French Feminists on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Feminism in France is the history of

Some women organized a feminist movement during the Commune, following up on earlier attempts in 1789 and 1848. Nathalie Lemel, a socialist bookbinder, and

Some women organized a feminist movement during the Commune, following up on earlier attempts in 1789 and 1848. Nathalie Lemel, a socialist bookbinder, and

On les disait 'pÃĐtroleuses'...

''" On the other hand, Paule Minck opened a free school in the Church of Saint Pierre de Montmartre, and animated the Club Saint-Sulpice on the Left Bank. The Russian

In 1909, French noblewoman and feminist Jeanne-Elizabeth Schmahl founded the

In 1909, French noblewoman and feminist Jeanne-Elizabeth Schmahl founded the

Les premiÃĻres femmes au Gouvernement (France, 1936-1981)

'' Histoire@Politique'', n°1, MayâJune 2007 The ''suffragettes'', however, did honour the achievements of foreign women in power by bringing attention to legislation passed under their influence concerning alcohol (such as

"Le Manifeste des 343 Salopes"

(in English " Manifesto of the 343 Sluts" or alternately "Manifesto of the 343 Bitches"), written by

Bilan d'un fÃĐminisme d'Ãtat

in ''Plein Droit'' n°75, December 2007 Elsa Dorlin,Elsa Dorlin (professor of philosophy at the Sorbonne, member of NextGenderation)

"Pas en notre nom !" â Contre la rÃĐcupÃĐration raciste du fÃĐminisme par la droite française

(Not in our names! Against the Racist Recuperation of Feminism by the French Right), ''L'Autre Campagne''

Uprising in the "banlieues"

Conference at the University of Chicago, 10 May 2006 (published in French in ''Lignes'', November 2006) Houria Bouteldja,Houria Bouteldja

De la cÃĐrÃĐmonie du dÃĐvoilement à Alger (1958) à Ni Putes Ni Soumises: l'instrumentalisation coloniale et nÃĐo-coloniale de la cause des femmes., Ni putes ni soumises, un appareil idÃĐologique d'Ãtat

June 2007 etc.) as well as NGOs such as ''Les BlÃĐdardes'' (led by Bouteldja), criticized the

feminist

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideology, ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social gender equality, equality of the sexes. Feminism holds the position that modern soci ...

thought and movements in France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

. Feminism in France can be roughly divided into three waves: First-wave feminism

First-wave feminism was a period of feminist activity and thought that occurred during the 19th and early 20th century throughout the Western world. It focused on De jure, legal issues, primarily on securing women's right to vote. The term is oft ...

from the French Revolution through the Third Republic which was concerned chiefly with suffrage

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise is the right to vote in public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in English, the right to v ...

and civic rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' political freedom, freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and ...

for women. Significant contributions came from revolutionary movements of the French Revolution of 1848

The French Revolution of 1848 (), also known as the February Revolution (), was a period of civil unrest in France, in February 1848, that led to the collapse of the July Monarchy and the foundation of the French Second Republic. It sparked t ...

and Paris Commune

The Paris Commune (, ) was a French revolutionary government that seized power in Paris on 18 March 1871 and controlled parts of the city until 28 May 1871. During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870â71, the French National Guard (France), Nation ...

, culminating in 1944 when women gained the right to vote.

Second-wave feminism

Second-wave feminism was a period of feminist activity that began in the early 1960s and lasted roughly two decades, ending with the feminist sex wars in the early 1980s and being replaced by third-wave feminism in the early 1990s. It occurred ...

began in the 1940s as a reevaluation of women's role in society, reconciling the inferior treatment of women in society despite their ostensibly equal political status to men. Pioneered by theorists such as Simone de Beauvoir

Simone Lucie Ernestine Marie Bertrand de Beauvoir (, ; ; 9 January 1908 â 14 April 1986) was a French existentialist philosopher, writer, social theorist, and feminist activist. Though she did not consider herself a philosopher, nor was she ...

, second wave feminism was an important current within the social turmoil leading up to and following the May 1968 events in France

May 68 () was a period of widespread protests, strikes, and civil unrest in France that began in May 1968 and became one of the most significant social uprisings in modern European history. Initially sparked by student demonstrations agains ...

. Political goals included the guarantee of increased bodily autonomy

Bodily integrity is the inviolability of the physical body and emphasizes the importance of personal autonomy, self-ownership, and self-determination of human beings over their own bodies. In the field of human rights, violation of the bodily int ...

for women via increased access to abortion

Abortion is the early termination of a pregnancy by removal or expulsion of an embryo or fetus. Abortions that occur without intervention are known as miscarriages or "spontaneous abortions", and occur in roughly 30â40% of all pregnan ...

and birth control

Birth control, also known as contraception, anticonception, and fertility control, is the use of methods or devices to prevent pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth control only be ...

.

Third-wave feminism

Third-wave feminism is a feminist movement that began in the early 1990s, prominent in the decades prior to the fourth-wave feminism, fourth wave. Grounded in the civil-rights advances of the second-wave feminism, second wave, Generation X, Gen X ...

since the 2000s continues the legacy of the second wave while adding elements of postcolonial feminism

Postcolonial feminism is a form of feminism that developed as a response to feminism focusing solely on the experiences of women in Western cultures and former colonies. Postcolonial feminism seeks to account for the way that racism and the long- ...

, approaching women's rights in tandem with other ongoing discourses, particularly those surrounding racism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one Race (human categorization), race or ethnicity over another. It may also me ...

.

First-wave feminism

The French Revolution

In November 1789, at the very beginning of the French Revolution, the Women's Petition was addressed to the National Assembly but not discussed. Although variousfeminist movements

The feminist movement, also known as the women's movement, refers to a series of social movements and political campaigns for radical and liberal reforms on women's issues created by inequality between men and women. Such issues are women's l ...

emerged during the Revolution, most politicians followed Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; ; 28 June 1712 â 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher ('' philosophe''), writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects ...

's theories as outlined in '' Emile'', which confined women to the roles of mother and spouse. The philosopher Condorcet

Marie Jean Antoine Nicolas de Caritat, Marquis of Condorcet (; ; 17 September 1743 â 29 March 1794), known as Nicolas de Condorcet, was a French philosopher, political economist, politician, and mathematician. His ideas, including suppo ...

was a notable exception who advocated equal rights for both sexes.

The ''SociÃĐtÃĐ fraternelle de l'un et l'autre sexe

The Fraternal Society of Patriots of Both Sexes, Defenders of the Constitution () was a French revolutionary organization notable in the history of feminism as an early example of active participation of women in politics.

History

The Fratern ...

'' ("Fraternal Society of Both Sexes") was founded in 1790 by Claude Dansart Claude may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Claude (given name), a list of people and fictional characters

* Claude (surname), a list of people

* Claude Callegari (1962â2021), English Arsenal supporter

* Claude Debussy (1862â1918), ...

. It included prominent individuals such as Etta Palm d'Aelders

Etta Lubina Johanna Palm d'Aelders (April 1743 – 28 March 1799), also known as the Baroness of Aelders, was a Dutch spy and feminist, outspoken during the French Revolution. She gave the address ''Discourse on the Injustice of the Laws in F ...

, Jacques HÃĐbert

Jacques RenÃĐ HÃĐbert (; 15 November 1757 â 24 March 1794) was a French journalist and leader of the French Revolution. As the founder and editor of the radical newspaper ''Le PÃĻre Duchesne'', he had thousands of followers known as ''the ...

, Louise-FÃĐlicitÃĐ de KÃĐralio

Louise-FÃĐlicitÃĐ Guynement de KÃĐralio (25 August 1758 in Valence, DrÃīme â 31 December 1821 in Brussels) was a French writer and translator, originating from the minor Brittany, Breton nobility.

Her father was Louis-FÃĐlix Guynement de KÃĐr ...

, Pauline LÃĐon

Pauline LÃĐon (28 September 1768 â 5 October 1838) was an influential woman during the French Revolution. She played an important role in the Revolution, driven by her strong feminist and anti-royalist beliefs. Along with her friend Claire Lacom ...

