Francoist Repression on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The White Terror (), also called the Francoist Repression (), was the

In November 1937, four months after the Collective Letter of the Spanish Bishops was signed and distributed, the Spanish bishops issued a second letter in which they justified the extermination of the enemy and testified that this was an existing policy. Otherwise, the explicit reference to a policy of extermination, not repression or elimination, leads to biopolitical interpretations.

In November 1937, four months after the Collective Letter of the Spanish Bishops was signed and distributed, the Spanish bishops issued a second letter in which they justified the extermination of the enemy and testified that this was an existing policy. Otherwise, the explicit reference to a policy of extermination, not repression or elimination, leads to biopolitical interpretations.

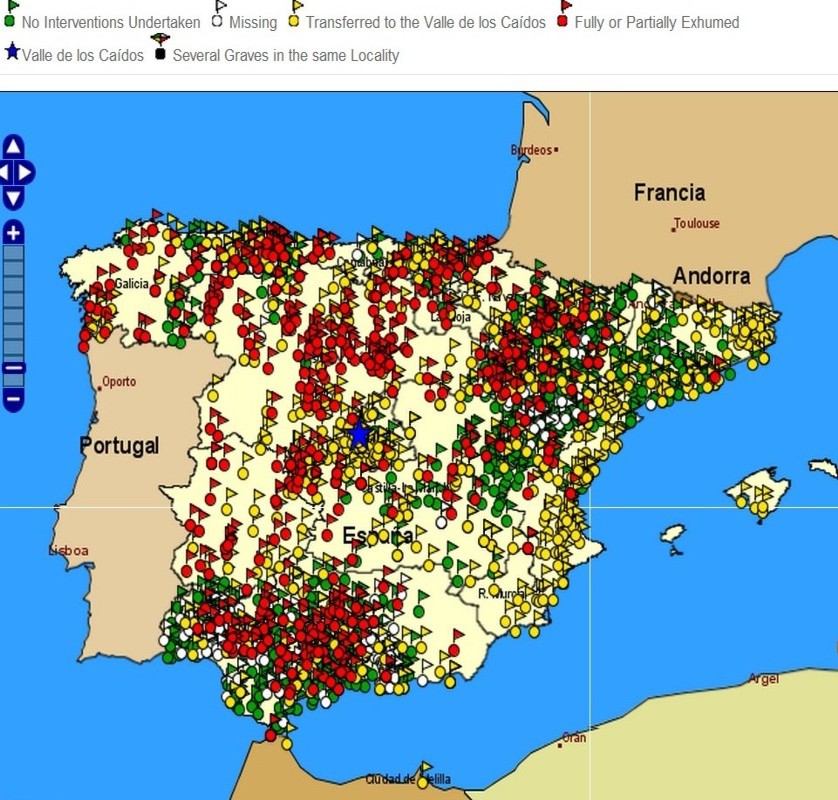

Estimates of executions behind the Nationalist lines during the Spanish Civil War range from fewer than 50,000 to 200,000 (Hugh Thomas: 75,000, Secundino Serrano: 90,000; Josep Fontana: 150,000; and Julián Casanova: 100,000.Casanova, Julián. ''The Spanish Republic and Civil War''. Cambridge University Press. 2010. New York. p. 181.) Most of the victims were killed without a trial in the first months of the war, and their corpses were left on the sides of roads or in clandestine and unmarked mass graves. For example, in Valladolid only 374 officially recorded victims of the repression of a total of 1,303 (there were many other unrecorded victims) were executed after a trial, and the historian Stanley Payne in his work ''Fascism in Spain'' (1999), citing a study by Cifuentes Checa and Maluenda Pons carried out over the Nationalist-controlled city of Zaragoza and its environs, refers to 3,117 killings, of which 2,578 took place in 1936. He goes on to state that by 1938 the military courts there were directing summary executions.

Many of the executions in the course of the war were carried by militants of the fascist party ''Falange'' ('' Falange Española de las J.O.N.S.'') or militants of the

Estimates of executions behind the Nationalist lines during the Spanish Civil War range from fewer than 50,000 to 200,000 (Hugh Thomas: 75,000, Secundino Serrano: 90,000; Josep Fontana: 150,000; and Julián Casanova: 100,000.Casanova, Julián. ''The Spanish Republic and Civil War''. Cambridge University Press. 2010. New York. p. 181.) Most of the victims were killed without a trial in the first months of the war, and their corpses were left on the sides of roads or in clandestine and unmarked mass graves. For example, in Valladolid only 374 officially recorded victims of the repression of a total of 1,303 (there were many other unrecorded victims) were executed after a trial, and the historian Stanley Payne in his work ''Fascism in Spain'' (1999), citing a study by Cifuentes Checa and Maluenda Pons carried out over the Nationalist-controlled city of Zaragoza and its environs, refers to 3,117 killings, of which 2,578 took place in 1936. He goes on to state that by 1938 the military courts there were directing summary executions.

Many of the executions in the course of the war were carried by militants of the fascist party ''Falange'' ('' Falange Española de las J.O.N.S.'') or militants of the

The 2nd president of the Generalitat de Catalunya, Lluís Companys, went into exile in

The 2nd president of the Generalitat de Catalunya, Lluís Companys, went into exile in

'' El Mundo'', 7 July 2002 Julián Casanova Ruiz, nominated in 2008 among the experts in the first judicial investigation (conducted by judge

political repression

Political repression is the act of a state entity controlling a citizenry by force for political reasons, particularly for the purpose of restricting or preventing the citizenry's ability to take part in the political life of a society, thereby ...

and mass violence against dissidents that were committed by the Nationalist faction during the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War () was a military conflict fought from 1936 to 1939 between the Republican faction (Spanish Civil War), Republicans and the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalists. Republicans were loyal to the Left-wing p ...

(1936–1939), as well as during the first nine years of the regime

In politics, a regime (also spelled régime) is a system of government that determines access to public office, and the extent of power held by officials. The two broad categories of regimes are democratic and autocratic. A key similarity acros ...

of General Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (born Francisco Paulino Hermenegildo Teódulo Franco Bahamonde; 4 December 1892 – 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general and dictator who led the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalist forces i ...

. From 1936–1945, Francoist Spain

Francoist Spain (), also known as the Francoist dictatorship (), or Nationalist Spain () was the period of Spanish history between 1936 and 1975, when Francisco Franco ruled Spain after the Spanish Civil War with the title . After his death i ...

officially designated supporters of the Second Spanish Republic

The Spanish Republic (), commonly known as the Second Spanish Republic (), was the form of democratic government in Spain from 1931 to 1939. The Republic was proclaimed on 14 April 1931 after the deposition of Alfonso XIII, King Alfonso XIII. ...

(1931–1939), liberals, socialists

Socialism is an economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes the economic, political, and socia ...

of different stripes, Protestants

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

, intellectuals

An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking, research, and Human self-reflection, reflection about the nature of reality, especially the nature of society and proposed solutions for its normative problems. Coming from the wor ...

, homosexuals, Freemason

Freemasonry (sometimes spelled Free-Masonry) consists of fraternal groups that trace their origins to the medieval guilds of stonemasons. Freemasonry is the oldest secular fraternity in the world and among the oldest still-existing organizati ...

s, Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

, immigrants

Immigration is the international movement of people to a destination country of which they are not usual residents or where they do not possess nationality in order to settle as permanent residents. Commuters, tourists, and other short- ...

as well as Basque

Basque may refer to:

* Basques, an ethnic group of Spain and France

* Basque language, their language

Places

* Basque Country (greater region), the homeland of the Basque people with parts in both Spain and France

* Basque Country (autonomous co ...

, Catalan, Andalusian, and Galician nationalists as enemies.

The Francoist Repression was motivated by the right-wing notion of social cleansing

Social cleansing () is social group-based killing that consists of the elimination of members of society who are considered "undesirable", including, but not limited to, the homeless, criminals, street children, the elderly, the poor, the weak, t ...

(), which meant that the Nationalists immediately started executing people viewed as enemies of the state upon capturing territory. As a response to the similar mass killings of their clergy, religious, and laity during the Republican Red Terror

The Red Terror () was a campaign of political repression and Mass killing, executions in Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Soviet Russia which was carried out by the Bolsheviks, chiefly through the Cheka, the Bolshevik secret police ...

, the Spanish Catholic Church legitimized the killings by the Civil Guard (national police) and the '' Falange'' as a defense of Christendom

The terms Christendom or Christian world commonly refer to the global Christian community, Christian states, Christian-majority countries or countries in which Christianity is dominant or prevails.SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christen ...

.

Repression was ideologically hardwired into the Francoist regime, and according to Ramón Arnabat, it turned "the whole country into one wide prison". The regime accused the loyalist supporters of the Republic of having "adherence to the rebellion", providing "aid to the rebellion", or "military rebellion"; using the Republicans' own ideological tactics against them. Franco's Law of Political Responsibilities (), in force until 1962, gave legalistic color of law to the political repression that characterized the defeat and dismantling of the Second Spanish Republic

The Spanish Republic (), commonly known as the Second Spanish Republic (), was the form of democratic government in Spain from 1931 to 1939. The Republic was proclaimed on 14 April 1931 after the deposition of Alfonso XIII, King Alfonso XIII. ...

and punished Loyalist Spaniards.

The historian Stanley G. Payne

Stanley George Payne (born September 9, 1934) is an American historian of modern Spain and Europe, European fascism at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. He retired from full-time teaching in 2004 and is currently Professor Emeritus at its Dep ...

considers the White Terror's death toll to be greater than the death toll of the corresponding Red Terror.

Background

After a trio of crises in 1917, the spiral of violence in Morocco and the lead-up to the installment of the dictatorship of Miguel Primo de Rivera through a 1923 military ''coup d'état'' won the acquiescence ofAlfonso XIII

Alfonso XIII (Spanish language, Spanish: ''Alfonso León Fernando María Jaime Isidro Pascual Antonio de Borbón y Habsburgo-Lorena''; French language, French: ''Alphonse Léon Ferdinand Marie Jacques Isidore Pascal Antoine de Bourbon''; 17 May ...

