England In Middle-earth on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

England and Englishness are represented in multiple forms within

England and Englishness are represented in multiple forms within

Bree and Bombadil are still, in Shippey's words, in "The Little Kingdom", if not quite in the Shire. Bree is similar to the Shire, with its hobbit residents and the welcoming ''Prancing Pony''

Bree and Bombadil are still, in Shippey's words, in "The Little Kingdom", if not quite in the Shire. Bree is similar to the Shire, with its hobbit residents and the welcoming ''Prancing Pony''

Anglo-Saxon England appears, modified by the people's extensive use of horses in battle, in the land of Rohan. The names of the Rohirrim, the Riders of Rohan, are straightforwardly

Anglo-Saxon England appears, modified by the people's extensive use of horses in battle, in the land of Rohan. The names of the Rohirrim, the Riders of Rohan, are straightforwardly

Tolkien regretted that hardly anything was left of English mythology, so that he was forced to look at Norse and other mythologies for guidance. All the same, Tolkien did the best he could with the limited material available in '' Beowulf'', which he much admired, and other Old English sources. Old English texts gave him his ettens (as in the Ettenmoors) and ents, his elves, and his orcs; his " warg" is a cross between

Tolkien regretted that hardly anything was left of English mythology, so that he was forced to look at Norse and other mythologies for guidance. All the same, Tolkien did the best he could with the limited material available in '' Beowulf'', which he much admired, and other Old English sources. Old English texts gave him his ettens (as in the Ettenmoors) and ents, his elves, and his orcs; his " warg" is a cross between

J. R. R. Tolkien

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien (, ; 3 January 1892 – 2 September 1973) was an English writer and philologist. He was the author of the high fantasy works ''The Hobbit'' and ''The Lord of the Rings''.

From 1925 to 1945, Tolkien was the Rawlins ...

's Middle-earth writings; it appears, more or less thinly disguised, in the form of the Shire

The Shire is a region of J. R. R. Tolkien's fictional Middle-earth, described in ''The Lord of the Rings'' and other works. The Shire is an inland area settled exclusively by hobbits, the Shire-folk, largely sheltered from the goings-on in th ...

and the lands close to it; in kindly characters such as Treebeard

Treebeard, or ''Fangorn'' in Sindarin, is a tree-giant character in J. R. R. Tolkien's ''The Lord of the Rings''. He is an Ent and is said by Gandalf to be "the oldest living thing that still walks beneath the Sun upon this Middle-earth.", bo ...

, Faramir

Faramir is a fictional character in J. R. R. Tolkien's ''The Lord of the Rings''. He is introduced as the younger brother of Boromir of the Fellowship of the Ring and second son of Denethor, the Steward of Gondor.

Faramir enters the narra ...

, and Théoden

Théoden is a fictional character in J. R. R. Tolkien's fantasy novel, ''The Lord of the Rings''. The King of Rohan (Middle-earth), Rohan and Lord of the Mark or of the Riddermark, names used by the Rohirrim for their land, he appears as a suppor ...

; in its industrialised state as Isengard

In J. R. R. Tolkien's fantasy writings, Isengard () is a large fortress in Nan Curunír, the Wizard's Vale, in the western part of Middle-earth. In the fantasy world, the name of the fortress is described as a translation of Angrenost, a word ...

and Mordor

In J. R. R. Tolkien's fictional world of Middle-earth, Mordor (pronounced ; from Sindarin ''Black Land'' and Quenya ''Land of Shadow'') is the realm and base of the evil Sauron. It lay to the east of Gondor and the great river Anduin, an ...

; and as Anglo-Saxon England in Rohan. Lastly, and most pervasively, Englishness appears in the words and behaviour of the hobbits, both in ''The Hobbit

''The Hobbit, or There and Back Again'' is a children's fantasy novel by English author J. R. R. Tolkien. It was published in 1937 to wide critical acclaim, being nominated for the Carnegie Medal and awarded a prize from the ''N ...

'' and in ''The Lord of the Rings

''The Lord of the Rings'' is an epic high-fantasy novel by English author and scholar J. R. R. Tolkien. Set in Middle-earth, intended to be Earth at some time in the distant past, the story began as a sequel to Tolkien's 1937 children's b ...

''.

