Free Soil on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Free Soil Party, also called the Free Democratic Party or the Free Democracy, was a political party in the United States from 1848 to 1854, when it merged into the Republican Party. The party was focused on opposing the expansion of

Following the annexation of Texas in 1845, President Polk began preparations for a potential war with

Following the annexation of Texas in 1845, President Polk began preparations for a potential war with

Led by John Van Buren, the Barnburners bolted from the 1848 Democratic National Convention after the party nominated a ticket consisting of Senator Lewis Cass of Michigan and former Representative William O. Butler of Kentucky; Cass and Butler had both opposed the Wilmot Proviso. Shortly after the Democrats nominated Cass, a group of Whigs made plans for a convention of anti-slavery politicians and activists in case the 1848 Whig National Convention nominated General

Led by John Van Buren, the Barnburners bolted from the 1848 Democratic National Convention after the party nominated a ticket consisting of Senator Lewis Cass of Michigan and former Representative William O. Butler of Kentucky; Cass and Butler had both opposed the Wilmot Proviso. Shortly after the Democrats nominated Cass, a group of Whigs made plans for a convention of anti-slavery politicians and activists in case the 1848 Whig National Convention nominated General

Hoping to spur the creation of a

Hoping to spur the creation of a

online

* * * *

''Free Soil Banner''

– Indianapolis Free Soil newspaper that ran from 1848 to 1854; digitized by the Indianapolis Marion County Public Library

American Abolitionists and Antislavery Activists

– comprehensive list of abolitionist and anti-slavery activists and organizations in the United States, including the Free Soil Party * {{Authority control 1848 establishments in the United States 1854 disestablishments in the United States American abolitionist organizations Defunct political parties in the United States Political parties disestablished in 1854 Political parties established in 1848 Slavery in the United States Martin Van Buren Henry Wilson Wikipedia articles containing unlinked shortened footnotes

slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

into the western territories of the United States

Territories of the United States are sub-national administrative divisions and dependent territory, dependent territories overseen by the federal government of the United States. The American territories differ from the U.S. states and Indi ...

. The 1848 presidential election took place in the aftermath of the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War (Spanish language, Spanish: ''guerra de Estados Unidos-México, guerra mexicano-estadounidense''), also known in the United States as the Mexican War, and in Mexico as the United States intervention in Mexico, ...

and debates over the extension of slavery into the Mexican Cession

The Mexican Cession () is the region in the modern-day Western United States that Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United S ...

. After the Whig Party and the Democratic Party nominated presidential candidates who were unwilling to rule out the extension of slavery into the Mexican Cession, anti-slavery Democrats and Whigs joined with members of the Liberty Party (an abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was Kingdom of France, France in 1315, but it was later used ...