. Upon the political failure of the dictatorship, Alfonso XIII removed support from Primo de Rivera (who was thereby forced to resign in 1930) and favoured a return to the pre-1923 state of affairs during the so-called '' dictablanda''. Nevertheless, he had lost most of his political capital along the way. Alfonso XIII voluntarily left Spain after the municipal elections of April 1931understood as a plebiscite for maintaining the monarchy or declaring a republicwhich led to the proclamation of the Second Spanish Republic on 14 April 1931. The Second Spanish Republic

The Spanish Republic (), commonly known as the Second Spanish Republic (), was the form of democratic government in Spain from 1931 to 1939. The Republic was proclaimed on 14 April 1931 after the deposition of Alfonso XIII, King Alfonso XIII. ...

was led by President Niceto Alcalá-Zamora, whose government instituted a program of secular

Secularity, also the secular or secularness (from Latin , or or ), is the state of being unrelated or neutral in regards to religion. The origins of secularity can be traced to the Bible itself. The concept was fleshed out through Christian hi ...

reforms, which included agrarian reform

Land reform (also known as agrarian reform) involves the changing of laws, regulations, or customs regarding land ownership, land use, and land transfers. The reforms may be initiated by governments, by interested groups, or by revolution.

Lan ...

, the separation of church and state

The separation of church and state is a philosophical and Jurisprudence, jurisprudential concept for defining political distance in the relationship between religious organizations and the State (polity), state. Conceptually, the term refers to ...

, the right to divorce

Divorce (also known as dissolution of marriage) is the process of terminating a marriage or marital union. Divorce usually entails the canceling or reorganising of the legal duties and responsibilities of marriage, thus dissolving the M ...

, women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the women's rights, right of women to Suffrage, vote in elections. Several instances occurred in recent centuries where women were selectively given, then stripped of, the right to vote. In Sweden, conditional women's suffra ...

(November 1933), the socio-political reformation of the Spanish Army

The Spanish Army () is the terrestrial army of the Spanish Armed Forces responsible for land-based military operations. It is one of the oldest Standing army, active armies – dating back to the late 15th century.

The Spanish Army has existed ...

, and political autonomy

In developmental psychology and moral, political, and bioethical philosophy, autonomy is the capacity to make an informed, uncoerced decision. Autonomous organizations or institutions are independent or self-governing. Autonomy can also be ...

for Catalonia

Catalonia is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a ''nationalities and regions of Spain, nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia of 2006, Statute of Autonomy. Most of its territory (except the Val d'Aran) is situate ...

and the Basque Country (October 1936). President Alcalá-Zamora's reforms to Spanish society were continually blocked by the right-wing parties and rejected by the far-left Confederación Nacional del Trabajo

The (CNT; ) is a Spanish anarcho-syndicalist national trade union center, trade union confederation.

Founded in 1910 in Barcelona from groups brought together by the trade union ''Solidaridad Obrera (historical union), Solidaridad Obrera'', ...

(CNT). The Second Spanish Republic suffered attacks from the right wing (the failed ''coup d'état'' of Sanjurjo in 1932), and the left wing (the Asturian miners' strike of 1934), whilst enduring the economic impact of the Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

.

After the Popular Fronta coalition of leftist parties (Spanish Socialist Workers' Party

The Spanish Socialist Workers' Party ( , PSOE ) is a Social democracy, social democratic Updated as required.The PSOE is described as a social-democratic party by numerous sources:

*

*

*

* List of political parties in Spain, political party ...

(PSOE), Republican Left (IR), Republican Union (UR), Communist Party (PCE), Workers' Party of Marxist Unification (POUM), Republican Left of Catalonia

The Republican Left of Catalonia (, ERC; ; generically branded as ) is a pro-Catalan independence, social democratic political party in the Spanish autonomous community of Catalonia, with a presence also in Valencia, the Balearic Islands and t ...

(ERC) and others)won the general election of February 1936, the Spanish right-wing planned to overthrow the democratic Republic in a ''coup d'état'' to reinstall the monarchy. Finally, on 17 July 1936, a part of the Spanish Army, led by a group of far-right

Far-right politics, often termed right-wing extremism, encompasses a range of ideologies that are marked by ultraconservatism, authoritarianism, ultranationalism, and nativism. This political spectrum situates itself on the far end of the ...

-wing officers (the generals José Sanjurjo

José Sanjurjo y Sacanell (; 28 March 1872 – 20 July 1936) was a Spanish military officer who was one of the military leaders who plotted the July 1936 ''coup d'état'' that started the Spanish Civil War.

He was endowed the nobiliary title ...

, Manuel Goded Llopis, Emilio Mola, Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (born Francisco Paulino Hermenegildo Teódulo Franco Bahamonde; 4 December 1892 – 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general and dictator who led the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalist forces i ...

, Miguel Cabanellas

Miguel Cabanellas Ferrer (1 January 1872 – 14 May 1938) was a Spanish Army officer. He was a leading figure of the 1936 Spanish coup d'état, 1936 coup d'état in Zaragoza and sided with the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationali ...

, Gonzalo Queipo de Llano

Gonzalo Queipo de Llano y Sierra (5 February 1875 – 9 March 1951) was a Spanish Army general. He distinguished himself quickly in his career, fighting in Cuba and Morocco, later becoming outspoken about military and political figures which led ...

, José Enrique Varela, and others) launched a military ''coup d'état'' against the Spanish Republic in July 1936. The generals' ''coup d'état'' failed, but the rebellious army, known as the Nationalists, controlled a large part of Spain; this was the start of the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War () was a military conflict fought from 1936 to 1939 between the Republican faction (Spanish Civil War), Republicans and the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalists. Republicans were loyal to the Left-wing p ...

.

Franco, one of the coup's leaders, and his Nationalist army won the Spanish Civil War in 1939. Franco ruled Spain for the next 36 years until his death in 1975. Besides the mass assassinations of Republican political enemies, political prisoner

A political prisoner is someone imprisoned for their political activity. The political offense is not always the official reason for the prisoner's detention.

There is no internationally recognized legal definition of the concept, although ...

s were imprisoned in concentration camp

A concentration camp is a prison or other facility used for the internment of political prisoners or politically targeted demographics, such as members of national or ethnic minority groups, on the grounds of national security, or for exploitati ...

s and homosexual

Homosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or sexual behavior between people of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexual attractions" exc ...

s were confined in psychiatric hospitals.

Repressive thinking

The Chief Prosecutor of the Francoist army, Felipe Acedo Colunga, wrote in the internal report of 1939:According to the historian Francisco Espinosa, Felipe Acedo proposed an exemplary model of repression to create the new fascist state "on the site of the race." Absolute purification was needed, "stripped of all feelings of personal piety." According to Espinosa, the legal model for repression was the German ( National Socialist) procedural system, where the prosecutor could act outside legal considerations. What was important was the unwritten right that, according toHermann Göring

Hermann Wilhelm Göring (or Goering; ; 12 January 1893 – 15 October 1946) was a German Nazism, Nazi politician, aviator, military leader, and convicted war criminal. He was one of the most powerful figures in the Nazi Party, which gov ...

, people carry as "a sacred ember in their blood."

According to Franco, the issue of Catalonia was one of the main reasons for the war. General Gonzalo Queipo de Llano

Gonzalo Queipo de Llano y Sierra (5 February 1875 – 9 March 1951) was a Spanish Army general. He distinguished himself quickly in his career, fighting in Cuba and Morocco, later becoming outspoken about military and political figures which led ...

wrote in an article subtitled "Against Catalonia, the Israel of the modern world", published in ''Diario Palentino'' on November 26, 1936, that Franco's regime considered Catalan people

Catalans (Catalan language, Catalan, French language, French and Occitan language, Occitan: ''catalans''; ; ; or ) are a Romance languages, Romance ethnic group native to Catalonia, who speak Catalan language, Catalan. The current official c ...

to be "a race of Jews, because they use the same procedures that the Hebrews

The Hebrews (; ) were an ancient Semitic-speaking peoples, ancient Semitic-speaking people. Historians mostly consider the Hebrews as synonymous with the Israelites, with the term "Hebrew" denoting an Israelite from the nomadic era, which pre ...

perform in all the nations of the globe." Queipo de Llano declared, "When the war is over, Pompeu Fabra

Pompeu Fabra i Poch (; Gràcia, Barcelona, 20 February 1868 – Prada de Conflent, 25 December 1948) was a Catalan engineer and grammarian. He was the main author of the normative reform of contemporary Catalan language, and is the namesa ...

and his works will be dragged along the Ramblas". Fabra standarized the Catalan language, and his house was raided; his large personal library was burned in the middle of the street, but Fabra was able to escape and entered exile.

Policy of extermination of the enemy

In November 1937, four months after the Collective Letter of the Spanish Bishops was signed and distributed, the Spanish bishops issued a second letter in which they justified the extermination of the enemy and testified that this was an existing policy. Otherwise, the explicit reference to a policy of extermination, not repression or elimination, leads to biopolitical interpretations.

In November 1937, four months after the Collective Letter of the Spanish Bishops was signed and distributed, the Spanish bishops issued a second letter in which they justified the extermination of the enemy and testified that this was an existing policy. Otherwise, the explicit reference to a policy of extermination, not repression or elimination, leads to biopolitical interpretations.

Red and White Terrors

From the beginning of the war in July 1936, the ideological nature of the Nationalist fight against the Republicans indicated the degree of dehumanisation of the lower social classes (peasants and workers) in the view of the politically reactionary sponsors of the nationalist forces, the Roman Catholic Church of Spain, the aristocracy, the landowners, and the military, commanded by Franco. Captain Gonzalo de Aguilera y Munro, a public affairs officer for the Nationalist forces, told the American reporter John Thompson Whitaker: The Nationalists committed their atrocities in public, sometimes with assistance from members of the local Catholic Church clergy. In August 1936, the Massacre of Badajoz ended with the shooting of between 500 and 4,000 Republicans; and on August 20, after a Mass and a multitudinous parade, two Republican city mayors (Juan Antonio Rodríguez Machín and ), Socialist deputy Nicolás de Pablo and 15 other people (7 of them Portuguese) were publicly executed. The assassination of hospitalized and wounded Republican soldiers was also a common practice. Among the children of the landlords, the joke name (agrarian reform) identified the horseback hunting parties by which they killed insubordinate peasantry and so cleansed their lands of communists. The joke name alluded to the grave where the corpses of the hunted peasants were dumped: the piece of land for which the dispossessed peasants had revolted. Early in the civil war most of the victims of the White Terror and the Red Terror were killed in mass executions behind the respective front lines of the Nationalist and the Republican forces: Common to the political purges of the left-wing and right-wing belligerents were the , the taking of prisoners from jails and prisons, who then were taken for a , a ride tosummary execution

In civil and military jurisprudence, summary execution is the putting to death of a person accused of a crime without the benefit of a free and fair trial. The term results from the legal concept of summary justice to punish a summary offense, a ...