Tolkien has often been supposed to have spoken of wishing to create "a mythology for England"; though it seems he never used the actual phrase, commentators have found it appropriate as a description of much of his approach in creating Middle-earth

Middle-earth is the fictional setting of much of the English writer J. R. R. Tolkien's fantasy. The term is equivalent to the '' Miðgarðr'' of Norse mythology and ''Middangeard'' in Old English works, including ''Beowulf''. Middle-earth is ...

, and the legendarium

Tolkien's legendarium is the body of J. R. R. Tolkien's mythopoeic writing, unpublished in his lifetime, that forms the background to his ''The Lord of the Rings'', and which his son Christopher summarized in his compilation of ''The Silmaril ...

that lies behind ''The Silmarillion

''The Silmarillion'' () is a collection of myths and stories in varying styles by the English writer J. R. R. Tolkien. It was edited and published posthumously by his son Christopher Tolkien in 1977, assisted by the fantasy author Guy Gavri ...

''.

England

An English Shire

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

and Englishness appear in Middle-earth

Middle-earth is the fictional setting of much of the English writer J. R. R. Tolkien's fantasy. The term is equivalent to the '' Miðgarðr'' of Norse mythology and ''Middangeard'' in Old English works, including ''Beowulf''. Middle-earth is ...

, more or less thinly disguised, in the form of the Shire

The Shire is a region of J. R. R. Tolkien's fictional Middle-earth, described in ''The Lord of the Rings'' and other works. The Shire is an inland area settled exclusively by hobbits, the Shire-folk, largely sheltered from the goings-on in th ...

and the lands close to it, including Bree and Tom Bombadil

Tom Bombadil is a character in J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium. He first appeared in print in a 1934 poem called " The Adventures of Tom Bombadil", which also included ''The Lord of the Rings'' characters Goldberry (Tom's wife), Old Man Willow ...

's domain of the Old Forest and the Barrow-downs. In England, a shire is a rural administrative region, a county. Brian Rosebury likens the Shire to Tolkien's childhood home in Worcestershire in the 1890s:

The Shire is described by Tom Shippey

Thomas Alan Shippey (born 9 September 1943) is a British medievalist, a retired scholar of Middle and Old English literature as well as of modern fantasy and science fiction. He is considered one of the world's leading academic experts on the ...

as a calque upon England, a systematic construction mapping the origin of the people, its three original tribes, its two legendary founders, its organisation, its surnames, and its placenames. Others have noted easily perceived aspects such as the homely names of public houses like ''The Green Dragon''. Tolkien stated that he grew up "in "the Shire" in a pre-mechanical age".

The vanishing "Little Kingdom"

Bree and Bombadil are still, in Shippey's words, in "The Little Kingdom", if not quite in the Shire. Bree is similar to the Shire, with its hobbit residents and the welcoming ''Prancing Pony''

Bree and Bombadil are still, in Shippey's words, in "The Little Kingdom", if not quite in the Shire. Bree is similar to the Shire, with its hobbit residents and the welcoming ''Prancing Pony'' inn

Inns are generally establishments or buildings where travelers can seek lodging, and usually, food and drink. Inns are typically located in the country or along a highway; before the advent of motorized transportation they also provided accommo ...

. Bombadil represents the spirit of place

Spirit of place (or soul) refers to the unique, distinctive and cherished aspects of a place; often those celebrated by artists and writers, but also those cherished in folk tales, festivals and celebrations. It is thus as much in the invisible ...

of the Oxfordshire and Berkshire countryside, which Tolkien felt was vanishing.

Lothlórien

In J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium, Lothlórien or Lórien is the fairest realm of the Elves remaining in Middle-earth during the Third Age. It is ruled by Galadriel and Celeborn from their city of tree-houses at Caras Galadhon. The wood-elves ...

, too, carries overtones of a perfect, timeless England; Shippey analyses how Tolkien's careful account in ''The Lord of the Rings'' of the land in the angle between two rivers, the Hoarwell and the Loudwater, matches the Angle between the Flensburg Fjord and the River Schlei, the legendary origin of the Angles

The Angles ( ang, Ængle, ; la, Angli) were one of the main Germanic peoples who settled in Great Britain in the post-Roman period. They founded several kingdoms of the Heptarchy in Anglo-Saxon England. Their name is the root of the name ...

, one of the three tribes who founded England, and how the hobbits feel they have stepped "over a bridge in time".

