Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Baroness Pethick-Lawrence on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Baroness Pethick-Lawrence (; 21 October 1867 – 11 March 1954) was a British

Pethick met wealthy barrister Frederick William Lawrence in 1899 at Percy Alden's Mansfield House settlement in

Pethick met wealthy barrister Frederick William Lawrence in 1899 at Percy Alden's Mansfield House settlement in

Lawrence, Emmeline Pethick-, Lady Pethick-Lawrence (1867–1954)

, ''

During a visit to South Africa with her husband, Pethick-Lawrence read about

During a visit to South Africa with her husband, Pethick-Lawrence read about

The Pethick-Lawrences and the Pankhurts also had opposing views on war. Pethick-Lawrence described peace as "the highest effort of the human brain applied to the organisation of the life and being of the peoples of the world on the basis of cooperation." In 1914, she embarked on a speaking tour in America, speaking on the outbreak of

The Pethick-Lawrences and the Pankhurts also had opposing views on war. Pethick-Lawrence described peace as "the highest effort of the human brain applied to the organisation of the life and being of the peoples of the world on the basis of cooperation." In 1914, she embarked on a speaking tour in America, speaking on the outbreak of

Kibbo Kift official history

West London Mission

{{DEFAULTSORT:Pethick-Lawrence, Emmeline 1867 births 1954 deaths Journalists from Bristol English pacifists English suffragists British baronesses British socialist feminists Politicians from Bristol Women of the Victorian era Labour Party (UK) parliamentary candidates Emmeline Women's Social and Political Union Women's International League for Peace and Freedom people Eagle House suffragettes

women's rights

Women's rights are the rights and Entitlement (fair division), entitlements claimed for women and girls worldwide. They formed the basis for the women's rights movement in the 19th century and the feminist movements during the 20th and 21st c ...

activist, suffragist

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise is the right to vote in public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in English, the right to vo ...

and pacifist.

Early life

Pethick-Lawrence was born in 1867 in Clifton,Bristol

Bristol () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city, unitary authority area and ceremonial county in South West England, the most populous city in the region. Built around the River Avon, Bristol, River Avon, it is bordered by t ...

as Emmeline Pethick. Her father, Henry Pethick of Cornish farming stock, was a businessman and merchant of South American hide, who became owner of the ''Weston Gazette'', and a Weston town commissioner. She was the second of 13 children, five who died in infancy, and her younger sister, Dorothy Pethick (the tenth child), was also a suffragist.

Pethick was sent away to the Greystone House boarding school

A boarding school is a school where pupils live within premises while being given formal instruction. The word "boarding" is used in the sense of "room and board", i.e. lodging and meals. They have existed for many centuries, and now extend acr ...

l in Devizes

Devizes () is a market town and civil parish in Wiltshire, England. It developed around Devizes Castle, an 11th-century Norman architecture, Norman castle, and received a charter in 1141. The castle was besieged during the Anarchy, a 12th-cent ...

at the age of eight. She was reluctant to conform from an early age and got into trouble frequently at school. She was then educated at private schools in England, France and Germany.

Early career

From 1891 to 1895, Pethick worked as a "sister of the people" for the West London Methodist Mission at Cleveland Hall, nearFitzroy Square

Fitzroy Square is a Georgian architecture, Georgian garden square, square in London, England. It is the only one in the central London area known as Fitzrovia.

The square is one of the area's main features, this once led to the surrounding di ...

, having been inspired by Walter Besant

Sir Walter Besant (; 14 August 1836 – 9 June 1901) was an English novelist and historian. William Henry Besant was his brother, and another brother, Frank, was the husband of Annie Besant.

Early life and education

The son of wine merchant Wi ...

's book ''The Children of Gibeon'' (1886). She ran a girls' club at the mission with Mary Neal and they became friends and lived together.

In 1895, she and Neal left the mission to co-found the Espérance Club, with support from the evangelical Christian socialist Mark Guy Pearse. The club for young women and girls would not be subject to the constraints of the mission, and could experiment with dance and drama. Pethick also started Maison Espérance, a dressmaking cooperative with a minimum wage, an eight-hour day

The eight-hour day movement (also known as the 40-hour week movement or the short-time movement) was a social movement to regulate the length of a working day, preventing excesses and abuses of working time.

The modern movement originated i ...

and a holiday scheme, and was founder of the Social Settlement for Girls from the East End of London.

