environmental movement in the United States on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The organized environmental movement is represented by a wide range of

The organized environmental movement is represented by a wide range of

During the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, several events occurred which raised the public awareness of harm to the environment caused by man. In 1954, the 23 man crew of the Japanese fishing vessel '' Lucky Dragon'' was exposed to radioactive fallout from a hydrogen bomb test at Bikini Atoll. By 1969, the public reaction to an ecologically catastrophic oil spill from an offshore well in California's Santa Barbara Channel,

During the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, several events occurred which raised the public awareness of harm to the environment caused by man. In 1954, the 23 man crew of the Japanese fishing vessel '' Lucky Dragon'' was exposed to radioactive fallout from a hydrogen bomb test at Bikini Atoll. By 1969, the public reaction to an ecologically catastrophic oil spill from an offshore well in California's Santa Barbara Channel,

The Spirit of June 12

''The Nation'', July 2, 2007.1982 - a million people march in New York City

International Day of Nuclear Disarmament protests were held on June 20, 1983 at 50 sites across the United States. There were many

Greater Media ''Examiner'', June 28, 2007.

''

''The TriValley Herald'', August 11, 2003. and transportation of nuclear waste from the

About CCNS

/ref> Some scientists and engineers have expressed reservations about nuclear power, including:

The Death of Environmentalism

( Michael Shellenberger and Ted Nordhaus, 2004) American environmentalism has been remarkably successful in protecting the air, water, and large stretches of wilderness in North America and Europe, but these environmentalists have stagnated as a vital force for cultural and political change. Shellenberger and Nordhaus wrote, "Today environmentalism is just another special interest. Evidence for this can be found in its concepts, its proposals, and its reasoning. What stands out is how arbitrary environmental leaders are about what gets counted and what doesn't as 'environmental.' Most of the movement's leading thinkers, funders, and advocates do not question their most basic assumptions about who we are, what we stand for, and what it is that we should be doing." Their essay was followed by a speech in San Francisco called "Is Environmentalism Dead?" by former Sierra Club President, Adam Werbach, who argued for the evolution of environmentalism into a more expansive, relevant and powerful progressive politics. Werbach endorsed building an environmental movement that is more relevant to average Americans and controversially chose to lead Wal-Mart's effort to take sustainability mainstream. These "post-environmental movement" thinkers argue that the ecological crises the human species faces in the 21st century are qualitatively different from the problems the environmental movement was created to address in the 1960s and 1970s. They argue that climate change and

Environmentalists became much more influential in American politics after the creation or strengthening of numerous US environmental laws, including the Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act and the formation of the

Environmentalists became much more influential in American politics after the creation or strengthening of numerous US environmental laws, including the Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act and the formation of the

The organized environmental movement is represented by a wide range of

The organized environmental movement is represented by a wide range of non-governmental organization

A non-governmental organization (NGO) or non-governmental organisation (see American and British English spelling differences#-ise, -ize (-isation, -ization), spelling differences) is an organization that generally is formed independent from g ...

s or NGOs that seek to address environmental issues in the United States. They operate on local, national, and international scales. Environmental NGOs vary widely in political views and in the ways they seek to influence the environmental policy of the United States and other governments.

The environmental movement today consists of both large national groups and also many smaller local groups with local concerns. Some resemble the old U.S. conservation movement - whose modern expression is The Nature Conservancy, Audubon Society and National Geographic Society - American organizations with a worldwide influence. Increasingly that movement is organized around addressing climate change in the United States alongside interrelated issues like climate justice and broader environmental justice

Environmental justice is a social movement to address the unfair exposure of poor and marginalized communities to harms from hazardous waste, resource extraction, and other land uses.Schlosberg, David. (2007) ''Defining Environmental Justice ...

issues.

Issues

Scope of the movement

* The earlyConservation movement

The conservation movement, also known as nature conservation, is a political, environmental, and social movement that seeks to manage and protect natural resources, including animal, fungus, and plant species as well as their habitat for the f ...

, which began in the late 19th century, included fisheries and wildlife management

Wildlife management is the management process influencing interactions among and between wildlife, its habitats and people to achieve predefined impacts. It attempts to balance the needs of wildlife with the needs of people using the best availab ...

, water, soil conservation and sustainable forestry. Today it includes sustainable yield of natural resources, preservation of wilderness areas and biodiversity

Biodiversity or biological diversity is the variety and variability of life on Earth. Biodiversity is a measure of variation at the genetic ('' genetic variability''), species ('' species diversity''), and ecosystem ('' ecosystem diversity' ...

.

* The modern Environmental movement, which began in the 1960s with concern about air and water pollution, became broader in scope to include all landscapes and human activities. See List of environmental issues.

* Environmental health movement dating at least to Progressive Era

The Progressive Era (late 1890s – late 1910s) was a period of widespread social activism and political reform across the United States focused on defeating corruption, monopoly, waste and inefficiency. The main themes ended during Am ...

(the 1890s - 1920s) urban reforms including clean water supply, more efficient removal of raw sewage and reduction in crowded and unsanitary living conditions. Today Environmental health is more related to nutrition, preventive medicine, ageing well and other concerns specific to the human body's well-being.

* Sustainability movement which started in the 1980s focused on Gaia theory, value of Earth and other interrelations between human sciences and human responsibilities. Its spinoff deep ecology was more spiritual but often claimed to be science.

* Environmental justice

Environmental justice is a social movement to address the unfair exposure of poor and marginalized communities to harms from hazardous waste, resource extraction, and other land uses.Schlosberg, David. (2007) ''Defining Environmental Justice ...

is a movement that began in the U.S. in the 1980s and seeks an end to environmental racism

Environmental racism or ecological apartheid is a form of institutional racism leading to landfills, incinerators, and hazardous waste disposal being disproportionally placed in communities of colour. Internationally, it is also associated with ...

. Often, low-income and minority communities are located close to highways, garbage dumps, and factories, where they are exposed to greater pollution and environmental health risk than the rest of the population. The Environmental Justice movement seeks to link "social" and "ecological" environmental concerns, while at the same time keeping environmentalists conscious of the dynamics in their own movement, i.e. racism, sexism, homophobia, classicism, and other malaises of the dominant culture.

As public awareness and the environmental sciences have improved in recent years, environmental issues have broadened to include key concepts such as "sustainability

Specific definitions of sustainability are difficult to agree on and have varied in the literature and over time. The concept of sustainability can be used to guide decisions at the global, national, and individual levels (e.g. sustainable livin ...

" and also new emerging concerns such as ozone depletion, global warming

In common usage, climate change describes global warming—the ongoing increase in global average temperature—and its effects on Earth's climate system. Climate variability and change, Climate change in a broader sense also includes ...