, ThÃĐroigne de MÃĐricourt

Anne-JosÃĻphe ThÃĐroigne de MÃĐricourt (born ''Anne-JosÃĻphe Terwagne''; 13 August 1762 â 8 June 1817) was a Belgian singer, orator and organizer in the French Revolution. She was born at Marcourt, in the Prince-Bishopric of LiÃĻge (from whi ...

, Madame Roland

Marie-Jeanne "Manon" Roland de la PlatiÃĻre (Paris, March 17, 1754 – Paris, November 8, 1793), born Marie-Jeanne Phlipon, and best known under the name Madame RolandOccasionally, she is referred to as Dame Roland. This however is the except ...

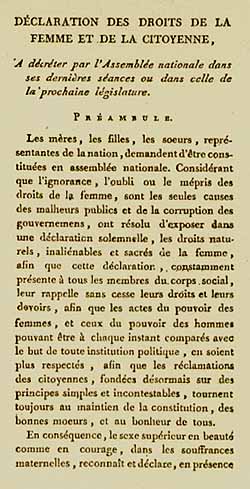

, ThÃĐrÃĐsa CabarrÚs, and Merlin de Thionville. The following year, Olympe de Gouges

Olympe de Gouges (; born Marie Gouze; 7 May 17483 November 1793) was a French playwright and political activist. She is best known for her Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen and other writings on women's rights and Abol ...

published the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen

The Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen (), also known as the Declaration of the Rights of Woman, was written on 14 September 1791 by French activist, Feminism in France, feminist, and playwright Olympe de Gouges in res ...

. This was a letter addressed to Queen Marie Antoinette

Marie Antoinette (; ; Maria Antonia Josefa Johanna; 2 November 1755 â 16 October 1793) was the last List of French royal consorts, queen of France before the French Revolution and the establishment of the French First Republic. She was the ...

which requested actions in favour of women's rights

Women's rights are the rights and Entitlement (fair division), entitlements claimed for women and girls worldwide. They formed the basis for the women's rights movement in the 19th century and the feminist movements during the 20th and 21st c ...

. Gouges was guillotine

A guillotine ( ) is an apparatus designed for effectively carrying out executions by Decapitation, beheading. The device consists of a tall, upright frame with a weighted and angled blade suspended at the top. The condemned person is secur ...

d two years later, days after the execution of the Girondin

The Girondins (, ), also called Girondists, were a political group during the French Revolution. From 1791 to 1793, the Girondins were active in the Legislative Assembly and the National Convention. Together with the Montagnards, they initiall ...

s.

In February 1793, Pauline LÃĐon

Pauline LÃĐon (28 September 1768 â 5 October 1838) was an influential woman during the French Revolution. She played an important role in the Revolution, driven by her strong feminist and anti-royalist beliefs. Along with her friend Claire Lacom ...

and Claire Lacombe

Claire Lacombe (4 August 1765 â 2 May 1826) was a French actress and revolutionary. She is best known for her contributions during the French Revolution. Though it was only for a few years, Lacombe was a revolutionary and a founding member of ...

created the exclusively-female ''SociÃĐtÃĐ des rÃĐpublicaines rÃĐvolutionnaires

The Society of Revolutionary and Republican Women (, ') was a female-led revolutionary organization during the French Revolution. The Society officially began on May 10, 1793, and disbanded on September 16 of the same year. The Society managed to ...

'' (Society of Revolutionary Republicansâthe final ''e'' in ''rÃĐpublicaines'' explicitly denoting Republican Women), which boasted two hundred members. Viewed by the historian Daniel GuÃĐrin

Daniel GuÃĐrin (; 19 May 1904 â 14 April 1988) was a French libertarian-communist author, best known for his work '' Anarchism: From Theory to Practice'', as well as his collection ''No Gods No Masters: An Anthology of Anarchism'' in which h ...

as a sort of "feminist section of the ''EnragÃĐs

The EnragÃĐs (; ), commonly known as the Ultra-radicals (), were a small number of firebrands known for defending the lower class and expressing the demands of the radical ''sans-culottes'' during the French Revolution.Jeremy D. Popkin (2015). ' ...

''",Daniel GuÃĐrin

Daniel GuÃĐrin (; 19 May 1904 â 14 April 1988) was a French libertarian-communist author, best known for his work '' Anarchism: From Theory to Practice'', as well as his collection ''No Gods No Masters: An Anthology of Anarchism'' in which h ...

, ''La lutte des classes'', 1946 they participated in the fall of the Girondins. Lacombe advocated giving weapons to women. However, the Society was outlawed by the revolutionary government in the following year.

From the Restoration to the Second Republic

The feminist movement expanded again inSocialist

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

movements of the Romantic generation, in particular among Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

ian Saint Simonians. Women freely adopted new lifestyles, inciting indignation in public opinion

Public opinion, or popular opinion, is the collective opinion on a specific topic or voting intention relevant to society. It is the people's views on matters affecting them.

In the 21st century, public opinion is widely thought to be heavily ...

. They claimed equality of rights and participated in the abundant literary activity, such as Claire DÃĐmar's ''Appel au peuple sur l'affranchissement de la femme'' (1833), a feminist pamphlet

A pamphlet is an unbound book (that is, without a Hardcover, hard cover or Bookbinding, binding). Pamphlets may consist of a single sheet of paper that is printed on both sides and folded in half, in thirds, or in fourths, called a ''leaflet'' ...

. On the other hand, Charles Fourier

François Marie Charles Fourier (; ; 7 April 1772 â 10 October 1837) was a French philosopher, an influential early socialist thinker, and one of the founders of utopian socialism. Some of his views, held to be radical in his lifetime, have be ...

's Utopian Socialist

Utopian socialism is the term often used to describe the first current of modern socialism and socialist thought as exemplified by the work of Henri de Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier, Ãtienne Cabet, and Robert Owen. Utopian socialism is often ...

theory of passions advocated "free love

Free love is a social movement that accepts all forms of love. The movement's initial goal was to separate the State (polity), state from sexual and romantic matters such as marriage, birth control, and adultery. It stated that such issues we ...

." His architectural model of the '' phalanstery'' community explicitly took into account women's emancipation.

The Bourbon Restoration Bourbon Restoration may refer to:

France under the House of Bourbon:

* Bourbon Restoration in France (1814, after the French revolution and Napoleonic era, until 1830; interrupted by the Hundred Days in 1815)

Spain under the Spanish Bourbons:

* Ab ...

re-established the prohibition of divorce

Divorce (also known as dissolution of marriage) is the process of terminating a marriage or marital union. Divorce usually entails the canceling or reorganising of the legal duties and responsibilities of marriage, thus dissolving the M ...

in 1816. When the July Monarchy

The July Monarchy (), officially the ''Kingdom of France'' (), was a liberalism, liberal constitutional monarchy in France under , starting on 9 August 1830, after the revolutionary victory of the July Revolution of 1830, and ending 26 Februar ...

restricted the political rights of the majority of the population, the feminist struggle rejoined the Republican and Socialist struggle for a "Democratic and Social Republic," leading to the 1848 Revolution

The revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the springtime of the peoples or the springtime of nations, were a series of revolutions throughout Europe over the course of more than one year, from 1848 to 1849. It remains the most widespre ...

and the proclamation of the Second Republic. The 1848 Revolution became the occasion of a public expression of the feminist movement, who organized itself in various associations. Women's political activities led several of them to be proscribed as the other Forty-Eighters.

Belle Ãpoque Era

During the culturally thriving times of theBelle Ãpoque

The Belle Ãpoque () or La Belle Ãpoque () was a period of French and European history that began after the end of the Franco-Prussian War in 1871 and continued until the outbreak of World War I in 1914. Occurring during the era of the Fr ...

