Ethel Moorhead on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ethel Agnes Mary Moorhead (28 August 18694 March 1955) was a British

After training as an artist, when she was 29, in

After training as an artist, when she was 29, in

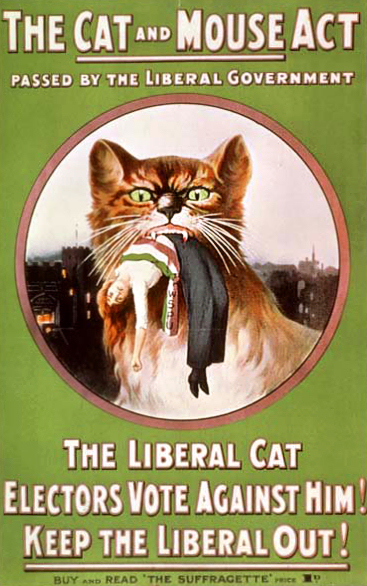

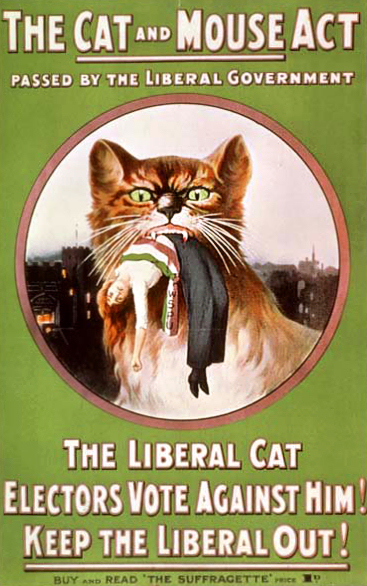

Moorhead herself was imprisoned several times and released under the "Cat and Mouse Act" of 1913.

She had become known as the first Scottish suffragette to be forcibly fed, while imprisoned in Calton Jail Edinburgh under the care of Dr

Moorhead herself was imprisoned several times and released under the "Cat and Mouse Act" of 1913.

She had become known as the first Scottish suffragette to be forcibly fed, while imprisoned in Calton Jail Edinburgh under the care of Dr

The Scottish Records Office has Moorhead's prison-related correspondence, which was exhibited in 2018, as part of an

The Scottish Records Office has Moorhead's prison-related correspondence, which was exhibited in 2018, as part of an

Full record for 'ETHEL MOORHEAD' (7362) – Moving Image Archive catalogue

Information on a film (2011) reconstructing the Ethel Moorhead story. Film available for private viewings in the National Library of Scotland, George IV Bridge, Edinburgh. Retrieved 6 July 2021. *Biography of Ethel Moorhead (2020) Mary Henderson

Introduction to Ethel Moorhead – A Biography of Ethel Moorhead

ref name=":2" /> Retrieved 6 July 2021. *National Records Scotland Criminal Case Files re (Stirling) 7 September 191

and re (Aberdeen) 3 December 191

suffragette

A suffragette was a member of an activist women's organisation in the early 20th century who, under the banner "Votes for Women", fought for the right to vote in public elections in the United Kingdom. The term refers in particular to members ...

and painter

Painting is a Visual arts, visual art, which is characterized by the practice of applying paint, pigment, color or other medium to a solid surface (called "matrix" or "Support (art), support"). The medium is commonly applied to the base with ...

and was the first suffragette

A suffragette was a member of an activist women's organisation in the early 20th century who, under the banner "Votes for Women", fought for the right to vote in public elections in the United Kingdom. The term refers in particular to members ...

in Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

to be forcibly-fed.

She was also a patron of ''This Quarter'', a journal published by Ernest Walsh. The journal featured writers such as Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Miller Hemingway ( ; July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an American novelist, short-story writer and journalist. Known for an economical, understated style that influenced later 20th-century writers, he has been romanticized fo ...

, James Joyce

James Augustine Aloysius Joyce (born James Augusta Joyce; 2 February 1882 – 13 January 1941) was an Irish novelist, poet, and literary critic. He contributed to the modernist avant-garde movement and is regarded as one of the most influentia ...

and Ezra Pound

Ezra Weston Loomis Pound (30 October 1885 – 1 November 1972) was an List of poets from the United States, American poet and critic, a major figure in the early modernist poetry movement, and a Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Ita ...

.

Early life

Moorhead was born on 28 August 1869 in Fisher Street,Maidstone

Maidstone is the largest Town status in the United Kingdom, town in Kent, England, of which it is the county town. Maidstone is historically important and lies east-south-east of London. The River Medway runs through the centre of the town, l ...

, Kent

Kent is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Essex across the Thames Estuary to the north, the Strait of Dover to the south-east, East Sussex to the south-west, Surrey to the west, and Gr ...