Industrialised England

England appears in its industrialised state asIsengard

In J. R. R. Tolkien's fantasy writings, Isengard () is a large fortress in Nan Curunír, the Wizard's Vale, in the western part of Middle-earth. In the fantasy world, the name of the fortress is described as a translation of Angrenost, a word ...

and Mordor

In J. R. R. Tolkien's fictional world of Middle-earth, Mordor (pronounced ; from Sindarin ''Black Land'' and Quenya ''Land of Shadow'') is the realm and base of the evil Sauron. It lay to the east of Gondor and the great river Anduin, an ...

.

In particular, it has been suggested that the industrialized area called "the Black Country" near J. R. R. Tolkien

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien (, ; 3 January 1892 – 2 September 1973) was an English writer and philologist. He was the author of the high fantasy works ''The Hobbit'' and ''The Lord of the Rings''.

From 1925 to 1945, Tolkien was the Rawlins ...

's childhood home inspired his vision of Mordor; the name "Mordor" meant "Black Land" in Tolkien's invented language of Sindarin, and "Land of Shadow" in Quenya.

Shippey further links the fallen wizard Saruman and his industrial Isengard to "Tolkien's own childhood image of industrial ugliness ... Sarehole Mill

Sarehole Mill is a Grade II listed water mill, in an area once called Sarehole, on the River Cole in Hall Green, Birmingham, England. It is now run as a museum by the Birmingham Museums Trust. It is known for its association with J. R. R. Tol ...

, with its literally bone-grinding owner".

Anglo-Saxon England

Anglo-Saxon England appears, modified by the people's extensive use of horses in battle, in the land of Rohan. The names of the Rohirrim, the Riders of Rohan, are straightforwardly

Anglo-Saxon England appears, modified by the people's extensive use of horses in battle, in the land of Rohan. The names of the Rohirrim, the Riders of Rohan, are straightforwardly Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlers in the mid-5th c ...

, as are the terms they use and their placenames: ''Théoden'' means "king"; ''Éored'' means "troop of cavalry" and ''Éomer'' is "horse-famous", both related to ''Éoh'', "horse"; ''Eorlingas'' means "sons of Eorl"; the name of his throne-hall is ''Meduseld'', which means "mead-hall". The chapter "The King of the Golden Hall" is constructed to match the passage in the Old English poem '' Beowulf'' where the hero approaches the court of Heorot

Heorot (Old English 'hart, stag') is a mead-hall and major point of focus in the Anglo-Saxon poem ''Beowulf''. The hall serves as a seat of rule for King Hrothgar, a legendary Danish king. After the monster Grendel slaughters the inhabitants of ...

and is challenged by different guards along the way, and many of the names used come directly from there. The name of the Riders' land, the Mark, is a Latinised form of "Mercia

la, Merciorum regnum

, conventional_long_name=Kingdom of Mercia

, common_name=Mercia

, status=Kingdom

, status_text=Independent kingdom (527–879) Client state of Wessex ()

, life_span=527–918

, era= Heptarchy

, event_start=

, date_start=

, ...

", the central kingdom of Anglo-Saxon England and the region where Tolkien grew up.

Englishness

Hobbits

Englishness appears in the words and behaviour of the hobbits, throughout both ''The Hobbit

''The Hobbit, or There and Back Again'' is a children's fantasy novel by English author J. R. R. Tolkien. It was published in 1937 to wide critical acclaim, being nominated for the Carnegie Medal and awarded a prize from the ''N ...

'' and ''The Lord of the Rings

''The Lord of the Rings'' is an epic high-fantasy novel by English author and scholar J. R. R. Tolkien. Set in Middle-earth, intended to be Earth at some time in the distant past, the story began as a sequel to Tolkien's 1937 children's b ...

''. Shippey writes that from the first page of ''The Hobbit'', "the Bagginses at least were English by temperament and turn of phrase". Burns states that

Burns writes that Bilbo Baggins

Bilbo Baggins is the title character and protagonist of J. R. R. Tolkien's 1937 novel ''The Hobbit'', a supporting character in ''The Lord of the Rings'', and the fictional narrator (along with Frodo Baggins) of many of Tolkien's Middle-ear ...