Marriage

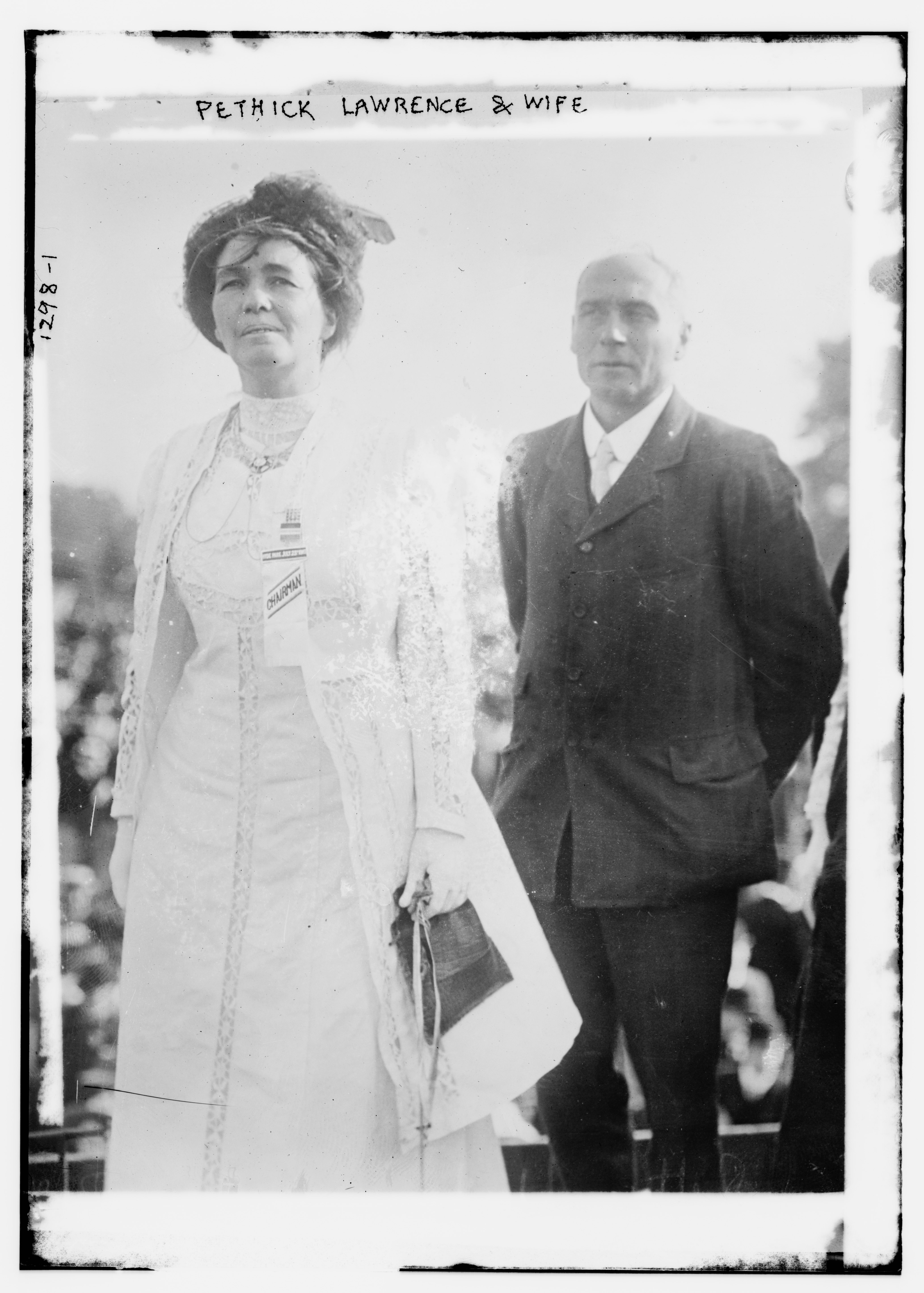

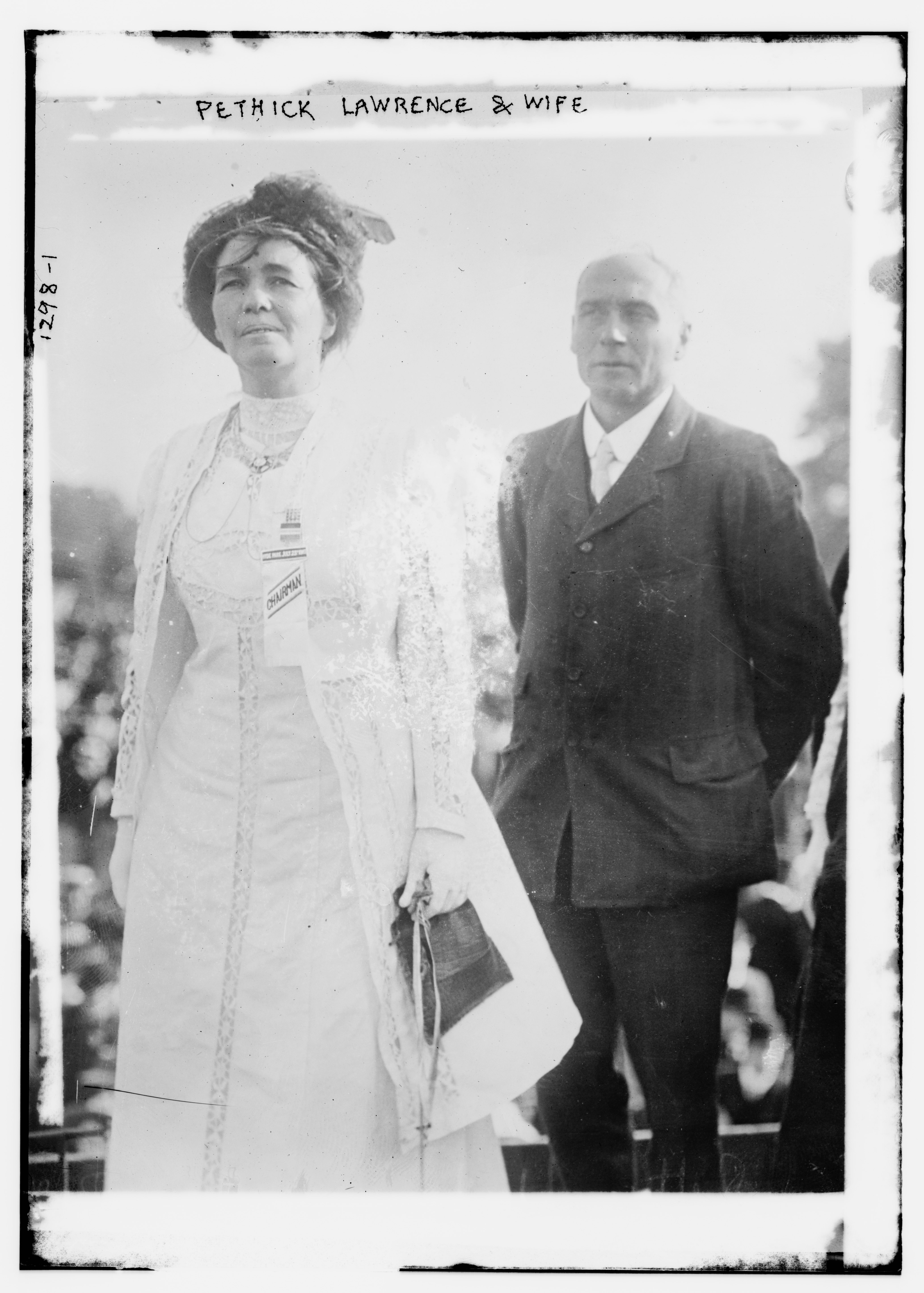

Pethick met wealthy barrister Frederick William Lawrence in 1899 at Percy Alden's Mansfield House settlement in

Pethick met wealthy barrister Frederick William Lawrence in 1899 at Percy Alden's Mansfield House settlement in Canning Town

Canning Town is a town in the London Borough of Newham, East London, England, north of the Royal Victoria Dock. Its urbanisation was largely due to the creation of the dock. The area was part of the ancient parish and County Borough of West Ham, ...

. She feared that a conventional marriage with him would curtail her independence and prevent her from her social service work, so turned down his first marriage proposal. After a second proposal, they married on 2 October 1901 at Canning Town Hall, three weeks before her 34th birthday.

After the marriage, the couple took the hyphenated joint surname Pethick-Lawrence as a gesture of equality, and kept separate bank accounts to give them financial autonomy.Harrison, Brian. (24 September 2004)Lawrence, Emmeline Pethick-, Lady Pethick-Lawrence (1867–1954)

, ''

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from History of the British Isles, British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') ...