, acid rain, land use

Land use involves the management and modification of natural environment or wilderness into built environment such as settlements and semi-natural habitats such as arable fields, pastures, and managed woods. Land use by humans has a long his ...

and biogenetic pollution.

Environmental movements often interact or are linked with other social movements, e.g. for peace, human rights, and animal rights

Animal rights is the philosophy according to which many or all sentient animals have moral worth that is independent of their utility for humans, and that their most basic interests—such as avoiding suffering—should be afforded the sa ...

; and against nuclear weapons and/or nuclear power, endemic diseases, poverty, hunger, etc.

Some US colleges are now going green by signing the "President's Climate Commitment," a document that a college President can sign to enable said colleges to practice environmentalism by switching to solar power, etc.

History

Early European settlers came to the United States brought from Europe the concept of the commons. In the colonial era, access to natural resources was allocated by individual towns, and disputes over fisheries or land use were resolved at the local level. Changing technologies, however, strained traditional ways of resolving disputes of resource use, and local governments had limited control over powerful special interests. For example, the damming of rivers for mills cut off upriver towns from fisheries; logging and clearing of forest in watersheds harmed local fisheries downstream. In New England, many farmers became uneasy as they noticed clearing of the forest changed stream flows and a decrease in bird population which helped control insects and other pests. These concerns become widely known with the publication of Man and Nature (1864) byGeorge Perkins Marsh

George Perkins Marsh (March 15, 1801July 23, 1882), an American diplomat and philologist, is considered by some to be America's first environmentalist and by recognizing the irreversible impact of man's actions on the earth, a precursor to the ...

. The environmental impact method of analysis is generally the main mode for determining what issues the environmental movement is involved in. This model is used to determine how to proceed in situations that are detrimental to the environment by choosing the way that is least damaging and has the fewest lasting implications.

Conservation movement

Conservation first became a national issue during theprogressive era

The Progressive Era (late 1890s – late 1910s) was a period of widespread social activism and political reform across the United States focused on defeating corruption, monopoly, waste and inefficiency. The main themes ended during Am ...

's conservation movement

The conservation movement, also known as nature conservation, is a political, environmental, and social movement that seeks to manage and protect natural resources, including animal, fungus, and plant species as well as their habitat for the f ...

(1890s - 1920s). The early national conservation movement shifted emphasis to scientific management which favored larger enterprises and control began to shift from local governments to the states and the federal government.(Judd) Some writers credit sportsmen, hunters and fishermen with the increasing influence of the conservation movement. In the 1870s sportsman magazines such as American Sportsmen, Forest and Stream, and Field and Stream

''Field & Stream'' (''F&S'' for short) is an American online magazine focusing on hunting, fishing and other outdoor activities. The magazine was a print publication between 1895 and 2015 and became an online-only publication from 2020.

History ...

are seen as leading to the growth of the conservation movement.(Reiger) This conservation movement also urged the establishment of state and national parks and forests, wildlife refuges, and national monuments intended to preserve noteworthy natural features.

Conservation groups focus primarily on an issue that's origins are rooted in general expansion. As Industrialization

Industrialisation ( alternatively spelled industrialization) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive re-organisation of an econ ...

became more prominent as well as the increasing trend towards Urbanization

Urbanization (or urbanisation) refers to the population shift from rural to urban areas, the corresponding decrease in the proportion of people living in rural areas, and the ways in which societies adapt to this change. It is predominantly t ...

the conservative environmental movement began. Contrary to popular belief conservation groups are not against expansion in general, instead, they are concerned with efficiency with resources and land development.

Progressive era

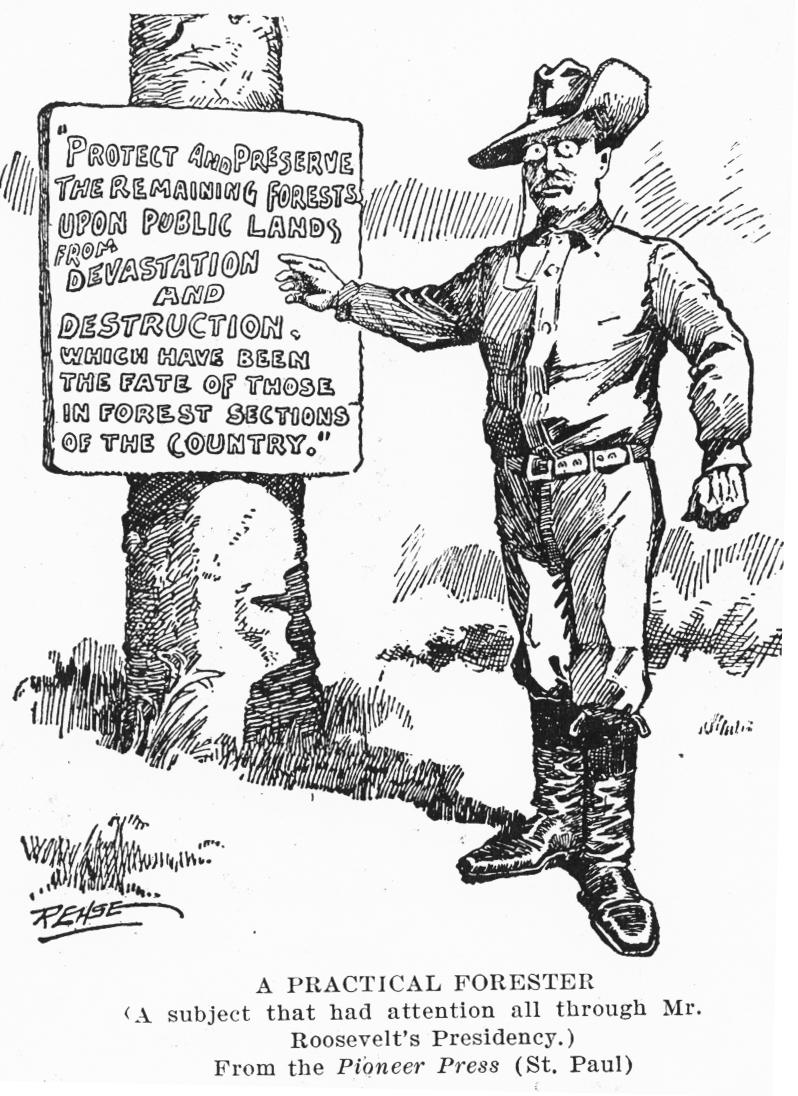

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

and his close ally George Bird Grinnell

George Bird Grinnell (September 20, 1849 – April 11, 1938) was an American anthropologist, historian, naturalist, and writer. Grinnell was born in Brooklyn, New York, and graduated from Yale University with a B.A. in 1870 and a Ph.D. in 1880 ...