, the eponymous hero of ''The Hobbit'', has acquired or rediscovered "an Englishman's northern roots. He has gained an Anglo-Saxon self-reliance and a Norseman's sense of will, and all of this is kept from excess by a Celtic sensitivity, by a love of earth, of poetry, and of simple song and cheer." She finds a similar balance in the hobbits of ''The Lord of the Rings'', Pippin

Pippin or Pepin may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Pippin (comics), ''Pippin'' (comics), a children's comic produced from 1966 to 1986

* Pippin (musical), ''Pippin'' (musical), a Broadway musical by Stephen Schwartz loosely based on the life ...

, Merry, and Sam. Frodo

Frodo Baggins is a fictional character in J. R. R. Tolkien's writings, and one of the protagonists in ''The Lord of the Rings''. Frodo is a hobbit of the Shire who inherits the One Ring from his cousin Bilbo Baggins, described familiarly a ...

's balance, though, has been destroyed by a quest beyond his strength; he still embodies some of the elements of Englishness, but lacking the simple cheerfulness of the other hobbits because of his other character traits, his Celtic sorrow and Nordic doom.

'English' characters

Kindly characters such asTreebeard

Treebeard, or ''Fangorn'' in Sindarin, is a tree-giant character in J. R. R. Tolkien's ''The Lord of the Rings''. He is an Ent and is said by Gandalf to be "the oldest living thing that still walks beneath the Sun upon this Middle-earth.", bo ...

, Faramir

Faramir is a fictional character in J. R. R. Tolkien's ''The Lord of the Rings''. He is introduced as the younger brother of Boromir of the Fellowship of the Ring and second son of Denethor, the Steward of Gondor.

Faramir enters the narra ...

, and Théoden

Théoden is a fictional character in J. R. R. Tolkien's fantasy novel, ''The Lord of the Rings''. The King of Rohan (Middle-earth), Rohan and Lord of the Mark or of the Riddermark, names used by the Rohirrim for their land, he appears as a suppor ...

exemplify Englishness with their actions and mannerisms. Treebeard's distinctive booming bass voice

Bass or Basses may refer to:

Fish

* Bass (fish), various saltwater and freshwater species

Music

* Bass (sound), describing low-frequency sound or one of several instruments in the bass range:

** Bass (instrument), including:

** Acoustic bass gu ...

with his "hrum, hroom" mannerism is indeed said by Tolkien's biographer, Humphrey Carpenter

Humphrey William Bouverie Carpenter (29 April 1946 – 4 January 2005) was an English biographer, writer, and radio broadcaster. He is known especially for his biographies of J. R. R. Tolkien and other members of the literary society the Inkl ...

, to be based directly on that of Tolkien's close friend, fellow Oxford University

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to th ...

professor and Inkling, C. S. Lewis

Clive Staples Lewis (29 November 1898 – 22 November 1963) was a British writer and Anglican lay theologian. He held academic positions in English literature at both Oxford University (Magdalen College, 1925–1954) and Cambridge Univers ...

. Marjorie Burns Marjorie Burns is a scholar of English literature, best known for her studies of J. R. R. Tolkien.

Biography

Marjorie Jean Burns was born in 1940. She gained her PhD at the University of California, Berkeley.

She is an emeritus professor of En ...

sees "a Robin Hood

Robin Hood is a legendary heroic outlaw originally depicted in English folklore and subsequently featured in literature and film. According to legend, he was a highly skilled archer and swordsman. In some versions of the legend, he is dep ...

touch" in the green-clad Faramir and his men hunting the enemy in Ithilien

Gondor is a fictional kingdom in J. R. R. Tolkien's writings, described as the greatest realm of Men in the west of Middle-earth at the end of the Third Age. The third volume of ''The Lord of the Rings'', ''The Return of the King'', is largel ...

, while in Fangorn forest, she feels that Treebeard's speech "has a comfortable English ring". Théoden's name is a direct transliteration of Old English ''þēoden'', meaning "king, prince"; he welcomes Merry, a Hobbit from the Shire, with warmth and friendship. Garry O'Connor

Garry Lawrence John O'Connor (born 7 May 1983) is a Scottish former professional footballer. He played for Hibernian, Peterhead, Lokomotiv Moscow, Barnsley, Tom Tomsk, Birmingham City, Greenock Morton and represented Scotland.

O'Connor beg ...

adds that there is a striking resemblance between the wizard Gandalf

Gandalf is a protagonist in J. R. R. Tolkien's novels '' The Hobbit'' and ''The Lord of the Rings''. He is a wizard, one of the ''Istari'' order, and the leader of the Fellowship of the Ring. Tolkien took the name "Gandalf" from the Old Nor ...

