Eugen Sänger on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Eugen Sänger (22 September 1905 – 10 February 1964) was an

In 1928 and 1929 the Opel RAK group around Fritz von Opel had already realized the world's first manned rocket planes and demonstrated the

In 1928 and 1929 the Opel RAK group around Fritz von Opel had already realized the world's first manned rocket planes and demonstrated the

By 1954, Sänger had returned to Germany and three years later was directing a

By 1954, Sänger had returned to Germany and three years later was directing a

Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

n aerospace engineer

Aerospace engineering is the primary field of engineering concerned with the development of aircraft and spacecraft. It has two major and overlapping branches: aeronautical engineering and astronautical engineering. Avionics engineering is s ...

best known for his contributions to lifting body and ramjet

A ramjet, or athodyd (aero thermodynamic duct), is a form of airbreathing jet engine that uses the forward motion of the engine to produce thrust. Since it produces no thrust when stationary (no ram air) ramjet-powered vehicles require an a ...

technology.

Early career

Sänger was born in the former mining town ofPreßnitz

The Preßnitz ( cs, Přísečnice or ''Přísečný potok'') is a right-hand tributary of the River Zschopau in the state of Saxony in eastern Germany and in the Czech Republic. It rises in the Bohemian Ore Mountains near Horní Halže, north ...

(Přísečnice), near Komotau in Bohemia, at that time part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with t ...

. He studied civil engineering

Civil engineering is a professional engineering discipline that deals with the design, construction, and maintenance of the physical and naturally built environment, including public works such as roads, bridges, canals, dams, airports, sewa ...

at the Technical Universities of Graz

Graz (; sl, Gradec) is the capital city of the Austrian state of Styria and second-largest city in Austria after Vienna. As of 1 January 2021, it had a population of 331,562 (294,236 of whom had principal-residence status). In 2018, the popu ...

and Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

. As a student, he came in contact with Hermann Oberth's book ''Die Rakete zu den Planetenräumen'' ("By Rocket into Planetary Space"), which inspired him to change from studying civil engineering to aeronautics

Aeronautics is the science or art involved with the study, design, and manufacturing of air flight–capable machines, and the techniques of operating aircraft and rockets within the atmosphere. The British Royal Aeronautical Society identif ...

. He also joined Germany's amateur rocket movement, the '' Verein für Raumschiffahrt'' (VfR – "Society for Space Travel") which was centered on Oberth.

In 1932 Sänger became a member of the SS and was also a member of the NSDAP

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that crea ...

.

Sänger made rocket-powered flight the subject of his thesis

A thesis ( : theses), or dissertation (abbreviated diss.), is a document submitted in support of candidature for an academic degree or professional qualification presenting the author's research and findings.International Standard ISO 7144 ...

, but it was rejected by the university as too fanciful.

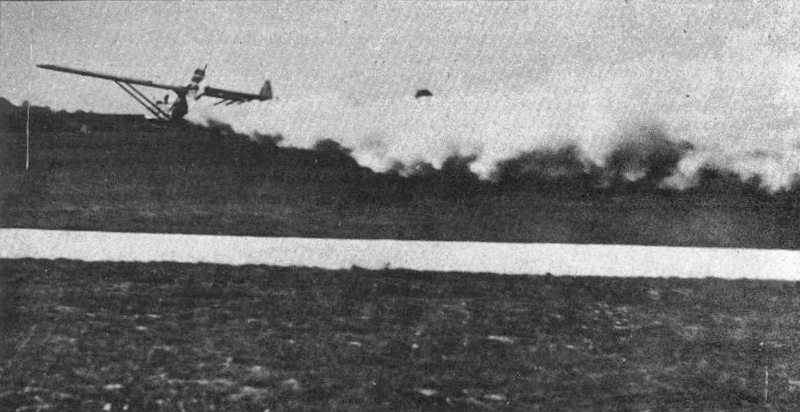

In 1928 and 1929 the Opel RAK group around Fritz von Opel had already realized the world's first manned rocket planes and demonstrated the

In 1928 and 1929 the Opel RAK group around Fritz von Opel had already realized the world's first manned rocket planes and demonstrated the Opel RAK.1

The Opel RAK.1 (also known as the Opel RAK.3) was the world's first purpose-built rocket-powered aircraft. It was designed and built by Julius Hatry under commission from Fritz von Opel, who flew it on September 30, 1929 in front of a large crowd ...