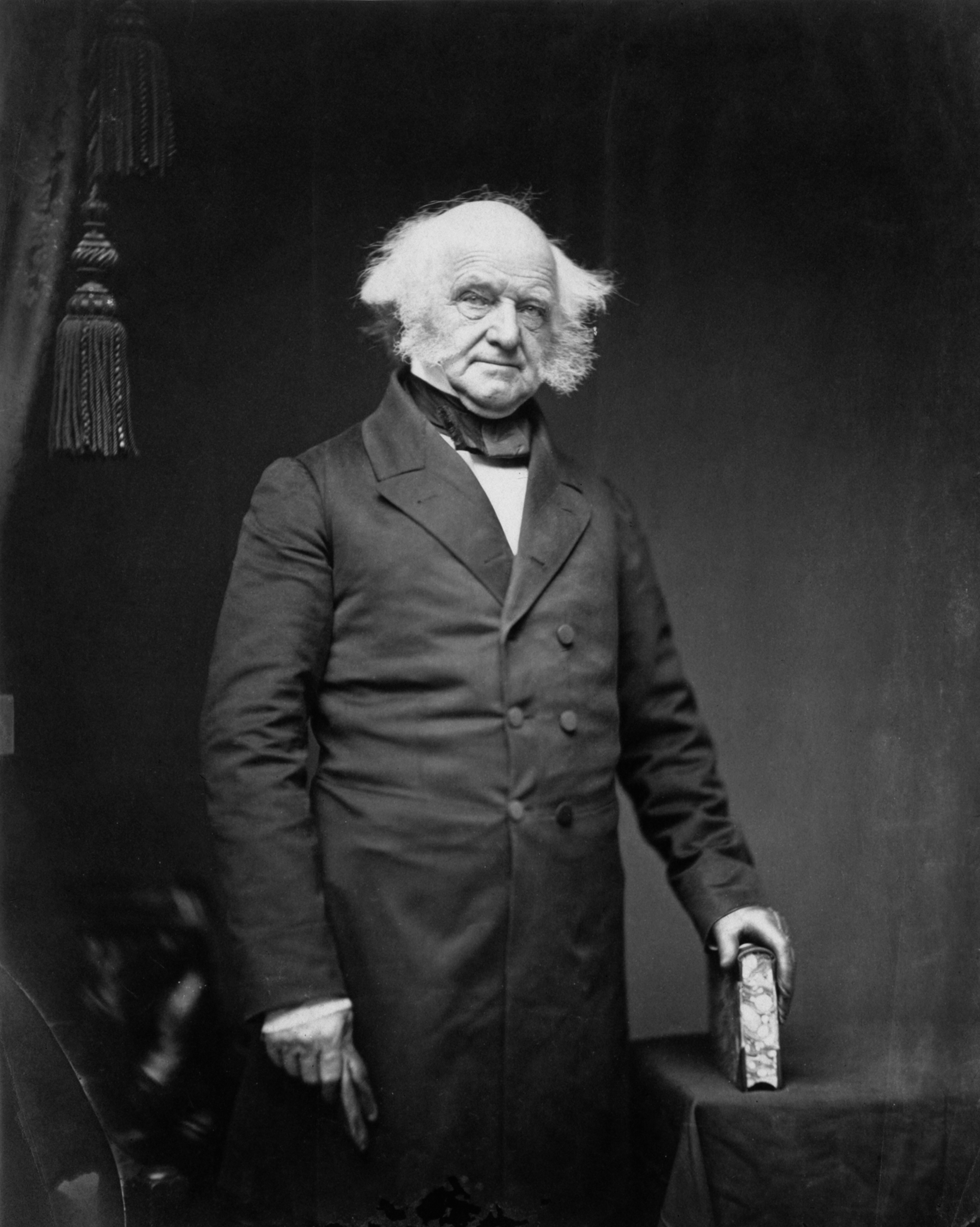

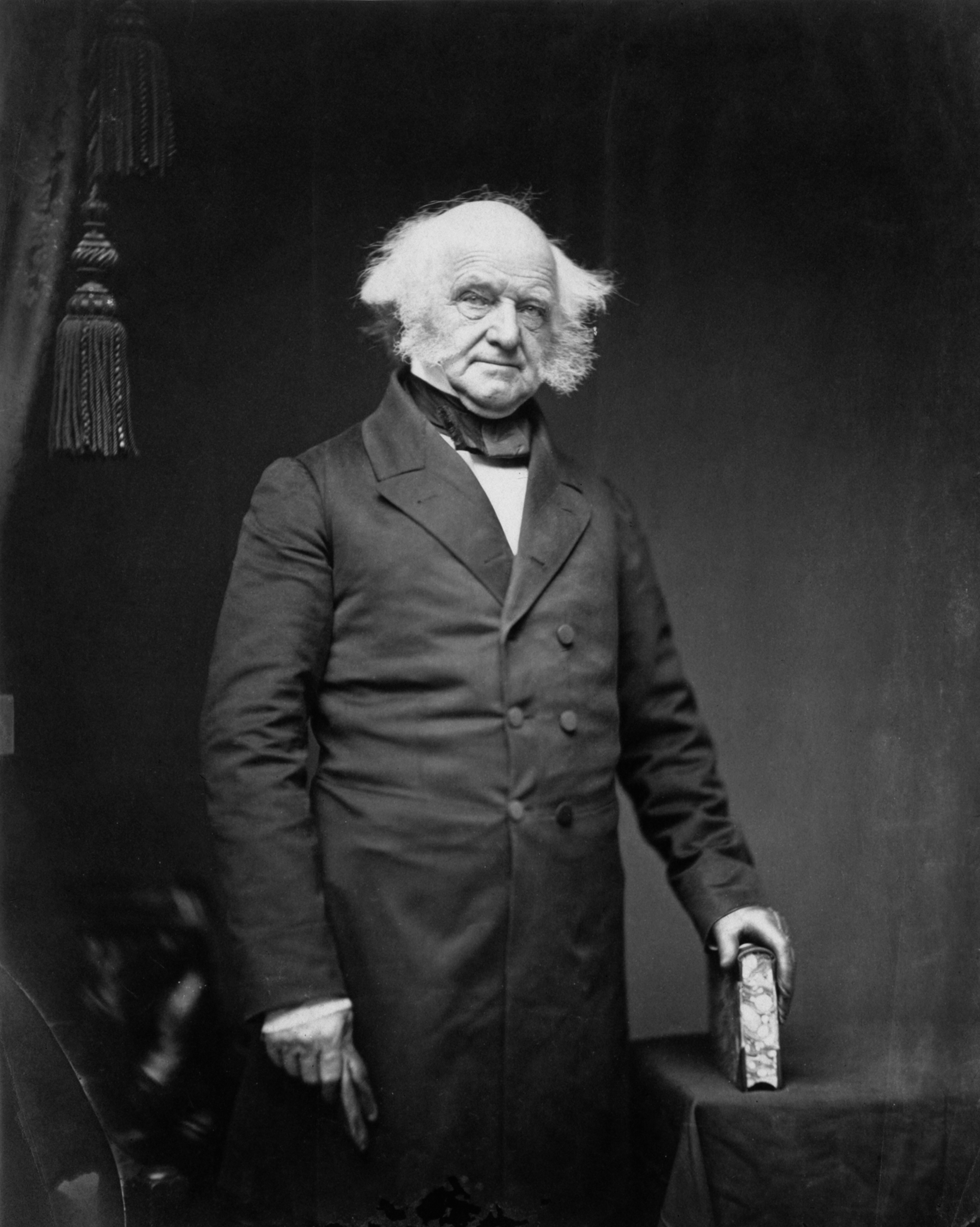

political party) to form the new Free Soil Party. Running as the Free Soil presidential candidate, former President Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was the eighth president of the United States, serving from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he served as Attorney General o ...

won 10.1 percent of the popular vote, the strongest popular vote performance by a third party up to that point in U.S. history.

Though Van Buren and many other Free Soil supporters rejoined the Democrats or the Whigs after the 1848 election, Free Soilers retained a presence in Congress over the next six years. Led by Salmon P. Chase of Ohio, John P. Hale of New Hampshire, and Charles Sumner

Charles Sumner (January 6, 1811March 11, 1874) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented Massachusetts in the United States Senate from 1851 until his death in 1874. Before and during the American Civil War, he was a leading American ...

of Massachusetts, the Free Soilers strongly opposed the Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that temporarily defused tensions between slave and free states during the years leading up to the American Civil War. Designe ...

, which temporarily settled the issue of slavery in the Mexican Cession. Hale ran as the party's presidential candidate in the 1852 presidential election, taking just under five percent of the vote. The 1854 Kansas–Nebraska Act repealed the long-standing Missouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise (also known as the Compromise of 1820) was federal legislation of the United States that balanced the desires of northern states to prevent the expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand ...

and outraged many Northerners, contributing to the collapse of the Whigs and spurring the creation of a new, broad-based anti-slavery Republican Party. Most Free Soilers joined the Republican Party, which emerged as the dominant political party in the United States in the Third Party System (1856–1894).

History

Background

ThoughWilliam Lloyd Garrison

William Lloyd Garrison (December , 1805 – May 24, 1879) was an Abolitionism in the United States, American abolitionist, journalist, and reformism (historical), social reformer. He is best known for his widely read anti-slavery newspaper ''The ...

and most other abolitionists of the 1830s had generally shunned the political system, a small group of abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was Kingdom of France, France in 1315, but it was later used ...

s founded the Liberty Party in 1840. The Liberty Party was a third party dedicated to the immediate abolition of slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

. The Liberty Party nominated James G. Birney for president and Thomas Earle for vice president in the 1840 presidential election. Months after the 1840 election, the party re-nominated Birney for president, established a national party committee, and began to organize at the state and local level. Support for the party grew in the North, especially among evangelical

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide, interdenominational movement within Protestantism, Protestant Christianity that emphasizes evangelism, or the preaching and spreading of th ...

former Whigs in New England, upstate New York, Michigan, and Ohio's Western Reserve. Other anti-slavery Whigs like John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was the sixth president of the United States, serving from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States secretary of state from 1817 to 1825. During his long diploma ...

remained within the Whig Party, but increasingly supported anti-slavery policies like the repeal of the gag rule, which prevented the House of Representatives from considering abolitionist petitions. Meanwhile, long-time abolitionist leaders like Lewis Tappan became increasingly open to working within the political system. In a reflection of the rise of anti-slavery sentiment, several Northern states passed personal liberty laws that forbid state authorities from cooperating in the capture and return of fugitive slaves.