, the English actor Ian McKellen who plays Gandalf in Peter Jackson's Middle-earth films, and, based on Humphrey Carpenter

Humphrey William Bouverie Carpenter (29 April 1946 – 4 January 2005) was an English biographer, writer, and radio broadcaster. He is known especially for his biographies of J. R. R. Tolkien and other members of the literary society the Inkl ...

's biographical account, of another Englishman, Tolkien himself:

Shakespearean plot elements

Some of the plot elements in ''The Lord of the Rings

''The Lord of the Rings'' is an epic high-fantasy novel by English author and scholar J. R. R. Tolkien. Set in Middle-earth, intended to be Earth at some time in the distant past, the story began as a sequel to Tolkien's 1937 children's b ...

'' resemble William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

's, notably in '' Macbeth''. Tolkien's use of walking trees, the Huorn

Ents are a species of beings in J. R. R. Tolkien's fantasy world Middle-earth who closely resemble trees; their leader is Treebeard of Fangorn forest. Their name is derived from an Old English word for giant.

The Ents appear in ''The Lord o ...

s, to destroy the Orc-horde at the Battle of Helm's Deep

The Battle of Helm's Deep, also called the Battle of the Hornburg, is a fictional battle in J. R. R. Tolkien's ''The Lord of the Rings'' that saw the total destruction of the forces of the Wizard Saruman by the army of Rohan, assisted by a fore ...

carries a definite echo of the coming of Birnam Wood to Dunsinane Hill

Dunsinane Hill ( ) is a hill of the Sidlaws near the village of Collace in Perthshire, Scotland. It is mentioned in Shakespeare's play ''Macbeth'', in which Macbeth is informed by a supernatural being, "Macbeth shall never vanquished be, until ...

, though Tolkien admits the mythic nature of the event where Shakespeare denies it. Glorfindel

Glorfindel () is a fictional character in J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth legendarium. He is a member of the Noldor, one of the three groups of the Calaquendi or High Elves. The character and his name, which means "blond" or "golden-haired", w ...

's prophecy that the Lord of the Nazgûl

The Nazgûl (from Black Speech , "ring", and , "wraith, spirit"), introduced as Black Riders and also called Ringwraiths, Dark Riders, the Nine Riders, or simply the Nine, are fictional characters in J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth. They wer ...

would not die at the hand of any man directly reflects the Macbeth prophecy; commentators have found Tolkien's solution – he is killed by a woman and a hobbit in the Battle of the Pelennor Fields

In J. R. R. Tolkien's novel ''The Lord of the Rings'', the Battle of the Pelennor Fields () was the defence of the city of Minas Tirith by the forces of Gondor and the cavalry of its ally Rohan, against the forces of the Dark Lord Sauron from ...

– more satisfying than Shakespeare's (a man brought into the world by Caesarean section, so not exactly "born").

A mythology for England

Dedicated "to my country"

Jane Chance's 1979 book '' Tolkien's Art: 'A Mythology for England''' introduced the idea that Tolkien's Middle-earth writings were intended to form "a mythology for England". The concept was reinforced inTolkien scholarship

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien (, ; 3 January 1892 – 2 September 1973) was an English writer and philologist. He was the author of the high fantasy works ''The Hobbit'' and ''The Lord of the Rings''.

From 1925 to 1945, Tolkien was the Rawlin ...

by Shippey's ''The Road to Middle-earth

''The Road to Middle-earth: How J. R. R. Tolkien Created a New Mythology'' is a scholarly study of the Middle-earth works of J. R. R. Tolkien written by Tom Shippey and first published in 1982. The book discusses Tolkien's philology, and then e ...

: How J.R.R. Tolkien Created a New Mythology'' (1982, revised 2005). In his 2004 chapter "A Mythology for Anglo-Saxon England", Michael Drout

Michael D. C. Drout (; born 1968) is an American Professor of English and Director of the Center for the Study of the Medieval at Wheaton College. He is an author and editor specializing in Anglo-Saxon and medieval literature, science fiction and ...

states that Tolkien never used the actual phrase, though commentators have found it appropriate as a description of much of his approach in creating Middle-earth. Tolkien wrote in a letter:

Drout comments that scholars broadly agree that Tolkien "succeeded in this project". Carl F. Hostetter and Arden R. Smith state that Tolkien created the mythology initially as a home for his invented languages, discovering as he did so that he wanted to make a properly English epic, spanning England's geography, language, and mythology.