. Most of the victims were killed by death squad

A death squad is an armed group whose primary activity is carrying out extrajudicial killings, massacres, or enforced disappearances as part of political repression, genocide, ethnic cleansing, or revolutionary terror. Except in rare cases in w ...

s, from the trade unions, and by the paramilitary militias of the political parties (the Republican CNT, UGT, and PCE; the Nationalist ''Falange'' and Carlist). Among the justifications for summary execution of right-wing enemies was reprisal for aerial bombings of civilians; other people were killed after being denounced as an enemy of the people, by false accusations motivated by personal envy and hatred. Nevertheless, the significant differences between White political terrorism and Red political terrorism were indicated by Francisco Partaloa, prosecutor of the Supreme Court of Madrid (Tribunal Supremo de Madrid) and a friend of the aristocrat General Queipo de Llano, who witnessed the assassinations, first in the Republican camp and then in the Nationalist camp of the Spanish Civil War:

Historians of the Spanish Civil War, such as Helen Graham, Paul Preston

Sir Paul Preston CBE (born 21 July 1946) is an English historian and Hispanist, biographer of Francisco Franco, and specialist in Spanish history, in particular the Spanish Civil War, which he has studied for more than 50 years. He is the winn ...

, Antony Beevor

Sir Antony James Beevor, (born 14 December 1946) is a British military historian. He has published several popular historical works, mainly on the Second World War, the Spanish Civil War, and most recently the Russian Revolution and Civil War. ...

, Gabriel Jackson, Hugh Thomas, and Ian Gibson concurred that the mass killings committed behind the Nationalist frontlines were organized and approved by the Nationalist rebel authorities, while the killings behind the Republican front lines resulted from the societal breakdown of the Second Spanish Republic:

In the second volume of ''A History of Spain and Portugal'' (1973), Stanley G. Payne

Stanley George Payne (born September 9, 1934) is an American historian of modern Spain and Europe, European fascism at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. He retired from full-time teaching in 2004 and is currently Professor Emeritus at its Dep ...

said that the political violence in the Republican zone was organized by the left-wing political parties:

That, unlike the political repression by the right wing

Right-wing politics is the range of Ideology#Political ideologies, political ideologies that view certain social orders and Social stratification, hierarchies as inevitable, natural, normal, or desirable, typically supporting this position b ...

, which "was concentrated against the most dangerous opposition elements", the Republican attacks were irrational, which featured the "murdering finnocent people, and letting some of the more dangerous go free. Moreover, one of the main targets of the Red terror was the clergy, most of whom were not engaged in overt opposition" to the Spanish Republic. Nonetheless, in a letter-to-the-editor of the '' ABC'' newspaper in Seville, Miguel de Unamuno

Miguel de Unamuno y Jugo (; ; 29 September 1864 – 31 December 1936) was a Spanish essayist, novelist, poet, playwright, philosopher, professor of Greek and Classics, and later rector at the University of Salamanca.

His major philosophical ...

said that, unlike the assassinations in the areas held by the Republic, the methodical assassinations effected by the White Terror were ordered by the highest authorities of the Nationalist rebellion, and identified General Mola as the proponent of the political cleansing policies of the White Terror.

When news of the mass killings of Republican soldiers and sympathizersGeneral Mola's policy to terrorise the Republicansreached the Republican government, the Defence Minister Indalecio Prieto

Indalecio Prieto Tuero (30 April 1883 – 11 February 1962) was a Spanish politician, a minister and one of the leading figures of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) in the years before and during the Second Spanish Republic. Less radi ...

pleaded with the Spanish republicans:

Moreover, despite his political loyalty to the reactionary rebellion of the Nationalists, the right-wing writer José María Pemán was concerned about the volume of the mass killings; in ''My Lunches with Important People'' (1970), he reported a conversation with General Miguel Cabanellas in late 1936:

Civil War

The White Terror commenced on 17 July 1936, the day of the Nationalist ''coup d'état'', with hundreds of assassinations committed in the area controlled by the right-wing rebels, but it had been planned before earlier. In the 30 June 1936 secret instructions for the ''coup d'état'' in Morocco, Mola ordered the rebels "to eliminate left-wing elements, communists, anarchists, union members, etc." The White Terror included the repression of political opponents in areas occupied by the Nationalist, mass executions in areas captured from the Republicans, such as the Massacre of Badajoz, and looting. In ''The Spanish Labyrinth'' (1943),Gerald Brenan

Edward FitzGerald "Gerald" Brenan, CBE, Military Cross, MC (7 April 1894 – 19 January 1987) was a British writer and hispanist who spent much of his life in Spain.

Brenan is probably best known for ''The Spanish Labyrinth'', a historical wo ...

said that:

... thanks to the failure of the ''coup d'état'' and to the eruption of the Falangist and Carlist militias, with their previously prepared lists of victims, the scale on which these executions took place exceeded all precedent. Andalusia, where the supporters of Franco were a tiny minority, and where the military commander, General Queipo de Llano, was a pathological figure recalling the Conde de España of theOther examples include the bombing of civilian areas such as Guernica,First Carlist War The First Carlist War was a civil war in Spain from 1833 to 1840, the first of three Carlist Wars. It was fought between two factions over the succession to the throne and the nature of the Monarchy of Spain, Spanish monarchy: the conservative a ..., was drenched in blood. The famous massacre of Badajoz was merely the culminating act of a ritual that had already been performed in every town and village in the South-West of Spain.

Madrid

Madrid ( ; ) is the capital and List of largest cities in Spain, most populous municipality of Spain. It has almost 3.5 million inhabitants and a Madrid metropolitan area, metropolitan area population of approximately 7 million. It i ...

, Málaga

Málaga (; ) is a Municipalities in Spain, municipality of Spain, capital of the Province of Málaga, in the Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia. With a population of 591,637 in 2024, it is the second-most populo ...

, Almería

Almería (, , ) is a city and municipalities in Spain, municipality of Spain, located in Andalusia. It is the capital of the province of Almería, province of the same name. It lies in southeastern Iberian Peninsula, Iberia on the Mediterranean S ...

, Lérida

Lleida (, ; ; ''#Name, see below'') is a city in the west of Catalonia, Spain. It is the capital and largest town in Segrià, Segrià county, the Ponent, Ponent region and the province of Lleida. Geographically, it is located in the Catalan Cent ...

, Alicante

Alicante (, , ; ; ; officially: ''/'' ) is a city and municipalities of Spain, municipality in the Valencian Community, Spain. It is the capital of the province of Alicante and a historic Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean port. The population ...

, Durango

Durango, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Durango, is one of the 31 states which make up the Political divisions of Mexico, 32 Federal Entities of Mexico, situated in the northwest portion of the country. With a population of 1,832,650 ...

, Granollers

Granollers (; ) is a city in central Catalonia, about 30 kilometres north-east of Barcelona. It is the capital and most densely populated city in the comarca of Vallès Oriental.

Granollers is now a bustling business centre, having grown from ...

, Alcañiz, Valencia

Valencia ( , ), formally València (), is the capital of the Province of Valencia, province and Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Valencian Community, the same name in Spain. It is located on the banks of the Turia (r ...

and Barcelona

Barcelona ( ; ; ) is a city on the northeastern coast of Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second-most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within c ...

by the Luftwaffe

The Luftwaffe () was the aerial warfare, aerial-warfare branch of the before and during World War II. German Empire, Germany's military air arms during World War I, the of the Imperial German Army, Imperial Army and the of the Imperial Ge ...

''( Legion Condor)'' and the Italian air force

The Italian Air Force (; AM, ) is the air force of the Italy, Italian Republic. The Italian Air Force was founded as an independent service arm on 28 March 1923 by Victor Emmanuel III of Italy, King Victor Emmanuel III as the ("Royal Air Force ...

''( Aviazione Legionaria)'' (according to Gabriel Jackson estimates range from 5,000 to 10,000 victims of the bombings), killings of Republican POWs

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of war for a ...

, rape

Rape is a type of sexual assault involving sexual intercourse, or other forms of sexual penetration, carried out against a person without consent. The act may be carried out by physical force, coercion, abuse of authority, or against a person ...

, forced disappearances

An enforced disappearance (or forced disappearance) is the secret abduction or imprisonment of a person with the support or acquiescence of a State (polity), state followed by a refusal to acknowledge the person's fate or whereabouts with the i ...

including whole Republican military units such as the 221st Mixed Brigadeand the establishment of Francoist prisons in the aftermath of the Republicans' defeat.

Goals and victims of the repression

The main goal of the White Terror was to terrify the civil population who opposed the coup, eliminate the supporters of the Republic and the militants of the leftist parties, and because of this, some historians have considered the White Terror a genocide. In fact, one of the leaders of the coup, General Mola, said: Sánchez Léon says that the thanatopolitics and thebiopolitics

Biopolitics is a concept popularized by the French philosopher Michel Foucault in the mid-20th century. At its core, biopolitics explores how governmental power operates through the management and regulation of a population's bodies and lives.

...

of the Francoist repression simultaneously obeyed to the logics of a civil war, a colonial conquest and a Catholic holy war, but was unleashed upon a population hitherto considered part of the same community. Features such as the institutional processes, policies and practices put in motion by the victors, the indiscriminate massacres, the re-catholisation of the defeated, the forced exile and the exclusion from the benefits of full citizenship or the application of retroactive repressive rulings crystallised in the definition of the Republicans as anti-Spanish, a terminology that intermingles the perception of the enemies as "non-citizens", as "inferior beings" and as alien to the values that defined the self-imagined (confessional) nation. Behind the generic term 'Reds' there was a notion of enemy in an absolute sense, targeted for eradication.

