Elephant Bird on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Elephant birds are extinct

Like the

Like the

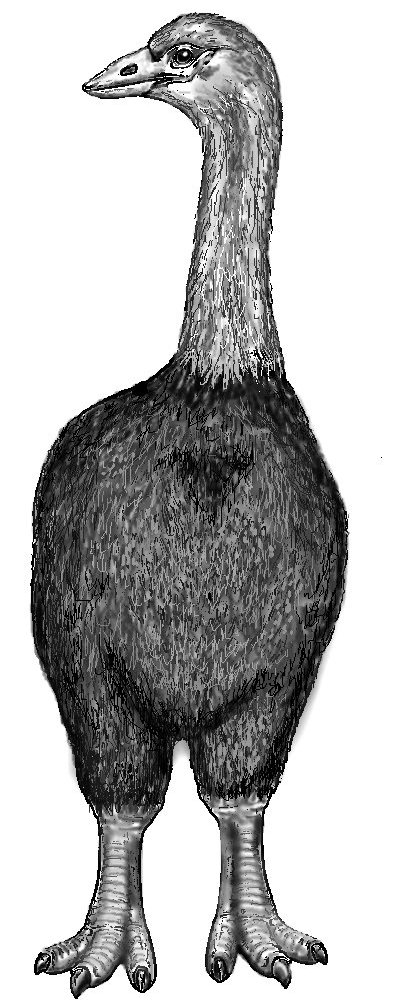

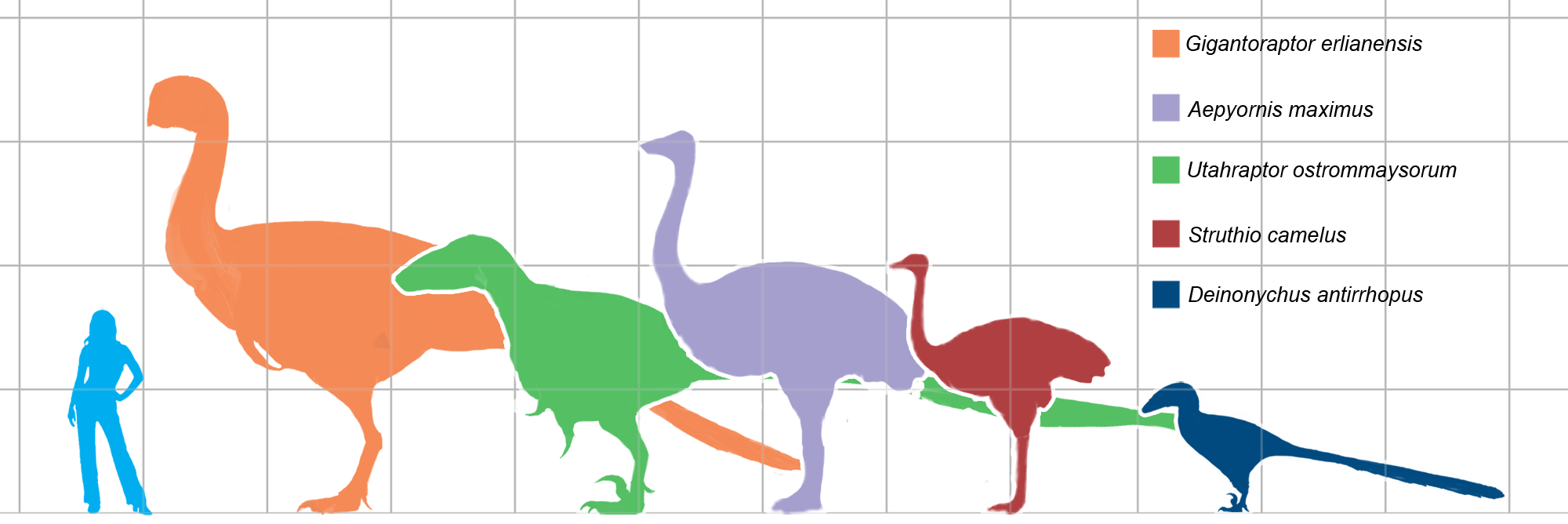

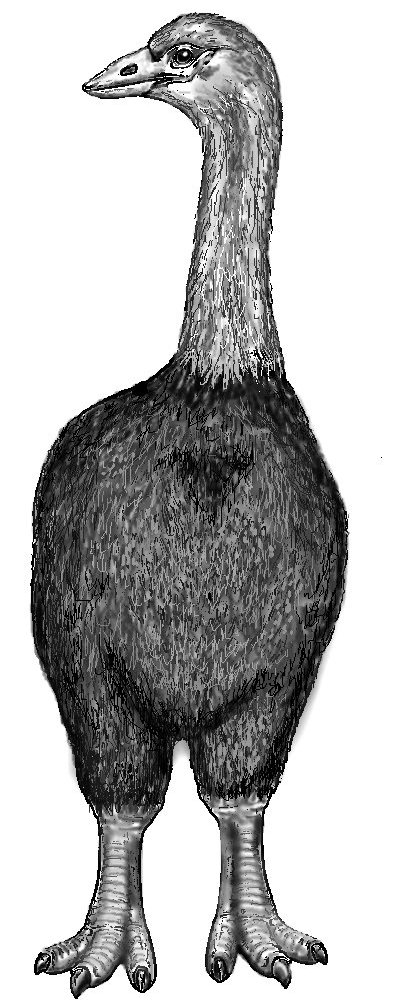

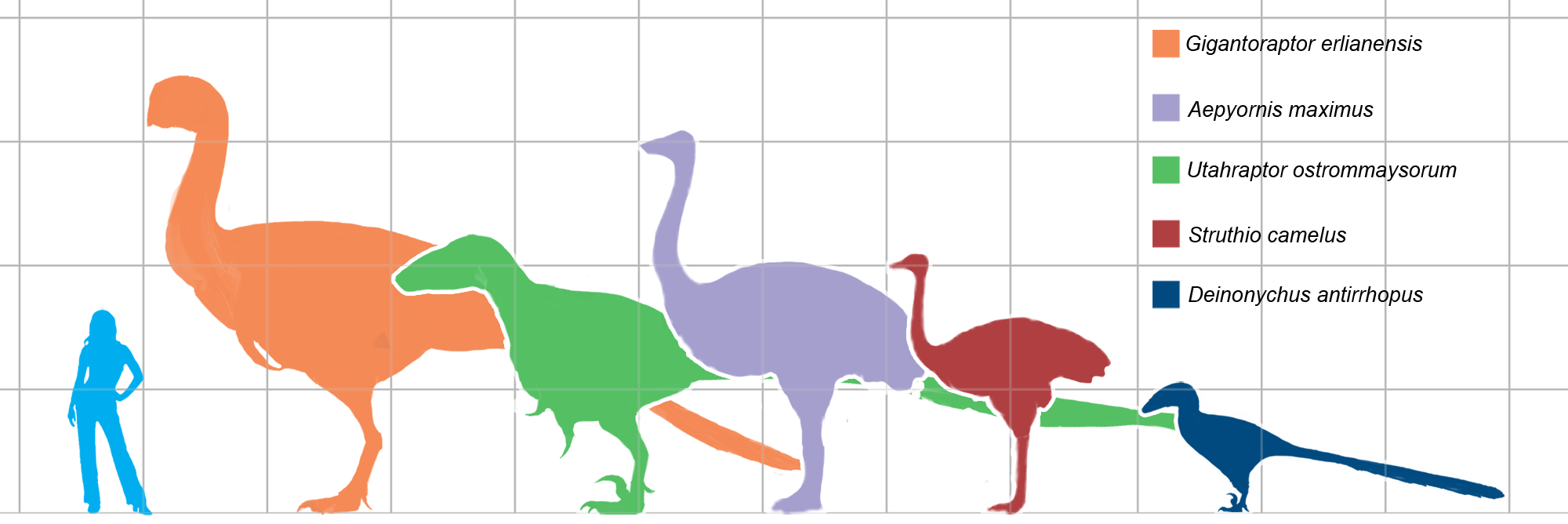

Elephant birds were large sized birds (the largest reaching tall in normal standing posture) that had vestigial wings, long legs and necks, with small heads relative to body size, which bore straight, thick conical beaks that were not hooked. The tops of elephant bird skulls display punctuated marks, which may have been attachment sites for fleshy structures or head feathers. ''Mullerornis'' is the smallest of the elephant birds, with a body mass of around , with its skeleton much less robustly built than ''Aepyornis''. ''A. hildebrandti'' is thought to have had a body mass of around . Estimates of the body mass of ''Aepyornis maximus'' span from around to making it one of the largest birds ever, alongside '' Dromornis stirtoni'' and '' Pachystruthio dmanisensis''. Females of ''A. maximus'' are suggested to have been larger than the males, as is observed in other ratites.