, designed by Julius Hatry and piloted by Fritz von Opel, before a huge crowd and world media in attendance to the public.

Sänger was allowed to graduate when he submitted a far more mundane paper on the statics of wing trusses. Sänger would later publish his rejected thesis under the title ''Raketenflugtechnik'' ("Rocket Flight Engineering") in 1933. In 1935 and 1936, he published articles on rocket

A rocket (from it, rocchetto, , bobbin/spool) is a vehicle that uses jet propulsion to accelerate without using the surrounding air. A rocket engine produces thrust by reaction to exhaust expelled at high speed. Rocket engines work entire ...

-powered flight for the Austrian journal ''Flug'' ("Flight"). These attracted the attention of the (RLM, or "Reich Aviation Ministry") which saw Sänger's ideas as a potential way to accomplish the goal of building a bomber that could strike the United States from Germany (the ''Amerika'' Bomber project). The RLM gave him a research institute near Braunschweig

Braunschweig () or Brunswick ( , from Low German ''Brunswiek'' , Braunschweig dialect: ''Bronswiek'') is a city in Lower Saxony, Germany, north of the Harz Mountains at the farthest navigable point of the river Oker, which connects it to the ...

and also built a liquid oxygen

Liquid oxygen—abbreviated LOx, LOX or Lox in the aerospace, submarine and gas industries—is the liquid form of molecular oxygen. It was used as the oxidizer in the first liquid-fueled rocket invented in 1926 by Robert H. Goddard, an a ...

plant and a test stand

Test(s), testing, or TEST may refer to:

* Test (assessment), an educational assessment intended to measure the respondents' knowledge or other abilities

Arts and entertainment

* ''Test'' (2013 film), an American film

* ''Test'' (2014 film), ...

for a 100 tonne

The tonne ( or ; symbol: t) is a unit of mass equal to 1000 kilograms. It is a non-SI unit accepted for use with SI. It is also referred to as a metric ton to distinguish it from the non-metric units of the short ton ( United State ...

thrust

Thrust is a reaction force

In physics, a force is an influence that can change the motion of an object. A force can cause an object with mass to change its velocity (e.g. moving from a state of rest), i.e., to accelerate. Force can al ...

engine. At the time, Sänger's hiring was opposed by Wernher von Braun

Wernher Magnus Maximilian Freiherr von Braun ( , ; 23 March 191216 June 1977) was a German and American aerospace engineer and space architect. He was a member of the Nazi Party and Allgemeine SS, as well as the leading figure in the develop ...

, who felt that his own work was being duplicated and may have seen the Austrian and his work as a threat to his own dominance of the field.

Sub-orbital bomber concept

Sänger agreed to lead a rocket development team in the '' Lüneburger Heide'' region in 1936. He gradually conceived a rocket-poweredsled

A sled, skid, sledge, or sleigh is a land vehicle that slides across a surface, usually of ice or snow. It is built with either a smooth underside or a separate body supported by two or more smooth, relatively narrow, longitudinal runners ...

that would launch a bomber

A bomber is a military combat aircraft designed to attack ground and naval targets by dropping air-to-ground weaponry (such as bombs), launching aerial torpedo, torpedoes, or deploying air-launched cruise missiles. The first use of bombs dropped ...

with its own rocket engines that would climb to the fringe of space and then skip along the upper atmosphere – not actually entering orbit

In celestial mechanics, an orbit is the curved trajectory of an object such as the trajectory of a planet around a star, or of a natural satellite around a planet, or of an artificial satellite around an object or position in space such a ...