, were motivated by the wanton waste that was taking place at the hand of market hunting. This practice resulted in placing a large number of North American game species on the edge of extinction. Roosevelt recognized that the laissez-faire approach of the U.S. Government was too wasteful and inefficient. In any case, they noted, most of the natural resources in the western states were already owned by the federal government. The best course of action, they argued, was a long-term plan devised by national experts to maximize the long-term economic benefits of natural resources. To accomplish the mission, Roosevelt and Grinnell formed the Boone and Crockett Club in 1887. The club was made up of the best minds and influential men of the day. The Boone and Crockett Club's contingency of conservationists, scientists, politicians, and intellectuals became Roosevelt's closest advisers during his march to preserve wildlife and habitat across North America. As president, Theodore Roosevelt became a prominent conservationist, putting the issue high on the national agenda. He worked with all the major figures of the movement, especially his chief advisor on the matter, Gifford Pinchot

Gifford Pinchot (August 11, 1865October 4, 1946) was an American forester and politician. He served as the fourth chief of the U.S. Division of Forestry, as the first head of the United States Forest Service, and as the 28th governor of Penns ...

. Roosevelt was deeply committed to conserving natural resources and is considered to be the nation's first conservation President. He encouraged the Newlands Reclamation Act

The Reclamation Act (also known as the Lowlands Reclamation Act or National Reclamation Act) of 1902 () is a United States federal law that funded irrigation projects for the arid lands of 20 states in the American West.

The act at first covere ...

of 1902 to promote federal construction of dams to irrigate small farms and placed under federal protection. Roosevelt set aside more Federal land for national park

A national park is a natural park in use for conservation purposes, created and protected by national governments. Often it is a reserve of natural, semi-natural, or developed land that a sovereign state declares or owns. Although individua ...

s and nature preserves than all of his predecessors combined.

Roosevelt established the United States Forest Service

The United States Forest Service (USFS) is an agency of the U.S. Department of Agriculture that administers the nation's 154 national forests and 20 national grasslands. The Forest Service manages of land. Major divisions of the agency inc ...

, signed into law the creation of five National Parks, and signed the 1906 Antiquities Act, under which he proclaimed 18 new U.S. National Monuments. He also established the first 51 Bird Reserves, four Game Preserves, and 150 National Forests

A state forest or national forest is a forest that is administered or protected by some agency of a sovereign state, sovereign or federated state, or territory (country subdivision), territory.

Background

The precise application of the terms va ...

, including Shoshone National Forest

Shoshone National Forest ( ) is the first Federal government of the United States, federally protected United States National Forest, National Forest in the United States and covers nearly in the U.S. state, state of Wyoming. Originally a part ...

, the nation's first. The area of the United States that he placed under public protection totals approximately .

Gifford Pinchot

Gifford Pinchot (August 11, 1865October 4, 1946) was an American forester and politician. He served as the fourth chief of the U.S. Division of Forestry, as the first head of the United States Forest Service, and as the 28th governor of Penns ...

had been appointed by McKinley as chief of Division of Forestry in the Department of Agriculture. In 1905, his department gained control of the national forest reserves. Pinchot promoted private use (for a fee) under federal supervision. In 1907, Roosevelt designated of new national forests just minutes before a deadline.

In May 1908, Roosevelt sponsored the Conference of Governors held in the White House, with a focus on natural resources and their most efficient use. Roosevelt delivered the opening address: "Conservation as a National Duty."

In 1903 Roosevelt toured the Yosemite Valley with John Muir

John Muir ( ; April 21, 1838December 24, 1914), also known as "John of the Mountains" and "Father of the National Parks", was an influential Scottish-American naturalist, author, environmental philosopher, botanist, zoologist, glaciologist ...

, who had a very different view of conservation and tried to minimize commercial use of water resources and forests. Working through the Sierra Club

The Sierra Club is an environmental organization with chapters in all 50 United States, Washington D.C., and Puerto Rico. The club was founded on May 28, 1892, in San Francisco, California, by Scottish-American preservationist John Muir, w ...

he founded, Muir succeeded in 1905 in having Congress transfer the Mariposa Grove and Yosemite Valley to the National Park Service

The National Park Service (NPS) is an List of federal agencies in the United States, agency of the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government within the United States Department of the Interior, U.S. Department of ...

. While Muir wanted nature preserved for the sake of pure beauty, Roosevelt subscribed to Pinchot's formulation, "to make the forest produce the largest amount of whatever crop or service will be most useful, and keep on producing it for generation after generation of men and trees." Muir and the Sierra Club vehemently opposed the damming of the Hetch Hetchy Valley in Yosemite in order to provide water to the city of San Francisco. Roosevelt and Pinchot supported the dam, as did President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of P ...

. The Hetch Hetchy dam was finished in 1923 and is still in operation, but the Sierra Club still wants to tear it down.

Other influential conservationists of the Progressive Era

The Progressive Era (late 1890s – late 1910s) was a period of widespread social activism and political reform across the United States focused on defeating corruption, monopoly, waste and inefficiency. The main themes ended during Am ...

included George Bird Grinnell

George Bird Grinnell (September 20, 1849 – April 11, 1938) was an American anthropologist, historian, naturalist, and writer. Grinnell was born in Brooklyn, New York, and graduated from Yale University with a B.A. in 1870 and a Ph.D. in 1880 ...

(a prominent sportsman who founded the Boone and Crockett Club), the Izaak Walton League and John Muir

John Muir ( ; April 21, 1838December 24, 1914), also known as "John of the Mountains" and "Father of the National Parks", was an influential Scottish-American naturalist, author, environmental philosopher, botanist, zoologist, glaciologist ...

, the founder of the Sierra Club

The Sierra Club is an environmental organization with chapters in all 50 United States, Washington D.C., and Puerto Rico. The club was founded on May 28, 1892, in San Francisco, California, by Scottish-American preservationist John Muir, w ...

in 1892. Conservationists organized the National Parks Conservation Association, the Audubon Society, and other groups that still remain active.

New Deal

Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

(1933–45), like his cousin Theodore Roosevelt, was an ardent conservationist. He used numerous programs of the departments of Agriculture and Interior to end wasteful land-use, mitigate the effects of the Dust Bowl

The Dust Bowl was a period of severe dust storms that greatly damaged the ecology and agriculture of the American and Canadian prairies during the 1930s. The phenomenon was caused by a combination of both natural factors (severe drought) an ...