,'' Oxford University Press. Accessed 17 November 2007. They moved to Holmwood, near Dorking

Dorking () is a market town in Surrey in South East England about south-west of London. It is in Mole Valley, Mole Valley District and the non-metropolitan district, council headquarters are to the east of the centre. The High Street runs ro ...

and also shared a London flat. Between 1906 and 1912 Holmwood would become a central meeting place for leaders of the suffrage campaign and a refuge where suffragettes could recover from forcible feeding. On their first wedding anniversary, Frederick gave her the key to a private flat on the roof of Clement's Inn for her own private use.

Women's suffrage activism

During a visit to South Africa with her husband, Pethick-Lawrence read about

During a visit to South Africa with her husband, Pethick-Lawrence read about Christabel Pankhurst

Dame Christabel Harriette Pankhurst (; 22 September 1880 – 13 February 1958) was a British suffragette born in Manchester, England. A co-founder of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), she directed Suffragette bombing and arson ca ...

and Annie Kenney

Ann "Annie" Kenney (13 September 1879 – 9 July 1953) was an English working-class suffragette and socialist feminist who became a leading figure in the Women's Social and Political Union. She co-founded its first branch in London with Minnie ...

's protest and unfurling a banner declaring "Votes for Women" at the Manchester Free Trade Hall in October 1905, and their subsequent arrest. Back in Britain, Pethick-Lawrence became a member of the Suffrage Society and was introduced to Emmeline Pankhurst

Emmeline Pankhurst (; Goulden; 15 July 1858 – 14 June 1928) was a British political activist who organised the British suffragette movement and helped women to win in 1918 the women's suffrage, right to vote in United Kingdom of Great Brita ...

by Keir Hardie

James Keir Hardie (15 August 185626 September 1915) was a Scottish trade unionist and politician. He was a founder of the Labour Party (UK), Labour Party, and was its first Leader of the Labour Party (UK), parliamentary leader from 1906 to 1908. ...

in 1906. She became treasurer of the Women's Social and Political Union

The Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) was a women-only political movement and leading militant organisation campaigning for women's suffrage in the United Kingdom founded in 1903. Known from 1906 as the suffragettes, its membership and p ...

(WSPU), which Pankurst had founded in 1903, and raised £134,000 over six years. Her husband and Keir Hardie also donated funds to pay off the organisations debts and she insisted that her friend and chartered accountant Alfred Sayers be appointed to audit the WSPU finances.

Christabel Pankhurst lived with the Pethick-Lawrences for five years in London and in Surrey. Pethick-Lawrence attended a number of protests and events with the Pankhursts. In October 1906, she was arrested with Emmeline Pankhurst for "causing a disturbance" outside the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

. As they both refused to pay the £10 fine they were sent to HM Holloway Prison. She also participated in the aborted visit to the Prime Minister in late June 1908, along with Jessie Stephenson, Florence Haig, Maud Joachim and Mary Phillips, after which there was some violent treatment of women protestors, and a number of arrests.

In 1908, together with Beatrice Sanders and Mrs Knight, Pethick-Lawrence organised WSPU's first Week of Self-Denial, where supporters of the suffragette movement were asked to go without certain necessities for a week, donating the money saved to the WSPU. She chose the suffragette campaigning colours of purple, white and green.

Pethick-Lawrence spoke at the Women's Sunday at Hyde Park on 21 June 1908, alongside Flora Drummond, Gladice Keevil, Edith New, Emmeline Pankhurst, Christabel Pankhurst, Adela Pankhurst, and other activists. In 1909, she spoke in support for women's suffrage at the Royal Albert Hall

The Royal Albert Hall is a concert hall on the northern edge of South Kensington, London, England. It has a seating capacity of 5,272.

Since the hall's opening by Queen Victoria in 1871, the world's leading artists from many performance genres ...

. She often visited Eagle House to recover her health after periods in prison, and on 23 April 1909 she planted a tree at "Annie’s Arboretum." Emily Blathwayt wrote in her diary that "it was a beautiful day for tree planting."

In 1911, Pethick-Lawrence took part in the suffrage boycott of the government's census survey by graffitiing votes for women on her enumeration form. She was arrested again in November 1911.

Pethick-Lawrence founded and edited the publication ''Votes for Women

Women's suffrage is the women's rights, right of women to Suffrage, vote in elections. Several instances occurred in recent centuries where women were selectively given, then stripped of, the right to vote. In Sweden, conditional women's suffra ...

