Ethnic Greeks on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an

The Greeks speak the

The Greeks speak the

Most of the feuding Greek city-states were, in some scholars' opinions, united by force under the banner of

Most of the feuding Greek city-states were, in some scholars' opinions, united by force under the banner of

The

The

ethnic group

An ethnic group or an ethnicity is a grouping of people who identify with each other on the basis of shared attributes that distinguish them from other groups. Those attributes can include common sets of traditions, ancestry, language, history, ...

and nation

A nation is a community of people formed on the basis of a combination of shared features such as language, history, ethnicity, culture and/or society. A nation is thus the collective identity of a group of people understood as defined by those ...

indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean

Eastern Mediterranean is a loose definition of the eastern approximate half, or third, of the Mediterranean Sea, often defined as the countries around the Levantine Sea.

It typically embraces all of that sea's coastal zones, referring to communi ...

and the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Roma ...

regions, namely Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

, Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is geo ...

, Albania

Albania ( ; sq, Shqipëri or ), or , also or . officially the Republic of Albania ( sq, Republika e Shqipërisë), is a country in Southeastern Europe. It is located on the Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea and shares ...

, Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

, Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

, Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

, and, to a lesser extent, other countries surrounding the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ea ...

. They also form a significant diaspora

A diaspora ( ) is a population that is scattered across regions which are separate from its geographic place of origin. Historically, the word was used first in reference to the dispersion of Greeks in the Hellenic world, and later Jews after ...

(), with Greek communities established around the world..

Greek colonies and communities have been historically established on the shores of the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ea ...

and Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Roma ...

, but the Greek people themselves have always been centered on the Aegean and Ionian seas, where the Greek language

Greek ( el, label=Modern Greek, Ελληνικά, Elliniká, ; grc, Ἑλληνική, Hellēnikḗ) is an independent branch of the Indo-European family of languages, native to Greece, Cyprus, southern Italy (Calabria and Salento), southern Al ...

has been spoken since the Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

.. Until the early 20th century, Greeks were distributed between the Greek peninsula

Greece is a country of the Balkans, in Southeastern Europe, bordered to the north by Albania, North Macedonia and Bulgaria; to the east by Turkey, and is surrounded to the east by the Aegean Sea, to the south by the Cretan and the Libyan Seas, an ...

, the western coast of Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

, the Black Sea coast, Cappadocia

Cappadocia or Capadocia (; tr, Kapadokya), is a historical region in Central Anatolia, Turkey. It largely is in the provinces Nevşehir, Kayseri, Aksaray, Kırşehir, Sivas and Niğde.

According to Herodotus, in the time of the Ionian Revo ...

in central Anatolia, Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

, the Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

, Cyprus, and Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

. Many of these regions coincided to a large extent with the borders of the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

of the late 11th century and the Eastern Mediterranean areas of ancient Greek colonization

Greek colonization was an organised colonial expansion by the Archaic Greeks into the Mediterranean Sea and Black Sea in the period of the 8th–6th centuries BC.

This colonization differed from the migrations of the Greek Dark Ages in that i ...

. The cultural centers of the Greeks have included Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

, Thessalonica

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its metropolitan area, and the capital of the geographic region of ...

, Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

, Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; grc, Σμύρνη, Smýrnē, or , ) was a Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna rose to promi ...

, and Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

at various periods.

In recent times, most ethnic Greeks live within the borders of the modern Greek state or in Cyprus. The Greek genocide

The Greek genocide (, ''Genoktonia ton Ellinon''), which included the Pontic genocide, was the systematic killing of the Christians, Christian Ottoman Greeks, Ottoman Greek population of Anatolia which was carried out mainly during World War I ...

and population exchange between Greece and Turkey

The 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey ( el, Ἡ Ἀνταλλαγή, I Antallagí, ota, مبادله, Mübâdele, tr, Mübadele) stemmed from the "Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations" signed at ...

nearly ended the three millennia-old Greek presence in Asia Minor. Other longstanding Greek populations can be found from southern Italy to the Caucasus and southern Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

and Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

and in the Greek diaspora

The Greek diaspora, also known as Omogenia ( el, Ομογένεια, Omogéneia), are the communities of Greeks living outside of Greece and Cyprus (excluding Northern Cyprus). Such places historically include Albania, North Macedonia, parts of ...

communities in a number of other countries. Today, most Greeks are officially registered as members of the Greek Orthodox Church

The term Greek Orthodox Church (Greek: Ἑλληνορθόδοξη Ἐκκλησία, ''Ellinorthódoxi Ekklisía'', ) has two meanings. The broader meaning designates "the entire body of Orthodox (Chalcedonian) Christianity, sometimes also call ...

.CIA World Factbook

''The World Factbook'', also known as the ''CIA World Factbook'', is a reference resource produced by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) with almanac-style information about the countries of the world. The official print version is available ...

on Greece: Greek Orthodox 98%, Greek Muslim

Greek Muslims, also known as Grecophone Muslims, are Muslims of Greek ethnic origin whose adoption of Islam (and often the Turkish language and identity) dates to the period of Ottoman rule in the southern Balkans. They consist primarily of th ...

1.3%, other 0.7%.

Greeks have greatly influenced and contributed to culture, visual arts, exploration, theatre, literature, philosophy, ethics, politics, architecture, music, mathematics, medicine, science, technology, commerce, cuisine and sports. The Greek language

Greek ( el, label=Modern Greek, Ελληνικά, Elliniká, ; grc, Ἑλληνική, Hellēnikḗ) is an independent branch of the Indo-European family of languages, native to Greece, Cyprus, southern Italy (Calabria and Salento), southern Al ...

is the oldest written language still in use and its vocabulary has been the basis of many languages, including English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

as well as international scientific nomenclature. Greek was by far the most widely spoken lingua franca

A lingua franca (; ; for plurals see ), also known as a bridge language, common language, trade language, auxiliary language, vehicular language, or link language, is a language systematically used to make communication possible between groups ...

in the Mediterranean world and the New Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Christ ...

of the Christian Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of a ...

was also originally written in Greek.

History

Greek language

Greek ( el, label=Modern Greek, Ελληνικά, Elliniká, ; grc, Ἑλληνική, Hellēnikḗ) is an independent branch of the Indo-European family of languages, native to Greece, Cyprus, southern Italy (Calabria and Salento), southern Al ...

, which forms its own unique branch within the Indo-European

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family, English, French, Portuguese, Russian, Dutch ...

family of languages, the Hellenic. They are part of a group of classical ethnicities, described by Anthony D. Smith

Anthony David Stephen Smith (23 September 1939 – 19 July 2016) was a British historical sociologist who, at the time of his death, was Professor Emeritus of Nationalism and Ethnicity at the London School of Economics. He is considered one of ...

as an "archetypal diaspora people".

Origins

The Proto-Greeks probably arrived at the area now called Greece, in the southern tip of theBalkan peninsula

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

, at the end of the 3rd millennium BC between 2200 and 1900 BC. The sequence of migrations into the Greek mainland during the 2nd millennium BC

The 2nd millennium BC spanned the years 2000 BC to 1001 BC.