Elephant birds were large sized birds (the largest reaching tall in normal standing posture) that had vestigial wings, long legs and necks, with small heads relative to body size, which bore straight, thick conical beaks that were not hooked. The tops of elephant bird skulls display punctuated marks, which may have been attachment sites for fleshy structures or head feathers. ''Mullerornis'' is the smallest of the elephant birds, with a body mass of around , with its skeleton much less robustly built than ''Aepyornis''. ''A. hildebrandti'' is thought to have had a body mass of around . Estimates of the body mass of ''Aepyornis maximus'' span from around to making it one of the largest birds ever, alongside '' Dromornis stirtoni'' and '' Pachystruthio dmanisensis''. Females of ''A. maximus'' are suggested to have been larger than the males, as is observed in other ratites.

Examination of brain endocasts has shown that both ''A. maximus'' and ''A. hildebrandti'' had greatly reduced optic lobes, similar to those of their closest living relatives, the kiwis, and consistent with a similar

Examination of brain endocasts has shown that both ''A. maximus'' and ''A. hildebrandti'' had greatly reduced optic lobes, similar to those of their closest living relatives, the kiwis, and consistent with a similar

Digimorph.org

excavations of elephant bird eggshells

* ttps://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-21960778# Giant egg from extinct elephant bird up for auction {{Authority control Elephant birds Novaeratitae Prehistoric animals of Madagascar Pleistocene first appearances Species made extinct by human activities Holocene extinctions Taxa named by Charles Lucien Bonaparte

flightless birds

Flightless birds are birds that cannot Bird flight, fly, as they have, through evolution, lost the ability to. There are over 60 extant species, including the well-known ratites (ostriches, emus, cassowary, cassowaries, Rhea (bird), rheas, an ...

belonging to the order

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* A socio-political or established or existing order, e.g. World order, Ancien Regime, Pax Britannica

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

...

Aepyornithiformes that were native to the island of Madagascar

Madagascar, officially the Republic of Madagascar, is an island country that includes the island of Madagascar and numerous smaller peripheral islands. Lying off the southeastern coast of Africa, it is the world's List of islands by area, f ...

. They are thought to have gone extinct around 1000 CE, likely as a result of human activity. Elephant birds comprised three species, one in the genus '' Mullerornis'', and two in '' Aepyornis.'' ''Aepyornis maximus'' is possibly the largest bird to have ever lived, with their eggs being the largest known for any amniote

Amniotes are tetrapod vertebrate animals belonging to the clade Amniota, a large group that comprises the vast majority of living terrestrial animal, terrestrial and semiaquatic vertebrates. Amniotes evolution, evolved from amphibious Stem tet ...

. Elephant birds are palaeognaths (whose flightless representatives are often known as ratite

Ratites () are a polyphyletic group consisting of all birds within the infraclass Palaeognathae that lack keels and cannot fly. They are mostly large, long-necked, and long-legged, the exception being the kiwi, which is also the only nocturnal ...

s), and their closest living relatives are kiwi (found only in New Zealand), suggesting that ratites did not diversify by vicariance

Allopatric speciation () – also referred to as geographic speciation, vicariant speciation, or its earlier name the dumbbell model – is a mode of speciation that occurs when biological populations become geographically isolated from ...

during the breakup of Gondwana

Gondwana ( ; ) was a large landmass, sometimes referred to as a supercontinent. The remnants of Gondwana make up around two-thirds of today's continental area, including South America, Africa, Antarctica, Australia (continent), Australia, Zea ...

but instead convergently evolved flightlessness from ancestors that dispersed more recently by flying.