A reconstructed prehistory

Tolkien recognised that England's actual mythology, which he presumed by analogy with Norse mythology, and given the clues that remain, to have existed until Anglo-Saxon times, had been extinguished. Tolkien decided to reconstruct such a mythology, accompanied to some extent by an imagined prehistory or pseudohistory of the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes before they migrated to England. Drout analyses in detail and then summarises the imagined prehistory:

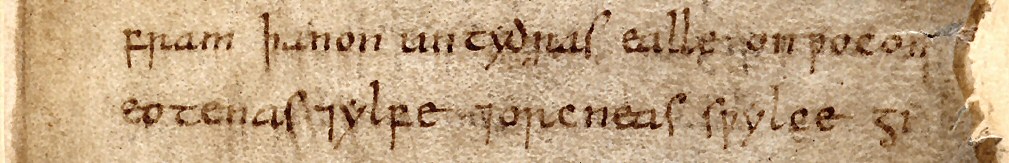

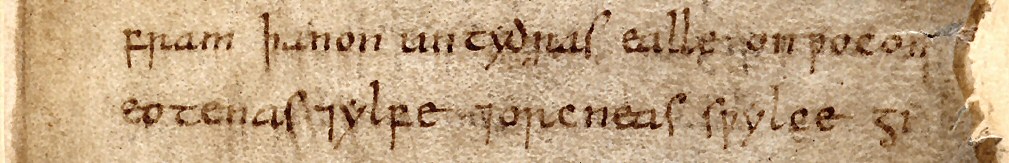

Old English heroes, races, and monsters

Tolkien regretted that hardly anything was left of English mythology, so that he was forced to look at Norse and other mythologies for guidance. All the same, Tolkien did the best he could with the limited material available in '' Beowulf'', which he much admired, and other Old English sources. Old English texts gave him his ettens (as in the Ettenmoors) and ents, his elves, and his orcs; his " warg" is a cross between

Tolkien regretted that hardly anything was left of English mythology, so that he was forced to look at Norse and other mythologies for guidance. All the same, Tolkien did the best he could with the limited material available in '' Beowulf'', which he much admired, and other Old English sources. Old English texts gave him his ettens (as in the Ettenmoors) and ents, his elves, and his orcs; his " warg" is a cross between Old Norse

Old Norse, Old Nordic, or Old Scandinavian, is a stage of development of North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants of Scandinavia and their overseas settlemen ...

''vargr'' and Old English ''wearh''. He took his ''woses'' or ''wood-woses'' (the Drúedain

The Drúedain are a fictional race of Men, living in the Drúadan Forest, in the Middle-earth legendarium created by J. R. R. Tolkien. They were counted among the Edain who made their way into Beleriand in the First Age, and were friendly to ...

) from the seeming plural ''wodwos'' in the Middle English ''Sir Gawain and the Green Knight

''Sir Gawain and the Green Knight'' is a late 14th-century chivalric romance in Middle English. The author is unknown; the title was given centuries later. It is one of the best-known Arthurian stories, with its plot combining two types of ...

'', line 721; that comes in turn from Old English ''wudu-wasa'', a singular noun. Shippey comments that

Carl Hostetter comments that all the same,

Hostetter notes that Eärendil, the mariner who ends up steering his ship across the heavens, shining as a star, was the first element of English mythology that Tolkien took into his own mythology. He was inspired by the Earendel passage in the Old English poem '' Crist I'' lines 104–108 which begins "''Eala Earendel, engla beorhtast''", "O rising light, brightest of angels". Tolkien expended considerable effort on his Old English character Ælfwine

Ælfwine (also ''Aelfwine'', ''Elfwine'') is an Old English personal name. It is composed of the elements ''ælf'' "elf" and ''wine'' "friend", continuing a hypothetical Common Germanic given name ''*albi- winiz'' which is also continued in Old Hig ...

, whom he employed as a framing device

Framing may refer to:

* Framing (construction), common carpentry work

* Framing (law), providing false evidence or testimony to prove someone guilty of a crime

* Framing (social sciences)

* Framing (visual arts), a technique used to bring the focu ...

in his ''The Book of Lost Tales

''The Book of Lost Tales'' is a collection of early stories by the English writer J. R. R. Tolkien, published as the first two volumes of Christopher Tolkien's 12-volume series '' The History of Middle-earth'', in which he presents and analys ...