In the Ancient Near East, it marks the transition from the Middle to the Late Bronze Age.

The Ancient Near Eastern cultures are well within the historical era:

The first half of the mil ...

has to be reconstructed on the basis of the ancient Greek dialects

Ancient Greek in classical antiquity, before the development of the common Koine Greek of the Hellenistic period, was divided into several varieties.

Most of these varieties are known only from inscriptions, but a few of them, principally Aeolic ...

, as they presented themselves centuries later and are therefore subject to some uncertainties. There were at least two migrations, the first being the Ionians

The Ionians (; el, Ἴωνες, ''Íōnes'', singular , ''Íōn'') were one of the four major tribes that the Greeks considered themselves to be divided into during the ancient period; the other three being the Dorians, Aeolians, and Achae ...

and Achaeans, which resulted in Mycenaean Greece

Mycenaean Greece (or the Mycenaean civilization) was the last phase of the Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in ...

by the 16th century BC, and the second, the Dorian invasion, around the 11th century BC, displacing the Arcadocypriot dialects, which descended from the Mycenaean period. Both migrations occur at incisive periods, the Mycenaean at the transition to the Late Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

and the Doric at the Bronze Age collapse

The Late Bronze Age collapse was a time of widespread societal collapse during the 12th century BC, between c. 1200 and 1150. The collapse affected a large area of the Eastern Mediterranean (North Africa and Southeast Europe) and the Near Ea ...

.

Mycenaean

In 1600 BC, the Mycenaean Greeks borrowed from theMinoan civilization

The Minoan civilization was a Bronze Age Aegean civilization on the island of Crete and other Aegean Islands, whose earliest beginnings were from 3500BC, with the complex urban civilization beginning around 2000BC, and then declining from 1450BC ...

its syllabic writing system (Linear A

Linear A is a writing system that was used by the Minoans of Crete from 1800 to 1450 BC to write the hypothesized Minoan language or languages. Linear A was the primary script used in palace and religious writings of the Minoan civil ...

) and developed their own syllabic script known as Linear B

Linear B was a syllabic script used for writing in Mycenaean Greek, the earliest attested form of Greek. The script predates the Greek alphabet by several centuries. The oldest Mycenaean writing dates to about 1400 BC. It is descended from ...

, providing the first and oldest written evidence of Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

. The Mycenaeans quickly penetrated the Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea ; tr, Ege Denizi (Greek language, Greek: Αιγαίο Πέλαγος: "Egéo Pélagos", Turkish language, Turkish: "Ege Denizi" or "Adalar Denizi") is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It ...

and, by the 15th century BC, had reached Rhodes

Rhodes (; el, Ρόδος , translit=Ródos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the So ...

, Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, and ...

, Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is geo ...

and the shores of Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

.

Around 1200 BC, the Dorians

The Dorians (; el, Δωριεῖς, ''Dōrieîs'', singular , ''Dōrieús'') were one of the four major ethnic groups into which the Hellenes (or Greeks) of Classical Greece divided themselves (along with the Aeolians, Achaeans, and Ionians) ...

, another Greek-speaking people, followed from Epirus

sq, Epiri rup, Epiru

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = Historical region

, image_map = Epirus antiquus tabula.jpg

, map_alt =

, map_caption = Map of ancient Epirus by Heinrich ...

. Older historical research often proposed Dorian invasion caused the collapse of the Mycenaean civilization

Mycenaean Greece (or the Mycenaean civilization) was the last phase of the Bronze Age in Ancient Greece, spanning the period from approximately 1750 to 1050 BC.. It represents the first advanced and distinctively Greek civilization in mainland ...

, but this narrative has been abandoned in all contemporary research. It is likely that one of the factors which contributed to the Mycenaean palatial collapse was linked to raids by groups known in historiography as the "Sea Peoples

The Sea Peoples are a hypothesized seafaring confederation that attacked ancient Egypt and other regions in the East Mediterranean prior to and during the Late Bronze Age collapse (1200–900 BCE).. Quote: "First coined in 1881 by the Fren ...

" who sailed into the eastern Mediterranean around 1180 BC. The Dorian invasion was followed by a poorly attested period of migrations, appropriately called the Greek Dark Ages

The term Greek Dark Ages refers to the period of Greek history from the end of the Mycenaean palatial civilization, around 1100 BC, to the beginning of the Archaic age, around 750 BC. Archaeological evidence shows a widespread collaps ...

, but by 800 BC the landscape of Archaic and Classical Greece

Classical Greece was a period of around 200 years (the 5th and 4th centuries BC) in Ancient Greece,The "Classical Age" is "the modern designation of the period from about 500 B.C. to the death of Alexander the Great in 323 B.C." ( Thomas R. Marti ...

was discernible..

The Greeks of classical antiquity idealized their Mycenaean ancestors and the Mycenaean period as a glorious era of heroes, closeness of the gods and material wealth. The Homeric Epics

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

(i.e. ''Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; grc, Ἰλιάς, Iliás, ; "a poem about Ilium") is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Odysse ...

'' and ''Odyssey

The ''Odyssey'' (; grc, Ὀδύσσεια, Odýsseia, ) is one of two major Ancient Greek literature, ancient Greek Epic poetry, epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by moder ...

'') were especially and generally accepted as part of the Greek past and it was not until the time of Euhemerism

Euhemerism () is an approach to the interpretation of mythology in which mythological accounts are presumed to have originated from real historical events or personages. Euhemerism supposes that historical accounts become myths as they are exagge ...

that scholars began to question Homer's historicity. As part of the Mycenaean heritage that survived, the names of the gods and goddesses of Mycenaean Greece (e.g. Zeus

Zeus or , , ; grc, Δῐός, ''Diós'', label=Genitive case, genitive Aeolic Greek, Boeotian Aeolic and Doric Greek#Laconian, Laconian grc-dor, Δεύς, Deús ; grc, Δέος, ''Déos'', label=Genitive case, genitive el, Δίας, ''D� ...

, Poseidon

Poseidon (; grc-gre, Ποσειδῶν) was one of the Twelve Olympians in ancient Greek religion and myth, god of the sea, storms, earthquakes and horses.Burkert 1985pp. 136–139 In pre-Olympian Bronze Age Greece, he was venerated as a ch ...

and Hades

Hades (; grc-gre, ᾍδης, Háidēs; ), in the ancient Greek religion and myth, is the god of the dead and the king of the underworld, with which his name became synonymous. Hades was the eldest son of Cronus and Rhea, although this also ...

) became major figures of the Olympian Pantheon

Olympian or Olympians may refer to:

Religion

* Twelve Olympians, the principal gods and goddesses in ancient Greek religion

* Olympian spirits, spirits mentioned in books of ceremonial magic

Fiction

* ''Percy Jackson & the Olympians'', fiction ...

of later antiquity.