Discovery

Elephant birds have been extinct since at least the 17th century. Étienne de Flacourt, a French governor of Madagascar during the 1640s and 1650s, mentioned an ostrich-like bird, said to inhabit unpopulated regions, although it is unclear whether he was repeating folk tales from generations earlier. In 1659, Flacourt wrote of the "vouropatra – a large bird which haunts the Ampatres and lays eggs like the ostriches; so that the people of these places may not take it, it seeks the most lonely places." There has been speculation, especially popular in the latter half of the 19th century, that the legendary roc from the accounts ofMarco Polo

Marco Polo (; ; ; 8 January 1324) was a Republic of Venice, Venetian merchant, explorer and writer who travelled through Asia along the Silk Road between 1271 and 1295. His travels are recorded in ''The Travels of Marco Polo'' (also known a ...

was ultimately based on elephant birds, but this is disputed.

Between 1830 and 1840, European travelers in Madagascar saw giant eggs and eggshells. British observers were more willing to believe the accounts of giant birds and eggs because they knew of the moa in New Zealand. In 1851 the genus ''Aepyornis'' and species ''A. maximus'' were scientifically described in a paper presented to the Paris Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (, ) is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French scientific research. It was at the forefront of scientific d ...

by Isidore Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire

Isidore Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire (; 16 December 1805 – 10 November 1861) was a French zoologist and an authority on deviation from normal structure. In 1854 he coined the term ''Ă©thologie'' (ethology).

Biography

He was born in Paris, the ...

, based on bones and eggs recently obtained from the island, which resulted in wide coverage in the popular presses of the time, particularly due to their very large eggs.

Two whole eggs have been found in dune deposits in southern Western Australia

Western Australia (WA) is the westernmost state of Australia. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to the south, the Northern Territory to the north-east, and South Australia to the south-east. Western Aust ...

, one in the 1930s (the Scott River egg) and one in 1992 (the Cervantes

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra ( ; ; 29 September 1547 (assumed) – 22 April 1616 NS) was a Spanish writer widely regarded as the greatest writer in the Spanish language and one of the world's pre-eminent novelists. He is best known for his no ...

egg); both have been identified as ''Aepyornis maximus'' rather than '' Genyornis newtoni,'' an extinct giant bird known from the Pleistocene of Australia. It is hypothesized that the eggs floated from Madagascar to Australia on the Antarctic Circumpolar Current. Evidence supporting this is the finding of two fresh penguin

Penguins are a group of aquatic flightless birds from the family Spheniscidae () of the order Sphenisciformes (). They live almost exclusively in the Southern Hemisphere. Only one species, the Galápagos penguin, is equatorial, with a sm ...

eggs that washed ashore on Western Australia but may have originated in the Kerguelen Islands

The Kerguelen Islands ( or ; in French commonly ' but officially ', ), also known as the Desolation Islands (' in French), are a group of islands in the subantarctic, sub-Antarctic region. They are among the Extremes on Earth#Remoteness, most i ...

, and an ostrich egg

The egg of the ostrich (genus ''Struthio'') is the largest of any living bird (being exceeded in size by those of the extinct elephant bird genus '' Aepyornis''). The shell has a long history of use by humans as a container and for decorative ...

found floating in the Timor Sea

The Timor Sea (, , or ) is a relatively shallow sea in the Indian Ocean bounded to the north by the island of Timor with Timor-Leste to the north, Indonesia to the northwest, Arafura Sea to the east, and to the south by Australia. The Sunda Tr ...

in the early 1990s.

Taxonomy and biogeography

Like the

Like the ostrich

Ostriches are large flightless birds. Two living species are recognised, the common ostrich, native to large parts of sub-Saharan Africa, and the Somali ostrich, native to the Horn of Africa.

They are the heaviest and largest living birds, w ...

, rhea, cassowary

Cassowaries (; Biak: ''man suar'' ; ; Papuan: ''kasu weri'' ) are flightless birds of the genus ''Casuarius'', in the order Casuariiformes. They are classified as ratites, flightless birds without a keel on their sternum bones. Cassowaries a ...

, emu

The emu (; ''Dromaius novaehollandiae'') is a species of flightless bird endemism, endemic to Australia, where it is the Tallest extant birds, tallest native bird. It is the only extant taxon, extant member of the genus ''Dromaius'' and the ...

, kiwi and extinct moa, elephant birds were ratites; they could not fly, and their breast bones had no keel

The keel is the bottom-most longitudinal structural element of a watercraft, important for stability. On some sailboats, it may have a fluid dynamics, hydrodynamic and counterbalancing purpose as well. The keel laying, laying of the keel is often ...