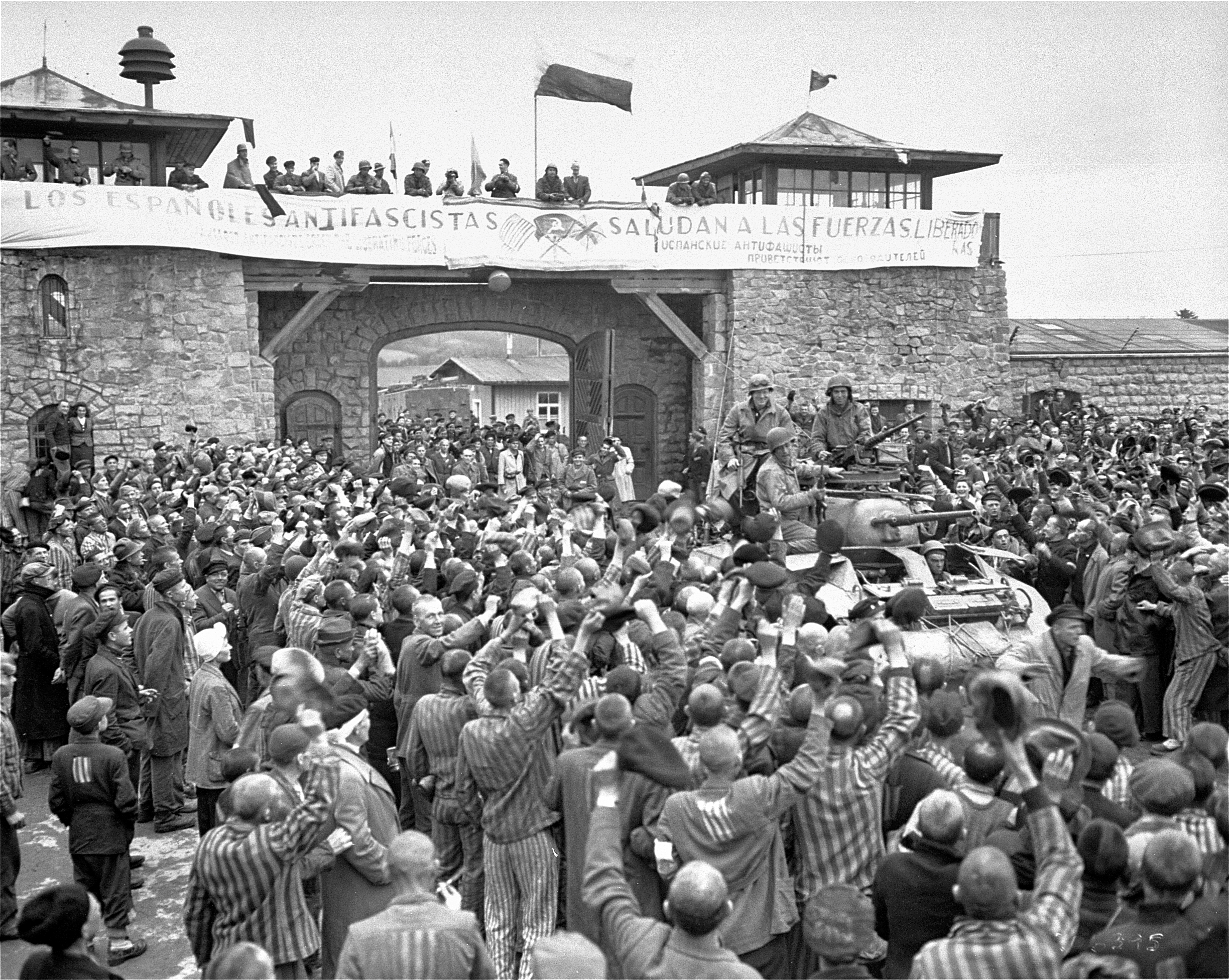

In areas controlled by the Nationalists, targeted were:

* government officials and Popular Front politicians (in the city of Granada 23 of the 44 councillors of the city's corporation were executed),, and people suspected of voting for the Popular Front

* union leaders

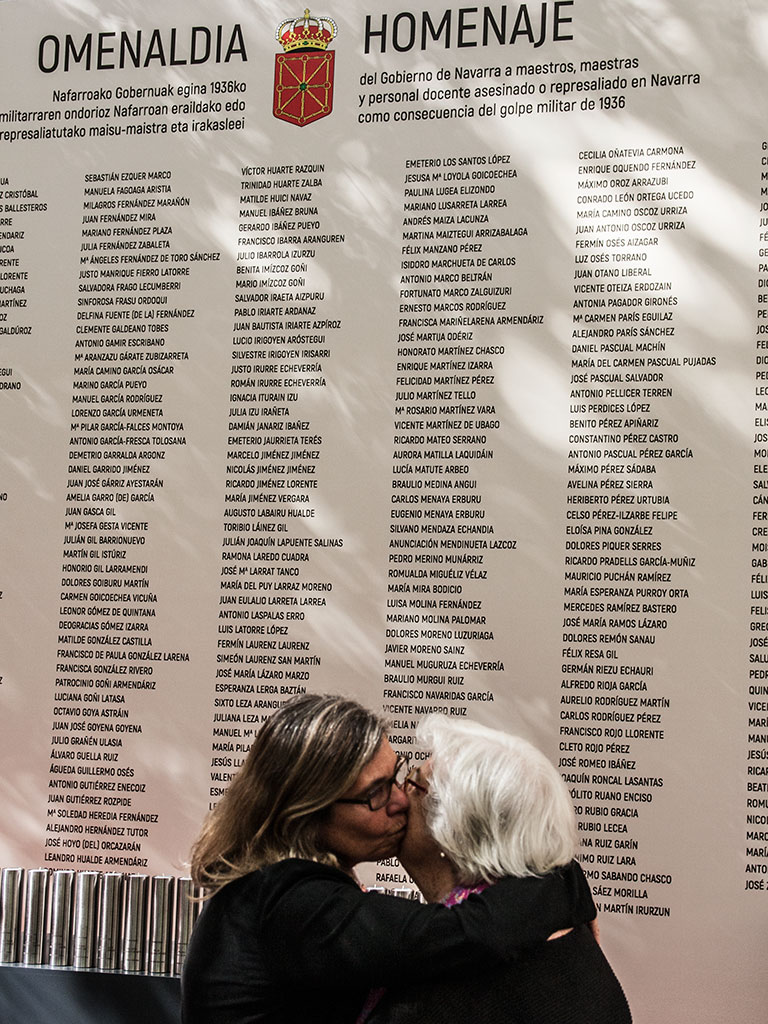

* teachers, hundreds of whom were killed by the Nationalists in the first weeks of the war

* intellectuals - for example, in Granada, between 26 July 1936 and 1 March 1939, the poet Federico García Lorca

Federico del Sagrado Corazón de Jesús García Lorca (5 June 1898 – 19 August 1936) was a Spanish poet, playwright, and theatre director. García Lorca achieved international recognition as an emblematic member of the Generation of '27, a g ...

, the editor of the left-wing newspaper '' El Defensor de Granada'', the professor of paediatrics at Granada University, the rector of the university, the professor of political law, the professor of pharmacy, the professor of history, the engineer of the road to the top of the Sierra Morena and the best-known doctor in the city were killed by the Nationalists, and in the city of Cordoba, "nearly the entire republican elite, from deputies to booksellers, were executed in August, September and December...",

* suspected Freemasons

Freemasonry (sometimes spelled Free-Masonry) consists of fraternal groups that trace their origins to the medieval guilds of stonemasons. Freemasonry is the oldest secular fraternity in the world and among the oldest still-existing organizati ...

, such as in Huesca, where there were only twelve Freemasons, the Nationalists killed a hundred suspected Freemasons,

* Basque

Basque may refer to:

* Basques, an ethnic group of Spain and France

* Basque language, their language

Places

* Basque Country (greater region), the homeland of the Basque people with parts in both Spain and France

* Basque Country (autonomous co ...

, Catalan, Andalusian or Galician nationalists, among them Manuel Carrasco i Formiguera, leader of Democratic Union of Catalonia ''Unió Democrática de Catalunya'', Alexandre Bóveda, one of the founders of the '' Partido Galeguista'' and Blas Infante

Blas Infante Pérez de Vargas (5 July 1885 – 11 August 1936) was an Andalusian socialist politician, Georgist, writer, historian and musicologist. He is considered the "father of Andalusia" by Andalusian nationalists.

He initiated an Andal ...

.

* military officers who had remained loyal to the government of the Republic, among them the Army generals Domingo Batet, Enrique Salcedo Molinuevo, Miguel Campíns, Nicolás Molero, Nuñez de Prado, Manuel Romerales and Rogelio Caridad Pita.

Victims were usually brought before local committees and imprisoned or executed. The living conditions in the improvised Nationalist prisons were very harsh. One former Republican prisoner stated:

At times we were forty prisoners in a cell built to accommodate two people. There were two benches, each capable of seating three persons, and the floor to sleep on. For our private needs, there were only three chamberpots. They had to be emptied into an old rusty cauldron which also served for washing our clothes. We were forbidden to have food brought to us from outside, and were given disgusting soup cooked with soda ash which kept us in a constant state of dysentery. We were all in a deplorable state. The air was unbreathable and the babies choked many nights for lack of oxygen... To be imprisoned, according to the rebels, was to lose all individuality. The most elementary human rights were unknown and people were killed as easily as rabbits...Because of the mass terror in many areas controlled by the Nationalists, thousands of Republicans left their homes and tried to hide in nearby forests or mountainsthese Republicans became known as . Many of them later joined the

Spanish maquis

The Maquis (; ; also spelled maqui) were Spanish guerrillas who waged irregular warfare against the Francoist dictatorship within Spain following the Republican defeat in the Spanish Civil War until the early 1960s, carrying out sabotage, rob ...