Classical

Theethnogenesis

Ethnogenesis (; ) is "the formation and development of an ethnic group".

This can originate by group self-identification or by outside identification.

The term ''ethnogenesis'' was originally a mid-19th century neologism that was later introdu ...

of the Greek nation is linked to the development of Pan-Hellenism in the 8th century BC. According to some scholars, the foundational event was the Olympic Games

The modern Olympic Games or Olympics (french: link=no, Jeux olympiques) are the leading international sporting events featuring summer and winter sports competitions in which thousands of athletes from around the world participate in a var ...

in 776 BC, when the idea of a common Hellenism among the Greek tribes was first translated into a shared cultural experience and Hellenism was primarily a matter of common culture. The works of Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

(i.e. ''Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; grc, Ἰλιάς, Iliás, ; "a poem about Ilium") is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Odysse ...

'' and ''Odyssey

The ''Odyssey'' (; grc, Ὀδύσσεια, Odýsseia, ) is one of two major Ancient Greek literature, ancient Greek Epic poetry, epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by moder ...

'') and Hesiod

Hesiod (; grc-gre, Ἡσίοδος ''Hēsíodos'') was an ancient Greek poet generally thought to have been active between 750 and 650 BC, around the same time as Homer. He is generally regarded by western authors as 'the first written poet i ...

(i.e. ''Theogony

The ''Theogony'' (, , , i.e. "the genealogy or birth of the gods") is a poem by Hesiod (8th–7th century BC) describing the origins and genealogies of the Greek gods, composed . It is written in the Epic dialect of Ancient Greek and contains 10 ...

'') were written in the 8th century BC, becoming the basis of the national religion, ethos, history and mythology. The Oracle of Apollo at Delphi was established in this period.

The classical period of Greek civilization covers a time spanning from the early 5th century BC to the death of Alexander the Great

The death of Alexander the Great and subsequent related events have been the subjects of debates. According to a Babylonian astronomical diaries, Babylonian astronomical diary, Alexander died in the palace of Nebuchadnezzar II in Babylon betwee ...

, in 323 BC (some authors prefer to split this period into "Classical", from the end of the Greco-Persian Wars

The Greco-Persian Wars (also often called the Persian Wars) were a series of conflicts between the Achaemenid Empire and Greek city-states that started in 499 BC and lasted until 449 BC. The collision between the fractious political world of the ...

to the end of the Peloponnesian War, and "Fourth Century", up to the death of Alexander). It is so named because it set the standards by which Greek civilization would be judged in later eras. The Classical period is also described as the "Golden Age" of Greek civilization, and its art, philosophy, architecture and literature would be instrumental in the formation and development of Western culture.

While the Greeks of the classical era understood themselves to belong to a common Hellenic genos

In ancient Greece, a ''genos'' ( Greek: γένος, "race, stock, kin", plural γένη ''genē'') was a social group claiming common descent, referred to by a single name (see also Sanskrit " Gana"). Most ''gene'' were composed of noble families& ...

, their first loyalty was to their city and they saw nothing incongruous about warring, often brutally, with other Greek city-states

A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world since the dawn of history, including cities such as ...

. The Peloponnesian War

The Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC) was an ancient Greek war fought between Athens and Sparta and their respective allies for the hegemony of the Greek world. The war remained undecided for a long time until the decisive intervention of th ...

, the large scale civil war between the two most powerful Greek city-states Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

and Sparta

Sparta ( Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referre ...

and their allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

, left both greatly weakened.

Most of the feuding Greek city-states were, in some scholars' opinions, united by force under the banner of

Most of the feuding Greek city-states were, in some scholars' opinions, united by force under the banner of Philip

Philip, also Phillip, is a male given name, derived from the Greek (''Philippos'', lit. "horse-loving" or "fond of horses"), from a compound of (''philos'', "dear", "loved", "loving") and (''hippos'', "horse"). Prominent Philips who popularize ...

's and Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, wikt:Ἀλέξανδρος, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Maced ...

's Pan-Hellenic ideals, though others might generally opt, rather, for an explanation of " Macedonian conquest for the sake of conquest" or at least conquest for the sake of riches, glory and power and view the "ideal" as useful propaganda directed towards the city-states.

In any case, Alexander's toppling of the Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Based in Western Asia, it was contemporarily the largest em ...

, after his victories at the battles of the Granicus, Issus and Gaugamela

The Battle of Gaugamela (; grc, Γαυγάμηλα, translit=Gaugámela), also called the Battle of Arbela ( grc, Ἄρβηλα, translit=Árbela), took place in 331 BC between the forces of the Army of Macedon under Alexander the Great a ...

, and his advance as far as modern-day Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

and Tajikistan

Tajikistan (, ; tg, Тоҷикистон, Tojikiston; russian: Таджикистан, Tadzhikistan), officially the Republic of Tajikistan ( tg, Ҷумҳурии Тоҷикистон, Jumhurii Tojikiston), is a landlocked country in Centr ...

, provided an important outlet for Greek culture, via the creation of colonies and trade routes along the way. While the Alexandrian empire did not survive its creator's death intact, the cultural implications of the spread of Hellenism across much of the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

and Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an area ...

were to prove long lived as Greek became the ''lingua franca

A lingua franca (; ; for plurals see ), also known as a bridge language, common language, trade language, auxiliary language, vehicular language, or link language, is a language systematically used to make communication possible between groups ...

'', a position it retained even in Roman times

In modern historiography, ancient Rome refers to Roman civilisation from the founding of the city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD. It encompasses the Roman Kingdom (753–509 BC ...

. Many Greeks settled in Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

cities like Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

, Antioch

Antioch on the Orontes (; grc-gre, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου, ''Antiókheia hē epì Oróntou'', Learned ; also Syrian Antioch) grc-koi, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου; or Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπ� ...

and Seleucia

Seleucia (; grc-gre, Σελεύκεια), also known as or , was a major Mesopotamian city of the Seleucid empire. It stood on the west bank of the Tigris River, within the present-day Baghdad Governorate in Iraq.

Name

Seleucia ( grc-gre, Σ ...

.

Hellenistic

The

The Hellenistic civilization

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in History of the Mediterranean region, Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as sig ...

was the next period of Greek civilization, the beginnings of which are usually placed at Alexander's death. This Hellenistic age

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in 31 ...

, so called because it saw the partial Hellenization

Hellenization (other British spelling Hellenisation) or Hellenism is the adoption of Greek culture, religion, language and identity by non-Greeks. In the ancient period, colonization often led to the Hellenization of indigenous peoples; in the ...

of many non-Greek cultures, extending all the way into India and Bactria, both of which maintained Greek cultures and governments for centuries. The end is often placed around conquest of Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

by Rome in 30 BC, although the Indo-Greek kingdoms lasted for a few more decades.

This age saw the Greeks move towards larger cities and a reduction in the importance of the city-state. These larger cities were parts of the still larger Kingdoms of the Diadochi. Greeks, however, remained aware of their past, chiefly through the study of the works of Homer and the classical authors.. An important factor in maintaining Greek identity was contact with ''barbarian

A barbarian (or savage) is someone who is perceived to be either Civilization, uncivilized or primitive. The designation is usually applied as a generalization based on a popular stereotype; barbarians can be members of any nation judged by som ...