. Because Madagascar and Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surfac ...

separated before the ratite lineage arose, elephant birds are thought to have dispersed and become flightless and gigantic ''in situ

is a Latin phrase meaning 'in place' or 'on site', derived from ' ('in') and ' ( ablative of ''situs'', ). The term typically refers to the examination or occurrence of a process within its original context, without relocation. The term is use ...

''.

More recently, it has been deduced from DNA sequence comparisons that the closest living relatives of elephant birds are New Zealand kiwi, though the split between the two groups is deep, with the two lineages being estimated to have diverged from each other around 54 million years ago.

Placement of Elephant birds within Palaeognathae, after:

The ancestors of elephant birds are thought to have arrived in Madagascar well after Gondwana

Gondwana ( ; ) was a large landmass, sometimes referred to as a supercontinent. The remnants of Gondwana make up around two-thirds of today's continental area, including South America, Africa, Antarctica, Australia (continent), Australia, Zea ...

broke apart. The existence of possible flying palaeognathae

Palaeognathae (; ) is an infraclass of birds, called paleognaths or palaeognaths, within the class Aves of the clade Archosauria. It is one of the two extant taxon, extant infraclasses of birds, the other being Neognathae, both of which form Neo ...

in the Miocene such as '' Proapteryx'' further supports the view that ratites did not diversify in response to vicariance

Allopatric speciation () – also referred to as geographic speciation, vicariant speciation, or its earlier name the dumbbell model – is a mode of speciation that occurs when biological populations become geographically isolated from ...

. Gondwana broke apart in the Cretaceous and their phylogenetic tree does not match the process of continental drift

Continental drift is a highly supported scientific theory, originating in the early 20th century, that Earth's continents move or drift relative to each other over geologic time. The theory of continental drift has since been validated and inc ...

. Madagascar has a notoriously poor Cenozoic terrestrial fossil record, with essentially no fossils between the end of the Cretaceous ( Maevarano Formation) and the Late Pleistocene. Complete mitochondrial genomes obtained from elephant birds eggshells suggest that ''Aepyornis'' and ''Mullerornis'' are significantly genetically divergent from each other, with molecular clock

The molecular clock is a figurative term for a technique that uses the mutation rate of biomolecules to deduce the time in prehistory when two or more life forms diverged. The biomolecular data used for such calculations are usually nucleot ...

analyses estimating the split at around 27-30 million years ago, during the Oligocene

The Oligocene ( ) is a geologic epoch (geology), epoch of the Paleogene Geologic time scale, Period that extends from about 33.9 million to 23 million years before the present ( to ). As with other older geologic periods, the rock beds that defin ...

epoch.

Species

Up to 10 or 11 species in the genus ''Aepyornis'' have been described, but the validity of many have been disputed, with numerous authors treating them all in just one species, ''A. maximus''. Up to three species have been described in ''Mullerornis''.Davies, S. J. J. F. (2003) Recent work has restricted the number of elephant bird species to three, with two in ''Aepyornis'', one in ''Mullerornis''. * Order Aepyornithiformes Newton 1884 epyornithes Newton 1884** Genus '' Aepyornis'' Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire 1850 (Synonym: ''Vorombe'' Hansford & Turvey 2018) *** ''Aepyornis hildebrandti'' Burckhardt, 1893 (Possibly divided into two subspecies) *** ''Aepyornis maximus'' Hilaire, 1851 ** Genus '' Mullerornis'' Milne-Edwards & Grandidier 1894 *** ''Mullerornis modestus'' (Milne-Edwards & Grandidier 1869) Hansford & Turvey 2018 All elephant birds are usually placed in the single family Aepyornithidae, but some authors suggest ''Aepyornis'' and ''Mullerornis'' should be placed in separate families within the Aepyornithiformes, with the latter placed into Mullerornithidae.Description

Elephant birds were large sized birds (the largest reaching tall in normal standing posture) that had vestigial wings, long legs and necks, with small heads relative to body size, which bore straight, thick conical beaks that were not hooked. The tops of elephant bird skulls display punctuated marks, which may have been attachment sites for fleshy structures or head feathers. ''Mullerornis'' is the smallest of the elephant birds, with a body mass of around , with its skeleton much less robustly built than ''Aepyornis''. ''A. hildebrandti'' is thought to have had a body mass of around . Estimates of the body mass of ''Aepyornis maximus'' span from around to making it one of the largest birds ever, alongside '' Dromornis stirtoni'' and '' Pachystruthio dmanisensis''. Females of ''A. maximus'' are suggested to have been larger than the males, as is observed in other ratites.