, the anti-Francoist guerrilla force that continued to fight against the Francoist State in the post-war era. Hundreds of thousands of others fled to the areas controlled by the Second Republic. In 1938, there were more than one million refugees in Barcelona alone. In many cases, when someone fled the Nationalists executed their relatives. One witness in Zamora stated: "All the members of the Flechas family, both men and women, were killed, a total of seven persons. A son succeeded in escaping, but in his place, they killed his eight-months-pregnant fiancé Transito Alonso and her mother, Juana Ramos." Furthermore, thousands of Republicans joined the ''Falange'' and the Nationalist army in order to escape the repression. In fact, many supporters of the Nationalists referred to the ''Falange'' as "our reds" and to the ''Falanges blue shirt as the ''salvavidas'' (life jacket). In Granada, one supporter of the Nationalists said:

Another major target of the Terror was women, with the overall goal of keeping them in their traditional place in Spanish society. To this end, the Nationalist army promoted a campaign of targeted rape. Queipo de Llano spoke multiple times over the radio warning that "immodest" women with Republican sympathies would be raped by his Moorish troops. Near Seville, Nationalist soldiers raped a truckload of female prisoners, threw their bodies down a well, and paraded around town with their rifles draped with their victims' underwear. These rapes were not the result of soldiers disobeying orders, but official Nationalist policies, with officers specifically choosing Moors to be the primary perpetrators. Advancing Nationalist troops scrawled "Your children will give birth to fascists" on the walls of captured buildings, and many women taken prisoner were force fed castor oil

Castor oil is a vegetable oil pressed from castor beans, the seeds of the plant ''Ricinus communis''. The seeds are 40 to 60 percent oil. It is a colourless or pale yellow liquid with a distinct taste and odor. Its boiling point is and its den ...

, a powerful laxative

Laxatives, purgatives, or aperients are substances that loosen stools and increase bowel movements. They are used to treat and prevent constipation.

Laxatives vary as to how they work and the side effects they may have. Certain stimulant, lubri ...

, and then paraded in public naked.

Death toll

Estimates of executions behind the Nationalist lines during the Spanish Civil War range from fewer than 50,000 to 200,000 (Hugh Thomas: 75,000, Secundino Serrano: 90,000; Josep Fontana: 150,000; and Julián Casanova: 100,000.Casanova, Julián. ''The Spanish Republic and Civil War''. Cambridge University Press. 2010. New York. p. 181.) Most of the victims were killed without a trial in the first months of the war, and their corpses were left on the sides of roads or in clandestine and unmarked mass graves. For example, in Valladolid only 374 officially recorded victims of the repression of a total of 1,303 (there were many other unrecorded victims) were executed after a trial, and the historian Stanley Payne in his work ''Fascism in Spain'' (1999), citing a study by Cifuentes Checa and Maluenda Pons carried out over the Nationalist-controlled city of Zaragoza and its environs, refers to 3,117 killings, of which 2,578 took place in 1936. He goes on to state that by 1938 the military courts there were directing summary executions.

Many of the executions in the course of the war were carried by militants of the fascist party ''Falange'' ('' Falange Española de las J.O.N.S.'') or militants of the

Estimates of executions behind the Nationalist lines during the Spanish Civil War range from fewer than 50,000 to 200,000 (Hugh Thomas: 75,000, Secundino Serrano: 90,000; Josep Fontana: 150,000; and Julián Casanova: 100,000.Casanova, Julián. ''The Spanish Republic and Civil War''. Cambridge University Press. 2010. New York. p. 181.) Most of the victims were killed without a trial in the first months of the war, and their corpses were left on the sides of roads or in clandestine and unmarked mass graves. For example, in Valladolid only 374 officially recorded victims of the repression of a total of 1,303 (there were many other unrecorded victims) were executed after a trial, and the historian Stanley Payne in his work ''Fascism in Spain'' (1999), citing a study by Cifuentes Checa and Maluenda Pons carried out over the Nationalist-controlled city of Zaragoza and its environs, refers to 3,117 killings, of which 2,578 took place in 1936. He goes on to state that by 1938 the military courts there were directing summary executions.

Many of the executions in the course of the war were carried by militants of the fascist party ''Falange'' ('' Falange Española de las J.O.N.S.'') or militants of the Carlist

Carlism (; ; ; ) is a Traditionalism (Spain), Traditionalist and Legitimist political movement in Spain aimed at establishing an alternative branch of the Bourbon dynasty, one descended from Infante Carlos María Isidro of Spain, Don Carlos, ...

party ('' Comunión Tradicionalista'') militia ('' Requetés''), but with the approval of the Nationalist government.

Cooperation of the Spanish Church

The Spanish Church approved of the White Terror and cooperated with the rebels. According to Antony Beevor:Cardinal Gomá stated that 'Jews and Masons poisoned the national soul with absurd doctrine'... A few brave priests put their lives at risk by criticizing Nationalist atrocities, but the majority of the clergy in Nationalist areas revelled in their new-found power and the increased size of their congregations. Anyone who did not attend Mass faithfully was likely to be suspected of 'red' tendencies. Entrepreneurs made a great money selling religious symbols... It was reminiscent of the way the Inquisition's persecutions of Jews and Moors helped make pork such an important part of the Spanish diet.One witness in Zamora said:

Many priests acted very badly. The bishop of Zamora in 1936 was more or less an assassinI don't remember his name. He must be held responsible because prisoners appealed to him to save their lives. All he would reply was that the Reds had killed more people than the Falangists were killing.(The bishop of Zamora in 1936 was Manuel Arce y Ochotorena) Nevertheless, the Nationalists killed at least 16 Basque nationalist priests (among them the arch-priest of Mondragon), and imprisoned or deported hundreds more. Several priests who tried to halt the killings and at least one priest who was a Mason were killed. Regarding the callous attitude of the

Vatican

Vatican may refer to:

Geography

* Vatican City, an independent city-state surrounded by Rome, Italy

* Vatican Hill, in Rome, namesake of Vatican City

* Ager Vaticanus, an alluvial plain in Rome

* Vatican, an unincorporated community in the ...

, Manuel Montero, lecturer of the University of the Basque Country

The University of the Basque Country (, ''EHU''; , ''UPV''; officially EHU) is a Spanish public university of the Basque Country (autonomous community), Basque Autonomous Community.

Heir of the University of Deusto, University of Bilbao, initial ...

commented on 6 May 2007:

Repression in the South and the drive to Madrid

The White Terror was especially harsh in the southern part of Spain (Andalusia and Extremadura). The rebels bombed and seized the working-class districts of the main Andalusian cities in the first days of the war, and afterwards went on to execute thousands of workers and militants of the leftist parties: in the city of Cordoba 4,000; in the city of Granada 5,000; in the city ofSeville

Seville ( ; , ) is the capital and largest city of the Spain, Spanish autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the Guadalquivir, River Guadalquivir, ...

3,028; and in the city of Huelva 2,000 killed and 2,500 disappeared. The city of Málaga, occupied by the Nationalists in February 1937 following the Battle of Málaga, experienced one of the harshest repressions following Francoist victory with an estimated total of 17,000 people summarily executed. Carlos Arias Navarro, then a young lawyer who as public prosecutor signed thousands of execution warrants in the trials set up by the triumphant rightists, became known as "The Butcher of Málaga" (). Over 4,000 people were buried in mass graves.

Even rural towns were not spared, such as Lora del Rio in the province of Seville

The Province of Seville () is a province of southern Spain, in the western part of the autonomous community of Andalusia. It borders the provinces of Málaga and Cádiz in the south, Huelva in the west, Badajoz in the north and Córdoba in the ...

, where the Nationalists killed 300 peasants as a reprisal for the assassination of a local landowner. In the province of Córdoba the Nationalists killed 995 Republicans in Puente Genil and about 700 loyalists were murdered by the orders of Nationalist Colonel Sáenz de Buruaga in Baena, although other estimates mention up to 2,000 victims following the Baena Massacre.

Paul Preston estimates the total number of victims of the Nationalists in Andalusia at 55,000.

Troops of North Africa

The colonial troops of theSpanish Army of Africa

The Army of Africa (, , Tarifit, Riffian; ''Aserdas n Tefriqt''), also known as the Army of Spanish Morocco ('), was a field army of the Spanish Army that garrisoned the Spanish protectorate in Morocco from 1912 until History of Morocco#Independ ...

(''Ejército de África''), composed mainly of the Moroccan '' regulares'' and the Spanish Legion

For centuries, Spain recruited foreign soldiers to its army, forming the foreign regiments () such as the Regiment of Hibernia (formed in 1709 from Irishmen who fled their own country in the wake of the Flight of the Earls and the Penal la ...

, under the command of Colonel Juan Yagüe, made up the feared shock troops of the Francoist military. In their advance towards Madrid from Sevilla through Andalusia and Extremadura

Extremadura ( ; ; ; ; Fala language, Fala: ''Extremaúra'') is a landlocked autonomous communities in Spain, autonomous community of Spain. Its capital city is Mérida, Spain, Mérida, and its largest city is Badajoz. Located in the central- ...

these troops routinely killed dozens or hundreds in every town or city conquered. but in the Massacre of Badajoz the number of Republicans killed reached several thousands. Furthermore, the colonial troops raped many working-class women and looted the houses of the Republicans.

Anti-Catalan hostility

InTarragona

Tarragona (, ; ) is a coastal city and municipality in Catalonia (Spain). It is the capital and largest town of Tarragonès county, the Camp de Tarragona region and the province of Tarragona. Geographically, it is located on the Costa Daurada ar ...

, in January 1939, Mass was held by a canon from Salamanca

Salamanca () is a Municipality of Spain, municipality and city in Spain, capital of the Province of Salamanca, province of the same name, located in the autonomous community of Castile and León. It is located in the Campo Charro comarca, in the ...

cathedral, José Artero. During the sermon he cried: "Catalan dogs! You are not worthy of the sun that shines on you." () Regarding the men who entered and marched through Barcelona, Franco said the honour was not ''"because they had fought better, but because they were those who felt more hatred. That is, more hatred towards Catalonia and Catalans."'' ()

A close friend of Franco, Victor Ruiz Albéniz, published an article in which he demanded that Catalonia receive "a Biblical punishment (Sodom and Gomarrah) to purify the red city, the headquarters of anarchism and separatism as the only remedy to remove these two cancers by relentless cauterisation" (''"un castigo bíblico (Sodoma y Gomorra) para purificar la ciudad roja, la sede del anarquismo y separatismo como único remedio para extirpar esos dos cánceres por termocauterio implacable")'', while for Serrano Suñer, brother-in-law of Franco and Minister of the Interior, Catalan nationalism was "an illness" ("una enfermedad.")