'' (non-Greek) peoples, which was deepened in the new cosmopolitan environment of the multi-ethnic Hellenistic kingdoms. This led to a strong desire among Greeks to organize the transmission of the Hellenic ''paideia

''Paideia'' (also spelled ''paedeia'') ( /paɪˈdeɪə/; Greek: παιδεία, ''paideía'') referred to the rearing and education of the ideal member of the ancient Greek polis or state. These educational ideals later spread to the Greco-Roman ...

'' to the next generation. Greek science, technology and mathematics are generally considered to have reached their peak during the Hellenistic period.

In the Indo-Greek

The Indo-Greek Kingdom, or Graeco-Indian Kingdom, also known historically as the Yavana Kingdom (Yavanarajya), was a Hellenistic period, Hellenistic-era Ancient Greece, Greek kingdom covering various parts of Afghanistan and the northwestern r ...

and Greco-Bactrian

The Bactrian Kingdom, known to historians as the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom or simply Greco-Bactria, was a Hellenistic-era Greek state, and along with the Indo-Greek Kingdom, the easternmost part of the Hellenistic world in Central Asia and the India ...

kingdoms, Greco-Buddhism

Greco-Buddhism, or Graeco-Buddhism, is the cultural syncretism between Hellenistic culture and Buddhism, which developed between the fourth century BC and the fifth century AD in Gandhara, in present-day north-western Pakistan and parts of nort ...

was spreading and Greek missionaries would play an important role in propagating it to China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

. Further east, the Greeks of Alexandria Eschate became known to the Chinese people

The Chinese people or simply Chinese, are people or ethnic groups identified with China, usually through ethnicity, nationality, citizenship, or other affiliation.

Chinese people are known as Zhongguoren () or as Huaren () by speakers of s ...

as the Dayuan

Dayuan (or Tayuan; ; Middle Chinese ''dâiC-jwɐn'' < LHC: ''dɑh-ʔyɑn'') is the Chinese .

During most of the Middle Ages, the Byzantine Greeks self-identified as ''Rhōmaîoi'' (, "Romans", meaning

During most of the Middle Ages, the Byzantine Greeks self-identified as ''Rhōmaîoi'' (, "Romans", meaning

Following the

Following the  The roots of Greek success in the Ottoman Empire can be traced to the Greek tradition of education and commerce exemplified in the

The roots of Greek success in the Ottoman Empire can be traced to the Greek tradition of education and commerce exemplified in the

The terms used to define Greekness have varied throughout history but were never limited or completely identified with membership to a Greek state.

The terms used to define Greekness have varied throughout history but were never limited or completely identified with membership to a Greek state.

Greeks and Greek-speakers have used different names to refer to themselves collectively. The term (Ἀχαιοί) is one of the collective names for the Greeks in

Greeks and Greek-speakers have used different names to refer to themselves collectively. The term (Ἀχαιοί) is one of the collective names for the Greeks in

"From when Hellen

1.14

"The deluge in the time of Deucalion, for instance took place chiefly in the Greek world and in it especially about ancient Hellas, the country about Dodona and the Achelous." In the Homeric tradition, the Selloi were the priests of Dodonian Zeus. In the

The most obvious link between modern and ancient Greeks is their language, which has a documented tradition from at least the 14th century BC to the present day, albeit with a break during the

The most obvious link between modern and ancient Greeks is their language, which has a documented tradition from at least the 14th century BC to the present day, albeit with a break during the

The total number of Greeks living outside Greece and Cyprus today is a contentious issue. Where census figures are available, they show around 3 million Greeks outside

The total number of Greeks living outside Greece and Cyprus today is a contentious issue. Where census figures are available, they show around 3 million Greeks outside

In ancient times, the trading and colonizing activities of the Greek tribes and city states spread the Greek culture, religion and language around the Mediterranean and Black Sea basins, especially in Sicily and southern Italy (also known as

In ancient times, the trading and colonizing activities of the Greek tribes and city states spread the Greek culture, religion and language around the Mediterranean and Black Sea basins, especially in Sicily and southern Italy (also known as

During and after the

During and after the

Most Greeks speak the

Most Greeks speak the

Most Greeks are

Most Greeks are

Greek art has a long and varied history. Greeks have contributed to the visual, literary and performing arts.. In the West,

Greek art has a long and varied history. Greeks have contributed to the visual, literary and performing arts.. In the West,

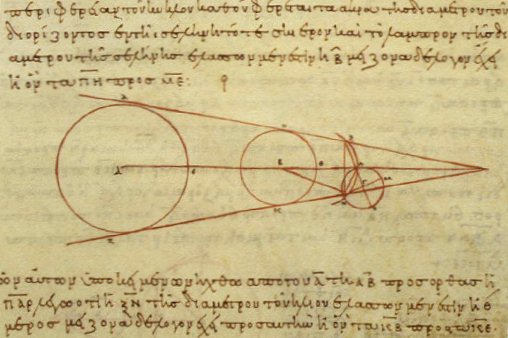

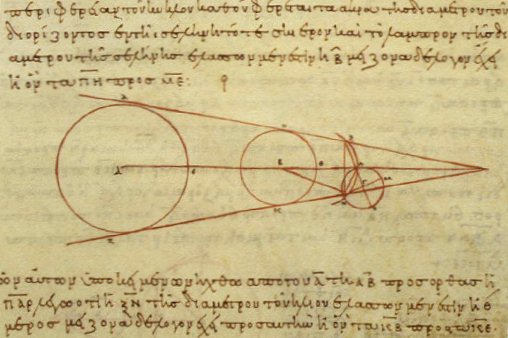

The Greeks of the Classical and Hellenistic eras made seminal contributions to science and philosophy, laying the foundations of several western scientific traditions, such as

The Greeks of the Classical and Hellenistic eras made seminal contributions to science and philosophy, laying the foundations of several western scientific traditions, such as

The most widely used symbol is the

The most widely used symbol is the

The traditional Greek homelands have been the Greek peninsula and the Aegean Sea,

The traditional Greek homelands have been the Greek peninsula and the Aegean Sea,

Genetic studies using multiple autosomal gene markers, Y chromosomal DNA

Genetic studies using multiple autosomal gene markers, Y chromosomal DNA

World Council of Hellenes Abroad (SAE)

Umbrella Diaspora Organization ;Religious

Ecumenical Patriarchate of ConstantinopleGreek Orthodox Patriarchate of AlexandriaGreek Orthodox Patriarchate of AntiochGreek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem

Church of CyprusChurch of Greece

;Academic

Transnational Communities Programme at the University of Oxford

, includes papers on the

Greeks on Greekness

The Construction and Uses of the Greek Past among Greeks under the Roman Empire. *The Modern Greek Studies Association is a scholarly organization for modern Greek studies in North America, which publishes the Journal of Modern Greek Studies.