Elephant birds were large sized birds (the largest reaching tall in normal standing posture) that had vestigial wings, long legs and necks, with small heads relative to body size, which bore straight, thick conical beaks that were not hooked. The tops of elephant bird skulls display punctuated marks, which may have been attachment sites for fleshy structures or head feathers. ''Mullerornis'' is the smallest of the elephant birds, with a body mass of around , with its skeleton much less robustly built than ''Aepyornis''. ''A. hildebrandti'' is thought to have had a body mass of around . Estimates of the body mass of ''Aepyornis maximus'' span from around to making it one of the largest birds ever, alongside '' Dromornis stirtoni'' and '' Pachystruthio dmanisensis''. Females of ''A. maximus'' are suggested to have been larger than the males, as is observed in other ratites.

Biology

nocturnal

Nocturnality is a ethology, behavior in some non-human animals characterized by being active during the night and sleeping during the day. The common adjective is "nocturnal", versus diurnality, diurnal meaning the opposite.

Nocturnal creatur ...

lifestyle. The optic lobes of ''Mullerornis'' were also reduced, but to a lesser degree, suggestive of a nocturnal or crepuscular

In zoology, a crepuscular animal is one that is active primarily during the twilight period, being matutinal (active during dawn), vespertine (biology), vespertine/vespertinal (active during dusk), or both. This is distinguished from diurnalit ...

lifestyle. ''A. maximus'' had relatively larger olfactory bulb

The olfactory bulb (Latin: ''bulbus olfactorius'') is a neural structure of the vertebrate forebrain involved in olfaction, the sense of smell. It sends olfactory information to be further processed in the amygdala, the orbitofrontal cortex (OF ...

s than ''A. hildebrandti'', suggesting that the former occupied forested habitats where the sense of smell is more useful while the latter occupied open habitats.

Diet

A 2022 isotope analysis study suggested that some specimens of ''Aepyornis'' ''hildebrandti'' were mixed feeders that had a large (~48%)grazing

In agriculture, grazing is a method of animal husbandry whereby domestic livestock are allowed outdoors to free range (roam around) and consume wild vegetations in order to feed conversion ratio, convert the otherwise indigestible (by human diges ...

component to their diets, similar to that of the living '' Rhea americana'', while the other species (''A. maximus'', ''Mullerornis modestus'') were probably browsers

Browse, browser, or browsing may refer to:

Computing

*Browser service, a feature of Microsoft Windows to browse shared network resources

*Code browser, a program for navigating source code

*File browser or file manager, a program used to manage f ...

. It has been suggested that ''Aepyornis'' straightened its legs and brought its torso into an erect position in order to browse higher vegetation. Some rainforest fruits with thick, highly sculptured endocarp

Fruits are the mature ovary or ovaries of one or more flowers. They are found in three main anatomical categories: aggregate fruits, multiple fruits, and simple fruits.

Fruitlike structures may develop directly from the seed itself rather th ...

s, such as that of the currently undispersed and highly threatened forest coconut palm (''Voanioala gerardii''), may have been adapted for passage through ratite guts and consumed by elephant birds, and the fruit of some palm species are indeed dark bluish-purple (e.g., '' Ravenea louvelii'' and '' Satranala decussilvae''), just like many cassowary-dispersed fruits, suggesting that they too may have been eaten by elephant birds.

Growth and reproduction

Elephant birds are suggested to have grown in periodic spurts rather than having continuous growth. An embryonic skeleton of ''Aepyornis'' is known from an intact egg, around 80–90% of the way through incubation before it died. This skeleton shows that even at this early ontogenetic stage that the skeleton was robust, much more so than comparable hatchling ostriches or rheas, which may suggest that hatchlings wereprecocial

Precocial species in birds and mammals are those in which the young are relatively mature and mobile from the moment of birth or hatching. They are normally nidifugous, meaning that they leave the nest shortly after birth or hatching. Altricial ...

.

The eggs of ''Aepyornis'' are the largest known for any amniote

Amniotes are tetrapod vertebrate animals belonging to the clade Amniota, a large group that comprises the vast majority of living terrestrial animal, terrestrial and semiaquatic vertebrates. Amniotes evolution, evolved from amphibious Stem tet ...