. She was one of six children of Brigadier Surgeon George Alexander Moorhead, an army surgeon of Irish Catholic birth, and his wife, Margaret Humphreys (18331902), an Irish woman of French-Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , ; ) are a Religious denomination, religious group of French people, French Protestants who held to the Reformed (Calvinist) tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, ...

ancestry, whom he had married in India, at Madras

Chennai, also known as Madras ( its official name until 1996), is the capital and largest city of Tamil Nadu, the southernmost state of India. It is located on the Coromandel Coast of the Bay of Bengal. According to the 2011 Indian ce ...

Roman Catholic Cathedral on 9 September 1864.

Her maternal grandfather was Captain John Goulin Humphreys, a Napoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

veteran and in an earlier generation one of her mother's family (Pierre Goulin) fought in the 1690 Battle of the Boyne

The Battle of the Boyne ( ) took place in 1690 between the forces of the deposed King James II, and those of King William III who, with his wife Queen Mary II (his cousin and James's daughter), had acceded to the Crowns of England and Sc ...

.

Her older sister Alice Moorhead (1868–1910) was a pioneer of female medicine, trained as a surgeon and physician, and four of her brothers were doctors, as were several male members of her father's family.

Her father was posted with the Berkshire Regiment to Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. It is bordered by Pakistan to the Durand Line, east and south, Iran to the Afghanistan–Iran borde ...

as army surgeon in 1870, and she would have seen little of him in her early years, from his time in India in the post-mutiny years to being promoted to Surgeon-Major when Moorhead was just four years old. The family lived in Shoeburyness

Shoeburyness ( ), or simply Shoebury, is a coastal town in the City of Southend-on-Sea, in the ceremonial county of Essex, England; it lies east of the city centre. It was formerly a separate town until it was absorbed into Southend in 1933.

I ...

in Kent and then he was posted to Port Louis, Mauritius

Port Louis (, ; or , ) is the capital and most populous city of Mauritius, mainly located in the Port Louis District, with a small western part in the Black River District. Port Louis is the country's financial and political centre. It is ad ...

and retired as Brigadier-Surgeon in 1880, and they moved to Galway

Galway ( ; , ) is a City status in Ireland, city in (and the county town of) County Galway. It lies on the River Corrib between Lough Corrib and Galway Bay. It is the most populous settlement in the province of Connacht, the List of settleme ...

, where the children were schooled. When her brothers George Oliver and Arthur and sister Alice were studying medicine in Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. The city is located in southeast Scotland and is bounded to the north by the Firth of Forth and to the south by the Pentland Hills. Edinburgh ...

, from 1888 to 1894, the family were at 20 Windsor Street, Edinburgh. Then the family were in St. Helier, Jersey before going to Glasgow

Glasgow is the Cities of Scotland, most populous city in Scotland, located on the banks of the River Clyde in Strathclyde, west central Scotland. It is the List of cities in the United Kingdom, third-most-populous city in the United Kingdom ...

, where another brother, Rupert, studied medicine, before her father settled at 20 Magdalen Yard Road, Dundee

Dundee (; ; or , ) is the List of towns and cities in Scotland by population, fourth-largest city in Scotland. The mid-year population estimate for the locality was . It lies within the eastern central Lowlands on the north bank of the Firt ...

from 1900 and so in 1902 lived closer to Alice

Alice may refer to:

* Alice (name), most often a feminine given name, but also used as a surname

Literature

* Alice (''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland''), a character in books by Lewis Carroll

* ''Alice'' series, children's and teen books by ...

and her newly created Dundee Women's Hospital. The family then moved temporarily to ''Pitalpin House'', Lochee

Lochee () is an area in the west of Dundee, Scotland. Until the 19th century, it was a separate town, but was eventually surrounded by the expanding Dundee. It is notable for being home to Camperdown Works, which was the largest jute production ...

and in 1907 moved into the newly built The Wiesha''Career

After training as an artist, when she was 29, in

After training as an artist, when she was 29, in Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

under Mucha

Mucha (; ; Czech and Slovak feminine: Muchová) is a Slavic surname, derived from ''mucha'', meaning " fly".''Dictionary of American Family Names''"Mucha Family History" Oxford University Press, 2013. Retrieved on 4 January 2016. Mucha is the stan ...

and in Whistler's studio, the Atelier Carmen, between October 1898 and April 1901, with fellow Dundee painter, Janet Oliphant, Moorhead returned to Dundee and set up a portrait studio with Oliphant where she worked for fifteen years, in The Arcade, 4 King Street. Both joined the Dundee Graphic Art Association, Oliphant as an associate, Moorhead as ordinary member up to 1909. Moorhead's first exhibition was a landscape and six other pictures, in the Centennial Exhibition in 1901, with the local press, including the ''Dundee Advertiser'' praising her work as among the 'gems of the collection from an artistic point of view.' Her mother died in 1902, and she took over the care for her father from 1908 (after Alice married, with Ethel as a witness) and she often used her father as a model, one titled ''Brigade Surgeon G. A. Moorhead'' was described as 'in the way of portraiture.. nothing finer.. a triumph of art' in the ''Courier

A courier is a person or organization that delivers a message, package or letter from one place or person to another place or person. Typically, a courier provides their courier service on a commercial contract basis; however, some couriers are ...