Beginning in May 1843, President John Tyler

John Tyler (March 29, 1790 – January 18, 1862) was the tenth president of the United States, serving from 1841 to 1845, after briefly holding office as the tenth vice president of the United States, vice president in 1841. He was elected ...

made the annexation of Texas his key priority. Most leaders of both parties opposed opening the question of annexation in 1843 due to their fear of stoking the debate over slavery; the annexation of Texas was widely viewed as a pro-slavery initiative because it would add another slave state to the union. Nonetheless, in April 1844, Secretary of State John C. Calhoun reached a treaty with Texas providing for the annexation of that country. Henry Clay

Henry Clay (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the United States Senate, U.S. Senate and United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives. He was the seventh Spea ...

and Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was the eighth president of the United States, serving from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he served as Attorney General o ...

, the two front-runners for the major party presidential nominations in the 1844 presidential election, both announced their opposition to annexation, and the Senate blocked the treaty. To the surprise of Clay and other Whigs, the 1844 Democratic National Convention rejected Van Buren in favor of James K. Polk, and approved a platform calling for the acquisition of both Texas and Oregon Country

Oregon Country was a large region of the Pacific Northwest of North America that was subject to a long Oregon boundary dispute, dispute between the United Kingdom and the United States in the early 19th century. The area, which had been demarcat ...

. Polk went on to defeat Clay in a close election, taking 49.5 of the popular vote and a majority of the electoral vote. The number of voters casting a ballot for Birney increased tenfold from 6,200 in 1840 (0.3 percent of popular vote) to 62,000 (2.3 percent of the popular vote) in 1844.

Formation of the Free Soil Party

Wilmot Proviso

Following the annexation of Texas in 1845, President Polk began preparations for a potential war with

Following the annexation of Texas in 1845, President Polk began preparations for a potential war with Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

, which still regarded Texas as a part of its republic.Merry (2009), pp. 188–189. After a skirmish known as the Thornton Affair broke out on the northern side of the Rio Grande,Merry (2009), pp. 240–242. Polk convinced Congress to declare war against Mexico.Merry (2009), pp. 244–245. Though most Democrats and Whigs initially supported the war, Adams and some other anti-slavery Whigs attacked the war as a " Slave Power" plot designed to expand slavery across North America. Meanwhile, former Democratic Representative John P. Hale had defied party leaders by denouncing the annexation of Texas, causing him to lose re-election in 1845. Hale joined with anti-slavery Whigs and the Liberty Party to create a new party in New Hampshire, and he won election to the Senate in early 1847. In New York, tensions between the anti-slavery Barnburner and the conservative Hunker factions of the Democratic Party rose, as the Hunkers allied with the Whigs to defeat the re-election campaign of Democratic Governor Silas Wright.

In August 1846, Polk asked Congress to appropriate $2 million (~$ in ) in hopes of using that money as a down payment for the purchase of Alta California

Alta California (, ), also known as Nueva California () among other names, was a province of New Spain formally established in 1804. Along with the Baja California peninsula, it had previously comprised the province of , but was made a separat ...

in a treaty with Mexico.Merry (2009), pp. 283–285. During the debate over the appropriations bill, Democratic Representative David Wilmot of Pennsylvania offered an amendment known as the Wilmot Proviso, which would ban slavery in any newly acquired lands.Merry (2009), pp. 286–289. Though broadly supportive of the war, Wilmot and some other anti-slavery Northern Democrats had increasingly come to view Polk as unduly favorable to Southern interests, partly due to Polk's decision to compromise with Britain over the partition of Oregon. Unlike some Northern Whigs, Wilmot and other anti-slavery Democrats were largely unconcerned by the issue of racial equality, and instead opposed the expansion of slavery because they believed the institution was detrimental to the "laboring white man." The Wilmot Proviso passed the House with the support of both Northern Whigs and Northern Democrats, breaking the normal pattern of partisan division in congressional votes, but it was defeated in the Senate, where Southerners controlled a proportionally higher share of seats. Several Northern congressmen subsequently defeated an attempt by President Polk and Senator Lewis Cass

Lewis Cass (October 9, 1782June 17, 1866) was a United States Army officer and politician. He represented Michigan in the United States Senate and served in the Cabinets of two U.S. Presidents, Andrew Jackson and James Buchanan. He was also the 1 ...

to extend the Missouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise (also known as the Compromise of 1820) was federal legislation of the United States that balanced the desires of northern states to prevent the expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand ...

line to the Pacific.

In February 1848, Mexican and U.S. negotiators reached the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo officially ended the Mexican–American War (1846–1848). It was signed on 2 February 1848 in the town of Villa de Guadalupe, Mexico City, Guadalupe Hidalgo.

After the defeat of its army and the fall of the cap ...

, which provided for the cession of Alta California and New Mexico.Merry (2009), pp. 424–426. Though many senators had reservations about the treaty, the Senate approved it in a 38-to-14 vote in February 1848. Senator John M. Clayton's effort to reach a compromise over the status of slavery in the territories was defeated in the House, ensuring that slavery would be an important issue in the 1848 election.