, and efficiently develop natural resources in the West. One of the most popular of all New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Con ...

programs was the Civilian Conservation Corps

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was a voluntary government work relief program that ran from 1933 to 1942 in the United States for unemployed, unmarried men ages 18–25 and eventually expanded to ages 17–28. The CCC was a major part o ...

(1933–1943), which sent two million poor young men to work in rural and wilderness areas, primarily on conservation projects.

Post-1945

After World War II increasing encroachment on wilderness land evoked the continued resistance of conservationists, who succeeded in blocking a number of projects in the 1950s and 1960s, including the proposed Bridge Canyon Dam that would have backed up the waters of the Colorado River into the Grand Canyon National Park. The Inter-American Conference on the Conservation of Renewable Natural Resources met in 1948 as a collection of nearly 200 scientists from all over the Americans forming the trusteeship principle that: "No generation can exclusively own the renewable resources by which it lives. We hold the commonwealth in trust for prosperity, and to lessen or destroy it is to commit treason against the future"Beginning of the modern movement

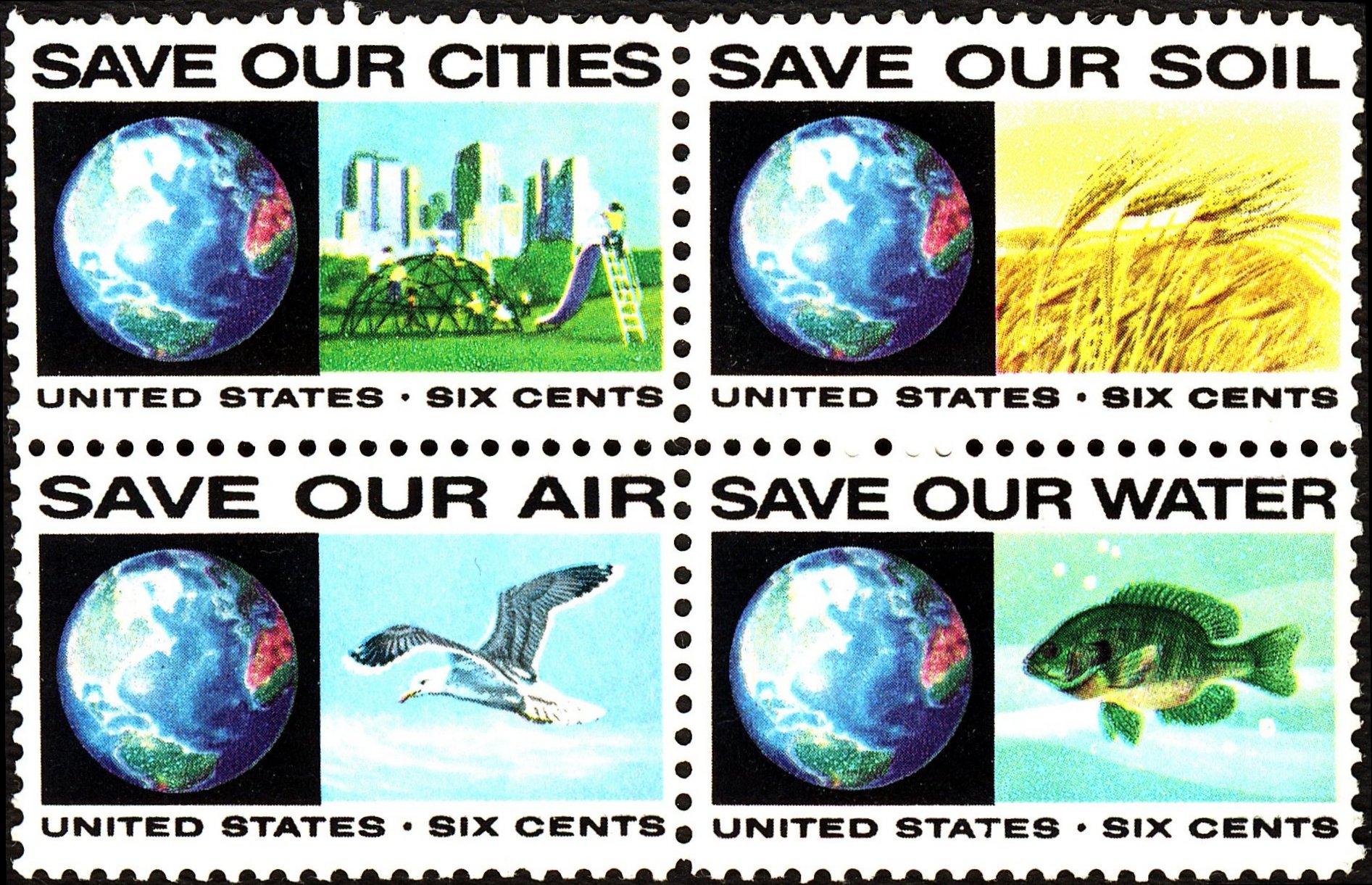

During the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, several events occurred which raised the public awareness of harm to the environment caused by man. In 1954, the 23 man crew of the Japanese fishing vessel '' Lucky Dragon'' was exposed to radioactive fallout from a hydrogen bomb test at Bikini Atoll. By 1969, the public reaction to an ecologically catastrophic oil spill from an offshore well in California's Santa Barbara Channel,

During the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, several events occurred which raised the public awareness of harm to the environment caused by man. In 1954, the 23 man crew of the Japanese fishing vessel '' Lucky Dragon'' was exposed to radioactive fallout from a hydrogen bomb test at Bikini Atoll. By 1969, the public reaction to an ecologically catastrophic oil spill from an offshore well in California's Santa Barbara Channel, Barry Commoner

Barry Commoner (May 28, 1917 – September 30, 2012) was an American cellular biologist, college professor, and politician. He was a leading ecologist and among the founders of the modern environmental movement. He was the director of th ...

's protest against nuclear testing, along with Rachel Carson's 1962 book ''Silent Spring

''Silent Spring'' is an environmental science book by Rachel Carson. Published on September 27, 1962, the book documented the environmental harm caused by the indiscriminate use of pesticides. Carson accused the chemical industry of spreading d ...

'', and Paul R. Ehrlich's '' The Population Bomb'' (1968) all added anxiety about the environment. Pictures of Earth from space emphasized that the earth was small and fragile.

As the public became more aware of environmental issues, concern about air pollution

Air pollution is the contamination of air due to the presence of substances in the atmosphere that are harmful to the health of humans and other living beings, or cause damage to the climate or to materials. There are many different type ...