,'' and Moorhead knowing the sitter made a difference, said the ''Evening Telegraph

''Evening Telegraph'' is a common newspaper name, and may refer to:

* ''Evening Telegraph'' (Dundee), Scotland

* ''Evening Telegraph'' (Dublin), Ireland, published 1871–1924.

* ''Coventry Evening Telegraph'', England, now the ''Coventry Telegr ...

.'' The ''Celtic Annual'' described her as a 'most refined and distinguished artist' and at her last exhibition with the Dundee Graphic Artists, the pricing for paintings increased.

Her sister Alice died in childbirth in 1910, and her father then died in 1911; both were buried with her mother in Dundee's Western Cemetery.

Moorhead moved to Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. The city is located in southeast Scotland and is bounded to the north by the Firth of Forth and to the south by the Pentland Hills. Edinburgh ...

, staying at 12 Queen Street. She exhibited works at even higher prices in Glasgow in 1912, with four paintings at the Glasgow Institute of Fine Arts. One of her portraits,''The Conspirator,'' was chosen to be exhibited in the Royal Scottish Academy

The Royal Scottish Academy (RSA) is the country's national academy of art. It promotes contemporary art, contemporary Scottish art.

The Academy was founded in 1826 by eleven artists meeting in Edinburgh. Originally named the Scottish Academy ...

along with two others, and three were shown at the Aberdeen Artists' Society and she had works in the Walker Art Gallery

The Walker Art Gallery is an art gallery in Liverpool, which houses one of the largest art collections in England outside London. It is part of the National Museums Liverpool group.

History

The Walker Art Gallery's collection dates from 1819 ...

, Liverpool

Liverpool is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. It is situated on the eastern side of the River Mersey, Mersey Estuary, near the Irish Sea, north-west of London. With a population ...

. A portrait of a dog by Moorhead (dated 1915 or 1916) is in Missouri, USA.

Moorhead joined her friend Oliphant on the Lochee Day Nursery management committee and volunteered at the Grey Lodge Settlement at Hilltown which provided a variety of social support services, especially for young mothers.

Suffragette campaigning

Moorhead (when aged 41) made her maiden speech at aDundee

Dundee (; ; or , ) is the List of towns and cities in Scotland by population, fourth-largest city in Scotland. The mid-year population estimate for the locality was . It lies within the eastern central Lowlands on the north bank of the Firt ...

Women’s Social and Political Union

The Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) was a women-only political movement and leading militant organisation campaigning for women's suffrage in the United Kingdom founded in 1903. Known from 1906 as the suffragettes, its membership and p ...

(WSPU) meeting in March 1910; in December she accused Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

of 'brutal treatment' of suffragette hunger strikers and threw an egg at him during a meeting in Dundee, and she hit the organisers trying to remove her with an umbrella. In 1911, the Dundee branch of the Women's Freedom League

The Women's Freedom League was an organisation in the United Kingdom from 1907 to 1961 which campaigned for women's suffrage, pacifism and sexual equality. It was founded by former members of the Women's Social and Political Union after the Pa ...

congratulated her on becoming Dundee's first tax-resister. Sheriff officers came to take goods in lieu of taxes to be auctioned (a silver candelabra), with Moorhead's supporters waving placards saying "No Vote, No Tax" and making fun of the bidding process.

Moorhead used a string of aliases ('Mary Humphreys', 'Edith Johnston', 'Margaret Morrison'), and carried out various acts of militancy both north and south of the border. They included smashing two windows in London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

, with Enid Rennie Enid may refer to:

Places

*Enid, Mississippi, an unincorporated community

*Enid, Oklahoma, a city

* 13436 Enid, an asteroid

*Enid Lake, Mississippi

Given name

*Enid (given name), a Welsh female given name and a list of people and fictional charact ...

from Broughty Ferry

Broughty Ferry (; ; ) is a suburb of Dundee, in Scotland. It is situated four miles east of the City Centre, Dundee, city centre on the north bank of the Firth of Tay. The area was a separate burgh from 1864 until 1913, when it was incorporated ...