Election of 1848

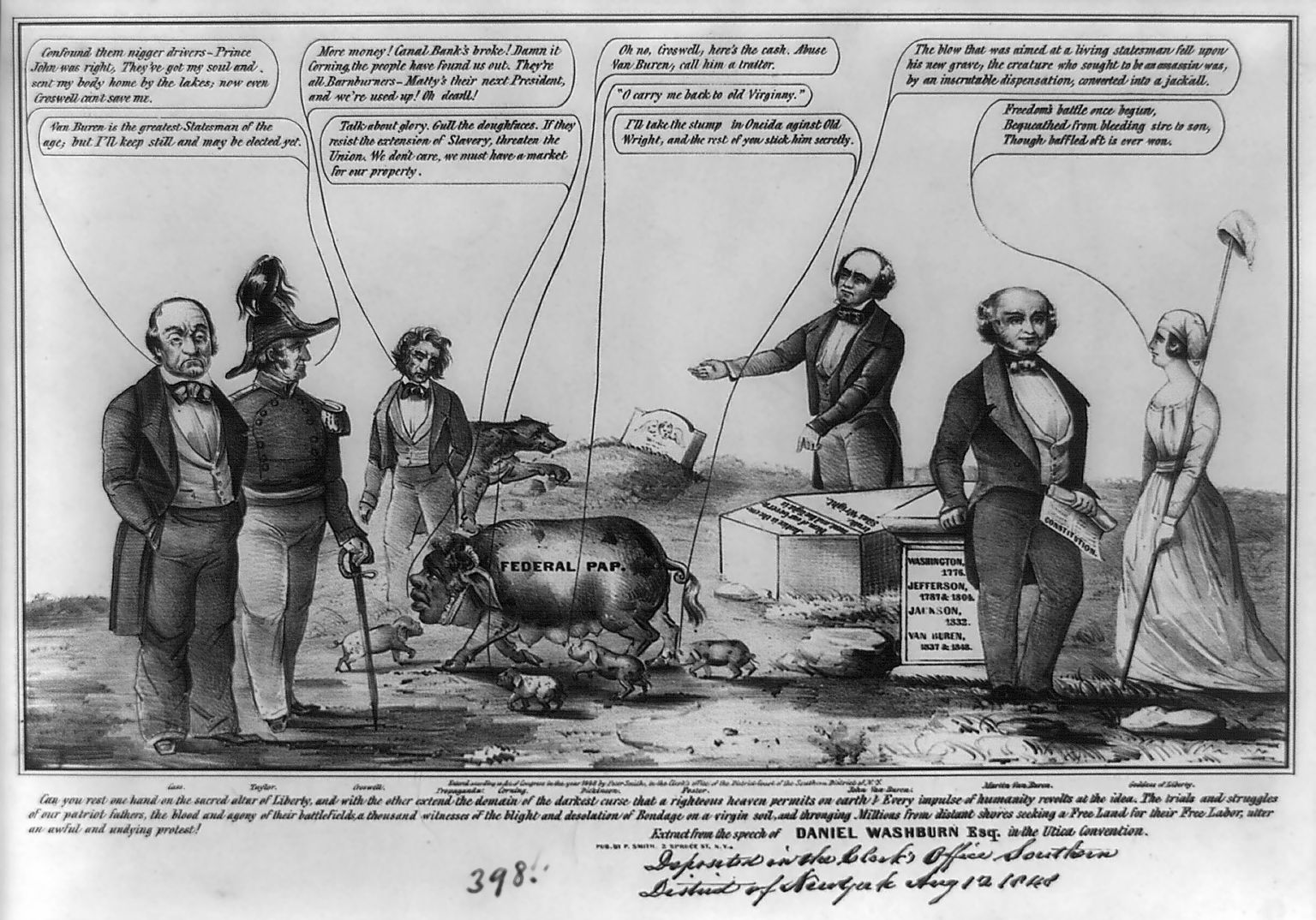

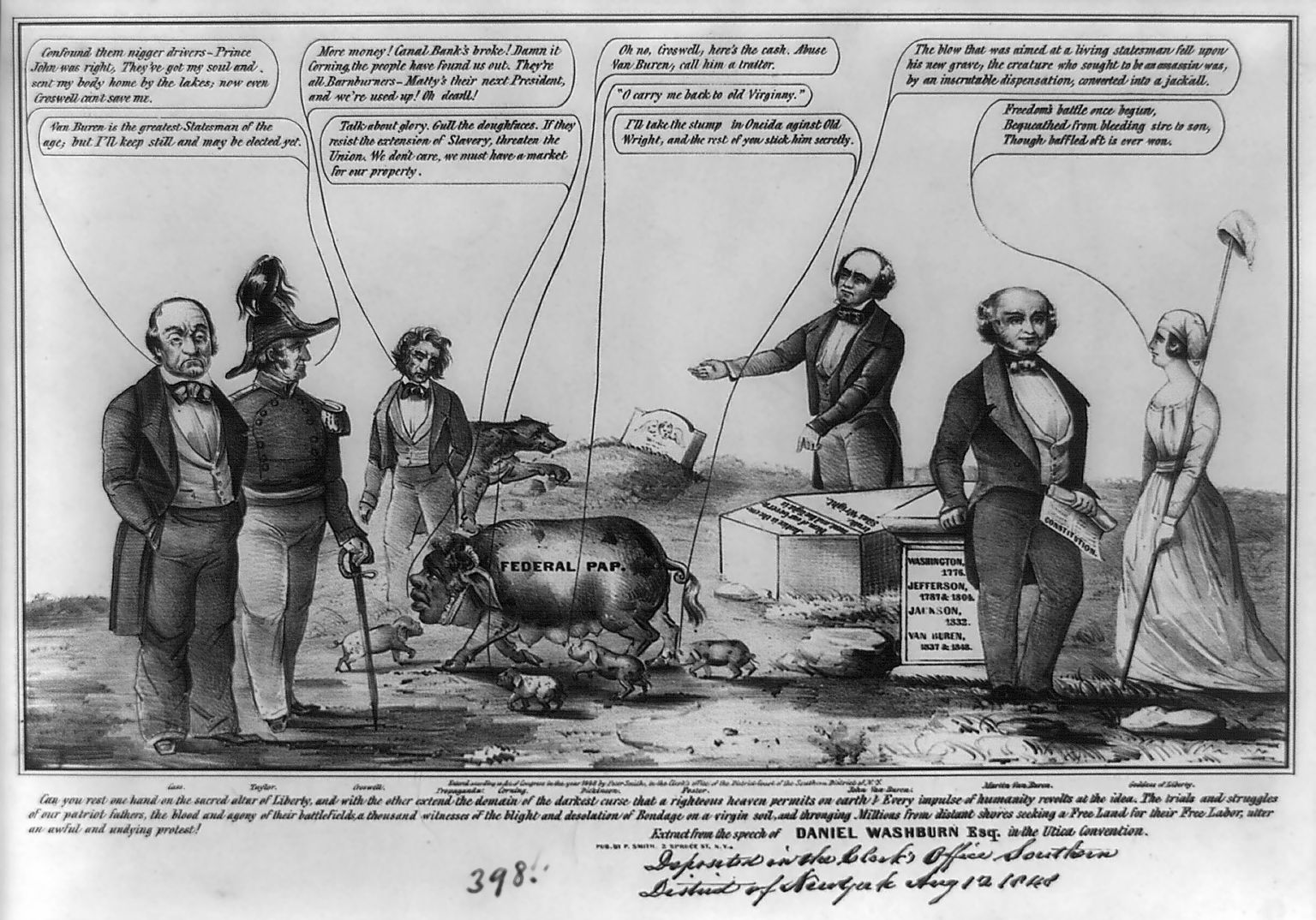

Led by John Van Buren, the Barnburners bolted from the 1848 Democratic National Convention after the party nominated a ticket consisting of Senator Lewis Cass of Michigan and former Representative William O. Butler of Kentucky; Cass and Butler had both opposed the Wilmot Proviso. Shortly after the Democrats nominated Cass, a group of Whigs made plans for a convention of anti-slavery politicians and activists in case the 1848 Whig National Convention nominated General

Led by John Van Buren, the Barnburners bolted from the 1848 Democratic National Convention after the party nominated a ticket consisting of Senator Lewis Cass of Michigan and former Representative William O. Butler of Kentucky; Cass and Butler had both opposed the Wilmot Proviso. Shortly after the Democrats nominated Cass, a group of Whigs made plans for a convention of anti-slavery politicians and activists in case the 1848 Whig National Convention nominated General Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was an American military officer and politician who was the 12th president of the United States, serving from 1849 until his death in 1850. Taylor was a career officer in the United States ...

of Louisiana for president. With the strong backing of slave state delegates, Taylor defeated Henry Clay to win the Whig presidential nomination. For vice president, the Whigs nominated Millard Fillmore of New York, a conservative Northerner. The nomination of Taylor, a slaveholder without any history in the Whig Party, spurred anti-slavery Whigs to go through with their convention, which would meet in Buffalo, New York

Buffalo is a Administrative divisions of New York (state), city in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York and county seat of Erie County, New York, Erie County. It lies in Western New York at the eastern end of Lake Erie, at the head of ...