, but able to cover vast distances in a series of sub-orbital hops. This remarkable design was called the '' Silbervogel'' ("Silverbird") and would have relied on its fuselage

The fuselage (; from the French ''fuselé'' "spindle-shaped") is an aircraft's main body section. It holds crew, passengers, or cargo. In single-engine aircraft, it will usually contain an engine as well, although in some amphibious aircraft t ...

creating lift (as a lifting body) to carry it along its sub-orbit

A sub-orbital spaceflight is a spaceflight in which the spacecraft reaches outer space, but its trajectory intersects the atmosphere or surface of the gravitating body from which it was launched, so that it will not complete one orbital re ...

al path. Sänger was assisted in this design by mathematician

A mathematician is someone who uses an extensive knowledge of mathematics in their work, typically to solve mathematical problems.

Mathematicians are concerned with numbers, data, quantity, mathematical structure, structure, space, Mathematica ...

Irene Bredt

Irene is a name derived from εἰρήνη (eirēnē), the Greek for "peace".

Irene, and related names, may refer to:

* Irene (given name)

Places

* Irene, Gauteng, South Africa

* Irene, South Dakota, United States

* Irene, Texas, United States ...

, whom he married in 1951. Sänger also designed the rocket motors that the space-plane would use, which would need to generate 1 meganewton (225,000 lbf) of thrust

Thrust is a reaction force

In physics, a force is an influence that can change the motion of an object. A force can cause an object with mass to change its velocity (e.g. moving from a state of rest), i.e., to accelerate. Force can al ...

. In this design, he was one of the first to suggest using the rocket's fuel as a way of cooling the engine, by circulating it around the rocket nozzle before burning it in the engine.

By 1942, the Reich Air Ministry

The Ministry of Aviation (german: Reichsluftfahrtministerium, abbreviated RLM) was a government department during the period of Nazi Germany (1933–45). It is also the original name of the Detlev-Rohwedder-Haus building on the Wilhelmstrass ...

canceled this project along with other more ambitious and theoretical designs in favour of concentrating on proven technologies. Sänger was sent to work for the '' Deutsche Forschungsanstalt für Segelflug'' (DFS, or "German Gliding Research Institute"). There he did important work on ramjet

A ramjet, or athodyd (aero thermodynamic duct), is a form of airbreathing jet engine that uses the forward motion of the engine to produce thrust. Since it produces no thrust when stationary (no ram air) ramjet-powered vehicles require an a ...

technology, working on projects such as the Skoda-Kauba Sk P.14 interceptor, until the end of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

.

Postwar

After the war ended, Sänger worked for theFrench government

The Government of France (French: ''Gouvernement français''), officially the Government of the French Republic (''Gouvernement de la République française'' ), exercises executive power in France. It is composed of the Prime Minister, wh ...

and in 1949 founded the '' Fédération Astronautique''. Whilst in France, he was the subject of a botched attempt by Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

agents to win him over. Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

had become intrigued by reports of the ''Silbervogel'' design and sent his son, Vasily

Vasili, Vasily, Vasilii or Vasiliy ( Russian: Василий) is a Russian masculine given name of Greek origin and corresponds to '' Basil''. It may refer to:

* Vasili I of Moscow Grand Prince from 1389–1425

*Vasili II of Moscow Grand Prince ...

, and scientist Grigori Tokaty to convince him to come to the Soviet Union, but they failed to do so. It has also been reported that Stalin instructed the NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

to kidnap him.

In 1951, he became the first President of the International Astronautical Federation. In the same year he married Dr. Irene Bredt

Irene is a name derived from εἰρήνη (eirēnē), the Greek for "peace".

Irene, and related names, may refer to:

* Irene (given name)

Places

* Irene, Gauteng, South Africa

* Irene, South Dakota, United States

* Irene, Texas, United States ...

his first assistant, a German engineer, mathematician and physicist co-credited with the design of a proposed intercontinental spaceplane/bomber.

jet propulsion

Jet propulsion is the propulsion of an object in one direction, produced by ejecting a jet of fluid in the opposite direction. By Newton's third law, the moving body is propelled in the opposite direction to the jet. Reaction engines operating on ...

research institute in Stuttgart. Between 1961 and 1963 he acted as a consultant for Junkers