The man appointed as civil governor of Barcelona, Wenceslao González Oliveros, said that "Spain was raised, with as much or more force against the dismembered statutes as against Communism and that any tolerance of regionalism would again lead to the same processes of putrefaction that we have just surgically removed." (''"España se alzó, con tanta o más fuerza contra los Estatutos desmembrados que contra el comunismo y que cualquier tolerancia del regionalismo llevaría otra vez a los mismos procesos de putrefacción que acabamos de extirpar quirúrgicamente.")''

Even Catalan conservatives, such as Francesc Cambó

Francesc Cambó i Batlle (; 2 September 1876 – 30 April 1947) was a Conservatism, conservative Spain, Spanish politician from Principality of Catalonia, Catalonia, founder and leader of the autonomist party ''Lliga Regionalista''. He was a mini ...

, were themselves frightened by Franco's hatred and spirit of revenge. Cambó wrote of Franco in his diary: "As if he did not feel or understand the miserable, desperate situation in which Spain finds itself and only thinks about his victory, he feels the need to travel the whole country (...) like a bullfighter to gather applause, cigars, hats and some scarce jacket." (''"Como si no sintiera ni comprendiera la situación miserable, desesperada, en que se encuentra España y no pensara más que en su victoria, siente la necesidad de recorrer todo el país (...) como un torero para recoger aplausos, cigarros, sombreros y alguna americana escasa.")''

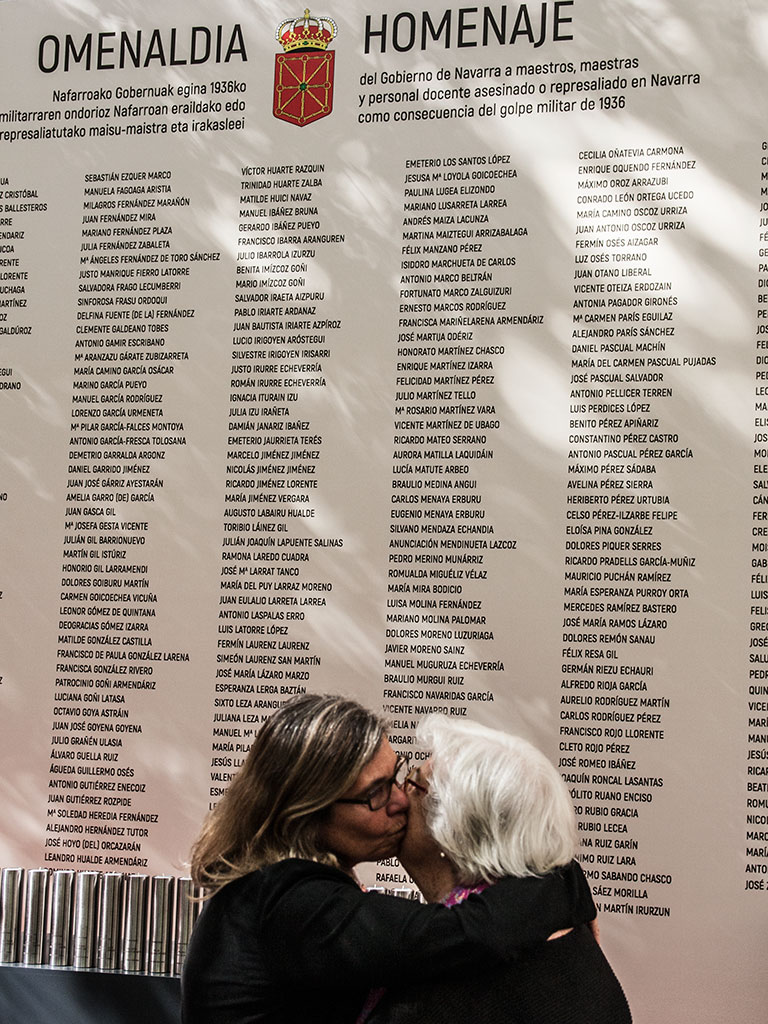

The 2nd president of the Generalitat de Catalunya, Lluís Companys, went into exile in

The 2nd president of the Generalitat de Catalunya, Lluís Companys, went into exile in France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, like many others, in January 1939. The Spanish authorities asked for him to be extradited to Germany. The questions remains whether he was detained by the Gestapo

The (, ), Syllabic abbreviation, abbreviated Gestapo (), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of F ...

or the German military police, known as the Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the German Army (1935–1945), ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmac ...

. In any case, he was detained on August 13, 1940, and immediately deported to Franco's Spain.

After a summary court martial

A court-martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of members of the mili ...

without due process, he was executed on October 15, 1940, at Montjuïc Castle. Since then there have been many calls to cancel that judgement, without success.

Francoist repression

There was a confluence between Spanish regenerationism and the degenerationist theories originated in France and Great Britain. During the first third of the 1900s, the ideal of the " new man" was growing in power, and its zenith was in Nazi racial politics. The Spanish political and social elites, who could not tolerate the loss of Spain's colonies, saw the Second Spanish Republic and Catalan autonomy as a threat to their status, power, and wealth, which caused them to subscribe to the ideal of the new man. The Spanish elites also could not tolerate Catalonia's industrial wealth, and accused Catalonia of being given preferable treatment, impoverishing the rest of Spain via behavior that was described as Semitic (the idea of using work as a means to exploit and subjugate nations in Nazi ideology). According toPaul Preston

Sir Paul Preston CBE (born 21 July 1946) is an English historian and Hispanist, biographer of Francisco Franco, and specialist in Spanish history, in particular the Spanish Civil War, which he has studied for more than 50 years. He is the winn ...

in the book "Arquitectes del terror. Franco i els artifex de l'odi", a number of characters theorized about "anti-Spain", pointing to enemies, and in this sense accused politicians and republican intellectuals of being of Jewish race or servants of the same as masons. This accusation is widespread in Catalonia for most politicians and intellectuals, starting with Macià, Companys and Cambó, identified as Jews. "Racisme i supremacisme polítics a l'Espanya contemporània" documents this thought of the social part that would be raised against the Republic. In a mixture of degenerationism, regenerationism, and neocolonialism, it is postulated that the Spanish racealways understood as Castilianhas degenerated, and degenerate individuals are prone to "contract" communism and separatism. In addition, some areas, such as the south of the peninsula and the Catalan countries

The Catalan Countries (, ) refers to the territories where the Catalan language is spoken. They include the Spanish regions of Catalonia, the Balearic Islands, Valencian Community, and parts of Aragon ('' La Franja'') and Murcia ( Carche), as ...

, are considered to be degenerate wholesale, the former due to Arab remains that lead them to a "rifty" behavior, and the latter due to Semitic remains that lead them towards communism and separatism (the catanalism of any kind is called separatism).

The degeneration of individuals calls for a cleansing if it wants a prosperous and leading nation, capable of building an empire, one of the obsessions of Franco (as well as other totalitarian regimes of the time). In this regard, rebel spokesman Gonzalo de Aguilera, in 1937, told a journalist: "''Now I hope you understand what we mean by the regeneration of Spain ... Our program consists of exterminating a third of the Spanish male population ...''", and an interview can also be mentioned in an Italian newspaper where Franco describes that the war was aimed at "''to save the Homeland that was sinking in the sea of dissociation and racial degeneration''".

In addition to the repression throughout Spain against certain individuals, all this seems to be the source of the fierce repression, such as the Terror of Don Bruno, in Andalusia

Andalusia ( , ; , ) is the southernmost autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in Peninsular Spain, located in the south of the Iberian Peninsula, in southwestern Europe. It is the most populous and the second-largest autonomou ...

, and the no less fierce repression against Catalonia

Catalonia is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a ''nationalities and regions of Spain, nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia of 2006, Statute of Autonomy. Most of its territory (except the Val d'Aran) is situate ...

, with the addition that as a result, the attack on Catalan culture, lasted throughout the Franco regime and ended up becoming a structural element of the state.

Postwar

WhenHeinrich Himmler

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler (; 7 October 1900 – 23 May 1945) was a German Nazism, Nazi politician and military leader who was the 4th of the (Protection Squadron; SS), a leading member of the Nazi Party, and one of the most powerful p ...

visited Spain in 1940, a year after Franco's victory, he claimed to have been

"shocked" by the brutality of the Falangist repression. In July 1939, the foreign minister of Fascist Italy

Fascist Italy () is a term which is used in historiography to describe the Kingdom of Italy between 1922 and 1943, when Benito Mussolini and the National Fascist Party controlled the country, transforming it into a totalitarian dictatorship. Th ...

, Galeazzo Ciano

Gian Galeazzo Ciano, 2nd Count of Cortellazzo and Buccari ( , ; 18 March 1903 – 11 January 1944), was an Italian diplomat and politician who served as Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Foreign Minister in the government of his father-in-law ...

, reported of "trials going on every day at a speed which I would call almost summary... There are still a great number of shootings. In Madrid alone, between 200 and 250 a day, in Barcelona 150, in Seville 80". While authors like Payne have cast doubts on the democratic leanings of the Republic, "fascism was clearly on the other ide"

Repressive laws

According to Beevor, Spain was an open prison for all those who opposed Franco. Until 1963, all the opponents of the Francoist State were brought before military courts. A number of repressive laws were issued, including the Law of Political Responsibilities (''Ley de Responsabilidades Políticas'') in February 1939, the Law of Security of State (''Ley de Seguridad del Estado'') in 1941 (which regarded illegal propaganda or labour strikes as military rebellion), the Law for the Repression of Masonry and Communism (''Ley de Represión de la Masonería y el Comunismo'') on 2 March 1940, and the Law for the Repression of Banditry and Terrorism (''Ley para la represión del Bandidaje y el Terrorismo'') in April 1947, which targeted the ''maquis''. Furthermore, in 1940, the Francoist State established the Tribunal for the eradication of Freemasonry and Communism (''Tribunal Especial para la Represión de la Masonería y el Comunismo''). Political parties and trade unions were forbidden except for the government party, Traditionalist Spanish Phalanx of the Councils of the National Syndicalist Offensive (''FET y de las JONS

The Falange Española Tradicionalista y de las Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional Sindicalista (; FET y de las JONS), frequently shortened to just "FET", was the sole legal party of the Francoist regime in Spain. It was created by General Francisco ...

