ''pronunciamiento

A ''pronunciamiento'' (, pt, pronunciamento ; "proclamation , announcement or declaration") is a form of military rebellion or ''coup d'état'' particularly associated with Spain, Portugal and Latin America, especially in the 19th century.

Typol ...

'' of 18 July 1936, Franco assumed the leadership of the 30,000 soldiers of the Spanish Army of Africa. The first days of the insurgency were marked by an imperative need to secure control over the Spanish Moroccan Protectorate. On one side, Franco had to win the support of the native Moroccan population and their (nominal) authorities, and, on the other, he had to ensure his control over the army. His method was the summary execution of some 200 senior officers loyal to the Republic (one of them his own cousin). His loyal bodyguard was shot by Manuel Blanco. Franco's first problem was how to move his troops to the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, defi ...

, since most units of the Navy had remained in control of the Republic and were blocking the Strait of Gibraltar

The Strait of Gibraltar ( ar, مضيق جبل طارق, Maḍīq Jabal Ṭāriq; es, Estrecho de Gibraltar, Archaism, Archaic: Pillars of Hercules), also known as the Straits of Gibraltar, is a narrow strait that connects the Atlantic Ocean to ...

. He requested help from Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in ...

, who responded with an offer of arms and planes. In Germany Wilhelm Canaris

Wilhelm Franz Canaris (1 January 1887 – 9 April 1945) was a German admiral and the chief of the ''Abwehr'' (the German military-intelligence service) from 1935 to 1944. Canaris was initially a supporter of Adolf Hitler, and the Nazi re ...

, the head of the ''Abwehr

The ''Abwehr'' ( German for ''resistance'' or ''defence'', but the word usually means ''counterintelligence'' in a military context; ) was the German military-intelligence service for the '' Reichswehr'' and the ''Wehrmacht'' from 1920 to 1944. ...

'' military intelligence service, persuaded Hitler to support the Nationalists; Hitler sent twenty Ju 52 transport aircraft and six Heinkel

Heinkel Flugzeugwerke () was a German aircraft manufacturing company founded by and named after Ernst Heinkel. It is noted for producing bomber aircraft for the Luftwaffe in World War II and for important contributions to high-speed flight, with ...

biplane fighters, on the condition that they were not to be used in hostilities unless the Republicans attacked first. Mussolini sent 12 Savoia-Marchetti SM.81 transport/bombers, and a few fighter aircraft. From 20 July onward Franco was able, with this small squadron of aircraft, to initiate an air bridge

''Air Bridge'' is a 1951 thriller novel by the British writer Hammond Innes.

It is set during the Berlin Airlift, and features a former RAF pilot now on the run from the police after becoming involved in shady activities after the war. Like all of ...

that carried 1,500 soldiers of the Army of Africa to Seville

Seville (; es, Sevilla, ) is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsul ...

, where these troops helped to ensure rebel control of the city. Through representatives, he started to negotiate with the United Kingdom, Germany, and Italy for more military support, and above all for more aircraft. Negotiations were successful with the Germany and Italy on 25 July and aircraft began to arrive in Tetouan on 2 August. On 5 August Franco was able to break the blockade with the newly arrived air support, successfully deploying a convoy of fishing boats and merchant ships carrying some 3,000 soldiers; between 29 July and 15 August about 15,000 more men were moved.

On 26 July, just eight days after the revolt had started, foreign allies of the Republican government convened an international communist conference at Prague to arrange plans to help the Popular Front forces in Spain. It decided to raise an international brigade of 5,000 men and a fund of 1 billion francs to be administered by a committee of five in which Largo Caballero and Dolores Ibárruri ("la Pasionaria") had prominent roles. At the same time communist parties throughout the world quickly launched a full scale propaganda campaign in support of the Popular Front. The Communist International

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to "struggle by ...

(Comintern) immediately reinforced its activity, sending to Spain its Secretary-General, the Bulgarian Georgi Dimitrov

Georgi Dimitrov Mihaylov (; bg, Гео̀рги Димитро̀в Миха̀йлов), also known as Georgiy Mihaylovich Dimitrov (russian: Гео́ргий Миха́йлович Дими́тров; 18 June 1882 – 2 July 1949), was a Bulgarian ...