Got Greek? Next Generation National Research StudyWaterloo Institute for Hellenistic Studies

;Trade organizations

Hellenic Canadian Board of TradeHellenic Canadian Lawyers AssociationHellenic-American Chamber of CommerceHellenic-Argentine Chamber of Industry and Commerce (C.I.C.H.A.)

;Charitable organizations

AHEPA

– American Hellenic Educational Progressive Association

Hellenic Heritage FoundationHellenic Home for the AgedHellenic Hope Center

{{good article Ethnic groups in Greece Greek people, Ancient peoples of Europe Indo-European peoples Modern Indo-European peoples

Roman Empire

Between 168 BC and 30 BC, the entire Greek world was conquered by Rome, and almost all of the world's Greek speakers lived as citizens or subjects of the Roman Empire. Despite their military superiority, the Romans admired and became heavily influenced by the achievements of Greek culture, henceHorace

Quintus Horatius Flaccus (; 8 December 65 – 27 November 8 BC), known in the English-speaking world as Horace (), was the leading Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus (also known as Octavian). The rhetorician Quintilian regarded his ' ...

's famous statement: ''Graecia capta ferum victorem cepit'' ("Greece, although captured, took its wild conqueror captive"). In the centuries following the Roman conquest of the Greek world, the Greek and Roman cultures merged into a single Greco-Roman

The Greco-Roman civilization (; also Greco-Roman culture; spelled Graeco-Roman in the Commonwealth), as understood by modern scholars and writers, includes the geographical regions and countries that culturally—and so historically—were di ...

culture.

In the religious sphere, this was a period of profound change. The spiritual revolution that took place, saw a waning of the old Greek religion, whose decline beginning in the 3rd century BC continued with the introduction of new religious movements from the East. The cults of deities like Isis

Isis (; ''Ēse''; ; Meroitic: ''Wos'' 'a''or ''Wusa''; Phoenician: 𐤀𐤎, romanized: ʾs) was a major goddess in ancient Egyptian religion whose worship spread throughout the Greco-Roman world. Isis was first mentioned in the Old Kingd ...

and Mithra

Mithra ( ae, ''Miθra'', peo, 𐎷𐎰𐎼 ''Miça'') commonly known as Mehr, is the Iranian deity of covenant, light, oath, justice and the sun. In addition to being the divinity of contracts, Mithra is also a judicial figure, an all-seeing ...

were introduced into the Greek world. Greek-speaking communities of the Hellenized East were instrumental in the spread of early Christianity in the 2nd and 3rd centuries, and Christianity's early leaders and writers (notably Saint Paul

Paul; grc, Παῦλος, translit=Paulos; cop, ⲡⲁⲩⲗⲟⲥ; hbo, פאולוס השליח (previously called Saul of Tarsus;; ar, بولس الطرسوسي; grc, Σαῦλος Ταρσεύς, Saũlos Tarseús; tr, Tarsuslu Pavlus; ...

) were generally Greek-speaking, though none were from Greece proper. However, Greece itself had a tendency to cling to paganism and was not one of the influential centers of early Christianity: in fact, some ancient Greek religious practices remained in vogue until the end of the 4th century, with some areas such as the southeastern Peloponnese remaining pagan until well into the mid-Byzantine 10th century AD. The region of Tsakonia

Tsakonia ( ell, Τσακωνιά) or the Tsakonian region () refers to the small area in the eastern Peloponnese where the Tsakonian language is spoken, in the area surrounding 13 towns, villages and hamlets located around Pera Melana in Arcadia. I ...

remained pagan until the ninth century and as such its inhabitants were referred to as ''Hellenes'', in the sense of being pagan, by their Christianized Greek brethren in mainstream Byzantine society.

While ethnic distinctions still existed in the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterr ...

, they became secondary to religious considerations, and the renewed empire used Christianity as a tool to support its cohesion and promote a robust Roman national identity. From the early centuries of the Common Era

Common Era (CE) and Before the Common Era (BCE) are year notations for the Gregorian calendar (and its predecessor, the Julian calendar), the world's most widely used calendar era. Common Era and Before the Common Era are alternatives to the or ...

, the Greeks self-identified as Romans (Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

: ''Rhōmaîoi''). By that time, the name ''Hellenes'' denoted pagans but was revived as an ethnonym in the 11th century..

Middle Ages

During most of the Middle Ages, the Byzantine Greeks self-identified as ''Rhōmaîoi'' (, "Romans", meaning

During most of the Middle Ages, the Byzantine Greeks self-identified as ''Rhōmaîoi'' (, "Romans", meaning citizens

Citizenship is a "relationship between an individual and a state to which the individual owes allegiance and in turn is entitled to its protection".

Each state determines the conditions under which it will recognize persons as its citizens, and ...

of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterr ...

), a term which in the Greek language

Greek ( el, label=Modern Greek, Ελληνικά, Elliniká, ; grc, Ἑλληνική, Hellēnikḗ) is an independent branch of the Indo-European family of languages, native to Greece, Cyprus, southern Italy (Calabria and Salento), southern Al ...

had become synonymous with Christian Greeks.: "Roman, Greek (if not used in its sense of 'pagan') and Christian became synonymous terms, counterposed to 'foreigner', 'barbarian', 'infidel'. The citizens of the Empire, now predominantly of Greek ethnicity and language, were often called simply ό χριστώνυμος λαός the people who bear Christ's name'

''The'' () is a grammatical article in English, denoting persons or things already mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in English. ''The'' is the ...

" The Latinizing term ''Graikoí'' (Γραικοί, "Greeks") was also used, though its use was less common, and nonexistent in official Byzantine political correspondence, prior to the Fourth Crusade of 1204. The Eastern Roman Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

(today conventionally named the ''Byzantine Empire'', a name not used during its own time) became increasingly influenced by Greek culture after the 7th century when Emperor Heraclius

Heraclius ( grc-gre, Ἡράκλειος, Hērákleios; c. 575 – 11 February 641), was List of Byzantine emperors, Eastern Roman emperor from 610 to 641. His rise to power began in 608, when he and his father, Heraclius the Elder, the Exa ...

( 610–641 AD) decided to make Greek the empire's official language.. Although the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

recognized the Eastern Empire's claim to the Roman legacy for several centuries, after Pope Leo III

Pope Leo III (died 12 June 816) was bishop of Rome and ruler of the Papal States from 26 December 795 to his death. Protected by Charlemagne from the supporters of his predecessor, Adrian I, Leo subsequently strengthened Charlemagne's position b ...

crowned Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first Holy ...

, king of the Franks

The Franks ( la, Franci or ) were a group of Germanic peoples whose name was first mentioned in 3rd-century Roman sources, and associated with tribes between the Lower Rhine and the Ems River, on the edge of the Roman Empire.H. Schutz: Tools, ...