(eventually sentenced to two months) and Florence McFarlane, a nurse who lived in the Nethergate, Dundee (sentenced to four months), and Moorhead's target was a Thomas Cook

Thomas Cook (22 November 1808 – 18 July 1892) was the founder of the travel agency Thomas Cook & Son. He was born into a poor family in Derbyshire and left school at the age of ten to start work as a gardener's boy. He served an appren ...

Fleet Street

Fleet Street is a street in Central London, England. It runs west to east from Temple Bar, London, Temple Bar at the boundary of the City of London, Cities of London and City of Westminster, Westminster to Ludgate Circus at the site of the Lo ...

shop (but in the subsequent trial, despite arresting her, their witnesses got confused). On arrest she is reported as saying 'I am a householder without a vote. I came from Scotland at great personal inconvenience to myself to help my comrades.' The women found guilty were taken straight to Holloway Prison

HM Prison Holloway was a British prison security categories, closed category prison for adult women and young offenders in Holloway, London, England, operated by His Majesty's Prison Service. It was the largest women's prison in western Europe, ...

where Moorhead noted in her memoirs ''Incendiaries,'' that the bed was a 'board for sleeping on had a blanket decorated with arrowheads, the badge of the condemned.' Due to lack of evidence from the shopkeepers, she was one of those who were released after the trial.

Later that year, Moorhead was caught attacking a showcase containing a historical sword at the Wallace Monument

The National Wallace Monument (generally known as the Wallace Monument) is a tower on the shoulder of the Abbey Craig, a hilltop overlooking Stirling in Scotland. It commemorates Sir William Wallace, a 13th- and 14th-century Scottish hero.

...

near Stirling

Stirling (; ; ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city in Central Belt, central Scotland, northeast of Glasgow and north-west of Edinburgh. The market town#Scotland, market town, surrounded by rich farmland, grew up connecting the roya ...

, with a stone wrapped in a note saying 'YOUR LIBERTIES WERE WON BY THE SWORD. RELEASE THE WOMEN WHO ARE FIGHTING FOR THEIR LIBERTIES. A PROTEST FROM DUBLIN' and was arrested under the name 'Edith Johnston'. This action was defended by Muriel Scott

Muriel Eleanor Scott (1888–1963), was a Scottish suffragette, hunger striker, and protest organiser. Her sister Arabella Scott was force-fed many times, and Muriel Scott led protests about this cruel treatment.

Family and education

Muriel ...

and Elizabeth Finlayson Gauld at an open air gathering a week later.

At her trial 'Johnston" said 'she was not guilty but approved of the woman who had done it.' and “Your liberties were won with the sword. That sword was a mere symbol just as the stones and hammers with which women are fighting for their freedom and which they shall win." She was fined £2 or seven days in prison, choosing the latter, she was in Stirling

Stirling (; ; ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city in Central Belt, central Scotland, northeast of Glasgow and north-west of Edinburgh. The market town#Scotland, market town, surrounded by rich farmland, grew up connecting the roya ...

then Perth

Perth () is the list of Australian capital cities, capital city of Western Australia. It is the list of cities in Australia by population, fourth-most-populous city in Australia, with a population of over 2.3 million within Greater Perth . The ...

prison, where she was given the 'privilege of wearing her own clothes, and having books' but continued to refuse to obey prison rules, and kept complaining and it was said by the authorities that the 'complaint is made for the sole purpose of carrying out the avowed policy of the Suffragists to cause trouble.' Moorhead responded that officials 'should not be encouraged to try to coerce prisoners into submission to Rules which only apply to Criminals.' The women's suffrage supporters had long considered they should be treated as political prisoners

A political prisoner is someone imprisoned for their political activity. The political offense is not always the official reason for the prisoner's detention.

There is no internationally recognized legal definition of the concept, although ...

.

In October 1912 after being ejected from a meeting in Synod Hall, Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. The city is located in southeast Scotland and is bounded to the north by the Firth of Forth and to the south by the Pentland Hills. Edinburgh ...

, where Sir Rufus Isaacs was speaking, Moorhead returned to attack the male lecturer from Broughton School at his work, with a dog whip to attack him in return for having ejected her. Letters to the press objected at the physical violence to eject women who were simply wanting to question speakers, and others from the crowds who cheered on and supported the violence. She was arrested for this attack under her own name, and was fined £1, which was paid, so Moorhead never went to prison for her action.

The next month, 29 November 1912, Moorhead (in the name of 'Mary Humphrys') and Fanny Parker, whom she had befriended in prison before, and Olive Wharry (under the name of 'Joyce Locke') and Emily Davison

Emily Wilding Davison (11 October 1872 – 8 June 1913) was an English suffragette who fought for Women's suffrage in the United Kingdom, votes for women in Britain in the early twentieth century. A member of the Women's Social and Polit ...