'' with her husband from 1907. It was adopted as the official newspaper of the Women's Social and Political Union

The Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) was a women-only political movement and leading militant organisation campaigning for women's suffrage in the United Kingdom founded in 1903. Known from 1906 as the suffragettes, its membership and p ...

(WSPU), already the leading militant suffragette

A suffragette was a member of an activist women's organisation in the early 20th century who, under the banner "Votes for Women", fought for the right to vote in public elections in the United Kingdom. The term refers in particular to members ...

organisation in the country. The couple was arrested and imprisoned in 1912 for conspiracy following demonstrations that involved breaking windows, even though they had disagreed with that form of action. She was force fed during this period of imprisonment.In April 1913, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence was made bankrupt after he refused to pay the £900 costs of the prosecutions of Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, himself and Emmeline Pankhurst in the Old Bailey

The Central Criminal Court of England and Wales, commonly referred to as the Old Bailey after the street on which it stands, is a criminal court building in central London, one of several that house the Crown Court of England and Wales. The s ...

for conspiracy to commit property damage. ''The Irish Times

''The Irish Times'' is an Irish daily broadsheet newspaper and online digital publication. It was launched on 29 March 1859. The editor is Ruadhán Mac Cormaic. It is published every day except Sundays. ''The Irish Times'' is Ireland's leading n ...

'' noted that "this step does not mean that Mr Pethick-Lawrence is insolvent, because he is a wealthy man.'' ''The government sent bailiffs to the Pethick-Lawrence's homes and when their belongings were auctioned most of their possessions were bought back by friends and supporters. Whilst the Pethick-Lawrences were imprisoned, Evelyn Sharp briefly assumed the editorship of the ''Votes for Women'' newspaper.'

After being released from prison, the Pethick-Lawrences recuperated with Emmeline’s brother in Canada. They were then ousted from the WSPU by Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughter Christabel Pankhurst

Dame Christabel Harriette Pankhurst (; 22 September 1880 – 13 February 1958) was a British suffragette born in Manchester, England. A co-founder of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), she directed Suffragette bombing and arson ca ...

, because of their ongoing disagreement over the more radical forms of activism that the Pethick-Lawrences opposed. Her sister Dorothy Pethick also left the WSPU in protest at their treatment, having previously taken part and been imprisoned for militant action.The Pethick-Lawrences then joined Agnes Harben and others starting the United Suffragists, which took over the publication of ''Votes for Women'' and was open to women and men, militants and non-militants alike. ''The Suffragette'' replaced ''Votes for Women'' as the paper of the WSPU.

Pacifism and election campaigns

The Pethick-Lawrences and the Pankhurts also had opposing views on war. Pethick-Lawrence described peace as "the highest effort of the human brain applied to the organisation of the life and being of the peoples of the world on the basis of cooperation." In 1914, she embarked on a speaking tour in America, speaking on the outbreak of

The Pethick-Lawrences and the Pankhurts also had opposing views on war. Pethick-Lawrence described peace as "the highest effort of the human brain applied to the organisation of the life and being of the peoples of the world on the basis of cooperation." In 1914, she embarked on a speaking tour in America, speaking on the outbreak of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, the impact of war on women and feminist pacifism

Pacifism is the opposition to war or violence. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaigner Émile Arnaud and adopted by other peace activists at the tenth Universal Peace Congress in Glasgow in 1901. A related term is ...

.

In April 1915, Aletta Jacobs, a suffragist in the Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

, invited suffrage members from around the world to an International Congress of Women in The Hague

The Hague ( ) is the capital city of the South Holland province of the Netherlands. With a population of over half a million, it is the third-largest city in the Netherlands. Situated on the west coast facing the North Sea, The Hague is the c ...

. Pethick-Lawrence was one of the three female British attendees. At the conference, the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF) was formed and Pethick-Lawrence became a member. As a pacifist, Pethwick-Lawrence was amongst the women who encouraged Jane Addams

Laura Jane Addams (September 6, 1860May 21, 1935) was an American Settlement movement, settlement activist, Social reform, reformer, social worker, sociologist, public administrator, philosopher, and author. She was a leader in the history of s ...

to take leadership over the peace movement in America, along with Carrie Champan Catt and Rosika Schwimmer.