, as the " Roman Emperor" on 25 December 800, an act which eventually led to the formation of the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a Polity, political entity in Western Europe, Western, Central Europe, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, dissolution i ...

, the Latin West started to favour the Franks and began to refer to the Eastern Roman Empire largely as the ''Empire of the Greeks'' (''Imperium Graecorum''). While this Latin term for the ancient ''Hellenes

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Cyprus, Albania, Italy, Turkey, Egypt, and, to a lesser extent, other ...

'' could be used neutrally, its use by Westerners from the 9th century onwards in order to challenge Byzantine claims to ancient Roman

In modern historiography, ancient Rome refers to Roman civilisation from the founding of the city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD. It encompasses the Roman Kingdom (753–509 BC ...

heritage rendered it a derogatory exonym

An endonym (from Greek: , 'inner' + , 'name'; also known as autonym) is a common, ''native'' name for a geographical place, group of people, individual person, language or dialect, meaning that it is used inside that particular place, group, ...

for the Byzantines who barely used it, mostly in contexts relating to the West, such as texts relating to the Council of Florence

The Council of Florence is the seventeenth ecumenical council recognized by the Catholic Church, held between 1431 and 1449. It was convoked as the Council of Basel by Pope Martin V shortly before his death in February 1431 and took place in ...

, to present the Western viewpoint. Additionally, among the Germanic and the Slavic peoples, the ''Rhōmaîoi'' were just called Greeks.

There are three schools of thought regarding this Byzantine Roman identity in contemporary Byzantine scholarship: The first considers "Romanity" the mode of self-identification of the subjects of a multi-ethnic empire at least up to the 12th century, where the average subject identified as Roman; a perennialist approach, which views Romanity as the medieval expression of a continuously existing Greek nation; while a third view considers the eastern Roman identity as a pre-modern national identity. The Byzantine Greeks' essential values were drawn from both Christianity and the Homeric tradition of ancient Greece..

A distinct Greek identity re-emerged in the 11th century in educated circles and became more forceful after the fall of Constantinople to the Crusaders of the Fourth Crusade

The Fourth Crusade (1202–1204) was a Latin Christian armed expedition called by Pope Innocent III. The stated intent of the expedition was to recapture the Muslim-controlled city of Jerusalem, by first defeating the powerful Egyptian Ayyubid S ...

in 1204. In the Empire of Nicaea

The Empire of Nicaea or the Nicene Empire is the conventional historiographic name for the largest of the three Byzantine Greek''A Short history of Greece from early times to 1964'' by W. A. Heurtley, H. C. Darby, C. W. Crawley, C. M. Woodhouse ...

, a small circle of the elite used the term "Hellene" as a term of self-identification. For example, in a letter to Pope Gregory IX

Pope Gregory IX ( la, Gregorius IX; born Ugolino di Conti; c. 1145 or before 1170 – 22 August 1241) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 19 March 1227 until his death in 1241. He is known for issuing the '' Decre ...

, the Nicaean emperor John III Doukas Vatatzes

John III Doukas Vatatzes, Latinized as Ducas Vatatzes ( el, Ιωάννης Δούκας Βατάτζης, ''Iōannēs Doukas Vatatzēs'', c. 1192 – 3 November 1254), was Emperor of Nicaea from 1221 to 1254. He was succeeded by his son, known ...

(r. 1221–1254) claimed to have received the gift of royalty from Constantine the Great, and put emphasis on his "Hellenic" descent, exalting the wisdom of the Greek people. After the Byzantines recaptured Constantinople, however, in 1261, ''Rhomaioi'' became again dominant as a term for self-description and there are few traces of ''Hellene'' (Έλληνας), such as in the writings of George Gemistos Plethon

Georgios Gemistos Plethon ( el, Γεώργιος Γεμιστός Πλήθων; la, Georgius Gemistus Pletho /1360 – 1452/1454), commonly known as Gemistos Plethon, was a Greek scholar and one of the most renowned philosophers of the late Byza ...

, who abandoned Christianity and in whose writings culminated the secular tendency in the interest in the classical past. However, it was the combination of Orthodox Christianity

Orthodoxy (from Ancient Greek, Greek: ) is adherence to correct or accepted creeds, especially in religion.

Orthodoxy within Christianity refers to acceptance of the doctrines defined by various creeds and ecumenical councils in Late antiquity, A ...

with a specifically Greek identity that shaped the Greeks' notion of themselves in the empire's twilight years. In the twilight years of the Byzantine Empire, prominent Byzantine personalities proposed referring to the Byzantine Emperor as the "Emperor of the Hellenes". These largely rhetorical expressions of Hellenic identity were confined within intellectual circles, but were continued by Byzantine intellectuals who participated in the Italian Renaissance

The Italian Renaissance ( it, Rinascimento ) was a period in Italian history covering the 15th and 16th centuries. The period is known for the initial development of the broader Renaissance culture that spread across Europe and marked the trans ...

.

The interest in the Classical Greek heritage was complemented by a renewed emphasis on Greek Orthodox

The term Greek Orthodox Church (Greek language, Greek: Ἑλληνορθόδοξη Ἐκκλησία, ''Ellinorthódoxi Ekklisía'', ) has two meanings. The broader meaning designates "the Eastern Orthodox Church, entire body of Orthodox (Chalced ...

identity, which was reinforced in the late Medieval and Ottoman Greeks' links with their fellow Orthodox Christians in the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

. These were further strengthened following the fall of the Empire of Trebizond

The Empire of Trebizond, or Trapezuntine Empire, was a monarchy and one of three successor rump states of the Byzantine Empire, along with the Despotate of the Morea and the Principality of Theodoro, that flourished during the 13th through to t ...

in 1461, after which and until the second Russo-Turkish War of 1828–29 hundreds of thousands of Pontic Greeks

The Pontic Greeks ( pnt, Ρωμαίοι, Ρωμίοι, tr, Pontus Rumları or , el, Πόντιοι, or , , ka, პონტოელი ბერძნები, ), also Pontian Greeks or simply Pontians, are an ethnically Greek group in ...

fled or migrated from the Pontic Alps

The Pontic Mountains or Pontic Alps ( Turkish: ''Kuzey Anadolu Dağları'', meaning North Anatolian Mountains) form a mountain range in northern Anatolia, Turkey. They are also known as the ''Parhar Mountains'' in the local Turkish and Pontic Gr ...

and Armenian Highlands to southern Russia and the Russian South Caucasus

The South Caucasus, also known as Transcaucasia or the Transcaucasus, is a geographical region on the border of Eastern Europe and Western Asia, straddling the southern Caucasus Mountains. The South Caucasus roughly corresponds to modern Arme ...

(see also Greeks in Russia

Greeks have been present in what is now southern Russia from the 6th century BC; those settlers assimilated into the indigenous populations. The vast majority of contemporary Russia's Greek minority populations are descendants of Medieval Greek re ...