, especially in the late nineteenth century, feminism and the view of femininity experienced substantial shifts evident through acts by women of boldness and rejection of previous stigmas. The most defining characteristic of this period shown by these actions is the power of choice women began to take hold of. Such acts included these women partaking in nonstandard ways of marriageâas divorce during this time had been legally reinstalled as a result of the Naquet Lawsâpracticing gender role-defying jobs, and profoundly influencing societal ideologies regarding femininity through writings.

Feminist newspapers quickly became more widespread and took a role in transforming both the view of women and their rights. As this era held promise of equality, proceeding after the French Revolution, women still had yet to gain the title of equal citizens, making it a difficult and dangerous venture to publicize opinions promoting the advancement of women's rights. Among these newspapers, the most notable is Marguerite Durand's '' La Fronde'', run entirely by women.

The Commune and the ''Union des Femmes''

Some women organized a feminist movement during the Commune, following up on earlier attempts in 1789 and 1848. Nathalie Lemel, a socialist bookbinder, and

Some women organized a feminist movement during the Commune, following up on earlier attempts in 1789 and 1848. Nathalie Lemel, a socialist bookbinder, and Ãlisabeth Dmitrieff

Elisabeth Dmitrieff (born Elizaveta Lukinichna Kusheleva, , also known as Elizaveta Tomanovskaya; 1 November 1850 â probably between 1916 and 1918) was a Russian revolutionary and feminist activist. The illegitimate daughter of a Russian aris ...

, a young Russian exile and member of the Russian section of the First International

The International Workingmen's Association (IWA; 1864â1876), often called the First International, was a political international which aimed at uniting a variety of different left-wing socialist, social democratic, communist, and anarchist ...

(IWA), created the ''Union des femmes pour la dÃĐfense de Paris et les soins aux blessÃĐs

''Union des femmes pour la dÃĐfense de Paris et les soins aux blessÃĐs'' () was a women's group during the 1871 Paris Commune. The union organized working women, ensured a market and fair pay for their work, and participated in the defence of P ...

'' ("Women's Union for the Defense of Paris and Care of the Injured") on 11 April 1871. The feminist writer AndrÃĐ LÃĐo, a friend of Paule Minck, was also active in the Women's Union. The association demanded gender equality

Gender equality, also known as sexual equality, gender egalitarianism, or equality of the sexes, is the state of equal ease of access to resources and opportunities regardless of gender, including economic participation and decision-making, an ...

, wage equality, right of divorce

Divorce (also known as dissolution of marriage) is the process of terminating a marriage or marital union. Divorce usually entails the canceling or reorganising of the legal duties and responsibilities of marriage, thus dissolving the M ...

for women, and right to secular

Secularity, also the secular or secularness (from Latin , or or ), is the state of being unrelated or neutral in regards to religion. The origins of secularity can be traced to the Bible itself. The concept was fleshed out through Christian hi ...

and professional education for girls. They also demanded suppression of the distinction between married women and concubine

Concubinage is an interpersonal relationship, interpersonal and Intimate relationship, sexual relationship between two people in which the couple does not want to, or cannot, enter into a full marriage. Concubinage and marriage are often regarde ...

s, between legitimate and natural children, the abolition of prostitution

Prostitution is a type of sex work that involves engaging in sexual activity in exchange for payment. The definition of "sexual activity" varies, and is often defined as an activity requiring physical contact (e.g., sexual intercourse, no ...

in closing the ''maisons de tolÃĐrance'', or legal official brothel

A brothel, strumpet house, bordello, bawdy house, ranch, house of ill repute, house of ill fame, or whorehouse is a place where people engage in Human sexual activity, sexual activity with prostitutes. For legal or cultural reasons, establis ...

s.

The Women's Union also participated in several municipal commissions and organized cooperative workshops. Along with EugÃĻne Varlin, Nathalie Le Mel created the cooperative

A cooperative (also known as co-operative, coÃķperative, co-op, or coop) is "an autonomy, autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly owned a ...

restaurant ''La Marmite'', which served free food for indigents, and then fought during the Bloody Week on the barricades.François Bodinaux, Dominique Plasman, MichÃĻle Ribourdouille. "On les disait 'pÃĐtroleuses'...

''" On the other hand, Paule Minck opened a free school in the Church of Saint Pierre de Montmartre, and animated the Club Saint-Sulpice on the Left Bank. The Russian

Anne Jaclard

Anne Jaclard, born Anna Vasilyevna Korvin-Krukovskaya (1843â1887), was a Russian socialism, socialist and feminism, feminist revolutionary. She participated in the Paris Commune and the First International and was a friend of Karl Marx. She was ...

, who declined to marry Dostoievsky and finally became the wife of Blanquist

Blanquism () refers to a conception of revolution generally attributed to Louis Auguste Blanqui (1805â1881) that holds that socialist revolution should be carried out by a relatively small group of highly organised and secretive conspirators. H ...

activist Victor Jaclard

Charles Victor Jaclard (1840â1903) was a French revolutionary socialist, a member of the First International and of the Paris Commune. Jaclard is noted for his political adaptability and the ease with which he maintained good personal as well a ...

, founded with AndrÃĐ LÃĐo the newspaper '' La Sociale''. She was also a member of the '' ComitÃĐ de vigilance de Montmartre'', along with Louise Michel and Paule Minck, as well as of the Russian section of the First International

The International Workingmen's Association (IWA; 1864â1876), often called the First International, was a political international which aimed at uniting a variety of different left-wing socialist, social democratic, communist, and anarchist ...

. Victorine Brocher

Victorine Brocher (1839â1921) was a Communard and anarchist. She participated in the Paris Commune and later wrote a memoir detailing her experience. Brocher was a delegate to the 1881 London Anarchist Congress and a contributor to anarchis ...

, close to the IWA activists and founder of a cooperative bakery in 1867, also fought during the Commune and the Bloody Week.

Famous figures such as Louise Michel

Louise Michel (; 29 May 1830 â 9 January 1905) was a teacher and prominent figure during the Paris Commune. Following her penal transportation to New Caledonia she began to embrace anarchism, and upon her return to France she emerged as an im ...

, the "Red Virgin of Montmartre" who joined the National Guard

National guard is the name used by a wide variety of current and historical uniformed organizations in different countries. The original National Guard was formed during the French Revolution around a cadre of defectors from the French Guards.

...

and would later be sent to New Caledonia

New Caledonia ( ; ) is a group of islands in the southwest Pacific Ocean, southwest of Vanuatu and east of Australia. Located from Metropolitan France, it forms a Overseas France#Sui generis collectivity, ''sui generis'' collectivity of t ...

, symbolize the active participation of a small number of women in the insurrectionary events. A female battalion from the National Guard defended the Place Blanche

The Place Blanche () in Paris, France, is one of the small plazas along the Boulevard de Clichy, which runs between the 9th and 18th arrondissements (Parisian districts) and leads into Montmartre. It is near Pigalle.

The famous cabaret Moulin ...

during the repression.

The ''suffragettes''

In 1909, French noblewoman and feminist Jeanne-Elizabeth Schmahl founded the

In 1909, French noblewoman and feminist Jeanne-Elizabeth Schmahl founded the French Union for Women's Suffrage

The French Union for Women's Suffrage (UFSF: ) was a French feminist organization formed in 1909 that fought for the right of women to vote, which was eventually granted in 1945. The Union took a moderate approach, advocating staged introduction o ...

to advocate for women's right to vote

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise is the right to vote in representative democracy, public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in ...

in France.

Despite some cultural changes following World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 â 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, which had resulted in women replacing the male workers who had gone to the front, they were known as the ''AnnÃĐes folles

The ''AnnÃĐes folles'' (, "crazy years" in French) was the decade of the 1920s in France. It was coined to describe the social, artistic, and cultural collaborations of the period. The same period is also referred to as the Roaring Twenties ...

'' and their exuberance was restricted to a very small group of female elites. Victor Margueritte

Victor Margueritte (1 December 186623 March 1942) was a French novelist. He was the younger brother of Paul Margueritte (1860–1918).

Life

He and his brother were born in Algeria. They were the sons of General Jean Auguste Margueritte (182 ...