, in August. A faction of the Liberty Party led by Salmon P. Chase agreed to attend the convention, though another faction of the party, led by Gerrit Smith, refused to consider merging with another party.

Meanwhile, Barnburners convened in Utica, New York

Utica () is the county seat of Oneida County, New York, United States. The tenth-most populous city in New York, its population was 65,283 in the 2020 census. It is located on the Mohawk River in the Mohawk Valley at the foot of the Adiro ...

, on June 22; they were joined by a smaller number of Whigs and Democrats from outside New York. Though initially reluctant to accept to run for president, former President Van Buren accepted the group's presidential nomination. Van Buren endorsed the position that slavery should be excluded from the territories acquired from Mexico, further declaring his belief that slavery was inconsistent with the "principles of the Revolution

In political science, a revolution (, 'a turn around') is a rapid, fundamental transformation of a society's class, state, ethnic or religious structures. According to sociologist Jack Goldstone, all revolutions contain "a common set of elements ...

". Because Van Buren had favored the gag rule and had generally accommodated pro-slavery leaders during his presidency, many Liberty Party leaders and anti-slavery Whigs were unconvinced as to the sincerity of Van Buren's anti-slavery beliefs. Historian A. James Reichley writes that, while resentment stemming from his defeat at the 1844 Democratic National Convention may have played a role in his candidacy, Van Buren ran on the grounds that "the long-term welfare of he Democratic Party and the nation, required that the emocratic Partyshed its Calhounite influence, even at the cost of losing an election or two."

With mix of Democratic, Whig, and Liberty Party attendees, the National Free Soil Convention convened in Buffalo early August. Anti-slavery leaders made up a majority of the attendees, but the convention also attracted some Democrats and Whigs who were indifferent on the issue of slavery but disliked the nominee of their respective party. Salmon Chase, Preston King, and Benjamin Franklin Butler

Benjamin Franklin Butler (November 5, 1818 – January 11, 1893) was an American major general of the Union Army, politician, lawyer, and businessman from Massachusetts. Born in New Hampshire and raised in Lowell, Massachusetts, Butler was a ...

led the drafting of a platform that not only endorsed the Wilmot Proviso but also called for the abolition of slavery in Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

, and all U.S. territories. With the backing of most Democratic delegates, about half of the Whig delegates, and a small number of Liberty Party leaders, Van Buren defeated John P. Hale to win the fledgling party's presidential nomination. For vice president, the Free Soil Party nominated Charles Francis Adams Sr., the youngest son of the recently deceased John Quincy Adams.

Some Free Soil leaders were initially optimistic that Van Buren could carry a handful of Northern states and force a contingent election

In the United States, a contingent election is used to elect the president or vice president if no candidate receives a majority of the whole number of electors appointed. A presidential contingent election is decided by a special vote of th ...

in the House of Representatives, but Van Buren did not win a single electoral vote. However, the nomination of Van Buren alienated many Whigs; except in northern Ohio, most Whig leaders and newspapers rallied around Taylor's candidacy. Ultimately, Taylor won the election with a majority of the electoral vote and a plurality of the popular vote, improving on Clay's 1844 performance in the South and benefiting from the defection of many Democrats to Van Buren in the North. Van Buren won ten percent of the national popular vote and fifteen percent of the popular vote in the Northern states; he received a popular vote total five times greater than that of Birney's 1844 candidacy.Wilentz (2005) pp. 628–631 Van Buren was the first third-party candidate in U.S. history to win at least ten percent of the national popular vote. In concurrent congressional elections, Salmon Chase won election to the Senate and about a dozen Free Soil candidates won election to the House of Representatives.

Between elections, 1849–1852

The Free Soil Party continued to exist after 1848, fielding candidates for various offices. At the state level, Free Soilers often entered into coalition with either of the major parties to elect anti-slavery officeholders. To sidestep the issue of the Wilmot Proviso, the Taylor administration proposed that the lands of the Mexican Cession be admitted as states without first organizing territorial governments; thus, slavery in the area would be left to the discretion of state governments rather than the federal government. In January 1850, Senator Clay introduced a separate proposal which included the admission of California as a free state, the cession by Texas of some of its northern and western territorial claims in return for debt relief, the establishment ofNew Mexico

New Mexico is a state in the Southwestern United States, Southwestern region of the United States. It is one of the Mountain States of the southern Rocky Mountains, sharing the Four Corners region with Utah, Colorado, and Arizona. It also ...

and Utah

Utah is a landlocked state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is one of the Four Corners states, sharing a border with Arizona, Colorado, and New Mexico. It also borders Wyoming to the northea ...

territories, a ban on the importation of slaves into the District of Columbia for sale, and a more stringent fugitive slave law. Free Soilers strongly opposed this proposal, focusing especially on the fugitive slave law

The fugitive slave laws were laws passed by the United States Congress in 1793 and 1850 to provide for the return of slaves who escaped from one state into another state or territory. The idea of the fugitive slave law was derived from the Fugi ...

.

Taylor died in July 1850 and was succeeded by Vice President Fillmore. Fillmore and Democrat Stephen A. Douglas

Stephen Arnold Douglas (né Douglass; April 23, 1813 – June 3, 1861) was an American politician and lawyer from Illinois. As a United States Senate, U.S. senator, he was one of two nominees of the badly split Democratic Party (United States) ...

led the passage of the Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that temporarily defused tensions between slave and free states during the years leading up to the American Civil War. Designe ...

, which was based on Clay's earlier proposal. The Whig Party became badly split between pro-Compromise Whigs like Fillmore and Webster and anti-Compromise Whigs like William Seward, who demanded the repeal of the Fugitive Slave Act. The first of several prominent episodes concerning the enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law occurred in late 1850, when Boston abolitionists helped Ellen and William Craft, two fugitive slaves, escape to Canada.