, Greeks in Armenia, Greeks in Georgia

The Greeks in Georgia, which in academic circles is often considered part of the broader, historic community of Pontic Greeks or—more specifically in this region—Caucasus Greeks, is estimated at between 15,000 and 20,000 people to 100,000 (15,1 ...

, and Caucasian Greeks

The Caucasus Greeks ( el, Έλληνες του Καυκάσου or more commonly , tr, Kafkas Rum), also known as the Greeks of Transcaucasia and Russian Asia Minor, are the ethnic Greeks of the North Caucasus and Transcaucasia in what is now ...

).

These Byzantine Greeks

The Byzantine Greeks were the Greek-speaking Eastern Romans of Orthodox Christianity throughout Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages. They were the main inhabitants of the lands of the Byzantine Empire (Eastern Roman Empire), of Constantinople ...

were largely responsible for the preservation of the literature of the classical era.. Byzantine grammarians were those principally responsible for carrying, in person and in writing, ancient Greek grammatical and literary studies to the West during the 15th century, giving the Italian Renaissance

The Italian Renaissance ( it, Rinascimento ) was a period in Italian history covering the 15th and 16th centuries. The period is known for the initial development of the broader Renaissance culture that spread across Europe and marked the trans ...

a major boost. The Aristotelian philosophical tradition was nearly unbroken in the Greek world for almost two thousand years, until the Fall of Constantinople

The Fall of Constantinople, also known as the Conquest of Constantinople, was the capture of the capital of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottoman Empire. The city fell on 29 May 1453 as part of the culmination of a 53-day siege which had begun o ...

in 1453.

To the Slavic world, the Byzantine Greeks contributed by the dissemination of literacy and Christianity. The most notable example of the later was the work of the two Byzantine Greek brothers, the monks Saints Cyril and Methodius

Cyril (born Constantine, 826–869) and Methodius (815–885) were two brothers and Byzantine Christian theologians and missionaries. For their work evangelizing the Slavs, they are known as the "Apostles to the Slavs".

They are credited wit ...

from the port city of Thessalonica

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its metropolitan area, and the capital of the geographic region of ...

, capital of the theme of Thessalonica

The Theme of Thessalonica ( el, Θέμα Θεσσαλονίκης) was a military-civilian province (''thema'' or theme (Byzantine administrative unit), theme) of the Byzantine Empire located in the southern Balkans, comprising varying parts of Ce ...

, who are credited today with formalizing the first Slavic alphabet.

Ottoman Empire

Following the

Following the Fall of Constantinople

The Fall of Constantinople, also known as the Conquest of Constantinople, was the capture of the capital of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottoman Empire. The city fell on 29 May 1453 as part of the culmination of a 53-day siege which had begun o ...

on 29 May 1453, many Greeks sought better employment and education opportunities by leaving for the West

West or Occident is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sunset, Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic languages, German ...

, particularly Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

, Central Europe

Central Europe is an area of Europe between Western Europe and Eastern Europe, based on a common historical, social and cultural identity. The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) between Catholicism and Protestantism significantly shaped the area' ...

, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

and Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

. Greeks are greatly credited for the European cultural revolution, later called, the Renaissance. In Greek-inhabited territory itself, Greeks came to play a leading role in the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, due in part to the fact that the central hub of the empire, politically, culturally, and socially, was based on Western Thrace

Western Thrace or West Thrace ( el, �υτικήΘράκη, '' ytikíThráki'' ; tr, Batı Trakya; bg, Западна/Беломорска Тракия, ''Zapadna/Belomorska Trakiya''), also known as Greek Thrace, is a Geography, geograp ...

and Greek Macedonia

Macedonia (; el, Μακεδονία, Makedonía ) is a geographic and former administrative region of Greece, in the southern Balkans. Macedonia is the largest and Greek geographic region, with a population of 2.36 million in 2020. It is ...

, both in Northern Greece

Northern Greece ( el, Βόρεια Ελλάδα, Voreia Ellada) is used to refer to the northern parts of Greece, and can have various definitions.

Administrative regions of Greece

Administrative term

The term "Northern Greece" is widely used ...

, and of course was centred on the mainly Greek-populated, former Byzantine capital, Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

. As a direct consequence of this situation, Greek-speakers came to play a hugely important role in the Ottoman trading and diplomatic establishment, as well as in the church. Added to this, in the first half of the Ottoman period men of Greek origin made up a significant proportion of the Ottoman army, navy, and state bureaucracy, having been levied as adolescents (along with especially Albanians

The Albanians (; sq, Shqiptarët ) are an ethnic group and nation native to the Balkan Peninsula who share a common Albanian ancestry, culture, history and language. They primarily live in Albania, Kosovo, North Macedonia, Montenegro, Se ...

and Serbs

The Serbs ( sr-Cyr, Срби, Srbi, ) are the most numerous South Slavic ethnic group native to the Balkans in Southeastern Europe, who share a common Serbian ancestry, culture, history and language.

The majority of Serbs live in their na ...

) into Ottoman service through the devshirme

Devshirme ( ota, دوشیرمه, devşirme, collecting, usually translated as "child levy"; hy, Մանկահավաք, Mankahavak′. or "blood tax"; hbs-Latn-Cyrl, Danak u krvi, Данак у крви, mk, Данок во крв, Danok vo krv ...

. Many Ottomans of Greek (or Albanian or Serb) origin were therefore to be found within the Ottoman forces which governed the provinces, from Ottoman Egypt, to Ottomans occupied Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, north and ...

and Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

, frequently as provincial governors.

For those that remained under the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

's millet system

In the Ottoman Empire, a millet (; ar, مِلَّة) was an independent court of law pertaining to "personal law" under which a confessional community (a group abiding by the laws of Muslim Sharia, Christian Canon law, or Jewish Halakha) was ...

, religion was the defining characteristic of national groups (''milletler''), so the exonym

An endonym (from Greek: , 'inner' + , 'name'; also known as autonym) is a common, ''native'' name for a geographical place, group of people, individual person, language or dialect, meaning that it is used inside that particular place, group, ...

"Greeks" (''Rumlar'' from the name Rhomaioi) was applied by the Ottomans to all members of the Orthodox Church

Orthodox Church may refer to:

* Eastern Orthodox Church

* Oriental Orthodox Churches

* Orthodox Presbyterian Church

* Orthodox Presbyterian Church of New Zealand

* State church of the Roman Empire

* True Orthodox church

See also

* Orthodox (di ...

, regardless of their language or ethnic origin. The Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

speakers were the only ethnic group to actually call themselves ''Romioi'', (as opposed to being so named by others) and, at least those educated, considered their ethnicity (''genos'') to be Hellenic. There were, however, many Greeks who escaped the second-class status of Christians inherent in the Ottoman millet

Millets () are a highly varied group of small-seeded grasses, widely grown around the world as cereal crops or grains for fodder and human food. Most species generally referred to as millets belong to the tribe Paniceae, but some millets al ...

system, according to which Muslims were explicitly awarded senior status and preferential treatment. These Greeks either emigrated, particularly to their fellow Orthodox Christian protector, the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

, or simply converted to Islam, often only very superficially and whilst remaining crypto-Christian. The most notable examples of large-scale conversion to Turkish Islam among those today defined as Greek Muslims

Greek Muslims, also known as Grecophone Muslims, are Muslims of Greek ethnic origin whose adoption of Islam (and often the Turkish language and identity) dates to the period of Ottoman rule in the southern Balkans. They consist primarily of th ...