, and Palmiro Togliatti

Palmiro Michele Nicola Togliatti (; 26 March 1893 – 21 August 1964) was an Italian politician and leader of the Italian Communist Party from 1927 until his death. He was nicknamed ("The Best") by his supporters. In 1930 he became a citizen of ...

the chief of the Communist Party of Italy. From August onward, aid from the Soviet Union began; by February 1937 two ships per day arrived at Spain's Mediterranean ports carrying munitions, rifles, machine guns, hand grenades, artillery, and trucks. With the cargo came Soviet agents, technicians, instructors and propagandists.

The Communist International

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to "struggle by ...

immediately started to organize the International Brigades

The International Brigades ( es, Brigadas Internacionales) were military units set up by the Communist International to assist the Popular Front government of the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War. The organization existed ...

, volunteer military units which included the Garibaldi Brigade from Italy and the Lincoln Battalion from the United States. The International Brigades were usually deployed as shock troops

Shock troops or assault troops are formations created to lead an attack. They are often better trained and equipped than other infantry, and expected to take heavy casualties even in successful operations.

"Shock troop" is a calque, a loose tran ...

, and as a result they suffered high casualties.

In early August, the situation in western Andalucia

Andalusia (, ; es, Andalucía ) is the southernmost autonomous community in Peninsular Spain. It is the most populous and the second-largest autonomous community in the country. It is officially recognised as a "historical nationality". The t ...

was stable enough to allow Franco to organise a column (some 15,000 men at its height), under the command of then Lieutenant-Colonel Juan Yagüe

Juan Yagüe y Blanco, 1st Marquis of San Leonardo de Yagüe (19 November 1891 – 21 October 1952) was a Spanish military officer during the Spanish Civil War, one of the most important in the Nationalist side. He became known as the "Butcher of ...

, which would march through Extremadura

Extremadura (; ext, Estremaúra; pt, Estremadura; Fala: ''Extremaúra'') is an autonomous community of Spain. Its capital city is Mérida, and its largest city is Badajoz. Located in the central-western part of the Iberian Peninsula, ...

towards Madrid. On 11 August Mérida was taken, and on 15 August Badajoz

Badajoz (; formerly written ''Badajos'' in English) is the capital of the Province of Badajoz in the autonomous community of Extremadura, Spain. It is situated close to the Portuguese border, on the left bank of the river Guadiana. The populatio ...

, thus joining both nationalist-controlled areas. Additionally, Mussolini ordered a voluntary army, the ''Corpo Truppe Volontarie

The Corps of Volunteer Troops ( it, Corpo Truppe Volontarie, CTV) was a Fascist Italian expeditionary force of military volunteers, which was sent to Spain to support the Nationalist forces under General Francisco Franco against the Spanish ...

'' (CTV) of fully motorised units (some 12,000 Italians), to Seville, and Hitler added to them a professional squadron from the Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German '' Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the '' Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabt ...

(2JG/88) with about 24 planes. All these planes had the Nationalist Spanish insignia painted on them, but were flown by Italian and German nationals. The backbone of Franco's air force in those days was the Italian SM.79 and SM.81 bombers, the biplane Fiat CR.32 fighter and the German Junkers Ju 52

The Junkers Ju 52/3m (nicknamed ''Tante Ju'' ("Aunt Ju") and ''Iron Annie'') is a transport aircraft that was designed and manufactured by German aviation company Junkers.

Development of the Ju 52 commenced during 1930, headed by German aeron ...

cargo-bomber and the Heinkel He 51

The Heinkel He 51 was a German single-seat biplane which was produced in a number of different versions. It was initially developed as a fighter; a seaplane variant and a ground-attack version were also developed. It was a development of th ...

biplane fighter.

On 21 September, with the head of the column at the town of Maqueda (some 80 km away from Madrid), Franco ordered a detour to free the besieged garrison at the Alcázar of Toledo

Toledo most commonly refers to:

* Toledo, Spain, a city in Spain

* Province of Toledo, Spain

* Toledo, Ohio, a city in the United States

Toledo may also refer to:

Places Belize

* Toledo District

* Toledo Settlement

Bolivia

* Toledo, Orur ...

, which was achieved on 27 September. This controversial decision gave the Popular Front

A popular front is "any coalition of working-class and middle-class parties", including liberal and social democratic ones, "united for the defense of democratic forms" against "a presumed Fascist assault".

More generally, it is "a coalitio ...

time to strengthen its defenses in Madrid and hold the city that year, but with Soviet support. Kennan alleges that once Stalin had decided to assist the Spanish Republicans, the operation was put in place with remarkable speed and energy. The first load of arms and tanks arrived as early as 26 September and was secretly unloaded at night. Advisers accompanied the armaments. Soviet officers were in effective charge of military operations on the Madrid front. Kennan believes that this operation was originally conducted in good faith with no other purpose than saving the Republic.