(under the name of 'Mary Brown') along with minister's daughter Mary Pollock Grant (under the name of 'Marian Pollock') planned that some women may be able to get into the Liberal Association meeting in Aberdeen

Aberdeen ( ; ; ) is a port city in North East Scotland, and is the List of towns and cities in Scotland by population, third most populous Cities of Scotland, Scottish city. Historically, Aberdeen was within the historic county of Aberdeensh ...

where Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and the head of HM Treasury, His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, t ...

Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. A Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, he was known for leadi ...

was to be speaking. Moorhead and Davison were to attack outside but went for the wrong person, and Moorhead broke a car window, but all of the group were arrested. Again Moorhead conducted her own defence including requesting that Lloyd George be called as a witness. Of course this did not happen, and again she was fined (40 shillings) or to be imprisoned (ten days) for damage to property, which she chose. This was the first time she went on a hunger strike

A hunger strike is a method of non-violent resistance where participants fasting, fast as an act of political protest, usually with the objective of achieving a specific goal, such as a policy change. Hunger strikers that do not take fluids are ...

, but with the others was released early as the fines had been paid, anonymously. Moorhead wrote to the press (''The Scotsman

''The Scotsman'' is a Scottish compact (newspaper), compact newspaper and daily news website headquartered in Edinburgh. First established as a radical political paper in 1817, it began daily publication in 1855 and remained a broadsheet until ...

)'' complaining about prison conditions on remand and in the Aberdeen

Aberdeen ( ; ; ) is a port city in North East Scotland, and is the List of towns and cities in Scotland by population, third most populous Cities of Scotland, Scottish city. Historically, Aberdeen was within the historic county of Aberdeensh ...

gaol which led to questions to the Secretary of State in Parliament, as the complaint was about pre-trial behaviour by the police.

She had a reputation for wrecking police cells, and carrying out several arson

Arson is the act of willfully and deliberately setting fire to or charring property. Although the act of arson typically involves buildings, the term can also refer to the intentional burning of other things, such as motor vehicles, watercr ...

attacks. Moorhead had thrown cayenne pepper

The cayenne pepper is a type of ''Capsicum annuum''. It is usually a hot chili pepper used to flavor dishes. Cayenne peppers are a group of tapering, 10 to 25 cm long, generally skinny, mostly red-colored peppers, often with a curved ti ...

at a police constable at an event where Prime Minister Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928) was a British statesman and Liberal Party (UK), Liberal politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1908 to 1916. He was the last ...

was due to speak, and was taken to Methil and then Dundee prison, where she caused an amount of damage by breaking windows. Early in 1913, she tried to write to Arabella Scott

Arabella Scott (7 May 1886 – 27 August 1980) was a Scottish teacher, suffragette hunger striker and women's rights campaigner. As a member of the Women's Freedom League (WFL) she took a petition to Downing Street in July 1909. She subsequen ...

who lived at 88 Marchmont Road, Edinburgh about an incident of an amorous approach by an inebriated prison doctor, which she feared would be used as propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded l ...

. The Dundee Gaol governor did not release it. Again her trial resulted in some disorder from her refusal to recognise the proceedings and a sentence of £20 or thirty days (which she chose). She went on hunger strike and refused to assist a medical examination, after four days, and so she was discharged. In another hearing in Edinburgh, Moorhead said to the judge 'I want to say this is another Court of Injustice' and (addressing Lord Chief Justice) 'you are an unjust old man'

She engaged in repeated complaint correspondence with prison and law authorities about her treatment on remand for protesting for women's suffrage, about the prison conditions, lack of respect from the staff and about the cruelty of the force-feeding.

On 23 July 1913, with Dorothea Chalmers Smith, Moorhead (in the alias 'Margaret Morrison') attempted to set fire to a house at 6 Park Gardens in Glasgow

Glasgow is the Cities of Scotland, most populous city in Scotland, located on the banks of the River Clyde in Strathclyde, west central Scotland. It is the List of cities in the United Kingdom, third-most-populous city in the United Kingdom ...

, but they were caught at the scene and the firefighters found flammable materials and a postcard bearing the words: 'A protest against Mrs Pankhurst's re-arrest'. In this trial, Moorhead tried to object that the judge had misdirected the jury and she was removed for contempt of court

Contempt of court, often referred to simply as "contempt", is the crime of being disobedient to or disrespectful toward a court of law and its officers in the form of behavior that opposes or defies the authority, justice, and dignity of the co ...

, but brought back to hear the sentence of eight months imprisonment. At this point she turned to the sympathetic suffragette attendees and shouted "No Surrender" which resulted in chaos in the court as others joined in shouting, throwing apples, singing aloud '' The Marseillaise'' and so three more arrests were made. ''The Glasgow Herald

''The Herald'' is a Scottish broadsheet newspaper founded in 1783. ''The Herald'' is the longest running national newspaper in the world and is the eighth oldest daily paper in the world. The title was simplified from ''The Glasgow Herald'' in ...