—excluding those who had to convert as a matter of course on being recruited through the devshirme

Devshirme ( ota, دوشیرمه, devşirme, collecting, usually translated as "child levy"; hy, Մանկահավաք, Mankahavak′. or "blood tax"; hbs-Latn-Cyrl, Danak u krvi, Данак у крви, mk, Данок во крв, Danok vo krv ...

—were to be found in Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, and ...

(Cretan Turks

The Cretan Muslims ( el, Τουρκοκρητικοί or , or ; tr, Giritli, , or ; ar, أتراك كريت) or Cretan Turks were the Muslim inhabitants of the island of Crete. Their descendants settled principally in Turkey, the Dodecanese ...

), Greek Macedonia

Macedonia (; el, Μακεδονία, Makedonía ) is a geographic and former administrative region of Greece, in the southern Balkans. Macedonia is the largest and Greek geographic region, with a population of 2.36 million in 2020. It is ...

(for example among the Vallahades The Vallahades ( el, Βαλαχάδες) or Valaades ( el, Βαλαάδες) were a Muslim Macedonian Greek population who lived along the river Haliacmon in southwest Greek Macedonia, in and around Anaselitsa (modern Neapoli) and Grevena. They n ...

of western Macedonia), and among Pontic Greeks

The Pontic Greeks ( pnt, Ρωμαίοι, Ρωμίοι, tr, Pontus Rumları or , el, Πόντιοι, or , , ka, პონტოელი ბერძნები, ), also Pontian Greeks or simply Pontians, are an ethnically Greek group in ...

in the Pontic Alps

The Pontic Mountains or Pontic Alps ( Turkish: ''Kuzey Anadolu Dağları'', meaning North Anatolian Mountains) form a mountain range in northern Anatolia, Turkey. They are also known as the ''Parhar Mountains'' in the local Turkish and Pontic Gr ...

and Armenian Highlands. Several Ottoman sultans and princes were also of part Greek origin, with mothers who were either Greek concubines or princesses from Byzantine noble families, one famous example being sultan Selim the Grim ( 1517–1520), whose mother Gülbahar Hatun Gülbahar is a Turkish given name for females and may refer to:

* Gülbahar Hatun, consort of Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II, and Valide Sultan as the mother of Sultan Bayezid II

* Gülbahar Hatun, consort of Ottoman Sultan Bayezid II and the mother of ...

was a Pontic Greek

Pontic Greek ( pnt, Ποντιακόν λαλίαν, or ; el, Ποντιακή διάλεκτος, ; tr, Rumca) is a variety of Modern Greek indigenous to the Pontus region on the southern shores of the Black Sea, northeastern Anatolia, ...

.

The roots of Greek success in the Ottoman Empire can be traced to the Greek tradition of education and commerce exemplified in the

The roots of Greek success in the Ottoman Empire can be traced to the Greek tradition of education and commerce exemplified in the Phanariotes

Phanariots, Phanariotes, or Fanariots ( el, Φαναριώτες, ro, Fanarioți, tr, Fenerliler) were members of prominent Greeks, Greek families in Fener, Phanar (Φανάρι, modern ''Fener''), the chief Greek quarter of Constantinople whe ...

. It was the wealth of the extensive merchant class that provided the material basis for the intellectual revival that was the prominent feature of Greek life in the half century and more leading to the outbreak of the Greek War of Independence

The Greek War of Independence, also known as the Greek Revolution or the Greek Revolution of 1821, was a successful war of independence by Greek revolutionaries against the Ottoman Empire between 1821 and 1829. The Greeks were later assisted by ...

in 1821. Not coincidentally, on the eve of 1821, the three most important centres of Greek learning were situated in Chios

Chios (; el, Χίος, Chíos , traditionally known as Scio in English) is the fifth largest Greek island, situated in the northern Aegean Sea. The island is separated from Turkey by the Chios Strait. Chios is notable for its exports of mastic ...

, Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; grc, Σμύρνη, Smýrnē, or , ) was a Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna rose to promi ...

and Aivali, all three major centres of Greek commerce. Greek success was also favoured by Greek domination in the leadership of the Eastern Orthodox

Eastern Orthodoxy, also known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity, is one of the three main branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholicism and Protestantism.

Like the Pentarchy of the first millennium, the mainstream (or "canonical") ...

church.

Modern

The movement of the Greek enlightenment, the Greek expression of theAge of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

, contributed not only in the promotion of education, culture and printing among the Greeks, but also in the case of independence from the Ottomans

The Ottoman Turks ( tr, Osmanlı Türkleri), were the Turkic founding and sociopolitically the most dominant ethnic group of the Ottoman Empire ( 1299/1302–1922).

Reliable information about the early history of Ottoman Turks remains scarce, ...

, and the restoration of the term "Hellene". Adamantios Korais

Adamantios Korais or Koraïs ( el, Ἀδαμάντιος Κοραῆς ; la, Adamantius Coraes; french: Adamance Coray; 27 April 17486 April 1833) was a Greek scholar credited with laying the foundations of modern Greek literature and a majo ...

, probably the most important intellectual of the movement, advocated the use of the term "Hellene" (Έλληνας) or "Graikos" (Γραικός) in the place of ''Romiós'', that was seen negatively by him.

The relationship between ethnic Greek identity and Greek Orthodox

The term Greek Orthodox Church (Greek language, Greek: Ἑλληνορθόδοξη Ἐκκλησία, ''Ellinorthódoxi Ekklisía'', ) has two meanings. The broader meaning designates "the Eastern Orthodox Church, entire body of Orthodox (Chalced ...

religion continued after the creation of the modern Greek nation-state in 1830. According to the second article of the first Greek constitution

The Constitution of Greece ( el, Σύνταγμα της Ελλάδας, Syntagma tis Elladas) was created by the Fifth Revisionary Parliament of the Hellenes in 1974, after the fall of the Greek military junta and the start of the Third Hellen ...

of 1822, a Greek was defined as any native Christian resident of the Kingdom of Greece

The Kingdom of Greece ( grc, label=Greek, Βασίλειον τῆς Ἑλλάδος ) was established in 1832 and was the successor state to the First Hellenic Republic. It was internationally recognised by the Treaty of Constantinople, where ...

, a clause removed by 1840. A century later, when the Treaty of Lausanne

The Treaty of Lausanne (french: Traité de Lausanne) was a peace treaty negotiated during the Lausanne Conference of 1922–23 and signed in the Palais de Rumine, Lausanne, Switzerland, on 24 July 1923. The treaty officially settled the conflic ...

was signed between Greece