's '' La Garçonne'' (The Flapper, 1922), depicting an emancipated woman, was seen as scandalous and caused him to lose his ''Legion of Honour

The National Order of the Legion of Honour ( ), formerly the Imperial Order of the Legion of Honour (), is the highest and most prestigious French national order of merit, both military and Civil society, civil. Currently consisting of five cl ...

''.

During the Third Republic, the ''suffragettes

A suffragette was a member of an activist women's organisation in the early 20th century who, under the banner "Votes for Women", fought for women's suffrage, the right to vote in public elections in the United Kingdom. The term refers in part ...

'' movement championed the right to vote

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise is the right to vote in representative democracy, public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in ...

for women, but did not insist on the access of women to legislative and executive offices.Christine BardLes premiÃĻres femmes au Gouvernement (France, 1936-1981)

'' Histoire@Politique'', n°1, MayâJune 2007 The ''suffragettes'', however, did honour the achievements of foreign women in power by bringing attention to legislation passed under their influence concerning alcohol (such as

Prohibition in the United States

The Prohibition era was the period from 1920 to 1933 when the United States prohibited the production, importation, transportation, and sale of alcoholic beverages. The alcohol industry was curtailed by a succession of state legislatures, an ...

), regulation of prostitution

Prostitution is a type of sex work that involves engaging in sexual activity in exchange for payment. The definition of "sexual activity" varies, and is often defined as an activity requiring physical contact (e.g., sexual intercourse, no ...

, and protection of children's rights

Children's rights or the rights of children are a subset of human rights with particular attention to the rights of special protection and care afforded to minors.

.

Despite this campaign and the new role of women following World War I, the Third Republic declined to grant them voting rights, mainly because of fear of the influence of clericalism

Clericalism is the application of the formal, church-based leadership or opinion of ordained clergy in matters of the church or in broader political and sociocultural contexts.

The journalist has stated that clericalism was not part of the Gospe ...

among them, echoing the conservative vote of rural areas for Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon III (Charles-Louis NapolÃĐon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was President of France from 1848 to 1852 and then Emperor of the French from 1852 until his deposition in 1870. He was the first president, second emperor, and last ...

during the Second Republic. After the 1936 Popular Front victory, although he had defended voting rights for women (a proposition included in the program of the French Section of the Workers' International

The French Section of the Workers' International (, SFIO) was a major socialist political party in France which was founded in 1905 and succeeded in 1969 by the present Socialist Party.

The SFIO was founded in 1905 as the French representativ ...

party since 1906), left-wing Prime Minister LÃĐon Blum

AndrÃĐ LÃĐon Blum (; 9 April 1872 â 30 March 1950) was a French socialist politician and three-time Prime Minister of France. As a Jew, he was heavily influenced by the Dreyfus affair of the late 19th century. He was a disciple of socialist l ...

did not implement the measure, because of the fear of the Radical-Socialist Party.

Women obtained the right to vote

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise is the right to vote in representative democracy, public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in ...

only after the Provisional Government of the French Republic

The Provisional Government of the French Republic (PGFR; , GPRF) was the provisional government of Free France between 3 June 1944 and 27 October 1946, following the liberation of continental France after Operations ''Overlord'' and ''Drago ...

(GPRF) confirmed, on 5 October 1944, the ordinance

Ordinance may refer to:

Law

* Ordinance (Belgium), a law adopted by the Brussels Parliament or the Common Community Commission

* Ordinance (India), a temporary law promulgated by the President of India on recommendation of the Union Cabinet

* Em ...

of 21 April 1944 of the French Committee of National Liberation

French may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France

** French people, a nation and ethnic group

** French cuisine, cooking traditions and practices

Arts and media

* The French (band) ...

. Following the November 1946 elections, the first in which women were permitted to vote, sociologist Robert Verdier refuted any voting gender gap: in May 1947 in ''Le Populaire

''Le Populaire'' is a major independent daily newspaper in Senegal

Senegal, officially the Republic of Senegal, is the westernmost country in West Africa, situated on the Atlantic Ocean coastline. It borders Mauritania to MauritaniaâSenegal ...

'', he showed that women do not vote in a consistent way but divide themselves, as men, according to social classes.

Other rights for women

Olga Petit, born Scheina Lea-Balachowsky and also referred to as Sonia Olga Balachowsky-Petit, became the first femalelawyer

A lawyer is a person who is qualified to offer advice about the law, draft legal documents, or represent individuals in legal matters.

The exact nature of a lawyer's work varies depending on the legal jurisdiction and the legal system, as w ...

in France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

on 6 December 1900.

Marital power

In civil law jurisdictions, marital power (, , ) was a doctrine in terms of which a wife was legally an '' incapax'' under the usufructory tutorship (''tutela usufructuaria'') of her husband. The marital power included the power of the husband to ...

(puissance maritale) was abolished in 1938. However, the legal repeal of the specific doctrine of ''marital power'' does not necessarily grant married women the same legal rights as their husbands (or as unmarried women) as was notably the case in France, where the legal subordination of the wife (primarily coming from the Napoleonic Code

The Napoleonic Code (), officially the Civil Code of the French (; simply referred to as ), is the French civil code established during the French Consulate in 1804 and still in force in France, although heavily and frequently amended since i ...

) was gradually abolished with women obtaining full equality in marriage only in the 1980s.

Second-wave feminism

War years

The ''Union des femmes françaises

("Women in solidarity") is a French feminist association in France, founded during the Second World War under the name Union des femmes françaises (UFF). The movement works for the defense and advancement of women's rights, gender equality, ...

'' had its origins in France during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 â 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. Women's committees of the French Resistance

The French Resistance ( ) was a collection of groups that fought the German military administration in occupied France during World War II, Nazi occupation and the Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy#France, collaborationist Vic ...

were born of the grassroots Resistance committees created by Danielle Casanova

Danielle Casanova (; born Vincentella Perini; 9 January 1909 â 9 May 1943) was a French communist activist and member of the French Resistance during World War II. A dentist by occupation, she was a high-ranking figure within the Communist Yo ...

. These women's committees gradually took shape at local levels, then at the regional and inter-regional level. They were regrouped within the Union des femmes françaises in the zone occupÃĐe

The Military Administration in France (; ) was an interim occupation authority established by Nazi Germany during World War II to administer the occupied zone in areas of northern and western France. This so-called ' was established in June 19 ...

and the Union des femmes de France in the zone libre

The ''zone libre'' (, ''free zone'') was a partition of the French metropolitan territory during World War II, established at the Second Armistice at CompiÃĻgne on 22 June 1940. It lay to the south of the demarcation line and was administered b ...

. The leaders were , then Maria RabatÃĐ

Maria RabatÃĐ (3 July 1900 - 8 February 1985) was a French politician, writer, and school teacher. She was a member of the French Communist Party, trade unionist, and elected representative of the 1st district of Seine in the French Parliament, ...

for the northern zone, after the arrest of Danielle Casanova and Marcelle Barjonet. and Simone Bertrand in the .

Post-war period

Women were not allowed to become judges in France until 1946. During thebaby boom

A baby boom is a period marked by a significant increase of births. This demography, demographic phenomenon is usually an ascribed characteristic within the population of a specific nationality, nation or culture. Baby booms are caused by various ...

period, feminism became a minor movement, despite forerunners such as Simone de Beauvoir

Simone Lucie Ernestine Marie Bertrand de Beauvoir (, ; ; 9 January 1908 â 14 April 1986) was a French existentialist philosopher, writer, social theorist, and feminist activist. Though she did not consider herself a philosopher, nor was she ...

, who published ''The Second Sex

''The Second Sex'' () is a 1949 book by the French existentialist philosopher Simone de Beauvoir, in which the author discusses the treatment of women in the present society as well as throughout all of history. Beauvoir researched and wrote th ...

'' in 1949.