When back in England, she led a campaign against the naval blockade on Germany. She supported the Six Point Group and Open Door Council. Her husband Frederick worked on a farm in Sussex

Sussex (Help:IPA/English, /ˈsʌsɪks/; from the Old English ''Sūþseaxe''; lit. 'South Saxons'; 'Sussex') is an area within South East England that was historically a kingdom of Sussex, kingdom and, later, a Historic counties of England, ...

as a conscientious objector

A conscientious objector is an "individual who has claimed the right to refuse to perform military service" on the grounds of freedom of conscience or religion. The term has also been extended to objecting to working for the military–indu ...

and was a founding member of the Union of Democratic Control

The Union of Democratic Control was a British advocacy group, pressure group formed in 1914 to press for a more responsive foreign policy. While not a pacifism, pacifist organisation, it was opposed to military influence in government.

World Wa ...

(UDC). At the end of the war, she deplored the terms of the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was a peace treaty signed on 28 June 1919. As the most important treaty of World War I, it ended the state of war between Germany and most of the Allies of World War I, Allied Powers. It was signed in the Palace ...

.When the American activist Alice Paul

Alice Stokes Paul (January 11, 1885 – July 9, 1977) was an American Quaker, suffragette, suffragist, feminist, and women's rights activist, and one of the foremost leaders and strategists of the campaign for the Nineteenth Amendment to the Unit ...

visited England in 1921, she met with Pethick-Lawrence and Lady Margaret Rhondda to form an Internal Advisory Committee for the National Women's Party, before travelling on to France.

In 1919, when women were first permitted to stand in elections, Pethick-Lawrence stood as a Labour candidate for Rusholme

Rusholme () is an area of Manchester, in Greater Manchester, England, two miles south of the Manchester city centre, city centre. The population of the ward at the United Kingdom Census 2011, 2011 census was 13,643. Rusholme is bounded by Chorl ...

in Manchester. She called for "better houses, better food, pure milk, a public service of health, provision of midwives and also pensions for widowed mothers." She was not elected, winning a sixth of the vote. Her husband was later elected Member of Parliament (MP) for Leicester West in 1923.

When the Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Act was passed into law in 1928, Pethick-Lawrence and her husband were invited to join a celebratory breakfast held at Hotel Cecil in London. The ''Manchester Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in Manchester in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'' and changed its name in 1959, followed by a move to London. Along with its sister paper, ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardi ...

'' reported that she gave a speech in tribute to four prominent women's suffrage activists who died before the vote was finally won on equal terms: Emmeline Pankhurst, Emily Davidson, Constance Lytton

Lady Constance Georgina Bulwer-Lytton (12 February 1869 – 22 May 1923), usually known as Constance Lytton, was an influential British suffragette activist, writer, speaker and campaigner for prison reform, votes for women, and birth control. S ...

and Anne Cobden-Sanderson.

Later years

In 1938, Pethick-Lawrence published her memoirs, ''My Part in a Changing World'', which discuss the radicalization of the suffrage movement just before theFirst World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

and how the women's and peace movements were closely allied in England.

She was involved in the setting up of the Suffragette Fellowship with Edith How-Martyn to document the women's suffrage movement. Pethick-Lawrence was also involved with the Women's League of Unity, alongside Flora Drummond, which attempted to establish a women's newspaper in 1938-1939. She became the president of the Women's Freedom League (WFL) from 1926 to 1935, and was elected its president in honour in 1953. She was also involved in the campaign led by Marie Stopes

Marie Charlotte Carmichael Stopes (15 October 1880 – 2 October 1958) was a British author, palaeobotanist and campaigner for Eugenic feminism, eugenics and women's rights. She made significant contributions to plant palaeontology and co ...

to provide birth-control to working class women.

As well as campaigning, she travelled extensively with her husband, including to India when he was appointed as Clement Attlee

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee (3 January 18838 October 1967) was a British statesman who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951 and Leader of the Labour Party (UK), Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955. At ...

's Secretary of State for India. Frederick became a long time friend of Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (2October 186930January 1948) was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist, and political ethics, political ethicist who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful Indian ...

. In 1945, she became Lady Pethick-Lawrence when her husband was made a baron.

In 1950, she had a serious accident which ended her campaigning. She was cared for by her husband. Pethick-Lawrence died at home her in Fourways, Gomshall, Surrey, in 1954 following a heart attack.