, and have a volume of around , a length of approximately and a width of . The largest ''Aepyornis'' eggs are on average thick, with an estimated weight of approximately . Eggs of ''Mullerornis'' were much smaller, estimated to be only thick, with a weight of about . The large size of elephant bird eggs means that they would have required substantial amounts of calcium, which is usually taken from a reservoir in the medullary bone in the femurs of female birds. Possible remnants of this tissue have been described from the femurs of ''A. maximus.''

Extinction

It is widely believed that the extinction of elephant birds was a result of human activity. The birds were initially widespread, occurring from the northern to the southern tip ofMadagascar

Madagascar, officially the Republic of Madagascar, is an island country that includes the island of Madagascar and numerous smaller peripheral islands. Lying off the southeastern coast of Africa, it is the world's List of islands by area, f ...

.Hawkins, A. F. A. & Goodman, S. M. (2003) The late Holocene also witnessed the extinction of other Malagasy animals, including several species of Malagasy hippopotamus

Several species of Malagasy hippopotamus (also known as Malagasy pygmy hippopotamus or Madagascan pygmy hippopotamus) lived on the island of Madagascar but are now believed to be extinct. The animals were very similar to the extant hippopotamus ...

, two species of giant tortoise ('' Aldabrachelys abrupta'' and '' Aldabrachelys grandidieri''), the giant fossa, over a dozen species of giant lemurs

Subfossil lemurs are lemurs from Madagascar that are represented by recent (subfossil) remains dating from nearly 26,000 years ago to approximately 560 years ago (from the late Pleistocene until the Holocene). They include both extant a ...

, the aardvark-like animal ''Plesiorycteropus

''Plesiorycteropus'', also known as the bibymalagasy or Malagasy aardvark, is a recently extinct genus of mammals from Madagascar. Upon its description in 1895, it was classified with the aardvark, but more recent molecular evidence instead sug ...

,'' and the crocodile '' Voay''.'''' Several elephant bird bones with incisions have been dated to approximately 10,000 BCE which some authors suggest are cut marks, which have been proposed as evidence of a long history of coexistence between elephant birds and humans; however, these conclusions conflict with more commonly accepted evidence of a much shorter history of human presence on the island and remain controversial. The oldest securely dated evidence for humans on Madagascar dates to the mid-first millennium AD.

A 2021 study suggested that elephant birds, along with the Malagasy hippopotamus species, became extinct in the interval 800–1050 CE (1150–900 years Before Present

Before Present (BP) or "years before present (YBP)" is a time scale used mainly in archaeology, geology, and other scientific disciplines to specify when events occurred relative to the origin of practical radiocarbon dating in the 1950s. Because ...

), based on the timing of the latest radiocarbon dates. The timing of the youngest radiocarbon dates co-incided with major environmental alteration across Madagascar by humans changing forest into grassland, probably for cattle pastoralism

Pastoralism is a form of animal husbandry where domesticated animals (known as "livestock") are released onto large vegetated outdoor lands (pastures) for grazing, historically by nomadic people who moved around with their herds. The anim ...

, with the environmental change likely being induced by the use of fire. This reduction of forested area may have had cascade effects, like making elephant birds more likely to be encountered by hunters, though there is little evidence of human hunting of elephant birds. Humans may have utilized elephant bird eggs. Introduced diseases ( hyperdisease) have been proposed as a cause of extinction, but the plausibility for this is weakened due to the evidence of centuries of overlap between humans and elephant birds on Madagascar.

See also

*Late Quaternary prehistoric birds

Late Quaternary prehistoric birds are Bird, avian taxa that became extinct during the Late Quaternary – the Late Pleistocene or Early Holocene – and before recorded history, specifically before they could be studied alive by orni ...

* Holocene extinction

The Holocene extinction, also referred to as the Anthropocene extinction or the sixth mass extinction, is an ongoing extinction event caused exclusively by human activities during the Holocene epoch. This extinction event spans numerous families ...

References

Further reading

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

Digimorph.org

excavations of elephant bird eggshells

* ttps://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-21960778# Giant egg from extinct elephant bird up for auction {{Authority control Elephant birds Novaeratitae Prehistoric animals of Madagascar Pleistocene first appearances Species made extinct by human activities Holocene extinctions Taxa named by Charles Lucien Bonaparte