''The Second Sex'' is a detailed analysis of women's oppression and a foundational tract of contemporary feminism. It sets out a feminist existentialism

Feminism is a collection of movements aimed at defining, establishing, and defending equal political, economic, and social rights for women. Existentialism is a philosophical and cultural movement which holds that the starting point of philosophi ...

which prescribes a moral revolution. As an existentialist

Existentialism is a family of philosophical views and inquiry that explore the human individual's struggle to lead an authentic life despite the apparent absurdity or incomprehensibility of existence. In examining meaning, purpose, and value ...

, de Beauvoir accepted Jean-Paul Sartre's precept that ''existence precedes essence

The proposition that existence precedes essence () is a central claim of existentialism, which reverses the traditional philosophical view that the essence (the nature) of a thing is more fundamental and immutable than its existence (the mere f ...

''; hence "one is not born a woman, but becomes one". Her analysis focuses on the social construction of Woman as the Other, this de Beauvoir identifies as fundamental to women's oppression. She argues that women have historically been considered deviant and abnormal, and contends that even Mary Wollstonecraft

Mary Wollstonecraft ( , ; 27 April 175910 September 1797) was an English writer and philosopher best known for her advocacy of women's rights. Until the late 20th century, Wollstonecraft's life, which encompassed several unconventional ...

considered men to be the ideal toward which women should aspire. De Beauvoir argues that for feminism to move forward, this attitude must be set aside.

Married French women obtained the right to work without their husband's consent in 1965. The Neuwirth Law The Neuwirth Law is a French law which lifted the ban on birth control methods on December 28, 1967, including oral contraception. It was passed by the National Assembly on December 19, 1967. The law is named after Lucien Neuwirth, the Gaullist pol ...

legalized birth control in 1967, but the relative executive decrees were blocked for a couple years by the conservative government.

May 1968 and its aftermath

A strong feminist movement would only emerge in the aftermath ofMay 1968

The following events occurred in May 1968:

May 1, 1968 (Wednesday)

*In Dallas, at its first meeting since its creation through a merger, the United Methodist Church removed its rule that Methodist ministers could not drink alcohol nor sm ...

, with the creation of the ''Mouvement de libÃĐration des femmes

The Mouvement de libÃĐration des femmes (MLF, ) is a French autonomous, single-sex feminist movement that advocates women's bodily autonomy and challenges patriarchal society. It was founded in 1970, in the wake of the American Women's Lib mov ...

'' (Women's Liberation Movement, MLF), allegedly by Antoinette Fouque

Antoinette Fouque (Birth name, nÃĐe Antoinette Grugnardi; 1 October 1936 â 20 February 2014) was a French psychoanalysis, psychoanalyst who was involved in the French women's liberation movement. She was the leader of one of the groups that orig ...

, Monique Wittig

Monique Wittig (; 13 July 1935 â 3 January 2003) was a French author, philosopher, and feminist theorist who wrote about abolition of the sex-class system and coined the phrase "heterosexual contract." Her groundbreaking work is titled '' The ...

and Josiane Chanel in 1968. The name itself was given by the press, in reference to the US Women's Lib

The women's liberation movement (WLM) was a political alignment of women and feminism, feminist intellectualism. It emerged in the late 1960s and continued till the 1980s, primarily in the industrialized nations of the Western world, which resu ...

movement. In the frame of the cultural and social changes that occurred during the Fifth Republic, they advocated the right of autonomy from their husbands, and the rights to contraception

Birth control, also known as contraception, anticonception, and fertility control, is the use of methods or devices to prevent pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth control only be ...

and to abortion

Abortion is the early termination of a pregnancy by removal or expulsion of an embryo or fetus. Abortions that occur without intervention are known as miscarriages or "spontaneous abortions", and occur in roughly 30â40% of all pregnan ...

.

The paternal authority of a man over his family in France was ended in 1970 (before that parental responsibilities belonged solely to the father who made all legal decisions concerning the children).

From 1970, the procedures for the use of the title " Mademoiselle" were challenged in France, particularly by feminist groups who wanted it banned. A circular from François Fillon

François Charles Amand Fillon (; born 4 March 1954) is a French retired politician who served as Prime Minister of France from 2007 to 2012 under President Nicolas Sarkozy. He was the nominee of The Republicans (previously known as the Union ...

, then Prime Minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

, dated 21 February 2012, called for the deletion of the word "Mademoiselle" in all official documents. On 26 December 2012, the Council of State

A council of state is a governmental body in a country, or a subdivision of a country, with a function that varies by jurisdiction. It may be the formal name for the cabinet or it may refer to a non-executive advisory body associated with a head ...

approved the deletion.

In 1971, the feminist lawyer GisÃĻle Halimi

GisÃĻle Halimi (born Zeiza GisÃĻle Ãlise TaÃŊeb, ; 27 July 1927 â 28 July 2020) was a Tunisian-French lawyer, politician, essayist and feminist activist.

Biography

Zeiza GisÃĻle Ãlise TaÃŊeb was born in La Goulette, Tunisia, on 27 July 192 ...

founded the group ''Choisir'' ("To Choose"), to protect the women who had signe"Le Manifeste des 343 Salopes"

(in English " Manifesto of the 343 Sluts" or alternately "Manifesto of the 343 Bitches"), written by

Simone de Beauvoir

Simone Lucie Ernestine Marie Bertrand de Beauvoir (, ; ; 9 January 1908 â 14 April 1986) was a French existentialist philosopher, writer, social theorist, and feminist activist. Though she did not consider herself a philosopher, nor was she ...

. This provocative title became popular after Cabu's drawing on a satirical journal with the caption: ''ÂŦ Who got those 343 whores pregnant? Âŧ''); the women were admitting to have had illegal abortions, and therefore exposing themselves to judicial actions and prison sentences. The Manifesto had been published in ''Le Nouvel Observateur

(), previously known as (2014â2024), (1964â2014), (1954â1964), (1953â1954), and (1950â1953), is a weekly French news magazine. Based in the 2nd arrondissement of Paris, ' is one of the three most prominent French news magazines ...

'' on 5 April 1971. The Manifesto was the inspiration for a 3 February 1973, manifesto by 331 doctors declaring their support for abortion rights:

We want freedom of abortion. It is entirely the woman's decision. We reject any entity that forces her to defend herself, perpetuates an atmosphere of guilt, and allows underground abortions to persist ....''Choisir'' had transformed into a clearly reformist body in 1972, and their campaign greatly influenced the passing of the law allowing contraception and abortion carried through by

Simone Veil

Simone Veil (; ; 13 July 1927 â 30 June 2017) was a French magistrate, Holocaust survivor, and politician who served as health minister in several governments and was President of the European Parliament from 1979 to 1982, the first woman t ...

in 1975. The Veil Act was at the time hotly contested by Veil's own party, the conservative Union for French Democracy

The Union for French Democracy ( ; UDF) was a centre-right political party in France. The UDF was founded in 1978 as an electoral alliance to support President ValÃĐry Giscard d'Estaing in order to counterbalance the Gaullist preponderance over ...

(UDF).

In 1974, Françoise d'Eaubonne

Françoise d'Eaubonne (; 12 March 1920 â 3 August 2005) was a French author, labour rights activist, environmentalist, and feminist. Her 1974 book, ''Le FÃĐminisme ou la Mort'', introduced the term ecofeminism. She co-founded the Front homos ...

coined the term "ecofeminism

Ecofeminism integrates feminism and political ecology. Ecofeminist thinkers draw on the concept of gender to analyze relationships between humans and the natural world. The term was coined by the French writer Françoise d'Eaubonne in her 1974 ...

."

A new reform in France in 1985 abolished the stipulation that the father had the sole power to administer the children's property.