Though the fugitive slave act and its enforcement outraged anti-slavery activists, most Northerners viewed it as a necessary trade-off for sectional peace with the South, and there was a backlash in the North against the anti-slavery agitation. The Free Soil Party suffered from this backlash, as well as the desertion of many anti-slavery Democrats (including Van Buren himself), many of whom believed that sectional balance had been restored following Van Buren's candidacy and the Compromise of 1850. Charles Sumner

Charles Sumner (January 6, 1811March 11, 1874) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented Massachusetts in the United States Senate from 1851 until his death in 1874. Before and during the American Civil War, he was a leading American ...

won election to the 32nd Congress, but Free Soilers lost a net of five seats in the 1850 and 1851 House of Representatives elections. As the 1852 presidential election approached, Free Soilers cast about for a candidate. Potential candidates with national stature like Van Buren and Senator Thomas Hart Benton declined to run, while Supreme Court Justice Levi Woodbury, another subject of speculation as a potential Free Soil candidate, died in 1851.Wilentz (2005) pp. 659–660

1852 presidential election

Enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act damaged Fillmore's standing among Northerners and, with the backing of Senator Seward, GeneralWinfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as Commanding General of the United States Army from 1841 to 1861, and was a veteran of the War of 1812, American Indian Wars, Mexica ...

won the presidential nomination at the 1852 Whig National Convention. The Whig national convention also adopted a platform that endorsed the Compromise of 1850 and the Fugitive Slave Act. Scott and his advisers had initially hoped to avoid openly endorsing the Compromise of 1850 in order to court Free Soil support, but, as a concession to Southern Whigs, Scott agreed to support the Whig platform. The 1852 Democratic National Convention, meanwhile, nominated former New Hampshire senator Franklin Pierce

Franklin Pierce (November 23, 1804October 8, 1869) was the 14th president of the United States, serving from 1853 to 1857. A northern Democratic Party (United States), Democrat who believed that the Abolitionism in the United States, abolitio ...

, a Northerner sympathetic to the Southern view on slavery. Free Soil leaders had initially considered supporting Scott, but they organized a national convention after Scott accepted the pro-Compromise Whig platform.

At the August 1852 Free Soil Convention, held in Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, United States, and its county seat. It is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania#Municipalities, second-most populous city in Pennsylvania (after Philadelphia) and the List of Un ...

, the party nominated a ticket consisting of Senator John P. Hale of New Hampshire and former Representative George Washington Julian of Indiana. The party adopted a platform that called for the repeal of the Fugitive Slave Act and described slavery as "a sin against God and a crime against man."Wilentz (2005) pp. 663–664 Free Soil leaders strongly preferred Scott to Pierce, and Hale focused his campaign on winning over anti-slavery Democratic voters. The elections proved to be disastrous for the Whig Party, as Scott was defeated by a wide margin and the Whigs lost several congressional and state elections. Hale won just under five percent of the vote, performing most strongly in Massachusetts, Vermont, and Wisconsin. Though much of this drop in support was caused by the return of Barnburners to the Democratic Party, many individuals who had voted for Van Buren in 1848 sat out the 1852 election. In the aftermath of the decisive defeat of the Whigs, many Free Soil leaders predicted an impending realignment that would result in the formation of a larger anti-slavery party that would unite Free Soilers with anti-slavery Whigs and Democrats.

Formation of the Republican Party

Hoping to spur the creation of a

Hoping to spur the creation of a transcontinental railroad

A transcontinental railroad or transcontinental railway is contiguous rail transport, railroad trackage that crosses a continent, continental land mass and has terminals at different oceans or continental borders. Such networks may be via the Ra ...

, in 1853 Senator Douglas proposed a bill to create an organized territorial government in a portion of the Louisiana Purchase that was north of the 36°30′ parallel, and thus excluded slavery under the terms of the Missouri Compromise. After pro-slavery Southern senators blocked the passage of the proposal, Douglas and other Democratic leaders agreed to a bill that would repeal the Missouri Compromise and allow the inhabitants of the territories to determine the status of slavery. In response, Free Soilers issued the ''Appeal of the Independent Democrats The Appeal of the Independent Democrats (the full title was "Appeal of the Independent Democrats in Congress to the People of the United States") was a manifesto issued in January 1854, in response to the introduction into the United States Senate o ...

'', a manifesto that attacked the bill as the work of the Slave Power. Overcoming the opposition of Free Soilers, Northern Whigs, and many Democrats, the Kansas–Nebraska Act was passed into law in May 1854. The act deeply angered many Northerners, including anti-slavery Democrats and conservative Whigs who were largely apathetic towards slavery but were upset by the repeal of a thirty-year-old compromise. Pierce's forceful response to protests stemming from the capture of escaped slave Anthony Burns further alienated many Northerners.

Throughout 1854, Democrats, Whigs, and Free Soilers held state and local conventions, where they denounced the Kansas–Nebraska Act. Many of the larger conventions agreed to nominate a fusion ticket of candidate opposed to the Kansas–Nebraska Act, and some adopted portions of the Free Soil platform from 1848 and 1852. One of these groups met in Ripon, Wisconsin

Ripon () is a city in Fond du Lac County, Wisconsin, United States. The population was 7,863 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. The city is surrounded by the Ripon (town), Wisconsin, Town of Ripon.

Ripon is home to the Little White S ...

, and agreed to establish a new party known as the Republican Party if the Kansas–Nebraska Act passed. Though many Democrats and Whigs involved in the anti-Nebraska movement still clung to their partisan affiliation, others began to label themselves as Republicans. Another political coalition appeared in the form of the nativist and anti-Catholic Know Nothing

The American Party, known as the Native American Party before 1855 and colloquially referred to as the Know Nothings, or the Know Nothing Party, was an Old Stock Americans, Old Stock Nativism in United States politics, nativist political movem ...

movement, which formed the American Party. While the Republican Party almost exclusively appealed to Northerners, the Know Nothings gathered many adherents in both the North and South; some individuals joined both groups even while they remained part of the Whig Party or the Democratic Party.

Congressional Democrats suffered huge losses in the mid-term elections of 1854, as voters provided support to a wide array of new parties opposed to the Democratic Party. Most victorious congressional candidates who were not affiliated with the Democratic Party had campaigned either independently of the Whig Party or in fusion with another party. "Bleeding Kansas

Bleeding Kansas, Bloody Kansas, or the Border War, was a series of violent civil confrontations in Kansas Territory, and to a lesser extent in western Missouri, between 1854 and 1859. It emerged from a political and ideological debate over the ...

", a struggle between anti-slavery and pro-slavery settlers for control of Kansas Territory

The Territory of Kansas was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 30, 1854, until January 29, 1861, when the eastern portion of the territory was admitted to the United States, Union as the Slave and ...