'' ran a cartoon titled 'Hallowe'en at the High Court'. Moorhead held no formal position in the WSPU, but had achieved great personal notoriety. Her brother Rupert became doctor to the Blathwayt family at Eagle House, the suffragettes rest at Batheaston, near Bath, but was no sympathiser to the suffragette 'hooligans' as he called them in 1908, but he was said to be generous in foregoing fees to poorer patients.

Moorhead herself was imprisoned several times and released under the "Cat and Mouse Act" of 1913.

She had become known as the first Scottish suffragette to be forcibly fed, while imprisoned in Calton Jail Edinburgh under the care of Dr

Moorhead herself was imprisoned several times and released under the "Cat and Mouse Act" of 1913.

She had become known as the first Scottish suffragette to be forcibly fed, while imprisoned in Calton Jail Edinburgh under the care of Dr Hugh Ferguson Watson

Dr Hugh Ferguson Watson FRSE FRFPS MRCP DPH (1874–1946) was a 19th/20th-century Scottish physician who came to notoriety during the suffragette struggles of the early 20th century, particularly with reference to the Cat and Mouse Act in his ca ...

, although the initial feeding was performed by Dr James Dunlop, medical adviser to HM Prison Commissioners for Scotland, who was based at Morningside Asylum.

Having been force fed more than 25 times, over a week or so, Moorhead become seriously ill with double pneumonia

Pneumonia is an Inflammation, inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as Pulmonary alveolus, alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of Cough#Classification, productive or dry cough, ches ...

, and had even been given absolution

Absolution is a theological term for the forgiveness imparted by ordained Priest#Christianity, Christian priests and experienced by Penance#Christianity, Christian penitents. It is a universal feature of the historic churches of Christendom, alth ...

by the prison chaplain. Her solicitor intervened and she was handed a bunch of sweet peas from fellow suffragette Arabella Scott

Arabella Scott (7 May 1886 – 27 August 1980) was a Scottish teacher, suffragette hunger striker and women's rights campaigner. As a member of the Women's Freedom League (WFL) she took a petition to Downing Street in July 1909. She subsequen ...

as she was at last released into the care of Dr Grace Cadell, a fellow activist in the suffrage movement. Arriving at Cadell's home, 145 Leith Walk

Leith Walk is one of the longest streets in Edinburgh, Scotland, and is the main road connecting the east end of the city centre to Leith.

Forming most of the A900 road, it slopes downwards from Picardy Place at the south-western end of the str ...

, 150 police had been awaiting a demonstration, but none arose, although a call had gone out earlier in the ''Dundee Courier'' letters page from Emily Pankhurst and Lila Clunas and in ''The Scotsman'' an advert inviting 'thousands' to march from Charlotte Square

file:Charlotte Square - geograph.org.uk - 105918.jpg, 300px, Robert Adam's palace-fronted north side

Charlotte Square is a garden square in Edinburgh, Scotland, part of the New Town, Edinburgh, New Town, designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site ...

to Calton Prison

Governor's House is a building situated on the southernmost spur of Calton Hill, beside the south-east corner of Old Calton Burial Ground, in Edinburgh, Scotland. It looks out over Edinburgh Waverley railway station, Waverley Station, the The C ...

, along Princes Street

Princes Street () is one of the major thoroughfares in central Edinburgh, Scotland and the main shopping street in the capital. It is the southernmost street of Edinburgh's New Town, Edinburgh, New Town, stretching around 1.2 km (three quar ...

in protest at Moorhead's treatment (but she had already been released by the set time). Despite the many well wishers, she was so weak that she only allowed visits from Dr Mabel Jones

Mabel Jones (c. 1865–1923) was a British physician and a sympathizer to the Women's Social and Political Union, Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU).

Medical career

Trained in London and from 1898, she worked in a practice with her fel ...

or her Broughty Ferry friend, Enid Rennie Enid may refer to:

Places

*Enid, Mississippi, an unincorporated community

*Enid, Oklahoma, a city

* 13436 Enid, an asteroid

*Enid Lake, Mississippi

Given name

*Enid (given name), a Welsh female given name and a list of people and fictional charact ...

, who had written to Dr. Devon who had been the lead prison doctor who latterly conducted the force feeding, that it was 'a permanent blot on the record of so many fights for liberty in which Scotland has hitherto born a noble part'. Elizabeth Gauld, Janie Allan

Jane "Janie" Allan (28 March 1868 – 29 April 1968)Ewan ''et al.'' (2006), p. 11 was a Scottish activist and fundraiser for the suffragette movement of the early 20th century.