In 1999, Florence Montreynaud launched the '' Chiennes de garde'' NGO.French feminist theory

In the English-speaking world, the term "French feminism" refers to a branch of theories and philosophies by and about women that emerged in the 1970s to the 1990s. These ideas have run parallel to and sometimes in contradistinction to the political feminist movement in France but is often referred to as "French feminist theory," distinguished by an approach which is more philosophical and literary. Its writings tend to be effusive and metaphorical being less concerned with political doctrine and generally focused on theories of "the body". The term includes writers who are not French, but who have worked substantially in France and the French tradition. In the 1970s, French writers approached feminism with the concept of ''ÃĐcriture fÃĐminine

''Ãcriture fÃĐminine'', or "women's writing", is a term coined by French feminist and literary theorist HÃĐlÃĻne Cixous in her 1975 essay "The Laugh of the Medusa". Cixous aimed to establish a genre of literary writing that deviates from tradit ...

'' (which translates as female, or feminine writing).Wright, Elizabeth (2000). ''Lacan and Postfeminism (Postmodern Encounters)''. Totem Books or Icon Books. . HÃĐlÃĻne Cixous

HÃĐlÃĻne Cixous (; ; born 5 June 1937) is a French writer, playwright and Literary criticism, literary critic. During her academic career, she was primarily associated with the Centre universitaire de Vincennes (today's University of Paris VIII) ...

argues that writing and philosophy are phallocentric

Phallocentrism is the ideology that the phallus, or male sexual organ, is the central element in the organization of the social world. Phallocentrism has been analyzed in literary criticism, psychoanalysis and psychology, linguistics, medicine and ...

and along with other French feminists such as Luce Irigaray

Luce Irigaray (; born 3 May 1930) is a Belgian-born French feminist, philosopher, linguist, psycholinguist, psychoanalyst, and cultural theorist who examines the uses and misuses of language in relation to women.

Irigaray's first and most ...

emphasize "writing from the body" as a subversive exercise. The work of psychoanalyst and philosopher Julia Kristeva

Julia Kristeva (; ; born Yuliya Stoyanova Krasteva, ; on 24 June 1941) is a Bulgarian-French philosopher, literary critic, semiotician, psychoanalyst, feminist, and novelist who has lived in France since the mid-1960s. She has taught at Colum ...

has influenced feminist theory in general and feminist literary criticism

Feminist literary criticism is literary criticism informed by feminist theory, or more broadly, by the politics of feminism. It uses the principles and ideology of feminism to critique the language of literature. This school of thought seeks to an ...

in particular. From the 1980s onwards the work of the artist and psychoanalyst Bracha Ettinger

Bracha Lichtenberg Ettinger (; born 23 March 1948) is an Israeli-French artist, writer, psychoanalyst and philosopher based in France. Born in Mandatory Palestine, she lives and works in Paris. She is a feminist theorist and artist in contempora ...

has influenced literary criticism, art history and film theory.

Through their own concept of French feminism, American academics separated and ignored the already marginalized self-identifying feminists, while focusing on the women theorists associated with Psych et po and other academics who did not always identify as feminists themselves. This division ended up placing more importance on the theories of the French feminists than the political agenda and goals that groups such as radical feminists and the MLF had at the time.

Third-wave feminism

In the 2000s, some feminist groups such as '' Ni putes, ni soumises'' (Neither Whores, Nor Submissives) denounced an increased influence ofIslamic extremism

Islamic extremism refers to extremist beliefs, behaviors and ideologies adhered to by some Muslims within Islam. The term 'Islamic extremism' is contentious, encompassing a spectrum of definitions, ranging from academic interpretations of Is ...

in poor suburbs of large immigrant population, claiming they may be pressured into wearing veils

A veil is an article of clothing or hanging cloth that is intended to cover some part of the human head, head or face, or an object of some significance. Veiling has a long history in European, Asian, and African societies. The practice has be ...

, leaving school, and marrying early. On the other hand, a " third wave" of the feminist movement arose, combining the issues of sexism and racism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one Race (human categorization), race or ethnicity over another. It may also me ...

, protesting the perceived Islamophobic

Islamophobia is the irrational fear of, hostility towards, or hatred against the religion of Islam or Muslims in general. Islamophobia is primarily a form of religious or cultural bigotry; and people who harbour such sentiments often stereot ...

instrumentalization of feminism by the French Right.

After ''Ni Putes Ni Soumises'' activists were received by Prime Minister Jean Pierre Raffarin and their message incorporated into the official celebrations of Bastille Day

Bastille Day is the common name given in English-speaking countries to the national day of France, which is celebrated on 14 July each year. It is referred to, both legally and commonly, as () in French, though ''la fÊte nationale'' is also u ...

2003 in Paris, various left-wing

Left-wing politics describes the range of Ideology#Political ideologies, political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy either as a whole or of certain social ...

authors (Sylvie Tissot,Sylvie TissotBilan d'un fÃĐminisme d'Ãtat

in ''Plein Droit'' n°75, December 2007 Elsa Dorlin,Elsa Dorlin (professor of philosophy at the Sorbonne, member of NextGenderation)

"Pas en notre nom !" â Contre la rÃĐcupÃĐration raciste du fÃĐminisme par la droite française

(Not in our names! Against the Racist Recuperation of Feminism by the French Right), ''L'Autre Campagne''

Ãtienne Balibar

Ãtienne Balibar (; ; born 23 April 1942) is a French philosopher. He has taught at the University of Paris X, at the University of California, Irvine and is currently an Anniversary Chair Professor at the Centre for Research in Modern European ...

,Ãtienne Balibar

Ãtienne Balibar (; ; born 23 April 1942) is a French philosopher. He has taught at the University of Paris X, at the University of California, Irvine and is currently an Anniversary Chair Professor at the Centre for Research in Modern European ...

Uprising in the "banlieues"

Conference at the University of Chicago, 10 May 2006 (published in French in ''Lignes'', November 2006) Houria Bouteldja,Houria Bouteldja

De la cÃĐrÃĐmonie du dÃĐvoilement à Alger (1958) à Ni Putes Ni Soumises: l'instrumentalisation coloniale et nÃĐo-coloniale de la cause des femmes., Ni putes ni soumises, un appareil idÃĐologique d'Ãtat

June 2007 etc.) as well as NGOs such as ''Les BlÃĐdardes'' (led by Bouteldja), criticized the

racist

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one Race (human categorization), race or ethnicity over another. It may also me ...

stigmatization of immigrant populations, whose cultures are depicted as inherently sexist.

They underline that sexism is not a specificity of immigrant populations, as if French culture itself were devoid of sexism, and that the focus on media-friendly and violent acts (such as the burning of Sohane Benziane) silences the precarization of women. They frame the debate among the French Left

The French Left () refers to communist, socialist, social democratic

Social democracy is a Social philosophy, social, Economic ideology, economic, and political philosophy within socialism that supports Democracy, political and economic ...

concerning the 2004 law on secularity and conspicuous religious symbols in schools, mainly targeted against the ''hijab

Hijab (, ) refers to head coverings worn by Women in Islam, Muslim women. Similar to the mitpaáļĨat/tichel or Snood (headgear), snood worn by religious married Jewish women, certain Christian head covering, headcoverings worn by some Christian w ...

'', under this light.

They claimed that ''Ni Putes Ni Soumises'' overshadowed the work of other feminist NGOs. After the nomination of its leader Fadela Amara

Fadela Amara (born Fatiha Amara on 25 April 1964) is a French feminist and politician, who began her political life as an advocate for women in the impoverished ''banlieues''. She was the Secretary of State for Urban Policies in the liberal Un ...

to the government by Nicolas Sarkozy

Nicolas Paul StÃĐphane SarkÃķzy de Nagy-Bocsa ( ; ; born 28 January 1955) is a French politician who served as President of France from 2007 to 2012. In 2021, he was found guilty of having tried to bribe a judge in 2014 to obtain information ...

, Sylvie Tissot denounced a "state feminism" (an instrumentalization of feminism by state authorities) while Bouteldja qualified the NGO as an Ideological State Apparatus

"Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses (Notes Towards an Investigation)" ( French: "IdÃĐologie et appareils idÃĐologiques d'Ãtat (Notes pour une recherche)") is an essay by the French Marxist philosopher Louis Althusser. First published in ...

(AIE).