, escalated in 1855 and 1856, pushing many moderate Northerners to join the nascent Republican Party. As cooperation between Northern and Southern Whigs appeared to be increasingly impossible, leaders from both sections continued to abandon the party. In September 1855, Seward led his faction of Whigs into the Republican Party, effectively marking the end of the Whig Party as an independent and significant political force.Holt (1999), pp. 947–949. In May 1856, after denouncing the Slave Power in a speech on the Senate floor, Senator Sumner was attacked by Congressman Preston Brooks, outraging Northerners. Meanwhile, the 1856 American National Convention nominated former President Fillmore for president, but many Northerners deserted the American Party after the party platform failed to denounce the Kansas–Nebraska Act.

The 1856 Republican National Convention convened in Philadelphia in June 1856. A committee chaired by David Wilmot produced a platform that denounced slavery, the Kansas–Nebraska Act, and the Pierce administration. Though Chase and Seward were the two most prominent members of the nascent party, the Republicans instead nominated John C. Frémont

Major general (United States), Major-General John Charles Frémont (January 21, 1813July 13, 1890) was a United States Army officer, explorer, and politician. He was a United States senator from California and was the first History of the Repub ...

, the son-in-law of Thomas Hart Benton and a political neophyte. The party campaigned on a new version of an old Free Soil slogan: "Free Speech, Free Press, Free Men, Free Labor, Free Territory, and Frémont". With the collapse of the Whig Party, the 1856 presidential election became a three-sided contest between Democrats, Know Nothings, and Republicans. During his campaign, Fillmore minimized the issue of nativism, instead attempting to use his campaign as a platform for unionism and a revival of the Whig Party. Ultimately, Democrat James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was the 15th president of the United States, serving from 1857 to 1861. He also served as the United States Secretary of State, secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and represented Pennsylvan ...

won the election with a majority of the electoral vote and 45 percent of the popular vote; Frémont won most of the remaining electoral votes and took 33 percent of the popular vote, while Fillmore won 21.6 percent of the popular vote and just eight electoral votes. Frémont carried New England, New York, and parts of the Midwest, but Buchanan nearly swept the South and won several Northern states.

Ideology and positions

The 1848 Free Soil platform openly denounced the institution of slavery, demanding that the federal government "relieve itself of all responsibility for the existence and continuance of slavery" by abolishing slavery in all federal districts and territories. The platform declared: " inscribe on our banner, 'Free Soil, Free Speech, Free Labor, and Free Men,' and under it we will fight on, and fight forever, until a triumphant victory shall reward our exertions". Unlike the Liberty Party, the 1848 Free Soil Party platform did not address fugitive slaves or racial discrimination, nor did it call for the abolition of slavery in the states. The party nonetheless earned the support of many former Liberty Party leaders by calling for abolition wherever possible, the chief goal of the Liberty Party. The Free Soil platform also called for lowertariffs

A tariff or import tax is a duty imposed by a national government, customs territory, or supranational union on imports of goods and is paid by the importer. Exceptionally, an export tax may be levied on exports of goods or raw materials and is ...

, reduced postal rates, and improvements to harbors. The 1852 party platform more overtly denounced slavery, and also called for the diplomatic recognition of Haiti

Haiti, officially the Republic of Haiti, is a country on the island of Hispaniola in the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and south of the Bahamas. It occupies the western three-eighths of the island, which it shares with the Dominican ...

. Many Free Soilers also supported the temperance movement

The temperance movement is a social movement promoting Temperance (virtue), temperance or total abstinence from consumption of alcoholic beverages. Participants in the movement typically criticize alcohol intoxication or promote teetotalism, and ...

.

Base of support

During the 1848 election, the Free Soil Party fared best in New York, Vermont, and Massachusetts. Though some anti-slavery Democrats found Cass acceptable or refused to vote for a ticket featuring Charles Francis Adams, about three-fifths of the support for Van Buren's candidacy came from Democrats. About one-fifth of those who voted for Van Buren were former members of the Liberty Party, though a small number of Liberty Party members voted for Gerrit Smith instead. Except in New Hampshire and Ohio, relatively few Whigs voted for Van Buren, as slavery-averse Whigs likeAbraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

, Thaddeus Stevens

Thaddeus Stevens (April 4, 1792August 11, 1868) was an American politician and lawyer who served as a member of the United States House of Representatives from Pennsylvania, being one of the leaders of the Radical Republican faction of the Histo ...

, and Horace Greeley

Horace Greeley (February 3, 1811 – November 29, 1872) was an American newspaper editor and publisher who was the founder and newspaper editor, editor of the ''New-York Tribune''. Long active in politics, he served briefly as a congres ...

largely backed Taylor.

In New England, many trade unionists and land reformers supported the Free Soil Party, though others viewed slavery as a secondary issue or were hostile to the anti-slavery movement. Other Free Soil Party supporters were active in the women's rights movement, and a disproportionate number of those who attended the Seneca Falls Convention were associated with party. One leading women's rights activist, Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton ( Cady; November 12, 1815 – October 26, 1902) was an American writer and activist who was a leader of the women's rights movement in the U.S. during the mid- to late-19th century. She was the main force behind the 1848 ...

, was the wife of Free Soil leader Henry Brewster Stanton and a cousin of Free Soil Congressman Gerrit Smith.

Party leaders and other prominent individuals

Former President Martin Van Buren of New York and Senator John P. Hale of New Hampshire served as the two presidential nominees of the party, while Charles Adams of Massachusetts and Congressman George Washington Julian served as the party's vice-presidential nominees. Salmon P. Chase, Preston King, Gamaliel Bailey, and Benjamin Butler played crucial roles in leading the first party convention and drafting the first party platform. Among those who attended the first Free Soil convention were poet and journalistWalt Whitman

Walter Whitman Jr. (; May 31, 1819 – March 26, 1892) was an American poet, essayist, and journalist; he also wrote two novels. He is considered one of the most influential poets in American literature and world literature. Whitman incor ...

and abolitionist leader Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 14, 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. He was the most impor ...

, the latter of whom was part of a small group of African Americans to attend the convention. In September 1851, Julian, Congressman Joshua Reed Giddings, and Lewis Tappan organized a national Free Soil convention that met in Cleveland, Ohio

Cleveland is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County, Ohio, Cuyahoga County. Located along the southern shore of Lake Erie, it is situated across the Canada–United States border, Canada–U.S. maritime border ...

. Other notable individuals associated with the party include Cassius Marcellus Clay

Major general (United States), Major General Cassius Marcellus Clay (October 9, 1810 – July 22, 1903) was an American planter, politician, military officer and abolitionist who served as the List of ambassadors of the United States to Russia, ...