, water pollution

Water pollution (or aquatic pollution) is the contamination of water bodies, usually as a result of human activities, so that it negatively affects its uses. Water bodies include lakes, rivers, oceans, aquifers, reservoirs and groundwater. Wate ...

, solid waste disposal, dwindling energy resources, radiation, pesticide poisoning (particularly use of DDT as described in Carson's influential ''Silent Spring''), noise pollution, and other environmental problems engaged a broadening number of sympathizers. That public support for environmental concerns was widespread became clear in the Earth Day demonstrations of 1970.

Several books after the middle of the 20th century contributed to the rise of American environmentalism (as distinct from the longer-established conservation movement), especially among college and university students and the more literate public. One was the publication of the first textbook on ecology

Ecology () is the study of the relationships between living organisms, including humans, and their physical environment. Ecology considers organisms at the individual, population, community, ecosystem, and biosphere level. Ecology overl ...

, ''Fundamentals of Ecology,'' by Eugene Odum and Howard Odum, in 1953. Another was the appearance of the Carson's 1962 best-seller ''Silent Spring.'' Her book brought about a whole new interpretation of pesticides by exposing their harmful effects in nature. From this book, many began referring to Carson as the "mother of the environmental movement". Another influential development was a 1965 lawsuit, ''Scenic Hudson Preservation Conference v. Federal Power Commission,'' opposing the construction of a power plant on Storm King Mountain in New York (state)

New York, officially the State of New York, is a state in the Northeastern United States. It is often called New York State to distinguish it from its largest city, New York City. With a total area of , New York is the 27th-largest U.S. stat ...

, which is said to have given birth to modern United States environmental law. The wide popularity of ''The Whole Earth Catalogs'', starting in 1968, was quite influential among the younger, hands-on, activist generation of the 1960s and 1970s. Recently, in addition to opposing environmental degradation and protecting wilderness, an increased focus on coexisting with natural biodiversity has appeared, a strain that is apparent in the movement for sustainable agriculture and in the concept of Reconciliation Ecology.

During his time as U.S President, Lyndon Johnson would sign over 300 environment protection measures into law. This was credited as forming the legal basis of the modern environmental movement.

Wilderness preservation

In the modern wilderness preservation movement, important philosophical roles are played by the writings ofJohn Muir

John Muir ( ; April 21, 1838December 24, 1914), also known as "John of the Mountains" and "Father of the National Parks", was an influential Scottish-American naturalist, author, environmental philosopher, botanist, zoologist, glaciologist ...

who had been activist in the late 19th and early 20th century. Along with Muir perhaps most influential in the modern movement is Henry David Thoreau who published Walden

''Walden'' (; first published in 1854 as ''Walden; or, Life in the Woods'') is a book by American transcendentalist writer Henry David Thoreau. The text is a reflection upon the author's simple living in natural surroundings. The work is part ...

in 1854. Also important was forester and ecologist Aldo Leopold, one of the founders of the Wilderness Society in 1935, who wrote a classic of nature observation and ethical philosophy, ''A Sand County Almanac

''A Sand County Almanac: And Sketches Here and There'' is a 1949 non-fiction book by American ecologist, forester, and environmentalist Aldo Leopold. Describing the land around the author's home in Sauk County, Wisconsin, the collection of es ...

'', (1949).

There is also a growing movement of campers and other people who enjoy outdoor recreation activities to help preserve the environment while spending time in the wilderness.

Anti-nuclear movement

The anti-nuclear movement in the United States consists of more than 80 anti-nuclear groups that have acted to opposenuclear power

Nuclear power is the use of nuclear reactions to produce electricity. Nuclear power can be obtained from nuclear fission, nuclear decay and nuclear fusion reactions. Presently, the vast majority of electricity from nuclear power is produced ...

or nuclear weapons

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bom ...

, or both, in the United States. These groups include the Abalone Alliance, Clamshell Alliance, Institute for Energy and Environmental Research, Nuclear Information and Resource Service, and Physicians for Social Responsibility. The anti-nuclear movement has delayed construction or halted commitments to build some new nuclear plants, and has pressured the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to enforce and strengthen the safety regulations for nuclear power plants.

Anti-nuclear protests reached a peak in the 1970s and 1980s and grew out of the environmental movement. Campaigns which captured national public attention involved the Calvert Cliffs Nuclear Power Plant, Seabrook Station Nuclear Power Plant

The Seabrook Nuclear Power Plant, more commonly known as Seabrook Station, is a nuclear power plant located in Seabrook, New Hampshire, United States, approximately north of Boston and south of Portsmouth. It has operated since 1990. With i ...

, Diablo Canyon Power Plant, Shoreham Nuclear Power Plant, and Three Mile Island. On June 12, 1982, one million people demonstrated in New York City's Central Park

Central Park is an urban park in New York City located between the Upper West Side, Upper West and Upper East Sides of Manhattan. It is the List of New York City parks, fifth-largest park in the city, covering . It is the most visited urban par ...

against nuclear weapons

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bom ...

and for an end to the cold war arms race. It was the largest anti-nuclear protest

A protest (also called a demonstration, remonstration or remonstrance) is a public expression of objection, disapproval or dissent towards an idea or action, typically a political one.

Protests can be thought of as acts of coopera ...

and the largest political demonstration in American history.Jonathan SchellThe Spirit of June 12

''The Nation'', July 2, 2007.1982 - a million people march in New York City

International Day of Nuclear Disarmament protests were held on June 20, 1983 at 50 sites across the United States. There were many

Nevada Desert Experience

Nevada Desert Experience is a name for the movement to stop U.S. nuclear weapons testing that came into use in the middle 1980s. It is also the name of an anti-nuclear organization which continues to create public events to question the moralit ...

protests and peace camps at the Nevada Test Site during the 1980s and 1990s.

More recent campaigning by anti-nuclear groups has related to several nuclear power plants including the Enrico Fermi Nuclear Power Plant,Fermi 3 opposition takes legal action to block new nuclear reactorIndian Point Energy Center

Indian Point Energy Center (I.P.E.C.) is a three-unit nuclear power plant station located in Buchanan, just south of Peekskill, in Westchester County, New York. It sits on the east bank of the Hudson River, about north of Midtown Manhattan. ...

, Oyster Creek Nuclear Generating Station,Oyster Creek's time is up, residents tell boardGreater Media ''Examiner'', June 28, 2007.

Pilgrim Nuclear Generating Station

Pilgrim Nuclear Power Station (PNPS) is a decommissioned nuclear power plant in Massachusetts in the Manomet section of Plymouth on Cape Cod Bay, south of the tip of Rocky Point and north of Priscilla Beach. Like many similar plants, it was co ...