In January 2007, the collective of the ''FÃĐministes indigÃĻnes'' launched a manifesto in honour of the Mulatress Solitude. Solitude was a maroon heroine who fought with Louis DelgrÃĻs against the re-establishment of slavery (abolished during the French Revolution) by Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 â 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

. The manifesto stated that "Western Feminism did not have the monopoly of resistance against masculine domination" and supported a mild form of separatism

Separatism is the advocacy of cultural, ethnic, tribal, religious, racial, regional, governmental, or gender separation from the larger group. As with secession, separatism conventionally refers to full political separation. Groups simply seekin ...

, refusing to allow others (males or whites) to speak in their names.

Difficult access to government office for women

A few women held public office in the 1930s, although they kept a low profile. In 1936, the new Prime Minister,LÃĐon Blum

AndrÃĐ LÃĐon Blum (; 9 April 1872 â 30 March 1950) was a French socialist politician and three-time Prime Minister of France. As a Jew, he was heavily influenced by the Dreyfus affair of the late 19th century. He was a disciple of socialist l ...

, included three women in the Popular Front government: CÃĐcile Brunschvicg

CÃĐcile Brunschvicg (), born CÃĐcile Kahn (19 July 1877 in Enghien-les-Bains â 5 October 1946 in Neuilly-sur-Seine), was a French feminist politician. From the 1920s until her death she was regarded as "the ''grande dame'' of the feminist move ...

, Suzanne Lacore and IrÃĻne Joliot-Curie

IrÃĻne Joliot-Curie (; ; 12 September 1897 â 17 March 1956) was a French chemist and physicist who received the 1935 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with her husband, FrÃĐdÃĐric Joliot-Curie, for their discovery of induced radioactivity. They were ...

. The inclusion of women in the Popular Front government was unanimously appreciated: even the far-right candidate Xavier Vallat

Xavier Vallat (December 23, 1891 â January 6, 1972) was a French politician and antisemite who was Commissioner-General for Jewish Questions in the wartime collaborationist Vichy government, and was sentenced after World War II to ten years ...

addressed his "congratulations" to Blum for this measure while the conservative newspaper ''Le Temps

' (, ) is a Swiss French-language daily newspaper published in Berliner format in Geneva by Le Temps SA. The paper was launched in 1998, formed out of the merger of two other newspapers, and (the former being a merger of two other papers), ...

'' wrote, on 1 June 1936, that women could be ministers without previous authorizations from their husbands. CÃĐcile Brunschvicg and IrÃĻne Joliot-Curie were both legally "under-age" as women.

Wars (both World War I and World War II) had seen the provisional emancipation of some, individual, women, but post-war periods signalled the return to conservative roles. For instance, Lucie Aubrac

Lucie Samuel (29 June 1912 â 14 March 2007), born Bernard and known as Lucie Aubrac (), was a member of the French Resistance in World War II. A history teacher by occupation, she earned a history ''agrÃĐgation'' in 1938, a highly uncommon achi ...

, who was active in the French Resistance

The French Resistance ( ) was a collection of groups that fought the German military administration in occupied France during World War II, Nazi occupation and the Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy#France, collaborationist Vic ...

âa role highlighted by Gaullist

Gaullism ( ) is a French political stance based on the thought and action of World War II French Resistance leader Charles de Gaulle, who would become the founding President of the Fifth French Republic. De Gaulle withdrew French forces from t ...

mythsâreturned to private life after the war. Thirty-three women were elected at the Liberation, but none entered the government, and the euphoria of the Liberation was quickly halted.

Women retained a low profile during the Fourth and Fifth Republic. In 1949, Jeanne-Paule Sicard was the first female chief of staff, but was called "Mr. Pleven

Pleven ( ) is the seventh most populous city in Bulgaria. Located in the northern part of the country, it is the administrative centre of Pleven Province, as well as of the subordinate Pleven municipality. It is the biggest economic center in ...

's (then Minister of Defence

A ministry of defence or defense (see spelling differences), also known as a department of defence or defense, is the part of a government responsible for matters of defence and military forces, found in states where the government is divid ...

) secretary." Marie-France Garaud

Marie-France Garaud (; 6 March 1934 â 22 May 2024) was a French politician.

Life and career

Marie-France Garaud was a private adviser to President Pompidou and Jacques Chirac during his first time as Prime Minister. In the 1970s, she was con ...

, who entered Jean Foyer

Jean Foyer (21 April 1921, ContignÃĐ, Maine-et-Loire â 3 October 2008, Paris) was a French politician and minister. He studied law and became a law professor at the university. He wrote several books about French Civil law.

Political career ...

's office at the Ministry of Cooperation and would later become President Georges Pompidou's main counsellor, along with Pierre Juillet, was given the same title. The leftist newspaper ''LibÃĐration

(), popularly known as ''LibÃĐ'' (), is a daily newspaper in France, founded in Paris by Jean-Paul Sartre and Serge July in 1973 in the wake of the protest movements of May 1968 in France, May 1968. Initially positioned on the far left of Fr ...

'', founded in 1973 by Jean-Paul Sartre

Jean-Paul Charles Aymard Sartre (, ; ; 21 June 1905 â 15 April 1980) was a French philosopher, playwright, novelist, screenwriter, political activist, biographer, and literary criticism, literary critic, considered a leading figure in 20th ...

, would depict Marie-France Garaud as yet another figure of female spin-doctors. However, the new role granted to the President of the Republic

The President of the Republic is a title used for heads of state and/or heads of government in countries having republican form of government.

Designation

In most cases the president of a republic is elected, either:

* by direct universal s ...

in the semi-presidential regime of the Fifth Republic after the 1962 referendum on the election of the President at direct universal suffrage, led to a greater role of the "First Lady of France". Although Charles de Gaulle

Charles AndrÃĐ Joseph Marie de Gaulle (22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French general and statesman who led the Free France, Free French Forces against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government of the French Re ...

's wife Yvonne remained out of the public sphere, the image of Claude Pompidou

Claude Jacqueline Pompidou (nÃĐe Cahour; 13 November 1912 – 3 July 2007) was the wife of President of France Georges Pompidou. She was a philanthropist and a patron of modern art, especially through the Centre Georges Pompidou.

Life before ...

would interest the media more and more. The media frenzy surrounding CÃĐcilia Sarkozy, former wife of the former President Nicolas Sarkozy

Nicolas Paul StÃĐphane SarkÃķzy de Nagy-Bocsa ( ; ; born 28 January 1955) is a French politician who served as President of France from 2007 to 2012. In 2021, he was found guilty of having tried to bribe a judge in 2014 to obtain information ...

, would mark the culmination of this current.

1945â1974

Of the 27 cabinets formed during the Fourth Republic, only four included women, and never more than one at a time. SFIO member AndrÃĐe ViÃĐnot, widow of a Resistant, was nominated in June 1946 by theChristian democrat

Christian democracy is an ideology inspired by Christian ethics#Politics, Christian social teaching to respond to the challenges of contemporary society and politics.

Christian democracy has drawn mainly from Catholic social teaching and neo ...

Georges Bidault

Georges-Augustin Bidault (; 5 October 189927 January 1983) was a French politician. During World War II, he was active in the French Resistance. After the war, he served as foreign minister and premier on several occasions. He apparently joined ...

of the Popular Republican Movement

The Popular Republican Movement (, MRP) was a Christian-democratic political party in France during the Fourth Republic. Its base was the Catholic vote and its leaders included Georges Bidault, Robert Schuman, Paul Coste-Floret, Pierre-Henr ...

as undersecretary

Undersecretary (or under secretary) is a title for a person who works for and has a lower rank than a secretary (person in charge). It is used in the executive branch of government, with different meanings in different political systems, and is a ...

of Youth and Sports. However, she remained in office for only seven months. The next woman to hold government office, Germaine Poinso-Chapuis, was health and education minister from 24 November 1947 to 19 July 1948 in Robert Schuman

Jean-Baptiste Nicolas Robert Schuman (; 29 June 1886 – 4 September 1963) was a Luxembourg-born France, French statesman. Schuman was a Christian democrat, Christian democratic (Popular Republican Movement) political thinker and activist. ...