''), and the official trade union Spanish Syndical Organization (''Sindicato Vertical''). Hundreds of militants and supporters of the parties and trade unions declared illegal under Francoist Spain, such as the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party

The Spanish Socialist Workers' Party ( , PSOE ) is a Social democracy, social democratic Updated as required.The PSOE is described as a social-democratic party by numerous sources:

*

*

*

* List of political parties in Spain, political party ...

(''Partido Socialista Obrero Español'', PSOE); the Communist Party of Spain

The Communist Party of Spain (; PCE) is a communist party that, since 1986, has been part of the United Left coalition, which is currently part of Sumar. Two of its politicians are Spanish government ministers: Yolanda Díaz (Minister of L ...

(''Partido Comunista de España'', PCE); the General Union of Workers (''Unión General de Trabajadores

The Unión General de Trabajadores (UGT, General Union of Workers) is a major Spanish trade union, historically affiliated with the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE).

History

The UGT was founded 12 August 1888 by Pablo Iglesias Posse i ...

'', UGT); and the National Confederation of Labor (''Confederación Nacional del Trabajo

The (CNT; ) is a Spanish anarcho-syndicalist national trade union center, trade union confederation.

Founded in 1910 in Barcelona from groups brought together by the trade union ''Solidaridad Obrera (historical union), Solidaridad Obrera'', ...

'', CNT), were imprisoned or executed. The regional languages, like Basque

Basque may refer to:

* Basques, an ethnic group of Spain and France

* Basque language, their language

Places

* Basque Country (greater region), the homeland of the Basque people with parts in both Spain and France

* Basque Country (autonomous co ...

and Catalan, were also forbidden, and the statutes of autonomy of Catalonia

Catalonia is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a ''nationalities and regions of Spain, nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia of 2006, Statute of Autonomy. Most of its territory (except the Val d'Aran) is situate ...

, Galicia, and the Basque Country were abolished. Censorship of the press (the Law of Press, passed in April 1938) and of cultural life was rigorously exercised and forbidden books destroyed.

Executions, forced labour and medical experiments

At the end of the Spanish Civil War the executions of the "enemies of the state" continued (some 50,000 people were killed), including the extrajudicial (death squad) executions of members of the Spanish maquis (anti–Francoist guerrillas) and their supporters (''los enlaces'', "the links"); in the province of Córdoba 220 ''maquis'' and 160 ''enlaces'' were killed. Thousands of men and women were imprisoned after the civil war in Francoist concentration camps, approximately 367,000 to 500,000 prisoners were held in 50 camps or prisons. In 1933, before the war, the prisons of Spain contained some 12,000 prisoners; just seven years later, in 1940, just one year after the end of the civil war, 280,000 prisoners were held in more than 500 prisons throughout the country. The principal purpose of the Francoist concentration camps was to classify the prisoners of war from the defeated Spanish Republic; men and women who were classified as "unrecoverable", were put to death. After the war, the Republican prisoners were sent to work in militarised penal colonies (''Colonias Penales Militarizadas''), penal detachments (''Destacamentos Penales'') and disciplinary battalions of worker-soldiers (''Batallones Disciplinarios de Soldados Trabajadores''). According to Beevor, 90,000 Republican prisoners were sent off to 121 labour battalions and 8,000 to military workshops. In 1939, Ciano said about the Republican prisoners of war: "They are not prisoners of war, they are slaves of war". Thousands of prisoners (15,947 in 1943) were forced to work building dams, highways, the Guadalquivir Canal (10,000 political prisoners worked on its construction between 1940 and 1962), the Carabanchel Prison, the Valley of the Fallen ('' Valle de los Caídos'') (20,000 political prisoners worked in its construction) and in coal mines in Asturias and Leon. The severe overcrowding of the prisons (according toAntony Beevor

Sir Antony James Beevor, (born 14 December 1946) is a British military historian. He has published several popular historical works, mainly on the Second World War, the Spanish Civil War, and most recently the Russian Revolution and Civil War. ...

270,000 prisoners were spread around jails with capacity for 20,000), poor sanitary conditions and the lack of food caused thousands of deaths (4,663 prisoner deaths were recorded between 1939 and 1945 in 13 of the 50 Spanish provinces), among them the poet Miguel Hernández and the politician Julián Besteiro

Julián Besteiro Fernández (, 21 September 1870 – 27 September 1940) was a Spanish Socialism, socialist politician, elected to the and in 1931 as Speaker of the Constituent Cortes of the Second Spanish Republic, Spanish Republic. He also was ...

. New investigations suggest that the actual number of dead prisoners was much higher, with around 15,000 deaths just in 1941 (the worst year).

Just as with the death toll from executions by the Nationalists during the Civil War, historians have made different estimations the victims of the White Terror after the war. Stanley Payne estimates 30,000 executions following the end of the war. Recent searches conducted with parallel excavations of mass graves in Spain (in particular by the Association for the Recovery of Historical Memory

Association may refer to:

*Club (organization), an association of two or more people united by a common interest or goal

*Trade association, an organization founded and funded by businesses that operate in a specific industry

*Voluntary associatio ...

, ARMH) estimate that the total of people executed after the war arrive at a number between 15,000 and 35,000.Fosas ComunesLos desaparecidos de Franco. La Guerra Civil no ha terminado'' El Mundo'', 7 July 2002 Julián Casanova Ruiz, nominated in 2008 among the experts in the first judicial investigation (conducted by judge

Baltasar Garzón

Baltasar Garzón Real (; born 26 October 1955) is a Spanish former judge in Spain's central criminal court, the '' Audiencia Nacional'' responsible for investigation the most serious criminal cases, including terrorism, organised crime, crimes ...

) against the Francoist crimes, estimates 50,000. Historian Josep Fontana says 25,000. According to Gabriel Jackson, the number of victims of the White Terror (executions and hunger or illness in prisons) just between 1939 and 1943 was 200,000.

A Francoist psychiatrist, Antonio Vallejo-Nájera, carried out medical experiments on prisoners in the Francoist concentration camps to "establish the bio-psych roots of Marxism".

Vallejo Najera also said that it was necessary to remove the children of the Republican women from their mothers. Thousands of children were taken from their mothers and handed over to Francoist families (in 1943 12,043). Many of the mothers were executed afterwards. "For mothers who had a baby with themand there were manythe first sign that they were to be executed was when their infant was snatched from them. Everyone knew what this meant. A mother whose little one was taken had only a few hours left to live".

Stanley Payne observes that Franco's repression did not undergo "cumulative radicalisation" like that of Hitler; in fact, the opposite occurred, with major persecution being slowly reduced. All but 5 per cent of death sentences under Franco's rule occurred by 1941. During the next thirty months, military prosecutors sought 939 death sentences, most of which were not approved and others commuted. On October 1, 1939, all former Republican personnel serving a sentence of less than six years were pardoned. In 1940 special military judicial commissions were created to examine sentences and were given the power to confirm or reduce them but never to extend them. Later that year, provisional liberty was granted to all political prisoners serving less than six years, and in April 1941, this was also granted to those serving less than twelve years and then fourteen years in October. Provisional liberty was extended to those serving up to twenty years in December 1943.

Fate of Republican exiles

Furthermore, hundreds of thousands were forced into exile (470,000 in 1939), with many intellectuals and artists who had supported the Republic such asAntonio Machado

Antonio Cipriano José María y Francisco de Santa Ana Machado y Ruiz (26 July 1875 – 22 February 1939), known as Antonio Machado, was a Spanish poet and one of the leading figures of the Spanish literary movement known as the Generation ...

, Ramon J. Sender, Juan Ramón Jiménez, Rafael Alberti, Luis Cernuda, Pedro Salinas, Manuel Altolaguirre, Emilio Prados, Max Aub, Francisco Ayala, Jorge Guillén, León Felipe, Arturo Barea, Pablo Casals

Pau Casals i Defilló (Catalan: ; 29 December 187622 October 1973), known in English as Pablo Casals,Jesús Bal y Gay, Rodolfo Halffter, Julián Bautista, Salvador Bacarisse,  When Nazi Germany occupied

When Nazi Germany occupied

The Francoist State carried out extensive purges among the civil service. Thousands of officials loyal to the Republic were expelled from the army. Thousands of university and school teachers lost their jobs (a quarter of all Spanish teachers). Priority for employment was always given to Nationalist supporters, and it was necessary to have a "good behavior" certificate from local Falangist officials and parish priests. Furthermore, the Francoist State encouraged tens of thousands of Spaniards to denounce their Republican neighbours and friends:

The Francoist State carried out extensive purges among the civil service. Thousands of officials loyal to the Republic were expelled from the army. Thousands of university and school teachers lost their jobs (a quarter of all Spanish teachers). Priority for employment was always given to Nationalist supporters, and it was necessary to have a "good behavior" certificate from local Falangist officials and parish priests. Furthermore, the Francoist State encouraged tens of thousands of Spaniards to denounce their Republican neighbours and friends:

''Time''"Spain Faces Up to Franco's Guilt"

''Newsweek''"War Bones"

''Franco's Crimes''

Amnesty International-Spain, ''The Long History of Truth''

''Civil War in Galicia''

The Limits of Quantification: Francoist Repression

* ttp://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/world/europe/article5802820.ece ''Times Online''The lost childrens of the francoism*

The return of the Republican memory in Spain

Singling Out Victims: Denunciation and Collusion in the Post-Civil War Francoist Repression in Spain, 1939–1945

Franco's Carnival of death. Paul Preston.