Suffrage interviews

In 1976 the historian, Brian Harrison, conducted various interviews related to the Pethwick-Lawrence's as part of the Suffrage Interviews project, titled ''Oral evidence on the suffragette and suffragist movements: the Brian Harrison interviews''. Elizabeth Kempster was employed as their housekeeper in 1945 following an interview at Lincoln's Inn, and worked at their home, Fourways, in Surrey, whereSylvia Pankhurst

Estelle Sylvia Pankhurst (; 5 May 1882 – 27 September 1960) was an English Feminism, feminist and Socialism, socialist activist and writer. Following encounters with women-led labour activism in the United States, she worked to organise worki ...

was a frequent visitor. She talks about Pethick-Lawrence's character, appearance, interests and frailty. Gladys Groom-Smith, interviewed in June and August 1976, was secretary to the Pethick-Lawrence's, working alongside Esther Knowles who trained her. She talks about Pethick-Lawrence's role as a speaker in the No More War Movement, and the Pethick-Lawrence's work and marriage, lifestyle and friendships, including with Henry Harben and Victor Duval. Harrison also interviewed the niece of Esther Knowles, who recalled her Aunt's relationship with the Pethick-Lawrence's and her work for them.

Posthumous recognition

Pethick-Lawrence's name and picture (and those of 58 other women's suffrage supporters) are on theplinth

A pedestal or plinth is a support at the bottom of a statue, vase, column, or certain altars. Smaller pedestals, especially if round in shape, may be called socles. In civil engineering, it is also called ''basement''. The minimum height o ...

of the statue of Millicent Fawcett in Parliament Square, London, unveiled in 2018.

In 2018, the London School of Economics

The London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE), established in 1895, is a public research university in London, England, and a member institution of the University of London. The school specialises in the social sciences. Founded ...

renamed three of its key campus buildings after central figures in the British suffrage movement, including Pethick-Lawrence. The newly named buildings were unveiled in a ceremony by HRH Sophie Windsor, then Countess of Wessex.

A blue plaque

A blue plaque is a permanent sign installed in a public place in the United Kingdom, and certain other countries and territories, to commemorate a link between that location and a famous person, event, or former building on the site, serving a ...

was unveiled in Pethick-Lawrence's honour by Weston-super-Mare Town Council and Weston Civic Society in March 2020. It was placed on a wall Lewisham House, Weston-super-Mare

Weston-super-Mare ( ) is a seaside town and civil parish in the North Somerset unitary district, in the county of Somerset, England. It lies by the Bristol Channel south-west of Bristol between Worlebury Hill and Bleadon Hill. Its population ...

(known as 'Trewartha' when she lived there for fourteen years as a child).

Foundations, organisations and settlements

* Espérance Club * Guild of the Poor Brave Things *Independent Labour Party

The Independent Labour Party (ILP) was a British political party of the left, established in 1893 at a conference in Bradford, after local and national dissatisfaction with the Liberal Party (UK), Liberals' apparent reluctance to endorse work ...

* Kibbo Kift

* West London Methodist Mission

* Women's International League

* Women's Social and Political Union

The Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) was a women-only political movement and leading militant organisation campaigning for women's suffrage in the United Kingdom founded in 1903. Known from 1906 as the suffragettes, its membership and p ...

(WSPU)

* Women's International League for Peace and Freedom

* No More War Movement

See also

*Hugh Price Hughes

Hugh Price Hughes (8 February 1847 – 17 November 1902) was a Welsh Methodist clergyman and religious reformer. He served in multiple leadership roles in the Wesleyan Methodist Church. He organised the West London Methodist Mission, a key Me ...

*List of suffragists and suffragettes

This list of suffragists and suffragettes includes noted individuals active in the worldwide women's suffrage movement who have campaigned or strongly advocated for women's suffrage, the organisations which they formed or joined, and the publi ...

*List of women's rights activists

Notable women's rights activists are as follows, arranged alphabetically by modern country names and by the names of the persons listed:

Afghanistan

* Amina Azimi – disabled women's rights advocate

* Hasina Jalal – women's empowerment activis ...

* Mark Guy Pearse, whom Lady Pethick-Lawrence described as "the greatest influence upon the first half of my life".

* Women's suffrage organisations

References

External links

Kibbo Kift official history

West London Mission

{{DEFAULTSORT:Pethick-Lawrence, Emmeline 1867 births 1954 deaths Journalists from Bristol English pacifists English suffragists British baronesses British socialist feminists Politicians from Bristol Women of the Victorian era Labour Party (UK) parliamentary candidates Emmeline Women's Social and Political Union Women's International League for Peace and Freedom people Eagle House suffragettes