's cabinet. Remaining one year in office, her name remained attached to a decree

A decree is a law, legal proclamation, usually issued by a head of state, judge, monarch, royal figure, or other relevant Authority, authorities, according to certain procedures. These procedures are usually defined by the constitution, Legislativ ...

financing private education

A private school or independent school is a school not administered or funded by the government, unlike a public school. Private schools are schools that are not dependent upon national or local government to finance their financial endowme ...

. Published in the ''Journal officiel

A journal, from the Old French ''journal'' (meaning "daily"), may refer to:

*Bullet journal, a method of personal organization

*Diary, a record of personal secretive thoughts and as open book to personal therapy or used to feel connected to onesel ...

'' on 22 May 1948 with her signature, the decree had been drafted in her absence at the Council of Ministers of France

The Government of France (, ), officially the Government of the French Republic (, ), exercises executive power in France. It is composed of the prime minister, who is the head of government, as well as both senior and junior ministers.

Th ...

. The Communist and the Radical-Socialist Party called for the repealing of the decree, and finally, Schuman's cabinet was overturned after failing a confidence motion on the subject. Germaine Poinso-Chapuis did not pursue her political career, encouraged to abandon it by Pope Pius XII

Pope Pius XII (; born Eugenio Maria Giuseppe Giovanni Pacelli; 2 March 18769 October 1958) was the head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 2 March 1939 until his death on 9 October 1958. He is the most recent p ...

.

The third woman to hold government office would be the Radical-Socialist Jacqueline Thome-PatenÃītre, appointed undersecretary of Reconstruction and Lodging in Maurice BourgÃĻs-Maunoury

Maurice BourgÃĻs-Maunoury (19 August 1914 â 10 February 1993) was a French statesman and a member of the Companions of the Liberation. He served as President of the Council of Ministers (Prime Minister) under the Fourth French Republic.

...

's cabinet in 1957. Nafissa Sid Cara then participated in the government as undersecretary in charge of Algeria

Algeria, officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered to AlgeriaâTunisia border, the northeast by Tunisia; to AlgeriaâLibya border, the east by Libya; to Alger ...

from 1959 till the end of the war in 1962. Marie-Madeleine Dienesch, who evolved from Christian-Democracy to Gaullism (in 1966), occupied various offices as undersecretary between 1968 and 1974. Finally, Suzanne Ploux was undersecretary for the Minister of National Education in 1973 and 1974. In total, only seven women acceded to governmental offices between 1946 and 1974, and only one as minister. Historians explain this rarity by underlining the specific context of the ''Trente Glorieuses

''Les Trente Glorieuses'' (; 'The Thirty Glorious (Years)') was a thirty-year period of economic growth in France between 1945 and 1975, following the end of the Second World War. The name was first used by the French demographer Jean Fourast ...

'' (Thirty Glorious Years) and of the baby boom, leading to a strengthening of familialism

Familialism or familism is a philosophy that puts priority to family. The term ''familialism'' has been specifically used for advocating a welfare system wherein it is presumed that families will take responsibility for the care of their memb ...

and patriarchy

Patriarchy is a social system in which positions of authority are primarily held by men. The term ''patriarchy'' is used both in anthropology to describe a family or clan controlled by the father or eldest male or group of males, and in fem ...

.

Even left-wing cabinets abstained from nominating women: Pierre MendÃĻs-France

Pierre is a masculine given name. It is a French language, French form of the name Peter (given name), Peter. Pierre originally meant "rock" or "stone" in French (derived from the Greek word ÏÎÏÏÎŋÏ (''petros'') meaning "stone, rock", via ...

(advised by Colette Baudry) did not include any woman in his cabinet, neither did Guy Mollet

Guy Alcide Mollet (; 31 December 1905 â 3 October 1975) was a French politician. He led the socialist French Section of the Workers' International (SFIO) from 1946 to 1969 and was the French Prime Minister from 1956 to 1957.

As Prime Ministe ...

, the secretary general of the SFIO, nor the centrist Antoine Pinay

Antoine Pinay (; 30 December 1891 â 13 December 1994) was a French conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of France from 1952 to 1953 and French Foreign Minister from 1955 to 1956.

Life

Antoine Pinay was born on 30 December 1891 ...

. Although the ''Ãcole nationale d'administration

The (; ENA; ) was a French ''grande ÃĐcole'', created in 1945 by the then Provisional Government of the French Republic, provisional chief of government Charles de Gaulle and principal co-author of the Constitution of France, 1958 Constitution M ...

'' (ENA) elite administrative school (from which a lot of French politicians graduate) became gender-mixed in 1945, only 18 women graduated from it between 1946 and 1956 (compared to 706 men).

Of the first eleven cabinets of the Fifth Republic, four did not count any women. In May 1968, the cabinet was exclusively male. This low representation of women was not, however, specific to France: West Germany

West Germany was the common English name for the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) from its formation on 23 May 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with East Germany on 3 October 1990. It is sometimes known as the Bonn Republi ...

's government did not include any women in any office from 1949 to 1961, and in 1974â1975, only 12 countries in the world had female ministers. The British government had exclusively male ministers.

1974â1981

In 1974,ValÃĐry Giscard d'Estaing

ValÃĐry RenÃĐ Marie Georges Giscard d'Estaing (, ; ; 2 February 19262 December 2020), also known as simply Giscard or VGE, was a French politician who served as President of France from 1974 to 1981.

After serving as Ministry of the Economy ...

was elected President, and nominated 9 women in his government between 1974 and 1981: Simone Veil

Simone Veil (; ; 13 July 1927 â 30 June 2017) was a French magistrate, Holocaust survivor, and politician who served as health minister in several governments and was President of the European Parliament from 1979 to 1982, the first woman t ...

, the first female minister, Françoise Giroud

Françoise Giroud (born Lea France Gourdji; 21 September 1916 â 19 January 2003), was a French journalist, screenwriter, writer, and politician.

Biography

Giroud was born in Lausanne, Switzerland to immigrant Sephardi Turkish Jewish parents; ...

, named Minister of the Feminine Condition, HÃĐlÃĻne Dorlhac, Alice Saunier-SeitÃĐ

Alice Louise Saunier-SeÃŊtÃĐ (26 April 1925 â 4 August 2003) was a French geographer, historian, university professor and politician of the Parti RÃĐpublicain. She was a State Secretary and the first female minister for universities, serving fro ...

, Annie Lesur and Christiane Scrivener

Christiane Scrivener (nÃĐe Fries; 1 September 1925 â 8 April 2024) was a French politician who was a member of ValÃĐry Giscard d'Estaing's Republican Party (now replaced by Alain Madelin's Liberal Democracy

Liberal democracy, also called ...

, Nicole Pasquier, Monique Pelletier

Monique Pelletier (born July 12, 1969) is an American former alpine skier who competed in the 1992 Winter Olympics and 1994 Winter Olympics

The 1994 Winter Olympics, officially known as the XVII Olympic Winter Games (; ) and commonly known ...

and HÃĐlÃĻne Missoffe. At the end of the 1970s, France was one of the leading countries in the world with respect to the number of female ministers, just behind Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. It borders Norway to the west and north, and Finland to the east. At , Sweden is the largest Nordic count ...

. However, they remained highly under-represented in the National Assembly

In politics, a national assembly is either a unicameral legislature, the lower house of a bicameral legislature, or both houses of a bicameral legislature together. In the English language it generally means "an assembly composed of the repr ...

. There were only 14 female deputies (1.8%) in 1973 and 22 (2.8%) in 1978. Janine Alexandre-Derbay, 67-year-old senator of the Republican Party (PR), initiated a hunger strike

A hunger strike is a method of non-violent resistance where participants fasting, fast as an act of political protest, usually with the objective of achieving a specific goal, such as a policy change. Hunger strikers that do not take fluids are ...

to protest against the complete absence of women on the governmental majority's electoral lists in Paris.