, Salem Nuclear Power Plant, and Vermont Yankee Nuclear Power Plant. There have also been campaigns relating to the Y-12 Nuclear Weapons Plant, the Idaho National Laboratory, proposed Yucca Mountain nuclear waste repository, the Hanford Site, the Nevada Test Site,22 Arrested in Nuclear Protest''

The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'', August 10, 1989. Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) is a federal research facility in Livermore, California, United States. The lab was originally established as the University of California Radiation Laboratory, Livermore Branch in 1952 in response ...

,Hundreds Protest at Livermore Lab''The TriValley Herald'', August 11, 2003. and transportation of nuclear waste from the

Los Alamos National Laboratory

Los Alamos National Laboratory (often shortened as Los Alamos and LANL) is one of the sixteen research and development laboratories of the United States Department of Energy (DOE), located a short distance northwest of Santa Fe, New Mexico, i ...

.Concerned Citizens for Nuclear Safety (undated)About CCNS

/ref> Some scientists and engineers have expressed reservations about nuclear power, including:

Barry Commoner

Barry Commoner (May 28, 1917 – September 30, 2012) was an American cellular biologist, college professor, and politician. He was a leading ecologist and among the founders of the modern environmental movement. He was the director of th ...

, S. David Freeman, John Gofman, Arnold Gundersen, Mark Z. Jacobson, Amory Lovins

Amory Bloch Lovins (born November 13, 1947) is an American writer, physicist, and former chairman/chief scientist of the Rocky Mountain Institute. He has written on energy policy and related areas for four decades, and served on the US Nationa ...

, Arjun Makhijani, Gregory Minor

Gregory Charles Minor was one of three American middle-management engineers (known as the GE Three) who resigned from the General Electric nuclear reactor division in 1976 to protest against the use of nuclear power in the United States. A native ...

, Joseph Romm

Joseph J. Romm (born June 27, 1960) is an American author, editor, physicist and climate expert, who advocates reducing greenhouse gas emissions to limit global warming and increasing energy security through energy efficiency, green energy techno ...

and Benjamin K. Sovacool. Scientists who have opposed nuclear weapons include Linus Pauling and Eugene Rabinowitch.

Antitoxics groups

Antitoxics groups are a subgroup that is affiliated with the Environmental Movement in the United States, that is primarily concerned with the effects that cities and their by-products have on humans. This aspect of the movement is a self-proclaimed "movement of housewives". Concern around the issues of groundwater contamination and air pollution rose in the early 1980s and individuals involved in antitoxics groups claim that they are concerned for the health of their families. A prominent case can be seen in theLove Canal

Love Canal is a neighborhood in Niagara Falls, New York, United States, infamous as the location of a landfill that became the site of an enormous environmental disaster in the 1970s. Decades of dumping toxic chemicals harmed the health of hun ...

Homeowner's association (LCHA); in this case, a housing development was built on a site that had been used for toxic dumping by the Hooker Chemical Company. As a result of this dumping, the residents had symptoms of skin irritation, Lois Gibbs, a resident of the development, started a grassroots campaign for reparations. Eventual success led to the government having to purchase homes that were sold in the development.

Federal legislation in the 1970s

Prior to the 1970s the protection of basic air and water supplies was a matter mainly left to each state. During the 1970s, the primary responsibility for clean air and water shifted to the federal government. Growing concerns, both environmental and economic, from cities and towns as well as sportsman and other local groups, and senators such as Maine's Edmund S. Muskie, led to the passage of extensive legislation, notably the Clean Air Act of 1970 and the Water Pollution Control Act Amendments of 1972. Other legislation included the 1970 National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), which established the Council on Environmental Quality; the Marine Protection, Research, and Sanctuaries Act of 1972; the Endangered Species Act of 1973, theSafe Drinking Water Act

The Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) is the principal federal law in the United States intended to ensure safe drinking water for the public. Pursuant to the act, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is required to set standards for drinking w ...

(1974), the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act

The Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA), enacted in 1976, is the principal federal law in the United States governing the disposal of solid waste and hazardous waste.United States. Resource Conservation and Recovery Act. , , ''et seq., ...

(1976), the Water Pollution Control Act Amendments of 1977, which became known as the Clean Water Act, and the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act, commonly known as the Superfund Act

Superfund is a United States federal environmental remediation program established by the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980 (CERCLA). The program is administered by the Environmental Protection Agency ...

(1980). These laws regulated public drinking water systems, toxic substances, pesticides, and ocean dumping; and protected wildlife, wilderness, and wild and scenic rivers. Moreover, the new laws provide for pollution research, standard setting, contaminated site cleanup, monitoring, and enforcement.

The creation of these laws led to a major shift in the environmental movement. Groups such as the Sierra Club shifted focus from local issues to becoming a lobby in Washington and new groups, for example, the Natural Resources Defense Council and Environmental Defense, arose to influence politics as well. (Larson)

Renewed focus on local action

In the 1980s, President Ronald Reagan sought to curtail the scope of environmental protection taking steps such as appointing James G. Watt who was called one of the most "blatantly anti-environmental political appointees". The major environmental groups responded with mass mailings which led to increased membership and donations. The large environmental organization increasingly relied on ties within Washington, D.C. to advance their environmental agenda. At the same time membership in environmental groups became more suburban and urban. Groups such as animal rights and the gun control lobby became linked with environmentalism while sportsmen, farmers and ranchers were no longer influential in the movement. When industry groups lobbied to weaken regulation and a backlash against environmental regulations, the so-called wise use movement gained importance and influence. The wise use movement andanti-environmental

Anti-environmentalism is a movement that favors loose environmental regulation in favor of economic benefits and opposes strict environmental regulation aimed at preserving nature and the planet. Anti-environmentalists seek to persuade the public ...

groups were able to portray environmentalist as out of touch with mainstream values. (Larson)

"Post-environmentalism"

In 2004, with the environmental movement seemingly stalled, some environmentalists started questioning whether "environmentalism" was even a useful political framework. According to a controversial essay titledThe Death of Environmentalism