1876 Democratic presidential nominee Samuel J. Tilden, Senator Charles Sumner

Charles Sumner (January 6, 1811March 11, 1874) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented Massachusetts in the United States Senate from 1851 until his death in 1874. Before and during the American Civil War, he was a leading American ...

, educational reformer Horace Mann, poet John Greenleaf Whittier, future Montana governor Sidney Edgerton, educator Jonathan Blanchard, poet William Cullen Bryant

William Cullen Bryant (November 3, 1794 – June 12, 1878) was an American romantic poet, journalist, and long-time editor of the '' New York Evening Post''. Born in Massachusetts, he started his career as a lawyer but showed an interest in poe ...

, and writer Richard Henry Dana Jr.

Richard Henry Dana Jr. (August 1, 1815 – January 6, 1882) was an American lawyer and politician from Massachusetts, a descendant of a colonial family, who gained renown as the author of the classic American memoir ''Two Years Before the Mast'' a ...

Legacy

Free Soilers in the Republican Party

The Free Soil Party essentially merged into the Republican Party after 1854. However, Martin Van Buren (who had already returned to the Democratic Party in November 1852), his followers and the Barnburners rejoined the Democratic Party. Like their Free Soil predecessors, Republican leaders in the late 1850s generally did not call for the abolition of slavery, but instead sought to prevent the extension of slavery into the territories.McPherson (1988), p. 129. The Republicans combined the Free Soil stance on slavery with Whig positions on economic issues, such as support for high tariffs and federally-funded infrastructure projects. After 1860, the Republican Party became the dominant force in national politics. Reflecting on the new electoral strength of the Republican Party years later, Free Soiler and anti-slavery activist Henry Brewster Stanton wrote that "the feeble cause I espoused at Cincinnati in 1832... ow restedon the broad shoulders of a strong party which was marching to victory." Former Free Soiler Salmon Chase was a major candidate for the presidential nomination at the1860 Republican National Convention

The 1860 Republican National Convention was a United States presidential nominating convention, presidential nominating convention that met May 16–18 in Chicago, Illinois. It was held to nominate the Republican Party (United States), Republic ...

, but Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

defeated Chase, Seward, and other candidates to win the party's presidential nomination. After Lincoln won the 1860 presidential election

United States presidential election, Presidential elections were held in the United States on November 6, 1860. The History of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party ticket of Abraham Lincoln and Hannibal Hamlin emerged victoriou ...

, several Southern states seceded, eventually leading to the Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

. During the war, a faction of the Republican Party known as the Radical Republicans emerged; these Radical Republicans generally went farther than other Republicans in advocating for racial equality and the immediate abolition of slavery. Many of the leading Radical Republicans, including Giddings, Chase, Hale, Julian, and Sumner, had been members of the Free Soil Party. Some Radical Republicans sought to replace Lincoln as the 1864 Republican presidential nominee with either Chase or Frémont, but Lincoln ultimately won re-nomination and re-election.Reichley (2000) p. 108

In 1865, the Civil War came to an end with the surrender of the Confederacy, and the United States abolished slavery nationwide by ratifying the Thirteenth Amendment. Radical Republicans exercised an important influence during the subsequent Reconstruction era

The Reconstruction era was a period in History of the United States, US history that followed the American Civil War (1861-65) and was dominated by the legal, social, and political challenges of the Abolitionism in the United States, abol ...

, calling for ambitious reforms designed to promote the political and economic equality of African Americans in the South.

In 1872, a disproportionate number of former Free Soilers helped found the short-lived Liberal Republican Party, a breakaway group of Republicans who launched an unsuccessful challenge to President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was the 18th president of the United States, serving from 1869 to 1877. In 1865, as Commanding General of the United States Army, commanding general, Grant led the Uni ...

's 1872 re-election bid. Aside from defeating Grant, the party's central goals were the end of Reconstruction, the implementation of civil service reform, and the reduction of tariff rates. Former Free Soiler Charles Francis Adams led on several presidential ballots of the 1872 Liberal Republican convention, but was ultimately defeated by Horace Greeley

Horace Greeley (February 3, 1811 – November 29, 1872) was an American newspaper editor and publisher who was the founder and newspaper editor, editor of the ''New-York Tribune''. Long active in politics, he served briefly as a congres ...

. Many other former Free Soilers remained in the Republican Party, including former Free Soil Congressman Henry Wilson, who served as vice president from 1873 until his death 1875.

Memorials

Free Soil Township, Michigan, was named after the Free Soil party in 1848.Recent revival

In 2014, the party's name was used for the American Free Soil Party with a focus on justice for immigrants, as well as combating discrimination. On February 15, 2019, the American Free Soil Party won ballot access for its first candidate to run under its banner in a partisan race when Dr. James W. Clifton filed to run for town council inMillersburg, Indiana

Millersburg is a town in Clinton Township, Elkhart County, Indiana, Clinton and Benton Township, Elkhart County, Indiana, Benton townships, Elkhart County, Indiana, Elkhart County, Indiana, United States. The population was 903 at the 2010 census ...

. The following day, the party held its national convention and nominated its 2020 presidential ticket, former Southwick Commissioner Adam Seaman of Massachusetts and Dr. Enrique Ramos of Puerto Rico for president and vice president, respectively. On November 5, Clifton lost his race 47% to 53%.

Electoral history

Presidential elections

Members of Congress

Senators Members of the House of RepresentativesCongressional party divisions, 1849–1855

See also

* Origins of the American Civil War *Second Party System

The Second Party System was the Political parties in the United States, political party system operating in the United States from about 1828 to early 1854, after the First Party System ended. The system was characterized by rapidly rising leve ...

* Liberty Party

Notes

References

Works cited

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * * * * Foner, Eric. "Politics and prejudice: The Free Soil party and the Negro, 1849-1852." ''Journal of Negro History'' 50.4 (1965): 239-256. * * * * Marshall, Schuyler C. "The Free Democratic Convention of 1852." ''Pennsylvania History'' 22.2 (1955): 146–167online

* * * *

External links

''Free Soil Banner''

– Indianapolis Free Soil newspaper that ran from 1848 to 1854; digitized by the Indianapolis Marion County Public Library

American Abolitionists and Antislavery Activists

– comprehensive list of abolitionist and anti-slavery activists and organizations in the United States, including the Free Soil Party * {{Authority control 1848 establishments in the United States 1854 disestablishments in the United States American abolitionist organizations Defunct political parties in the United States Political parties disestablished in 1854 Political parties established in 1848 Slavery in the United States Martin Van Buren Henry Wilson Wikipedia articles containing unlinked shortened footnotes