Hitler's policy for Spain was shrewd and pragmatic. The minutes of a conference with his foreign minister and army chiefs at the Reich Chancellery

The Reich Chancellery (german: Reichskanzlei) was the traditional name of the office of the Chancellor of Germany (then called ''Reichskanzler'') in the period of the German Reich from 1878 to 1945. The Chancellery's seat, selected and prepared s ...

in Berlin on 10 November 1937 summarised his views on foreign policy regarding the Spanish Civil War: "On the other hand, a 100 percent victory for Franco was not desirable either, from the German point of view; rather were we interested in a continuance of the war and in the keeping up of the tension in the Mediterranean." Hitler distrusted Franco; according to the comments he made at the conference he wanted the war to continue, but he did not want Franco to achieve total victory. He felt that with Franco in undisputed control of Spain, the possibility of Italy intervening further or of its continuing to occupy the Balearic Islands would be prevented.

By February 1937 the Soviet Union's military help started to taper off, to be replaced by limited economic aid.

Rise to power

The designated leader of the uprising, General José Sanjurjo, died on 20 July 1936 in a plane crash. In the nationalist zone, "political life ceased". Initially, only military command mattered: this was divided into regional commands (

The designated leader of the uprising, General José Sanjurjo, died on 20 July 1936 in a plane crash. In the nationalist zone, "political life ceased". Initially, only military command mattered: this was divided into regional commands (Emilio Mola

Emilio Mola y Vidal, 1st Duke of Mola, Grandee of Spain (9 July 1887 – 3 June 1937) was one of the three leaders of the Nationalist coup of July 1936, which started the Spanish Civil War.

After the death of Sanjurjo on 20 July 1936, M ...

in the North, Gonzalo Queipo de Llano in Seville

Seville (; es, Sevilla, ) is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsul ...

commanding Andalucia

Andalusia (, ; es, Andalucía ) is the southernmost autonomous community in Peninsular Spain. It is the most populous and the second-largest autonomous community in the country. It is officially recognised as a "historical nationality". The t ...

, Franco with an independent command, and Miguel Cabanellas

Miguel Cabanellas Ferrer (1 January 1872 – 14 May 1938) was a Spanish Army officer. He was a leading figure of the 1936 coup d'état in Zaragoza and sided with the Nationalist faction during the Spanish Civil War.

Biography

Born on 1 Jan ...

in Zaragoza

Zaragoza, also known in English as Saragossa,''Encyclopædia Britannica'"Zaragoza (conventional Saragossa)" is the capital city of the Zaragoza Province and of the autonomous community of Aragon, Spain. It lies by the Ebro river and its tribut ...

commanding Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and an, Aragón ; ca, Aragó ) is an autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces (from north to so ...

). The Spanish Army of Morocco was itself split into two columns, one commanded by General Juan Yagüe

Juan Yagüe y Blanco, 1st Marquis of San Leonardo de Yagüe (19 November 1891 – 21 October 1952) was a Spanish military officer during the Spanish Civil War, one of the most important in the Nationalist side. He became known as the "Butcher of ...

and the other commanded by Colonel José Varela.

From 24 July a coordinating ''junta

Junta may refer to:

Government and military

* Junta (governing body) (from Spanish), the name of various historical and current governments and governing institutions, including civil ones

** Military junta, one form of junta, government led by ...

'', the National Defence Junta, was established, based at Burgos

Burgos () is a city in Spain located in the autonomous community of Castile and León. It is the capital and most populated municipality of the province of Burgos.

Burgos is situated in the north of the Iberian Peninsula, on the confluence o ...

. Nominally led by Cabanellas, as the most senior general, it initially included Mola, three other generals, and two colonels; Franco was later added in early August. On 21 September it was decided that Franco was to be commander-in-chief (this unified command was opposed only by Cabanellas), and, after some discussion, with no more than a lukewarm agreement from Queipo de Llano and from Mola, also head of government. He was, doubtlessly, helped to this primacy by the fact that, in late July, Hitler had decided that all of Germany's aid to the Nationalists would go to Franco.