''; he used a character of the same name in his abandoned time travel

Time travel is the concept of movement between certain points in time, analogous to movement between different points in space by an object or a person, typically with the use of a hypothetical device known as a time machine. Time travel is a ...

novel '' The Lost Road''.

A reflection of 20th century England

Verlyn Flieger Verlyn Flieger (born 1933) is an author, editor, and Professor Emerita in the Department of English at the University of Maryland at College Park, where she taught courses in comparative mythology, medieval literature, and the works of J. R. R. Tol ...

writes that "the Silmarillion legendarium" is both a monument to his imagination and as close as anyone has come "to a mythology that might be called English". She cites Tolkien's words in ''The Monsters and the Critics

"''Beowulf'': The Monsters and the Critics" was a 1936 lecture given by J. R. R. Tolkien on literary criticism on the Old English heroic epic poem '' Beowulf''. It was first published as a paper in the ''Proceedings of the British Academy'', ...

'' that it is "by a learned man writing of old times, who looking back on the heroism and sorrow feels in them something permanent and something symbolical". He was speaking about '' Beowulf''; she applies his words to his own writings, that his mythology was meant to provide

Flieger comments that "Tolkien's great mythological song" was conceived as the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

was changing England for ever; that it grew and took shape in a second era between the wars; and that in the form of ''The Lord of the Rings'' found an audience in yet a third era, the Cold War. She writes:

In her view, this is nearer to the vision of George Orwell's ''1984

Events

January

* January 1 – The Bornean Sultanate of Brunei gains full independence from the United Kingdom, having become a British protectorate in 1888.

* January 7 – Brunei becomes the sixth member of the Association of Southeas ...

'' than to the "furry-footed escapist fantasy that detractors of ''The Lord of the Rings'' have characterized that work as being". She states that the main function of a mythology is "to mirror a culture to itself". She follows this up by asking what the worldview encapsulated in this mythology might be. She notes that Middle-earth is influenced by existing mythologies; and that Tolkien stated that ''The Lord of the Rings'' was fundamentally Catholic. All the same, she writes, his mythos is fundamentally unlike Christianity, being "far darker"; the world is saved not by a god's sacrifice but by Eärendil and by Frodo

Frodo Baggins is a fictional character in J. R. R. Tolkien's writings, and one of the protagonists in ''The Lord of the Rings''. Frodo is a hobbit of the Shire who inherits the One Ring from his cousin Bilbo Baggins, described familiarly a ...

, in a world where "enterprise and creativity ave

''Alta Velocidad Española'' (''AVE'') is a service of high-speed rail in Spain operated by Renfe, the Spanish national railway company, at speeds of up to . As of December 2021, the Spanish high-speed rail network, on part of which the AVE s ...

gone disastrously wrong". If this is a mythology for England, she concludes, it is a caution not to try to hold on to anything, as it cannot offer salvation; Frodo was unable to let go of the One Ring

The One Ring, also called the Ruling Ring and Isildur's Bane, is a central plot element in J. R. R. Tolkien's ''The Lord of the Rings'' (1954–55). It first appeared in the earlier story ''The Hobbit'' (1937) as a magic ring that grants the ...

, and Fëanor could not with the Silmarils. A shell-shock

Shell shock is a term coined in World War I by the British psychologist Charles Samuel Myers to describe the type of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) many soldiers were afflicted with during the war (before PTSD was termed). It is a reac ...

ed England, like a battle-traumatised Frodo, did not know how to let go of empire

An empire is a "political unit" made up of several territories and peoples, "usually created by conquest, and divided between a dominant center and subordinate peripheries". The center of the empire (sometimes referred to as the metropole) ex ...

in a changed world; the advice is, she writes, sound, but as hard for nations to take as for individuals.

Notes

References

Primary

::''This list identifies each item's location in Tolkien's writings.''Secondary

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Also published in ''A Tolkien Compass

''A Tolkien Compass'', a 1975 collection of essays edited by Jared Lobdell, was one of the first books of Tolkien scholarship to be published; it was written without sight of ''The Silmarillion'', posthumously published in 1977. Some of the e ...

'' (1975) and '' The Lord of the Rings: A Reader's Companion'' (2005).

*

*

{{Lord of the Rings

Middle-earth

Themes of The Lord of the Rings

England in fiction