Early life and family

Janie Allan was born to Jane Smith and Alexa ...

and others wrote to object and his responses showed he would prefer to consider her 'mad'. The arson at Whitekirk

Whitekirk is a small settlement in East Lothian, Scotland. Together with the nearby settlement of Tyninghame, it gives its name to the parish of Whitekirk and Tyninghame.

Whitekirk

Whitekirk is from North Berwick, from Dunbar and east of Ed ...

Church was said by Allan to be a revenge for Moorhead's treatment. Her prison force feeding experiences – duly related to the presscaused much protest at the cruelty involved. Her treatment and resultant activism was raised in Parliament, the Secretary of State asked on two occasions about the treatment and 'her life being endangered'.

Moorhead 'escaped' re-arrest by leaving Cadell's home in disguise, with Leith

Leith (; ) is a port area in the north of Edinburgh, Scotland, founded at the mouth of the Water of Leith and is home to the Port of Leith.

The earliest surviving historical references are in the royal charter authorising the construction of ...

Police issuing a warrant.

These prison experiences did not stop her militant activity, however, and along with her friend Fanny Parker she was arrested in July 1914, for trying to blow up the Burns Cottage in Alloway

Alloway (, ) is a suburb of Ayr, and former village, in South Ayrshire, Scotland, located on the River Doon. It is best known as the birthplace of Robert Burns and the setting for his poem Tam o' Shanter (Burns poem), "Tam o' Shanter". Tobias Ba ...

. Moorhead escaped by bicycle as Fanny was said to have allowed herself to be arrested to save her friend. Another arson attributed to her for which she was never caught was at Carmichael (Cairngyffe) Church, Lanarkshire

Lanarkshire, also called the County of Lanark (; ), is a Counties of Scotland, historic county, Lieutenancy areas of Scotland, lieutenancy area and registration county in the Central Lowlands and Southern Uplands of Scotland. The county is no l ...

. Her own memoirs were called ''Incendiaries'' and did not find favour with her brothers. But brother Arthur, who died in Batheaston, staying with Rupert, in 1916, left her £2152 in trust in his will.

Moorhead had been given a Hunger Strike Medal

The Hunger Strike Medal was a silver medal awarded between August 1909 and 1914 to suffragette prisoners by the leadership of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). During their imprisonment, many went on hunger strike while serving the ...

'for Valour' by WSPU, with dated silver bars for 29 August 2012, 29 November 1912, 29 January 2013, 15 October 2015. And the silk lined box has imprinted in gold lettering:'Presented to Ethel Agnes Moorhead in recognition of a gallant action whereby through endurance to the last extremity of hunger and hardship a great principle of political justice was vindicated.'

Other campaigning and later life

During theFirst World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, Moorhead took on additional organisational responsibilities. Together with Fanny Parker, she helped run the Women's Freedom League

The Women's Freedom League was an organisation in the United Kingdom from 1907 to 1961 which campaigned for women's suffrage, pacifism and sexual equality. It was founded by former members of the Women's Social and Political Union after the Pa ...

(WFL) National Service Organisation, encouraging women to find appropriate war work from an office at 144 High Street, Holburn, London. Their contribution was praised by founder Charlotte Despard

Charlotte Despard (née French; 15 June 1844 – 10 November 1939) was an Anglo-Irish people, Anglo-Irish suffragist, socialist, pacifist, Sinn Féin activist, and novelist. She was a founding member of the Women's Freedom League, the Women's Pe ...

at a rally in Kingsway Hall

The Kingsway Hall in Holborn, London, was the base of the West London Mission (WLM) of the Methodist Church, and eventually became one of the most important recording venues for classical music and film music.

It was built in 1912 and demolish ...

, September 1915 as “The competent women who direct the work inspire an immense confidence by their keen intelligence, lively sympathy and brisk business capacity”.

In the 1920s, she travelled in Europe and lived in 1918–19 at 5 Burgh Quay, Dublin. Moorhead rented a house Windgates''Wicklow

Wicklow ( ; , meaning 'church of the toothless one'; ) is the county town of County Wicklow in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is located on the east of Ireland, south of Dublin. According to the 2022 census of Ireland, 2022 census, it had ...

. She edited a quarterly arts journal, ''This Quarter'' which published work by, among others, James Joyce

James Augustine Aloysius Joyce (born James Augusta Joyce; 2 February 1882 – 13 January 1941) was an Irish novelist, poet, and literary critic. He contributed to the modernist avant-garde movement and is regarded as one of the most influentia ...

, Ezra Pound

Ezra Weston Loomis Pound (30 October 1885 – 1 November 1972) was an List of poets from the United States, American poet and critic, a major figure in the early modernist poetry movement, and a Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Ita ...

and Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Miller Hemingway ( ; July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an American novelist, short-story writer and journalist. Known for an economical, understated style that influenced later 20th-century writers, he has been romanticized fo ...