{{Spanish Civil War Human rights abuses in Spain Political repression in Spain Politicides Spanish Civil War Far-right terrorism in Spain War crimes of the Spanish Civil War Anti-communist terrorism Christian terrorism in Europe Persecution by Christians Persecution of LGBTQ people in Spain Persecution of intellectuals Anti-anarchism in Spain Anti-Jewish pogroms in Europe Racially motivated violence in Europe Racism in Spain Political and cultural purges Wartime sexual violence in Europe

Josep Lluís Sert

Josep Lluís Sert i López (; 1 July 190215 March 1983) was a Catalan architect and city planner established in the USA after 1939.

Biography

Born in Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain, Sert showed keen interest in the works of his uncle, the painte ...

, Margarita Xirgu, Maruja Mallo, Claudio Sánchez Albornoz, Américo Castro, Clara Campoamor, Victoria Kent, Pablo Picasso

Pablo Diego José Francisco de Paula Juan Nepomuceno María de los Remedios Cipriano de la Santísima Trinidad Ruiz y Picasso (25 October 1881 – 8 April 1973) was a Spanish painter, sculptor, printmaker, Ceramic art, ceramicist, and Scenic ...

, Maria Luisa Algarra, Alejandro Casona, Rosa Chacel, Maria Zambrano, Josep Carner, Manuel de Falla

Manuel de Falla y Matheu (, 23 November 187614 November 1946) was a Spanish composer and pianist. Along with Isaac Albéniz, Francisco Tárrega, and Enrique Granados, he was one of Spain's most important musicians of the first half of the 20t ...

, Paulino Masip, María Teresa León, Alfonso Castelao, Jose Gaos and Luis Buñuel

Luis Buñuel Portolés (; 22 February 1900 – 29 July 1983) was a Spanish and Mexican filmmaker who worked in France, Mexico and Spain. He has been widely considered by many film critics, historians and directors to be one of the greatest and ...

.

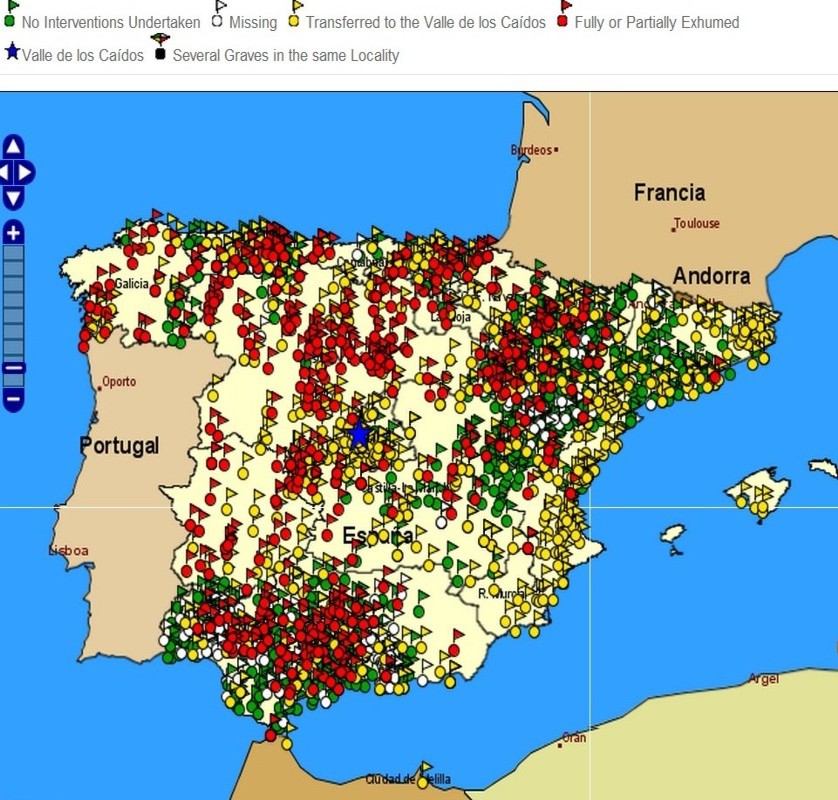

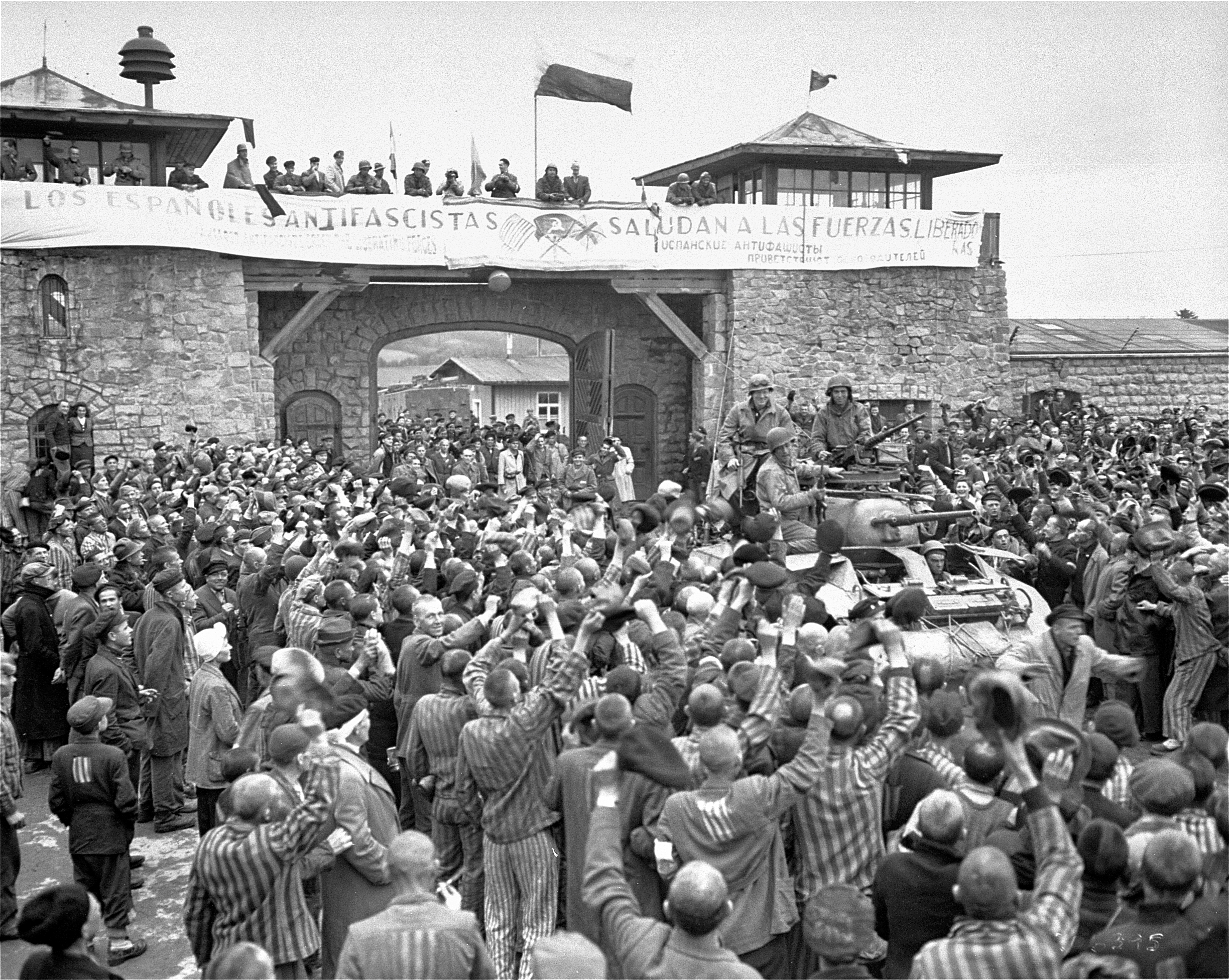

When Nazi Germany occupied

When Nazi Germany occupied France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, Franco's politicians encouraged the Germans to detain and to deport thousands of Republican refugees to the concentration camps. 15,000 Spanish Republicans were deported to Dachau, Buchenwald

Buchenwald (; 'beech forest') was a German Nazi concentration camp established on Ettersberg hill near Weimar, Germany, in July 1937. It was one of the first and the largest of the concentration camps within the Altreich (Old Reich) territori ...

(including the writer Jorge Semprún), Bergen-Belsen

Bergen-Belsen (), or Belsen, was a Nazi concentration camp in what is today Lower Saxony in Northern Germany, northern Germany, southwest of the town of Bergen, Lower Saxony, Bergen near Celle. Originally established as a prisoner of war camp, ...

, Sachsenhausen-Oranienburg (among them the politician Francisco Largo Caballero

Francisco Largo Caballero (15 October 1869 – 23 March 1946) was a Spanish politician and trade unionist who served as the prime minister of the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War. He was one of the historic leaders of the ...

), Auschwitz

Auschwitz, or Oświęcim, was a complex of over 40 concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland (in a portion annexed into Germany in 1939) during World War II and the Holocaust. It consisted of Auschw ...

, Flossenburg and Mauthausen (5,000 out of 7,200 Spanish prisoners at Mauthausen died there). Other Spanish Republicans were detained by the Gestapo

The (, ), Syllabic abbreviation, abbreviated Gestapo (), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of F ...

, handed over to Spain and executed, among them Julián Zugazagoitia

Julián Zugazagoitia Mendieta (5 February 1899, Bilbao – 9 November 1940, Madrid) was a Spanish journalist and politician.

A member of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party, he was close to Indalecio Prieto and the editor of the ''El Socialista ...

, Juan Peiró, Francisco Cruz Salido and Lluis Companys

Luis is a given name. It is the Spanish language, Spanish form of the originally Germanic language, Germanic name or . Other Iberian Romance languages have comparable forms: (with an accent mark on the i) in Portuguese language, Portuguese and G ...

(president of the Generalitat of Catalonia

The Generalitat de Catalunya (; ; ), or the Government of Catalonia, is the institutional system by which Catalonia is Self-governance, self-governed as an autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Spain. It is made up of the Parli ...

) and another 15,000 were forced to work building the Atlantic Wall