( Michael Shellenberger and Ted Nordhaus, 2004) American environmentalism has been remarkably successful in protecting the air, water, and large stretches of wilderness in North America and Europe, but these environmentalists have stagnated as a vital force for cultural and political change. Shellenberger and Nordhaus wrote, "Today environmentalism is just another special interest. Evidence for this can be found in its concepts, its proposals, and its reasoning. What stands out is how arbitrary environmental leaders are about what gets counted and what doesn't as 'environmental.' Most of the movement's leading thinkers, funders, and advocates do not question their most basic assumptions about who we are, what we stand for, and what it is that we should be doing." Their essay was followed by a speech in San Francisco called "Is Environmentalism Dead?" by former Sierra Club President, Adam Werbach, who argued for the evolution of environmentalism into a more expansive, relevant and powerful progressive politics. Werbach endorsed building an environmental movement that is more relevant to average Americans and controversially chose to lead Wal-Mart's effort to take sustainability mainstream. These "post-environmental movement" thinkers argue that the ecological crises the human species faces in the 21st century are qualitatively different from the problems the environmental movement was created to address in the 1960s and 1970s. They argue that climate change and

habitat destruction

Habitat destruction (also termed habitat loss and habitat reduction) is the process by which a natural habitat becomes incapable of supporting its native species. The organisms that previously inhabited the site are displaced or dead, thereby ...

are global and more complex, therefore demanding far deeper transformations of the economy, the culture and political life. The consequence of environmentalism's outdated and arbitrary definition, they argue, is a political irrelevancy.

These "politically neutral" groups tend to avoid global conflicts and view the settlement of inter-human conflict as separate from regard for nature – in direct contradiction to the ecology movement and peace movement which have increasingly close links: while Green Parties, Greenpeace

Greenpeace is an independent global campaigning network, founded in Canada in 1971 by Irving Stowe and Dorothy Stowe, immigrant environmental activists from the United States. Greenpeace states its goal is to "ensure the ability of the Earth ...

, and groups like the ACTivist Magazine regard ecology, biodiversity, and an end to non-human extinction as an absolute basis for peace, the local groups may not, and see a high degree of global competition and conflict as justifiable if it lets them preserve their own local uniqueness. However, such groups tend not to "burn out" and to sustain for long periods, even generations, protecting the same local treasures.

Local groups increasingly find that they benefit from collaboration, e.g. on consensus decision-making methods, or making simultaneous policy

The International Simultaneous Policy Organisation (ISPO) is a voluntary organization that promotes the Simultaneous Policy (Simpol) campaign. It was founded by British businessman, John Bunzl, in 2000.About Simpol-UKuk.simpol.org - About Simpol ...

, or relying on common legal resources, or even sometimes a common glossary. However, the differences between the various groups that make up the modern environmental movement tend to outweigh such similarities, and they rarely co-operate directly except on a few major global questions. In a notable exception, over 1,000 local groups from around the country united for a single day of action as part of the Step It Up 2007 campaign for real solutions to global warming.

Groups such as The Bioregional Revolution are calling on the need to bridge these differences, as the converging problems of the 21st century they claim compel the people to unite and to take decisive action. They promote bioregionalism, permaculture, and local economies as solutions to these problems, overpopulation, global warming

In common usage, climate change describes global warming—the ongoing increase in global average temperature—and its effects on Earth's climate system. Climate variability and change, Climate change in a broader sense also includes ...

, global epidemics, and water scarcity

Water scarcity (closely related to water stress or water crisis) is the lack of fresh water resources to meet the standard water demand. There are two types of water scarcity: physical or economic water scarcity. Physical water scarcity is whe ...

, but most notably to " peak oil" – the prediction that the country is likely to reach a maximum in global oil production which could spell drastic changes in many aspects of the residents' everyday lives.

Environmental rights

Many environmental lawsuits turn on the question of who has standing; are the legal issues limited to property owners, or does the general public have a right to intervene? Christopher D. Stone's 1972 essay, "Should trees have standing?" seriously addressed the question of whether natural objects themselves should have legal rights, including the right to participate in lawsuits. Stone suggested that there was nothing absurd in this view, and noted that many entities now regarded as having legal rights were, in the past, regarded as "things" that were regarded as legally rightless; for example, aliens, children and women. His essay is sometimes regarded as an example of the fallacy of hypostatization. One of the earliest lawsuits to establish that citizens may sue for environmental and aesthetic harms was Scenic Hudson Preservation Conference v. Federal Power Commission, decided in 1965 by the Second Circuit Court of Appeals. The case helped halt the construction of a power plant on Storm King Mountain in New York State. See also United States environmental law and David Sive, an attorney who was involved in the case.Conservation biology

Conservation biology is the study of the conservation of nature and of Earth's biodiversity with the aim of protecting species, their habitats, and ecosystems from excessive rates of extinction and the erosion of biotic interactions. It is an ...

is an important and rapidly developing field. One way to avoid the stigma of an "ism" was to evolve early anti-nuclear groups into the more scientific Green Parties, sprout new NGOs such as Greenpeace and Earth Action, and devoted groups to protecting global biodiversity and preventing global warming and climate change. But in the process, much of the emotional appeal, and many of the original aesthetic goals were lost. Nonetheless, these groups have well-defined ethical and political views, backed by science.

Criticisms

Some people are skeptical of the environmental movement and feel that it is more deeply rooted in politics than science. Although there have been serious debates about climate change and effects of some pesticides and herbicides that mimic animal sex steroids, science has shown that some of the claims of environmentalists have credence. Claims made by environmentalists may be perceived as veiled attacks on industry and globalization rather than legitimate environmental concerns. Detractors note that a significant number of environmental theories and predictions have been inaccurate and suggest that the regulations recommended by environmentalists will more likely harm society rather than help nature. Novelist and Harvard Medical School graduate Michael Crichton appeared before the U.S. Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works on September 28, 2005, to address such concerns and recommended the employment of double-blind experimentation in environmental research. Crichton suggested that because environmental issues are so political in nature, policymakers need neutral, conclusive data to base their decisions on, rather than conjecture and rhetoric, and double-blind experiments are the most efficient way to achieve that aim. A consistent theme acknowledged by both supporters and critics (though more commonly vocalized by critics) of the environmental movement is that we know very little about the Earth we live in. Most fields of environmental studies are relatively new, and therefore what research we have is limited and does not date far enough back for us to completely understand long-term environmental trends. This has led a number of environmentalists to support the use of theprecautionary principle

The precautionary principle (or precautionary approach) is a broad epistemological, philosophical and legal approach to innovations with potential for causing harm when extensive scientific knowledge on the matter is lacking. It emphasizes cauti ...

in policy-making, which ultimately asserts that we don't know how certain actions may affect the environment and because there is reason to believe they may cause more harm than good we should refrain from such actions.