, Constantin Brancusi, Francis Picabia

Francis Picabia (: born Francis-Marie Martinez de Picabia; 22January 1879 – 30November 1953) was a French avant-garde painter, writer, filmmaker, magazine publisher, poet, and typography, typographist closely associated with Dada.

When consid ...

and Man Ray

Man Ray (born Emmanuel Radnitzky; August 27, 1890 – November 18, 1976) was an American naturalized French visual artist who spent most of his career in Paris. He was a significant contributor to the Dada and Surrealism, Surrealist movements, ...

. By 1920, she was back near Dundee, at Bonnyton House, Arbirlot

Arbirlot (Gaelic: ''Obar Eilid'') is a village in a rural parish of the same name in Angus, Scotland. The current name is usually presumed to be a contraction of Aberelliot''Statistical Account of Scotland'', edited by Sir John Sinclair of Ulbster ...

which her sister Alice's medical partner Dr. Emily Thomson owned. And from 1922 to 1926, at 36 George Street, Edinburgh although she was often in France. Little more is known until she died in Dublin

Dublin is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Situated on Dublin Bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, and is bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, pa ...

in 1955.

Legacy

A commemorative plaque has been placed close to the site of her studio in Dundee (site of the King Street Arcade at the corner of King Street and St Roque’s Lane, near the underpass). A film based on her life is available for private view at theNational Library of Scotland

The National Library of Scotland (NLS; ; ) is one of Scotland's National Collections. It is one of the largest libraries in the United Kingdom. As well as a public programme of exhibitions, events, workshops, and tours, the National Library of ...

.

The Scottish Records Office has Moorhead's prison-related correspondence, which was exhibited in 2018, as part of an

The Scottish Records Office has Moorhead's prison-related correspondence, which was exhibited in 2018, as part of an Edinburgh Festival Fringe

The Edinburgh Festival Fringe (also referred to as the Edinburgh Fringe, the Fringe or the Edinburgh Fringe Festival) is the world's largest performance arts festival, which in 2024 spanned 25 days, sold more than 2.6 million tickets and featur ...

exhibition marking the centenary

A centennial, or centenary in British English, is a 100th anniversary or otherwise relates to a century.

Notable events

Notable centennial events at a national or world-level include:

* Centennial Exhibition, 1876, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. ...

of the Representation of the People Act 1918

The Representation of the People Act 1918 ( 7 & 8 Geo. 5. c. 64) was an act of Parliament passed to reform the electoral system in Great Britain and Ireland. It is sometimes known as the Fourth Reform Act. The act extended the franchise in pa ...

, at the National Records of Scotland (NRS) called ''‘Malicious Mischief? Women’s Suffrage in Scotland’,'' describing suffragettes and suffragists, their different approach and experiences and the timeline of the case for women's suffrage.

In 2014 a public street in Perth, Ethel Moorhead Place, was named after her. An adjacent street, Frances Gordon Road, was named after fellow suffragette Frances Gordon

Frances Graves aka Frances Gordon (born around 1874) was a British suffragette who became prominent in the militant wing of the Scottish women's suffrage movement prior to the First World War and was imprisoned and force-fed for her actions.

...

.

In 2024, a housing development in Hilltown, Dundee was completed which included a pedestrian street named Moorhead Street, commemorating Ethel Moorhead.

See also

*List of suffragists and suffragettes

This list of suffragists and suffragettes includes noted individuals active in the worldwide women's suffrage movement who have campaigned or strongly advocated for women's suffrage, the organisations which they formed or joined, and the publi ...

* Hunger Strike Medal

The Hunger Strike Medal was a silver medal awarded between August 1909 and 1914 to suffragette prisoners by the leadership of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). During their imprisonment, many went on hunger strike while serving the ...

* Annie Walker Craig, with whom Moorhead conspired to burn buildings in Upper Strathearn, Comrie.

External links

* *Full record for 'ETHEL MOORHEAD' (7362) – Moving Image Archive catalogue

Information on a film (2011) reconstructing the Ethel Moorhead story. Film available for private viewings in the National Library of Scotland, George IV Bridge, Edinburgh. Retrieved 6 July 2021. *Biography of Ethel Moorhead (2020) Mary Henderson

Introduction to Ethel Moorhead – A Biography of Ethel Moorhead

ref name=":2" /> Retrieved 6 July 2021. *National Records Scotland Criminal Case Files re (Stirling) 7 September 191

and re (Aberdeen) 3 December 191

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Moorhead, Ethel 1869 births 1955 deaths People from Maidstone 20th-century Scottish women 20th-century British painters Scottish suffragists Scottish women in politics People associated with Dundee Women's Social and Political Union Hunger Strike Medal recipients Scottish women activists