Mola had been somewhat discredited as the main planner of the attempted coup that had now degenerated into a civil war, and was strongly identified with the Carlist

Carlism ( eu, Karlismo; ca, Carlisme; ; ) is a Traditionalist and Legitimist political movement in Spain aimed at establishing an alternative branch of the Bourbon dynasty – one descended from Don Carlos, Count of Molina (1788–1855) – o ...

monarchists and not at all with the Falange, a party with Fascist leanings and connections ("phalanx", a far-right Spanish political party founded by José Antonio Primo de Rivera

José Antonio Primo de Rivera y Sáenz de Heredia, 1st Duke of Primo de Rivera, 3rd Marquess of Estella (24 April 1903 – 20 November 1936), often referred to simply as José Antonio, was a Spanish politician who founded the falangist Falang ...

), nor did he have good relations with Germany. Queipo de Llano and Cabanellas had both previously rebelled against the dictatorship of General Miguel Primo de Rivera

Miguel Primo de Rivera y Orbaneja, 2nd Marquess of Estella (8 January 1870 – 16 March 1930), was a dictator, aristocrat, and military officer who served as Prime Minister of Spain from 1923 to 1930 during Spain's Restoration era. He deep ...

and were therefore discredited in some nationalist circles, and Falangist leader José Antonio Primo de Rivera was in prison in Alicante

Alicante ( ca-valencia, Alacant) is a city and municipality in the Valencian Community, Spain. It is the capital of the province of Alicante and a historic Mediterranean port. The population of the city was 337,482 , the second-largest in th ...

(he would be executed a few months later). The desire to keep a place open for him prevented any other Falangist leader from emerging as a possible head of state. Franco's previous aloofness from politics meant that he had few active enemies in any of the factions that needed to be placated, and he had also cooperated in recent months with both Germany and Italy.

On 1 October 1936, in Burgos

Burgos () is a city in Spain located in the autonomous community of Castile and León. It is the capital and most populated municipality of the province of Burgos.

Burgos is situated in the north of the Iberian Peninsula, on the confluence o ...

, Franco was publicly proclaimed as ''Generalísimo

''Generalissimo'' ( ) is a military rank of the highest degree, superior to field marshal and other five-star ranks in the states where they are used.

Usage

The word (), an Italian term, is the absolute superlative of ('general') thus me ...

'' of the National army and ''Jefe del Estado'' (Head of State

A head of state (or chief of state) is the public persona who officially embodies a state (polity), state#Foakes, Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representatitve of its international p ...

). When Mola was killed in another air accident a year later on 2 June 1937 (which some believe was an assassination), no military leader was left from those who had organised the conspiracy against the Republic between 1933 and 1935.

Military command

Franco personally guided military operations from this time until the end of the war. Franco himself was not a strategic genius, but he was very effective at organisation, administration, logistics and diplomacy. After the failed assault on Madrid in November 1936, Franco settled on a piecemeal approach to winning the war, rather than bold maneuvering. As with his decision to relieve the garrison at Toledo, this approach has been subject of some debate: some of his decisions, such as in June 1938 when he preferred to advance towardsValencia

Valencia ( va, València) is the capital of the autonomous community of Valencia and the third-most populated municipality in Spain, with 791,413 inhabitants. It is also the capital of the province of the same name. The wider urban area al ...

instead of Catalonia

Catalonia (; ca, Catalunya ; Aranese Occitan: ''Catalonha'' ; es, Cataluña ) is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a '' nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy.

Most of the territory (except the Val d'Aran) lies on the no ...

, remain particularly controversial from a military strategic viewpoint. Valencia, Castellon and Alicante saw the last Republican troops defeated by Franco.

Although both Germany and Italy provided military support to Franco, the degree of influence of both powers on his direction of the war seems to have been very limited. Nevertheless, the Italian troops, despite not always being effective, were present in most of the large operations in large numbers. Germany sent insignificant numbers of combat personnel to Spain, but aided the Nationalists with technical instructors and modern matériel; including some 200 tanks and 600 aircraft which helped the Nationalist air force dominate the skies for most of the war.

Franco's direction of the German and Italian forces was limited, particularly in the direction of the Condor Legion

The Condor Legion (german: Legion Condor) was a unit composed of military personnel from the air force and army of Nazi Germany, which served with the Nationalist faction during the Spanish Civil War of July 1936 to March 1939. The Condor Le ...

, but he was by default their supreme commander, and they declined to interfere in the politics of the Nationalist zone. For reasons of prestige it was decided to continue assisting Franco until the end of the war, and Italian and German troops paraded on the day of the final victory in Madrid.