Junkers Flugzeug- und Motorenwerke AG (JFM, earlier JCO or JKO in World War I, English: Junkers Aircraft and Motor Works) more commonly Junkers , was a major German aircraft and aircraft engine manufacturer. It was founded there in Dessau, ...

in designing a ramjet-powered space-plane that never left the drawing board. Sänger's other theoretical innovations during this period were proposing means of using photon

A photon () is an elementary particle that is a quantum of the electromagnetic field, including electromagnetic radiation such as light and radio waves, and the force carrier for the electromagnetic force. Photons are Massless particle, massless ...

s for interplanetary and interstellar spacecraft

A starship, starcraft, or interstellar spacecraft is a theoretical spacecraft designed for traveling between planetary systems.

The term is mostly found in science fiction. Reference to a "star-ship" appears as early as 1882 in '' Oahspe: A Ne ...

propulsion prefiguring the concept of laser propulsion and the solar sail.

In 1960, he assisted the United Arab Republic

The United Arab Republic (UAR; ar, الجمهورية العربية المتحدة, al-Jumhūrīyah al-'Arabīyah al-Muttaḥidah) was a sovereign state in the Middle East from 1958 until 1971. It was initially a political union between Eg ...

in developing the Al-Zafir missile.

He died in Berlin, in 1964. Sänger's grave is located in the cemetery "Alter Friedhof" in Stuttgart-Vaihingen

Stuttgart (; Swabian: ; ) is the capital and largest city of the German state of Baden-Württemberg. It is located on the Neckar river in a fertile valley known as the ''Stuttgarter Kessel'' (Stuttgart Cauldron) and lies an hour from the S ...

.

His work on the ''Silbervogel'' would prove important to the X-15, X-20 Dyna-Soar, and ultimately Space Shuttle program

The Space Shuttle program was the fourth human spaceflight program carried out by the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), which accomplished routine transportation for Earth-to-orbit crew and cargo from 1981 to 2011. I ...

s.

Honours

Honorary member of numerous societies for Space Research in Germany, Great Britain, Austria, the United States of America, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, Argentina, Italy. * Elected Honorary Fellow of theBritish Interplanetary Society

The British Interplanetary Society (BIS), founded in Liverpool in 1933 by Philip E. Cleator, is the oldest existing space advocacy organisation in the world. Its aim is exclusively to support and promote astronautics and space exploration.

Str ...

(B.I.S.) in 1949

* Hermann Oberth Medal for services to aerospace research

* Austrian Cross of Honour for Science and Art, 1st class

The Austrian Decoration for Science and Art (german: Österreichisches Ehrenzeichen für Wissenschaft und Kunst) is a state decoration of the Republic of Austria and forms part of the Austrian national honours system.

History

The "Austrian ...

* Commander of the Ordre du Merite

A suite, in Western classical music and jazz, is an ordered set of instrumental or orchestral/concert band pieces. It originated in the late 14th century as a pairing of dance tunes and grew in scope to comprise up to five dances, sometimes with ...

pour la Recherche et l'Invention, Paris

* Gagarin Gold Medal Assoziazione Internazionale Uomo nello Spazio, Rome

* Gold Medal at the Milan Fair

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city h ...

* Sängergasse named after him in Vienna Simmering (11th District) (1971)

See also

* Keldysh bomber * Laser propulsion * Silbervogel *Spacecraft propulsion

Spacecraft propulsion is any method used to accelerate spacecraft and artificial satellites. In-space propulsion exclusively deals with propulsion systems used in the vacuum of space and should not be confused with space launch or atmospheric ...

Notes

References and further reading

Books and technical reports

* * * * * ''Saenger, Hartmut E and Szames, Alexandre D, From the Silverbird to Interstellar Voyages, IAC-03-IAA.2.4.a.07.'' * * * *Other

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Sanger, Eugen Austrian aerospace engineers 1905 births 1964 deaths People from Chomutov District Austrian people of German Bohemian descent German spaceflight pioneers Research and development in Nazi Germany Rocket scientists Recipients of the Austrian Cross of Honour for Science and Art, 1st class SS personnel Austrian expatriates in Egypt