Elitist

In the December 1994 ''Wild Forest Review,'' Alexander Cockburn and Jeffrey St. Clair wrote "The mainstream environmental movement was elitist, highly paid, detached from the people, indifferent to the working class, and a firm ally of big government.…The environmental movement is now accurately perceived as just another well-financed and cynical special interest group, its rancid infrastructure supported by Democratic Party operatives and millions in grants from corporate foundations."Wilderness myth

Historians have criticized the modern environmental movement for having romantic idealizations of wilderness. William Cronon writes "wilderness serves as the unexamined foundation on which so many of the quasi-religious values of modern environmentalism rest." Cronon claims that "to the extent that we live in an urban-industrial civilization but at the same time pretend to ourselves that our real home is in the wilderness, to just that extent we give ourselves permission to evade responsibility for the lives we actually lead." Similarly Michael Pollan has argued that the wilderness ethic leads people to dismiss areas whose wildness is less than absolute. In his book ''Second Nature,'' Pollan writes that "once a landscape is no longer 'virgin' it is typically written off as fallen, lost to nature, irredeemable."Debates within the movement

Within the environmental movement, an ideological debate has taken place between those with an ecocentric viewpoint and an anthropocentric viewpoint. The anthropocentric view has been seen as the conservationist approach to the environment with nature viewed, at least in part, as a resource to be used by man. In contrast to the conservationist approach the ecocentric view, associated withJohn Muir

John Muir ( ; April 21, 1838December 24, 1914), also known as "John of the Mountains" and "Father of the National Parks", was an influential Scottish-American naturalist, author, environmental philosopher, botanist, zoologist, glaciologist ...

, Henry David Thoreau and William Wordsworth referred to as the preservationist movement. This approach sees nature in a more spiritual way. Many environmental historians consider the split between John Muir and Gifford Pinchot

Gifford Pinchot (August 11, 1865October 4, 1946) was an American forester and politician. He served as the fourth chief of the U.S. Division of Forestry, as the first head of the United States Forest Service, and as the 28th governor of Penns ...

. During the preservation/conservation debate, the term preservationist becomes to be seen as a pejorative term.

While the ecocentric view focused on biodiversity and wilderness protection the anthropocentric view focuses on urban pollution and social justice. Some environmental writers, for example, William Cronon have criticized the ecocentric view as have a dualist view as a man being separate from nature. Critics of the anthropocentric viewpoint contend that the environmental movement has been taken over by so-called leftist

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in soc ...

with an agenda beyond environmental protection.

Environmentalism and politics

Environmentalists became much more influential in American politics after the creation or strengthening of numerous US environmental laws, including the Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act and the formation of the

Environmentalists became much more influential in American politics after the creation or strengthening of numerous US environmental laws, including the Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act and the formation of the United States Environmental Protection Agency

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is an independent executive agency of the United States federal government tasked with environmental protection matters. President Richard Nixon proposed the establishment of EPA on July 9, 1970; it ...

(EPA) in 1970. These successes were followed by the enactment of a whole series of laws regulating waste

Waste (or wastes) are unwanted or unusable materials. Waste is any substance discarded after primary use, or is worthless, defective and of no use. A by-product, by contrast is a joint product of relatively minor economic value. A waste pr ...

(Resource Conservation and Recovery Act

The Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA), enacted in 1976, is the principal federal law in the United States governing the disposal of solid waste and hazardous waste.United States. Resource Conservation and Recovery Act. , , ''et seq., ...

), toxic substances

Poison is a chemical substance that has a detrimental effect to life. The term is used in a wide range of scientific fields and industries, where it is often specifically defined. It may also be applied colloquially or figuratively, with a broa ...

( Toxic Substances Control Act), pesticides

Pesticides are substances that are meant to pest control, control pest (organism), pests. This includes herbicide, insecticide, nematicide, molluscicide, piscicide, avicide, rodenticide, bactericide, insect repellent, animal repellent, microb ...

(FIFRA: Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act

The Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA) is a United States federal law that set up the basic U.S. system of pesticide regulation to protect applicators, consumers, and the environment. It is administered and regulated by th ...

), clean-up of polluted sites (Superfund

Superfund is a United States federal environmental remediation program established by the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980 (CERCLA). The program is administered by the Environmental Protection Agen ...

), protection of endangered species ( Endangered Species Act), and more.

Fewer environmental laws have been passed in the last decade as corporations and other conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

interests have increased their influence over American politics. Corporate cooperation against environmental lobbyists has been organized by the Wise Use group. At the same time, many environmentalists have been turning toward other means of persuasion, such as working with business, community, and other partners to promote sustainable development. Since the 1970s, coalitions and interests groups have directed themselves along the democrat and republican party lines.>

Much environmental activism is directed towards conservation as well as the prevention or elimination of pollution. However, conservation movement

The conservation movement, also known as nature conservation, is a political, environmental, and social movement that seeks to manage and protect natural resources, including animal, fungus, and plant species as well as their habitat for the f ...

s, ecology movements, peace movement

A peace movement is a social movement which seeks to achieve ideals, such as the ending of a particular war (or wars) or minimizing inter-human violence in a particular place or situation. They are often linked to the goal of achieving world pea ...

s, green parties, green- and eco-anarchists often subscribe to very different ideologies, while supporting the same goals as those who call themselves "environmentalists". To outsiders, these groups or factions can appear to be indistinguishable.

As human population

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, culture ...

and industrial activity continue to increase, environmentalists often find themselves in serious conflict with those who believe that human and industrial activities should not be overly regulated or restricted, such as some libertarians.

Environmentalists often clash with others, particularly "corporate interests," over issues of the management of natural resources

Natural resources are resources that are drawn from nature and used with few modifications. This includes the sources of valued characteristics such as commercial and industrial use, aesthetic value, scientific interest and cultural value. ...

, like in the case of the atmosphere

An atmosphere () is a layer of gas or layers of gases that envelop a planet, and is held in place by the gravity of the planetary body. A planet retains an atmosphere when the gravity is great and the temperature of the atmosphere is low. ...

as a "carbon dump", the focus of climate change

In common usage, climate change describes global warming—the ongoing increase in global average temperature—and its effects on Earth's climate system. Climate change in a broader sense also includes previous long-term changes to ...

, and global warming

In common usage, climate change describes global warming—the ongoing increase in global average temperature—and its effects on Earth's climate system. Climate variability and change, Climate change in a broader sense also includes ...

controversy. They usually seek to protect commonly owned or unowned resources for future generations.

Radical environmentalism

While most environmentalists are mainstream and peaceful, a small minority are more radical in their approach. Adherents ofradical environmentalism

Radical environmentalism is a grass-roots branch of the larger environmental movement that emerged from an ecocentrism-based frustration with the co-option of mainstream environmentalism.

As a movement

Philosophy

The radical environmental mo ...

and ecolog